Abstract

Background: Children's screen viewing (SV) is associated with higher levels of childhood obesity. Many children exceed the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline of 2 hours of television (TV) per day. There is limited information about how parenting styles and parental self-efficacy to limit child screen time are associated with children's SV. This study examined whether parenting styles were associated with the SV of young children and whether any effects were mediated by parental self-efficacy to limit screen time.

Methods: Data were from a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2013. Child and parent SV were reported by a parent, who also provided information about their parenting practices and self-efficacy to restrict SV. A four-step regression method examined whether parenting styles were associated with the SV of young children. Mediation by parental self-efficacy to limit screen time was examined using indirect effects.

Results: On a weekday, 90% of children watched TV for <2 hours per day, decreasing to 55% for boys and 58% for girls at weekends. At the weekend, 75% of children used a personal computer at home, compared with 61% during the week. Self-reported parental control, but not nurturance, was associated with children's TV viewing. Parental self-efficacy to limit screen time was independently associated with child weekday TV viewing and mediated associations between parental control and SV.

Conclusions: Parental control was associated with lower levels of SV among 5- to 6-year-old children. This association was partially mediated by parental self-efficacy to limit screen time. The development of strategies to increase parental self-efficacy to limit screen-time may be useful.

Introduction

Higher levels of screen viewing (SV) are associated with higher levels of obesity among children.1,2 Several studies have reported that many children exceed the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline to limit noneducational screen time for children older than 2 years of age to a maximum of 2 hours per day.3,4 Given that SV tracks from childhood into adulthood,5 ensuring that children moderate their screen time is likely to help prevent future obesity.

Identification of the variables associated with a behavior is a critical first step in designing new interventions.6,7 Parents play a pivotal role in children's behavior, and it seems likely that parents influence children's SV. Parenting styles set the emotional context of parent-child interactions.8–10 Maccoby and Martin11 defined four parenting styles. Authoritative parenting (high nurturance, high control) is associated with positive child outcomes, including higher academic performance12,13 and fruit and vegetable intake.14,15 The remaining three styles are: authoritarian (low nurturance, high control); indulgent (high nurturance, low control); and uninvolved (low nurturance, low control). Parenting styles are based on the extent to which the parent adopts a nurturing and controlling communication style.

Several systematic reviews have examined whether parenting practices are related to child SV.16–18 These reviews suggest that a range of different parenting measures have been used, but the reliability and validity of those measures and inconsistencies in study design mean that more work on parental factors associated with child SV is needed.16–18 Self-efficacy to manage screen time has been associated with lower levels of television (TV) viewing among children,19 and there is some evidence that parental self-efficacy to manage SV is associated with lower SV among UK and Australian preschool-aged children.20,21 There is little information about whether parental self-efficacy to limit child screen time is associated with SV among children at the start of primary school, a key period for the development of obesity and SV behaviors.1

Sleddens has proposed a conceptual model of how parents influence children's diet and physical activity.22 Application of the model to SV and self-efficacy would suggest that any link between parental control/nurturance and child SV is likely to be partially mediated by parental self-efficacy to limit SV. The aims of this study were therefore to examine whether (1) parental control or parental nurturance were associated with SV in young children, (2) parent self-efficacy to limit SV was associated with SV in young children, and (3) any association between either parental control or parental nurturance and SV in young children was mediated by self-efficacy to limit screen time.

Methods

Data are from the B-ProAct1v cross-sectional study.23,24 Details of the study design have been reported elsewhere.23,24 Briefly, between January 2012 and July 2013, 250 primary schools were invited to participate in the study. Data were collected in 57 schools that responded and for which data collection could be scheduled.24 The study was approved by a University of Bristol (Bristol, UK) ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

A parent (mother or father) completed a questionnaire that included questions about their own SV behavior and that of their child, as well as parenting constructs. Parents reported their own and their child's SV, with separate questions relating to TV viewing and computer/laptop use. For each SV device, the parent was asked to report the time he or she and their child spent using it during a (1) normal weekday and (2) normal weekend day, with the following response options: none; 1–30 minutes; 31 minutes–1 hour; 1–2 hours; 2–3 hours; 3–4 hours; or >4 hours. The assessment of TV viewing using parental response to a single question has been shown to correlate moderately (r=0.60) with 10 days' of TV diaries among young children.25

Parental control and nurturance were measured using the Parental Dimension Index.26 The nurturance subscale consists of six items, including “I encourage my child to talk about his or her troubles.” Responses were measured on a Likert scale with a range of “Not at all like me” (scored as 1) to “Exactly like me” (scored as 6) and a total score of 6–36. The control subscale comprises five pairs of opposing statements with respondents being asked to choose the statement that they agree with most closely. The scale has a range of 0 (low control) to 5 (high control).

