Abstract

p53 is a Zn2+-dependent tumor suppressor inactivated in >50% of human cancers. The most common mutation, R175H, inactivates p53 by reducing its affinity for the essential zinc ion, leaving the mutant protein unable to bind the metal in the low [Zn2+]free environment of the cell. The exploratory cancer drug zinc metallochaperone-1 (ZMC1) was previously demonstrated to reactivate this and other Zn2+-binding mutants by binding Zn2+ and buffering it to a level such that Zn2+ can repopulate the defective binding site, but how it accomplishes this in the context of living cells and organisms is unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that ZMC1 increases intracellular [Zn2+]free by functioning as a Zn2+ ionophore, binding Zn2+ in the extracellular environment, diffusing across the plasma membrane, and releasing it intracellularly. It raises intracellular [Zn2+]free in cancer (TOV112D) and noncancer human embryonic kidney cell line 293 to 15.8 and 18.1 nM, respectively, with half-times of 2–3 minutes. These [Zn2+]free levels are predicted to result in ∼90% saturation of p53-R175H, thus accounting for its observed reactivation. This mechanism is supported by the X-ray crystal structure of the [Zn(ZMC1)2] complex, which demonstrates structural and chemical features consistent with those of known metal ionophores. These findings provide a physical mechanism linking zinc metallochaperone-1 in both in vitro and in vivo activities and define the remaining critical parameter necessary for developing synthetic metallochaperones for clinical use.

Introduction

Since its discovery in 1979, the tumor suppressor p53 has become one of the most universally recognized and well studied proteins in cancer biology (Levine and Oren, 2009). As many as 50% of human cancers harbor mutations in p53, and the last three decades of research have firmly established that loss of p53 function is a key event in the development of many cancers (Olivier et al., 2010). Despite the prevalence of p53 mutations in cancer and clear indications that the restoration of p53 function can be therapeutic, developing drugs with this activity has proven a challenge, as evidenced by the lack of clinically available therapies that target mutant p53 (Ventura et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2007).

One of the most common ways that p53 becomes inactivated is by mutational disruption of a critical Zn2+-binding interaction in its DNA-binding domain (DBD) (Olivier et al., 2010). Each p53 monomer coordinates a single Zn2+ via C176, C238, C242, and H179 (Cho et al., 1994). Biophysical studies have shown that removal of Zn2+ from wild-type (WT) DBD reduces the folding free energy by 30%, alters the conformation of the DNA-binding surface, and reduces sequence-specific DNA binding affinity by 10-fold, to the point where DBD can no longer discriminate between consensus and nonconsensus DNA sequences (Butler and Loh, 2003). Cellular studies have also demonstrated that zinc chelation functionally inactivates p53-WT, inhibiting its transcriptional activity and causing it to adopt a mutant-like immunologic phenotype (Méplan et al., 2000).

The most common p53 mutation in cancer, R175H, was originally classified as one such Zn2+-binding mutant by Fersht and colleagues based on its decreased folding energy, diminished DNA-binding affinity, and proximity to the Zn2+-binding site (Bullock et al., 1997, 2000). Later studies demonstrated that DBD-R175H exhibits markedly reduced Zn2+-binding affinity relative to WT (Butler and Loh, 2003). We recently measured the dissociation constant of the native DBD-R175H/Zn2+ interaction (Kd1 = 2.1 nM) and found it to be 10- to 1000-fold higher than the typical intracellular [Zn2+]free of 10−12–10−10 M (Colvin et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2014). We therefore concluded that p53-R175H is nonfunctional in the cell because it is unable to bind Zn2+ under physiologic conditions. We also measured the dissociation constant for Zn2+ binding to one or more non-native sites (Kd2 ≥ 1 μM) that are likely formed by non-native combinations of the 10 Cys and 9 His residues in DBD. Zn2+ binding to these improper ligands causes DBD to misfold and aggregate (Butler and Loh, 2007). In that same study, we investigated the mechanism of p53-R175H reactivating compound ZMC1 (Fig. 1A). We found that ZMC1 is a Zn2+ buffer in vitro, and we proposed that it functions as a synthetic metallochaperone (MC) in vivo (Yu et al., 2014).

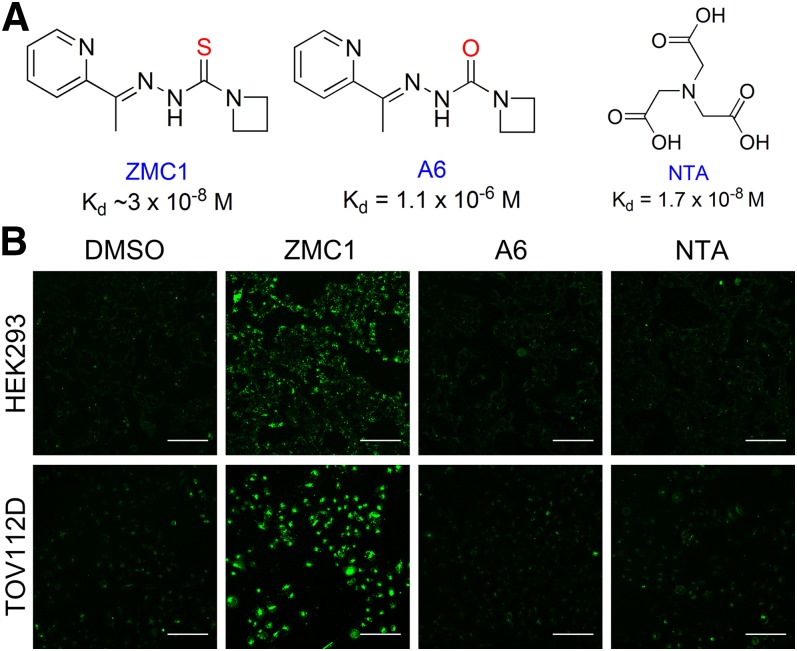

Fig. 1.

