Abstract

Loss of function of DNA repair (DNAR) genes is associated with genomic instability and cancer predisposition; it also makes cancer cells reliant on a reduced set of DNAR pathways to resist DNA-targeted therapy, which remains the core of the anticancer armamentarium. Because the landscape of DNAR defects across numerous types of cancers and its relation with drug activity have not been systematically examined, we took advantage of the unique drug and genomic databases of the US National Cancer Institute cancer cell lines (the NCI-60) to characterize 260 DNAR genes with respect to deleterious mutations and expression down-regulation; 169 genes exhibited a total of 549 function-affecting alterations, with 39 of them scoring as putative knockouts across 31 cell lines. Those mutations were compared to tumor samples from 12 studies of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). Based on this compendium of alterations, we determined which DNAR genomic alterations predicted drug response for 20,195 compounds present in the NCI-60 drug database. Among 242 DNA damaging agents, 202 showed associations with at least one DNAR genomic signature. In addition to SLFN11, the Fanconi anemia-scaffolding gene SLX4 (FANCP/BTBD12) stood out among the genes most significantly related with DNA synthesis and topoisomerase inhibitors. Depletion and complementation experiments validated the causal relationship between SLX4 defects and sensitivity to raltitrexed and cytarabine in addition to camptothecin. Therefore, we propose new rational uses for existing anticancer drugs based on a comprehensive analysis of DNAR genomic parameters.

Keywords: DNA repair, Cancer, SLX4/FANCP/BTBD12, cytarabine, raltitrexed, NCI-60

1. Introduction

The DNA damage response is a network of cellular processes that sense and respond to DNA damage through the coordination of multiple pathways including DNA repair, replication, transcription, apoptosis, cell cycle and chromatin remodeling. Loss of function of DNA repair genes is associated with genomic instability, which increases cancer susceptibility by enabling the accumulation of random mutations, among which cancer-driver mutations arise [1]. However, as defects in DNA repair genes can fuel the mutator phenotype, they also make cancer cells reliant on a reduced set of genes or pathways for survival [2]. This peculiarity can be exploited therapeutically (synthetic lethality) by matching anticancer drugs with specific genetic defects, as exemplified by the selective cytotoxicity of PARP inhibitors in BRCA1- or BRCA2- defective cells [3, 4].

Although much is known about the fundamental molecular mechanisms involved in DNA repair [5–7], the landscape of DNA repair genomic defects across cancers has not been systematically investigated. The unbiased identification of genomic features leading to differential drug sensitivity has begun to yield fruits with the availability of drug and genomic databases for cancer cell lines [8, 9]. Use of these large-scale pharmacogenomic databases provides new means for the identification of frequently altered cancer genes and novel gene-drug interactions with potential applications in the clinic [9].

The US National Cancer Institute cancer cell lines (the NCI-60) is the most annotated set of cell lines with the largest drug and matching genomic databases [10–12]. It recently became the first panel of cancer-derived cells with whole exome sequencing annotations in addition to various gene and microRNA expression databases [13, 14]. The NCI-60, which are derived from 9 tissues of origin: breast, colon, skin, blood, central nervous system, lung, prostate, ovaries and kidney, have yielded decades of information pertinent to a large number of repeated assays for thousands of compounds including DNA targeted drugs both FDA-approved and investigational [15], as well as a variety of molecular and cellular processes [16, 17]. In the present study, we first compared the NCI-60 with the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) cell line panel [9], and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) tumor samples to further identify the most frequently altered DNA repair genes across a broad spectrum of cancer types. We also report an extensive collection of putative knockouts across the NCI-60. Additionally, 20,195 compounds (including 644 FDA approved or investigational drugs) have been screened on the NCI-60 [10–12], allowing statistical and machine-learning techniques to determine the extent to which DNAR alterations are associated with drug activity for thousands of compounds. This led to a focused analysis of the Fanconi anemia gene FANCP (SLX4/BTBD12) genomic alterations in connection with response to clinically relevant DNA replication inhibitors and topoisomerase inhibitors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DNA repair mutations and putative knockouts

The TCGA data previously normalized and filtered by Kandoth and colleagues [18] was obtained from the Synapse website1. The CCLE mutations are publicly available from Broad Institute 2 [19]. Whole exome sequencing (WOS), mRNA expression, copy number, microsatellite instability (MSI) and drug activity for the NCI-60 panel are publicly available from CellMiner3 or the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP)4. Details regarding acquisition of drug activity data, mRNA expression, copy number and mutation profiles, together with their normalization and analysis, were previously published [13, 14, 18, 19]. Drug activity was determined by DTP as the concentration of an agent required to cause 50% growth inhibition (GI50) as measured at 48 hours by a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay.

DNA repair genes were scored as altered by mutation in cell lines when affected by genetic variants present in heterozygosis (variant allele counts 10–95% in relation to the reference allele) or homozygosis (variant allele counts >95%), and predicted to impact protein function. Frameshift, non-frameshift, premature stop and splice site mutations were classified as impacting function, as well as missense mutations scored as damaging by SIFT [20] or Polyphen-2 [21] and non-common in the 1000 genomes [22] or ESP5400 [23] (frequency <0.5%). The percentage of counts for additional deleterious variants in the same gene and cell line was summed using the formula “1-(1-V1)*(1-V2)n”, where V1 stands for variant 1, V2 for variant 2.

We also considered two forms of potential knockouts: expression and mutation-based. We considered expression-based knockouts in cases where there was a lack of expression based on the following criteria: 1) mRNA transcript levels in a given cell line were smaller than minus 2 standard deviations from its median across the NCI-60 panel; 2) 1 standard deviation less than the next cell line with z-score ≥ -2 and 3) HuEx 1.0 Affy log2 probe average intensities smaller than 5 [14]. DNA repair genes were predicted as mutation-based knockouts when affected by genetic variants present in homozygosis and belonging to the following classes: frameshift, premature stop and splice site mutations, as well as missense mutations scored as damaging by SIFT [20] or Polyphen-2 [21] and totally absent in 1000 Genomes Project [22] and NHLBI-ESP 5400 Exomes Project [23]. The differences between the criteria for defining alterations and knockouts are summarized in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2. DNA repair and drug activity prediction in NCI-60

The elastic net regression algorithm [24, 25] was applied to identify genomic predictors of drug sensitivity for 644 FDA approved or investigational compounds, employing full genomic data for mRNA expression, copy number variation and whole exome sequencing. Prior to elastic net regression, mutations shown in Figure 2a were converted to binary format, based on presence = 1 or absence = 0. Then, these binary patterns were transformed to z-scores, as were the drug activity, mRNA expression, and copy number patterns over the NCI-60. Elastic net analyses were performed as described in the extended methods (Supporting Information). For each compound, the presence or absence of a given DNA repair feature among the leading genomic predictors was counted to obtain a matrix of DNA repair gene-drug response associations. Drugs were classified by mechanism of action according to annotations provided by DTP.

