Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ is critical to the central clock of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). However, the role of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) homeostasis in the SCN is unknown. Here we show that NCX is an important mechanism for somatic Ca2+ clearance in SCN neurons. In control conditions Na+-free solution lowered [Ca2+]i by inhibiting TTX-sensitive as well as nimodipine-sensitive Ca2+ influx. With use of the Na+ ionophore monensin to raise intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i), Na+-free solution provoked rapid Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX. The peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i increase was larger during the day than at night, with no difference between dorsal and ventral SCN neurons. Ca2+ extrusion via forward NCX was studied by determining the effect of Na+ removal on Ca2+ clearance after high-K+-induced Ca2+ loads. The clearance of Ca2+ proceeded with two exponential decay phases, with the fast decay having total signal amplitude of ∼85% and a time constant of ∼7 s. Na+-free solution slowed the fast decay rate threefold, whereas mitochondrial protonophore prolonged mostly the slow decay. In contrast, blockade of plasmalemmal and sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ pumps had little effect on the kinetics of Ca2+ clearance. RT-PCR indicated the expression of NCX1 and NCX2 mRNAs. Immunohistochemical staining showed the presence of NCX1 immunoreactivity in the whole SCN but restricted distribution of NCX2 immunoreactivity in the ventrolateral SCN. Together our results demonstrate an important role of NCX, most likely NCX1, as well as mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in clearing somatic Ca2+ after depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx in SCN neurons.

Keywords: Ca2+ homeostasis, Ca2+ imaging, circadian rhythm, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, suprachiasmatic nucleus

na+/ca2+ exchanger (NCX) is an electrogenic antiporter that exchanges 3 Na+ for 1 Ca2+ in either forward (Ca2+ exit) mode or reverse (Ca2+ entry) mode (Blaustein and Lederer 1999). As such, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) activates the forward mode to extrude Ca2+ and an increase in intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) activates the reverse mode to uptake Ca2+. Three genes are known to encode three isoforms, NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 (Li et al. 1994; Nicoll et al. 1990, 1996), all of which have been found to express in the rat brain (Lee et al. 1994; Papa et al. 2003; Yu and Colvin 1997). While all three isoforms appear to have similar properties (Iwamoto and Shigekawa 1998; Linck et al. 1998), the isoform-specific distribution in different brain regions (Papa et al. 2003) and in different cell types (Thurneysen et al. 2002) suggests distinct functions for different isoforms.

The hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the central clock controlling circadian rhythms in mammals (Dibner et al. 2010). The SCN clock is synchronized by light information conveyed from the eye to the SCN via the glutamatergic retinohypothalamic tract (Golombek and Rosenstein 2010; Meijer and Schwartz 2003). SCN neurons exhibit a circadian rhythm in spontaneous firing rate (Green and Gillette 1982; Groos and Hendriks 1982; Inouye and Kawamura 1979; Shibata et al. 1982) and in [Ca2+]i (Colwell 2000; Enoki et al. 2012; Ikeda et al. 2003; Irwin and Allen 2009). In the mouse SCN, the rhythmic change in [Ca2+]i involves internal release (Ikeda et al. 2003) and is not altered or reduced by blockade of action potentials with TTX (Enoki et al. 2012; Ikeda et al. 2003). In the rat SCN, TTX eliminates the day-night variation in [Ca2+]i (Colwell 2000) or similarly lowers baseline Ca2+ ratio between day and night (Irwin and Allen 2009), suggesting an important contribution of action potential (voltage)-dependent transmembrane Ca2+ influx to basal [Ca2+]i. Indeed, transmembrane Ca2+ influx appears to be required for maintaining rhythmicity of the clock gene per1 in the rat SCN and of both per1 gene and PER2 protein in the mouse SCN (Lundkvist et al. 2005). Furthermore, glutamate-mediated phase shifts during the night critically depend on Ca2+ influx via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Irwin and Allen 2007; Kim et al. 2005) as well as ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling (Ding et al. 1998; Gillette and Mitchell 2002). These findings indicate a critical role of intracellular Ca2+ in maintaining circadian rhythmicity and mediating photic entrainment in the SCN. Nevertheless, it is not known whether and how NCX regulates [Ca2+]i in SCN neurons.

This study aimed to investigate the role of NCX in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in SCN neurons. Ratiometric Ca2+ imaging was used to study the effects of Na+-free solution on [Ca2+]i. We also used RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry to determine the expression and distribution of NCX isoforms. Part of the results have been presented in abstract form (Wang et al. 2012a).

METHODS

Hypothalamic brain slices and reduced SCN preparations.

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University. Sprague-Dawley rats (18–25 days old) were kept in a temperature-controlled room under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (light on 0700-1900). Lights-on was designated zeitgeber time (ZT) 0. For daytime and nighttime recordings, the animal was killed at ZT 2 and ZT 10, respectively. An animal was carefully restrained by hand to reduce stress and killed by decapitation with a small rodent guillotine without anesthesia, and the brain was put in an ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) prebubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. The ACSF contained (in mM) 125 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 10 glucose. A coronal slice (200–300 μm) containing the SCN and the optic chiasm was cut with a Vibroslice (Campden Instruments, Lafayette, IN) or a DSK microslicer (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) and was then incubated at room temperature (22–25°C) in the incubation solution, which contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, bubbled with 100% O2.

For electrical recordings and fluorescent Ca2+ and Na+ imaging, a reduced SCN preparation was obtained by excising a small piece of tissue (about one-ninth the size of SCN) from the medial SCN with a fine needle (catalog no. 26002-10, Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA), followed by further trimming down to 4–10 smaller pieces with a short strip of razor blade. The reduced preparation (containing tens of cells; see Fig. 1) was then transferred to a coverslip precoated with poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in a recording chamber for recording. The SCN neurons of the reduced preparation could be identified visually with an inverted microscope (Olympus IX70 and IX71). The preparation thus obtained allows rapid application of drugs (Chen et al. 2009) and has been used for fluorescent Na+ imaging (Wang et al. 2012b) and to demonstrate diurnal rhythms in both spontaneous firing and Na+-K+ pump activity (Wang and Huang 2004).

Fig. 1.

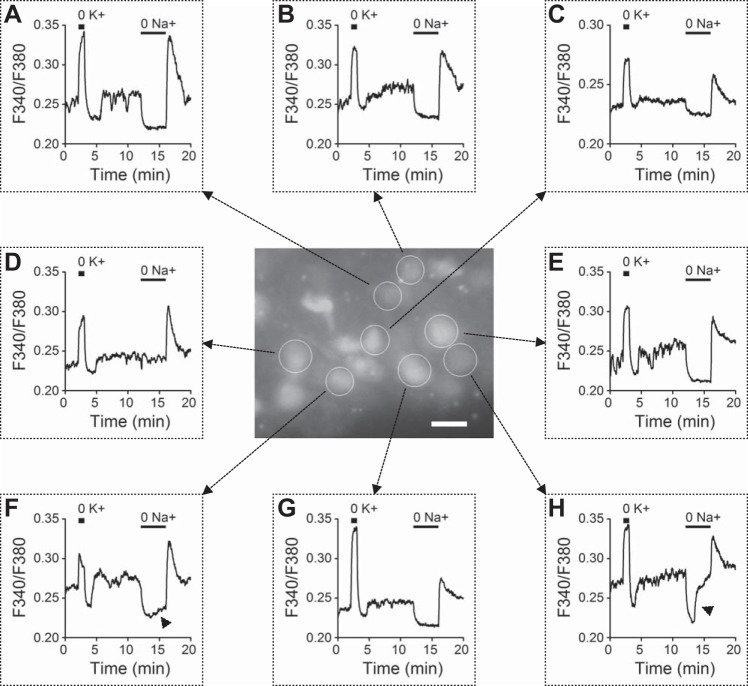

Effects of K+- and Na+-free solution on intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in a reduced suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) preparation. Center: fluorescence micrograph of a reduced SCN preparation loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (fura-2 AM). Regions of interest (ROIs) are indicated with circles. The image was taken in the resting condition. Scale bar, 20 μm. A–H: the time course of change in the F340-to-F380 fluorescence ratio recorded from 8 selected ROIs as indicated in center. Arrowheads (F and H) indicate the delayed increase in [Ca2+]i in Na+-free (0 Na+; Li+ substituted) solution. Similar results were obtained from 4 other experiments (n = 54 cells). Daytime recordings [zeitgeber time (ZT) 8].

Electrical recording.

The reduced SCN preparation was perfused with bath solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. All recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) at room temperature (22–25°C). The spontaneous firing rate was recorded in the cell-attached configuration. The patch electrode was filled with the bath solution or with the patch solution containing (in mM) 20 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 110 K-gluconate, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 3 Na-ATP, and 0.3 Na-GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. The spike counts, in 6-s epochs, always began only after stable recordings were made. At least 1 or 2 min of spontaneous firing rate was counted before the application of drugs. The signal was low-pass filtered at 1–5 kHz and digitized online at 2–10 kHz via a 12-bit A/D digitizing board (DT2821F-DI, Data Translation, Marlborough, MA) with a custom-made program written in the C language.

Ca2+ and Na+ imaging.

