Abstract

Introduction

A high-quality health system should deliver care that is free from harm. Few large-scale studies of adverse events have been undertaken in children's healthcare internationally, and none in Australia. The aim of this study is to measure the frequency and types of adverse events encountered in Australian paediatric care in a range of healthcare settings.

Methods and analysis

A form of retrospective medical record review, the Institute of Healthcare Improvement's Global Trigger Tool, will be modified to collect data. Records of children aged <16 years managed during 2012 and 2013 will be reviewed. We aim to review 6000–8000 records from a sample of healthcare practices (hospitals, general practices and specialists).

Ethics and dissemination

Human Research Ethics Committee approvals have been received from the Sydney Children's Hospital Network, Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service, and the Women's and Children's Hospital Network in South Australia. An application is under review with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. The authors will submit the results of the study to relevant journals and undertake national and international oral presentations to researchers, clinicians and policymakers.

Keywords: AUDIT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data will be collected from a range of healthcare practice types (hospital, general practice and specialists).

Collecting data from a range of healthcare practices and classifying the types of adverse events encountered will allow priorities to be set as to where improvement efforts are needed to reduce harm to children.

Potential selection bias for experts involved in the development process of adverse event triggers.

The use of a single surveyor to review the medical record.

Introduction

A high-quality health system should deliver care that is free from harm.1 However, population studies have shown that 10% of adult hospital admissions are associated with adverse events (AEs).2–4 For children, a leading hospital in the USA found 37 AEs per 100 admissions,5 while a multicentre Canadian paediatric study using a validated tool showed that 9.2% of patients experience an AE, with higher rates recorded in academic centres when compared with community settings.6 Few large-scale AE studies have been undertaken internationally in children's healthcare, and none in Australia.

Retrospective medical record review (MRR) can provide data on the frequency and type of AEs.7 One method, the Global Trigger Tool (GTT), initially developed in 2003 by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for use in hospitals,8 has been modified for paediatric hospitals,5 6 9–11 neonatal intensive care units,12 paediatric intensive care units,13 paediatric otolaryngology14 and primary care.15–17 For general paediatric inpatients in North America and Europe, the GTT has detected 6–37 AEs per 100 admissions.5 6 9 10 There are no published studies using a GTT in Australian paediatric care.

This research project (‘CareTrack Kids’—CTK) involves three related aims and studies: part 1—developing a set of clinical indicators for common paediatric conditions; part 2—measuring the appropriateness of paediatric care in Australia using these clinical indicators; and part 3—this study—measuring the frequency and types of AEs encountered in Australian paediatric care during 2012 and 2013. Study protocols describing the methodology of the other two CTK studies are presented in separate protocol papers.18 19

This study is novel in that data will be collected from a range of healthcare practice types (hospital, general practice and specialists), which has never been undertaken in adult or paediatric settings. Collecting data from a range of healthcare practices and classifying the type of AEs encountered will allow priorities to be set as to where improvement efforts are needed to reduce harm to children.20

