Abstract

Bacterial persisters are phenotypic variants with an extraordinary capacity to tolerate antibiotics, and they are hypothesized to be a main cause of chronic and relapsing infections. Recent evidence has suggested that the metabolism of persisters can be targeted to develop therapeutic countermeasures; however, knowledge of persister metabolism remains limited due to difficulties associated with isolating these rare and transient phenotypic variants. By using a technique to measure persister catabolic activity, which is based on the ability of metabolites to enable aminoglycoside (AG) killing of persisters, we investigated the role of seven global transcriptional regulators (ArcA, Cra, cyclic AMP [cAMP] receptor protein [CRP], DksA, FNR, Lrp, and RpoS) on persister metabolism. We found that removal of CRP resulted in a loss of AG potentiation in persisters for all metabolites tested. These results highlight a central role for cAMP/CRP in persister metabolism, as its perturbation can significantly diminish the metabolic capabilities of persisters and effectively eliminate the ability of AGs to eradicate these troublesome bacteria.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial persisters are phenotypic variants that are highly tolerant to antibiotics (1). It is believed that they are a main culprit of the proclivity of biofilm infections to relapse, which imposes a substantial burden on the health care system (2, 3). When a bacterial population is treated with bactericidal antibiotics, biphasic killing is observed, where the death of normal cells is characterized by an initial, rapid killing rate, and the presence of persisters is illuminated by a second regime with a much lower rate of cell death (4, 5). When these survivors are recultured, the resulting population exhibits antibiotic sensitivity identical to that of the original culture, demonstrating that persisters are not antibiotic-resistant mutants but phenotypic variants (1, 5, 6).

While persisters largely arise from dormant subpopulations (2, 4, 7, 8), recent studies have demonstrated that they remain metabolically active, with the capacity to catabolize specific carbon sources and generate proton motive force through respiration (9, 10). This metabolic activity, specifically, proton motive force generation, enables aminoglycoside (AG) transport into cells that results in killing of persisters, and several enzymes needed for this process have been identified (9, 10). Knowledge of the enzymes and metabolic pathways present in persisters, as well as how they can be altered, could prove useful for the development of antipersister therapies. A fundamental question in this regard is, what are the cellular components responsible for defining the metabolic network in persisters? Due to the strong dependence of metabolism on transcriptional regulation (11, 12), the goal of this study was to determine the importance of several global transcriptional regulators to persister metabolism. To do this, we measured catabolic activity in persisters from ΔarcA, Δcra, Δcrp, ΔdksA, Δfnr, Δlrp, and ΔrpoS mutants and discovered that cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP) along with its metabolite cofactor, cyclic AMP, which is synthesized by CyaA, are critical regulators of persister metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All strains were derived from Escherichia coli MG1655. Standard P1 phage transduction was employed to transfer sequences with the genetic deletions (ΔarcA, Δcra, Δcrp, ΔdksA, Δfnr, Δlrp, and ΔrpoS) from the Keio Collection to E. coli MG1655 (13). The kanamycin resistance gene (kan) was removed from these strains using FLP recombinase, when required (14). To complement Δcrp and ΔcyaA, the native promoters and genes were amplified from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA using primers 5′-CTAGTAGCTCGAGTTTTGCTACTCCACTGCGTC-3′ and 5′-GCATCATCCTGCAGGTTAACGAGTGCCGTAAACGA-3′ for crp and primers 5′-CTAGTAGCTCGAGAGTGTGCCTGCCAGAGTGCA-3′ and 5′-GCATCATCCTGCAGGTCACGAAAAATATTGCTGTA-3′ for cyaA. The amplified genes were digested with XhoI and SbfI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and cloned into pUA66 (15). All gene deletion and cloning constructions were confirmed by colony PCR and/or DNA sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ).

Chemicals, media, and growth conditions.

All chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich. LB medium (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter NaCl) and LB agar (LB medium plus 15 g/liter agar) were prepared from the components and autoclaved at 121°C for 30 min to achieve sterilization. LB medium and LB agar were used for planktonic growth measurement and measurement of the number of CFU, respectively. For mutant selection, 50 μg/ml kanamycin (KAN) and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol (CM) were used. For persister assays and AG potentiation assays, 5 μg/ml ofloxacin (OFL) and 10 μg/ml gentamicin (GENT) were used, respectively. To inhibit cytochrome activity during AG assays, 5 mM potassium cyanide (KCN) was used. CM stock solution (25 mg/ml) was dissolved in ethanol, whereas GENT (10 mg/ml), KCN (1 mM), KAN (50 mg/ml), and OFL (5 mg/ml) stock solutions were dissolved in deionized (DI) H2O. The OFL stock solution was titrated with 1 M sodium hydroxide until the OFL fully dissolved. To prepare 1.25× M9 salt solution, 2.5 ml of 1 M MgSO4 and 125 μl of 1 M CaCl2 were first mixed with 747.5 ml DI H2O, and then 250 ml of 5× M9 salt solution (33.9 g/liter dibasic sodium phosphate, 15 g/liter monobasic potassium phosphate, 5 g/liter ammonium chloride, 2.5 g/liter sodium chloride) that had been autoclaved at 121°C for 30 min was added. Carbon sources (glucose, glycerol, fructose, mannitol, gluconate, succinate, pyruvate, arabinose, fumarate, lactose, and acetate) were dissolved in DI H2O to prepare stock solutions (600 mM carbon). The 1.25× M9 salt solution, KCN, CM, GENT, OFL, and carbon source stock solutions were filter sterilized with 0.22-μm-pore-size filters. Overnight cultures were inoculated from −80°C frozen stocks stored in 25% glycerol and grown in 2 ml of LB medium in a test tube at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 24 h.

Persister assay.

Following overnight growth, cultures were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 in 1 ml of fresh LB medium in a test tube and immediately treated with 5 μg/ml of OFL. At the desired time points, 100-μl samples were collected from antibiotic-treated cultures and mixed with 900 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in microcentrifuge tubes, and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 3 min. To dilute the antibiotic concentration, 900 μl of supernatant was removed and the cell pellets were resuspended with 900 μl of PBS. This procedure was repeated until the antibiotic concentration was below the MIC. We have previously demonstrated that the MIC for MG1655 was 0.075 to 0.15 μg/ml OFL (7). After washing the cells, cell pellets were resuspended in the remaining 100 μl of PBS. Then, 10 μl of sample from each cell suspension was added into 90 μl PBS in a 96-well round-bottom plate and serially diluted. Ten microliters of each dilution was spotted on LB agar plates, which were then incubated at 37°C for 16 h before the numbers of CFU were counted. For each spot, 10 to 100 colonies were counted.

Aminoglycoside potentiation assay.

After 5 h of OFL treatment, cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1 ml of 1.25× M9 salt solution. The cells were washed again in 1 ml of 1.25× M9 salt solution to remove the antibiotic and residual LB medium, and the cell concentrations were adjusted such that the final concentration was ∼105 persisters/ml. To enumerate the CFU in the cell suspension, 10 μl of sample was serially diluted and plated on LB agar. Then, 80 μl of cell suspension, 10 μl of GENT solution (100 μg/ml), and 10 μl of carbon source solution (600 mM) were mixed in each well of 96-well flat-bottom plates, resulting in ∼104 persisters, 10 μg/ml GENT, and 60 mM carbon per well. For the no-carbon-source control, 10 μl of DI H2O was added instead of a carbon source. To inhibit cellular respiration, 50 mM KCN was added to the GENT stock solution, and 10 μl of this mixture was mixed with 80 μl of cell suspension and 10 μl of carbon source solution, thus introducing 5 mM KCN in each well. Sample plates were sealed with sterile, gas-permeable Breathe-Easy membranes and incubated at 37°C and 250 rpm for 2 h. After incubation, 100 μl cell culture from each well was transferred to microcentrifuge tubes with 900 μl of PBS. Cells were pelleted at 15,000 rpm for 3 min, and 900 μl of supernatant was removed. This washing step was repeated twice to dilute the GENT concentration so that it was below its MIC (16). After washing the cells, cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of the remaining supernatant, and 10 μl of samples was serially diluted and plated on LB agar. The remaining 90 μl of samples was also plated on LB agar to improve the limit of detection. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h, and the numbers of CFU were counted.

Gentamicin sensitivity assay.

