Abstract

Objectives

To further elucidate anti-cancer mechanisms of metformin again pancreatic cancer, we evaluated inhibitory effects of metformin on pancreatic tumorigenesis in a genetically-engineered mouse model, and investigated its possible anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenesis effects.

Methods

Six-week old LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53F2-10 mice (10 per group) were administered once daily intraperitoneally with saline (control) for one week or metformin (125 mg/kg) for one week (Met_1wk) or three weeks (Met_3wk) prior to tumor initiation. All mice continued with their respective injections for six weeks post-tumor initiation. Molecular changes were evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, and Western blotting.

Results

At euthanasia, pancreatic tumor volume in Met_1wk (median, 181.8 mm3) and Met_3wk (median, 137.9 mm3) groups was significantly lower than the control group (median, 481.1 mm3) (P = 0.001 and 0.0009, respectively). No significant difference was observed between Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups (P = 0.51). These results were further confirmed using tumor weight and tumor burden measurements. Furthermore, metformin treatment decreased the phosphorylation of nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) as well as the expression of Sp1 transcription factor and several NFκB-regulated genes.

Conclusions

Metformin may inhibit pancreatic tumorigenesis by modulating multiple molecular targets in inflammatory pathways.

Keywords: Metformin, inflammation, chemoprevention, pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Metformin (1,1-dimethylbiguanide hydrochloride), a biguanide derivate, is the most widely prescribed drug to treat hyperglycemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes. In addition to its use for diabetes, metformin is also effective in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome and is being explored as an antiviral and anticancer agent. More recently, metformin use has been associated with decreased risk of specific cancers including prostate, colon, liver, pancreas, and breast cancers.1–7 These observations are consistent with in vitro and in vivo studies showing the anti-proliferative action of metformin on various cancer cell lines8 and several cancers in animal tumor models.9–16

Several epidemiological studies have linked the administration of metformin with a reduced risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.2, 5, 6 Li et al.2, for example, reported that the risk of developing pancreatic cancer in metformin users reduced by 62%, compared with metformin non-users (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.22–0.69, P = 0.001). Furthermore, a retrospective study from Sadeghi and colleagues involving diabetic patients with pancreatic cancer showed improved survival for patients using metformin as diabetes treatment.17 Metformin has also been shown to prevent the promotional effect of high-fat diet on N-nitrosobis(2-oxopropyl)amine (BOP)-induced pancreatic carcinogenesis in Syrian hamsters9 and to inhibit the pancreatic cancer cell growth in xenograft models using athymic nude mice.10, 18, 19 These results suggest a role of metformin in preventive and/or therapeutic strategies against pancreatic cancer. However, the molecular mechanism by which metformin elicits its anti-cancer effects has not been fully established.

It has long been recognized that a genetic mouse model of pancreatic cancer is useful for investigating strategies of prevention and treatment. A recent study showed that metformin prevents the progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) by targeting in part cancer stem cells and mTOR signaling in p48Cre/+.LSL-KrasG12D/+ transgenic mice.20 Ninety-five percent of patients with pre-cancerous lesions of the pancreas and PDAC have an activating point mutation of Kras oncogene.21–23 Somatic point mutations of the TP53 tumor suppressor have been identified in approximately 75% of pancreatic cancers.24 Based on these data and our understanding of genetic events driving pancreatic carcinogenesis, we have developed a genetically engineered LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53F2-10 transgenic mouse model, as described originally by Hingorani et al..25 The mice develop an invasive and undifferentiated form of pancreatic cancer in a relatively short time period.

In this study, we utilized this model to evaluate the effects of metformin on the inhibition of pancreatic tumorigenesis and the modulation of inflammatory and angiogenesis pathways. We report that metformin treatment significantly decreased pancreatic tumor volume, tumor weight, and tumor burden and down-regulated nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signalling pathways by the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). This study indicated that metformin might be a potential novel approach for pancreatic cancer prevention and treatment by modulating key molecular markers of the inflammatory pathway during the progression of pancreatic lesions. Further investigations are warranted into elucidating its precise anti-inflammatory mechanisms and its differential effects on prevention vs. treatment for pancreatic cancer.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Metformin (purity 97% by high-performance liquid chromatography) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). 0.9% sodium chloride (Saline) solution was purchased from Hopsira Inc. (Lake Forest, IL). Antibodies to AMPKα (D63G4), phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (40H9), AMPKβ1 (71C10), phospho-AMPKβ1 (Ser108), NFκB p65 (C22B4), phospho-NFκB p65 (Ser536) (93H1), STAT3 (79D7), phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) (D3A7), specificity protein 1 (Sp1), vascular endothelial growth factor α (VEGFα) and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunolab (West Grove, PA).

Animal experiments

Conditional mutant LSL-KrasG12D and LSL-Trp53F2-10 mice, as previously described25–27, were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MI). The heterozygous of LSL-KrasG12D and homozygous of LSL-Trp53F2-10 mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility and were interbred stepwise to generate the cohorts of LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53F2-10 mice (Kras+/−;Trp53−/−) used in this study. Prior to any experiments, DNA was extracted from tail tissue using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia CA) and genotyped by PCR to confirm the presence of the Kras and Trp53 transgene constructs. The following PCR conditions were used for Trp53: 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min; for Kras: 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 62°C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min.

Thirty genotyped LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53F2-10 mice (15 male and 15 female) at the ages of 6 weeks were randomized based on initial body weights into three experimental groups: (1) vehicle control; (2) 1-week pretreated metformin (Met_1Wk); and (3) 3-week pretreated metformin (Met_3Wk), and males and females were evenly balanced over the three groups. At the timepoint described below, 50 µL of adenoviral Cre recombinase construct Ad5CMVCre (3 × 1010 pfu/mL) (Gene Transfer Vector Core, University of Iowa) was injected orthotopically into the head of pancreas in each mouse. Cre-mediated recombination can catalyze the conditional targeted mutation, KrasG12D and Trp53F2-10, by excising the loxP-flanked stop codon in Kras and loxP-flanked exons 2 to 10 of Trp53. Controlling the time of adenovirus injection allows us to manage the timing of initiation of pancreatic tumor development for prevention studies.

To determine a suitable metformin dose for our study, we carefully reviewed the available data. Limited studies have been undertaken in several different animal models. For example, the growth of MIAPaca2 and PANC1 tumor xenografts were suppressed by 250 mg/kg metformin given once daily by intraperitoneal (i.p.).28 In Syrian Hamsters fed a high-fat diet with chemically-induced pancreatic tumors metformin at a dose of 320 mg/kg body weight reduced malignant lesions to 0% compared to 50% in untreated hamsters.9 According to the formula published by Reagan-Shaw et al.29, human equivalent dose (mg/kg) = animal dose (mg/kg) × animal Km/human Km, where species and Km values are based on body surface area (Km for adult human [60 kg] is 37 and mouse [20 g] is 3). Based on this formula and prior studies, we administrate metformin daily by i.p. injection at 125 mg/kg in 150 µL saline, which is equivalent to human dose of 600 mg/average size person of 60 kg. This dose is about four times lower than the maximum safe dose of metformin 2500 mg/d recommended in the Physician’s Desk Reference. For metformin-treated groups, metformin was administered one week (Met_1wk) or three weeks (Met_3Wk) prior to the adenovirus injection. Control animals received the same volume of 0.9% saline starting at one week prior to the adenovirus injection. All three groups continued with their respective injections for 6 weeks following adenovirus injection.

