Abstract

The pressure dependence of the superconducting transition temperature (Tc) and unit cell metrics of tetragonal (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe were investigated in high pressures up to 41 GPa. The Tc decreases with increasing pressure up to 13 GPa, which can be clearly correlated with the pressure dependence of c (or FeSe layer spacing). The Tc vs. c plot is compared with those of various (NH3)yMxFeSe (M: metal atoms) materials exhibiting different Tc and c, showing that the Tc is universally related to c. This behaviour means that a decrease in two-dimensionality lowers the Tc. No superconductivity was observed down to 4.3 K in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe at 11 and 13 GPa. Surprisingly, superconductivity re-appeared rapidly above 13 GPa, with the Tc reaching 49 K at 21 GPa. The appearance of a new superconducting phase is not accompanied by a structural transition, as evidenced by pressure-dependent XRD. Furthermore, Tc slowly decreased with increasing pressure above 21 GPa, and at 41 GPa superconductivity disappeared entirely at temperatures above 4.9 K. The observation of a double-dome superconducting phase may provide a hint for pursuing the superconducting coupling-mechanism of ammoniated/non-ammoniated metal-doped FeSe.

Various metal-intercalated FeSe superconductors have recently been prepared using the liquid NH3 technique, and high superconducting transition temperatures, Tc′s, have been reported for NH3/metal intercalated FeSe materials, (NH3)yMxFeSe (M: alkali, alkaline-earth and lanthanide atoms)1,2,3,4,5. Furthermore, we found new superconducting phases in (NH3)yMxFeSe0.5Te0.56, and their Tc′s were lower than those of the corresponding (NH3)yMxFeSe analogues. The highest reported Tc in these materials is now 46 K for (NH3)yNa0.5FeSe1. Therefore, the (NH3)yMxFeSe materials are attractive research targets in the hunt for high-Tc superconductors. The Tc increases markedly with the intercalation of ions with smaller ionic radius5. Furthermore, a correlation between Tc and the lattice constant c was observed in (NH3)yMxFeSe materials5, suggesting that an increase in two-dimensionality (2D) is a key for raising the Tc of the materials. This would be similar to HfNCl, in which NH3 or tetrahydrofuran (THF) is inserted into the space between HfNCl layers7. If the dimensionality is the key factor for raising the Tc in metal doped FeSe, it is important to investigate the Tc systematically as a function of c in (NH3)yMxFeSe, i.e., the effect of both physical and chemical pressures on Tc should be comprehensively studied to clarify the correlation between Tc and plane spacing.

Very recently, we investigated the pressure dependence of Tc in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe up to 3.2 GPa and plotted the Tc as a function of pressure p, which showed a negative pressure effect for Tc5. From our previous data5, the Tc vs. p plot was found to show a brief upward deviation from its straight-line approximation. However, the Tc has not previously been plotted as a function of c or FeSe plane spacing because the pressure dependence of lattice constants has not been available. In the present study we examined the crystal structure of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe over the wide pressure range of 0 to 41 GPa using synchrotron X-ray diffraction, and the lattice constants a and c were determined at each p. The Tc was plotted as a function of c. Furthermore, we measured the electrical resistance, R, from 1.9 to 41 GPa, and the Tc value was determined from the R vs. T plot at each p; the DC/AC magnetic susceptibility measurement was not performed above 4 GPa since it is difficult in the higher pressure range than 4 GPa. Namely, the resistance is only a realistic tool for proving superconductivity at high pressures. In this report, the Tc values are plotted as a function of p from 0 to 41 GPa, and the pressure range is extended in comparison with that (0–3.2 GPa) in the previous report5. It has been found from the Tc vs. c plot obtained that the change in Tc is related to the change in the FeSe plane spacing up to 11 GPa, where the superconductivity vanishes. Surprisingly, the Tc quickly recovers above 13 GPa and reaches 49 K at 21 GPa, which is one of the highest reported for bulk superconductors of FeSe-derived materials. The Tc slowly decreases above 21 GPa and at 41 GPa no superconductivity is observed at temperatures above 4.9 K.

