Abstract

Training that focuses on strength, balance, and endurance, the so-called combined exercise, can enhance physical function, including gait, according to a literature review. However, the effects of combined exercise on improving gait variability are limited. The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of 12 weeks of combined exercise comprised of resistance, endurance, and balance training on gait performance in older adults. Twenty-nine community-dwelling older adults were recruited and assigned to either the experimental group (n = 17) or the control group (n = 12). The 12-week intervention was a combined exercise program at 1 h per day and 3 days per week. The participants received an assessment for both a 6-min walk and gait during both habitual walking and fast walking conditions at pre-intervention and after 8 and 12 weeks of exercise. The 6-min walk was used to assess gait endurance. GAITRite was used to evaluate gait. An analysis of covariance with the pretest score as the covariate was used to determine the difference in each dependent variable between groups. The level of significance was set as p less than 0.05. Our results showed significant between-group effects in the 6-min walk and velocity, stride time, and stride length in both conditions after 8 weeks of exercise and significant between-group effects in the 6-min walk test and all selected gait parameters in both conditions after 12 weeks of exercise. Our findings demonstrate that a 12-week combined exercise program may positively affect gait endurance and gait performance including gait variability in habitual walking and fast walking conditions among older adults. The current study provides important evidence of short-term combined exercise effects on improvements in gait performance.

Keywords: Exercise, Intervention, Gait performance, Gait variability, Elderly

Introduction

A slower walking speed is common among older adults (Alexander 1996). Older people may walk slowly because of decreased strength or flexibility (DeVita and Hortobagyi 2000; Kerrigan et al. 2001). A reduced gait speed has been consistently reported to be predictive of falls among older adults (Cooper et al. 2011; Verghese et al. 2009). Increased gait variability is another common finding in older adults (Kang and Dingwell 2008), which refers to the natural stride-to-stride fluctuations that are present during walking. Gait variability has been described as another predictor of declines in mobility and falls (Brach et al. 2005; Brach et al. 2007; Hausdorff et al. 2001b). Variability in gait characteristics, specifically stride time and swing time, has been shown to be predictive of falls when gait speed failed to distinguish between community-dwelling older persons who had fallen and those who had not fallen (Hausdorff et al. 1997). Previous findings reported that step time variability and step length variability are greater in older adults in the general population and not just in those with disease (Hausdorff et al. 1998; Syddall et al. 2010). Thus, a suitable intervention should be provided to counteract the reduced gait speed and increased gait variability in older adults.

Exercise is a key intervention for improving physical function in older adults. The benefits of exercise in either delaying physical dependence or improving physical performance in the elderly population have long been recognized (American College of Sports Medicine et al. 2009; Gates et al. 2008; Toto et al. 2012). The American College of Sports Medicine recommends aerobic, muscle strengthening, and flexibility exercises for older people (American College of Sports Medicine 2014). A previous meta-analysis reported that aerobic training, flexibility, balance, and relaxation exercises contributed to improve habitual gait speed without a significant effect on fast gait speed (Lopopolo et al. 2006). These authors speculated that the lack of positive results in fast gait speed may be due to inadequate intensity and/or dosage. Subsequently, a randomized controlled study showed that a 48-week combined exercise program was effective in improving maximal walking time and maximal step length (Park et al. 2008). However, poor long-term adherence to these increased activity levels in older adults is another possible reason for insignificant results. Moreover, little work has been done to investigate the effects of combined exercise on gait variability. Therefore, we designed a short-term combined exercise program with high intensity and high dosage. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a 12-week intensive, combined exercise program consisting of resistance, endurance, and balance training on gait performance, especially the gait variability, in older adults.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from local public health centers in Taipei. All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age greater than 65 years and (2) ability to walk outdoors independently without devices. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unstable medical conditions interfering with participation in the study and (2) diagnosis of dementia, psychosis, neurological disease, or depression. A total of 33 participants were recruited and participated in the study.

