Abstract

Gluconeogenesis is a fundamental metabolic process that allows organisms to make sugars from non-carbohydrate stores such as lipids and protein. In eukaryotes only one gluconeogenic route has been described from organic acid intermediates and this relies on the enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK). Here we show that two routes exist in Arabidopsis, and that the second uses pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK). Gluconeogenesis is critical to fuel the transition from seed to seedling. Arabidopsis pck1 and ppdk mutants are compromised in seed-storage reserve mobilization and seedling establishment. Radiolabelling studies show that PCK predominantly allows sugars to be made from dicarboxylic acids, which are products of lipid breakdown. However, PPDK also allows sugars to be made from pyruvate, which is a major product of protein breakdown. We propose that both routes have been evolutionarily conserved in plants because, while PCK expends less energy, PPDK is twice as efficient at recovering carbon from pyruvate.

During seed germination plants use gluconeogenesis to mobilize noncarbohydrate energy reserves. Here Eastmond et al. show that plants, unlike other eukaryotes, do not solely rely on a gluconeogenic pathway via the enzyme PCK but also use a second pathway relying on PPDK.

During seed germination plants use gluconeogenesis to mobilize noncarbohydrate energy reserves. Here Eastmond et al. show that plants, unlike other eukaryotes, do not solely rely on a gluconeogenic pathway via the enzyme PCK but also use a second pathway relying on PPDK.

Gluconeogenesis allows seedling establishment, a critical phase in the life cycle of plants that is fuelled by the breakdown of seed reserves1. The efficiency of reserve remobilization has an impact on the success of plants in natural communities, but also on crops because seedling vigour is a key determinant of yield2. Starch, lipids and proteins can all be used, although lipid reserves are considered the most widely distributed in nature1. In the case of lipids, the first step in remobilization involves the hydrolysis of triacylglycerols, stored in oil bodies, to release free fatty acids and glycerol. Both products serve as gluconeogenic substrates but fatty acids account for ∼95% of the carbon. The fatty acids enter the peroxisome and are activated to fatty acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) so that they can undergo β-oxidation. The acetyl-CoA produced by this process is then converted to organic acids via the glyoxylate cycle3.

In plants it is widely accepted that phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK, EC 4.1.1.49) then plays a pivotal role in gluconeogenesis by catalysing the conversion of the C4 dicarboxylic acid oxaloacetic acid to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)4,5,6,7,8. This mechanism for PEP synthesis is generally believed to be the only physiological route by which eukaryotes bypass the practically irreversible glycolytic reaction catalysed by pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40). However, in certain bacteria an alternate pathway has also been described that allows C4 dicarboxylic acids to be converted via pyruvate to PEP for gluconeogenesis. For example, Escherichia coli can use the combined activities of malic enzyme (ME, EC 1.1.1.39) and PEP synthetase (EC 2.7.9.2)9,10,11,12, while Acetobacter xylinum and Sinorhizobium meliloti can use ME and pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK, EC 2.7.9.1)13,14.

PPDK is best known for its role in C4 photosynthesis in plants15. However, PPDK genes appear to be present in all species, regardless of their photosynthetic mechanism16. The possibility that pyruvate phosphorylation contributes to plant gluconeogenesis was investigated in the 1960s through the application of 14C-labelled pyruvate17 and alanine18 to the endosperm of germinated castor beans (Ricinus communis). The efficiency of sugar labelling from pyruvate was low and varied with the position of the label, consistent with pyruvate being decarboxylated rather than being converted directly to PEP17. A further study showed that the efficiency of sugar labelling from alanine was much greater, despite the fact that alanine is directly deaminated to pyruvate18. However, this discrepancy was attributed to a difference in experimental design for alanine feeding that promoted dark re-fixation of 14CO2 (ref. 18). Therefore, the data from these studies suggested that direct phosphorylation of pyruvate (for example, by PPDK) does not contribute to gluconeogenesis in castor endosperm17,18.

In the model oilseed Arabidopsis thaliana a series of more recent studies have shown that both PPDK16 and PCK1 (ref. 7) are expressed following seed germination, and that disruption of PCK1 function has a surprisingly modest effect on early seedling growth7,8. These data raise the possibility that, in spite of the existing evidence from studies on castor beans17,18, PPDK might provide an alternate route for organic acids to support gluconeogenesis in Arabidopsis. We therefore decided to test this hypothesis using a molecular genetic approach.

