Abstract

Apicomplexan parasites include some of the most prevalent and deadly human pathogens. Novel antiparasitic drugs are urgently needed. Synthesis and metabolism of isoprenoids may present multiple targets for therapeutic intervention. The apicoplast-localized methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway for isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis is distinct from the mevalonate (MVA) pathway used by the mammalian host, and this pathway is apparently essential in most Apicomplexa. In this review, we discuss the current field of research on production and metabolic fates of isoprenoids in apicomplexan parasites, including the acquisition of host isoprenoid precursors and downstream products. We describe recent work identifying the first MEP pathway regulator in apicomplexan parasites, and introduce several promising areas for ongoing research into this well-validated antiparasitic target.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Plasmodium, isoprenoid, methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, fosmidomycin, metabolism

Introduction

The Apicomplexa are a phylum of protozoan parasites, including some of the most prevalent and deadly human pathogens. Apicomplexa are distinguished from similar protozoa by a “complex” of structures at the apical end of the parasite, including secretory organelles known as the rhoptries and micronemes, and cytoskeletal features such as the conoid [1,2]. Apicomplexa include the Gregarina, Cryptosporidia, Coccidia, and Aconoidasida [3]. Apicomplexan parasites infect a diverse range of multi-cellular hosts, including invertebrates; the gregarines exclusively infect invertebrates. The best-studied Apicomplexa, as described briefly below, cause mammalian diseases of importance to global health and agriculture.

The most divergent Apicomplexa, the Cryptosporidia, include parasites of the Cryptosporidium genus [4]. Infections with Cryptosporidium spp. cause self-limited diarrhea in healthy adults, but cryptosporidiosis can be life-threatening in young children and immunocompromised individuals [5]. Recently, Cryptosporidium spp. were identified as a major agent of severe diarrhea, a leading cause of child death worldwide [6]. The main human cryptosporidial pathogens are C. hominis, which primarily infects humans, and C. parvum, which is common among many mammals. Symptoms are caused by several developmental stages that occur within intestinal epithelial cells (as reviewed in [5]). New treatments for cryptosporidiosis are urgently needed, as the only available therapeutic agent, nitazoxanide, is ineffective in immunocompromised individuals and only moderately effective in immunocompetent individuals [7].

The Coccidia include many parasites that infect both vertebrates and invertebrates. Coccidia of note include Eimeria spp., which infect birds, most prominently chickens and other poultry livestock, and Toxoplasma spp., which infect a very broad range of hosts, including humans [4,8,9]. Toxoplasmosis is generally acquired through ingestion of either tissue cysts (in insufficiently cooked meat), or oocysts (in feces of infected cats, the definitive host species). When acute infection occurs during pregnancy, tachyzoites may infect the fetus, leading to severe birth defects or fetal loss [10]. Toxoplasma gondii readily infects all nucleated mammalian cells, is easily cultured, and its genetic manipulation is straightforward. For these reasons, T. gondii serves as an important model system in studies of apicomplexan biology.

The Aconoidasida, which infect erythrocytes, include the Piroplasmidae and the Hemospororidae [4]. The Piroplasmidae, including Babesia and Theileria spp., primarily cause economically important diseases in livestock. Babesiosis has recently emerged as a threat to blood transfusion recipients [11]. Hemospororidae include Plasmodium spp., which cause malaria in a variety of vertebrates, although each malarial species is typically restricted to a particular host. Five Plasmodium species cause malaria in humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi. Of these, P. vivax is the most common malaria parasite outside of Africa, and P. falciparum, the most deadly malaria parasite, contributes the majority of African cases. Plasmodium spp. are estimated to cause 207 million infections and 627,000 human deaths annually; the majority of these deaths occur in African children under the age of five [12]. Resistance to chloroquine and other quinoline-based treatments has become widespread. Artemisinin became the global drug of choice in the 1990s, but resistance has emerged and is spreading [13–15]. The critical need for new antimalarial agents drives research efforts to identify and target essential aspects of parasite biology, in particular those cellular features that distinguish parasites from host. Plasmodium infections begin when an infected mosquito injects sporozoites into the mammalian host during a blood meal. Following asymptomatic replication in the liver, the symptoms of malaria occur during the asexual replicative stages in human erythrocytes, as successive generations of parasites develop within RBCs, which burst to release additional parasites.

The Apicoplast

In addition to the apical organelles from which the phylum derives its name, most Apicomplexa possess an additional unusual plastid organelle, known as the apicoplast. The apicoplast is of similar secondary endosymbiotic origin to the chloroplast of green plants. Although the apicoplast is not photosynthetic, it nonetheless retains several plant-like metabolic pathways [16].

A key process within the apicoplast is synthesis of the five-carbon isoprenoid precursor molecules, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). All isoprenoids are derived from these two five-carbon molecules and isoprenoid functions are required in all living cells. These molecules fulfill a variety of cellular roles, including participation in key processes such as N-glycosylation, electron transport (ubiquinone), and protein prenylation. With the exception of the Cryptosporidium spp., which are obligate intracellular pathogens and no longer possess an apicoplast, isoprenoid biosynthesis in apicomplexan parasites occurs via a metabolic pathway housed in the apicoplast, known as the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway after its first-dedicated metabolite. Because this organelle is cyanobacterial in origin, the MEP pathway is shared by the majority of eubacteria and other plastid-containing eukaryotes, such as plants and algae [16]. In contrast, most other eukaryotes, including mammals, utilize an independently evolved alternate metabolic route for IPP production, which proceeds through mevalonic acid (MVA).