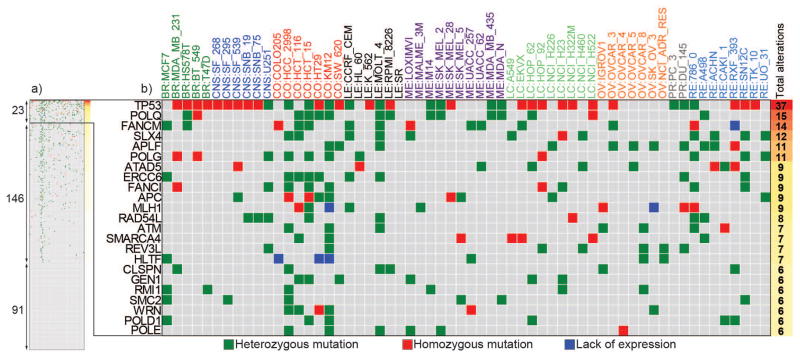

Figure 2. Catalog of DNA repair functional alterations across the NCI-60 cell lines.

a. Scope of alterations for the 260 DNA repair genes across the NCI-60 (the full version of the figure is in Supplementary Table S3). The subsets of genes altered in ≥10% (23), in at least one cell line (146) and not mutated (91) is indicated in the left side. b. Expanded view for the DNA repair genes mutated in more than 10% of the NCI-60. Mutations proposed to affect protein function and found at 0.5% in the normal population are represented by green and red squares when heterozygous and homozygous, respectively. Blue squares represent putative knockouts by lack of expression. The x-axis shows the cell lines organized by tissues of origin where BR: breast, CNS: central nervous system, CO: colorectal, LE: leukemia, ME: melanoma, LC: Lung, OV: ovarian, PR: prostate, RE: renal. The y-axis presents the DNA repair genes ranked by alteration frequency in the NCI-60; Cumulative numbers of alterations for each gene are noted at right.

Additionally, for each compound tested in the DTP screen (20,195 compounds), the difference in mean log GI50 (50% growth inhibition as reported by DTP) between mutant cell lines versus non-mutant cell lines was compared by t-test. For a given gene, the results for all compounds are presented in a volcano plot generated using GraphPad Prism 6; the y-axis shows the −log10 p-value. The false discovery rate was limited to 0.2 or less with adjusted (Benjamini Hochberg) P values no greater than 10−3.

2.3. Cell culture, drug sensitivity, siRNA transfection and RT-PCR

Previously described SLX4-defective and -complemented RA3331/E6E7/hTERT fibroblasts (referred as RA3331 and RA3331+WT SLX4, respectively) [26] were kindly provided from Dr. Agata Smogorzewska (Laboratory of Genome Maintenance and Human Genetics and Hematology, Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Details about the complementation system are provided in the supplementary information. Cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% (v/v) FBS (Gemini Bio-Products). Drug sensitivity to camptothecin (CPT) (Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Division of Cancer Treatment, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health), cytarabine (Ara-C) and raltitrexed (RTX) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was determined after 5 days of exposure by cell counting [27] with a Countess Automated cell counter (Invitrogen). HOP62 and DU-145 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% of Fetal Bovine Serum (v/v) (Gemini Bio-Producs). Drug sensitivity to CPT, Ara-C or RTX was determined by colony formation assay after 10 days (55). Three days prior to drug treatments, HOP62 and DU-145 cells were transfected with SLX4 siRNA or empty vector. SLX4 was knocked down with 20 nM of 4 SLX4 mRNA-targeting siRNAs from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon SMART pool (L-014895), using 5 uL lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; manufacturer’s instructions). SLX4 depletion efficiency was measured by quantitative RT-PCR (QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR kit; Qiagen) using total RNA extracted from empty vector-HOP62/DU-145 or SLX4 siRNA-HOP62/DU-145 cells with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The B2M gene was used as a control. SLX4-siRNA sequences and the primers employed for quantitative RT-PCR are shown in Supporting Information. T-tests were used to calculate statistical significance, and the p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Holm-Sidak in GraphPad Prism 6, which was also employed to plot the graphs.

3. Results

3.1. Atlas of DNA repair mutations in the NCI60, CCLE and cancers from TCGA

First, we assembled a catalog of 260 genes based on public DNA repair (DNAR) gene lists 5, 6 [18, 29] with some additions from recent literature (Supplementary Table 1). To put the NCI60 data in the context of other genomic databases, we compared the NCI-60 with the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)7 and the TCGA8 database. The CCLE consists of 947 cell lines with genomic data. However, mutations are available for only 66 of our 260 DNAR genes, and drug activities for only 24 drugs across 479 cell lines [19]. TCGA encompasses thousands of samples from dozens of tumor types [18]; a portion of which were recently organized into a high quality dataset from 12 tumor types, denoted as TCGA Pan-Cancer [30]. However, TCGA does not have exploitable pharmacological information.

Because the NCI-60 and CCLE cell lines do not have normal tissue matches, their mutations were scored after removing mutations in the normal population (determined in the 1000 Genomes and NHLBI-ESP 5400 Exomes projects), which are likely to represent germline mutations. Only the mutations predicted to impact protein function, based on mutation types and the SIFT and PolyPhen algorithms, were retained for analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

