Abstract

Activity-based anorexia (ABA) is a widely used animal model for identifying the biological basis of excessive exercise and starvation, two hallmarks of anorexia nervosa (AN). Anxiety is correlated with exercise in AN. Yet the anxiety level of animals in ABA has not been reported. We asked: Does food restriction as part of ABA induction change the anxiety level of animals? If so, is the degree of anxiety correlated with degree of hyperactivity? We used the open field test before food restriction and the elevated plus maze test (EPM) during food restriction to quantify anxiety among singly housed adolescent female mice and determined whether food restriction alone or combined with exercise (i.e., ABA induction) abates or increases anxiety. We show that food restriction, with or without exercise, reduced anxiety significantly, as measured by the proportion of entries into the open arms of EPM (35.73 %, p= .04). Moreover, ABA-induced individuals varied in their open arm time measure of anxiety and this value was highly and negatively correlated to the individual’s food restriction-evoked wheel activity during the 24 hours following the anxiety test (R = − .75, p= .004, N = 12). This correlation was absent among the exercise-only controls. Additionally, mice with higher increase in anxiety ran more following food restriction. Our data suggest that food restriction-evoked wheel running hyperactivity can be used as a reliable and continuous measure of anxiety in ABA. The parallel relationship between anxiety level and activity in AN and ABA-induced female mice strengthens the animal model.

Keywords: Activity-based anorexia, anxiety, anorexia nervosa, food restriction, exercise

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric disorder with a mortality rate of 10 – 15 % (Birmingham, Su, Hlynsky, Goldner, & Gao, 2005; Bulik, Slof-Op't Landt, van Furth, & Sullivan, 2007; Sullivan, 1995). There is no accepted pharmacological treatment for this disorder and the underlying pathology in the illness is not well understood. This necessitates the development and use of an animal model. The latter may yield insight into the emergence of disease, a pre-clinical phase that is difficult to study in the human population. An animal model also makes it possible to conduct post mortem analysis of the brain to study neurochemical changes underlying the biobehaviors of disease.

Currently, the most widely accepted animal model for AN is activity-based anorexia (ABA). In this model, access to a running wheel is combined with a restricted feeding schedule. Several species of rodents, including rats and mice, respond to this environment by increasing their voluntary wheel activity several-fold (Chowdhury, Wable, Sabaliauskas, & Aoki, 2013; W. F. Epling, Pierce, & Stefan, 1983; Gutierrez, 2013; Hall & Hanford, 1954; Klenotich & Dulawa, 2012; Routtenberg & Kuznesof, 1967). This combination of food restriction with greatly increased wheel activity leads to exaggerated weight loss and eventual death, unless wheel access and food restriction are removed from the environment. Importantly, the ABA model captures two hallmarks of AN – excessive voluntary exercise as well as starvation. Since many of the ABA animals run on the wheel during the limited hours of food access, the food restriction imposed by the experimenter turns into self-starvation.

AN is commonly co-morbid with an anxiety disorder (Kaye, Bulik, Thornton, Barbarich, & Masters, 2004). A high tendency to control anxiety is found in AN, and individuals suffering from AN may get a sense of control over emotional distress through dieting and exercise (Fiore, Ruggiero, & Sassaroli, 2014). Anxiety control may also mediate the drive for thinness, leading to over-exercise (Fiore et al., 2014). Indeed, no less than 40% and as many as 80% of the individuals with AN exhibit excessive exercise (Davis, Katzman, & Kirsh, 1999; Hebebrand et al., 2003), and this often precedes the formal diagnosis. The levels of anxiety and severity of exercise are correlated in patients diagnosed with AN (Holtkamp, Hebebrand, & Herpertz-Dahlmann, 2004; Penas-Lledo, Vaz Leal, & Waller, 2002; Shroff et al., 2006). It is possible that anxiety, either preceding or secondary to food restriction, leads to hyperactivity.

An animal model of the disease might be used to investigate the important role that anxiety may play in AN. Yet the anxiety level and its relationship with wheel running in ABA has never been reported. Outside of the ABA model, the relationship between wheel running and anxiety is fairly complicated, as it is affected by age, sex, and social conditions of the rodents (Sciolino & Holmes, 2012). Wheel running was found to be anxiolytic in singly housed female wild-type mice, which is the group most comparable to our experimental animals (Pietropaolo et al., 2008) although to our knowledge we are the first to examine the effect of a short duration of wheel access. In this study, our goal was to examine the relationship between the severity of response to ABA and anxiety. We sought to achieve this by looking at the measures of each - wheel activity in ABA and behavioral tests for anxiety. Our first aim was to determine whether food restriction alone or wheel access alone evoke a measurable change in anxiety and whether food restriction combined with access to a running wheel abates or increases anxiety measures. This question was answered by using behavior tests to quantify anxiety of ABA animals just before and during food restriction and comparing these values to the anxiety measures of age-matched animals that were only food-restricted, only given access to a running wheel, or exposed to neither treatments. Specifically, we employed the widely accepted test, namely the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) to measure anxiety levels during food restriction of the ABA paradigm and compared this to the Open Field (OF) test conducted before food restriction to determine whether individual differences in anxiety existed prior to food restriction and were altered by it.

We have previously shown that running activity of individual animals correlates negatively with their level of α4-containing GABA receptors in the hippocampus (Aoki et al., 2014) and to the extent of GABAergic innervation of the hippocampal pyramidal cells (Chowdhury et al., 2013). Thus, individual differences in the ABA model are a meaningful way of exploring the underlying pathology. In this study, our second aim was to determine whether individual differences in the severity of response to ABA could be explained by individual differences in anxiety measured before food restriction and/or in the state anxiety measured during food restriction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL6 mice were purchased as breeders from Charles River Laboratories, MA, USA at age P35. Following a week of acclimation, they were paired. The breeders were never assigned to any experimental condition. Only their litters were used for the experiments. Litters from these breeders were weaned at P25 and animals were group-housed with same-sex littermates in a 12 hour light/ 12 hour dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h). Female mice were used in this study due to the high prevalence of AN in females (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003). On P37, female mice were assigned to one of four experimental groups (Supplemental Table 1). Several litters were divided into two of the four experimental groups, and each group had animals from multiple litters to ensure that the group differences were not confounded by differences in litters. All procedures relating to the use of animals were in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of New York University (A3317-01).

ABA induction and behavioral controls

Control (CON) animals were housed in standard home cages with ad libitum access to food (and no running wheel access) for the duration of the study. At noon on P37 (start of Day 1 of experiment), animals in the ABA and EX (exercise control) group were placed in standard home cages with running wheels attached (low-profile mouse wheel, Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT) and ad libitum access to food in order to record baseline wheel activity. Starting on P40 at noon (start of Day 4 of experiment) until noon on P43 (end of Day 6), animals in the ABA and FR (food restriction control) group were given unlimited access to food for the first two hours of the dark cycle; food was not available for the remaining 22 hours per day (Fig. 1A). EX animals continued to have unrestricted access to food. Body weight, food intake, and wheel running activity (where applicable) were measured daily within 20 min prior to the start of the dark cycle.

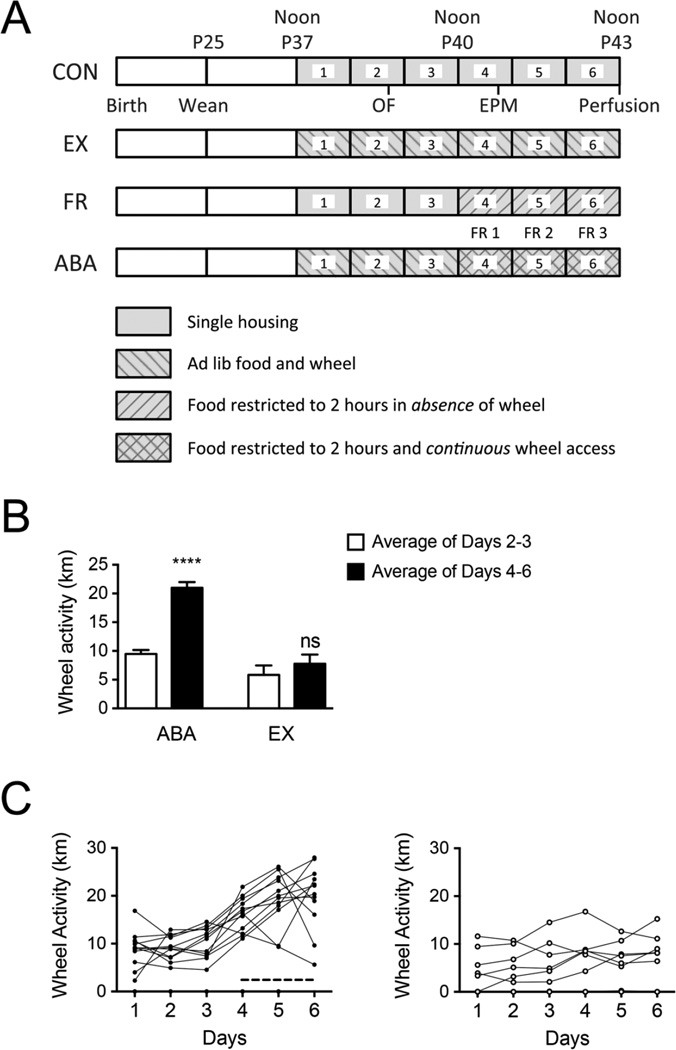

Figure 1.