Fluorescent Ca2+ and Na+ imaging were performed by preloading the SCN neurons with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (fura-2 AM) (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985) or the Na+-sensitive fluorescent indicator sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate (SBFI-AM) (Harootunian et al. 1989; Minta and Tsien 1989). The reduced SCN preparation was incubated in 10 μM fura-2 AM or 15 μM SBFI-AM mixed with the nonionic surfactant Pluronic F-127 (0.02–0.04% wt/vol, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 50 μl of bath solution in the dark for 60 min at 37°C. Incubation was terminated by washing with 6 ml of bath solution, and at least 60 min was allowed for deesterification of the dye. All imaging experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). For the experiments, the reduced SCN preparation was gently pressed on the edge against the coverslip to allow adherence of the tissue to the surface. Fluorescence signals were imaged with a charge-coupled device camera (Olympus XM10) attached to an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71) and recorded with Xcellence imaging software integrated with the CellIR MT20 illumination system (Olympus Biosystems, Planegg, Germany). The system used a 150-W xenon arc burner as the light source to illuminate the loaded cells. The excitation wavelengths were 340 (±12) nm and 380 (±14) nm, and emitted fluorescence was collected at 510 nm. Pairs of 340/380-nm images were sampled at 0.2 Hz for Na+ and 0.5 Hz for Ca2+ signals. Ca2+ and Na+ levels in regions of interest (ROIs) were spatially averaged and presented by fluorescence ratios (F340/F380) after background subtraction. The average F340/F380 trace of Fig. 3A was smoothed by a moving average of nine successive points to reduce noise. Data were analyzed and plotted with custom-made programs written in Visual Basic 6.0 and the commercial software GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are given as means ± SE and were analyzed with Student's t-test and paired t-test or with ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test for comparison of selected pairs.

Fig. 3.

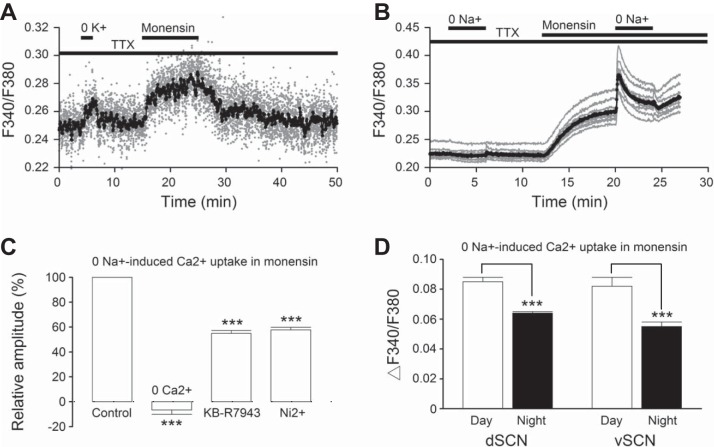

Zero Na+ in monensin induces rapid Ca2+ uptake via reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). A: effects of 0 K+ and 1 μM monensin on intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) (gray data points, smoothed averaged trace in black). Similar results were obtained from 3 other experiments (n = 40 cells). B: effects of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i in control and in the presence of 1 μM monensin. Gray traces, representative experiment; black trace, averaged. Note the rapid uptake of Ca2+ by 0 Na+ in the presence, but not absence, of monensin. C: statistics to show the relative peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake in control conditions (1 μM monensin), in 0 Ca2+, in 10 μM KB-R7943, and in 50 μM Ni2+. D: statistics showing the average peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake, the values being 0.085 ± 0.003 (n = 168 cells from 6 experiments), 0.064 ± 0.001 (n = 325 cells from 8 experiments), 0.082 ± 0.006 (n = 178 cells from 9 experiments), and 0.055 ± 0.003 (n = 251 cells from 7 experiments), respectively, for dorsal SCN (dSCN) neurons at day (ZT 4–11), dSCN at night (ZT 13–18), ventral SCN (vSCN) neurons at day, and vSCN at night. ***P < 0.001.

Drugs.

Stock solutions of monensin (10 mM in 100% ethanol), KB-R7943 (10 mM in DMSO), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; 1 mM in DMSO), thapsigargin (1 mM in DMSO), dantrolene (10 mM in DMSO), and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB; 100 mM in DMSO) were stored at −20°C and were diluted 10,000 or 1,000 times to reach desired final concentrations. Ni2+ and La3+ were directly added to the bath to achieve the final concentration. These chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, except for KB-R7943 and dantrolene, which were from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO) and Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel), respectively. Na+-free solutions were prepared with total replacement of extracellular Na+ with Li+ or N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+), Ca2+-free solutions were prepared with omission of extracellular Ca2+ and the addition of 1 mM EGTA, and high (50 mM)-K+ solutions were prepared with equal molar substitution of K+ for Na+.

RT-PCR analysis of NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 expression.

Total RNA of SCN was extracted with the Absolutely RNA Nanoprep kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's guide; total RNA of rat brain was purchased from BioChain Institute (Newark, CA). RNA samples were treated with DNase I for 13–15 min at 25°C to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The resulting RNA was reverse-transcribed (RT) to cDNA with ReverTra Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with oligo(dT) primers in a total volume of 20 μl. One-tenth of RT products were used as templates (2 μl) to perform PCR reaction. RT reaction with omission of reverse transcriptase was used as template for negative control PCR. Primers used for RT-PCR were as follows: NCX1 forward 5′-ACCACCAAGACTACAGTGCG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGGAAGCTGGTCTGTCTCC-3′, NCX2 forward 5′-GCGTGTGGGCGATGCTCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GACCTCGAGGCGACAGTTC-3′, and NCX3 forward 5′-CTGGAAGAGGGGATGACCC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTTTAGGGTGTTCACCCAATA-3′. The thermal cycling condition of RT-PCR was 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and then 72°C for 7 min. PCR amplified products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed.

Immunohistochemistry.

Sprague-Dawley rats (23–25 days old) were deeply anesthetized with Zoletil (40 mg/kg ip; Virbac Laboratories, Carros, France) and fixed by transcardial perfusion with PBS and then with 4% paraformaldehyde (500 ml/animal). Brains were removed and postfixed for at least 4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by dehydration with 30% sucrose in PBS for another 24 h. Twenty-micrometer-thick coronal sections through the hypothalamus region containing the SCN were cut on a cryostat (−20°C), collected in antifreeze solution, and stored in a −20°C freezer until further processing.

For immunohistochemical staining, sections (20 μm) were treated with 0.3% H2O2 for 15 min to quench endogenous peroxidase and then incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 2% serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and primary antibodies against NCX1 (mouse anti-NCX1, against epitope between amino acids 371 and 525 on intracellular side of plasma membrane, 1:100; AB2869, Abcam) (Markova et al. 2014) or NCX2 (goat anti-NCX2, against a peptide mapping within an extracellular domain of human origin, 1:1,000; SC-33528, Santa Cruz) (Engelhardt et al. 2013). After incubation with primary antibodies, sections were treated with respective biotinylated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (22–25°C). Sections were then rinsed in PBS and incubated in avidin-biotin complex (ABC Elite Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. After two 10-min washes in 0.1 M sodium acetate, sections were stained with diaminobenzidine. Sections were photographed and analyzed with an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71). Immunoreactivity for NCX1 or NCX2 was quantified by calculating the relative optical density with ImageJ 1.43u (NIH).

RESULTS

Na+-free solution induced variable [Ca2+]i responses in SCN neurons.

Ratiometric fluorescence recordings were performed to determine changes in [Ca2+]i when external Na+ was removed to block Ca2+ extrusion via forward NCX and/or to promote Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX. The experiment began with the application of K+-free solution to determine the condition of reduced preparations and to confirm that the cells being recorded were indeed neurons. The removal of extracellular K+ has been shown to block the Na+-K+ pump to depolarize the membrane potential and increase spontaneous firing of SCN neurons, followed by rebound hyperpolarization and inhibition of spontaneous firing on return to normal K+ (Wang et al. 2012b; Wang and Huang 2006). Figure 1 shows the effects of K+-free (0 K+) and Na+-free (0 Na+; Li+ substituted) solution on levels of [Ca2+]i in the SCN neurons in a reduced preparation. Figure 1, center, shows part of a reduced preparation isolated from the ventrolateral region of the SCN, with selected cells circled to represent the ROI for averaging fluorescence signals. The surrounding plots of F340/F380 (Fig. 1, A–H) indicate the change in [Ca2+]i. In all circled cells in Fig. 1, 0 K+ increased [Ca2+]i and then lowered [Ca2+]i below basal levels on return to normal K+, reminiscent of its effects on membrane potential and spontaneous firing in the SCN neurons (Wang et al. 2012b; Wang and Huang 2006). The result is consistent with previous findings that basal [Ca2+]i in rat SCN neurons is dependent on action potential-mediated Ca2+ influx (Colwell 2000; Irwin and Allen 2009). Interestingly, 0 Na+ decreased [Ca2+]i and return to normal Na+ produced rebound increase in [Ca2+]i. Note the gradual (Fig. 1F) and more marked (Fig. 1H) delayed increase in [Ca2+]i during the application of Na+-free solution.