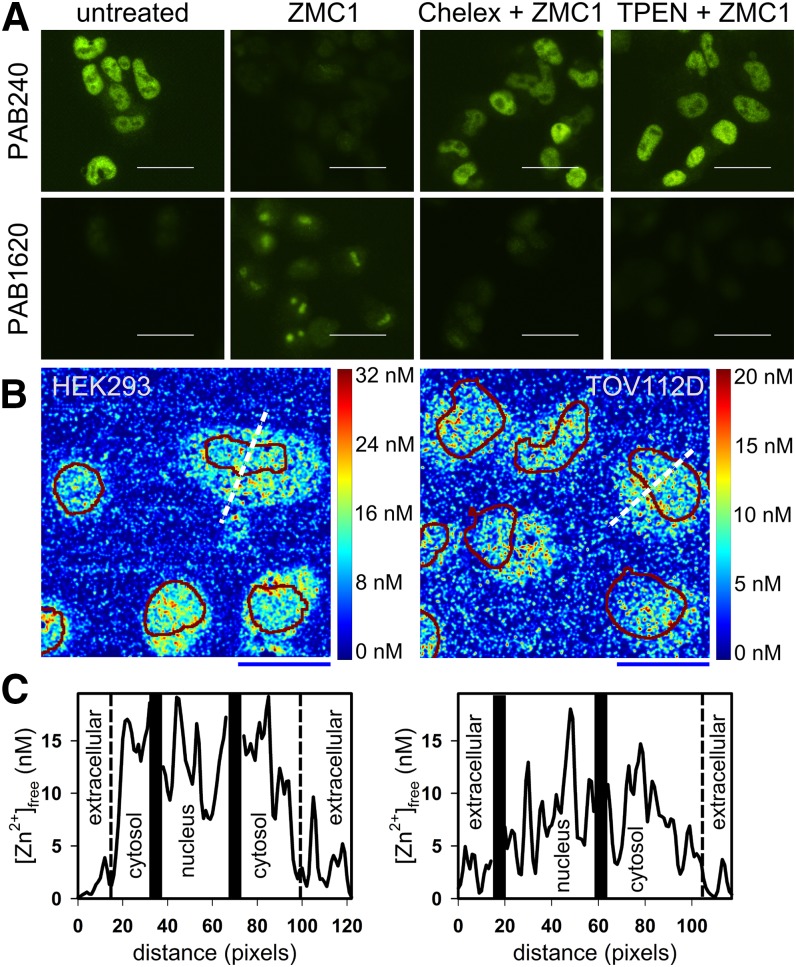

ZMC1 treatment in complete media increases intracellular [Zn2+]free. (A) Structures of compounds used in this study and their Kd values for Zn2+. Kd values shown are from Yu et al. (2014). (B) Imaging of intracellular Zn2+ level in complete media. HEK293 and TOV112D cells were loaded with FZ3-AM followed by 1 μM of the indicated treatment in 0.2% DMSO for 20 minutes at 37°C and imaged using a 20× (NA = 0.75) air objective. Scale bar = 100 μm.

By our definition, a synthetic MC must possess two activities. It must increase the free concentration of metal ion inside the cell, and then it must buffer that concentration to the range appropriate to metallate the client protein. Importantly, a synthetic MC need not bind its client but can function solely through the manipulation of free metal. Because ZMC1 binds Zn2+ with a dissociation constant (Kd,ZMC1 = 30 nM) between Kd1 and Kd2, it buffers [Zn2+]free to a level high enough to occupy the native zinc-binding site, thus restoring WT structure and function to purified DBD-R175H in vitro and p53-R175H in cells, but not so high as to populate the non-native sites and induce misfolding. This fulfills one criterion. However, evidence of the ZMC1-mediated increase in intracellular [Zn2+] required by our model has thus far been absent, and if it does occur, the source of metal and the mechanism of its increase are unknown.

Negative-control compounds A6 and nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Fig. 1A) provide some clues about the mechanism of ZMC1 (Yu et al., 2014). A6 is nearly identical in structure to ZMC1, but it binds Zn2+ 100-fold less tightly (Kd,A6 = 1.1 μM). A6 fails to rescue either purified DBD-R175H in vitro or p53-R175H in cells. By contrast, NTA binds Zn2+ with affinity similar to that of ZMC1 (Kd,NTA = 17 nM) but is polar and negatively charged. NTA restores WT structure to DBD-R175H in vitro, but it fails to activate p53-R175H in cells except at very high (millimolar) concentrations. The ineffectiveness of A6 and the discrepancy between the in vitro and cellular activities of NTA suggest that the membrane permeability of the Zn2+-bound complex might be important for MC activity.

Here we tested the hypothesis that the second defining characteristic of a synthetic MC, besides having the appropriate affinity for the metal, is its ionophore potential, that is, its ability to transport metal ions into cells (Loh, 2010). In this study, we demonstrated that micromolar concentrations of ZMC1, but not NTA or A6, increase intracellular [Zn2+]free and that this increase occurs in both cancer and noncancer cells. We showed that the source of Zn2+ is extracellular and that ZMC1 transports the metal across the plasma membrane as a transition metal-specific ionophore. We substantiated this mechanism by solving the [Zn(ZMC1)2] complex crystal structure, which demonstrates structural and chemical similarity to known metal ionophores. We quantified the resultant intracellular [Zn2+]free and found that it is in the range predicted to maximally reactivate p53-R175H, that this increase happens in minutes, and that it occurs both in the cytosol and nucleus. We also demonstrated that depletion of extracellular Zn2+ abrogates ZMC1 function. These results provide the first evidence of a Zn2+-ionophore as a p53-reactivating compound, validate the MC model of ZMC1 function, and provide critical information that will facilitate the development of Zn2+-MCs as mutant p53-targeted anticancer drugs.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Fluo-Zin (FZ3)–acetoxymethyl ester (AM), RhodZin-3 (RZ-3) (K+ salt), and cell culture media were purchased from Life Technologies Corporation (Norwalk, CT). 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). ZMC1 and A6 were obtained as previously described (Yu et al., 2014). [Zn(ZMC1)2] was synthesized and crystallized as detailed in Supplemental Methods. Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (HEK293) and TOV112D cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)1 GlutaMAX with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin under a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. All non–cell-based experiments were conducted in 50 mM Tris pH 7.2, 0.1 M NaCl at 25°C.