Parents' self-efficacy to reduce the child's SV behavior was measured using three questions that were based on Bandura's recommendations.27 The questions were: (1) “How much can you do to control the time your child spends SV (e.g., watching TV, digital video discs [DVDs], or playing video games)?”; (2) “How much can you do to help your children have alternatives to screen-viewing?”; and (3) “How much could you do to reduce the time your child spends screen-viewing?” Responses ranged from “Nothing” (scored 1) to “A great deal” (scored 5).

Parents self-reported height and weight, and BMI (kg/m2) was calculated. Home postcode was used to derive the index of multiple deprivation (IMD), with a higher score indicating greater deprivation.

Data Preparation

Based on the AAP guidance, children's TV viewing behavior was collapsed into two categories (<2 hours per day and ≥2 hours per day).3 Children's screen use for other devices was collapsed into two categories of “no use” and “some use.”

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Cronbach's alpha was used to investigate the internal consistency of the parenting variables. The parental nurturance scale was internally consistent (alpha=0.864). The parental control measure had low internal consistency (alpha=0.302), and exploratory factor analysis indicated that the items did not load onto a single factor. However, given the low number of items, we retained the summary variable in all analyses. A factor analysis indicated that all three items designed to measure parental efficacy to limit SV loaded onto the same extracted latent variable and had good internal consistency (alpha=0.879).

Differences between parental genders were examined using chi-square and Student's t-tests. Differences in key variables between parents and children who did and did not provide sufficient information to be included in this analysis were also examined.

Preliminary correlation tests were used to examine whether mediation could have occurred28 and whether there was an association between the control and nurturance variables. Parental control and nurturance were both correlated with parental self-efficacy to influence SV (r=0.16; p<0.001 and r=0.27; p<0.001, respectively). There was, however, no evidence of an association between parental control and nurturance (r=0.027), and as such, there was no basis for further examination of the link between these two variables in the models.

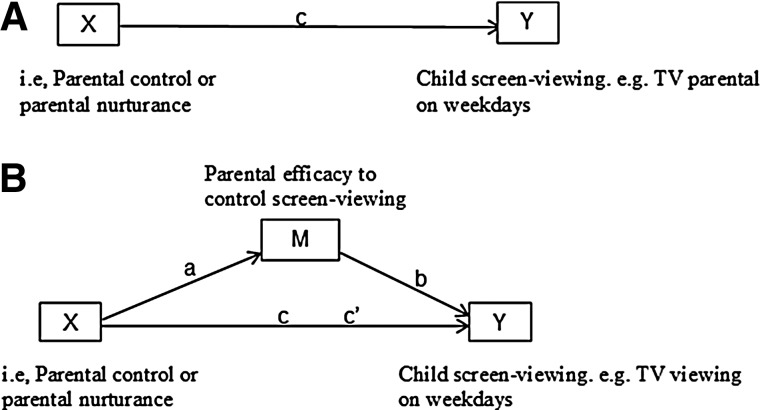

The hypothesis that any association between parental control or nurturance and child SV behavior was mediated by parental efficacy to influence SV (aims 1 and 3), was examined using the four-step regression approach recommended by Cerin and MacKinnon,28,29 which is summarized in Figure 1A and B. The four-step method involves testing a direct path between the exposure and the outcome and then estimating by how much this association is reduced by the inclusion of the potential mediator. We tested two exposures (parental control and nurturance) for each of four binary outcomes (TV viewing and personal computer [PC] use on weekdays and weekend days). Given that it is not possible to determine whether TV viewing and PC use occurred independently or concurrently, we performed all analyses for the two outcomes separately. It should be noted that, because Cerin and MacKinnon29 have argued that mediation can still occur in the absence of an association between the exposure variable and the outcome variable, we continued with the full mediation models, even in the absence of a direct association. Mediation was assumed to have occurred if a previously significant association between X and Y is no longer significant. Complete mediation of the pathway between the exposure and the outcome occurs when the effect of X on Y controlling for M (path c’) becomes zero.

