Abstract

Changes in resting membrane potential (RMP) regulate membrane excitability. K+ conductance(s) are one of the main factors in regulating RMP. The functional role of K+ conductances has not been studied the in human gastric corpus smooth muscles (HGCS). To examine the role of K+ channels in regulation of RMP in HGCS we employed microelectrode recordings, patch-clamp, and molecular approaches. Tetraethylammonium and charybdotoxin did not affect the RMP, suggesting that BK channels are not involved in regulating RMP. Apamin, a selective small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK) blocker, did not show a significant effect on the membrane excitability. 4-Aminopyridine, a Kv channel blocker, caused depolarization and increased the duration of slow wave potentials. 4-Aminopyridine also inhibited a delayed rectifying K+ current in isolated smooth muscle cells. End-product RT-PCR gel detected Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 in human gastric corpus muscles. Glibenclamide, an ATP-sensitive K+ channel (KATP) blocker, did not induce depolarization, but nicorandil, a KATP opener, hyperpolarized HGCS, suggesting that KATP are expressed but not basally activated. Kir6.2 transcript, a pore-forming subunit of KATP was expressed in HGCS. A low concentration of Ba2+, a Kir blocker, induced strong depolarization. Interestingly, Ba2+-sensitive currents were minimally expressed in isolated smooth muscle cells under whole-cell patch configuration. KCNJ2 (Kir2.1) transcript was expressed in HGCS. Unique K+ conductances regulate the RMP in HGCS. Delayed and inwardly rectifying K+ channels are the main candidates in regulating membrane excitability in HGCS. With the development of cell dispersion techniques of interstitial cells, the cell-specific functional significance will require further analysis.

Keywords: human stomach, resting membrane potentials, gastrointestinal motility, slow wave potentials, smooth muscle cell

in gastric corpus and antrum, many studies have focused on the mechanisms of spontaneous electrical activity (4, 7, 9, 10, 25, 29, 33). Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) have been shown to generate or initiate spontaneous electrical activity in gastric smooth muscle. Changes in the resting membrane potentials (RMP) of the gastric smooth muscle can affect excitability of slow wave potentials (SWP). For instance, slow wave depolarization drives the changes in rhythmic contractility in gastric smooth muscle. The RMP can mainly be decided by the expression of K+ channels, although other inward conductance can affect the RMP (3, 19). Voltage-dependent and -independent K+ channels can be involved in setting RMP. Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BK) and voltage-dependent delayed rectifying K+ channels (Kv) are common candidates for voltage-dependent K+ channels. Voltage-independent K+ channels such as small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (SK), ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP), and inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Kir) may be involved in regulating RMP (19).

It has been shown that BK channel blockers [tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) or charybdotoxin (ChTX)] did not affect the RMP in colonic smooth muscles. 4-Aminopyridine (4-AP, a Kv channel blocker) induces depolarization in colonic smooth muscle, suggesting that activation or inhibition of Kv channels can affect the changes in RMP (17, 18). Apamin (a specific SK channel blocker) and glibenclamide (GBC, a KATP channel blocker) also depolarize colonic smooth muscle (16, 21). These data suggested that ongoing activities of SK and KATP channels are important conductances in regulating RMP. Low concentrations of Ba2+ (μM range) inhibit Kir channels. Ba2+ also induces depolarization in colonic smooth muscle (6).

Although electrical activity with use of intracellular microelectrodes was reported in human gastric smooth muscles (4, 7, 25), there is no report about the role of K+ conductances on membrane excitability in human gastric corpus smooth muscle (HGCS). Understanding the role of K+ channel in HGCS is crucial to explain the spontaneous electrical rhythmicity. Unfortunately, isolation of interstitial cells for patch experiment in HGCS is technically limited. Therefore, we focused on K+ channel expression in smooth muscle using microelectrode recordings, patch-clamp, and molecular analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human gastric corpus tissue preparation.

All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center (no. 2010-09-015). A nonpathological segment of human gastric corpus tissues was used in this study obtained from gastrectomy patients (n = 36, average age 64) of either sex at Samsung Medical Center. The mucosa was removed from the sample by sharp dissection. Thin strips of tissues were cut from the sample by use of parallel scalpel blades mounted on a scalpel handle. The final strips cut parallel to the longitudinal muscle fibers measured 10 mm (or less) in length. Tissues were pinned to Sylgard elastomer-coated Corning dish and placed in a recording chamber. The tissues were incubated at 37 ± 0.5°C with oxygenated Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate solution (KRB; see below).

Intracellular microelectrode recordings.

After 1-h incubation in the recording chamber, microelectrode impalements of circular smooth muscle cells were made with glass microelectrodes having resistances of 80–120 MΩ with 3 M KCl. Transmembrane potentials were recorded with an Axon Instruments high-impedance microelectrode amplifier and data were recorded onto a PC running Axo Scope 10.0 data acquisition software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Data were analyzed by Clampfit 10.0 (Molecular Devices). All experiments were performed in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM).

Smooth muscle cell preparation.

Freshly dispersed smooth muscle cells were prepared from HGCS strips with use of Ca2+-free Hanks' solution containing (in mmol/l) 125 NaCl, 5.36 KCl, 15.5 NaOH, 0.336 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 10 glucose, 2.9 sucrose, and 11 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris. Dissected muscle strips were incubated for 40–50 min at 37°C in a Ca2+-free solution (2 ml) containing collagenase (4 mg/ml, Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), trypsin inhibitor (8 mg/ml), fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (8 mg/ml), papain (2 mg/ml), and l-dithiothreitol (0.3 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Tissue pieces were washed with Ca2+-free solution and then gently agitated to create a cell suspension. Dispersed smooth muscle cells were stored at 4°C in Ca2+-free solution. Cell suspensions were placed on the bottom of a 300-μl chamber mounted on an inverted microscope and allowed to adhere to the bottom of the chamber for 5 min before recording.

Patch-clamp experiments.

The whole-cell voltage-clamp technique was used to record membrane currents from dissociated HGCS cells. Currents were amplified with an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Data were digitized with 16-bit analog to digital converter (Digidata 1322A, Axon Instruments). Data were stored directly and digitized online by use of pClamp software (version 9.0, Axon Instruments). The data were sampled at 5 KHz with low-pass filter at 2 KHz by use of an eight-pole Bessel filter. Experiments were performed at room temperature (between 22 and 25°C).

Solutions and drugs.

