Abstract

Background: muscle strength measured as handgrip strength declines with increasing age and predicts mortality. While handgrip strength is determined by lifestyle through nutrition and physical activity, it has almost exclusively been studied in western populations with a sedentary lifestyle. This study aims to investigate the relation between handgrip strength, ageing and mortality in a population characterised by a predominance of malnutrition and manual labour.

Design: a population-based longitudinal study.

Setting: a traditional African rural population in Ghana.

Subjects: nine hundred and twenty-three community-dwelling individuals aged 50 and older.

Methods: demographic characteristics were registered. At baseline, height, body mass index (BMI) and handgrip strength were measured and compared with those in a western reference population. Survival of the participants was documented during a period of up to 2 years.

Results: handgrip strength was dependent on age, sex, height and BMI. Compared with the western reference population, handgrip strength was lower due to a lower height and BMI but declined over age similarly. Risk of mortality was lower in participants having higher handgrip strength, with a hazard ratio of 0.94 per kg increase (P = 0.002). After adjustment for age, sex, tribe, socio-economic status, drinking water source, height and BMI, only handgrip strength remained predictive of mortality.

Conclusion: in a traditional rural African population characterised by malnutrition and manual labour, handgrip strength declines over age and independently predicts mortality similar to western populations. Handgrip strength can be used as a universal marker of ageing.

Keywords: handgrip strength, ageing, mortality, Africa, older people

Introduction

Muscle strength measured as handgrip strength is widely used as a simple and robust marker of ageing. Handgrip strength declines with increasing age in different ethnicities, especially after the age of 50 [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. At both middle and high ages, low handgrip strength is associated with increased risks of future disability [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]; of age-related diseases such as the metabolic syndrome [15], cardiovascular disease [16, 17], type 2 diabetes mellitus [18] and cognitive impairment [12, 19]; of hospitalisation [13, 20] and of treatment-related complications [13]. Moreover, low handgrip strength predicts all-cause mortality [13, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23] as well as mortality due to cardiovascular disease [6, 24] and cancer [15, 23, 24]. Consequently, low handgrip strength is considered as an accurate indicator of frailty [25].

Apart from age, sex and ethnicity, handgrip strength is dependent on height, body mass index (BMI), nutritional status and physical exercise [11, 26, 27, 28, 29]. While these determinants are closely related to lifestyle, research on handgrip strength has almost exclusively been conducted in western societies where an affluent and sedentary lifestyle is omnipresent [3, 30, 31]. In societies characterised by a predominance of malnutrition and manual labour, handgrip strength might be a reflection of dietary composition and muscle training rather than ageing. In addition, the association between handgrip strength, ageing and mortality might be mediated by age-related diseases and attenuated when these are uncommon [27, 32].

This study investigates the relation between handgrip strength, ageing and mortality in a traditional rural African population where a sedentary lifestyle is absent and age-related diseases are uncommon [32, 33, 34]. We show how handgrip strength is distributed over age and compare this distribution with its distribution in a western reference population; we assess the individual characteristics that determine handgrip strength and we assess whether handgrip strength predicts mortality in this population.

Methods

Setting and participants

This study was conducted in the Garu-Tempane District in the Upper East Region in Ghana. The area is rural, remote and one of the least developed in the country. The vast majority of the inhabitants are involved in non-commercial agriculture performed by manual labour without proper means of transportation or mechanised farming. Hospital care is absent. Infectious diseases are highly endemic and constitute the main causes of death, although the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is low (<4%) compared with other African regions [35].

Since 2002, we have kept a demographic registry of the population within a research area of 375 km2 comprising 32 villages. During yearly visits, we registered the name, age, sex, tribe and location of living of each inhabitant. In 2007, we determined the property value of each household. From this value, an index of the socio-economic status with a standard normal distribution was calculated according to the Demographic and Health Survey method [36]. In addition, we registered the main drinking water source of each household. Water from boreholes was classified as safe and water from open wells and rivers as unsafe, based on their pathogen contents [37]. Annual migration relative to the study population's size was 2% into and 1% out of the research area. An elaborate description of this study population has been given elsewhere [32, 34, 36, 37].

Ethical approval was given by the Ethical Review Committee of Ghana Health Services, the Committee Medical Ethics of the Leiden University Medical Center, and the local chiefs and elders. Because of illiteracy, informed consent was obtained orally from the participants after explanation of the purpose and conduction of this research project. Participation was only proceeded after verbal consent in the participant's own language.