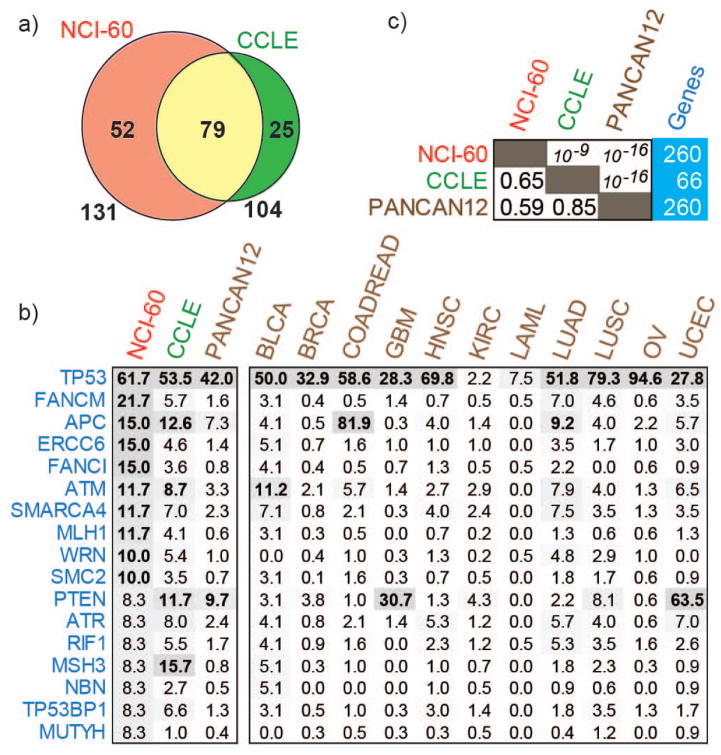

Mutations for 66 DNAR genes in the 39 cell lines sequenced in both the NCI-60 and CCLE showed high reproducibility (76% mutations found in the NCI-60 being the same in CCLE) (Fig. 1a). This result is consistent with prior global genomic analyses showing good concordance between the NCI-60 and CCLE genomic analyses [13]. An abbreviated list of the most frequently mutated genes common to the three databases (based on NCI-60 ranking) is presented in Figure 1b (complete data in Supplemental Table 2). Spearman correlation test showed highly significant rank order correlation for all three databases (Fig. 1c) and highest overall frequency of mutations in the NCI-60. Most genes at the top of the list are known for their association with cancer, including TP53, APC, ATM, ATR, TP53BP1, SMARCA4, MLH1, MSH3, RIF1 and PTEN. Additional genes that are frequently mutated in the cell lines and TCGA, for which cancer association has not been established previously, were also detected; mutations in POLQ occur in 25% of the NCI-60 cell lines and 9.2% of LUSC and 7.1% of BLCA; FANCM mutations occur in 21.7% of the 60 cell lines and 7% of LUAD, while SLX4 mutations occur in 20% of the NCI-60 and 5.2% of LUSC samples (Supplementary Table 2). An overview of the mutation frequencies across all studies is provided in Supplementary Table 2. Differences between mutation frequencies across the three databases are at least in part due to their tissue of origin composition, to the limited number of cell lines for each tissue type in the NCI-60, and to differences in sequencing methods and depth between the NCI-60 and the TCGA databases.

Figure 1. DNA repair mutations in cell lines and cancer.

a. Missense mutations were compared across 39 cell lines shared between NCI-60 and CCLE in 66 sequenced DNA repair genes and presented as Venn diagram. b. The mutation frequencies in the NCI-60, CCLE and TCGA tumor samples (the complete version of the figure is in Supplementary Table S2). c. Spearman’s rank order correlation for DNA repair mutation frequencies across NCI-60, CCLE and TCGA Pan-Cancer dataset (left side box), the coefficient (lower triangle), the p-value (upper triangle) and the number of genes used for correlation (right side box). The TCGA data was obtained directly from Kandoth et al., 2013 for the convenience of the reader. The mutation frequencies across all DNA repair genes and studies is presented in the Supplementary Table S2. TCGA cancer types; BLCA: Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma, BRCA: Breast Invasive Carcinoma, COADREAD: Colorectal Adenocarcinoma, GBM: Glioblastoma, HNSC: Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, KIRC: Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma, LAML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia, LUAD: Lung Adenocarcinoma, LUSC: Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma, OV: Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma, UCEC: Uterine Corpus Endometrioid Carcinoma.

Focusing on the NCI-60, in addition to the deleterious mutations, putative functional knockouts were scored based on undetectable mRNA expression across multiple microarray platforms and gene expression values ≤-2 z-score deviations from the mean expression of that gene for the 60 cell lines. We cataloged 549 functional alterations for 169 DNAR genes including heterozygous and low frequency SNPs (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 3). Detailed annotation for each variant is presented in Supplementary Table 4. The subset of 23 genes altered in ≥10% of NCI-60 lines is presented in Figure 2b. Among the known tumor suppressor genes, we found the expected three checkpoint genes (TP53, ATM and APC), but also four DNA polymerases (POLQ, REV3L, POLD1 and POLE, with POLQ altered in 15 different cell lines), two chromatin remodeling factors of the SWI/SNF family (SMARCA4 and HLTF), and two repair genes (MLH1 and ATAD5). In addition, several other DNAR genes not reported as frequently functionally altered in cancers include three Fanconi Anemia genes (FANCM, FANCP/SLX4, FANCI), two nucleases (APLF and GEN1), two helicases (WRN and RAD54L), and POLG (the mitochondrial DNA polymerase), ERCC6 (encoding the TCR-NER factor, CSB), CLSPN (encoding claspin the replication checkpoint regulator downstream from ATR), RMI1 (a cofactor of the BLM helicase complex), and SMC2 (encoding a central component of the condensing complex).

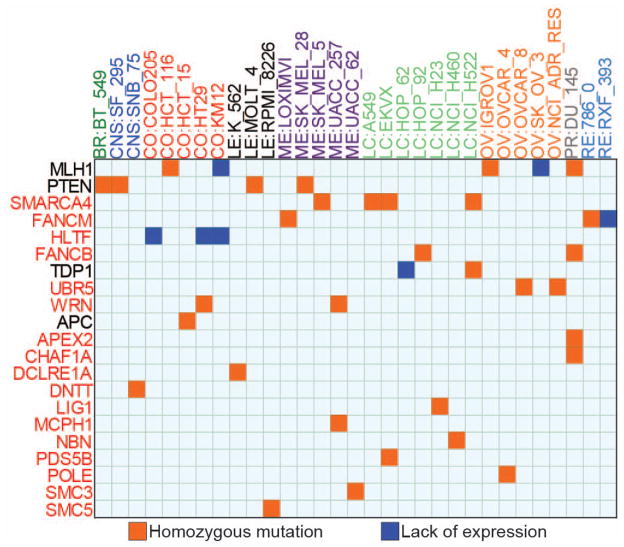

3.2. Cell lines with novel potential DNAR gene knockout across the NCI-60

Next, we compiled the list of cell lines with homozygous DNAR gene deleterious mutations or lack of expression to catalog the DNAR genetic knockouts across the NCI-60. High stringency deleterious mutations and undetectable expression criteria (Supplementary Fig. 1) identified 39 putative knockouts for 21 DNAR genes across 31 cell lines (Fig. 3). TP53 was excluded because it has been extensively studied previously [9, 13]. Yet, TP53 homozygous mutations are presented in Supplementary Table 5, as well as the detailed annotation for each homozygous variant.

Figure 3. Putative DNA repair genetic knockouts across the NCI-60 cell lines.

