Abstract

Neural progenitor cells are usually derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) through the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs), the three-dimensional (3D) aggregate-like structure mimicking embryonic development. Cryo-banking of EBs is a critical step for sample storage, process monitoring, and preservation of intermediate cell populations during the lengthy differentiation procedure of PSCs. However, the impact of microenvironment (including 3D cell organization and biochemical factors) of EBs on neural lineage commitment postcryopreservation has not been well understood. In this study, intact EBs (I-E) and dissociated EBs (D-E) were compared for the recovery and neural differentiation after cryopreservation. I-E group showed the enhanced viability and recovery upon thaw compared with D-E group due to the preservation of extracellular matrix, cell–cell contacts, and F-actin organization. Moreover, both I-E and D-E groups showed the increased neuronal differentiation and D-E group also showed the enhanced astrocyte differentiation after thaw, probably due to the modulation of cellular redox state indicated by the expression of reactive oxygen species. In addition, mesenchymal stem cell secretome, known to bear a broad spectrum of protective factors, enhanced EB recovery. Taken together, EB microenvironment plays a critical role in the recovery and neural differentiation postcryopreservation.

Introduction

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced PSCs, emerge as powerful tools for the treatment of various neurological disorders.1,2 Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) isolated from adult brain tissues are limited in cell number and display gradual telomere shortening.3 Therefore, NPCs derived from PSCs provide attractive cell sources for neural tissue repair and regeneration.1,4 Transplantation of PSC-derived NPCs has been shown to ameliorate the functional outcomes of stroke, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and spinal cord injury, and others.5–7 PSC-derived NPCs can also form stratified neural retina or cerebral brain organoid for drug screening and disease modeling.8–10 For all these applications, development of an efficient cryopreservation process amenable for the distribution and storage of PSC-derived NPCs with desired three-dimensional (3D) structure is a critical step to ensure the cell quality and to accelerate the derivation of different neural cell types.4,11–13

NPCs are usually derived from PSCs through the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs), the aggregate structure mimicking embryonic development.9,14 NPC derivation from PSCs has a lengthy procedure that could last up to 6–14 weeks.10,15,16 Cryo-banking of EBs for NPC derivation provides a necessary step for sample storage, process monitoring, and preservation of the intermediate cell populations.17 During EB cryopreservation, the 3D cell organization is a critical parameter to maintain the recovered cell properties.17 For adult neurospheres, disruption of 3D cell organization has been shown to reduce the efficiency of terminal neuronal differentiation.18,19 For PSC-derived NPCs, cryopreservation of the dissociated single cells caused significant apoptosis and required treatment with Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitors or caspase inhibitors to maintain cell viability.11,20 Although cryopreservation of adult neurospheres is feasible, cryopreservation of EBs for neural differentiation has not been well studied. To date, there are only a few studies for cryopreservation of spontaneously differentiated EBs.17,21 Especially, the impacts of EB organization and cryopreservation process on neural lineage commitment of EBs post-thaw have not been fully characterized.

Aggregate-based cryopreservation can preserve cell–cell contact and extracellular matrix (ECM) microenvironment, which are beneficial for cell recovery post-thaw. Cryopreservation of adult NPCs as small intact neurospheres (30–100 μm) resulted in high viability possibly due to the preservation of cell–cell contact.19 To avoid aggregate fragmentation, encapsulation method was incorporated with slow-cooling procedure to preserve intact neurospheres.22 Our previous study cryopreserved undifferentiated PSC aggregates in a defined protein-free formulation,23 which showed that maintaining cell–cell contact and ECM structure could reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and caspase expression in small PSC aggregates.23,24 Given the importance of ROS and caspase in regulating cell survival, the secretome of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has also been investigated in our previous study to promote ECM secretion from PSC-derived NPC aggregates.24 Taking one step further, this study evaluated the cryopreservation effect on the differentiated PSC aggregates (i.e., EBs) for neural lineage commitment.

Specifically, this study investigated the effects of EB structural organization on cell recovery and neural differentiation post-thaw. The hypothesis is that the EB microenvironment and cryopreservation may differentially regulate neural lineage commitment post-thaw due to the modulation of ECMs and cellular redox state. The influence of MSC secretome, known to possess high antioxidant properties,25 was investigated to modulate oxidative environment of EBs. This study assessed the suitability of cryopreserving EBs and revealed the role of cellular microenvironment on cell recovery and neural lineage commitment after EB cryopreservation and thaw.

Materials and Methods

Undifferentiated ESC culture and generation of EBs

Murine ES-D3 line (Cat# CRL-1934; American Type Culture Collection) was maintained on 0.1% gelatin-coated six-well plates (Millipore) in a standard 5% CO2 incubator. The expansion medium is composed of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% ESC-screened fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Invitrogen), and 1000 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF, Cat# ESG1106; Millipore). The cells were seeded at 2–4×104 cells/cm2 and subcultured every 2–3 days.

To generate EBs, ESCs were seeded at 1×106 cells into ultra-low attachment six-well plates (Corning Incorporated) in 3 mL of DMEM-F12 plus 2% B-27 serum-free supplement (Cat# 17504-044; Invitrogen), which was referred as neural differentiation medium. The formed EBs were cultivated for 4 days. At day 4, 1 μM all-trans retinoic acid (Cat# R2625; Sigma-Aldrich) was added in the media to induce neural differentiation.26 EBs were cultivated for another 4 days and then collected at day 8 (about 300–400 μm in diameter) for cryopreservation study (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental procedure. (A) Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were seeded as embryoid bodies (EBs) in DMEM/F12-B27 for 4 days. Afterward the medium was supplemented with retinoic acid (RA) for another 4 days. (B) The aggregates were collected and cryopreserved as intact EBs (I-E). Alternatively EBs were dissociated and cryopreserved as single cells (D-E). I-E and D-E cells were thawed and immediately replated on Geltrex-coated surface for 3–5 days to assess the cell recovery and differentiation potential. DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Cryopreservation of EBs