Liposome Import Assay.

DOPC liposomes were prepared by film rehydration and extrusion as detailed in Supplemental Methods. The size distribution was determined by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, UK) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Fluorescence measurements were taken on a Horiba Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorimeter (Horiba Scientific, Edison, NJ) in a 5 × 5-mm quartz cuvette with λex/λem = 550/572 nm for RZ-3 and 490/515 nm for calcein. Initial Zn2+ import/export was quantified by fitting the first 10–30 seconds of data after each treatment to a line and converted to units of flux using eq. 1:

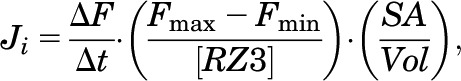

|

(1) |

where Ji is the initial flux, ΔF/Δt is the slope of the fit line, Fmax is RZ-3 fluorescence in the presence of saturating Zn2+, 1% TritonX-100, Fmin is RZ-3 fluorescence in the presence of excess EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, [RZ3] is the concentration of encapsulated RZ-3, and SA/Vol is the ratio of surface area to volume calculated assuming hollow spheres of the mean diameter determined by dynamic light scattering.

Intracellular [Zn2+]free Imaging.

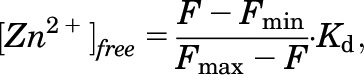

TOV112D or HEK293 cells (40,000 cells/well) were plated on either 8-well BD Falcon chambered culture slides (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA) or eight-chambered number 1.5 Nunc Laboratory-Tek II chambered cover glasses (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) treated with poly-l-lysine. After 48 hours, cells were washed 2 × 5 minutes in serum-free media and incubated with 1 μM FZ3- AM for 40 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then washed 2 × 5 minutes in either Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS)/H (−)Ca/Mg or phenol-red free DMEM + 10% FBS containing the indicated treatments and incubated for 20 minutes before imaging. For nuclear colocalization, 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 was also included. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 37°C environmental control chamber. FZ3 and Hoechst 33342 were excited at 488 nm (argon laser) and 790 nm (Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser), respectively. To determine the kinetics of fluorescence change, each background-subtracted image in the time-lapse series was integrated in ImageJ Software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and normalized to the integrated fluorescence of the first frame after treatment. For quantification of intracellular [Zn2+]free, each cell was analyzed in the treated, 50 μM pyrithione (PYR)/ZnCl2 (1:1), and 100 μM N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (TPEN) images by taking the mean fluorescence of a region of interest inside the cell subtracted by a region of interest immediately outside the cell measured in ImageJ. The [Zn2+]free for each cell was then calculated by eq. 2 (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985; Haase et al., 2006):

|

(2) |

where F, Fmax, and Fmin are fluorescence in the treatment, PYR/ZnCl2, and TPEN images, respectively, and Kd is that of FZ3 for Zn2+ (15 nM) (Gee et al., 2002). To minimize the effects of outliers, the lowest and highest 5% of cells in each series were rejected, and the remaining values were averaged. The number of cells analyzed in each trial ranged from 54 to 163. For nuclear colocalization, treated, PYR/ZnCl2-, and TPEN-treated images costained with Hoechst 33342 were aligned and each pixel subjected to eq. 2 in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The resultant images were Gaussian mean filtered and false-colored by calculated [Zn2+]free.

p53-R175H Immunofluorescence.

DMEM + 10% FBS was treated with 5 g Chelex 100 resin per 100 ml of media for 1 hour with gentle shaking. The media was then decanted and filtered through a 0.2-μm sterile filter. TOV112D cells were then incubated with 1 μM ZMC1 in untreated media, Chelex-treated media, or media + 10 μM TPEN at 37°C for 2 hours, fixed, and stained with PAB240 and PAB1640 as previously described (Yu et al., 2012).

Results

ZMC1 is a Zn2+ Ionophore.

We evaluated the ability of ZMC1, NTA (Zn2+-binding homolog), and A6 (structural homolog) to increase intracellular [Zn2+]free by treating cells with the fluorescent Zn2+ indicator FZ3-AM in complete media and imaging them using confocal microscopy (Fig. 1B) (Gibon et al., 2011). In both HEK293 (non-cancer, p53-WT) and TOV112D (ovarian cancer, p53-R175H) cells, ZMC1 increased intracellular [Zn2+]free as indicated by increased fluorescence, but NTA and A6 did not. This result is consistent with the MC model for ZMC1 function and explains the inability of NTA and A6 to rescue p53-R175H at micromolar concentrations.

