Abstract

The cardiac Purkinje fiber network is comprised of highly specialized cardiomyocytes responsible for the synchronous excitation and contraction of the ventricles. Computational modeling, experimental animal studies and intracardiac electrical recordings from patients with heritable and acquired forms of heart disease suggest that Purkinje cells (PC) may also serve as critical triggers of life-threatening arrhythmias. Nonetheless, owing to the difficulty in isolating and studying this rare population of cells, the precise role of PC in arrhythmogenesis and the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for their pro-arrhythmic behavior are not fully characterized. Conceptually, a stem cell-based model system might facilitate studies of PC-dependent arrhythmia mechanisms and serve as a platform to test novel therapeutics. Here, we describe the generation of murine embryonic stem cells (ESC) harboring pancardiomyocyte and PC-specific reporter genes. We demonstrate that the dual reporter gene strategy may be used to identify and isolate the rare ESC-derived PC (ESC-PC) from a mixed population of cardiogenic cells. ESC-PC display transcriptional signatures and functional properties, including action potentials, intracellular calcium cycling and chronotropic behavior comparable to endogenous PC. Our results suggest that stem-cell derived PC are a feasible new platform for studies of developmental biology, disease pathogenesis and screening for novel anti-arrhythmic therapies.

Keywords: Stem Cells, Purkinje Cells, Cardiac Myocytes, Purkinje Fibers, Cardiac Conduction System, Cardiac Arrhythmias

Introduction

The cardiac conduction system (CCS) encompasses a heterogeneous network of cells that orchestrate the initiation and propagation of a wave of electrical excitation throughout the myocardium. Purkinje cells (PC) are the most distal component of the CCS and are structurally and functionally specialized to rapidly deliver an excitatory depolarizing wave to the working myocytes of the ventricular myocardium. More than forty years ago, Hoffman and colleagues proposed that PCs might contribute to human arrhythmias [1], and in the ensuing time substantial experimental data has accumulated supporting this concept. Indeed, PC have now been implicated as a source of arrhythmic triggers in syndromes as varied as ischemic heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), Brugada syndrome and long QT syndrome [2–5].

The mechanisms that promote arrhythmic behavior in PCs are not fully characterized. Distinct ultrastructural features including decreased T tubular density, a more prominent role for IP3-sensitive Ca2+ channels, as well as the unique complement of proteins regulating ionic and intracellular calcium fluxes may all play a role [6–10]. As a consequence, when challenged with stressors that promote electrical remodeling or changes in intracellular Ca2+ handling, compared to working ventricular cardiomyocytes, PC display a greater propensity to develop spontaneous Ca2+ release events and after-depolarizations [11–15]. Interestingly, this mechanism may be operative not only in acquired forms of heart disease, but also may extend to inherited syndromes. In CPVT, for example, molecular defects in SR calcium release promote the development of DADs and recent studies of RyR2R4496C/+ mutant mice by our laboratory and others have suggested that these triggers may arise from the Purkinje fiber network [16, 17]. This mechanism may also pertain to forms of LQTS. Endocardial mapping and ablation studies in the anthopleurin-A model of LQT3 have implicated the Purkinje network as the arrhythmic trigger [18], as have very recent computational studies [19]. Whereas heterogeneous prolongation of action potential durations and early after-depolarizations are generally thought to underlie the arrhythmic substrate, a recent study of Scn5aΔKPQ LQT3 myocytes suggests that elevation of SR calcium load may increase ITI, resulting in arrhythmogenic DADs [20]. Consistent with this concept, our own data suggest that PCs are even more sensitive to the pro-arrhythmic effects of the Scn5aΔKPQ LQT3 mutation than ventricular myocytes. Importantly, many of the unique structural and transcriptional features of PCs appear common to murine and larger mammals [10], suggesting that in-sights from murine models will be highly relevant to understanding human arrhythmia mechanisms.

Recently, various experimental strategies including computational modeling, cellular and animal model systems, as well as growing clinical experience of arrhythmic patients has led to a greater appreciation of the role of PCs in cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Nonetheless, a more complete understanding of disease pathogenesis as well as efforts to develop identify PC-specific therapeutic targets has been hampered by the paucity of strategies to efficiently identify, isolate and manipulate this rare sub-population of cardiomyocytes. Here we describe the creation and characterization of genetically engineered ESC that allow for the isolation of virtually unlimited numbers of Purkinje-like cardiomyocytes.

Materials and Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as put forward by the US National Institutes of Health, 1996 and approved by the NYU School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Transgenic mice harboring a Cntn2-eGFP BAC reporter gene, which identify cells of the specialized cardiac conduction system, have previously been described [16, 21, 22]. For Cntn2-eGFP expression studies, wild type C57Bl/6 females were crossed with Cntn2-eGFP males. Transgenic hearts of postnatal mice or embryos were identified by transgene expression. Additionally, tail-biopsies or extra-embryonic tissue were used for PCR analysis.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Analysis

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis of heart cryosections was carried out as described previously by Maass et al. [23]. Cell cultures grown on chamber well slides (Corning) were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15min and subsequently processed as described for cryosections [24]. For fluorophore conjugated primary antibodies, incubation with secondary antibodies was omitted and cultures were incubated according to manufactures’ recommendation, including Hoechst dye for nuclear stain for only 15min. All steps were conducted with cells protected from direct light in order to maximally preserve endogenous reporter gene fluorescence after fixation. Primary antibodies and secondary antibodies used are listed in the Supplemental Table 1 (Sup Table 1).