Homozygous mutations proposed to affect protein function and absent in 1000 genomes and ESP5400 are represented by orange squares. Blue squares represent putative knockouts by lack of expression. The x-axis shows the cell lines organized by tissues of origin where BR: breast, CNS: central nervous system, CO: colorectal, LE: leukemia, ME: melanoma, LC: Lung, OV: ovarian, PR: prostate, RE: renal. The y-axis presents the DNA repair genes ranked by alteration frequency in the NCI-60; Genes names highlighted in red are newly proposed functional knockouts.

Sixteen of the genes with homozygous deleterious mutations (red squares) and/or defective expression (blue squares) are novel (listed in red fonts in Fig. 3). The three previously known knockouts validate our results. MLH1 inactivation has been reported in HCT116, KM12, SK-OV3, IGROV1 and DU-145 cells [31, 32]; and PTEN inactivation in BT-549, SF-295, MOLT-4 and SK-MEL-2 [33, 34]. In addition, two lung cancer cell lines (HOP62 and NCI-H522) were recently shown to lack TDP1, a repair enzyme for hydrolyzing 3′-end blocking lesions generated by topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibitors, alkylation damage and chain terminators [35]. The previously unknown candidate knockout cell lines exhibited some tissue-specificity; SMARCA4, which is homozygously altered in 3 lung cancer cell lines and one melanoma line, has been shown to be frequently mutated in lung cancer [36]. Inactivation of HLTF by promoter hypermethylation was also recently reported in colon cancers [37], which is what we found in the three NCI-60 colon cancers cell lines, COL205, HT29 and KM12 with undetectable HLTF mRNA (and promoter hypermethylation, Supplementary Figure 2). Although FANCM and FANCB are among the least mutated genes in Fanconi patients [38], five NCI-60 cell lines scored as putative knockouts for FANCM (LOXIMVI, 786-0 and RXF-393) and FANCB (HOP92 and DU-145).

3.3. DNA repair alterations and drug activity predictions

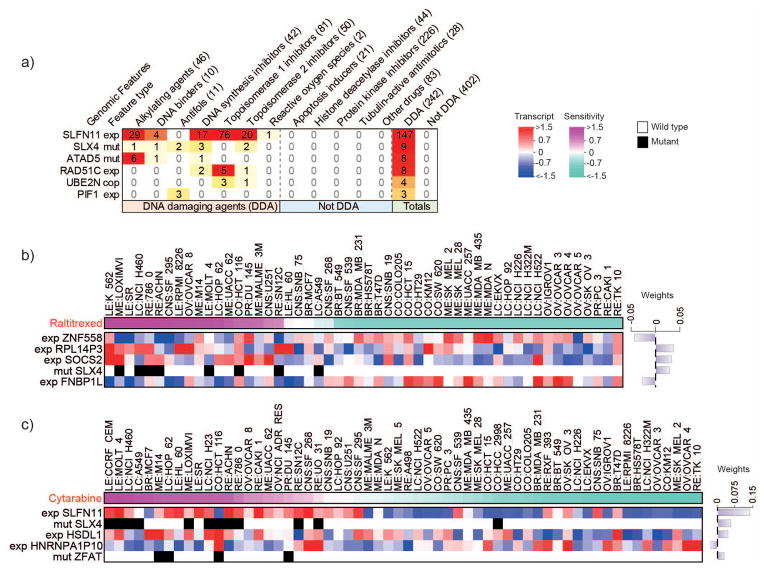

The relevance of DNA repair mutations to the anti-proliferative activity of 644 FDA-approved or investigational drugs was analyzed by elastic net regression [25]. This method allows the integrated analysis of multiple forms of molecular data, including gene expression, mutations and copy number, to produce a set of features that best predict drug activity. Among the features selected by elastic net analysis, predictors were also required to have a minimum correlation of 0.45 with the corresponding activity pattern (Supplementary Information) [9, 39]. For each compound, we scored the presence or absence of a DNA repair feature and obtained a matrix of associations between the top DNAR gene predictors and drug responses (Supplementary Table 6). Figure 4a summarizes the top DNAR genomic features associated with drug activity organized by drug mechanism of action. This method matched 83% (202 out of 242) DNA damaging agents with 42% (26 out of 62) DNAR genomic features (Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 4. DNA repair-Elastic net predictors by drug class and SLX4 mutations with response to raltitrexed (Tomudex®) and cytarabine (Cytosar-U® or Depocyt®).

a. Drug classes are organized by column, where numbers between parentheses correspond to the number of drugs from each class associated with one or more DNA repair genomic features by elastic net. Feature type indicates the source of genomic data associated with drug response, where exp: differential expression; mut: functional impacting mutations; cop: gene copy number. This figure is limited to DNA repair genomic features that associate exclusively with three or more DNA damaging drugs; the complete analysis is presented in the Supplementary Table S6. Elastic net modeling of genomic features that predict sensitivity to raltitrexed (b) or cytarabine (c). Cell lines are sorted by drug sensitivity, with the most sensitive lines at the left (pink) and least sensitive lines at the right (sea green). Top predictors are ranked by the magnitude of their weight with values indicated in a bar plot (right). Bars associated with predictors of sensitivity extend rightward while those for predictors of insensitivity extend leftward. Features based on expression range from low expression (blue) to high expression (red) and are prefixed by “exp”, while features based on mutations are black for presence or white for absence and are prefixed by “mut”. Cell lines without drug data were excluded from the analysis and plots.

SLFN11 expression appeared as a dominant predictor of drug activity for 147 out of 242 DNA damaging agents. The median correlation of SLFN11 expression with the activity of these drugs was 0.67 (Supplementary Table 7). SLFN11 was a predictive feature for 76 Top1 inhibitors, 29 alkylating agents, 20 topoisomerase II (Top2) inhibitors, 17 DNA synthesis inhibitors and 5 other DNA damaging agents, whereas none of the 402 non-DNA damaging agents, including protein kinase and tubulin inhibitors, showed significant association with SLFN11 (Fig. 4a). These results are consistent with the recently discovered role of SLFN11 in the DNA damage response [19, 40].

Other significant associations between specific DNAR genes and drug activity include SLX4 mutations (see below), ATAD5 deleterious mutations for alkylating drugs [13], high RAD51C (FANCO) expression for Top1 and DNA synthesis inhibitors, high UBE2N copy number for topoisomerase I and II inhibitors and high PIF1 expression for antifolates. Additional drug-DNAR gene association are included in Supplementary Table 6.