Results

Pressure dependence of Tc

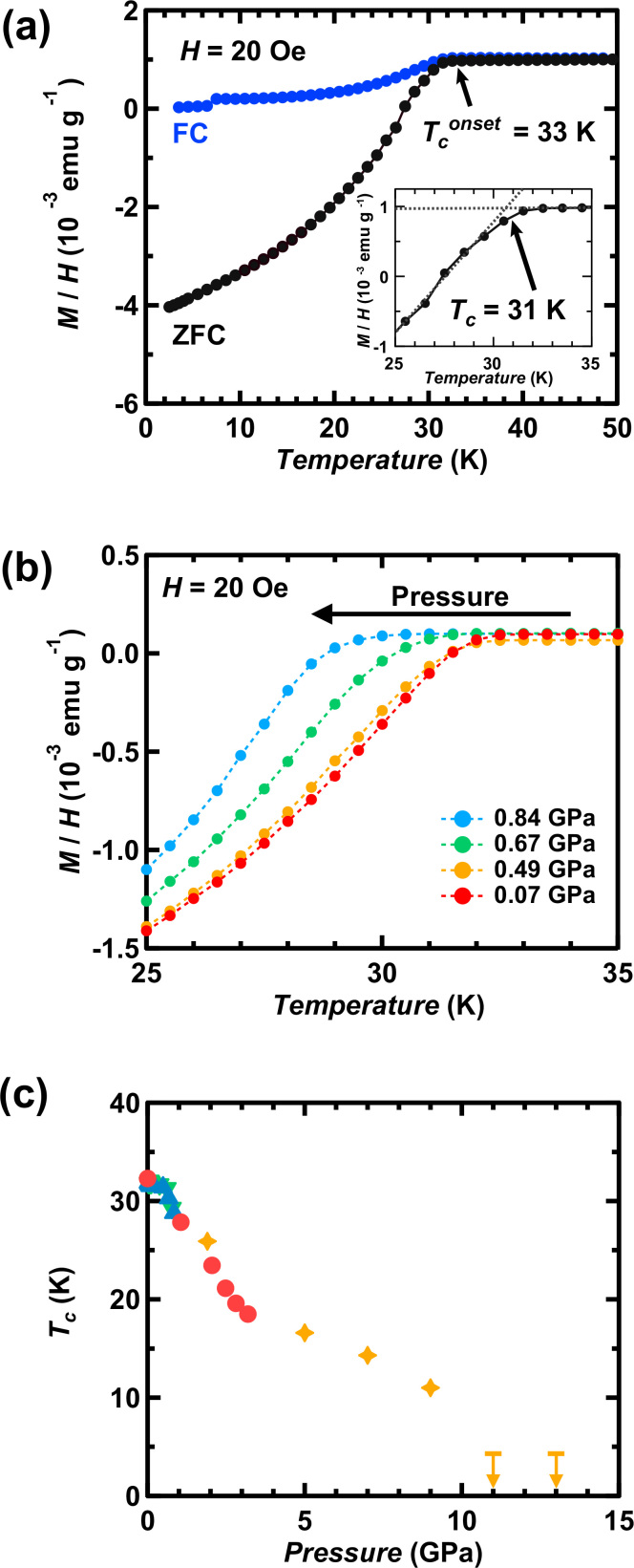

Figure 1(a) shows the M/H vs. T plots of a typical (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample measured under ambient pressure in zero-field cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) modes; M and H refer to magnetization and applied magnetic field, respectively. A clear superconducting transition was observed in both modes, with Tconset and Tc of 33 and 31 K, respectively, in ZFC mode, compared with 33 and 32 K, respectively, in FC mode; the Tc was determined from the intersection of two lines (see inset of Figure 1(a)). No anti-PbO type FeSe phase was observed in the M/H vs. T plot; it shows the superconductivity with Tc = 8 K8. The shielding fraction at 2.5 K is 30%. These values are the same as those in the previous report5. The M/H vs. T plots of the (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample measured at different pressures (0–0.84 GPa) are shown in Figure 1(b). The plots gradually shift to the left in higher pressures, as seen from Figure 1(b).

Figure 1.

(a) M/H vs. T plots for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (ZFC and FC modes) at ambient pressure and (b) M/H vs. T plots in ZFC mode under pressure. The inset in (a) shows how the Tc was determined. (c) Tc vs. p plot for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (p = 0–13 GPa), determined from the temperature dependence of M/H, χ′ and R under pressure. In (c), the Tc′s (blue (M/H in increasing p), green (M/H in lowering p) and red (χ′ in increasing p)) are determined from M/H vs. T and χ′ vs. T plots. The plots are shown in Figure 3(b) of our previous paper5. The Tc′s (orange) determined from R vs. T plots are newly plotted in (c). In (c), the arrows indicate Tc′s lower than the temperatures denoted by bars.

We determined the Tc′s in the pressure range from 1.9 to 13 GPa from the resistance (R) vs. T plots. All Tc′s determined from the temperature dependences of M/H, χ′ and R are plotted as a function of p in Figure 1(c); χ′ is the real part of AC magnetic susceptibility. In the case of M/H and χ′ measurements, the Tc was determined from the intersection point, as shown in the inset of Figure 1(a). The R- T curves below 13 GPa (Figure S1 in Supplementary information) showed the clear drop of R, but the zero-resistance could not be observed because of polycrystalline powder sample. No observation of zero-resistance has been reported so far in ammoniated metal doped FeSe1,5. The drop was assigned to the superconducting transition. For resistance measurement, the T corresponding to the midpoint of the R vs. T plot in normal and superconducting states was defined as Tc in the pressure range from 1.9 to 13 GPa, while above 13 GPa the Tc was determined from the intersection point; the Tc-determination from the midpoint in the pressure range below 13 GPa is the most reasonable way because of existence of background of semiconducting behaviour as seen from Figure S1. As described later, the Tc determined from the midpoint follows the Tc – p plot determined from M/H and χ′ measurements (Figure 1(c)), verifying the reasonable determination of Tc. The Tc decreased monotonically up to 11 GPa, except in the low-pressure range (0–0.8 GPa), as described above. At pressures below 1 GPa, the Tc rose above the straight line. We previously approximated the Tc vs. p plot (0–3.2 GPa) with a linear relationship, but the pressure dependence is not linear in the higher pressure range (see Figure 1(c)). At 11 and 13 GPa, no superconductivity was observed down to 4.3 K.

