Abstract

The allergic diseases are complex phenotypes for which a strong genetic basis has been firmly established. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been widely employed in the field of allergic disease, and to date significant associations have been published for nearly 100 asthma genes/loci, in addition to multiple genes/loci for AD, AR and IgE levels, for which the overwhelming number of candidates are novel and have given a new appreciation for the role of innate as well as adaptive immune-response genes in allergic disease. A major outcome of GWAS in allergic disease has been the formation of national and international collaborations leading to consortia meta-analyses, and an appreciation for the specificity of genetic associations to sub-phenotypes of allergic disease. Molecular genetics has undergone a technological revolution, leading to next generation sequencing (NGS) strategies that are increasingly employed to hone in on the causal variants associated with allergic diseases. Unmet needs in the field include the inclusion of ethnically and racially diverse cohorts, and strategies for managing ‘big data’ that is an outcome of technological advances such as sequencing.

Keywords: allergic disease, genetics, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), genome-wide association study (GWAS), next-generation sequencing (NGS), epigenetics, transcriptome

INTRODUCTION

Coca and Cooke were the first to describe asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), allergic rhinitis (AR), food allergy, and urticaria as ‘phenomena of hypersensitiveness’ at the annual meeting of the American Association of Immunologists in 19221. Just prior to and following this discourse, there was considerable focus on the relative influence of the environment versus hereditary factors on allergic diseases, with family-based twin and migration studies providing the earliest and most compelling evidence for genetic contributions2–6. Studies on the prevalence of allergic traits in relation to family history demonstrated incremental increases in risk of developing asthma, AR, or AD with the presence of one or both parents with allergic disease, and greater than three times the risk if allergic disease occurred in more than one first degree relative7. To this date, and despite the dramatic technological advances that have led to the identification of hundreds of genetic variants in genes associated with asthma, AD, and to a lesser degree, food allergy and AR, a positive family history remains one of the most reliable tools for prognosis of allergic disease.

Approaches for disentangling the genetic basis for the allergic diseases have evolved as technological tools for the field of molecular genetics have progressed. With the introduction of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the 1980s, DNA fragments in the human genome could be amplified and then studied for variable fragment lengths of repeats, or ‘genetic fingerprinting’. With a catalog of microsatellite markers spanning the human genome, genome-wide linkage studies emerged as a robust approach for identifying genetic hot spots associated with complex traits. Nearly a dozen genome-wide linkage screens were performed on asthma and its associated phenotypes8–18, for which multiple chromosomal regions provided significant evidence for linkage. From several of these family-based linkage genome-wide screens, six novel asthma genes were identified by positional cloning18–23. Similarly, multiple linkage studies were performed for AD (summarized in Ref. 24) and AR25–29. It was frequently observed that loci overlapped across associated traits; for example, Daniels and colleagues observed overlapping linkage peaks with quantitative traits associated with asthma including total serum IgE, skin test index, and eosinophil counts, as well as atopy as a qualitative trait8. Alternatively, the multiethnic Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Asthma reported linkage peaks that were specific to different racial ethnic groups9.

With the publication of initial efforts in sequencing the human genome30,31, the opportunity to genotype markers directly in genes of interest was greatly expanded as polymorphisms were identified in the approximately 20,000 to 25,000 genes across the 3 billion chemical base pairs that make up human DNA. Relying upon one of the simplest of these polymorphisms, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and relatively simple structural variants, such as insertions/deletions and repeats, this advancement allowed researchers to expand genetic studies beyond linkage toward the genetic association study design. For asthma alone, literally hundreds of candidate genes have been elucidated, and eloquently summarized elsewhere32–35, representing the relative success of this approach.

The GWAS Era

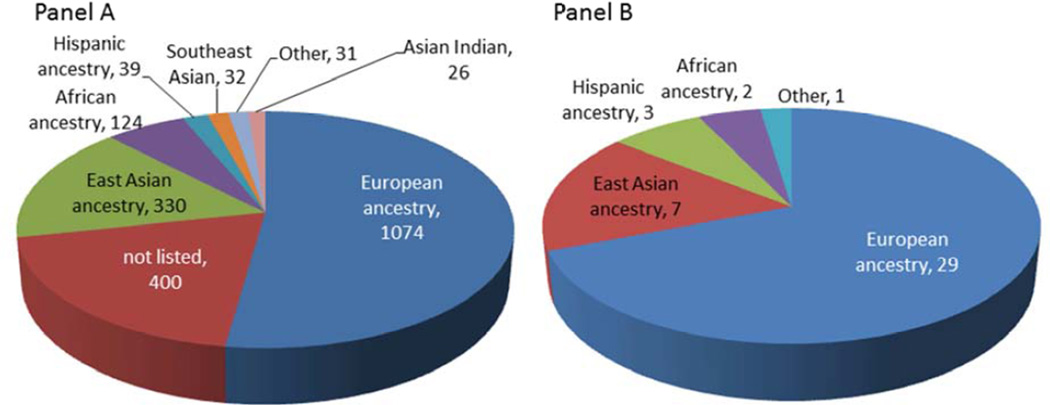

Following completion of the Human Genome Project, the International HapMap Project36–38 cataloged genomes representing four biogeographical groups (whites from the United States with northern and western European ancestry; Yorubans from Ibadan, Nigeria [YRI]; Han Chinese from Beijing, China [CHB]; and Japanese from Tokyo, Japan [JPT]) to advance the development of new analytic methods and investigating patterns of genetic variation. Simultaneously, the technological capacity to rapidly (and cheaply) genotype >1M common (>5%) SNPs on thousands of DNA samples from patients phenotyped for various complex clinical traits took the spotlight, and the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) era took off. The content of commercially available GWAS chips grew exponentially with expansion of the human genome catalog through the Thousand Genomes Project (TGP)39, and the capacity for discovery of genetic associations has likewise increased with the development of SNP genotype imputation methodologies40,41, whereby genotyped content from the chip can be combined with the >35M sequenced variants cataloged in the TGP. In the span of only seven years, over 1,924 publications and 13,403 SNPs associated with various complex and quantitative traits42,43 have been generated by GWAS (Figure 1, Panel A).

Figure 1.

Published genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to date according to ethnicity and race for all catalogued GWAS (Panel A) and asthma GWAS (Panel B). Data generated from the National Human Genome Research Institute’s GWAS catalog website (http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/).

GWAS has been widely employed in the field of allergic disease. While the precise number of GWAS are difficult to determine, approximately 40 asthma, three atopy, and three AD GWAS (plus a study of >30,000 AD patients genotyped on the Immunochip44) have been reported in the Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies42,43 (Figure 1, Panel B and summarized in Table 1). A major outcome of GWAS in allergic disease has been the formation of national and international collaborations leading to consortia meta-analyses, which has greatly facilitated gene discovery owed to the increased power generated from larger sample sizes (which are necessary to detect true associations while adjusting for the multiple comparisons). For example, the first asthma GWAS only showed a significant association between childhood onset asthma and markers near the ORMDL3 gene on chromosome 17q21 (P<10−12) among European populations45. When the study was expanded to include >26,000 cases and unaffected controls (e.g., the European-based GABRIEL Consortium46), five additional genes plus the 17q locus were strongly associated with asthma47. Following completion of 8 U.S.-based, independent asthma GWAS, the NHLBI-supported EVE Consortium was established, comprising >12,000 European American, African American and Hispanic cohorts plus >12,000 independent samples for replication48. More recently, the Transnational Asthma Genetics Consortium (TAGC) was formed to perform a global meta-analysis for asthma, and to date TAGC includes 67 cohorts representing nearly 20 studies spanning the globe, representing data on over 100,000 asthma cases, controls and family members (Demenais, Nicolae, et al, unpublished data).