Figure 1.

(A) Direct relationship between parental control/nurturance and child screen viewing behavior. (B) Relationship between parental control/nurturance and child screen viewing behavior mediated by parental self-efficacy. TV, television.

Models were adjusted for child BMI z-score, household IMD, and parent SV. Confidence intervals (CIs) were based on robust standard errors, which took account of the clustering of participants within schools. Mediation statistics, including the proportion mediated and the indirect effect, were obtained using a modified version of the user-written Stata “binary_mediation” command, and bias-adjusted 95% CIs were derived using bootstrapping methods.30 Preliminary analyses showed that including either parent or child sex had very little effect on the overall results or on R2 in the mediation models, and there was no evidence of an interaction with either child or parent sex. Therefore, all analyses are presented for the entire sample. Analyses were performed in Stata 12.0 (Statacorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 954 parents (708 mothers and 246 fathers) provided sufficient information to be included in the analyses (Table 1). Mothers had higher scores on the nurturance scale, compared to fathers (32.2 vs. 30.5; p<0.001). There was evidence to suggest that parents included in the analyses were more controlling (31.1 vs. 31.8; p=0.001), felt less able to limit SV (13.3 vs. 13.6; p=0.0149), and were from households with higher IMD scores (15.4 vs. 14.3; p<0.001; Supplementary Table 1) (see online supplementary material at http:www.liebertpub.com).

Table 1.

Characteristics of and Number of SV Devices in the Homes of Participants by Gender

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Difference in means | 95% CI | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Male parent (n=246) | Female parent (n=708) | |||||

| Age, years | 39.6 | 6.1 | 37.3 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 1.48 to 3.14 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 26.4 | 4.3 | 25.2 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 0.52 to 1.86 | <0.001 |

| IMD scorea | 13.1 | 11.3 | 14.7 | 12.4 | −1.6 | −3.37 to 0.14 | 0.072 |

| Parental self-efficacy to limit SV | 13.6 | 1.6 | 13.7 | 1.7 | −0.10 | −0.35 to 0.15 | 0.427 |

| Parental control | 3.7 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 0.10 | −0.05 to 0.26 | 0.190 |

| Parental nurturance | 30.5 | 4.3 | 32.2 | 3.7 | −1.73 | −2.29 to −1.17 | <0.001 |

| Media equipment (all) | 13.4 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 5.1 | 0.31 | −0.47 to 1.09 | 0.436 |

| TVs | 4.7 | 2.4 | 4.9 | 2.3 | −0.17 | −0.51 to 0.17 | 0.331 |

| PCs (including laptops and tablets) | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.20 | −0.01 to 0.40 | 0.060 |

| Games consoles | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.7 | −0.09 | −0.34 to 0.16 | 0.474 |

| Music players | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.15 | −0.10 to 0.39 | 0.236 |

| Smart phones | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.20 | 0.06 to 0.34 | 0.004 |

| Children | Boys (n=493) | Girls (n=461) | Difference in means | 95% CI | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 6.0 | 0.4 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 0.02 | −0.03 to 0.08 | 0.458 |

| BMI-z score | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.23 | 0.9 | 0.02 | −0.1.0 to 0.14 | 0.705 |

| IMD scorea | 14.5 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 11.8 | 0.32 | −1.22 to 1.86 | 0.688 |

A high score shows greater levels of social deprivation.

p value from t-tests.

IMD, index of multiple deprivation; SV, screen viewing; TVs, televisions; PCs, personal computers; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

SV was similar in boys and girls on weekdays and at the weekend (Table 2). On weekdays, 90% of children met guidelines of less than 2 hours of TV per day. At weekends, however, this figure decreased to 55% for boys and 58% for girls. Computer use by girls and boys was similar, with approximately 75% of both genders reportedly having some exposure to PCs at home on weekend days, compared with 61% on weekdays.

Table 2.