The schedule of activity-based anorexia (ABA) and experimental controls and their wheel activity.

Panel A. Control (CON) animals (N = 9) were housed singly in standard home cages with ad libitum access to food (and no running wheel access) for the duration of the study. At noon on P37 (beginning of Day 1 of experiment), animals in the ABA (N = 12) and EX (N = 7) (exercise control) group were placed in standard home cages with running wheels attached and ad libitum access to food in order to record baseline running activity. Starting at noon on P40 (beginning of Day 4) until noon on P43 (end of Day 6), animals in the ABA and FR (food restriction control, N = 8) group were given unlimited access to food for the first two hours of the dark cycle; food was not available for the remaining 22 hours per day. For the ABA and FR animals, Days 4, 5 and 6 of the experiment are referred to as FR1 (food restriction day 1), FR2 (food restriction day 2), and FR3 (food restriction day 3) respectively. EX animals continued to have unrestricted access to food. Body weight, food intake, and wheel running activity (where applicable) were measured daily within 20 min prior to the start of the dark cycle.

Panel B. Averaged wheel activity of ABA animals and age-matched controls. Food restriction greatly increased wheel running activity. The white bars represent average baseline wheel activity of twelve ABA and seven EX animals (Days 2–3). The first day of wheel activity is not included in the analysis because the mice are getting acclimated to the novelty of the wheel and being singly housed. The black bars represent average wheel activity measured during the food restriction phase for ABA animals and corresponding days for EX animals (fed ad lib during the phase) (Days 4–6). **** indicates p < .001, ns indicates no difference, comparing the black bars with respective white bars of the same group.

Panel C. Wheel activity of ABA and EX. Daily activity of twelve ABA (on the left) and seven EX (on the right) animals was measured as the distance run on the wheel. The dotted line parallel to the x-axis indicates the days of food restriction for the ABA group. During food restriction, the ABA animals increased their running much more than the EX animals which were fed ad lib.

Loss of wheel data: Due to technical failure, continuous wheel data were not collected for 4 animals of the ABA group from 8 am – 9 pm on P42. This interval comprised of the final four hours of FR2 (8 am – noon) and the initial 9 hours of FR3 (noon - 9 pm). Wherever we report data from FR2 and FR3, wheel counts for these periods of loss were omitted for all animals.

Behavioral Testing

Open Field (OF)

On P39 before noon (end of Day 2), corresponding to the end of two days of single housing with ad lib food access, mice were tested for 10 minutes in the OF test in a room separate from the one in which they were housed. The field dimensions were 70 x 70 x 30 cm. The tests were conducted between 1000 and 1300 h, following habituation (30 minutes in the homecage) to the light and noise level of the room where the open field apparatus was located. The mice were tracked by infrared beam breakages recorded by MDBActivity Monitor. Both the apparatus and the software were manufactured by Med Associates, Vermont, USA. Each animal was placed in the center of the open field at the beginning of the test. The open field was cleaned with 30% ethanol between animals. The raw data were imported into Matlab (Version 2010b, MathWorks, MA, USA) and analyzed for the position of the mouse once every second. The field was divided into 16 equal squares and the central 4 squares were considered to be the center of the field.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

EPM tests were conducted on P41 (end of Day 4/FR1), 48 hours after recovery from the open field, and 21 hours after onset of food restriction as applicable to ABA and FR. The maze, custom made with white polypropylene, was placed on a platform in a room illuminated with dim ambient lighting. Each of the four arms was 30 cm long and 5 cm wide on the inside. The walls of the two closed arms were 15 cm high and 1 cm thick. The floor of the maze was elevated 39 cm above the platform. Each animal was placed in the center of the elevated plus maze facing an open arm. A video camera (Panasonic model no. WV-BP334, Panasonic Corporation of North America, NJ, USA) was positioned about 433 cm above the mouse to record behavior during the 10 min test. At the end of the test, the animal was weighed and returned to its cage. The maze was cleaned with 30% ethanol between animals. The videos were recorded using EthoVision sofware version 4.1.106, manufactured by Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands. Subsequently, the videos were scored by an observer, blind to the experimental condition of the animal, to note the location of the animal at every second. The locations possible were as follows: open arm, closed arm, center. The mouse was classified to be present in a particular arm when all four paws had crossed into that arm.

Methodological considerations

The EPM was scheduled at the end of 21 hours of food restriction to study the emergence of anxiety in the mice. The timing allowed us to examine whether the change in anxiety preceded the maximal rise in wheel activity, which for some mice exposed to ABA is on the second day of food restriction (Chowdhury et al., 2013). Some but not all animals decrease their activity on the third day of food restriction (unpublished data and this study). Why this may occur only in some animals is unknown. The timing of the elevated plus maze test ensured that none of the mice would be inactive, a state that would render the EPM measure uninterpretable.

There is considerable evidence that repeating the open field or elevated plus maze tests raises issues with interpretation due to habituation to the environment of the test (Almeida, Garcia, & De Oliveira, 1993; Bond & Giusto, 1977; Bronstein, 1972, 1973; Bronstein, Wolkoff, & Levine, 1975; File, 1993; File, Mabbutt, & Hitchcott, 1990; Kierniesky, Sick, & Kruppenbacher, 1977; Lee & Rodgers, 1990; R. J. Rodgers, Lee, & Shepherd, 1992; R. Rodgers & Shepherd, 1993; Russell & Williams, 1973; Treit, Menard, & Royan, 1993; Valle, 1971). Therefore, we have chosen two different tests in the baseline and food restriction periods in the experiment.

Statistical analysis

Normality of the distribution of measures was tested using the D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test and Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate differences between the four groups, using wheel access and food access as the two factors. When two-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the effect of experimental days on wheel activity, the day of experiment was used a repeated measure. Pearson’s correlation was computed between normally distributed measures of anxiety and ABA. Spearman correlation was used if the measures were not distributed normally. Statistical software used was GraphPad Prism Version 6.

Exclusion criteria: ABA and EX groups each had one animal that did not use the running wheel (< 20 wheel revolutions on three consecutive days during the experiment). These two animals were excluded from analysis.

RESULTS

Wheel running reveals group differences and individual variability

Previously, we had shown that food restriction evokes a robust (66 %) increase of voluntary wheel running of adolescent female mice (Chowdhury et al., 2013). However, it remained untested whether animals without food restriction would also increase wheel running, simply from exposure to the wheel over a period of eight days. In order to determine whether the increased wheel running was evoked specifically by food restriction, we analyzed the wheel running pattern of ABA (food restricted) and EX (fed ad libitum) mice, matched for age and genetic background.

Baseline running was computed as average running wheel activity on days 2 and 3 of the experiment. The first day of wheel activity was not included in the analysis because the mice were getting acclimated to the novelty of the wheel and being singly housed. Wheel activity during the food restriction period for the ABA animals was computed as the average daily running wheel activity on days 4, 5 and 6 of the experiment. As was shown previously, ABA animals increased their running after the onset of food restriction (mean increase = 7.9 ± 1.3 km per 24 hr, N=12). This increase was significantly higher (t (17) = 3.38, p = .003) than the increase shown by EX animals (1.6 ± 0.8, N = 7) over the same number of days but in the absence of food restriction (mean difference between the groups = 6.3 ± 1.8)(Fig. 1B). ABA animals had a higher mean baseline running than EX animals, but this difference across the treatment groups was far less than the difference that emerged after food restriction for the ABA group, relative to the age-matched EX group (Fig. 1B). We will refer to the increased running following food restriction as hyperactivity. The hyperactivity of ABA animals changed over the experimental days (Fig. 1C) suggesting an evolving impact of the food restriction. This prompted us to look at the evolution of the relationship between running activity of individual animals on different days with anxiety measures.