The mice were monitored daily for any signs of toxicity or abnormalities. Body weight for each animal was measured once a week and blood glucose levels were monitored every other week using blood from tail vein. Two mice (one in the control group, one in Met_3wk group) died after one day of adenovirus injection. Animals still living 42 days post-adenovirus injection were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and necropsied. This study were approved and conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Tissue processing and staining

The pancreas, liver and spleen were immediately harvested from the sacrificed mice, and tumor weight and tumor measurements were recorded for the excised pancreatic tumors. All tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. Four-micrometer-thick consecutive sections were cut and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC). For IHC, the following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-phospho-NFκB p65 (Ser536) (93H1) at 1:100, rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr 705) (D3A7) at 1:25, rabbit anti-Sp1 at 1:200, and rabbit anti-VEGFα at 1:1200. The biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies at 1:500 were used as secondary antibodies. All slides were reviewed by a single pathologist (T.S.) blinded to the experimental conditions. Any PanINs were noted and graded. All invasive tumors were graded and any subtypes (sarcomatoid, anaplastic) were noted. Intra-tumoral inflammation was assessed semi-quantitatively and separately for neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells.

RNA and protein extraction

Approximately 20 mg of fresh pancreas tissues from each mouse were washed with PBS and stored immediately in Allprotect Tissue Reagent (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia CA). Within one week, the tissues were removed from −80°C storage to isolate the total RNA and protein using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Following the extractions, total RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Biolab, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia), and protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford method (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Total RNA and protein samples were stored at −80 °C until needed.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR

Quantitative gene expression analysis was performed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with the Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit (AB Foster CA) using the ABI StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primers for transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1β, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, VEGFα, thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were purchased from QIAGEN Inc. (Valencia CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed according to the following protocol: 30 min at 48°C, 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 thermal cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, and 60 seconds at 60°C for extension. Results were normalized to β-actin mRNA as an internal control and reported as relative mRNA levels.

Western blot assay

Twenty micrograms of total proteins from each tissue sample were loaded and separated on a gradient 4–20% polyacrylamide gel and electophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST, 20mM Tris, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for one hour at room temperature, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with polyclonal antibodies to mouse AMPKα (D63G4), phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (40H9), AMPKβ1 (71C10), phospho-AMPKβ1 (Ser108), NF-κB p65 (C22B4), phospho-NFκB p65 (Ser536) (93H1), STAT3 (79D7), phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) (D3A7) and β-actin. All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000. Blots were subsequently washed three times with TBST and then incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies one hour at room temperature. After three additional TBST washes, the immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The levels of β-actin were estimated to check for equal samples loading. Films were scanned and band densities were quantified with densitometric analysis using Scion Image (Epson GT-X700, Tokyo, Japan).

Data analyses

Measurements were collected from all three animal groups. The volumes (V) of the excised tumors were measured with an external caliper and calculated as V = 0.52 (length × width × depth), and the tumor burden was calculated as tumor weight (mg) / body weight (mg) × 100. The mRNA and protein expression for the target genes were first quantitated relative to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin, and then normalized to the background expression in saline-treated mice (Control). The differences among the three groups were tested using Kruskal-Wallis test. When the Kruskal-Wallis test was significant, pairwise comparisons were assessed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for each pair of groups; all comparisons are reported for the reader to interpret. All statistical analyses were done with SAS 9.2 software, and two sided P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Activation of KRASG12D and knocking out Trp53F2-10 at mouse pancreas

We have developed a unique method of enabling an investigator-generated invasive and undifferentiated form of pancreatic cancer in a mouse model as described originally by Hingorani et al.25. To directly address the questions concerning the requirements for tumor progression, we have targeted the endogenous expression of Trp53F2-10, an ortholog of one of the most common TP53 mutations in human pancreatic cancer,30 in progenitor cells of the mouse pancreas. We found that physiological expression of Trp53F2-10, with endogenous KrasG12D expression, promotes the development of an invasive and widely metastatic undifferentiated form pancreatic cancer that shares the key clinical, histopathological, and genomic features of human undifferentiated form of pancreatic cancer.24 An existing mouse model of pancreatic cancer, the Hingorani model,24 uses interbreeding with Pdx-1-Cre transgenic mice to activate both the LSL-KrasG12D/+ and Trp53R172H/+ alleles in progenitor cells of the developing mouse pancreas. These KrasG12D;Trp53R172H mice develop pancreatic cancer and have a median survival of about 5 months. In contrast, we generated our transgenic model by orthotopically injecting adenoviral Cre into the head of the mouse pancreas to stimulate the activation of Kras and Trp53 mutations. The mice develop one highly aggressive undifferentiated pancreatic cancer at the place where the adenoviral Cre was injected in approximately three weeks, and liver metastases are observed within four weeks (data not shown). The median survival of these mice is two months.

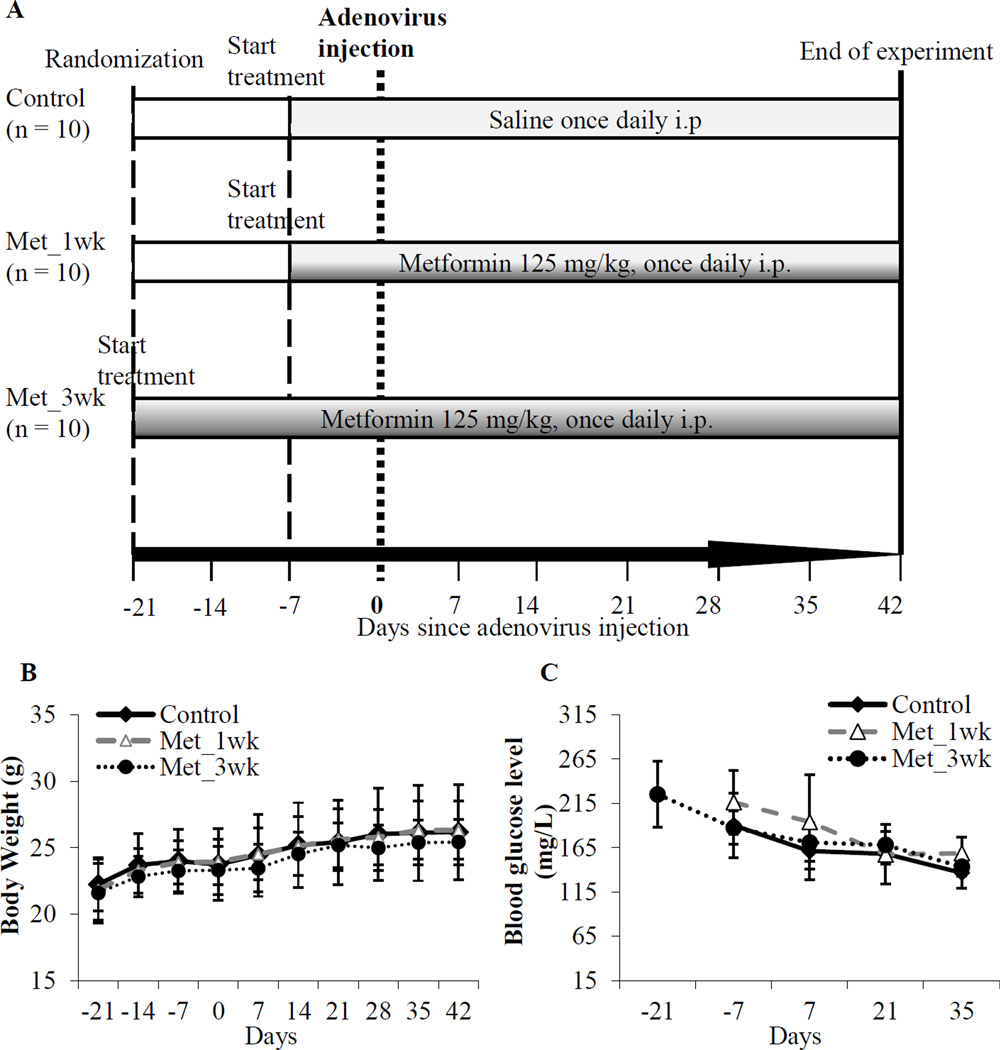

A total of 30 mice were randomly divided into three groups (Figure 1A). No significant difference in body weight changes was observed among metformin-treated groups and the control group during the course of the experiment (Table 1, Figure 1B). Similarly, no significant differences in blood glucose levels were detected among all three experimental groups (Table 1, Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Study on preventive efficacy of metformin in Kras+/−;Trp53−/− mice.