Pressure dependence of lattice constants

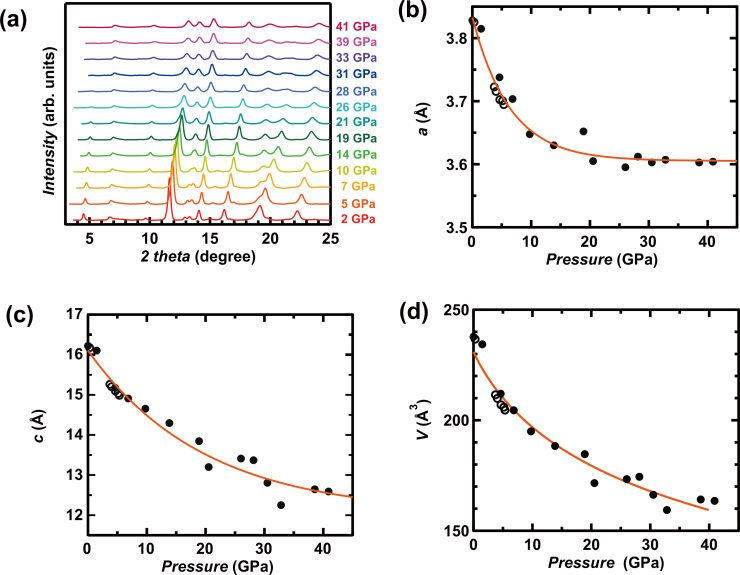

The XRD patterns measured in the pressure range from 0 to 41 GPa are shown in Figure 2(a); the XRD patterns were recorded at the synchrotron X-ray radiation facility of the Institute of High Energy Physics, Beijing, China, and at SPring-8, Japan. All Bragg reflections gradually shifted to higher angles, implying that the lattice shrinks with increasing pressure. The XRD pattern did not change substantially as pressure was applied to the (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample, indicating no structural transition even across this wide pressure range. The crystal structure of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is body-centred tetragonal (space group: I4/mmm) at ambient pressure, and the space group is maintained up to 41 GPa.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe under pressure (p = 2–41 GPa). (b) and (c) Pressure dependence of a and c in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe. In (b) and (c), the solid and open circles refer to the lattice constants determined from XRD data recorded at the Institute for High Energy physics and SPring-8, respectively. The fitting curves are drawn with a single exponential formula. (d) Pressure dependence of V in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is given together with the fitting curve drawn using the semi-empirical third-order Birch-Murnaghan formula.

The pressure dependence of a, c, and unit cell volume V is shown in Figures 2(b)–(d). The a and c values were determined by applying LeBail fitting to the XRD patterns. The values determined from XRD patterns recorded at both facilities were substantially consistent. The a value decreased dramatically up to 10 GPa and decreased slowly from 10 to 41 GPa, showing an exponential decay of a. As seen from Figure 2(c), c also decreased monotonically up to 41 GPa. The difference, Δa, between the maximum a ( = 3.8331(1) Å) at 0 GPa and the minimum a ( = 3.604(2) Å) at 41 GPa was 0.23 Å, and the Δa/a (0 GPa) = 0.06. In contrast, the difference, Δc, between the maximum c ( = 16.217(1) Å) at 0 GPa and the minimum c ( = 12.59(1) Å) at 41 GPa was 3.63 Å, and Δc/c (0 GPa) = 0.22. These results suggest that the FeSe layer spacing ( = c/2) shrinks easily, which is reasonable considering that the interaction between FeSe layers is due to van der Waals force. Moreover, the compressibility of c in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is much higher than that in parent anti-PbO type FeSe9. Here, it may be reasonable that the compressibility is smaller in the metal intercalated FeSe than that in pure FeSe because there is additional ionic bonding with metal atoms. Nevertheless, the compressibility is opposite for the expected one. This may be due to the large space maintained by van der Waals force, which is produced by the insertion of ammoniated metal coordinate or NH3. Namely, the insertion of molecules leads to the large compressibility. In addition, the anisotropy of compressibility is larger presumably because of the large space between FeSe layers.

The V monotonically decreases without any significant change in rate as the pressure increases to 41 GPa, i.e., the V – p plot can be fitted with semi-empirical third-order Birch-Murnaghan equation10 (see Figure 2(d)), showing no structural phase transition; the bulk modulus, K0, derivative of bulk modulus with respect to p, K0′, and the reference volume (V at 0 GPa), V0, of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe are 39.6(1) GPa, 4.7(1) and 232.3(1) Å3, respectively. The K0 is larger than that (K0 = 30.7(1.1) GPa)9 in anti-PbO type FeSe, showing the larger compressibility in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe even in volume.