It can be argued that the huge research efforts and expense committed to GWAS on allergic disease have confirmed suspected genes and pathways, some of which were the focus following linkage study discoveries and a result of the many candidate gene studies undertaken. However, GWAS has, for the most part, generated novel candidate genes and a new appreciation for the role of innate as well as adaptive immune-response genes in allergic disease. In the European-based GABRIEL Consortium, six genes were strongly associated with asthma47, of which three (IL33, ST2, and the IKZF3-ZPBP2-GSDMB-ORMDL3 region on chromosome 17q21) were replicated in the EVE Consortium49. Independent GWAS have provided further support for these same loci50,51,52. One of the strongest signals from the combined meta-analysis was for IL1RL1 (summarized in the Supplementary Figure 11 in Ref. 48), even though the peak SNP differed across ethnic groups. The association between IL1RL1 SNPs among African samples was marginal, and might have been overlooked, but in light of evidence for association in other cohorts, IL1RL1 showed the strongest association overall (P=1.4×10−8).

Lessons learned from candidate gene and positional cloning studies included the specificity of genetic associations to sub-phenotypes of allergic disease. For example, two null mutations (R501X and 2282del4) in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG) are arguably the most consistently associated polymorphisms with risk of AD, but numerous studies have also implicated a role for these mutations in the development of other atopic diseases, such as asthma and rhinitis, suggesting generalizability of FLG mutations to the allergic diathesis. However, it has been argued that the ‘atopic march’ (e.g., the tendency for AD to precede asthma, food allergy and AR) and the fact that ∼70% of severe AD patients also have asthma and AR later in life can account for this overlap53. Similar observations have come from GWAS of allergic diseases. For example, the associations with the ORMDL3 locus has been strongest with childhood asthma54, and associations between SNPs in IL1RL1 and IL33 have been strongest for atopic asthma as opposed to non-atopic asthma50. From the GWAS performed total serum IgE levels, there has been relatively little overlap with genes contributing to risk of asthma (Table 1).

The Next Generation of Asthma Genetics

Despite its success, discoveries from GWAS to date have contributed relatively little to our understanding of the specific causal genetic mechanisms underlying allergic disease. For example, the cumulative genetic risk of the variants identified to date for asthma through GWAS (for which, among the allergic diseases, the most GWAS have been performed) is <15%35. This is thought to be due, at least in part, to the fact that the most strongly associated SNPs in GWAS are generally not ‘directly causal’, but most likely tag SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the true unobserved disease-causing SNPs. Moreover, the vast proportion of GWAS associations (>85%) involve variants in intergenic or intronic regions55, which is likely a consequence of the array design; i.e., GWAS arrays are based on tag SNPs for common variants, and coding/exonic variation tends in general to be rare and therefore poorly tagged by a common variant, in contrast to intronic and intergenic regions that have a spectrum of variation that is common. Disappointment in GWAS is compounded by a paradigm shift away from the common disease—common variant hypothesis56 towards the role of rare variants (unlikely to be identified by GWAS57) in non-Mendelian diseases58, particularly with the appreciation that rare variation constitutes the majority of polymorphisms across human populations39,59.

Resequencing genes in individuals with well-characterized phenotypes is an alternative approach to assess the contribution that both rare and common variants make to disease and overcome the limitations of GWAS. Until recently, Sanger termination sequencing60 was the only option for interrogating rare variants, but this approach is costly and cannot be done on a large scale. The emergence of massively parallel, second-generation DNA sequencing in 200561 has made resequencing an affordable tool to study genetic variation, and in the past several years has been increasingly used either as a targeted approach to follow-up on specific genetic regions or as an unbiased approach towards gene discovery either by whole exome (WES; ∼30 Mb total) or whole genome sequencing (WGS)62. While rare coding variants may have a greater functional impact than common variants, their analysis must consider the low frequency of any variant since it will reduce the power to infer statistical associations (i.e., insufficient numbers of copies of the rare variant allele in a typical dataset). However, this can be overcome by evaluating the collective frequency of rare, nonsynonymous variants within one or more genes, or for a pathway(s), or the functional impact of the discovered variations, such as nonsense substitutions, frameshifts, and splice-site disruptions, that have important a priori evidence compared to other types of changes (reviewed in Ref. 62).

To date, there are limited examples of the application of NGS technology to identify variants associated with risk of allergic disease, although efforts are underway. A recent example of success combined targeted array-based and in-solution enrichment with the SOLiD sequencing platform to accurately and simultaneously detect 161/170 mutations and deletions associated with primary immunodeficiency (PID) disorders 63. NGS has also been applied to the study of airway inflammation, including asthma. A study by Leung et al utilized the next-generation sequencing technique called Roche 454 pyrosequencing on peak asthma association signals found in a large consortium-based study in European white subjects and a small group of Chinese children, and found substantial variation in haplotype structures across the populations, thus supporting the notion of potential sequence variations of asthma loci across different ethnic populations 64. WES has been applied to a small family-based study65 as well as asthmatics selected at both ends of a phenotype distribution (those with extreme severity phenotypes) 66 with limited success, and a large WGS (>1,000 genomes) on asthma is currently underway67.

Measuring the Transcriptome in Allergic Disease and its Application to Genetic Studies

Whole genome gene expression profiling, or transcriptomics, is a robust approach towards the quantitative and qualitative characterization of RNA expressed in a biological system. Since the development of synthetic oligonucleotide microarray platforms in 200368, transcriptomic profiling has been widely applied in allergic disease. For asthma and its associated traits alone, dozens of studies focusing on whole blood and target cells of the immune system and tissue from the upper and lower airways have been performed using these conventional platforms (reviewed in Ref. 69).

The same robust NGS technology that has recently advanced genetics has similarly transformed transcriptomics. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a more powerful approach to interrogate the transcriptome compared to older microarray technology because of its smaller technical variation70 and higher correlation with protein expression71. RNA-Seq has virtually unlimited dynamic range and permits digital quantification of transcript abundance, assessment of transcript isoforms and alternative splicing72–74, and it allows for unbiased assembly of transcripts without relying on previous annotation (including non-coding RNAs). To date there are limited examples of applying RNA-Seq technology to allergic disease, but successes include the identification of transcriptomic changes in human airway smooth muscle (ASM) in asthmatics compared to non-asthmatics75 and the identification of genes differentially expressed in response to glucocorticosteroid exposure (CRISPLD276, FAM129A and SYNPO277).

While it is ideal to measure the transcriptome of a primary cell specific to the disease of interest (i.e., cells from lung tissue in asthma), this is challenging when considering the large number of samples required given the demands of power. Recently, however, studies have demonstrated the value of focusing on surrogate target tissues/cells in predicting gene expression in tissues/cells that are challenging to access in large numbers (i.e., lung tissue), which have the potential to significantly move the field forward. For example, Poole and colleagues used whole-transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) to demonstrate that the nasal airway epithelium mirrors the bronchial airway, and subsequent RNA sequencing of candidate airway biomarkers confirmed that children with asthma have an altered nasal airway transcriptome compared to healthy controls, and these changes are reflected by differential expression in the bronchial airway 78.