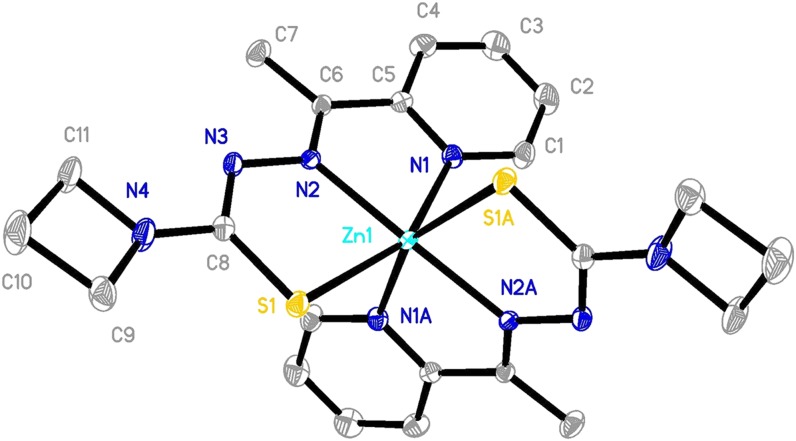

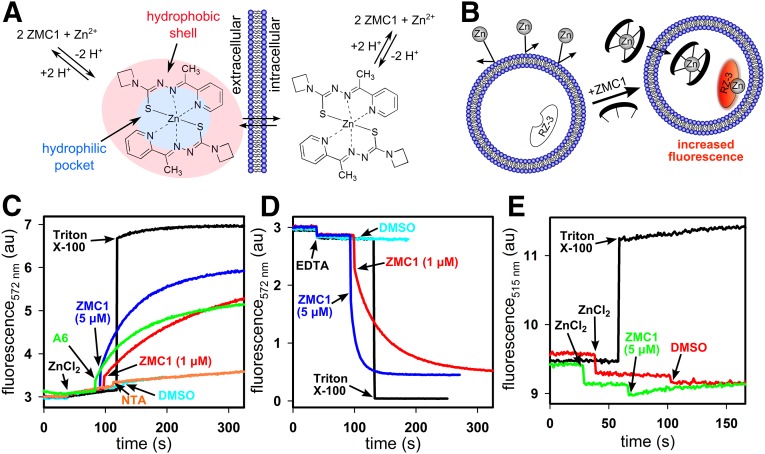

To provide physical insight into the mechanism by which ZMC1 increases intracellular [Zn2+]free, we solved the X-ray crystal structure of the [Zn(ZMC1)2] complex (Fig. 2). Consistent with previous results, the stoichiometry is 2:1 (Yu et al., 2014). The thiocarbonyl sulfur anion, thiocarbonyl β-nitrogen, and pyridinyl nitrogen from two deprotonated ZMC1 molecules encapsulate the Zn2+ and generate a neutral complex. The chemical preparation of this zinc-ZMC1 complex involved treatment of a mixture of 1.0 equivalent of ZMC1 and 0.5 equivalents of ZnCl2 in heated ethanol with excess triethylamine, thus enolizing the thiosemicarbazone to generate thiolate and form the neutral [Zn(ZMC1)2] complex. This structure bears some similarity to known ionophores (e.g., valinomycin and crown ethers) with the zinc cradled in a hydrophilic pocket inside a hydrophobic shell (Fig. 3A). We therefore tested whether ZMC1 is an ionophore by encapsulating the fluorescent Zn2+ indicator RZ-3 inside 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) liposomes and assaying the ability of our compounds to transport Zn2+ in and out by monitoring fluorescence (Fig. 3, B–D; Table 1). We noted that liposomes copurified with 4.3 μM internal Zn2+, allowing for determination of both import and export rates. Zn2+ alone was unable to permeate the liposomal membrane as indicated by the lack of RZ-3 fluorescence increase (Fig. 3C). The addition of ZMC1 caused a dose-dependent increase in the rate of RZ-3 fluorescence increase, indicating that ZMC1 can facilitate the transport of Zn2+ into the liposomes, which is consistent with our ionophore hypothesis.

Fig. 2.

Molecular structure of [Zn(ZMC1)2] by X-ray crystallography. C = gray, N = dark blue, S = yellow, Zn = aqua blue. Data are available in Supplemental Tables 1–6. X-ray data show significant single bond character of the C-S bond (1.726 Å) to support enolization of ZMC1.

Fig. 3.

ZMC1 is an ionophore in a liposomal model system. (A) Diagram of ZMC1-mediated Zn2+ transport. Zn2+ combines with two enolizable ZMC1 molecules to generate an overall neutral complex that moves across the membrane. After crossing, the complex dissociates to release two ZMC1 molecules and free Zn2+. (B) Schematic of the liposomal system. Charges are omitted for clarity. (C and D) Zn2+ import (C) and export (D) kinetics measured by DOPC-encapsulated RZ-3 fluorescence. RZ-3 was encapsulated at 10 μM. Arrows indicate treatment addition. TritonX-100 and DMSO were positive and vehicle controls, respectively. Concentrations were 10 μM ZnCl2, 100 μM EDTA, 5 μM NTA, 5 μM A6, 1% TritonX-100, 0.2% DMSO, and 1 or 5 μM ZMC1. Quantification is shown in Table 1. (E) Calcein leakage assay. Calcein (10 mM) was DOPC-encapsulated and subjected to the indicated treatments. Arrows indicate treatment addition. TritonX-100 and DMSO were positive and vehicle controls, respectively. Concentrations as in (C) and (D).

TABLE 1.

Initial Zn2+ ion flux into DOPC liposomes

Fluxes were calculated from linear fits of initial fluorescence changes in the time-courses represented in Fig. 2 using eq. 1. Values are mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 3).

| Sample | Ji (mol m−2 s−1) (10−14) |

|---|---|

| ZnCl2 only (10 μM) | 8.90 ± 0.94 |

| ZnCl2 + DMSO (0.2%) | 6.81 ± 0.68 |

| ZnCl2 + ZMC1 (1 μM) | 52.3 ± 1.2 |

| ZnCl2 + ZMC1 (5 μM) | 135 ± 5 |

| ZnCl2 + NTA (5 μM) | 4.52 ± 1.22 |

| ZnCl2 + A6 (5 μM) | 71.3 ± 2.9 |

| EDTA Only (100 μM) | −0.69 ± 0.67 |

| EDTA + DMSO (0.2%) | −0.53 ± 1.43 |

| EDTA + ZMC1 (1 μM) | −131 ± 2 |

| EDTA + ZMC1 (5 μM) | −199 ± 86 |

Of the two control compounds, A6 shuttled Zn2+ into the liposomes, but NTA did not. Together with Fig. 1B, these results illustrate the requirements of an effective synthetic MC. NTA binds Zn2+ with an affinity similar to that of ZMC1, but it cannot cross either liposomal or cellular membranes, likely because it possesses negative charges. A6, on the other hand, lacks charges and is similar in structure to ZMC1, but it binds Zn2+ weakly (Kd,A6 = 1.1 μM). It can function as an ionophore in conditions of the liposome experiments where external [Zn2+]free was 10 μM. In complete media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), however, Zn2+-binding proteins from the serum (e.g., albumin) necessarily compete for Zn2+ with any putative MC, making the effective [Zn2+]free much lower than [Zn2+]total (see Discussion) (Moran et al., 2012). A6 therefore likely does not increase intracellular [Zn2+]free in culture because Kd,A6 is greater than extracellular [Zn2+]free. Thus, both an appropriate Zn2+ Kd and ionophore activity are necessary for ZMC1 activity.