The collected EBs were cryopreserved either as intact EB aggregates (I-E) or as single cells after dissociation with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA, that is, dissociated EBs (D-E) (Fig. 1B). For the I-E group, ∼50 aggregates in 250 μL media were taken and dissociated. The resulting single cells were counted by hemacytometer. This number was used to estimate the cell concentration of I-E cells. Based on the calculated cell concentration, different volumes of suspension were taken to obtain the samples with 1×105, 5×105, or 1×106 cells. For the D-E group, a 20 μL of single cell suspension were counted directly. The aggregates or the single cells were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 90% FBS plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Figs. 2–8) or 90% HypoThermosol® FRS (HTS-FRS; BioLife Solutions) plus 10% DMSO (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec).23 A fixed number of cells (1×105, 5×105, or 1×106 cells in 1 mL) were placed into cryogenic vials for 10–15 min. The vials were transferred into the StrataCooler® Cryo Preservation Module (Agilent Technologies) and put in a −80°C freezer overnight. The cooling rate was 0.4–0.6°C/min. For long-term use, the cells were stored in liquid nitrogen. The frozen cells were quickly thawed at 37°C, immediately counted (for aggregates, a sample was taken and dissociated for counting) and analyzed for cell membrane integrity (i.e., viability) using Live/Dead assay. The cell recovery immediately post-thaw was calculated as the counted viable cell number upon thaw divided by the frozen cell number. The recovered aggregates or the single cells were then seeded into 24-well plates coated with Geltrex (major component is laminin, Cat# A1413202; Life Technologies) to evaluate fold of expansion (Fig. 1B). The fold of expansion at passage 1 (P1) post-thaw was calculated as the harvested cell number 3 days after cell thawing divided by the cell number immediately post-thaw.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of EBs before and after cryopreservation. Morphology of EBs before cryopreservation: (A) intact EBs (I-E); (B) dissociated EBs (D-E). (C–F) Neural differentiation of EBs before cryopreservation was indicated by the expressions of neural markers (stained after overnight replating): (C) Nestin, (D) Musashi 1, (E) β-tubulin III, and (F) GFAP. (G) Morphology of I-E cells day 0 post-thaw; (H) Morphology of D-E cells day 0 post-thaw. (I) Morphology of I-E cells day 2 post-thaw; (J) Morphology of D-E cells day 2 post-thaw. (K) I-E cells without cryopreservation; (L) D-E cells without cryopreservation. Scale bar: 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 3.

Recovery of intact and dissociated EBs upon thaw and the effects of cell density during cryopreservation. (A) Representative images of membrane integrity (i.e., viability) upon thaw of D-E and I-E cells. Green: live cells labeled with membrane-permeant calcium AM; Red: dead cells labeled with ethidium homodimer-1 showing compromised membrane; Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Cell viability upon thaw (ANOVA F-value=9.41, p-value<0.01); (C) Cell number recovery upon thaw (n=4), (ANOVA F-value=0.89, p-value=0.49); (D) Expansion fold after 3 days post-thaw (ANOVA F-value=10.83, p-value<0.01). *p-value<0.05. ANOVA, analysis of variance. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 4.

Extracellular matrix expression of intact and dissociated EBs upon thaw. (A) Confocal images of fibronectin (FN), laminin (LN), collagen type IV (COL IV), and vitronectin (VN) in I-E and D-E cells upon thaw. Arrows indicate single cells expressing ECM proteins. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of ECM expression in 1×106 D-E cells (ANOVA F-value=72.16, p-value<0.01); (C) Quantitative analysis of ECM expression in 1×106 I-E cells (ANOVA F-value=72.26, p-value<0.01). (B, C) were quantified by colorimetric immunoassays. *p-value<0.05. ECM, extracellular matrix. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 5.

F-actin organization in intact and dissociated EBs after cryopreservation. (A) Representative images of F-actin expression in D-E and I-E cells. The white arrows indicated the nearby aggregates. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Percentage of cells in D-E and I-E groups displaying polymerized actin (ANOVA F-value=14.44, p-value<0.01). *p-value<0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 6.

Neural lineage commitment of the intact and dissociated EBs after cryopreservation. (A) Representative fluorescent images of neural markers. (a-d) Without cryopreservation: (a) β-tubulin III expression in D-E cells; (b) GFAP expression in D-E cells; (c) β-tubulin III expression in I-E cells; (d) GFAP expression in I-E cells. (e–h) Postcryopreservation: (e) β-tubulin III expression in D-E cells; (f) GFAP expression in D-E cells; (g) β-tubulin III expression in I-E cells; (h) GFAP expression in I-E cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms of Nestin, β-tubulin III, GFAP, and Musashi 1. Red line: isotype control; Black line: without cryopreservation; Blue line: postcryopreservation. (C) Percentages of neural marker expression with or without cryopreservation (ANOVA F-value=4.04 and p-value=0.09 for Nestin; F-value=10.83 and p-value=0.02 for Musashi 1; F-value=6.14 and p-value=0.01 for β-tubulin III; F-value=7.58 and p-value=0.01 for GFAP). *p-value<0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 7.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and caspase activation in EBs after cryopreservation. (A) Representative fluorescent images of ROS expression after cryopreservation for various medium conditions. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) The percentage of ROS-positive cells (ANOVA F-value=4.13, p-value=0.05). (C) Flow cytometry histograms of caspase expression after cryopreservation. (D) The percentage of caspase-positive cells (ANOVA F-value=14.18, p-value<0.01). *p-value<0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