Derivation of mESC

ES colonies were derived from blastocysts harvested from 3.5 dpc female Cntn2-eGFP mice [24, 25]. In brief, super-ovulated, time-pregnant mice were sacrificed, uteri were dissected, transferred into pre-warmed M2 media (Embryomax M2 media, Fisher Scientific) and blastocysts were flushed out using 50% M2 media in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Blastocysts were transferred to an upright microscope placed in a cell culture hood, washed twice in drops of sterile M2 media and each blastocyst was cultured in a well of a 24 cluster plates on irradiated mouse embryonic feeder cells (MEFs) in serum-free mESC KO media (20% Knockout serum, Life Technologies; 100u/ml leukemia inhibiting factor (LIF; ESGRO, Chemicon), 100μM MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids, 1mM Sodium Pyruvate, 2mM glutamine, 0.1μM β-Mercaptoethanol, 50u/ml Penicillium and 50μg/ml Streptomycin in High Glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium). Inner cell mass colonies of attached and hatched blastocysts were dissociated after 4 days into single cells or clumps of less than 10 cells with 2.5% trypsin (Life Technologies) and cultured in mESC KO with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone SH3007003; Fisher Scientific) for 24 hrs post dissociation. Isolated cell clones were subsequently cultured using standard mESC protocol and tested for presence of Cntn2-eGFP reporter gene. Cntn2-eGFP BAC positive cell clones were expanded and aliquots cryopreserved.

mESC culture in serum containing media

ESC were cultured in complete mESC media (1000 u/ml LIF, 15% FBS (Hyclone SH3007003), 100μM MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Life Technologies), 1mM Sodium Pyruvate (Life Technologies), 2mM glutamine (Glutamax, Life Technologies), 0.1M β-Mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies), 50u/ml Penicillium and 50μg/ml Streptomycin (Life Technologies), in High Glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Life Technologies) on MEFs as described [24, 25]. MEFs were grown at 50,000 cells per cm2 on gelatinized culture vessels in MEF media (10% FBS (Hyclone SH3007003), 100μM MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids, 1mM Sodium Pyruvate, 2mM glutamine, 0.1μM β-Mercaptoethanol, 50u/ml penicillin and 50μg/ml streptomycin in High Glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium). mESC were plated at 100,000–200,000 cells per cm2 on MEFs. Colonies were trypsinized (TrypLE, Life Technologies) while slightly sub-confluent and daily monitored for good morphology.

Pluripotency analysis

ESC were depleted of MEFs for at least three passages, dissociated and 500 cells were aggregated to embroid bodies for 72hrs via hanging drops in complete media without LIF and with 10% FBS. For analysis of Otx2, Hand1 and GATA4 expression, EBs were dissociated, plated onto eight chamber culture slides (Corning) and processed for immunocytochemistry after 3 more days of culture. For analysis of Nestin, AFP and Brachyury expression, two EBs were per plated per well in four chamber culture slides (Corning) and EB outgrowths were processed for immunocytochemistry after 3 more days of culture.

Spontaneous cardiac differentiation

To identify Cntn2-eGFP reporter mESC clones with good cardiogenic potential, spontaneous differentiations were carried out in 10% FBS containing cardiac differentiation media modified from a protocol by Fehling et al. [26]. Spontaneous cardiomyocyte activity, evident as contracting areas within EB outgrowths, was detectable after 4 days of culture. Cardiogenic potential of mESC clones was evaluate by either the overall spontaneously contracting areas after 14 days of outgrowth culture (for Cntn2-eGFP mESC) or by mCherry reporter gene expression (for PC reporter mESC).

Lentiviral transduction of mESC

To generate dual reporter mESC, Cntn2-eGFP mESC were transduced with lentiviral particles encoding mCherry under control of the cardiomyocyte expressed αMHC promoter and a Blasticidin resistance cassette under control of the mESC expressed Rex1 promoter [27]. In brief, subconfluent 293T cells (ATCC) grown in antibiotic-free MEF media on gelatinized 175cm2 culture flask were transfected (Fugene HD, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with plasmid # 21228 (Addgene) and plasmids encoding PAX and VSV (custom) in the presence of 25uM Chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich). After 12hrs, the media was changed to complete mESC media. 48 and 72 hrs after transfection, cell supernatants were collected. Combined supernatants were 0.45um sterile filtered and incubated with 1 million Cntn2-eGFP mESC cells and 8ug/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) in suspension at 37C for 4 hours under gentle agitation. Cells were subsequently cultured on MEFs and transduced cell clones were enriched by Blasticidin (Life technologies) selection.