EPM open arm entries are increased by food restriction but not by wheel access

The number of entries into the open arms is a measure influenced by anxiety (Walf & Frye, 2007). Entries into the open arm is also influenced by total activity levels, as is indicated by the positive correlation of total entries with entries into the open arms (R = .7 and .82; p = .010 and .003 for ABA and CON groups respectively). To normalize for individual differences in overall activity level, the number of entries into the open arms was divided by the total entries (Lister, 1987). This ratio was 35.73 % higher for the FR and ABA groups (Mfood restricted = 0.118 ± 0.01) as compared to the EX and CON groups (Mad lib = 0.087 ± 0.008, main effect of food in a two-way ANOVA, F (1,32) = 4.578, p = .040; no effect of the wheel, F (1,32) = 0.24, p = .62, no interaction F (1,32) = 0.15, p = .7) (Fig. 2A). This effect of food restriction on open arm entries is consistent with the demonstrated anxiolytic effect of mild-to-moderate calorie restriction (Riddle et al., 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2009).

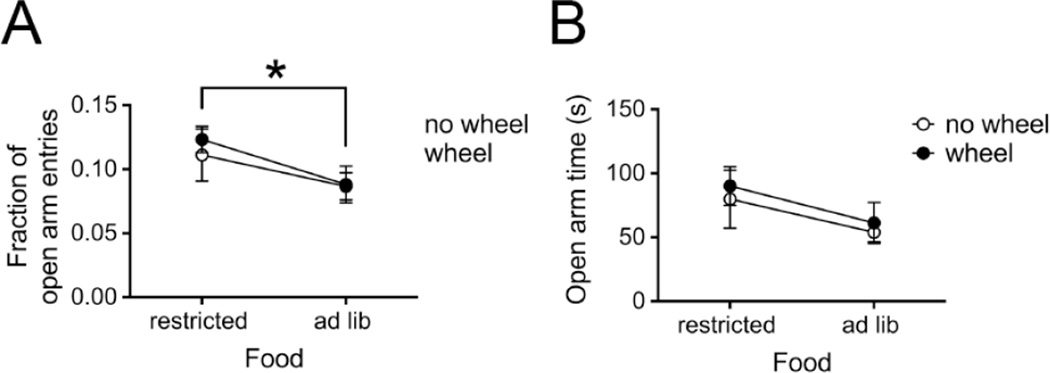

Figure 2.

Twenty-one hours of food restriction is anxiolytic as measured by the elevated plus maze (EPM).

Panel A. Entries into the open arms of the EPM, expressed as a fraction of total entries, are higher for the ABA and FR mice than for the EX and CON mice. A 2-way ANOVA shows a main effect of food, the factor depicted on the x-axis. The other factor, wheel, is depicted as two separate lines. * indicates p = .040 for the main factor of food.

Panel B. Time spent in the open arms of the EPM by the food restricted groups (i.e., with wheel = ABA; without wheel = FR) tended to be higher than for the ad lib fed groups (i.e., with wheel = EX; without wheel= CON). This is supported by the trend to an effect of the main factor, food, which in the 2-way ANOVA is depicted along the x-axis. The main factor wheel is depicted using separate lines.

The time spent in the open arms is widely used to measure anxiety in mice, with greater time spent in the open arm being considered as less anxious behavior (Carola, D'Olimpio, Brunamonti, Mangia, & Renzi, 2002; Walf & Frye, 2007). We evaluated whether access to the wheel (i.e., ABA and EX groups of mice) or food restriction (i.e., the ABA and FR groups of mice) for a day (as EPM was conducted at the end of FR1) increased or decreased anxiety of the animals as a group. Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences among the four groups in the time spent in the open arms (Fig. 2B). There was no main effect of wheel access (F (1,32) = .29, p = .59) or interaction (F (1,32) = .01, p = .93). There was, however, a trend to an effect of food access, with the food restricted groups (i.e., with wheel=ABA; without wheel=FR, Mfood restricted = 86.05 ± 12.49 s) spending more time in the open arms than the ad libitum fed groups (i.e., with wheel = EX; without wheel= CON, Mad lib = 57.13 ± 7.96 s) (F (1,32) = 2.82, p = .10).

EPM open arm time and proportion of entries into open arms are correlated with wheel running following food restriction in ABA animals

Two-way ANOVA did not reveal an effect of four days of wheel activity upon anxiety measured by time spent in the open arms or entries made into the open arms as a proportion of total entries. However, since individual animals exhibited great variability in wheel activity, we surmised that individuals’ differences in wheel activity might be related to individuals’ state anxiety. Indeed, within the ABA group, there was a highly significant negative correlation between the time spent on the open arm and the average wheel activity during the three post-food restriction days (R = − .79, p = .002 N = 12) (data not shown). Further analysis of the individual days of food restriction revealed that there was a negative correlation between the time spent on the open arm and the daily running activity on FR2 (Day 5, i.e. day following the EPM) (Table 1, Fig. 3A, left) but not FR1.

Table 1.

Coefficients and p-values of correlational analyses between measures of anxiety-like behavior and running wheel activity.

| Group | Running wheel activity (km) |

EPM | OF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| open arm time (s) |

Fraction of entries into open arms |

Entries into open arms |

Total entries |

Time in center of open field (s) |

|||

| ABA | Day 2 | R | −.30 | −.07 | .02 | .13 | .03 .89 |

| p | .35 | .82 | .94 | .68 | |||

| EX | Day 2 | R | .54 | .48 | −.14 | −.75 | |

| p | .21 | .28 | .76 | .051 | |||

| ABA | Day 3 | R | −.31 | −.02 | .11 | .17 | −.17 .49 |

| p | .33 | .95 | .74 | .60 | |||

| EX | Day 3 | R | .10 | .12 | −.30 | −.53 | |

| p | .84 | .79 | .52 | .22 | |||

| ABA | Day 4 (FR1) | R | −.38 | −.58 | −.70 | −.50 | −.41 |

| p | .22 | .044 | .012 | .09 | .18 | ||

| EX | Day 4 | R | .15 | .07 | .44 | −.70 | .10 |

| p | .75 | .87 | .30 | .08 | .80 | ||

| ABA | Day 5 (FR2) | R | −.75 | −.60 | −.34 | .05 | −.05 |

| p | .004 | .035 | .28 | .85 | .86 | ||

| EX | Day 5 | R | .25 | .34 | .17 | −.63 | .30 |

| p | .58 | .45 | .67 | .13 | .49 | ||

Pearson’s coefficients are reported for all analyses except for correlation involving the time in center of OF of ABA group with running wheel activity (RWA) on Days 4 and 5. The analysis involving time in center of OF and RWA on days 2 and 3 combined data for ABA and EX groups because they are identical in terms of experimental schedule in that period. Significant correlations (p < .05) are bolded and in red (gray).

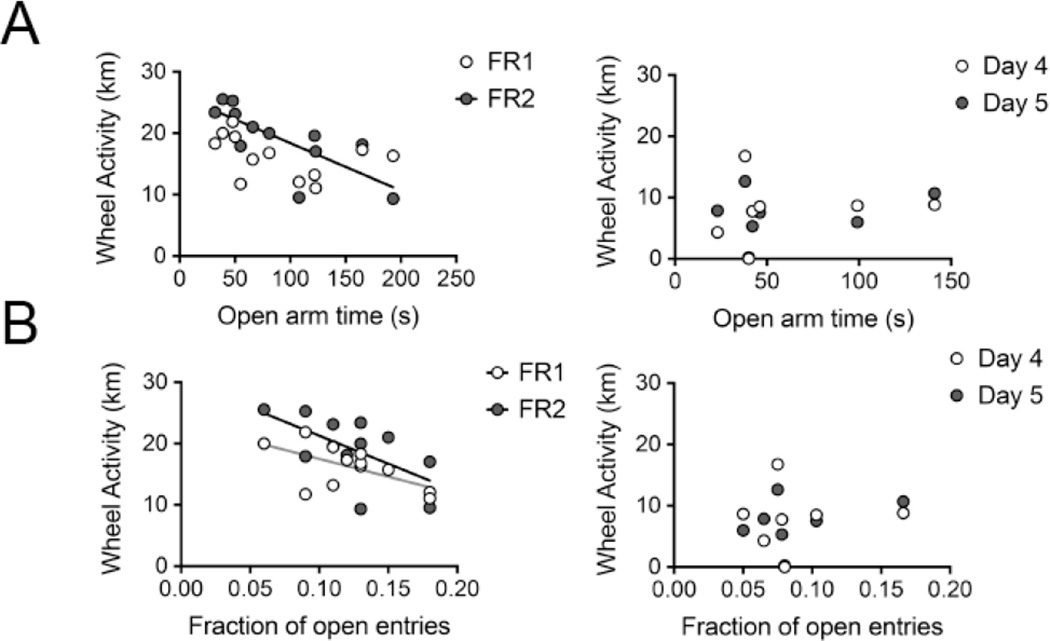

Figure 3.