Methods and analysis

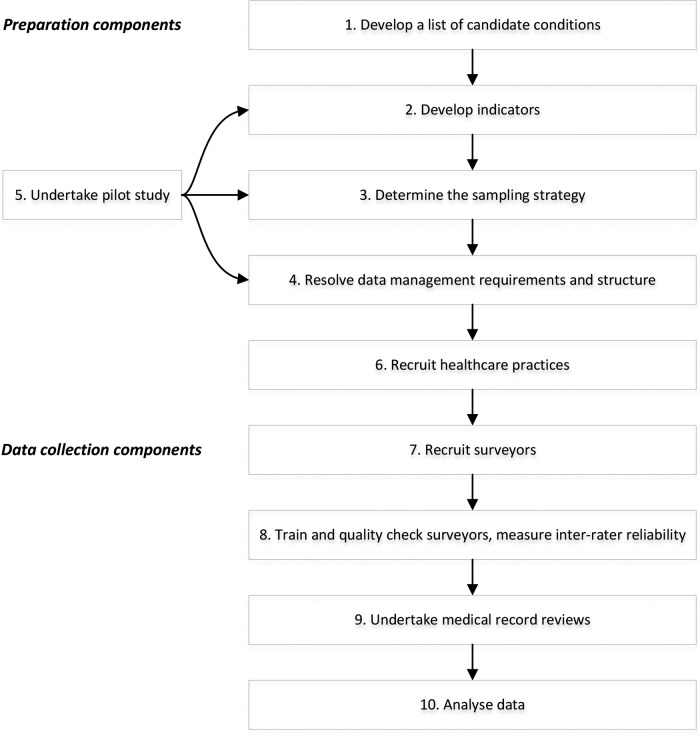

There are nine components to the CTK AE study protocol (figure 1). Elements of component 1 (develop inclusion criteria and sampling strategy), component 5 (recruit healthcare practices) and component 7 (train and quality check data collectors and measuring inter-rater reliability (IRR)) are described in more detail in the part 2 CTK appropriateness of healthcare delivered study protocol.18

Figure 1.

Components of the CareTrack Kids (CTK) adverse event study.

Component 1: develop definitions, inclusion criteria, sampling strategy and tools

Definitions

This study will use the definitions (box 1) for patient safety from the WHO's International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS).21 They are recent, have been subjected to formal development work and are inclusive with few caveats. They also broadly align with those used for the National Health Service (NHS) Institute for Improvement and Innovation's Paediatric Trigger Tool,22 which facilitates making comparisons between countries.

Box 1. Definitions from the International Classification of Patient Safety21.

Patient safety is “the reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with healthcare to an acceptable minimum. An acceptable minimum refers to the collective notions of given current knowledge, resources available and the context in which care was delivered weighed against the risk of non-treatment or other treatment”

A patient safety incident is “an event or circumstance that could have resulted, or did result, in unnecessary harm to a patient”. The use of the word ‘unnecessary’ in this definition recognises that errors, violation, patient abuse and deliberately unsafe acts occur in healthcare. These are considered incidents. Certain forms of harm, however, such as an incision for a laparotomy are necessary. This is not considered an incident. Incidents arise from either unintended or intended acts. Errors are, by definition, unintentional, whereas violations are usually intentional, though rarely malicious, and may become routine and automatic in certain contexts

An adverse event is “an incident that results in harm to a patient”.21 Harm “implies impairment of structure or function of the body and/or any deleterious effect arising there from, including disease, injury, suffering, disability and death, and may be physical, social or psychological”21

Healthcare-associated harm is “harm arising from or associated with plans or actions taken during the provision of healthcare, rather than an underlying disease or injury”

Inclusion criteria

Medical records will be reviewed of children aged <16 years managed for at least 1 of 16 CTK conditions,18 in one of three states of Australia: New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (Qld) or South Australia (SA) during 2012 and 2013.

Sampling strategy

We aim to review 6000–8000 records using a multistage, randomised stratified sampling plan.18 The number of MRRs that we propose is large compared with previous paediatric GTT studies which range from 50 to 3992 and average 1200.5 6 9–14 23 Our relatively large sample size will enable analysis and characterisation of a large number of types of AEs.20

Tools

We will use a modified version of the GTT8 to collect data. GTTs use a series of ‘triggers’ to screen the record for a potential AE. The presence of a trigger signals the need for an in-depth review. AEs are coded according to type, and AE rates are calculated. The original IHI version of the GTT has been shown to have high specificity, moderate sensitivity and favourable inter-rater and intra-rater reliability using hospital-based records for adult patients.24

Component 2: collate and ratify triggers

Triggers applicable to Australian paediatric healthcare settings will be developed. We will search the literature using MEDLINE and CINAHL for the term ‘global trigger tool’ to collate existing tools and triggers. Examples of triggers used previously in GTT studies6 10 17 25 include: clinical events—transfusion or use of blood products, cardiac and respiratory arrest; use of medications—vitamin K administration, antiemetic use; laboratory investigations—positive blood culture, glucose <2.8 mmol/L, rising blood urea nitrogen or serum creatinine >2 times baseline; and attendance or admissions—transfer to a higher level of care, readmission within 30 days.

