Abstract

A20 protects against pathologic vascular remodeling by inhibiting the inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB. A20’s function has been attributed to ubiquitin editing of receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) to influence activity/stability. The validity of this mechanism was tested using a murine model of transplant vasculopathy and human cells. Mouse C57BL/6 aortae transduced with adenoviruses containing A20 (or β-galactosidase as a control) were allografted into major histocompatibility complex-mismatched BALB/c mice. Primary endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, or transformed epithelial cells (all human) were transfected with wild-type A20 or with catalytically inactive mutants as a control. NF-κB activity and intracellular localization of RIP1 was monitored by reporter gene assay, immunofluorescent staining, and Western blotting. Native and catalytically inactive versions of A20 had similar inhibitory effects on NF-κB activity (−70% vs. −76%; P > 0.05). A20 promoted localization of RIP1 to insoluble aggresomes in murine vascular allografts and in human cells (53% vs. 0%) without altering RIP1 expression, and this process was increased by the assembly of polyubiquitin chains (87% vs. 28%; P < 0.05). A20 captures polyubiquitinated signaling intermediaries in insoluble aggresomes, thus reducing their bioavailability for downstream NF-κB signaling. This novel mechanism contributes to protection from vasculopathy in transplanted organs treated with exogenous A20.—Enesa, K., Moll, H. P., Luong, L., Ferran, C., Evans, P. C. A20 suppresses vascular inflammation by recruiting proinflammatory signaling molecules to intracellular aggresomes.

Keywords: NF-κB, molecular mechanism, receptor interacting protein

The zinc finger protein A20 protects the vessel wall from pathologic vascular remodeling, including transplant vasculopathy, the pathognomonic feature of chronic rejection (1–4). A20 prevents transplant vasculopathy by inhibiting endothelial cells (EC) activation and therefore decreasing leukocyte recruitment, by suppressing EC apoptosis and by inhibiting smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation (1–7). Previous studies revealed that accommodated xenografts or allografts that resist chronic rejection express elevated levels of endogenous A20 in the graft vasculature (1, 7). Moreover, exogenous expression of A20 following viral delivery reduced inflammation and vasculopathy in allografts (2).

A20 suppresses inflammation by inhibiting the activity of the transcription factor NF-κB, therefore precluding the up-regulation of numerous inflammatory genes (8–12). In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB molecules that bind its nuclear localization sequence (13). NF-κB can be activated by several stimuli including pathogen-associated molecules, cytokines, oxidative stress, and ultraviolet radiation. These stimuli trigger a cascade of intracellular signaling events, including posttranslational modification of signaling intermediaries with polyubiquitin (linked through Lys63 or linear chains) [e.g., receptor interacting protein (RIP1), TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs), TGF-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1)] that provide platforms for downstream signaling (14–20). This culminates in the activation of IKK2 (13, 14). Activated IKK2 subsequently phosphorylates IκB, thereby tagging it for Lys48-linked polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation, releasing NF-κB for nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation (13, 14).

Our group and others demonstrated that A20 belongs to a novel family of deubiquitinating cysteine proteases (21–23). A20 also has ubiquitin E3 ligase activity mapped to zinc finger 4 at the C terminus (23). It was suggested that A20 inhibits NF-κB activation by sequentially using its ubiquitin-editing activities to inactivate RIP1, downstream from TNFR1 signaling (23, 24). Specifically, it was proposed that A20 removes Lys63-linked polyubiquitin from RIP1 and TRAF6 (via its cysteine protease domain) and subsequently engages its E3 ligase domain to add Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains to these molecules, thus targeting them for degradation (23). On the other hand, Shembade et al. provided evidence that A20 controls NF-κB activation by preventing interactions between components of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and E3 ubiquitin ligases, which interferes with the ubiquitination status of these signaling intermediaries (25). Alternatively, binding of A20 to polyubiquinated signaling molecules such as IKKγ/NF-κB essential modulator has been proposed as another noncatalytic mechanism by which A20 could inhibit NF-κB activation (26). However, none of the proposed A20’s NF-κB inhibitory mechanisms have been validated in vivo.

In the present study, we demonstrate that exogenous expression of A20 reduces inflammatory responses in vascular allografts and in primary vascular cell cultures through a novel mechanism that does not rely on RIP1 destabilization or ubiquitin editing but rather on targeting polyubiquitinated signaling molecules to insoluble aggresomes. Moreover, we provide evidence that endogenous A20 can use this mechanism to suppress NF-κB by demonstrating that endogenous A20 and RIP1 localize to an insoluble cellular compartment in response to inflammatory stimulation. This observation uncovers a novel nonenzymatic mechanism by which A20 controls inflammatory signaling. It also indicates that aggresomes are not simply depots for misfolded or damaged proteins, but instead participate in the temporal regulation of signaling cascades and hence may be pharmacologically targeted to inhibit NF-κB activation and hence inflammation, which could be exploited for prevention or treatment of vascular diseases such as transplant vasculopathy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse aorta to carotid allografts

Aortic to carotid vascular allografts were performed between totally major histocompatibility complex mismatched C57Bl/6 (donor) and Balb/c (recipient) mice, as previously described (2). Donor aortae were transduced ex vivo by intraluminal treatment with 1 × 108 plaque forming units of recombinant adenovirus (rAd.) A20 or rAd.βgal for 20 minutes. Grafts were retrieved 2 days after transplantation and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for mRNA and protein analysis or embedded in tissue freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Science, Durham, NC, USA) and frozen at −80°C for immunohistochemistry analysis. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Committee for Use and Care of Laboratory Animal.

Reagents and antibodies

Human recombinant TNF-α and IL-1β were obtained commercially (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anti-RelA (sc372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-RIP1 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Oxford, United Kingdom, and sc-7881; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–human influenza hemagglutinin (HA) (Roche, Burgess Hill, United Kingdom), anti–green fluorescent protein (GFP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-TRAF6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-IKKγ (BD Biosciences), anti-moesin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH;Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences, Gibbstown, NJ, USA), anti-A20 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; and ab13597, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), and anti-PDHC (sc-98751; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies were obtained commercially. Lysotracker was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated.

Immunohistochemistry

Six micrometer tissue sections were immunostained using antibodies against A20 and RIP1 followed by Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 fluorescent secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Slides were also labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for nuclear staining (1 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein and mRNA analysis of allografts

Total mRNA and protein extracts were recovered from tissue samples using Norgen’s RNA/DNA/Protein purification kit (Thorold, ON, Canada). After reverse transcription of mRNA using iScript reagents (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), cDNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using itaq SYBR green universal master mix (Biorad) and the following primers for 28S (fwd: 5′-ATACCGGCACGAGACCGATAGTCA-3′ rev: 5′- GCGGACCCCACCCGTTTACCTC-3′), A20 (fwd: 5′-AAACCAATGGTGATGGAAACTG-3′, rev: 5′-GTTGTCCCATTCGTCATTCC-3′) and VCAM-1 (fwd: 5′-TCTGGGAAGCTGGAACGAAG-3′, rev: 5′-CAAACACTTGACCGTGACCG-3′). For protein analysis, SDS-PAGE was performed on 4–15% polyacrylamide gels (Biorad). After tranfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) by semidry blotting, membranes were imunoblotted with antibodies for RIP1, A20, and the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Adenoviruses

rAd.A20 was described previously (9). rAd.βgal is a kind gift of Dr. R. Gerard (University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). Human coronary artery EC and SMC cultures were transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 100 and 500, respectively. At this multiplicity of infection, >90% of cells express the transgene with no or minimal toxicity.

