Abstract

Objectives. We aimed to identify problem drinking trajectories and their predictors among Asian Americans transitioning from adolescence to adulthood. We considered cultural and socioeconomic contextual factors, specifically ethnic drinking cultures, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and neighborhood coethnic density, to identify subgroups at high risk for developing problematic drinking trajectories.

Methods. We used a sample of 1333 Asian Americans from 4 waves of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (1994–2008) in growth mixture models to identify trajectory classes of frequent heavy episodic drinking and drunkenness. We fitted multinomial logistic regression models to identify predictors of trajectory class membership.

Results. Two dimensions of ethnic drinking culture—drinking prevalence and detrimental drinking pattern in the country of origin—were predictive of problematic heavy episodic drinking and drunkenness trajectories. Higher neighborhood socioeconomic status in adolescence was predictive of the trajectory class indicating increasing frequency of drunkenness. Neighborhood coethnic density was not predictive of trajectory class membership.

Conclusions. Drinking cultures in the country of origin may have enduring effects on drinking among Asian Americans. Further research on ethnic drinking cultures in the United States is warranted for prevention and intervention.

Alcohol use disorders among Asian American young adults are important public health concerns. Although drinking prevalence is low for Asian Americans overall,1 Asian American young adults, particularly those in some ethnic groups such as Korean and Japanese, have higher rates of alcohol abuse and dependence than most other racial groups and other Asian ethnic groups such as Chinese.1–6 Asian Americans, including adolescents and young adults, are an underinvestigated population in alcohol research. Much of the small body of alcohol research, with college samples of mostly Korean and Chinese descent, has focused on genes involved in alcohol metabolism2,3,5,7,8 and the psychosocial moderators or mediators of their effects.2,9,10 Longitudinal studies on developmental trajectories of Asian American drinking are particularly rare.

Past research indicates that alcohol consumption tends to escalate after high school in emerging adulthood (ages 18–25 years)11 and then begins to decline.12–14 Although problem drinking during emerging adulthood in itself is an important public health concern,15,16 continued or escalating problem drinking beyond this period is of even greater concern because of potential long-term health and social consequences. We aimed to identify developmental trajectories of problem drinking among Asian Americans transitioning from adolescence to adulthood that will help distinguish normative and problematic long-term drinking patterns. We also identified predictors of problematic drinking trajectories, with special attention to contextual factors concerning the broader cultural and socioeconomic environments of drinking, as these have received little research attention in this understudied population.

Our investigation of ethnic drinking cultures addressed some of the documented limitations of acculturation research, including the common presumption that alcohol consumption and other risky health behaviors following an immigrant’s arrival in the United States are largely attributable to the influence of US culture,17 little understanding of ethnic cultures that may influence these behaviors,18 and the use of acculturation measures without clear bearings on the specific health issue at hand,19 which makes it difficult to elucidate the specific mechanisms through which acculturation influences health behaviors.20 In our view, the lack of understanding of the conditions within immigrant communities, along with preoccupation with how immigrant communities respond to US culture outside their communities, is critical.21 The approach we take here puts the focus squarely back on the cultural conditions within immigrant communities that specifically concern drinking—namely, ethnic drinking cultures, defined as cultural norms and behavioral practices of drinking in an immigrant’s country of origin.22 Our approach was informed by transnationalism theories, which suggest that immigrants often maintain socioeconomic ties with their homelands and retain elements of their cultural heritage, some of which may also appeal to their US-born descendants.23,24 In the context of drinking, transnationalism theories suggest that ethnic drinking culture from the country of origin may have enduring influence on immigrants and their children.

A focus on ethnic drinking cultures has other significance in current research on immigrant health. Heterogeneity in drinking and other health outcomes across ethnic or national groups has been highlighted in recent research,25–27 which has used ethnicity as an implicit proxy of underlying yet undefined cultural or socioeconomic conditions that are assumed to vary across ethnic groups. Yet efforts to clarify the underlying conditions that may lead to diverse outcomes have been lacking.22 The 2 dimensions of ethnic drinking cultures used in this study, drinking prevalence and detrimental drinking pattern, express in quantifiable terms drinking-related cultural conditions that may explain the diverse drinking outcomes across Asian American subgroups. In our pioneering cross-sectional studies, we found robust associations of these dimensions with alcohol consumption among Asian American adults28 and young adults.22 Building on this research, in this longitudinal study, we examined the influence of ethnic drinking cultures on developmental trajectories of problem drinking among Asian Americans transitioning to adulthood in an effort to demonstrate their effects more conclusively.