Results

PCK1 and cytosolic PPDK are induced following germination

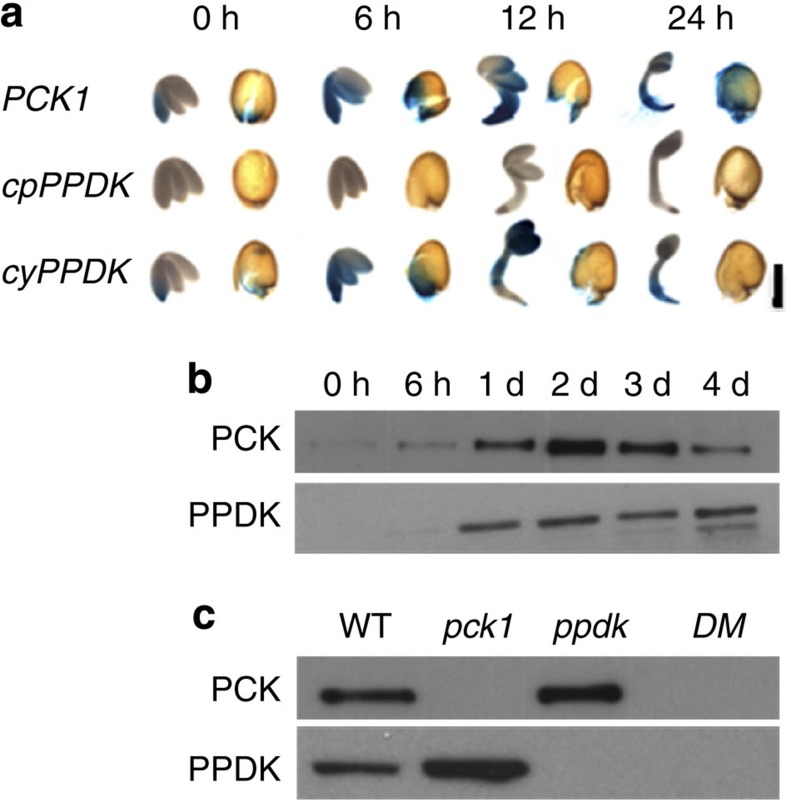

Analysis of transcript abundance has indicated that both PCK1 and PPDK transcripts can be detected in Arabidopsis seeds following germination8,16. In order to compare the temporal and spatial patterns of PCK1 and PPDK expression over the course of germination and early seedling growth transgenic lines expressing promoter-gene reporter constructs were created and analysed. In Arabidopsis, because of alternate promoter elements, one PPDK gene encodes both a cytosolic and chloroplastic protein16. Translational fusions between each gene and uidA19, coding for GUS (β-glucuronidase), show that cytosolic PPDK accumulates coordinately with PCK1 (Fig. 1a). In both cases GUS expression is first detected in the radicle of the embryo and in the micropylar region of the aleurone where the seed coat first splits and the GUS expression then spreads to the embryo cotyledons and hypocotyl as they expand (Fig. 1a). In PCK1, GUS expression also spreads across the aleurone that remains attached to the seed coat; however, in the case of cytosolic PPDK the GUS expression does not to persist (Fig. 1a). To confirm that PCK1 and PPDK proteins also accumulate in wild-type seedlings they were monitored by immunoblotting (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). The abundance of both proteins increases dramatically following seed germination and is highest around 2 days after the start of imbibition (Fig. 1b), when the rate of storage reserve breakdown is also known to be greatest1. PCK abundance then decreases as the seedling develops while PPDK remains (Fig. 1b). The expression pattern of PCK1 and PPDK in Arabidopsis are therefore consistent with a potential role for both proteins in gluconeogenesis.

Figure 1. Cytosolic PPDK and PCK1 are coordinately expressed following seed germination.

(a) Histochemical staining of transgenic plants containing genomic fusions of PCK1::uidA (PCK1), chloroplastic PPDK::uidA (cpPPDK) and cytosolic PPDK::uidA (cyPPDK) from 0 to 24 h following germination. (b) Immunoblots for PCK and PPDK in wild-type (WT) Arabidopsis seedlings from 0 to 4 days after the start of imbibition. (c) Immunoblots for PCK and PPDK in 2-day-old WT, pck1, ppdk and ppdk-pck1 double mutant (DM) seedlings. Scale bar in a, 0.5 mm.