Measurements

In 2009 and 2010, we measured handgrip strength among 923 inhabitants aged 50 and older, who were recruited in villages visited consecutively. To ensure maximal participation, we set up a mobile field work station in the villages and, if necessary, brought less mobile participants by car. Reasons of exclusion included death of the individual since the last registration (n = 48), refusal of participation (n = 35), absence from the research area during our visits because of migration or travelling (n = 30) and other reasons (n = 46).

Handgrip strength in kilograms was measured using a calibrated Jamar hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston Inc., Bolingbrook, IL, USA), while the participant was standing in an upright position with the arms unsupported parallel to the body. The width of the dynamometer's handle was adjusted to each participant's hand size. Participants were instructed to exert maximal force with each hand once. The handgrip strength of the hand with the highest measurement was registered. Body height and weight were measured with a calibrated length scale and weighing scale. BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by squared body height in metres.

After the measurements in 2009 and 2010, follow-up data on 915 individuals (99.1%) were available in our demographic registry. Follow-up lasted until death, migration out of the research area, loss to follow-up or our last visit to the research area in 2011.

Reference population

To compare the Ghanaian study population with a western population, we retrieved data from the Leiden Longevity Study. This study included offspring of long-lived native Dutch siblings and the partners of the offspring without selection criteria on health or demographic characteristics. The design of the study has been previously described in more detail [38]. We used data on age, sex, height, BMI and handgrip strength measured in 316 offspring and 311 partners aged 50–80. Handgrip strength did not differ between offspring and partners. The measurements were performed with the same hand dynamometer and in the same position as described for the Ghanaian study population [39].

Analyses

Differences between both populations in mean values of height, BMI and handgrip strength and in the decline in handgrip strength per year of age were determined by linear regression with age as an independent variable and were restricted to participants aged 50–80. Determinants of handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population were assessed by linear regression including all participants aged 50–97. Handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population was standardised according to the age group- and sex-specific mean height and BMI in the Dutch reference population, using the regression coefficients obtained for these determinants in the Ghanaian study population. To investigate whether handgrip strength predicted mortality, we constructed Kaplan–Meier survival curves with left truncation to account for different ages at baseline. Survival curves were separated between individuals classified as having low or high handgrip strength according to the age group- and sex-specific median. Hazard ratios were determined by Cox regression with follow-up starting at the time of the measurements of handgrip strength.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the Ghanaian study population at the moment of handgrip strength measurement in 2009 or 2010. For comparison, we used data from a Dutch reference population including 316 males and 311 females aged 50–80. As described previously for this population [39], mean height (standard deviation) was 177.9 cm (7.7) in males and 165.7 cm (5.9) in females; mean BMI was 27.1 (4.1) in males and 26.4 (4.6) in females and mean handgrip strength was 46.9 kg (8.1) in males and 29.3 kg (5.5) in females. These values of height and BMI were higher than those in the Ghanaian study population (both P < 0.001) adjusted for age.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Ghanaian study population

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals, n | 480 | 443 |

| Age, median (IQR) years | 67 (58–76) | 61 (56–70) |

| Tribe, % | ||

| Bimoba | 69.5 | 68.6 |

| Kusasi | 22.5 | 25.5 |

| Other | 8.1 | 5.9 |

| Household property value, median (IQR) US$ | 1,008 (500–1,700) | 1,196 (583–2,108) |

| Access to safe drinking water, % | 86.7 | 88.5 |

| Weight, kg | 50.6 (7.9) | 45.5 (7.6) |

| Height, cm | 167.5 (6.8) | 157.9 (6.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.0 (2.3) | 18.2 (2.6) |

| Handgrip strength, kg | 31.3 (8.7) | 23.6 (5.9) |

Data are presented as means with standard deviations unless specified otherwise.

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index.