Directed cardiac differentiation of mouse ESC

Directed differentiation was carried out in the absence of FBS following a modified protocol developed by Kattman et al [28]. In brief, MEF depleted mESC were cultured in serum-free mESC Media contain 50% Neurobasal media (Life Technologies), 50% DMEM/F12 media(Life Technologies),0.5x N2 supplement, 0.5x B27 complete supplement, 2mM glutamine (Glutamax, Life Technologies), 0.05% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, Life Technologies), 150uM MTG, 10,00u/ml LIF, 5ng/ml human recombinant (rh) BMP4 (R & D Systems), 50u/ml Penicillium and 50μg/ml Streptomycin for 2 passages. Cells were then aggregated in low attachment culture vessels (Corning) at a concentration of 100,000 cells/ml in base media (75% Iscove’s MEM (IMEM, Life Technologies), 25% Ham’s F12 media (Life Technologies), 0.5x N2 supplement, 0.5x B27 without Retinoic acid supplement (Life Technologies), 0.05% BSA, 2mM glutamine, 0.05um Vitamine C, 450uM MTG 50u/ml penicillin and 50μg/ml streptomycin without LIF or cytokines for 48hrs to form embryoid bodies (EB). 48 hours after initial EB formation, EBs were dissociated and re-aggregated in base medium supplemented with 5ng/ml rhVEGF (R & D Systems), 1ng/ml rhBMP4 and 40ng/ml rhActivin A (R & D Systems). After 48 hours, EBs were dispersed and cultured as monolayer on fibronectin-coated culture vessels at 250,000–300,000 cells per cm2 in cardiac maintenance medium (StemPro-34 SF medium (Life Technologies), supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma), 5 ng/ml rhVEGF, 10ng/ml rh bFGF (R&D Systems), and 12.5 ng/ml rh FGF10 (R&D Systems)) for 28 days. Cardiac maintenance medium was supplemented with 150 ng/ml Dkk1 (R&D Systems) for the first 8 days. Cells were dissociated with 2% collagenase B (Roche) and 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies; FACS and qRT-PCR, electrophysiology) or fixed (immunocytochemistry).

Electrophysiology

The ESC-derived cardiac myocytes were re-plated onto gelatin-coated coverslips at low density and studied 48 hours later. Cells were perfused at room temperature with Tyrode’s solution containing (in mM): NaCl 137.7, KCl 5.4, NaOH 2.3, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, Glucose 10, and HEPES 10 (pH 7.4). Resting potential and action potentials (AP) were recorded in current clamp mode. The pipette solution for AP recording contained (in mM): KCl 50, K-aspartic acid 80, MgCl2 1, EGTA 10, HEPES 10 and Na2-ATP 3 (pH 7.2). The resistances of the electrodes were maintained between 1 to 3 MΩ. Stimulated action potentials were triggered by minimum positive pulses at 1Hz in current clamp mode. Sodium currents were recorded in normal Tyrode’s solution by holding cells at −120mV and pulsing to test potentials from −80 to 40mV. Peak current density was calculated as the maximal current recorded divided by the cell capacitance. Signals were recorded by amplifiers (MultiClamp 700B, Axon Instruments Inc.) and digitized (Model DIGIDATA 1440A, Axon Instruments Inc.). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using CLAMPEX 10.2 and CLAMFIT 10.2 software (Axon Instruments Inc.), respectively.

Intracellular Ca2+ Imaging

Cntn2-eGFP ESC-derived cardiomyocytes were exposed to a dye loading solution consisting of a standard Tyrode’s containing (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH at 22°C. The Tyrode’s solution was supplemented with 2.5 μm x-Rhod-1 acetoxymethyl ester (x-Rhod-1/AM; Invitrogen Inc., Eugene, OR) for 6 min at 22°C. The loading solution was removed, and cells were washed twice and equilibrated in fresh Tyrodes solution for 30 min to allow de-esterification of the dye before recording. Fluorescent signals were acquired from spontaneously contracting eGFP-positive cells using a 40X UVF objective (numerical aperture 1.0, Nikon), and single excitation wavelength microfluorimetry was performed using a PMT system (IonOptix Corp., Milton, MA), as previously described [16].

FACS, cDNA generation and Real Time PCR

Differentiated ESC cultures were isolated by incubating in one volume of 2% collagenase B for 30min at 37C and subsequent incubation in one volume 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 10min at 37C. Cells were dissociated by rigorous pipetting with 2 volumes of Stop Media (50% BenchMark FBS, 50% DMEM/F12 media, 30ug/ml DNase1, 50u/ml penicillin and 50μg/ml streptomycin), washed once in DMEM/F12 media and resuspended in FACS media (20mM D-glucose, 2% FBS, 50u/ml penicillin and 50μg/ml streptomycin in Hanks’ buffered saline). Cells were sorted using a MoFlo cell sorter (Dako) and 5000 cells per fraction were directly collected into Extraction Buffer (PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit, Arcturus). Total RNA was isolated according to PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit instructions, treated with RNase-free DNase (QIAGEN) and stored at −80C until further use. 10ul of total RNA with RNA integrity numbers (RIN) (Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit and Aglient Bioanalyzer) of 8 or higher were reversely transcribed into cDNA using the Ovation® Pico (NuGen) kit according to manufactures instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on a MasterCycler epgradient S RealPlex2 (Eppendorf). All experiments were carried out in triplicate with Power Sybr Green Master Mix (Life Technologies). CT values were normalized to CT values of housekeeping gene transcripts of corresponding amplicon size (H3B for Nkx2.5; PGK1 for all other primer combinations). Tests for differences were performed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc T-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Sup Table 2 (all from IDT).

