Abstract

Fibrosis is a multicellular process leading to excessive extracellular matrix deposition. Factors that affect lung epithelial cell proliferation and activation may be important regulators of the extent of fibrosis after injury. We and others have shown that activated alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) directly contribute to fibrogenesis by secreting mesenchymal proteins, such as type I collagen. Recent evidence suggests that epithelial cell acquisition of mesenchymal features during carcinogenesis and fibrogenesis is regulated by several mesenchymal transcription factors. Induced expression of direct inhibitors to these mesenchymal transcription factors offers a potentially novel therapeutic strategy. Inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) is an inhibitory helix-loop-helix transcription factor that is highly expressed by lung epithelial cells during development and has been shown to coordinate cell proliferation and differentiation of cancer cells. We found that overexpression of Id2 in primary AECs promotes proliferation by inhibiting a retinoblastoma protein/c-Abl interaction leading to greater c-Abl activity. Id2 also blocks transforming growth factor β1–mediated expression of type I collagen by inhibiting Twist, a prominent mesenchymal basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor. In vivo, Id2 induced AEC proliferation and protected mice from lung fibrosis. By using a high-throughput screen, we found that histone deacetylase inhibitors induce Id2 expression by adult AECs. Collectively, these findings suggest that Id2 expression by AECs can be induced, and overexpression of Id2 affects AEC phenotype, leading to protection from fibrosis.

Tissue fibrosis is characterized by matrix remodeling and changes in the cellular makeup.1–4 Injury leads to epithelial cell apoptosis and a damaged, denuded basement membrane.5,6 There is rapid replacement with a provisional matrix and variable accumulation of monocytes and inflammatory cells. Finally, there is recruitment of activated myofibroblasts and deposition of fibrotic matrix proteins, such as type I collagen.

Although there has been considerable focus on myofibroblast activation, fibrogenesis is clearly a multicellular process.4,7 Injury induces activation of resident structural cells, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes, which functionally contribute in unique and overlapping ways to the developing fibrosis.4,7 Epithelial cells are abundant in the lung, and their response during injury and repair is an important determinant toward either restoration of homeostasis or progressive fibrosis.8 Epithelial cells can produce matrix proteins, including laminins and collagens. Epithelial cell apoptosis and proliferation are both prominent features of fibrotic tissue. Finally, epithelial cells produce several profibrotic and antifibrotic factors that influence the behavior of neighboring cells. Thus, epithelial cell production of basement membrane matrix proteins, proliferation and differentiation of epithelial stem cells, and production of antifibrotic factors may favor restoration of the lung to homeostasis, whereas epithelial cell death or acquisition of mesenchymal features with production of fibrotic matrix proteins and cytokines may initiate and sustain fibrosis. These phenotypic changes are regulated, in part, at a transcriptional level.

Recent evidence suggests that phenotypic changes within epithelial cells during carcinogenesis and fibrogenesis are regulated by several mesenchymal transcription factors. Suppressed expression of these epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors for therapeutic intervention9 is under investigation, but at least one family of epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors has a natural set of direct inhibitory factors. Thus, induced expression of these inhibitory factors offers a potential alternative approach.

Helix-loop-helix (HLH) transcription factors, most notably Twist, E2A (with splice variants E47 and E12), and E2-2, have been implicated in cancer cell acquisition of mesenchymal features, including migration and invasion.10–14 Twist has also been shown to be up-regulated in epithelial cells and fibroblasts in lung tissue from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).15,16 The functional significance of HLH transcription factors to fibrogenesis, however, remains unclear. HLH transcription factors function as heterodimers and homodimers, which directly bind to DNA.17 Class V HLH transcription factors, made up of a family of inhibitor of DNA-binding (Id) proteins, lack a DNA-binding basic domain and inhibit DNA binding by other HLH factors.18

Overexpression of Id1 and Id2, in particular, has been shown to inhibit cancer cell mesenchymal gene expression and invasion.19,20 In addition to its interaction with basic HLH transcription factors, a novel interaction between Id2 and retinoblastoma protein (Rb), a member of the pocket protein family, was identified and demonstrated to be important for epithelial cell proliferation.21,22 Most studies have focused on Rb acting as an inhibitor of Id2-mediated proliferation, but the downstream events of this inhibitory interaction have not been identified. Finally, Id2 has emerged as a prominent marker of lung epithelial cells during lung development, with absent or low-level Id2 expression in the adult lung epithelial cells.23,24

More important, expression of the Ids can be regulated by extracellular factors suggesting that transcriptional programming by basic HLH factors can be regulated. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), a prominent cytokine in cancer and fibrosis biology, is the most well-studied repressor of Id expression.12 Conversely, signaling through bone morphogenetic proteins and Wnt/β-catenin has been shown to stimulate Id expression in several cell types.12 Regulation of Id expression has mostly been studied in cancer cells and during development. Regulation of Id2 expression by primary adult alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) and its downstream effects have not been well studied. Herein, we find that overexpression of Id2 inhibits activated primary AEC production of type I collagen through an interaction with Twist. Id2 promotes AEC proliferation on basement membrane proteins through a novel Rb-cAbl pathway leading to inhibition of fibrosis. Finally, by using Id2 promoter–green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter mice to screen a library of chemical compounds, we found that histone deacetylase inhibitors have the ability to induce Id2 expression in adult AECs.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice were in a C57bl/6 background. Mice with enhanced GFP (eGFP) insertion into the Id2 locus (Id2-eGFP) were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).23 Floxed Twist mice were from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center.25 Surfactant protein-C promoter–reverse tetracycline transactivator and tetO-CMV promoter–Cre recombinase mice were previously described.26 Mice aged 6 to 8 weeks were intratracheally (IT) injected with 50 μL saline or 1.5 U/kg bleomycin.27 Mice were anesthetized and intranasally given adenovirus expressing GFP (AdGFP) or Id2 (AdId2) at 4 × 108 plaque-forming units (PFU) per mouse on day 9 after bleomycin.26 Bronchial alveolar lavage fluid and lung samples were collected for analysis, as previously described.28,29 Mice were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment. All animal experiments were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI).

Antibodies and Other Reagents

Fibronectin (Fn) and antibodies to prosurfactant protein-C and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase are from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Matrigel (Mg), biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD16/32, and CD45 antibodies were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Other antibodies used in this study included collagen I and Twist (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Id2 and connective tissue growth factor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), pS807/811 Rb, pS795 Rb, pS780 Rb, Rb, cAbl, pCrkL, and CrkL (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Recombinant keratinocyte growth factor was from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Small airway growth medium was from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) was from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Imatinib, nalotinib, MS275, and trichostatin A (TSA) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Type II AEC Isolation and Culture

Murine type II AECs were isolated and cultured in small airway growth medium with keratinocyte growth factor at 10 ng/mL on tissue culture plates that were precoated with either Mg or Fn, as previously described.28,29 Briefly, mouse lungs were exposed for perfusion and lavage after sacrifice. Isolated lungs were digested with dispase for 45 minutes and then dissected. Lungs were treated with DNase for 10 minutes, and then serially filtered through 70-, 40-, and 20-μm filters. Resuspended cells were labeled with biotin-conjugated anti-CD16/32 and anti-CD45 at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells were negatively selected with streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads through a magnetic separator. AECs were further negatively selected by incubating for 1 to 2 hours on a plastic plate.