3.4. SLX4 mutations and response to DNA synthesis and topoisomerase inhibitors

Among the novel gene-drug associations found by elastic net, mutations in SLX4, which are relatively common in the NCI-60 (Fig. 2) and the TCGA lung squamous cell carcinomas (Supplemental Table 2), were associated with response to DNA synthesis inhibitors (nucleoside analogs) and antifolates (Fig. 4a). We reasoned that this novel finding might be logical as SLX4 encodes a non-enzymatic protein serving as a scaffold for several key endonucleases (XPF-ERCC1, MUS81-EME1 and SLX1) involved in the repair of replication-induced DNA damage and DNA lesions induced by mitomycin C, Top1 and PARP inhibitors [27]. Figure 4b and c shows representative elastic net features for raltitrexed and cytarabine. Overall, mutation of SLX4 was a prominent elastic net genomic feature for three DNA synthesis inhibitors (cytarabine, cyclocytidine and clofarabine); two antifolates (raltitrexed and pemetrexed); two Top2 inhibitors (m-AMSA and amonafide); and the binding agents (mitolactol and pyrazolo-acridine (Supplementary Table 6).

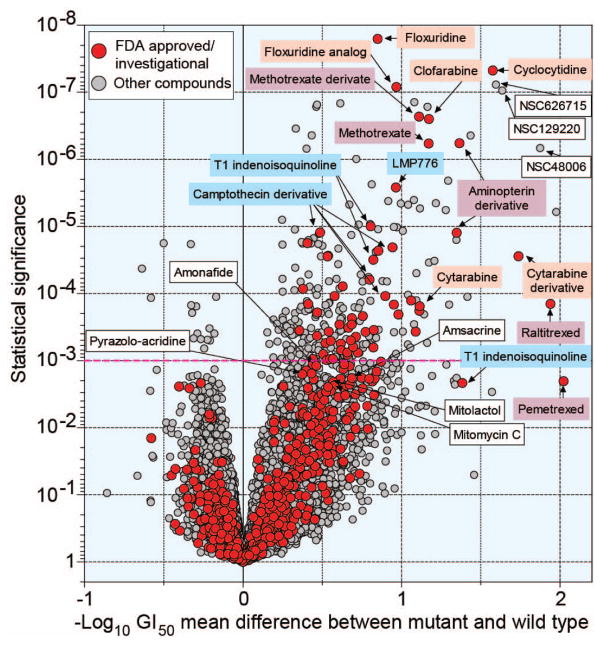

The difference in sensitivity between SLX4-mutated and non-mutated cell lines was further assessed for 20,195 compounds by multiple t-tests and represented as a Volcano plot (Fig. 5 and corresponding Supplemental Table 9 giving a detailed list of the significantly correlated drugs with their coordinates in the plot). Among the 644 FDA-approved and investigational drugs, nucleoside DNA synthesis inhibitors (in salmon) and antifolates (in purple) consistently showed a highly significant difference between SLX4 mutant and non-mutant cell lines. Camptothecins previously reported to be more active in SLX4-defective cells [27] were also more active in the NCI-60 SLX4 mutant cell lines; so were the non-camptothecin indenoisoquinoline Top1 inhibitors, including the LMP776 derivative in clinical trial [41]. Yet, SLX4 mutations were not among the elastic net leading genomic features for floxuridine, methotrexate and LMP776 (Supplemental Table 6). This is probably related to the multivariate nature of the elastic net regression algorithm, which selects the smallest set of combined predictive features to reconstruct the drug activity pattern, leading to the selection of other genomic feature combinations and exclusion of SLX4 mutations. Still, the elastic net modeling is currently an efficient and well-established technique with the capacity to recover multiple interacting drug response determinants. Both the CCLE and Sanger CGP pharmacogenomics data set projects featured elastic net in their initial analyses [9, 39]. In comparison studies with related methods, such as support vector machines and random forests, elastic net regression has been shown to produce highly predictive models [42, 43].

Figure 5. Correlation between mutations in SLX4 and drug activity represented as Volcano plot.

The x-axis is the difference in mean logGI50 between cell lines with and without SLX4 mutations. The y-axis shows the significance of the differential responses between SLX4 mutant and wild-type cells, represented as −log10 p value. Each red dot represents one of 20,195 from the DTP screening database; Green dots represent 644 FDA approved or investigational drugs. Names or NSCs of drugs discussed in the text or used for comparison are annotated. A red guideline is given based on FDR-adjusted P-value 10−3.

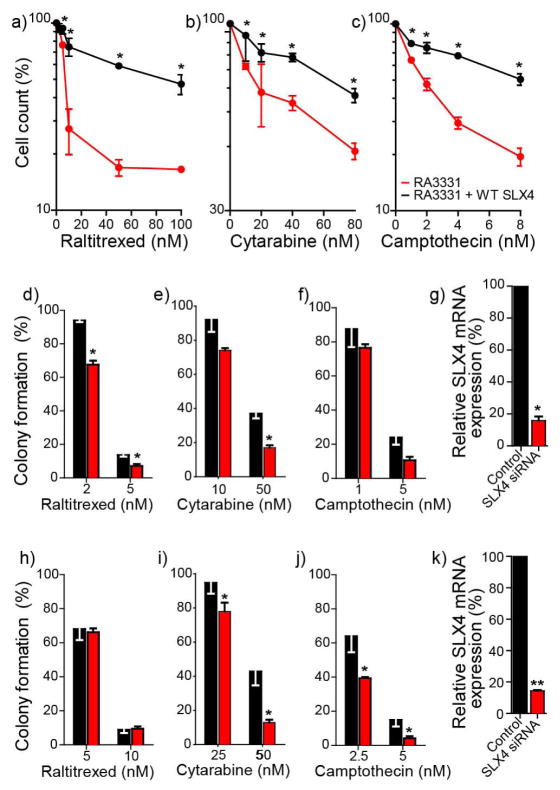

We experimentally tested the functional relevance of SLX4 for raltitrexed and cytarabine. Two experimental systems were used (Fig. 6); complementation, making use of a FANCP/SLX4-defective cell line (RA3331) and its SLX4-complemented isogenic counterpart [27] (Figure 6a–c), and a siRNA-based knockdown system, using the NCI-60 HOP62 (lung) and DU-145 (prostate) cells transfected with siRNA against SLX4 (Figure 6d–k). HOP62 and DU-145 were chosen because their SLX4 mRNA expression is near the NCI-60 average (Supplementary Table 8) and their siRNA knockdown efficiency was good (Fig. 6g & h). Drug activity was determined by two different methods; for RA3331 and RA3331+SLX4 we used cell counting after 5-day drug exposure [27]. Colony formation assays were used for HOP62 and DU-145, with camptothecin as positive control in all experiments [27]. SLX4 complementation conferred resistance in the FANCP RA3331 cells treated with raltitrexed, cytarabine and camptothecin (Fig. 6a–c). Conversely, SLX4 knockdown sensitized HOP62 cells to all three drugs (Fig. 6d–f), and DU-145 to cytarabine and camptothecin (Fig. 6h–j). Together, these results demonstrate that SLX4 is causally linked to the cytotoxic responses to raltitrexed and cytarabine. However, differences in the genomic background of DU-145 appear to have a stronger influence than SLX4 depletion for raltitrexed activity.