E. coli MG1655 Δcrp and E. coli MG1655 ΔcyaA were inoculated from −80°C frozen stocks stored in 25% glycerol into 2 ml of LB medium. Cells were grown for 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 4 h before being diluted in 2 ml of M9 salt solution with 10 mM glucose (M9-glucose) and grown for 16 h. Cells were diluted into 25 ml of M9-glucose to an OD600 of 0.01 and cultured for 6 h until they reached exponential phase. One hundred microliters of each culture was removed, serially diluted, and plated to enumerate the CFU prior to GENT treatment. The remaining cells were then treated with 10 μg/ml of GENT for 2 h. One milliliter of sample was removed from each culture, and the samples were pelleted, washed, serially diluted, and plated as described above. The plates were incubated for 16 h before the numbers of CFU were counted.

Statistical analysis.

Three biological replicates were performed for each experimental condition, and a two-tailed t test was performed for pairwise comparisons. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant, and each data point is represented by the mean value ± standard error.

RESULTS

Screen of transcriptional regulator mutants to identify those that are critical for metabolite-enabled AG potentiation in persisters.

Due to their low abundance, transient nature, and similarities to cells of the more highly abundant viable but nonculturable cell (VBNC) phenotype, highly pure persister samples have yet to be isolated (10). In the absence of such methods, we developed an approach to measure metabolic activity in persisters that utilizes the phenomenon of metabolite-enabled aminoglycoside (AG) potentiation (9). In brief, AG uptake is dependent on proton motive force, and therefore, this drug class has an impaired ability to kill deenergized cells (9). The vast majority of persisters are dormant (7), and within such a state AGs are ineffective (9). In previous work, we discovered that specific metabolites produce AG killing of persisters and that such potentiation is dependent on catabolism of the substrate to generate proton motive force through respiration (9, 10). This study demonstrated that persisters are metabolically active, and we have since shown that the assay can be used to measure the metabolism of persisters from antibiotic-treated cultures. Notably, the approach circumvents the need to segregate persisters from other cell types, because within antibiotic-treated populations that have reached the second regime of biphasic killing, the only cells that remain culturable are persisters. Therefore, survival data from samples treated with an AG with or without a metabolite can be used to infer persister catabolism (10). Using this assay, we analyzed the impacts of ΔarcA, Δcra, Δcrp, ΔdksA, Δfnr, Δlrp, and ΔrpoS on the ability of persisters to consume carbon sources and generate proton motive force aerobically. We focused on these transcriptional regulators due to their systems-level roles in regulating metabolism and our overall goal to identify the molecular mediators responsible for establishing the persister metabolic network. Collectively, these seven global regulators govern diverse aspects of E. coli metabolism: CRP and Cra participate in controlling the expression of many enzymes, including those within central metabolism; Lrp is involved in regulating amino acid metabolism; ArcA and FNR coordinate control of aerobic and anaerobic respiration; and RpoS and DksA are regulators of the general stress and stringent responses, respectively (17–24). Prior to measuring persister catabolism, we verified that 5 h of ofloxacin treatment was sufficient to enumerate persisters within cultures of the wild type and the seven deletion strains (Fig. 1). Persisters were then subjected to the AG potentiation assay, where samples were washed, resuspended in M9 medium, and exposed to a panel of 11 carbon sources (60 mM carbon) in the presence of 10 μg/ml gentamicin (GENT) (Fig. 2A). To quantify the level of GENT potentiation that was metabolite independent, a no-carbon-source control was included. We also included controls where samples were treated with 5 mM KCN, in addition to carbon sources and GENT, to confirm that persister killing was consistent with the mechanism of AG potentiation identified previously (10) (Fig. 2B to I).