We hypothesized that ZMC1 should be able to traverse lipid bilayers as a free compound and that this property might be important for its biologic activity. For example, if it crosses membranes only as the zinc-bound species, then the accumulation of free ZMC1 in cells would limit the increase in intracellular [Zn2+]free. To test this hypothesis, we reversed the [Zn2+]free gradient by adding a large excess of metal ion chelator EDTA to the solution outside the liposomes and monitored the fluorescence in the presence and absence of ZMC1 (Fig. 3D). EDTA alone did not cause a significant decrease in RZ-3 fluorescence as the liposomal membranes are impermeable to EDTA. After subsequent addition of ZMC1, there was a time-dependent decrease in RZ-3 fluorescence. This result indicates that free ZMC1 crossed the liposomal membranes, bound internal Zn2+, and transported it back outside the liposome, where the metal was then bound by the much stronger chelator EDTA. Thus, ZMC1 can cross DOPC bilayers both as free drug and as the [Zn(ZMC1)2] complex. Mechanistically, Zn2+ is complexed by two deprotonated ZMC1 molecules and transported across membranes as an uncharged species. After crossing, the ZMC1 molecules are “reprotonated” to regenerate neutral ZMC1 and release the bound Zn2+ (Fig. 3A).

To ensure that our fluorescence results were due to Zn2+ transport and not to nonspecific disruption of liposomal membranes, we performed a liposomal leakage assay using the self-quenching fluorophore calcein (Fig. 3E) (Han, 2005). When calcein is encapsulated at concentrations above 4 mM, its fluorescence is decreased via self-quenching (Hamann et al., 2002). Leakage is detected by a fluorescence increase as the dye dilutes and its fluorescence dequenches. At the highest concentrations of ZMC1 and ZnCl2 used, we did not detect a significant fluorescence increase. Disruption of liposomes can also be detected by alteration of their size distribution. The size distribution of liposomes treated with the highest concentrations of ZnCl2 and ZMC1 was identical to that of untreated liposomes (Supplemental Fig. 1). Together, these data indicate the liposomal membranes remained intact on ZMC1 treatment, and therefore the RZ-3 fluorescence changes are attributable only to specific Zn2+ transport.

Characterization of ZMC1-Mediated Zn2+ Transport in Live Cells.

