Abstract

Comparative genomic analyses have revealed that genes may arise from ancestrally non-genic sequence. However, the origin and spread of these de novo genes within populations remain obscure. We identified 142 segregating and 106 fixed testis-expressed de novo genes in a population sample of Drosophila melanogaster. These genes appear to derive primarily from ancestral intergenic, unexpressed open reading frames (ORFs), with natural selection playing a significant role in their spread. These results reveal a heretofore-unappreciated dynamism of gene content.

Although the vast majority of genes present in any species descend from a gene present in an ancestor, recent analyses suggest that some genes originate from ancestrally non-genic sequences (1–3). Evidence for these “de novo” genes has generally derived from a combination of phylogenetic and genomic/transcriptomic analyses that reveal evidence of lineage- or species-specific transcripts associated with non-genic orthologous sequences in sister species. De novo genes, which were first identified in Drosophila (1–3), have also been identified in human, rodents, rice and yeast (4–9). In Drosophila, de novo genes tend to be specifically expressed in tissues associated with male reproduction (2, 10), suggesting that sexual or gametic selection may be important (1–3, 9), though other functional roles may evolve (10, 11). Because previous studies of de novo gene evolution used comparative rather than population genetic approaches, the earliest steps in de novo gene origination remain mysterious. Here we use population genomic and transcriptomic data from Drosophila melanogaster and its close relatives to investigate the origin and spread of de novo genes within populations.

Illumina paired-end RNA-sequencing and de novo and reference guided approaches were used to characterize the testis transcriptome of six previously sequenced inbred Raleigh (RAL) D. melanogaster strains (12) ; an average of 65 million paired-end reads were produced for each strain (table S1). We inferred (13) the presence of 142 polymorphic de novo candidate genes expressed in at least one RAL strain but which are not known based on publicly available data from D. melanogaster. The median number of segregating de novo genes carried per strain was 49. RT-PCR and 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) in a subset of genes supported inferences from RNA-seq analysis (table S2). These candidate polymorphic genes correspond to unique, intergenic sequence in the D. melanogaster reference genome (table S3), are alignable to unique orthologous regions in the Drosophila simulans and Drosophila yakuba reference sequences, and show no significant BLASTP hits to the NCBI nr (non-redundant) protein database. The candidate genes exhibited expression neither in testis RNA-seq data from three D. simulans and two D. yakuba strains (table S1, fig. S1) nor in whole male and female RNA-seq data from 59 D. simulans strains (13). None of the candidates showed significant expression in whole females from the same D. melanogaster strains used for testis RNA-seq (table S4). These data support the hypothesis that the 142 candidates are new, male-specific, de novo genes still segregating in D. melanogaster. Expression levels of the candidate genes greatly exceed levels of background transcription in intergenic sequence (fig. S2, 13) and several additional attributes of these genes, as described below, support the hypothesis that the observed transcripts are biologically meaningful.