Procedure

This study is a nonrandomized clinical controlled trial. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital. The purpose, nature, and potential risks of the experiments were fully explained to the participants, and all participants gave written, informed consent before participating in the study. The participants were allocated into either the experimental or control group according to their choice to increase compliance. The experimental group received a combined exercise program of 1 h at three times a week for 12 weeks, whereas the control group attended six education classes regarding health during the 12-week period. Outcome measurements were performed prior to the intervention and after 8 and 12 weeks of exercise. Measurements included a 6-min walk test and gait performance in both habitual walking and fast walking conditions. Information about age, gender, height, weight, and medical status were obtained from interviews.

Intervention

Participants in the experimental group underwent combined exercise for 1 h per day at 3 days every week for 12 weeks. The exercise program was based on suggested exercise programs for elderly populations from the American College of Sports Medicine and comprised 20 min of resistance training, 20 min of endurance training, and 20 min of balance training (American College of Sports Medicine 2014). During the exercise period, a qualified physical therapist provided guidance and assistance for each participant. The resistance training targeted the lower extremity muscles and involved hip flexion, hip extension, knee flexion, ankle plantarflexion, bodyweight squats in standing, knee extension in sitting, and ankle dorsiflexion in supine. The maximal voluntary isometric contraction of each muscle group was measured using a handheld dynamometer (PowerTrack II; JTech Medical, USA). Training intensity began from 50 % maximal voluntary contraction for ten repetitions and then progressively increased to 75–80 % maximal voluntary contraction. There was a 5-min stretching exercise before and after resistance training to prevent muscle soreness and injury (Jamtvedt et al. 2010). The endurance training program was a sequence of whole-body activities, including a 5-min warm-up, 20 min of endurance training, and a 5-min cool-down exercise. Stepping, marching, brisk walking, and spinning a hula hoop with upper limb movements were included in the endurance exercise. The training intensity was set at 70–75 % maximal heart rate (220−age), and ratings of perceived exertion were recorded during the training period so as to modify the dose of the intervention. The balance exercise program involved static and dynamic balance training. Static balance training included standing on the ground with different materials and bases of support, forward reaching, and a single stance. Dynamic balance training included straight walking, sideway walking, backward walking, and figure 8 walking.

Participants in the control group attended six education classes regarding health for 1 h per day at 1 day every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. The class was provided information regarding common exercises for the elderly, individualized exercise programs, and prevention of exercise injuries.

Measurements

Six-minute walk test

The 6-min walk test was used to evaluate functional status and exercise endurance (Bautmans et al. 2004; Enright et al. 2003). This test was conducted along a 30-m hallway marked in 1-m increments. A line was made at each end of the walkway to indicate where the person was to turn. Participants walked alone without any assistive device during the test unless the evaluator felt that they were unsafe. Participants were instructed to try to cover as much distance as possible within 6 min without running. Participants were allowed to rest or stop when necessary. The reliability of the 6-min walk test in healthy elderly persons is high (Steffen et al. 2002).

Gait performance

The GAITRite system (GAITRite, CIR Systems Inc., USA) was used to evaluate gait performance. It comprises a portable carpet walkway (length 5 m, width 0.9 m) with 16,128 sensors embedded within its length. The sampling rate of the system is 80 Hz. When the subject walks over the carpet, the sensors under the carpet collect data on spatial and temporal gait parameters. The validity and reliability of gait performance in the elderly had been well established (Brach et al. 2008; Menz et al. 2004; Trombetti et al. 2011).