Plasmids

Expression vectors encoding HA epitope-tagged A20 (pHM6-A20) or GFP-tagged A20 (pEGFP-A20) or versions that were mutated at Cys103 and incapable of deubiquitination (A20C103S) have been previously described (22). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using pHM6-A20 or pEGFP-A20 as templates and sense (CCAGAAACAAGGGCTTTGCCACACTGGTTTCATCGAGTACAGAG) and antisense (TCTTGTACTCGATGAAAGCCAGTGTGGCAAAGCCCTTGTTTTTCTGG) primers to generate versions of A20 in which Cys residues 624 and 627 (within zinc finger 4) were mutated to Ala to inhibit E3 ligase activity (A20 C624627A). These mutations were also made using pHM6-A20C103S and pEGFP-A20C103S templates to generate versions of A20 that possessed neither deubiquitinating nor E3 ligase activity (A20 C103S/C624627A). Versions of A20 that were deleted at the C terminus (1–712, 1–468, and 1–366) and FLAG-tagged at the N terminus were provided by Prof. Rudi Beyaert (Ghent, Belgium).

Cell culture

Human coronary artery ECs (HCAECs) and human coronary artery SMCs (HCASMCs) were purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ, USA), cultured in 5% CO2 humified atmosphere using Lonza’s EGM 2-MV and SmGM medium, respectively. Cells were used for experiments between passages 5 and 7. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were collected using collagenase and cultured as described previously (27). HeLa, HEK293T cells, and A20−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured using DMEM/10% fetal calf serum, supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin G/100 µg/ml streptomycin. Transient transfection of cells was achieved using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions or using recombinant adenoviruses. Cells were exposed to hypoxia (defined as 1% O2) using the Ruskinn Hypoxia Workstation (Baker Ruskinn, Sanford, ME, USA) prior to reoxygenation (20% O2) as previously described (28).

Assays of NF-κB intracellular localization

Intracellular localization of endogenous RelA was assessed by immunostaining of paraformaldehyde-fixed cells using anti-RelA antibodies and Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibodies followed by laser-scanning confocal microscopy (LSM 510 META; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Image analysis was performed using Velocity software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom) to calculate the ratio of RelA present in the nucleus compared with the cytoplasm.

Assay of NF-κB transcriptional activity

NF-κB transcriptional activity was measured using an NF-κB reporter (pGL2) as described previously (22). Cells were cotransfected with pNF-luc and pRL-TK (encoding Renilla luciferase to normalize transfection efficiency) using Lipofectamine and incubated for 16 hours. Cells were then treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 16 hours before measurement of NF-κB activity. Firefly and renilla luciferase activity was assessed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and luminescence counter (Topcount Microplate Scintillation; Packard, Meriden, CT, USA).

Western blotting analysis of cultured cells

Whole cell lysates were made using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). Soluble and insoluble fractions were prepared by harvesting the cells in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2% NP40, and protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. The supernatant contained the Triton-soluble fraction. The pellet, containing the insoluble fraction, was resuspended in RIPA buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors. Western blotting was performed using 7.5% polyacrylamide gels, densitometry was carried out using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and results were plotted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Statistics

Differences between samples were analyzed using a paired Student’s t test and ANOVA. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

A20 reduces inflammatory responses without altering RIP1 expression in vascular allografts and cultured human vascular cells

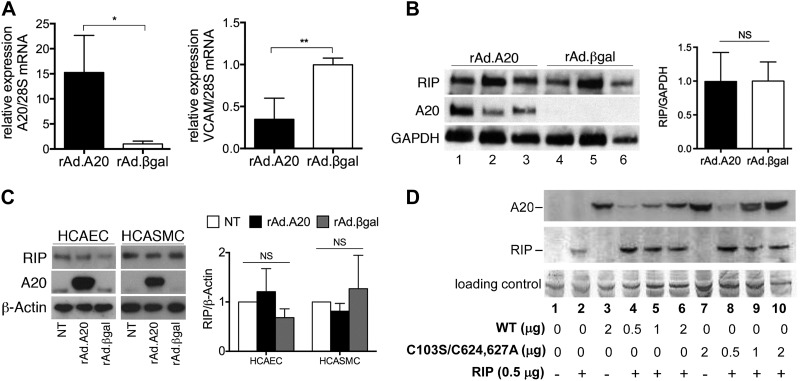

It was suggested that A20 inhibits NF-κB by promoting RIP1 proteasomal degradation (23). We explored this mechanism in vivo in mouse aortic vascular allografts that were transduced with recombinant adenoviruses containing A20 (rAd.A20) or control β-galactosidase (rAd.βgal), immediately before transplantation. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis demonstrated that treatment of allografts with rAd.A20 significantly enhanced expression of A20 2 days after transplantation (Fig. 1A, left, and B; compare 1–3 with 4–6). Overexpression of A20 was coupled with a significant reduction in mRNA levels of the proinflammatory and NF-κB–dependent adhesion molecule VCAM-1 compared with rAd.βgal-treated vessels (Fig. 1A, right). Notably, overexpression of A20 in aortic allografts did not influence RIP1 protein levels (Fig. 1B), indicating that the anti-inflammatory effects of A20 can be uncoupled from RIP1 destabilization. This result was validated in rAd.A20-transduced primary HCAECs and HCASMCs. RIP1 protein levels were unaltered in A20 overexpressing cells compared with levels observed in rAd.βgal-transduced controls (Fig. 1C). Similarly, neither wild-type A20 nor deubiquitinase and E3 ligase-deficient A20 (C103S/C624627A) influenced RIP1 protein levels in HEK 293 cells (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

A20 did not alter RIP1 expression in vascular allografts and cultured cells. A–C) Vascular allografts were treated with rAd.A20 or rAd.βgal at the time of transplant and harvested 48 hours later (n = 3/group). A) Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure levels of A20 (left) and VCAM-1 (right) mRNA. Results are expressed as mean ± sd. B) Expression levels of RIP1, A20, and GAPDH were assessed by Western blotting using total protein lysates. RIP1 levels in vascular allografts treated with rAd.A20 or rAd.βgal were normalized to those of housekeeping gene GAPDH and quantified by densitometry. RIP1 over GAPDH ratios are expressed as means ± sd. C) HCAECs or HCASMCs were transduced with rAd.A20 or rAd.βgal or were left nontransduced (NT). After 48 hours, expression levels of RIP1, A20, and β-actin were determined by Western blotting. Representative blots are shown (left). Expression levels of RIP1 were quantified by densitometry and normalized by measuring β-actin. The ratio RIP1:β-actin was calculated for each sample, and mean values with sd are shown (right) (n = 3 for HCAECs; n = 4 for HCASMC). D) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with plasmids containing E-tagged RIP1 and with varying quantities of pHM6-A20 wild-type (WT) or catalytically inactive A20 (pHM6-C103S/C624627A). Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA epitope (A20) or anti–E-tag (RIP1) antibodies. Data shown are representative of 12 independent experiments.

