Abstract

The genomics and proteomics revolutions have been enormously successful in providing crucial “parts lists” for biological systems. Yet, formidable challenges exist in generating complete descriptions of how the parts function and assemble into macromolecular complexes and whole-cell assemblies. Bacterial biofilms are complex multicellular bacterial communities protected by a slime-like extracellular matrix that confers protection to environmental stress and enhances resistance to antibiotics and host defenses. As a non-crystalline, insoluble, heterogeneous assembly, the biofilm extracellular matrix poses a challenge to compositional analysis by conventional methods. In this Perspective, bottom-up and top-down solid-state NMR approaches are described for defining chemical composition in complex macrosystems. The “sum-of-theparts” bottom-up approach was introduced to examine the amyloid-integrated biofilms formed by E. coli and permitted the first determination of the composition of the intact extracellular matrix from a bacterial biofilm. An alternative top-down approach was developed to define composition in V. cholerae biofilms and relied on an extensive panel of NMR measurements to tease out specific carbon pools from a single sample of the intact extracellular matrix. These two approaches are widely applicable to other heterogeneous assemblies. For bacterial biofilms, quantitative parameters of matrix composition are needed to understand how biofilms are assembled, to improve the development of biofilm inhibitors, and to dissect inhibitor modes of action. Solid-state NMR approaches will also be invaluable in obtaining parameters of matrix architecture.

Keywords: bacterial biofilms, extracellular matrix, solid-state NMR, CPMAS, REDOR, E. coli, V. cholerae

Introduction

“When once we know what the molecular architecture of the proteins and other large molecules that carry the physiological activity of the human body is, what the relation of the structure of these molecules is to that of the vectors of disease, and of the drugs, such as penicillin and the sulfa drugs, that serve effectively in protecting us against infectious disease, what changes in molecular architecture are associated with the degenerative diseases - then we can attack the problem of the degenerative diseases in an effective way, using the methods of attack that are suggested by this knowledge.”

Linus Pauling. From the lecture “Molecular Architecture and the Processes of Life,” Nottingham, England, 1948.

It was only three years before Pauling delivered the lecture from which the above text is quoted when the first NMR results were reported by Bloch et al. studying a liquid (H20)[1] and Purcell et al. examining a solid (paraffin)[2]. Bloch and Purcell went on to share the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952. The first protein crystal structures, of myoglobin[3] and hemoglobin[4], were reported in 1960. Throughout the subsequent fifty years, science made revolutionary strides to reveal the molecular architecture of life’s most fundamental building blocks and machines. New details, new structures, and new discoveries continue to emerge and expand our understanding of life systems. Indeed, the genomics and proteomics revolutions have been enormously successful in generating full genome sequences for an increasing number of organisms and in predicting and determining the structures of a steadily increasing number of proteins. In essence, these data provide crucial “parts lists” for biological systems. Yet, formidable challenges exist in generating complete descriptions of how the parts function and assemble into macromolecular complexes and whole-cell assemblies. Through old and new and emerging cutting-edge technologies across disciplines, experimental and computational experiments are rapidly being developed and implemented in order to address such outstanding problems that will improve our understanding of biological assembly processes and function. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy has proven to be a powerful ally in generating more complete descriptions of macromolecular assemblies. Indeed, solid-state NMR has a rich history as an analytical tool to study the composition, structure, dynamics, and function of solid materials, ranging from coal and earth materials, industrial polymers and catalysts to biomaterials including spider silk, insect exoskeletons, amyloids, membrane proteins, cell walls, whole cells and intact tissues.