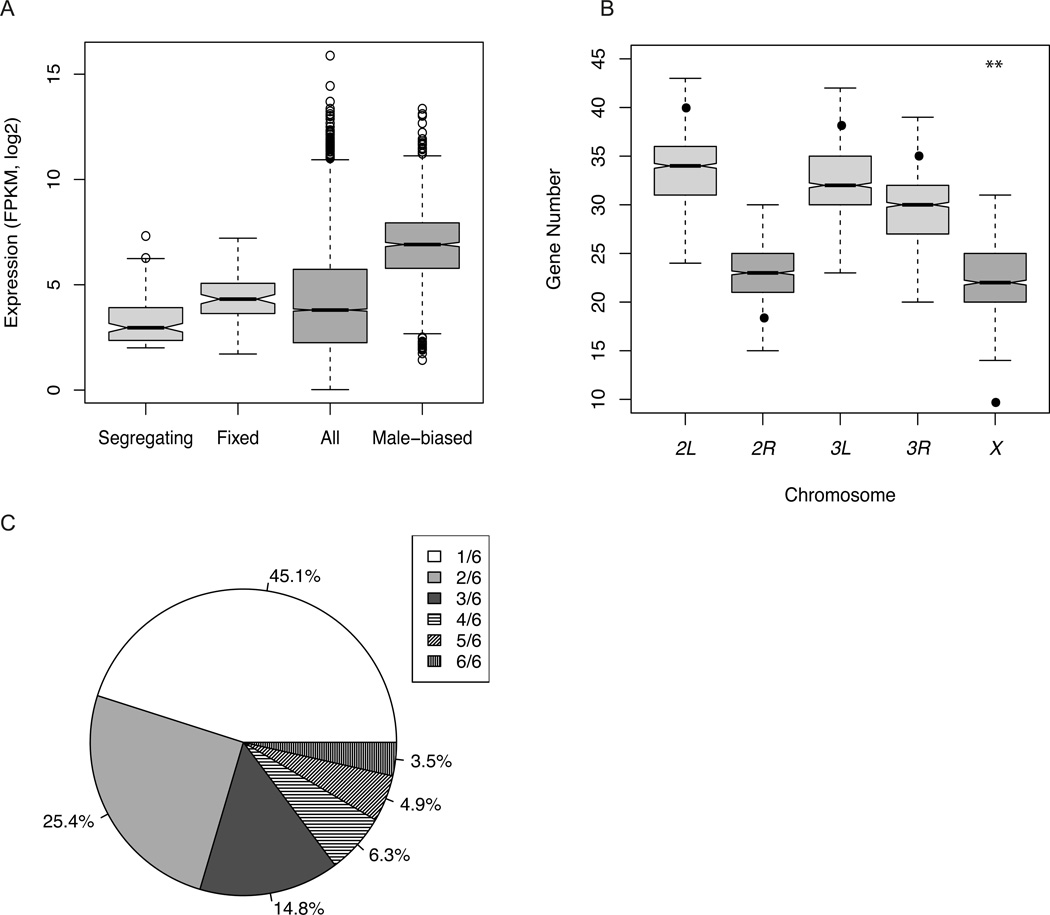

Segregating de novo genes were moderately expressed (Fig. 1A, Table 1), but showed significantly lower expression than annotated male-biased genes (13; Table 1) or annotated genes (Table S6). We observed no enrichment of polymorphic de novo genes near annotated male-biased genes and no significant correlation between the strand (+/−) of polymorphic de novo genes and that of their immediate annotated neighbors (χ2test p>0.1, table S5, fig S3, supported by simulations (13)). There was a marginally significant under-representation of X chromosome segregating de novo genes compared to annotated male-biased genes (10 genes are X-linked; t test, p=0.01; Fig. 1B). This result stands in contrast to speculation based on a small sample of older, fixed de novo genes (2, 3) that de novo male-biased genes are overrepresented on the X chromosome.

Fig.1.

Basic properties of segregating de novo genes. (A). Expression estimates of segregating de novo genes, fixed de novo genes, all annotated genes and annotated male-biased genes in D. melanogaster. (B). Simulation of de novo gene locations. The boxplot for each chromosome is the simulated number of genes from intergenic regions. The black dot is the observed number. The X chromosome is the only chromosome arm that deviates from the expected number of genes (t-test, p=0.01).(C). Pie chart of segregating de novo gene frequency.

Table 1.

Properties of segregating and fixed de novo genes and comparison with annotated male-biased genes in D. melanogaster.

| Segregating de novo genesa |

Fixed de novo genesb |

Male-biased genesc |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 142 | 106 | 1595 |

| Transcript length (bp) | 801 ns/*** | 1013 ** | 1184 |

| Exon length (bp) | 518 */*** | 512 *** | 355 |

| Exon number | 1.47 */*** | 1.79 * | 2.37 |

| Intron length (bp) | 91 */*** | 70.5 *** | 77 |

| 5' UTR length (bp) | 248 */*** | 267.5 *** | 170 |

| 3' UTR length (bp) | 364 ns/*** | 337 *** | 267 |

| Single-exon Gene (%) | 57 */*** | 48.1 *** | 35.8 |

| Expression (FPKM) | 7.78 ***/*** | 19.96 *** | 66.54 |

Wilcoxon test,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05, ns = not significant.

p-values are comparisons of segregating vs. fixed genes and segregating vs. male-biased genes.

p-values are comparisons of fixed de novo genes and male-biased genes. c: definition in (13). All estimates are medians, except for exon number (mean).