RNA sequencing and RNA seq Data Analysis

RNASeq libraries were prepared using the NuGen Ovation RNA-Seq System V2, starting from 2 ng of DNAse I treated total RNA, following the manufacturer’s protocol.1000 ng of amplified cDNA were fragmented to an average size of 200 bp using a Covaris LE220 ultrasonicator, and the NuGen Ovation Ultralow Library System was used to generate indexed libraries with Illumina adapters, starting from 100ng of sheared cDNA. Ten cycles of PCR were used to amplify the library. The amplified library was purified using AMPure beads, quantified by Qubit and QPCR, and visualized in an Agilent Bioanalyzer. The libraries were pooled equimolarly, and loaded at 8 pM, on one rapid run HiSeq 2500 flow cells, onboard clustering protocol, as paired 50 nucleotide reads. Total yield of reads passing filter was 300 million. Raw sequencing reads were mapped to mouse genome (NCBI37/mm9) by using Bowtie aligner (0.12.9) with v2 and m1 parameters. Mapped reads were subsequently subjected to PCR duplicates removal before assigning to gene model with Htseq. All original RNA seq data were deposited in the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA study# SRP049694). To obtain significant differentially expressed genes, edgeR (3.4.2) was used with a standard two group comparison (PC versus CM) and p value adjustment as recommended. Under a slightly relaxed cutoff (p<0.05), a total of ~450 genes passed cutoff and were used for MA plot and further GO term analysis through GREAT web platform. GSAA analysis for set of genes (n=116) upregulated in adult Purkinje cells [22] was conducted with gene set association analysis for RNA-Seq (GSAA-SeqSP) [29], using gene-set permutation and Signal2Noise_log2Ration for differential expression analysis and weighted_KS for GSAA.

Results

Cntn2 is expressed in the developing cardiac conduction system

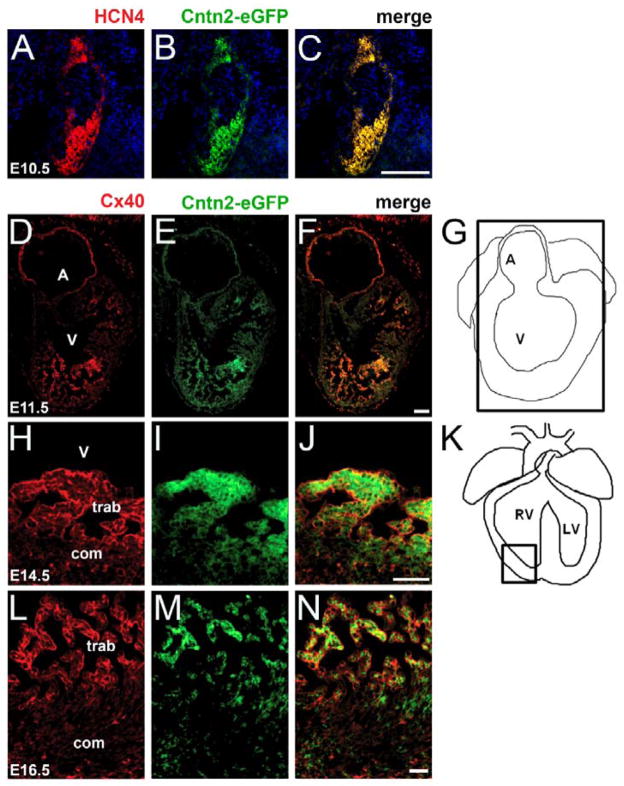

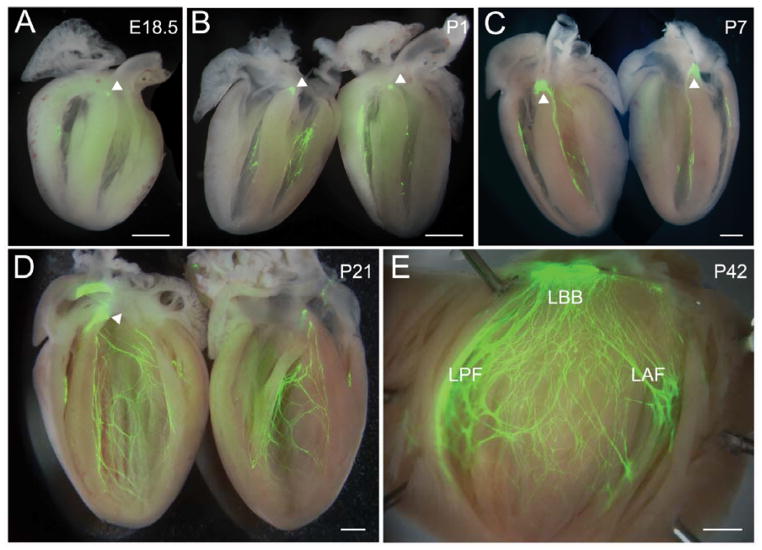

We previously reported that the GPI-linked cell adhesion protein Cntn2 is expressed in the Purkinje fiber network of murine and canine hearts, and that mice harboring a Cntn2-eGFP BAC transgene displayed robust reporter gene expression in the specialized CCS [21, 22]. During heart development, reporter gene expression is first detectable at E10.5 and is restricted to HCN4 positive cells in the sinoatrial node (SAN) and the atrioventricular node (AVN) (Fig 1A–C). Between E11.5 and E16.5, Cntn2 is also observed in the trabecular component of the developing ventricles, where it colocalizes with connexin40 protein (Cx40), encoded by the Gja5 gene, in cells that will give rise to the Purkinje fiber network (Fig 1D–N). In late fetal and postnatal hearts, Cntn2-eGFP expression is progressively more robust throughout the full extent of the CCS, as shown in whole-mount preparations (Fig 2A–E). These data suggested that expression of Cntn2 might serve as a useful marker of committed cardiac progenitors as they assumed a specialized conduction system phenotype.