For primary human AECs, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco, and University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards. IPF lung tissues were obtained from explanted lung from patients with a pathological diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia and a consensus clinical diagnosis of IPF on the basis of histology, physical examination, high-resolution computed tomography, pulmonary function testing, and diagnostic lung biopsy. Human type II AECs were isolated, as previously described,27,30 from explanted IPF lungs or human lungs not used by the Northern California Transplant Donor Network; our studies indicate that these lungs are physiologically and pathologically normal.31 Briefly, dispase-digested lung was mined and then sequentially filtered through nylon mesh. Filtered cells were separated using a Percoll density gradient (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Contaminating macrophages were negatively selected with anti-CD14 magnetic beads and adherence to human IgG-coated plates. Type II AECs were further purified by cell sorting for the EpCAM-positive, CD45-negative, T1α-negative fraction of nonadherent cells.

Adenoviral and Lentiviral Infection of Cells

Expression vector to generate AdId2 was generated by PCR and cloning of murine Id2 into pAd5CMVmcsIRESeGFPpA using standard cloning techniques. Adenovirus was generated by the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA) Gene Transfer Vector Core. AECs were treated with AdGFP, AdId2, or adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase at 50 PFU/cell for 2 consecutive days. After additional 24 or 48 hours, cells were lysed for analysis. For Id2 knockdown, the RNA interference vectors were purchased from OpenBiosystems (GE Healthcare, Lafayette, CO), and lentivirus was generated by the University of Michigan Vector Core. Lentivirus (5 PFU/cell) was used on days 2 and 3 after AEC isolation to inhibit expression of Id2 in primary mouse AECs.

Luciferase Assay

E2F activity was determined using the Cignal Reporter System (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Lentivirus encoding firefly luciferase regulated by E2F response element and CMV-renilla luciferase was used to treat AECs, followed by treatment with AdGFP or AdId2. After 2 additional days, firefly luciferase normalized to renilla luciferase was determined using a Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Veritas microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Madison, WI), per manufacturers' protocol.

DNA Synthesis Assay and EdU Staining

Cell proliferation was determined by two different DNA synthesis assays. 3H-thymidine was added to cells 18 to 24 hours before harvest at the time points indicated. Proliferation was read as counts per minute on a LS6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), as previously described.32 For some experiments, chemical inhibitors were added to the cell culture media at physiologically relevant doses previously reported to fully inhibit the targeted pathways.33–43 Abl kinase inhibitors, imatinib at 10 μmol/L and nalotinib at 1 μmol/L, or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control was added to cells 48 hours before harvest. For the Id2 knockdown experiment, mouse primary AECs were isolated and cultured on Mg-coated 6-well plates. Cells were treated with lentivirus to knock down Id2 expression on days 2 and 3, and then the cells were treated with 100 nmol/L histone deacetylase inhibitors TSA, 50 μmol/L MS275, or DMSO control on day 4. 3H-thymidine was added on day 5, and cells were harvested on day 6.

For EdU in vitro staining, EdU was added to cells at the final concentration of 10 μmol/L 2 hours before harvest. Cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde diluted in phosphate-buffered saline for 15 minutes. After washing, cells were permeabilized in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 20 minutes. Cells were stained using Click-iT reaction cocktail (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). For EdU in vivo staining, EdU was administered by i.p. injection to mice at 25 μg/g of body weight 24 hours before sacrifice. Lung tissues were embedded in OCT compound and frozen immediately after isolation in dry ice. An immunofluorescence staining protocol was followed for EdU and other protein detection.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining and Masson's Trichrome Assay

Mice were dissected to harvest lung tissues for staining, as previously described.28,29 Lungs were inflated with formaldehyde to 25 cm H2O pressure. Lungs were embedded in paraffin, divided into sections, and stained by the McClinchey Histology Laboratory (Stockbridge, MI).

Hydroxyproline Assay

Lung hydroxyproline was measured as described previously.28,29 Briefly, mouse lungs were isolated and homogenized at 3 weeks after bleomycin IT injection and AdGFP/AdId2 intranasal administration. Homogenized lungs were baked in 12N HCl overnight at 120°C. The samples were mixed with citrate buffer and chloramine T and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Erlich's solution was then added, and the samples were incubated at 65°C for another 15 minutes. The absorbance at 540 nm was measured and the hydroxyproline concentration was quantified against hydroxyproline standards.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence was performed on mouse lung cryosections (7 μm thick), as described before.28,29 Stained sections were imaged on an Olympus BX-51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images were captured with an Olympus DP-70 camera (Olympus) and analyzed with DP controller software version 3.1.1.267 (Olympus).

Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR, as described before.28,29 Briefly, mouse primary AECs were lysed in 1 mL TRIzol (Life Technologies). Reverse transcription was performed with the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen), and RT-PCR was performed using the POWER SYBR Green PCR MasterMix Kit (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY) on Applied Biosystems 7000 sequence detection system or Life Technologies ViiA7 Real Time PCR System. The fold changes were normalized to the housekeeping controls β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Primer sequences for gene collagen 1a1, collagen 3a1, Fn, connective tissue growth factor, β-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were described previously.28,29 Other primer sequences were as follows: Twist1, 5′-CGCACGCAGTCGCTGAACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GACGCGGACATGGACCAGG-3′ (reverse); proliferating cell nuclear antigen, 5′-GGAGAGCTTGGCAATGGGAAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGTACCTCAGAGCAAACGT-3′ (reverse); Rb, 5′-CGATACCAGTACCAAGGTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCACTGCTGGGTTGTGTCAA-3′ (reverse); murine Id2, 5′-AGCCTGCATCACCAGAGACCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGACATAAGCTCAGAAGGGAA-3′ (reverse); E2A, 5′-TTCTCCTCCCGCTTGATCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGTTCCCTCCCTGACCTCTCA-3′ (reverse); E12, 5′-GTGGCCGTCATCCTCAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTGCTTTGGGGTTCAGG-3′ (reverse); E47, 5′-GCCGAAGAGGACAAGAAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTCTCCTCCAGGGACAGC-3′ (reverse); E2-2, 5′-TTGAACCCACCCCAAGACCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCCCTCGTCATCGGATTTG-3′ (reverse); and human Id2, 5′-GAACTGCAGTTTTAATGGGCAGGAGATGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAAAGCTTCAGTGCAAGGTAAGTGATGG-3′ (reverse).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

AECs were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA). After centrifuging, the supernatants were precleared with protein A–agarose beads, then incubated with 5 μg of antibodies to Id2, cAbl, or an appropriate control IgG at 4°C for 1 hour. The samples were then incubated with 50 μL of protein A–agarose at 4°C overnight. The immunocomplexes were washed three times in 1% Triton X-100. The immunoprecipitates were eluted by boiling the beads, and the supernatants were collected for immunoblotting. Immunoblot analysis of cells or immunoprecipitates was performed as previously described.26,27 Scanned immunoblots are representative of at least three separate experiments.