Figure 6. Causality of the association between SLX4 and raltitrexed, cytarabine and camptothecin activity.

Top panels: SLX4 complementation enhances the survival of SLX4-deficient RA3331 cells to raltitrexed (RTX, a), cytarabine (AraC, b) and camptothecin (CPT, c). SLX4-deficient RA3331 cells are in red, and RA3331 cells complemented with SLX4 are in black. Survival was determined by cell counting after 5 days exposure. Middle panels: SLX4 siRNA sensitizes HOP62 cells to raltitrexed (RTX, d), cytarabine (AraC, e) and camptothecin (CPT, f). Cytotoxic responses in HOP62 (black bars) and HOP62 plus siRNA targeting SLX4 (red bars) were determined by colony formation assay after 10 days exposure. g: SLX4 siRNA targeting efficiency was determined by RT-PCR (black bars represent HOP62 non-transfected cells, and red bars HOP62 cells transfected with SLX4 siRNA). Bottom panels: SLX4 siRNA sensitizes DU-145 cells to raltitrexed (RTX, h), cytarabine (AraC, i) and camptothecin (CPT, j). Cytotoxic responses in DU-145 (black bars) and DU-145 plus siRNA targeting SLX4 (red bars) were determined by colony formation assay after 10 days exposure. k: SLX4 siRNA targeting efficiency was determined by RT-PCR (black bars represent DU-145 non-transfected cells, and red bars DU-145 cells transfected with SLX4 siRNA. Error bars represent SD from at least 2 experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical differences by multiple t-tests: * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, we first cataloged the genetic alterations of 260 DNAR genes across the NCI-60 and CCLE cancer cell lines, and thousands of tumor samples from TCGA. Next, we focused on the NCI-60 to provide a detailed atlas of deleterious mutations for DNAR genes and potential knockout cell lines. In the second part of the study, we concentrated on establishing novel associations between genomic alterations and drug responses to provide novel predictive biomarkers for DNA damaging agents, which constitute the backbone of chemotherapy. These different steps are schematized in Supplemental Figure 4.

The results presented here demonstrate a highly significant correlation and overlap between the overall frequencies of DNAR mutations for cancer cell lines and cancer samples, and a relatively high frequency of DNAR gene inactivation in cancers. This result is consistent with the possibility that inactivation of DNAR genes confers an overall mutator phenotype, which can act as a positive selection factor for the growth of cancer cells in adverse environments. Notably, the NCI-60 exhibits the highest frequency of mutants, and the CCLE also reveals higher mutant frequency than the TCGA samples. This could be related to the accumulation of mutations during the adaptation and establishment of cell lines, as they need to grow in an artificial environment. Sequencing depth may also be a contributing factor; in which case focused studies would be warranted to further examine tumor samples for the DNAR genes that are most frequently mutated in the cell lines.

Additionally, examination of the NCI-60 cell lines with homozygous deleterious variants and expression-based knockouts provides a novel collection of 31 different cancer cell lines for 21 DNAR genes (Figure 3). To the four previously known genes (MLH1, PTEN, TDP1 and APC), the present study adds promoter methylation as the mechanism for MLH1 knockout in colon KM12 and gene copy number loss for ovarian SK_OV3. Hypermethylation also accounts for lack of message for the SWI/SNF helicase-like transcription factor HLTF in three of the colon cell lines (COLO205, HT29 and KM12), which is consistent with genomic data from human colon cancers [37]. We anticipate that this resource will be useful for further functional DNA repair studies and for suggesting opportunities for complementation experiments.

Remarkably, an unexpected high incidence of heterozygous mutations was observed for several of the Fanconi anemia genes [38]: FANCM, FANCP (SLX4) and FANCI across the NCI-60. Germline homozygous mutations in Fanconi anemia genes are well known to associate with acute myeloid leukemia and solid tumors predisposition in Fanconi patients [44]. However, only four Fanconi genes have been shown to associate with breast and/or ovarian cancer predisposition when targeted by single gene copy mutations [44]: BRCA2 (FANCD1), RAD51C (FANCO), PALB2 (FANCN) and BRIP1 (FANCJ). While some studies indicated that single gene copy or somatic mutations in FANCM [45], FANCI [45] and SLX4 [46–51] are not significantly associated with non-BRCA mutant breast or ovarian cancers, further investigations are warranted [52]. Examination of the TCGA data revealed a 7% incidence of FANCM mutations in lung adenocarcinomas and SLX4 mutations in 5.2% in lung squamous cell carcinomas (see Supplementary Table 2).

Owing to the uniquely rich drug response database of the NCI-60 [40], we were able to systematically determine significant associations between genomic features (i.e., mutations, gene expression and copy number levels) of DNAR genes and cytotoxic response to drugs and compounds in the NCI-60 database. Using the elastic net regression method, which reconstructs drug activity patterns through linear regression and integration of genomic features, we found hundreds of potential interactions between genomic features of DNAR genes and drug activity; the vast majority of these interactions involved DNA damaging agents (see Fig. 4 and Supplemental Table 6). One remarkable result was the strong association of SLFN11 expression and the activity of 147 DNA damaging compounds (out of 242). This result extends recent observations demonstrating the importance of SLFN11 for response to DNA damaging agents [19, 40], and suggests the importance of testing SLFN11 expression as predictive biomarker with potential benefit to a large number of patients treated with DNA damaging agents across multiple cancer types.