Bacterial biofilms are complex multicellular bacterial communities protected by a slime-like extracellular matrix that confers protection to environmental stress such as desiccation and shear flow and enhances bacterial resistance to antibiotics and host defenses[5–8]. The determination of extracellular matrix composition and architecture is crucial to understanding biofilm function and to developing strategies to inhibit matrix assembly and biofilm formation[9]. Genetic and molecular assays together with high-resolution microscopy have provided crucial information regarding factors that help to regulate biofilm formation and molecular factors such as specific proteins and polysaccharides that participate in matrix production[10]. Metabolomic NMR methods have also provided insights to survey and compare the changes in cellular signals and components associated with the cellular transition to the biofilm lifestyle[11], and elegant imaging mass spectrometry approaches have been employed to locate the presence of specific matrix components surrounding cells in the context of intact biofilms[12, 13]. Yet, these various approaches are not well suited to providing a total accounting of matrix composition and outstanding questions remain regarding the overall balance of protein vs polysaccharides vs other components in biofilms formed by diverse microorganisms[14]. The approximation of protein and polysaccharide concentrations, for example, have relied on protocols that attempt to solubilize matrix material and quantify the parts, either through soluble-based assays in the case of proteins or through selective precipitation protocols using various organic solvents to attempt to precipitate polysaccharides separately from other biofilm parts[10, 15]. However, many biofilms are recalcitrant to complete dissolution and quantification in these assays and solvent based extractions and precipitations often contain additional non-targeted components that contribute to the sample mass. These considerations compromise estimates of protein and polysaccharide composition. We have found, for example, that a standard BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay can severely underestimate protein content in ECM material. As one of several available protein assays, the BCA assay relies on the ability of proteins to reduce Cu2+ ions with colorimetric detection of Cu1+ by bicinchoninic acid, forming a purple colored product. The success of this assay can be compromised by the inaccessibility of protein peptide bonds within a dense matrix with extensive interactions with other components or due to competitive complexation of Cu2+ by other components in a complex sample. Harsh degradative methods can also lead to undesired perturbations of the material. Bacterial biofilms and extracellular matrix material have, on the other hand, been examined extensively by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to generally profile the types of chemical functionalities present in intact samples and particularly to permit comparisons across samples, assigning spectral signatures to carbonyls, peptide bonds, aromatics and aliphatics, for example, but have not permitted a complete accounting of biofilm composition[16]. A solid-state NMR study of the extracted ECM from biofilms growing on acid mine drainage also monitored the change in polysaccharide chemical shifts between two samples to qualitatively compare two biofilms and avoided the degradative measures associated with solution-based assays[17].

We recently reported the first determination of the molecular composition of the intact extracellular matrix of a bacterial biofilm[18]. This review will focus on the advances we have made in using solid-state NMR with complementary microscopy and biochemical techniques to define and characterize the composition of the extracellular matrix of bacterial biofilms, describing two different NMR approaches that are widely applicable to other organisms and macromolecular systems. In the case of E. coli, we implemented a “sum-of-the-parts” bottom-up approach[18] and in the case of V. cholerae we developed a top-down NMR approach[19]. In both methods, protocols were optimized to ensure non-perturbative preparation of matrix material from each organism and samples were examined extensively by biochemical characterization and microscopy. The integrated approach is crucial to defining the nature of the material being studied, ensuring that that most appropriate samples are being examined by NMR, and ultimately to ensuring the biological relevance of the NMR discoveries that drive our evolving understanding of bacterial biofilm composition, structure, and function.

Extracellular Matrix Composition of Curli-integrated E. coli Agar Biofilms: A Bottom-Up NMR Approach

Curli-integrated biofilm formation

The author’s interest in E. coli biofilms stemmed from her fascination with E. coli’s production of functional amyloid fibers termed curli and her discovery of small-molecule inhibitors that interfered with curli assembly in vivo and in vitro and prevented biofilm formation[20]. This fascination extends to questions surrounding the assembly of these fibers, how they mediate adhesion and contribute to the formation and stability of biofilms, and their potential contribution to the pathogenesis of uropathogenic E. coli during urinary tract infection[21, 22]. Furthermore, the general production of bacterial amyloid fibers by microbes in the human GI tract, bladder, or other niche could have implications for providing possible amyloid seeds that could influence amyloid assembly processes of human proteins associated with amyloid-related diseases.

Curli were first identified as adhesive fimbriae in 1989 by Normark and coworkers[23] and later identified as being amyloid fibers in 2002 by Chapman, Hultgren, and coworkers[24]. Even before their identification as amyloid, curli were well-studied for their contributions to biofilm formation in E. coli and Salmonella species, particularly for agar-grown biofilms[25, 26]. Cegelski and coworkers also identified curli as being required for biofilm formation at the airliquid interface (biofilms termed “pellicles”) [20] and have more recently examined the mechanical properties and molecular determinants associated with bacterial pellicles[27–30]. Cellulose is another major component that has been extensively studied for its role in biofilm formation in E. coli and Salmonella [26, 31], yet determinations of the amounts of curli, cellulose, and possibly other components in the biofilm were not available prior to our work described below.

Matrix isolation surprise and considerations

In implementing and optimizing protocols to isolate extracellular matrix material from biofilms, which include the cells plus the matrix material, we discovered that we could isolate mechanically robust supramolecular structures that surround E. coli like cocoons or baskets in amyloid-integrated bacterial biofilms[18] (Figure 1). These baskets are able to maintain their shape upon separation from bacteria through the shear forces exerted during use of a tissue homogenizer. The simple homogenization is gentle enough to not lyse E. coli cells and is sufficient to remove much of the matrix material surrounding E. coli. One can also perform such matrix extractions on the smaller scale, using 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and vortexing, and observe the intact basket-like structures (Figure 1). In addition to the basket-like structures, one also observes similar matrix material without the definitive shape of baskets that could have been matrix material connecting cells to one another and from baskets that were sheared apart, losing their three-dimensional shape. In preparing samples for NMR analysis, we observed that some flagella were present in the preparations. This was detected by electron microscopy and annotated by protein gel electrophoresis and mass spec protein identification[18]. Protein gels showed the major flagellar protein, FliC, as the only major protein other than the curli subunit, CsgA. Flagella are not required for E. coli biofilm formation on agar and do not contribute to the insoluble structural matrix material as evidenced by electron microscopy, so flagella were removed through SDS treatment to prepare samples for the primary NMR analysis.