Figure 1.

Expression pattern of Cntn2 during heart development. (A–C) Immunofluorescence colocalization of Cntn2EGFP and HCN4 expression in the heart of Cntn2EGFP/+ mouse embryos at E10.5. Cntn2 is uniquely expressed in the sinus atrial node (SAN) and atrioventricular node (AVN) where it colocalizes with HCN4. (D–N) Immunofluorescence colocalization of Cntn2EGFP and Cx40 expression in the heart of Cntn2EGFP/+ mouse embryos at (D–G) E11.5, (H–K) E14.5, and (L–N) E16.5. Cntn2 is expressed in the trabecular component of the left ventricle where it colocalizes with Cx40 during cardiogenesis. HCN4 (red, A–C), Cx40 (red, D–F), Cntn2EGFP (green), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue, A–C). A, atria; V, ventricle; com, compact myocardium; trab, trabecular myocardium. Scale bars: 25 μm.

Figure 2.

Expression of Cntn2 in the late embryonic and postnatal heart. (A–E) Whole mount of Cntn2EGPF hearts showing expression of Cntn2 throughout the CCS. (A) E18.5, (B) P1, (C) P7, (D) P21 and (E) P42. Robust expression of Cntn2 within the AV node is observed with epifluorescence after E18.5 (arrowheads). LBB, left bundle branch; LPF, left posterior fascicle; LAF, left anterior fascicle. Scale bars: 500 μm.