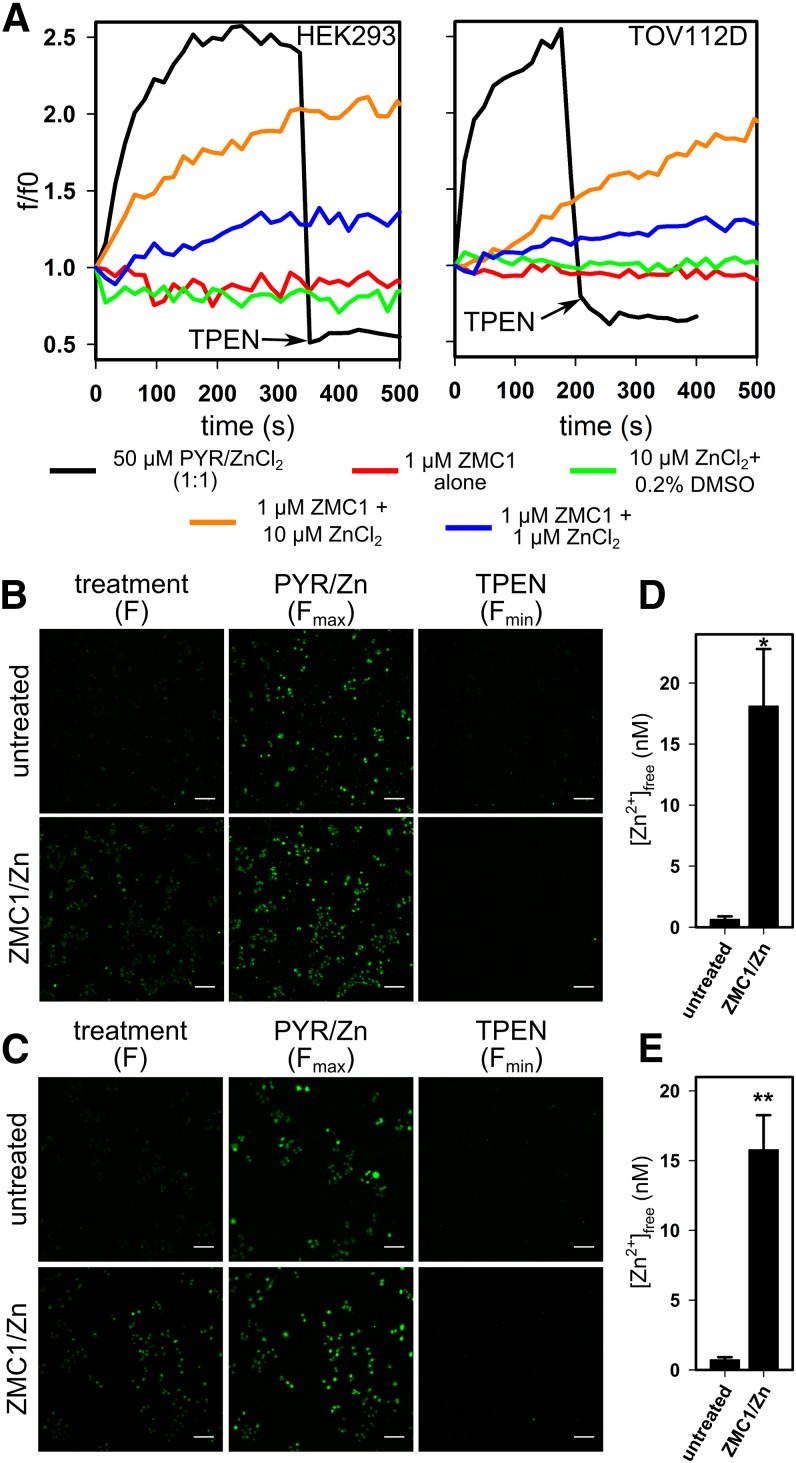

To extend our investigation of ZMC1 as an ionophore to living systems, we quantified ZMC1-mediated Zn2+ transport in cells. We first measured the kinetics of intracellular [Zn2+]free increase by loading HEK293 and TOV112D cells with FZ3-AM, treating the cells with ZMC1 and ZnCl2, and monitoring fluorescence by time-lapse microscopy (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Movies 1–10). To minimize the potential for Zn2+ contamination and contributions from poorly defined elements in complete media (e.g., FBS), cells were treated and imaged in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free EBSS supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg). Excess ZnCl2 with the Zn2+ ionophore PYR was used as a positive control (Haase et al., 2006). Excess membrane-permeable Zn2+ chelator TPEN was used as a negative control (Bozym et al., 2006). When treated with ZnCl2 alone or ZMC1 alone, neither cell type showed an increase in intracellular [Zn2+]free. When treated with both ZMC1 and ZnCl2, both cell lines showed a time-dependent increase at two different ZnCl2 concentrations, demonstrating that both ZMC1 and extracellular Zn2+ are required. When the fluorescence increases were fit to first-order exponentials, both concentrations of ZnCl2 yielded identical half-lives in their respective cell types, which we combine to report t1/2 (HEK293) = 124 ± 20 seconds and t1/2 (TOV112D) = 156 ± 50 seconds (mean ± S.D., n = 4).

Fig. 4.

Quantification of ZMC1-mediated intracellular [Zn2+]free increase. (A) Representative kinetic traces of intracellular [Zn2+] increase in HEK293 and TOV112D cells. Cells were loaded with FZ3-AM and exchanged into EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg. Cells were then given the indicated treatment and monitored by time-lapse microscopy. Results are shown as total fluorescence relative to the first frame after treatment (shown as t = 0). PYR/ZnCl2 and DMSO were used as positive and loading controls, respectively. TPEN (100 μM) was added at the arrow as a negative control. Representative videos are included as Supplemental Movies 1–10). (B and C) Representative images of HEK293 (B) or TOV112D (C) cells loaded with FZ3-AM either untreated or treated with 1 μM ZMC1/0.5 μM ZnCl2 in EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg for 20 minutes, followed by 50 μM PYR/50 μM ZnCl2 and 100 μM TPEN. Images were taken using a 10× (NA = 0.3) air objective. Scale bar = 100 μm (D and E) Quantification of images represented in (B) and (C), respectively, according to eq. 2. Results are mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *P < 0.003; **P < 0.0005

We then quantified the steady-state intracellular [Zn2+]free of both cell types after treatment with the 2:1 ratio of ZMC1:ZnCl2 judged to be optimal in our previous article (Fig. 4B-E) (Yu et al., 2014). Cells were again loaded with FZ3-AM, treated with 1 μM ZMC1 and 0.5 μM ZnCl2 in EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg, and imaged as described. To normalize for differential dye loading, cells were then sequentially treated with excess PYR/ZnCl2, imaged, treated with TPEN, and imaged again. PYR/ZnCl2 and TPEN served to saturate and apoize the intracellular FZ3, respectively (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985; Haase et al., 2006). In the absence of drug, we measured intracellular [Zn2+]free of 0.69 ± 0.25 nM for HEK293 cells and 0.71 ± 0.19 nM for TOV112D cells. These values reflect the lower limit of detection by FZ3-AM and are likely overestimates. On treatment with ZMC1 and ZnCl2, intracellular [Zn2+]free increased to 18.1 ± 4.7 nM for HEK293 cells and 15.8 ± 2.5 nM for TOV112D cells. These concentrations are theoretically sufficient to reactivate ∼90% of p53-R175H based on the Kd1 value of 2.1 nM measured for DBD-R175H (Yu et al., 2014).

Extracellular Zn2+ Is Necessary for ZMC1 Function in Cells.

If ZMC1 is a Zn2+ ionophore and the source of the Zn2+ it delivers is extracellular, as suggested by our kinetic experiments in Zn2+-free media, then depleting the extracellular Zn2+ from complete media should inhibit ZMC1’s function. To test this prediction, we took advantage of ZMC1’s known ability to induce a conformational change in p53-R175H using the conformation specific antibodies PAB240 and PAB1620 in complete media with and without Zn2+ chelators (Fig. 5A) (Yu et al., 2012). Consistent with previous results, ZMC1 treatment shifted the p53-R175H immunophenotype from misfolded (PAB240) to WT-like (PAB1620) in TOV112D cells in untreated media (Yu et al., 2012). This shift disappeared when the media was pretreated with metal-ion chelating resin Chelex. Antibody shift was also reduced when the media were treated with the Zn2+-selective chelator TPEN. These data confirm the requirement for an extracellular source of ions for ZMC1 function and that the likely identity of that ion is Zn2+.

Fig. 5.

Extracellular Zn2+ is required for ZMC1-induced p53 conformation change. (A) Immunophenotype analysis of R175H-p53 in TOV112D cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM ZMC1 in complete media, Chelex-treated media, and TPEN-treated media for 2 hours, fixed, and assayed via immunofluorescence microscopy with the indicated primary antibodies. Scale bars = 100 μm. (B) ZMC1/ZnCl2-treated HE293 (left) and TOV112D (right) cells false-colored by [Zn2+]free. Cells were loaded with FZ3-AM and treated with 1 μM ZMC1/0.5 μM ZnCl2 in EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg for 20 minutes. [Zn2+]free was calculated from images of the treatment, 50 μM PYR/50 μM ZnCl2, and 100 μM TPEN according to eq. 2. Outlines of nuclei from Hoechst 33342 costaining shown in dark red. Images were taken using a 40× (NA = 1.3) oil immersion objective. Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) [Zn2+]free profiles indicated by the white dotted line in corresponding images in (B).

Because most mutant p53 staining occurs in the nucleus (Fig. 5A), we hypothesized that ZMC1 increases [Zn2+]free in the nucleus as well as the cytosol. As a test, we loaded HEK293 and TOV112D cells with FZ3-AM, treated with 2:1 ZMC1/ZnCl2 in EBSS/H (−)Ca/Mg for 20 minutes, and costained the nuclei with Hoechst 33342. To account for differential dye loading in the cytosol, nucleus, endosomes, and other subcellular compartments, we sequentially imaged the cells after ZMC1/ZnCl2, PYR/ZnCl2, and TPEN treatment; calculated the [Zn2+]free profiles; and overlaid the outlines of the nuclei (Fig. 5B-C). [Zn2+]free was relatively homogeneous throughout the cells in both cell types; no significant differences between the cytosol and nuclei were observed.