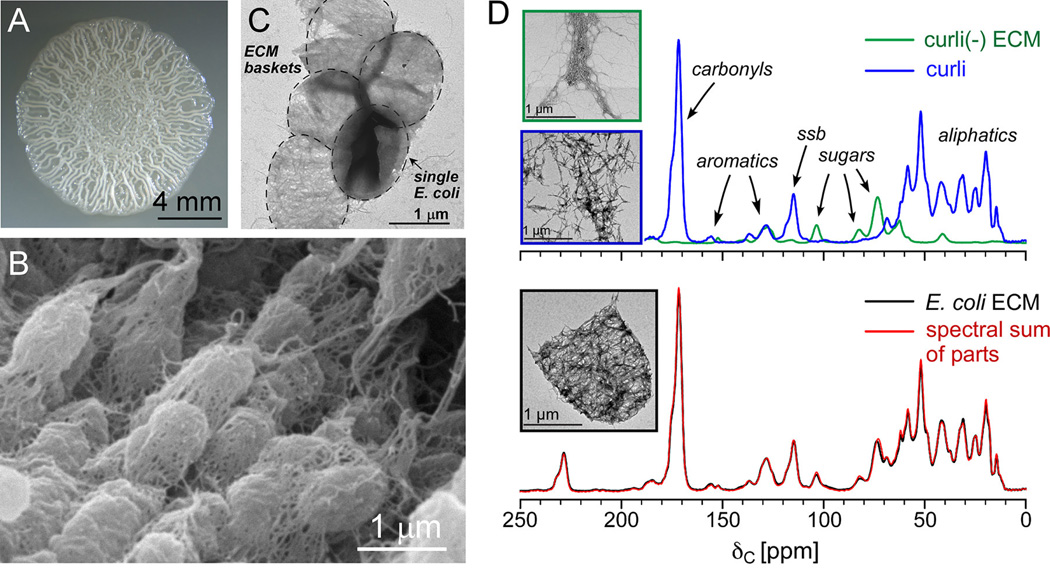

Figure 1. The bottom-up approach: E. coli biofilm phenotypes and ECM composition by solid-state NMR.

(A) The hallmark wrinkled colony morphology associated with biofilm formation of E. coli growing on YESCA nutrient agar. (B) Scanning electron micrograph on biofilms formed by the same uropathogenic E. coli strain, UTI89, as in panel A. (C) Transmission electron micrograph of a collection of ECM baskets following disruption of the biofilm with the tissue homogenizer, prior to low-speed centrifugation to remove intact cells (one bacterium present in TEM image). (D) The spectral sum of the UTI89ΔcsgA extracellular material and purified curli (top) completely recapitulates the 13C CPMAS spectrum of the intact UTI89 ECM (bottom), each associated with transmission electron micrographs associated with the samples. MAS was performed at 7143 Hz, and 32,768 scans were obtained for each spectrum. This figure is adapted from reference 18.

Sum-of-the-parts

Together with EM and biochemical analyses, we provided a complete “sum-of-the-parts” accounting of the insoluble matrix using solid-state NMR[18]. In this bottom-up approach, we obtained 13C CPMAS spectra of: (i) purified curli; (ii) the curli-free ECM produced by the curli mutant strain UTI89ΔcsgA; and (iii) the complete extracellular matrix (ECM). These spectra indicated that the biofilm matrix formed by curli-producing bacteria has two major components, curli and cellulose, each in a quantifiable amount. The curli-only spectra were obtained from native curli prepared from the strain MC4100 that only produces curli at the cell surface. Curli were obtained using our optimized protocol to isolate curli fibers through shear homogenization, avoiding cell lysis, with subsequent SDS washing and centrifugation, tracked by protein gel and western blot characterization. Protein gel analysis was performed with and without formic acid treatment, as is typical for amyloids, where formic acid treatment is required to disassemble curli for migrating through a polyacrylamide gel. The one-dimensional curli natural-abundance 13C NMR spectrum naturally contained contributions from all of the CsgA residues, including a notable downfield shoulder in the carbonyl peak that is consistent with the high propensity of Gln and Asn residues, with their carbonyl-containing sidechains, in the CsgA subunit[18]. The cellulose material was isolated from the biofilm-forming strain, UTI89, lacking the csgA gene: UTI89ΔcsgA. This material was certain to lack curli, but would contain cellulose and possibly other components. As mentioned in the previous section, the material contained flagella prior to SDS washing, but not as an intimate part of the insoluble network and matrix and is dispensable for UTI89 biofilm formation on agar. By NMR, the SDS-washed cellulose material produced by UTI89ΔcsgA appeared to be a modified form of a cellulose, where CPMAS and Rotational-Echo Double-Resonance (REDOR)[32] NMR spectra suggested the presence of an aminoethyl modification to the polysaccharide. There were no other protein or unrelated chemical shifts associated with this sample, which together with the protein characterization, indicated that that overall bottom-up analysis would be simpler than we anticipated. We discovered that a spectral sum of the two samples (pure curli and the extracellular material from the curli mutant, UTI89ΔcsgA) was able to completely recapitulate the CPMAS spectrum of the wild-type UTI89 ECM (Figure 1). Thus, from the spectral scaling we determined that the ECM was composed of only two major components by mass: curli amyloid fibers (85%) and a modified form of cellulose (15%). An additional sample that contained a physical mixture of the two major parts combined in the 6:1 ratio in one sample rotor additionally confirmed the compositional determination[18]. This was the first quantification of the components of the intact ECM from a bacterial biofilm.