Differential gene expression in humans is heritable79,80 and GWAS of gene expression is an innovative approach for mapping functional non-coding variation. Referred to as expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping, this approach is predicated on the notion that abundance of a gene transcript (a quantitative trait) is directly modified by genetic polymorphisms in regulatory elements. The added value of eQTL is the ability to identify disease markers identified in GWAS that are also associated with gene transcripts, and several studies have integrated findings from asthma GWAS with cataloged genome-wide gene expression data81,82, which can result in a ‘gain in power’83. Because of limited access to human primary cell types from large populations, many of the human eQTL studies have focused on convenient and immortalized Epstein-Barr virus transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs)84–86, but this approach has had limited success in mapping eQTLs for more than a few of the known asthma genes. In one of the first asthma eQTL studies, SNPs associated with asthma in a subset of the GABRIEL sample were consistently and strongly associated (P<10−22) with transcript levels of ORMDL345. Hao and colleagues performed an eQTL analysis using lung samples from transplant patients to identify variants affecting gene expression in human lung tissue, then integrated their lung eQTLs with GWAS data from GABRIEL to determine that one of their strongest eQTLs was, similar to the eQTL in LCLs study, a SNP in the chr. 17q21 region82. Murphy et al87 identified common genetic variants influencing expression of 1,585 genes in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells from 200 asthmatics using conventional microarrays, but they acknowledged power was a major limitation. In mining a catalog of 285 published GWAS, however, they identified significant associations with variants in the ORMDL3 region. When performing tests for association on 6,706 cis-acting expression-associated variants (eSNPs) from a genome-wide eQTL survey of CD4+ T cells from asthmatics, the ORMDL3/GSDMB locus held up (P = 2.9 × 10−8)88.

Common Genes in Common Diseases

Several reports have found that allergic diseases such as asthma, rhinitis, conjunctivitis and dermatitis as well as allergic reactions to drugs and foods, are more common in patients with the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)89–92. Furthermore, bronchial asthma was found to be the most common cause of cough in a small cohort of SLE patients from Bangladesh93 and Taiwan94. In addition, the inflammatory gene tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) was found to be a common genetic risk factor for asthma, and autoimmune diseases juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and SLE95. In a more recent study, PCR-based genotyping identified four FCRL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with protection in either juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) or asthma, but no association was observed with childhood-onset SLE in male Mexican patients. The gene NRF2 has also been associated with various immunological pathologies including RA, acute lung injury, asthma, and emphysema96, among others. There is a long-standing observation of common genetic determinants for both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) identified both through candidate gene studies as well as GWAS97,98. Recently, Hardin and colleagues performed a GWAS focusing specifically on patients from the COPD Gene Study with both asthma and COPD, referred to as the COPD-asthma overlap syndrome, and identified associations with variants in genes (i.e., GPR65) unique to this sub-phenotype99. Finally, there is a large body of research associated with the ‘hygiene hypothesis’100 addressing the potential beneficial role of microbial exposures for later development of asthma and allergies. Specifically, the underlying immunological mechanisms and the type of infectious/microbial stimuli relevant to helminth infection (i.e., schistosomiasis) are the same mechanisms that promote the Th2-mediated response in allergic disease101,102, and common genetic mechanisms underlie both schistosomiasis and asthma have been reported from linkage and candidate gene studies102.

Other Omics and Allergic Disease

“Omics” refers to an experimental design in which large-scale datasets are acquired from a complete class of biomolecules with the aim of identifying the functional or pathological mechanisms of disease103. Such data-dense technologies include: (1) DNA in the context of complete genomics; (2) gene regulation technologies (epigenomics); (3) global protein and/or post-transcriptional modifications (proteomics); and (4) all cellular metabolites (metabolomics) 104.

Transcriptomics extended to microRNA is another burgeoning field. Several miRNAs have been identified as distinct profiles for the development and status of asthma, as well as other allergic phenotypes105,106. Approximately 200 miRNAs are known to be altered in steroid naïve asthmatics, establishing a link between abnormal miRNA expression in asthmatic patients and inflammation107–109. High-throughput data combined with sequence-based miRNA predictions have been successfully applied110–114, and more recently, a transcriptome study on miRNA-long non coding RNA interactions suggests better understanding of lung disease regulation and progression115. NGS has been utilized to study microRNA expression and interactions with the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway in primary human airway smooth muscle (HASM) cells116.

Concordance rates for asthma and allergies of only ∼50% among monozygotic twins suggest differences in exposure to environmental triggers are critical in disease expression2,117,118, and it has been demonstrated that genes and environmental factors contribute equally to asthma and its associated traits such as tIgE3. Similar to the other allergic diseases, the prevalence of asthma has increased dramatically within the 2–3 decades in relation to the deterioration of the environment, favoring a significant contribution of environmental factors119. Added to this complexity is the observation that associations with alleles at candidate genes and interactions between these genes might only be observed among certain subpopulations despite nearly identical environmental exposures and similar genetic backgrounds. For example, the CD14(-260)C>T variant was associated with low tIgE in school children living in urban/suburban Tucson, AZ120, but the opposite association was reported in a farming community121. Alternatively, it has been shown that this same variant depends on the dose of endotoxin from household dust among African-ancestry asthmatics living in the tropics122, suggesting the role of endotoxin in allergic disease may be due to the combination of susceptibility genes and exposure. A large body of evidence implicates in utero and early life environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure leads to impaired lung function and increased risk of asthma123–126, and ETS exposure increases strength of the association between markers in candidate genes and atopic asthma127–129. Indeed, environmental exposures such as smoking, air pollution and stress have been shown to cause changes in epigenetic modifications of genes as well as altered microRNA expression 130.

Immune responses in allergic disease are dominantly initiated by the release of cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL4), IL5 and IL13, which activate type 2 helper T cells (TH2) resulting in a decrease of TH1 cytokines and impaired regulatory T cell function, and up or down regulation of DNA methylation on Th-1/Th-2 cytokine genes may affect the sensitization of experimental asthma131. In addition, epigenetic changes in immune cells such as T cells, B cells, mast cells and dendritic cells exposed to environmental factors have also been shown to be associated with asthma132. A recent study found that DNA methylation in the β-2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) gene is associated with decreased asthma severity133. In addition, an asthma mouse model found that microRNAs targeted genes involved in inflammatory responses and tissue remodeling, and demethylation status in the promoter of the IFN-γ changed in response to chronic antigen sensitization134.

Environmental stimuli have been shown to directly influence epigenetic modifications, and thus epigenetic regulation may play a role in immune-mediated lung diseases like asthma. Epigenetic regulation maintains tolerance to self-antigens. Thus, abnormal epigenetic activity may lead to a deregulated immune response and thus an immune disorder135. Epigenomics allows for the study of gene regulation at the chromosomal level using DNA methylation and CHIP technologies. As an example, 870 genes are differentially methylated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) tissues136, and changes in miRNAs and fibroblast signature for genes are known to regulate the extracellular matrix in IPF137,138. While methylation decreases gene expression, acetylation of histones relaxes chromatin facilitating gene transcription and increasing expression. A recent study has implicated histone modifications in the decrease of Fas expression as well as resistance to apoptosis in fibrotic lung fibroblasts139.

A novel example of this technology is a study in which methylated DNA immunoprecipitation-next generation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) on lung tissue DNA from saline and house dust mite (HDM)-exposed mice was performed and researchers found that chronic exposure to HDM increased airway reactivity and inflammation, as interpreted through increases in IL-4, IL-5 and serum IgE levels, resulting in structural remodeling and hyperresponsiveness consistent with allergic disease. In addition, mice that received HDM exposure had global changes in methylation and hydroxymethylation of approximately 213 genes, with TGFβ2 and SMAD3 having the most connected network140. These findings demonstrate how allergen exposure could trigger epigenetic changes in the lung genome.