A set of candidate triggers will be collated, listing their positive predictive values where available. Using a Delphi process, clinical experts (members of the CTK team and experts nominated by the team) will vote on the most applicable triggers over two rounds. We will develop three sets of triggers—one for hospital use (encompassing emergency department visits and inpatient admissions), one for general practice and one for specialist clinics and offices, including outpatients. Clinical experts will vote on their appropriate trigger sets.

Component 3: resolve data collection requirements and structure

Data collection

A new module will be added to the web-based tool developed for the CareTrack Australia study26 27 to include the collection of AEs. The purpose of the tool is to enter data during MRR and enable subsequent data analysis. The tool will be on dedicated laptop computers and support secure data access, data encryption, offline data collection and subsequent database synchronisation (to mitigate against the problems of fire walls and poor internet connectivity in various healthcare settings). The tool will also support validation and confirmation procedures to measure IRR and workflows between researchers with a range of roles in reviewing records (see component 8).

Data fields

If a trigger is positive, the following data fields will be recorded: positive triggers (see component 2); a narrative based on relevant information in the record; AE origin; incident type;20 21 contributing factors; causation (box 2); prevention (box 3); level of outcome or severity (box 4); type of patient harm and fields to measure the rate of AEs. These are described below.

Box 2. Healthcare management causation scale30 32.

1=Virtually no evidence

2=Slight to modest evidence

3=Close call (less likely than not)

4=Close call (more likely than not)

5=Moderate or strong evidence

6=Virtually certain evidence

Box 3. Healthcare management prevention scale30 32.

1=Virtually no evidence

2=Slight to modest evidence

3=Close call, <50:50

4=Close call, >50:50

5=Moderate/strong evidence

6=Virtually certain evidence

Box 4. The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC-MERP) scale for adverse event outcome38.

Category E: Temporary harm to the patient requiring intervention

Category F: Temporary harm to the patient requiring initial or prolonged hospitalisation

Category G: Permanent patient harm

Category H: Intervention necessary to sustain life

Category I: Patient death

The narrative

A brief medical history of the patient and the context and circumstances in which the AE occurred will be recorded.

Origin of AEs

The type of healthcare practice where the AE primarily originated will be recorded. Previous studies have found that AEs may occur at different practices or practice types from where they are detected.17 25

Incident type

The incident type ICPS21 classification will be recorded. An incident type is a category made up of incidents of a common nature, grouped because of shared agreed features and is a ‘parent’ category under which many concepts may be grouped (box 5).21 The benefit of collecting incident type is that this is the main method of classifying what goes wrong into clinically useful categories.20 A brief free text descriptor of what happened in the form of a ‘Principal Natural Category’(PNC)20 will be included, for example, delayed diagnosis of fractured ulna, rash secondary to an adverse reaction to measles, mumps and rubella vaccine.

Box 5. International Classification of Patient Safety Incident Types21.

Clinical administration

Clinical processes and procedures

Documentation

Healthcare-associated infection

Medication/intravenous fluids

Blood/blood products

Nutrition

Oxygen, gas or vapour

Medical device or equipment

Behaviour

Patient accidents

Infrastructure

Building and fixtures

Resources and organisational management

Contributing factors

Contributing factors are the circumstances, actions or influences which are thought to have played a part in the origin or development of an incident or to increase the risk of an incident.21 Examples include human factors such as behaviour, performance or communication; system factors such as work environment; and external factors beyond the direct control of the organisation, such as the natural environment or legislative policy.21 More than one contributing factor or hazardous circumstance is typically involved in a patient safety incident. We will develop and use the contributing factors classification based on existing systems.28 29

Causation

Causation is the degree to which harm is judged to have been caused by healthcare management, rather than a disease process or injury. Although the GTT8 does not use a causation scale, we will apply a scale developed originally for the Californian Medical Indemnity Feasibility Study (MIFS)30 in the 1970s and the Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS)31 32 and subsequent studies. Other GTT studies have incorporated similar scales into their protocols.6 33 Box 6 shows the questions that will guide surveyors in determining the level of causation while box 2 shows the causation scale. The study will only include as AEs those scored between 4 and 6 for causation.

