Abstract

Anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family members target several intracellular Ca2+-transport systems. Bcl-2, via its N-terminal Bcl-2 homology (BH) 4 domain, inhibits both inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs), while Bcl-XL, likely independently of its BH4 domain, sensitizes IP3Rs. It remains elusive whether Bcl-XL can also target and modulate RyRs. Here, Bcl-XL co-immunoprecipitated with RyR3 expressed in HEK293 cells. Mammalian protein-protein interaction trap (MAPPIT) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showed that Bcl-XL bound to the central domain of RyR3 via its BH4 domain, although to a lesser extent compared to the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Consistent with the ability of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL to bind to RyRs, loading the BH4-Bcl-XL peptide into RyR3-overexpressing HEK293 cells or in rat hippocampal neurons suppressed RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. In silico superposition of the 3D-structures of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL indicated that Lys87 of the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL could be important for interacting with RyRs. In contrast to Bcl-XL, the Bcl-XLK87D mutant displayed lower binding affinity for RyR3 and a reduced inhibition of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. These data suggest that Bcl-XL binds to RyR channels via its BH4 domain, but also its BH3 domain, more specific Lys87, contributes to the interaction.

The B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) protein family has long been studied with respect to its prominent role in the regulation of apoptosis1,2. Beyond this, it is becoming increasingly clear that both the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins are crucial regulators of intracellular Ca2+ signaling. In this way, Bcl-2 proteins affect various targets related to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis3,4,5. More specific, this protein family was found to regulate the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels6,7,8, plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPases9, sarco/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCA)10, Bax inhibitor 111,12, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3R)13,14,15 and ryanodine receptors (RyRs)16.

Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins are characterized by the presence of four Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains important for their biological function17. Although their structural organization is very similar, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL may act in very different ways on their targets. As such, the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 is critical for binding to a site in the regulatory domain of the IP3R (a.a. 1389–1408 for mouse IP3R1) thereby inhibiting IP3-induced Ca2+ release14,18. In contrast, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL fails to bind to this IP3R domain and to inhibit IP3Rs19. Moreover, we showed that this difference between the BH4 domains of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL can largely be attributed to a single amino acid change (Lys17 in BH4-Bcl-2 corresponding to Asp11 in BH4-Bcl-XL) in the center of their respective BH4 domains. Indeed, the mutated BH4K17D domain of Bcl-2 and mutated full-length Bcl-2K17D are greatly impaired in targeting and regulating the IP3R.

We recently showed that, similar to its interaction with the IP3R, Bcl-2 via its BH4 domain targets a RyR region (a.a. 2263–2688 for mink RyR3) containing a highly conserved regulatory site (a.a. 2309–2330 for mink RyR3), which shows striking resemblance to the known Bcl-2 binding site on the IP3R16. The interaction of Bcl-2 and the RyR via its BH4 domain results in an inhibition of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. The Bcl-2K17D mutant does not show a dramatic loss of binding to the RyR and is as potent as wild-type Bcl-2 in inhibiting RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. These results may indicate that in contrast to the IP3R, which is differentially targeted by Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, RyRs might have a common interaction site for both proteins and do not distinguish between these two proteins for their regulation.

In this paper, we show that similarly to Bcl-2, Bcl-XL binds to the RyR via a site located in its central, modulatory domain, thereby inhibiting RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. Although the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL was sufficient for inhibiting RyRs, we found that in full-length Bcl-XL not only the BH4 domain but also the BH3 domain contributed to Bcl-XL/RyR-complex formation. In particular, we identified Lys87, located in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL, as an important contributor of Bcl-XL binding to the RyR.

Results

Bcl-XL binds to RyR3

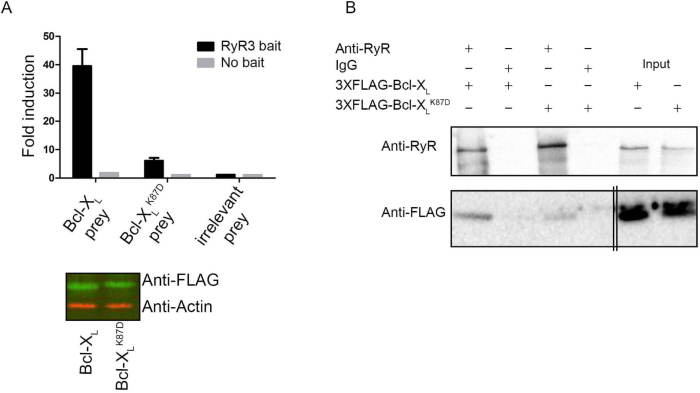

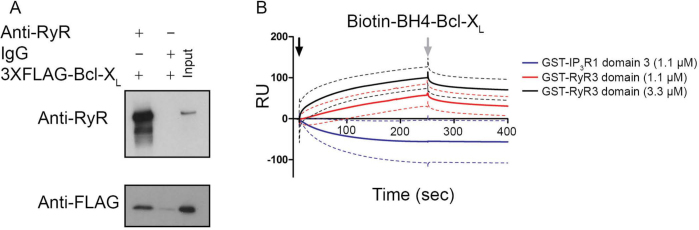

Bcl-2K17D is a Bcl-2 mutant based on a critical difference between the BH4 domains of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL and is impaired in binding to and regulating IP3Rs19. However, this mutant still binds to and regulates RyRs with similar efficiencies as wild-type Bcl-216, suggesting that Bcl-XL may also bind to and regulate RyRs. Hence, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies using lysates from HEK293 cells stably overexpressing RyR3 (HEK RyR3). In these cells, transiently overexpressed 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL co-immunoprecipitated with RyR3 indicating the formation of RyR3/Bcl-XL complexes (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A for uncropped Western-blot images).