High-Throughput Screening

High-throughput screening was performed with the Center for Chemical Genomics Core Facility (University of Michigan). Primary AECs from Id2-eGFP mice were isolated and cultured on Mg-coated 384-well plates. After 24 hours, medium was replaced and supplemented with chemical compounds listed in Supplemental Table S1. After an additional 48 hours, cells were resuspended with Cell Recovery Solution (BD Biosciences) and analyzed for GFP expression using a Hypercyt/Accuri: High Throughput Flow Cytometer combination system (BD Biosciences) enabling multiplex flow cytometry. The flow cytometry data were analyzed with FloJo software version 10 (Ashland, OR) for expression of GFP.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means, and error bars indicate SEM. For evaluation of group differences, the two-tailed Student's t-test was used, assuming equal variance. P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

Overexpression of Id2 Inhibits AEC Activation and Induces Proliferation in Vitro

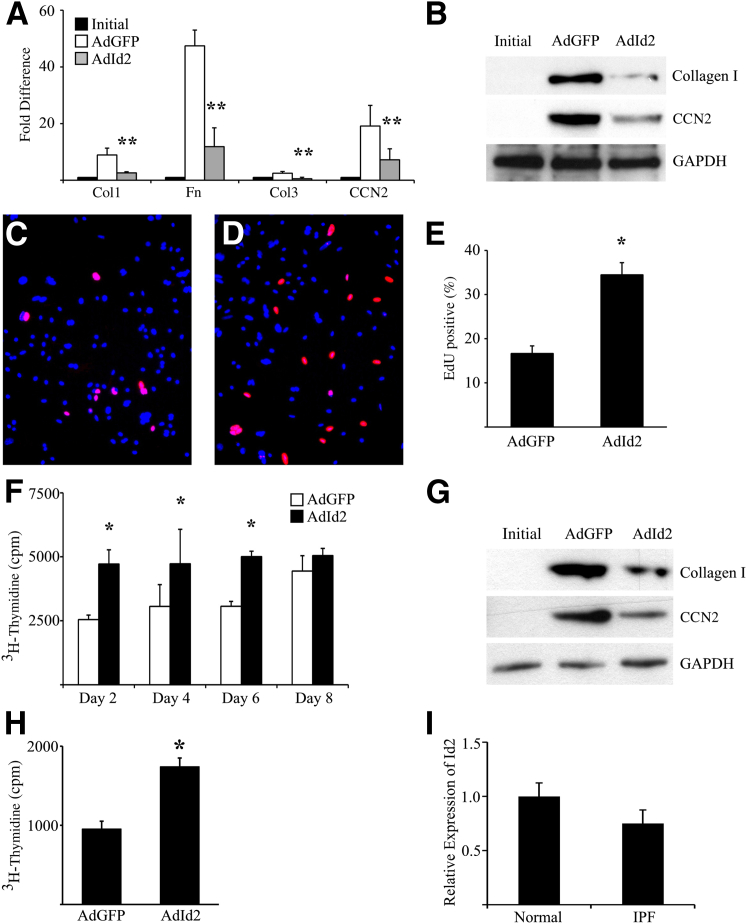

We have previously shown that primary AECs cultured on Mg, which is rich in basement membrane proteins, proliferate and maintain an AEC phenotype, whereas AECs cultured on Fn, a provisional matrix protein, lose epithelial markers and have increased expression of fibrotic matrix and matricellular proteins through integrin-mediated endogenous TGFβ1 activation.26 Cultured AECs from WT mice were infected with adenovirus encoding murine Id2 (AdId2, 50 PFU/cell) or control adenovirus expressing GFP (AdGFP) to induce overexpression of Id2 (Supplemental Figure S1). Overexpression of Id2 significantly attenuated Fn-mediated AEC up-regulation of several mesenchymal markers by real-time quantitative PCR and immunoblot (Figure 1, A and B). On Mg, Id2 overexpression significantly increased proliferation of cultured primary AECs as determined by incorporation of a thymidine analogue, EdU, and by 3H-thymidine incorporation assay (Figure 1, C–F). Similarly, primary human AECs treated with AdId2 also demonstrated reduced expression of fibrotic mesenchymal proteins when cultured on Fn and showed increased proliferation when cultured on Mg (Figure 1, G–I). As expected, AECs from IPF lungs had similar expression of Id2 compared to normal human AECs (n = 15, P = 0.34). We next determined if induced overexpression of Id2 could attenuate fibrosis.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) suppresses alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) activation and stimulates proliferation. A and B: Primary murine AECs immediately after isolation (initial) or cultured on fibronectin (Fn) for 4 days and treated with adenovirus expressing GFP (AdGFP) or Id2 (AdId2). Overexpression of Id2 inhibits expression of profibrotic genes by real-time quantitative PCR (A) and immunoblot (B). C–E: 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation of AECs cultured on Matrigel (Mg) for 4 days and treated with AdGFP (C) or AdId2 (D). E: AECs treated with AdId2 have greater percentage of EdU-positive cells per ×100 field. F: AECs cultured on Mg and treated with AdGFP or AdId2. After 2 to 8 days, cells were analyzed by 3H-thymidine incorporation, demonstrating increased proliferation in AECs overexpressing Id2 on days 2, 4, and 6. G: Overexpression of Id2 inhibits profibrotic protein expression by primary human AECs cultured on Fn for 4 days compared to cells treated with AdGFP. H: Human AECs cultured on Mg and treated AdId2 have increased proliferation after 2 days compared to the cells treated with AdGFP determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation. I: AECs from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) lungs have similar levels of Id2 gene expression compared to normal human AECs (P = 0.34). n = 4 (A, E, F, and H); n = 15 (I). ∗P < 0.05 compared to AdGFP-treated cells (E); ∗P < 0.05 compared to AdGFP-treated cells at the same time point (F); ∗P < 0.05 (H); ∗∗P < 0.01 (A). Col, collagen; CCN2, connective tissue growth factor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