The MEP pathway

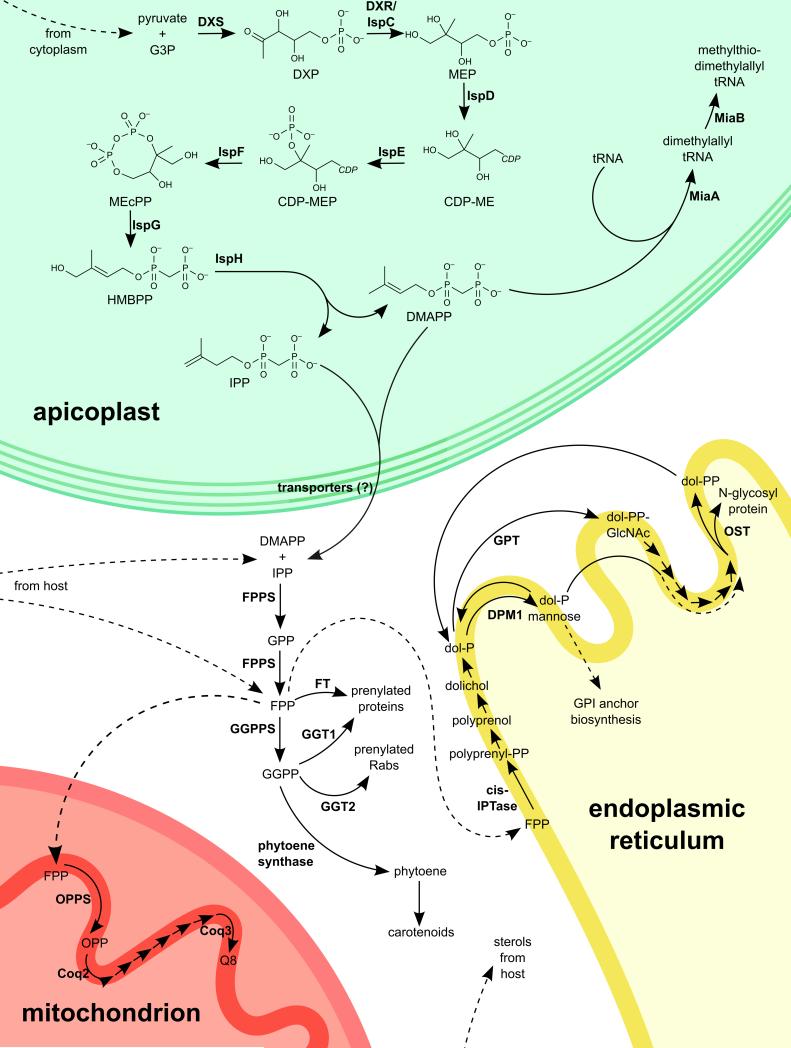

The MEP pathway (see figure) commences with synthesis of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) from two glycolytic intermediates, pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and proceeds through seven enzymatic steps to production of IPP. The initial reaction is catalyzed by deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS). In most organisms, DXS is not considered to be a “committed” member of the MEP pathway because its product, DXP, also participates in thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis and/or pyridoxine (vitamin B6) synthesis. DXP-dependent pyridoxine synthesis is specific to γ-proteobacteria, but DXP is required for de novo thiamine biosynthesis in diverse bacteria. Some downstream synthesis and salvage enzymes are conserved in P. falciparum [17], but not other apicomplexan parasites. It is unclear whether thiamine biosynthesis is required, but thiamine utilization is essential in P. falciparum [18]. The subsequent enzyme of the MEP pathway, IspC/DXR, which is bifunctional, catalyzes the isomerization and the NADPH-dependent reduction of DXP to form 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP). IspD and IspE activate MEP for cyclization by IspF. IspD transfers a cytidyl group to MEP, and the resulting 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (CDP-ME) is phosphorylated by IspE to form 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate (CDP-MEP). IspF cyclizes CDP-MEP, resulting in 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP). The remaining two steps of the pathway are catalyzed by two [4Fe-4S] cluster enzymes, IspG and IspH. IspG opens the MEcPP ring and performs a reduction, resulting in HMBPP (1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-buten-4-yl 4-diphosphate). Finally, IspH reduces HMBPP, producing IPP and DMAPP products [19].

Figure 1. Isoprenoid metabolism in apicomplexan parasites.

Some enzymes and processes are not conserved in all Apicomplexa; see text and Table 1. In Plasmodium and Toxo-plasma spp., FPP and GGPP are synthesized by a single bifunctional enzyme; in Cryptosporidium spp., NPPPS (nonspecific polyprenyl pyrophosphate synthase) synthesizes products with a wide range of chain lengths ([44,57,60]).

Abbreviations: G3P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; DXP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate; MEP, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate; CDPME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol; CDP-MEP, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate; MEcPP, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate; HMBPP, 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-buten-4-yl 4-diphosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; GPP, geranyl pyrophosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; FPPS, farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase; GGPPS, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase; FT, protein farnesyltransferase; GGT1, type I protein geranylgeranyltransferase; GGT2, type II (Rab) protein geranylgeranyltransferase; OPP, octaprenyl pyrophosphate; OPPS, octaprenyl pyro-phosphate synthase; Q8, ubiqinone-8; cis-IPTase, cis-isopentenyltransferase; dol-P, dolichol phosphate; DPM1, dolichol phosphate mannosyltransferase; dol-P mannose, dolichol phosphate mannose; dol-PP-GlcNAc, dolichol pyrophosphate N-acetylglucosamine; OST, oligosaccharyltransferase; dol-PP, dolichol pyrophosphate.

Validation of the MEP pathway

Both genetic and chemical evidence strongly suggest that the MEP pathway is essential in Apicomplexa. In P. falciparum, the IspC/DXR locus is resistant to disruption in erythrocytic-stage parasites [17]. Similarly, in T. gondii, IspC/DXR and LytB/IspH disruptions do not result in viable parasites, and parasites forced to turn off IspH expression do not survive [20]. Since these results agree with similar studies in other MEP pathway containing organisms, including bacteria, genetic studies alone give strong support to the essential nature of the MEP pathway in Apicomplexa [21–25].

In addition, a major pharmacological tool for study of the MEP pathway in apicomplexan parasites has been a well-defined chemical inhibitor of the pathway, fosmidomycin. Fosmidomycin is a phosphonic acid antibiotic that is a substrate mimic and direct inhibitor of the first dedicated MEP pathway enzyme, IspC/DXR [26,27]. Fosmidomycin (and its analog, FR900098) inhibit growth of cultured P. falciparum, Babesia bovis, and B. bigemina, providing some of the first evidence that this pathway was essential in Apicomplexa [28,29]. Subsequent studies have established that the antimicrobial effects of fosmidomycin in malaria parasites are mediated exclusively through inhibition of the MEP pathway [30,31]. Metabolic profiling of fosmidomycin-treated P. falciparum demonstrates decreased cellular levels of downstream MEP pathway metabolites, confirming that fosmidomycin decreases isoprenoid metabolism [31]. In addition, the growth inhibitory effects of fosmidomycin are reduced upon media supplementation with IPP or downstream isoprenols, establishing that there are no significant off-target effects of fosmidomycin treatment. Because IPP-supplemented P. falciparum can survive in the absence of the apicoplast organellar genome and structure, these apicoplast-null strains have been used to suggest that the MEP pathway is the only essential function of the apicoplast [30]. Ongoing studies will be required to confirm whether other nuclear-encoded metabolic pathways, such as heme biosynthesis, might remain functional in these cells, even in the absence of a well-defined apicoplast structure.

In contrast to Plasmodium and Babesia spp., fosmidomycin is ineffective against other apicomplexan parasites, including Theileria parva, Eimeria tenella, T. gondii, and Cryptosporidium spp. [32,33]. Resistance in Cryptosporidium spp. was not unexpected, since these organisms (which lack an apicoplast) do not express MEP pathway enzymes. Fosmidomycin is a highly charged molecule that is excluded from uninfected erythrocytes but accumulates during Plasmodium and Babesia infections, suggesting that active transport through hemosporidian-specific permeability pathways is required for drug uptake [34]. This cellular exclusion appears to be the mechanism by which T. gondii parasites (and likely other Apicomplexa) are naturally fosmidomycin resistant. In an elegant series of experiments, Nair et al demonstrated that expression of a bacterial glycerol-3-phosphate transporter (GlpT), which also allows import of fosfomycin (a drug related to fosmidomycin), confers fosmidomycin sensitivity to cultured T. gondii. Thus, the MEP pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis is essential in T. gondii, and likely required for development of the remaining fosmidomycin-insensitive apicomplexan parasites [20].

Host isoprenoid scavenging

Most apicomplexan parasites spend all or part of their life cycle within a metazoan host cell. This particular environmental niche therefore offers the possibility of scavenging host cell components, including isoprenoid precursors and downstream isoprenoid products. While, in many cases, the extent to which this occurs is not yet fully characterized, evidence so far indicates distinct differences between apicomplexan parasite species and likely between developmental stages of each individual parasite.

Mammalian cells generate isoprenoids through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, although the overall flux is dependent upon cell type. For example, since the liver is a major site of sterol production, hepatocytes have a high capacity for isoprenoid biosynthesis. In contrast, proteomic studies of human erythrocytes suggest that host isoprenoid biosynthesis is absent in these cells [35,36]. MVA-dependent isoprenoid biosynthesis in the host is sensitive to inhibition by the statin class of therapeutics, which potently inhibits the rate-limiting step of this pathway, HMG-CoA reductase [37].

Scavenging in Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium spp. are unique among the parasitic Apicomplexa. As obligate intracellular parasites, these organisms have lost the apicoplast organelle and do not produce the machinery for de novo isoprenoid biosynthesis. Since isoprenoids are required for cellular growth, these parasites are therefore expected to depend entirely on host precursor biosynthesis. Indeed, MVA pathway inhibitors such as itavastatin effectively inhibit C. parvum growth in vitro. Exogenous IPP partially rescues statin-mediated growth inhibition, supporting that the antiparasitic action of these compounds is exerted through their effects on host isoprenoid biosynthesis [38••]. The mechanism by which Cryptosporidium spp. acquire isoprenoid precursors and/or products from the host has not been determined, but C. parvum and C. hominis are predicted to encode enzymes for N-glycoslyation, ubiquinone biosynthesis, and protein prenylation, suggesting that the parasite still modifies downstream isoprenoids [38].