Clinical Implications & Personalized Medicine

Arguably the ultimate goal of genetic studies of allergic disease is to better match individualized treatments to specific genotypes to improve therapeutic outcomes and minimize side effects. For example, despite the relative success of conventional asthma therapies such as inhaled beta agonists and glucocorticoids, most cause adverse side effects141–143 and a subset of asthmatics are refractory to anti-asthma therapies resulting in significant morbidity as well as a significant financial burden144–146. Genetic variation determines drug response through various mechanisms including pharmacodynamics mechanisms, which determine drug metabolism147.

Recent GWAS and studies of candidate genes related to the β2-adrenergic receptor pathway have attempted to identify specific variants associated with the response to inhaled beta agonists148–150. The Arg16 allele in ADRB2 has been associated with greater post-bronchodilator FEV1 response to SABA asthma therapy in asthmatic children151,152, while the Gly16 variant has been associated with changes in peak flow rate (PEFR)153–155. In contrast, the Arg16 allele has been associated with worsening asthma symptom scores with LABA therapy compared to Gly16 homozygotes 156. Other studies show no difference between the ADRB2 alleles and asthma symptoms after LABA therapy 157,158. Further pharmacogenetic studies may achieve a more definitive characterization of the role of Gly16Arg after beta agonist exposure and determine whether receptor kinetics or pro inflammatory effects play a role in the contrasting effects of the genotypes. Additional candidate genes found to be associated with altered beta agonist response in asthmatic children include ADCY9 150 and ARG1 159 with FEV1 change, and CRH2 148 and SPATS2L 149 with bronchodilator response. Additional candidate gene studies have also demonstrated altered asthma phenotypes in response to glucocorticoid therapies including CRH1 160, STIP1 161, TBX21 162,163, ADCY9150 164, and ORDML3 165.

Future Considerations/Summary

While GWAS has yielded promising results in the field of allergic disease, association does not imply biological functionality, and follow-up studies are needed to translate initial findings into the biological insights that ultimately will advance prognostics, diagnostics and therapeutics. While the vast amount of genomic data that is now available for a plethora of complex diseases, including allergic disease, has certainly facilitated follow-up association analyses to explore new hypotheses, meta-analyses, and replication of novel findings166, the scientific community is facing a ‘big data’ crisis167, as the size of genomic data sets today has begun to overwhelm the existing infrastructure and resources that allow researchers to share or use these data. For the genetics of allergic diseases specifically, there is increasing awareness of the need to design studies that are more inclusive of racially and ethnically diverse study participants168. Consider that, in the field of pharmacogenetics, it has been clearly demonstrated that, as an example, African American asthmatics have an increased likelihood for treatment failures and overall differential response to treatment that may be caused by genetic variants specific to their ancestry 169,170. Each of these needs will undoubtedly be addressed as clinicians and scientists in the field continue to move in a direction of collaboration and an appreciation for a multi-disciplinary approach, attributes that have already pushed the genetics of allergic disease into the genomic revolution, with promises of improved outcome for the patient.

KEY POINTS.

Nearly 100 asthma genes/loci in addition to multiple genes/loci for AD, AR and IgE have been identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

Next generation sequencing (NGS) strategies are increasingly being used to hone in on the causal variants associated with allergic diseases

A goal of the genetics of allergic disease is to better match individualized treatments to specific genotypes to improve therapeutic outcomes and minimize side effects

Acknowledgements

KCB was supported in part by the Mary Beryl Patch Turnbull Scholar Program. RAO was supported by NHLBI Diversity Supplement 3R01HL104608-02S1. The authors are grateful for technical assistance from Pat Oldewurtel and Joseph Potee.

Appendix A

A summary of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) performed on allergic diseases (p-values on the discovery sample p<10-5).

| Population | Location | Reported gene |

Adjacent gene (L,R) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | ||||

| European | 1p13.1 | IGSF3 | CD58, MIR320B1 | Ding et al 2013 1 |

| European | 1q25.3 | XPR1 | ACBD6, KIAA1614 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 1q44 | C1orf100 | CEP170, HNRNPU | Forno et al 20122 |

| European | 1q21.3 | IL6R | SHE, LOC101928101 | Ferreira et al 20113 |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 1q23.1 | PYHIN1 | IFI16, LOC646377 | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 1q21.3 | CRCT1 | LCE5A, LCE3E | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| European | 1q31.3 | DENND1B | CRB1, C10rf53 | Sleiman et al 20105 |

| Korean | 2p22.2 | CRIM1 | LOC10028911, FEZ2 | Kim et al 20136 |

| Korean | 2q36.2 | DOCK10 | CUL3, MIR4439 | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 2p22.1 | Intergenic | THUMPD2, SLC8A1-AS1 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 2q34 | CPS1 | LOC102724820, ERBB4 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 2p23.3 | ADCY3 | NCOA1, DNAJC27-AS1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 2p23.3 | ADCY3 | PTRHD1, DNAJC27 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 2p23.3 | EFR3B | DNAJC27, DNMT3A | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 2p23.3 | Intergenic | ADCY3, DNAJC27 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 2q12.1 | IL1RL1 | IL1R1, IL18RAP | Ramasamy et al 20128 |

| European | 2q33.1 | SPATS2L | TYW5, SGOL2 | Himes et al 20129 |

| European | 2q12.1 | IL1RL1, IL18R1 | IL1R2, IL18RAP | Wan et al 201210 |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 2q12.1 | IL1RL1 | IL1R1, IL18RAP | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| European | 2q12.1 | IL18R1 | IL1RL1, IL18RAP | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 3q13.2 | ATG3 | BTLA, SLC3A5 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 3p22.3 | Intergenic | LOC101928135, ARPP21 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 3q26.32 | Intergenic | LOC102724550, KCNB2 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 3q12.2 | ABI3BP | TFG, IMPG2 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 3p26.2 | IL5RA | CNTN4, LRRN1 | Forno et al 20122 |

| Korean | 4q26 | SYNPO2 | SEC24D, MYOZ2 | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 4q12 | Intergenic | IGFBP7, LPHN3 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 4p14 | KLHL5 | TMEM156, WDR19 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 4p15.1 | Intergenic | PCDH7, ARAP2 | Melen et al 20137 |

| Japanese | 4q31.21 | LOC729675 | INPP4B, USP38 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 4q31.21 | GAB1 | USP38, SMARCA5 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| European | 5q31.1 | C5orf56 | SLC22A5, IRF1 | Wan et al 201210 |

| European | 5q31.3 | NDFIP1 | GNPDA1, NDFIP1 | Wan et al 201210 |

| Japanese | 5q22.1 | TSLP | SLC25A46, WDR36 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 5q22.1 | TSLP | SLC25A46, WDR36 | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| European | 5q31.1 | SLC22A5 | LOC553103, C5orf56 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 5q31.1 | IL13 | RAD50, IL4 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 5q31.1 | RAD50 | IL5, IL13 | Li et al 201013 |

| European | 5q12.1 | PDE4D | RAB3C, PART1 | Himes et al 200914 |

| European | 6p21.1 | Intergenic | CDC5L, SUPT3H | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 6q21 | Intergenic | RFPL4B, LINC01268 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 6p12.3 | AL139097.1 | TFA2B, PKHD1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA1 | HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1 | Lasky-Su et al 201215 |

| Korean | 6p21.32 | HLA-DPB1 | HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB2 | Park et al 201316 |