Figure 1. Bcl-XL binds to a central regulatory region of RyR3.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed utilizing cell lysates from HEK RyR3 cells transiently overexpressing 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL. RyR3 was immunoprecipitated from these lysates utilizing a pan-RyR antibody. An anti-FLAG-HRP conjugated antibody was used for detecting co-immunoprecipitated 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL. Immunoblot showing the immunoprecipitated RyR3 (top) and co-immunoprecipitated 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL (bottom). Immunoprecipitations using non-specific IgG antibodies were applied as negative controls. All experiments were performed at least three times utilizing each time independently transfected cells and freshly prepared HEK RyR3 lysates. All samples were run using the same experimental conditions on the same gel/blot. The uncropped image is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A. (B) Sensorgrams of the surface plasmon resonance experiments expressed in RU as a function of time. The biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL peptide and the scrambled peptide were immobilized on different channels of a streptavidin-coated sensor chip. The channels on the chip were exposed to the indicated concentrations of purified GST-fusion proteins (GST-IP3R1 domain 3 and GST-RyR3 domain). Binding of the GST-tagged proteins to the scrambled peptides was subtracted from each sensorgram. GST-IP3R1 domain 3 bound stronger to the scrambled peptide than to the biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL resulting in apparent negative values after this correction. The black arrow indicates the start of the association phase (addition of the GST-tagged proteins) and the grey arrow indicates the start of the dissociation phase (running buffer alone). Each sensorgram depicts the average of three experiments (full line) ± S.D. (dashed lines).

In our previous work we reported that the interaction between Bcl-2 and the RyR occurred via the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 and a central regulatory domain of the RyR (a.a. 22632263–2688 for mink 2688 for mink RyR3)16. To examine whether a direct interaction between RyRs and the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL exists and whether this interaction occurs via the same or similar domains, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments were performed (Fig. 1B). A concentration-dependent binding between biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL immobilized to streptavidin coated SPR chips, and the purified GST-RyR3 domain (mink RyR3, a.a. 2263-2688) could be detected. In contrast, but consistent with our previous observations, purified GST-tagged IP3R1 domain 3 (mouse IP3R1, a.a. 9232263–2688 for mink 1581), which is known to bind to the BH4 domain of Bcl-2, failed to bind to biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL19. While biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL was able to bind to the GST-RyR3 domain, it seemed to be less effective than biotin-BH4-Bcl-216. To confirm the proper loading of the biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL peptide to the sensor chip, we monitored the binding of an antibody directed against the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, which caused a prominent increase in resonance unit (RU) values (Supplementary Fig. 2). Collectively, these results indicate that the interaction of Bcl-XL with the RyR3 is direct and that Bcl-XL via its BH4 domain targets the same domain as Bcl-2 on the RyR. However, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL seems to have a lower affinity for the GST-RyR3 domain compared to the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. This could indicate that biotinylation of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL influences its binding capabilities more than is the case for the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Alternatively, other domains besides Bcl-XL's BH4 domain may be involved in the interaction of full-length Bcl-XL with the RyR. Therefore, we wanted to identify if other domains besides the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL are important for interacting with the RyR.

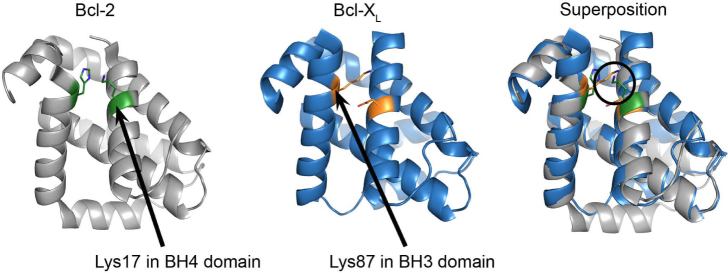

Superposition of the 3D-structures of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL reveals a spatial resemblance of Lys17 in the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 with Lys87 in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL

To identify the contribution and involvement of other Bcl-XL domains for targeting RyR channels, an in silico superposition of the Bcl-2 (PDB-entry 4AQ320) and Bcl-XL (PDB-entry 1R2D21) structures was performed with the aid of PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC.). This superposition allowed the comparison of corresponding residues in the 3D-structures of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (Fig. 2). This analysis revealed that the positively charged ε-amino terminus of the side chain of Lys87 in Bcl-XL, located in the BH3 domain, is in the same spatial constraints as the positively charged ε-amino terminus of the side chain of Lys17 located in the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Furthermore, Lys87 did not seem to be part of the hydrophobic cleft of Bcl-XL, as it was directed towards the space facing the BH4 domain.

Figure 2. Spatial resemblance of Lys17 in the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 and Lys87 in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL.

Image showing the 3D-structures for Bcl-2 (left), Bcl-XL (middle) and their in silico superposition (right). Lys17 in the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 and Lys87 in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL are indicated with arrows. The a.a. in green represent Lys17 and His94 in the BH4 and BH3 domain of Bcl-2 respectively. The a.a. in orange represent Asp14 and Lys87 in the BH4 and BH3 domains of Bcl-XL respectively. The images were obtained by using PyMOL.

The Bcl-XLK87D mutant is impaired in RyR3 binding

The relevance of Lys87 in Bcl-XL for RyR binding was addressed via mammalian protein-protein interaction trap (MAPPIT)22, an in cellulo protein-protein interaction assay. MAPPIT is based on the functional complementation of cytokine receptor signaling. To study the possible existence of RyR/Bcl-XL complexes, the RyR3 domain was cloned downstream of a chimeric cytokine receptor (RyR3 bait), consisting of the extracellular domain of the erythropoietin (Epo) receptor fused to the transmembrane and cytosolic part of the leptin receptor. In the latter, three tyrosines were mutated to phenylalanine to down regulate receptor signaling. Bcl-XL or the Bcl-XLK87D mutant were cloned downstream of a part of the glycoprotein 130 receptor (Bcl-XL or Bcl-XLK87D prey). If the Bcl-XL and Bcl-XLK87D prey constructs interact with the RyR3 bait construct, functional complementation of the chimeric cytokine receptor occurs, leading to ligand-dependent downstream STAT signaling. The latter is monitored via a luciferase reporter assay driven by a STAT-sensitive promoter. We also used the SV40 large antigen T (irrelevant prey) as a prey to monitor the signal representing the non-specific binding to RyR3. As a negative control, binding of the chimeric cytokine receptor without the RyR3 fragment (no bait) to the two Bcl-XL preys was also assessed. These MAPPIT results confirmed the data obtained via SPR and co-immunoprecipitation experiments, showing that Bcl-XL could interact with the RyR3 domain in a cellular context (Fig. 3A, top). Moreover, the Bcl-XLK87D mutant was severely impaired in interacting with the RyR3 domain without affecting its expression (Fig. 3A, bottom panel and Supplementary Fig. 1B for uncropped Western-blot images). No binding was detected when the RyR3 domain was not present in the bait vector (Fig. 3A, top panel), indicating that the interaction was specific.

Figure 3. The Bcl-XLK87D mutant is impaired in RyR3 binding.