A correlation between Tc and structural parameters

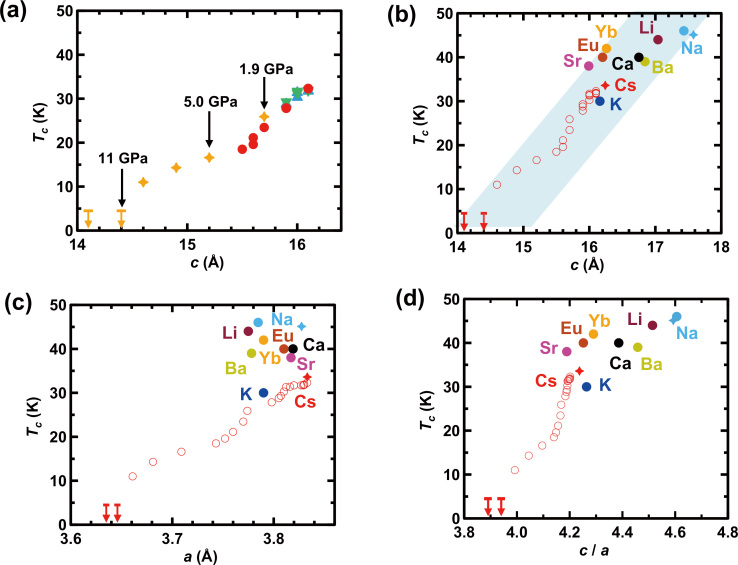

Figure 3(a) shows a Tc vs. c plot constructed based on the plots of Tc vs. p (Figure 1(c)) and c vs. p (Figure 2(c)). The Tc decreases monotonically and reaches 11 K at c = 14.6(5) Å (9 GPa) and <4.3 K at c = 14.4(5) Å (11 GPa); the c values at 9 and 11 GPa are evaluated based on the fitting curve with exponential formula shown in Figure 2(c); the fitting for experimental c – p plot with simple exponential expression was achieved to evaluate the c at any pressure, which was a reasonable way to evaluate the c values at the whole pressure range of 0–41 GPa. Figure 3(a) suggests a clear correlation between Tc and c, i.e. plane spacing, in which the FeSe plane spacing is c/2. On the other hand, the Tc ( = 31 K) of K0.5FeSe with a c of 14.0367(7) Å11 at 0 GPa is higher than the Tc ( = 11 K) of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe with a c of 14.6(5) Å (9 GPa), indicating that the variation of Tc with c (or plane spacing) is not universally consistent for all metal-doped FeSe solids (non-ammoniated and ammoniated solids).

Figure 3.

(a) Tc vs. c plot evaluated from the plots of Tc vs. p (Figure 1(c)) and c vs. p (Figure 2(c)). In (a), symbols' colours correspond to those shown in Figure 1(c). (b) Tc vs. c plots constructed by combining the Tc vs. c plot (physical pressure effect; Figure 3(a)) and the Tc vs. c plot determined from Tc′s and c′s for various (NH3)yMxFeSe (chemical pressure effect). (c) Tc vs. a and (d) Tc vs. c/a plots constructed based on physical and chemical pressure effects on Tc, which were made the same way as (b). In (b)–(d), open circles refer to the behaviour of Tc vs. lattice constants determined from the pressure dependence of Tc in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe, while solid symbols refer to Tc vs. c plots determined with various (NH3)yMxFeSe samples (solid open circles and stars are taken from Refs. 1 and 5, respectively). In (b)–(d), the arrows indicate Tc′s lower than the temperatures denoted by bars.

Figure 3(b) shows a Tc vs. c plot that includes both the Tc vs. c plots obtained from the pressure effect ((NH3)yCs0.4FeSe) and from the chemical pressure effect (or Tc vs. c in various metal-doped FeSe); x is 0.4 or 0.5 in the (NH3)yMxFeSe used to determine the chemical pressure effect. The graph clearly shows that the Tc is related to c (FeSe plane spacing), over all the c values recorded, based on both chemical and physical pressure effects. In the (NH3)yMxFeSe solids, the smallest c realized at 0 GPa is 14.84(1) Å for (NH3)0.37K0.6Fe2Se23 (Tc = 30 K), which is smaller than that (16.16(5) Å)1 for ammoniated KFe2Se2 ( = (NH3)yK0.5FeSe) with Tc = 30 K; this result (Tc = 30 K for 14.84(1) Å) is not plotted in the graph shown in Figure 3(b) because the x ( = 0.6/2 = 0.3) is smaller than 0.5. The result does not follow the Tc – c scenario shown in Figure 3(b). The reason why an outlier (Tc = 30 K for 14.84(1) Å) is obtained in (NH3)yKxFeSe is unclear, but the factor other than c may be necessary to be considered. Except for the result, the Tc – c plots for (NH3)yMxFeSe (x ~ 0.5) seem to be meaningful, as seen from Figure 3(b). In addition, a c of 14.4 Å in (NH3)yMxFeSe has never been achieved without applying pressure. Thus, we determined the Tc for an FeSe plane spacing that cannot be achieved without the application of pressure.

Furthermore, we tried to relate Tc to other factors such as a, c/a, the Se-Fe-Se angle (α), and the anion height (height of Se from the Fe plane). As seen from Figure 3(c), the Tc for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe under pressure is related to the lattice constant a, i.e. the Tc decreases monotonically with decreasing a. However, the Tc values (chemical pressure effect) realized for various (NH3)yMxFeSe at 0 GPa do not follow the Tc vs. a relationship obtained by the application of pressure (physical pressure effect), indicating that the Tc is not simply or always related to a. Moreover, the behaviour of Tc – c/a is also different between physical and chemical pressure effects as seen from Figure 3(d).