Demographic Data of Screen Viewing among Parents and Children

| Weekday | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||||||

| <2 hours | 2 hours or more | <2 hours | 2 hours or more | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | p value* | |||||

| Parent TV | 185 | 75.2 | 61 | 24.8 | 494 | 69.8 | 214 | 30.2 | 0.105 | ||||

| Child TV | 439 | 89.1 | 54 | 10.9 | 421 | 91.3 | 40 | 8.7 | 0.238 | ||||

| ≤30 minutes | 31 minutes to 2 hours | >2 hours | ≤30 minutes | 31 minutess to 2 hours | >2 hours | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Parent PC | 79 | 32.1 | 91 | 37.0 | 76 | 30.9 | 283 | 40.0 | 281 | 39.7 | 144 | 20.3 | 0.002 |

| Not used | Any use | Not used | Any use | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Child PC | 183 | 37.1 | 310 | 62.9 | 183 | 39.7 | 278 | 60.3 | 0.413 | ||||

| Weekend day | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||||||

| <2 hours | 2 hours or more | <2 hours | 2 hours or more | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Parent TV | 119 | 48.4 | 127 | 51.6 | 346 | 48.9 | 362 | 51.1 | 0.893 | ||||

| Child TV | 271 | 55.0 | 222 | 45.0 | 268 | 58.1 | 193 | 41.9 | 0.324 | ||||

| ≤30 minutes | 31 minutes to 2 hours | >2 hours | ≤30 minutes | 31 minutes to 2 hours | >2 hours | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Parent PC | 17 | 6.9 | 102 | 41.5 | 127 | 51.6 | 46 | 6.5 | 300 | 42.4 | 362 | 51.1 | 0.955 |

| Not used | Any use | Not used | Any use | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Child PC | 120 | 24.3 | 373 | 75.7 | 117 | 25.4 | 344 | 74.6 | 0.711 | ||||

p value from chi-square tests showing differences in associations between males and females.

TV, television; PC, personal computer.

Logistic regression analysis indicated that for parental TV watching behavior on weekdays, each unit increase in parental control score was associated with a 26% reduction in the odds of a child watching >2 hours of TV per weekday (odds ratio [OR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58–0.93; Table 3). Parental efficacy to influence SV was independently associated with the odds of children watching <2 hours of TV per weekday (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68–0.83), and there was some evidence that parental efficacy mediated the path between parental control and children's weekday TV viewing behavior. Including the potential mediator reduced the odds of a child watching >2 hours of TV per weekday to 20% (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.64–1.00). The proportion of the total effect mediated was 23%. There was limited evidence that parental nurturance was associated with children's TV watching (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90–1.02). There was, however, some evidence that the path between these variables was mediated by parental efficacy to influence SV (mediated OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.93–1.05; proportion of the total effect mediated was 71%; Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Predicting Child TV Watching Behavior on Weekdays by Parental Control and Parental Nurturance, with Parental Efficacy To Restrict Screen Viewing as a Potential Mediator

| Parental control | Adjusteda (with clustering) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Outcome=child TV on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental control (C) | 0.74 | 0.58–0.93 | 0.009 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.118; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2a: Predictor: parental control | Coeff | 95% CI | p |

| (a) Outcome: efficacy to influence screen viewing (A1) | 0.25 | 0.14–0.36 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.033; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2b: Mediator on outcome | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing (B) | 0.75 | 0.68–0.83 | <0.001 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.143; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 3: Outcome=child TV on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental control (C’) | 0.80 | 0.64–1.00 | 0.056 |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.150; p<0.001 | |||

| Mediation statistics: | Bias-corrected 95% CI | ||

| Indirect effect | −0.04 | −0.06 to −0.02 | |

| Proportion of total effect mediated | 0.23 | ||

| Parental nurturance | Adjusteda (with clustering) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Outcome=child TV on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental control (C) | 0.95 | 0.90–1.02 | 0.139 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.109; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2a: Predictor: parental nurturance | Coeff | 95% CI | p |

| (a) Outcome: efficacy to influence screen viewing (A1) | 0.12 | 0.09–0.15 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.085; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2b: Mediator on outcome | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing (B) | 0.75 | 0.68–0.83 | <0.001 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.143; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 3: Outcome=child TV on weekdaysb | OR | 95%CI | p |

| Parental nurturance (C’) | 0.99 | 0.93–1.05 | 0.672 |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing | 0.76 | 0.68–0.84 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.143; p<0.001 | |||

| Mediation statistics: | Bias-corrected 95% CI | ||

| Indirect effect | −0.07 | −0.10 to −0.04 | |

| Proportion of total effect mediated | 0.71 | ||

Adjusted for child BMI z-score, IMD, and parental weekday TV viewing.