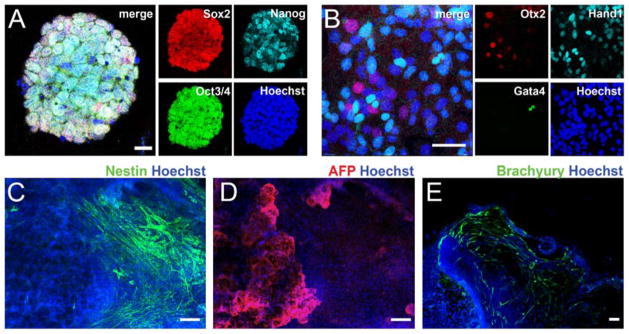

Generation of ESC-derived Purkinje Cells

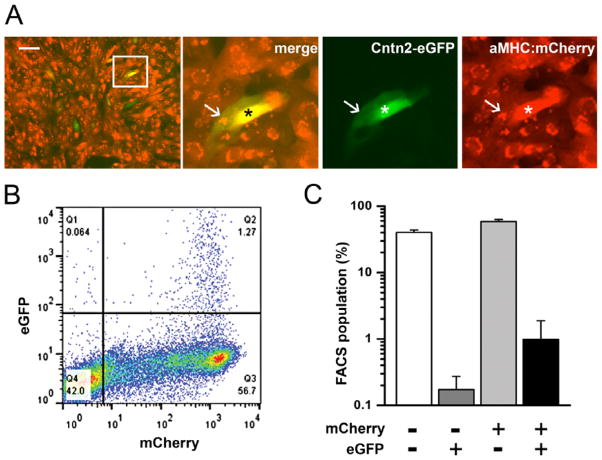

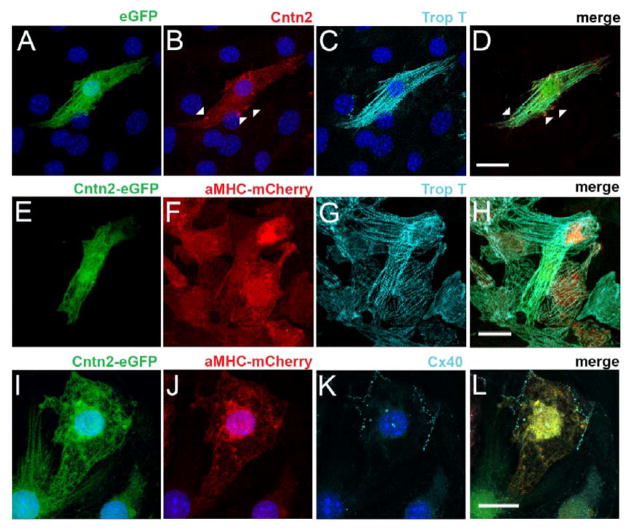

To test this hypothesis in a stem cell model system, ESC lines were generated from Cntn2-eGFP BAC transgenic mice. As Cntn2 is also expressed in a subset of neurons, we transduced the ESCs with a cardiomyocyte-specific MHCα-mCherry reporter lentivirus to facilitate the identification of cardiogenic derivatives. (Sup Fig 1). Individual subclones were analyzed for expression of pluripotency markers (Fig 3A) and their ability to differentiate into cells of all three germ layers (Fig 3B–E). During spontaneous differentiation of EBs, double positive cells derived from mCherry-positive cells were observed within 3 weeks of cardiogenic culture, appearing preferentially at the periphery of spontaneously contracting mCherry-expressing cell clusters (Sup Fig 2A). To generate cultures enriched in ESC-derived cardiomyocytes (ESC-CM), we employed a serum free, directed differentiation protocol modified from Kattman et al [28]. ESC-CM expressing the mCherry reporter gene were evident within one week after culturing in cardiac maintenance media, while double positive, putative ESC-PC could be seen after an additional two weeks in culture (Fig 4A, Sup Fig 2B, C). This time-course paralleled the sequential activation of endogenous αMHC and Cntn2 observed in the developing murine heart. FACS analysis of several independent differentiations demonstrated that ~60% of ESCs differentiated into working CMs and 1.9% into ESC-PCs (Fig 4B, C), a distribution that is comparable to the proportion of PC in the intact heart. After four weeks of differentiation, ESC-PC displayed significant cell elongation and increased surface area compared to ESC-CM (Sup Fig 3). ESC-PC expressed endogenous Cntn2 as well as troponin T in a sarcomeric pattern, consistent with their assignment as ESC-derived PC (Fig 5A–D). Individual eGFP+ ESC-PC could also be seen within clusters of ESC-CM, all of which co-expressed the MHCα-mCherry reporter and troponin T (Fig 5E–H). Additionally, robust expression of the conduction-system specific connexin40 gap junctional protein was detected along the membrane of mCherry+/eGFP+ ESC-PC (Fig 5I–L).

Figure 3.

Pluripotency Analysis. (A) mESC lines harboring the two reporter genes express pluripotency markers and spontaneously differentiate into cells of the three germ layer (B–E). Cells of ectodermal (Otx2, Nestin), endodermal (Gata4, AFP) and mesodermal (Hand1, Brachyury) origin. AFP, alpha fetoprotein. Bars in microns: 20 (A), 50 (B) 100 (C–E).

Figure 4.

Directed Cardiac Differentiation. (A) Genetically labelled mESC reproducibly differentiate into mCherry+ cardiomyocyte enriched populations, including eGFP+/mCherry+ ESC-PC. Insert: expression of both reporter genes varied; compare neighboring double-positive cells marked by arrow and asterisk. (B) FACS after 28 days of culture in cardiac maintenance media. (C) Bar graph for FACS populations of 4 independent cardiac differentiation cultures. Bar: 50 microns (A).

Figure 5.

Expression of Cardiac and Purkinje cell markers in ESC-PC. (A–D) Expression of endogenous Cntn2 protein (red, arrowheads) and troponin T (light blue) in single ESC-PC. (E–H) Expression of troponin T (light blue) in both ESC-CM and ESC-PC. (I–L) Expression of Cx40 (light blue) only in ESC-PC. Nuclei stained by Hoechst (dark blue). Bars: 20 microns.