As expected, de novo genes were significantly shorter and simpler than annotated genes and annotated male-biased genes (Table 1, table S6). This pattern is likely due mostly to the larger proportion of polymorphic de novo genes that are single-exon (57.0%) compared to the proportion of annotated single-exon (table S6) or single-exon male-biased genes (Table 1, 13). Among the 61 multi-exon de novo genes the majority of splice events (98%) were associated with canonical sites; rare non-canonical splice sites were found in four genes as minor isoform splice events, which were similar to those previously observed in D. melanogaster (14). Alternative splicing was observed in 20 of the 61 multi-exon segregating de novo genes (table S7), with conserved reading frames across alternative isoforms. Genes associated with alternative splicing generally exhibited multiple isoforms across strains that expressed the corresponding gene with no evidence of genetic variation for alternative splice use.

Of 142 polymorphic genes, 134 (94%) had a minimum ORF of 150 bp (or greater) and were classified as potentially coding. To determine how likely the high proportion of genes harboring long ORFs is by chance we investigated the coding potential of intergenic regions in the reference sequence, focusing on single-exon ORFs. We observed that 59.9% of random 800 bp intergenic sequences were associated with a >=150 bp single-exon ORF, while of the observed single-exon de novo genes, 97.5% were associated with such an ORF (p<0.01). Moreover, the mean length of single-exon de novo gene ORFs was substantially greater than that expected in random intergenic sequence (p<0.05). These observations further support the idea that the observed transcripts are unlikely to be explained simply as random noise. The eight polymorphic de novo genes that did not satisfy our arbitrary minimum ORF criterion were autosomal and slightly smaller (mean transcript length=743 bp) than ORF-containing polymorphic genes. Orthologous sequences from expressing and non-expressing lines have similar coding potential, supporting the idea that most segregating de novo genes likely result from the recruitment of small, pre-existing, unexpressed ORFs (1). For D. simulans and D. yakuba orthologous sequences, 70% and 45%, respectively, contained ORFs similar to those observed for segregating genes in D. melanogaster. Of the 134 predicted de novo proteins, 41.8% may be intrinsically unfolded (fig. S4A–D) and 50% of these have predicted binding regions (fig. S4E); both observations are consistent with potential biological function (15). For putative protein-coding genes the average 5’- and 3’- UTR lengths (248 bp and 364 bp, respectively) were slightly shorter than the average lengths for annotated D. melanogaster genes but slightly longer than the averages for annotated male-biased genes (Table 1). The incidence of the two major polyadenylation signals (AAUAAA and AUUAAA) in or near the putative 3’-UTRs of segregating de novo genes was similar to, but slightly lower than, the incidence in the whole genome (table S8). Overall, polymorphic de novo genes have structural organization consistent with small protein-coding genes in the species.

Segregating de novo genes were either expressed at a relatively high level in expressing strains, or showed almost no evidence of expression in other strains. Hartigan’s dip test on transcript abundance estimates rejected unimodality for 134 of 142 genes, and was consistent with bimodal expression across lines for most genes. We used a cut-off of FPKM > 2 for inferring expression of a transcript in a line (16) to determine the proportion of strains, from 0.17 (1/6) to 1.0 (6/6), expressing each transcript. Because no candidates show expression in the reference sequence strain, the genes expressed in all six RAL strains are considered to be polymorphic in the species. Over half the genes (55%) were not rare in the Raleigh sample, as they were expressed in at least two of the six RAL strains (Fig. 1C); 29.5% were definitely common, being expressed in three or more strains, which is inconsistent with mutation-selection balance. We observed 106 unannotated male-specific transcripts expressed in all six strains and in the reference strain (table S9), but not in the outgroup strains. The corresponding “fixed” de novo genes were not included in downstream analyses relating to segregating genes.