Box 6. Questions to guide surveyors to determine the level of causation30 32.

Is there a note in the medical record which indicates or suggests that healthcare management caused the injury?

Is there a note in the medical record which predicts the possibility of an injury from the patient's disease?

Does the timing of events suggest that the injury was related to the treatment?

Are there other reasonable explanations for the cause of the injury?

Was there an opportunity prior to the occurrence of the injury for intervention which might have prevented it?

Is there recognition that the intervention in question causes this kind of injury?

Did the AE respond to new management to neutralise or modify the effects of former management?

Prevention

Prevention is the degree to which an AE can be avoided.34 As with causation, the GTT8 does not use a prevention scale. We will use the MIFS/HMPS scale,30–32 following other GTT studies.6 17 33 35 36 Box 7 shows the questions which will guide surveyors in determining levels of prevention in the HMPS while box 3 shows the HMPS prevention scale.

Box 7. Questions to guide surveyors to determine the level of prevention30 32.

Is there consensus about diagnosis and therapy regarding this case?

How complex was the case?

Was the management in question appropriate?

What was the comorbidity of the case in which the AE occurred?

What was the degree of deviation of management from the accepted norm?

What was the degree of emergency in management of the case prior to the occurrence of the AE?

What potential benefit was associated with the management?

What was the chance of benefit associated with the management?

What was the risk of an adverse event related to the management?

On reflection, would a reasonable doctor or health professional do this again?

There is considerable potential for differing interpretations for both the causation and prevention scales when reviewing records as with any implicit MRR.37 We will implement robust quality assurance processes to limit discrepancies between data collectors by training, measuring inter-rater reliabilities and having regular review meetings (see component 7).

Level of outcome or severity

Patient outcomes relate to the impact on a patient which is wholly or partially attributable to an incident.20 These can be classified according to the type of harm, the degree of harm and any social and/or economic impact.20 The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC-MERP) scale will be used to score the outcome (box 4).38 This is the most frequently used outcome classification in studies using the GTT. Only categories E–I are related to harm and will be considered an AE (box 4).

Type of patient harm

The type of patient harm will be based on an existing patient safety classification which was developed from incidents and previous AE studies.28 The detailed classification is shown in online supplementary appendix A. The broad categories under clinical harm are pathophysiological/disease-related, injury, psychological/emotional distress, death and cardiorespiratory arrest. More than one category can be used for each AE.

Fields to measure AE rates

Depending on the healthcare practice type, different fields (‘denominator data’) will be collected to enable the AE rates to be calculated. For inpatients, the number of occupied bed days (OBDs) for that admission (component 7) will be collected. For non-inpatients (ie, records reviewed in general practice and specialists’ rooms), the denominator will be the number of consultations reviewed (component 7).

Component 4: undertake pilot study

Given the complexity of collecting data over a geographic area and the need to conduct 6000–8000 MRRs from at least three healthcare practice types, using three sets of triggers, a pilot study will be undertaken. The pilot study will assist in determining the types of issues that might be encountered in evaluating the selection of triggers, the data fields to be collected, the workflow and interpretation of definitions and criteria for both surveyors and reviewers, and the logistical and practical aspects of recruiting healthcare practices, accessing records and extracting, recording, storing and analysing data.