(A) Experimental design: Thirty mice were randomized into control and two metformin-treated groups: Met_1wk and Met_3wk (10 mice per group). At about 6 weeks of age, mouse controls were treated once daily with saline by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections starting at one week prior to adenovirus injection. For metformin treated groups, metformin (125 mg/kg in 150 µL saline) were administered once daily by i.p. injection one week prior to adenovirus injection (Met_1wk) or three weeks prior to adenovirus injection (Met_3wk). (B) Measurements of body weight of the mice. All mice were monitored daily for any discomfort; body weight was measured weekly; (C) Measurements of blood glucose levels of the mice. Blood glucose levels were monitored every other week using the tail blood samples. No significant changes in body weight (B) or blood glucose (C) were observed in the control and metformin treated mice.

Table 1.

Characteristics of experimental groups of mice at time of sacrifice.

| Controls (n = 9 ) | Met_1wk (n = 10) | Met_3wk (n = 9) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic tumor volume (mm3) | ||||

| Median (IQRe) | 481.1 (442, 551) | 181.8 (120, 256) | 137.9 (100, 202) | 0.0006 |

| P value | 0.0011b | 0.0009b, 0.5136c | ||

| Pancreatic tumor weight (mg) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 551.1 (428, 578) | 248.4 (178, 316) | 266.7 (201, 285) | 0.0039 |

| P value | 0.0033b | 0.0054b, 0.6831c | ||

| Pancreatic tumor burdend (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.97 (1.42, 2.44) | 1.00 (0.68,1.18) | 1.00 (0.79, 1.09) | 0.0076 |

| P value | 0.0055b | 0.0092b, 0.8703c | ||

| Body weight change (g) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.5 (1.3, 5.3) | 4.3 (2.5, 5.8) | 3.8 (2.4, 5.0) | 0.6744 |

| P value | 0.4375b | 1.00b, 0.4622c | ||

| Blood glucose change (mg/L) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | −54.0 (−73, −33) | −51.5 (−68, −27) | −73.0 (−99, −59) | 0.1200 |

| P value | 0.5676b | 0.0932b, 0.0724c |

Kruskal-Wallis test for all groups,

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for Met-1wk vs. Controls or Met-3wk vs. controls

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for Met-3wk vs. Met-1wk

Tumor burden was calculated as tumor weight (mg) / body weight (mg) × 100

IQR – Interquartile Range (25th %, 75th %)

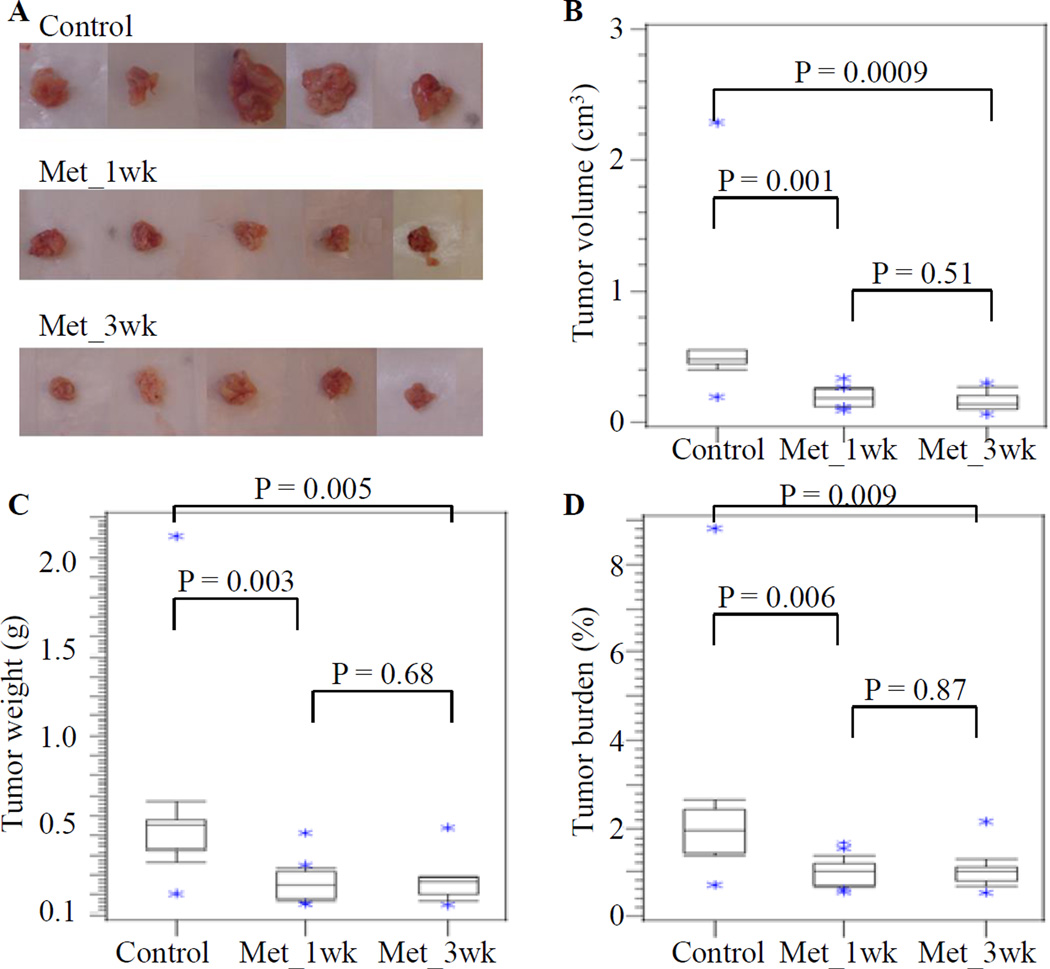

Effect of metformin on pancreatic tumor volume, tumor weight, and tumor burden

Metformin treatment significantly decreased the size of pancreatic tumors compared to those from the untreated control group. Representative photographs of the mouse pancreatic tumors from different groups are shown in Figure 2A. The tumor volumes (median ± standard error of the means (SEM)) were 481.1 ± 207.7 mm3, 181.8 ± 24.6 mm3 and 137.9 ± 26.8, and the tumor weights (median ± SEM) were 551.1 ± 176.6 mg, 248.4 ± 35.3 mg and 266.7 ± 38.7 mg for the control and Met-1wk and Met-3wk groups, respectively (Table 1). By Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the tumor volumes in Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups were significantly lower than the control group (P = 0.001 for Met_1wk versus control, and P = 0.0009 for Met_3wk versus control), while no significant difference in tumor volumes was observed between Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups (P = 0.51) (Table 1, Figure 2B). Similar results were also observed using the criteria of tumor weight and tumor burden (Table 1, Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2. Metformin inhibits the pancreatic tumor growth in a novel genetically engineered pancreatic cancer mouse model.