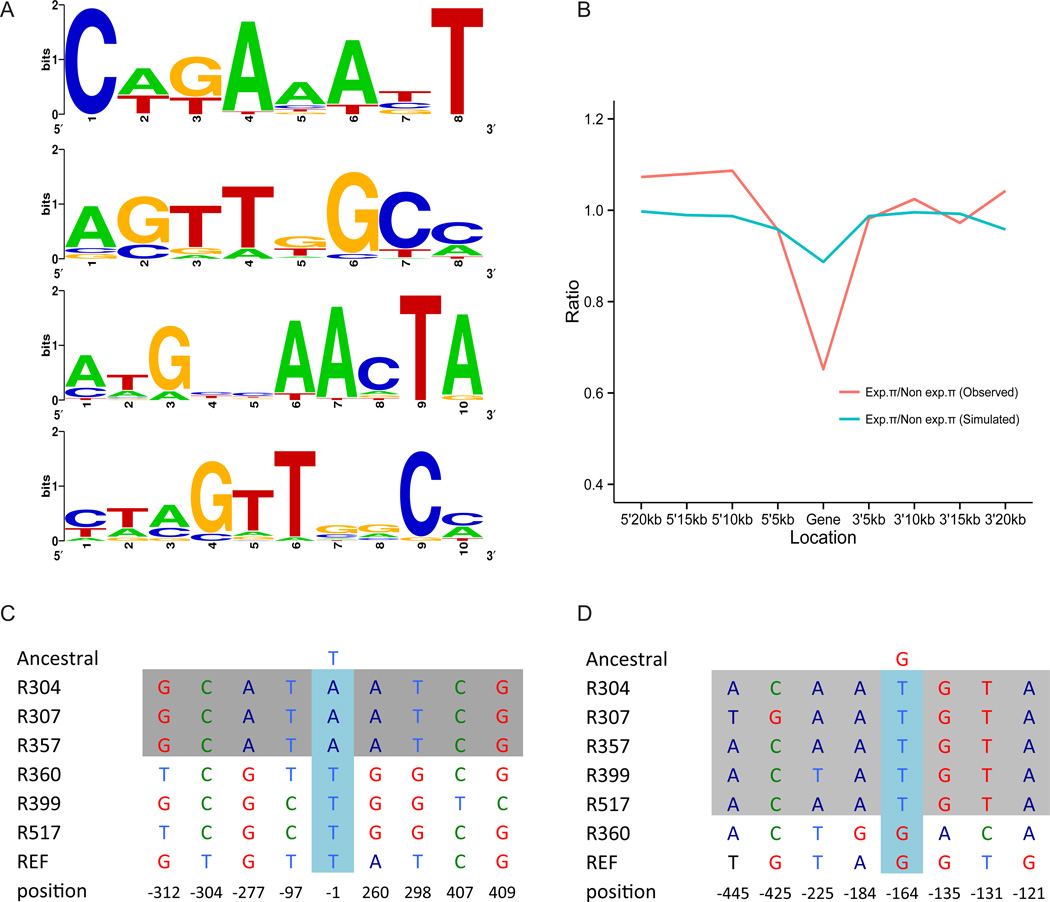

We extracted the 100 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of the inferred transcription start site (TSS) from the genome sequences of the expressing strains for each of the 61 multi-exon genes. MDscan identified and clustered motifs in these flanking sequences; sequence logos were then generated. We observed four common consensus sequence motifs (8 or 10 bp; Fig. 2A), each of which was found associated with roughly half the segregating de novo genes (13, table S10). In total, 371 annotated male-biased genes (23.3%) were also associated with at least one of these motifs, suggesting that the de novo genes share regulatory features with known male-biased genes. We identified 67 annotated male-biased genes (table S11) that have two or more motifs in the 5’ regions. However, GO (Gene Ontology) enrichment analysis (fig. S5) provided no insight into the possible functions of de novo genes. These data support the hypothesis that de novo gene expression is influenced by cis-acting variants in the regions corresponding to the 5’ flanking regions of expressing chromosomes. In the simplest case that de novo gene expression is due to a single non-coding nucleotide change, one would predict an excess of fixed differences between expressing and non-expressing chromosomes in flanking regions compared to random samples of intergenic sequences. We focused on the 32 genes expressed in more than two strains and for which our genetic analysis (13) supported cis-acting variation driving de novo gene expression. Of these genes, 31.2% exhibit a fixed, derived SNP within 500 bp upstream of the TSS while only 8.43% of simulated “genes” (intergenic regions defined by harboring derived SNPs with same frequency distribution as the 32 observed genes) exhibited a fixed SNP in the comparable 5’ region (p<0.01). More generally, divergence between expressing and non-expressing chromosomes for these 500 bp regions was significantly greater than divergence in simulated data (p=0.048), supporting the hypothesis that cis-regulatory changes play a role in de novo gene origination.

Fig. 2.