The measures of anxiety in the EPM, open arm time and fraction of entries into the open arms, are correlated negatively with the wheel activity following food restriction in the ABA group, but not with the wheel activity in the EX group on the corresponding experimental days. Regression lines indicate a significant correlation with p < .05. The graphs on the left in each panel belong to the ABA group, whereas those on the right in each panel belong to the EX group.

Panel A. The time spent in the open arms of the EPM correlates negatively with the wheel activity of ABA animals on FR2, but not of the EX animals on the corresponding day.

Panel B. The fraction of total entries made into the open arms is correlated negatively with the wheel activity of ABA animals on FR1 and FR2, but not of the EX animals on corresponding days.

In the EX group, there was no correlation between the time spent on the open arm and the average wheel activity during the Days 4, 5 and 6, corresponding to ABA group’s FR1 through FR3 (R = .31, p = .49) (data not shown). Analysis of wheel running during Days 4 and 5, separately, which correspond to ABA group’s FR1 and 2, also did not reveal correlation to the open arm time in the EPM (Table 1, Fig. 3A, right). The contrasting results between the ABA and EX groups suggest that wheel running per se is not a manifestation of anxiety, but becomes so in the presence of food restriction.

The fraction of entries made into the open arm by ABA animals correlated negatively with the wheel activity on the first two days of food restriction FR1 and FR2 (Table 1, Fig. 3B, left). These findings are consistent with the idea that wheel activity is an expression of the animal’s anxiety level that emerges by FR1.

This was not so in the EX group. The lack of correlation between the fraction of entries into the open arm (Table 1, Fig. 3B, right) and the daily running activity on Days 4 and 5 supports the idea expressed above that wheel running in the absence of food restriction is not a manifestation of anxiety.

The severity of response to ABA as measured by wheel activity is correlated with the change in anxiety level produced by food restriction

The anxiolytic effect of food restriction, as indicated by EPM and two-way ANOVA (Fig. 2), would predict that if wheel activity in ABA is positively correlated with anxiety level, then a reduction in anxiety level, such as by food restriction, would lead to a decrease in wheel activity by the ABA group. This contradicts our observation. Instead, we observed that wheel running by the ABA group increased after a supposedly anxiolytic treatment of food restriction (Fig. 1B) and the extent of running correlated tightly and negatively with anxiety level as measured in the EPM (Fig. 3). This contradiction was resolved by observing that the ABA as well as the FR mice underwent differential changes in anxiety level evoked by food restriction, while the EX and CON mice did not undergo any change in anxiety level (Fig. 4A). We measured the change in anxiety of individual animals by using the time spent in the center of the open field (OF) (Carola et al., 2002) to measure their level of anxiety prior to food restriction, relative to EPM anxiety measurements after food restriction (Fig. 4A). Carola et al have shown a correlation between the measurements of anxiety in OF and EPM. We also observed that the time spent in the center of the OF was correlated positively to the EPM open arm time for the EX and CON animals (R = .94, .73, p = .001, .014). These correlations indicate that both OF and EPM were reliable, stable tests for measuring anxiety of the EX and CON groups, whereas the anxiety measures changed much for the FR and ABA groups, as a result of food restriction. Correspondingly, the ABA and FR groups showed a lack of correlation between the EPM open arm time and time in center of the OF (R = .04, .585, p = .899, .128 respectively).

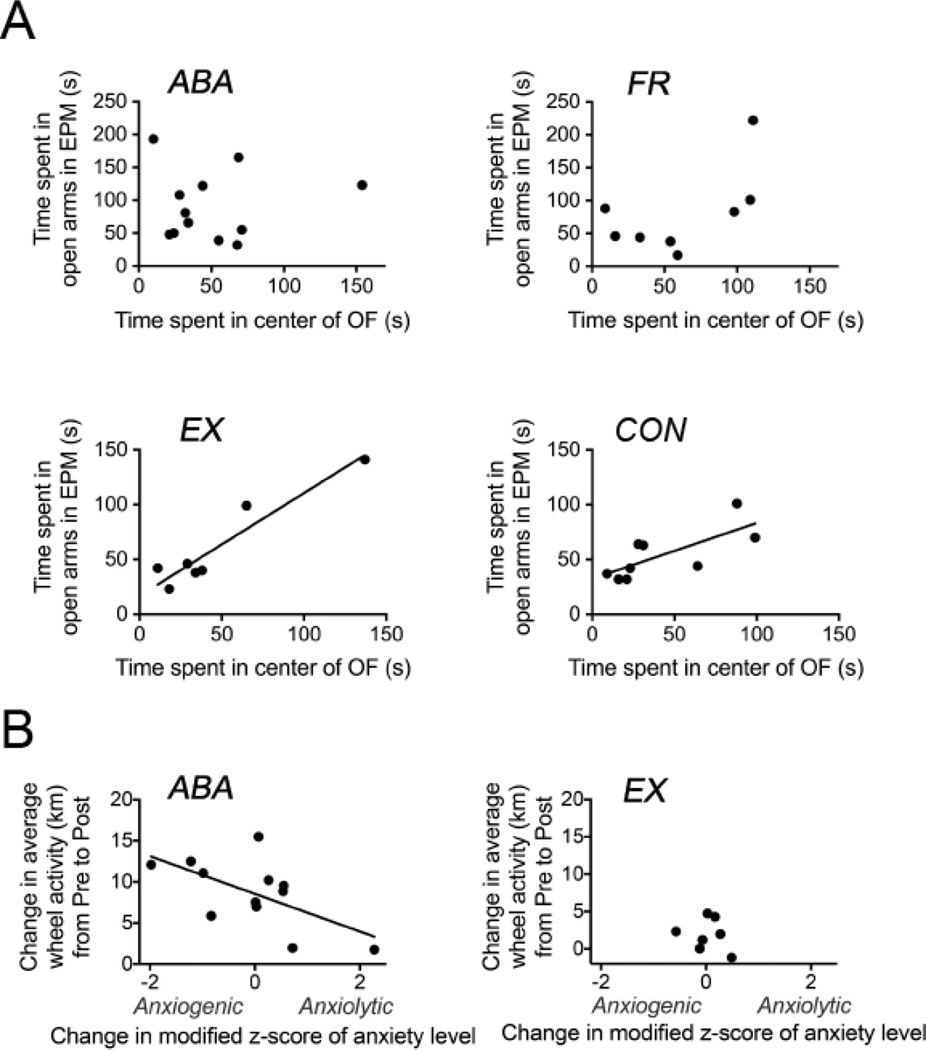

Figure 4.

The overall effect of food restriction on anxiety levels is anxiolytic, but on individual animals, it is qualitatively and quantitatively different. ABA and FR in Panel A demonstrate the different changes in anxiety level of individual animals. The change induced in the anxiety level in ABA mice is correlated with the change induced in the wheel activity from baseline levels by food restriction (Panel B).

Panel A. The x-axis shows the time spent in the center of the open field (OF) prior to food restriction and the y-axis shows the time spent in the open arms of the EPM after 21 hours of food restriction. The ABA and FR mice do not show any correlation between these two measures, whereas EX and CON mice show a positive correlation.

Panel B. The x-axis shows the change in the modified z-scores (based on the median) of the EPM open arm time relative to the OF center time for the ABA (on the left) and EX animals (on the right). Positive values indicate an increase in the z-score, hence a relative increase in non-anxious behavior in the EPM than in the OF, and hence an anxiolytic effect of food restriction. Negative values correspondingly indicate an anxiogenic effect. The y-axis is the increase in the average daily wheel activity during the food restriction phase (post food restriction) relative to baseline (pre food restriction). The change in the modified z-scores of anxiety level is negatively correlated with the change in activity from the pre- to the post-food restriction phase in the ABA animals, but not in the EX animals.