In addition, we have reported NMR spectra for intact bacterial biofilms, including cells plus the ECM, that have been valuable for comparing the total carbon pools of biofilms formed under different conditions[9, 30], although very selective assignments are more challenging in whole-biofilm samples. What should be emphasized here is that the bottom-up approach introduced in our E. coli ECM study was made possible by having samples corresponding to separate biofilm parts. By collecting the 13C NMR spectra of known biofilm parts, one can determine how well they account for the total compositional profile from the intact biofilm matrix with all the parts present. This bottom-up approach should also be applicable to other macromolecular and whole-cell assemblies.

Extracellular Matrix Composition of Vibrio cholerae Agar Biofilms: A Top-Down NMR Approach

A more complex matrix

The approach employed above for E. coli is appropriate when separate samples of major biofilm parts are available or can be approximated by available NMR spectra of related components. In our second major study of the composition of the bacterial extracellular matrix, we examined biofilms formed by Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, noting that we worked with the cholera toxin mutant that is unable to cause disease. Several proteins, including Bap1, RbmA, and RbmC, as well as the complex Vibrio exopolysaccharide, also known as VPS, have been identified as being present in the extracellular matrix[33–36], but with no estimation of the extent to which each is present in the material. Outer membrane vesicles comprised of lipopolysaccharides have also been detected in V. cholerae biofilms[37–39]. Together these provide a starting “parts list” for the V. cholerae ECM.

The top-down approach

A similar approach to that described above could be taken and would require optimization of the separate polysaccharide and single protein expression and production systems to generate sufficient quantities of the candidate matrix parts for NMR analysis. However, we took the opportunity to develop a new top-down methodology to extract quantitative atomic-level parameters from this ECM system[19], appreciating it would be much more complex than the E. coli matrix composition described above. This approach can be applied to the many biofilms for which there is much less information available regarding potential biofilm parts, with only the complex matrix material to dissect biochemically and spectroscopically.

In our top-down approach, carbon and nitrogen NMR spectra of a uniformly 15N-labeled V. cholerae extracellular matrix sample provide an overall compositional profiling, while recoupling measurements, specifically 13C{15N}, 13C{31P}, and 15N{31P} REDOR measurements, allowed for enhanced annotation and quantification of the carbon and nitrogen pools. The ECM sample in this case was prepared from V. cholerae grown on a minimal agar medium. ECM was extracted by simple overnight rocking in 50-mL conical tubes, which for V. cholerae was sufficient to remove ECM from the cells. After cell removal by low-speed centrifugation, the ECM material in the supernatant was dialyzed against water, frozen, and lyophilized.