PCK1 and PPDK are both required for seedling establishment

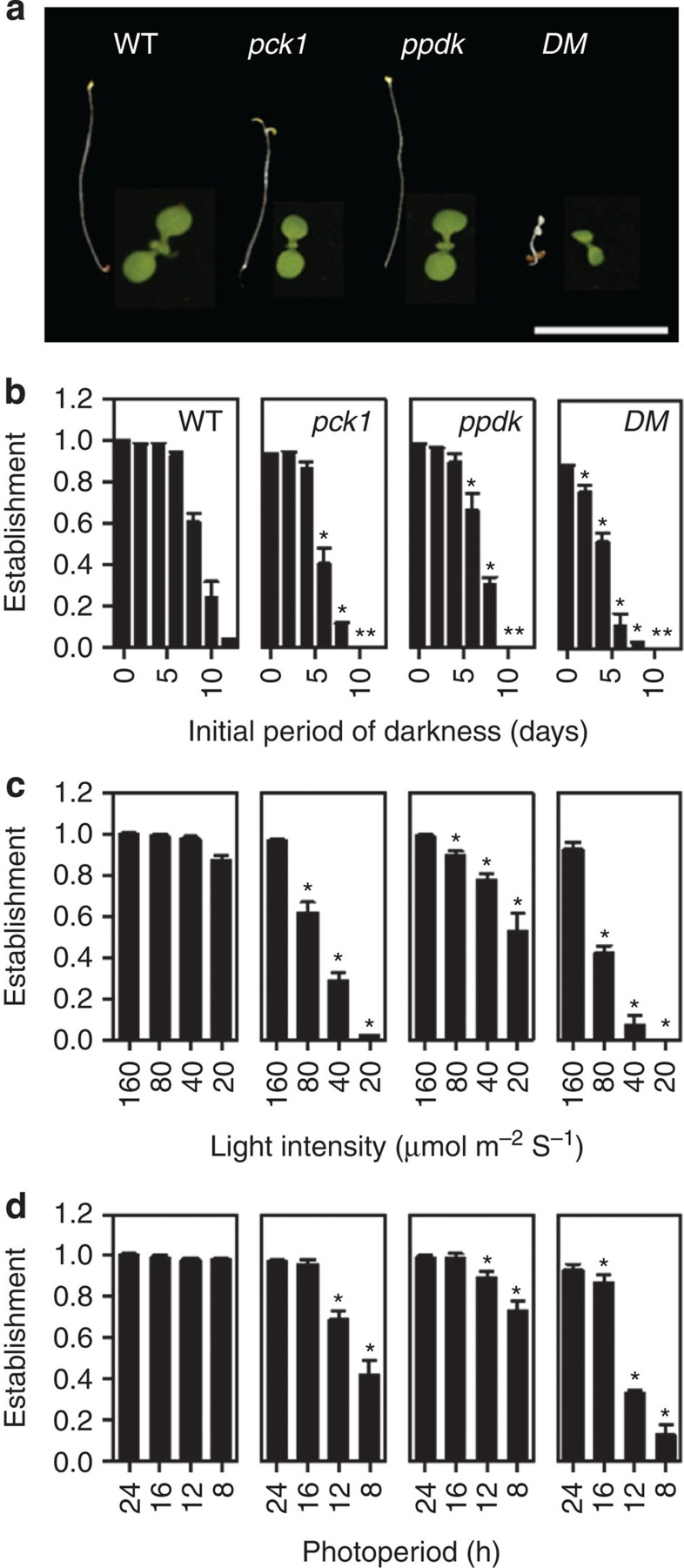

To allow us to investigate the function of PPDK in Arabidopsis, we obtained ppdk and pck1 (ref. 8) T-DNA insertion mutants and constructed a ppdk-pck1 double mutant. Immunoblotting confirmed that 2-day-old ppdk and pck1 seedlings lack their respective PPDK and PCK proteins and are therefore null mutants (Fig. 1c). Disruption of seed reserve mobilization is known to inhibit early seedling growth and establishment in Arabidopsis1. Although PCK is considered to be essential for gluconeogenesis, pck1 seedling growth is only modestly affected, either in the light or in darkness7,8 (Fig. 2a). Seedling development in ppdk appears to be normal but ppdk-pck1 shows a severe reduction in growth rate, measured by cotyledon expansion in the light or hypocotyl extension in the dark (Fig. 2a). Early seedling growth can therefore be supported by PPDK, in the absence of PCK. The provision of mineral nutrition (Murashige and Skoog basal salts) makes no difference to hypocotyl extension in the dark, but exogenous sugar can completely rescue ppdk-pck1 growth (Supplementary Fig. 2a), which is consistent with the genes functioning in gluconeogenesis1. The ppdk-pck1 mutant could also be partially complemented using a genomic clone encoding cytosolic PPDK, while chloroplastic PPDK had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 2b). High activities of PPDK and PCK have been reported in cells around veins of Arabidopsis20. A strategy that combined use of hairpin RNA interference constructs for each gene with a vein-specific enhancer trap21 suggested that PPDK and PCK in cells around veins are not required for seedling growth (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 2. PPDK and PCK are required for normal seedling growth and establishment.

(a) Representative images of WT, ppdk, pck1 and DM seedlings grown in the dark (left) or light (right) for 5 days. Scale bar, 1 cm. The effect of (b) increasing periods of darkness before being transferred to light, (c) reduced light intensity and (d) reduced day length on the frequency of establishment of WT, pck1, ppdk and DM seedlings (as defined by the proportion of seedlings that develop true foliage leaves within 4 weeks after germination). Data are shown as means±s.e. from three batches of a hundred seeds and asterisks represent a statistical difference from WT (P<0.05, LSD test, n=3). Light intensity was 160 μmol m−2 s−1 except in c.

Although ppdk seedlings appear to grow normally under optimal laboratory conditions (Fig. 2a) such conditions are uncommon in natural environments. We therefore assessed the absolute fitness of ppdk plants by measuring the frequency of seedling establishment (equivalent to survival) when seeds are sown under a range of suboptimal light environments that are more prevalent in nature22. Using this assay, fewer ppdk seedlings survived (P<0.05, least significant difference (LSD) test, n=3) than wild type (Fig. 2b–d). This included when access to light was delayed for a period after the completion of germination (Fig. 2b), as would be the case beneath the soil, or when light levels were low, or days were short (Fig. 2c,d). Survival of pck1 seedlings was also reduced under suboptimal conditions and this was accentuated in ppdk-pck1 (Fig. 2). These data suggest that both proteins are required to maximize the frequency of seedling establishment under suboptimal growth conditions. Even under optimal conditions pck1 and ppdk-pck1 seedlings that do establish exhibit delayed rosette growth and flowering (Supplementary Fig. 4).

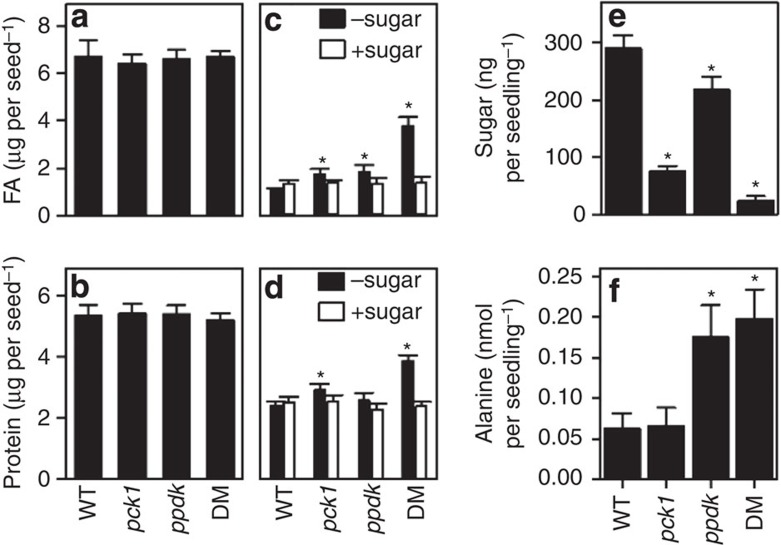

PCK1 and PPDK are both required to mobilize storage reserves

To investigate why PCK and PPDK are both needed for optimal seedling establishment, we carried out metabolite analysis. The total fatty acid and protein content of pck1, ppdk and ppdk-pck1 seeds (Fig. 3a,b) was not significantly different from wild type (P>0.05, F-test, n=4), indicating that compromised seedling growth and establishment (Fig. 2) cannot be explained by a lack of seed reserves. Although the degradation of fatty acids and protein was impaired in ppdk-pck1 seedlings grown in the absence of exogenous sugar, when sugar was provided the reserves were readily broken down (Fig. 3c,d). This is consistent with previous reports showing that mutant seedlings with gluconeogenic defects can still use lipids as a respiratory carbon source, particularly when sugar is provided7,22,23.

Figure 3. PPDK and PCK1 are required for sugar accumulation following seed germination.

Quantification of total fatty acid (a,c) and protein (b,d) content in seeds (a,b) and 5-day-old seedlings (c,d) of WT, ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 grown on MS basic media, plus or minus 30 mM glucose. (e) Soluble sugar content in 2-day-old WT pck1, ppdk and DM seedlings. (f) Alanine content of two day old seedlings of WT, ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) basic media. Data in e are the sum of sucrose, glucose and fructose. All values are the mean±s.e. of measurements on four separate pools of seeds or seedlings and asterisks represent a statistical difference from WT (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4).

In wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings soluble sugars accumulate shortly after germination as a result of gluconeogenesis from seed-storage lipids and this is impaired in mutants that are deficient in the pathway23. We found that sugar levels are reduced by ∼70% in 2-day-old pck1 seedlings, consistent with the role of PCK in gluconeogenesis8 (Fig. 3e). However, the ppdk mutant also has ∼30% less sugar, and ppdk-pck1 has ∼90% less sugar than wild type (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4). The significant impact of pck1 and ppdk on seedling sugar content, and the additive effect observed in ppdk-pck1, suggest that PCK and PPDK are both required for normal gluconeogenic flux.