Because thiosemicarbazones like ZMC1 are known to interact with a number of metals involved in a variety of biologic processes (e.g., Fe2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ca2+, and Mg2+), we wanted to evaluate ZMC1’s potential to interact with other biologically relevant ions (Yu et al., 2009). To this end, we measured absorbance spectra of ZMC1 in the presence of the two most biologically prevalent group II metals (Ca2+ and Mg2+) and the three most biologically prevalent transition metals (Fe2+/3+, Zn2+, and Cu2+) (Supplemental Fig. 2). Neither of the group II metals caused a shift in absorbance. By contrast, all three transition metals produced a shift, indicating that ZMC1 interacts with Cu2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ in addition to Zn2+. This finding is significant for two reasons. First, we previously observed that apoptosis induced by ZMC1 was dependent on reactive oxygen species generation, which we hypothesized was a result of Fenton chemistry facilitated by ZMC1 interacting with redox-active metals (Yu et al., 2014). Both iron and copper are redox-active, supporting that hypothesis. Second, the lack of an interaction between ZMC1 and Ca2+ and Mg2+ indicates that Ca2+ and Mg2+ homeostasis and signaling are unlikely to be perturbed by ZMC1.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that ZMC1 increases intracellular [Zn2+]free by shuttling extracellular Zn2+ ions across the plasma membrane, thus providing a physical mechanism linking ZMC1’s ability to buffer [Zn2+] in vitro and its ability to reactivate p53-R175H (and other Zn2+-binding mutants) in vivo (Yu et al., 2012, 2014). We can now define two properties that are necessary and sufficient for a synthetic MC to rescue p53-R175H in cells. The first is that the compound must bind Zn2+ with an affinity greater than that of the non-native site(s) on p53 and that of albumin in serum (Kd,albumin ∼10−7 M; see later), but with an affinity less than that of the native zinc-binding site on p53-R175H (Kd1 = 2.1 nM) (Masuoka et al., 1993; Yu et al., 2014). The second property is that the compound must be able to transport Zn2+ across the plasma membrane.

The preceding requirements explain why NTA and A6 fail as synthetic MC drugs. NTA and ZMC1 bind Zn2+ with comparable affinities and they both reactivate Zn2+-free p53 DNA-binding domain-R175H in vitro, but NTA does not elevate intracellular [Zn2+]free in cells, at least when dosed at micromolar concentrations (Fig. 1B) (Yu et al., 2014). Like EDTA, NTA possesses multiple negative charges that render it impermeable to cells. By contrast, A6 fails to restore function to Zn2+-free p53 DNA-binding domain-R175H in vitro because it binds Zn2+ too weakly to protect against metal-induced misfolding (Yu et al., 2014). A6 fails to reactivate p53-R175H in cells for a related but different reason. The uncharged A6 molecule can deliver Zn2+ across biologic membranes, but, owing to its poor Zn2+ affinity (Kd,A6 = 1.1 μM), it does so only at high [Zn2+]free (e.g., 10 μM; Fig. 2). In vivo, serum [Zn2+]total is typically 8.5–23.6 μM, but nearly all is bound to albumin. The combination of ∼0.6 mM albumin and Kd,albumin ∼10−7 M ensures that [Zn2+]free is significantly lower than Kd,A6 (Masuoka et al., 1993; Ohyoshi et al., 1999; Moran et al., 2012). [Zn2+]free in culture media is similarly low because the vast majority of Zn2+ comes from supplemented serum and is also mostly bound to albumin (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/life-science/cell-culture/learning-center/media-expert/zinc.html). Because A6 cannot compete with albumin for Zn2+ (Kd,A6 is 10-fold higher than Kd,albumin), it follows that A6 cannot bind Zn2+ in serum or complete media. Thus, we estimate that an effective MC drug should have a Zn2+ Kd in the range 10−9 to 10−7 M, defined at either end by Kd1 of p53-R175H and Kd,albumin, respectively.

Whereas ZMC1 functions primarily through its interaction with Zn2+, we show that it can also interact with redox-active transition metals Cu2+ and Fe2+/3+. As previously demonstrated, interactions with one or both metals is likely required for ZMC1-induced apoptosis via reactive oxygen species generation (Yu et al., 2014). However, nearly all iron and copper in serum is bound in high-affinity complexes with transferrin (Kd < 10−19 M) for Fe2+/3+ and either ceruloplasmin (95%) or albumin (Kd < 10−11 M) for Cu2+ (Neumann and Sass-Kortsak, 1967; Aisen et al., 1978; Masuoka et al., 1993). Because the resulting concentrations of free iron and copper in serum are expected to be extremely low, and because ZMC1 cannot compete with transferrin and cerulopasmin for metal binding, it is unlikely that ZMC1 will perturb iron or copper homeostasis by transporting these metals into cells. This view is substantiated by the prior observation that ZMC1 is relatively nontoxic to cells and mice lacking mutant p53 (Yu et al., 2014).

It is important to note that the pharmacophore of the ZMC1-Zn complex is the Zn2+ ion, with ZMC1 serving exclusively as a metal transport and buffering system. This unusual relationship presents a number of considerations not encountered in traditional pharmacotherapy. A major advantage of synthetic MCs is that they obviate the major hurdle associated with developing conventional targeted chemotherapy drugs: the need to identify compounds that bind to target proteins with high affinity and specificity. Since synthetic MCs need not interact directly with their clients, their structures can vary drastically, provided they maintain their ability to bind and transport Zn2+ into the cell. Indeed, Garufi et al. (2013) recently demonstrated the ability of a bipyridine-Zn2+-curcumin complex to reactivate mutant p53-R175H as well as cross the blood-brain barrier. Although the structure is unrelated to ZMC1, it is possible that it functions via a similar mechanism. MCs may allow a level of design freedom not possible with conventional drugs, as structures can be varied to optimize pharmacologic characteristics (e.g., delivery, toxicity, clearance) without regard to maintaining affinity for p53. A second consideration is that, because MC-mediated p53 restoration is caused by increasing intracellular [Zn2+]free to an optimum level, coadministration of zinc supplements or preforming the Zn2+ complex may increase the effectiveness of MCs if the [Zn2+] in the serum is insufficient to reach this target. Therefore, defining the optimal serum [Zn2+], and the most efficient method to maintain that level, may enhance the therapeutic potential of MCs.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- AM