| European | 6p21.32 | BTNL2 | HCG23, HLA-DRA | Ramasamy et al 20128 |

| European | 6q27 | T | LINC00602, PRR18 | Tantisira et al 201217 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | PBX2 | AGER, GPSM3 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | NOTCH4 | GPSM2, C6orf10 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | C6orf10 | NOTCH4, HCG23 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | BTNL2 | HCG23, HLA-DRA | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | HLA-DRA | BTNL2, HLA-DRB5 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQB1 | HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA2 | HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQB2 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | HLA-DOA | BRD2, HLA-DPA1 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | HLA-DPB1 | HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB2 | Noguchi et al 201118 |

| European | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQB1 | HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 7p15.3 | Intergenic | NPY, STK31 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 7q32.3 | MKLN1 | LINC-PINT, PODXL | Ding et al 20131 |

| Korean | 8q11.23 | OPRK1 | NPBWR1, ATP6V1H | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 8p12 | Intergenic | DUSP26, UNC5D | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 8q24.23 | COL22A1 | FAM135B, KCNK9 | Duan et al 201419 |

| Japanese | 8q24.11 | SLC30A8 | AARD, MED30 | Noguchi et al 201118 |

| Korean | 9p13.3 | TLN1 | TPM2, MIR6852 | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 9p23 | Intergenic | PTPRD-AS2, TYRP1 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 9q21.33 | Intergenic | ZCCHC6, GAS1 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 9p22.1 | SLC24A2 | ACER2, MLLT3 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 9q33.3 | DENND1A | CRB2, LHX2 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 9p21.1 | ACO1 | LINX01242, DDX58 | Wan et al 201210 |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 9p24.1 | IL33 | RANBP6, TPD52L3 | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| European | 9p24.1 | IL33 | RANBP6, TPD52L3 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| Mexican | 9q21.31 | TLE4, CHCHD9 | LOC101927450, LOC101927477 | Hancock et al 200920 |

| Korean | 9p21.3 | Intergenic | SLC24A2, MLLT3 | Kim SH et al 200921 |

| European | 10q24.2 | HPSE2 | HPS1, CNNM1 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 10q22.1 | PSAP | CDH23, CHST3 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 10p15.1 | PRKCQ | LOC399715, PRKCQ-AS1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 10q26.11 | EMX2 | PDZD8, RAB11FIP2 | Li et al 201322 |

| European | 10p15.1 | PRKCQ | LOC101927964, LINC00702 | Duan et al 201419 |

| European | 10q21.1 | PRKG1 | A1CF, PRKG1-AS1 | Ferreira et al 20113 |

| Japanese | 10p14 | LOC338591 | LINC00708, LOC101928272 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Korean | 10q21.3 | CTNNA3 | LOC101928913, | Kim SH et al 200921 |

| Korean | 11q24.1 | OR6X1 | ZNF202, OR6M1 | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 11q13.4 | P2RY2 | FCHSD2, P2RY2 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 11q24.2 | NR | LOC101929497, ETS1 | Forno et al 20122 |

| European | 11q13.5 | LRRC32 | C11orf30, GUCY2EP | Ferreira et al 20113 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 11q23.2 | C11orf71 | LOC101928940, RBM7 | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| Japanese | 12q13.2 | CDK2 | PMEL, RAB5B | Hirota et al 201112 |

| Japanese | 12q13.2 | IKZF4 | SUOX, RPS26 | Hirota et al 201112 |

| European | 13q13.1 | STARD13, RP11-81F11.3 | KL, RFC3 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 13q13.3 | NR | MIR548F5, DCLK1 | Forno et al 20122 |

| European | 13q21.31 | PCDH20 | MIR3169, LINC00358 | Ferreira et al 20113 |

| Korean | 13q12.13 | Intergenic | GPR12, USP12 | Kim SH et al 200921 |

| Korean | 14q32.2 | LOC730217 | C14orf64, C14orf177 | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 15q22.33 | SMAD3 | SMAD6, AAGAB | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 15q22.2 | RORA | LOC101928784, VPS13C | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 15q21.2 | SCG3 | DMXL2, LYSMD2 | Li et al 201013 |

| Korean | 16q23.3 | CDH13 | MPH0SPH6, MLYCD | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 17q21.32 | Intergenic | MIR196A1, PRAC1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 17q21.32 | Intergenic | MIR196A1, PRAC1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 17q12 | ORMDL3 | GSDMB, LRRC3C | Wan et al 201210 |

| European | 17p12 | NR | HS3ST3A1, COX10-AS1 | Forno et al 20122 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 17q12 | GSDMB | ZPBP2, ORMDL3 | Torgerson et al 20114 |

| European | 17q12 | ORMDL3 | GSDMB, LRRC3C | Ferreira et al 201123 |

| European | 17q12 | GSDMB | ZPBP2, ORMDL3 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 17q21.1 | GSDMA | LRRC3C, PSMD3 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 17q12 | ORMDL3 | GSDMB, LRRC3C | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | 18p11.31 | LPIN2 | EMILIN2, MYOM1 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 18p11.32 | YES1 | ENOSF1, ADCYAP1 | Li et al 201322 |

| Korean | 19q13.43 | ZNF71 | ZNF470, SMIM17 | Kim JH et al 20136 |

| European | 19p13.11 | IL12RB1 | AARDC2, MAST3 | Li et al 201322 |

| European | 19q13.42 | ZNF665 | ZNF347, ZNF818P | Wan et al 201210 |

| European | 20p12.3 | Intergenic | MIR8062, HA01 | Ding et al 20131 |

| European | 20q13.2 | Intergenic | LOC101927700, TSHZ2 | Melen et al 20137 |

| European | 20p13 | KIAA1271 | AP5S1, MAVS | Li et al 201013 |

| European | 22q13.31 | UPK3A | NUP50, FAM118A | Li et al 201322 |

| European | 22q12.3 | IL2RB | TMPRSS6, C1QTNF6 | Moffatt et al 201011 |

| European | NR | Intergenic | Wan et al 201210 | |

| Atopic Dermatitis | ||||

| European | 1q21.3 | FLG | HRNR, FLG2 | Weidinger et al 201324 |

| Chinese | 1q21.3 | FLG | HRNR, FLG2 | Sun et al 201125 |

| Japanese | 2q12.1 | IL1RL1, IL18R1, IL18RAP | IL1R1, IL18RAP, IL1R2 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 2q13 | LOC100505634 | BCL2L11, MIR4435-1 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 3p22.3 | GLB1 | CCR4, SUSD5 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 3q13.2 | CCDC80 | LINC01279, LOC101929694 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 5q31.1 | IL13 | RAD50, IL4 | Weidinger et al 201324 |

| Japanese | 5q31.1 | IL13 | RAD50, IL4 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 5q31.1 | IL13 | RAD50, IL4 | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| European | 6p21.33 | TNXB | CYP21A2, ATF6B | Weidinger et al 201324 |

| Japanese | 6p21.33 | HLA-C | HCG27, HLA-B | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | GPSM3 | PBX2, NOTCH4 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 6p21.32 | C6orf10 | NOTCH4, HCG23 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 6p21.33 | BAT1 | MCCD1, DDX39B | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| Japanese | 7p22.2 | CARD11 | GNA12, SDK1 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 8q24.21 | MIR1208 | PVT1, LINC00977 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 8q21.13 | ZBTB10 | MIR5708, ZNF704 | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| Japanese | 10q21.2 | ZNF365 | LOC283045, EGR2 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 10q21.3 | ADO, EGR2 | ZNF365, NRBF2 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 11q13.5 | C11orf30 | LOC100506127, LRRC32 | Weidinger et al 201324 |