In addition to lipids, proteins can also serve as a gluconeogenic substrate18, and in some seeds they are the predominant reserve24. The carbon backbones of alanine, cysteine, glycine, serine, threonine and tryptophan can all be metabolized to pyruvate, the substrate of PPDK, and these amino acids make up around one-third of seed-storage protein in Arabidopsis. Uniquely, alanine is directly and reversibly converted to pyruvate and analysis of alanine content showed that in ppdk and ppdk-pck1 seedlings, it is increased (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4) approximately threefold compared with pck1 or wild type (Fig. 3f). This suggests an important gluconeogenic function for PPDK in remobilizing carbon skeletons present in amino acids that are catabolized to pyruvate.

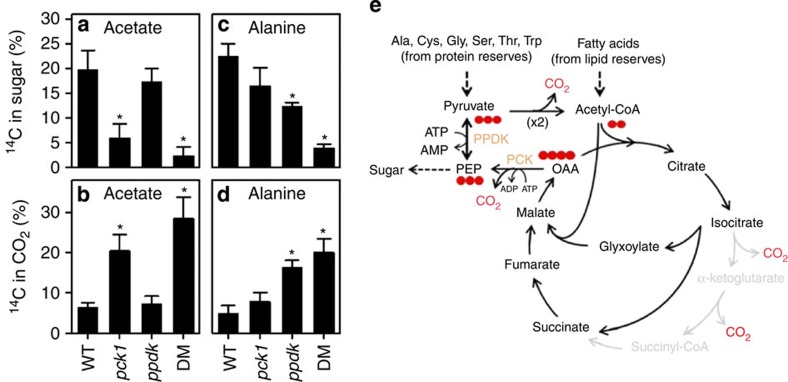

PCK1 and PPDK play distinct roles in mobilization of stores

To follow the metabolism of gluconeogenic substrates derived from lipids and protein, short-term radiolabelling experiments were performed on 2-day-old seedlings using [2-14C]-acetate and [U-14C]-alanine18,23. Seedlings were labelled for 4 h and the redistribution of 14C into metabolic fractions was determined and expressed as a percentage of the total metabolized (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). When wild-type seedlings were fed either acetate or alanine, ∼20% of the total 14C was detected in sugars (Fig. 4a), suggesting that both metabolites act as gluconeogenic substrates18,23. Feeding 14C-acetate to pck1 seedlings resulted in a substantial reduction in the percentage of 14C found in sugars (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4) but no change in the percentage of 14C in this fraction was observed in ppdk (Fig. 4a,b). On the other hand, when 14C-alanine was fed to ppdk seedlings, the percentage of 14C in sugars was significantly reduced (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4), while no change was seen in pck1 (Fig. 4c,d). In ppdk-pck1 the percentage of label found in sugars following 14C-alanine feeding was significantly (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4) lower than in the ppdk single mutant; however, the percentage of label in sugar from 14C-acetate feeding was similar to pck1. These labelling patterns are consistent with a model (Fig. 4e) in which PPDK participates in gluconeogenesis by remobilizing amino acids such as alanine that give rise to pyruvate, while PCK is primarily involved in remobilization of acetyl-CoA derived from lipids.

Figure 4. PPDK and PCK define two separate gateways for gluconeogenesis that enable efficient utilization of both lipid and protein reserves.

Redistribution of 14C label from [2-14C]acetate (a,b) and [U-14C]alanine (c,d) into sugars and CO2 in 2-day-old seedlings. Data are means±s.e. from four separate pools of 100 seedlings and asterisks represent a statistical difference from WT (P<0.05, LSD test, n=4). (e) Schematic outlining PPDK- and PCK-dependent gluconeogenesis from lipids and amino acids during early seedling growth. Note that glycerol is also a minor product of lipid breakdown (∼5% of the carbon in storage oil) and enters gluconeogenesis downstream of PEP. A minimum of two moles of pyruvate are required to form one mole of PEP via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and the glyoxylate or tricarboxylic acid cycle, while the molar ratio is 1:1 using PPDK. However, when employing PPDK an additional ATP is necessary to regenerate ADP from AMP.

In ppdk, more than 10% of 14C-alanine is still metabolized to sugars versus ∼20% in wild type (Fig. 4c). The most likely explanation for this is that in the absence of PPDK, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (EC 4.1.1.1), providing carbon skeletons to the glyoxylate or tricarboxylic acid cycles (Fig. 4e). The observation that total protein breakdown is not significantly impaired in ppdk seedlings (Fig. 3d) is also consistent with a diversion of flux rather than a blockage. The glyoxylate cycle in plants spans multiple subcellular compartments1 and thus the model in Fig. 4e is a simplification. Nevertheless, the route involving pyruvate dehydrogenase leads to the net loss of at least half the carbon as CO2, while conversion of pyruvate to sugar via PPDK results in no loss (Fig. 4e). Indeed, the percentage of 14C released as CO2 when ppdk is fed alanine is substantially greater than in wild type (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, animals and yeast lack PPDK but, by using a single pathway that combines pyruvate carboxylase (PC, EC 6.4.1.1) with PCK, also achieve no net loss of carbon as CO2 when pyruvate supports gluconeogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 5). When lipids are used as a gluconeogenic substrate in Arabidopsis the carbon conversion efficiency would be the same whether PCK or PPDK are employed because PPDK must be coupled with the decarboxylating activity of ME (Supplementary Fig. 4), but PPDK has a higher cost in ‘energy' because ATP is hydrolyzed to AMP, not ADP, and therefore requires an additional ATP to regenerate ADP via adenylate kinase (Fig. 4e). The strong impact of pck1 on sugar labelling from 14C-acetate (Fig. 4a) does not support a substantial role for ME in mediating flux from lipids to PEP via PPDK. We therefore propose that plants use a PPDK-dependent gluconeogenic pathway because it allows the most efficient recovery of carbon skeletons from amino acids in seed-storage proteins that are metabolized via pyruvate, while a PCK-dependent pathway is also present because it is more ‘energy-efficient' for substrates metabolized to C4 dicarboxylic acids, such as lipids and other amino acids.