(A) Representative gross morphology showed the excised pancreatic tumors at the last day of the experiment (42 days from the adenovirus injection). Using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, parameters including tumor volume (B), tumor weight (C) and tumor burden (D) in the Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups were significantly lower than in the control group. No significant differences in tumor volume, tumor weight and tumor burden were found between the Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups.

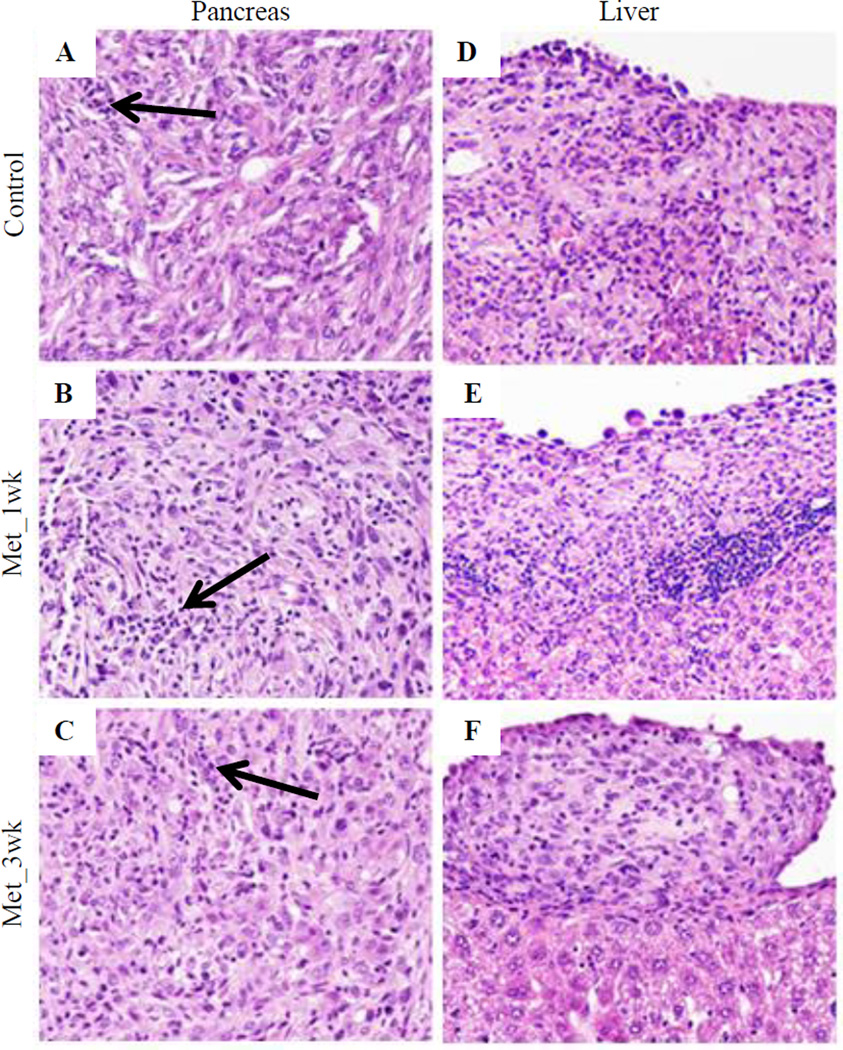

Effect of metformin on pancreatic histology

There was no significant difference in the extent or grade of PanINs (data not shown). All tumors were poorly differentiated carcinomas with sarcomatoid, anaplastic (giant-cell) and, focally, gland-forming areas. All tumors were locally invasive, with invasion into diaphragm, adjacent gut and liver capsule. There was no statistically significant difference in the intra-tumoral inflammatory infiltrate assessed for neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 3A–3C and Supplementary Table 1). Liver metastases were observed in all groups (Figures 3D–3F), but we were unable to show differences between the experimental groups for any aspect of histology.

Figure 3. Representative photomicrographs of H&E stained section for pancreatic tumors and liver metastasis.

(A–C) H&E stained section showing pancreatic tumors in Control (A), Met_1wk (B) and Met_3wk (C); (D–F) H&E stained section showing liver metastasis in Control (D), Met_1wk (E) and Met_3wk (F). Arrow indicated the intra-tumoral inflammatory infiltrate.