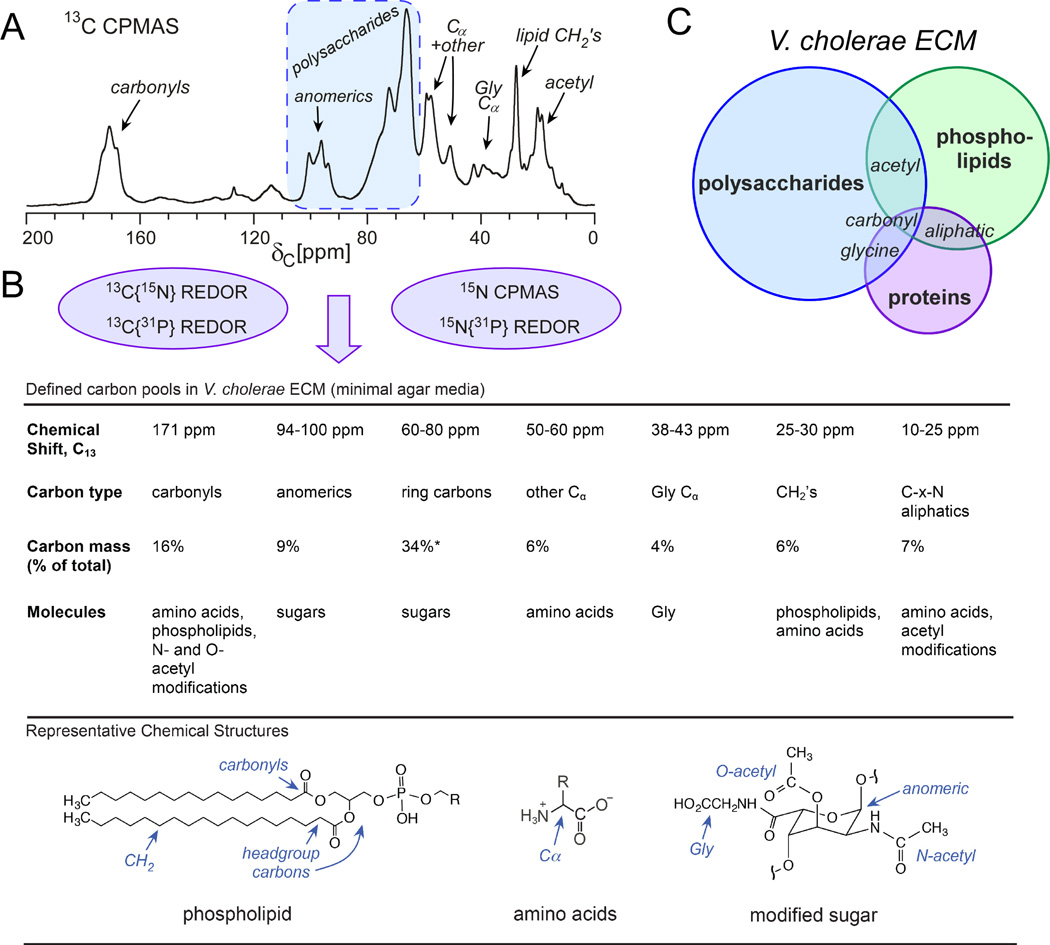

First-level accounting of general carbon types from CPMAS

The first inspection of the 13C CPMAS spectrum immediately revealed that the V. cholerae ECM was polysaccharide rich with significant carbon intensity in the 60–100 ppm range (Figure 2). Carbon chemical shifts were also observed that were consistent with proteins (carbonyl, 171 ppm; α-carbons, 51–58 ppm; other aliphatics 10–40 ppm), glycine (α-carbons, 38–43 ppm), acetyl modifications (20–22 ppm), lipids (20, 28, and 171 ppm), and possibly DNA. To use the CPMAS peak areas quantitatively, one must account for the possible influence of differences in cross polarization of different spin types. Thus, CPMAS was performed as a function of CP time and CP buildup curves were provided for each distinguishable peak in the spectrum, where extrapolations to time zero from data at long CP times provide normalized intensities. Except for the sharp lipid-like peak at 28 ppm, the CP behavior of the other carbons was similar with little or no change to the relative integrated carbon contributions, suggesting that they experience a similar overall proton spin system. In our experience, many of our intact whole-cell and cell-wall samples behave this way, for lyophilized solids with NMR measurements performed on 200–500MHz spectrometers with modest spinning speeds (under 8 kHz).

Figure 2. The top-down approach: V. cholerae ECM composition by solid-state NMR.

(A) The 13C CPMAS spectrum indicates that the ECM is polysaccharide rich and provides a snapshot of all of the general carbon types in the ECM. (B) REDOR experiments allowed for spectral editing and quantitation of more specific carbon pools as summarized in the table accompanied by illustrated molecular components and their carbon contributions. (C) Graphical summary of approximate V. cholerae ECM compositional pools. This figure is adapted from reference 19.

The anomeric and complementary sugar-ring carbons have unique carbon chemical shifts and provided the start of the carbon accounting. 8.5% of all the carbon intensity in the spectrum was attributed to the anomerics while 34% was due to the other sugar ring carbons. It was reassuring to obtain this experimental 4:1 integrated ratio for non-anomeric sugar carbons to anomeric carbons as expected for a sugar ring system. Thus, we knew that 43% of the total carbons arise from collective sugar ring carbons. We anticipated that the overall polysaccharide carbon contribution would be even larger as studies on isolated polysaccharide parts have revealed that V. cholerae polysaccharides are highly modified.