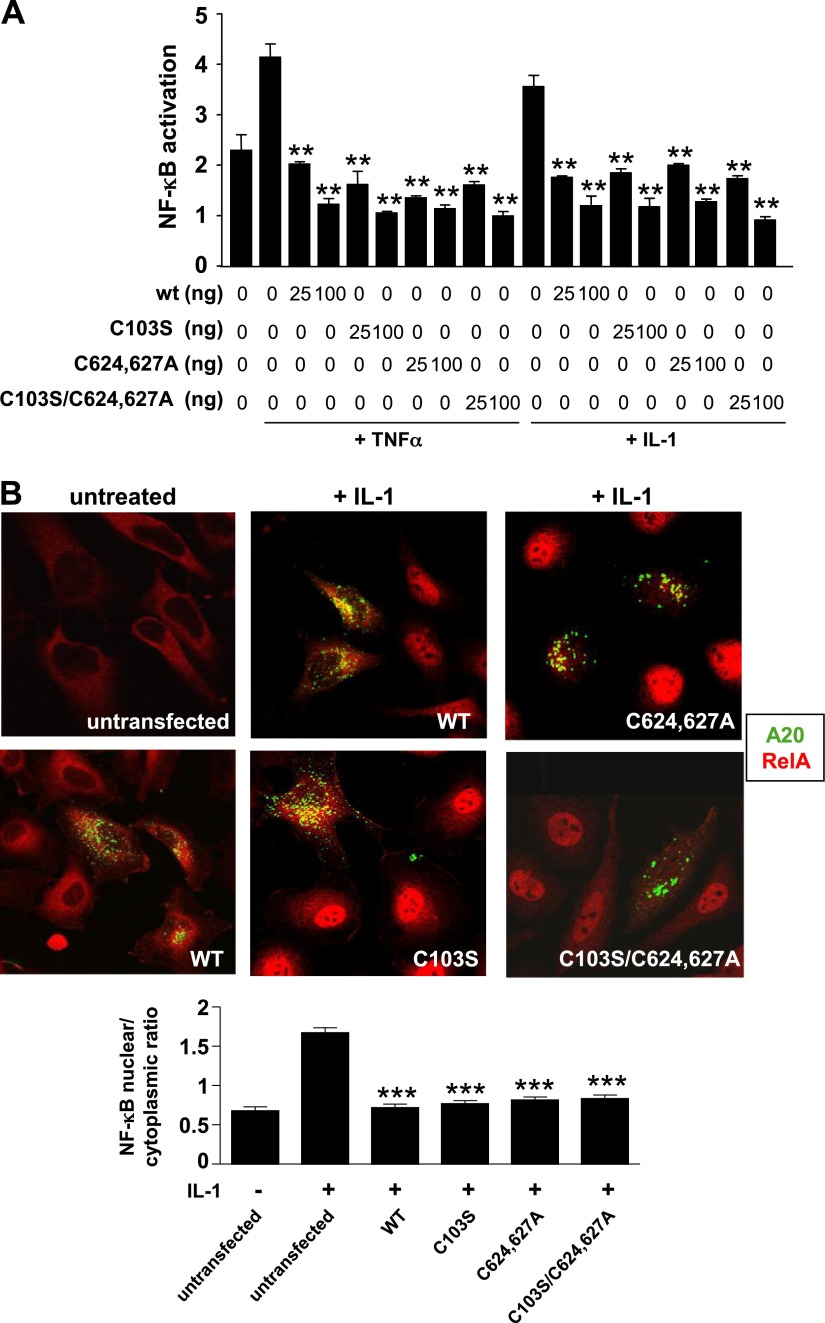

The ubiquitin-editing activities of A20 are not required for NF-κB regulation

Given that A20 did not alter RIP1 expression, we hypothesized that the deubiquitinating and E3 ligase activities of A20 were not required for its anti-inflammatory effects. To test this, we compared the NF-κB inhibitory capacity of wild-type A20 to that of A20 mutants inactive for deubiquitination (C103S), E3 ligase activity (C624627A), or both (C103S/C624627A). Studies using A20-deficient MEFs or HeLa cells revealed that wild-type and all catalytically inactive forms of A20 precluded nuclear localization of NF-κB and showed significant and comparable inhibitory effects on NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S1) in response to TNF-α or IL-1. We conclude that A20 can inhibit NF-κB independently from its ubiquitin-editing activities.

Figure 2.

NF-κB suppression by A20 does not require ubiquitin editing. A) A20−/− MEFs were cotransfected with varying amounts of pHM6-A20 wild-type (WT) or with A20 versions mutated at C103S, C624627A, or C103S/C624627A and with fixed amounts of NF-κB reporter gene (pGL2) and Renilla luciferase control (pRL-TK) before stimulation with TNF-α or IL-1 for 16 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed to determine ratio firefly/renilla luciferase, which is a measure of NF-κB activity normalized for transfection efficiency. Mean values calculated from triplicate wells were pooled from 4 experiments and are shown with sd. B) HeLa cells were transfected with pEGFP-A20 wild type (WT, green) or with versions mutated at C103S, C624627A, or C103S/C624627A (green). Transfected cultures (or untransfected controls) were stimulated with IL-1 (20 ng/ml) for 15 minutes. The intracellular localization of RelA (red) was assessed by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. Representative images and the proportion of RelA that localized to the nucleus (mean nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio ± sem) are shown.

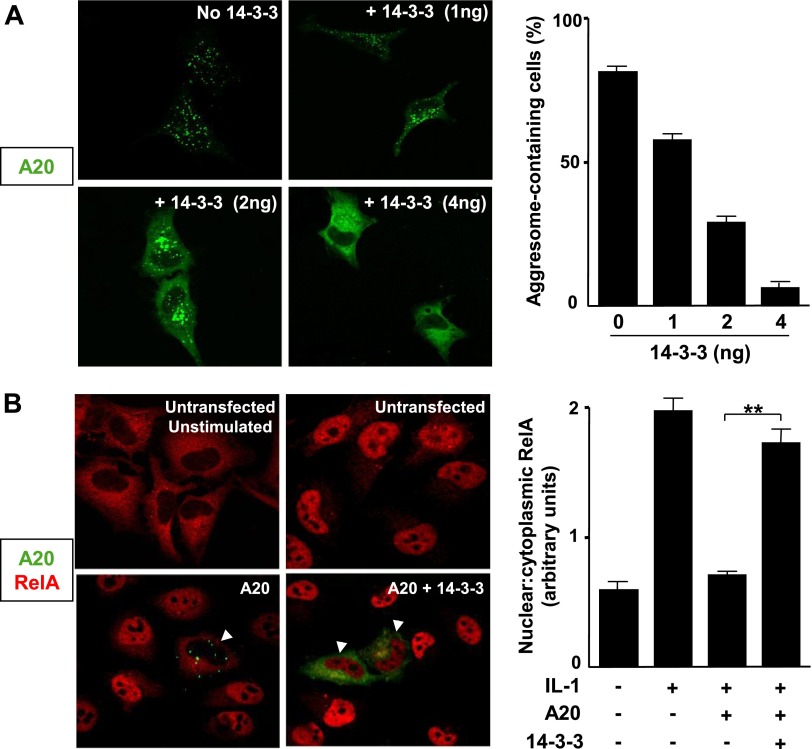

Punctate localization of A20 is required for its ability to inhibit NF-κB activation

We sought an alternative mechanism for A20’s suppressive effect on NF-κB activation by mapping the regions of A20 required for this function. We tested a series of C-terminal truncation mutants of A20 for their ability to regulate NF-κB. Reporter gene assays in MEFs revealed that native A20 (1–775) reduced NF-κB activity more effectively than the 1–712 truncated form (lacking the seventh zinc finger at the C terminus). Both of these forms displayed more activity than 1–468 and 1–366, mutants that, respectively, comprised the N terminus with 1 zinc finger and the N terminus alone (Supplemental Fig. S2A, B). Notably, the capability of A20 truncation mutants to suppress NF-κB correlated with their intracellular localization. Indeed, most active forms (1–775 and 1–712) localized to punctate bodies in the cytoplasm whereas less active forms (1–488 and 1–366) were diffusely expressed in the cytoplasm (Supplemental Fig. S2C). These data suggested that NF-κB suppression by A20 correlated with the formation of punctate structures. To determine whether a causal relationship exists between intracellular localization of A20 and its activity, we checked whether overexpression of the 14-3-3 chaperone, which is known to shuttle A20 from punctate bodies into a diffuse cytosolic compartment, influences the NF-κB inhibitory effect of GFP-A20 in HeLa cells (29) (Fig. 3A). Concomitant overexpression of 14-3-3 and GFP-A20 precluded the ability of A20 to inhibit nuclear translocation of NF-κB in response to IL-1 stimulation (Fig. 3B). This indicated that the punctate distribution of A20 is essential for the NF-κB inhibitory function of this protein.