In intracellular microelectrode recordings, the tissue chamber housing muscles was constantly perfused with oxygenated KRB solution of the following composition (in mmol/l): 120.4 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 15.5 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 11.5 glucose, 2.5 CaCl2. The pH of the KRB was 7.3–7.4 when bubbled with 97% O2-3% CO2 at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. To measure net outward currents, smooth muscle cells were bathed in a Ca2+-containing physiological salt solution (CaPSS) containing (in mmol/l) 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris. Cells were dialyzed with solution containing (in mmol/l) 135 KCl, 5 EGTA, 2 CaCl2, 0.1 Na2GTP, 3 MgATP, 10 glucose, 2.5 creatine phosphate disodium, and 10 HEPES and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris. Free Ca2+ concentration was 100 nM. In a Ca2+-free containing physiological salt solution (MnPSS), external CaCl2 was replaced with an equimolar MnCl2. To increase the driving force for K+ influx in human gastric smooth muscle cells, cells were perfuse in high K+-containing solution (HK, 135 mmol/l Na+ was replaced with equimolar K+) and the pipette solution contained (in mmol/l): 135 KCl, 10 BAPTA, 0.1 Na2GTP, 3 MgATP, 10 glucose, 2.5 creatine phosphate disodium, and 10 HEPES and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris. TEA, 4-AP, nicorandil (NCD), GBC, BaCl2, E-4031, ketoconazole, and ChTX were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TTX was purchased from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel), and apamin was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

Molecular studies.

Total RNA isolation, cDNA preparation, and amplification of HGCS strips (n = 3, circular muscle layer) were performed as previously reported (16). Briefly, RNA was prepared by using a SNAP Total RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (2 units) at 37°C (New England Biolabs) prior to cDNA preparation. First strand cDNA was synthesized from each RNA by using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase with 500 μg/μl of oligo(dT) primer cDNA. To investigate the transcriptional expression of K+ channels, the following PCR primers designed against human sequences were used (GenBank accession number is given in parenthesis for the reference nucleotide sequence used and common name): KCNA1 (NM_000217, Kv1.1), KCNA2 (NM_004974, Kv1.2), KCNA3 (NM_002232, Kv1.3), KCNA4 (NM_002233, Kv1.4), KCNA5 (NM_002234, Kv1.5), KCNA6 (NM_002235, Kv1.6), KCNA7 (NM_031886, Kv1.7), KCNB1 (NM_004975, Kv2.1), KCNB2 (NM_004770, Kv2.2), KCNV1 (NM_014379, Kv2.3), KCND1 (NM_004979, Kv4.1), KCND2 (NM_012281, Kv4.2), KCND3 (NM_004980, Kv4.3), KCNN1 (NM_002248, SK1), KCNN2 (NM_021614, SK2), KCNN3 (NM_002249, SK3), KCNN4 (NM_002250, SK4), KCNJ2 (NM_000891, Kir2.1), KCNJ3 (NM_002239, Kir3.1), KCNJ5 (NM_000890, Kir3.4), KCNJ6 (NM_002240, Kir3.2), KCNJ8 (NM_004982, Kir6.1), KCNJ9 (NM_004983, Kir3.3), and KCNJ11 (NM_000525, Kir6.2).

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as means ± SE. The paired Student's t-test was used where appropriate to evaluate differences in the data. P values less than 0.05 were taken as statistically significant differences. The number of recordings from muscle strips in microelectrode experiments and from cells in patch-clamp experiments is indicated by n.

RESULTS

Role of BK and Kv conductances in regulating the membrane excitability of HGCS.

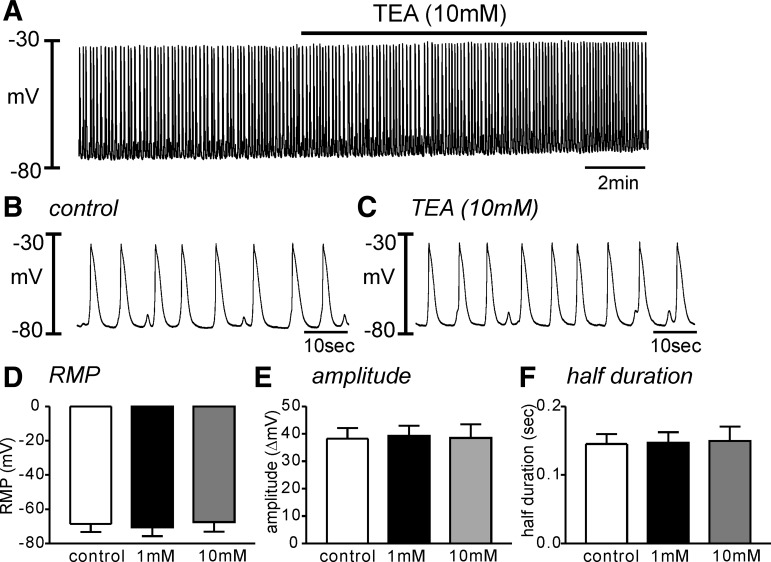

The role of K+ conductance(s) on membrane excitability of HGCS has not been reported. We tested the effect of TEA (1–10 mM) to examine the role of BK and Kv on electrical events in HGCS. The RMP in control tissue was −69 ± 5 mV. TEA application did not affect the RMP (−70 ± 5 mV in 1 mM n = 5, Fig. 1, A–D). High concentration of TEA (10 mM) did not affect the amplitude and duration of SWP (Fig. 1, E and F). Since high concentration of TEA can block Kv channels, we also tested the effect of ChTX, a specific blocker of BK and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, on the RMP. ChTX also did not show any significant effects on RMP (n = 4, data not shown). These data suggest that BK and TEA-sensitive Kv channels have a negligible role on the SWP.

Fig. 1.

Effect of tetraethylammonium (TEA) on the slow wave potential in human gastric corpus smooth muscles (HGCS). A: a representative trace shows that high concentration of TEA (10 mM) had no effect on the slow wave potentials in HGCS. B and C: expanded time scale from A in control (B) and TEA presence (C), respectively. D–F: summarized data show no significant changes in the resting membrane potential (RMP, D), slow wave amplitude (E), and half-duration of slow wave potentials (F) from 5 samples in each concentration of TEA.