Detailed carbon accounting of the V. cholerae ECM using REDOR as a spectroscopic ruler and filter to identify and quantify one-bond C-N pairs and longer range C-P couplings

Given the redundancy among other chemical shifts, 13C{15N}REDOR permitted further specification. Carbons were present at natural abundance and we employed 13C{15N}REDOR to select for onebond C-N couplings. Although REDOR is typically recognized for its ability to obtain longrange distance information through the accurate determination of heteronuclear dipolar couplings, we often use REDOR as a spectroscopic filter as described here to dissect spectra of complex systems. One-bond 13C{15N}REDOR (REDOR evolution time of 1.68 ms) provided an upper limit on the percent of carbons that could be assigned to alpha carbons in contrast to other carbons that could contribute to peak intensity between 40–60 ppm that are not directly bonded to a nitrogen. We determined that the upper limit on alpha carbons (for all amino acids except glycine) was 6%. Accompanying this was the estimate of glycine alpha carbons as contributing to 4% of the carbon pool, which would be surprising given that glycine is one of twenty amino acids. Although glycine can be more prevalent than many amino acids in proteins, one wouldn’t expect this contribution to be more than about 10% of the alpha carbons, or about 0.6% of the total carbon pool. The structure of an isolated soluble polysaccharide unit has been reported, however, and has a complex structure, with N-acetyl, O-acetyl, and glycine modifications on a single sugar ring. Thus, the results indicated that many of the sugars may be accompanied by a glycine modification. Given that approximately 9% of the carbons are anomerics and about 3% of the glycine carbons are likely involved in modifications, up to one-third of the polysaccharides may be modified with glycine. The carbonyl intensity also indicated that carbonyls contribute to 16% of the carbon mass, where only 75% of those were directly bonded to a nitrogen as determined by REDOR. Thus, a maximum of 12% of the carbon was assigned to peptides and sugar N-acetyl modifications, providing an additional parameter in accounting for the ECM carbon. About 10% of the ECM carbonyls would be expected to be associated with their respective alpha carbons (6% non-Gly and 4% Gly described above), leaving about 2% for carbonyls with an adjacent nitrogen in polysaccharide modifications, such as with N-acetyl groups. The remaining 4% of carbonyls not directly bonded to 15N could arise from lipid headgroups, Asp and Glu sidechains, and glycine modifications on polysaccharides. The presence of lipids was also confirmed by 13C{31P}REDOR performed at a longer evolution time of 8.95 ms to monitor the carbonyls and nearby carbons proximate to 31P in lipid headgroup regions, where the REDOR difference spectrum was comparable to 13C{31P} REDOR spectra of a pure lipid sample. The remaining spectral contributions in the aliphatic region were also consistent with the defined contributions described above and together provided a total accounting of the types of carbons and estimation of the carbon content in polysaccharide, lipid, and protein pools (Figure 2).

Given the several candidates for possible proteins in the ECM, we did not uniquely quantify the amount of distinct proteins, but rather accounted for the types of molecular carbon present in the ECM, a valuable approach in such a complex ECM--perhaps one of the most complex we will encounter. Protein gels were also obtained of the ECM material[19] and standard mass mapping with mass spectrometry or N-terminal sequencing can identify those proteins and help to assess specific protein contributions that can be compared across samples when the proteins are soluble or can be solubilized well and run into a protein gel. Future comparisons with reference samples of individual polysaccharide, lipid, and proteins contributions can also be made in the spirit of the E. coli approach described above. Yet, while important genetic and molecular determinants have been identified for V. cholerae biofilm formation, our solid-state NMR approach provided crucial parameters to place the key types of molecular players into the greater compositional context of the intact V. cholerae ECM.

Conclusions and future avenues

We have developed new approaches that help to transform vague biofilm descriptors from terms like “glue” and “slime” into quantitative parameters of chemical and molecular composition. In our work with amyloid-integrated E. coli biofilms, we provided the first quantitative determination of the composition of the intact extracellular matrix of a bacterial biofilm. In this “sum-of-the-parts” bottom-up approach, 13C NMR spectra of separate matrix components were able to completely recapitulate the spectrum of the intact ECM. In our work with the more complex Vibrio cholerae biofilms, we developed an alternative top-down NMR approach that only required the intact ECM material and did not rely on samples corresponding to isolated matrix components. With these two examples so far, we find that bacteria can employ very different matrix-assembly strategies to build an ECM that provides protection to the bacterial community. In the case of E. coli biofilms grown on YESCA agar, the ECM is protein-rich and in the case of V. cholerae, the compositional balance of the ECM is more polysaccharide-rich, with lipids and proteins helping to contribute to an overall more complex ECM. Most biofilm studies and reviews have emphasized the prominent role that polysaccharides play in biofilm communities and our determination that the E. coli ECM contained much more protein than polysaccharide was a surprise. It may be that amyloid fibers are unique among proteins for their ability to contribute to aggregation and structural matrix assembly. We have suggested that the presence of hydrophobic proteins, in general, may be necessary for biofilm formation at air-liquid interfaces[29] and the same may also apply to biofilms on solid surfaces such as agar and plastic. Future work examining other amyloid-integrated biofilms and non-amyloid-associated biofilms are needed to explore these possibilities.