(A) Top: Representative example of a MAPPIT experiment. The binding is shown as fold induction value, calculated by dividing the average luciferase value of erythropoietin-stimulated cells by the average of non-stimulated cells. Binding of Bcl-XL (Bcl-XL prey), the Bcl-XLK87D mutant (Bcl-XLK87D prey) or irrelevant prey control (SV40 large T antigen) to the RyR3 domain (RyR3 bait) and as negative control the bait vector without RyR3 (No bait) are shown. Fold induction values at least 4 times higher than the irrelevant prey control are considered as bona fide protein-protein interactions. Values represent the average of three repeats within the same experiment ± S.D. All experiments were independently performed at least three times. Bottom: Odyssey Western blot analyses staining for the FLAG tag of the prey vector containing Bcl-XL or the Bcl-XLK87D mutant fusion proteins (green) or for actin (red) as a loading control. All samples were run using the same experimental conditions on the same gel/blot. The uncropped image is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1B. (B) Co-immunoprecipitations were performed in HEK RyR3 cells transiently overexpressing 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL or 3XFLAG-Bcl-XLK87D similarly as in Fig. 1A. Non-specific IgG antibodies were applied as negative controls. These experiments were performed at least three times utilizing each time independently transfected and freshly prepared HEK RyR3 cell lysates. All samples were run using the same experimental conditions and were derived from the same gel/blot, i.e. 3-8% tris-acetate gels for RyRs and 4-12% bis-tris gels for 3xFLAG-Bcl-XL. The double lines indicate that an additional empty lane separating the immunoprecipitated samples and the input samples was removed for the 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL blot. The uncropped image is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1C.

The impact of mutating Lys87 into Asp was also examined in the context of the full-length RyR3 protein using co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Consistent with the MAPPIT data, 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XLK87D displayed a reduced affinity for full-length RyR3 channels (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 1C for uncropped Western-blot images).

Taken together, these data indicate that Bcl-XL, similarly to Bcl-2, binds via its BH4 domain to the same regulatory domain on RyR3. However, whereas for Bcl-2 the BH4 domain appears to be the main determinant for complex formation with RyR channels, it seems that for Bcl-XL both the BH4 domain and the BH3 domain, likely via Lys87, contribute to the interaction with RyR channels.

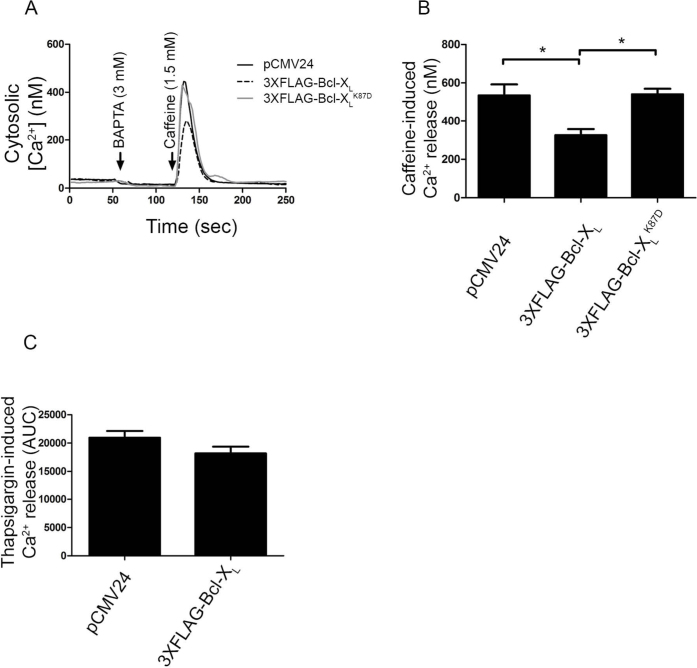

Bcl-XL, but not Bcl-XLK87D, inhibits RyR3-mediated Ca2+ release

Driven by the fact that Bcl-XL can bind to RyR3, we examined whether Bcl-XL could modulate RyR-mediated Ca2+ release (Fig. 4). Single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements in HEK RyR3 cells loaded with Fura-2-AM were performed (Fig. 4A). An empty vector (pCMV24) control, 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL or the 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XLK87D mutant were transiently transfected into the HEK RyR3 cells. An mCherry coding plasmid was co-transfected (at a 1:3 ratio) to identify transfected cells. After chelating extracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA (3 mM), caffeine (1.5 mM) was applied to induce RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. Overexpression of 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL inhibited caffeine-induced Ca2+ release compared to the empty vector control. The Bcl-XLK87D mutant failed to inhibit caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (Fig. 4B), correlating with its poor RyR3-binding properties. To exclude that the observed reduction in caffeine-induced Ca2+ release upon Bcl-XL overexpression would have been due to an indirect effect via lowering of the Ca2+-filling state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), we determined the amount of thapsigargin (1 μM)-releasable Ca2+. This irreversible SERCA inhibitor causes a depletion of the ER Ca2+ stores and provides a good measure for the ER Ca2+-store content. The ER Ca2+-store content was not affected by overexpression of 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL (Fig. 4C). This supports the view that Bcl-XL, similarly to Bcl-2, suppresses RyR-mediated Ca2+ release.

Figure 4. Bcl-XL but not Bcl-XLK87D inhibits RyR-mediated Ca2+ release.

Single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements were performed in HEK RyR3 cells utilizing Fura-2-AM. (A) Average calibrated [Ca2+] trace of 15 to 20 HEK RyR3 cells transfected (mCherry positive) with an empty vector as control (pCMV24), 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL or 3XFLAG-Bcl-XLK87D. Addition of BAPTA and caffeine is indicated by the arrows. (B) Quantitative analysis of the single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements. Values indicate averages of all peak values ± S.E.M. These experiments were independently performed at least four times (>120 cells/condition) (p = 0.008). (C) Quantitative analysis of the ER Ca2+-store content. ER-store content was determined by performing similar experiments as in A except that 1 μM thapsigargin was used as the stimulus. The values indicate the average area under the curve (AUC) ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments (>80 cells/condition).