Our study reveals that SLX4 deleterious mutations are associated with enhanced cellular sensitivity to several DNA synthesis inhibitors. Furthermore, we show that SLX4 complementation increases resistance to raltitrexed and cytarabine, while SLX4 depletion increases the sensitivity to both drugs (Fig. 6). These novel gene-drug relations demonstrate that SLX4 defects can drive drug response to the antifolate, raltitrexed and the DNA synthesis inhibitor, cytarabine. These findings extend the relevance of SLX4 beyond the response to Top1 and PARP inhibitors, and DNA alkylating agents [53]. The implication of SLX4 in the repair of replication-associated DNA damage is consistent with the function of SLX4 as a multi-nuclease scaffold forming complexes with MUS81-EME1, XPF-ERCC1 and SLX1 [27], and with the prior findings that homologous recombination is involved in the cellular response to raltitrexed [54] and camptothecin [55]. SLX4 has also been shown to interact with MSH2/MSH3, TERF2-TERF2IP, C20orf94 and PLK1, although the pharmacological relevance of these interactions remains to be elucidated [53]. Nevertheless, our results suggest the potential importance of assessing tumors for SLX4 mutations to determine their response to a wide range of DNA damaging drugs including raltitrexed and cytarabine.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We catalogued DNA repair mutations across the NCI-60, CCLE and TCGA datasets

We reveal new gene-drug associations for 260 DNA repair genes across the NCI-60

SLX4 mutations sensitize to topoisomerases and DNA synthesis inhibitors

This study provides a database for DNA repair alterations in cancer

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Agata Smogorzewska for kindly providing the FANCP cell lines, RA3331 and RA3331 complemented with WT SLX4. We thank Kurt W. Kohn, Barry Zeeberg and Salim Khiati for their constructive discussions and suggestions on bioinformatics and methodologies. Fabricio G. Sousa and Renata Matuo were supported by grants from Science Without Borders – CNPq and from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute. Our studies are supported by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (Z01 BC006150). This work was also supported in part by a MSKCC Genome Data Analysis Center grant (U24 CA143840) awarded as part of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and by FUNDECT/CNPq (DCR 013/2014).

Appendix A. Supplementary information

Supplemental methods associated with this article can be found in the online version at [DNAREPAIRLINK].

Appendix B. Supplementary figures

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at [DNAREPAIRLINK].

Appendix C. Supplementary tables

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at [DNAREPAIRLINK].