Gait was evaluated during walking at both habitual and fast speeds. Participants were instructed to walk at a comfortable pace for three trials and then to walk at a fastest pace for three trials. The time between trials was 1 min. Data were averaged from the three trials at both the habitual and fast speeds. Gait parameters of interest were velocity (cm/s), stride time (s), stride length (cm), stride time variability (%), and stride length variability (%). The coefficient of variation (CV) was used to assess the variability, stride-to-stride consistency, and rhythmicity of gait (Hausdorff et al. 2001b). Lower values reflected a more consistent gait pattern. The formula of CV given as a percentage is as follows: standard deviation/mean ×100 %.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on gait variability, which is the primary outcome in this study. The sample size was determined using G*power based on an effect size f of 0.25, an alpha level of 5 %, 80 % power, and an ANOVA model with repeated measures. A total sample size of 28 participants was indicated.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS 19.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables, and distributions of variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Intergroup differences among baseline characteristics were evaluated using an independent t test or chi-square analysis. An analysis of covariance with the pretest score as the covariate was used to determine the differences of each dependent variable between groups. The statistical significance was set at p less than 0.05. The current study reported η2 with confidence intervals as an index of effect size. η2 is the proportion of the total variance that is attributed to an effect. It ranges in value from 0 to 1: η2 ≥ 0.01 is regarded as a small effect, η2 ≥ 0.06 is a medium effect, and η2 ≥ 0.14 is a large effect. The formula is as follows: η2 = sum of squares between/sum of squares total.

Results

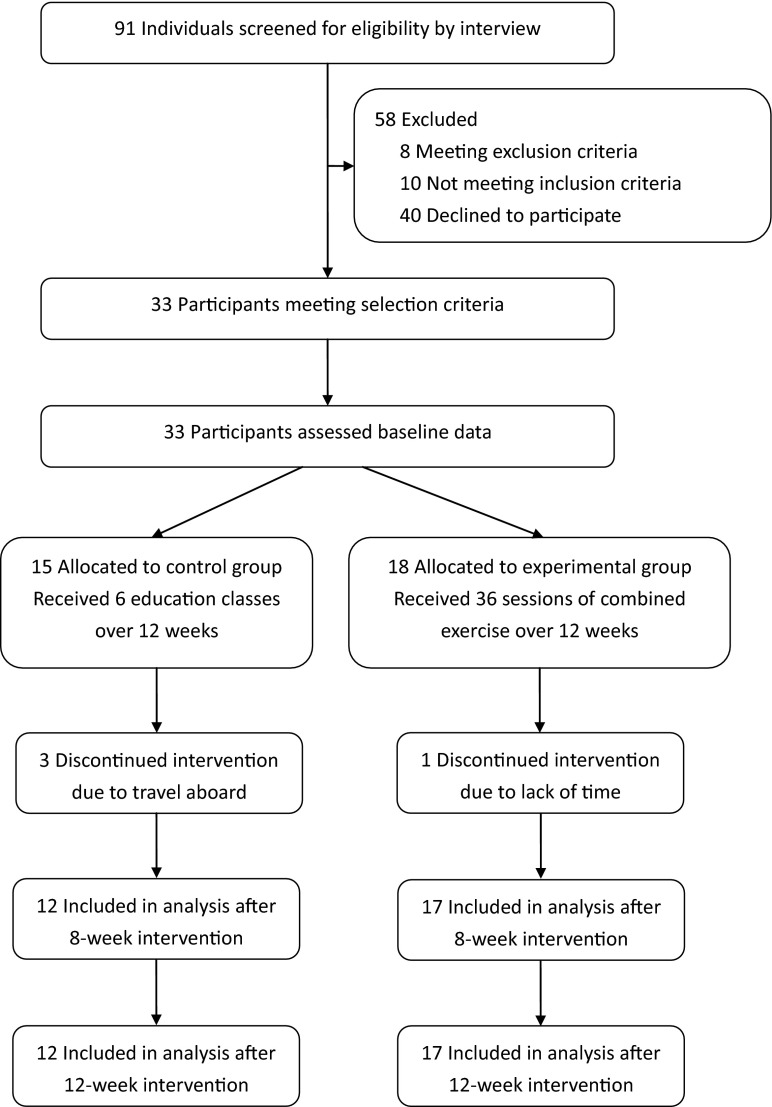

As shown in the flowchart (Fig. 1), 91 individuals were screened and 33 enrolled. Of these, 15 were assigned to the control group, and 18 were assigned to the experimental group. Of 33 participants, four did not complete the intervention (three in the control group and one in the experimental group). The 29 participants who completed the intervention attended all intervention sessions. None of the participants reported any adverse events.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment

Demographic characteristics of participants in both groups are presented in Table 1. The differences in the demographics of the two groups were insignificant. Moreover, differences in all pre-intervention selected outcome measures of the two groups were insignificant (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Control group (n = 12) | Experimental group (n = 17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 4/8 | 4/13 | 0.58 |

| Age (years) | 70.50 ± 5.50 | 70.29 ± 4.57 | 0.91 |

| Gait performance | |||

| Velocity (cm/s) | 108.31 ± 12.07 | 102.70 ± 16.17 | 0.32 |

| Stride time (s) | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Stride length (cm) | 111.03 ± 15.04 | 108.66 ± 16.92 | 0.70 |

| Stride time variability (%CV) | 10.40 ± 4.86 | 11.77 ± 7.05 | 0.57 |

| Stride length variability (%CV) | 4.75 ± 2.90 | 6.41 ± 5.67 | 0.36 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD or number

CV coefficient of variation

Table 2.

Effects of exercise on gait performance

| Measures | Control (n = 12) | Experimental (n = 17) | η 2 (CIs)8-week | η 2 (CIs)12-week | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- intervention | 8-week intervention | 12-week intervention | Pre- intervention | 8-week intervention | 12-week intervention | |||

| Six-minute walk test (m) | 424.75 ± 49.23 | 423.92 ± 46.60 | 422.33 ± 42.00 | 437.59 ± 76.68 | 484.18 ± 69.57*** | 518.88 ± 70.30*** | 0.89 (0.80, 0.92) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.94) |

| Gait performance during habitual walking | ||||||||

| Velocity (cm/s) | 108.31 ± 12.07 | 107.94 ± 10.83 | 107.82 ± 10.96 | 102.70 ± 16.17 | 114.81 ± 15.32*** | 123.96 ± 12.11*** | 0.84 (0.72, 0.88) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.83) |

| Stride time (s) | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.03 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 1.02 ± 0.06* | 0.96 ± 0.12* | 0.57 (0.30, 0.68) | 0.18 (0.01, 0.35) |

| Stride length (cm) | 111.03 ± 15.04 | 109.25 ± 14.31 | 109.22 ± 14.43 | 108.66 ± 16.92 | 116.52 ± 15.16*** | 123.83 ± 13.41*** | 0.89 (0.80, 0.92) | 0.85 (0.73, 0.89) |

| Stride time variability (%CV) | 10.40 ± 4.86 | 10.29 ± 4.50 | 11.16 ± 3.78 | 11.77 ± 7.05 | 10.30 ± 4.44 | 3.48 ± 1.14*** | 0.31 (0.06, 0.48) | 0.82 (0.68, 0.87) |

| Stride length variability (%CV) | 4.75 ± 2.90 | 5.58 ± 2.57 | 5.42 ± 2.81 | 6.41 ± 5.67 | 5.65 ± 2.69 | 2.35 ± 1.97*** | 0.55 (0.29, 0.67) | 0.70 (0.48, 0.78) |

| Gait performance during fast walking | ||||||||

| Velocity (cm/s) | 125.15 ± 20.15 | 125.04 ± 19.26 | 124.59 ± 19.69 | 137.63 ± 20.52 | 147.99 ± 17.25*** | 157.51 ± 18.58*** | 0.94 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.90 (0.81, 0.92) |

| Stride time (s) | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.08** | 0.86 ± 0.07*** | 0.86 (0.75, 0.90) | 0.86 (0.75, 0.90) |

| Stride length (cm) | 122.56 ± 15.36 | 121.60 ± 14.46 | 122.06 ± 14.74 | 128.35 ± 19.85 | 134.85 ± 18.61*** | 144.62 ± 19.57*** | 0.95 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.82 (0.68, 0.87) |