We also considered 2 neighborhood contextual factors as predictors of drinking trajectories, socioeconomic status (SES) and coethnic density. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage may lead to problem drinking through several mechanisms including stress associated with a high level of poverty and often-accompanying social disorganization,29,30 a lack of social control on deviant behaviors associated with weaker community ties in disadvantaged neighborhoods,31,32 and increased density of bars and liquor stores in lower-income areas.33,34 Studies of effects of neighborhood disadvantage on substance use outcomes are decidedly mixed, as studies show less of an effect, or even an inverse association, of neighborhood disadvantage with adolescent substance use compared with adult substance use.35 Most adolescent substance users are in an experimental stage, and problematic trajectories of use are not evident until early adulthood, which is one impetus for the current study. Neighborhood coethnic density has been found to have protective buffering effects on health and health behaviors, including drinking,36 attributed to enhanced social cohesion, mutual social support, and a stronger sense of community and belongingness.37–41 Little research has been reported on the influence of these contextual factors on alcohol use over time among Asian American adolescents and young adults.

Summarily stated, we addressed the following specific research question in this study: do ethnic drinking cultures, neighborhood SES, and neighborhood coethnic density predict problematic drinking trajectories for Asian Americans transitioning from adolescence to adulthood? We controlled for several key individual-level predictors of alcohol use during adolescence in our multivariate models—namely, US nativity, individual-level SES, age of drinking initiation, attachment to mother, and peer drinking in adolescence. This research helps identify specific profiles of subgroups at high risk for developing problematic, long-term patterns of drinking to guide prevention and intervention efforts targeted at the subgroups most likely to benefit. This is of great practical significance given the wide diversity among Asian Americans, both cultural42 and socioeconomic.43,44

METHODS

We extracted a sample of 1333 Asian Americans from the ongoing National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health is a nationally representative sample of adolescents who were in grades 7 through 12 during the 1994–1995 school year. In a multistage stratified cluster design, school samples were selected; an additional in-home sample was selected from the school sample and followed into adulthood. We used in-home survey data from all 4 waves, with response rates of 78.9% in wave 1, 88.2% in wave 2 (administered in 1996), 77.4% in wave 3 (2001–2002), and 80.3% in wave 4 (2007–2008). Further details on Add Health are provided elsewhere.45

Measures

Drinking outcomes.

We used 2 drinking outcomes measured in all 4 survey waves: frequency of heavy episodic drinking (HED; also called binge drinking) and frequency of drunkenness. We assessed HED frequency by the number of days in the past 12 months when 5 or more drinks were consumed by males (or ≥ 4 drinks by females), calculated by using midpoints from 6 categorical responses. We assessed frequency of drunkenness by the number of days in past year when the respondent was drunk or very high on alcohol, coded in the same manner as HED.

Predictors and covariates.

We used 2 measures as proxies of distinct dimensions of ethnic drinking culture: drinking prevalence and detrimental drinking pattern (DDP), both referencing the country of origin (COO) and based on self-identified Asian ethnicity. Drinking prevalence refers to the extent alcohol consumption is integrated into a society as an ordinary occurrence involving a large segment of the population, and DDP describes the pattern of consumption commonly exhibited or socially accepted.22 We constructed drinking prevalence by using international data compiled by the World Health Organization on per capita alcohol consumption estimates and abstinence rates for adults aged 15 years or older,46 first by creating for each an ordinal variable with 3 categories representing tertiles (reverse coding abstinence rates to indicate prevalence of drinking) and then summing their values. In international research, drinking prevalence was inversely associated with informal social pressures to reduce drinking,47–49 which suggests its utility as a measure of drinking culture.

Ranging from 1 for the least risky pattern to 4 for the most risky, the DDP scale is based on the World Health Organization’s aggregate alcohol consumption data and key informant surveys on drinking practices prevalent in a country, covering 6 specific areas (e.g., heavy festive drinking and drunkenness, drinking with meals, and drinking in public places).50 This scale has been validated with population survey data in 13 countries, with good correspondence with individual-level alcohol consumption.51

We based neighborhood SES on an index constructed from 4 items about the respondent’s wave 1 neighborhood: proportion of persons with incomes below poverty level, proportion of persons aged 25 years or older without a college degree, proportion of persons aged 16 years or older without managerial or professional jobs, and unemployment rate of persons aged 16 years or older. We coded each item into an ordinal variable with 3 categories representing tertiles and summed to create a neighborhood SES index ranging from 4 to 12, with higher values indicating higher SES. The Cronbach α for this construct with our sample was 0.82. Neighborhood coethnic density indicates the proportion of Asians and Pacific Islanders at wave 1. Add Health contextual data do not disaggregate Asian Americans from Pacific Islanders in this neighborhood measure.

As an indicator of individual-level SES, we assessed mother’s education (wave 1) by using a binary variable indicating that the youth’s residential mother had obtained at least a 4-year college degree (vs lower education levels). Other individual-level SES measures (e.g., household income, father’s education) had large amounts of missing data, and maternal education is an important predictor of adolescent risk behaviors in the larger Add Health sample.52,53

We assessed attachment to mother (at wave 1) as a sum of 7 questions that used a 5-point scale asking whether respondents felt their mother was warm and loving, cared about them, encouraged them to be independent, and talked with them about things when they did something wrong, as well as whether they felt close to their mother, satisfied with the way they communicated with their mother, and satisfied with their relationship with their mother. Attachment to mother is associated with lower alcohol risk for adolescents54 and college students.55 The Cronbach α for this construct was 0.86 (range = 11–35; mean = 29.9; SD = 4.3).