Footnotes

Competing interests

There are no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, Ashworth A. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindahl T, Wood RD. Quality control by DNA repair. Science. 1999;286:1897–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanawalt PC. Paradigms for the three rs: DNA replication, recombination, and repair. Mol Cell. 2007;28:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyama T, Wilson DM. 3rd, DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:620–636. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scherf U, Ross DT, Waltham M, Smith LH, Lee JK, Tanabe L, Kohn KW, Reinhold WC, Myers TG, Andrews DT, Scudiero DA, Eisen MB, Sausville EA, Pommier Y, Botstein D, Brown PO, Weinstein JN. A gene expression database for the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;24:236–244. doi: 10.1038/73439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, Greenman CD, Dastur A, Lau KW, Greninger P, Thompson IR, Luo X, Soares J, Liu Q, Iorio F, Surdez D, Chen L, Milano RJ, Bignell GR, Tam AT, Davies H, Stevenson JA, Barthorpe S, Lutz SR, Kogera F, Lawrence K, McLaren-Douglas A, Mitropoulos X, Mironenko T, Thi H, Richardson L, Zhou W, Jewitt F, Zhang T, O’Brien P, Boisvert JL, Price S, Hur W, Yang W, Deng X, Butler A, Choi HG, Chang JW, Baselga J, Stamenkovic I, Engelman JA, Sharma SV, Delattre O, Saez-Rodriguez J, Gray NS, Settleman J, Futreal PA, Haber DA, Stratton MR, Ramaswamy S, McDermott U, Benes CH. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoemaker RH. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holbeck SL, Collins JM, Doroshow JH. Analysis of Food and Drug Administration-approved anticancer agents in the NCI60 panel of human tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1451–1460. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein JN. Drug discovery: Cell lines battle cancer. Nature. 2012;483:544–545. doi: 10.1038/483544a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abaan OD, Polley EC, Davis SR, Zhu YJ, Bilke S, Walker RL, Pineda M, Gindin Y, Jiang Y, Reinhold WC, Holbeck SL, Simon RM, Doroshow JH, Pommier Y, Meltzer PS. The exomes of the NCI-60 panel: a genomic resource for cancer biology and systems pharmacology. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4372–4382. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhold WC, Sunshine M, Liu H, Varma S, Kohn KW, Morris J, Doroshow J, Pommier Y. CellMiner: a web-based suite of genomic and pharmacologic tools to explore transcript and drug patterns in the NCI-60 cell line set. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3499–3511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, Plowman J, Boyd M. Display and analysis of patterns of differential activity of drugs against human tumor cell lines: development of a mean graph and COMPARE algorithm. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1088–1092. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.14.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn KW, Zeeberg BR, Reinhold WC, Sunshine M, Luna A, Pommier Y. Gene expression profiles of the NCI-60 human tumor cell lines define molecular interaction networks governing cell migration processes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeeberg BR, Reinhold W, Snajder R, Thallinger GG, Weinstein JN, Kohn KW, Pommier Y. Functional categories associated with clusters of genes that are co-expressed across the NCI-60 cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, Leiserson MD, Miller CA, Welch JS, Walter MJ, Wendl MC, Ley TJ, Wilson RK, Raphael BJ, Ding L. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, Reddy A, Liu M, Murray L, Berger MF, Monahan JE, Morais P, Meltzer J, Korejwa A, Jane-Valbuena J, Mapa FA, Thibault J, Bric-Furlong E, Raman P, Shipway A, Engels IH, Cheng J, Yu GK, Yu J, Aspesi P, Jr, de Silva M, Jagtap K, Jones MD, Wang L, Hatton C, Palescandolo E, Gupta S, Mahan S, Sougnez C, Onofrio RC, Liefeld T, MacConaill L, Winckler W, Reich M, Li N, Mesirov JP, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Ardlie K, Chan V, Myer VE, Weber BL, Porter J, Warmuth M, Finan P, Harris JL, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Morrissey MP, Sellers WR, Schlegel R, Garraway LA. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genomes Project C. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ESP5400. Exome Variant Server - NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project. Seattle, WA: [acessed 2013]. URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou H, Zhang HH. On the Adaptive Elastic-Net with a Diverging Number of Parameters. Ann Stat. 2009;37:1733–1751. doi: 10.1214/08-AOS625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Stat Soc B. 2005;67:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, Lach FP, Desetty R, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD, Smogorzewska A. Mutations of the SLX4 gene in Fanconi anemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:142–146. doi: 10.1038/ng.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y, Spitz GS, Veturi U, Lach FP, Auerbach AD, Smogorzewska A. Regulation of multiple DNA repair pathways by the Fanconi anemia protein SLX4. Blood. 2013;121:54–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood RD, Mitchell M, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes, 2005. Mutat Res. 2005;577:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taverna P, Liu L, Hanson AJ, Monks A, Gerson SL. Characterization of MLH1 and MSH2 DNA mismatch repair proteins in cell lines of the NCI anticancer drug screen. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;46:507–516. doi: 10.1007/s002800000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeh CC, Lee C, Dahiya R. DNA mismatch repair enzyme activity and gene expression in prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:409–413. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikediobi ON, Davies H, Bignell G, Edkins S, Stevens C, O’Meara S, Santarius T, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Brackenbury L, Buck G, Butler A, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Hunter C, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Kosmidou V, Lugg R, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Parker A, Perry J, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Smith R, Solomon H, Stephens P, Teague J, Tofts C, Varian J, Webb T, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Reinhold W, Weinstein JN, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Wooster R. Mutation analysis of 24 known cancer genes in the NCI-60 cell line set. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2606–2612. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hlobilkova A, Knillova J, Svachova M, Skypalova P, Krystof V, Kolar Z. Tumour suppressor PTEN regulates cell cycle and protein kinase B/Akt pathway in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1015–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao R, Das BB, Chatterjee R, Abaan OD, Agama K, Matuo R, Vinson C, Meltzer PS, Pommier Y. Epigenetic and genetic inactivation of tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) in human lung cancer cells from the NCI-60 panel. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;13:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez-Nieto S, Canada A, Pros E, Pinto AI, Torres-Lanzas J, Lopez-Rios F, Sanchez-Verde L, Pisano DG, Sanchez-Cespedes M. Massive parallel DNA pyrosequencing analysis of the tumor suppressor BRG1/SMARCA4 in lung primary tumors. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:E1999–2017. doi: 10.1002/humu.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandhu S, Wu X, Nabi Z, Rastegar M, Kung S, Mai S, Ding H. Loss of HLTF function promotes intestinal carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moldovan GL, D’Andrea AD. How the fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:223–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, Reddy A, Liu M, Murray L, Berger MF, Monahan JE, Morais P, Meltzer J, Korejwa A, Jane-Valbuena J, Mapa FA, Thibault J, Bric-Furlong E, Raman P, Shipway A, Engels IH, Cheng J, Yu GK, Yu J, Aspesi P, de Silva M, Jagtap K, Jones MD, Wang L, Hatton C, Palescandolo E, Gupta S, Mahan S, Sougnez C, Onofrio RC, Liefeld T, MacConaill L, Winckler W, Reich M, Li N, Mesirov JP, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Ardlie K, Chan V, Myer VE, Weber BL, Porter J, Warmuth M, Finan P, Harris JL, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Morrissey MP, Sellers WR, Schlegel R, Garraway LA. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–307. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zoppoli G, Regairaz M, Leo E, Reinhold WC, Varma S, Ballestrero A, Doroshow JH, Pommier Y. Putative DNA/RNA helicase Schlafen-11 (SLFN11) sensitizes cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15030–15035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205943109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pommier Y. DNA Topoisomerases and Cancer. Springer & Humana Press; New York, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang IS, Neto EC, Guinney J, Friend SH, Margolin AA. Systematic assessment of analytical methods for drug sensitivity prediction from cancer cell line data. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2014:63–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papillon-Cavanagh S, De Jay N, Hachem N, Olsen C, Bontempi G, Aerts HJ, Quackenbush J, Haibe-Kains B. Comparison and validation of genomic predictors for anticancer drug sensitivity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:597–602. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kottemann MC, Smogorzewska A. Fanconi anaemia and the repair of Watson and Crick DNA crosslinks. Nature. 2013;493:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature11863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia MJ, Fernandez V, Osorio A, Barroso A, Fernandez F, Urioste M, Benitez J. Mutational analysis of FANCL, FANCM and the recently identified FANCI suggests that among the 13 known Fanconi Anemia genes, only FANCD1/BRCA2 plays a major role in high-risk breast cancer predisposition. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1898–1902. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Quiles F, Blanco I, Teule A, Feliubadalo L, Valle JD, Salinas M, Izquierdo A, Darder E, Schindler D, Capella G, Brunet J, Lazaro C, Pujana MA. Analysis of SLX4/FANCP in non-BRCA1/2-mutated breast cancer families. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Garibay GR, Diaz A, Gavina B, Romero A, Garre P, Vega A, Blanco A, Tosar A, Diez O, Perez-Segura P, Diaz-Rubio E, Caldes T, de la Hoya M. Low prevalence of SLX4 loss-of-function mutations in non-BRCA1/2 breast and/or ovarian cancer families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catucci I, Colombo M, Verderio P, Bernard L, Ficarazzi F, Mariette F, Barile M, Peissel B, Cattaneo E, Manoukian S, Radice P, Peterlongo P. Sequencing analysis of SLX4/FANCP gene in Italian familial breast cancer cases. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landwehr R, Bogdanova NV, Antonenkova N, Meyer A, Bremer M, Park-Simon TW, Hillemanns P, Karstens JH, Schindler D, Dork T. Mutation analysis of the SLX4/FANCP gene in hereditary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:1021–1028. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1681-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah S, Kim Y, Ostrovnaya I, Murali R, Schrader KA, Lach FP, Sarrel K, Rau-Murthy R, Hansen N, Zhang L, Kirchhoff T, Stadler Z, Robson M, Vijai J, Offit K, Smogorzewska A. Assessment of Mutations in Hereditary Breast Cancers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bakker JL, van Mil SE, Crossan G, Sabbaghian N, De Leeneer K, Poppe B, Adank M, Gille H, Verheul H, Meijers-Heijboer H, de Winter JP, Claes K, Tischkowitz M, Waisfisz Q. Analysis of the novel fanconi anemia gene SLX4/FANCP in familial breast cancer cases. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:70–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.22206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiiski JI, Pelttari LM, Khan S, Freysteinsdottir ES, Reynisdottir I, Hart SN, Shimelis H, Vilske S, Kallioniemi A, Schleutker J, Leminen A, Butzow R, Blomqvist C, Barkardottir RB, Couch FJ, Aittomaki K, Nevanlinna H. Exome sequencing identifies FANCM as a susceptibility gene for triple-negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svendsen JM, Smogorzewska A, Sowa ME, O’Connell BC, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. Mammalian BTBD12/SLX4 assembles a Holliday junction resolvase and is required for DNA repair. Cell. 2009;138:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waldman BC, Wang Y, Kilaru K, Yang Z, Bhasin A, Wyatt MD, Waldman AS. Induction of intrachromosomal homologous recombination in human cells by raltitrexed, an inhibitor of thymidylate synthase. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1624–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Regairaz M, Zhang Y-W, Fu H, Agama KK, Tata N, Agrawal S, Aladjem MI, Pommier Y. Mus81-mediated DNA cleavage resolves replication forks stalled by topoisomerase I-DNA complexes. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;195:739–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.