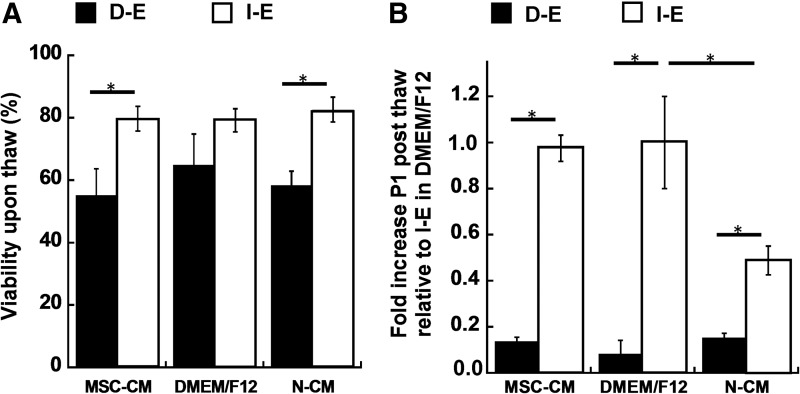

FIG. 8.

Recovery of intact and dissociated EBs preconditioned in mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium (MSC-CM). (A) Cell viability of D-E and I-E cells immediately post-thaw (ANOVA F-value=6.6, p-value<0.01); (B) Expansion fold at passage 1 (P1) post-thaw (3 days) for D-E and I-E cells relative to control (I-E cells in DMEM/F12 plus 2% B27) (ANOVA F-value=154.0, p-value<0.01). *p-value<0.05.

Live/Dead, reactive oxygen species, and poly caspase assays

Live/Dead assay

Cell membrane integrity was assessed using LIVE/DEAD® staining kit (Cat# L3224; Molecular Probes).23 The aggregates and single cells were incubated in DMEM containing 1 μM calcein AM and 1 μM ethidium homodimer I for 30 min. The samples were then washed and imaged under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX70) or a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS). Multiple levels of aggregate analysis showed high viability (Supplementary Fig. S1). Using ImageJ software, the staining intensity (red for dead cells and green for live cells) was measured and each value was subtracted from the background intensity. The viability was calculated as the percentage of green intensity over total intensity.

ROS assay

ROS detection was performed using Image-iT™ Live Green Reactive Oxygen Species Detection kit (Cat# I36007; Molecular probes).23 Briefly, the I-E and D-E were washed in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and incubated in a solution of 25 μM carbioxy-H2DCFDA for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were then washed and analyzed under fluorescence microscope. As positive controls, the cells (both I-E and D-E groups) were incubated in a 100 μM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) solution, prior to staining with carboxy-H2DCFDA.

Caspase assay

Caspases (caspase-1, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, and -9) were detected using Image-iT Live Green Poly Caspase Detection Kits (Cat# I35104; Molecular Probes). Caspases-8 and -9 are initiator caspase and caspases-3, -6, and -7 are effector caspase.27 Briefly, I-E and D-E cells were incubated for 1 h with the fluorescent inhibitor of caspases (FLICA) reagent and analyzed under fluorescence microscope.23 For quantification, the caspase-stained samples (after dissociation into single cells) were acquired with BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo software against the nonstained samples.

ECM expression pre- and postcryopreservation

For ECM expression, cells from I-E and D-E groups were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) immediately upon thaw. The samples were permeabilized with 0.2–0.5% Triton X-100, blocked, and incubated with primary ECM antibodies, including rabbit polyclonal fibronectin (FN, ab23750), laminin (LN, ab11575), collagen IV (Col IV, ab6586), and vitronectin (VN, ab28023) (Abcam). For fluorescence staining, the samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-Rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes), counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2- phenylindole (DAPI), and visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70) or a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS).

To quantify the ECM contents, the same number of cells (1×106) from I-E and D-E groups pre- and postcryopreservation were incubated with donkey anti-Rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Rockland Immunochemicals) after the incubation with primary antibodies. After washing, 1 mL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Thermo scientific) was added to the samples and incubated for 5–25 min. The reaction was stopped by a solution of 0.16 M sulfuric acid. The absorbance units (AU) were measured using a microplate reader (Biorad) at a wavelength of 405 nm with background subtraction at 655 nm. The AU values were also corrected by subtracting the absorbance of negative control stained with HRP-IgG only.28

F-actin staining

Actin organization was assessed as reported previously.29 Cells from I-E and D-E groups before and after cryopreservation were seeded on Geltrex-coated surface for 24 h in neural differentiation medium, fixed with 4% PFA, and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 solution. The samples were then incubated for 30 min with Alexa Fluor 594 Phalloidin (A12381; Molecular Probes) and mounted in a mounting solution containing DAPI (Vectashield). The samples were washed and imaged under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX70). F-actin polymerization shown as stress fibers and cortical actin was also quantified using ImageJ software.

Immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry analysis of neural markers

After 3 days in neural differentiation medium without any growth factors, the replated D-E and I-E cells were assessed by immunocytochemistry for neural marker expression. Briefly, the cells were fixed in 4% PFA and permeabilized with 0.2–0.5% Triton X-100. The samples were then blocked and incubated with mouse or rabbit primary antibody against Nestin (N5413; Sigma) and Musashi 1 (ab52865; Abcam), both as neural progenitor markers, β-tubulin III (MAB1637; Millipore) as a marker for neurons, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, MAB360; Millipore) as a marker for astrocytes. After washing, the cells were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-Mouse IgG1 (for GFAP and β-tubulin III) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-Rabbit IgG (for Nestin and Musashi 1). After washing and mounting in the DAPI-containing solution, the cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

To quantify the levels of differentiation marker expression, flow cytometry analysis was performed.24 The cells after 5 days were dissociated by trypsin/EDTA into single cells. About 1×106 cells per sample were fixed with 4% PFA and washed with staining buffer (2% FBS in PBS). The cells were permeabilized with 100% cold methanol and blocked using a 5% FBS solution in PBS. The samples were then incubated with primary antibodies against Nestin, β-tubulin III, GFAP, or Musashi 1 followed by the corresponding secondary antibody: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-Mouse IgG1 or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-Rabbit IgG. The samples were acquired with BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed against isotype controls using FlowJo software. The average values from three independent experiments were presented.