Figure 3.

The punctate localization of A20 is required for NF-κB suppression. A) HeLa cells were transfected with pEGFP-A20 and with various amounts of FLAG-14-3-3. After 48 hours, cells were fixed before analysis of GFP-A20 (green) localization by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. The proportion of cells containing punctate A20 were calculated and pooled from 3 experiments, and mean values are shown with sd. B) HeLa cells were transfected with pEGFP-A20 (green) and were cotransfected with FLAG-14-3-3 (or with empty vector as a control). The intracellular localization of RelA (red) was assessed by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. Representative images and the proportion of RelA that localized to the nucleus (mean nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio ± sem) are shown.

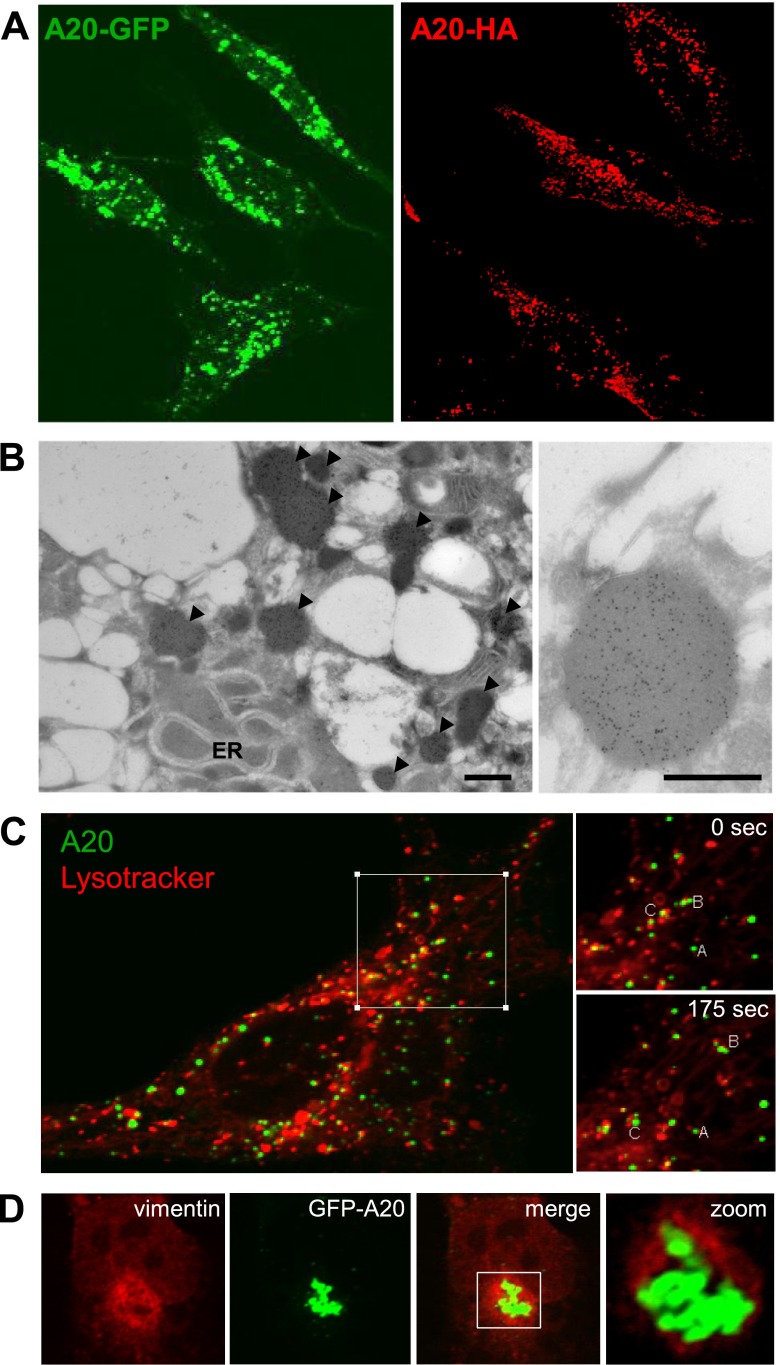

A20 punctate bodies are aggresomes

We verified that the punctate pattern of GFP-A20 expression was not an artifact of mere overexpression of a GFP-tagged protein by showing a similar pattern of expression for HA-tagged A20 (Fig. 4A). Moreover, we previously observed punctate endogenous A20 in primary ECs exposed to hypoxia followed by reoxygenation (28). Subsequent electron microscopy studies revealed that A20-stained particles were electron dense, varied in size between 0.5 and 1 nm, and were not surrounded by membranous structures (Fig. 4B). Dynamic imaging studies using Lysotracker demonstrated that, although A20 particles did not fully colocalize with lysosomes, they interacted and migrated in concert with them (Fig. 4C). These characteristics of high density, mobility, and lysosome binding suggested that the punctate A20 structures were likely aggresomes. Consistent with this hypothesis, A20 expressing bodies were often encircled by vimentin (Fig. 4D), a characteristic feature of aggresomes (30). Taken together, these data indicate that the active form of A20 localises to insoluble aggresomes that interact with lysosomes.

Figure 4.

A20 localizes to aggresomes. A) HeLa cells were transfected with pEGFP-A20 (green) or pHM6-A20 (red). The localization of A20 in transfected HeLa cells was determined by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy (HA-A20; red; right) or confocal microscopy (GFP-A20; green; left). B) HeLa cells transfected with pEGFP-A20 were stained using anti-GFP antibodies conjugated to gold and analyzed by scanning electronic microscopy. Representative images are shown, and aggresomes are indicated (arrows). C) HeLa cells transfected with 1 μg of GFP-A20 (green) were incubated for 1 hour with lysotracker probe (red) under growth conditions. The localization of lysosomes and GFP-A20 was then monitored in live cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Representative images are shown. Structures in the boxed region (labeled A, B, C) were tracked over 175 seconds to assess localization dynamics (right). D) HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-A20 (green). Intracellular localization of vimentin was assessed by immunofluorescent staining (red) and confocal microscopy. Colocalization images are representative of 2 independent experiments.