Molecular analysis of ESC-derived Purkinje cells

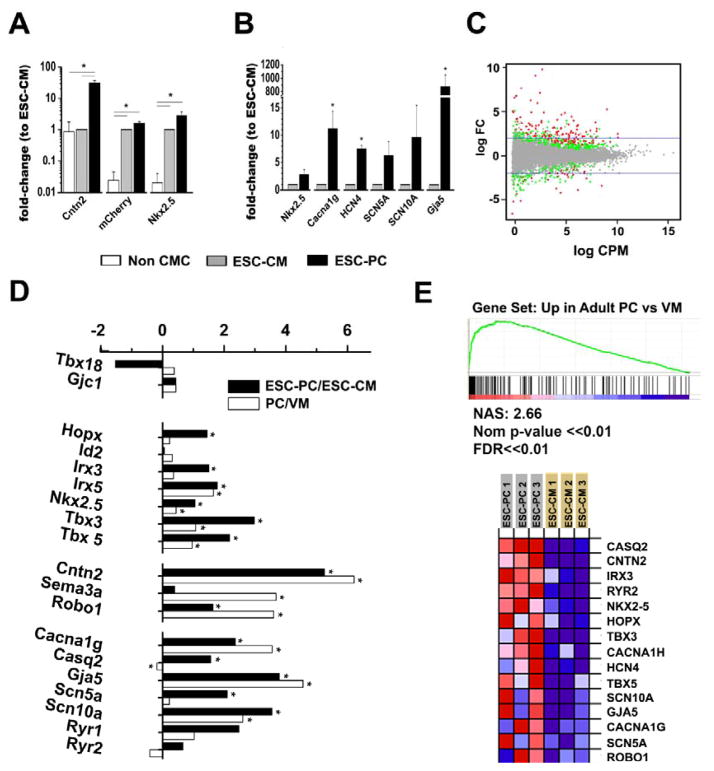

We performed qPCR to characterize and validate the transcriptional profile of the FACS-enriched population of ESC-PC compared to the ESC-CM. As anticipated, transcripts encoding the cardiac-specific MHCα-mCherry reporter were markedly enriched in both the ESC-CM and ESC-PC sub-populations compared to non-fluorescent, non-cardiogenic derivatives. In contrast, Cntn2 mRNA was enriched only in the double-positive ESC-PC fraction, confirming that the Cntn2-eGFP reporter gene faithfully reflected endogenous Cntn2 expression and validating the FACS strategy (Fig 6A). Both ESC-CM and ESC-PC robustly expressed the cardiac-specific transcription factor Nkx2-5, however this transcript was enriched almost 3-fold in ESC-PC compared to the ESC-CM, paralleling its enrichment in the ventricular conduction system of the intact heart [30]. We also examined the abundance of several additional cardiac conduction system enriched transcripts, and all were preferentially detected in ESC-PC, including Gja5, (connexin40, 700-fold); HCN4 (pacemaker channel; 8-fold), CACNA1G (Cav3.1; 11-fold) Scn5a (NaV1.5 sodium channel; 6-fold) and SCN10A (NaV1.8 sodium channel; 10-fold) (Fig 6B).

Figure 6.

Transcriptional Analysis of ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. (A, B) Quantitative real time PCR analysis of transcripts encoding selected conduction system markers, expressed as 2(−ΔΔCT) relative to mCherry+/eGFP− fraction (n=3 per cell population, errors as SEM). Significant differences between groups are noted as *. (C–E) RNA Sequencing was conducted for single mCherry+ ESC-CM and double eGFP+/mCherry+ ESC-PC fractions (n = 4 differentiations). (C) MA plot shows the genes that passed statistical cutoff p < 0.01 in red and 0.01 < p <0.05 in green. (D) Comparison of genes with significantly changed expression in ESC-PC vs. ESC-CM (dark bars) or adult PC vs. adult ventricular myocytes (VM) (white bars). (E) GSAASeqSP for transcripts enriched in adult PC (upper). NAS, normalized association score. Heatmap showing gene expression for 15 transcripts of the gene set (lower).

To obtain a more global assessment of the transcriptional profile of the ESC-PC, we performed RNA seq on FACS sorted ESC-CM and ESC-PC and subjected these data to GSAA-SeqSP analysis for genes enriched in adult PC compared to ventricular CM (Fig 6A–C) [22]. These results confirmed and extended the qPCR analysis and demonstrated enrichment of many previously reported ventricular conduction system specific markers including Hopx, Irx3, Irx5, Nkx2.5, Tbx3, Tbx5, Cntn2, Robo1, CACNA1G, Gja5 and Scn10a [21]. In contrast, we did not observe enrichment of transcripts reportedly expressed in nodal cells such as Tbx18 (Fig 6 and Sup Fig 4) [31–34]. Cntn2 is expressed in various neuronal tissues, however as expected with the cardiogenic differentiation protocol, we observed neglibible expression of a panel of transcripts associated with neuronal differentiation including Tubb3, Rbfox3, Map2, Sox2, Sox3, GFAP, Pax3, Mash1 and Nefl (Sup Table 3) [35–37]. Low counts of Nestin transcripts were detected, but in both ESC-PC and ESC-CM samples. We performed a GO Biological Process analysis, which demonstrated enrichment of transcripts associated with various aspects of cardiac development, transmembrane transport and regulation of ion transport (Sup Fig 5).