Within the ABA group, the medians of the two measures, OF center time and EPM open arm time were quite different, 39 s and 73.5 s respectively. In order to make a meaningful comparison, we computed a modified z-score for the anxiety level measured in the OF as follows: modified z-score = (time spent in center of OF minus its median value) / interquartile range. Similarly, we calculated the modified z-score for the anxiety level measured by the EPM test as follows: modified z-score = (time spent in the open arms minus its median value)/ interquartile range. We chose to use the modified z-score instead of the standard z-score, because the OF center time measure of the ABA group was not normally distributed (D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test, K2 = 13.88, p = .001, Shapiro-Wilk normality test W = 0.81, p = .013).

Using these modified z-scores, the ABA mice could be categorized as belonging to one of the following three sub-types:

Those for whom food restriction was anxiolytic, identified as exhibiting higher modified z-score for the EPM than the OF measure.

Those for whom food restriction was anxiogenic, identified as exhibiting lower modified z-score for the EPM than the OF measure.

Those that underwent no change in anxiety level, identified as exhibiting very similar or the same modified z-score for OF and EPM.

We considered whether the severity of response to ABA, as measured by the increase in running, following the onset of food restriction relative to the baseline running, was related to the change in anxiety level, computed as a difference between anxiety measurement by EPM after and by OF before food restriction. Indeed, changes in wheel running (and thus of severity of response to ABA) correlated negatively and strongly with changes in anxiety (R = − .612, p = .034) (Fig. 4B). The change in modified z-scores for the EX group were not correlated to the change in wheel activity (R = 0, p = .97, data not shown).

Wheel activity is not correlated to the total entries in the EPM

The total entries in the EPM are a measure of general activity (Lister, 1987; Walf & Frye, 2007). To examine whether the difference in wheel activity between the ABA and EX groups was a generalized change in activity or specific to wheel running, we compared the total entries between groups. There was a significant effect of wheel in a two-way ANOVA on total entries (F (1,32) = 20, p < .001, Mwheel = 58.79 ± 3.78 is less than Mnonwheel = 82.24 ± 3.97) but no effect of food access (F (1,32) = 2.38, p = .13) or interaction (F (1,32) = 3.8, p = .06) (data not shown). However, the mean values of total entries for the ABA (mean = 58 ± 4.81) and the EX (mean = 60.14 ± 6.56) groups were not different from one another (Tukey's post hoc test, p = .99). From this post hoc test, we conclude that the difference in activity induced by food restriction is only in the domain of wheel running (Fig. 1B), and not generalized to all types of activity, when the wheel access is available. Furthermore, the wheel activity is uncorrelated with the total entries in the EPM (Table 1), indicating that wheel activity is a specific type of activity, and is unlike general walking or exploratory activity.

The FR group (mean = 92 ± 4.3) exhibited greater number of total entries than the ABA group (q = 6.811, p < .001). This could be because food restriction rendered the FR animals hyperactive (Gelegen et al., 2007; Klenotich & Dulawa, 2012) but without a wheel as an outlet for this hyperactivity.

Time spent in the center of the OF before food restriction does not correlate to the wheel activity preceding or following food restriction

To ensure that there were no pre-existing differences in anxiety among the experimental groups, we tested ABA, FR, EX and CON animals in the OF before food restriction was imposed upon the FR and ABA groups, but after acclimation of the EX and ABA groups to the wheel. Comparison of the time spent in the center of OF revealed no group differences (two-way ANOVA, F (1,32) = 0.72, p = .40 for main factor food, F (1,32) = 0.03, p = .84 for main factor wheel, F (1,32) = .35, p = .55 for interaction) (data not shown). The time in center of OF was not correlated with the average wheel activity in baseline (R = .08, p = .74) or daily wheel activity on experimental days 2 or 3 (Table 1) for the ABA and EX groups combined. The ABA and EX groups were combined for these correlational analyses as they were identical during this period preceding the onset of food restriction.

To test whether pre-existing individual differences in the level of anxiety could predict the severity of response to ABA in terms of wheel activity, we examined the relationship between the pre-food restriction OF behavior and wheel running hyperactivity following food restriction. There was no correlation between the time spent in the center of the OF and measures of wheel activity on FR1 or FR2 of the ABA group or on Days 4 or 5 of the EX group (Table 1). It is thus evident that the response to ABA is not predicted by the anxiety level measured in the absence of food restriction.

Weight lost by the beginning of third day of food restriction is predicted by the total entries and entries into the open arms in the EPM

Weight loss is a cardinal feature of ABA and AN (APA, 2013; W. F. Epling, Pierce W. D., 1996). Since we identified a strong negative correlation between wheel activity of ABA animals during FR2 and anxiety measured by the EPM (Fig. 3), we asked whether the weight loss on FR3, resulting from wheel running during FR2, might be related to anxiety.

By FR3, ABA animals weighed 76.25 % (SEM = 0.62, N = 12) of the baseline, as measured the day before food restriction started. FR animals weighed 76.84 % (SEM = 1.4, N = 8). Weighed over the same period, EX animals were at 101.5 % of baseline (SEM = 0.89, N = 7) while CON animals were at 101.1 % (SEM = 0.59, N = 9). Two-way ANOVA revealed a strong main effect of food restriction (F (1, 31) = 711.7, p < .001) and no additional effect of wheel access (F (1,31) = 0.01, p = .91) or interaction (F (1,31) = .28, p = .6). However, for the ABA group, the weight on the last day (end of FR3) as a proportion of weight before food restriction correlated positively with the entries into the open arms (R = .58, p = .046, N = 12). The higher the number of entries made by the animal, the higher was its proportional weight and hence, the lower its weight loss. These correlations were absent in the EX, and CON groups but also notably absent in the FR group (R = .43, −.07, −.49, p = .32, .85, .38 respectively). There was also a positive correlation between weight at the end of FR3 and the total number of entries (R = .64, p = .022, N = 12) uniquely for the ABA group, and not for the EX, FR or CON (R = .43, −.41, .166, p = .32, .48, .67 respectively) groups. These data indicate that the weight loss in the ABA group is related to activity (total and open arm entries), but that relation does not exist for the FR group. Thus, the nature of weight loss in the two groups is differentiated based on access to the running wheel.

Distance traveled in the EPM is not affected by food restriction

The distance traveled in the EPM is an indicator of exploration by the animal (Lister, 1987). There were no differences among the four groups in the distance traveled in the EPM (Two-way ANOVA, F (1,32) = 1.3, p = .25 for main factor food, F (1,32) = 2.15, p = .15 for main factor wheel, F (1,32) = 3.03, p = .091 for interaction). This supports the idea that change in overall exploratory drive does not underlie the effects on anxiety-like behavior.

Wheel activity preceding food restriction does not correlate to anxiety level

Wheel activity in the baseline period indicates the preference of the animal for the running wheel but might the individual differences during this baseline period reflect pre-existing differences in anxiety? In order to answer this question, we measured the correlation of wheel running during the baseline period to anxiety. There was no correlation between the baseline running and the time spent in the center of the OF for the ABA and EX group combined (R = −.05, p = .80) (data not shown), indicating that the preference for wheel running was unrelated to anxiety level.

DISCUSSION

Animal models are crucial to understanding the underlying circuitry of the disease. Establishing the strength of a model in reproducing the disease symptomatology and biochemistry is essential. The ABA rodent model of AN has been in use since the 1960s. It is well established that ABA mimics the core phenotype of AN, including severe starvation, rapid weight loss, voluntary over-exercise, and loss of estrous cycle function (Aoki et al., 2012; Golden & Shenker, 1992; Gutierrez, 2013; Hall & Hanford, 1954; Klenotich & Dulawa, 2012). Metabolic and neurobiological similarities include hypothermia and hypoleptinemia (Bannai et al., 1988; Gelegen et al., 2008; Golden & Shenker, 1994; Hebebrand et al., 2003; Mantzoros, Flier, Lesem, Brewerton, & Jimerson, 1997; Nakazato, Hashimoto, Shimizu, Niitsu, & Iyo, 2012). However, it has not been examined whether ABA can reproduce the correlation between levels of anxiety and exercise in AN. This study set out to determine whether the ABA model can be used to understand the shared etiology and brain circuitry that underlies the co-morbidity of AN with anxiety and the relationship between anxiety and exercise in AN.

We examined whether food restriction alone or wheel access alone evokes a measurable change in anxiety and whether food restriction in combination with wheel access changed anxiety level in the ABA model. The change in anxiety was measured by conducting behavior tests just before and during food restriction. We also sought to determine whether individual differences in severity of response to ABA were related to individual differences in anxiety measured before food restriction and/or in the anxiety measured during food restriction.