A20 targets signaling intermediaries to aggresomes

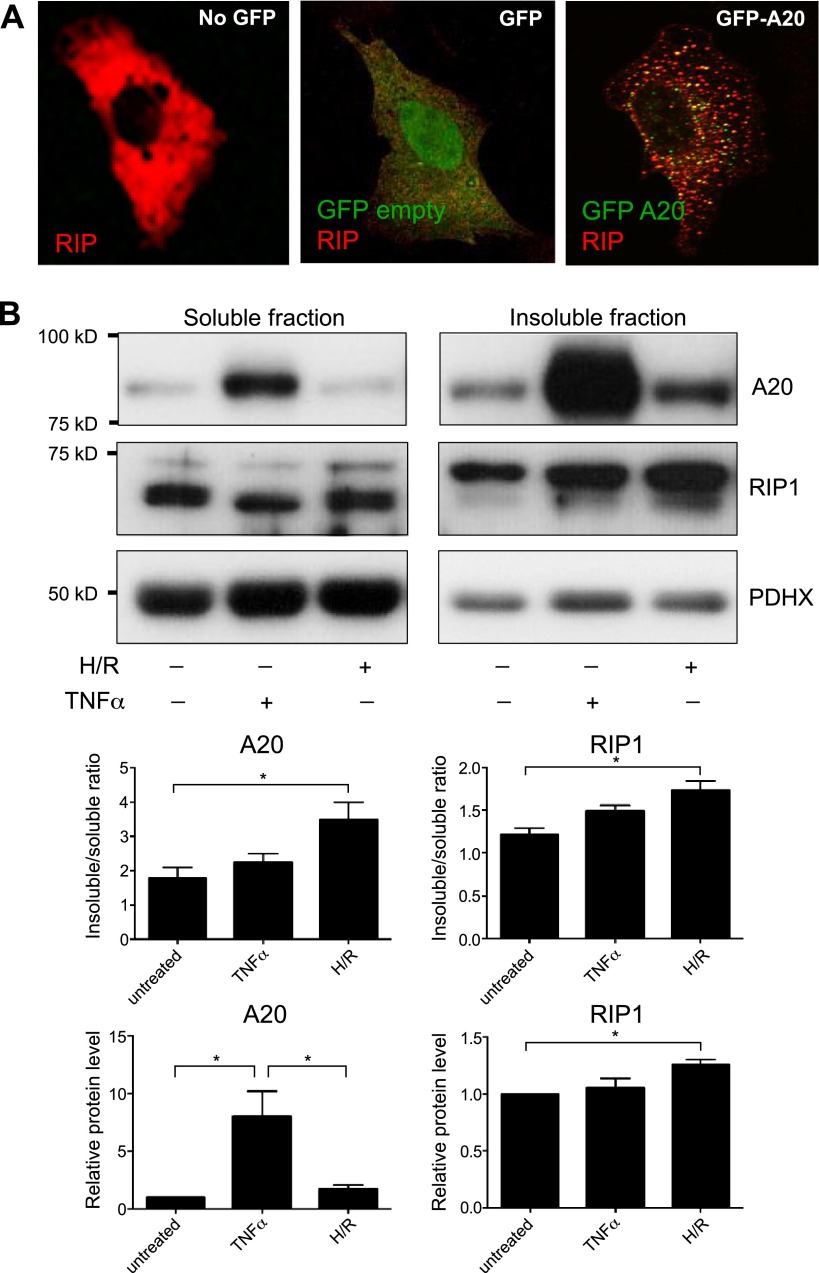

Because A20 interacts with RIP1, we examined whether these 2 proteins display an overlapping pattern of intracellular localization. Interestingly, RIP diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm in cells overexpressing GFP but was targeted to punctate bodies in GFP-A20–expressing cells (Fig. 5A). Quantitative analyses of multiple A20/RIP co-expression experiments demonstrated that A20 targets RIP to punctate structures in most cells, whereas coexpression of GFP with RIP did not alter RIP distribution (Supplemental Table S1). In addition, overexpression of A20 in HeLa cells also targeted TRAF6 and IKKγ signaling intermediaries to punctate structures (Supplemental Fig. S3; Supplemental Table S1). In contrast, A20 overexpression did not influence the localization pattern of a protein such as moesin that is irrelevant to the NF-κB pathway.

Figure 5.

A20 targets RIP1 to punctate structures in vitro and in vascular allografts in vivo. A) HEK293 cells were transfected with E-tagged RIP (red) and cotransfected either with an empty vector GFP (green; middle) or GFP-A20 (green; right). The intracellular localization of RIP1 was assessed by immunostaining using anti–E-tag antibodies (red) followed by confocal microscopy. Images shown are representative of those from 3 similar experiments. B) HUVECs were exposed to hypoxia (4 hours) followed by reoxygenation (4 hours; H/R) or were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 4 hours) or remained untreated. Triton-soluble (left) or -insoluble fractions (right) were tested by Western blotting using anti-A20, anti-RIP1, and by using anti-PDHX antibodies to assess total protein levels. Representative blots (upper) and results from densitometry analysis of 3 experiments (lower) are shown.

A series of experiments was performed to assess whether endogenous A20 and RIP1 can localize to insoluble aggresomes. Western blotting revealed that A20 was induced in HUVECs in response to hypoxia followed by reoxygenation and by TNF-α treatment (Fig. 5B) as described previously (7, 8, 28). Of particular note, a major proportion of the A20 pool localized to a Triton-insoluble fraction in untreated HUVECs and in cells exposed to TNF-α or hypoxia/reoxygenation, and the proportion of A20 localized to the insoluble fraction was significantly enhanced by exposure of HUVECs to hypoxia/reoxygenation (Fig. 5B, compare left and right panels). RIP1 was localized to soluble and insoluble compartments in untreated cells (in approximately equal proportions), and the proportion of insoluble RIP1 was enhanced by exposure to hypoxia/reoxygenation (Fig. 5B, compare left and right middle panels). By contrast, although the proportion of A20 and RIP1 that localized to the insoluble fraction was enhanced by TNF-α treatment, this difference was modest and did not reach statistical significance. Overall, these data suggest that endogenous A20 colocalizes with RIP1 at insoluble punctate structures in HUVECs exposed to physiologic stress.