Component 5: recruit healthcare practices

Major tertiary children’s hospitals, general hospitals (metropolitan and regional), general practitioners, and specialist paediatricians and psychiatrists will be invited to participate in the research to allow MRRs to be undertaken.18

Component 6: recruit surveyors and reviewers

Two types of researchers are required to complete the final AE data set—‘surveyors’ and ‘medical AE reviewers’. Key selection criteria for both roles will be experience in clinical audit and MRR together with computer literacy. Nurses will be employed to simultaneously act as surveyors for this study and CTK part 2 (appropriateness).18 We estimate that eight full-time equivalent staff will be required. The selection process will involve an aptitude test using triggers and detection of AEs in artificially constructed medical records.26 27

Medical practitioners will be recruited as ‘medical AE reviewers’ to undertake a confirmation review of the information collected and recorded by the surveyor. Six doctors with paediatric experience and who fulfil the key selection criteria will be recruited.

The use of a single surveyor is a modification of the original GTT method8 which used two surveyors and one reviewer per MRR. While some GTT studies have used the original method,5 11 33 35 39 a variety of other models have been used including one surveyor and two reviewers,36 computerised screening,40 and one surveyor and one reviewer.23

Component 7: train and quality check data collectors and measure IRR

Details on educational interventions, instructions and teleconference supports to align rules and reduce variability between surveyors and medical AE reviewers are outlined in the CTK appropriateness protocol.18 Dual MRRs will be undertaken for a sample comparing findings to those of a CTK research team member.18 IRR will be measured at a number of points including between dual surveyor reviews for a sample, between surveyor and medical AE reviews with respect to whether an AE has occurred, incident type, and causation, prevention and outcome scores.

Component 8: undertake medical record reviews

MRRs will be conducted for a randomly selected hospital index admission. All general practice and specialist consultations undertaken during 2012 and 2013 will be reviewed. All available information relating to the index admission will be reviewed including discharge summaries and letters.8

If no triggers are detected, no further action will be taken by the surveyor and the review will be considered complete. If one or more triggers are detected, the surveyor will undertake an in-depth MRR to search for AEs. If a surveyor detects a potential AE, they will record all data fields outlined in component 3.

When a surveyor has recorded a potential AE, the web-based tool will electronically notify a medical AE reviewer (see component 3). The reviewer will then be able to securely enter the web-based tool, review the information supplied by the surveyor, and provide a determination as to the presence of an AE. For confirmed AEs, a medical AE reviewer will record incident type, and causation, prevention and outcome scores.

Component 9: analyse data

Data capture will be structured to allow identification of incident types (see component 3) and calculation of AE rates. CIs will be calculated and stratification will be undertaken by healthcare practice type.

The primary outcome measures for inpatients will be the number of AEs per 100 admissions, the percentage of admissions with an AE and the rate per 1000 OBDs. We are collecting all three measures to allow comparisons with other GTT studies as there is no consensus on which metric to use. The first two are likely to be more intuitive for the lay public and policymakers, while the latter is a more accurate indicator of risk exposure and may be more acceptable to clinicians. For general practices and specialists, the number of AEs per 100 consultations will be calculated. Secondary outcome measures will include scores for preventability, causation, contributing factors and outcomes (severity).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

Relevant Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) approvals have been secured and Site Specific Approvals will be sought and received prior to participant and healthcare practice recruitment and MRRs in all jurisdictions, authorities and health services. Single ethical review has been obtained from a lead HREC in each state in order to provide ethical approval for the hospitals within that state. The lead HRECs include: Sydney Children's Hospitals Network (15 NSW hospitals), Queensland Royal Children's Hospital (12 Qld hospitals) and Women's and Children's Hospital Network (8 SA hospitals). Site-specific approvals will be sought from each hospital. The Royal College of General Practitioners National Research and Ethics Evaluation Committee application is under review.