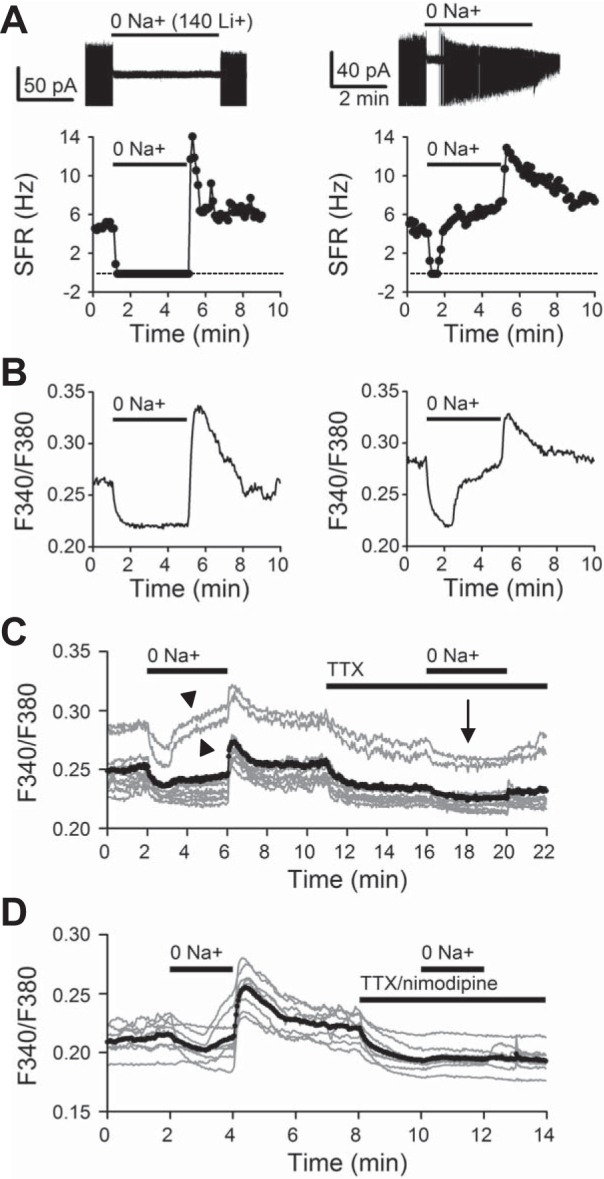

The results of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease and rebound [Ca2+]i increase on return to normal Na+ are opposite to what would be expected for 0 Na+-promoted reverse NCX to raise [Ca2+]i and Na+-promoted forward NCX to lower [Ca2+]i, respectively. This suggests that the effects of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i must be mediated by acting on targets more than the NCX. The important contribution of membrane potential- and action potential-mediated Ca2+ influx to basal [Ca2+]i prompted us to use cell-attached recordings to determine the effect of 0 Na+ on spontaneous firing. Figure 2A shows the results obtained from two representative SCN neurons. For both cells, the firing was completely inhibited upon the removal of Na+ (Fig. 2A, top). Nevertheless, the firing responses to more prolonged absence of Na+ (equal molar substitution of Li+ for Na+) differed between the two cells. The cell in Fig. 1A, top left, remained silent, and the cell in Fig. 1A, top right, resumed firing action potentials with decreasing amplitude and increasing frequency. Note that Li+ can permeate Na+ channels to generate action potentials. For a total of 33 cells, 42% (14/33) exhibited the latter type of firing response to 4-min application of Na+-free solution. The reason for the two different responses is not clear at this moment. Figure 1A, bottom, plots the time courses of change in the spontaneous firing rate. For comparison, Ca2+ signals from two cells shown in Fig. 1, A and H, are replotted in Fig. 2B. The resemblance of 0 Na+-induced alterations of spontaneous firing rate (Fig. 2A, bottom) and [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2B) suggests that the effect of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i was mediated by altering action potential-mediated Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 2.

Zero Na+ in control conditions lowers [Ca2+]i in SCN neurons. A: 2 representative cells showing the effects of 0 Na+ (equal molar substitution of Li+ for Na+) on spontaneous firing (top). Bottom: time course of change in spontaneous firing rate (SFR). B: 2 representative cells showing the effects of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i (from Fig. 1, A and H). Note the similar effects of 0 Na+ on SFR (A) and on [Ca2+]i. C: 0 Na+ effect on [Ca2+]i in control and in the presence of TTX. Note that TTX markedly reduced the magnitude of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease. D: 0 Na+ effect on [Ca2+]i in control and in the combined presence of 0.3 μM TTX and 20 μM nimodipine; the values of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease, being 0.012 ± 0.001 (n = 50 cells from 4 experiments) and 0.002 ± 0.000 (n = 50 cells from 4 experiments; P < 0.001, paired t-test), respectively. Gray traces, representative experiments; black trace, averaged. Daytime recordings (ZT 5–9).

To test this idea, we compared the effect of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i in control conditions and in the presence of 0.3 μM TTX to block the generation of action potentials. Figure 2C superimposes the [Ca2+]i responses thus obtained from a representative experiment (n = 10 cells). The result indicates that TTX, which lowered basal [Ca2+]i, blocked most of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease and eliminated delayed increase in [Ca2+]i (marked by arrowheads in Fig. 2C), leaving a small but sustained lowering effect on [Ca2+]i (marked by arrow in Fig. 2C). For a total of five experiments (n = 134 cells), 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease was 0.013 ± 0.001 in control conditions and reduced to 0.003 ± 0.000 in TTX (P < 0.001, paired t-test). The result suggests that 0 Na+ lowered [Ca2+]i by blocking both TTX-sensitive (action potential mediated) and TTX-resistant Ca2+ influx. Furthermore, the rebound [Ca2+]i increase on return to normal Na+ was virtually abolished by TTX, suggesting an origin of action potential-mediated Ca2+ influx. As the nimodipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels have been shown to play a role in maintaining basal [Ca2+]i (Irwin and Allen 2009), we suspected that these channels may mediate the TTX-resistant [Ca2+]i component. Indeed, the 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease was virtually eliminated in the combined presence of 0.3 μM TTX and 20 μM nimodipine (n = 8 cells; Fig. 2D). Together the results indicate that in control conditions 0 Na+ inhibited TTX-sensitive as well as nimodipine-sensitive Ca2+ influx but failed to promote significant Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX.

Na+-free solution induced Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX in monensin.

Two factors may be responsible for the inability of 0 Na+ to induce Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX in control conditions. First, internal Ca2+ is required for allosteric activation of NCX (DiPolo 1979; Hilgemann et al. 1992a), and as such the lowering of [Ca2+]i by 0 Na+ may prevent the activation of reverse NCX. Second, the lowering of [Na+]i during the application of Na+-free solution may also inhibit the reverse mode of NCX. Since increasing internal Na+ has been shown to reduce or eliminate the need for Ca2+ allosteric activation of NCX in intact cells (Urbanczyk et al. 2006), we investigated the effect of 0 Na+ on [Ca2+]i with the addition of the Na+ ionophore monensin to increase [Na+]i.

For the experiment, we compared the effects of 0 Na+ in control conditions and in elevated [Na+]i with 1 μM monensin. Figure 3A shows the increase in [Na+]i in response to 1 μM monensin (n = 10 cells). For comparison, K+-free solution was also applied for 2 min to transiently block the Na+-K+ pump to increase [Na+]i (see also Wang et al. 2012b). Figure 3B shows a typical experiment to demonstrate the ability of 0 Na+ to uptake Ca2+ in elevated [Na+]i with monensin (n = 9 cells). As expected, 0 Na+ in TTX slightly lowered basal [Ca2+]i. In contrast, in the presence of 1 μM monensin to raise [Na+]i, 0 Na+ rapidly increased [Ca2+]i. The 0 Na+-induced increase of [Ca2+]i inactivated during the 4-min period of Na+ removal, likely mediated by Na+-dependent inactivation of reverse NCX (Hilgemann et al. 1992b).

Pharmacological treatments commonly used for blocking reverse NCX-mediated Ca2+ uptake include the removal of external Ca2+ (0 Ca2+) and the addition of the isothiourea derivative KB-R7943 at low micromolar concentrations, which preferentially blocks the reverse mode of Ca2+ uptake catalyzed by NCX1 (Iwamoto et al. 1996; Watano et al. 1996). The divalent cation Ni2+ has also been shown to block Ca2+ uptake via NCX1 and NCX2 with an IC50 of ∼50 μM (Iwamoto and Shigekawa 1998). For the experiments, the peak magnitude of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i rise in monensin was determined before and after treatment with 0 Ca2+, 10 μM KB-R7943, or 50 μM Ni2+. Figure 3C summarizes the results. On average, the peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced [Ca2+]i rise was reduced from 100 ± 0.0% (n = 305 cells from 20 experiments) to −6.7 ± 3.5% (n = 95 cells from 5 experiments; P < 0.001, ANOVA), 54.9 ± 2.3% (n = 147 cells from 9 experiments; P < 0.001, ANOVA), and 57.7 ± 2.1% (n = 63 cells from 6 experiments; P < 0.001, ANOVA) in 0 Ca2+, 10 μM KB-R7943, and 50 μM Ni2+, respectively.

The ability of 0 Na+ to promote Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX in monensin allows us to use the peak amplitude as a measure of NCX activity. To determine whether there is a day-night variation in NCX activity, we compared the peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake in the presence of 1 μM monensin (∼10 min into the application) recorded during the day (ZT 4–11) and at night (ZT 13–18). Our results indicate a larger value of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake during the day than at night (F = 55.19, P <0.001, 2-way ANOVA), regardless of whether neurons were from the dorsal or the ventral SCN (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the amplitude of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake was similar between the two regions (F = 3.45, P = 0.06, 2-way ANOVA) irrespective of day or night. Together, the results suggest a diurnal rhythm in NCX activity in either dorsal or ventral SCN neurons but no regional variation in NCX activity.

Regulation of Ca2+ clearance by forward NCX.