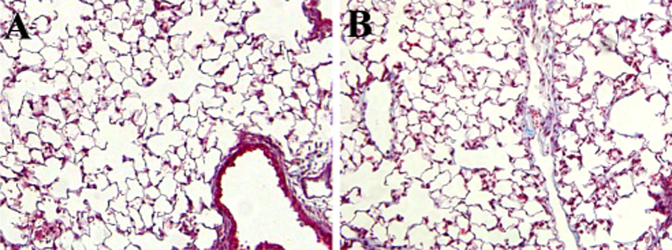

Overexpression of Id2 Attenuates Fibrosis and Induces AEC Proliferation in Vivo

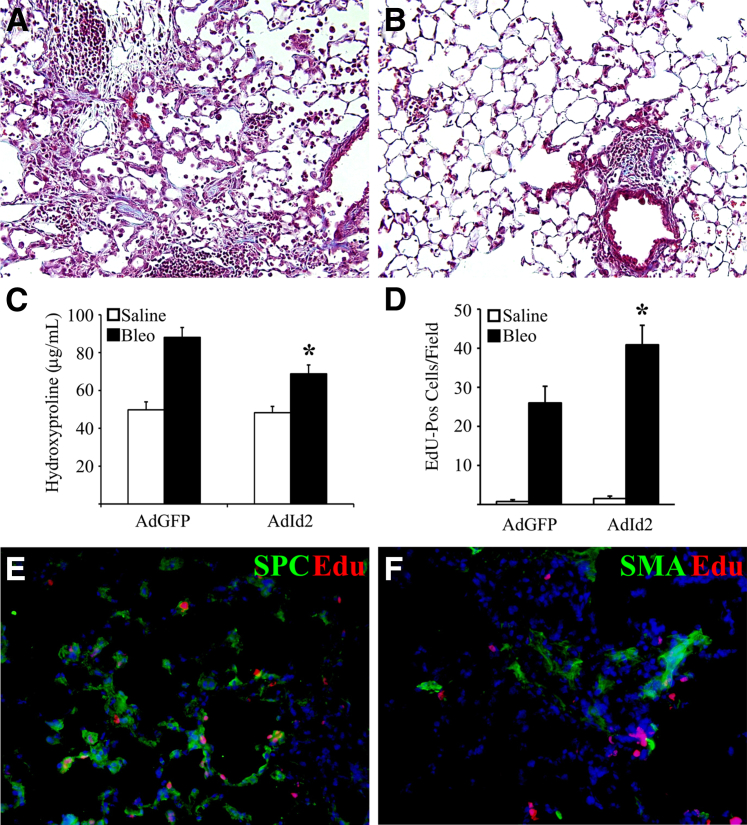

AEC proliferation and fibrotic matrix production have both been implicated as important determinants of the extent of lung fibrosis after injury.8 WT mice were given either IT saline or bleomycin. Ten days after bleomycin treatment, mice were given a single dose of AdGFP or AdId2 (4 × 108 per mouse), leading to robust overexpression of GFP or Id2 primarily within AECs for at least 2 weeks after adenovirus treatment (data not shown). At day 21 after bleomycin, mice were analyzed for fibrosis by trichrome staining and hydroxyproline. Mice treated with AdId2 have significantly less bleomycin-induced fibrosis compared to mice treated with bleomycin and control adenovirus (Figure 2, A–C). Mice treated with saline and AdGFP or AdId2 are histologically normal (Supplemental Figure S2). In separate experiments, proliferation was assessed in vivo by IP injection of EdU on day 12 after bleomycin (2 days after AdId2). On day 13, significantly more EdU-positive cells were seen within Id2-treated mice (Figure 2D). Costaining EdU with prosurfactant protein-C, an AEC marker, and α-smooth muscle actin, a myofibroblast marker, demonstrated that many of the proliferating cells were within AECs rather than within myofibroblasts (Figure 2, E and F). Collectively, these results suggest that Id2 protects mice from bleomycin-induced fibrosis through suppressed AEC activation and promoted AEC proliferation.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) protects mice from bleomycin (Bleo)-induced fibrosis. A and B: Trichrome sections of lungs after Bleo and adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (AdGFP; A) or AdId2 (B). C: Hydroxyproline assay of whole lungs from mice treated with saline or Bleo and AdGFP or AdId2. Mice treated with AdId2 have an attenuated response to Bleo. D: Mice treated with bleomycin and AdId2 have increased numbers of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)–positive cells compared to mice treated with Bleo and AdGFP. E and F: Lung section from mouse treated with Bleo and AdId2 demonstrates EdU (red) staining in many surfactant protein-C (SPC; green; E) positive AECs, but not smooth muscle actin (SMA)–positive myofibroblasts (green, F). n = 5 to 8 (C); n = 4 (D). ∗P < 0.05 compared to AdGFP-treated mice. Original magnifications: ×200 (A and B); ×400 (E and F).

Id2 Attenuates AEC Collagen Production through Twist

Id2 is a class V HLH factor that dimerizes with basic HLH transcription factor, inhibiting their activity.17 Several basic HLH transcription factors have been implicated in mesenchymal gene expression in cancer cells, most notably Twist, E2A (E47/E12), and E2-2. Ten days after IT bleomycin, AECs were isolated and analyzed for expression of these factors. We found most robust induction of Twist (Figure 3A). Furthermore, AECs from uninjured mice cultured on Fn to induce TGFβ1-mediated activation in vitro also demonstrated robust induction of Twist. Inhibition of TGFβ1 signaling with 10 μmol/L TGFβ receptor inhibitor (SB431542) led to significant reduction of Twist expression (Figure 3B). To confirm a direct interaction between Id2 and Twist, primary AECs were isolated, cultured on Fn, and treated with AdGFP or AdId2 as before. After 4 days, cells were lysed and immunopreciptated for Id2, demonstrating Twist coprecipitation in cells overexpressing Id2 (Figure 3C). Finally, primary AECs from floxed Twist mice were isolated and treated with AdGFP (control) or adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase in vitro to eliminate Twist expression. AECs with deleted Twist demonstrated significantly reduced expression of type I collagen similar to cells overexpressing Id2 (Figure 3, D and E). Collectively, these results indicate that Id2 suppression of AEC activation is mediated through a direct inhibitory interaction with Twist. However, mice with lung epithelial cell–specific deletion of Twist were not protected from bleomycin-induced fibrosis (Supplemental Figure S3), suggesting that Id2-mediated inhibition of Twist within AECs alone is not sufficient to block fibrosis but may need to be in coordination with other basic HLH factors or through concomitant induction of AEC proliferation.

Figure 3.

Inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2)–Twist interaction regulates alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) activation. A: Expression of several basic helix-loop-helix (HLH) transcription factors by AECs from mice 10 days after intratracheal (IT) saline or bleomycin immediately after isolation. B: Expression of basic HLH factors by AECs immediately after isolation or after 4 days cultured on fibronectin (Fn) with or without 10 μmol/L SB431642. Fn-cultured AECs undergo transforming growth factor β–dependent activation of Twist expression. C: Coimmunoprecipitation of Id2 and Twist in AECs cultured on Fn and treated with adenovirus expressing Id2 (AdId2) or AdGFP. D and E: AECs from floxed Twist mice treated with adenovirus expressing Cre (AdCre) have reduced activation by real-time quantitative PCR (D) and immunoblot (E). n = 3 (A); n = 4 (B and D). ∗∗P < 0.01 compared to AECs from saline-treated mice (A); ∗P < 0.05 compared to AECs cultured on Fn without SB431542, ∗∗P < 0.01 compared to AEC expression immediately after isolation (B), ∗P < 0.05 compared to AdGFP-treated floxed Twist AECs (D). Col, collagen; CCN2, connective tissue growth factor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Id2 Induces Proliferation through an Rb-cAbl Axis

We then explored the mechanism of Id2-mediated proliferation. Deletion of Twist within floxed Twist AECs did not affect proliferation (data not shown).

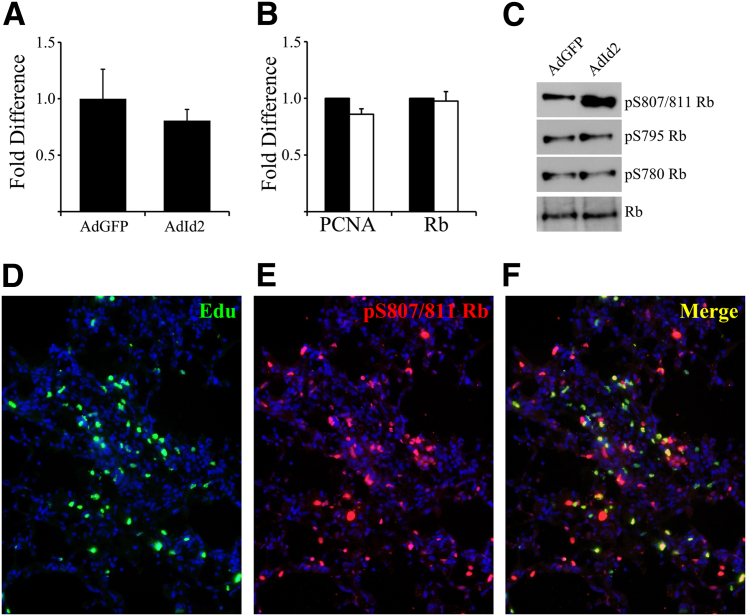

Id2 proliferation has been linked to Rb in cancer cells, but the mechanism remains poorly defined.21,22 Rb acts as a negative regulator of several proliferation pathways, most prominently through regulation of E2F transcription factor. However, overexpression of Id2 did not lead to increased E2F activity (Figure 4, A and B) assessed by E2F-promoter luciferase activation and expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, a well-defined E2F target involved in proliferation.44 Rb interaction and inhibitory effects on protein binding partners can be regulated by distinct phosphorylation sites.45 AECs overexpressing Id2 were analyzed with Rb antibodies recognizing phosphorylation at several distinct sites (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, Id2 led to increased phosphorylation of Rb at serine 807/811 (S807/811), whereas Id2 did not affect the phosphorylation of Rb at the other sites.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) promotes retinoblastoma protein (Rb) serine 807/811 phosphorylation by alveolar epithelial cells (AECs). A: Overexpression of Id2 does not activate E2F response element luciferase expression in AECs cultured on Matrigel. B: Overexpression of Id2 does not affect expression of Rb or proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) by AECs. C: Immunoblot shows that AECs overexpressing Id2 have increased Rb phosphorylation at serine 807/811 (pS807/811). D–F: Lung sections from mice treated with bleomycin and AdId2 immunostained for 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (green, D) and pS807/811 Rb (red, E) demonstrate pS807/811 Rb within proliferating cells (F). Original magnification, ×200 (D–F).