PCK1 and PPDK deficiency leads to sugar-starvation responses

Compromised gluconeogenesis during early seedling growth would eventually be expected to lead to broad alterations to primary metabolism, and to induce sugar-starvation responses23. To address this we undertook global analysis of gene expression using the GeneChip Arabidopsis ATH1 Genome Array from Affymetrix23. Analysis of transcript abundance in 2-day-old seedlings of the mutant genotypes provided no evidence for the suppression of other genes known to play a direct role in lipid remobilization1. In fact, there was evidence of modest upregulation of several genes in pck1 and ppdk-pck1 (Table 1). However, the most striking effect on global gene expression in several of the mutants was associated with known sugar starvation marker (SSM) genes. Baena-Gonzalez et al.25 previously identified a core set of 278 such genes in Arabidopsis. When this list was cross-referenced with those genes more than twofold up- or downregulated in the mutants (Table 2), the ppdk mutant had the lowest degree of overlap (four genes), while ppdk-pck1 had the greatest (108 genes; Table 2). A further comparison with published microarray data23 for 2-day-old seedlings of the glyoxylate cycle mutants, isocitrate lyase (icl) and malate synthase (mls), revealed a similar degree of overlap (180 and 64 genes, respectively) with the 278 SSM genes. Finally, ppdk-pck1 also shares a total of 823 more than twofold up- or downregulated genes in common with icl and 376 genes in common with mls (Table 2). We conclude that when PPDK is lacking, gluconeogenesis is reduced, but that this is not sufficient to lead to a significant sugar-starvation response under optimal growth conditions. However, when both PCK and PPDK are inactive, the impact on gluconeogenesis is eventually sufficient to induce a wide-scale starvation response as has been observed in glyoxylate cycle mutants23.

Table 1. Effects of ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 on expression of genes required for gluconeogenesis from storage lipids.

| Name | AGI | Log2-fold change versus WT |

SAM d-score |

P value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppdk | pck1 | DM | ppdk | pck1 | DM | ppdk | pck1 | DM | ||

| SDP1 | At5g04040 | 0.12 | 0.49* | 1.06* | 0.49 | 1.96 | 4.82 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| GLI1 | At1g80460 | −0.07 | 0.29 | 0.52* | −0.35 | 1.55 | 3.43 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| SDP6 | At3g10370 | −0.02 | 0.49* | 0.15 | −0.08 | 2.39 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| PXA1 | At4g39850 | 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 0.33 |

| LACS6 | At3g05970 | −0.12 | 0.69* | 0.41 | −0.36 | 1.94 | 1.14 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| LACS7 | At5g27600 | −0.33 | 0.66* | 0.51 | −0.91 | 2.07 | 1.82 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| ACX1 | At4g16760 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 1.07 | 2.17 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| ACX2 | At5g65110 | −0.06 | 0.32 | 0.40 | −0.21 | 1.16 | 1.39 | 0.80 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| ACX3 | At1g06290 | −0.19 | 0.45 | 0.70* | −0.64 | 1.31 | 2.74 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| ACX4 | At3g51840 | 0.01 | 0.46* | 0.85* | 0.05 | 3.92 | 8.79 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MFP2 | At3g06860 | −0.17 | 0.94* | 0.97* | −0.40 | 2.22 | 2.61 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| AIM | At4g29010 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.26 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.61 |

| KAT2 | At2g33150 | −0.18 | 0.52* | 0.50* | −0.67 | 2.39 | 2.84 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| PMDH1 | At2g22780 | −0.27 | 1.14* | 0.82 | −0.59 | 2.57 | 1.74 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| PMDH2 | At5g09660 | 0.12 | −0.45 | −0.63* | 1.01 | −1.58 | −4.59 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| CSY2 | At3g58750 | 0.13 | 0.98* | 1.22* | 0.82 | 7.45 | 6.83 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| CSY3 | At2g42790 | −0.20 | 0.78* | 0.92* | −0.61 | 2.41 | 3.44 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| SDP2 | At3g27820 | −0.46 | 0.36 | 0.45 | −1.45 | 1.12 | 1.58 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| MLS | At5g03860 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.70 | −0.01 | 1.86 | 2.13 | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| ICL | At3g21720 | −0.12 | 0.23 | 0.38* | −0.64 | 1.27 | 3.07 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| PCK1 | At4g37870 | 0.05 | −4.73* | −7.52* | 0.14 | −13.27 | −15.07 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PPDK | At4g15530 | −7.38* | 1.79* | −6.71* | −17.61 | 4.15 | −16.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

DM, double mutant; WT, wild type.

Analysis of gene expression in 2-day-old wild type, ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 seedlings for genes known to be involved in mobilization of storage lipids1. Three microarray experiments were performed for each genotype and the values marked with an asterisk show a statistically significant difference from WT (P<0.05, SAM, n=3), determined using the significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) procedure45.

Table 2. Overlap between differentially expressed genes in ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 and genes that are known to respond to sugar-starvation.

| Genotypes | Number of overlapping genes |

|---|---|

| ppdk versus SSM | 4 (1%) |

| pck1 versus SSM | 41 (15%) |

| mls versus SSM | 64 (23%) |

| DM versus SSM | 108 (38%) |

| icl versus SSM | 180 (64%) |

| ppdk versus mls | 5 |

| ppdk versus icl | 9 |

| ppdk versus pck1 | 14 |

| ppdk versus DM | 18 |

| pck1 versus mls | 168 |

| pck1 versus icl | 328 |

| DM versus mls | 376 |

| DM versus icl | 823 |

| DM versus pck1 | 946 |

DM, double mutant; SSM, Sugar starvation marker; SAM, Statistical Analysis of Microarrays.

Discussion

Our combined data show that, Arabidopsis, in common with some bacteria, uses PPDK as a gluconeogenic enzyme. To our knowledge, this is the first time that two distinct routes for the entry of organic acids into gluconeogenesis have been described in a eukaryote. Uniquely, we also provide evidence that the two routes have specialized functions in lipid and protein mobilization, respectively. Our findings are also surprising because they appear to be at odds with previous radiolabelling studies using endosperm of germinated castor beans, which suggested that very little gluconeogenic flux occurs through direct phosphorylation of pyruvate17,18. RNA sequencing data have shown that PPDK is expressed in germinated castor beans26. However, there might still be variation in PPDK activity between the two species and/or tissues. Castor seeds are anatomically very different from Arabidopsis, storing the bulk of their reserves in their large endosperm. In contrast, Arabidopsis seeds possess a greatly reduced endosperm consisting of a single-cell layer (aleurone) with the majority of the reserves stored in the embryo8. Using a translational fusion between cytosolic PPDK and GUS19, we observed that expression of PPDK in the aleurone of germinated Arabidopsis seed is much less widespread and persistent than in the embryo (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, variation in PPDK expression does exist between different storage tissues in the same seed.