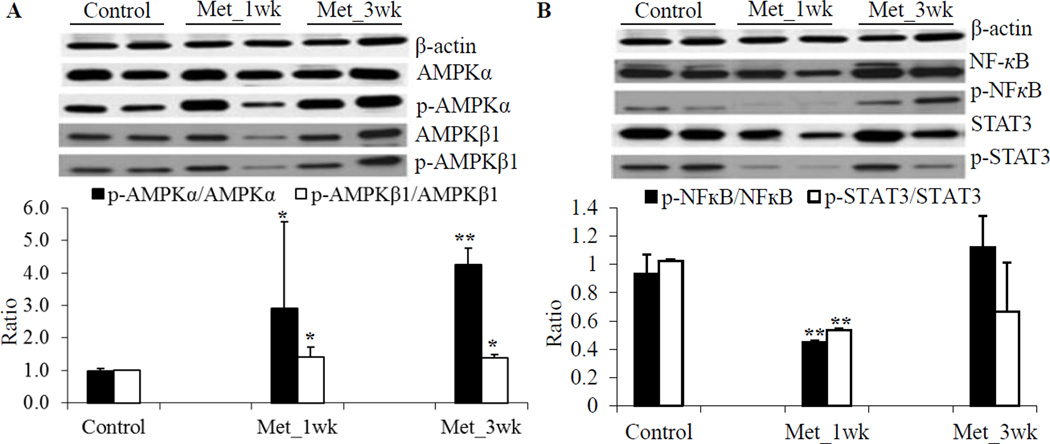

Effect of metformin on AMPK, NFκB, STAT3 and Sp1

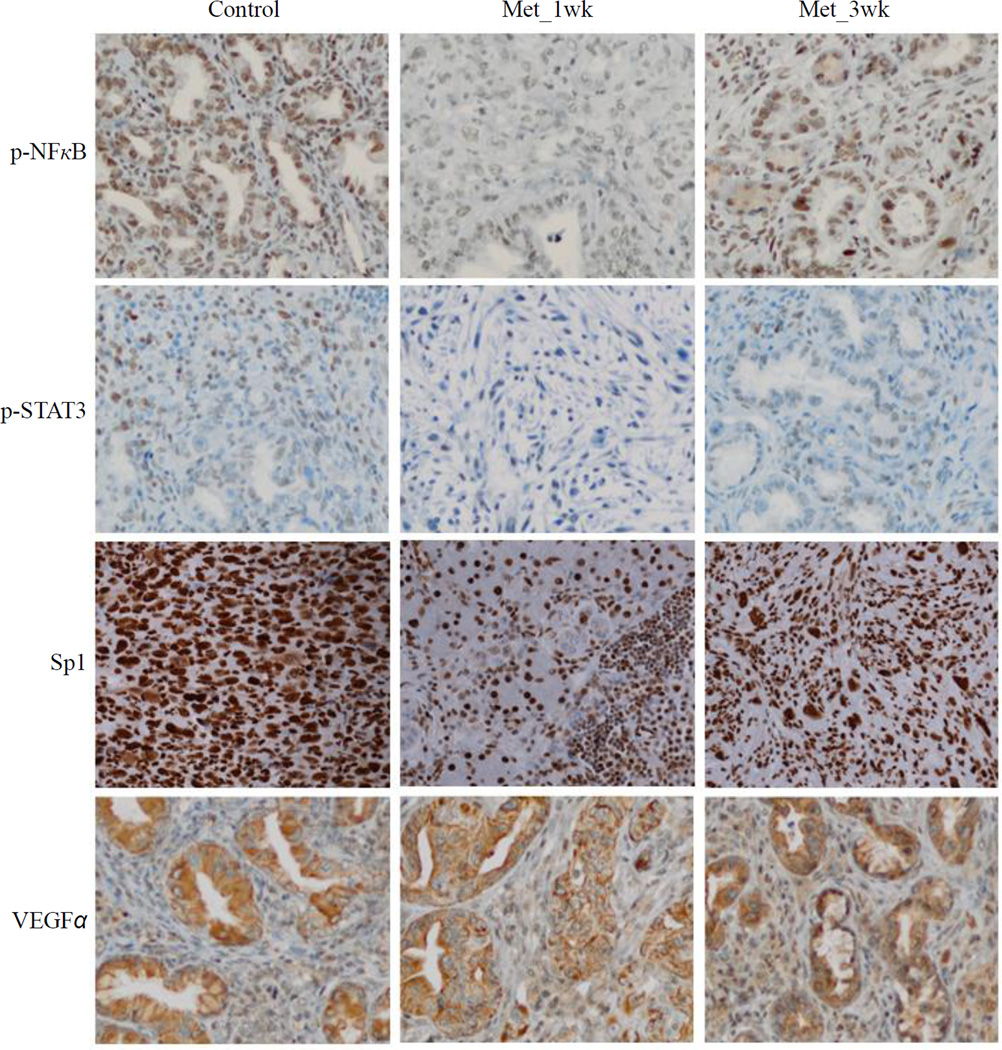

The effects of metformin have been essentially attributed to its ability to activate the AMPK pathway31. Thus, we investigated if metformin activates the AMPK pathway in pancreas of these transgenic mice. Although a great variability in induction of the phosphorylation of AMPKα was observed, metformin treatment significantly induced the phosphorylation of AMPKβ1 on Ser108 and of AMPKα on Thr172, (Figure 4A). It has also been suggested that metformin attenuates the cytokine-induced expression of proinflammatory and adhesion molecular genes in vitro by suppressing NFκB activation via AMPK activation32. Non-phosphorylated STAT3 has been shown to play important roles in cellular function, including binding to NFκB to mediate its nuclear import33. We examined the effect of metformin on NFκB and STAT3 activation by looking for changes in the level of total protein as well as changes in their phosphorylation levels. We observed that one-week pretreatment of metformin significantly reduced phospho-NFκB at the serine phosphorylation site and phospho-STAT3 at the tyrosine phosphorylation site, but total protein levels were unchanged (Figure 4B). The IHC staining also showed that metformin significantly reduced phospho-NFκB and phospho-STAT3 in one-week pretreated group, but not 3-week pretreated group (Figure 5). Numerous studies indicated that specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors including Sp1 and other family members (Sp3 and Sp4) are highly expressed in pancreatic cancer and play a critical role in pancreatic tumorigenesis.34–36 Moreover, Sp1 was reported to be a negative prognostic factor to pancreatic cancer patient survival.37 A recent study also suggested an interaction and a striking similarity between Sp- and NFκB-dependent growth inhibitory, angiogenesis and survival response and genes.36 We determined the Sp1 expression in control and metformin-treated tumors by the IHC staining and demonstrated that metformin significantly reduced Sp1 expression in one-week pretreated group, and slightly decreased in 3-week pretreated group (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Metformin effects on modulation of protein expression of AMPKα, AMPKβ, NF-κB and STAT3 in pancreatic tumors.

(A) Protein expression of of AMPKα and AMPKβ. (B) Protein expression of of NFκB and STAT3. The upper panel shows representative results of Western blot, and the lower panel shows densitometry analyses of the relative protein expression. Values are expressed as fold of the saline-treated control and are means ± SEM, n = 4. Metformin treatment significantly induced the phosphorylation of AMPKα, and AMPKβ1. Phospho-NFκB and phospho-STAT3 significantly decreased in Met_1wk, but not in Met_3wk, compared to the saline-treated control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemistry staining for phospho-NFκB, phospho-STAT3, Sp1 and VEGFα in Control, Met_1wk, and Met_3wk groups.

Metformin significantly reduced phospho-NFκB, phospho-STAT3 and Sp1 expression in one-week pretreated group, while the VEGFα expression was not significantly changed among the three groups.

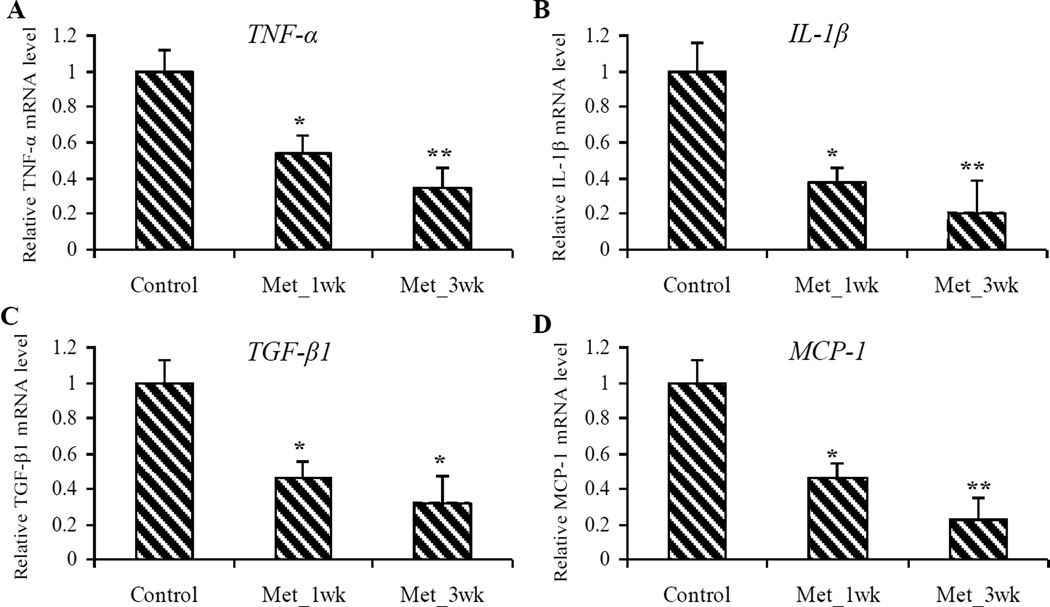

Effects of metformin on anti-inflammation

NFκB, a master transcriptional gene, has been known to activate downstream inflammatory mediators, such as TGF-β1, TNF-α, and IL-1β.38–40 In addition, activated NFκB shows an important role in the up-regulation of MCP-1 which is a potent chemokine involved in the accumulation and function of macrophages.40–42 We investigated the effects of metformin on the mRNA expression of these downstream regulatory genes of NFκB signaling pathway in mouse pancreatic tissue. Metformin treatment significantly reduced mRNA expression of TNF-α (up to 65%, P < 0.01) TGF-β1 (up to 70%, P < 0.05), MCP-1 (up to 77%, P < 0.01), and IL-1β (up to 80%, P < 0.01), compared to the untreated control samples (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Metformin decreased mRNA expression of the downstream inflammatory mediators in pancreatic tumors.