As part of the HREC application, we are proposing that patient and individual healthcare practice consent be waived as it complies with the NHMRC “Guidelines approved under Section 95A of the Privacy Act 1988”41 and the NHMRC Chapter 2.3.10 “Qualifying or waiving conditions for consent”.42 In summary, the study involves: minimal risk to healthcare practices and participants and cannot be achieved without access to records; with dispersed geographic regions across three states, the large number of healthcare practices and records (6000–8000), it is logistically difficult to obtain consent; information is retrospective and there is no likely reason patients would not consent; data are entered directly onto a database which will not contain personal information; and only aggregated data will be disseminated.

Statutory immunity

Statutory immunity protects from disclosure any identifying information obtained through an approved quality assurance activity.43 CTK has applied to the Federal (Commonwealth) Minister for Health for statutory immunity under Section VC of the Commonwealth Health Insurance Act 1973.

Dissemination

We will submit the results of the study to relevant national and international journals with the intention of publishing the results widely. Also, we will make national and international oral presentations to stakeholder groups including those involving patients, researchers, clinicians, managers and policymakers.

Discussion

A selection bias may be introduced as practices which agree to participate in the study may have a higher rate of participation in research, proactive audit and existing feedback processes. These factors may affect AE rates or the quality of AE documentation in the medical record. The use of a single reviewer to undertake the MRR may also be a limitation. Dual surveyor reviews and measurement of IRR will be undertaken to minimise this limitation.

In conclusion, this study will measure the frequency and types of AEs encountered in Australian paediatric care in a range of healthcare settings. There have been few large-scale studies of AEs undertaken in children's healthcare internationally, and none in Australia. This study will allow priorities to be set as to where improvement efforts are needed to reduce harm to children.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB and PDH initiated the project and led the NHMRC grant proposal. JB, AJ and LKW are chief investigators on the project; they led the design of the grant and shared in the development of the protocol and the initial drafting of the grant application and protocol. PDH, TDH and LKW are research team members who did the first drafting of the protocol manuscript. WBR, ARH, SEM, PL, GRW, HMW and SD are associate investigators, industry partners or members of the International Advisory Group who helped write the grant proposal, protocol and manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Grant APP1065898. It is led by the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University. The partners in the research are BUPA Health Foundation Australia (senior partner), Sydney Children's Health Network, NSW Kids and Families, Children's Health Queensland, the South Australian Department of Health, the University of South Australia (UniSA) and the NSW Clinical Excellence Commission.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee approvals have been received from the Sydney Children's Hospital Network, Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service and Women's and Children's Hospital Network (South Australia).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Measuring the quality of health care Donaldson MS, ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1999:3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW et al. The quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust 1995;163:458–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker RG, Norton PG, Flintoft V et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678–86. 10.1503/cmaj.1040498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Runciman WB et al. A comparison of iatrogenic injury studies in Australia and the USA. I: context, methods, casemix, population, patient and hospital characteristics. Int J Qual Health Care 2000;12:371–8. 10.1093/intqhc/12.5.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkendall ES, Kloppenborg E, Papp J et al. Measuring adverse events and levels of harm in pediatric inpatients with the Global Trigger Tool. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1206–14. 10.1542/peds.2012-0179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matlow AG, Baker GR, Flintoft V et al. Adverse events among children in Canadian hospitals: the Canadian Paediatric Adverse Events Study. CMAJ 2012;184:30 10.1503/cmaj.112153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michel P. Strengths and weaknesses of available methods for assessing the nature and scale of harm caused by the health system: literature review. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin FA, Resar RK. IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events. 2nd edn Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solevag AL, Nakstad B. Utility of a Paediatric Trigger Tool in a Norwegian department of paediatric and adolescent medicine. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005011 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman SM, Fitzsimons J, Davey N et al. Prevalence and severity of patient harm in a sample of UK-hospitalised children detected by the Paediatric Trigger Tool. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005066 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matlow AG, Cronin CMG, Flintoft V et al. Description of the development and validation of the Canadian Paediatric Trigger Tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:416–23. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharek PJ, Horbar JD, Mason W et al. Adverse events in the neonatal intensive care unit: development, testing, and findings of an NICU-focused trigger tool to identify harm in North American NICUs. Pediatrics 2006;118:1332–40. 10.1542/peds.2006-0565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S, Classen D, Larsen G et al. Prevalence of adverse events in pediatric intensive care units in the United States. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:568–78. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d8e405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lander L, Roberson DW, Plummer KM et al. A trigger tool fails to identify serious errors and adverse events in pediatric otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;143:480–6. 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.06.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Primary Care Trigger Tool—introduction 2013. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/primary_care_2/introductiontoprimarycaretriggertool.html