The open field measurement provided a stable baseline against which to measure the change induced by food restriction

The OF measurement was performed at the end of 2 days of social isolation (for all groups) and wheel access (for ABA and EX animals). The non-food restricted groups, CON and EX, showed a correlation between the time spent in the center of the OF and time spent in the open arms of the EPM, which are the measures indicating anxiety-related behavior. The correlation suggested that even if social isolation, wheel access and other unidentified factors affected the anxiety level of the mice, these changes were already captured by the measurement in the OF. There was no further change in anxiety level in the absence of food restriction. So we conclude that the OF measurement was a stable baseline to compare with the EPM measurement, in order to obtain the effect of food restriction on anxiety behavior.

Food restriction changes the anxiety level in mice

We have found that food restriction alone as well as in combination with wheel access do evoke changes in the anxiety level of mice (two-way ANOVA Fig. 2). This is an effect of food restriction and not of the wheel access, because we see a change in anxiety levels from the pre-food restriction phase in food restricted animals (both FR and ABA) but no change in anxiety level in the EX group. Social isolation in adolescence is another known stressor (Evans, Sun, McGregor, & Connor, 2012; Gan, Bowline, Lourenco, & Pickel, 2014). However, our data rule out the contribution of social isolation upon change in anxiety exhibited by the FR and ABA group, because no change was detected among the EX or CON group which received identical durations of social isolation. Thus we have been able to isolate the effect of the food restriction on changes in the anxiety levels in the ABA model of AN.

The nature of food restriction is modified by wheel access

The FR group of mice also becomes hyperactive, as reflected by their higher number of entries in the EPM. However their weight loss was not predicted by the open or total entries in the EPM, whereas this was the case of the ABA animals. This suggests that the weight loss in ABA animals was related to activity, whereas for the FR group, it was not. Thus access to the wheel modifies the nature of the weight loss in the ABA model, further establishing the importance of excessive exercise as a key component contributing to the weight-loss aspect of severity of response to ABA.

The nature of wheel activity is modified by food restriction

The anxiety level during ABA is tightly correlated to the level of hyperactivity of the mice with higher levels of anxiety in the EPM associated with higher values of wheel activity, most notably on the day following the EPM, and somewhat to a lesser extent with running on the day preceding EPM (Fig. 3). The anxiety level measured in the EX mice was not related to their wheel activity. This difference suggests that the nature of wheel running is different under the two environmental conditions. In the presence of food restriction, wheel activity and anxiety are co-regulated but not so in absence of food restriction. The strong correlation between anxiety measurements based on EPM and wheel running indicated that we could use wheel running in the ABA mice to monitor changes in anxiety across multiple days of food restriction.

Individual variability in the change in anxiety and hyperactivity following food restriction

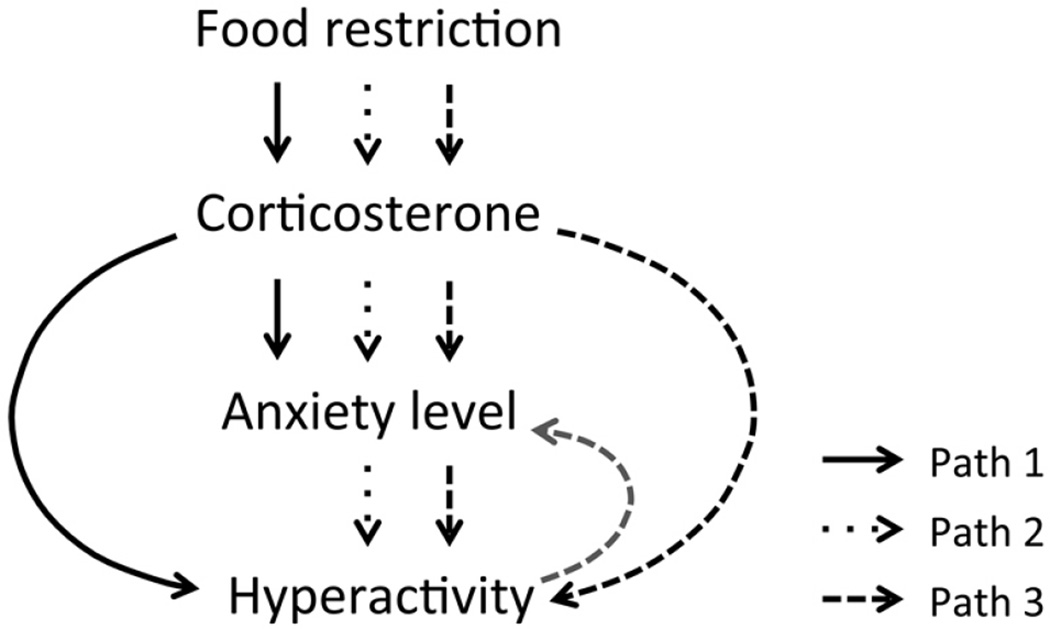

A strength of the ABA model is the individual variability in the hyperactivity response to the food restriction, which can be used to identify the mechanisms underlying the severity of response to ABA as well as resilience (Aoki et al., 2014; Chowdhury et al., 2013). In this study, we show a parallel individual variation in the change in the anxiety level induced by food restriction, both in terms of the direction and magnitude of change. Moreover, we have shown a strong correlation between the change in the level of anxiety and change in wheel activity. The strong correlation between EPM open arm time as well as fraction of entries into the open arms and wheel activity suggests three possibilities: one, anxiety and hyperactivity are co-regulated by a common neural pathway (Path 1 of Fig. 5); two, anxiety is causal to the hyperactivity in ABA (Path 2 of Fig. 5); three, a combination of the above two possibilities exists (Path 3 of Fig. 5). Finally, it must be noted that all ABA animals in this study exhibited some increase in wheel activity, including those that showed a decrease in the level of anxiety. This suggests the presence of a component mediating an increase in wheel activity following food restriction that is separable from the mechanism related to anxiogenesis. An example of such a component may be the food anticipatory activity, which is hypothesized to be regulated by food-entrainable circadian oscillators in the brain and periphery (reviewed in (Escobar, Cailotto, Angeles-Castellanos, Delgado, & Buijs, 2009; Patton & Mistlberger, 2013)).

Figure 5.

Schematic of possible pathways of regulation of anxiety and hyperactivity in the presence of food restriction. Path 1 suggests that the release of corticosterone (cort) following the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis might lead to changes in anxiety as well as hyperactivity. Path 2 suggests that cort release might lead to changes in anxiety, which generates the changes in level of wheel activity. Path 3, a combination of Paths 1 and 2, suggests that the initial rise in wheel activity following food restriction may be due to cort. Wheel activity might counter any rise in anxiety (as shown with the grey dashed line) and this feedback mechanism might increase the wheel activity further.

Potential common neural pathways regulating anxiety and hyperactivity

We propose the following neural pathway that may co-regulate anxiety and hyperactivity. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is activated following food restriction (Duclos, Bouchet, Vettier, & Richard, 2005; Duclos, Gatti, Bessiere, & Mormede, 2009), resulting in the release of corticosterone (cort). Cort rapidly increases mEPSCs in the amygdala and thus the excitability of amygdalar neurons, which might itself result in anxiogenesis (Joels, Sarabdjitsingh, & Karst, 2012). Both the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in the amygdala are involved in anxiogenesis in response to cort (Myers & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, 2007). It is conceivable that not all animals respond to the food restriction with similar level of HPA axis response and thus have different anxiety responses. For example, signaling of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor dampens the response to stress as well as the level of anxiety (Hillard, 2014). A different level of expression of this receptor may account for the individual variability in the response to stress.

Animals in the ABA paradigm show a four-fold higher level of cort relative to the EX animals, and the cort levels are tied to the level of hyperactivity (Duclos et al., 2009). Cort release in relation to feeding time may be associated with its metabolic roles in the storage of glucose or in the prevention of protein breakdown (Dallman et al., 1999). Additionally, cort is known to increase locomotor activity via increasing the dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens (Piazza et al., 1996) in the dark period, but not in the light period. Apart from cort, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), another key component of the stress response, may impact wheel running. CRH signaling at the hypothalamus and medial frontal cortex, which are suggested to play a role in motivating wheel running (Rhodes, Garland, & Gammie, 2003), might modify the reward associated with wheel running via changes in the striatum. Thus anxiety and hyperactivity could be both downstream of a pathway that is activated after stress, with anxiety not necessarily being causal to hyperactivity.