EBs preconditioned with human MSC conditioned medium

Conditioned media from human MSCs (MSC-CM) were kindly provided by the lab of Dr. Teng Ma as previously described.24 MSC-CM was mixed at 50% v/v with DMEM/F12 plus 2% B27 media to treat EBs, referred as the MSC-CM group. αMEM without conditioning was also mixed with DMEM-F12 plus 2% B27 media for comparison, referred to as the non-conditioned medium (N-CM) group. The DMEM-F12 plus 2% B27 medium was referred as the DMEM/F12 group. I-E and D-E cells were cultivated for 2 days in the presence of three medium conditions before cryopreservation. The viability, ROS and caspase expression of I-E and D-E cells were evaluated upon thaw after cryopreservation. The cells were replated in the medium corresponding to the precryopreservation culture for 3 days and evaluated for fold increase.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was carried out at least three times. The average values of two or three independent experiments were presented and the results are expressed (mean±mean absolute deviation). In each experiment, triplicate samples were used. To assess the statistical significance, one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's LSD post hoc tests were used. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cellular organization regulated EB recovery

EBs were formed as spherical aggregates and can be dissociated into single cells after the treatment with trypsin/EDTA (Fig. 2A, B). The EBs had abundant expression of neural progenitor markers Musashi 1 (75%±8%) and Nestin (61%±6%), low levels of β-tubulin III (neurons) (11%±4%) and GFAP (astrocytes) (9%±4%) (Fig. 2C–F), and they were capable of differentiating into neural cells.24 To evaluate the effect of cellular organization, the formed aggregates were cryopreserved either as intact EBs (I-E) or dissociated EBs (D-E). Immediately post-thaw, I-E cells displayed less distinct spherical morphology compared to the noncryopreserved group, while D-E groups remained as single cells (Fig. 2G, H). After 2 days in culture, replated I-E cells displayed dense neurite projections around the aggregates compared to the noncryopreserved group, indicating efficient recovery post-thaw (Fig. 2I, K). Conversely, more debris was observed for D-E group and the replated cells showed more flat and spread morphology compared to the noncryopreserved group (Fig. 2J, L).

The effects of cryopreserved cell density (1×105, 5×105, and 1×106 cells/mL) on cell viability and recovery post-thaw were assessed for I-E and D-E groups. For all the densities, lower cell viability (70–72% vs. 82–96%) was observed for D-E groups compared to I-E groups (p<0.05 for 1×105 and 1×106 cells/mL) (Fig. 3A, B). There was no significant difference in cell viability for the three cell densities within D-E or I-E groups. Immediately post-thaw, the cell number was about 60% of the frozen numbers, indicating the cell loss during the process of loading and unloading cryoprotectant buffer (Fig. 3C). There was no statistical difference in cell recovery between the I-E and D-E groups and among various cell densities. After 3 days in culture, D-E groups showed significantly lower expansion fold compared with I-E groups, especially for high cell density (0.39±0.03 vs. 0.68±0.15 for 1×106 cells/mL) (Fig. 3D). The expansion fold of the recovered cells was slightly lower compared with the noncryopreserved cells (e.g., 0.7–1.1 for I-E cells and 0.4–0.6 for D-E cells). These results indicated that intact EBs improved cell viability and cell recovery post-thaw compared with the dissociated EBs. The high cell density of 1×106 cells/mL was used in the subsequent studies.

Intact EBs preserved ECM expression and F-actin distribution

To assess the preservation of aggregate microenvironment, ECM expressions (including FN, LN, COL IV, and VN) of D-E and I-E cells were determined upon thaw prior to the replating on Geltrex-coated surface (Fig. 4A). From the confocal images, the dense ECM networks of FN, LN, COL IV, and VN were preserved among the cells for I-E group similar to the pattern prior to cryopreservation, while ECM expression in D-E cells was restricted to the cell body. Quantitatively, the expression of all four ECM proteins was significantly decreased by two to three-folds in D-E group after cryopreservation compared with the D-E cells without cryopreservation (Fig. 4B). For I-E group, no significant difference was observed for FN and LN expressions after cryopreservation, but the expressions of COL IV and VN decreased two to three-folds (Fig. 4C). These data indicated that cryopreservation may disrupt ECM structure but intact EBs better preserved ECM expressions.

Because cell–ECM interactions affect cell shape and cytoskeleton organization, the effect of cryopreservation on actin organization of the I-E and D-E cells was also evaluated (Fig. 5). Without cryopreservation, EB-derived cells displayed dominantly cortical actin and a small amount of actin fibers. After cryopreservation and thaw, the cell outgrowth from I-E group displayed similar actin pattern compared to the noncryopreserved cells (Fig. 5A). Consistently, the percentage of I-E cells with polymerized actin was similar (92%±4% vs. 98%±2%) for the cryopreserved and noncryopreserved cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, after cryopreservation, D-E cells showed disorganized actin and the percentage of cells with polymerized actin dramatically decreased from 81%±7% to 37%±21% compared with the noncryopreserved group. These results indicated that intact EBs better preserved actin organization.