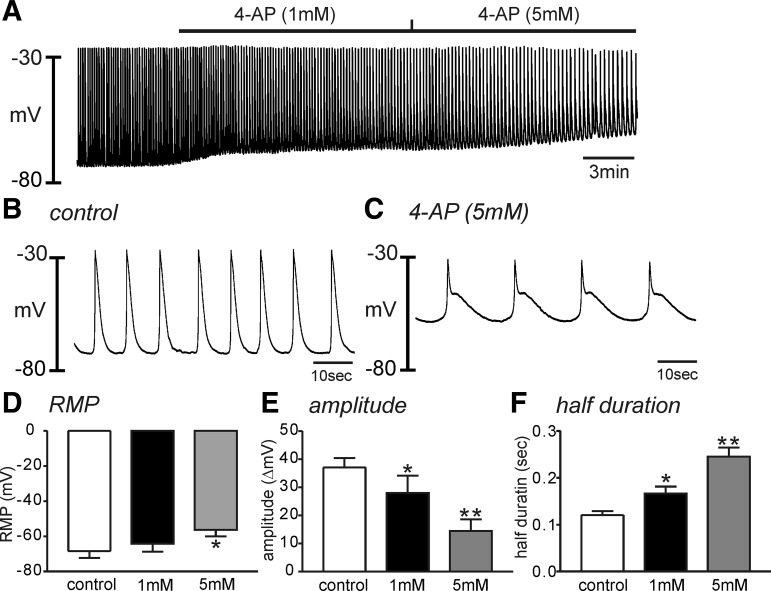

To examine the role of Kv channels on RMP, we tested the effects of 4-AP on electrical events in HGCS. 4-AP (1 mM) induced depolarization but not significantly (e.g., from −68 ± 4 mV to −64 ± 4 mV, P = 0.09, n = 5). Higher concentration of 4-AP (5 mM) depolarized HGCS, significantly (−56 ± 4 mV, P < 0.05 compared with control, n = 5, Fig. 2, A–D). 4-AP significantly decreased the amplitude of SWP (Fig. 2, A–C and E) and increased the half-duration of SWP from 0.12 ± 0.01 to 0.25 ± 0.02 s (P < 0.01, n = 5). These data suggest that 4-AP-sensitive Kv channels are involved in regulating RMP and membrane repolarization in HGCS.

Fig. 2.

Effect of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) on the slow wave potential in HGCS. A: a representative trace showed that low (1 mM) and high (5 mM) concentration of 4-AP depolarized HGCS with decreased slow wave amplitude and frequency. B and C: expanded time scale from A in control (B) and 4-AP (5 mM) presence (C), respectively. D–F: summarized data showed significant changes in the resting membrane potential (RMP, D), slow wave amplitude (E), and half duration of slow wave potentials (F) from 5 samples in each concentration of 4-AP. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Role of KATP conductance in regulating the membrane excitability of HGCS.

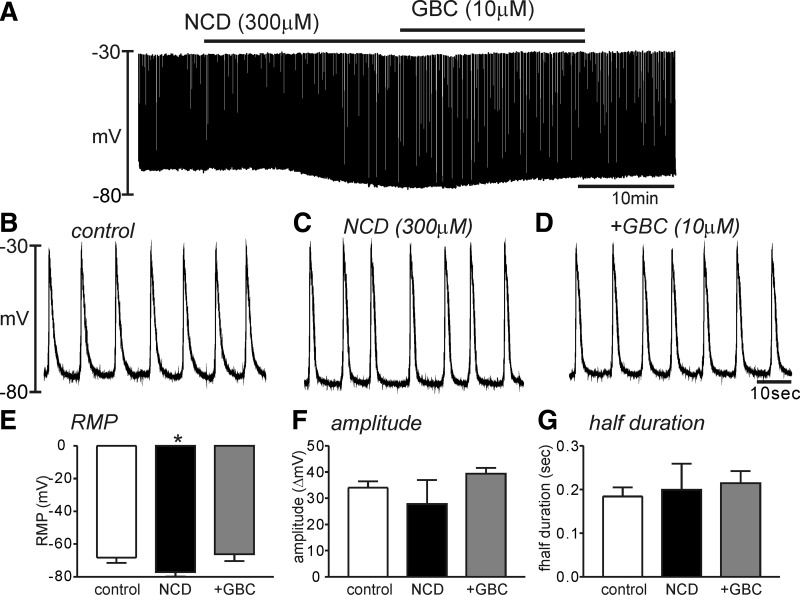

It has been suggested that basally activated KATP can be involved in regulating RMP (16). We tested the effect of a KATP blocker, GBC, on SWP in HGCS. GBC (10 μM) itself did not show any significant effect on the RMP (control; −67 ± 3 mV vs GBC; −66 ± 3 mV, n = 6). However, the KATP activator (NCD, 300 μM) hyperpolarized HGCS from −67 ± 2 mV to −77 ± 2 mV (P < 0.01, n = 6). Interestingly, NCD did not show significant effects on the half-duration of SWP (n = 5 Fig. 3, A, B, and G). Some tissues (2 of 5 samples) completely stop the slow wave. Thus the amplitude of SWP by NCD revealed the big standard error and showed no statistical significance (Fig. 3F). NCD-induced hyperpolarization was completely recovered to resting potential by GBC (10 μM) (n = 6, Fig. 3, A–G). The pretreatment of GBC also completely abolished the effect of NCD (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Effect of nicorandil (NCD) and glibenclamide (GBC) on the slow wave potential in HGCS. A: a representative trace showed that NCD (300 μM) induced hyperpolarization and continuous application of GBC (10 μM) abolished the NCD effect. B–D: expanded time scale from A in control (B), NCD presence (C), and both NCD and GBC presence (D), respectively. E–G: summarized data showed significant changes in the resting membrane potential (RMP, E) but no significance on the slow wave amplitude (F) and slow wave duration (G) from 6 samples in the presence of NCD and NCD+GBC. *P < 0.05.

Role of SK conductance in regulating the membrane excitability of HGCS.

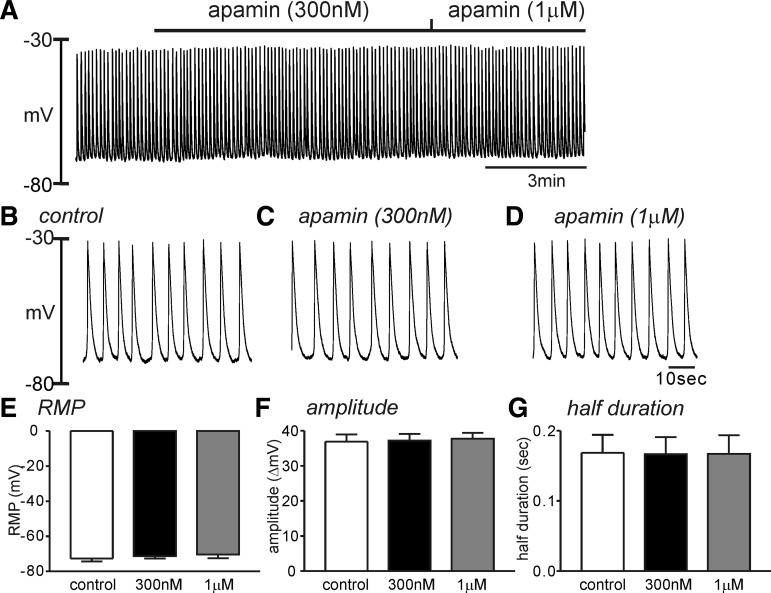

Apamin, a SK channel blocker, is known to induce depolarization in various regions of gastrointestinal smooth muscles (19). However, it has also been reported that apamin had no effect on the RMP in guinea pig antrum (19). The effect of apamin in HGCS has not been studied. Apamin (300 nM–1 μM, n = 5 each concentration) did not affect the RMP, amplitude, and frequency of SWP in HGCS (Fig. 4), suggesting that the basal activation of SK channels in regulating RMP is negligible.