Scavenging in Plasmodium and Babesia

In studies prior to discovery of the MEP pathway, Plasmodium and Babesia spp. were found to be sensitive to treatment with high doses of statins, including simvastatin, lovastatin, and mevastatin [39,40]. Subsequent studies have indicated that the growth inhibitory effects of statins are not mediated through inhibition of isoprenoid biosyn-thesis. While statin-treated mammalian cells are rescued with exogenous mevalonate supplementation, similar rescue of parasites treated with simvastatin, lovastatin [39], or mevastatin [40] was not observed. It seems likely that the intraerythrocytic stages of the Hemospororidae may be unusual in their independence from host isoprenoid bio-synthesis. MVA pathway enzymes are only present in erythrocytes at very low levels, and isoprenoid levels in serum are also very low [35,36,41,42]. Thus, availability of isoprenoid precursors or products seems likely to play only a minor role, at least in the asexual erythrocytic stages. As described below, other apicomplexan parasites, which reside within more metabolically active host cells, may have increased reliance on host isoprenoid synthesis.

In contrast to the metabolically restricted erythrocyte, mammalian hepatocytes produce large quantities of isoprenoid metabolites, including membrane sterols (e.g, cholesterol). Fosmidomycin is also detrimental to growth of liver-stage parasites in cell culture [20], suggesting that even in these relatively isoprenoid-rich cells, de novo synthesis through the MEP pathway is important for parasite development.

Scavenging in Toxoplasma

In contrast to the hemosporidia, T. gondii infect nucleated mammalian cells. In order to assess the reliance of Toxo-plasma spp. on host isoprenoids, Li et al recently generated a farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS)-null strain of T. gondii [43••]. The T. gondii FPPS is a bifunctional enzyme that generates both FPP and GGPP from IPP and DMAPP [44]. Viability of the FPPS knockdown strain varied with host cell type, but extracellular incubation of FPPS mutants depleted intracellular ATP stores and disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential. Although many downstream isoprenoids are likely essential, this FPPS-null phenotype suggests a shortage of ubiquinone to support ATP production through the electron transport chain (ETC). The parasite appears to use both host and endogenous isoprenoids for downstream isoprenoid synthesis, and is able to increase the host contribution when parasite-derived short-chain isoprenoids (< C20, GGPP) are unavailable. Consistent with this suggestion, FPPS-null parasites were more sensitive to inhibition of host isoprenoid biosynthesis by statins. In summary, although the MEP pathway is essential, T. gondii appears to derive short-chain isoprenoids from both endogenous and host synthases [43]. The possibility that a subset of precursors (IPP and DMAPP) may also be host-derived has not yet been excluded.

Scavenging of membrane sterols

While isoprenoid precursors appear to be scavenged by Cryptosporidium and Toxoplasma spp., little is known about which downstream isoprenoids may be scavenged by apicomplexan parasites. One exception is the utilization of host cholesterol. Cholesterol appears to be essential for growth of Apicomplexa, but there is no bioinformatic or biochemical evidence for de novo sterol synthesis in this phylum. Rather, evidence suggests that apicomplexan parasites scavenge cholesterol from various host sources (reviewed in [45]). Typically, cholesterol is transported in the plasma as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Host cells obtain cholesterol by either receptor-mediated endocytosis of LDL or by de novo synthesis via the MVA pathway. Under normal circumstances, HDL delivers cholesterol back to the liver. In Plasmodium spp.-infected erythrocytes, HDL particles can provide cholesterol to the parasite through an unknown mechanism [46]. The malaria parasite also may receive cholesterol from the erythrocyte membrane, possibly via contacts with the parasite vacuolar membrane (PVM) [47]. In the liver, Plasmodium parasites receive cholesterol both from LDL particles and from de novo synthesis by the host [48]. The parasitophorous vacuole (PV) associates both with the host ER [49], which stores cholesterol-enriched lipid bodies, and with cholesterol-enriched late endosomes from the host [50].

T. gondii mainly receives exogenous cholesterol from LDL [51]. As in Plasmodium, cholesterol-filled host lysosomes are closely associated with the PVM [52]. Finally, as parasites that infect intestinal epithelial cells, Cryptosporidium spp. can obtain host cholesterol through LDL uptake, host de novo synthesis, or through absorption of dietary cholesterol from intestinal micelles. Evidence suggests that the parasite relies upon all three of these sources for optimal growth [53].

Fatty acid esterification permits cholesterol storage without excessive perturbation of membrane fluidity. Although Plasmodium spp. do not encode the enzymes necessary for cholesterol storage [54], this process appears to be essential in Toxoplasma [55].

Cellular functions of isoprenoids in Apicomplexa tRNA Isoprenylation

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are required for ribosomal protein synthesis. A common tRNA modification is methylthioisoprenylation, in which tRNAs are modified at adenine 37. These modifications stabilize binding between tRNAs and mRNA/ribosome complex and promote proper codon-anticodon interactions, protecting against premature stops and frame-shift mistakes during translation [56]. tRNA dimethylallyl transferase (MiaA) and MiaB perform the isoprenylation and the thio/methylation reactions, respectively. Although tRNA modification has not been extensively studied in Apicomplexa, most species appear to encode annotated homologs of MiaA and MiaB, suggesting that these processes do occur. In Theileria and Plasmodium spp., MiaA and MiaB are predicted to be apicoplast-localized and are therefore expected to modify apicoplast tRNAs, but the biological implications of this modification have yet to be explored [32,56].

Prenyl synthases

Other than tRNA isoprenylation, the majority of cellular functions require isoprenoids of at least 15 carbons (C15; 3 isoprene units). Elongation of 5-carbon (C5) precursors requires iterative addition of IPP (C5) units to a DMAPP (C5) seed molecule, producing geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP; C10), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP; C15), and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP; C20), in succession. In most organisms, the first two reactions (GPP and FPP synthesis) are catalyzed by a single farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS), while a second enzyme, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) adds an additional IPP unit. However, in Plasmodium and Toxoplasma spp., a single bifunctional FPPS/GGPPS performs each of these reactions [44,57,58]. Further elongation may be performed by downstream prenyl synthases, such as the P. falciparum octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (OPPS), which has been characterized in vitro [59]. In C. parvum, a unique nonspecific polyprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (NPPPS) produces a remarkable range of products, from C15 to greater than C40 [60]. These 10-, 15-, and 20-carbon pyrophosphate products are necessary for synthesis of essential downstream isoprenoids, such as ubiquinone. For this reason, Apicomplexan prenyl synthases are expected to be essential, unless these compounds can be scavenged from the host.

Protein prenylation

Proteins may be modified post-translationally by isoprenylation. Such protein prenylation provides a membrane anchor, typically essential for proper localization and/or function of the modified protein substrate. Prenyltransferases recognize specific motifs at the C-termini of proteins, so-called CaaX motifs (cysteine, followed by two aliphatic residues, followed by any residue). Type I protein farnesyltransferases (FT) and protein geranylgeranyltransferases (GGT1) recognize this CaaX motif, and the identity of the fourth residue can determine whether the protein is farnesylated or geranylgeranylated. Rab proteins, which help regulate vesicular trafficking, additionally require an escort protein for CaaX recognition by Type II geranylgeranyltransferases (GGT2; Rab GGT (reviewed in [61]).

Malaria parasites are capable of protein prenylation, and prenyltransferase inhibitors inhibit parasite growth [62–67]. Protein prenylation is likely to be one of the essential functions of isoprenoids in malaria parasites, since inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis mislocalizes a putative prenyltransferase substrate (Rab5) and results in trafficking defects consistent with loss of Rab5 function [68]. Other prenylated Plasmodium proteins include a tyrosine phosphatase, PfPRL, and the Ykt6 SNARE protein [69,70]. Addition of C55 dolichyl and C60 isoprenyl chains to P. falciparum proteins has also been observed, but the biological functions of these modifications have not been explored [71].

Protein prenylation has been observed in T. gondii. This activity is inhibited by certain synthetic heptapeptides [72]. The presence of protein prenyltransferases has been predicted bioinformatically in Cryptosporidia, but not yet experimentally confirmed [61].