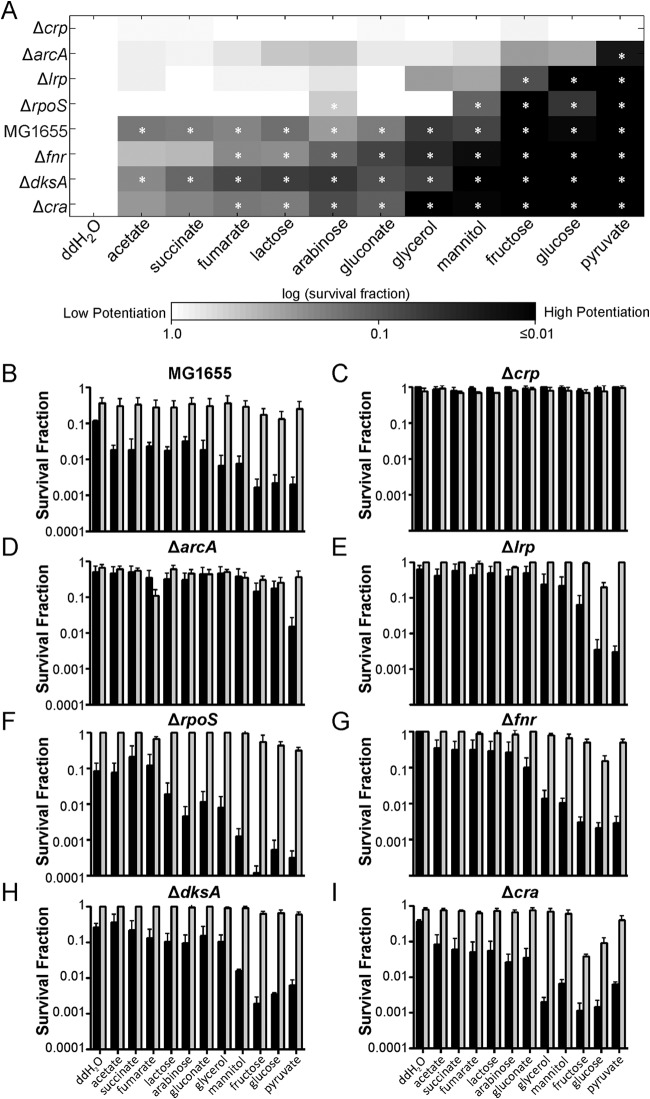

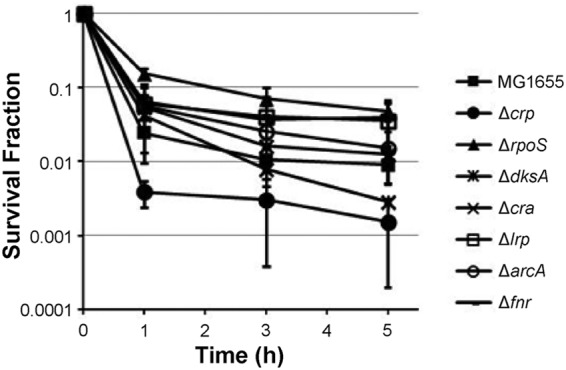

FIG 1.

Enumeration of persisters in the wild type and mutants with deletion of transcriptional regulators. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in fresh LB medium and treated with 5 μg/ml OFL. CFU levels were monitored for 5 h during treatment, and survival fractions were determined by dividing the CFU counts at each time point by that at time zero.

FIG 2.

Aminoglycoside potentiation assays in persisters and mutants. (A) Persisters were treated with GENT (10 μg/ml) and carbon sources (normalized to 60 mM carbon) in M9 minimal medium for 2 h. After AG treatment, the persister survival fraction was calculated from the numbers of CFU present in the original culture and after carbon source and GENT treatment. The survival fraction of each strain and treatment condition was normalized to that for the no-carbon-source (DI H2O; double-distilled water [ddH2O] in the figure) control of the same strain. *, statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) by comparison of each carbon source-treated sample and the no-carbon-source control for each strain. (B to I) Survival fractions of E. coli MG1655 and its global regulator deletion strains after being treated with GENT and carbon sources (black bars) or GENT, carbon sources, and 5 mM KCN (gray bars).

Results from this screen demonstrated that, with the exception of the Δcrp mutant, glucose, fructose, and pyruvate strongly potentiated AG killing in the persisters examined. In most cases, the survival fraction of persisters treated with these three carbon sources decreased by 100-fold or more. Upon inhibiting the electron transport chain with KCN, AG potentiation was significantly reduced in all samples. From this screen, we found that the panel of carbon sources tested could not potentiate the AG killing of persisters derived from the Δcrp mutant, suggesting an essential role for CRP in establishing the metabolic network of persisters.

CRP is a key regulatory protein in persister metabolism.