>2 hours versus 2 hours or less.

TV, television; IMD, index of multiple deprivation; OR, odds ratio; Coeff, coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Children's weekday PC use was not predicted by parental control (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89–1.10), and there was no evidence of mediation by parental efficacy to influence SV (indirect effect, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.04 to −0.01; proportion of total effect mediated=2.89%; Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Predicting Child PC Use on Weekdays by Parental Control and Parental Nurturance, with Parental Efficacy To Restrict Screen Viewing as a Potential Mediator

| Parental control | Adjusteda (with clustering) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Outcome=child PC use on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental control (C) | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.864 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.023; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2a) Predictor: parental control | Coeff | 95% CI | p |

| (a) Outcome: Efficacy to influence screen viewing (A1) | 0.25 | 0.14–0.36 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.031; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2b: Mediator on outcome | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing (B) | 0.88 | 0.82–0.95 | 0.001 |

| Pseudo-R2 0.031; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 3: Outcome=child PC use on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental control (C’) | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 0.709 |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing | 0.88 | 0.81–0.81 | 0.001 |

| R2, 0.031; p<0.001 | |||

| Mediation statistics: | Bias-corrected 95% CI | ||

| Indirect effect | −0.02 | −0.04 to −0.01 | |

| Proportion of total effect mediated | 2.89 | ||

| Parental nurturance | Adjusteda (with clustering) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Outcome=child PC use on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental nurturance (C) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.044 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.026; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2a: Predictor: parental nurturance | Coeff | 95% CI | p |

| (a) Outcome: efficacy to influence screen viewing (A1) | 0.12 | 0.09–0.15 | <0.001 |

| R2, 0.084; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 2b: Mediator on outcome | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing (B) | 0.88 | 0.82–0.95 | 0.001 |

| Pseudo-R2, 0.031; p<0.001 | |||

| Step 3: Outcome=child PC use on weekdaysb | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Parental nurturance (C’) | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.268 |

| Efficacy to influence screen viewing | 0.89 | 0.82–0.96 | 0.004 |

| R2, 0.032; p<0.001 | |||

| Mediation statistics: | Bias-corrected 95% CI | ||

| Indirect effect | −0.03 | −0.05 to −0.01 | |

| Proportion of total effect mediated | 0.41 | ||

Adjusted for child BMI z-score, IMD, and parental weekday PC use.

Some use versus no use.

PC, personal computer; IMD, index of multiple deprivation; OR, odds ratio; Coeff, coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Each unit increase on the parental nurturance scale was associated with a 3% decrease in the odds of a child using a PC on weekdays (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94–1.00). There was evidence that parental efficacy to influence SV partially mediated the path between these two variables, with a significant proportion (41%) of the total effect being mediated (revised OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.95–1.02; Table 4).

Neither parental control nor nurturance were directly associated with children's weekend TV viewing, although there was evidence that the direct pathway in both models was mediated by parental efficacy to influence SV (Supplementary Table 2) (see online supplementary material at http:www.liebertpub.com). Weekend PC use was not significantly predicted by either of the parenting variables, nor was there any evidence of mediation by parental efficacy to influence SV (Supplementary Table 3) (see online supplementary material at http:www.liebertpub.com).

Discussion

In this study, 45% of boys and 42% of girls spent more than 2 hours watching TV on a weekend day, with just over half of parents exceeding this threshold. There was strong evidence that parental control was associated with child weekday TV viewing, with each unit increase on the parent control scale associated with a 26% reduction in the odds that a child spent >2 hours per day watching TV. Parental self-efficacy to limit SV was associated with 5- to 6-year-old children's weekday and weekend TV watching and PC use on weekdays, with each unit increase on the scale being associated with a 25% reduction in the odds that a child spent >2 hours watching TV on weekdays. At weekends, the equivalent reduction was 12%. Parental self-efficacy mediated the path between both control (23%) and nurturance (71%) and weekday TV viewing. For PC use, there was some evidence that parental nurturance was associated with child PC use, but the association was weak. There was no evidence of an association between parental control and PC use on either weekdays or weekend days. Parental self-efficacy to limit SV was strongly associated with PC time, with each unit on the scale associated with a 12% reduction in the odds that children were using PCs. Self-efficacy mediated 41% of the path between nurturance and weekday PC use. Overall, the results highlight weak effects for the more distal control and nurturance and an important role for the proximal parental self-efficacy variable. It is important to note that parental self-efficacy may vary for different behaviors and in different situations. Strategies to boost self-efficacy for specific behaviors may help to change behaviors and enhance overall behavior change, even when the parent is under stress.