| Japanese | 11p15.4 | OR10A3, NLRP10 | OR10A3, NLRP10 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 11q13.5 | C11orf30 | LOC100506127, LRRC32 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| Japanese | 11q13.1 | OVOL1 | AP5B1, SNX32 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 11q13.1 | OVOL1 | AP5B1, SNX32 | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| European | 11q13.5 | C11orf30 | LOC100506127, LRRC32 | 200928 |

| Japanese | 16p13.13 | CLEC16A | DEXI, SOCS1 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 19p13.2 | ACTL9 | ADAMTS10, OR2Z1 | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| Japanese | 20q13.2 | CYP24A1, PFDN4 | CYP24A1, PFDN4 | Hirota et al 201226 |

| European | 22q12.3 | NCF4 | PVALB, CSF2RB | Paternoster et al 201227 |

| Atopy | ||||

| European | 2p21 | SGK493 | C2orf91, PKDCC | Castro-Giner et al 200929 |

| Allergic Rhinitis | ||||

| European | 1p36.13 | CROCC | MIR3675, MFAP2 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 5q22.1 | TMEM232, SLCA25A46 | LOC100289673, TSLP | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 5q22.1 5q23.1 | TSLP | SLC25A46, WDR36 LOC101927190, | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | SEMA6A | LOC102467223 | Ramasamy et al 201130 | |

| European | 7p14.1 | GLI3 | INHBA-AS1, LINC01448 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| 11q13.5 | C11orf30, | LOC100506127, | ||

| European | LRRC32 | GUCY2EP | Ramasamy et al 201130 | |

| European | 14q23.1 | PPM1A, DHRS7 | PCNXL4, C14orf39 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 16p13.13 | CLEC16A | DEXI, SOCS1 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 20p11.21 | ENTPD6 | LOC101926889, PYGB | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| Total & Specific IgE | ||||

| European | 1p32.3 | EPS15 | TTC39A, OSBPL9 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 1q23.2 | DARC | CADM3-AS1, ACKR1 | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 1q23.2 | FCER1A | ACKR1, OR10J3 | Weidinger et al 200832 |

| European | 1q23.2 | FCER1A | Mus Olfr418-ps1, | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 1q23.2 | OR10J3 | FCER1A, OR10J1 | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 1q25.2 | ABL2 | TOR3A, SOAT1 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| Korean | 2p22.2 | CRIM1 | LOC100288911, FEZ2 | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 2p25.1 | ID2 | LOC100506299, MBOAT2 | Granada et al 201231 |

| Korean | 2q36.2 | DOCK10 | CUL3, NYAP2 | Kim et al 20136 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 3p14.1 | SUCLG2 | MIR4272, SUCLG2-AS1 | Levin et al 201333 |

| European | 3q22.1 | TMEM108 | NPHP3-AS1, BFSP2 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 3q28 | LPP | BCL6, TPRG1-AS1 | Granada et al 201231 |

| Korean | 4q26 | SYNPO2 | SEC240, MYOZ2 | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 4q27 | IL2 | ADAD1, IL21 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 5p15.2 | DNAH5 TMEM232, | LINC01194, TRIO | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 5q22.1 | SLCA25A46 | LOC100289673, TSLP | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 5q31.1 | IL13 | BC042122, IL4 | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 5q31.1 | RAD50 | IL5, IL13 | Weidinger et al 200832 |

| European | 6p21.32 | HLA region | HLA-DQB1, HLADQA2 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| European | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA2 | HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQB2 | G ranada et al 201231 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA2 | HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQB2 | Levin et al 201333 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQB1 | HLA-DQA1, HLADQA2 | Levin et al 201333 |

| European | 6p22.1 | HLA-G | LOC554223, HLA-H | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 6p22.1 | HLA-A | HCG4B, HCG9 | Granada et al 201231 |

| Korean | 8q11.23 | OPRK1 | NPBWR1, ATP6V1H | Kim et al 20136 |

| Korean | 9p13.3 | TLN1 | TPM2, CREB3 | Kim et al 20136 |

| Korean | 11q24.1 | OR6X1 | ZNF202, ORM1 | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 12q13.3 | STAT6, NAB2 | TMEM194A, LRP1 | Granada et al 201231 |

| Korean | 14q32.2 | LOC730217 | C14orf64, C14orf177 | Kim et al 20136 |

| European | 16p12.1 | IL4R | FLJ21408, IL21R | Granada et al 201231 |

| European | 16p13.2 | Intergenic | MIR548X, MIR7641-2 | Ramasamy et al 201130 |

| Mixed ethnicities | 16q22.1 | WWP2 | NOB1, PDXDC2P | Levin et al 201333 |

| Korean | 16q23.3 | CDH13 | MPHOSPH 6, LOC102724163 | Kim et al 20136 |

| Korean | 19q13.43 | ZNF71 | ZNF470, SMIM17 | Kim et al 20136 |

| Airway hyperresponsiveness | ||||

| European | 2q36.3 | AGFG1 | TM4SF20, C2orf83 | Himes et al 201334 |

Mixed ethnicities = African American/African Caribbean, Latino, European ancestry