Regulation and population genetics of segregating de novo genes. (A). Potential cis-regulatory elements. The most common shared 8 bp and 10 bp consensus motifs in 5’–flanking regions are listed. From top to bottom, 34, 29, 25 and 30 multiple-exon genes show these motifs. (B). Nucleotide diversity (π for de novo genes and flanking regions. Red line: π expressing lines/π non-expressing lines; green line: expected values from re-sampling of intergenic DNA conditional on same derived allele frequency distribution as observed de novo genes. π estimates for 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of genes were incremented in 5kb windows. (C). A gene (Gene_X_141) that may have experienced a hard selective sweep. Grey box: expressed lines. The TSS region contains a derived allele fixed in expressing strains and absent in non-expressing strains; flanking regions are homozygous in expressing strains. (D). A gene (Gene_3L_079) showing no evidence of hard sweep. Grey box: expressing lines. In the TSS region there is a derived allele fixed in expressing lines but the flanking regions of expressing chromosomes retain nucleotide variation.

Under this hypothesis segregating genes should be associated with allele-specific expression. We thus measured allelic imbalance (17, 18) in the testis in a set of three unique F1 genotypes created by crossing the six RAL strains (table S1, 13). For the 59 autosomal genes for which one parent expressed the gene and the other did not, expression patterns in the heterozygote for 51 genes was explained completely by cis-acting variation (i.e., allelic imbalance was complete); 7 genes showed evidence of regulation by both cis-acting and trans-acting factors. Only of 1 of the 59 genes showed no evidence of allelic imbalance, consistent with expression driven solely by trans-acting variation (table S12). More generally, for genes expressed in both parents the expression of alleles in the F1 was consistent with expression levels in each parental line (table S13), further supporting the importance of cis-acting expression variants. The roughly bimodal expression patterns and the dominant role of cis-effects support the idea that the proportion of lines expressing a gene provides an estimate of its population frequency.

One population genetic explanation for polymorphic de novo genes is that singleton genes (45% of genes) are primarily deleterious and that higher frequency genes are primarily neutral. If the deleterious nature of de novo genes were due to the cost of transcription or translation, or from toxic interactions of the resulting RNAs or proteins with other molecules, then lower frequency genes should be more abundantly expressed and longer than higher frequency genes. However, contrary to this expectation, lower frequency genes were expressed at a lower level, were shorter, and were less complex than higher frequency genes (table S6, 13). The different properties of rare vs. common de novo genes (Table 2, 13) supports the idea that de novo genes having certain properties (e.g., greater expression, longer transcripts, more exons) are more likely to spread under selection.

Table 2.

Properties of segregating genes differ across frequency classes.

| Singletona | Non-singleton | Frequency >=3/6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FPKM | 5.76 ***/*** | 9.91 | 12.31 |

| Transcript length (bp) | 723 **/*** | 869 | 1312 |

| Exon number | 1.38 */** | 1.53 | 1.81 |

Wilcoxon test,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05.

p-values are comparison of : singleton vs. non-singleton and singleton vs. high frequency(>=3/6) genes. FPKM and transcript length estimates are medians; exon numbers are means.

We investigated the role of directional selection on polymorphic de novo genes by determining if they are associated with reduced nucleotide diversity (19, 20). For each de novo gene expressed in at least two strains we compared the nucleotide diversity (π) for expressed sequence (strains) vs. non-expressed orthologous sequence (non expressing strains) and compared the observed differences to a frequency-corrected expected value from re-sampling of intergenic sequence from the six RAL strains (13). For 46 of 65 genes π was lower in the expressed lines (mean=0.0060) than in the non-expressed lines (mean=0.0092) and exhibited a roughly 38% reduction compared to non-expressed orthologous sequence over the 65 genes (Wilcoxon test, p=0.003). For 30 genes, π was significantly lower in the expressed lines (Wilcoxon test, p<0.05). The region of reduced heterozygosity near expressed sequences is on the scale of 5–10 kb or less (Fig. 2B, fig. S6), which is counter to the expectation of strong selection on new mutations (19) but consistent with weaker selection (20) or soft sweeps (21) (Fig. 2C–2D). Polymorphic de novo genes were significantly (Wilcoxon test, p<0.001, 13) more likely to be differentially expressed between populations (29 of 142, or 17%) compared to annotated genes (4.5%) and male-biased genes (6.3%), which also supports the idea that selection may play a role in their spread.