An additional region that mediates anxiety behavior is the hippocampus, where decreased excitability of the CA1 pyramidal neurons is associated with anxiolysis (Huttunen & Myers, 1986). We have shown that the GABAergic signaling in the hippocampus is negatively correlated with hyperactivity in the hippocampus (Aoki et al., 2014; Chowdhury et al., 2013), thereby suggesting another way in which the anxiety and hyperactivity could be co-regulated.

The second possibility is that anxiety is causal to hyperactivity. In support of this idea, the amygdala is shown to be causally involved in the anxiety expression (Tye et al., 2011) and to project to the striatum, the latter of which is intimately involved in the regulation of voluntary motor behavior. Why would the amygdalar projections have this effect on wheel running in the presence but not in the absence of food restriction (ABA versus EX)? Food deprivation increases the activity of amygdalar cells (Moscarello, Ben-Shahar, & Ettenberg, 2009). The amygdala has robust projections to the ventral and medial striatum, which influence behavior based on stimulus-reinforcement associations (Cador, Robbins, & Everitt, 1989; McDonald, 1998). Increased activity of these direct projections may increase the reward associated with wheel running, such that the mice increase their wheel activity.

Our previous data showed that there was a change in the GABAergic receptor expression in the amygdala following ABA, in a direction consistent with an increase in outflow from the amygdala (Wable et al., 2013). An increase in signaling to the output regions, such as the striatum, could explain the different behavior of the network under the two conditions - wheel access, with and without food restriction.

Finally, it is possible that the initial rise of wheel activity, i.e. on the first day of food restriction, is due to the direct effect of cort on the dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens (Piazza et al., 1996). Subsequently, the anxiolytic effect of exercise may act to further increase its reward value and hence, the running on the second and third day of food restriction, until the animals are too exhausted to exhibit this increased wheel activity.

Molecular markers possibly common to an individual’s response to ABA and to their level of anxiety

The possible role of the benzodiazepine (BZD)-insensitive, extrasynaptic type of GABAergic receptors in increasing hyperactivity in the ABA model (Aoki et al., 2014; Wable et al., 2013) suggest that non-BZD anxiolytics should be investigated in reducing severity of response to ABA. The lack of literature on the use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of AN suggests that they are not effective and this might be related to the role of BZD-insensitive GABAergic signaling in the brain of AN individuals. Our data offer an alternative to be explored for treating ABA, and possibly AN, using agents that up-regulate the α4-containing GABARs.

Current literature suggests that low levels of leptin could underlie the hyperactivity exhibited by individuals suffering from AN as well as rodents in ABA (Hebebrand et al., 2003). Leptin could also be tied to anxiety states (Finger, Dinan, & Cryan, 2010). Leptin receptor signaling in the midbrain dopamine neurons modulates amygdala function and expression of anxiety (Liu, Perez, Zhang, Lodge, & Lu, 2011). Thus leptin and its signaling could be a marker common to anxiety and severity of response to ABA.

The correlation between the severity of response to ABA as measured by wheel activity and the change in anxiety level induced by food restriction further provides support to the idea that anxiety and wheel activity are regulated by a common neural pathway that is activated by the stress of food restriction.

A difference between the anxiety in ABA and AN

There is one characteristic in which the model departed from the human disease. A high proportion of the individuals with a dual diagnosis of AN and anxiety develop a childhood anxiety disorder preceding the onset of AN (Kaye et al., 2004). We did not see any correlation between pre-existing anxiety level measured using open field and the extent of hyperactivity in ABA animals. While it is possible that the open field is not the most suitable test for measuring anxiety in pubertal female mice, the lack of predictability from pre-existing anxiety level is likely related to the fact that ABA can be induced in wild-type rodents without any particular predisposition to wheel running or any specific anxious phenotype. Gelegen et al. showed that more anxious mouse strains are more hyperactive in ABA than the less anxious strains (Gelegen et al., 2007). There are two differences between the Gelegen et al. study and our study: One, we analyzed individual differences by using correlation analyses between levels of activity and anxiety, rather than relying only on group comparisons of the mean values as in the Gelegen study. We measured activity and anxiety in the same mice. This was not so in the Gelegen study; the anxiety measurements were performed for the most part in male mice in separate studies ((Singer, Hill, Nadeau, & Lander, 2005; van Gaalen & Steckler, 2000) except (Ponder, Munoz, Gilliam, & Palmer, 2007) who included female mice in a study on fear conditioning, a measure related to anxiety). Two, our study was conducted upon mice in the adolescent stage of development (< 2 months old), while the subjects in the Gelegen et al. studies were 3–5 months old. It is possible that younger female mice are more vulnerable to hyperactivity induced by ABA which may explain why the C57BL6 mice in their study were reported to show no hyperactivity in response to ABA induction, while the C57BL6 mice in our study showed robust hyperactivity that were of different levels across individuals. This highlights the importance of approximating the disease as closely as possible in the animal model.

CONCLUSION

The correlative relationship between anxiety level and hyperactivity observed in the ABA animals parallels the observations reported for individuals diagnosed with AN (Breus & O’Connor, 1998; Holtkamp et al., 2004; Penas-Lledo et al., 2002; Shroff et al., 2006). These parallelisms strengthen the animal model and indicate that the ABA model can be used to understand the neural circuitry that underlies the co-morbidity of anxiety and AN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Eric Klann for lending us the open field and elevated plus maze apparatuses and to members of his laboratory, Emanuela Santini, Thu Huynh, and Aditi Bhattacharya for technical guidance with the same. We are grateful to Tara Chowdhury, Kei Tateyama, Alisa Liu, Clive Miranda and Shannon Rashid for technical assistance and helpful discussions. This work was supported by The Klarman Foundation Grant Program in Eating Disorders Research to CA, R21MH091445-01 to CA, R01NS066019-01A1 to CA, R01NS047557-07A1 to CA, NEI Core grant EY13079 to CA, R25GM097634-01 to CA, NYU’s Research Challenge Fund to CA, R21 MH105846 to CA, T32 MH019524 to GSW and Fullbright Scholarship to YC.

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflict of interest

We, the authors, have no conflict of interest.