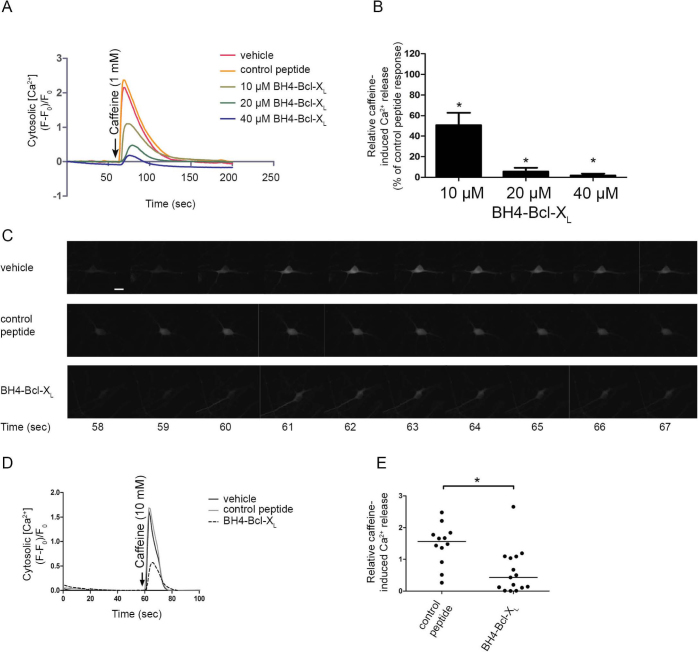

The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL by itself seems sufficient to inhibit RyR-mediated Ca2+ release

In order to assess whether the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL is sufficient for inhibiting RyR-mediated Ca2+ release, Fluo-3-AM loaded HEK RyR3 cells were loaded acutely with the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, a control peptide or the vehicle via electroporation (Fig. 5A). The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, but not a control peptide, suppressed caffeine (1 mM)-induced Ca2+ release. The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL inhibited caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). This indicates that the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL was sufficient for inhibiting RyR-mediated Ca2+ release.

Figure 5. The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL by itself was sufficient to inhibit RyR-mediated Ca2+ release.

(A) Representative trace of the performed Fluo-3-AM single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements in HEK RyR3 cells loaded by electroporation with either the vehicle (DMSO), a control peptide or the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL. The addition of caffeine is indicated by the arrow. Traces were normalized to the baseline fluorescence ((F-F0)/F0). (B) Quantitative analysis of the single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements with indicated concentrations of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL. Values indicate caffeine-induced Ca2+ release after electroporation loading with different concentrations of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL relative to the response after electroporation loading with the same concentration of the control peptide. Values depict average ± S.E.M. of at least four independent experiments (p-values were 0.0037, 0.001 and 0.0039 for 10 μM, 20 μM and 40 μM of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL respectively). (C-E) Single-cell [Ca2+] measurements performed in 14- to 18-day-old hippocampal cultures. GCaMP3, introduced into these neurons via adeno-associated infection, was used as cytosolic Ca2+ indicator. Utilizing whole-cell voltage clamp the membrane potential of the neurons was clamped at −60 mV. 20 μM of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, a control peptide or the vehicle (DMSO) was introduced into each measured neuron via the patch pipette. All experiments were performed in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin. A 10 mM caffeine puff was locally administered via a second patch pipette positioned 15-25 μm from the soma of the neuron. (C) Time lapse of a typical experiment for each of the tested conditions. Caffeine was administered after 60 sec. The scale bar depicts 5 μm. (D) Typical responses to caffeine after loading the neurons with 20 μM of either the control peptide the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL or the vehicle. Traces were normalized to the baseline fluorescence ((F-F0)/F0). The arrow indicates when caffeine was administered. (E) Scatter plot showing peak responses of all performed measurements and the median (horizontal line). All values were normalized to the caffeine response after vehicle control treatment (p = 0.0037, N = 12 and N = 15 for the control peptide and BH4-Bcl-XL respectively).

We also assessed whether the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL could inhibit endogenous RyR channels by using 14- to 18-day-old rat hippocampal cultures known to express different RyR isoforms23. The experimental set-up was identical to the one previously used for characterization of the effect of the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 on native RyRs16. Cytosolic [Ca2+] was monitored in GCaMP3-expressing hippocampal neurons. The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, a control peptide or the vehicle were introduced into the neurons via a patch pipette. After loading the neuron for five minutes with the peptides or vehicle, cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements were started. RyR-mediated Ca2+ release was triggered via a local puff of caffeine (10 mM) delivered via a second patch pipette positioned next to the neuron. A time lapse (Fig. 5C) and a [Ca2+] trace (Fig. 5D) of a typical experiment are shown for each condition. Loading of the neurons with the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL (20 μM) caused a significant reduction of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release compared to the control peptide (Fig. 5 D, E). These results indicate that the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL can regulate endogenously expressed RyR channels.