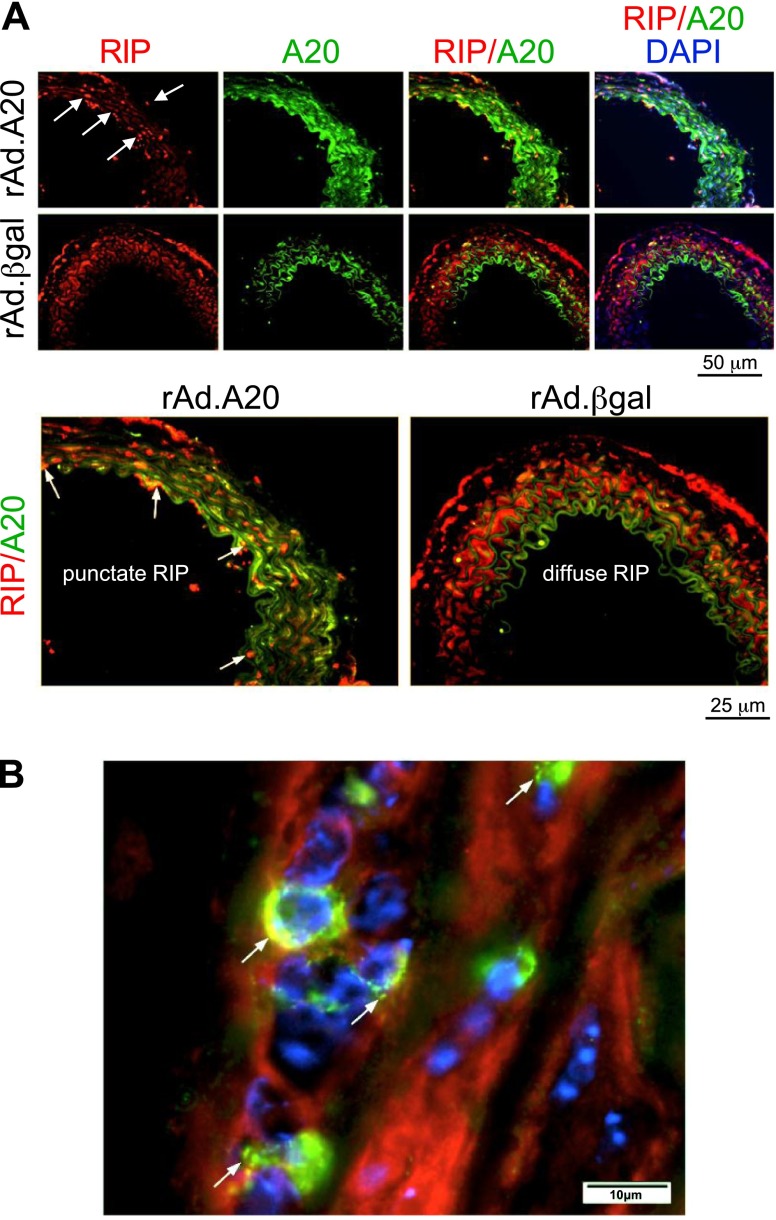

We also probed for A20 and RIP1 localization in vascular allografts treated with rAd.A20 (or rAd.βgal as a control). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that A20 was expressed at elevated levels in allografts treated with rAd.A20 (compared with rAd.βgal) and that total RIP1 expression was similar in vessels treated with rAd.A20 or rAd.βgal (Fig. 6). Importantly, RIP1 assumed a punctate pattern and colocalized with A20 in arteries treated with rAd.A20 (Fig. 6A, lower left, and B; see arrows), whereas it exhibited a diffuse intracellular localization in control allografts treated with rAd.βgal (Fig. 6, lower right). Thus, we conclude that A20 targets RIP1 to punctate bodies in vascular allografts, akin to cultured cells.

Figure 6.

A20 and RIP1 colocalize at punctate bodies in vascular allografts. Vascular allografts treated with rAd.A20 or rAd.βgal were harvested 2 days later (n = 3/group). Cross-sections were costained for RIP1 (red), A20 (green), and nuclei (DAPI; blue). A) Representative images are shown using ×40 magnification, and RIP1/A20 costaining is shown at higher magnification in the lower panels. Note that the majority of green signal in rAd.βgal-treated vessels is auto-fluorescence from the internal elastic lamina. B) Representative images are shown using ×40 magnification. Punctate A20/RIP1 colocalization appears yellow and is indicated (arrows).

RIP1 colocalization with A20 is enhanced by Ly63 polyubquitin chains

A previous report demonstrated that aggresomes contain Lys63-conjugated polyubiquitin chains (31). Given that A20 zinc fingers are known to bind Lys63 polyubiquitin (26), we investigated whether this interaction may contribute to A20 aggresome formation. By immunostaining and confocal microscopy, we demonstrated that A20 preferentially colocalized with a form of ubiquitin that generated Lys63 polyubiquitin chains (Ub-K63), but less effectively with wild-type ubiquitin or a form that cannot generate Lys63 chains (Ub-K63R; Supplemental Fig. S4). Ub-K63 also colocalized with RIP1, likely promoting its colocalization with A20, whereas Ub-K63R did not (Supplemental Fig. S5). These data suggest that Lys63 polyubiquitin chains promote localization of A20 and RIP1 in aggresomes.

DISCUSSION

A20 protects tissues, including organ allografts, from inflammation and injury, in part by inhibiting NF-κB activation (1–6). A previous report demonstrated that A20 suppresses NF-κB activation by mediating proteasomal degradation of RIP1 through catalyzing sequential deubiquitination of activating Lys63 polyubiquitin followed by Lys48 polyubiquitination (23). However, other reports suggest that A20 may regulate signaling to NF-κB via a noncatalytic mechanism involving interaction with polyubiquitin chains (26, 32–34). Here we demonstrated that exogenous A20 neither influences RIP1 expression in cultured vascular cells and vascular allografts in vivo nor requires its catalytic activities to suppress NF-κB nuclear localization and activation. Instead, we provide evidence for a novel mechanism by which A20 regulates inflammatory signaling through a noncatalytic process that involves targeting of RIP1 to insoluble aggresomes in a Lys63 polyubiquitin-dependent way. Remarkably, this sequestration process also affects other key NF-κB signaling intermediaries, namely TRAF6 and IKKγ. This would reduce their availability, resulting in signal interruption. That aggresomes redundantly sequester several key NF-κB signaling intermediaries speaks to the robustness of this system in optimizing the cell’s ability to control NF-κB inflammatory responses. It is intriguing that A20 can block NF-κB activation efficiently while targeting only a fraction of RIP1 and other intermediaries to insoluble aggresomes. However, this can be reconciled by the observation that A20 targets ubiquitinated forms of RIP1, TRAF6, and IKKγ, i.e., a fraction of the cellular pool that is critical for signaling to NF-κB.

Accumulation of aggresomes, also referred to as inclusion bodies, has previously been linked to several neuronal degenerative diseases (30, 35, 36). This is exemplified by Alzheimer disease, which is associated with a buildup of insoluble protein aggregates including amyloid-β peptide plaques and Tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles (37, 38). Physiologic stresses such as oxidative stress can promote the buildup of insoluble proteins by enhancing misfolding (thereby allowing abnormal protein-protein interactions) and by inhibiting the ubiquitin proteasome system (thereby reducing clearance of misfolded proteins) (30, 35, 36). The effects of aggresomes on cell viability and function can vary according to physiologic context. On one hand, aggresomes are known to protect cells from the potentially toxic effects of misfolded, typically polyubiquitinated, proteins. On the other, insoluble aggresomes have been shown to induce inflammation and apoptosis, which can promote pathologic processes (30, 35–38). We hypothesized that aggresomes may function during vascularized organ transplantation because they have been detected in tissues exposed to ischemia or hemodynamic stress (39, 40). Our data support this hypothesis by demonstrating aggresome-like structures in mouse vascular allotransplants and in primary cells exposed to physiologic stress. Similarly, a previous study had demonstrated that signaling molecules such as TRAF2 or RIP1/RIP3 form aggresomes or localize to insoluble aggregates when cells are under stress conditions such as heat (41) or are undergoing programmed necrosis (42). Because A20 is often part of the cellular response to injury, we wanted to explore its implication in aggresome formation and/or function. This quest was further fueled by A20 overexpression studies from our groups and others that uncovered a typical punctate distribution of A20 in intracellular inclusion bodies, including in ECs and SMCs. Our current study qualifies the protective abilities of aggresomes by demonstrating that they are not simply a depot for misfolded proteins or a backup system for defective or overwhelmed proteasomes, but also actively participate in the timely negative regulation of inflammation via the interruption of NF-κB signaling. Typically, polyubiquinated misfolded proteins are transported to aggresomes via microtubules and then are cleared by proteasomal or autophagy/lysosomal mechanisms (30, 35, 36). Our data demonstrating that A20 aggresomes interact and migrate with lysosomes support the latter scenario and are in keeping with previous studies suggesting that A20 localizes to a lysosome-associated compartment and can promote lysosomal degradation of TRAF2 protein (43). Accordingly, we propose that the fate of at least some proteins targeted to A20 aggresomes may be degradation via a lysosomal pathway.