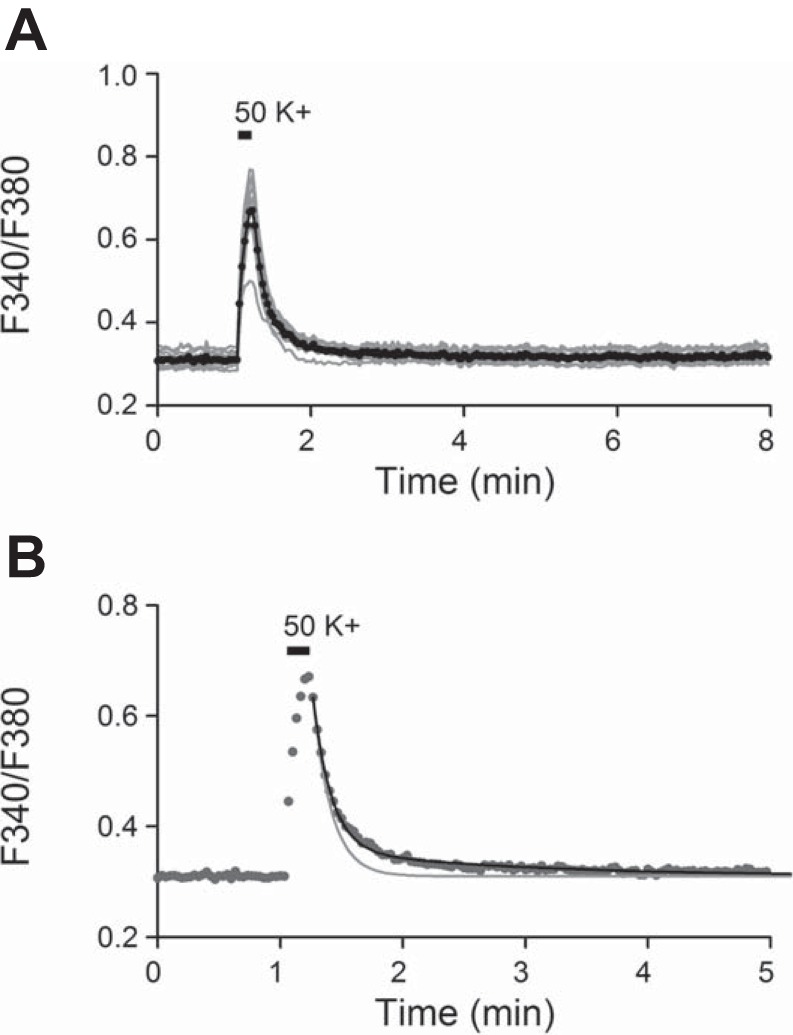

To determine the role of forward NCX in the regulation of [Ca2+]i in SCN neurons, we investigated the effect of Na+-free solution (Li+ or NMDG+ substituted) on Ca2+ clearance after depolarization-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. For the experiment, high-K+ (50 mM) solution was applied for 10 s to elicit Ca2+ transients. Figure 4A superimposes the [Ca2+]i responses thus obtained from a representative experiment (n = 10 cells). The result indicated a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i in response to high-K+ solution. The clearance of [Ca2+]i on return to control solution, which completed within several minutes, appeared to proceed with both a fast and a slow time course. Figure 4B replots the averaged Ca2+ response to determine the decay phases. The theoretic curve fitted to the average Ca2+ response was calculated with two exponential decay phases: A1 × exp(−t/τ1) + A2 × exp(−t/τ2), where A1 + A2 = 100%. For this particular experiment, the fast phase had total signal amplitude of 85% (A1) and a time constant of 9 s (τ1), and the slow phase had amplitude of 15% (A2) and a time constant of 1.6 min (τ2). The curve assuming only the fast decay phase (A1 = 100% and τ1 = 9 s) cannot account for the slow clearance of Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

High-K+-induced Ca2+ transient has both fast and slow decay components. A: effect of 50 mM K+ on [Ca2+]i from a representative experiment, with individual responses in gray and averaged response in black. B: Ca2+ clearance is better explained with 2 exponential decay phases as indicated by the theoretic black curve through the average data points (from A). The gray curve was calculated with only the fast exponential decay phase. Daytime recordings (ZT 7).

Figure 5A shows the average Ca2+ responses (n = 20 cells) to demonstrate the slowing effect of Na+-free solution on Ca2+ clearance after high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients. For the experiment, high-K+ solution was applied for 10 s to elicit Ca2+ transients followed by return to control solution (140 mM Na+; Fig. 5A, trace a) and to Na+-free solution (Fig. 5A, 140 mM Li+, trace c; 140 mM NMDG+, trace e). As Na+-free solution (Li+ or NMDG+) also altered basal [Ca2+]i, the Ca2+ responses to 140 mM Li+ (Fig. 5A, trace b) or 140 mM NMDG+ (Fig. 5A, trace d) alone were obtained for digital subtraction. To compare Ca2+ clearance in Na+ and Na+-free solution, the Ca2+ responses to Li+ (Fig. 5A, trace b) or NMDG+ (Fig. 5A, trace d) alone were then subtracted from Ca2+ transients that return to Li+ (Fig. 5A, trace c) or NMDG+ (Fig. 5A, trace e), respectively. Figure 5B, left, superimposes the high K+-induced Ca2+ transients that return to 140 mM Na+ (a), to 140 mM Li+ (c − b), and to 140 mM NMDG+ (e − d). The result indicates a similar slowing of the fast decay by both Na+-free solutions. Figure 5B, right, superimposes the normalized Ca2+ responses to reveal the time when the decay in Li+ and in NMDG+ began to deviate from that in Na+. It appears that Na+-free solution-induced slowing of the fast decay phase occurred earlier in NMDG+ than in Li+. The reason for the earlier action of NMDG+ is not clear at this moment.

Fig. 5.

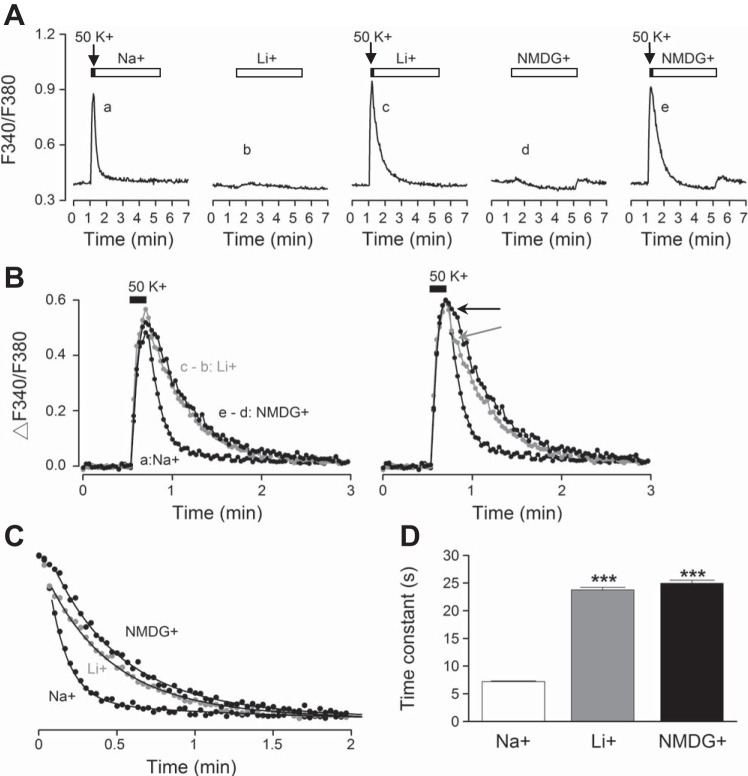

Zero Na+ slows the fast decay phase of high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients. A: averaged Ca2+ responses (n = 20 cells) to 50 mM K+ for 10 s followed by return to control solution (140 mM Na+) (a), to 140 mM Li+ for 4 min (b), to 50 mM K+ followed by return to Li+ (c), to 140 mM NMDG+ for 4 min (d), and to 50 mM K+ followed by return to NMDG+ (e). B, left: comparison of the Ca2+ responses that return to Na+ (a), to Li+ (c − b), and to NMDG+ (e − d) indicates a slowing effect of Na+-free solutions on the fast decay phase. Right: normalization of Ca2+ responses in Na+ and Na+-free solution indicates the time when Li+ (marked by gray arrow) and NMDG+ (marked by black arrow) began to slow the Ca2+ decay. C: time courses of Ca2+ decay expanded for curve fitting to obtain decay time constants. The smooth curves through the data points were calculated with a fast time constant of 7.2 s, 24 s, and 25.2 s for Na+, Li+, and NMDG+, respectively. D: statistics showing a 3-fold increase in the fast decay time constants by Na+-free solutions (n = 20 cells). ***P < 0.001. Daytime recordings (ZT 7).

To quantify the slowing effect of Na+-free solution on Ca2+ clearance, the decay time courses of Ca2+ transients are further expanded in Fig. 5C. The theoretic curves fitted to the data points were calculated with two exponential decay phases as described above. The fast decay time constants used to calculate the curves were 7.2 s, 24 s, and 25.2 s in 140 mM Na+, 140 mM Li+, and 140 mM NMDG+, respectively, with the slow decay time constants set to 1.5 min. The result indicates a threefold increase in the fast decay time constant by Na+-free solutions. It should be noted that Na+-free solution may appear to alter the slow decay phase in some experiments. Nevertheless, as the slow Ca2+ clearance is prone to subtraction artifact because of its small amplitude, no further attempt will be made to pursue this matter. Figure 5D summarizes the effects of Na+-free solution on the fast decay time constant determined from each of the 20 cells in this particular experiment. On average, the fast decay time constants increased from 7.2 ± 0.1 s (n = 20), to 23.8 ± 0.5 s (n = 20; P < 0.001, ANOVA), and to 25.0 ± 0.5 s (n = 20; P < 0.001, ANOVA) in Na+, Li+, and NMDG+, respectively.

To summarize the data from different experiments, only the average Ca2+ signal from each experiment was fitted with theoretic curves to obtain the value of the fast decay time constant. For a total of 26 experiments (n = 271 cells), the fast decay phase in control solution (140 mM Na+) had total signal amplitude of 86 ± 1% and a time constant of 7.3 ± 0.3 s. Two-way ANOVA reveals no difference in the fast decay time constant between cells from dorsal and ventral SCN (F = 0.57, P = 0.46) or between experiments performed at day and at night (F = 0.12, P = 0.73), with the values of fast decay time constant being 7.2 ± 0.6 s (n = 6 experiments, 94 cells; dorsal SCN at day), 7.4 ± 1.0 s (n = 5 experiments, 55 cells; dorsal SCN at night), 7.5 ± 0.4 s (n = 10 experiments, 71 cells; ventral SCN at day), and 6.8 ± 0.4 s (n = 5 experiments, 51 cells; ventral SCN at night). Among them 23 experiments were performed to determine the effects of Na+-free solution on the fast decay time constant, the values being 7.6 ± 0.3 s (n = 23 experiments for a total of 261 cells), 24.7 ± 1.9 s (n = 15 experiments, 202 cells; P < 0.001, ANOVA), and 25.6 ± 2.8 s (n = 12 experiments, 110 cells; P < 0.001, ANOVA), in Na+, Li+, and NMDG+, respectively.