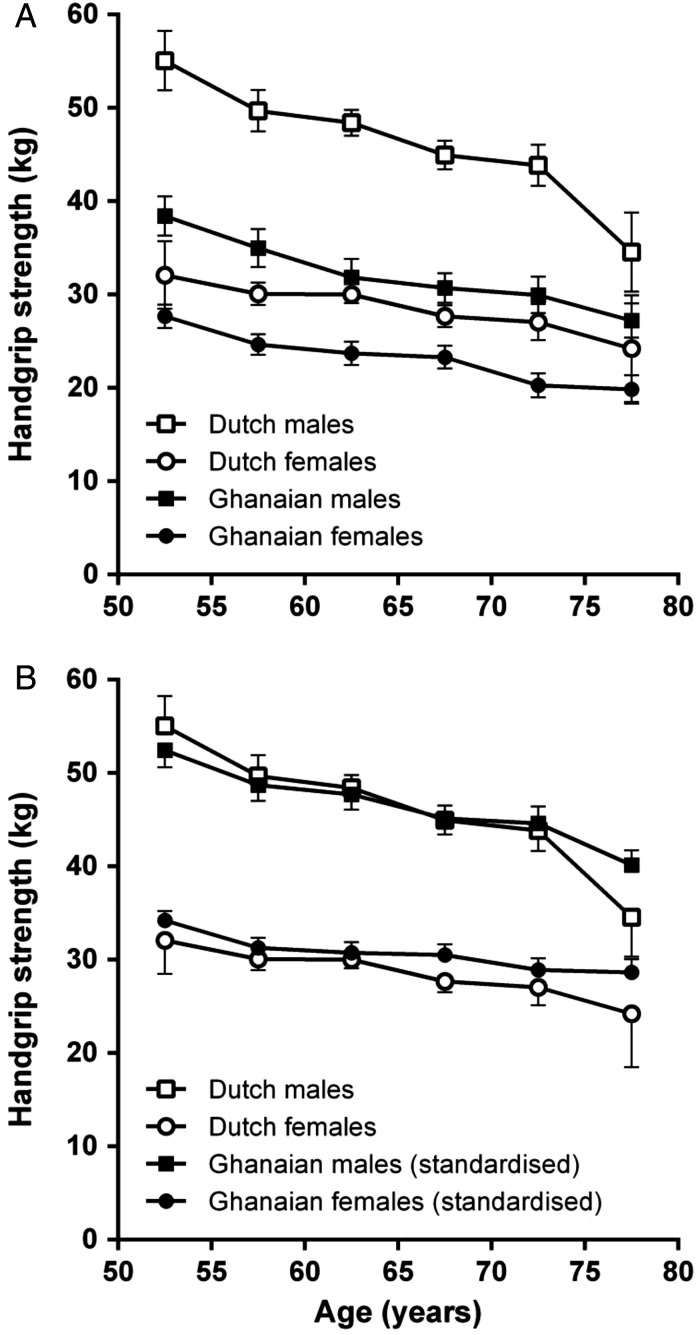

Figure 1A shows that mean handgrip strength was lower in the Ghanaian study population compared with the Dutch reference population. Overall, the difference (95% confidence interval) was 14.7 kg (13.6–15.8) in males and 5.7 kg (4.9–6.4) in females (both P < 0.001). In the Ghanaian study population, handgrip strength declined with 0.4 kg per year of age (0.3–0.5) in males and with 0.3 kg per year of age (0.2–0.4) in females (both P < 0.001). For comparison, handgrip strength in the Dutch reference population declined with a slightly higher rate of 0.6 kg per year of age (0.5–0.7) in males up to the age of 80 (P = 0.046), with a similar rate in males up to the age of 75 years (P = 0.384) and with a similar rate in females (P = 0.687).

Figure 1.

Handgrip strength per sex and per age group in the Ghanaian study population compared with the Dutch reference population. (A) A comparison of mean handgrip strength with 95% confidence intervals per 5-year age category and per sex as observed in the Ghanaian study population and the Dutch reference population [39]. (B) Idem after standardisation of the individual handgrip strength measurements in the Ghanaian study population according to the age group- and sex-specific height and BMI of the Dutch reference population [39].

Determinants of handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population are described in the Supplementary data, Table S2 available in Age and Ageing online. In a multivariate analysis of demographic and anthropometric characteristics, handgrip strength in both sexes was higher in individuals with a higher age, with a higher height and with a higher BMI. When this analysis was not stratified by sex, handgrip strength was 6.0 kg (5.0–7.0) higher in males (P < 0.001).