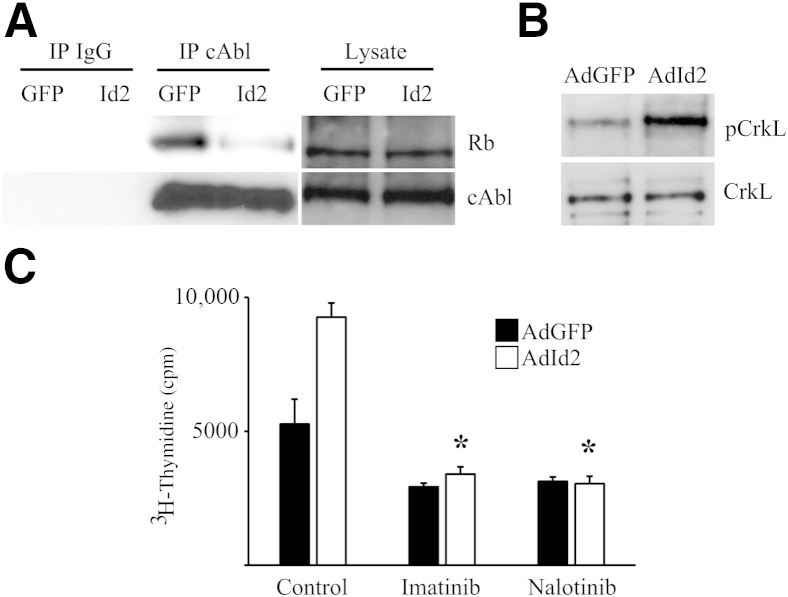

Mice were treated with IT bleomycin, AdId2, and EdU as before. Lung sections were stained for EdU and pS807/811 Rb, demonstrating many co-positive cells (Figure 4, D–F), indicating increased Rb phosphorylation at S807/811 within Id2-mediated proliferating AECs. Phosphorylation at S807/811 has previously been shown to negatively regulate Rb interaction with c-Abl kinase, which would be expected to promote increased c-Abl activity.45 Indeed, overexpression of Id2 led to dramatically decreased association between Rb and c-Abl by coimmunoprecipitation (Figure 5A). Furthermore, overexpression of Id2 led to increased phosphorylation of CrkL, a target of c-Abl, consistent with decreased Rb-mediated inhibition of c-Abl activity (Figure 5B). c-Abl activity is known to stimulate proliferation in several cell types. AECs treated with two different c-Abl inhibitors, 10 μmol/L imatinib and 1 μmol/L nalotinib, had significantly less Id2-mediated proliferation compared to AECs treated with DMSO vehicle control, suggesting that Id2 mediates AEC proliferation through a Rb-cAbl pathway (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2)–induced alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) proliferation is mediated by retinoblastoma protein (Rb)/c-Abl pathway. A: Rb coprecipitation with c-Abl is reduced in AECs overexpressing Id2. B: AECs overexpressing Id2 have increased phosphorylation of c-Abl target CrkL. C: cAbl kinase inhibitors imatinib (10 μmol/L) and nalotinib (1 μmol/L) abrogate Id2-mediated AEC proliferation. n = 4. ∗P < 0.05 compared to control AECs overexpressing Id2 treated with dimethyl sulfoxide. AdGFP, adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Histone Deacetylase Inhibition Induces Expression of Id2

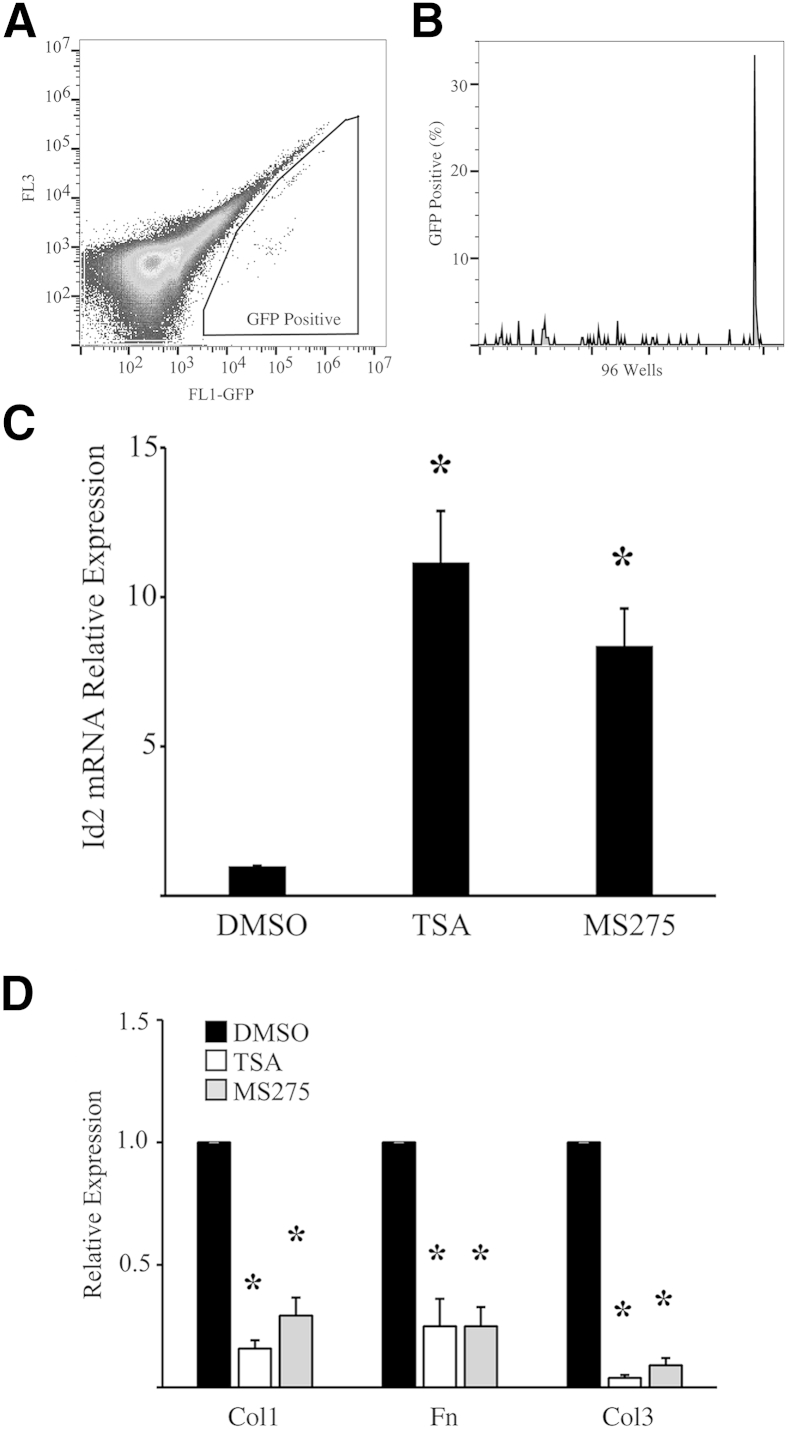

Id2 is highly expressed by epithelial progenitor cells during embryonic lung development, but not by adult AECs.23 Id2 expression was not induced in adult AECs treated with bone morphogenetic protein 4, bone morphogenetic protein 7, and Wnt3, which induces Id2 in other cell types (data not shown). We used AECs isolated from Id2 promoter–GFP (Id2-GFP) mice to identify compounds that might induce expression of Id2 in adult AECs. Id2-GFP AECs were cultured on Mg-coated 384-well plates and treated with a chemical compound library (Supplemental Table S1). After 2 days, cells were trypsinized and analyzed for GFP reporter expression by flow cytometry (Figure 6, A and B). Five compounds were found to induce green fluorescence: 6-aminoindazole, SB216763, RU24969, MS275, and TSA. These compounds were then validated for induction of Id2 expression by real-time quantitative PCR.