We used the Hudson-Kreitman-Aguade-like (HKAl) test statistic (22, 23) to compare the ratio of heterozygosity-to-divergence for genomic regions associated with fixed de novo genes to that observed for appropriately sampled intergenic regions (13, 20). The HKAl for fixed regions (mean −0.48) was significantly smaller than that expected for comparable random intergenic regions (mean 0.12; Wilcoxon test, p<0.001). Moreover, regions corresponding to fixed genes associated with higher expression (FPKM>10) exhibited a smaller HKAl statistic compared to regions associated with fixed genes having lower (FPKM<=10) expression (HKAl −0.33 vs. –0.86; Wilcoxon test, p<0.001). These observations also support the hypothesis that de novo genes have been influenced by directional selection.

Overall, our analyses suggest that there are many polymorphic de novo male-specific genes in D. melanogaster populations, likely recruited by selection primarily from ancestral, unexpressed ORFs (fig. S7). Given the small number of genotypes investigated for a single tissue and our strict filtering criteria, we have likely substantially underestimated the number of polymorphic de novo genes. Our results also suggest the existence of many more fixed de novo D. melanogaster genes than previously inferred (2, 4, 10), which supports the idea that a substantial genetic component of male reproductive biology in this species remains completely unexplored. More generally, our results suggest that important attributes of an organism’s biology cannot be accurately represented or investigated without knowledge of de novo gene variation within species. In the absence of gene loss, de novo gene gain would lead to a long-term increase in gene number. While our analyses (13) are consistent with substantial numbers of polymorphic gene losses (13), we observed no population genetic support for directional selection (13). Thus, de novo genes may often spread under selection, while gene loss may occur primarily as a result of drift associated with loss of ancestral gene function. However, important details of such processes remain obscure and much additional work is required to clarify the dynamics, biochemical and genetic properties, and phenotypic effects of young de novo genes and the processes underlying gene loss in natural populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Begun lab for valuable comments, especially N. Svetec, J. Cridland, A. Sedghifar, T. Seher and Y. Brandvain. We also thank three anonymous reviewers and M.W. Hahn, C.H. Langley, J. Anderson and A. Kopp for comments and suggestions. We acknowledge Phyllis Wescott (1950–2011) for over 30 years of service in the Drosophila media kitchen at UC Davis. Funded by National Institutes of Health grant GM084056 to D.J.B. and National Science Foundation grant 0920090 to C.D.J and D.J.B. Author contribution: L.Z. and D.J.B conceived and designed the experiments, L.Z., P.S. and C.D.J. generated data, L.Z. performed data analysis, P.S. and L.Z. did molecular experiments, L.Z. and D.J.B. wrote the paper, L.Z., D.J.B and C.D.J revised the paper. Illumina reads produced in this study are deposited at NCBI BioProject under the accession number PRJNA210329.

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 to S17

References (24–58)