(A–D) Relative mRNA expression of TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), TGF-β1 (C) and MCP-1 (D) in pancreatic tumors. Values are expressed as fold of the saline-treated control and are means ± SEM, n = 9 or 10 means of triplicate measures. Significantly decreased mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, TGF-β1 and MCP-1 was observed among metformin-treated groups (Met_1wk and Met_3wk), compared to the saline-treated control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

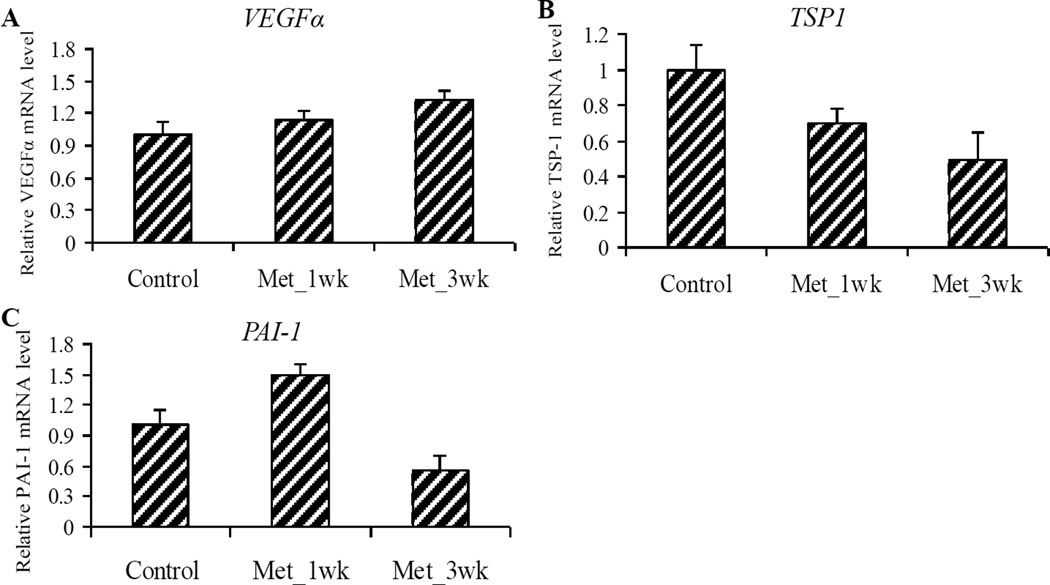

Effects of metformin on anti-angiogenesis

It has previously been demonstrated that AMPK activation can contribute to increased VEGF expression43, 44 and angiogenesis.45, 46 VEGF is a well-established stimulator of vascular permeability and angiogenesis, whereas TSP-1, originally isolated from platelets and megakaryocytes, is a potential angiogenic inhibitor.47 PAI-1 expression is positively correlated with TSP-1, and can either enhance or inhibit angiogenesis, depending upon its concentration.48 The IHC staining showed that the protein level of VEGFα was not significantly changed among the three groups (Figure 5). We also determined the mRNA expression of these three important angiogenic genes and demonstrated that although metformin treatment increased the VEGFα mRNA level and decreased the TSP-1 mRNA level, the reductions were not statistically significant (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Metformin modulated mRNA expression of the angiogenic genes in pancreatic tumors.

(A–C) Relative mRNA expression of VEGFα (A), TSP-1 (B) and PAI-1 (C) in pancreatic tumors. Values are expressed as fold of the saline-treated control and are means ± SEM, n = 9 or 10 means of triplicate measures. No statistically significant changes of mRNA expression of VEGFα, TSP-1 and PAI-1 were observed in metformin treated groups (Met_1wk and Met_3wk), compared to the untreated control.

Discussion

In this study, we show that metformin treatment significantly decreased pancreatic tumor volume, tumor weight, and tumor burden in mice. The mouse model used in this study captures many significant features of human undifferentiated form of pancreatic cancer development, including aspects of histology, molecular biology, and tumor biology; moreover, investigator management of adenovirus injection enables its use in chemoprevention studies. The decreases of pancreatic tumor weight, tumor volume and tumor burden in metformin-treated groups show the potential for metformin to be a novel approach for pancreatic cancer prevention and therapy. We also show that metformin treatment inhibits NFκB inflammatory signaling in mouse pancreatic tumors, as evidenced by the inhibition of NFκB phosphorylation and decreased mRNA expression of the downstream genes MCP-1, TGF-β1, TNF-α and IL-1β. Our results, for the first time, indicate that metformin may modulate the inflammation pathway and inhibit pancreatic tumor growth in a genetically engineered pancreatic cancer mouse model; further investigation into elucidating its precise anti-inflammatory mechanisms and its differential effects on prevention vs. treatment for pancreatic cancer is needed.

Although the exact mechanism of action of metformin on pancreatic cancer has not been fully elucidated, the anticancer effects of metformin might be associated with both insulin-independent and insulin-dependent actions of the drug. The insulin-lowering effects of metformin may play a major role in its anticancer activity. Since insulin has mitogenic and pro-survival effects, and tumor cells often express high levels of the insulin receptor, a potential sensitivity to the growth-promoting effects of the hormone is inevitable. Accordingly, prevention of tumor growth in animal models with diet-induced hyperinsulinemia is attributable to reductions of circulating insulin levels,9, 16 suggesting that the insulin-lowering effects of metformin may be a potential mechanism of action in the prevention and treatment of pancreatic cancer. The insulin-independent anti-tumoral actions of metformin originate from liver kinase B1 (LKB1)-mediated activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and subsequent modulation of downstream pathways, such as a reduction in mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTOR) signaling, an inhibition of inflammation and angiogenesis, as well as an induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis.31 While AMPK-dependent suppression of mTOR signaling remains the key candidate mechanism of anti-tumor action of metformin, it is important to note that metformin may also target the inflammatory component present in the microenvironment of most neoplastic tissues, subsequently leading to tumor reduction. The detailed mechanisms by which metformin inhibits mTOR and inflammation have been reviewed recently.49

It is well known that the infiltration of inflammatory cells into a defined site of an organism can precede the development of a neoplasm and that a pre-existing inflammation, often infective, can be involved in the pathogenesis of many human malignancies. Pancreatic carcinoma has a known association with long-standing chronic pancreatitis and the rare condition of hereditary pancreatitis. Inflammatory cells are part of the stromal reaction that characterizes pancreatic cancer, highlighting the close relationship between a chronic inflammation condition and this tumor.50 Moreover, many of the growth promoting factors that are involved in tissue remodeling and regeneration in chronic pancreatitis, are frequently over expressed in pancreatic cancer. Taken together, recent evidence supports that pancreatic inflammation, mediated by cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and unregulated pro-inflammatory pathways, plays an active pro-tumorigenic role in the development and progression of human pancreatic malignancy.

NF-κB and STAT3 are the two most important transcription factors in inflammatory pathways that play major roles in tumorigenesis and thus can be considered targets for cancer prevention and therapy.51, 52 NF-κB, a key mediator of inflammatory response, plays a significant role in carcinogenesis and is now emerging as a link between inflammation and cancer. STAT3 mediates a complex spectrum of cellular response including inflammation, cell proliferation and apoptosis, and has been shown to serve as a mediator of pancreatitis-driven PanIN development. NF-κB and STAT3 are constitutively activated in human pancreatic cancer tumor specimens, as well as in many pancreatic cancer cell lines.53–55 Inhibition of constitutive NFκB activity by a phosphorylation-defective IκBα (S32, 36A) (IκBαM), suppresses pancreatic tumorigenesis in an orthotopic nude mouse model.56 It has been reviewed by Salminen et al.,57 that the activation of AMPK signaling downregulates the function of NFκB signaling via several pathways. AMPK may stimulate silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1), Forkhead Box O (FoxO) family, p53 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α), which can inhibit the NF-κB signaling, and subsequently repress the expression of inflammatory factors with different mechanisms. AMPK may also inhibit the appearance of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and oxidative stresses, which can trigger NFκB signaling. In this study, we showed that metformin treatment activated the AMPK pathway and inhibited NFκB and STAT3 inflammatory signaling in mouse pancreatic tumors, as evidenced by inhibition of phosphorylation of NFκB and STAT3, and the downstream genes MCP-1, TGF-β1, TNF-α and IL-1β. However, metformin treatment did not affect significantly the angiogenesis pathway as indicated by non-significant changes of the mRNA levels of VEGFa, PAI-1 and TSP-1.