It is also conceivable that PPDK does support gluconeogenesis in castor endosperm despite the inefficiency with which it metabolizes exogenous pyruvate to sugars17. There is now considerable evidence that metabolic channelling takes place within glycolysis in Arabidopsis27 and in castor endosperm analysis of changes in metabolic intermediates in response to anoxia has also suggested that gluconeogenesis and glycolysis occur in separate intracellular regions28. It is therefore possible that supplying pyruvate to endosperm slices17 results in this metabolite entering the mitochondrion and being respired, whereas pyruvate that is produced endogenously from amino acids, such as alanine18, may be channelled into gluconeogenesis. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate whether the compartmentalization and enzymatic properties of alanine aminotransferases (EC 2.6.1.2) could account for the comparatively efficient metabolism of alanine to sugars18. Arabidopsis contains four alanine aminotransferase genes and at least two are expressed in seedlings29,30.

In theory, the use of PPDK as a gluconeogenic enzyme is advantageous because it allows the most efficient remobilization of carbon skeletons from substrate that must be metabolized via pyruvate, such as certain gluconeogenic amino acids. Indeed, this subset of amino acids makes up around one-third of Arabidopsis seed-storage protein. It is plausible that the greater efficiency with which pyruvate can be used for gluconeogenesis is also a reason why PPDK or PEP synthase are used for gluconeogenesis in some bacteria, while animals and yeast employ an alternative route combining PC and PCK (Supplementary Fig. 5). To our knowledge there is no firm molecular evidence that PEP synthase or PC exist in plants. Arabidopsis does have six genes encoding ME31,32 that could allow PPDK to make a contribution to gluconeogenic flux from lipids, as has been shown for acetate in bacteria13,14. However, 14C-acetate labelling studies (Fig. 4a) and mutant analysis (Supplementary Table 2) suggest that this is not a major metabolic route in Arabidopsis.

In order for Arabidopsis PPDK to function in gluconeogenesis it must catalyse the synthesis of PEP in vivo. A recent study has shown that at cytosolic pH the specific activity of recombinant Arabidopsis PPDK is approximately eightfold lower in the PEP-forming direction than it is in the pyruvate-forming direction33. However, the Km for pyruvate (17 μM) is ∼17-fold lower than it is for PEP and, at physiological pyruvate concentrations (∼0.1 mM), PEP formation may therefore be favoured33. Furthermore, although high cytosolic concentrations of pyrophosphate (PPi) should inhibit PEP formation, PPi has relatively little effect on Arabidopsis PPDK activity in vitro33. Arabidopsis has also been found to contain an H+-pyrophosphatase that supresses PPi accumulation during early post-germinative growth and promotes gluconeogenesis34.

Given our discovery that PPDK plays a role in gluconeogenesis in Arabidopsis, it will be important to understand how this enzyme is regulated during the phase of seed-storage reserve mobilization. Gibberellins (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA) are known to play a key antagonistic role in seed dormancy and the control of germination35 and there is also evidence that they regulate storage-reserve breakdown, although their role appears to vary with species and tissue1. In Arabidopsis, transcriptional induction of PCK1 is repressed by ABA in the embryo but not the endosperm (aleurone) tissue of the seed8. A preliminary analysis of the effect of ABA on expression of the cytosolic PPDK–GUS fusion in embryos of imbibed seeds suggests that PPDK is not sensitive to transcriptional repression by ABA (Supplementary Fig. 6) and thus its regulation differs from PCK1 (ref. 8). However, PPDK may be subject to other levels of regulation. For example, it is known that the PPDK-regulatory protein (PDRP) uses phosphoryl-donor nucleotides to reversibly phosphorylate an active-site threonine residue in PPDK, thereby inactivating the enzyme and a cytosolic PDRP has been identified in Arabidopsis36, although its precise physiological role is not yet understood.

In conclusion, the progressively compromised seedling growth evident in Arabidopsis ppdk, pck1 and ppdk-pck1 and the reduction in carbon recovery from seed-storage reserves in both the double and single mutants clearly shows that the gluconeogenic function of both PCK and PPDK enzymes is of relevance to plant fitness. The superior carbon recovery that PPDK allows would be advantageous to both bacteria and plants when growth is dependent on substrates such as lactate and gluconeogenic amino acids that can give rise to pyruvate. PPDK genes appear to be present in all plant genomes that have so far been sequenced16 and there is also evidence that PPDK is expressed in the storage reserve tissues of germinated seeds from a taxonomically diverse range of species including castor bean26, poplar37 (Populus balsamifera), rice38 (Oryza sativa), barley39 (Hordeum vulgare) and maize40 (Zea mays; Supplementary Table 3). Although it is possible that Arabidopsis independently and convergently recruited PPDK for gluconeogenesis, it is therefore more likely that both bacterial and plant lineages have maintained PPDK for this purpose since their divergence around 1.3 billion years ago.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The PPDK and PCK1 insertional mutants in Arabidopsis ecotype Col0 (ppdk: SALK_073368 and pck1–2; SALK_032133) were identified in the SALK T-DNA collection41 and obtained from the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre (uNASC, University of Nottingham, UK). To assess seedling phenotype, metabolite content, protein and transcript levels, and to perform radiolabelling experiments, seeds were sterilized and sown on plates containing 0.8% w/v agar. Where stated, Murashige and Skoog basal salts (pH 5.7), 30 mM glucose and 20 μM ABA were also included. The seeds were then stratified for 3 days at 4 °C, subjected to a 30-min light pulse of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 and routinely maintained in the light or dark at 22 °C for up to 5 days. Experiments to determine the frequency of seedling establishment under different light regimes were performed as described previously22. In soil, Arabidopsis seed was sown on 3:1 compost:vermiculite in controlled growth chambers with 16-h photoperiod, at 20 °C, 60% humidity and 150 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity. To assess seed production, plants were grown to maturity. Seeds were removed from siliques and then sieved through a 0.4-mm mesh. For hypocotyl extension assays and vegetative plant growth and development, seedlings were imaged using a digital camera and hypocotyl length determined using the ImageJ software. Green fluorescent protein and chlorophyll were imaged using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope as described previously16.