acetoxymethyl ester

- DBD

p53 DNA-binding domain

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- EBSS

Earle’s balanced salt solution

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FZ3

FluoZin-3

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cell line 293

- MC

metallochaperone

- NTA

nitrilotriacetic acid

- PYR

pyrithione

- RZ-3

RhodZin-3

- TPEN

N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine

- WT

wild-type

- ZMC1

zinc metallochaperone-1

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Blanden, Yu, Wolfe, Augeri, O’Dell, Olson, Kimball, Movileanu, Carpizo, Loh.

Conducted experiments: Blanden, Yu, Wolfe, Gilleran, Augeri, Emge.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Gilleran, Augeri, Emge.

Performed data analysis: Blanden, Yu, Gilleran, Augeri, Kimball, Emge, Loh.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Blanden, Yu, Augeri, Loh.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant K08-CA172676-02], the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Harrington Discovery Institute, and the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research to D.R.C., the Carol M. Baldwin Breast Cancer Research Award to S.N.L., and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01-GM088403] to L.M.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.asetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.asetjournals.org.

References

- Aisen P, Leibman A, Zweier J. (1978) Stoichiometric and site characteristics of the binding of iron to human transferrin. J Biol Chem 253:1930–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozym RA, Thompson RB, Stoddard AK, Fierke CA. (2006) Measuring picomolar intracellular exchangeable zinc in PC-12 cells using a ratiometric fluorescence biosensor. ACS Chem Biol 1:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Henckel J, DeDecker BS, Johnson CM, Nikolova PV, Proctor MR, Lane DP, Fersht AR. (1997) Thermodynamic stability of wild-type and mutant p53 core domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:14338–14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Henckel J, Fersht AR. (2000) Quantitative analysis of residual folding and DNA binding in mutant p53 core domain: definition of mutant states for rescue in cancer therapy. Oncogene 19:1245–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JS, Loh SN. (2003) Structure, function, and aggregation of the zinc-free form of the p53 DNA binding domain. Biochemistry 42:2396–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JS, Loh SN. (2007) Zn(2+)-dependent misfolding of the p53 DNA binding domain. Biochemistry 46:2630–2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. (1994) Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265:346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin RA, Holmes WR, Fontaine CP, Maret W. (2010) Cytosolic zinc buffering and muffling: their role in intracellular zinc homeostasis. Metallomics 2:306–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garufi A, Trisciuoglio D, Porru M, Leonetti C, Stoppacciaro A, D’Orazi V, Avantaggiati M, Crispini A, Pucci D, D’Orazi G. (2013) A fluorescent curcumin-based Zn(II)-complex reactivates mutant (R175H and R273H) p53 in cancer cells (Abstract). J Exp Clin Cancer Res 32:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KR, Zhou Z-L, Ton-That D, Sensi SL, Weiss JH. (2002) Measuring zinc in living cells. A new generation of sensitive and selective fluorescent probes. Cell Calcium 31:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon J, Tu P, Bohic S, Richaud P, Arnaud J, Zhu M, Boulay G, Bouron A. (2011) The over-expression of TRPC6 channels in HEK-293 cells favours the intracellular accumulation of zinc. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:2807–2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase H, Hebel S, Engelhardt G, Rink L. (2006) Flow cytometric measurement of labile zinc in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Anal Biochem 352:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Kiilgaard JF, Litman T, Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Winther BR, Zeuthen T. (2002) Measurement of cell volume changes by fluorescence self-quenching. J Fluoresc 12:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Han HD, Kim TW, Shin BC, Choi HS. (2005) Release of calcein from temperature-sensitive liposomes in a poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogel. Macromol Res 13:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ, Oren M. (2009) The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer 9:749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh SN. (2010) The missing zinc: p53 misfolding and cancer. Metallomics 2:442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka J, Hegenauer J, Van Dyke BR, Saltman P. (1993) Intrinsic stoichiometric equilibrium constants for the binding of zinc(II) and copper(II) to the high affinity site of serum albumin. J Biol Chem 268:21533–21537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méplan C, Richard MJ, Hainaut P. (2000) Metalloregulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53: zinc mediates the renaturation of p53 after exposure to metal chelators in vitro and in intact cells. Oncogene 19:5227–5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran VH, Stammers A-L, Medina MW, Patel S, Dykes F, Souverein OW, Dullemeijer C, Pérez-Rodrigo C, Serra-Majem L, Nissensohn M, et al. (2012) The relationship between zinc intake and serum/plasma zinc concentration in children: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Nutrients 4:841–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PZ, Sass-Kortsak A. (1967) The state of copper in human serum: evidence for an amino acid-bound fraction. J Clin Invest 46:646–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyoshi E, Hamada Y, Nakata K, Kohata S. (1999) The interaction between human and bovine serum albumin and zinc studied by a competitive spectrophotometry. J Inorg Biochem 75:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. (2010) TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use (Abstract). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T. (2007) Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 445:661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. (2007) Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 445:656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Blanden AR, Narayanan S, Jayakumar L, Lubin D, Augeri D, Kimball SD, Loh SN, Carpizo DR. (2014) Small molecule restoration of wildtype structure and function of mutant p53 using a novel zinc-metallochaperone based mechanism. Oncotarget 5:8879–8892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Vazquez A, Levine AJ, Carpizo DR. (2012) Allele-specific p53 mutant reactivation. Cancer Cell 21:614–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Kalinowski DS, Kovacevic Z, Siafakas AR, Jansson PJ, Stefani C, Lovejoy DB, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. (2009) Thiosemicarbazones from the old to new: iron chelators that are more than just ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. J Med Chem 52:5271–5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.