Metformin has been shown to modulate inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome58, 59 and inhibit IκB kinase phosphorylation, IκBα degradation and IL-6 production through AMPK activation32, 60, 61. It inhibits IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 and IL-8 from human vascular smooth muscle cells, macrophages and endothelial cells isolated from atheroma plaques by suppressing NFκB.62 Our results that Sp1 expression was decreased in the metformin-treated tumors are comparable with a recent study showing that metformin inhibits pancreatic cancer cells and tumor growth due, in part, to down regulation of Sp transcription factors and Sp-regulated genes.19 However, we did not observe a significant effect of metformin on modulating the VEGFα protein and mRNA levels in the mice. In a murine sponge model, metformin treatment attenuated the main components of the fibrovascular tissue, wet weight, vascularization, macrophage recruitment, collagen deposition and TGF-β1 levels, but no significant change in the levels of VEGF.63 In another preliminary study, four weeks of a 500 mg per day metformin treatment had no effect on plasma VEGF levels in sixteen type 2 diabetes subjects.64 Additionally, Deng et al. showed that metformin reduced p-STAT3 at both the serine and tyrosine phosphorylation sites but not STAT3 expression levels in triple-negative breast cancer cells.55, 65 We showed, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, that metformin may modulate the multiple molecular targets in inflammatory pathway and inhibit pancreatic tumor growth in a genetically engineered pancreatic cancer mouse model.

We did observe a significant decrease of phosphorylation of NFκB and STAT3 only in Met_1wk group, but not in the Met_3wk group. There are many possible reasons why the effects of metformin could have differed from 1-week pretreated to 3-week pretreated group. We speculate that NFκB and STAT3 regulator features are somehow changed and reinstated after a relatively long-term treatment of metformin, but this merits further investigation. We observed significant decreases in MCP-1, TGF-β1, TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expressions in the mice from both the Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups, suggesting that the occurred changes of downstream targeted genes of NFκB and STAT3 could not be recuperated from a long-term treatment of metformin. These data indicated that the beneficial effect of metformin may occur at least in part through inhibiting the NF-κB mediated inflammatory response. Given that treatment with aspirin as a surrogate pharmacologic inhibitor of the NFκB pathway-inhibited pancreatic tumor formation in orthotopic mouse models66, 67 and in p48Cre/+-LSL-KrasG12D/+ mice68; a study design that combines metformin and aspirin in a prevention setting is a possible next step to explore their synergistic effects on pancreatic cancer.

Several potential limitations of the present study should be considered. We cannot conclude that the main effects of metformin on the inhibition of pancreatic tumor growth are preventive in the current study design, since we did not observe the significant differences on the tumor metrics between the Met_1wk and Met_3wk groups. Further experiments with two additional arms (one being pretreated with metformin only before tumor initiation, and the other being treated with metformin only after tumor initiation) are needed to evaluate the differential effects of metformin on prevention vs. treatment for pancreatic cancer. Although the mouse model used in this study captures many significant features as described above; use of other available transgenic models where the tumor progression is slower might be appropriate models to study prevention effects of metformin. Additionally, an epidemiological retrospective study of 302 patients showed that metformin use was significantly associated with longer survival in diabetic patients with pancreatic cancer.17 Further studies are warranted to investigate whether metformin treatment has a survival benefit in mice. Finally, although we observed significant inhibitor effects on pancreatic tumor growth by administration 125 mg/kg metformin only daily, a lower dosage at the physiological achievable level should be considered especially in a future study for prevention efforts.

In summary, our data indicate that metformin, widely used in type 2 diabetes, has substantial potential for pancreatic cancer prevention and treatment. The novel mouse model used in this study is suitable for chemoprevention studies. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the precise anti-inflammatory mechanisms and the differential effects of metformin on prevention vs. treatment for pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P50 CA102701 and R25T CA92049 (G.M. Petersen), R01 CA150190 (D. Mukhopadhyay), and X-L. Tan was supported by R25T CA92049. This research was also partly supported by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (X-L. Tan), and the Histopathology and Imaging Shared Resource(s) of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (P30CA072720).

We thank Ms. Julie S Lau for editing of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- IL-1β