Fig. 4.

Effect of apamin on the slow wave potential in HGCS. A: a representative trace showed that apamin (300 nM and 1 μM) had no effect on the slow wave potentials in HGCS. B–D: expanded time scale from A in control (B), apamin (300 nM) presence (C), and apamin (1 μM) presence (D), respectively. E–G: summarized data showed no significant changes in the resting membrane potential (RMP, E) but no significance on the slow wave amplitude (F) and half-duration of slow wave potentials (G) from 5 samples in each concentration.

Role of Kir conductance in regulating the membrane excitability of HGCS.

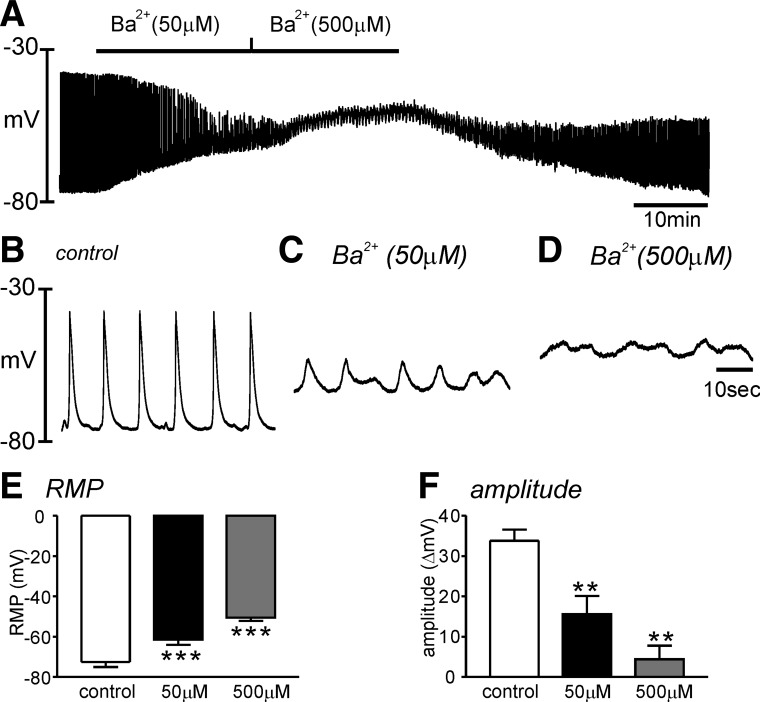

Kir can be blocked by low concentration of Ba2+ (6, 19). Bath application of Ba2+ (50 μM) depolarized HGCS from −72 ± 3 mV to −61 ± 3 mV (P < 0.001, n = 5, Fig. 5, A–C). A higher concentration Ba2+ (500 μM) induced strong depolarization of HGCS to −51 ± 2 mV (P < 0.001, n = 5, Fig. 5, A and E). Ba2+ also significantly decreased the amplitude (Fig. 5F) of SWP. Ba2+ (500 μM, n = 3 of 5 experiments) completely abolished SWP with strong depolarization. Therefore, we could not analyze the effect of Ba2+ on the duration of SWP. These data suggest that Kir channels are involved in regulating RMP of HGCS.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Ba2+ on the slow wave potential in HGCS. A: a representative trace showed that Ba2+ (50–500 μM) significantly depolarized HGCS. B–D: expanded time scale from A in control (B), low concentration of Ba2+ (50 μM) (C), and high concentration of Ba2+ (500 μM) (D), respectively. E and F: summarized data showed significant changes in the resting membrane potential (RMP, E) and the slow wave amplitude (F) from 5 samples in each concentration. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Role of HERG conductance in regulating membrane excitability in HGCS.

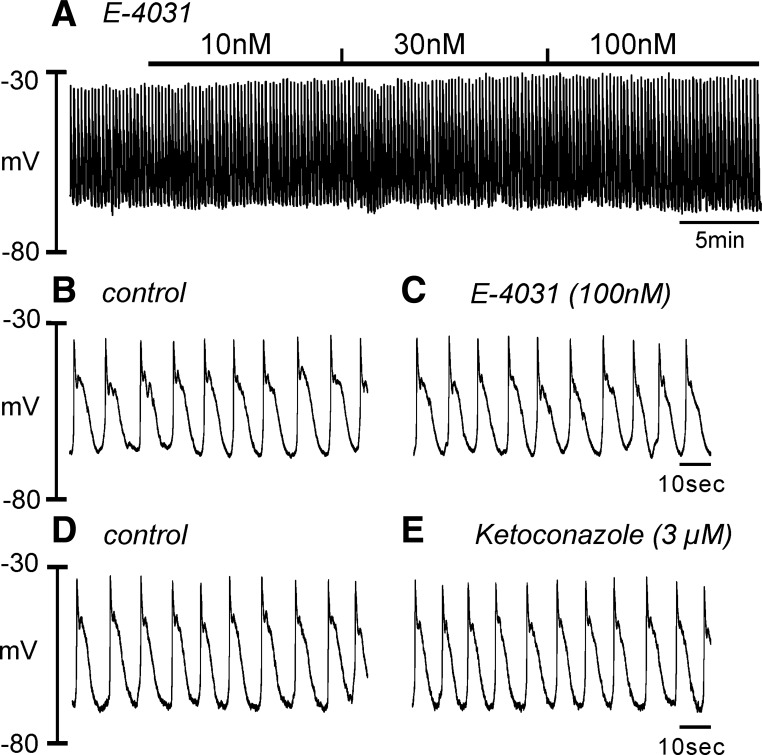

The functional role of HERG channels in RMP regulation was also tested. The compound E-4031 (10 nM–1 μM), a HERG channel blocker, did not affect the RMP, amplitude, and half-duration of slow wave (n = 4, Fig. 6, A–C). Ketoconazole (3 μM, n = 4), another HERG channel blocker, also did not show significant changes in RMP (Fig. 6, D and E). However, a high concentration (30 μM) of ketoconazole depolarized HGCS. This might be due to nonspecific blocking of ketoconazole on other K+ conductances.

Fig. 6.

Effect of E-4031 and ketoconazole on the slow wave potential in HGCS. A: a representative trace showed that E-4031 (10 nM–1 μM) had no effect on the slow wave potentials in HGCS. B and C: expanded time scale from A in control (B) and after E-4031 (100 nM) (C). D and E: representative traces showed no effect of ketoconazole (3 μM) before (D) and after (E).

Current isolation of Kv and Kir conductance in isolated smooth muscle cells of HGCS.