Quinones

The most prominent cellular function of molecules such as ubiquinone and menaquinone is as intermediates in the electron transport chain (ETC), allowing generation of the mitochondrial proton gradient. This gradient provides an energy source for ATP generation and active transport. During ubiquinone biosynthesis, polyisoprenylation of the redox-active benzoquinone group, which allows mitochondrial membrane localization, is catalyzed by 4-hydroxybenzoate polyprenyltransferase (Coq2). This step is followed by several additional modifications to the benzoquinone moiety, including methylation by Coq3 (reviewed in [73]). Both Coq2 and Coq3 functions appear to be conserved among apicomplexan parasites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Presence of isoprenoid metabolic genes in the genomes of apicomplexan parasites. Available genome data was searched for homologs to known enzymes using default settings on NCBI BLAST; EuPath DB annotations were also consulted. Bold entries represent enzymes whose activities have been experimentally verified. Accurate assignment of enzyme homologs in Eimeria tenella was limited by the quality of currently available genome data. Entries represent the most likely identified candidates. PfHad1 paralogs were identified based on sequence homology to PF3D7_1033400 (NCBI BLAST) and membership in the IIb subfamily of HAD-superfamily hydrolases (Interpro IPR006379). X denotes no homolog found

| Enzyme | EC number | P. falciparum 3D7 | T. gondii GT-1 | Eimeria tenella | Babesia microti RI | Theileria parva Mugaga | C. parvum Iowa II | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEP pathway enzymes | DXS | 2.2.1.7 | PF3D71337200 | TGGT1_208820 | ETH_00003770 | BBM_III00540 | TP01_0516 | X |

| DXR | 1.1.1.267 |

PF3D7_1467300 [112] |

TGGT1_214850 [113] |

ETH_00017440 | BBM_II02665 | TP02_0073 | X | |

| IspD | 2.7.7.60 | PF3D7_0106900 | TGGT1_306260 | * | BBM_I02480 | TP01_0057 | X | |

| IspE | 2.7.1.148 | PF3D7_0503100 | TGGT1_306550 | * | BBM_III01890 | TP02_0581 | X | |

| IspF | 4.6.1.12 |

PF3D7_0209300 [114] |

TGGT1_255690 | ETH_00030180 | BBM_III05000 | TP03_0365 | X | |

| IspG | 1.17.7.1 | PF3D7_1022800 | TGGT1_262430 | ETH_00001880 | BBM_III01825 | TP01_0667 | X | |

| IspH | 1.17.1.2 | PF3D7_0104400 | TGGT1_227420 | ETH_00020795 | BBM_III05255 | TP03_0674 | X | |

| Prenyl synthases | FPPS | 2.5.1.10 |

PF3D7_1128400 [57]a |

TGGT1_224490 [44]b |

ETH_00019475 | BBM_I00130 | TP03_0857 |

cgd4_2550 [60]c |

| OPPS | 2.5.1.90 |

PF3D7_0202700 [59]d |

TGGT1_269430 | ETH_00035470 | BBM_I01090 | TP03_0238 | cgd7_3730 | |

| Cis- IPTase |

2.5.1.87 | PF3D7_0826400 | TGGT1_316770 | ETH_00037555 | BBM_I01680 | TP03_0421 | cgd4_1510 | |

| Ubiquinone synthesis |

Coq2 | 2.5.1.39 | PF3D7_0607500 | TGGT1_259130 | * | BBM_III09587 | TP03_0802 | * |

| Coq3 | 2.1.1.64 | PF3D7_0724300 | TGGT1_266850 | ETH_00031320 | BBM_III02105 | TP02_0197 | cgd2_2830 | |

| tRNA | MiaA | 2.5.1.75 | PF3D7_1207600 | TGGT1_312520 | ETH_00042745 | BBM_II01495 | TP01_0445 | Cgd6_2540 |

| N- glycosylation | GPT | 2.7.8.15 | PF3D7_0321200 | TGGT1_244520 | ETH_00020690 | BBM_II00105 | TP01_0118 e |

cgd5_2240 |

| OST, Stt3p subunit |

2.4.99.18 | PF3D7_1116600 | TGGT1_231430 | ETH_00007235 | Homolog found only in other Babesia spp. |

X | cgd6_2040 | |

| DPMI | 2.4.1.83 | PF3D7_1141600 | TGGT1_277970 | * (cite Theil) | BBM_I00170 | TP02_0741 | cgd5_2040 | |

| Protein prenylation |

FT, GGT1, GGT2 |

2.5.1.58 2.5.1.59 2.5.1.60 |

Although phylogenetic searches identified multiple proteins with homology to protein prenyltransferases in each species examined, it was not possible to distinguish between types of prenyltransferases (e.g., GGT-I vs. FT-1) based on homology alone. However, evidence of protein prenylation has been demonstrated in several apicomplexans. |

|||||

| PfHADI paralogs | PfHAD1 |

PF3D7_1033400 (PfHAD1) [109], PF3D7_1226300, PF3D7_1226100, PF3D7_1017400, PF3D7_1118400 |

TGGT1_243910, TGGT1_239710, TGGT1_229320, TGGT1_297720, TGGT1_229330 |

ETH_00014830, ETH_00010345, ETH_00027645 |

BBM_III03770, BBM_III01380 |

TP02_0864, TP01_1081, TP01_1077, TP01_1076, TP01_1075, TP01_1074, TP01_0861, TP01_0785 |

cgd4_960, cgd1_3340 |

|

denotes no definite homolog found but activity is expected. Proteins in bold have been characterized in vitro.

Abbreviations: FPPS, farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase; OPPS, octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase; cis-IPTase, cis-isoprenyltransferase; GPT, dolichol phosphate N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase; OST, oligosaccharyltransferase; DPM1, dolichol phosphate mannosyltransferase; FT, protein farnesyltransferase; GGT1, type I protein farnesyltransferase; GGT2, type II (Rab) protein farnesyltransferase.

PF3D7_1128400 is a bifunctional FPP/GGPP synthase.

The bifunctional T. gondii protein, TGGT1_224490 (E.C. 2.5.1.29), carries FPP/GGPP synthase activity but is more homologous to GGPPS proteins

cgd4_2550 demonstrates nonspecific polyprenyl pyrophosphate synthase activity.

PF3D7_0202700 also has phytoene synthase activity [95].

Theileria spp. were not expected to encode GPT activity [91].

Within the mitochondrial ETC, multiple dehydrogenases play important roles in reducing ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) to generate ubiquinol, which then passes electrons to complex III, the cytochrome bc1 complex. In mammals, the most prominent ubiquinone reductases are complex I (type I NADH dehydrogenase; NDH1) or complex II (succinate dehydrogenase; SDH). In various Apicomplexa, ubiquinone can accept electrons from several dehydrogenases, including glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, malate-quinone oxidoreductase, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), SDH, and type II NADH dehydrogenase (NDH2). Apicomplexa have not retained NDH1. After electron transfer from ubiquinol to complex III, electrons are transferred to cytochrome c, and finally to complex IV. Protons are pumped across the membrane throughout this process (reviewed in [74]).

Ubiquinone biosynthesis and function have been best studied in P. falciparum, in which parasites modulate ubiqui-none:menaquinone ratios according to oxygen levels. Menaquinone can substitute for ubiquinone in the ETC, but how these ratios are modulated is unknown [75]. Biosynthesis of the isoprenyl sidechain of ubiquinone in P. falciparum, which contains 8 or 9 isoprenyl units, was first described in 2002 [76]. In cultured erythrocytic P. falciparum, expression of yeast dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), which does not require ubiquinol as an electron acceptor, reduces sensitivity to inhibition by the Complex III inhibitor, atovaquone. Thus, the essential function of the Plasmodium ubiquinone, at least in the asexual stages, is to allow pyrimidine synthesis by acting as an electron sink for the essential pyrimidine biosynthesis enzyme DHODH [77]. Since expression of yeast DHODH does not confer resistance to fosmidomycin, it is clear that in intraerythrocytic parasites, pyrimidine biosynthesis is not the only essential process in malaria parasites that requires isoprenoid synthesis [68].

In contrast, mosquito-stage Plasmodium parasites appear to depend upon oxidative phosphorylation and ubiquinone for ATP generation. P. berghei parasites lacking functional succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) or NDH2 fail to form functional oocysts in mosquitoes, although they are still capable of asexual replication [78,79].