Early onset of drinking indicates having had an alcoholic drink at the age of 15 years or earlier. Early onset of drinking is a predictor of adult alcohol use disorders and other health and social outcomes.15,56–66

US nativity indicates being born in the United States. It is associated with greater alcohol consumption among children of immigrants.67–70

Friends’ drinking indicates the number of friends who drank alcohol at least monthly among the 3 best friends at wave 1 (range = 0–3; mean = 0.8; SD = 1.1). Peer drinking is a consistent predictor of adolescent and college drinking.71–74

Statistical Analysis

We used growth mixture modeling to identify trajectory classes for HED and drunkenness to identify relatively homogeneous clusters, or latent classes, of individuals who had similar growth parameters. Growth mixture modeling estimates the probability of membership in each of the classes.75,76 We used linear models with log-transformed outcome variables. We used 3 model characteristics to determine the number of trajectory classes: (1) Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) values that balance maximizing the likelihood with keeping the model parsimonious, with lower values indicating better-fitting models; (2) classification quality, indicated by posterior probabilities; and (3) usefulness of the classes as determined by similarity of trajectory shapes and the proportion of individuals in each class.76 Capitalizing on the longitudinal design of Add Health, we used age-based models. We used maximum likelihood estimation in MPlus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) to accommodate missing data under the assumption that data were missing at random. We assigned respondents to the class with the highest probability of membership by using average posterior probabilities.

To identify predictors of trajectory class membership, we conducted multinomial logistic regression with SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) with the assigned class as the outcome. We weighted data and adjusted standard errors to accommodate study design, nonresponse, and poststratification adjustments. To investigate potential collinearity among the predictors, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis using Mplus version 7. The condition number (ratio of the largest to smallest eigenvalue of the design matrix) was 4.18, indicating no problems with collinearity.

RESULTS

Asian American young adults in our sample were relatively highly educated, with about half (51.3%) of the sample having a 4-year college or more advanced degree by wave 4. Mothers also tended to be highly educated, with 43.1% having at least a 4-year college degree. The mean age at wave 4 was 27.5 years (SD = 1.6; range = 24–32). About half (52.8%) of the sample was born in the United States. Filipinos (42.7%) were the largest ethnic group in our sample, followed by the Chinese (17.2%), Koreans (12.6%), Vietnamese (12.6%), Japanese (10.5%), and Asian Indians (4.4%). Further details on sample characteristics are provided elsewhere.22

Table 1 shows alcohol consumption levels and patterns in the countries of origin. India had the smallest volume of alcohol consumed per person, followed by Vietnam and China. Korea had the largest estimated volume of consumption, followed by Japan. Alcohol abstinence rates tended to inversely mirror per capita consumption levels, with countries of higher per capita consumption having lower abstinence rates. Japan and China had a DDP score of 2, whereas the rest had 3, indicating a more detrimental drinking pattern.

TABLE 1—

Per Capita Alcohol Consumption and Detrimental Drinking Pattern in Country of Origin

| Ethnic Group | Per Capita Annual Alcohol Consumption, in Liters × 100 | Lifetime Alcohol Abstinence Rate, % | Detrimental Drinking Pattern |

| Asian Indian | 2.59 | 79.2 | 3 |

| Vietnamese | 3.77 | 67.1 | 3 |

| Filipino | 6.38 | 49.5 | 3 |

| Chinese or Taiwanese | 5.91 | 28.2 | 2 |

| Japanese | 8.03 | 9.4 | 2 |

| Korean | 14.8 | 12.8 | 3 |

Note. From the World Health Organization’s Global Information System on Alcohol and Health database.46 Per capita alcohol consumption estimates in liters of ethanol consumed (2005) were based on alcohol production and sales and general population survey data to include both recorded and unrecorded consumption. Abstinence rates were compiled from 2001 to 2003. Detrimental drinking pattern scores were used from 2008.