Based on all the above, our working model is that A20 interrupts NF-κB signaling by capturing Lys63 polyubiquitinated signaling intermediaries and transporting them to insoluble aggresomes, thus reducing their bioavailability for downstream NF-κB signaling. This novel mechanism does not preclude other scenarios where A20 is able to destabilize signaling intermediaries such as RIP1 by promoting their Lys48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal processing. Alternative means by which A20 processes ubiquitinated proteins may vary with physiologic context. A20-mediated sequestration of Lys63- or linear-polyubiquitinated NF-κB signaling proteins in aggresomes as an alternative means to inhibit NF-κB may be a rescue path engaged by A20 in cells with impaired proteasomal activity and/or impaired deubiquitinating activity because of oxidative stress or overproduction of cellular proteins (Supplemental Fig. S6). In fact, members of the A20 family have been shown to be susceptible to reverse oxidation that alters catalytic activities (44, 45). This mechanism is particularly important in the context of severe ischemic stress, such as in transplanted organs that are exposed to prolonged ischemic periods and, as a result, harbor elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (46, 47). Our in vivo data strongly support this by demonstrating, for the first time, that an aggresome-dependent, noncatalytic mechanism of NF-κB inhibition by A20 is predominant in A20-expressing vascularized allografts. This concept is also supported by our studies of primary ECs showing that A20/RIP1 colocalize to insoluble punctate bodies in response to physiologic stress. Another potential contender for selecting whether A20-mediated inhibition of NF-κB would preferentially rely on its ubiquitin-editing or noncatalytic activities may be determined by cell type and stimulus specificity and/or by A20-interacting proteins. Indeed, although A20 binding and inhibitor of NF-κB-1 recruits A20 to Lys63 or linear ubiquitin chains, which could favor the noncatalytic mechanism of NF-κB inhibition by A20 (48), Tax1 binding protein 1 acts as a scaffold to promote the deubiquitination of RIP and TRAF6 by A20, hence favoring the 2-step process of sequential deubiquitination of activating Lys63-linked poyubiquitin chains followed by Lys48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (49). Future experiments should be undertaken to answer these questions and determine which, if any, of the A20 interacting proteins, namely inhibitor of NF-κB-1 and Tax1 binding protein 1, colocalizes with A20 to aggresomes, in which cells, and under which stimulus.

In summary, these data uncover a novel mechanism of NF-κB inhibition by A20 through sequestration of key Lys63 polyubiquitinated signaling molecules to aggresomes. This discovery highlights the versatile mechanisms initiated by the very potent NF-κB inhibitory protein A20 to contain inflammation. Importantly, this mechanism seems relevant to the anti-inflammatory function of A20 in vascular allografts in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Shuang Feng and Cleide G. da Silva for technical assistance. This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, United Kingdom (to P.C.E.), and U.S. National Institutes of Health R01 Grants HL080130 and DK063275 (to C.F.). H.P.M. was supported by Austrian Science Fund Grant J3398-BW23. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- EC

endothelial cell

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

human influenza hemagglutinin

- HCAEC

human coronary artery EC

- HCASMC

human coronary artery SMC

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- rAd.