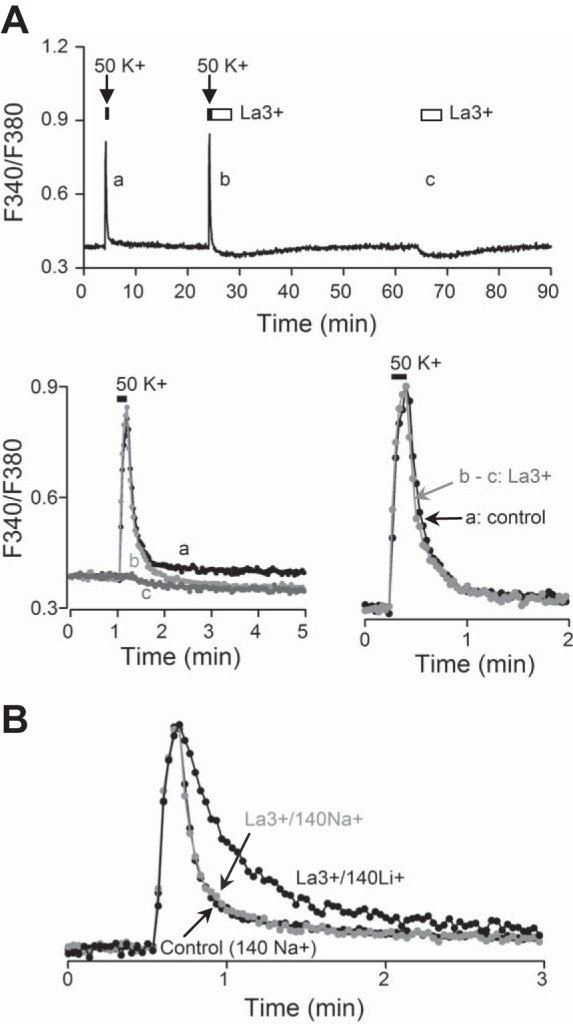

In contrast to the marked effects of Na+-free solution on slowing the fast Ca2+ decay phase, the blockade of plasmalemmal Ca2+ pumps [plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA)] with 250 or 300 μM La3+ (Shimizu et al. 1997) did not slow the rate of Ca2+ clearance (Fig. 6). Figure 6A, top, shows the average Ca2+ signals (n = 20 cells) from an experiment designed to determine the effects of La3+ on Ca2+ clearance. Note that La3+ lowered basal [Ca2+]i, which returned slowly to baseline for ∼10 min. Figure 6A, bottom left, superimposes the high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients that return to control (a) and to 250 μM La3+ solution (b), as well as the Ca2+ response to La3+ alone (c) for subtraction purpose. Figure 6A, bottom right, superimposes the normalized Ca2+ responses that return to control (a) and to 250 μM La3+ solution after subtraction (b − c). On average, the fast decay time constant was 7.4 ± 0.3 s (n = 5 experiments, 123 cells) in control conditions and 7.7 ± 1.1 s in La3+ (n = 5 experiments, 123 cells; P > 0.05, paired t-test). Furthermore, while the fast Ca2+ decay phase was little altered by La3+ inhibition of PMCA, it was again slowed by the removal of external Na+ (Li+ substituted) to block forward NCX in another experiment (n = 20 cells) (Fig. 6B). Taken together, the results indicate that in SCN neurons NCX, as opposed to PMCA, plays an important role in the clearance of Ca2+ after depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 6.

La3+ does not slow the decay phase of high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients. A, top: averaged Ca2+ responses (n = 20 cells) to 50 mM K+ for 10 s followed by return to control solution (a), to 50 mM K+ for 10 s followed by return to 250 μM La3+ for 4 min (b), and to 250 μM La3+ for 4 min (c) for subtraction purpose. Note that La3+ alone lowered basal [Ca2+]i with slow recovery (c). Bottom left: superimposition of Ca2+ responses to high K+ in control (a) and in 250 μM La3+ (b) and to La3+ alone (c). Bottom right: normalization of Ca2+ responses in control (black trace, a) and in La3+ after subtraction (gray trace, b − c), indicating a minimal effect of La3+ on Ca2+ decay. B: normalization of average Ca2+ responses (n = 20 cells) that return to control (140 mM Na+), to 300 μM La3+ (gray trace), and to 300 μM La3+/140 Li+. Note that the averaged Ca2+ transients marked by La3+/140 Na+ and La3+/140 Li+ have been digitally subtracted. Similar results were also obtained from 2 other experiments (n = 40 cells). Daytime recordings (ZT 6).

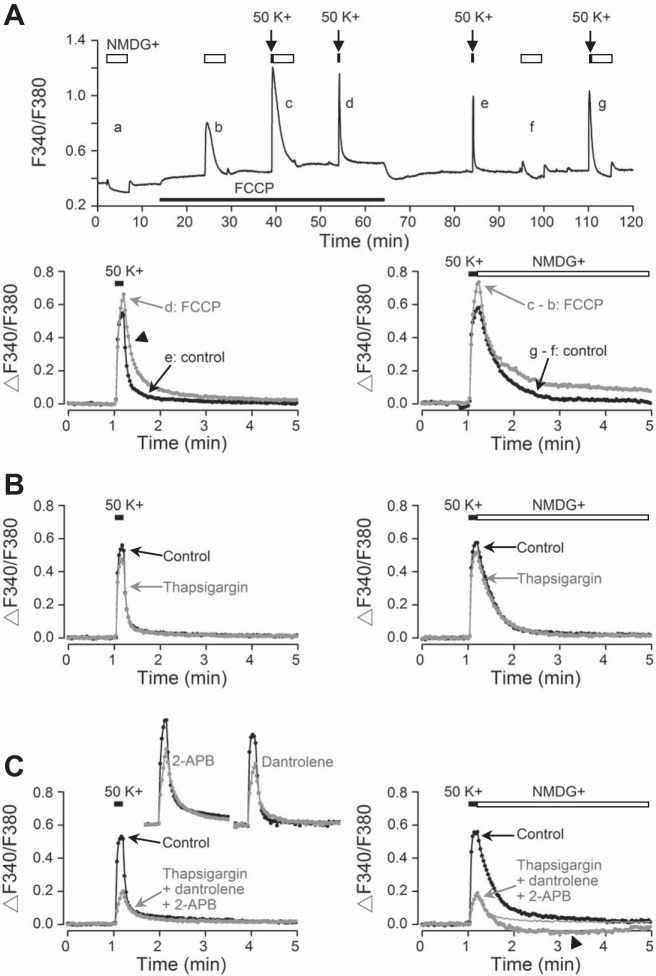

To investigate the role of mitochondria, the protonophore FCCP was used to reduce the driving force for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Figure 7A shows such a representative experiment (averaged response from 16 cells). The result indicates that FCCP (0.1 μM) increased basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 7A, top) and increased the peak amplitude as well as slowing the decay of high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 7A, bottom). This concentration was chosen because higher FCCP concentrations of 0.3 and 1 μM have marked often biphasic, excitatory followed by inhibitory, effects on spontaneous firing. On average, 0.1 μM FCCP increased basal [Ca2+]i signals by 0.056 ± 0.004 (n = 133 cells from 6 experiments) and the peak amplitude by 10 ± 3% (n = 133 cells from 6 experiments; P < 0.05, paired t-test). Note that 140 mM NMDG+ induced Ca2+ uptake in FCCP (Fig. 7A, trace b) but not in control (Fig. 7A, traces a and f), an effect most likely mediated by reverse NCX due to FCCP-induced elevated [Na+]i (unpublished observation, Wang YC, Huang RC; see Tretter et al. 1998). Superimposition of Ca2+ transients indicates that FCCP prolonged both fast and slow decay phases in 140 mM Na+ (Fig. 7A, bottom left) but mostly the slow decay phase in Na+-free (NMDG+ substituted) solution (Fig. 7A, bottom right). Together the FCCP results suggest a role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in regulating basal [Ca2+]i and, in particular, the slow decay after depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 7.

Effects of FCCP, thapsigargin, dantrolene, and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) on high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients. A, top: effect of FCCP (0.1 μM) on averaged Ca2+ responses (n = 16 cells) from a representative experiment. Open horizontal bars represent the duration of Na+-free (NMDG+ substituted) solution (b and f being for subtraction purpose). Bottom left: superimposition of Ca2+ responses to high K+ in control (e) and in FCCP (d), showing the prolongation of both fast (marked by arrowhead) and slow decay phases. Bottom right: superimposition of Ca2+ responses that return to NMDG+ in control (g − f) and in FCCP (c − b), showing the prolongation of mostly the slow decay phase. B: effect of thapsigargin (1 μM) on averaged Ca2+ responses (n = 9 cells) that return to Na+ (left, gray trace) and to NMDG+ (right, gray trace). Note that the Ca2+ responses that return to NMDG+ (right) have been digitally subtracted. C: effect of a blocker cocktail (1 μM thapsigargin, 10 μM dantrolene, and 100 μM 2-APB) on averaged Ca2+ responses (n = 12 cells) that return to Na+ (left, gray trace) and to NMDG+ (right, gray trace). Note that the Ca2+ responses that return to NMDG+ (right) have been digitally subtracted. Inset (left): averaged Ca2+ responses to 100 μM 2-APB (gray trace; n = 20 cells) and to 10 μM dantrolene (gray trace; n = 11 cells). Daytime recordings (ZT 5–9).