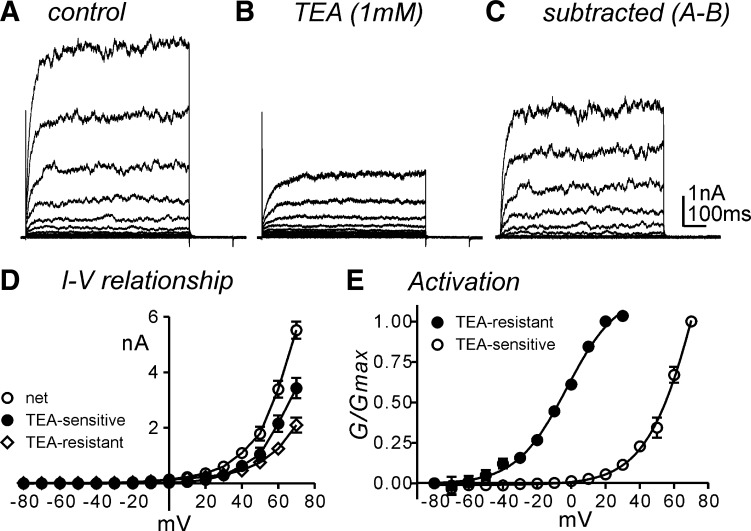

To examine the characteristics of net outward currents, isolated smooth muscle cells were exposed to CaPSS (see methods) and dialyzed with K+-rich solution (intracellular Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i; 100 nM). Cells were held at −80 mV and depolarized to +70 mV with 10-mV increments (Fig. 7, A and D). TEA (1 mM, n = 5) or ChTx (200 nM, n = 3 data not shown) to inhibit BK channels decreased the outward currents and remained TEA-resistant currents (Fig. 7, B and D). TEA-resistant currents showed a classical property of delayed rectifying K+ currents without voltage-dependent inactivation within a 700-ms depolarization period. TEA-sensitive currents (mainly BK currents, Fig. 7, C and D) were constructed by subtraction from control (Fig. 7A) to TEA-resistant (Fig. 7B) currents. TEA-sensitive and TEA-resistant currents showed voltage-dependence with a half activation voltage of +73 ± 3 mV and −3 ± 0.7 mV, respectively (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Characteristics of the outward currents in isolated human gastric corpus smooth muscle cells. A: a representative trace showed outward currents during step depolarization up to +70 mV in 10 mV increment from a holding potential of −80 mV. Cells were exposed to Ca2+-containing physiological solution (CaPSS) externally and dialyzed with K+-rich solution (100 nM intracellular Ca2+ concentration) internally. B: TEA (1 mM) decreased outward currents and remained the delayed rectifying K+ currents (TEA-resistant). C: subtracted currents from A to B showed TEA-sensitive currents (mainly BK). D: summarized current-voltage (I–V) relationship of the net outward (control, ○) and BK (TEA-sensitive, ●) and delayed rectifying K+ (TEA-resistant, ◇) currents. E: voltage-dependent activation from TEA-resistant (●) and TEA-sensitive (○) currents. Boltzmann equation was applied to calculate half activation in normalized with maximal conductance (G/Gmax).

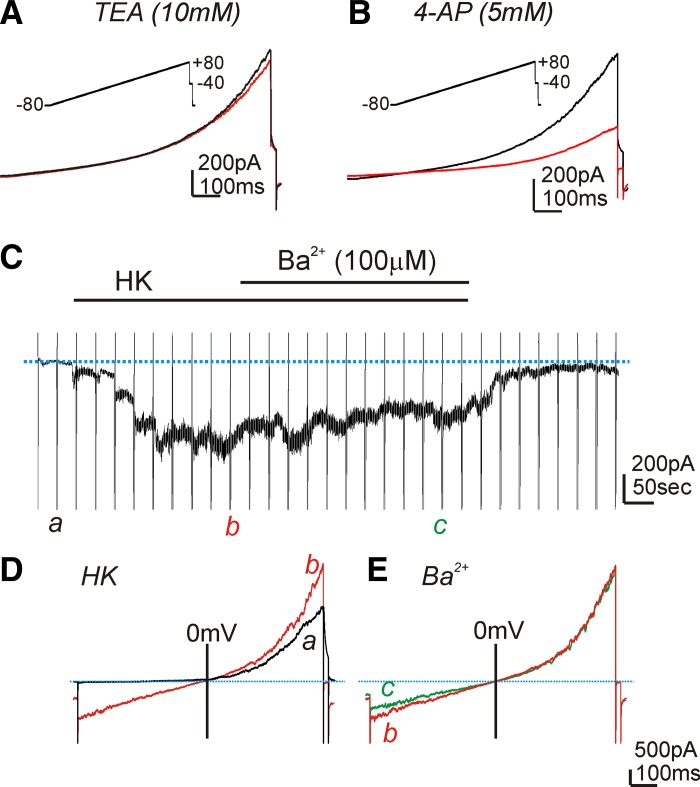

Since the most prominent findings by microelectrode recordings in HGCS are 4-AP and Ba2+ sensitive, we performed patch-clamp experiments to characterize the 4-AP and Ba2+-sensitive currents from isolated smooth muscle cells of the HGCS. Whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques were employed. The external solution was MnPSS (see methods) with dialyzed K+-rich solution (10 mM BAPTA to prevent the contamination of Ca2+-activated K+ currents; see methods). Ramp depolarization to +80 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV was applied (see insets in Fig. 8, A and B). A high concentration of TEA (10 mM) had no effect on the evoked currents (Fig. 8A, n = 5), but 4-AP (5 mM) inhibited outward currents from 158 ± 12 pA to 68 ± 6 pA at 0 mV (Fig. 7B, P < 0.01, n = 6). These data suggest that HGCS smooth muscle cells express 4-AP-sensitive Kv currents.

Fig. 8.

Effect of TEA, 4-AP, and Ba2+ on the outward currents in isolated HGCS cells. A and B: a representative trace showed outward currents during ramp depolarization (from −80 to +80 mV; see inset) from a holding potential of −80 mV. TEA (10 mM) did not show significant effect on evoked outward currents (A). However, 4-AP (5 mM) decreased the outward currents (B). C: a representative trace showed the effect of Ba2+ (100 μM) after replacement with K+-rich solution (HK; see methods) at −80 mV. Vertical lines denote ramp depolarization and blue dotted line denotes the holding current at −80 mV. D: a (black line) and b (red line) are evoked currents during ramp depolarization from C in control and HK presence, respectively. E: bath application of Ba2+ (100 μM, c: green line) under external K+-rich solution (b: red line) at a holding potential of −80 mV did not reveal significant effect on ramp-evoked currents.