Our results suggest that developing an intervention focusing on increasing parents' awareness of the importance of limiting SV and enhancing confidence to say “no” or to offer their children alternative activities to SV that may reduce SV, which may also aid in the prevention of obesity. The impact of higher parental self-efficacy was greater on a weekday (25% reduction in odds of watching more than 2 hours of TV) than a weekend day (12% reduction). This difference may reflect the greater time available for children to SV at the weekend because, even if a parent were to assert their efficacy to offer valued alternatives on some occasions to SV, there are likely to be other times in the weekend day when their child is permitted to engage in SV behavior. Conversely, on weekdays, a parent may only need to assert their efficacy once or twice to set up alternative activities (a club or playing outside), which can fill a few hours before dinner and reduce SV for that day. The findings presented here therefore complement emerging research showing that parenting programs concentrating on parental skills to manage screen time among older children31 are useful and suggest that programs that focus on both weekday and weekend SV could be helpful.

These data raise several methodological issues in relation to the measurement of parenting styles. First, our preliminary analysis indicated that the control measure had low internal consistency. The measure was developed in the United States,26 and the low internal consistency may reflect differences between UK and US respondents, suggesting that further UK measurement work is needed. Second, the derivation and interpretation of categories of parenting styles may warrant reconsideration. Previous research has shown that authoritative parenting, which is characterized by higher levels of control and nurturance, is associated with positive child outcomes.12,13,32–35 The data presented in this article suggest that the variables typically used to derive parenting styles do not seem to impact on SV behaviors in the same way that they do on other behaviors. The lack of association seems inconsistent with findings from previous parenting studies, but might be a consequence of using the disaggregated variables. Previous studies have forced the derivation of four groups based on median splits of control and parenting variables. The median split approach also makes it hard to identify how control and nurturance are independently associated with health behaviors, and future studies should consider reporting how nurturance and control are independently associated with health outcomes. The results of this study are therefore broadly consistent with the recent recommendations of Power and colleagues for the development of new measures to measure parenting constructs in a variety of different contexts.36 Finally, our results appear to broadly support the model proposed by Sleddens and colleagues22 that any impact of parenting styles on health outcomes is likely to be mediated by parenting practices.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study is the availability of SV time for both parent and child along with parental perceptions of factors considered to be important in the role of limiting the amount of children's SV behavior. This facilitated the examination of such factors as they relate to children who have recently begun primary (elementary) school. The study is limited by the parental report of child SV, which is likely to be subject to an under-reporting bias. We have attempted to minimize this by including the parental SV in the models, given that it is reasonable to assume that a parent who tends to underestimate their own SV time is likely to underestimate their child's by a similar amount. The cross-sectional nature of the study design limits the ability to identify the direction of associations. Finally, it is important to recognize that there are several limitations of applying mediation analyses to cross-sectional data with binary outcomes. Based on the recommendations for Cerin and Makinnon,29 we applied the product-of-coefficients method to estimate any mediation effects, but are aware of the possible limitations of this approach.37,38 While recognizing the limitations of mediation analysis, we are confident that the overall results for the model used are robust.