Identification of Trajectory Classes

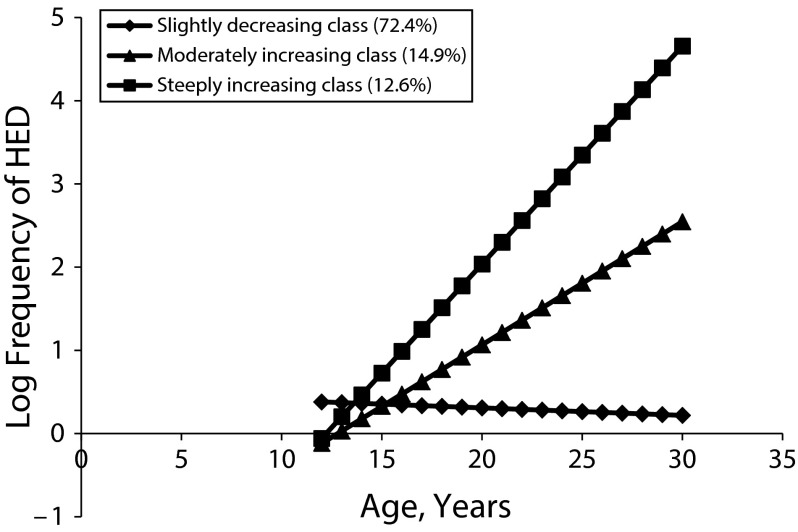

We identified similar trajectory classes for both outcomes. The 3-class solution for HED frequency (Figure 1), consisting of the slightly decreasing class (72.4%), the steeply increasing class (12.6%), and the moderately increasing class (14.9%), provided more distinct and interpretable classes than a 2- or 4-class solution. It had the lowest BIC and AIC values (Table 2), and the average posterior probability for individuals for each of the 3 classes were 0.92, 0.88, and 0.97, suggesting high classification quality.76 A reasonably high entropy of 0.80 (close to 1.0) indicated a successful conversion and relatively precise class assignments. 77

FIGURE 1—

Heavy episodic drinking (HED) growth trajectory classes among Asian Americans transitioning from adolescence to adulthood: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, United States, 1994–2008.

TABLE 2—

Growth Mixture Models of Heavy Episodic Drinking and Drunkenness Among Asian Americans Transitioning From Adolescence to Adulthood: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, United States, 1994–2008

| Drinking Behavior and Models | AIC | BIC |

| Heavy episodic drinking | ||

| Linear 2-class | 12928.01 | 12990.35 |

| Linear 3-class | 12594.88 | 12672.80 |

| Linear 4-class | 12600.88 | 12694.39 |

| Drunkenness | ||

| Linear 2-class | 12248.94 | 12311.28 |

| Linear 3-class | 11950.54 | 12028.46 |

| Linear 4-class | 12247.97 | 12341.48 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion. Linear 3-class models were deemed most parsimonious as evidenced by fit indices and interpretability

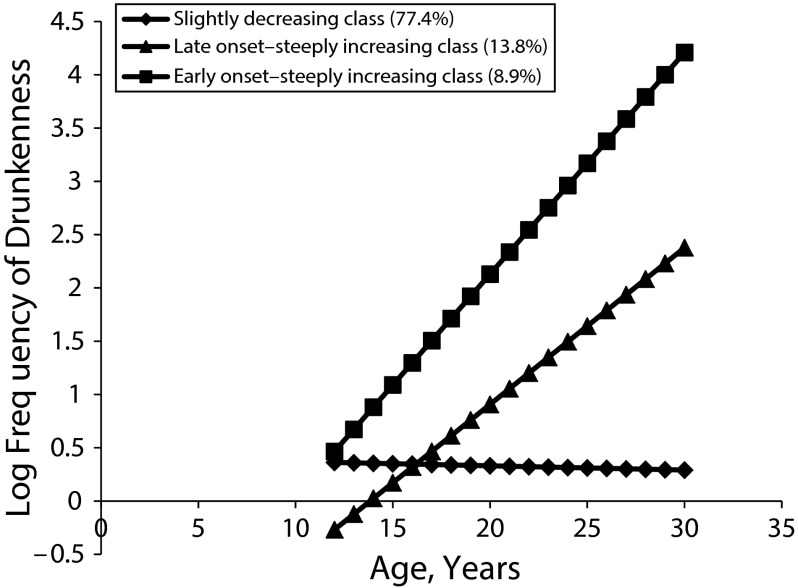

The 3-class solution for frequency of drunkenness had the lowest BIC and AIC among all the solutions considered (Table 2), a high entropy value of 0.82, and high average posterior probabilities of 0.93, 0.87, and 0.97. The 3 classes are characterized as the slightly decreasing class (77.4%), the late onset–steeply increasing class (13.8%), and the early onset–steeply increasing class (8.9%; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Drunkenness growth trajectory classes among Asian Americans transitioning from adolescence to adulthood: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, United States, 1994–2008.

The slightly decreasing classes represent the normative drinking trajectories, with low frequencies of HED and drunkenness that further decline as adolescents transition to adulthood. All other trajectory classes indicate problematic drinking patterns, showing increasing frequencies of HED and drunkenness, with the steeply increasing HED class and the early onset–steeply increasing drunkenness class being most problematic.

Predictors of Trajectory Class Membership

Table 3 shows unadjusted odds ratios from bivariate regressions and adjusted odds ratios from multivariate multinomial logistic regressions predicting membership in the trajectory classes. The COO drinking prevalence, peer drinking, and early onset of drinking were predictive of membership in both the moderately increasing and the steeply increasing HED classes. When we controlled for other covariates, COO detrimental drinking pattern and US nativity were predictive of the steeply increasing HED class. The bivariate association between neighborhood coethnic density and the moderately increasing HED class was no longer significant when we controlled for other covariates. Neighborhood SES and mother’s education were not predictive of HED classes.