Cell organization and cryopreservation regulated EB neural differentiation

The effects of cell organization and cryopreservation on neural differentiation of the replated EBs were evaluated. For the cells in D-E group, the thawed cells differentiated into β-tubulin III+ neurons with extensive neural network (Fig. 6A). More GFAP-positive cells in the cryopreserved group were also observed compared to the corresponding noncryopreserved group. Consistently, flow cytometry analysis indicated that the percentages of β-tubulin III+ cells (17%±5% vs. 43%±13%) and GFAP+ cells (39%±12% vs. 64%±2%) for the cryopreserved cells were significantly increased compared with the noncryopreserved cells (Fig. 6B, C). In the meanwhile, the expression of Musashi 1 was significantly decreased after cryopreservation (91%±4% vs. 56%±8%), while Nestin expression decreased slightly (53%±8% vs. 45%±1%).

For the I-E group, the cells displayed a dense amount of neurons positive for β-tubulin III around the aggregates after cryopreservation (Fig. 6A). Slight increase in GFAP+ cells was observed. The quantitative analysis indicated the significant increase of β-tubulin III+ cells (24%±1% vs. 37%±6%) after cryopreservation (Fig. 6B, C). The increase in GFAP+ cells (25%±15% vs. 46%±8%) was also observed, but the difference was not statistically significant. Musashi 1 expression was comparable with or without cryopreservation (91%±3% vs. 85%±5%), while Nestin expression decreased slightly after cryopreservation (61%±2% vs. 43%±9%). These data indicate that cryopreservation promoted neuronal differentiation of both intact and dissociated EBs, while the EB dissociation in combination with cryopreservation promoted glial differentiation.

Regulation of ROS expression and caspase activation

Because cryopreservation induces oxidative stress, the ROS and caspase expressions were evaluated for the cells in D-E and I-E groups. The cells preconditioned with MSC-CM was also evaluated due to the antioxidant effects of MSC-CM.24 MSC-CM and N-CM contained 1% B27 due to the 1:1 mixing of EB medium and MSC medium, compared to DMEM/F12 with 2% B27 (control). For the DMEM/F12 condition, the cells in I-E group showed lower ROS expression (34%±3% vs. 74%±4%) compared with the D-E cells (Fig. 7A, B). Preconditioning with MSC-CM reduced ROS expression from 74%±4% to 39%±10% for D-E cells and from 34%±3% to 24%±2% for I-E cells, indicating better antioxidant capability of I-E cells than D-E cells. To interrogate potential contribution of ROS expression to apoptosis, the level of caspase expression was determined (Fig. 7C, D). I-E cells showed significantly lower levels of caspase in all three medium conditions than D-E cells (17–23% vs. 29–51%). Preconditioning with MSC-CM reduced caspase expression compared with N-CM group, but the levels were comparable to the expression in DMEM/F12 group.

To investigate the potential benefit of using MSC-CM preconditioning to improve cell recovery, cell viability and expansion fold were evaluated after cryopreservation. Cell viability immediately upon thaw was similar in all three medium conditions for D-E or I-E cells (Fig. 8A). But the expansion fold was significantly increased (two-fold) in MSC-CM compared with N-CM for I-E cells, and it was comparable to that in DMEM/F12 group (Fig. 8B). While MSC-CM had protection effects, the impact of EB organization (intact vs. dissociated) on cell expansion fold was more pronounced as seen in Figure 8.

Discussion

EB cryo-banking enhances the capacity of basic research and cell therapy by providing a large quantity of cells at the intermediate stage over the course of differentiation, which can be used for process monitoring, sample storage, and follow-up differentiations.13,17 Various cryopreservation methods including slow-cooling and vitrification have been tested for aggregate-based stem cells.19,20,30,31 Slow-cooling method is more amendable for large-scale cell banking due to its simplicity.32–34 However, the impacts of microenvironment on the lineage commitment of cryopreserved EBs using slow-cooling method are not fully understood. This study revealed the influences of endogenous ECM secretion, actin cytoskeleton organization, and cellular redox state (indicated by ROS generation) in EBs on cell recovery and neural differentiation post-thaw.

The microenvironment of EBs regulated cell recovery

The preservation of intact EB microenvironment enhanced cell recovery due to the preservation of cell–cell contacts, endogenous ECM network, and organized distribution of actin cytoskeleton.35–37 The disrupted cell–cell contacts and the cell detachment from the surrounding ECM was reported to result in a specific type of apoptosis, known as “anoikis.”38 NPCs upon dissociation were prone to apoptosis through the activation of ROCKi,39 while abundant N-cadherin maintained in cell–cell contacts of intact aggregates was reported to enhance NPC attachment by acting as anchoring points for actin organization.40,41 The process of cryopreservation can result in actin disorganization and the disruption of cadherin and connexin,42–45 impacting stem cell proliferation and survival. However, simply adding ROCK inhibitor Y27632 in the dissociated EBs did not significantly improve the recovery (Supplementary Fig. S2). Instead, intact EBs preserved ECM expression and maintained proper F-actin organization due to the preservation of cellular organization.

Moreover, cryopreservation generates ROS due to the oxidative stress caused by hyperthermia.23,46 High concentration of ROS activated caspase expression and induced cell apoptosis during cryopreservation.27 In this study, intact EBs had lower ROS expression and less caspase activation compared to dissociated EBs, which may be attributed to the preserved ECM expression. The endogenous ECMs have been reported to mediate antioxidant effects and reduce the intracellular levels of ROS, improving stem cell survival and proliferation.47,48 The sugar components of the ECMs (e.g., glycosaminoglycans) also can exert cryo-protective effects (e.g., mimicking the protection effect of trehalose).17 In this study, intact EBs retained expressions of laminin and fibronectin, which may contribute to better cell survival.49 Therefore, the microenvironment of intact EBs may protect the cells from oxidative stress.