References and Notes

- 1.Begun DJ, Lindfors HA, Thompson ME, Holloway AK. Recently evolved genes identified from Drosophila yakuba and D. erecta accessory gland expressed sequence tags. Genetics. 2006;172:1675–1681. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.050336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine MT, Jones CD, Kern AD, Lindfors HA, Begun DJ. Novel genes derived from noncoding DNA in Drosophila melanogaster are frequently X-linked and exhibit testis-biased expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:9935–9939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509809103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begun DJ, Lindfors HA, Kern AD, Jones CD. Evidence for de novo evolution of testis-expressed genes in the Drosophila yakuba/Drosophila erecta Clade. Genetics. 2007;176:1131–1137. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Q, et al. On the origin of new genes in Drosophila . Genome Res. 2008;18:1446–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.076588.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowles DG, McLysaght A. Recent de novo origin of human protein-coding genes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1752–1759. doi: 10.1101/gr.095026.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao W, et al. A rice gene of de novo origin negatively regulates pathogen-induced defense response. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai J, Zhao R, Jiang H, Wang W. De novo origination of a new protein-coding gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 2008;179:487–496. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvunis AR, Rolland T, Wapinski I, Calderwood MA. Proto-genes and de novo gene birth. Nature. 2012;487:270–374. doi: 10.1038/nature11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinen TJAJ, Staubach F, Häming D, Tautz D. Emergence of a new gene from an intergenic region. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1527–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Zhang YE, Long M. New genes in Drosophila quickly become essential. Science. 2010;330:1682–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.1196380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reinhardt JA, et al. De novo ORFs in Drosophila are important to organismal fitness and evolved rapidly from previously non-coding sequences. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackay TFC, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature. 2012;482:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Supplementary materials for this article are available on Science Online. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheth N, et al. Comprehensive splice-site analysis using comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3955–3967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: a point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11:739–756. doi: 10.1110/ps.4210102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebenstreit D, et al. RNA sequencing reveals two major classes of gene expression levels in metazoan cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:497. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz D. Genetic control of alcohol dehydrogenase--a competition model for regulation of gene action. Genetics. 1971;67:411–425. doi: 10.1093/genetics/67.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graze RM, et al. Allelic imbalance in Drosophil a hybrid heads: exons, isoforms, and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1521–1532. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard Smith J, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet. Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan NL, Hudson RR, Langley CH. The “hitchhiking effect” revisited. Genetics. 1989;123:887–899. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermisson J, Pennings PS. Soft Sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics. 2005;169:2335–2352. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begun DJ, et al. Population genomics: whole-genome analysis of polymorphism and divergence in Drosophila simulans . Plos Biol. 2007;5:e310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langley CH, et al. Genomic variation in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster . Genetics. 2012;192:533–598. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.142018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark AG, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachtrog D, Thornton K, Clark A, Andolfatto P. Extensive introgression of mitochondrial DNA relative to nuclear genes in the Drosophila yakuba species group. Evolution. 2006;60:292–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature. 2010;463:311–317. doi: 10.1038/nature08696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graveley BR, et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster . Nature. 2010;471:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature09715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakaya HI, et al. Genome mapping and expression analyses of human intronic noncoding RNAs reveal tissue-specific patterns and enrichment in genes related to regulation of transcription. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smit A, Hubley R. R. RepeatModeler Open-1.0. 2008 (available at http://www.repeatmasker.org). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartigan JA, Hartigan PM. The dip test of unimodality. Ann Stat. 1985;13:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhn RM, et al. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D668–D673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warnes GR, Bolker B, Lumley T. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting. R package version. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu XS, Brutlag DL, Liu JS. An algorithm for finding protein-DNA binding sites with applications to chromatin-immunoprecipitation microarray experiments. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:835–839. doi: 10.1038/nbt717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia J-M, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Retelska D, Iseli C, Bucher P, Jongeneel CV, Naef F. Similarities and differences of polyadenylation signals in human and fly. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tusnády GE, Simon I. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cserzo M, Eisenhaber F, Eisenhaber B, Simon I. TM or not TM: transmembrane protein prediction with low false positive rate using DAS-TMfilter. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:136–137. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prilusky J, et al. FoldIndex: a simple tool to predict whether a given protein sequence is intrinsically unfolded. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3435–3438. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dosztányi Z, Mészáros B, Simon I. ANCHOR: web server for predicting protein binding regions in disordered proteins. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2745–2746. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Assis R, Zhou Q, Bachtrog D. Sex-biased transcriptome evolution in Drosophila . Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:1189–1200. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JAT. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nature Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanai I, et al. Genome-wide midrange transcription profiles reveal expression level relationships in human tissue specification. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:650–659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Meth. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Findlay GD, MacCoss MJ, Swanson WJ. Proteomic discovery of previously unannotated, rapidly evolving seminal fluid genes in Drosophila . Genome Res. 2009;19:886–896. doi: 10.1101/gr.089391.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindsley DL, Roote J, Kennison JA. Anent the genomics of spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster . PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smibert P, et al. Global patterns of tissue-specific alternative polyadenylation in Drosophila . Cell Reports. 2012;1:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang YE, Vibranovski MD, Landback P, Marais GAB, Long M. Chromosomal redistribution of male-biased genes in mammalian evolution with two bursts of gene gain on the X chromosome. Plos Biol. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews J, et al. Gene discovery using computational and microarray analysis of transcription in the Drosophila melanogaster testis. Genome Res. 2000;10:2030–2043. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.12.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gsponer J, Babu MM. Cellular strategies for regulating functional and nonfunctional protein aggregation. Cell Reports. 2012;2:1425–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 2000;41:415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.