- 16.1000 Lives. Tools for improvement: how to use trigger tools. The Health Foundation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wet C, Bowie P. The preliminary development and testing of a global trigger tool to detect error and patient harm in primary-care records. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:176–80. 10.1136/pgmj.2008.075788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper TD, Hibbert PD, Mealing NM et al. CareTrack Kids—part 2 assessing the appropriateness of healthcare delivered to Australian children: a study protocol for a retrospective medical record review. BMJ Open 2015. In press. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiles LK, Hooper TD, Hibbert PD et al. CareTrack Kids—part 1 assessing the appropriateness of healthcare delivered to Australian children: a study protocol for clinical indicator development. BMJ Open 2015. In press. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Runciman WB, Edmonds MJ, Pradhan M. Setting priorities for patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:224–9. 10.1136/qhc.11.3.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Runciman W, Hibbert P, Thomson R et al. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:18–26. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation. The Paediatric Trigger Tool. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/paediatric_safer_care/the_paediatric_trigger_tool.html

- 23.Takata GS, Mason W, Taketomo C et al. Development, testing, and findings of a pediatric-focused trigger tool to identify medication-related harm in US children's hospitals. Pediatrics 2008;121:e927–35. 10.1542/peds.2007-1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharek PJ, Parry G, Goldmann D et al. Performance characteristics of a methodology to quantify adverse events over time in hospitalized patients. Health Serv Res 2011;46:654–78. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hibbert P, Williams H. The use of a global trigger tool to inform quality and safety in Australian general practice: a pilot study. Aust Fam Physician 2014;43:723–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt TD, Ramanathan SA, Hannaford NA et al. CareTrack Australia: assessing the appropriateness of adult healthcare: protocol for a retrospective medical record review. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. 10.5694/mja12.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Runciman WB, Williamson JAH, Deakin A et al. An integrated framework for safety, quality and risk management: an information and incident management system based on a universal patient safety classification. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15(Suppl 1):i82–90. 10.1136/qshc.2005.017467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman H, Castro G, Fletcher M et al. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:2–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills DH. Report on the Medical Insurance Feasibility Study. San Francisco, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R et al. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals: principal findings from a national survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med 1991;324:377–84. 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unbeck M, Muren O, Lillkrona U. Identification of adverse events at an orthopedics department in Sweden. Acta Orthop 2008;79:396–403. 10.1080/17453670710015319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson L, Pihl A, Tagsjo M et al. Adverse events are common on the intensive care unit: results from a structured record review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012;56:959–65. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB et al. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2124–34. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2010;363:2573] 10.1056/NEJMsa1004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas EJ, Lipsitz SR, Studdert DM et al. The reliability of medical record review for estimating adverse event rates. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:812–16. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Coordination Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. NCC MERP Index for Categorizing Medication Errors 2001.

- 39.Von Plessen C, Kodal AM, Anhoj J. Experiences with global trigger tool reviews in five Danish hospitals: an implementation study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001324 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brenner S, Detz A, López A et al. Signal and noise: applying a laboratory trigger tool to identify adverse drug events among primary care patients. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:670–5. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Guidelines approved under Section 95A of the Privacy Act 1988 Canberra, 2014. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/pr2_guidelines_under_s95a_of_the_privacy_act_140311.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (revised March 2014) Canberra, 2014. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/e72_national_statement_march_2014_140331.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Commonwealth Government. Health Insurance Act Part VC- (Quality Assurance Confidentiality). Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1973. [Google Scholar]