Diffusion limitation has been an issue for aggregate-based cryopreservation.23,50 The size of neurospheres and the PSC aggregates reported in previous studies were about 100–200 μm in diameter to allow the efficient diffusion of cryoprotectants and antioxidants. Our previous study has shown that ROS generation and caspase activation were elevated for large undifferentiated PSC aggregates (>300 μm).19,23 In this study, the size of EBs after 8-day culture was around 400 μm, which was inductive for ROS generation. The survival of large EBs could be due to the intrinsically high antioxidant capacities of neural lineages (e.g., expression of antioxidant enzymes: peroxide dismutase and catalase).51 The cellular redox state, a balance between the rates of production and the clearance of the free radicals, was shown to be better controlled in neural progenitors, which rendered the cells more resistant to oxidative stress.51

Secretome of MSCs has been shown to exert antiapoptotic and antioxidative effects on neural cells due to factors such as stanniocalcin-1 (STC-1),25 vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1).52,53 In this study, MSC-CM was shown to reduce the ROS expression and can be potentially used to improve EB recovery compared to the nonconditioned media. However, MSC-CM did not impact the cell viability immediately post-thaw but the recovery after 3 days. It was postulated that MSC-CM may protect the cells from the delayed-onset cell death and stimulate cell proliferation post-thaw.24,54

Cryopreservation and cell organization modulated neural differentiation

In this study, an increased neuronal differentiation (13–26%) indicated by β-tubulin III expression was observed upon thaw for both intact and dissociated EBs compared with noncryopreserved groups. Although the cryopreservation of spontaneously differentiated EBs has been evaluated, no quantification has been performed for lineage-specific differentiation.17,21 For undifferentiated human ESCs, cryopreservation has been reported to diminish Oct-4 expression and induce spontaneous differentiation,55 while the impact of cryopreservation on neural differentiation of EBs remains unknown. The increased neuronal differentiation observed in this study is thought to be due to cryopreservation-induced ROS generation. Besides the impact on cell survival, ROS is also reported to serve as a regulator of neural lineage commitment.56 For example, endogenous ROS was shown to regulate the proliferation and the expression of progenitor markers (e.g., Nestin and doublecortin) for adult NPCs.57,58 The induction of ROS at the stage of proliferation or formation of neurospheres was found to promote neuronal differentiation by activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) signaling pathways.56,57 Our results indicated that cryopreservation may slightly bias the lineage-specific differentiation of PSCs, which needs to be considered for the design of EB cryo-banking process.

Glial differentiation was also promoted after cryopreservation, especially for the dissociated EBs (by 25%), which may be attributed to both ROS generation and cell organization. When ROS were elevated during NPC differentiation, it has been reported that cell proliferation was decreased and glial differentiation (i.e., GFAP+ cells) was promoted at the expense of neuronal differentiation (i.e., β-tubulin III+ cells).59,60 From our results, the glial lineage differentiation was more pronounced in dissociated EBs than intact EBs after cryopreservation, which may be due to the differences in cellular organization of single cells versus multicellular aggregates. For example, the connexin disruption of neural progenitors has been shown to reduce neuronal differentiation but increase glial differentiation.61 Hence, cellular organization of EBs not only affected EB recovery, but also impacted differentiation potential postcryopreservation.

Cellular redox state reflected by ROS generation is capable of balancing between self-renewal and differentiation of progenitor cells.57,59 Several factors in this study contributed to the regulation of cellular redox state in EBs, including endogenous ECMs, cell organization/cytoskeleton, and the cryopreservation/thaw process. The interplay of these multiple factors impacted EB recovery and the neural lineage specification. While the results of this study indicated the importance of EB microenvironment in regulating cellular redox state, the exact mechanism of cryopreservation-induced neural differentiation of EBs and the impacts on mesoderm and endoderm differentiation still need to be further investigated.