Like Plasmodium, T. gondii does not rely heavily on the ETC for ATP generation, but is nonetheless sensitive to disruption of the ETC by atovaquone, which inhibits complex III. DHODH is also essential in T. gondii [80]. Single disruptions of either of two ubiquinone-reducing NDH2 isoforms are possible, but confer growth defects; a double knockout was unable to be generated [81].

Cryptosporidium spp. are distinguished from other apicomplexan parasites by the presence of a mitochondrion-like organelle, the mitosome. Based on in silico analysis, the mitosome of the rodent intestinal parasite, C. murum, harbors a complete TCA cycle, simplified ETC, and intact ATP synthase, in contrast to C. hominis and C. parvum. In the human pathogens, the only TCA enzyme is a truncated malate:quinone oxidoreductase (MQO) homolog (reviewed in [82]). This simplified Cryptosporidium ETC lacks complexes III and IV; rather, an alternative oxidase (AOX) allows electron transfer between ubiquinol (probably generated via MQO) and O2 [82]. Recombinantly produced C. parvum AOX was verified to have ubiquinol oxidase activity. This enzyme is both sensitive to ascofuranone, an inhibitor of Trypanosoma brucei AOX, and to salicylhydroxamic acid (SHAM), a known AOX inhibitor [83]. Treatment with SHAM and 8-hydroxquinolone, another known AOX inhibitor, inhibit growth of C. parvum, T. gondii, and P. falciparum in culture, although homology-based identification of specific AOX candidates from T. gondii or P. falciparum has not been successful [84]. Since ubiquinol oxidase activity appears to be essential, ubiquinone synthesis or salvage is likely essential as well.

Dolichols

Dolichols are long isoprene chains with saturated isoprenic units at the alpha position. Chain lengths vary by species. These molecules are required both for N-glycosylation of proteins and for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor biosynthesis. During N-glycosylation, dolichol serves as a membrane anchor for the growing glycan chain, which is eventually transferred from the dolichol to the target protein. Mannose residues are added during the latter phases of glycan chain elongation; dolichol phosphate mannose serves as the donor for these reactions. Dolichol phosphate mannose is also required as a donor during GPI anchor synthesis (reviewed in [85]).

Both protein N-glycosylation and GPI anchor biosynthesis appear to be active processes in Apicomplexa. GPIs play important roles in the biology of Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Cryptosporidium spp. (reviewed in [86,87]). Although T. gondii performs N-glycosylation [88], it was unclear for some time whether these modifications were absent, or simply rare, in Plasmodium spp. It now appears that Plasmodium spp. produce a small number of N-glycosylated proteins [89], with unusually short N-glycan chains. In fact, many apicomplexan genomes encode “incomplete” protein N-glycosylation pathways, which result in truncated N-glycans [90]. For example, Theileria is reported to lack N-glycosylation machinery altogether [91]. Tunicamycin, which inhibits transfer of the first GlcNAc residue onto the dolichol anchor, during N-glycan synthesis, is toxic to both P. falciparum and T. gondii, suggesting that this process is required for parasite survival [92,93].

Other isoprenoids

Carotenoids are tetraterpene (8 isoprene units) pigments, often with antioxidant activity. Typically, two GGPP molecules are combined to form phytoene, from which subsequent carotenoids are derived [94]. Several carotenoids, including all-trans-β-carotene and all-trans-lutein, have been identified in cultured P. falciparum, but not uninfected control cultures [95]. No clear homologues of known carotenoid biosynthesis enzymes are apparent in Plasmodium or Toxoplasma genomes, but a previously identified octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (OPPS) showed synthesis of phytoene and some downstream carotenoids in vitro. Inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis sensitized P. falciparum parasites to high environmental oxygen concentrations, suggesting that carotenoids may function as antioxidants in malaria parasites [95].

In plants, abscisic acid, another carotenoid, acts as a signaling molecule. Signal transduction involves stimulation of intracellular calcium release [96]. In T. gondii, exogenous abscisic acid also triggers release of intracellular calcium stores. While the biosynthetic enzymes to produce abscisic acid are not readily identified bioinformatically, abscisic acid was detected in parasite lysates and reduced after treatment with fluridone, a carotenoid biosynthesis inhibitor. Fluridone treatment also prevented parasite egress, suggesting that abscisic acid signaling plays a crucial role in this process [97].

Vitamin E (α- and γ-tocopherol) was recently identified in P. falciparum extracts. Growth inhibition by usnic acid, which inhibits vitamin E synthesis, was accompanied by a decline in vitamin E concentrations, but only partially rescued by addition of alpha-tocopherol. Alpha tocopherol synthesis increased by 40% under high (20%) oxygen, suggesting a role for vitamin E in protection from oxidative stress [98].

Regulation of the MEP pathway

Since the MEP pathway is considered to be a promising target for anti-parasitic drug development, regulation of the pathway is of great interest to the field. However, very little is known about pathway regulation in Apicomplexa. As in other metabolic pathways, regulation of the MEP pathway is typically at the level of so-called rate-limiting enzymes. In many plants and bacterial species, DXS has been identified as a rate-limiting enzyme of the MEP pathway. In addition, DXR and IspF have also been identified as rate-limiting in some cases (reviewed in [99]).

Several studies have identified transcript-level regulation of MEP pathway genes in plants (reviewed in [99]). Furthermore, Sauret-Güeto et al found that fosmidomycin resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana is due to impaired translation of plastome mRNAs. This resistance mechanism results in increased levels of IspC/DXR protein, which is encoded in the nucleus; DXS, IspG, and IspH protein levels also increase. The precise regulatory mechanism by which MEP enzyme expression responds to plastome expression has not been identified, but it is possible that similar post-trancriptional regulation may occur in Apicomplexa [100].

Post-translational regulation of MEP pathway enzymes has also been described in several organisms, and may also be present in apicomplexan parasites. For example, in Francisella tularensis, phosphorylation of either IspC/DXR or IspD at conserved sites down-regulates enzyme activity. F. tularensis IspC/DXR is phosphorylated at Ser177; phosphorylation of F. tularensis IspD occurs at Thr141 [101,102]. The IspC/DXR Ser177 residue appears to be conserved in most Apicomplexa; the IspD Thr141 position is generally either a threonine or a serine, either of which could be phosphorylated.

For many MEP enzymes, metabolite binding also appears to regulate enzymatic function, at least in vitro. First, the Populus trichocarpa (black cottonwood tree) DXS enzyme is inhibited by high concentrations of IPP, suggesting feedback inhibition may occur [103•]. Second, the enzyme IspF may be a target for feed-forward regulation; the upstream metabolite MEP stabilizes activity of purified recombinant E. coli IspF, and this stabilization is inhibited by co-incubation with the downstream metabolite FPP [104•]. Finally, IspF monomers form a very stable trimer, which is assumed to be required for activity. A hydrophobic cavity at this trimer interface is conserved in most organisms, including P. falciparum [105] (A P. vivax IspF structure has been deposited but not published; PDB: 3B6N). Multiple structural studies have identified IPP, GPP, or FPP bound at this interface, suggesting a potential role in feedback regulation [106–108].

To date, a single regulator has been described for the MEP pathway in Apicomplexa. P. falciparum HAD1 (PfHAD1) is a sugar phosphatase and a member of the haloacid dehalogenase superfamily. PfHAD1 cleaves phosphate groups from a variety of substrates, including MEP pathway intermediates and glycolytic intermediates upstream of the MEP pathway. Loss-of-function mutations in PfHAD1 confer partial resistance to fosmidomycin, likely as a result of increased substrate availability [109••]. HAD1 homologs in other apicomplexan parasites may also be negative regulators of MEP pathway activity (Table 1).

Conclusion

Apicomplexan parasites include several human pathogens of global importance. Current treatments for these diseases are inadequate and novel drugs are urgently needed, particularly for treatment of cryptosporidial diarrhea and malaria. Isoprenoids appear to be essential in all organisms, and apicomplexan parasites acquire isoprenoids via scavenging or the apicoplast-localized MEP pathway. Therefore it is important to understand the fundamental biology and regulation of isoprenoid biosynthesis in apicomplexan parasites, en route to discovery of novel therapeutic agents with parasite-specific mechanisms-of-action.