To summarize the immediate and evolving impact of our analytical developments in characterizing matrix composition, the solid-state NMR approaches we have introduced for compositional analysis of biofilm matrices are not subject to sampling bias or destruction of matrix material that is required of most analyses employed to characterize the composition of ECM material. One must fully describe and characterize the type of sample being investigated and how the ECM was prepared, with characterization by at least microscopy and protein gel analysis, and different isolation protocols may be suited to different biofilms. The NMR spectra then report on the total accounting of NMR-active nuclei in a given sample. We have examined 13C, 15N, and 31P pools in our biofilm work. Both bottom-up and top-down approaches involve a panel of one-dimensional NMR experiments that can be employed on any spectrometer equipped to perform solid-state NMR measurements, where the REDOR measurements require a three-channel probe and spectrometer.

Future avenues for the E. coli biofilms described here involve the integration of higher resolution microscopy to improve our understanding of the spatial arrangements of matrix parts and polymers in the ECM. Indeed, super-resolution imaging of V. cholerae biofilms was important for visualizing and locating specific proteins within the intact biofilm and proposing distinct roles regarding cell-surface adhesion and cell-cell adhesion, for example[40]. Similar visualization will be invaluable in understanding the spatial arrangements of curli and cellulose in the amyloid-integrated E. coli biofilms. We are also working to measure the atomic-level proximities between matrix components in the E. coli ECM by NMR. Parameters of biofilm architecture will further refine our developing description of a biofilm and its corresponding ECM as an organized assembly of polymeric macromolecules, connecting composition, architecture, and function. Towards these goals of detailing ECM architecture, there are exciting opportunities to recruit creative NMR detection schemes, coupled to traditional or new biosynthetic labeling strategies to build from the foundation provided by the compositional determinations described in this perspective. Determinations of matrix architecture will also be invaluable in helping to determine the modes of action of biofilm inhibitors, particularly ones that may prevent proper matrix assembly.

Highlights.

Solid-state NMR is uniquely suited to analyze and quantify composition in bacterial biofilms

A bottom-up approach can be used to fit spectra of biofilm parts to the intact matrix

A top-down approach examines complex matrix material without access to matrix parts

Important parameters of matrix composition are presented for E. coli and V. cholerae

Parameters of matrix composition are needed to understand matrix assembly and function