Conclusion

The preservation of cellular microenvironment of EBs protected the cells from cryo-injuries and enhanced cell recovery compared with the dissociated cells, which may be due to the maintenance of proper cell–cell contacts and endogenous ECMs. In addition, the structural organization of EBs and the elevated ROS due to cryopreservation modulated neural and glial differentiation of EBs, which resulted in the increased neuron marker expression and the differential effect on astrocyte marker expression. The results indicated that modulating EB microenvironment prior to cryopreservation affected the differentiation potential, which needs to be considered during cryo-banking of EBs for their applications in drug discovery and regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Ruth Didier of FSU Department of Biomedical Sciences for her help in flow cytometry and confocal microscopy and Ms. Yijun Liu of Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering for providing conditioned medium of mesenchymal stem cells. This work is supported by FSU startup fund, FSU GAP award, and partially from the National Science Foundation (grant No.1342192). We also thank Dr. Teng Ma of Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering at FAMU-FSU College of Engineering for comments on the article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Yu D.X., Marchetto M.C., and Gage F.H.Therapeutic translation of iPSCs for treating neurological disease. Cell Stem Cell 12,678, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikoletopoulou V., and Tavernarakis N.Embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation as a tool in neurobiology. Biotechnol J 7,1156, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferron S., Mira H., Franco S., Cano-Jaimez M., Bellmunt E., Ramirez C., Farinas I., and Blasco M.A.Telomere shortening and chromosomal instability abrogates proliferation of adult but not embryonic neural stem cells. Development 131,4059, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daadi M.M., and Steinberg G.K.Manufacturing neurons from human embryonic stem cells: biological and regulatory aspects to develop a safe cellular product for stroke cell therapy. Regen Med 4,251, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibaoui Y., and Feki A.Human pluripotent stem cells: applications and challenges in neurological diseases. Front Physiol 3,267, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oki K., Tatarishvili J., Woods J., Koch P., Wattananit S., Mine Y., Monni E., Prietro D.T., Ahlenius H., Ladewig J., Brustle O., Lindvall O., and Kokaia Z.Human induced pluripotent stem cells form functional neurons and improve recovery after grafting in stroke-damaged brain. Stem Cells 30,1120, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popescu I.R., Nicaise C., Liu S., Bisch G., Knippenberg S., Daubie V., Bohl D., and Pochet R.Neural progenitors derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells survive and differentiate upon transplantation into a rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Stem Cells Transl Med 2,167, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grskovic M., Javaherian A., Strulovici B., and Daley G.Q.Induced pluripotent stem cells—opportunities for disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10,915, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancaster M.A., Renner M., Martin C.A., Wenzel D., Bicknell L.S., Hurles M.E., Homfray T., Penninger J.M., Jackson A.P., and Knoblich J.A.Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501,373, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano T., Ando S., Takata N., Kawada M., Muguruma K., Sekiguchi K., Saito K., Yonemura S., Eiraku M., and Sasai Y.Self-formation of optic cups and storable stratified neural retina from human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 10,771, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milosevic J., Storch A., and Schwarz J.Cryopreservation does not affect proliferation and multipotency of murine neural precursor cells. Stem Cells 23,681, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbasalizadeh S., and Baharvand H.Technological progress and challenges towards cGMP manufacturing of human pluripotent stem cells based therapeutic products for allogeneic and autologous cell therapies. Biotechnol Adv 31,1600, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stacey G.N., Crook J.M., Hei D., and Ludwig T.Banking human induced pluripotent stem cells: lessons learned from embryonic stem cells? Cell Stem Cell 13,385, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner D., Khaner H., Cohen M., Even-Ram S., Gil Y., Itsykson P., Turetsky T., Idelson M., Aizenman E., Ram R., Berman-Zaken Y., and Reubinoff B.Derivation, propagation and controlled differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in suspension. Nat Biotechnol 28,361, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Gautam A., Yang J., Qiu L., Melkoumian Z., Weber J., Telukuntla L., Srivastava R., Whiteley E.M., and Brandenberger R.Differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells from human embryonic stem cells on vitronectin-derived synthetic peptide acrylate surface. Stem Cells Dev 22,1497, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulting G.L., Kiskinis E., Croft G.F., Amoroso M.W., Oakley D.H., Wainger B.J., Williams D.J., Kahler D.J., Yamaki M., Davidow L., Rodolfa C.T., Dimos J.T., Mikkilineni S., MacDermott A.B., Woolf C.J., Henderson C.E., Wichterle H., and Eggan K.A functionally characterized test set of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 29,279, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S., Szurek E.A., Rzucidlo J.S., Liour S.S., and Eroglu A.Cryobanking of embryoid bodies to facilitate basic research and cell-based therapies. Rejuvenation Res 14,641, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Illes S., Theiss S., Hartung H.P., Siebler M., and Dihne M.Niche-dependent development of functional neuronal networks from embryonic stem cell-derived neural populations. BMC Neurosci 10,93, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma X.H., Shi Y., Hou Y., Liu Y., Zhang L., Fan W.X., Ge D., Liu T.Q., and Cui Z.F.Slow-freezing cryopreservation of neural stem cell spheres with different diameters. Cryobiology 60,184, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemati S., Hatami M., Kiani S., Hemmesi K., Gourabi H., Masoudi N., Alaei S., and Baharvand H.Long-term self-renewable feeder-free human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitors. Stem Cells Dev 20,503, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichikawa H., No H., Takei S., Takashimizu I., Yue F., Cui L., Ogiwara N., Johkura K., Nishimoto Y., and Sasaki K.Cryopreservation of mouse embryoid bodies. Cryobiology 54,290, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malpique R., Osorio L.M., Ferreira D.S., Ehrhart F., Brito C., Zimmermann H., and Alves P.M.Alginate encapsulation as a novel strategy for the cryopreservation of neurospheres. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16,965, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sart S., Ma T., and Li Y.Cryopreservation of pluripotent stem cell aggregates in defined protein-free formulation. Biotechnol Prog 29,143, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sart S., Liu Y., Ma T., and Li Y.Microenvironment regulation of pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitor aggregates by human mesenchymal stem cell secretome. Tissue Eng Part A 2014. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teixeira F.G., Carvalho M.M., Sousa N., and Salgado A.J.Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: a new paradigm for central nervous system regeneration? Cell Mol Life Sci 70,3871, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simandi Z., Balint B.L., Poliska S., Ruhl R., and Nagy L.Activation of retinoic acid receptor signaling coordinates lineage commitment of spontaneously differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells in embryoid bodies. FEBS Lett 584,3123, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alenzi F.Q., Lotfy M., and Wyse R.Swords of cell death: caspase activation and regulation. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 11,271, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sart S., Ma T., and Li Y.Extracellular matrices decellularized from embryonic stem cells maintained their structure and signaling specificity. Tissue Eng Part A 20,54, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sart S., Errachid A., Schneider Y.J., and Agathos S.N.Modulation of mesenchymal stem cell actin organization on conventional microcarriers for proliferation and differentiation in stirred bioreactors. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 7,537, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan F.C., Lee K.H., Gouk S.S., Magalhaes R., Poonepalli A., Hande M.P., Dawe G.S., and Kuleshova L.L.Optimization of cryopreservation of stem cells cultured as neurospheres: comparison between vitrification, slow-cooling and rapid cooling freezing protocols. Cryo Letters 28,445, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hancock C.R., Wetherington J.P., Lambert N.A., and Condie B.G.Neuronal differentiation of cryopreserved neural progenitor cells derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 271,418, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coopman K.Large-scale compatible methods for the preservation of human embryonic stem cells: current perspectives. Biotechnol Prog 27,1511, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt C.J.Cryopreservation of human stem cells for clinical application: a review. Transfus Med Hemother 38,107, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., and Ma T.Bioprocessing of cryopreservation for large scale banking of human pluripotent stem cells. Biores Open Access 1,205, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong R.C., Dottori M., Koh K.L., Nguyen L.T., Pera M.F., and Pebay A.Gap junctions modulate apoptosis and colony growth of human embryonic stem cells maintained in a serum-free system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 344,181, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samarasinghe R.A., Di Maio R., Volonte D., Galbiati F., Lewis M., Romero G., and DeFranco D.B.Nongenomic glucocorticoid receptor action regulates gap junction intercellular communication and neural progenitor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108,16657, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noles S.R., and Chenn A.Cadherin inhibition of beta-catenin signaling regulates the proliferation and differentiation of neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 35,549, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grossmann J.Molecular mechanisms of “detachment-induced apoptosis—Anoikis”. Apoptosis 7,247, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyanagi M., Takahashi J., Arakawa Y., Doi D., Fukuda H., Hayashi H., Narumiya S., and Hashimoto N.Inhibition of the Rho/ROCK pathway reduces apoptosis during transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursors. J Neurosci Res 86,270, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazou D., Blain E.J., and Coakley W.T.NCAM and PSA-NCAM dependent membrane spreading and F-actin reorganization in suspended adhering neural cells. Mol Membr Biol 25,102, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim M.Y., Kaduwal S., Yang D.H., and Choi K.Y.Bone morphogenetic protein 4 stimulates attachment of neurospheres and astrogenesis of neural stem cells in neurospheres via phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-mediated upregulation of N-cadherin. Neuroscience 170,8, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichikawa H., Yoshie S., Shirasawa S., Yokoyama T., Yue F., Tomotsune D., and Sasaki K.Freeze-thawing single human embryonic stem cells induce e-cadherin and actin filament network disruption via g13 signaling. Cryo Letters 32,516, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magalhaes R., Nugraha B., Pervaiz S., Yu H., and Kuleshova L.L.Influence of cell culture configuration on the post-cryopreservation viability of primary rat hepatocytes. Biomaterials 33,829, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ragoonanan V., Hubel A., and Aksan A.Response of the cell membrane-cytoskeleton complex to osmotic and freeze/thaw stresses. Cryobiology 61,335, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teo K.Y., DeHoyos T.O., Dutton J.C., Grinnell F., and Han B.Effects of freezing-induced cell-fluid-matrix interactions on the cells and extracellular matrix of engineered tissues. Biomaterials 32,5380, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu X., Cowley S., Flaim C.J., James W., Seymour L., and Cui Z.The roles of apoptotic pathways in the low recovery rate after cryopreservation of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Biotechnol Prog 26,827, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai Y., Sun Y., Skinner C.M., Son E.L., Lu Z., Tuan R.S., Jilka R.L., Ling J., and Chen X.D.Reconstitution of marrow-derived extracellular matrix ex vivo: a robust culture system for expanding large-scale highly functional human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 19,1095, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei M., He F., and Kish V.L.Expansion on extracellular matrix deposited by human bone marrow stromal cells facilitates stem cell proliferation and tissue-specific lineage potential. Tissue Eng Part A 17,3067, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma W., Tavakoli T., Derby E., Serebryakova Y., Rao M.S., and Mattson M.P.Cell-extracellular matrix interactions regulate neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. BMC Dev Biol 8,90, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Winkle A.P., Gates I.D., and Kallos M.S.Mass transfer limitations in embryoid bodies during human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cells Tissues Organs 196,34, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madhavan L., Ourednik V., and Ourednik J.Increased “vigilance” of antioxidant mechanisms in neural stem cells potentiates their capability to resist oxidative stress. Stem Cells 24,2110, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang F., Yasuhara T., Shingo T., Kameda M., Tajiri N., Yuan W.J., Kondo A., Kadota T., Baba T., Tayra J.T., Kikuchi Y., Miyoshi Y., and Date I.Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells exerts therapeutic effects on parkinsonian model of rats: focusing on neuroprotective effects of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha. BMC Neurosci 11,52, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee R.H., Oh J.Y., Choi H., and Bazhanov N.Therapeutic factors secreted by mesenchymal stromal cells and tissue repair. J Cell Biochem 112,3073, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baust J.M., Vogel M.J., Van Buskirk R., and Baust J.G.A molecular basis of cryopreservation failure and its modulation to improve cell survival. Cell Transplant 10,561, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katkov II, Kim M.S., Bajpai R., Altman Y.S., Mercola M., Loring J.F., Terskikh A.V., Snyder E.Y., and Levine F.Cryopreservation by slow cooling with DMSO diminished production of Oct-4 pluripotency marker in human embryonic stem cells. Cryobiology 53,194, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kennedy K.A., Sandiford S.D., Skerjanc I.S., and Li S.S.Reactive oxygen species and the neuronal fate. Cell Mol Life Sci 69,215, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Le Belle J.E., Orozco N.M., Paucar A.A., Saxe J.P., Mottahedeh J., Pyle A.D., Wu H., and Kornblum H.I.Proliferative neural stem cells have high endogenous ROS levels that regulate self-renewal and neurogenesis in a PI3K/Akt-dependant manner. Cell Stem Cell 8,59, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsatmali M., Walcott E.C., Makarenkova H., and Crossin K.L.Reactive oxygen species modulate the differentiation of neurons in clonal cortical cultures. Mol Cell Neurosci 33,345, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prozorovski T., Schulze-Topphoff U., Glumm R., Baumgart J., Schroter F., Ninnemann O., Siegert E., Bendix I., Brustle O., Nitsch R., Zipp F., and Aktas O.Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol 10,385, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santos D.M., Santos M.M., Moreira R., Sola S., and Rodrigues C.M.Synthetic condensed 1,4-naphthoquinone derivative shifts neural stem cell differentiation by regulating redox state. Mol Neurobiol 47,313, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hartfield E.M., Rinaldi F., Glover C.P., Wong L.F., Caldwell M.A., and Uney J.B.Connexin 36 expression regulates neuronal differentiation from neural progenitor cells. PLoS One 6,e14746, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.