Several aspects of apicomplexan isoprenoid metabolism have yet to be fully elucidated. To begin, most isoprenoid precursors and early isoprenoid products are highly charged and likely to require active transport across membranes. For example, plastidic phosphate translocators (pPT family) on the apicoplast membranes import glycolytic intermediates from which the MEP precursors, pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, are generated [110,111]. However, IPP and DMAPP products must ultimately exit the apicoplast, since downstream metabolism occurs outside this organelle. The molecular identity of these isoprenyl pyrophosphate transporters is yet unknown, but these proteins are expected to be required for parasite viability. In addition, while current evidence strongly suggests that many apicomplexan parasites scavenge isoprenoid precursors and components from host cells, the molecular mechanisms and transporters that support this scavenging are unclear. In particular, simple host isoprenoids (e.g., IPP, FPP, and GGPP) are necessary for development of C. parvum, and T. gondii [38,43], but whether these molecules are accessed directly through transport or through endocytosis of host cytoplasm is unknown. While some crucial steps of cholesterol scavenging have been identified in Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium spp., the process is not yet fully understood, especially in Plasmodium spp. It is possible that further complex or longer-chain isoprenoid products may also be obtained from the host. The mechanisms of host scavenging are not likely to have close human or mammalian homologs. Therefore a deeper understanding of this process is a promising avenue for identification of additional drug targets and for use of well-characterized inhibitors of host isoprenoid biosynthesis (e.g., statins) as adjunctive therapeutic agents for apicomplexan diseases.

Improving our understanding of MEP pathway regulation is also likely to identify new therapeutic targets. For example, the recent discovery of the first regulator of apicomplexan MEP metabolism, PfHAD1, has raised several questions about the normal function of HAD1 and its homologs [109]. PfHAD1 activity exerts a strong effect on MEP pathway function. Potential mechanisms for regulation of PfHAD1 activity, or stimuli to which PfHAD1 may respond, have yet to be identified. PfHAD1 has very close homologs in all other apicomplexan parasites, and, in fact, P. falciparum itself encodes 4 additional HAD paralogs (Table 1). The close sequence conservation within this enzyme family strongly suggests that HAD proteins have important biological functions under normal physiological conditions. For example, given its diverse substrate profile, PfHad1 may regulate additional metabolic pathways in the cell, in addition to the MEP pathway. Future studies are required to elucidate the functional significance of HAD homologs in other apicomplexan parasites.

Since the MEP pathway is energetically expensive, requiring both nucleotides and reducing power, HAD homologs are not likely to be the only mechanism by which parasite cells regulate MEP pathway flux. This is particularly likely in organisms other than blood-stage P. falciparum, in which the host cell does not produce IPP. Because most other apicomplexan parasites depend upon both host and de novo isoprenoid metabolism, these species are likely to adjust their own biosynthesis of isoprenoid precursors in response to available host supplies. The isoprenoid pyro-phosphate-binding cavity at the core of the IspF trimer, which is conserved in Plasmodium spp. and is likely present in additional apicomplexan parasites, suggests one possible mechanism for such feedback regulation [105].

Finally, it is likely that future studies will result in the identification of additional isoprenoid-utilizing enzymes and their products in apicomplexan parasites. Bioinformatic strategies have not conclusively identified the enzymes responsible for synthesis of many known isoprenoid metabolites, such as abscisic acid [97]. This likely reflects both the diversity of isoprenoid products and the evolutionary distance between apicomplexan parasites and other MEP-pathway-utilizing organisms. Furthermore, given the apparent substrate flexibility of many of the enzymes involved in isoprenoid metabolism, it is clear that phylogenetic prediction alone will be insufficient to elucidate the reactions catalyzed by specific proteins. For example, the P. falciparum octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (OPPS), which elongates an FPP precursor to a C40 or C45 chain by repeated addition of IPP units, also unexpectedly catalyzes synthesis of phytoene (C40) from two GGPP precursors. Furthermore, the enzyme appears to derivatize phytoene into several additional carotenoid products [95]. Altogether, the evolutionary distance and the ongoing challenges of functional annotations in apicomplexan parasites will ultimately require directed study of particular enzymes and their functions as they are discovered.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ann Guggisberg and Antony John for critical reading of this manuscript.

Dr. Odom is supported by the Children's Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital (MD-LI-2011-171), NIH/NIAID R01AI103280, a March of Dimes Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar Research Award), and a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development award. LI is supported by an NIH/NIGMS Training grant (T32-AI007172).

Biography

Audrey R. Odom, MD PhD received her undergraduate, graduate, and medical degrees from Duke University, before completing clinical training in pediatrics and infectious diseases at the University of Washington. During her fellowship, Dr. Odom began studies of isoprenoid metabolism in malaria parasites under the supervision of Dr. Wesley Van Voorhis. Dr. Odom is currently Assistant professor of Pediatrics and Molecular Microbiology at Washington University School of Medicine. Research in the Odom lab focuses on the regulation and biological functions of isoprenoid metabolism in bacteria and protozoan parasites.

Leah Imlay received a B.A. in Biology from Grinnell College in 2010. She is currently a graduate student in Molecular Microbiology and Microbial Pathogenesis at Washington University. In the Odom lab, Leah studies protein-protein interactions during microbial isoprenoid biosynthesis

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

Leah Imlay declares that they have no conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Leah Imlay, Department of Molecular Microbiology Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis, MO 63110 USA limlay@wustl.edu.

Audrey R. Odom, Department of Pediatrics Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis, MO 63110 USA & Department of Molecular Microbiology Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis, MO 63110 USA.