References

- Almeida SS, Garcia RA, De Oliveira LM. Effects of early protein malnutrition and repeated testing upon locomotor and exploratory behaviors in the elevated plus-maze. Physiol Behav. 1993;54(4):749–752. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90086-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Sabaliauskas N, Chowdhury T, Min JY, Colacino AR, Laurino K, Barbarich-Marsteller NC. Adolescent female rats exhibiting activity-based anorexia express elevated levels of GABA(A) receptor alpha4 and delta subunits at the plasma membrane of hippocampal CA1 spines. Synapse. 2012;66(5):391–407. doi: 10.1002/syn.21528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Wable G, Chowdhury TG, Sabaliauskas NA, Laurino K, Barbarich-Marsteller NC. alpha4betadelta-GABAARs in the hippocampal CA1 as a biomarker for resilience to activity-based anorexia. Neuroscience. 2014;265:108–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5 ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bannai C, Kuzuya N, Koide Y, Fujita T, Itakura M, Kawai K, Yamashita K. Assessment of the relationship between serum thyroid hormone levels and peripheral metabolism in patients with anorexia nervosa. Endocrinol Jpn. 1988;35(3):455–462. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.35.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham CL, Su J, Hlynsky JA, Goldner EM, Gao M. The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(2):143–146. doi: 10.1002/eat.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond Nigel, Giusto Eros Di. OPEN-FIELD BEHAVIOR AS A FUNCTION OF AGE, SEX, AND REPEATED TRIALS. Psychological Reports. 1977;41(2):571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Breus MJ, O’Connor PJ. Exercise-induced anxiolysis: a test of the "time out" hypothesis in high anxious females. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(7):1107–1112. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein Paul M. Repeated trials with the albino rat in the open field as a function of age and deprivation. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology. 1972;81(1):84. doi: 10.1037/h0033361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRONSTEIN PAULM. Replication report: Age and open-field activity of rats. Psychological Reports. 1973;32(2):403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein Paul M, Wolkoff F Dmitri, Levine M Jov. Sex-related differences in rats’ open-field activity. Behavioral biology. 1975;13(1):133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)90913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Slof-Op't Landt MC, van Furth EF, Sullivan PF. The genetics of anorexia nervosa. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:263–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cador M, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Involvement of the amygdala in stimulus-reward associations: interaction with the ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1989;30(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carola V, D'Olimpio F, Brunamonti E, Mangia F, Renzi P. Evaluation of the elevated plus-maze and open-field tests for the assessment of anxiety-related behaviour in inbred mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;134(1–2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury Tara G, Wable Gauri S, Sabaliauskas Nicole A, Aoki Chiye. Adolescent female C57BL/6 mice with vulnerability to activity-based anorexia exhibit weak inhibitory input onto hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2013;241:250–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Bhatnagar S, Bell ME, Choi S, Chu A, Viau V. Starvation: early signals, sensors, and sequelae. Endocrinology. 1999;140(9):4015–4023. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Katzman DK, Kirsh C. Compulsive physical activity in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a psychobehavioral spiral of pathology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(6):336–342. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclos M, Bouchet M, Vettier A, Richard D. Genetic differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and food restriction-induced hyperactivity in three inbred strains of rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17(11):740–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclos M, Gatti C, Bessiere B, Mormede P. Tonic and phasic effects of corticosterone on food restriction-induced hyperactivity in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(3):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epling WF, Pierce WD. Activity Anorexia. Theory, Research, and Treatment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Epling WF, Pierce D, Stefan L. A theory of activity-based anorexia. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1983;3:26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar Carolina, Cailotto Cathy, Angeles-Castellanos Manuel, Delgado Roberto Salgado, Buijs Ruud M. Peripheral oscillators: the driving force for food-anticipatory activity. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30(9):1665–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Sun Y, McGregor A, Connor B. Allopregnanolone regulates neurogenesis and depressive/anxiety-like behaviour in a social isolation rodent model of chronic stress. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(8):1315–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):407–416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File Sandra E. The interplay of learning and anxiety in the elevated plus-maze. Behav Brain Res. 1993;58(1):199–202. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90103-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File Sandra E, Mabbutt Peter S, Hitchcott Paul K. Characterisation of the phenomenon of “one-trial tolerance” to the anxiolytic effect of chlordiazepoxide in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;102(1):98–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02245751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger BC, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Leptin-deficient mice retain normal appetitive spatial learning yet exhibit marked increases in anxiety-related behaviours. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210(4):559–568. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1858-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore F, Ruggiero GM, Sassaroli S. Emotional dysregulation and anxiety control in the psychopathological mechanism underlying drive for thinness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:43. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan JO, Bowline E, Lourenco FS, Pickel VM. Adolescent social isolation enhances the plasmalemmal density of NMDA NR1 subunits in dendritic spines of principal neurons in the basolateral amygdala of adult mice. Neuroscience. 2014;258:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelegen C, Collier DA, Campbell IC, Oppelaar H, van den Heuvel J, Adan RA, Kas MJ. Difference in susceptibility to activity-based anorexia in two inbred strains of mice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelegen C, van den Heuvel J, Collier DA, Campbell IC, Oppelaar H, Hessel E, Kas MJ. Dopaminergic and brain-derived neurotrophic factor signalling in inbred mice exposed to a restricted feeding schedule. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(5):552–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden NH, Shenker IR. Amenorrhrea in Anorexia Nervosa: Etiology and Implications. Adolesc Med. 1992;3(3):503–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden NH, Shenker IR. Amenorrhea in anorexia nervosa. Neuroendocrine control of hypothalamic dysfunction. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(1):53–60. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199407)16:1<53::aid-eat2260160105>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E. A rat in the labyrinth of anorexia nervosa: Contributions of the activity-based anorexia rodent model to the understanding of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1002/eat.22095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JF, Hanford PV. Activity as a function of a restricted feeding schedule. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1954;47(5):362–363. doi: 10.1037/h0060276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebebrand J, Exner C, Hebebrand K, Holtkamp C, Casper RC, Remschmidt H, Klingenspor M. Hyperactivity in patients with anorexia nervosa and in semistarved rats: evidence for a pivotal role of hypoleptinemia. Physiol Behav. 2003;79(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ. Stress regulates endocannabinoid-CB1 receptor signaling. Semin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp K, Hebebrand J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. The contribution of anxiety and food restriction on physical activity levels in acute anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36(2):163–171. doi: 10.1002/eat.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen P, Myers RD. Tetrahydro-beta-carboline micro-injected into the hippocampus induces an anxiety-like state in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24(6):1733–1738. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Sarabdjitsingh RA, Karst H. Unraveling the time domains of corticosteroid hormone influences on brain activity: rapid, slow, and chronic modes. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(4):901–938. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierniesky Nicholas, Sick Thomas, Kruppenbacher Frank. OPEN-FIELD ACTIVITY OF ALBINO RATS AS A FUNCTION OF SEX, AGE, AND REPEATED TESTING. Psychological Reports. 1977;40(3c):1255–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Klenotich SJ, Dulawa SC. The activity-based anorexia mouse model. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;829:377–393. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-458-2_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Claire, Rodgers RJ. Antinociceptive effects of elevated plus-maze exposure: influence of opiate receptor manipulations. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;102(4):507–513. doi: 10.1007/BF02247133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister RG. The use of a plus-maze to measure anxiety in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;92(2):180–185. doi: 10.1007/BF00177912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Perez SM, Zhang W, Lodge DJ, Lu XY. Selective deletion of the leptin receptor in dopamine neurons produces anxiogenic-like behavior and increases dopaminergic activity in amygdala. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(10):1024–1038. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzoros C, Flier JS, Lesem MD, Brewerton TD, Jimerson DC. Cerebrospinal fluid leptin in anorexia nervosa: correlation with nutritional status and potential role in resistance to weight gain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(6):1845–1851. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55(3):257–332. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscarello JM, Ben-Shahar O, Ettenberg A. Effects of food deprivation on goal-directed behavior, spontaneous locomotion, and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the amygdala. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Corticosteroid receptor-mediated mechanisms in the amygdala regulate anxiety and colonic sensitivity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(6):G1622–G1629. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00080.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato M, Hashimoto K, Shimizu E, Niitsu T, Iyo M. Possible involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in eating disorders. IUBMB Life. 2012;64(5):355–361. doi: 10.1002/iub.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton Danica F, Mistlberger Ralph E. Circadian adaptations to meal timing: neuroendocrine mechanisms. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas-Lledo E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G. Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31(4):370–375. doi: 10.1002/eat.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Maccari S, Simon H, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids have state-dependent stimulant effects on the mesencephalic dopaminergic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(16):8716–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder CA, Munoz M, Gilliam TC, Palmer AA. Genetic architecture of fear conditioning in chromosome substitution strains: relationship to measures of innate (unlearned) anxiety-like behavior. Mamm Genome. 2007;18(4):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Garland T, Jr, Gammie SC. Patterns of brain activity associated with variation in voluntary wheel-running behavior. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117(6):1243–1256. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJohn, Lee C, Shepherd Jon K. Effects of diazepam on behavioural and antinociceptive responses to the elevated plus-maze in male mice depend upon treatment regimen and prior maze experience. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;106(1):102–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02253596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Shepherd JK. Influence of prior maze experience on behaviour and response to diazepam in the elevated plus-maze and light/dark tests of anxiety in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113(2):237–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02245704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routtenberg A, Kuznesof AW. Self-starvation of rats living in activity wheels on a restricted feeding schedule. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1967;64(3):414–421. doi: 10.1037/h0025205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PA, Williams DI. Effects of repeated testing on rats’ locomotor activity in the open-field. Animal Behaviour. 1973;21(1):109–111. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3472(73)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciolino NR, Holmes PV. Exercise offers anxiolytic potential: a role for stress and brain noradrenergic-galaninergic mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(9):1965–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, Tozzi F, Klump KL, Berrettini WH, Bulik CM. Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(6):454–461. doi: 10.1002/eat.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JB, Hill AE, Nadeau JH, Lander ES. Mapping quantitative trait loci for anxiety in chromosome substitution strains of mice. Genetics. 2005;169(2):855–862. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF. Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1073–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treit Dallas, Menard Janet, Royan Cary. Anxiogenic stimuli in the elevated plus-maze. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;44(2):463–469. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90492-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye KM, Prakash R, Kim SY, Fenno LE, Grosenick L, Zarabi H, Deisseroth K. Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety. Nature. 2011;471(7338):358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature09820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle Fred P. Rats’ performance on repeated tests in the open field as a function of age. Psychonomic science. 1971;23(5):333–334. [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen MM, Steckler T. Behavioural analysis of four mouse strains in an anxiety test battery. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wable Gauri S, Barbarich-Marsteller Nicole C, Chowdhury Tara G, Sabaliauskas Nicole A, Farb Claudia R, Aoki Chiye. Excitatory synapses on dendritic shafts of the caudal basal amygdala exhibit elevated levels of GABAA receptor α4 subunits following the induction of activity-based anorexia. Synapse. 2013;68(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/syn.21690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):322–328. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.