Figure 1B shows that the differences in handgrip strength between the Ghanaian study population and the Dutch reference population were attenuated when handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population was standardised according to the age group- and sex-specific mean height and BMI of the Dutch reference population. Hereby accounting for the differences in height and BMI between both populations, handgrip strength was similar in males (P = 0.350) and 1.7 kg (0.9–2.4) higher in Ghanaian females (P < 0.001). Standardised handgrip strength declined with similar rates over age in males (P = 0.067) and females (P = 0.233) in both populations.

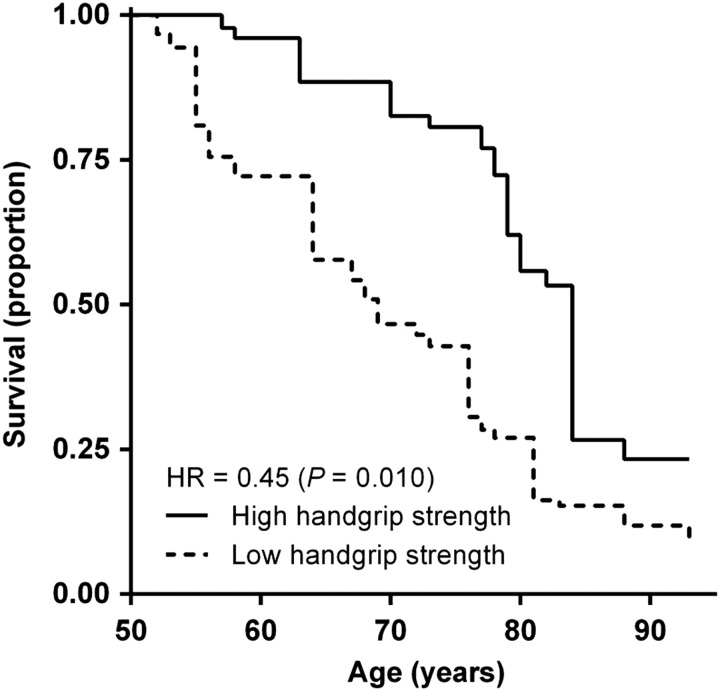

Figure 2 shows how mortality is predicted by handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population. Data on follow-up were available for 476 males and 439 females. From the baseline measurements in 2009 and 2010 through the end of follow-up in 2011, we recorded 1,492 person-years and 46 deaths. Mean individual follow-up was 20 months (6). Individuals were classified as having low or high handgrip strength according to the age group- and sex-specific median. Risk of mortality was lower in individuals with high handgrip strength, with a hazard ratio of 0.45 (P = 0.010) adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 2.

Handgrip strength as a predictor of mortality in the Ghanaian study population. Age-specific survival is dependent on handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population. Handgrip strength is classified as low or high according to the age group- and sex-specific medians. The hazard ratio (HR) is given for individuals with high handgrip strength relative to those with low handgrip strength, adjusted for age and sex.

Determinants of mortality in the Ghanaian study population are described in the Supplementary data, Table S3 available in Age and Ageing online. While handgrip strength, age and BMI determined mortality in the univariate analysis, only handgrip strength determined mortality in the multivariate analysis with a hazard ratio of 0.94 per kg increase (P = 0.016). The association between handgrip strength and mortality in the univariate analysis remained unchanged after the adjustments in the multivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, the association of handgrip strength with mortality was not different between individuals below or above the age of 65 (P = 0.920), between males and females (P = 0.380), between individuals with a low or high BMI (P = 0.188) or between individuals with a low or high socio-economic status (P = 0.890).

Additional adjustment for family relations by clustering on the household level did not materially change the results.

Discussion

This study aims to study the relation between handgrip strength, ageing and mortality in a traditional rural African population with a non-western lifestyle. Handgrip strength was lower compared with a western reference population due to a lower height and BMI, but it declined with a similar rate over age. Lower levels of handgrip strength predicted mortality independent of its other determinants related to nutritional and socio-economic status. Its predictive value was comparable with that known for western populations [6, 13, 21, 24].