Since we did not obtain the Rietveld refinements for XRD patterns, but used LeBail fitting, the atomic coordinates of Fe and Se were not obtained. It should be noted that Fe and Se occupy the positions (0.0, 0.5, 0.25) and (0.0, 0.0, z), respectively, and the α and anion height cannot be exactly determined. At the present stage, we tried to evaluate α and anion height based on the lattice constants at each p and the atomic coordinates determined at ambient pressure5. The correlations between Tc and α or anion height were investigated over the pressure range of 0 to 13 GPa. The Tc decreased monotonically when the α and anion heights approached the ideal values, 109.5° and 1.38 Å (Figures S2 and S3 in Supplementary Information), respectively, showing different Tc behaviour from the FeAs materials, in which the Tc increases when α and anion height are close to the ideal values of 109.5° and 1.38 Å, respectively (inverse V-shaped behaviour)12,13. These results imply that the Tc may not be simply related to α and the anion height, as in FeAs. However, the Rietveld refinement for the XRD pattern at each p is absolutely required to clarify more precisely the relationship between Tc and α or the anion height. The relationship between Tc and anion height is briefly dealt with in the Discussion section, and an interesting scenario is suggested.

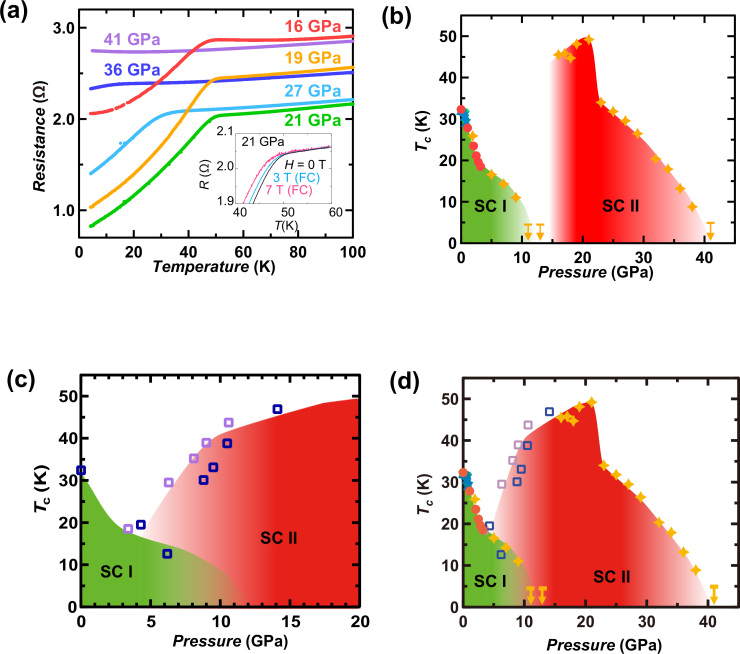

The rapid increase in Tc above 13 GPa

We applied more than 13 GPa pressure to the (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample. Figure 4(a) shows the R vs. T plots from 16 to 41 GPa, which surprisingly show a drop in R above 45 K in the limited pressure range from 16 to 21 GPa. The R vs. T plots at 21 GPa were measured in an H range of 0 to 7 T (Inset of Figure 4(a)), showing that the Tc shifted to the left as H increased. Therefore, the drop in R (Figure 4(a) can be unequivocally assigned to a superconducting transition. The Tc was plotted as a function of p over the wide range of 0 to 41 GPa (Figure 4(b)). As described in the previous section, the Tc in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe decreased monotonically with increasing pressure up to 13 GPa, where superconductivity vanished, but the superconductivity quickly recovered above 13 GPa, and the Tc became as high as 46 K at 16 GPa. The Tc increased slightly at pressures up to 21 GPa, reaching 49 K at 21 GPa. The Tc slowly dropped above 21 GPa, and at 41 GPa no superconductivity was observed down to 4.9 K. This behaviour is similar to that reported previously for Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se214, in which the Tc′s increased dramatically up to 48 K or 48.7 K from 0 K (~10 GPa) under pressures greater than 11 GPa. The first and the second dome-like superconducting phases were named as SC I and SC II, respectively, as seen from Figure 4(b). Figure 4(b) shows the disappearance of SC I and the emergence of SC II at 11–15 GPa.

Figure 4.

(a) R vs. T plots for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe at pressures of 16–41 GPa. Inset of (a): R vs. T plots for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe at 21 GPa at 0, 3 and 7 T. (b) Tc vs. p plot (p = 0–41 GPa) determined from the temperature dependence of M/H, χ′ and R for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (sample 1 (first batch)) under pressure. Colours of plots in the pressure range below 13 GPa correspond to those in Figure 1(c). The star refers to the Tc determined from the R vs. T plot. (c) Tc vs. p plot (p = 0–14 GPa) determined from the temperature dependence of R for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (sample 2 and 3 (second batch)) under pressure. Colours of plots in blue and purple refer to the samples 2 and 3, respectively. (d) Tc vs. p plot (p = 0–41 GPa) constructed by combining the Tc vs. p plots shown in Figures 4(b) and (c). In (b) and (d), the arrows indicate Tc′s lower than the temperatures denoted by bars.