To examine the functional expression of Kir channels in isolated smooth muscle cells, we changed the external solution from MnPSS to HK (140 mM; see methods) to increase the driving force of K+ at the negative potentials. The replacement of the external solution from MnPSS to HK activated inward currents (−335 ± 36 pA) at a holding potential of −80 mV (see Fig. 8C). Ramp depolarization evoked huge inward currents in HK compared with MnPSS at the negative potentials (Fig. 8D). The addition of Ba2+ (100 μM) minimally inhibited the inward currents (−305 ± 46 pA at −80 mV, Fig. 8, C and E, n = 5). These data suggest that Kir conductance of HGCS smooth muscle cells may not have a functional role in setting RMP.

Taken together, the effects of 4-AP on membrane potentials could be due to Kv channels in smooth muscle cells but Ba2+-induced depolarization in tissue is not due to expression of Kir channels in smooth muscle cells.

Molecular expression of K channels in HGCS.

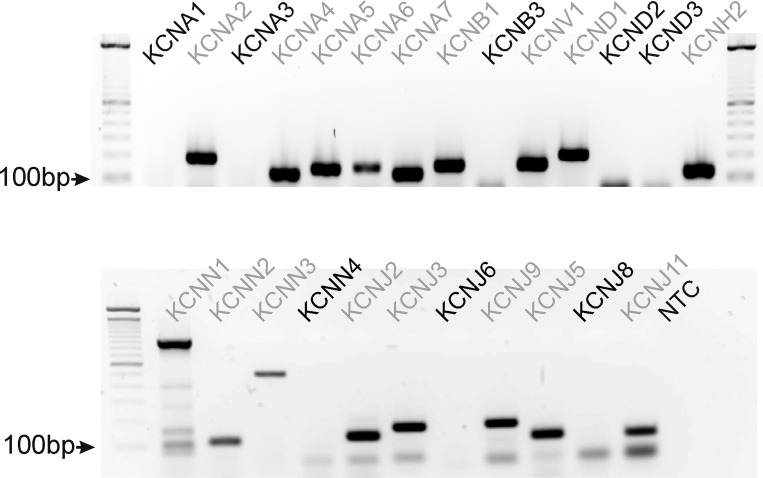

To examine transcriptional expression of K+ channels in HGCS, we performed RT-PCR analysis (see Table 1 for the specific primers). KCNNA2, 4, 5, 7, KBNB1, and KCNV1, Kv molecular candidates, were detected in HGCS. KCNJ2 but not KCNJ1, KATP candidates, was expressed. All KCNN1–3, SK channel candidates, but not KCNN4, an intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel candidate, were detected. KCNJ2, 3, 5, 9, and KCNH2 were also expressed in HGCS (Fig. 9).

Table 1.

Primer sequence of tested genes

| Gene Name | Primer Sequence | Gene Name | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNCA1 | TGATGTCTGGGGAGAACGTG | KCNH2 | CACACATGGACTCACGCATC |

| GCAGCCCGGAGATGTTGAT | TAGAGCGCCGTCACATACTT | ||

| KCNA2 | CATGAGAGAATTGGGCCTCC | KCNN1 | TCGGGGAAACCCTCAAATGT |

| CCCCCAATGGTAGTCGGAAC | GCCAATGGAGAGGAAGGTGA | ||

| KCNA3 | GCGACGAGAAGGACTACCC | KCNN2 | TCGAAAAGCGCAAGCGGCTC |

| GCTAGGACAAGCGAAGAACC | AGCGACGCCTTGTCGTAGGC | ||

| KCNA4 | TACCTCCCATGACCCTCAGA | KCNN3 | ACCAAGCGGATCAAGAATGC |

| GGCATCAGGTCAGAGCAATG | ATGGGGCTATCGGAGATTGG | ||

| KCNA5 | TGTTCGCGGACGAGATACG | KCNN4 | GCCTTGAGACGCCGAAAGCG |

| ACTCGAAGATAAGCCACACCT | CAGGTAGAGCGCCCACGAGC | ||

| KCNA6 | TTTGCCTGGAGACCTTACCC | KCNJ2 | GCTCATGTGTAGTGTGCGAG |

| AGGGGTGATGCCATGATGAA | GAGAATGCCAGGATGCCAAG | ||

| KCNA7 | CCGGACACTCTGCTAGGGG | KCNJ3 | GCTACCTCTCGGACCTCTTC |

| GACTGGTAGTAGTAGAGCACGG | TAGTTACCGACGTGGGCTTT | ||

| KCNB1 | CCAGTGGTCAGGAAAAGTGC | KCNJ6 | GACAGAATCCATGACTAACGTCC |

| ACAGCTCTCCTCTTTGGACC | TCCGTCTTTCCTCACGTACC | ||

| KCNB2 | CATCAGTGGCTGCAAAGATCC | KCNJ9 | ATGGACTTTTGGGGGTTGGA |

| GTGCTAATTGGCGGTTGTCA | TGGTTTGGGGCTGTATCTGT | ||

| KCNV1 | ACAGCGTGAAGCCCTAAAGA | KCNJ5 | GCACATGCATAGTGGCATCA |

| ACCAGAAATCATCTCCCCCG | TCTTGGGCCAAAAAGCACTC | ||

| KCND1 | CCTGTGCCAGTCATTGTGTC | KCNJ8 | TGGCTGCTCTTCGCTATCAT |

| TTTGCCAATCGGATCCTTGC | AGCAGAAGTGAAAGACCTGAC | ||

| KCND2 | GTTAGCAAATCCGGCTCCAG | KCNJ11 | TCCAAGAAAGGCAACTGCAAC |

| TGCAACTTCCATGCAGCTTT | AAGATGAGCAATGTGTGTGGC | ||

| KCND3 | ACCTCCACCATCAAGAACCA | ||

| GCTGGCAGGTTAGAATTGGG |

Fig. 9.

Transcriptional expression of K+ channels in HGCS. Representative agarose end-point gel of RT-PCR products revealed K+ channels expression in HGCS. Light gray font denotes the detected isoforms of tested K+ channel transcripts.

DISCUSSION

The generation of slow waves by ICC is well established (25, 27, 28, 30). The RMP in gastrointestinal muscle can be regulated by electrically coupled conductances in SIP (Smooth muscle cells, ICC and PDGFRà+ cells) syncytium (smooth muscle cells; ICC and PDGFRα+ cells) (19, 28). A small depolarization from RMP activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and affects contractility. Although the electrical activity was recorded in the human stomach (4, 7, 25), the role of basally activated K+ conductances to regulate RMP in HGCS has not been studied. In the present study, we elucidate the role of K+ conductances, which regulate RMP in HGCS. This is only the first study to investigate the role of K+ channels in the electrical activity of human gastric muscles.

Role of Kv channels in HGCS.