recombinant adenovirus

- MEF

murine embryonic fibroblast

- RIP

receptor interacting protein

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- TAK

TGF activated kinase

- TRAF

TNF receptor associated factor

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunter U., Floege J., von Jürgensonn A. S., Stojanovic T., Merkel S., Gröne H. J., Ferran C. (2003) Expression of A20 in the vessel wall of rat-kidney allografts correlates with protection from transplant arteriosclerosis. Transplantation 75, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siracuse J. J., Fisher M. D., da Silva C. G., Peterson C. R., Csizmadia E., Moll H. P., Damrauer S. M., Studer P., Choi L. Y., Essayagh S., Kaczmarek E., Maccariello E. R., Lee A., Daniel S., Ferran C. (2012) A20-mediated modulation of inflammatory and immune responses in aortic allografts and development of transplant arteriosclerosis. Transplantation 93, 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V. I., Daniel S., Longo C. R., Shrikhande G. V., Scali S. T., Czismadia E., Groft C. M., Shukri T., Motley-Dore C., Ramsey H. E., Fisher M. D., Grey S. T., Arvelo M. B., Ferran C. (2006) A20, a modulator of smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis, prevents and induces regression of neointimal hyperplasia. FASEB J. 20, 1418–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu M. Q., Yan L. N., Gou X. H., Li D. H., Huang Y. C., Hu H. Y., Wang L. Y., Han L. (2009) Zinc finger protein A20 promotes regeneration of small-for-size liver allograft and suppresses rejection and results in a longer survival in recipient rats. J. Surg. Res. 152, 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grey S. T., Arvelo M. B., Hasenkamp W., Bach F. H., Ferran C. (1999) A20 inhibits cytokine-induced apoptosis and nuclear factor kappaB-dependent gene activation in islets. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1135–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damrauer S. M., Studer P., da Silva C. G., Longo C. R., Ramsey H. E., Csizmadia E., Shrikhande G. V., Scali S. T., Libermann T. A., Bhasin M. K., Ferran C. (2011) A20 modulates lipid metabolism and energy production to promote liver regeneration. PLoS ONE 6, e17715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach F. H., Ferran C., Hechenleitner P., Mark W., Koyamada N., Miyatake T., Winkler H., Badrichani A., Candinas D., Hancock W. W. (1997) Accommodation of vascularized xenografts: expression of “protective genes” by donor endothelial cells in a host Th2 cytokine environment. Nat. Med. 3, 196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper J. T., Stroka D. M., Brostjan C., Palmetshofer A., Bach F. H., Ferran C. (1996) A20 blocks endothelial cell activation through a NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18068–18073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferran C., Stroka D. M., Badrichani A. Z., Cooper J. T., Wrighton C. J., Soares M., Grey S. T., Bach F. H. (1998) A20 inhibits NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells without sensitizing to tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis. Blood 91, 2249–2258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H. Y., Rothe M., Goeddel D. V. (1996) The tumor necrosis factor-inducible zinc finger protein A20 interacts with TRAF1/TRAF2 and inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6721–6725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jäättelä M., Mouritzen H., Elling F., Bastholm L. (1996) A20 zinc finger protein inhibits TNF and IL-1 signaling. J. Immunol. 156, 1166–1173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarma V., Lin Z., Clark L., Rust B. M., Tewari M., Noelle R. J., Dixit V. M. (1995) Activation of the B-cell surface receptor CD40 induces A20, a novel zinc finger protein that inhibits apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12343–12346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2004) Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 18, 2195–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiDonato J. A., Hayakawa M., Rothwarf D. M., Zandi E., Karin M. (1997) A cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Nature 388, 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z. J. (2012) Ubiquitination in signaling to and activation of IKK. Immunol. Rev. 246, 95–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng L., Wang C., Spencer E., Yang L., Braun A., You J., Slaughter C., Pickart C., Chen Z. J. (2000) Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103, 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ea C. K., Deng L., Xia Z. P., Pineda G., Chen Z. J. J. (2006) Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol. Cell 22, 245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerlach B., Cordier S. M., Schmukle A. C., Emmerich C. H., Rieser E., Haas T. L., Webb A. I., Rickard J. A., Anderton H., Wong W. W., Nachbur U., Gangoda L., Warnken U., Purcell A. W., Silke J., Walczak H. (2011) Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature 471, 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabbe C., Husnjak K., Dikic I. (2011) The spatial and temporal organization of ubiquitin networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 295–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmukle A. C., Walczak H. (2012) No one can whistle a symphony alone - how different ubiquitin linkages cooperate to orchestrate NF-κB activity. J. Cell Sci. 125, 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans P. C., Smith T. S., Lai M. J., Williams M. G., Burke D. F., Heyninck K., Kreike M. M., Beyaert R., Blundell T. L., Kilshaw P. J. (2003) A novel type of deubiquitinating enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23180–23186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans P. C., Ovaa H., Hamon M., Kilshaw P. J., Hamm S., Bauer S., Ploegh H. L., Smith T. S. (2004) Zinc-finger protein A20, a regulator of inflammation and cell survival, has de-ubiquitinating activity. Biochem. J. 378, 727–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wertz I. E., O’Rourke K. M., Zhou H., Eby M., Aravind L., Seshagiri S., Wu P., Wiesmann C., Baker R., Boone D. L., Ma A., Koonin E. V., Dixit V. M. (2004) De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature 430, 694–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu T. T., Onizawa M., Hammer G. E., Turer E. E., Yin Q., Damko E., Agelidis A., Shifrin N., Advincula R., Barrera J., Malynn B. A., Wu H., Ma A. (2013) Dimerization and ubiquitin mediated recruitment of A20, a complex deubiquitinating enzyme. Immunity 38, 896–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shembade N., Ma A., Harhaj E. W. (2010) Inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling by A20 through disruption of ubiquitin enzyme complexes. Science 327, 1135–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skaug B., Chen J., Du F., He J., Ma A., Chen Z. J. (2011) Direct, noncatalytic mechanism of IKK inhibition by A20. Mol. Cell 44, 559–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Partridge J., Carlsen H., Enesa K., Chaudhury H., Zakkar M., Luong L. A., Kinderlerer A., Johns M., Blomhoff R., Mason J. C., Haskard D. O., Evans P. C. (2007) Shear stress acts as a switch to regulate divergent functions of NF-κB in endothelial cells: a potential novel mechanism for atheroprotection. FASEB J. 21, 3553–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutz J., Luong A., Strobl M., Deng M., Huang H., Anton M., Zakkar M., Enesa K., Chaudhury H., Haskard D. O., Baumann M., Boyle J., Harten S., Maxwell P. H., Pusey C., Heemann U., Evans P. C. (2008) The A20 gene protects kidneys from ischaemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing pro-inflammatory activation. J. Mol. Med. 86, 1329–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincenz C., Dixit V. M. (1996) 14-3-3 proteins associate with A20 in an isoform-specific manner and function both as chaperone and adapter molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20029–20034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopito R. R. (2000) Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olzmann J. A., Li L., Chudaev M. V., Chen J., Perez F. A., Palmiter R. D., Chin L. S. (2007) Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination targets misfolded DJ-1 to aggresomes via binding to HDAC6. J. Cell Biol. 178, 1025–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokunaga F., Nishimasu H., Ishitani R., Goto E., Noguchi T., Mio K., Kamei K., Ma A., Iwai K., Nureki O. (2012) Specific recognition of linear polyubiquitin by A20 zinc finger 7 is involved in NF-κB regulation. EMBO J. 31, 3856–3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhelst K., Carpentier I., Kreike M., Meloni L., Verstrepen L., Kensche T., Dikic I., Beyaert R. (2012) A20 inhibits LUBAC-mediated NF-κB activation by binding linear polyubiquitin chains via its zinc finger 7. EMBO J. 31, 3845–3855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosanac I., Wertz I. E., Pan B., Yu C., Kusam S., Lam C., Phu L., Phung Q., Maurer B., Arnott D., Kirkpatrick D. S., Dixit V. M., Hymowitz S. G. (2010) Ubiquitin binding to A20 ZnF4 is required for modulation of NF-κB signaling. Mol. Cell 40, 548–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Mata R., Gao Y. S., Sztul E. (2002) Hassles with taking out the garbage: aggravating aggresomes. Traffic 3, 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran P. B., Miller R. J. (1999) Aggregates in neurodegenerative disease: crowds and power? Trends Neurosci. 22, 194–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kummer M. P., Heneka M. T. (2014) Truncated and modified amyloid-beta species. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 6, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riederer B. M., Leuba G., Vernay A., Riederer I. M. (2011) The role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 236, 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tannous P., Zhu H., Nemchenko A., Berry J. M., Johnstone J. L., Shelton J. M., Miller F. J. Jr., Rothermel B. A., Hill J. A. (2008) Intracellular protein aggregation is a proximal trigger of cardiomyocyte autophagy. Circulation 117, 3070–3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H., Li W., Ahmad M., Rose M. E., Miller T. M., Yu M., Chen J., Pascoe J. L., Poloyac S. M., Hickey R. W., Graham S. H. (2013) Increased generation of cyclopentenone prostaglandins after brain ischemia and their role in aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in neurons. Neurotox. Res. 24, 191–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim W. J., Back S. H., Kim V., Ryu I., Jang S. K. (2005) Sequestration of TRAF2 into stress granules interrupts tumor necrosis factor signaling under stress conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2450–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J., McQuade T., Siemer A. B., Napetschnig J., Moriwaki K., Hsiao Y. S., Damko E., Moquin D., Walz T., McDermott A., Chan F. K., Wu H. (2012) The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell 150, 339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li L., Soetandyo N., Wang Q., Ye Y. (2009) The zinc finger protein A20 targets TRAF2 to the lysosomes for degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Cell Res. 1793, 346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enesa K., Ito K., Luong A., Thorbjornsen I., Phua C., To Y., Dean J., Haskard D. O., Boyle J., Adcock I., Evans P. C. (2008) Hydrogen peroxide prolongs nuclear localization of NF-kappaB in activated cells by suppressing negative regulatory mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18582–18590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulathu Y., Garcia F. J., Mevissen T. E., Busch M., Arnaudo N., Carroll K. S., Barford D., Komander D. (2013) Regulation of A20 and other OTU deubiquitinases by reversible oxidation. Nat. Commun. 4, 1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García-Valdecasas J. C., Rull R., Grande L., Fuster J., Rimola A., Lacy A. M., Gonzalez F. X., Cugat E., Puig-Parellada P., Visa J. (1995) Prostacyclin, thromboxane, and oxygen free radicals and postoperative liver function in human liver transplantation. Transplantation 60, 662–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka M., Mokhtari G. K., Terry R. D., Balsam L. B., Lee K. H., Kofidis T., Tsao P. S., Robbins R. C. (2004) Overexpression of human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) suppresses ischemia-reperfusion injury and subsequent development of graft coronary artery disease in murine cardiac grafts. Circulation 110(11, Suppl 1)II200–II206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oshima S., Turer E. E., Callahan J. A., Chai S., Advincula R., Barrera J., Shifrin N., Lee B., Benedict Yen T. S., Woo T., Malynn B. A., Ma A. (2009) ABIN-1 is a ubiquitin sensor that restricts cell death and sustains embryonic development. Nature 457, 906–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iha H., Peloponese J. M., Verstrepen L., Zapart G., Ikeda F., Smith C. D., Starost M. F., Yedavalli V., Heyninck K., Dikic I., Beyaert R., Jeang K. T. (2008) Inflammatory cardiac valvulitis in TAX1BP1-deficient mice through selective NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 27, 629–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.