Figure 6.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors induce alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) expression. A and B: Green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression by flow cytometry of 96 wells of Id2 promoter–GFP AECs treated with different chemical compounds from a library (A) indicating a well with GFP expression (B). C and D: HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A (TSA; 100 nmol/L) and MS275 (50 μmol/L) induce Id2 expression (C) and suppress AEC fibrotic matrix expression (D). n = 4 (C and D). ∗P < 0.05 compared to AECs treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) alone. Col, collagen; Fn, fibronectin.

Three of the compounds (6-aminoindazole, SB216763, and RU24969) did not induce expression of Id2 but were found to induce green fluorescence within treated AECs (data not shown). Two other compounds, 50 μmol/L MS275 and 100 nmol/L TSA, induced robust expression of Id2 (Figure 6C) compared to AECs treated with DMSO vehicle control. Both of these notably are histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors.

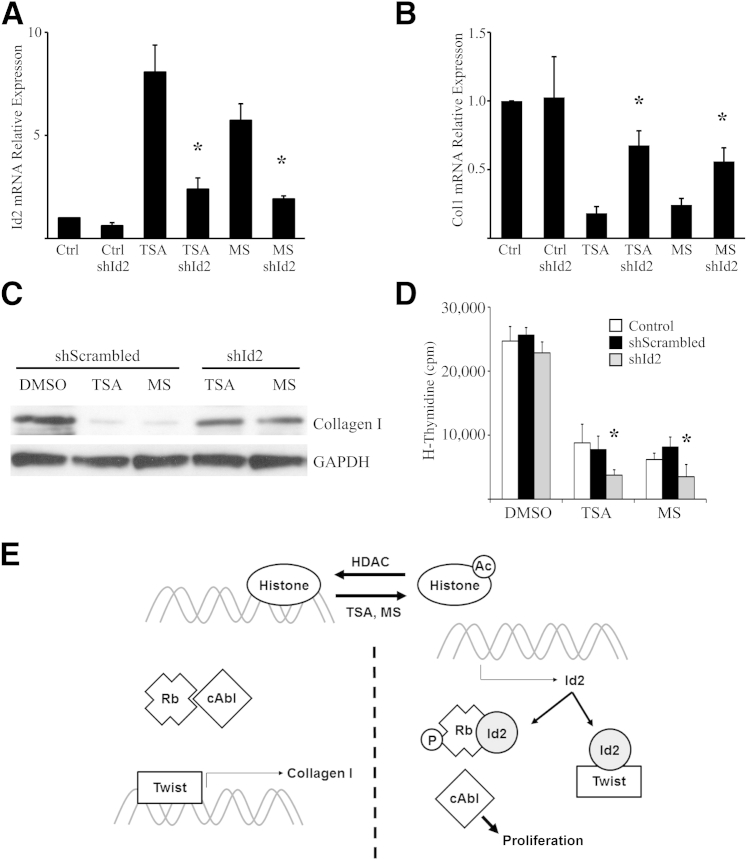

HDAC inhibitors have previously been shown to attenuate fibrosis and inhibit fibroblast activation with suppression of type I collagen and α-smooth muscle actin, but the mechanism remains poorly defined.46,47 TSA and MS275 promoted robust inhibition of collagen expression by primary AECs cultured on Fn (Figure 6D). Finally, primary AECs were treated with lentivirus encoding shRNA to Id2 or scrambled shRNA and HDAC inhibitors TSA and MS275. Inhibition of Id2 expression by shRNA led to partial reversal of the HDAC inhibitor–mediated suppression of collagen I expression (Figure 7, A and B). AECs cultured on Mg were treated with lentivirus encoding shRNA to Id2 and HDAC inhibitors. HDAC inhibition led to decreased proliferation; however, decreased expression of Id2 led to a much more robust inhibition of proliferation, suggesting that HDAC inhibitor–mediated induction of Id2 mitigates broader antiproliferative effects of HDAC inhibitors (Figure 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

Inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) shRNA partially reverses histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor effects on alveolar epithelial cells (AECs). A and B: Real-time quantitative PCR mRNA expression of Id2 (A) and collagen I (B) by AECs treated with 100 nmol/L trichostatin A (TSA), 50 μmol/L MS275 (MS), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control (Ctrl) and lentivirus encoding shRNA to Id2 or scrambled shRNA (10 plaque-forming units/cell). C: Immunoblot for type I collagen by AECs treated with TSA, MS275, or DMSO control and lentivirus encoding shRNA to Id2 or scrambled shRNA. D:3H-thymidine incorporation proliferation assay of AECs treated with TSA, MS275, or DMSO control and lentivirus encoding shRNA to Id2 or scrambled shRNA. E: Schematic of proposed mechanism. Histones inhibit expression of Id2. HDAC inhibitors TSA and MS promote acetylated (Ac) histones that disengage DNA and lead to increased expression of Id2. Id2 binds to Twist, inhibiting collagen I expression, and binds to phosphorylated (P) retinoblastoma protein (Rb), leading to c-Abl–mediated proliferation. n = 4 (B and D). ∗P < 0.05 compared to AECs treated with scrambled shRNA. Col, collagen; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that Id2 regulates two major AEC activities during the fibrogenesis/repair process after injury (Figure 7E). Our interest in Id2 stems from recent evidence indicating a potential role for basic HLH transcription factors in fibrosis. Id2 has mainly been studied in the context of cancer, where it has been shown to induce proliferation and inhibit invasion through suppressed mesenchymal gene expression.12 Although these activities are potentially confounding in the context of cancer, both epithelial cell proliferation and suppression of mesenchymal gene expression may limit progression of fibrosis.23 Id2 expression is high within lung epithelial cells during development but is low within adult AECs. As expected, IPF AECs had similar levels of Id2 expression compared to normal human AECs. However, overexpression of Id2 led to attenuated fibrosis in bleomycin-injured mice through enhanced AEC proliferation and inhibited AEC activation, suggesting that induced reinitiation of Id2-mediated developmental programming could shift the lung back toward normal homeostasis after injury rather than fibrosis.

Given their abundance, AEC activity after injury is likely to be an important determinant of the extent of the resulting fibrosis. The balance of AEC apoptosis and proliferation is one key determinant. Selective loss of lung epithelial cells is sufficient to induce fibrosis, and stimulation of lung epithelial cell proliferation has been shown to limit fibrosis.48,49 Several studies have shown that deletion of genes involved in apoptosis protects mice from fibrosis, but strategies at promoting epithelial cell proliferation have not been as well studied. It may be possible to moderately augment epithelial cell proliferation after injury within the bounds of normal cell cycle checkpoints to avoid malignant transformation, but future studies will have to specifically study this potential limitation.