| Stride time variability (%CV) | 14.94 ± 9.18 | 15.04 ± 8.66 | 15.24 ± 8.43 | 16.74 ± 8.64 | 15.12 ± 9.97 | 6.82 ± 4.42*** | 0.19 (0.01, 0.36) | 0.52 (0.25, 0.64) |

| Stride length variability (%CV) | 5.17 ± 2.48 | 5.33 ± 2.02 | 6.25 ± 2.45 | 5.29 ± 2.80 | 5.12 ± 2.03 | 2.35 ± 1.73*** | 0.26 (0.02, 0.42) | 0.68 (0.46, 0.76) |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD

η 2 (CIs) 8-week effect size with confidence intervals after 8 weeks of exercise, η 2 (CIs) 12-week effect size with confidence intervals after 12 weeks of exercise, CV coefficient of variation

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (comparisons between groups)

These results of the intervention effects are presented in Table 2. Analysis of covariance showed that there were significant between-group effects in the 6-min walk test and velocity, stride time, and stride length at both habitual and fast walking speeds after 8 weeks of exercise. The analysis also showed significant between-group effects in the 6-min walk test and all selected gait parameters at both habitual and fast walking conditions after 12 weeks of exercise.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that a 12-week combined exercise program is effective in improving gait performance, including stride time variability and stride length variability, in both habitual and fast walking conditions. The current findings extend the existing knowledge of the effects of exercise intervention to improve gait and functional ability among older adults.

A previous meta-analysis reported that therapeutic exercise can improve gait speed in community-dwelling elderly people and that both intensity and dosage are important contributing factors (Lopopolo et al. 2006). Our exercise program would be classified as a high-intensity and high-dosage exercise based on previous studies and guidelines (American College of Sports Medicine 2014; Fox et al. 1975; Lopopolo et al. 2006; Rhea et al. 2003). Current results showed that walking endurance and gait performance, including walking velocity, stride time, and stride length in both habitual walking and fast walking conditions, improved significantly in the experimental group compared with those in the control group after both 8 and 12 weeks of exercise (Table 2). Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies. Zhuang et al. (2014) reported that a 12-week combined exercise program improved balance, gait performance, muscle strength, and lower limb joint range in community-dwelling older adults. Rubenstein et al. (2000) showed that a 12-week combined exercise program improved muscle endurance, walking endurance, and gait performance in fall-prone elderly men. These findings suggest that a short-term exercise intervention with a combination of strength, endurance, and balance training may improve joint mobility, muscle strength, and endurance and lead to improvements in walking endurance and gait performance among older adults. Our results also support a relationship between intensity and dosage of the exercise program and improvements in gait performance in both habitual walking and fast walking conditions among community-dwelling elderly people.

Combined exercise did not reduce gait variability after 8 weeks of exercise in the present study, which is not surprising given the short intervention period. A previous study demonstrated that inter-stride variability did not change after an 8-week supervised Pilates program in elderly subjects (Newell et al. 2012). Also, Granacher et al. (2012) showed that an 8-week salsa dancing program did not have significant effects on gait variability in older adults. In contrast, our results showed a significant decrease in gait variability after 12 weeks of exercise. The same finding was also reported in elderly adults following 6 weeks of intense balance training and 6 months of a multitask exercise program (Granacher et al. 2010; Trombetti et al. 2011). However, in a 6-month randomized trial of home-based multimodal exercise, significant exercise-related decreases in stride time variability were not achieved (Hausdorff et al. 2001a). Different training intensities and dosages applied in these studies may explain the discrepancies in findings (Lopopolo et al. 2006; Granacher et al. 2010). Furthermore, previous studies demonstrated that stride time variability and stride length variability were both associated with postural sway and muscle strength (Hausdorff et al. 2001a, 2001b; Callisaya et al. 2010). Our combined exercise program of balance training and muscle strengthening may include the key components to reduce stride time variability and stride length variability.