Plasmid construction through to plant transformation

To generate hairpin constructs for both PCK and PPDK, sense and antisense regions of each gene were obtained by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 4. They were then fused to the LIP1 intron 4 and placed under control of the GAL4VP16 upstream activation sequence as described previously21. Briefly, SacI and KpnIBglII sites were added to each sequence and used to clone sense fragments of each gene upstream of the LIP1 intron21. BamHI and SacI sites were used to allow antisense fragments of each gene to be cloned downstream of the LIP1 intron21. The BglII and SacI sites were then used to excise these fragments from the cloning vector and then place them into a binary vector containing the GAL4VP16 upstream activation sequence21. Using floral dipping Agrobacterium tumefaciens was used to insert each construct into Arabidopsis and transformants were selected on hygromycin21. Homozygous single insert lines for PPDK and PCK were crossed to obtain double knockdown lines.

Metabolite measurements and radiolabelling experiments

Total fatty acid content and composition was determined using gas chromatography of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) following direct transmethylation of tissue samples22. Pools of 20 seeds or seedlings were added to vials containing 10 μg of heptadecanoic acid internal standard. To each vial 500 μl of 1 N methanolic-HCl was added. The sealed vials were heated at 85 °C for 2 h and the FAMEs were partitioned by adding 200 μl of hexane and 250 μl of 0.9% (w/v) KCl. The hexane phase was analysed by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection. One-microlitre injections were made into a 10 m × 0.1 mm 0.2-μm film thickness SGE BPX70 column using a 250:1 split ratio and H as the carrier gas. The oven was run at 150 °C for 0.1 min and ramped to 220 °C at 16 °C min−1. FAMEs were quantified by the peak area with reference to the internal standard. Soluble sugars (sucrose, glucose and fructose) were extracted from pools of 50 seedlings by three sequential washes in 80% (v/v) ethanol at 85 °C for 1 h. The pooled washed were then dried in a vacuum evaporator and the sugars dissolved in water and quantified using a series of enzyme-coupled assays linked to NADPH production42. Alanine was measured in the same extract as sugars using the Alanine Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), following the manufacturer's protocol. 14C-labelling experiments were performed on 2-day-old seedlings following the method described in ref. 23. Pools of 100 seedlings of each genotype were incubated in the dark for 4 h in sealed vials containing 0.2 ml of 1 mM [2-14C]-acetate or [U-14C]-alanine (20 MBq mmol−1) and 50 mM Mes/KOH (pH 5.2), during which time-released 14CO2 was trapped in a separate well containing 5 N KOH. The soluble components of the seedlings were then extracted in 80% (v/v) ethanol at 80 °C followed by water at 40 °C. The total soluble extracts were combined, and the hydrophobic components were extracted with chloroform. The ethanol-soluble components were dried, resuspended in water and then further separated into neutral, basic and acidic fractions using ion exchange chromatography. The amount of 14C in each fraction was quantified by scintillation counting. In control experiments, >90% of the 14C in the neutral fraction was found to co-migrate with sucrose, glucose and fructose standards following paper chromatography.

Immunoblots and gene expression analysis

Soluble proteins were extracted by homogenizing 2-day-old seedling material in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The homogenate was spun in a centrifuge, the supernatant removed and the protein content quantified using the Bradford Assay. For immunoblotting 10 μg of protein was loaded on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. Antibody hybridizations were performed with primary antibodies to either PPDK36 diluted 1:10,000, or PCK43 diluted 1:1,000. GUS was visualized after staining and leaf-clearing as described previously20 Total RNA was extracted from 2-day-old seedlings using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative PCR8 was conducted on multiple hairpin lines for PCK, PPDK and the double PCK-PPDK line using primers specific to each gene (see Supplementary Table 4). For microarray analysis, RNA amplification, labelling, fragmentation and hybridization to ATH1 genome arrays were carried out at NASC (http://affymetrix.Arabidopsis.info/). Data were pre-processed with the GeneChip robust multiarray average image-processing normalization method44.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was used to assess the differences in growth and metabolism between genotypes or treatments. Following significant (P<0.05) F-test results, the means of interest were compared using the appropriate LSD value at the 5% (P=0.05) level of significance, on the corresponding degrees of freedom. The GenStat (2011, 14th edition; VSN International) statistical system was used for these analyses. The significance analysis of microarray procedure45 was used to define significantly up- and downregulated genes (P<0.05) with at least a twofold increase in expression.

Author contributions

P.J.E., H.M.A., K.P., S.A., B.P.W., G.N.M., C.P.C. and A.N.-N. performed the research. P.J.E., A.R.F. and J.M.H. designed the programme and wrote the manuscript. J.M.H. initiated and oversaw the work.

Additional information

Accession codes. Microarray data are available at uNASC (http://Arabidopsis.info/) under the registration number: NASCARRAY534, and also the iPlant collaborative at http://data.iplantcollaborative.org/quickshare/d884b0174e5c7974/Exp534.zip.

How to cite this article: Eastmond, P. J. et al. Arabidopsis uses two gluconeogenic gateways for organic acids to fuel seedling establishment. Nat. Commun. 6:6659 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7659 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-6, Supplementary Tables 1-4

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biotechnology and Biology Sciences Research Council for funding J.M.H. (P18931 and a studentship to B.P.W.) and P.J.E. (BB/G009724/1 and BB/K002147/1), the Isaac Newton Trust and the Max-Planck Gesellschaft for funding and ATC for a CASE studentship to H.M.A.