To confirm the presence of SC II, we measured the pressure dependence of Tc for another batch (a second batch) of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe, which was made using the same technique as the sample whose results appear in the graph shown in Figure 4(b). This sample is referred to as ‘the second sample’ for the convenience of readers. The Tc decreased as increasing pressure was applied to the sample. The behaviour of Tc in the second sample (Figure 4(c)) was the same as the data described above (Figure 4(b)) in the pressure range up to 6 GPa, but the Tc rapidly increased up to 30 K at 8.8 GPa (see Figure S4 of Supplementary Information). The R vs. T plot for ‘the third sample’ taken from the second batch of material was also measured, and the Tc vs. p plot is shown in Figure 4(c). Figure 4(d) shows the Tc – p plots determined from all the (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe samples. Here it should be noticed that for the samples 2 and 3 of Figures 4(c) and (d), the Tcmid′s are plotted for the superconducting transition ascribable to the SC I, while the Tc′s are plotted for that ascribable to SC II, so that the plots can be reasonably compared with those of sample 1.

The Tc values for the second and the third samples (second batch) are consistent with each other (Figure 4(c)). As seen from Figures 4(b) and (d), the SC II emerged suddenly above 15 GPa in the first batch. On the other hand, as seen from Figures 4(c) and (d), the SC II slowly appeared above 5 GPa in the second batch. The Tc for the SC II in the second sample reached 47 K at 14 GPa, which is the same as the Tc for the sample 1 providing the graph shown in Figure 4(b). These results strongly support the presence of SC II.

Here, we briefly discuss the difference in physical and chemical properties of the sample batches, 1 and 2, of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe. The Tc of the second batch was 32.5 K at ambient pressure, and the shielding fraction was 23% at 10 K, showing the same magnetic properties as the other (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample prepared in this study. The XRD of the second batch shows the similar pattern to that reported previously for (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe5, and the Rietveld refinement for the XRD pattern provided the lattice constants (a = 3.8232(3) Å and c = 16.247(3) Å) which are close to those (a = 3.8331(1) Å and c = 16.217(1) Å) in Ref. 5. Furthermore, the stoichiometry of Cs was determined by the Rietveld refinement, and the chemical composition for the second batch was evaluated to be (NH3)yCs0.294(2)FeSe, which is almost the same as that, (NH3)yCs0.255(5)FeSe, reported previously5. These results imply that the second batch is a typical (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample used in this study. Thus, the difference in physical and chemical properties between batches 1 and 2 seems to be too small. Nevertheless, unknown physical and chemical difference may be hidden, but it is unclear at the present stage. More detailed work is indispensable for clarifying the difference.

We carefully checked the R vs. T plots of the second sample at 8.8 GPa (9.5 GPa) to clarify whether the material with a superconducting transition lower than 30 K (33 K) was observed. The R- T plots at 8.8 and 9.5 GPa showed a very small drop in R below 10 K together with the rapid drops at 30 and 34 K, respectively (Figure S4 in Supplementary Information), suggesting the multiple superconducting phases of low and high Tc at around the pressure range of 8.8 to 9.5 GPa; this may be due to the presence of microstructure corresponding to two superconducting phases, but the exact origin why the multiple superconducting phases were observed in another batch remains to be solved. The investigation using the second batch unequivocally evidenced the presence of second-dome superconducting phase.

These results show the presence of a high-Tc phase in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (Tc > 45 K) that emerges in the pressure range from 14 to 21 GPa. The Tc of 49 K observed at 21 GPa is one of the highest reported in bulk superconductors of FeSe-derived materials. The low-Tc phase disappears completely at around 11–13 GPa. Therefore, that pressure may be recognized as a ‘quantum critical point’. With reducing pressure, the Tc follows the Tc vs. p plot constructed for increasing pressure (not shown), implying that the pressure dependence of Tc is reversible.

Discussion

In this study, it has been found that the Tc of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is related to the lattice constant c, i.e. the FeSe plane spacing in the pressure range up to 13 GPa. The variation of Tc due to plane spacing is convincingly shown not only by the pressure dependence of Tc in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe, but also from the Tc′s in various ammoniated metal doped FeSe's, (NH3)yMxFeSe. Both chemical and physical pressure effects have made clear the dependence of Tc on FeSe plane spacing. This implies that an increase in 2D nature produces higher Tc′s in (NH3)yMxFeSe, meaning that an increase in Fermi nesting can stabilize the superconducting state. We suggested previously5 that a spin-density wave (SDW) ground state with a weak magnetic moment played an important role in superconductivity, as suggested in NaFe1−xCoxAs15. Recently, the intercalation of metal atoms into FeSe was achieved using a solvent (ethylenediamine) other than liquid NH3, which expands the FeSe plane spacing more than NH316. Nevertheless, the Tc saturates at around 45 K, meaning that Tc will not rise above 45 K even if the 2D nature increases further.

Furthermore, we applied pressures of more than 13 GPa to (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe. The new superconducting phase exhibiting higher Tc emerged dramatically after the first superconducting phase vanished. The re-emerged superconducting phase showed almost a constant Tc (46–49 K) in the pressure range from 14 to 21 GPa. This behaviour of pressure-induced re-appearance of superconductivity is quite similar to that of previously discovered Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se214. Our study reveals the presence of a pressure-induced high-Tc phase in MxFeSe. Sun et al. suggested that the re-emergence of superconductivity in pressurised Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se2 is closely associated with a quantum critical transition16, in which both the antiferromagnetic phase and the low-Tc superconducting phase disappear. On the other hand, we observed the multiple superconducting phases of low-Tc and high-Tc in the second sample (second batch) of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe (see Figures S4 in Supplementary Information) at pressures below 13 GPa. This implies that there are inhomogeneous parts of low-Tc and high-Tc phases even at the same pressure.