Previous studies showed that healthy young adults increase gait variability when they walk at slower speeds (Dingwell and Marin 2006; Yamasaki et al. 1991). Increased gait variability in older adults may be simply a result of slower walking speed or of other factors related to aging. Kang and Dingwell (2008) demonstrated that greater variability existed in older adults for stride time, step length, and trunk roll, independent of differences in speed. The greater variability observed in the gait of older adults may result more from a loss of strength and flexibility than from their slower speeds (Kang and Dingwell 2008). In the present study, the intervention effect on gait variability may not occur as a result of enhanced gait speed. Current results showed that a significant improvement in gait speed was observed after 8 weeks of exercise, but a significant improvement in gait variability was observed after 12 weeks of exercise, suggesting that the intervention had a direct effect on gait variability.

The limitations of this study involved lack of randomization of the sample and small sample size. Future work should have a large sample size and a randomized procedure to investigate the effects of combined exercise training on gait performance. Despite the existing evidence of an association between step width variability and a history of falls in older adults (Brach et al. 2005), step width variability was omitted in the current study and should be therefore taken into account in future research. It will also be helpful to examine the factors that contribute to gait variability and the relationships between gait variability and physiological or neuropsychological functions. Regarding neuropsychological functions, dual-tasking is a typical example that involves the potential influence of a cognitive task while performing a motor task, which is particularly evident during aging (Bergamin et al. 2014). A recent review showed a lack of evidence on the effect of using exercise to improve dual-task balance indices (Gobbo et al. 2014). Further studies could focus on intervention strategies to improve dual-task ability. Furthermore, both land- and water-based exercises have been shown to improve physical function in the elderly (Bergamin et al. 2013). Future high-quality studies should consider measuring gait performance after water-based exercise interventions.

Conclusions

The current results showed that a 12-week combined exercise program effectively improves gait performance, including gait variability in both habitual walking and fast walking conditions, among older adults. Given that gait variability is associated with fall risk (Hausdorff et al. 2001b), we speculate that our combined exercise program may be a potential intervention for fall prevention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC100-2314-B-010-021-MY2).