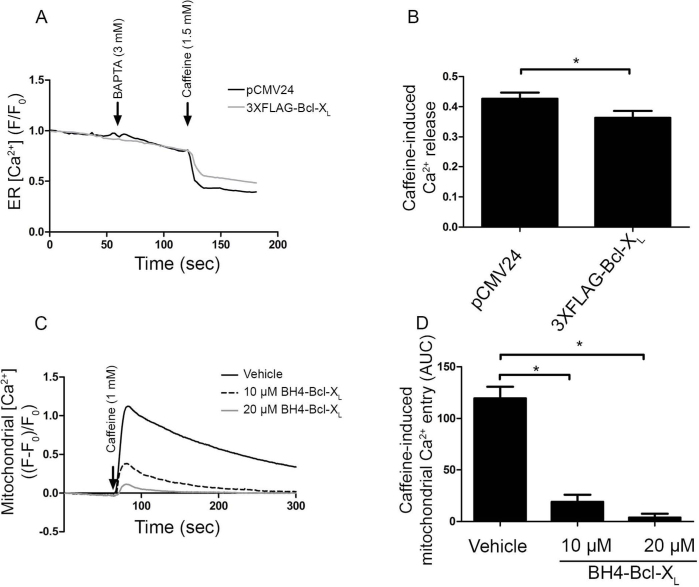

Bcl-XL and its BH4 domain directly inhibit RyRs at the level of the ER

Bcl-XL and its isolated BH4 domain as a synthetic peptide inhibit the caffeine-induced [Ca2+] rise in the cytosol. Bcl-XL has also been implicated in the control of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport at the level of VDAC1. Bcl-XL was shown to inhibit Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria6,24. However, it was also reported that Bcl-XL could stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake25. The latter effect could result in a decrease in caffeine-induced [Ca2+] rise in the cytosol. Therefore, we set out to document whether the decrease in caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in the cytosol by Bcl-XL is due to a decreased Ca2+ release from the ER or to an increased Ca2+ accumulation into the mitochondria. Direct ER-Ca2+ measurements were performed in HEK RyR3 cells utilizing a recently described green fluorescent CEPIA1 protein, that is targeted to the lumen of the ER (G-CEPIA1er)26. HEK RyR3 cells were transiently transfected with the empty vector (pCMV24) as control or with 3XFLAG-tagged Bcl-XL in combination with the G-CEPIA1er-encoding vector (at a 3:1 ratio). G-CEPIA1er-positive cells were selected and measurements were performed as in Fig. 4A. A typical average trace of one experiment and the quantification of all performed experiments are shown in Fig. 6A and B, respectively. These results indicate that overexpression of 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL suppressed the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from the ER, supporting a model in which the inhibitory effect of Bcl-XL on RyR-mediated [Ca2+] rise in the cytosol occurs at least in part due to inhibition of the Ca2+ release from the ER. Finally, we set out to directly measure the effect of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL on caffeine-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ entry. Rhod-FF-loaded HEK RyR3 cells were electroporated with either the vehicle (DMSO) or the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL (10 and 20 μM) and then stimulated with caffeine. Caffeine stimulation resulted in an increase in mitochondrial [Ca2+] (Fig. 6C). Compared to the vehicle control however, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL potently inhibited the mitochondrial Ca2+ entry (Fig. 6 C, D). Furthermore, the effectiveness of BH4-Bcl-XL to inhibit caffeine-induced [Ca2+] rise in the mitochondria seemed higher than for inhibiting the caffeine-induced [Ca2+] rise in the cytosol, because 10 μM BH4-Bcl-XL inhibited caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in the cytosol by about 50% but inhibited caffeine-induced Ca2+ uptake in the mitochondria by about 90%. Taken together these data suggest that BH4-Bcl-XL likely inhibits, rather than stimulates, mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation. This is consistent with our recent findings showing that BH4-Bcl-XL directly interacts with VDAC1 and suppressed VDAC1-mediated Ca2+ transfer into the mitochondria27. These experiments indicate that Bcl-XL can directly inhibit the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release at the level of the ER and potently inhibit mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake under these experimental settings. We therefore conclude that the observed decrease in caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in the cytosol (Fig. 4 and 5) is mainly due to a direct inhibition of RyR3.

Figure 6. Bcl-XL and its BH4 domain directly inhibit RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER.

(A) Typical average normalized (F/F0) traces of single-cell ER [Ca2+] measurement performed in HEK RyR3 cells transfected with G-CEPIA1er plasmid. G-CEPIA1er-positive cells transfected with the empty control vector (pCMV24) or 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL were selected for these measurements. After chelating extracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA, caffeine was added to stimulate RyR-mediated Ca2+ release (arrows). (B) Quantitative analysis of the performed experiments. For each trace the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was determined by subtracting the fluorescence after caffeine addition (during plateau phase) from the fluorescence just before caffeine addition after normalization. Values depict average ± S.E.M. These experiments were independently repeated at least four times (>100 cells/condition) (p = 0.0018). (C) Normalized ((F-F0)/F0) representative traces of mitochondrial [Ca2+] measurements. The vehicle (DMSO) or the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL (10 μM and 20 μM) were introduced into Rhod-FF-loaded HEK RyR3 cells via electroporation loading. Mitochondrial Ca2+ was measured after caffeine (arrow) stimulation. (D) Quantification of the performed experiments. Values show the average caffeine-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ entry as area under the curve (AUC) ± S.E.M. Experiments were independently performed at least three times (p<0.0001).

Discussion

The main conclusion of this paper is that Bcl-XL binds to and regulates RyR3 channels. Similarly to Bcl-2, Bcl-XL targets the central modulatory domain of the RyR protein, thereby suppressing RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. Moreover, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL was sufficient to inhibit both over- and endogenously expressed RyR channels in HEK293 cells or primary rat hippocampal neurons respectively. Consistent with this, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL could bind to the purified RyR3 domain. However, the RyR3-binding efficiency of the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL seemed much lower than that of the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Via an in silico superposition of the Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL crystal structures, a spatial overlap was observed between Lys17 in the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 and Lys87 in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL: the positively charged ε-amino groups of their side chains coincide in space. Consistent with the moderate RyR3-binding properties of the isolated BH4 domain of Bcl-XL, we found that Lys87 from Bcl-XL played a prominent role in binding to and regulating RyR3.

The association of Bcl-XL with RyR channels and its functional implications appear to be very similar as the ones observed for Bcl-2, since i) RyR3/Bcl-XL binding is direct; ii) the binding of Bcl-XL to RyR3 occurs, at least in part, via the BH4 domain; iii) Bcl-XL overexpression inhibits RyR-mediated Ca2+ release; and iv) the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL is also sufficient to suppress RyR activity. These findings correlate with the fact that the Bcl-2K17D mutant and BH4-Bcl-2K17D remain capable of binding to and regulating RyR channels, although this mutation changes the lysine critical for binding to the IP3R into the Asp11 residue in the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL16. This lack of selectivity between Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL may illustrate an important difference between IP3R- and RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. However, the binding of Bcl-XL versus Bcl-2 to RyRs in native tissues expressing RyRs ought to be further explored. In particular, it will be important to carefully analyze the Bcl-2- and Bcl-XL-expression levels in the relevant tissues and to determine whether a preferential binding of Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL to RyR channels exists in cells expressing both Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. Despite these similarities, the molecular determinants underlying RyR/Bcl-XL-complex formation do not seem identical to those of Bcl-2, because the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL by itself displays rather moderate RyR3-binding properties. As a consequence, additional domains seem to be involved in RyR/Bcl-XL-complex formation. Here, we identified Lys87, located in the BH3 domain of Bcl-XL, as a critical determinant contributing to binding to and regulating RyR channels. Despite the importance of Lys87, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL alone was able to suppress RyR activity.