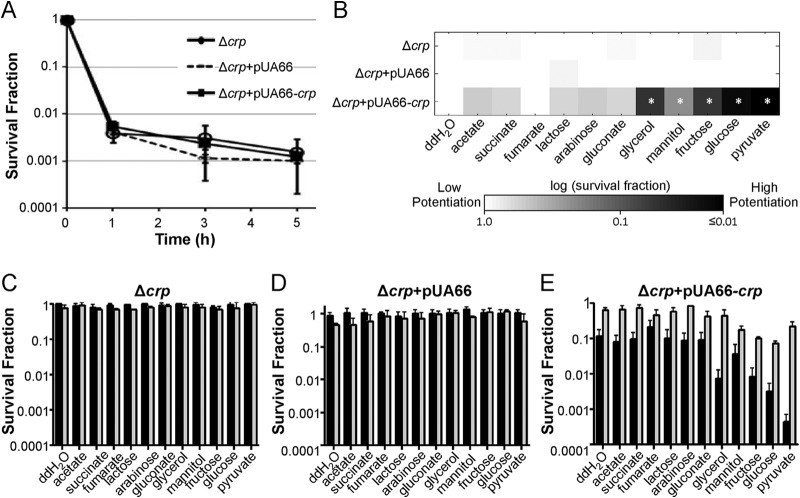

Results from the screen demonstrated that the deletion of crp, encoding the cAMP receptor protein, eliminated the ability of metabolites to stimulate AG killing of persisters. To confirm that the reduction in potentiation was due to the loss of CRP, we cloned crp under the control of its native promoter into pUA66, a low-copy-number vector, to produce pUA66-crp. When persisters were enumerated in the Δcrp mutant with pUA66-crp and the Δcrp mutant with pUA66 (empty control plasmid), the persister abundances were comparable to the abundance for the Δcrp mutant (Fig. 3A). We then examined the effect of crp complementation on carbon source metabolism and AG potentiation, and we found that pUA66-crp restored metabolic stimulation of AG killing in the Δcrp mutant, whereas pUA66 did not (Fig. 3B to E). Similar to the findings for the Δcrp mutant, a loss of CFU was not detected in the Δcrp mutant with pUA66, demonstrating that the vector did not interfere with carbon source consumption or AG sensitivity.

FIG 3.

Complementation of the Δcrp mutant. (A) Persister levels of the Δcrp mutant, the Δcrp mutant with pUA66 (empty vector), and the Δcrp mutant with pUA66-crp were monitored for 5 h during OFL treatment. (B) Persisters were treated with GENT (10 μg/ml) and carbon sources (60 mM carbon) in M9 minimal medium for 2 h. The persister survival fraction for each data point was normalized to that for the no-carbon-source (DI H2O; double-distilled water [ddH2O] in the figure) control. *, statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) by comparison of each carbon source-treated sample and the DI H2O control for each strain. (C to E) Survival fractions of E. coli MG1655 Δcrp (C), Δcrp with pUA66 (D), and Δcrp with pUA66-crp (E) after being treated with GENT and carbon sources (black bars) or GENT, carbon sources, and 5 mM KCN (gray bars).

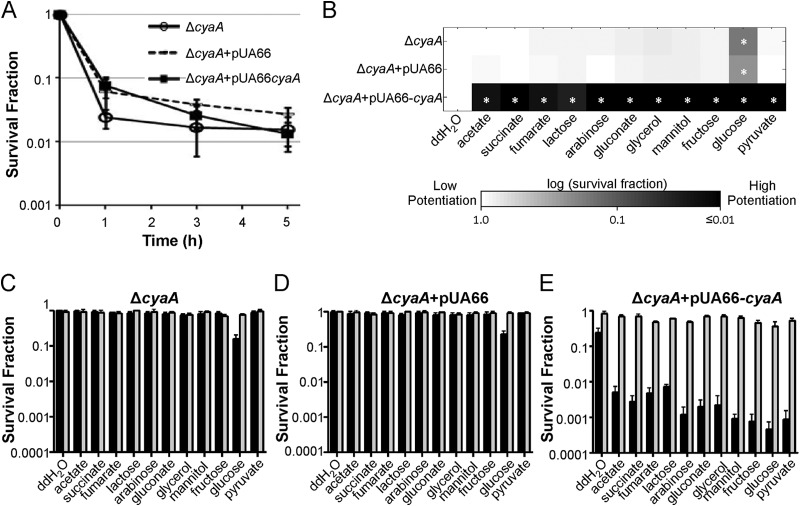

Since CRP activates catabolic gene expression when it is bound to cAMP, which is synthesized by adenylate cyclase encoded by cyaA, we generated a ΔcyaA mutant and its complementation strains and assessed both persister levels and carbon source consumption. Persister levels within the ΔcyaA mutant, the ΔcyaA mutant with pUA66, and the ΔcyaA mutant with pUA66-cyaA were found to be comparable (Fig. 4A), whereas ΔcyaA, much like Δcrp, resulted in a broad reduction in the array of carbon sources that persisters could consume to potentiate AG activity (Fig. 4B to E). In addition, pUA66-cyaA, but not the control plasmid (pUA66), restored carbon source consumption to persisters.