interleukin 1β

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- NFκB

nuclear factor kB

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PanIN

pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β1

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- TSP-1

thrombospondin-1

- VEGFα

vascular endothelial growth factor α

Footnotes

Author disclosures: no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: X.L.T., G.M.P. and D.M. designed research; X.L.T., and K.K.B. conducted research; S.K.D and E.W. performed animal surgery; X.L.T., W.R.B., K.G.R. and A.L.O. planned statistical experimental design and analyzed data; T.C.S stained and reviewed tissue slides; X.L.T., K.K.B, G.M.P. and D.M. wrote the paper; X.L.T., K.K.B and D.M. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1.Bodmer M, Meier C, Krahenbuhl S, et al. Long-term metformin use is associated with decreased risk of breast cancer. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1304–1308. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Yeung SC, Hassan MM, et al. Antidiabetic therapies affect risk of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:482–488. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1617–1622. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, et al. Metformin suppresses colorectal aberrant crypt foci in a short-term clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1077–1083. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodmer M, Becker C, Meier C, et al. Use of antidiabetic agents and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a case-control analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:620–626. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MS, Hsu CC, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Type 2 diabetes increases and metformin reduces total, colorectal, liver and pancreatic cancer incidences in Taiwanese: a representative population prospective cohort study of 800,000 individuals. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosco JL, Antonsen S, Sorensen HT, et al. Metformin and incident breast cancer among diabetic women: a population-based case-control study in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:101–111. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben Sahra I, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF, et al. Metformin in cancer therapy: a new perspective for an old antidiabetic drug? Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1092–1099. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider MB, Matsuzaki H, Haorah J, et al. Prevention of pancreatic cancer induction in hamsters by metformin. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1263–1270. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisfalvi K, Eibl G, Sinnett-Smith J, et al. Metformin disrupts crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptor and insulin receptor signaling systems and inhibits pancreatic cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6539–6545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memmott RM, Mercado JR, Maier CR, et al. Metformin prevents tobacco carcinogen--induced lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1066–1076. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Algire C, Zakikhani M, Blouin MJ, et al. Metformin attenuates the stimulatory effect of a high-energy diet on in vivo LLC1 carcinoma growth. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:833–839. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, et al. Metformin suppresses azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:662–671. doi: 10.1002/mc.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhalla K, Hwang BJ, Dewi RE, et al. Metformin prevents liver tumorigenes is by inhibiting pathways driving hepatic lipogenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:544–552. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rattan R, Ali Fehmi R, Munkarah A. Metformin: an emerging new therapeutic option for targeting cancer stem cells and metastasis. J Oncol. 2012;2012:928127. doi: 10.1155/2012/928127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Algire C, Amrein L, Bazile M, et al. Diet and tumor LKB1 expression interact to determine sensitivity to anti-neoplastic effects of metformin in vivo. Oncogene. 2011;30:1174–1182. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadeghi N, Abbruzzese JL, Yeung SC, et al. Metformin use is associated with better survival of diabetic patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2905–2912. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisfalvi K, Moro A, Sinnett-Smith J, et al. Metformin Inhibits the Growth of Human Pancreatic Cancer Xenografts. Pancreas. 2013 doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31827aec40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair V, Pathi S, Jutooru I, et al. Metformin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth and downregulates Sp transcription factors. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2870–2879. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammed A, Janakiram NB, Brewer M, et al. Antidiabetic Drug Metformin Prevents Progression of Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting in Part Cancer Stem Cells and mTOR Signaling. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:649–659. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren YX, Xu GM, Li ZS, et al. Detection of point mutation in K-ras oncogene at codon 12 in pancreatic diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:881–884. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckel F, Schneider G, Schmid RM. Pancreatic cancer: a review of recent advances. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:1395–1410. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.11.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed A, Janakiram NB, Lightfoot S, et al. Early detection and prevention of pancreatic cancer: use of genetically engineered mouse models and advanced imaging technologies. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3701–3713. doi: 10.2174/092986712801661095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, et al. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin L, Tam A, Pomerantz J, et al. Essential role for oncogenic Ras in tumour maintenance. Nature. 1999;400:468–472. doi: 10.1038/22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kisfalvi K, Eibl G, Sinnett-Smith J, et al. Metformin disrupts crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptor and insulin receptor signaling systems and inhibits pancreatic cancer growth. Cancer research. 2009;69:6539–6545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008;22:659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olivier M, Eeles R, Hollstein M, et al. The IARC TP53 database: new online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:607–614. doi: 10.1002/humu.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:253–270. doi: 10.1042/CS20110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hattori Y, Suzuki K, Hattori S, et al. Metformin inhibits cytokine-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation via AMP-activated protein kinase activation in vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2006;47:1183–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000221429.94591.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, Stark GR. Roles of unphosphorylated STATs in signaling. Cell research. 2008;18:443–451. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdelrahim M, Baker CH, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Tolfenamic acid and pancreatic cancer growth, angiogenesis, and Sp protein degradation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:855–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelrahim M, Baker CH, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 expression by specificity proteins 1, 3, and 4 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3286–3294. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jutooru I, Chadalapaka G, Lei P, et al. Inhibition of NFkappaB and pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth by curcumin is dependent on specificity protein down-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25332–25344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang NY, Woda BA, Banner BF, et al. Sp1, a new biomarker that identifies a subset of aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1648–1652. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang Q, Liu P, Wu X, et al. Berberine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced extracelluar matrix accumulation and inflammation in rat mesangial cells: involvement of NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2011;331:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riad A, Du J, Stiehl S, et al. Low-dose treatment with atorvastatin leads to anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects in diabetes mellitus. European journal of pharmacology. 2007;569:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soetikno V, Sari FR, Veeraveedu PT, et al. Curcumin ameliorates macrophage infiltration by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation and proinflammatory cytokines in streptozotocin induced-diabetic nephropathy. Nutrition & metabolism. 2011;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Ma FY, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-induced tissue inflammation is critical for the development of renal injury but not type 2 diabetes in obese db/db mice. Diabetologia. 2007;50:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mezzano S, Aros C, Droguett A, et al. NF-kappaB activation and overexpression of regulated genes in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2004;19:2505–2512. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun H, Lee M, Kim SS, et al. Glucose deprivation increases mRNA stability of vascular endothelial growth factor through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in DU145 prostate carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9963–9972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neurath KM, Keough MP, Mikkelsen T, et al. AMP-dependent protein kinase alpha 2 isoform promotes hypoxia-induced VEGF expression in human glioblastoma. Glia. 2006;53:733–743. doi: 10.1002/glia.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagata D, Mogi M, Walsh K. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling in endothelial cells is essential for angiogenesis in response to hypoxic stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31000–31006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling stimulates VEGF expression and angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Circ Res. 2005;96:838–846. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163633.10240.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Lawler J. Thrombospondin-based antiangiogenic therapy. Microvasc Res. 2007;74:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMahon GA, Petitclerc E, Stefansson S, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33964–33968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yue W, Yang CS, DiPaola RS, et al. Repurposing of metformin and aspirin by targeting AMPK-mTOR and inflammation for pancreatic cancer prevention and treatment. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:388–397. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erkan M, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW, et al. Tumor microenvironment and progression of pancreatic cancer. Exp Oncol. 2010;32:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aggarwal BB, Sethi G, Ahn KS, et al. Targeting signal-transducer-and-activator-of-transcription-3 for prevention and therapy of cancer: modern target but ancient solution. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1091:151–169. doi: 10.1196/annals.1378.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niu J, Li Z, Peng B, et al. Identification of an autoregulatory feedback pathway involving interleukin-1alpha in induction of constitutive NF-kappaB activation in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16452–16462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scholz A, Heinze S, Detjen KM, et al. Activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) supports the malignant phenotype of human pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:891–905. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toyonaga T, Nakano K, Nagano M, et al. Blockade of constitutively activated Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 pathway inhibits growth of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003;201:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujioka S, Sclabas GM, Schmidt C, et al. Inhibition of constitutive NF-kappa B activity by I kappa B alpha M suppresses tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:1365–1370. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salminen A, Hyttinen JM, Kaarniranta K. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-kappaB signaling and inflammation: impact on healthspan and lifespan. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:667–676. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morin-Papunen L, Rautio K, Ruokonen A, et al. Metformin reduces serum C-reactive protein levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4649–4654. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takemura Y, Osuga Y, Yoshino O, et al. Metformin suppresses interleukin (IL)-1beta-induced IL-8 production, aromatase activation, and proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3213–3218. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang NL, Chiang SH, Hsueh CH, et al. Metformin inhibits TNF-alpha-induced IkappaB kinase phosphorylation, IkappaB-alpha degradation and IL-6 production in endothelial cells through PI3K-dependent AMPK phosphorylation. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim HG, Hien TT, Han EH, et al. Metformin inhibits P-glycoprotein expression via the NF-kappaB pathway and CRE transcriptional activity through AMPK activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1096–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isoda K, Young JL, Zirlik A, et al. Metformin inhibits proinflammatory responses and nuclear factor-kappaB in human vascular wall cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:611–617. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201938.78044.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xavier DO, Amaral LS, Gomes MA, et al. Metformin inhibits inflammatory angiogenesis in a murine sponge model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baba T, Shimada K, Neugebauer S, et al. The oral insulin sensitizer, thiazolidinedione, increases plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:953–954. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deng XS, Wang S, Deng A, et al. Metformin targets Stat3 to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancers. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:367–376. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.18813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sclabas GM, Uwagawa T, Schmidt C, et al. Nuclear factor kappa B activation is a potential target for preventing pancreatic carcinoma by aspirin. Cancer. 2005;103:2485–2490. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Z, Rigas B. NF-kappaB, inflammation and pancreatic carcinogenesis: NF-kappaB as a chemoprevention target (review) Int J Oncol. 2006;29:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rao CV, Mohammed A, Janakiram NB, et al. Inhibition of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia progression to carcinoma by nitric oxide-releasing aspirin in p48(Cre/+)-LSL-Kras(G12D/+) mice. Neoplasia. 2012;14:778–787. doi: 10.1593/neo.121026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.