The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL has been implicated in numerous studies to display strong anti-apoptotic and protective effects against a wide variety of insults and triggers, including in the heart28,29,30, endothelial cells31,32, blood cells33,34,35, pancreatic islets36 and neurons37. Many of the cell types and tissues reported to benefit from the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL for their survival endogenously express RyR channels (cardiomyocytes, lymphocytes, pancreatic islets and neurons). Furthermore, in many apoptotic paradigms, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are implicated. ROS can impact the redox state and activity of the RyR channels (reviewed by Ref. 38). Mild increases in ROS moderately increase RyR activity by increasing its sensitivity for Ca2+ 39. However, severe ROS production associated with oxidative stress (e.g. in the context of ischemia/reperfusion injury) can lead to a continuously opening of the RyR channels, provoking an excessive Ca2+ leak from the ER or sarcoplasmic reticulum40. In the context of the heart, ROS has been clearly implicated to cause unzipping of the interdomain interactions critical for RyR2-channel stabilization41,42. During oxidative stress conditions, the BH4 domain of Bcl-XL may thus inhibit excessive RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from the intracellular Ca2+ stores in addition to exerting its protective effects at the mitochondria, thereby providing additional protection against cell death.

RyRs have important physiological functions in a variety of excitable cells and tissues, including skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, neurons and pancreatic cells43,44,45,46. Furthermore, dysregulation of RyRs, either by somatic mutations or by altered expression levels, has been implicated in a variety of pathophysiological conditions, including malignant hyperthermia and central core disease47,48, cardiac diseases49,50,51 and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease52,53,54 and Huntington's disease55. At this point, the existence and physiological relevance of RyR/Bcl-2- and RyR/Bcl-XL-complex formation in these tissues and their potential disturbance in RyR-associated pathophysiologies will require further research.

In conclusion, our data further expand the number of Bcl-2-family members that are able to form protein complexes with RyR channels, thereby underpinning their critical role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ dynamics at the level of intracellular Ca2+-release channels.

Methods

Chemicals, antibodies and peptides

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-actin antibody, anti-FLAG M2 antibody and HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti-RyR antibody 34C (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA, or Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-XL antibody YTH-2H12 (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, WV, USA). The sequences of the peptides used in this study were:

Biotin-BH4-Bcl-XL: Biotin-MSQSNRELVVDFLSYKLSQKGYSW (also used without the biotin tag)

Biotin-scrambled BH4-Bcl-XL: Biotin-WYSKQRSLSGLVMYVLEDKNSQFS

Control peptide: WYEKQRSLHGIMYYVIEDRNTKGYR

These peptides were synthesized by Life Tein (Hillsborough, NJ, USA) with a purity of at least 85%.

Plasmids, constructs and protein purifications

3XFLAG-Bcl-XL was obtained as previously described19. The 3XFLAG-Bcl-XLK87D mutant was obtained by PCR site-directed mutagenesis utilizing the following primers: forward: 5′ATCCCCATGGCAGCAGTAGATCAAGCGCTGAGGGAGGCA3′, and reverse: 5′TGCCTCCCTCAGCGCTTGATCTACTGCTGCCATGGGGAT3′. The pCMV G-CEPIA1er containing plasmid was a gift from Dr. Masamitsu Iino (Addgene plasmid # 58215)26. The GST-IP3R1 domain 3 construct and the GST-RyR3 construct were obtained and purified as described16.

Cell culture, transfections and dissociated hippocampal cultures

All media and supplements added to the medium used in this paper were purchased from Life Technologies (Ghent, Belgium). HEK293 cells stably overexpressing RyR3 were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in α-Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamax and 800 μg/mL G41856. HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 4500 mg/L glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg/mL gentamicin57.

24 hours after seeding, the 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL or the 3XFLAG-Bcl-XLK87D mutant construct were introduced into the HEK RyR3 cells utilizing JETPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus Transfections, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol. 48 hours later the cells were harvested and lysed utilizing a CHAPS-based lysis buffer (pH 7.5, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1% CHAPS and protease inhibitor tablets (Roche, Basel, Switzerland)). For single-cell cytosolic [Ca2+] measurements the same constructs or the empty pCMV24 vector were introduced 48 hours after seeding in the HEK RyR3 cells utilizing X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A pcDNA 3.1(-) mCherry expressing vector was co-transfected at a 1:3 ratio as a selection marker. For direct ER [Ca2+] measurements, the G-CEPIA1er construct was co-transfected (ratio 3:1) and used as selection marker instead of the mCherry expressing vector. Dissociated hippocampal cultures were obtained as described previously58. All animal experiments were performed according to approved guidelines.

SPR analysis

SPR analysis was performed using a Biacore T200 (GE Healthcare, Diegem, Belgium). Immobilization to the streptavidin-coated sensor chip (BR-1005-31; GE Healthcare) and SPR measurements were performed as described previously19. NaOH (50 mM) with 0.0026% SDS was used as a regeneration buffer.

Immunoblot analysis

Samples were prepared and used as previously described19. For visualization of RyRs, NuPAGE 3–8% tris-acetate gels were run. Detection was performed using Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) when using the Chemidoc™ MP system (Bio-Rad, Nazareth Eke, Belgium) or an X-OMAT 1000 processor (Kodak, Zaventem, Belgium). When using the Odyssey imager (Westburg, Leusden, The Netherlands) detection was performed using anti-mouse-IRDye800 (green) or anti-rabbit-IRDye700 (red) as secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific).

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed utilizing a co-immunoprecipitation kit (Thermo Scientific). RyR antibody or mouse IgG control antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) was immobilized according to the manufacturer's protocol. Gelatine was removed from the IgG control antibody utilizing a Pierce Antibody Clean-up Kit (Thermo scientific). Precleared HEK RyR3 lysates containing the 3XFLAG-Bcl-XL constructs (150 μg) were added to the resin to which the antibodies were immobilized and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C. The next day, the resin was washed at least five times utilizing the CHAPS-based lysis buffer. The immune complexes were eluted by boiling (95°C) in 50 μL 2× LDS (Life Technologies) supplemented with 1/200 β-mercaptoethanol for 5 min.

MAPPIT

The RyR3 domain was amplified by PCR using the following primers, forward: 5′TAGTTGTCGACGAAGAGAGAAGTCATGGAGGA3′, and reverse: 5′TAGTTGCGGCCGCCTATTTGGTCCTCTCCACA3′, and cloned in the pSEL+2L bait vector59, using the restriction enzymes SalI and NotI. Bcl-XL was cloned in the pMG1-GW plasmid (prey vector)22 using the Gateway recombination technology as described by the manufacturer (Life Technologies). Utilizing the same primers as described before, the Bcl-XLK87D mutation was also introduced in this construct via site directed mutagenesis. The MAPPIT analyses were done as previously described22 with minor changes. Briefly, HEK293 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. Six wells per condition were transfected with the different combinations of bait, prey and reporter plasmid (rPAP1-luci) using the calcium phosphate method. The next day, half of the wells were stimulated with 5 ng/mL Epo while the other half were left untreated. 24 hours later the cells were lysed and after the addition of substrate the luciferase activity was determined using a luminometer. The fold induction was obtained by dividing the average value of the stimulated cells by the average value of the non-stimulated cells.