Acknowledgements

Electron microscopy images in Figures 1B and 1C were kindly provided by Dr. Ji Youn Lim, and assistance from the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility is acknowledged. L.C. gratefully acknowledges support from the NIH Director's New Innovator Award, Stanford University, and the Stanford Terman Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bloch F, Hansen WW, Packard M. The Nuclear Induction Experiment. Phys Rev. 1946;70:474–485. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purcell EM, Torrey HC, Pound RV. Resonance Absorption by Nuclear Magnetic Moments in a Solid. Phys Rev. 1946;69:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendrew JC, Dickerson RE, Strandberg BE, Hart RG, Davies DR, Phillips DC, Shore VC. Structure of Myoglobin - 3-Dimensional Fourier Synthesis at 2 a Resolution. Nature. 1960;185:422–427. doi: 10.1038/185422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perutz MF, Rossmann MG, Cullis AF, Muirhead H, Will G, North ACT. Structure of Haemoglobin - 3-Dimensional Fourier Synthesis at 5.5-a Resolution, Obtained by X-Ray Analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: From the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: Survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:167-+. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watnick P, Kolter R. Biofilm, city of microbes. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2675–2679. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2675-2679.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichhardt C, Cegelski L. Solid-state NMR for bacterial biofilms. Mol Phys. 2014;112:887–894. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2013.837983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang B, Powers R. Analysis of bacterial biofilms using NMR-based metabolomics (vol 4, pg 1273, 2012) Future Med Chem. 2012;4:1764–1764. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang J, Dorrestein PC. Emerging mass spectrometry techniques for the direct analysis of microbial colonies. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2014;19:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watrous JD, Dorrestein PC. Imaging mass spectrometry in microbiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:683–694. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland IW. Biofilm exopolysaccharides: a strong and sticky framework. Microbiol-Uk. 2001;147:3–9. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allison DG. The Biofilm Matrix. Biofouling. 2003;19:139–150. doi: 10.1080/0892701031000072190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karunakaran E, Mukherjee J, Ramalingam B, Biggs CA. "Biofilmology": a multidisciplinary review of the study of microbial biofilms. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2011;90:1869–1881. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao YQ, Cody GD, Harding AK, Wilmes P, Schrenk M, Wheeler KE, Banfield JF, Thelen MP. Characterization of Extracellular Polymeric Substances from Acidophilic Microbial Biofilms. Appl Environ Microb. 2010;76:2916–2922. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02289-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrate OA, Zhou XX, Reichhardt C, Cegelski L. Sum of the Parts: Composition and Architecture of the Bacterial Extracellular Matrix. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4286–4294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichhardt C, Fong JCN, Yildiz F, Cegelski L. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae extracellular matrix: A top-down solid-state NMR approach. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cegelski L, Pinkner JS, Hammer ND, Cusumano CK, Hung CS, Chorell E, Aberg V, Walker JN, Seed PC, Almqvist F, Chapman MR, Hultgren SJ. Small-molecule inhibitors target Escherichia coli amyloid biogenesis and biofilm formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:913–919. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cegelski L, Smith CL, Hultgren SJ. Adhesion, Microbial. In: Schaechter M, editor. Encyclopedia of Microbiology. Third Edition. Oxford: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim JY, Pinkner JS, Cegelski L. Community behavior and amyloid-associated phenotypes among a panel of uropathogenic E. coli. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2014;443:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen A, Jonsson A, Normark S. Fibronectin Binding Mediated by a Novel Class of Surface Organelles on Escherichia-Coli. Nature. 1989;338:652–655. doi: 10.1038/338652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman MR, Robinson LS, Pinkner JS, Roth R, Heuser J, Hammar M, Normark S, Hultgren SJ. Role of Escherichia coli curli operons in directing amyloid fiber formation. Science. 2002;295:851–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1067484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romling U, Bokranz W, Rabsch W, Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Tschape H. Occurrence and regulation of the multicellular morphotype in Salmonella serovars important in human disease. Int J Med Microbiol. 2003;293:273–285. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beloin C, Roux A, Ghigo JM. Escherichia coli biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol. 2008;322:249–289. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C, Lim JY, Fuller GG, Cegelski L. Quantitative Analysis of Amyloid-Integrated Biofilms Formed by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli at the Air-Liquid Interface. Biophys J. 2012;103:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C, Lim JY, Fuller GG, Cegelski L. Disruption of Escherichia coli Amyloid-Integrated Biofilm Formation at the Air-Liquid Interface by a Polysorbate Surfactant. Langmuir. 2013;29:920–926. doi: 10.1021/la304710k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollenbeck Emily C., Fong Jiunn C.N., Lim Ji Y., Yildiz Fitnat H., Fuller Gerald G., Cegelski L. Molecular Determinants of Mechanical Properties of V. cholerae Biofilms at the Air-Liquid Interface. Biophys J. 107:2245–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim JY, May JM, Cegelski L. Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Ethanol Elicit Increased Amyloid Biogenesis and Amyloid-Integrated Biofilm Formation in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microb. 2012;78:3369–3378. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07743-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Rohde M, Bokranz W, Romling U. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1452–1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gullion T, Schaefer J. Rotational-Echo Double-Resonance Nmr. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildiz FH, Schoolnik GK. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: Identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong JCN, Karplus K, Schoolnik GK, Yildiz FH. Identification and characterization of RbmA, a novel protein required for the development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm structure in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.1049-1059.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. The rbmBCDEF gene cluster modulates development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2319–2330. doi: 10.1128/JB.01569-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fong JCN, Syed KA, Klose KE, Yildiz FH. Role of Vibrio polysaccharide (vps) genes in VPS production, biofilm formation and Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. Microbiol-Sgm. 2010;156:2757–2769. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duperthuy M, Sjostrom AE, Sabharwal D, Damghani F, Uhlin BE, Wai SN. Role of the Vibrio cholerae Matrix Protein Bap1 in Cross-Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides. Plos Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altindis E, Fu Y, Mekalanos JJ. Proteomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae outer membrane vesicles. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E1548–E1556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403683111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leitner DR, Feichter S, Schild-Prufert K, Rechberger GN, Reidl J, Schild S. Lipopolysaccharide Modifications of a Cholera Vaccine Candidate Based on Outer Membrane Vesicles Reduce Endotoxicity and Reveal the Major Protective Antigen. Infect Immun. 2013;81:2379–2393. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01382-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berk V, Fong JCN, Dempsey GT, Develioglu ON, Zhuang XW, Liphardt J, Yildiz FH, Chu S. Molecular Architecture and Assembly Principles of Vibrio cholerae Biofilms. Science. 2012;337:236–239. doi: 10.1126/science.1222981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]