Smooth muscle excitability in HGCS can be regulated by enteric nervous system (31). We used TTX, a Na+ channel blocker, throughout experiments to exclude neural influences. It has been suggested that TTX augmented spontaneous colonic contractility through blocking tonic inhibitory enteric motor influence (14). However, in HGCS, TTX did not display any significant effects on spontaneous SWP. These data suggest that inhibitory neurotransmitters are not dominating factors in ongoing membrane excitability of HGCS. Basally activated BK channels can affect the setting of the RMP. In the present study, BK channel blockers, ChTX, or a low concentration of TEA (1 mM) did not affect the RMP or SWP patterns in HGCS. Furthermore, in patch-clamp experiments, TEA- or ChTX-sensitive currents were activated at the positive potentials in intracellular 100 nM free [Ca2+]i condition. These data suggest that BK channels might have a negligible role on membrane excitability in HGCS.

Kv channels are known to regulate membrane excitability in colonic smooth muscles (19). Kv channels can be blocked by high concentrations of TEA (up to 10 mM) and 4-AP (5 mM). High concentration of TEA (10 mM) did not affect SWP but 4-AP induced depolarization with an increase in the duration of SWP of HGCS. These data suggest that 4-AP-sensitive Kv channels might be expressed in HGCS. The transcriptional expression of KCNA2 (Kv1.2), KCNA4 (Kv1.4), KCNA5 (Kv1.5), KCNA7 (Kv1.7), KCNB1 (Kv2.1), and KCND1 (Kv4.1) was detected in HGCS. KCNA4 and KCND1 revealed the fast inactivation during depolarization (24, 32). In the present study, low concentration of TEA (1 mM) inhibited BK channels, and there remained Kv (TEA-resistant) currents that showed a negligible inactivation property during 700-ms depolarization. KCNB1 is very sensitive to TEA (8, 12). Under MnPSS with BAPTA dialysis (see methods) to exclude the contamination of BK currents, TEA (10 mM) did not show a significant effect on Kv currents. In addition, there is no report about the effect of 4-AP or TEA on KCNA7. In smooth muscles of many animal models, TEA-sensitive currents are available and have potent impact on the electrical activity. This appears not to be true for human gastric muscles. 4-AP-sensitive currents appear to be important in human muscles both for setting membrane potential and for determining the duration of slow wave events. Thus KCNA2 and KCNA5 could be molecular candidates for 4-AP-sensitive Kv channels in smooth muscle cells. Taken together, Kv channels in smooth muscle cells of the HGCS could be the main K+ conductances in regulating RMP and SWP.

Role of SK and KATP channels in HGCS.

Apamin is a selective blocker for SK channels (1). SK channels are voltage independent and sensitive to intracellular Ca2+. SK channels are expressed in gastrointestinal smooth muscle (15). The effect of apamin on the RMP is not consistent depending on the species and tissues. For instance, colonic smooth muscles are depolarized by apamin (19) but guinea pig antrum is not sensitive to apamin (20). In the present study, we did not find the effect of apamin on the RMP of HGCS, suggesting that SK channels are not basally active. In murine colonic smooth muscle cells, SK2 (Kcnn2) is a dominant isoform (15, 26). In recent reports, PDGFRα+ cells highly express SK3 (Kcnn3) and involves purine-mediated inhibitory junction potentials (11, 22, 34). In HGCS, KCNN1 (SK1, KCa2.1), KCNN2 (SK2, KCa2.2), and KCNN3 (SK3, KCa2.3) genes were detected. We cannot exclude whether these channels are involved in purinergic inhibitory junction potentials since we did not test the responses by electrical field stimulation.

The functional expression of KATP channels can be tested by KATP channel openers (lemakalin, pinacidil, cromakalim, NCD, etc.) and the KATP channel blocker GBC (19, 23). GBC depolarized murine colonic smooth muscle, suggesting that KATP was basally activated and involved in setting RMP (16). We found that NCD induced hyperpolarization and GBC blocked these effects. However, GBC itself did not cause depolarization. Thus KATP is functionally expressed but does not regulate the RMP, suggesting that KATP is not basally activated. KCNJ8 (Kir6.1) and KCNJ11 (Kir6.2) are pore-forming subunits of KATP channels (13, 16). RT-PCR detects only Kir 6.2 transcript in HGCS. We did not examine the expression of sulfonylurea receptors (SUR1 and SUR2B) for this study.

Role of Kir and HERG channels in HGCS.

Kir conductances have a property of outward current around K+ equilibrium potential (EK) and thus expression of this conductance contributes in regulating RMP (19). Low concentration of Ba2+ (μM range) has been used to investigate the functional expression of Kir channels (19). In a previous report, Ba2+ (1–100 μM) depolarized cells along the submucosal surface of the circular muscle layer in canine colonic muscles (6). When the submucosal and myenteric pacemaker regions were surgically removed, higher concentrations of Ba2+ were required to depolarize circular muscle. These data suggested that a higher current density of Ba2+-sensitive Kir conductance was expressed in ICC but not in smooth muscle cells (6). In the present study, Ba2+ (50–500 μM) significantly depolarized HGCS. Patch-clamp data in smooth muscle cells revealed negligible effect of Ba2+. RT-PCR showed expression of KCNJ2 (Kir2.1) mRNA in HGCS. These data support that ICC may express Ba2+-sensitive Kir2.1 channels, which are involved in setting the RMP. The importance of a Ba2+-sensitive conductance in human gastric electrophysiology has not been recognized previously. We believe this is mechanistic insight into how electrical rhythmicity powers (phasic) peristaltic contractions in the human stomach. If the Ba2+-sensitive conductance is not available, depolarization occurs, slow waves are blocked or greatly reduced in amplitude, there is no mechanism for slow wave propagation, and there is no repolarization period between the remaining small slow waves for relaxation to occur. Contraction, in the absence of the Ba2+-sensitive conductance, would tend not to be propagating and peristaltic in nature, thus not productive for gastric emptying.

Interestingly, KCNJ3 (Kir3.1) and KCNJ6 (Kir3.2) transcripts [G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels, (GIRK)] were also detected in canine colonic smooth muscle and expression of both proteins was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (2). However, the functional role of GIRK channels has not been demonstrated in gastrointestinal tissues. We believe that the transcriptional expression of GIRK may be expressed in neuron or interstitial cells. The functional expression of KCNH2 (HERG) in the human jejunum has been reported (5). In human jejunum, a low concentration of E-4031 (10 nM) increased the number of spikes per slow wave and a high concentration (1 μM) induced depolarization. In the present study, we did not find a significant change of the RMP (up to 1 μM of E-4031 and 3 μM of ketoconazole) in HGCS. These data suggest that the transcriptional expression of KCNH2 is not expressed in the muscle layer even though KCNH2 transcript was detected in HGCS tissue.