References

•Of importance

••Of outstanding importance

- 1.Gubbels M-J, Duraisingh MT. Evolution of apicomplexan secretory organelles. Int J Parasitol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.09.009. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrissette NS, Sibley LD. Cytoskeleton of apicomplexan parasites. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002 doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.21-38.2002. doi:10.1128/MMBR.66.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adl SM, Simpson AGB, Farmer M a, et al. The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2005 doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachvaroff TR, Handy SM, Place AR, et al. Alveolate phylogeny inferred using concatenated ribosomal proteins. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2011.00555.x. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2011.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossle NF, Latif B. Cryptosporidiosis as threatening health problem: A review. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013 doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60179-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abubakar II, Aliyu SH, Arumugam C, et al. Prevention and treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients (Review ). Cochrane Collab. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2. doi:0.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman HD, Barta JR, Blake D, et al. A selective review of advances in coccidiosis research. Adv Parasitol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407705-8.00002-1. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407705-8.00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K, Weiss LM. Toxoplasma: the next 100 years. Microbes Infect. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oz HS. Maternal and congenital toxoplasmosis, currently available and novel therapies in horizon. Front Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00385. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oz HS, Westlund KH. “Human babesiosis”: an emerging transfusion dilemma. Int J Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/431761. doi:10.1155/2012/431761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Malaria Report: 2013. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, et al. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dooren GG, Striepen B. The algal past and parasite present of the apicoplast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155741. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozdech Z, Ginsburg H. Data mining of the transcriptome of Plasmodium falciparum: the pentose phosphate pathway and ancillary processes. Malar J. 2005 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-17. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan XWA, Wrenger C, Stahl K, et al. Chemical and genetic validation of thiamine utilization as an antimalarial drug target. Nat Commun. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3060. doi:10.1038/ncomms3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter WN. The non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700005200. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair SC, Brooks CF, Goodman CD, et al. Apicoplast isoprenoid precursor synthesis and the molecular basis of fosmidomycin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 2011 doi: 10.1084/jem.20110039. doi:10.1084/jem.20110039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuzuyama T, Takahashi S, Seto H. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli disruptants defective in the yaeM gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999 doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.776. doi:10.1271/bbb.63.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAteer S, Coulson A, McLennan N, et al. The lytB gene of Escherichia coli is essential and specifies a product needed for isoprenoid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2001 doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7403-7407.2001. doi:10.1128/JB.183.24.7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herring CD, Blattner FR. Conditional lethal amber mutations in essential Escherichia coli genes. J Bacteriol. 2004 doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2673-2681.2004. doi:10.1128/JB.186.9.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown AC, Parish T. Dxr is essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fosmidomycin resistance is due to a lack of uptake. BMC Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-78. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown AC, Eberl M, Crick DC, et al. The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential and transcriptionally regulated by Dxs. J Bacteriol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JB.01402-09. doi:10.1128/JB.01402-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzuyama T, Shimizu T, Takahashi S, et al. Fosmidomycin, a specific inhibitor of 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase in the nonmevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis. Tetrahedon Lett. 1998 doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9879. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01755-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeidler J, Schwender J, Müller C, et al. Inhibition of the non-Mevalonate 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of plant isoprenoid biosynthesis by fosmidomycin. Zeitschrift Für Naturforsch. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jomaa H. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science (80) 1999 doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. doi:10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivakumar T, Abulaila MRA, Khukhuu A, et al. In vitro inhibitor effect of fosmidomycin on the asexual growth of Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina. J Protozool Res. 2008;18:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeh E, DeRisi JL. Chemical rescue of malaria parasites lacking an apicoplast defines organelle function in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001138. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Watts KM, Hodge D, et al. A second target of the antimalarial and antibacterial agent fosmidomycin revealed by metabolic profiling. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi200113y. doi:10.1021/bi200113y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lizundia R, Werling D, Langsley G, et al. Theileria apicoplast as a target for chemotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00126-08. doi:10.1128/AAC.00126-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clastre M, Goubard A, Prel A, et al. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in coccidia: presence and sensitivity to fosmidomycin. Exp Parasitol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumeister S, Wiesner J, Reichenberg A, et al. Fosmidomycin uptake into Plasmodium and Babesia-infected erythrocytes is facilitated by parasite-induced new permeability pathways. PLoS One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019334. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kakhniashvili DG, Bulla L a, Goodman SR. The human erythrocyte proteome: analysis by ion trap mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300132-MCP200. doi:10.1074/mcp.M300132-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman SR, Kurdia A, Ammann L, et al. The human red blood cell proteome and interactome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007 doi: 10.3181/0706-MR-156. doi:10.3181/0706-MR-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endo A, Kuroda M, Tanzawa K. Competitive inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase by ML-236A and ML-236B fungal metabolites, having hypocholesterolemic activity. FEBS Lett. 1976 doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80996-9. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(76)80996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38••.Bessoff K, Sateriale A, Lee KK, et al. Drug repurposing screen reveals FDA-approved inhibitors of human HMG-CoA reductase and isoprenoid synthesis that block Cryptosporidium parvum growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02460-12. doi:10.1128/AAC.02460-12. [This study identified several HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors as inhibitors of C. parvum growth, suggesting that scavenging of host isoprenoids is essential. Growth inhibition by itavastatin could be moderately rescued with IPP.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grellier P, Valentin A, Millerioux V, et al. 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase Inhibitors Lovastatin and Simvastatin Inhibit In Vitro Development of Plasmodium falciparum and Babesia divergens in Human Erythrocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994 doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1144. doi:10.1128/AAC.38.5.1144.Updated. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couto a S, Kimura E a, Peres VJ, et al. Active isoprenoid pathway in the intra-erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum: presence of dolichols of 11 and 12 isoprene units. Biochem J. 1999;341:629–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saisho Y, Morimoto a, Umeda T. Determination of farnesyl pyrophosphate in dog and human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Anal Biochem. 1997 doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2314. doi:10.1006/abio.1997.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Psychogios N, Hau DD, Peng J, et al. The Human Serum Metabolome. PLoS One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016957. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Li Z-H, Ramakrishnan S, Striepen B, et al. Toxoplasma gondii relies on both host and parasite isoprenoids and can be rendered sensitive to atorvastatin. PLoS Pathog. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003665. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003665. [This study showed that T. gondii both scavenges isoprenoids from host cells and synthesizes FPP and GGPP using a bifunctional enzyme. Depending on the host cell environment, FPPS/GGPPS may be essential; otherwise, FPPS/GGPPS-deficient parasites are sensitive to atorvastatin.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling Y, Li Z-H, Miranda K, et al. The farnesyl-diphosphate/geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase of Toxo-plasma gondii is a bifunctional enzyme and a molecular target of bisphosphonates. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703178200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M703178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coppens I. Targeting lipid biosynthesis and salvage in apicomplexan parasites for improved chemotherapies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3139. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grellier P, Rigomier D, Clavey V, et al. Lipid traffic between high density lipoproteins and Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells. J Cell Biol. 1991 doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.2.267. doi:10.1111/mmi.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lauer S, VanWye J, Harrison T, et al. Vacuolar uptake of host components, and a role for cholesterol and sphingomyelin in malarial infection. EMBO J. 2000 doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3556. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.14.3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Labaied M, Jayabalasingham B, Bano N, et al. Plasmodium salvages cholesterol internalized by LDL and synthesized de novo in the liver. Cell Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01555.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bano N, Romano JD, Jayabalasingham B, et al. Cellular interactions of Plasmodium liver stage with its host mammalian cell. Int J Parasitol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopes da Silva M, Thieleke-Matos C, Cabrita-Santos L, et al. The host endocytic pathway is essential for Plasmodium berghei late liver stage development. Traffic. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01398.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coppens I, Sinai a P, Joiner K a. Toxoplasma gondii exploits host low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis for cholesterol acquisition. J Cell Biol. 2000 doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.167. doi:10.1083/jcb.149.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coppens I, Dunn JD, Romano JD, et al. Toxoplasma gondii sequesters lysosomes from mammalian hosts in the vacuolar space. Cell. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.056. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ehrenman K, Wanyiri JW, Bhat N, et al. Cryptosporidium parvum scavenges LDL-derived cholesterol and micellar cholesterol internalized into enterocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cmi.12107. doi:10.1111/cmi.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coppens I, Vielemeyer O. Insights into unique physiological features of neutral lipids in Apicomplexa: from storage to potential mediation in parasite metabolic activities. Int J Parasitol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.009. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lige B, Sampels V, Coppens I. Characterization of a second sterol-esterifying enzyme in Toxoplasma highlights the importance of cholesterol storage pathways for the parasite. Mol Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/mmi.12142. doi:10.1111/mmi.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ralph SA, Dooren GG Van, Waller RF, et al. Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro843. doi:10.1038/nrmicro843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jordão FM, Gabriel HB, Alves JM, et al. Cloning and characterization of bifunctional enzyme farnesyl diphosphate/geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase from Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-184. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Artz JD, Wernimont AK, Dunford JE, et al. Molecular characterization of a novel geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase from Plasmodium parasites. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027235. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.027235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tonhosolo R, D'Alexandri FL, Genta F a, et al. Identification, molecular cloning and functional characterization of an octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase in intra-erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem J. 2005 doi: 10.1042/BJ20050441. doi:10.1042/BJ20050441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Artz JD, Dunford JE, Arrowood MJ, et al. Targeting a uniquely nonspecific prenyl synthase with bisphosphonates to combat cryptosporidiosis. Chem Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.017. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maurer-Stroh S, Washietl S, Eisenhaber F. Protein prenyltransferases: anchor size, pseudogenes and parasites. Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.110. doi:10.1515/BC.2003.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakrabarti D, Azam T, DelVecchio C, et al. Protein prenyl transferase activities of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00065-6. doi:10.1016/S0166-6851(98)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohkanda J, Lockman JW, Yokoyama K, et al. Peptidomimetic inhibitors of protein farnesyltransferase show potent antimalarial activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001 doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chakrabarti D, Da Silva T, Barger J, et al. Protein farnesyltransferase and protein prenylation in Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2002 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202860200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moura IC, Wunderlich G, Uhrig ML, et al. Limonene Arrests Parasite Development and Inhibits Isoprenylation of Proteins in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001 doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2553-2558.2001. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.9.2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiesner J, Kettler K, Sakowski J, et al. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors inhibit the growth of malaria parasites in vitro and in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004 doi: 10.1002/anie.200351169. doi:10.1002/anie.200351169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nallan L, Bauer KD, Bendale P, et al. Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors exhibit potent antimalarial activity. J Med Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1021/jm0491039. doi:10.1021/jm0491039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Howe R, Kelly M, Jimah J, et al. Isoprenoid biosynthesis inhibition disrupts Rab5 localization and food vacuolar integrity in Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1128/EC.00073-12. doi:10.1128/EC.00073-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pendyala PR, Ayong L, Eatrides J, et al. Characterization of a PRL protein tyrosine phosphatase from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.11.006. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ayong L, DaSilva T, Mauser J, et al. Evidence for prenylation-dependent targeting of a Ykt6 SNARE in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.11.007. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.D'Alexandri FL, Kimura EA, Peres VJ, et al. Protein dolichylation in Plasmodium falciparum. FEBS Lett. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.042. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ibrahim M, Azzouz N, Gerold P, et al. Identification and characterisation of Toxoplasma gondii protein farnesyltransferase. Int J Parasitol. 2001 doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00268-5. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laredj LN, Licitra F, Puccio HM. The molecular genetics of coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochimie. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mather MW, Vaidya AB. Mitochondria in malaria and related parasites: ancient, diverse and streamlined. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9176-4. doi:10.1007/s10863-008-9176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tonhosolo R, Gabriel HB, Matsumura MY, et al. Intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum biosynthesize menaquinone. FEBS Lett. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.055. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Macedo CS, Uhrig ML, Kimura E a, et al. Characterization of the isoprenoid chain of coenzyme Q in Plasmodium falciparum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11021.x. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Painter HJ, Morrisey JM, Mather MW, et al. Specific role of mitochondrial electron transport in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nature05572. doi:10.1038/nature05572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hino A, Hirai M, Tanaka TQ, et al. Critical roles of the mitochondrial complex II in oocyst formation of rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. J Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs058. doi:10.1093/jb/mvs058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boysen KE, Matuschewski K. Arrested oocyst maturation in Plasmodium parasites lacking type II NADH:ubiquinone dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269399. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.269399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hortua Triana AM, Huynh M, Garavito MF, et al. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.04.009. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin SS, Gross U, Bohne W. Two internal type II NADH dehydrogenases of Toxoplasma gondii are both required for optimal tachyzoite growth. Mol Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07807.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mogi T, Kita K. Diversity in mitochondrial metabolic pathways in parasitic protists Plasmodium and Cryptosporidium. Parasitol Int. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suzuki T, Hashimoto T, Yabu Y, et al. Direct evidence for cyanide-insensitive quinol oxidase (alternative oxidase) in apicomplexan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum: phylogenetic and therapeutic implications. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.038. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roberts CW, Roberts F, Henriquez FL, et al. Evidence for mitochondrial-derived alternative oxidase in the apicomplexan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum: a potential anti-microbial agent target. Int J Parasitol. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.002. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Denecke J, Kranz C. Hypoglycosylation due to dolichol metabolism defects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.013. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Debierre-Grockiego F, Schwarz RT. Immunological reactions in response to apicomplexan glycosylphosphatidylinositols. Glycobiology. 2010 doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq038. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwq038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Macedo CS, Shams-Eldin H, Smith TK, et al. Inhibitors of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor biosyn-thesis. Biochimie. 2003;85:465–72. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luk FCY, Johnson TM, Beckers CJ. N-linked glycosylation of proteins in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.10.012. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gowda DC, Gupta P, Davidson E a. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors represent the major carbohydrate modification in proteins of intraerythrocytic stage Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 1997 doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6428. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.10.6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Samuelson J, Banerjee S, Magnelli P, et al. The diversity of dolichol-linked precursors to Asn-linked glycans likely results from secondary loss of sets of glycosyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409460102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409460102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bushkin GG, Ratner DM, Cui J, et al. Suggestive evidence for darwinian selection against asparagine-linked glycans of Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1128/EC.00197-09. doi:10.1128/EC.00197-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kimura EA, Couto AS, Peres VJ, et al. N-Linked glycoproteins are related to schizogony of the intraerythrocytic stage in Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 1996 doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14452. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.24.14452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luk FCY, Johnson TM, Beckers CJ. N-linked glycosylation of proteins in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.10.012. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu S, Li L. Carotenoid metabolism: biosynthesis, regulation, and beyond. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00708.x. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tonhosolo R, D'Alexandri FL, de Rosso VV, et al. Carotenoid biosynthesis in intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807464200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807464200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu Y. Abscisic acid Signaling through cyclic ADP-ribose in plants. Science (80) 1997 doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2126. doi:10.1126/science.278.5346.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nagamune K, Hicks LM, Fux B, et al. Abscisic acid controls calcium-dependent egress and development in Toxoplasma gondii. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature06478. doi:10.1038/nature06478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sussmann R a C, Angeli CB, Peres VJ, et al. Intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum biosynthesize vitamin E. FEBS Lett. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cordoba E, Salmi M, León P. Unravelling the regulatory mechanisms that modulate the MEP pathway in higher plants. J Exp Bot. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp190. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sauret-Gueto S, Botella-Pavia P, Flores-Perez U, et al. Plastid cues posttranscriptionally regulate the accumulation of key enzymes of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079855. doi:10.1104/pp.106.079855.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tsang A, Seidle H, Jawaid S, et al. Francisella tularensis 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase: kinetic characterization and phosphoregulation. PLoS One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020884. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jawaid S, Seidle H, Zhou W, et al. Kinetic characterization and phosphoregulation of the Francisella tularensis 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (MEP synthase). PLoS One. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008288. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103•.Banerjee A, Wu Y, Banerjee R, et al. Feedback inhibition of deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase regulates the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.464636. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.464636. [These authors demonstrated that P. trichocarpa DXS is inhibited by IPP and DMAPP, suggesting a mechanism for feedback regulation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104•.Bitok JK, Freel Meyers C. 2C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate enhances and sustains cyclodiphosphate synthase IspF activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1021/cb300243w. doi:10.1021/cb300243w. [This study found that the activity of purified E. coli IspF is stabilized by MEP, the IspD substrate, suggesting feed-forward activation. This stabilization was inhibited by FPP, suggesting feedback inhibition.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O'Rourke PEF, Kalinowska-Tłuścik J, Fyfe PK, et al. Crystal structures of IspF from Plasmodium falciparum and Burkholderia cenocepacia: comparisons inform antimicrobial drug target assessment. BMC Struct Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-14-1. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ni S, Robinson H, Marsing GC, et al. Structure of 2C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase from Shewanella oneidensis at 1.6 A: identification of farnesyl pyrophosphate trapped in a hydrophobic cavity. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004 doi: 10.1107/S0907444904021791. doi:10.1107/S0907444904021791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kemp LE, Alphey MS, Bond CS, et al. The identification of isoprenoids that bind in the intersubunit cavity of Escherichia coli 2C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase by complementary biophysical methods. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005 doi: 10.1107/S0907444904025971. doi:10.1107/S0907444904025971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Richard SB, Ferrer J-L, Bowman ME, et al. Structure and mechanism of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase. An enzyme in the mevalonate-independent isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100739200. doi:10.1074/jbc.C100739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109••.Guggisberg AM, Park J, Edwards RL, et al. A sugar phosphatase regulates the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in malaria parasites. Nat Commun. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5467. doi:10.1038/ncomms5467. [These authors described the first known regulator of P. falciparum isoprenoid biosynthesis. Mutation of the sugar phosphatase, PfHAD1, confers fosmidomycin resistance, through increased substrate availability to the MEP pathway.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mullin K a, Lim L, Ralph S a, et al. Membrane transporters in the relict plastid of malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602293103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602293103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brooks CF, Johnsen H, van Dooren GG, et al. The toxoplasma apicoplast phosphate translocator links cytosolic and apicoplast metabolism and is essential for parasite survival. Cell Host Microbe. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wiesner J, Hintz M, Altincicek B, et al. Plasmodium falciparum: detection of the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase activity. Exp Parasitol. 2000 doi: 10.1006/expr.2000.4566. doi:10.1006/expr.2000.4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]