The Ghanaian study population contrasts sharply with western populations, as a sedentary lifestyle is absent and age-related diseases are uncommon [32, 33, 34]. Because handgrip strength is dependent on nutritional status [29], this contrast is most relevantly characterised by a low BMI and near absence of obesity [32]. In line with this, handgrip strength was closely related to BMI and low compared with a Dutch reference population due to a lower BMI. Besides nutrition, handgrip strength is associated with physical activity and socio-economic status [26, 27, 40, 41, 42]. Unlike western populations, almost all inhabitants in the research area engage in lifelong physical exercise. Manual labour in farming and housekeeping is necessary for subsistence up to the highest ages. Meanwhile, mechanical means of farming and transportation are lacking. Most inhabitants live in poverty [33], and common property is confined to cattle, fertiliser and iron roofing [36]. Despite these differences, the variation in handgrip strength in the Ghanaian study population was similar to that in the Dutch reference population and as reported for other western populations [2, 43, 44]. Moreover, handgrip strength declined over age in these populations similarly.

Few other studies have described handgrip strength in traditional lean populations in Africa. Absolute levels of handgrip strength have been reported to be up to 4 kg lower in rural Kenya, rural Malawi and among refugees from Rwanda compared with those found at similar ages in the Ghanaian study population [31, 45, 46]. Handgrip strength in these populations was also, though less, dependent on BMI. The decline in handgrip strength over age was similar to that in the Ghanaian study population. In a population-wide study in South Africa, handgrip strength did not differ between ethnicities or between rural and urban areas, but it was associated with age, anthropometry and health [30]. None of these studies related handgrip strength with mortality.

As a western reference population, we used the Leiden Longevity Study [39]. Handgrip strength in this study is slightly higher compared with other western populations. This difference can be a result of international variations in the level of handgrip strength, while the declines over age are similar [4]. Alternatively, this difference can be a result of variations in body position during the measurements. Body position influences the estimation of handgrip strength, although it is not likely to influence its decline over age or its relation with mortality [47, 48, 49, 50]. When using reference data from a meta-analysis of handgrip strength in 12 western study populations with a body position different from the Leiden Longevity Study, the decline in handgrip strength over age was similar to that in the Ghanaian study population [7]. Suitably, the body position during the measurements in the Ghanaian study population was identical to that in the Leiden Longevity Study.

This study has the following limitations. First, handgrip strength was measured only once, while it might have been valuable to relate individual changes in handgrip strength over age with anthropometry and mortality. Second, nutritional status was documented by BMI, while it might have been valuable to relate dietary composition and physical activity with the level of handgrip strength as well as its predictive value of mortality, but these determinants were not formally documented. Lastly, because diseases were not registered, the possible effects of diseases on handgrip strength could not be studied and neither could handgrip strength be assessed as a predictor of morbidity.

In conclusion, this study shows that handgrip strength declines over age with a similar rate and functions equally well as an independent predictor of mortality in a traditional rural African population compared with western populations. Across divergent environments, in different populations, and despite variations in lifestyle, handgrip strength can be easily and universally used to identify frail people at increased risk of mortality.

Key points.

• Handgrip strength in rural Africa is lower than in western populations due to a lower height and BMI.

• Handgrip strength declines similarly over age in rural Africa and western populations.

• Handgrip strength is an independent predictor of mortality in rural Africa.

• Handgrip strength can be used as a universal marker of ageing.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

The research in the Ghanaian research area was supported by the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancements of Tropical Research [WOTRO 93-467]; the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [NWO 051-14-050]; the European Union-funded Network of Excellence LifeSpan [FP6 036894]; a grant of the Board of Leiden University Medical Center; and Stichting Dioraphte. The measurement of handgrip strength in the Leiden Longevity Study was supported by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [NGI/NWO 05040202, NCHA 050-060-810] and the European Union-funded project MYOAGE [HEALTH-2007-2.4.5-10]. The sponsors had no role in the study design, subject recruitment, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: J.J.E.K., D.v.B. and R.G.J.W. Recruitment of subjects and execution of the measurements: J.J.E.K. and D.v.B. Provision of data from the Leiden Longevity Study: D.v.H. Statistical analyses: J.J.E.K. Interpretation of the results: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: J.J.E.K. Intellectual contribution to and critical revision of the manuscript: D.v.B., D.v.H. and R.G.J.W.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the dedicated assistance of the local staff of the research team in the Garu-Tempane District in Ghana. The authors are grateful for the help of Dr U.K. Eriksson and H. Sanchez-Faddiev in the field work and of Z. Li in the analyses and the drafting of the manuscript.