FIG 4.

Complementation of the ΔcyaA mutant. (A) Persister levels of the ΔcyaA mutant, the ΔcyaA mutant with pUA66 (empty vector), and the ΔcyaA mutant with pUA66-cyaA were monitored for 5 h during OFL treatment. (B) Persisters were treated with GENT (10 μg/ml) and carbon sources (normalized to 60 mM carbon) in M9 minimal medium for 2 h. The persister survival fraction for each data point was normalized to that for the no-carbon-source (DI H2O; double-distilled water [ddH2O] in the figure) control. *, statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) by comparison of each carbon source-treated sample and the DI H2O control for each strain. (C to E) Survival fractions of E. coli MG1655 ΔcyaA (C), ΔcyaA with pUA66 (D), and ΔcyaA with pUA66-cyaA (E) after being treated with GENT and carbon sources (black bars) or GENT, carbon sources, and 5 mM KCN (gray bars).

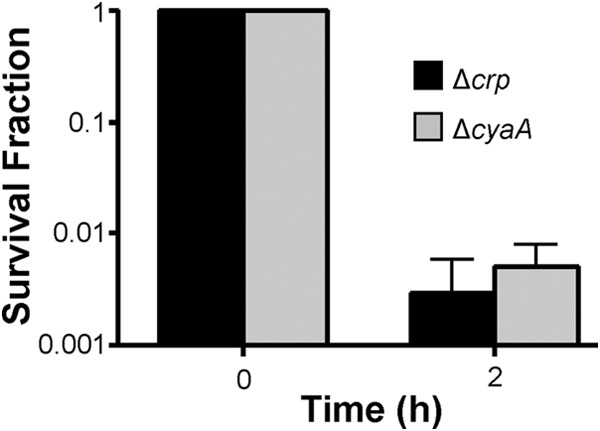

We note that E. coli isolates lacking crp or cyaA may exhibit increased tolerance toward AG (25–27). To ensure that the reduction in metabolite-enabled AG killing observed in the Δcrp and ΔcyaA mutants was due to alterations in persister metabolism rather than an inability of AGs to kill these mutants, we assessed whether GENT could kill the Δcrp and ΔcyaA mutants in M9 minimal medium, which was the medium used for the AG potentiation assays. As depicted in Fig. 5, GENT could kill >99.5% of the Δcrp and ΔcyaA mutants (>100-fold reductions in CFU levels) within 2 h, which was the length of time used in AG potentiation assays. This demonstrated that the Δcrp and ΔcyaA mutants could be killed with the AG, medium, and time scale used in the persister catabolism assays, confirming that the lack of killing observed in Δcrp and ΔcyaA persisters was not due to AG tolerance but, rather, was due to a phenotypic inability to consume metabolites and potentiate AGs.

FIG 5.

Sensitivity of E. coli MG1655 Δcrp and MG1655 ΔcyaA to GENT. The two strains were inoculated in M9-glucose to an OD600 of 0.01 and propagated for 6 h to exponential phase before being treated with 10 μg/ml of GENT for 2 h. The survival fraction was determined from the CFU counts at time zero and 2 h of GENT treatment.

DISCUSSION

Metabolism has been emerging as a key modulator of persistence (5, 28). Recent studies have demonstrated that metabolic stresses are important sources of persisters in both planktonic cultures and biofilms (29–34). In fact, persistence can be regarded as a metabolic program, where shutdown of metabolic processes participates in entry into this quasidormant state, metabolic activity during stasis maintains viability, and reactivation of metabolism is required for reawakening and growth after the conclusion of antibiotic treatment. The importance of metabolism is further highlighted by the discovery of antipersister strategies which depend on metabolic stimulation in persisters (9, 35–38). These findings advocate for the need for greater understanding of persister metabolism. Unfortunately, measurement of persister metabolic activities with standard methods is not currently possible, due to inabilities associated with the isolation of persisters (10, 39, 40). However, with the AG potentiation assay we are able to measure persister metabolism even in the presence of other cell types, such as VBNCs, because the method deduces metabolic activity from culturability data, and the defining characteristic of persistence is the retention of culturability following prolonged antibiotic treatment (10). In addition, the AG potentiation assay not only identifies the carbon sources that persisters consume to drive proton motive force generation but also simultaneously identifies the metabolite adjuvants to be used with AGs to kill persisters, which is important information that is therapeutically relevant (10).