Id2 has recently been shown to directly interact with Rb and promote cancer cell proliferation.21,44 The immediate downstream events of this interaction are not clear, but focus has generally been on Rb as an inhibitor of proliferative effects of Id2. However, Rb acts as a direct inhibitor of many different proteins involved in cell proliferation. We explored the possibility that Id2 interaction limits Rb inhibitory interaction with other proteins involved in proliferation. We found that overexpression of Id2 promotes Rb phosphorylation at S807/811. We confirmed prior studies that indicated that phosphorylation at S807/811 regulates Rb interaction with c-Abl kinase. Imatinib, a c-Abl kinase inhibitor, was previously found to attenuate fibrosis; however, studies of its mechanism were limited primarily to fibroblast activation/proliferation, and the results of a clinical trial of imatinib in patients with IPF were negative.34

The importance of epithelial-mesenchymal transcription factors during fibrosis has been previously reported. For example, deletion of Snail within hepatocytes led to attenuated liver fibrosis50 and deletion of FoxM1 within AECs protected mice from radiation-induced fibrosis.51 Thus, targeting these transcription factors for potential therapeutic intervention has been of interest in cancer and, more recently, fibrosis. Although Twist is likely the most important target of Id2, overexpression of Id2 attenuated fibrosis, whereas mice with AEC deletion of Twist developed fibrosis after bleomycin, suggesting that Id2 has broader antifibrotic effects beyond inhibition of Twist within AECs. These likely include effects on other basic HLH transcription factors, such as E2A and E2-2, which might compensate for loss of Twist and could also be targets of Id2. These studies highlight the potential difficulties with trying to suppress expression of a single transcription factor. Furthermore, although a genetic approach demonstrates the importance of these pathways in animal models, actually targeting these transcription factors toward therapeutic intervention has been difficult. In this regard, the basic HLH transcription factors are appealing because of the potential to use a natural inhibitory pathway. Thus, induction of Id expression might be a way to limit profibrotic transcriptional activity of basic HLH factors during fibrosis.

After finding that several factors that induce Id2 expression in other cell types did not influence Id2 expression within adult AECs, we identified HDAC inhibitors as potent inducers of Id2 expression using a library of chemical compounds. HDAC inhibitors have previously been shown to attenuate fibrosis in several animal models and to block fibroblast expression of fibrotic matrix proteins.46,47 However, the mechanism by which HDAC inhibition affects fibrosis remains poorly characterized. Histone deacetylation is generally thought to repress gene expression, whereas HDAC inhibition would be expected to promote gene expression. Thus, suppressed type I collagen expression by fibroblasts in response to HDAC inhibitors suggests the induced expression of a transcriptional repressor, such as Id family members. HDAC inhibitors likely influence the expression of many genes, and our studies demonstrate that induced expression of Id2 only partially accounts for the effects of HDAC inhibitors on AEC behavior. Future studies could be directed at inhibition of a more targeted HDAC. Finally, identification and confirmation of HDAC inhibitors as inducers of Id2 expression validates our screen approach, and in future studies we will expand our screen to identify other compounds that might more specifically induce Id2 expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly McDonough and Zhen Geng for technical assistance.

J.Y. and K.K.K. contributed to the conceptual design of the project; J.Y., M.V., M.A., S.D., P.J.W., and K.K.K. designed and interpreted the experiments; and J.Y. and K.K.K. primarily wrote the manuscript, with modification from M.V., S.D., P.J.W., and M.A.

Footnotes

Funded by NIH grants R01 HL108904-01 (K.K.K.) and HL108794 (P.J.W.), the Martin E. Galvin Fund (K.K.K.), and the Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health (P.J.W.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental Data

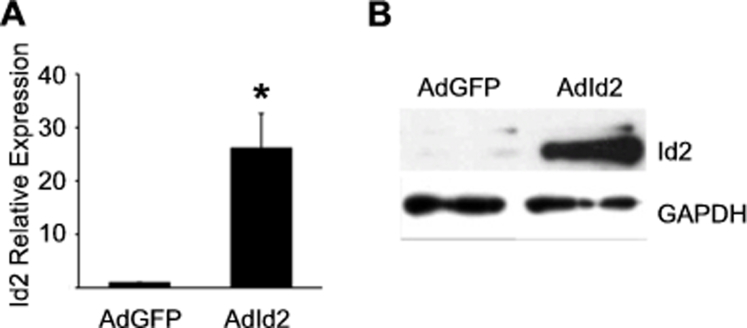

Supplemental Figure S1.

Expression of inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2) by alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) treated with adenovirus encoding Id2. A: Real-time quantitative PCR mRNA expression for Id2 by AECs treated with adenovirus encoding Id2 (AdId2) or GFP (AdGFP) control (n = 3). B: Immunoblot for Id2 by AECs treated with AdId2 or AdGFP. ∗P < 0.05 compared to AECs treated with AdGFP. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Supplemental Figure S2.

Trichrome sections of lungs from mice after saline control and adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (AdGFP; A) or inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (AdId2; B). Original magnification, ×200.

Supplemental Figure S3.

Mice with lung epithelial cell–specific deletion of Twist are not protected from bleomycin-induced fibrosis. A: Lung epithelial cell–specific and permanent deletion of Twist is achieved using transgenic mice carrying the surfactant protein-C promoter–reverse tetracycline transactivator (SPC-rtTA) and tetO-CMV promoter–Cre recombinase (tetO-Cre). In triple transgenic mice (SCtwist), the SPC promoter yields rtTA expression specifically within lung epithelial cells, in the presence of doxycycline (doxy), and rtTA activates the tetO-CMV promoter, leading to expression of Cre recombinase and inversion of the twistflox allele. B: Hydroxyproline assay of whole lungs from littermate control and SCtwist mice treated with saline or bleomycin and adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein or inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (n = 6 to 10).