References

Only the most important references are listed here and are represented by bold type throughout the text. The full list of references is provided in the Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Forrest KYZ, Bunker CH, Sheu Y, Wheeler VW, Patrick AL, Zmuda JM. Patterns and correlates of grip strength change with age in Afro-Caribbean men. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massy-Westropp NM, Gill TK, Taylor AW, Bohannon RW, Hill CL. Hand grip strength: age and gender stratified normative data in a population-based study. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen-Ranberg K, Petersen I, Frederiksen H, Mackenbach JP, Christensen K. Cross-national differences in grip strength among 50+ year-old Europeans: results from the SHARE Study. Eur J Ageing 2009; 6: 227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki H, Kasagi F, Yamada M, Fujita S. Grip strength predicts cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and elderly persons. Am J Med 2007; 120: 337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohannon RW, Peolsson A, Massy-Westropp N, Desrosiers J, Bear-Lehman J. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2006; 92: 11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallinen J, Stenholm S, Rantanen T, Heliövaara M, Sainio P, Koskinen S. Hand-grip strength cut points to screen older persons at risk for mobility limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 1721–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taekema DG, Gussekloo J, Maier AB, Westendorp RGJ, de Craen AJM. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health: a prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohannon RW. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2008; 31: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rantanen T. Muscle strength, disability and mortality. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2003; 13: 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artero EG, Lee DC, Lavie CJ, et al. Effects of muscular strength on cardiovascular risk factors and prognosis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2012; 32: 351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, et al. Objective measures of physical capability and subsequent health: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2011; 40: 14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010; 341: c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling CHY, Taekema D, de Craen AJM, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RGJ, Maier AB. Handgrip strength and mortality in the oldest old population: the Leiden 85-plus study. CMAJ 2010; 182: 429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, et al. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008; 337: a439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gale CR, Martyn CN, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Grip strength, body composition, and mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodds R, Kuh D, Aihie Sayer A, Cooper R. Physical activity levels across adult life and grip strength in early old age: updating findings from a British birth cohort. Age Ageing 2013; 42: 794–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenholm S, Tiainen K, Rantanen T, et al. Long-term determinants of muscle strength decline: prospective evidence from the 22-year mini-Finland follow-up survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cawthon PM, Fox KM, Gandra SR, et al. Clustering of strength, physical function, muscle, and adiposity characteristics and risk of disability in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 781–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norman K, Stobäus N, Gonzalez MC, Schulzke JD, Pirlich M. Hand grip strength: outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin Nutr 2011; 30: 135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramlagan S, Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Hand grip strength and associated factors in non-institutionalised men and women 50 years and older in South Africa. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chilima DM, Ismail SJ. Nutrition and handgrip strength of older adults in rural Malawi. Public Health Nutr 2001; 4: 11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koopman JJE, van Bodegom D, Jukema JW, Westendorp RGJ. Risk of cardiovascular disease in a traditional African population with a high infectious load: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e46855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ling CHY, de Craen AJM, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RGJ, Maier AB. Handgrip strength at midlife and familial longevity: the Leiden Longevity Study. Age (Dordr) 2012; 34: 1261–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurst L, Stafford M, Cooper R, Hardy R, Richards M, Kuh D. Lifetime socioeconomic inequalities in physical and cognitive aging. Am J Public Health 2013; 103: 1641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haas SA, Krueger PM, Rohlfsen L. Race/ethnic and nativity disparities in later life physical performance: the role of health and socioeconomic status over the life course. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2012; 67: 238–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birnie K, Cooper R, Martin RM, et al. Childhood socioeconomic position and objectively measured physical capability levels in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e15564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aadahl M, Beyer N, Linneberg A, Thuesen BH, Jørgensen T. Grip strength and lower limb extension power in 19–72-year-old Danish men and women: the Health2006 study. BMJ Open 2011; 1: e000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werle S, Goldhahn J, Drerup S, Simmen BR, Sprott H, Herren DB. Age- and gender-specific normative data of grip and pinch strength in a healthy adult Swiss population. J Hand Surg 2009; 34: 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little MA, Johnson BR. Grip strength, muscle fatigue, and body composition in nomadic Turkana pastoralists. Am J Phys Anthropol 1986; 69: 335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pieterse S, Manandhar M, Ismail S. The association between nutritional status and handgrip strength in older Rwandan refugees. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56: 933–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.