TABLE 3—

Predictors of Trajectory Class Membership Among Asian Americans Transitioning From Adolescence to Adulthood: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, United States, 1994–2008

| Predictors | Crude OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Trajectory classes of heavy episodic drinking | ||

| Moderately increasing classa | ||

| Male | 1.42* (1.01, 2.09) | 2.22** (1.36, 3.65) |

| US-born | 1.95** (1.31, 2.90) | 1.28 (0.77, 2.11) |

| COO drinking prevalence | 1.22* (1.05, 1.40) | 1.27* (1.03, 1.58) |

| COO DDP | 0.77 (0.52, 1.13) | 1.65 (0.92, 2.97) |

| Neighborhood SES | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) |

| Neighborhood coethnic density | 1.35 (0.64, 2.83) | 0.55 (0.20, 1.48) |

| Mother’s college degreeb | 0.93 (0.64, 1.36) | 0.98 (0.72, 2.12) |

| Attachment to mother | 1.00 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.04 (0.60, 1.60) |

| Peer drinking | 1.53*** (1.31, 1.78) | 1.55*** (1.26, 1.91) |

| Early onset of drinkingc | 4.13*** (2.65, 6.44) | 4.39*** (2.53, 7.61) |

| Steeply increasing classa | ||

| Male | 1.82** (1.24, 2.67) | 2.81** (1.48, 5.35) |

| US-born | 4.46*** (2.74, 7.27) | 4.25*** (2.04, 8.84) |

| COO drinking prevalence | 1.18* (1.02, 1.37) | 1.39* (1.06, 1.81) |

| COO DDP | 0.95 (0.63, 1.42) | 2.85* (1.30, 6.23) |

| Neighborhood SES | 1.04 (0.96, 1.13) | 1.05 (0.91, 1.21) |

| Neighborhood coethnic density | 2.42* (1.18, 4.97) | 1.15 (0.37, 3.57) |

| Mother’s college degreeb | 1.13 (0.77, 1.66) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.90) |

| Attachment to mother | 1.06* (1.01, 1.11) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) |

| Peer drinking | 1.39*** (1.19, 1.64) | 1.48** (1.13, 1.92) |

| Early onset of drinkingc | 5.09*** (3.17, 8.19) | 5.29*** (2.79, 10.00) |

| Trajectory classes of drunkenness | ||

| Late onset–steeply increasing classa | ||

| Male | 1.23 (0.84, 1.82) | 2.49** (1.44, 4.29) |

| US-born | 2.68*** (1.71, 4.20) | 1.75* (1.01, 3.03) |

| COO drinking prevalence | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.24) |

| COO DDP | 1.35 (0.66, 2.14) | 1.93 (0.99, 3.75) |

| Neighborhood SES | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) |

| Neighborhood coethnic density | 0.57 (0.24, 1.36) | 0.32 (0.10, 1.04) |

| Mother’s college degreeb | 1.92** (1.27, 2.89) | 2.52** (1.46, 4.33) |

| Attachment to mother | 1.05 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) |

| Peer drinking | 1.09 (0.91, 1.30) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.30) |

| Early onset of drinkingc | 2.40*** (1.48, 3.88) | 4.11*** (2.25, 7.51) |

| Early onset–steeply increasing classa | ||

| Male | 2.22** (1.40, 3.53) | 5.49*** (2.41, 12.50) |

| US-born | 5.48*** (3.01, 9.98) | 3.41** (1.53, 7.62) |

| COO drinking prevalence | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 1.26 (0.92, 1.72) |

| COO DDP | 0.89 (0.56, 1.41) | 4.66** (1.73, 12.57) |

| Neighborhood SES | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) | 1.27** (1.07, 1.51) |

| Neighborhood coethnic density | 1.59 (0.68, 3.72) | 0.46 (0.10, 1.68) |

| Mother’s college degreeb | 1.81* (1.15, 2.85) | 2.55* (1.24, 5.27) |

| Attachment to mother | 1.07* (1.01, 1.14) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.15) |

| Peer drinking | 1.56*** (1.31, 1.87) | 1.43* (1.05, 1.96) |

| Early onset of drinkingc | 8.27*** (4.95, 13.80) | 9.49*** (4.64, 19.38) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; COO = country of origin; DDP = detrimental drinking pattern; OR = odds ratio; SES = socioeconomic status.

Slightly decreasing class as reference group.

Lower level than a 4-year college degree as reference group.

First drinking at age 16 years or older as reference group.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

As for drunkenness trajectory classes, COO detrimental drinking pattern increased the risk of developing the most problematic early onset–steeply increasing class in the multivariate model when we controlled for other covariates. The COO drinking prevalence was not predictive of membership in either of the problematic classes. Mother’s education was predictive of membership in both the early onset– and late onset–steeply increasing classes. High neighborhood SES and peer drinking were predictive only of the early onset–steeply increasing drunkenness class. US nativity and early onset of drinking were predictive of membership in both problematic drunkenness classes. Being male was predictive of membership in all the problematic HED and drunkenness classes. Coethnic density was not predictive of drunkenness trajectory class membership.