To investigate the role of endoplasmic reticulum, the experiment was done with thapsigargin to block the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) in a way similar to that shown in Fig. 7A. Superimposition of Ca2+ transients (average response from 9 cells) indicates that thapsigargin (1 μM) reversibly reduced the peak amplitude but had no effect on Ca2+ clearance kinetics (Fig. 7B), with the latter effect suggesting that SERCA may not play an important role in shaping the Ca2+ transient. Thapsigargin also reversibly lowered basal [Ca2+]i to various degrees. On average, 1 μM thapsigargin decreased basal [Ca2+]i signals by 0.006 ± 0.003 (n = 83 cells from 6 experiments) and reduced peak amplitude by 19 ± 2% (n = 83 cells from 6 experiments; P < 0.001, paired t-test). As the blockade of SERCA by thapsigargin is irreversible, the reversible inhibition by thapsigargin in basal [Ca2+]i and peak Ca2+ transients is most likely due to its block of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Shmigol et al. 1995).

To determine the role of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, the experiment was done with a cocktail of blockers for ryanodine receptor (10 μM dantrolene), IP3 receptor (100 μM 2-APB), and SERCA (1 μM thapsigargin). Superimposition of Ca2+ transients (average response from 12 cells) indicates that the blocker cocktail markedly reduced the peak amplitude (Fig. 7C). The blocker cocktail also lowered basal [Ca2+]i. On average, the blocker cocktail decreased basal [Ca2+]i signals by 0.07 ± 0.01 (n = 40 cells from 4 experiments) and reduced peak amplitude by 64 ± 2% (n = 40 cells from 4 experiments; P < 0.001, paired t-test). The marked inhibition of peak Ca2+ transients was a result of combined inhibition by thapsigargin, dantrolene, and 2-APB, as individually 10 μM dantrolene and 100 μM 2-APB (Fig. 7C, left, inset) reduced peak transients by 45 ± 2% (n = 91 cells from 4 experiments; P < 0.001, paired t-test) and 42 ± 2% (n = 99 cells from 4 experiments; P < 0.001, paired t-test), respectively. On the other hand, the cocktail effect on basal [Ca2+]i was mostly due to dantrolene, which decreased basal [Ca2+]i signals by 0.06 ± 0.01 (n = 91 cells from 4 experiments), whereas 2-APB had a biphasic (both increasing and decreasing) effect and slightly increased basal [Ca2+]i signals by 0.004 ± 0.004 (n = 99 cells from 4 experiments). Neither drug appreciably altered the Ca2+ clearance kinetics, suggesting that Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release does not play an important role in shaping the Ca2+ transient. Note the good superimposition of the slow decay phase of Ca2+ transients despite marked difference in their peak amplitude (Fig. 7C, left). Furthermore, Na+-free solution had little effect on the remaining Ca2+ transient in the presence of the blocker cocktail (Fig. 7C, right), as shown by the excellent superimposition (at least for the first 30 s) with the Ca2+ transient that returned to 140 mM Na+ (curve replotted from Fig. 7C, left). The lower-than-baseline Ca2+ level during the slow decay phase (marked by arrowhead) was an artifact due to subtraction.

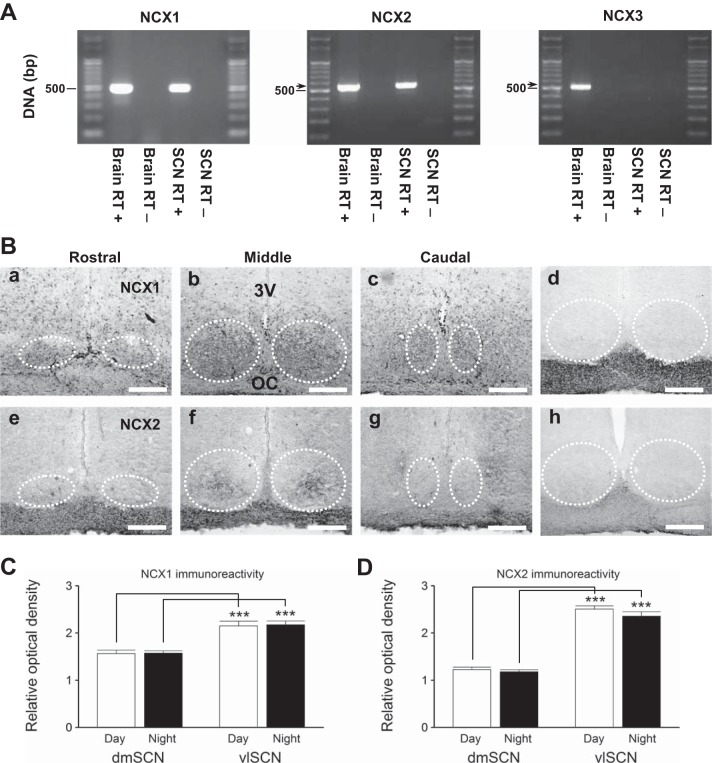

Expression and distribution of NCX isoforms in SCN.

We used RT-PCR to determine the expression of NCX isoforms in the SCN (Fig. 8A). Positive control reactions were performed by using cDNA of rat brain NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 to determine the primer efficiency and anneal temperature. These primers were then used to examine the gene transcription of NCX1-3 isoforms in the SCN. The positive signals with NCX1 and NCX2 primers, compared with the control (with omission of reverse transcriptase), indicate the presence of mRNA for NCX1 and NCX2 in the SCN.

Fig. 8.

Expression and distribution of NCX isoforms in the SCN. A: RT-PCR analysis of mRNAs for NCX isoforms. Positive controls were performed with cDNA from rat brain. The expected PCR product sizes for NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 were 494, 529, and 517 bp, respectively. Negative controls were performed by using reverse transcription products with omission of reverse transcriptase (RT−) to examine the contamination of genomic DNA. The positive signals with NCX1 and NCX2 primers, compared with the RT− control, indicate the presence of mRNA for NCX1 and NCX2 in the SCN. B: distribution of immunoreactivity to NCX1 and NCX2. NCX1 immunoreactivity is distributed throughout the rostrocaudal axis of the SCN (a–c). In contrast, NCX2 immunoreactivity is restricted to the ventrolateral region of the SCN and is best seen in the middle section of the nucleus (f). Rostral (a, e), middle (b, f), and caudal (c, g) sections of the SCN (encircled by dotted lines) are shown. Negative controls were without primary antibodies (d, h). Scale bars, 200 μm. OC, optic chiasm; 3V, third ventricle. C: statistics showing the average relative optic density for NCX1, the values being 1.56 ± 0.07 (n = 6), 1.57 ± 0.06 (n = 6), 2.15 ± 0.10 (n = 6), and 2.17 ± 0.08 (n = 6) for dorsomedial SCN (dmSCN) at day (ZT 8), dmSCN at night (ZT 14), ventrolateral SCN (vlSCN) at day, and vlSCN at night, respectively. D: statistics showing the average relative optic density for NCX2, the values being 1.23 ± 0.04 (n = 4), 1.18 ± 0.05 (n = 4), 2.50 ± 0.07 (n = 4), and 2.35 ± 0.09 (n = 4) for dmSCN at day, dmSCN at night, vlSCN at day, and vlSCN at night, respectively. ***P < 0.001.

Immunohistochemistry with NCX isoform-specific antibodies was also used to study the distribution pattern of NCX1 and NCX2 isoforms (Fig. 8B). The result shows the presence of NCX1 immunoreactivity throughout the rostrocaudal axis of the SCN (Fig. 8B, a–c). In the medial SCN the NCX1 immunoreactivity is present in the whole SCN, albeit with gradually decreasing staining intensity in the direction from ventral to dorsal area (Fig. 8Bb). The more intense NCX1 immunoreactivity in the ventrolateral SCN is associated with more intense neuropil staining in this area, as seen on high magnification (not shown). In contrast to the wide distribution of NCX1 immunoreactivity, NCX2 immunoreactivity is restricted to the ventrolateral region of the SCN (Fig. 8B, e–g) and is best seen in the middle section of the nucleus (Fig. 8Bf). This region is dominated by vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)- and gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP)-containing neurons, which receive photic inputs (Moore et al. 2002). Notably, NCX2 immunoreactivity was weak or absent in the area adjacent to the optic chiasm, where the VIP-containing neurons are situated (Moore et al. 2002). Negative controls were without primary antibody against NCX1 (Fig. 8Bd) or NCX2 (Fig. 8Bh).

To investigate variation in NCX1 and NCX2 immunoreactivity, relative optical density was determined from the ventrolateral and dorsomedial regions of the SCN obtained from animals killed during the day (ZT 8) and at night (ZT 14). The statistics for NCX1 and NCX2 immunostaining intensity are shown in Fig. 8, C and D, respectively. Comparison of relative optical density between ZT 8 and ZT 14 indicates a lack of day-night variation in immunostaining intensity for either NCX1 (Fig. 8C) or NCX2 (Fig. 8D). Nevertheless, the immunostaining intensity for either isoform was higher in the ventrolateral than the dorsomedial SCN, irrespective of day or night.

DISCUSSION

NCX1 is the major NCX isoform involved in regulating somatic [Ca2+]i in SCN.

This study demonstrates the expression of mRNAs for NCX1 and NCX2 in the SCN. Furthermore, NCX1 is distributed throughout the whole SCN along the rostrocaudal axis, but NCX2 is restricted to the ventrolateral SCN, a region corresponding to the VIP- and GRP-positive area that receives major sensory inputs (Moore et al. 2002). The different distribution patterns of NCX1 and NCX2 suggest distinct roles played by the two isoforms. Importantly, we find that NCX regulates the fast recovery of Ca2+ transients in response to high-K+-induced Ca2+ influx. Together our results indicate an important role of NCX, most likely NCX1, in the regulation of somatic Ca2+ homeostasis in SCN neurons.

Comparison of immunoreactivity for NCX1 and NCX2 between subregions of the nucleus indicates stronger intensity for either isoform in the ventrolateral than dorsomedial SCN. A stronger NCX2 immunoreactivity is obvious because of its preferential distribution to the ventrolateral SCN, whereas the more intense NCX1 immunoreactivity is likely due to more intense neuropil staining. Nonetheless, no day-night difference was observed in the immunoreactivity for either isoform, at least between ZT 8 and ZT 14.