References for Table 1

- 1.Ding L, et al. Rank-based genome-wide analysis reveals the association of ryanodine receptor-2 gene variants with childhood asthma among human populations. Hum Genomics. 2013;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forno E, et al. Genome-wide association study of the age of onset of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.020. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira MA, et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011;378:1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torgerson DG, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:887–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sleiman PM, et al. Variants of DENND1B associated with asthma in children. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:36–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, et al. A genome-wide association study of total serum and mite-specific IgEs in asthma patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melen E, et al. Genome-wide association study of body mass index in 23 000 individuals with and without asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:463–474. doi: 10.1111/cea.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramasamy A, et al. Genome-wide association studies of asthma in population-based cohorts confirm known and suggested loci and identify an additional association near HLA. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Himes BE, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in asthma subjects identifies SPATS2L as a novel bronchodilator response gene. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan YI, et al. Genome-wide association study to identify genetic determinants of severe asthma. Thorax. 2012;67:762–768. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffatt MF, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for adult asthma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:893–896. doi: 10.1038/ng.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, et al. Genome-wide association study of asthma identifies RAD50-IL13 and HLA-DR/DQ regions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.018. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Himes BE, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies PDE4D as an asthma-susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:581–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasky-Su J, et al. HLA-DQ strikes again: genome-wide association study further confirms HLA-DQ in the diagnosis of asthma among adults. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1724–1733. doi: 10.1111/cea.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park BL, et al. Genome-wide association study of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease in a Korean population. Hum Genet. 2013;132:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tantisira KG, et al. Genome-wide association identifies the T gene as a novel asthma pharmacogenetic locus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1286–1291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2061OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noguchi E, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies HLA-DP as a susceptibility gene for pediatric asthma in Asian populations. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan QL, et al. A genome-wide association study of bronchodilator response in asthmatics. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14:41–47. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock DB, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates chromosome 9q21.31 as a susceptibility locus for asthma in mexican children. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH, et al. Alpha-T-catenin (CTNNA3) gene was identified as a risk variant for toluene diisocyanate-induced asthma by genome-wide association analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies TH1 pathway genes associated with lung function in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.051. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira MA, et al. Association between ORMDL3, IL1RL1 and a deletion on chromosome 17q21 with asthma risk in Australia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:458–464. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidinger S, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4841–4856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun LD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Chinese Han population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:690–694. doi: 10.1038/ng.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirota T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/ng.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paternoster L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies three new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:187–192. doi: 10.1038/ng.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esparza-Gordillo J, et al. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro-Giner F, et al. A pooling-based genome-wide analysis identifies new potential candidate genes for atopy in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramasamy A, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis and grass sensitization and their interaction with birth order. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:996–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granada M, et al. A genome-wide association study of plasma total IgE concentrations in the Framingham Heart Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.029. e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weidinger S, et al. Genome-wide scan on total serum IgE levels identifies FCER1A as novel susceptibility locus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin AM, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for serum total IgE in diverse study populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1176–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himes BE, et al. ITGB5 and AGFG1 variants are associated with severity of airway responsiveness. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Coca AF, Cooke RA. On the classification of the phenomena of hypersensitiveness. Journal of Immunology. 1923;8:163–171. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffy DL, Martin NG, Battistutta D, Hopper JL, Mathews JD. Genetics of asthma and hay fever in Australian twins. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1990;142:1351–1358. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer LJ, Burton PR, James AL, Musk AW, Cookson WO. Familial aggregation and heritability of asthma-associated quantitative traits in a population-based sample of nuclear families. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2000 Nov;8(11):853–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manolio TA, Barnes KC, Beaty TH, Levett PN, Naidu RP, Wilson AF. Sex differences in heritability of sensitization to Blomia tropicalis in asthma using regression of offspring on midparent (ROMP) methods. Human Genetics. 2003 Oct;113(5):437–446. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis LR, Marten RH, Sarkany I. Atopic eczema in European and Negro West Indian infants in London. British Journal of Dermatology. 1961;73:410–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1961.tb14988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke RA, VanderVeer VA. Human sensitisation. Journal of Immunology. 1916;1:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dold S, Wjst M, Mutius Ev, Reitmeir P, Stiepel E. Genetic risk for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1992;67:1018–1022. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.8.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels SE, Bhattacharrya S, James A, et al. A genome-wide search for quantitative trait loci underlying asthma. Nature. 1996;383:247–250. doi: 10.1038/383247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CSGA. The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Asthma: A genome-wide search for asthma susceptibility loci in ethnically diverse populations. Nature Genetics. 1997;15(4):389–392. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ober C, Cox NJ, Abney M, et al. Genome-wide search for asthma susceptibility loci in a founder population. The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Asthma. Human Molecular Genetics. 1998 Sep;7(9):1393–1398. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malerba G, Trabetti E, Patuzzo C, et al. Candidate genes and a genome-wide search in Italian families with atopic asthmatic children. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 1999 Dec;29(Suppl 4):27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wjst M, Fischer G, Immervoll T, et al. A genome-wide search for linkage to asthma. German Asthma Genetics Group. Genomics. 1999 May 15;58(1):1–18. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dizier MH, Besse-Schmittler C, Guilloud-Bataille M, et al. Genome screen for asthma and related phenotypes in the French EGEA study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000 Nov;162(5):1812–1818. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.2002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ober C, Tsalenko A, Parry R, Cox NJ. A second-generation genomewide screen for asthma-susceptibility alleles in a founder population. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2000 Nov;67(5):1154–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62946-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokouchi Y, Nukaga Y, Shibasaki M, et al. Significant evidence for linkage of mite-sensitive childhood asthma to chromosome 5q31-q33 near the interleukin 12 B locus by a genome-wide search in Japanese families. Genomics. 2000 Jun 1;66(2):152–160. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laitinen T, Daly MJ, Rioux JD, et al. A susceptibility locus for asthma-related traits on chromosome 7 revealed by genome-wide scan in a founder population. Nature Genetics. 2001 May;28(1):87–91. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakonarson H, Bjornsdottir US, Halapi E, et al. A Major Susceptibility Gene for Asthma Maps to Chromosome 14q24. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002 Jul 15;71(3) doi: 10.1086/342205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Eerdewegh P, Little RD, Dupuis J, et al. Association of the ADAM33 gene with asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Nature. 2002 Jul 25;418(6896):426–430. doi: 10.1038/nature00878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen M, Heinzmann A, Noguchi E, et al. Positional cloning of a novel gene influencing asthma from chromosome 2q14. Nature Genetics. 2003 Nov;35(3):258–263. doi: 10.1038/ng1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laitinen T, Polvi A, Rydman P, et al. Characterization of a common susceptibility locus for asthma-related traits. Science. 2004 Apr 9;304(5668):300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1090010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolae D, Cox NJ, Lester LA, et al. Fine mapping and positional candidate studies identify HLA-G as an asthma susceptibility gene on chromosome 6p21. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:349–357. doi: 10.1086/427763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguchi E, Yokouchi Y, Zhang J, et al. Positional identification of an asthma susceptibility gene on human chromosome 5q33. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Jul 15;172(2):183–188. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1223OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Leaves NI, Anderson GG, et al. Positional cloning of a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 13q14 that influences immunoglobulin E levels and asthma. Nature Genetics. 2003 Jun;34(2):181–186. doi: 10.1038/ng1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes KC. An update on the genetics of atopic dermatitis: scratching the surface in 2009. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009 Jan;125(1):16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.008. e11-11; quiz 30-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haagerup A, Bjerke T, Schoitz PO, Binderup HG, Dahl R, Kruse TA. Allergic rhinitis - a total genome-scan for susceptibility genes suggests a locus on chromosome 4q24-q27. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2001 Dec;9(12):945–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokouchi Y, Shibasaki M, Noguchi E, et al. A genome-wide linkage analysis of orchard grass-sensitive childhood seasonal allergic rhinitis in Japanese families. Genes and Immunity. 2002 Feb;3(1):9–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurz T, Altmueller J, Strauch K, et al. A genome-wide screen on the genetics of atopy in a multiethnic European population reveals a major atopy locus on chromosome 3q21.3. Allergy. 2005 Feb;60(2):192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dizier MH, Bouzigon E, Guilloud-Bataille M, et al. Genome screen in the French EGEA study: detection of linked regions shared or not shared by allergic rhinitis and asthma. Genes Immun. 2005 Mar;6(2):95–102. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruse LV, Nyegaard M, Christensen U, et al. A genome-wide search for linkage to allergic rhinitis in Danish sib-pair families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012 Sep;20(9):965–972. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001 Feb 16;291(5507):1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001 Feb 15;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ober C, Hoffjan S. Asthma genetics 2006: the long and winding road to gene discovery. Genes Immun. 2006 Mar;7(2):95–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vercelli D. Discovering susceptibility genes for asthma and allergy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008 Mar;8(3):169–182. doi: 10.1038/nri2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ober C, Yao TC. The genetics of asthma and allergic disease: a 21st century perspective. Immunol Rev. 2011 Jul;242(1):10–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathias RA. Introduction to genetics and genomics in asthma: genetics of asthma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;795:125–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8603-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003 Dec 18;426(6968):789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005 Oct 27;437(7063):1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorisson GA, Smith AV, Krishnan L, Stein LD. The International HapMap Project Web site. Genome Res. 2005 Nov;15(11):1592–1593. doi: 10.1101/gr.4413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012 Nov 1;491(7422):56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Minimac. http://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/Minimac.

- 41.Auer PL, Johnsen JM, Johnson AD, et al. Imputation of exome sequence variants into population- based samples and blood-cell-trait-associated loci in African Americans: NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 Nov 2;91(5):794–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A catalog of published genome-wide association studies [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welter D, Macarthur J, Morales J, et al. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan 1;42(1):D1001–D1006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trynka G, Hunt KA, Bockett NA, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet. 2011 Dec;43(12):1193–1201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moffatt MF, Kabesch M, Liang L, et al. Genetic variants regulating ORMDL3 expression are determinants of susceptibility to childhood asthma. Nature. 2007;448(7152):470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature06014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.GABRIEL. A GABRIEL Consortium Large-Scale Genome-Wide Association Study of Asthma. http://www.cng.fr/gabriel/index.html.