The different T – p phase diagram between two batches of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe, that the first batch provides the distinguished SC I and SC II while the second batch provides the superposed SC I and SC II, must be discussed. As described in the results section, the chemical and physical characters of both batches were almost the same. Therefore, the difference may not be assigned to the different physical/chemical nature. Under high pressure, SC II exactly appeared in both batches, implying that SC II is stabilized under high pressure, while SC I disappeared with increasing pressure. In the intermediate pressure, SC I and SC II seem to coexist in the samples 2 and 3. If the inhomogeneity of applied pressure is present, the SC I and SC II may coexist in the DAC cell. If it is the case, the sample 1 may provide the exact T – p phase diagram in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe, because the complete disappearance of SC I causes the emergence of SC II. The origin is not still clear, but the presence of high-Tc phase (SC II) was convinced (Figures 4(b)–(d)).

Here, it should be noted that non-ammoniated Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se2 may belong to another type of alkali selenide superconductor with antiferromagnetic insulating and superconducting phases at ambient pressure; antiferromagnetic insulating phase is not unambiguously found in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe. If the antiferromagnetic state is contained in the sample, the deficiency of Fe may be observed. The deficiency of Fe has not been confirmed in ammoniated metal doped FeSe through our study, which was performed by energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry. Thus, the chemical composition of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is different from the above single crystals (Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se2) concerning Fe deficiency, implying that the average structure of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe is not 245 phase (antiferromagnetic order phase)17. Since Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se2 can be expressed as the 245 phase17 which was assigned to antiferromagnetic order phase, the volume fraction of the superconducting phase which was assigned to 27819 may be lower in the above crystals than that of ammoniated metal doped FeSe. Therefore, considering the different microstructures of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe and Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 (or K0.8Fe1.7Se2), the mechanism of emergence of a high-Tc phase in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe would be different from that in non-ammoniated alkali selenide superconductors18. Namely, in the former, the relationship between the re-emergence of SC II and magnetic properties is still ambiguous, although the latter was closely associated with the magnetic transition (antiferromagnetic to paramagnetic)18.

The pressure dependence of the XRD pattern showed no clear structural phase transition up to 41 GPa, suggesting that the crystal structure of the high-Tc phase is the same as that of the low-Tc phase. Here we must stress that detailed information on atomic coordinates has not yet been obtained under pressure, since we achieved only LeBail fitting for XRD patterns up to 41 GPa. This implies that the possibility of changed atomic coordinates in the high-Tc phase observed above 13 GPa cannot be ruled out.

We present a scenario for the pressure dependence of Tc on the anion height. Recently, Lu et al. reported a V-shaped relationship (V-shaped curve) between Tc and anion height in FeSe-derived superconductors19. Examination of the plot of Tc vs. anion height in FeSe-derived superconductors (Figure 4 of Ref. 18), suggests that the Tc should decrease when the anion height decreases to 1.45 Å from 1.53 Å (the anion height in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe at 0 GPa) and it should increase steeply with a decrease in anion height to less than 1.45 Å18. Furthermore, the Tc should decrease below 1.38 Å (Figure 45 of Ref. 15) since an inverse V-shaped curve is found in FeAs-derived superconductors12,13. We plotted the Tc of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe as a function of anion height over the wide pressure range of 0–41 GPa (Figure S5 in Supplementary Information), which shows V-shaped/inverse V-shaped behaviour although the turning points of anion height (1.33 and 1.26 Å) of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe deviate from the above values (1.45 and 1.38 Å). Thus, a scenario based on V-shaped and inverse V-shaped curves12,13,19 describing the dependence of Tc on the anion height found in FeSe and FeAs based superconductors may provide a physical basis to explain the pressure dependence of Tc observed in this study. To verify this interpretation, more precise analyses of XRD patterns with Rietveld refinement are indispensable.

The possibility that a magnetic transition (variation of magnetic structure) produces the re-emergence of superconductivity (or the appearance of a high-Tc phase) as in Tl0.6Rb0.4Fe1.67Se2 and K0.8Fe1.7Se2 cannot completely be ruled out in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe at the present. To clarify the correlation between superconductivity and magnetism, measurements of neutron diffraction and magnetism under pressure are indispensable.

Finally, it is important to discuss whether the superconducting coupling mechanism in the high-Tc superconducting phase is the same as that in the low-Tc phase. At the present stage, how the second phase is engendered by pressure is still unclear, although a geometrically based scenario is suggested by the empirical results of this study. The fact that the high-Tc phase appears in (NH3)yMxFeSe as well as MxFeSe at high pressure suggests that a pressure-induced high-Tc phase may be an intrinsic and universal feature in metal doped FeSe superconductors.

Methods

Sample preparation and characterizations

The samples of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe were prepared according to the method described in the previous paper5. The XRD pattern of the sample under pressure was measured at 297 K at two synchrotron radiation facilities, the 4W2 beamline at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility and BL02B2 at SPring-8. A diamond anvil cell (DAC) was used for the high-pressure XRD measurement. The pressure was determined by monitoring ruby fluorescence. The superconductivity of the (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe sample was checked by DC magnetic susceptibility (M/H) recorded by SQUID magnetometer (Quantum Design MPMS2). The Tc′s at 0 GPa for all the samples used in this study were 31 to 32 K as shown in Ref. 5. The pressure dependence of Tc in the low pressure range (0–3.2 GPa) was determined from the DC (M/H) and AC (χ′) magnetic susceptibilities measured in our previous study5, but the M/H vs. T plots at low pressures (Figure 1(b)) are presented for the first time in this paper. The difference in Tc determined from M/H and χ′ of (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe was 0.6 K at ambient pressure as described in Ref. 5. The difference is in the symbols in graphs (Figure 1(c), Figures 3(a)–(d) and Figures 4(b) and (d)).