With the AG potentiation assay, we directly assessed the contribution of a set of global transcriptional regulators to persister metabolism. We focused on these regulators, because we sought to identify the cellular components responsible for defining the metabolic network in persisters and transcriptional regulation has been found to play a pivotal role in metabolism (11, 12). Deletion of any of the seven global regulators in our initial screen did not significantly alter the stationary-phase persister levels, which is consistent with previous observations (41). Interestingly, we found that Δcrp and ΔcyaA persisters consumed a narrower panel of carbon sources than wild-type E. coli. CRP and CyaA are two key players in catabolite repression/activation, regulating the hierarchy of carbon source usage across diverse lineages of bacteria. In E. coli, their vast regulon consists of 188 genes, and they have been shown to play a role in a plethora of cellular processes, including persister formation (31, 42–44). Here, our results have now identified CRP and CyaA to be critical regulators of persister metabolism.

When cellular concentrations of preferred carbon sources, such as glucose, are low, CyaA is activated, resulting in the synthesis and accumulation of cAMP. The binding of cAMP to CRP enables it to activate genes for the catabolism of secondary carbon sources. The results presented here suggest that catabolic regulation remains active in persisters, and the absence of either CRP or CyaA has widespread effects on their metabolic networks. In particular, the ability of persisters to catabolize many substrates is lost in Δcrp and ΔcyaA mutants, thereby suggesting two mutational routes that E. coli could use to avoid AG killing of persisters. Alternatively, synthetic activation of CRP represents one possible route to improve killing of persisters with AGs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Department of the Army under award number W81XWH-12-2-0138 and NIAID of NIH under award number R21AI105342.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We thank the National BioResource Project (National Institute of Genetics, Japan) for its support of the distribution of the Keio Collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis K. 2010. Persister cells. Annu Rev Microbiol 6:357–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis K. 2007. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauvart M, De Groote VN, Michiels J. 2011. Role of persister cells in chronic infections: clinical relevance and perspectives on anti-persister therapies. J Med Microbiol 60:699–709. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.030932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. 2004. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science 305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amato SM, Fazen CH, Henry TC, Mok WWK, Orman MA, Sandvik EL, Volzing KG, Brynildsen MP. 2014. The role of metabolism in bacterial persistence. Front Microbiol 5:70. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin BR, Concepción-Acevedo J, Udekwu KI. 2014. Persistence: a copacetic and parsimonious hypothesis for the existence of non-inherited resistance to antibiotics. Curr Opin Microbiol 21:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orman MA, Brynildsen MP. 2013. Dormancy is not necessary or sufficient for bacterial persistence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3230–3239. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00243-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fridman O, Goldberg A, Ronin I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. 2014. Optimization of lag time underlies antibiotic tolerance in evolved bacterial populations. Nature 513:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison KR, Brynildsen MP, Collins JJ. 2011. Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 473:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orman MA, Brynildsen MP. 2013. Establishment of a method to rapidly assay bacterial persister metabolism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4398–4409. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00372-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil KR, Nielsen J. 2005. Uncovering transcriptional regulation of metabolism by using metabolic network topology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2685–2689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406811102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madan Babu M, Teichmann SA. 2003. Evolution of transcription factors and the gene regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1234–1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaslaver A, Bren A, Ronen M, Itzkovitz S, Kikoin I, Shavit S, Liebermeister W, Surette MG, Alon U. 2006. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat Methods 3:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews JM. 2001. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother 48:5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fic E, Bonarek P, Gorecki A, Kedracka-Krok S, Mikolajczak J, Polit A, Tworzydlo M, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Wasylewski Z. 2009. cAMP receptor protein from Escherichia coli as a model of signal transduction in proteins—a review. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 17:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000178014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorke B, Stulke J. 2008. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarkar D, Siddiquee K, Araúzo-Bravo M, Oba T, Shimizu K. 2008. Effect of cra gene knockout together with edd and iclR genes knockout on the metabolism in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol 190:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brinkman AB, Ettema TJG, De Vos WM, Van Der Oost J. 2003. The Lrp family of transcriptional regulators. Mol Microbiol 48:287–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park DM, Akhtar MS, Ansari AZ, Landick R, Kiley PJ. 2013. The bacterial response regulator ArcA uses a diverse binding site architecture to regulate carbon oxidation globally. PLoS Genet 9:e1003839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salmon K, Hung S-P, Mekjian K, Baldi P, Hatfield GW, Gunsalus RP. 2003. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12. The effects of oxygen availability and FNR. J Biol Chem 278:29837–29855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Battesti A, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. 2011. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown L, Gentry D, Elliott T, Cashel M. 2002. DksA affects ppGpp induction of RpoS at a translational level. J Bacteriol 184:4455–4465. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4455-4465.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Höltje JV. 1978. Streptomycin uptake via an inducible polyamine transport system in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem 86:345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancock R, Bell A. 1988. Antibiotic uptake into gram-negative bacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 7:713–720. doi: 10.1007/BF01975036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girgis HS, Hottes AK, Tavazoie S. 2009. Genetic architecture of intrinsic antibiotic susceptibility. PLoS One 4:e5629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prax M, Bertram R. 2014. Metabolic aspects of bacterial persisters. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:148. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernier SP, Lebeaux D, DeFrancesco AS, Valomon A, Soubigou G, Coppée J-Y, Ghigo J-M, Beloin C. 2013. Starvation, together with the SOS response, mediates high biofilm-specific tolerance to the fluoroquinolone ofloxacin. PLoS Genet 9:e1003144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amato SM, Brynildsen MP. 2014. Nutrient transitions are a source of persisters in Escherichia coli biofilms. PLoS One 9:e93110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amato SM, Orman MA, Brynildsen MP. 2013. Metabolic control of persister formation in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell 50:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, McKay G, Siehnel R, Schafhauser J, Wang Y, Britigan BE, Singh PK. 2011. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334:982–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant SS, Kaufmann BB, Chand NS, Haseley N, Hung DT. 2012. Eradication of bacterial persisters with antibiotic-generated hydroxyl radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:12147–12152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203735109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girgis HS, Harris K, Tavazoie S. 2012. Large mutational target size for rapid emergence of bacterial persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:12740–12745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205124109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conlon BP, Nakayasu ES, Fleck LE, LaFleur MD, Isabella VM, Coleman K, Leonard SN, Smith RD, Adkins JN, Lewis K. 2013. Activated ClpP kills persisters and eradicates a chronic biofilm infection. Nature 503:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JS, Heo P, Yang TJ, Lee KS, Cho DH, Kim BT, Suh JH, Lim HJ, Shin D, Kim SK, Kweon DH. 2011. Selective killing of bacterial persisters by a single chemical compound without affecting normal antibiotic-sensitive cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5380–5383. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan J, Bahar AA, Syed H, Ren D. 2012. Reverting antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 persister cells by (Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-methylfuran-2(5H)-one. PLoS One 7:e45778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebeaux D, Chauhan A, Létoffé S, Fischer F, de Reuse H, Beloin C, Ghigo JM. 2014. pH-mediated potentiation of aminoglycosides kills bacterial persisters and eradicates in vivo biofilms. J Infect Dis 210:1357–1366. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luidalepp H, Jõers A, Kaldalu N, Tenson T. 2011. Age of inoculum strongly influences persister frequency and can mask the effects of mutations implicated in altered persistence. J Bacteriol 193:3598–3605. doi: 10.1128/JB.00085-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roostalu J, Joers A, Luidalepp H, Kaldalu N, Tenson T. 2008. Cell division in Escherichia coli cultures monitored at single cell resolution. BMC Microbiol 8:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen S, Lewis K, Vulic M. 2008. Role of global regulators and nucleotide metabolism in antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2718–2726. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng D, Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Minchin SD. 2004. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5874–5893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson DW, Simecka JW, Romeo T. 2002. Catabolite repression of Escherichia coli biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 184:3406–3410. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.12.3406-3410.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uppal S, Shetty DM, Jawali N. 2014. Cyclic AMP receptor protein regulates cspD, a bacterial toxin gene, in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 196:1569–1577. doi: 10.1128/JB.01476-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]