DISCUSSION

This study adds to the limited body of research on the cultural and socioeconomic contextual factors that influence Asian American drinking patterns during a critical period of the life course, from adolescence into adulthood. We found that ethnic drinking cultures were significantly associated with problematic drinking patterns, with drinking prevalence of one’s COO predictive of HED classes and COO detrimental drinking patterns predictive of the most problematic HED and drunkenness classes. Higher neighborhood SES and mother’s education were predictive of problematic drunkenness classes. Neighborhood coethnic density was predictive of neither HED nor drunkenness trajectory classes. These findings highlight the enduring influence of drinking cultures from one’s COO, independent of US nativity (our proxy for acculturation), and adolescent socioeconomic factors on Asian American developmental drinking trajectories.

The substantive findings involving the 2 dimensions of ethnic drinking culture are noteworthy, as the associations between COO drinking prevalence and HED trajectory classes and between COO detrimental drinking pattern and the most problematic HED and drunkenness trajectory classes are quite logical. Because drinking prevalence largely is a function of drinking rates and alcohol consumption volume and the prevalence of heavy drinkers tends to be high in high-consumption countries,78 it is plausible that HED is more frequent among individuals from COO with a higher degree of drinking prevalence. Steeply increasing HED and drunkenness are consistent with the specific drinking patterns characterized by DDP (i.e., the tendency to engage in HED and drunkenness, often in public places, as opposed to infrequent light or moderate drinking).50,79 Together, these findings bolster the plausibility of the influence of the 2 distinct dimensions of ethnic drinking culture on specific drinking behaviors.

Our findings that high neighborhood-level and individual-level SES were predictive of drunkenness trajectory classes, though not HED, are at odds with much of health disparities research, which attributes increased risks of problem drinking to socioeconomic disadvantage under the premise that drinking is a way to cope with stressors stemming from disadvantage.80–82 Instead, our findings are consistent with previous studies reporting higher alcohol consumption among adolescents of higher neighborhood83 or individual SES.84,85 This may have to do with the fact that Asian American ethnic groups from countries with greater drinking prevalence or with more harmful drinking patterns, such as Korea, Japan, and the Philippines, tend to have relatively high SES in the United States.44 Our finding that higher SES was predictive only of drunkenness trajectory classes and not HED should be assessed with other longitudinal samples of Asian Americans.

Although previous research has found protective effects of neighborhood coethnic density on health behaviors including alcohol use,36,37,86 we found that such density was not predictive of problem drinking trajectories. Our findings are consistent with other studies that reported no significant associations between social resources (likely to have beneficial effects on health behaviors) and coethnic density for Asians87 and Latinos.88

Though it is not the substantive focus of the current study, it is worth noting that early onset of drinking was a consistent and strong predictor of problematic drinking trajectories. These findings add to the literature demonstrating long-lasting consequences of early onset of drinking on problematic alcohol use,15,56,60–62,64,66 which previously lacked specific information on Asian Americans.

We acknowledge some limitations of the current study. First, we used proxies of ethnic drinking culture dimensions, as data on specific drinking-related values, norms, and behaviors within ethnic communities in the United States were unavailable. Research on these more detailed elements of ethnic drinking culture in the United States is needed. Second, the relationships of high SES with more problematic drinking trajectories may be attributable at least partially, to the absence of the most impoverished Asian American subgroups such as Cambodian and Hmong in the Add Health sample, which may have hampered the ability to accurately assess the influence of disadvantage on drinking. Third, our findings are only generalizable to Asian American adolescents enrolled in school during the 1994–1995 academic year, omitting those who dropped out of school and who may be particularly likely to show problematic drinking trajectories. Finally, because US nativity is a crude measure of acculturation, it would be informative to replicate these analyses with more elaborate measures of acculturation and ethnic identification.

Despite these limitations, the current study has a number of important strengths, both practical and theoretical. The use of a longitudinal design enabled us to demonstrate the influence of ethnic drinking cultures more conclusively. Our findings help identify cultural and socioeconomic profiles of Asian American subgroups at high risk for developing problematic drinking patterns during and after the transition to young adulthood that might be targeted in future interventions: US-born males who are from ethnic cultures in which drinking is prevalent or practiced in a more detrimental pattern, who are of higher SES, and who initiate drinking at an early age. Furthermore, by using the specific dimensions of ethnic drinking cultures, this study highlights specific drinking-related cultural conditions associated with Asian ethnicities that may account for diverse drinking outcomes among Asian ethnic groups; for example, the well-noted differences in drinking between Chinese and Koreans may be explained by a greater prevalence of drinking and a more detrimental pattern of drinking in Korean ethnic drinking culture. This is an important innovation that helps advance the field beyond the current practice of comparing drinking outcomes among a few subgroups, mostly between Chinese and Korean,2,4,5,7,8 without clarifying the specific properties associated with ethnicity that may account for diverse outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R03AA019791 (W. K. Cook., PI). This research utilizes data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This research was funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Human Participant Protection