Temperature dependence of R

The temperature dependence of R was measured in four-terminal measurement mode under pressure. The sample was introduced into the DAC in an Ar-filled glove box so as to apply the pressure to the sample without any exposure to air. The sample was loaded directly onto a plate of cubic BN/epoxy resin/rhenium in the DAC, and the four Pt electrodes for resistance measurement were between the sample and the plate. The experimental details for setting the sample in the DAC and for R-measurement are described elsewhere20. The pressure was determined by monitoring ruby fluorescence. A constant electric current, I ( = 100 μA), was supplied by an Advantest R6561 Multimeter, which also measured the voltage. To confirm that a reliable resistance measurement was obtained, the constant current flow in this measurement system and the linear I vs. V plot were checked frequently, implying that the data on resistance are reliable and the thermal voltage can be ignored.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid (22244045, 24654105, 26105004 and 26400361) from MEXT, from the LEMSUPER project (JST-EU Superconductor Project) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), and by the Program for Promoting the Enhancement of Research Universities. The work in China was supported by the NSF of China (Grant No. 91321207) and 973 project (Grant No. 2011CBA00100). The XRD measurements at SPring-8 were supported by 2013B1145. K.P. thanks the EPSRC for support (EP/K027255).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.K. designed this research project and supervised experiments. M.I., L.Z. and Y.S. synthesized and characterized (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe samples. M.S., Y.N. and H.L.T.N. carried out the resistance measurements under pressure. M.I., S.A. and T.C.K. measured DC and AC magnetic susceptibility under pressure. D.G., J.G., J.L., Y.-C.L. and L.S. measured XRD patterns under pressure. Y.S., M.S. and K.P. performed LeBail fitting for XRD data under pressure. Y.K. discussed the experimental results with H.G., M.S., T.K. (Osaka), T.K. (Okayama), K.S., L.S. and K.P. during this study. Y.K. managed (edited) all parts of this paper.

References

- Ying T. P. et al. Observation of superconductivity at 30–46 K in AxFe2Se2 (A = Li, Na, Ba, Sr, Ca, Yb, and Eu). Sci. Rep. 2, 426 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrard-Lucas M. et al. Enhancement of the superconducting transition temperature of FeSe by intercalation of a molecular spacer layer. Nature Mater. 12, 15–19 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying T. P. et al. Superconducting phases in potassium-intercalated iron selenides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2951–2954 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmaier S. J. et al. Ammonia-rich high-temperature superconducting intercalates of iron selenide revealed through time-resolved in situ X-ray and neutron diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 630–633 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. et al. Superconductivity in (NH3)yCs0.4FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 88, 094521 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y. et al. Superconducting phases in (NH3)yMxFeSe1−zTez (M = Li, Na, and Ca). Phys. Rev. B 89, 144509 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ye G. J. et al. Superconductivity in YbxMyHfNCl (M = NH3 and THF). Phys. Rev. B 86, 134501 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F.-C. et al. Superconductivity in the PBO-type structure a-FeSe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14262 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadonna S. et al. Pressure evolution of the low-temperature crystal structure and bonding of the superconductor FeSe (Tc = 37 K). Phys. Rev. B 80, 064506 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Fan D., Xu J., Ma M., Liu J. & Xie H. P-V-T equation of state of molybdenite (MoS2) by a diamond anvil cell and in situ synchrotron angle dispersive X-ray diffraction. Physica B 451, 53–57 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. G. et al. Superconductivity in the iron selenide KxFe2Se2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0). Phys. Rev. B 82, 180520(R) (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-H. et al. Effect of structural parameters on superconductivity in fluorine-free LnFeAsO1−y (Ln = La, Nd). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 083704 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi Y. & Takano Y. Review of Fe chalcogenides as the simplest Fe-based superconductor. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 102001 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. L. et al. Re-emerging superconductivity at 48 kelvin in iron chalcogenides. Nature 483, 67–69 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai P. et al. Visualizing the microscopic coexistence of spin density wave and superconductivity in underdoped NaFe1−xCoxAs. Nature Commun. 4, 1596 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeda T., Noji T., Kawamata T., Kato M. & Koike Y. New Li-ethylenediamine-intercalated superconductor Lix(C2H8N2)yFe2−zSe2 with Tc = 45 K. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 123705 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ding X. et al. Influence of microstructure on superconductivity in KxFe2−ySe2 and evidence for a new parent phase K2Fe7Se8. Nature Commun. 4, 1897 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. Pressure-driven quantum criticality in iron-selenide superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. et al. Superconductivity in LiFeO2Fe2Se2 with anti-PbO-type spacer layers. Phys. Rev. B 89, 020507(R) (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K., Amaya K. & Suzuki N. Pressure-induced superconductivity in elemental materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 74, 1345–1357 (2005). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information