References

- Alexander NB. Gait disorders in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:434–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb06417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine . ACSM’s resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine. Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, Skinner JS. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautmans I, Lambert M, Mets T. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: influence of health status. BMC Geriatr. 2004;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamin M, Ermolao A, Tolomio S, Berton L, Sergi G, Zaccaria M. Water- versus land-based exercise in elderly subjects: effects on physical performance and body composition. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1109–1117. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S44198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamin M, Gobbo S, Zanotto T, Sieverdes JC, Alberton CL, Zaccaria M, Ermolao A. Influence of age on postural sway during different dual-task conditions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:271. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Berlin JE, Vanswearingen JM, Newman AB, Studenski SA. Too much or too little step width variability is associated with a fall history in older persons who walk at or near normal gait speed. J Neuroengineering Rehabil. 2005;2:21. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Studenski SA, Perera S, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB. Gait variability and the risk of incident mobility disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:983–988. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Perera S, Studenski S, Newman AB. The reliability and validity of measures of gait variability in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:2293–2296. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callisaya ML, Blizzard L, McGinley JL, Schmidt MD, Srikanth VK. Sensorimotor factors affecting gait variability in older people—a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:386–392. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, Gale CR, Lawlor DA, Matthews F, Hardy R. Objective measures of physical capability and subsequent health: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40:14–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita P, Hortobagyi T. Age causes a redistribution of joint torques and powers during gait. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1804–1811. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Marin LC. Kinematic variability and local dynamic stability of upper body motions when walking at different speeds. J Biomech. 2006;39:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, Tracy RP, McNamara R, Arnold A, Newman AB. The 6-min walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest. 2003;123:387–398. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EL, Bartels RL, Billings CE, O’Brien R, Bason R, Mathews DK. Frequency and duration of interval training programs on changes in aerobic power. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:481–484. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, Carter YH, Lamb SE. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:130–133. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo S, Bergamin M, Sieverdes JC, Ermolao A, Zaccaria M. Effects of exercise on dual-task ability and balance in older adults: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Bridenbaugh S, Bleiker E, Wehrle A, Kressig RW. Balance training and multi-task performance in seniors. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:353–358. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Bridenbaugh SA, Wolf M, Roth R, Gschwind Y, Wolf I, Mata R, Kressig RW. Effects of a salsa dance training on balance and strength performance in older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58:305–312. doi: 10.1159/000334814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Edelberg HK, Mitchell SL, Goldberger AL, Wei JY. Increased gait unsteadiness in community-dwelling elderly fallers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:278–283. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Cudkowicz ME, Firtion R, Wei JY, Goldberger AL. Gait variability and basal ganglia disorders: stride-to-stride variations of gait cycle timing in Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 1998;13:428–437. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Nelson ME, Kaliton D, Layne JE, Bernstein MJ, Nuernberger A, Singh MA. Etiology and modification of gait instability in older adults: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2117–2129. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Rios D, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1050–1056. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamtvedt G, Herbert RD, Flottorp S, Odgaard-Jensen J, Håvelsrud K, Barratt A, Mathieu E, Burls A, Oxman AD. A pragmatic randomised trial of stretching before and after physical activity to prevent injury and soreness. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:1002–1009. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.062232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HG, Dingwell JB. Separating the effects of age and speed on gait variability during treadmill walking. Gait Posture. 2008;27:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Lee LW, Collins JJ, Riley PO, Lipsitz LA. Reduced hip extension during walking: healthy elderly and fallers versus young adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:26–30. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopopolo RB, Greco M, Sullivan D, Craik RL, Mangione KK. Effect of therapeutic exercise on gait speed in community-dwelling elderly people: a meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2006;86:520–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menz HB, Latt MD, Tiedemann A, Mun San Kwan M, Lord SR. Reliability of the Gaitrite walkway system for the quantification of temporo-spatial parameters of gait in young and older people. Gait Posture. 2004;20:20–25. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(03)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell D, Shead V, Sloane L. Changes in gait and balance parameters in elderly subjects attending an 8-week supervised Pilates programme. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012;16:549–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Kim KJ, Komatsu T, Park SK, Mutoh Y. Effect of combined exercise training on bone, body balance, and gait ability: a randomized controlled study in community-dwelling elderly women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:254–259. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0819-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea MR, Alvar BA, Burkett LN, Ball SD. A meta-analysis to determine the dose response for strength development. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:456–464. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000053727.63505.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Trueblood PR, Loy S, Harker JO, Pietruszka FM, Robbins AS. Effects of a group exercise program on strength, mobility, and falls among fall-prone elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M317–M321. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.M317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: six-minute walk test, Berg balance scale, timed up & go test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther. 2002;82:128–137. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syddall H, Roberts HC, Evandrou M, Cooper C, Bergman H, Sayer AA. Prevalence and correlates of frailty among community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the Hertfordshire cohort study. Age Ageing. 2010;39:197–203. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toto PE, Raina KD, Holm MB, Schlenk EA, Rubinstein EN, Rogers JC. Outcomes of a multicomponent physical activity program for sedentary, community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2012;20:363–378. doi: 10.1123/japa.20.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetti A, Hars M, Herrmann FR, Kressig RW, Ferrari S, Rizzoli R. Effect of music-based multitask training on gait, balance, and fall risk in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:525–533. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang C. Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:896–901. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki M, Sasaki T, Torii M. Sex difference in the pattern of lower limb movement during treadmill walking. Eur J Appl Occup Physiol. 1991;62:99–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00626763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J, Huang L, Wu Y, Zhang Y. The effectiveness of a combined exercise intervention on physical fitness factors related to falls in community-dwelling older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:131–140. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S56682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]