This study was conducted under approval of the institutional review board of the Public Health Institute, Oakland, CA.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doran N, Myers MG, Luczak SE, Carr LG, Wall TL. Stability of heavy episodic drinking in Chinese- and Korean-American college students: effects of ALDH2 gene status and behavioral undercontrol. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(6):789–797. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duranceaux NC, Schuckit MA, Luczak SE, Eng MY, Carr LG, Wall TL. Ethnic differences in level of response to alcohol between Chinese Americans and Korean Americans. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(2):227–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendershot CS, Dillworth TM, Neighbors C, George WH. Differential effects of acculturation on drinking behavior in Chinese- and Korean-American college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(1):121–128. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luczak SE, Wall TL, Shea SH, Byun SM, Carr LG. Binge drinking in Chinese, Korean, and White college students: genetic and ethnic group differences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(4):306–309. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamoto D, Takamatsu S, Castellanos J. Binge drinking and alcohol-related problems among US-born Asian Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(3):219–227. doi: 10.1037/a0028422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luczak SE, Wall TL, Cook TA, Shea SH, Carr LG. ALDH2 status and conduct disorder mediate the relationship between ethnicity and alcohol dependence in Chinese, Korean, and White American college students. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(2):271–278. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendershot CS, Collins SE, George WH et al. Associations of ALDH2 and ADH1B genotypes with alcohol-related phenotypes in Asian young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(5):839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luczak SE, Corbett K, Oh C, Carr LG, Wall TL. Religious influences on heavy episodic drinking in Chinese-American and Korean-American college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(4):467–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendershot CS, Neighbors C, George WH et al. ALDH2, ADH1B and alcohol expectancies: integrating genetic and learning perspectives. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(3):452–463. doi: 10.1037/a0016629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;(14):54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. How trajectories of reasons for alcohol use relate to trajectories of binge drinking: national panel data spanning late adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2011;47(2):311–317. doi: 10.1037/a0021939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DB. The natural history of adolescent alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2004;99(suppl 2):5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: predictors and substance abuse outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sher KJ, Gotham HJ. Pathological alcohol involvement: a developmental disorder of young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):933–956. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutmann MC. Ethnicity, alcohol, and acculturation. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(2):173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(5):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salant T, Lauderdale DS. Measuring culture: a critical review of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook WK, Hofstetter CR, Kang SM, Hovell MF, Irvin V. Rethinking acculturation: a study of alcohol use of Korean American adolescents in Southern California. Contemp Drug Probl. 2009;36(1-2):217–244. doi: 10.1177/009145090903600111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook WK, Bond J, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Zemore SE. Who’s at risk? Ethnic drinking cultures, foreign nativity, and Asian American young adult drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(4):532–541. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portes A, Guarnizo LE, Landolt P. The study of transnationalism: pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethn Racial Stud. 1999;22(2):217–237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiller N, Basch L, Blanc C. From immigrant to transmigrant: theorizing transnational migration. Anthropol Q. 1995;68(1):48–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): the association between birthplace, acculturation and alcohol abuse and dependence across Hispanic national groups. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eitle TM, Wahl AM, Aranda E. Immigrant generation, selective acculturation, and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents. Soc Sci Res. 2009;38(3):732–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahl AM, Eitle TM. Gender, acculturation and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents: a multi-ethnic comparison. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(2):153–165. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9179-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook WK, Mulia N, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Ethnic drinking cultures and alcohol use among Asian American adults: findings from a national survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(3):340–348. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101(1):139–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzpatrick K, LaGory M. Unhealthy Places: The Ecology of Risk in the Urban Landscape. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sampson RJ. Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. Am J Sociol. 1987;93(2):349–382. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social disorganization theory. Am J Sociol. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romley JA, Cohen D, Ringel J, Sturm R. Alcohol and environmental justice: the density of liquor stores and bars in urban neighborhoods in the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(1):48–55. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones-Webb R, McKee P, Hannan P et al. Alcohol and malt liquor availability and promotion and homicide in inner cities. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(2):159–177. doi: 10.1080/10826080701690557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Areas of disadvantage: a systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(1):84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bécares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M. The ethnic density effect on alcohol use among ethnic minority people in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):20–25. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.087114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bécares L, Shaw R, Nazroo J et al. Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality, and health behaviors: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e33–e66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leu J, Walton E, Takeuchi D. Contextualizing acculturation: gender, family, and community reception influences on Asian immigrant mental health. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48(3-4):168–180. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. People like us: ethnic group density effects on health. Ethn Health. 2008;13(4):321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bécares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M. The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health Place. 2009;15(3):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halpern D, Nazroo J. The ethnic density effect: results from a national community survey of England and Wales. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46(1):34–46. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou M, Xiong YS. The multifaceted American experiences of the children of Asian immigrants: lessons for segmented assimilation. Ethn Racial Stud. 2005;28(6):1119–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou M, Gatewood J. Contemporary Asian America: A Multidisciplinary Reader. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook WK, Chung C, Tseng W. Demographic and socioeconomic profiles of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. San Francisco, CA, and Washington, DC: Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum; 2011. Available at: http://www.apiahf.org/resources/resources-database/profilesofaanhpi. Accessed October 5, 2013.