Reverse NCX can be demonstrated in elevated [Na+]i by monensin.

Na+-free solution was used to study Ca2+ uptake via reverse NCX in SCN neurons. Without a prior increase in [Na+]i, however, 0 Na+ decreases [Ca2+]i and then produces a rebound increase in [Ca2+]i on return to normal Na+. Zero Na+-induced [Ca2+]i decrease is mediated by blocking TTX-sensitive as well as nimodipine-sensitive Ca2+ influx. The result accords with previous findings of both action potential-mediated Ca2+ influx and nimodipine-sensitive basal Ca2+ influx in rat SCN neurons (Colwell 2000; Irwin and Allen 2007, 2009). As the CaV1.3 L-type Ca2+ channel is activated at low voltages (Xu and Lipscombe 2001) and present in the SCN neurons (Huang et al. 2012), the 0 Na+-induced inhibition of TTX-resistant, nimodipine-sensitive Ca2+ influx is likely mediated by deactivation of these channels as a result of membrane hyperpolarization. This explanation is reasonable, because the replacing ion Li+ has K+-like action on the Na+-K+ pump (Glitsch 2001) and at a concentration of 140 mM may enhance the Na+-K+ pump to hyperpolarize the membrane potential of SCN neurons.

The inability of 0 Na+ in control conditions to activate reverse NCX for Ca2+ uptake has also been observed in other intact cells such as Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (Reeves and Condrescu 2008; Urbanczyk et al. 2006) and myocytes (Ginsburg et al. 2013). This has been attributed to the low [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i in CHO cells (Reeves and Condrescu 2008; Urbanczyk et al. 2006) and is likely to be the case for SCN neurons as well, owing to the lowering effect of 0 Na+ on [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i.

In the presence of monensin to raise [Na+]i, 0 Na+ produces rapid Ca2+ uptake, which is eliminated in 0 Ca2+ and partially blocked by 10 μM KB-R7943 or 50 μM Ni2+, suggesting the activation of reverse NCX. The ability of monensin to allow for 0 Na+-induced activation of reverse NCX is likely mediated by the elevated [Na+]i, which has been shown to activate NCX by reducing or eliminating the need for Ca2+ allosteric activation in intact cells (Reeves and Condrescu 2008; Urbanczyk et al. 2006).

Comparison of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake in monensin between day and night indicates a diurnal rhythm in Ca2+ uptake for both ventral and dorsal SCN neurons, suggesting higher daytime NCX activity in the somatic plasma membrane in both regions. In contrast, the peak amplitude of 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake in monensin is similar between dorsal and ventral SCN neurons, suggesting similar NCX activity in cells of the two regions.

Forward NCX plays important role in regulation of Ca2+ clearance.

To determine the role of forward NCX in the regulation of Ca2+ clearance, high-K+ solution was used to evoke depolarization-induced Ca2+ entry. Our results show that after depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx the clearance of Ca2+ is best described by two exponential decay phases. The fast decay phase constitutes ∼85% of total signal amplitude and has a time constant of ∼7 s, and the remainder slower decay phase has a time constant of ∼2 min. No difference in the fast decay time constant is found between cells from dorsal and ventral SCN or between experiments performed during the day and at night, suggesting a similar rate of Ca2+ extrusion. In other words, the higher daytime 0 Na+-induced Ca2+ uptake in monensin may be a result of daytime increase in the amount, but not the turnover rate, of NCX transporters.

We show that the fast decay rate is decreased threefold by the blockade of forward NCX with the removal of extracellular Na+. The result indicates an important role of NCX in mediating rapid clearance of Ca2+. In contrast, the blockade of PMCA with La3+ has little effect on Ca2+ clearance. Together the results are consistent with the distinct properties of NCX and PMCA in handling Ca2+, with NCX being a low-affinity but high-capacity transporter able to handle a large amount of Ca2+ and PMCA a high-affinity but low-capacity transporter better suited for extruding Ca2+ at low levels (Blaustein and Lederer 1999).

On the other hand, the slow decay phase is mostly not affected by the blockade of PMCA or forward NCX. Although it is altered in some experiments, its small total signal amplitude (∼15%) is prone to subtraction artifact, thus preventing us from making a meaningful inference. Instead, reducing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake with FCCP prolongs mostly the slow decay of Ca2+ transients, in particular in the absence of external Na+ to block forward NCX. The apparent slowing of the fast decay by FCCP in 140 mM Na+ could be a result of reduced forward NCX activity due to FCCP-induced elevated [Na+]i. Alternatively, FCCP may increase the relative amplitude of the slow decay phase without altering fast decay kinetics, suggesting that FCCP may preferentially increase the Ca2+ component that contributes to the slow decay. The exact mechanism for this regulation is not certain at this moment. Further experiments are needed to better elucidate the mechanism.

In contrast to a role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake does not appear to play an important role in clearing Ca2+ after high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients. The reversible effect of thapsigargin on both basal [Ca2+]i and the peak Ca2+ transient can be accounted for by its inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Shmigol et al. 1995). Similarly, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release also appears not to play an important role in shaping the Ca2+ transient. The marked inhibition (by ∼65%) of peak Ca2+ transient by the cocktail of blockers for ryanodine receptor, IP3 receptor, and SERCA is most likely a combined effect of dantrolene and 2-APB, each reducing peak Ca2+ transients by ∼45%, which have been shown to block L-type Ca2+ channels (Bannister et al. 2008). Interestingly, the relatively unaltered slow decay phase of remaining Ca2+ transients in the blocker cocktail, which presumably blocks the L-type Ca2+ channels, suggests an origin of Ca2+ influx mostly from non-L-type Ca2+ channels, that is, Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels may be responsible for the fast decay phase and is extruded by NCX, an idea consistent with the insignificant effect of Na+-free solution on the remaining Ca2+ transient in the blocker cocktail (Fig. 7C). Together with the role of mitochondria in the regulation of basal Ca2+ and slow decay of depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients, our results suggest that different sources of voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx may be differentially regulated by NCX and mitochondria.

While NCX plays an important role in rapid clearance of Ca2+ after depolarization-induced Ca2+ loads, its involvement in the regulation of basal [Ca2+]i, although very likely (see below), is difficult to establish in this study. On one hand, replacement of Na+ with Li+ has complex actions on spontaneous firing to alter basal [Ca2+]i, thus rendering it impossible to distinguish its effect on forward NCX from that on membrane potential and spontaneous firing. On the other hand, replacement of Na+ with NMDG+ lowers basal [Ca2+]i by blocking the generation of action potentials and also hyperpolarizing the membrane potential to ∼−80 mV (Wang et al. 2012b), which would completely close both the high- and low-threshold voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Huang 1993) to prevent Ca2+ entry via these channels. Future studies with cells clamped at resting potentials may help better resolve this issue.

Functional implications.

The ability of NCX to rapidly clear depolarization-induced Ca2+ loads suggests a critical role of forward NCX in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis, particularly in relation to glutamate-induced Ca2+ signaling in SCN neurons. By studying Ca2+ response to retinohypothalamic tract synaptic transmission, Irwin and Allen (2007) conclude that the increase in somatic [Ca2+]i due to activation of glutamate receptors requires the generation of action potentials and activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. As somatic [Ca2+]i summates in response to a train of action potentials (Irwin and Allen 2007), the rate of Ca2+ clearance may dictate the kinetics of Ca2+ accumulation and thus the [Ca2+]i levels. The rate of Ca2+ clearance after voltage step-induced Ca2+ transients has been determined to have a single decay time constant of ∼8 s in the soma (Irwin and Allen 2007), a value close to the fast decay time constant determined in this study, suggesting the involvement of NCX in clearing somatic Ca2+ during interspike periods. Together with the observation that action potentials contribute to basal [Ca2+]i in rat SCN neurons (Colwell 2000; Irwin and Allen 2007, 2009; this study), it follows that NCX most likely also participates in the regulation of basal [Ca2+]i.

On the other hand, Irwin and Allen (2007) also show that in the dendrites depolarization-induced Ca2+ loads are larger and decay with a time constant of ∼0.8 s, 10 times faster than in the soma. A similar 10 times difference in Ca2+ decay time constants (6 vs. 0.6 s) has also been observed in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and attributed to the different surface-to-volume ratios between the soma and dendrites (Jaffe et al. 1994), that is, the same Ca2+ extrusion mechanism, i.e., the NCX, may be at work in the soma and dendrites in SCN neurons. The intense NCX1 immunoreactivity in the neuropil is consistent with this suggestion. Incidentally, in CA1 pyramidal cells the density of NCX1 is significantly higher in the dendritic shafts than in the soma (Lõrincz et al. 2007).