In conclusion, Kir and Kv channels are main K+ conductances to set RMP in HGCS. Development of isolation technique of ICC and PDGFRα+ cell in HGCS is required to confirm molecular and functional expression of K+ conductances at the cellular level.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Samsung Biomedical Research Institute Grant C-B1-125.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Y.L. and P.-L.R. conception and design of research; J.Y.L., E.-J.K., K.D.A., and S.K. performed experiments; J.Y.L. and P.-L.R. analyzed data; J.Y.L., E.-J.K., and P.-L.R. interpreted results of experiments; J.Y.L. prepared figures; J.Y.L., E.-J.K., and P.-L.R. drafted manuscript; J.Y.L. and P.-L.R. edited and revised manuscript; S.K. and P.-L.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jae-Moon Bae, Tae-Sung Sohn, Min-Gew Choi, and Jun-Ho Lee for providing surgical tissues.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blatz AL, Magleby KL. Single apamin-blocked Ca-activated K+ channels of small conductance in cultured rat skeletal muscle. Nature 323: 718–720, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley KK, Hatton WJ, Mason HS, Walker RL, Flynn ER, Kenyon JL, Horowitz B. Kir3.1/3.2 encodes an IKACh-like current in gastrointestinal myocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278: G289–G296, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwyer L, Rhee PL, Lowe V, Zheng H, Peri L, Ro S, Sanders KM, Koh SD. Basally activated nonselective cation currents regulate the resting membrane potential in human and monkey colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G287–G296, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Sharkaway TY, Morgan KG, Szurszewsky JH. Intracellular electrical activity of canine and human gastric smooth muscle. J Physiol 279: 291–307, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrelly AM, Ro S, Callaghan BP, Khoyi MA, Fleming N, Horowitz B, Sanders KM, Keef KD. Expression and function of KCNH2 (HERG) in the human jejunum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G883–G895, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn ER, McManus CA, Bradley KK, Koh SD, Hegarty TM, Horowitz B, Sanders KM. Inward rectifier potassium conductance regulates membrane potential of canine colonic smooth muscle. J Physiol 518: 247–256, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara Y, Ito Y. The electrical activity recorded from smooth muscle of the circular layer of the human stomach. Pflügers Arch 382: 145–153, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Kang Y, Leung YM, Xia F, Gao X, Xie H, Gaisano HY, Tsushima RG. Modulation of Kv2.1 channel gating and TEA sensitivity by distinct domains of SNAP-25. Biochem J 396: 363–369, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirst GD, Beckett EA, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Regional variation in contribution of myenteric and intramuscular interstitial cells of Cajal to generation of slow waves in mouse gastric antrum. J Physiol 540: 1003–1012, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirst GD, Edwards FR. Role of interstitial cells of Cajal in the control of gastric motility. J Pharm Sci 96: 1–10, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iino S, Horiguchi K, Horiguchi S, Nojyo Y. c-Kit-negative fibroblast-like cells express platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha in the murine gastrointestinal musculature. Histochem Cell Biol 131: 691–702, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Immke D, Wood M, Kiss L, Korn SJ. Potassium-dependent changes in the conformation of the Kv2.1 potassium channel pore. J Gen Physiol 113: 819–836, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin X, Malykhina AP, Lupu F, Akbarali HI. Altered gene expression and increased bursting activity of colonic smooth muscle ATP-sensitive K+ channels in experimental colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G274–G285, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Dwyer L, Song JH, Martin-Cano FE, Bahney J, Peri L, Britton FC, Sanders KM, Koh SD. Identification of histamine receptors and effects of histamine on murine and simian colonic excitability. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23: 949–e409, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klemm MF, Lang RJ. Distribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK2 and SK3) immunoreactivity in intestinal smooth muscles of the guinea-pig. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29: 18–25, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh SD, Bradley KK, Rae MG, Keef KD, Horowitz B, Sanders KM. Basal activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in murine colonic smooth muscle cell. Biophys J 75: 1793–1800, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh SD, Perrino BA, Hatton WJ, Kenyon JL, Sanders KM. Novel regulation of the A-type K+ current in murine proximal colon by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Physiol 517: 75–84, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh SD, Ward SM, Dick GM, Epperson A, Bonner HP, Sanders KM, Horowitz B, Kenyon JL. Contribution of delayed rectifier potassium currents to the electrical activity of murine colonic smooth muscle. J Physiol 515: 475–487, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh SD, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Ionic conductances regulating the excitability of colonic smooth muscles. Neurogastroenterol Motil 24: 705–718, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komori K, Suzuki H. Distribution and properties of excitatory and inhibitory junction potentials in circular muscle of the guinea-pig stomach. J Physiol 370: 339–355, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong ID, Koh SD, Bayguinov O, Sanders KM. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels are regulated by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in murine colonic myocytes. J Physiol 524: 331–337, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurahashi M, Zheng H, Dwyer L, Ward SM, Koh SD, Sanders KM. A functional role for the ‘fibroblast-like cells’ in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. J Physiol 589: 697–710, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pluja L, Yokoshiki H, Sperelakis N. Evidence for presence of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in rat colonic smooth muscle cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 76: 1166–1170, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmusson RL, Zhang Y, Campbell DL, Comer MB, Castellino RC, Liu S, Strauss HC. Bi-stable block by 4-aminopyridine of a transient K+ channel (Kv1.4) cloned from ferret ventricle and expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol 485: 59–71, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee PL, Lee JY, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Kim S, Koh SD, Hwang SJ, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Analysis of pacemaker activity in the human stomach. J Physiol 589: 6105–6118, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ro S, Hatton WJ, Koh SD, Horowitz B. Molecular properties of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels expressed in murine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G964–G973, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders KM, Koh SD, Ordog T, Ward SM. Ionic conductances involved in generation and propagation of electrical slow waves in phasic gastrointestinal muscles. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16, Suppl 1: 100–105, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders KM, Koh SD, Ro S, Ward SM. Regulation of gastrointestinal motility—insights from smooth muscle biology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 633–645, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders KM, Ordog T, Ward SM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the interstitial cells of Cajal: from bench to bedside. IV. Genetic and animal models of GI motility disorders caused by loss of interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G747–G756, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders KM, Zhu MH, Britton F, Koh SD, Ward SM. Anoctamins and gastrointestinal smooth muscle excitability. Exp Physiol 97: 200–206, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schemann M. Control of gastrointestinal motility by the “gut brain”—the enteric nervous system. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 41, Suppl 1: S4–S6, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng GN, Jiang M, Yao JA. Reverse use dependence of Kv4.2 blockade by 4-aminopyridine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279: 865–876, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Helden DF, Laver DR, Holdsworth J, Imtiaz MS. Generation and propagation of gastric slow waves. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37: 516–524, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderwinden JM, Rumessen JJ, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A Jr, Gillard K, Panthier JJ, de Laet MH, Schiffmann SN. Kit-negative fibroblast-like cells expressing SK3, a Ca2+-activated K+ channel, in the gut musculature in health and disease. Cell Tissue Res 310: 349–358, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]