References

- 1.Selman M., King T.E., Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thannickal V.J., Toews G.B., White E.S., Lynch J.P., 3rd, Martinez F.J. Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:395–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Midwood K.S., Williams L.V., Schwarzbauer J.E. Tissue repair and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis, 1: common and organ-specific mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C216–C225. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00328.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galani V., Tatsaki E., Bai M., Kitsoulis P., Lekka M., Nakos G., Kanavaros P. The role of apoptosis in the pathophysiology of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS): an up-to-date cell-specific review. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scotton C.J., Chambers R.C. Molecular targets in pulmonary fibrosis: the myofibroblast in focus. Chest. 2007;132:1311–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeBleu V.S., Taduri G., O'Connell J., Teng Y., Cooke V.G., Woda C., Sugimoto H., Kalluri R. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selman M., Pardo A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:364–372. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-003TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobrado V.R., Moreno-Bueno G., Cubillo E., Holt L.J., Nieto M.A., Portillo F., Cano A. The class I bHLH factors E2-2A and E2-2B regulate EMT. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1014–1024. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J., Mani S.A., Donaher J.L., Ramaswamy S., Itzykson R.A., Come C., Savagner P., Gitelman I., Richardson A., Weinberg R.A. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slattery C., Ryan M.P., McMorrow T. E2A proteins: regulators of cell phenotype in normal physiology and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1431–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slattery C., McMorrow T., Ryan M.P. Overexpression of E2A proteins induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells suggesting a potential role in renal fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4021–4030. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez-Moreno M.A., Locascio A., Rodrigo I., Dhondt G., Portillo F., Nieto M.A., Cano A. A new role for E12/E47 in the repression of E-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27424–27431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pozharskaya V., Torres-Gonzalez E., Rojas M., Gal A., Amin M., Dollard S., Roman J., Stecenko A.A., Mora A.L. Twist: a regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung fibrosis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bridges R.S., Kass D., Loh K., Glackin C., Borczuk A.C., Greenberg S. Gene expression profiling of pulmonary fibrosis identifies Twist1 as an antiapoptotic molecular “rectifier” of growth factor signaling. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2351–2361. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massari M.E., Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benezra R., Davis R.L., Lockshon D., Turner D.L., Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobin N.P., Sims A.H., Lundgren K.L., Lehn S., Landberg G. Cyclin D1, Id1 and EMT in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:417. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gervasi M., Bianchi-Smiraglia A., Cummings M., Zheng Q., Wang D., Liu S., Bakin A.V. JunB contributes to Id2 repression and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in response to transforming growth factor-beta. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:589–603. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasorella A., Boldrini R., Dominici C., Donfrancesco A., Yokota Y., Inserra A., Iavarone A. Id2 is critical for cellular proliferation and is the oncogenic effector of N-myc in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasorella A., Noseda M., Beyna M., Yokota Y., Iavarone A. Id2 is a retinoblastoma protein target and mediates signalling by Myc oncoproteins. Nature. 2000;407:592–598. doi: 10.1038/35036504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawlins E.L., Clark C.P., Xue Y., Hogan B.L. The Id2+ distal tip lung epithelium contains individual multipotent embryonic progenitor cells. Development. 2009;136:3741–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.037317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y., Hogan B.L. Differential gene expression in the distal tip endoderm of the embryonic mouse lung. Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;2:229–233. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinoi E., Bialek P., Chen Y.T., Rached M.T., Groner Y., Behringer R.R., Ornitz D.M., Karsenty G. Runx2 inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy through its expression in the perichondrium. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2937–2942. doi: 10.1101/gad.1482906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K.K., Kugler M.C., Wolters P.J., Robillard L., Galvez M.G., Brumwell A.N., Sheppard D., Chapman H.A. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13180–13185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605669103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim K.K., Wei Y., Szekeres C., Kugler M.C., Wolters P.J., Hill M.L., Frank J.A., Brumwell A.N., Wheeler S.E., Kreidberg J.A., Chapman H.A. Epithelial cell alpha3beta1 integrin links beta-catenin and Smad signaling to promote myofibroblast formation and pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:213–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI36940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J., Velikoff M., Canalis E., Horowitz J.C., Kim K.K. Activated alveolar epithelial cells initiate fibrosis through autocrine and paracrine secretion of connective tissue growth factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L786–L796. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00243.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J., Wheeler S.E., Velikoff M., Kleaveland K.R., LaFemina M.J., Frank J.A., Chapman H.A., Christensen P.J., Kim K.K. Activated alveolar epithelial cells initiate fibrosis through secretion of mesenchymal proteins. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1559–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmai C., Sutherland R.E., Kim K.K., Dolganov G.M., Fang X., Kim S.S., Jiang S., Golden J.A., Hoopes C.W., Matthay M.A., Chapman H.A., Wolters P.J. Alveolar epithelial cells express mesenchymal proteins in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L71–L78. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00212.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware L.B., Wang Y., Fang X., Warnock M., Sakuma T., Hall T.S., Matthay M. Assessment of lungs rejected for transplantation and implications for donor selection. Lancet. 2002;360:619–620. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09774-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lama V., Moore B.B., Christensen P., Toews G.B., Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and suppression of fibroblast proliferation by alveolar epithelial cells is cyclooxygenase-2-dependent. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:752–758. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Bubnoff N., Gorantla S.P., Thone S., Peschel C., Duyster J. The FIP1L1-PDGFRA T674I mutation can be inhibited by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor AMN107 (nilotinib) Blood. 2006;107:4970–4971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0285. author reply 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daniels C.E., Lasky J.A., Limper A.H., Mieras K., Gabor E., Schroeder D.R., Imatinib-IPF Study Investigators Imatinib treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: randomized placebo-controlled trial results. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:604–610. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0964OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vittal R., Zhang H., Han M.K., Moore B.B., Horowitz J.C., Thannickal V.J. Effects of the protein kinase inhibitor, imatinib mesylate, on epithelial/mesenchymal phenotypes: implications for treatment of fibrotic diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:35–44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leveque D., Maloisel F. Clinical pharmacokinetics of imatinib mesylate. In Vivo. 2005;19:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eadie L.N., Saunders V.A., Hughes T.P., White D.L. Degree of kinase inhibition achieved in vitro by imatinib and nilotinib is decreased by high levels of ABCB1 but not ABCG2. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:569–578. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.715345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight L.A., Di Nicolantonio F., Whitehouse P.A., Mercer S.J., Sharma S., Glaysher S., Hungerford J.L., Hurren J., Lamont A., Cree I.A. The effect of imatinib mesylate (Glivec) on human tumor-derived cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:649–655. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000215062.16308.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller T.A., Witter D.J., Belvedere S. Histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5097–5116. doi: 10.1021/jm0303094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beckers T., Burkhardt C., Wieland H., Gimmnich P., Ciossek T., Maier T., Sanders K. Distinct pharmacological properties of second generation HDAC inhibitors with the benzamide or hydroxamate head group. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1138–1148. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan D., Plattner R. Activation of Abl tyrosine kinases promotes invasion of aggressive breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5648–5655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avila A.M., Burnett B.G., Taye A.A., Gabanella F., Knight M.A., Hartenstein P., Cizman Z., Di Prospero N.A., Pellizzoni L., Fischbeck K.H., Sumner C.J. Trichostatin A increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:659–671. doi: 10.1172/JCI29562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaboin J., Wild J., Hamidi H., Khanna C., Kim C.J., Robey R., Bates S.E., Thiele C.J. MS-27-275, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, has marked in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against pediatric solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6108–6115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norton J.D. ID helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 22):3897–3905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knudsen E.S., Wang J.Y. Differential regulation of retinoblastoma protein function by specific Cdk phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8313–8320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Beneden K., Geers C., Pauwels M., Mannaerts I., Wissing K.M., Van den Branden C., van Grunsven L.A. Comparison of trichostatin A and valproic acid treatment regimens in a mouse model of kidney fibrosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;271:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huber L.C., Distler J.H., Moritz F., Hemmatazad H., Hauser T., Michel B.A., Gay R.E., Matucci-Cerinic M., Gay S., Distler O., Jungel A. Trichostatin A prevents the accumulation of extracellular matrix in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2755–2764. doi: 10.1002/art.22759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deterding R.R., Havill A.M., Yano T., Middleton S.C., Jacoby C.R., Shannon J.M., Simonet W.S., Mason R.J. Prevention of bleomycin-induced lung injury in rats by keratinocyte growth factor. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1997;109:254–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sisson T.H., Mendez M., Choi K., Subbotina N., Courey A., Cunningham A., Dave A., Engelhardt J.F., Liu X., White E.S., Thannickal V.J., Moore B.B., Christensen P.J., Simon R.H. Targeted injury of type II alveolar epithelial cells induces pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:254–263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1615OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowe R.G., Lin Y., Shimizu-Hirota R., Hanada S., Neilson E.G., Greenson J.K., Weiss S.J. Hepatocyte-derived Snail1 propagates liver fibrosis progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2392–2403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01218-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balli D., Ustiyan V., Zhang Y., Wang I.C., Masino A.J., Ren X., Whitsett J.A., Kalinichenko V.V., Kalin T.V. Foxm1 transcription factor is required for lung fibrosis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 2013;32:231–244. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.