In rat supraoptic nucleus neurons, somatodendritic release of vasopressin (AVP) and oxytocin is closely associated with [Ca2+]i (Dayanithi et al. 2012). Importantly, NCX plays a role in the regulation of somatodendritic Ca2+ and AVP release (Komori et al. 2010). Along the same line of thinking, the ability of NCX to regulate somatic, and likely also dendritic, Ca2+ in the SCN neurons also suggests a possible involvement in the release of neuropeptides such as AVP, VIP, and GRP. Indeed, high-K+-induced, Ca2+-dependent somatodendritic release of dense-core vesicles has been previously demonstrated in the rat SCN (Castel et al. 1996). Furthermore, experiments with reverse-microdialysis perfusion also show high-K+-induced, Ca2+-dependent release of VIP, GRP, and AVP from the hamster SCN (Francl et al. 2010a, 2010b). How and to what extent the NCX may participate in the regulation of neuropeptide release will await further investigations.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Taiwan National Science Council (NSC 100-2320-B-182-009-MY3 and 101-2811-B-182-023; R. C. Huang) and by the Chang Gung Medical Research Foundation (CMRPD190321; R. C. Huang) and Molecular Medicine Research Center.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., R.-C.C., and R.-C.H. conception and design of research; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., and R.-C.C. performed experiments; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., R.-C.C., and R.-C.H. analyzed data; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., R.-C.C., and R.-C.H. interpreted results of experiments; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., and R.-C.H. prepared figures; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., R.-C.C., and R.-C.H. edited and revised manuscript; Y.-C.W., Y.-S.C., R.-C.C., and R.-C.H. approved final version of manuscript; R.-C.H. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bannister RA, Pessah IN, Beam KG. Skeletal L-type Ca2+ current is a major contributor to excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry (ECCE). J Gen Physiol 133: 79–91, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol Rev 79: 763–854, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel M, Morris J, Blenky M. Non-synaptic and dendritic exocytosis from dense-cored vesicles in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroreport 7: 543–547, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Hsu YT, Chen CC, Huang RC. Acid-sensing ion channels in neurons of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Physiol 587.8: 1727–1737, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS. Circadian modulation of calcium levels in cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur J Neurosci 12: 571–576, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayanithi G, Forostyak O, Ueta Y, Verkhratsky A, Toescu EC. Segregation of calcium signalling mechanisms in magnocellular neurones and terminals. Cell Calcium 51: 293–299, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 517–549, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JM, Buchanan GF, Tischkau SA, Chen D, Kuriashkina L, Faiman LE, Alster JM, McPherson PS, Campbell KP, Gillette MU. A neuronal ryanodine receptor mediates light-induced phase delays of the circadian clock. Nature 394: 381–384, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPolo R. Calcium influx in internally dialyzed squid giant axons. J Gen Physiol 73: 91–113, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt M, Vorwald S, Sobotzik JM, Bennett V, Schultz C. Ankyrin-B structurally defines terminal microdomains of peripheral somatosensory axons. Brain Struct Funct 218: 1005–1016, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki R, Huroda S, Ono D, Hasan MT, Ueda T, Honma S, Honma KI. Topological specificity and hierarchical network of the circadian calcium rhythm in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 21498–21503, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francl JM, Kaur G, Glass JD. Regulation of VIP release in the SCN circadian clock. Neuroreport 21: 1055–1059, 2010a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francl JM, Kaur G, Glass JD. Roles of light and serotonin in the regulation of gastrin-releasing peptide and arginine vasopressin output in the hamster SCN circadian clock. Eur J Neurosci 32: 1170–1179, 2010b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette MU, Mitchell JW. Signaling in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: selectively responsive and integrative. Cell Tissue Res 309: 99–107, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg KS, Weber CR, Bers DM. Cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: dynamics of Ca2+-dependent activation and deactivation in intact myocytes. J Physiol 591.8: 2067–2086, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch HG. Electrophysiology of the sodium-potassium-ATPase in cardiac cells. Physiol Rev 81: 1791–1826, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev 90: 1063–1102, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DJ, Gillette R. Circadian rhythm of firing rate recorded from single cells in the rat suprachiasmatic brain slice. Brain Res 245: 198–200, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groos GA, Hendriks J. Circadian rhythms in electrical discharge of rat suprachiasmatic neurones recorded in vitro. Neurosci Lett 34: 283–288, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian AT, Kao JP, Eckert BK, Tsien RY. Fluorescence ratio imaging of cytosolic free Na+ in individual fibroblasts and lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 264: 19458–19467, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Collins A, Matsuoka S. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J Gen Physiol 100: 933–961, 1992a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol 100: 905–932, 1992b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Tan BZ, Shen Y, Tao J, Jiang F, Sung YY, Ng CK, Raida M, Kohr G, Higuchi M, Fatemi-Shariatpanahi H, Harden B, Yue DT, Soong TW. RNA editing of the IQ domain in Cav1.3 channels modulates their Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Neuron 73: 304–316, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RC. Sodium and calcium currents in acutely dissociated neurons from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurophysiol 70: 1692–1703, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Sugiyama T, Wallace CS, Gompf HS, Yoshioka T, Miyawaki A, Allen CN. Circadian dynamics of cytosolic and nuclear Ca2+ in single suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuron 38: 253–263, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye ST, Kawamura H. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in a mammalian hypothalamic “island” containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 5962–5966, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RP, Allen CN. Calcium response to retinohypothalamic tract synaptic transmission in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurosci 27: 11748–11757, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RP, Allen CN. GABAergic signaling induces divergent neuronal Ca2+ responses in the suprachiasmatic nucleus network. Eur J Neurosci 30: 1462–1475, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto T, Shigekawa M. Differential inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms by divalent cations and isothiourea derivative. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C423–C430, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto T, Watano T, Shigekawa M. A novel isothiourea derivative selectively inhibits the reverse mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in cells expressing NCX1. J Biol Chem 271: 22391–22397, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe DB, Ross WN, Lisman JE, Lasser-Ross N, Miyakawa H, Johnston D. A model for dendritic Ca2+ accumulation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons based on fluorescence imaging measurements. J Neurophysiol 71: 1065–1076, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DY, Choi HJ, Kim JS, Kim YS, Jeong DU, Shin HC, Kim MJ, Han HC, Hong SK, Kim YI. Voltage-gated calcium channels play crucial roles in the glutamate-induced phase shifts of the rat suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Eur J Neurosci 21: 1215–1222, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori Y, Tanaka M, Kuba M, Ishii M, Abe M, Kitamura N, Verkhratsky A, Shibuya I, Dayanithi G. Ca2+ homeostasis, Ca2+ signalling and somatodendritic vasopressin release in adult rat supraoptic nucleus neurones. Cell Calcium 48: 324–332, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Yu AS, Lytton J. Tissue-specific expression of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoforms. J Biol Chem 269: 14849–14852, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Matsuoka S, Hryshko LV, Nicoll DA, Bersohn MM, Burke EP, Lifton RP, Philipson KD. Cloning of NCX2 isoform of the plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 269: 17434–17439, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linck B, Qiu ZY, He ZP, Tong QS, Hilgemann DW, Philipson KD. Functional comparison of the three isoforms of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1, NCX2, NCX3). Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C415–C423, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lõrincz A, Rozsa B, Katona G, Vizi ES, Tamas G. Differential distribution of NCX1 contributes to spine-dendrite compartmentalization in CA1 pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 1033–1038, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist GB, Kwak Y, Davis EK, Tei H, Block GD. A calcium flux is required for circadian rhythm generation in mammalian pacemaker neurons. J Neurosci 25: 7682–7686, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markova J, Hudecova S, Soltysova A, Sirova M, Csaderova L, Lencesova L, Ondrias K, Krizanova O. Sodium/calcium exchanger is upregulated by sulfide signaling, forms complex with the β1 and β3 but not β2 adrenergic receptors, and induces apoptosis. Pflügers Arch 466: 1329–1342, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer JH, Schwartz WJ. In search of the pathways for light-induced pacemaker resetting in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms 18: 235–249, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minta A, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic sodium. J Biol Chem 264: 19449–19457, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC, Leak RK. Suprachiasmatic nucleus organization. Cell Tissue Res 309: 89–98, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll DA, Longoni S, Philipson KD. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Science 250: 562–565, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll DA, Quedneau BD, Qui Z, Xia YR, Lusis AJ, Philipson KD. Cloning of a third mammalian Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, NCX3. J Biol Chem 271: 24914–24921, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa M, Canitano A, Boscia F, Castaldo P, Sellitti S, Porzig H, Taglialatela M, Annunziato L. Differential expression of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger transcripts and proteins in rat brain regions. J Comp Neurol 461: 31–48, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JP, Condrescu M. Ionic regulation of the cardiac sodium/calcium exchanger. Channels 2: 322–328, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Oomura Y, Kita H, Hattori K. Circadian rhythmic changes of neuronal activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat hypothalamic slice. Brain Res 247: 154–158, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, Borin ML, Blaustein MP. Use of La3+ to distinguish activity of the PMCA from NCX in arterial myocytes. Cell Calcium 21: 31–41, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmigol A, Kostyuk P, Verkhratsky A. Dual action of thapsigargin on calcium mobilization in sensory neurons: inhibition of Ca2+ uptake by caffeine-sensitive pools and blockade of plasmalemmal Ca2+ channels. Neuroscience 65: 1109–1118, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurneysen T, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD, Porzig H. Sodium/calcium exchanger subtypes NCX1, NCX2 and NCX3 show cell-specific expression in rat hippocampus cultures. Mol Brain Res 197: 145–156, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretter L, Chinopoulos C, Adam-Vizi V. Plasma membrane depolarization and disturbed Na+ homeostasis induced by the protonophore carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-hydrazon in isolated nerve terminals. Mol Pharmacol 53: 734–741, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanczyk J, Chernysh O, Condrescu M, Reeves JP. Sodium/calcium exchange does not require allosteric calcium activation at high cytosolic sodium concentrations. J Physiol 575: 693–705, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Huang RC. Diurnal modulation of the Na+/K+-ATPase and spontaneous firing in the rat retinorecipient clock neurons. J Neurophysiol 92: 2295–2301, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Chen YS, Yang JJ, Huang RC. The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger regulates [Ca2+]i and neuronal excitability in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus (Abstract). 2012 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, Program No. 193.06, 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Huang RC. Effects of sodium pump activity on spontaneous firing in neurons of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurophysiol 96: 109–118, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Yang JJ, Huang RC. Intracellular Na+ and metabolic modulation of Na/K pump and excitability in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol 108: 2024–2032, 2012b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watano T, Kimura J, Morita T, Nakanishi H. A novel antagonist, No. 7943, of the Na+/Ca2+ exchange current in guinea-pig cardiac ventricular cells. Br J Pharmacol 119: 555–563, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal CaV1.3α1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci 21: 5944–5951, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Colvin RA. Regional differences in expression of transcripts for Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms in rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 50: 285–292, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]