Conclusions

Results presented here show that parental self-efficacy to limit SV was associated with lower levels of SV among 5- to 6-year-old children, and that parental self-efficacy partially mediated the association between parental control and TV viewing. Results suggest that the development of strategies to increase parental self-efficacy to limit screen time may be useful for reducing screen time and preventing the development of behaviors that increase the risk of childhood obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a project grant from the British Heart Foundation (ref PG/11/51/28986). The funder had no involvement in data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the paper. The authors thank all the children, parents, and schools that participated in the study. The authors also thank members of the project team that are not authors on this article for their contributions.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, et al. BMI from 3–6 y of age is predicted by TV viewing and physical activity, not diet. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2005;29:557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekelund U, Brage S, Froberg K, et al. TV viewing and physical activity are independently associated with metabolic risk in children: The European Youth Heart Study. PLoS Med 2006;3:e488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasburger VC. Children, adolescents, obesity, and the media. Pediatrics 2011;128:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Health and Social Care Information Center. Health Survey for England 2008: Volume 1 Physical Activity and Fitness. The Health and Social Care Information Center: London, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biddle SJ, Pearson N, Ross GM, et al. Tracking of sedentary behaviours of young people: A systematic review. Prev Med 2010;51:345–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions. How are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med 1998;15:266–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranowski T, Jago R. Understanding mechanisms of change in children's physical activity programs. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2005;33:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as a context: An integrative model. Psychol Bull 1993;113:487–496 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Devel Psychol Mono 1971;4:101–103 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventura AK, Birch LL. Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, Mussen PH. (eds), Socilization, personality, and social development. Wiley: New York, 1983, pp. 1–101 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, et al. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev 1987;58:1244–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spera C. A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles and adolescent school achievement. Educ Psychol Rev 2005;17:125–145 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremers SP, Brug J, de Vries H, et al. Parenting style and adolescent fruit consumption. Appetite 2003;41:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick H, Nicklas TA, Hughes SO, et al. The benefits of authoritative feeding style: Caregiver feeding styles and children's food consumption patterns. Appetite 2005;44:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jago R, Edwards MJ, Urbanski CR, et al. General and specific approaches to media parenting: A systematic review of current measures, associations with screen-viewing, and measurement implications. Child Obes 2013;9(Suppl):S51–S72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duch H, Fisher EM, Ensari I, et al. Screen time use in children under 3 years old: A systematic review of correlates. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connor TM, Hingle M, Chuang RJ, et al. Conceptual understanding of screen media parenting: Report of a working group. Child Obes 2013;9(Suppl):S110–S118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyos Cillero I. Individual and social predictors of screen-viewing among Spanish school children. Eur J Pediatr 2011;170:93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell K, Hesketh K, Silverii A, et al. Maternal self-efficacy regarding children's eating and sedentary behaviours in the early years: Associations with children's food intake and sedentary behaviours. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010;5:501–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jago R, Sebire SJ, Edwards MJ, et al. Parental TV viewing, parental self-efficacy, media equipment and TV viewing among preschool children. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:1543–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleddens EF, Gerards SM, Thijs C, et al. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: A review. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:e12–e27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jago R, Thompson JL, Sebire SJ, et al. Cross-sectional associations between the screen-time of parents and young children: Differences by parent and child gender and day of the week. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jago R, Sebire SJ, Wood L, et al. Associations between objectively assessed child and parental physical activity: A cross-sectional study of families with 5–6 year old children. BMC Public Health 2014;14:655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson DR, Field DE, Collins PA, et al. Estimates of young children's time with television: a methodological comparison of parent reports with time-lapse video home observation. Child Dev 1985;56:1345–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Power TG. Parenting Dimensions Inventory (PDI-S): A research manual. Unpublished manuscript. Washington State University: Pullman, WA, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan TC. (eds), Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Information Age: Greenwich, CT, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron RM, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerin E, Mackinnon DP. A commentary on current practice in mediating variable analyses in behavioural nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:1182–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ender P. binary_mediation: Mediation with binary mediator and/or binary response variable. In: binary_mediation: Mediation with Binary Mediator and/or Binary Response Variable. UCLA, Statistical Consulting Group: LOs Angeles, CA, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jago R, Sebire SJ, Turner KM, et al. Feasibility trial evaluation of a physical activity and screen-viewing course for parents of 6 to 8 year-old children: Teamplay. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfradt U, Hempel S, Miles J. Perceived parenting styles, depersonalization, anxiety and coping behavior in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 2003;34:521–532 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J, Balhorn ME, et al. A social learning perspective: A model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25:1284–1292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee KE, Lumeng JC, Appugliese DP, et al. Parenting styles and overweight status in first grade. Pediatrics 2006;117:2047–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wake M, Nicholson JM, Hardy P, et al. Preschooler obesity and parenting styles of mothers and fathers: Australian national population study. Pediatrics 2007;120:e1520–e1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Power TG, Sleddens EF, Berge J, et al. Contemporary research on parenting: Conceptual, methodological, and translational issues. Child Obes 2013;9(Suppl):S87–S94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:1339–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 2013;18:137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.