- 47.Moffatt MF, Gut IG, Demenais F, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 23;363(13):1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torgerson D. Meta-analysis of Genome-wide Association Studies of Asthma in Ethnically Diverse North American Populations. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011 Sep;43(9):887–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gudbjartsson DF, Bjornsdottir US, Halapi E, et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2009 Mar;41(3):342–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferreira MA, McRae AF, Medland SE, et al. Association between ORMDL3, IL1RL1 and a deletion on chromosome 17q21 with asthma risk in Australia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010 Dec 8; doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011 Sep 10;378(9795):1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weidinger S, O'Sullivan M, Illig T, et al. Filaggrin mutations, atopic eczema, hay fever, and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 May;121(5):1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.014. e1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ono JG, Worgall TS, Worgall S. 17q21 locus and ORMDL3: an increased risk for childhood asthma. Pediatr Res. 2014 Jan;75(1–2):165–170. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown CD, Mangravite LM, Engelhardt BE. Integrative modeling of eQTLs and cis-regulatory elements suggests mechanisms underlying cell type specificity of eQTLs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reich DE, Lander ES. On the allelic spectrum of human disease. Trends Genet. 2001 Sep;17(9):502–510. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009 Oct 8;461(7265):747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Frazier ML, Spitz MR, Amos CI. Evolutionary evidence of the effect of rare variants on disease etiology. Clin Genet. 2011 Mar;79(3):199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marth GT, Yu F, Indap AR, et al. The functional spectrum of low-frequency coding variation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(9):R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shendure J, Porreca GJ, Reppas NB, et al. Accurate multiplex polony sequencing of an evolved bacterial genome. Science. 2005 Sep 9;309(5741):1728–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1117389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panoutsopoulou K, Tachmazidou I, Zeggini E. In search of low-frequency and rare variants affecting complex traits. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Oct 15;22(R1):R16–R21. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nijman IJ, van Montfrans JM, Hoogstraat M, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing: a novel diagnostic tool for primary immunodeficiencies. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 Feb;133(2):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leung TF, Ko FW, Sy HY, Tsui SK, Wong GW. Differences in asthma genetics between Chinese and other populations. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 Jan;133(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeWan AT, Egan KB, Hellenbrand K, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of a pedigree segregating asthma. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fu W, O'Connor TD, Jun G, et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013 Jan 10;493(7431):216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mathias RA, Huang L, O’Connor TD, et al. Patterns of genetic variation in populations of African ancestry observed in whole genome sequencing of 691 individuals from CAAPA. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2013 Abst 1966F. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaikh TH. Oligonucleotide arrays for high-resolution analysis of copy number alteration in mental retardation/multiple congenital anomalies. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2007 Sep;9(9):617–625. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318148bb81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sordillo J, Raby BA. Gene expression profiling in asthma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;795:157–181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8603-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marioni JC, Mason CE, Mane SM, Stephens M, Gilad Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 2008 Sep;18(9):1509–1517. doi: 10.1101/gr.079558.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fu X, Fu N, Guo S, et al. Estimating accuracy of RNA-Seq and microarrays with proteomics. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cullum R, Alder O, Hoodless PA. The next generation: using new sequencing technologies to analyse gene regulation. Respirology. 2011 Feb;16(2):210–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cloonan N, Grimmond SM. Transcriptome content and dynamics at single-nucleotide resolution. Genome Biol. 2008;9(9):234. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2009 Jan;10(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yick CY, Zwinderman AH, Kunst PW, et al. Gene expression profiling of laser microdissected airway smooth muscle tissue in asthma and atopy. Allergy. 2014 May 30; doi: 10.1111/all.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Himes BE, Jiang X, Wagner P, et al. RNA-Seq Transcriptome Profiling Identifies CRISPLD2 as a Glucocorticoid Responsive Gene that Modulates Cytokine Function in Airway Smooth Muscle Cells. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e99625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yick CY, Zwinderman AH, Kunst PW, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced changes in gene expression of airway smooth muscle in patients with asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 May 15;187(10):1076–1084. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1886OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poole A, Urbanek C, Eng C, et al. Dissecting childhood asthma with nasal transcriptomics distinguishes subphenotypes of disease. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 Mar;133(3):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.025. e612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schadt EE, Monks SA, Drake TA, et al. Genetics of gene expression surveyed in maize, mouse and man. Nature. 2003 Mar 20;422(6929):297–302. doi: 10.1038/nature01434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheung VG, Spielman RS. Genetics of human gene expression: mapping DNA variants that influence gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009 Sep;10(9):595–604. doi: 10.1038/nrg2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li B, Leal SM. Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet. 2008 Sep;83(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hao K, Bosse Y, Nickle DC, et al. Lung eQTLs to help reveal the molecular underpinnings of asthma. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(11):e1003029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li L, Kabesch M, Bouzigon E, et al. Using eQTL weights to improve power for genome-wide association studies: a genetic study of childhood asthma. Front Genet. 2013;4:103. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dixon AL, Liang L, Moffatt MF, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39(10):1202–1207. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stranger BE, Nica AC, Forrest MS, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39(10):1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Min JL, Taylor JM, Richards JB, et al. The use of genome-wide eQTL associations in lymphoblastoid cell lines to identify novel genetic pathways involved in complex traits. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murphy A, Chu JH, Xu M, et al. Mapping of numerous disease-associated expression polymorphisms in primary peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Dec 1;19(23):4745–4757. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharma S, Zhou X, Thibault DM, et al. A genome-wide survey of CD4 lymphocyte regulatory genetic variants identifies novel asthma genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Jun 13; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goldman JA, Klimek GA, Ali R. Allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus. IgE levels and reaginic phenomenon. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1976 Jul-Aug;19(4):669–676. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(197607/08)19:4<669::aid-art1780190403>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Diumenjo MS, Lisanti M, Valles R, Rivero I. [Allergic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus] Allergologia et immunopathologia. 1985 Jul-Aug;13(4):323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sequeira JF, Cesic D, Keser G, et al. Allergic disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1993 Jun;2(3):187–191. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shahar E, Lorber M. Allergy and SLE: common and variable. Israel journal of medical sciences. 1997 Feb;33(2):147–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Azad AK, Islam N, Islam MA, Islam MS, Barua R, Haq SA. Cough in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2013 Apr;22(2):300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shen TC, Tu CY, Lin CL, Wei CC, Li YF. Increased risk of asthma in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014 Feb 15;189(4):496–499. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1792LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jimenez-Morales S, Velazquez-Cruz R, Ramirez-Bello J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is a common genetic risk factor for asthma, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Mexican pediatric population. Human immunology. 2009 Apr;70(4):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005 Jul 4;202(1):47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Boezen HM, Koppelman GH. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: common genes, common environments? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jun 15;183(12):1588–1594. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1796PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yao TC, Du G, Han L, et al. Genome-wide association study of lung function phenotypes in a founder population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Aug 6; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hardin M, Cho M, McDonald ML, et al. The clinical and genetic features of COPD-asthma overlap syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2014 May 29; doi: 10.1183/09031936.00216013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. British Medical Journal. 1989 Nov 18;299(6710):1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002 Jul;2(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]