References

- Graham I. A. Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 115–142 (2008) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage W. E., Clay H. A., Lynn J. R. & Morris K. Towards a genetic understanding of seed vigour in small-seeded crops using natural variation in Brassica oleracea. Plant Sci. 179, 582–589 (2010) . [Google Scholar]

- Baker A., Graham I. A., Holdsworth M., Smith S. M. & Theodoulou F. L. Chewing the fat: β-oxidation in signalling and development. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 124–132 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict C. R. & Beevers H. Formation of sucrose from malate in germinating castor beans. I. Conversion of malate to phosphoenol-pyruvate. Plant Physiol. 36, 540–544 (1962) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoulou F. L. & Eastmond P. J. Seed storage oil catabolism: a story of give and take. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 322–328 (2012) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegood R. C. & ap Rees T. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and gluconeogenesis in cotyledons of Cucurbita pepo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 524, 207–218 (1978) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylott E. L., Gilday A. D. & Graham I. A. The gluconeogenic enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in Arabidopsis is essential for seedling establishment. Plant Physiol. 131, 1834–1842 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield S. et al. Reserve mobilization in the Arabidopsis endosperm fuels hypocotyl elongation in the dark, is independent of abscisic acid, and requires PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE CARBOXYKINASE1. Plant Cell 16, 2705–2718 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R. A. & Kornberg H. L. Direct synthesis of phosphoenolpyruvate from pyruvate by Escherichia coli. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 168, 263–26 (1967) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldie A. H. & Sanwal B. D. Genetic and physiological characterization of Escherichia coli mutants deficient in phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase activity. J. Bacteriol. 141, 1115–1121 (1980) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E. J. & Juni E. Two routes for synthesis of phosphoenolpyruvate from C4-dicarboxylic acids in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 59, 1204–1210 (1974) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M.-K., Rohlin L., Kao K. C. & Liao J. C. Global expression profiling of acetate-grown Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13175–13183 (2002) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benziman M. & Eizen N. Pyruvate-phosphate dikinase and the control of gluconeogenesis in Acetobacter xylinum. J. Biol. Chem. 246, 57–61 (1971) . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteras M., Driscoll B. T. & Finan T. M. Increased pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase activity results in an alternative gluconeogenic pathway in Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti. Microbiology 143, 1639–1648 (1997) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd J. M. & Covshoff S. The regulation of gene expression required for C4 photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 181–207 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsley K. & Hibberd J. M. The Arabidopsis PPDK gene is transcribed from two promoters to produce differentially expressed transcripts responsible for cytosolic and plastidic proteins. Plant Mol. Biol. 62, 339–349 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal G. E. & Beevers H. Pyruvate utilization in castor-bean endosperm and other tissues. Biochem. J. 74, 409–416 (1960) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. R. & Beevers H. Gluconeogenesis from amino acids in germinating castor bean endosperm and its role in transport to the embryo. Plant Physiol. 42, 1587–1595 (1967) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. et al. Cytosolic pyruvate,orthophosphate dikinase functions in nitrogen remobilization during leaf senescence and limits individual seed growth and nitrogen content. Plant J. 62, 641–652 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. J. et al. C4 acid decarboxylases required for C4 photosynthesis are active in the mid-vein of the C3 species Arabidopsis thaliana, and are important in sugar and amino acid metabolism. Plant J. 61, 122–133 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janacek S. H. et al. Photosynthesis in cells around veins of the C3 plant Arabidopsis thaliana is important for both the shikimate pathway and leaf senescence as well as contributing to plant fitness. Plant J. 59, 329–343 (2009) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond P. J. et al. Postgerminative growth and lipid catabolism in oilseeds lacking the glyoxylate cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5669–5674 (2000) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornah J. E., Germain V., Ward J. L., Beale M. H. & Smith S. M. Lipid utilization, gluconeogenesis, and seedling growth in Arabidopsis mutants lacking the glyoxylate cycle enzyme malate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42916–42923 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo K., Le Signor C., Vandekerckhove J., Thompson R. D. & Burstin J. Proteomics of Medicago truncatula seed development establishes the time frame of diverse metabolic processes related to reserve accumulation. Plant Physiol. 133, 664–682 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Gonzalez E., Rolland F., Thevelein J. M. & Sheen J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448, 938–942 (2007) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. P. et al. Tissue-specific whole transcriptome sequencing in castor, directed at understanding triacylglycerol lipid biosynthetic pathways. PLoS ONE 7, e30100 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. W. A. et al. Glycolytic enzymes Aasociate dynamically with mitochondria in response to respiratory demand and support substrate channeling. Plant Cell 19, 3723–3738 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobr M. J. & Beevers H. Gluconeogenesis in the castor bean endosperm. I. Changes in glycolytic intermediates. Plant Physiol. 47, 48–52 (1971) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepman A. H. & Olsen L. J. Alanine aminotransferase homologs catalyze the glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase reaction in peroxisomes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 131, 215–227 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y., Dolferus R., Ismond K. P. & Good A. G. Alanine aminotransferase catalyses the breakdown of alanine after hypoxia in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 49, 1108–1121 (2007) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard-Wheeler M. C. et al. A comprehensive analysis of the NADP-Malic Enzyme gene family of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 39–51 (2005) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronconi M. A. et al. Arabidopsis NAD-Malic enzyme functions as a homodimer and heterodimer and has a major impact on nocturnal metabolism. Plant Physiol. 146, 1540–1552 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain C. J. et al. Functional evolution of C4 pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 3083–3091 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferjani A. et al. Keep an eye on PPi: the vacuolar-type H+-pyrophosphatase regulates postgerminative development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 2895–2908 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage W. E. & Leubner-Metzger G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 171, 514–523 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley H. M. et al. The pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase regulatory proteins of Arabidopsis are both bifunctional and interact with the catalytic and nucleotide-binding domains of pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase. Plant J. 68, 1070–1080 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins O., Nahal H., Foong J., Provart N. J. & Cambell M. M. Expansion and diversification of the R2R3-MYB family of transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 148, 981–993 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K. A., Ringler P., Gu L. & Shen Q. J. RNA-sequencing reveals previously unannotated protein- and microRNA-coding genes expressed in aleurone cells of rice seeds. Genomics 103, 122–134 (2014) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Y.-G. & Lin L. Transcriptional regulatory programs underlying barley germination and regulatory functions of gibberellin and abscisic acid. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 105 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon R. S. et al. Genome-wide atlas of transcription during maize development. Plant J. 66, 553–563 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M. et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301, 653–657 (2003) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M., McLilley R., Gerhardt R. & Heldt H. W. Metabolite levels in specific cells and subcellular compartments of plant leaves. Method Enzymol. 174, 518–552 (1989) . [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. P. & Leegood R. C. Purification, and phosphorylation in vivo and in vitro, of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase from cucumber cotyledons. FEBS Lett. 362, 70–74 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. & Irizarry R. A. Preprocessing of oligonucleotide array data. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 656–658 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R. & Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5116–5121 (2001) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-6, Supplementary Tables 1-4