Electroporation loading

Electroporation loading of HEK RyR3 cells was performed as previously described16,60.

Single-cell cytosolic Ca2+ imaging

Fura-2-AM and Fluo-3-AM [Ca2+] measurements in HEK RyR3 cells and GCaMP3 single-cell [Ca2+] measurements in dissociated hippocampal neurons were performed as previously described16.

Single-cell ER Ca2+ imaging

The G-CEPIA1er construct was introduced into HEK RyR3 cells as described above. A Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 Inverted Microscope equipped with a 20× air objective and a high-speed digital camera (Axiocam Hsm, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) were used for these measurements. Changes in fluorescence were monitored in the GFP channel (480/520 excitation/emission). To chelate extracellular Ca2+, 3 mM BAPTA (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA) was added. One minute later 1.5 mM caffeine was added to trigger RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. All traces were normalized (F/F0) where F0 is the starting fluorescence of each trace.

Single-cell mitochondrial Ca2+ imaging

HEK RyR3 cells were loaded for 30 min with 5 μM Rhod-FF-AM. Subsequently, cells were subjected to de-esterification over 15 min. During this time the BH4 domain peptides were introduced into the cells using the in situ electroporation technique60. Fluorescence-intensity changes in mitochondria were analyzed with custom-developed FluoFrames software. For each individual trace, the relative change of fluorescence (ΔF/F) was calculated. ΔF/F equals [Ft-F0/F0], with F0 denoting the fluorescence before stimulation with caffeine and Ft the fluorescence at different time points after caffeine stimulation. Subsequently, relative mitochondrial [Ca2+] changes were quantified as the area under the curve of the various Ca2+ traces.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed student's t-tests were performed when two conditions were compared. When comparing three conditions a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was performed. * indicates significantly different results (p<0.05). Exact p-values are indicated in the figure legends, where available.

Author Contributions

The study was conceived and originally designed by T.V., H.D.S., J.B.P. and G.B. with additional input from E.V. and L.Ma. for molecular modeling, J.T. and N.N.K. for MAPPIT and hippocampal neurons, respectively. T.V., E.D., I.L., H.I., E.L. and G.M. performed the experiments. T.V., E.D., L.Mi., L.L., H.D.S., I.L., E.L., H.I., G.M., J.T., L.Ma., N.N.K., J.B.P. and G.B. analyzed, interpreted and/or discussed the data. T.V. and G.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final article.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marco Benevento, Martijn Selten, Wei Ba, Kirsten Welkenhuyzen, Marina Crabbé, Steffi de Rouck, and Anja Florizoone for their excellent technical assistance. We thank Dr. Masamitsu Iino (The University of Tokyo, Japan) for providing the G-CEPIA1er plasmid. This work was supported by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) grants 6.057.12 to G.B., H.D.S., J.B.P. and L.L. and G.0134.09N to L.L., by the Research Council of the KU Leuven via an OT START grant (STRT1/10/044 and OT/14/101) to G.B., by the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Program (Belgian Science Policy; P7/13 to J.T., L.Ma., L.Mi., G.B. and J.B.P., and P7/10 to L.L.), by a “Donders Center for Neuroscience fellowship award of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center” to N.N.K., and by an “FP7-Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant” to N.N.K. (grant number 277091). T.V. was supported for his work in Nijmegen by FWO travel grant V42613N. E.V. is supported by the IWT O&O “Kinase switch” project. H.I. is supported by a PhD fellowship of the FWO, and G.M., I.L. and E.D.C. by postdoctoral fellowships of the FWO.