- 45.Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: study design. 2009. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. Accessed January 11, 2012.

- 46. World Health Organization. Global Information System on Alcohol and Health. 2011. Available at: http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?theme=GISAH. Accessed February 15, 2013.

- 47.Joosten J, Knibbe RA, Derickx M, Hradilova-Selin K, Holmila M. Criticism of drinking as informal social control: a study in 18 countries. Contemp Drug Probl. 2009;36(1-2):85–109. doi: 10.1177/009145090903600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selin KH, Holmila M, Knibbe R. Informal social control of drinking in intimate relationships—a comparative analysis. Contemp Drug Probl. 2009;36(1):31–59. doi: 10.1177/009145090903600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmila M, Raitasalo K, Knibbe RA. Country variations in family members’ informal pressure to drink less. Contemp Drug Probl. 2009;36(1/2) a126808. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehm J, Rehn N, Room R et al. The global distribution of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9(4):147–156. doi: 10.1159/000072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gmel G, Room R, Kuendig H, Kuntsche S. Detrimental drinking patterns: empirical validation of the pattern values score of the Global Burden of Disease 2000 study in 13 countries. J Subst Use. 2007;12(5):337–358. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ford CA, Pence BW, Miller WC et al. Predicting adolescents’ longitudinal risk for sexually transmitted infection: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):657–664. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newbern EC, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, Kaufman JS. Family socioeconomic status and self-reported sexually transmitted diseases among Black and White American adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(9):533–541. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000137898.17919.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo CC, Cheng TC. Onset drinking: how it is related both to mother’s drinking and mother–child relationships. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(6):888–900. doi: 10.3109/10826080903550513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Labrie JW, Sessoms AE. Parents still matter: the role of parental attachment in risky drinking among college students. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(1):91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malone PS, Northrup TF, Masyn KE, Lamis DA, Lamont AE. Initiation and persistence of alcohol use in United States Black, Hispanic, and White male and female youth. Addict Behav. 2012;37(3):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Gilder DA, Lau P, Wilhelmsen KC. Age at first intoxication and alcohol use disorders in Southwest California Indians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(11):1856–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grant JD, Verges A, Jackson KM, Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK. Age and ethnic differences in the onset, persistence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2012;107(4):756–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jenkins MB, Agrawal A, Lynskey MT et al. Correlates of alcohol abuse/dependence in early-onset alcohol-using women. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT et al. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):109–118. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dawson DA. The link between family history and early onscoholism: earlier initiation of drinking or more rapid development of dependence? J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(5):637–646. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maldonado-Molina MM, Reingle JM, Jennings WG, Prado G. Drinking and driving among immigrant and US-born Hispanic young adults: results from a longitudinal and nationally representative study. Addict Behav. 2011;36(4):381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ et al. What accounts for differences in substance use among US-born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents?: results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(2):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gil AG, Wagner G, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(4):443–458. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vega WA, Gil AG. A model for explaining drug use behaviors among Hispanic adolescents. Drugs Soc. 1999;14:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: a review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;(14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(3):331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henry KL, Slater MD, Oetting ER. Alcohol use in early adolescence: the effect of changes in risk taking, perceived harm and friends’ alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(2):275–283. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(2):139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(6):882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personality Psychol Compass. 2008;2(1):302–317. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S . Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity Research and Public Policy. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M . Alcohol use. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease due to Selective Major Risk Factors. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. pp. 959–1091. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mulia N, Zemore SE. Social adversity, stress, and alcohol problems: are racial/ethnic minorities and the poor more vulnerable? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(4):570–580. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mossakowski KN. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(6):947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khan S, Murray RP, Barnes GE. A structural equation model of the effect of poverty and unemployment on alcohol abuse. Addict Behav. 2002;27(3):405–423. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song E-Y, Reboussin BA, Foley KL, Kaltenbach LA, Wagoner KG, Wolfson M. Selected community characteristics and underage drinking. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(2):179–194. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Humensky JL. Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(5):772–782. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Association between neighborhood context and smoking prevalence among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):885–892. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walton E. Resurgent ethnicity among Asian Americans: ethnic neighborhood context and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(3):378–394. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Almeida J, Kawachi I, Molnar BE, Subramanian SV. A multilevel analysis of social ties and social cohesion among Latinos and their neighborhoods: results from Chicago. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):745–759. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9375-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]