References

- Brunelle J. K. & Letai A. Control of mitochondrial apoptosis by the Bcl-2 family. J Cell Sci 122, 437–441 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E. & Green D. R. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol 18, 157–164 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chami M. et al. Bcl-2 and Bax exert opposing effects on Ca2+ signaling, which do not depend on their putative pore-forming region. J Biol Chem 279, 54581–54589 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum, Bcl-2 and Ca2+ handling in apoptosis. Cell Calcium 32, 413–420 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco G., Vervliet T., Akl H. & Bultynck G. The selective BH4-domain biology of Bcl-2-family members: IP3Rs and beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci 70, 1171–1183 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel N., Ben-Hail D. & Shoshan-Barmatz V. Mediation of the antiapoptotic activity of Bcl-xL protein upon interaction with VDAC1 protein. J Biol Chem 287, 23152–23161 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel N. & Shoshan-Barmatz V. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1-based peptides interact with Bcl-2 to prevent antiapoptotic activity. J Biol Chem 285, 6053–6062 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotz M., Gillissen B., Hossini A. M., Daniel P. T. & Eberle J. Disruption of the VDAC2-Bak interaction by Bcl-xS mediates efficient induction of apoptosis in melanoma cells. Cell Death Differ 19, 1928–1938 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdek P. E. et al. A novel role for Bcl-2 in regulation of cellular calcium extrusion. Curr Biol 22, 1241–1246 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T. H. et al. Modulation of endoplasmic reticulum calcium pump by Bcl-2. Oncogene 17, 1903–1910 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn T., Yun C. H., Kim H. R. & Chae H. J. Cardiolipin, phosphatidylserine, and BH4 domain of Bcl-2 family regulate Ca2+/H+ antiporter activity of human Bax inhibitor-1. Cell Calcium 47, 387–396 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. & Reed J. C. Bax inhibitor-1, a mammalian apoptosis suppressor identified by functional screening in yeast. Mol Cell 1, 337–346 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes S. A. et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK regulate the type 1 inositol trisphosphate receptor and calcium leak from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 105–110 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y. P. et al. Targeting Bcl-2-IP3 receptor interaction to reverse Bcl-2's inhibition of apoptotic calcium signals. Mol Cell 31, 255–265 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C. et al. The endoplasmic reticulum gateway to apoptosis by Bcl-XL modulation of the InsP3R. Nat Cell Biol 7, 1021–1028 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervliet T. et al. Bcl-2 binds to and inhibits ryanodine receptors. J Cell Sci 127, 2782–2792 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letai A. G. Diagnosing and exploiting cancer's addiction to blocks in apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer 8, 121–132 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y. P., Barr P., Yee V. C. & Distelhorst C. W. Targeting Bcl-2 based on the interaction of its BH4 domain with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793, 971–978 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco G. et al. Selective regulation of IP3-receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis by the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 versus Bcl-Xl. Cell Death Differ 19, 295–309 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez H. L. et al. Identification of a phenylacylsulfonamide series of dual Bcl-2/Bcl-xL antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22, 3946–3950 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manion M. K. et al. Bcl-XL mutations suppress cellular sensitivity to antimycin A. J Biol Chem 279, 2159–2165 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyckerman S. et al. Design and application of a cytokine-receptor-based interaction trap. Nat Cell Biol 3, 1114–1119 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Chapman K. E., Seckl J. R. & Ashley R. H. Partial cloning and differential expression of ryanodine receptor calcium-release channel genes in human tissues including the hippocampus and cerebellum. Neuroscience 85, 205–216 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Konishi A., Kodama T. & Tsujimoto Y. BH4 domain of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members closes voltage-dependent anion channel and inhibits apoptotic mitochondrial changes and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 3100–3105 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. et al. An interaction between Bcl-xL and the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. J Biol Chem 288, 19870–19881 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J. et al. Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat Commun 5, 4153 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco G. et al. The BH4 domain of anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL, but not that of the related Bcl-2, limits the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1)-mediated transfer of pro-apoptotic Ca2+ signals to mitochondria. J Biol Chem Epub ahead of print (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisguerin P. et al. Systemic delivery of BH4 anti-apoptotic peptide using CPPs prevents cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injuries in vivo. J Control Release 156, 146–153 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M. et al. BH4 peptide derivative from Bcl-xL attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury thorough anti-apoptotic mechanism in rat hearts. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 27, 117–121 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugioka R. et al. BH4-domain peptide from Bcl-xL exerts anti-apoptotic activity in vivo. Oncogene 22, 8432–8440 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantara S., Donnini S., Giachetti A., Thorpe P. E. & Ziche M. Exogenous BH4/Bcl-2 peptide reverts coronary endothelial cell apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. J Vasc Res 41, 202–207 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantara S., Thorpe P. E., Ziche M. & Donnini S. TAT-BH4 counteracts Abeta toxicity on capillary endothelium. FEBS Lett 581, 702–706 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R. S. et al. TAT-BH4 and TAT-Bcl-xL peptides protect against sepsis-induced lymphocyte apoptosis in vivo. J Immunol 176, 5471–5477 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell K. W. et al. Anti-apoptotic peptides protect against radiation-induced cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 355, 501–507 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria B. et al. Bcl-xL prevents peritoneal dialysis solution-induced leukocyte apoptosis. Perit Dial Int 28 Suppl 5S48–52 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. et al. Delivery of Bcl-XL or its BH4 domain by protein transduction inhibits apoptosis in human islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323, 473–478 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorana F. et al. The BH4 domain of Bcl-XL rescues astrocyte degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by modulating intracellular calcium signals. Hum Mol Genet 21, 826–840 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli E. et al. Posttranslational modifications of cardiac ryanodine receptors: Ca2+ signaling and EC-coupling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833, 866–875 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo J. J., Hidalgo C. & Bull R. Sulfhydryl oxidation modifies the calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of excitable cells. Biophys J 74, 1263–1277 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Eu J. P., Meissner G. & Stamler J. S. Activation of the cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) by poly-S-nitrosylation. Science 279, 234–237 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki M. et al. Scavenging free radicals by low-dose carvedilol prevents redox-dependent Ca2+ leak via stabilization of ryanodine receptor in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 49, 1722–1732 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T. et al. Defective regulation of interdomain interactions within the ryanodine receptor plays a key role in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Circulation 111, 3400–3410 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. S. Calcium signaling in the islets. Adv Exp Med Biol 654, 235–259 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanner J. T., Georgiou D. K., Joshi A. D. & Hamilton S. L. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2, a003996 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann G. E. & Mattson M. P. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling in excitable cells in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev 63, 700–727 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F. Ryanodine receptors: structure and function. J Biol Chem 287, 31624–31632 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyfenko A. D., Goonasekera S. A. & Dirksen R. T. Dynamic alterations in myoplasmic Ca2+ in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322, 1256–1266 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R., Carpenter D., Shaw M. A., Halsall J. & Hopkins P. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat 27, 977–989 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blayney L. M. & Lai F. A. Ryanodine receptor-mediated arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Pharmacol Ther 123, 151–177 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx S. O. & Marks A. R. Dysfunctional ryanodine receptors in the heart: new insights into complex cardiovascular diseases. J Mol Cell Cardiol 58, 225–231 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori S. G. & Chen S. R. Inherited dysfunction of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis. Circ Res 108, 871–883 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno A. M. et al. Altered ryanodine receptor expression in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 33, 1001 e1001–1006 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete D., Checler F. & Chami M. Ryanodine receptors: physiological function and deregulation in Alzheimer disease. Mol Neurodegener 9, 21 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. The role of ryanodine receptor type 3 in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Channels (Austin) 8, 230–242 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Dantrolene is neuroprotective in Huntington's disease transgenic mouse model. Mol Neurodegener 6, 81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D. et al. RyR1 and RyR3 isoforms provide distinct intracellular Ca2+ signals in HEK 293 cells. J Cell Sci 115, 2497–2504 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyckerman S., Broekaert D., Verhee A., Vandekerckhove J. & Tavernier J. Identification of the Y985 and Y1077 motifs as SOCS3 recruitment sites in the murine leptin receptor. FEBS Lett 486, 33–37 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadif Kasri N., Nakano-Kobayashi A. & Van Aelst L. Rapid synthesis of the X-linked mental retardation protein OPHN1 mediates mGluR-dependent LTD through interaction with the endocytic machinery. Neuron 72, 300–315 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens I. et al. Heteromeric MAPPIT: a novel strategy to study modification-dependent protein-protein interactions in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 31, e75 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decrock E. et al. Electroporation loading and flash photolysis to investigate intra- and intercellular Ca2+ signaling in Calcium Techniques: A Laboratory Manual. (ed. Parys J. B., , Bootman M., , Yule D. I., & Bultynck G., eds. ) 93–112 (Cold Spring Harbor, 2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information