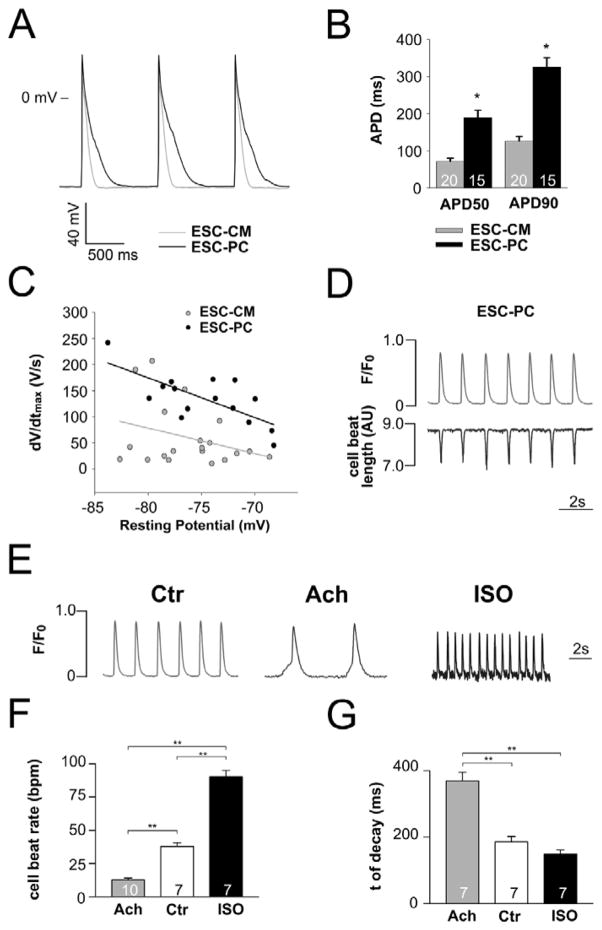

Electrophysiological analysis of ESC-derived Purkinje Cells

Endogenous PCs isolated from hearts display a distinct electrophysiological signature. Accordingly, to determine the potential utility of ESC-PC to appropriately model endogenous PC function, we used the patch-clamp technique. The spontaneous beat rate for ESC-CM was modestly but significantly faster than ESC-PC (Sup Table 4). Action potential recordings of ESC-PC demonstrated significant APD prolongation, quantified as both APD50 and APD90, compared to ESC-CM (Fig 7A, B; Sup Fig 6, 7 and Sup Table 4). Moreover, peak inward sodium current density INa and dV/dtmax were both significantly greater in ESC-PC compared to ESC-CM, comparable to the differential behavior seen in endogenous PCs and VMs. (Fig 7C, Sup Fig 6A and Table 4). Intracellular calcium imaging in ESC-PC revealed spontaneous Ca2+ transients, which were appropriately responsive to acetylcholine and isoproterenol, indicating negative chronotropic receptor activation to muscarinic stimulation and positive chronotropic receptor activation to β-adrenergic signaling (Fig 7E–F).

Figure 7.

Electrophysiological characterization of PC cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative action potential recordings from ESC-CM (light grey) and ESC-PC (dark grey) after 28 days of culture in cardiac maintenance media. (B) ADP50 and APD90 are prolonged in ESC-PC (n=15) compared to ESC-CM (n=20). (C) ESC-PC (n=15) exhibit faster upstroke velocity than ESC-CM (n=20). (D) Intracellular Ca2+ transients and corresponding cell length measurements in spontaneously beating ESC-PC. (E) Ca2+ transients, (F) beat rate; and (G) time constant of decay (τ) of the Ca2+ transient under control conditions (Ctr) or after exposure to acetylcholine (Ach) or isoproterenol (ISO). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.; numbers of cells studied are indicated. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Purkinje cells are important triggers of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias [38–43]. Nonetheless, despite their clinical significance, a paucity of experimental tools has precluded a deeper understanding of PC developmental biology, their mechanistic role in disease pathogenesis, and the potential efficacy of PC-targeted therapeutics. In this study, we demonstrate that Cntn2, a recently described marker of the adult specialized cardiac conduction system [21] could be used to identify, isolate, and functionally characterize ESC-derived PCs. Indeed, ESC-derived cardiac cells expressing Cntn2 display a developmental profile, transcriptional signature, and functional properties quite similar to endogenous cardiac Purkinje cells, including action potential prolongation, increased sodium current density compared to working ventricular cardiomyocytes and chronotropic sensitivity to adrenergic and vagal stimuli [44–48].

Contactins comprise a family of immunoglobulin domain containing cell adhesion molecules (IgCAMs), first characterized for their role during in brain and peripheral nerve development [49–52]. Cntn2 itself was first identified in the specialized cardiac conduction system in a screen for transcripts highly enriched in the adult Purkinje fiber network system [21]. Here, we show that Cntn2 is first detectable in the developing heart as early as E10.5 in the sinoatrial and atrio-ventricular nodes and soon thereafter in the trabecular compartment of the ventricular myocardium, from which the Purkinje fiber network arises. During late fetal life and thereafter, Cntn2 becomes progressively restricted to the Purkinje cells, as does reporter gene expression driven by the Cntn2 locus [53–55]. Despite this highly regulated pattern of expression, the specific biological function of Cntn2 in the cardiac conduction system is unknown. Loss-of-function mutant mice have no overt cardiac phenotype, conceivably a consequence of redundant expression of other contactin isforms in the heart (unpublished results). Nonetheless, given its unique temporo-spatial profile during heart formation, Cntn2 represented a potentially attractive marker to identify the rare population of ESC-derived cardiogenic cells that assume a Purkinje-cell like phenotype.

The formation of Purkinje-like cells from ESCs shows significant parallels to normal cardiovascular development. We first detect induction of the cardiac-specific MHCα-mCherry reporter at 8 to 12 days of differentiation, followed 14 days later by expression of Cntn2-eGFP. As in the developing heart, ESC-PCs show preferential expression of key cardiac transcription factors, including Nkx2-5, Tbx3, Tbx5 and Irx3 [30, 56–58], as well as a number of genes that impart Purkinje cells with their unique functional properties including Gja5, Hcn4, Scn5a, and Cacna1g [6–9]. Interestingly, we also see preferential expression of Scn10a in ESC-PCs, which encodes the sodium-gated ion channel subunit NaV1.8. The role of this gene in cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmogenesis has been of great interest [59]. We previously reported preferential expression of Scn10a in the murine Purkinje fiber network [60], and recent data suggest that coding region mutations in Scn10a may account for a significant proportion of patients with Brugada syndrome [61]. However, others report minimal expression of Scn10a in the heart and ascribe its association with conduction abnormalities to an intragenic T-box enhancer that modulates expression of the nearby Scn5a gene [62].

The ability to isolate relatively large numbers of ESC and/or pluripotent-derived cardiomyocytes provides significant opportunity for translational applications, including studies of disease mechanism, drug screen, and conceivably, regenerative applications [63–67]. However, the marked structural and functional heterogeneity of cardiomyocytes within different regions of the heart cannot be overlooked and this poses a significant barrier to many of these potential applications. Toward that end, several groups have been developing strategies to isolate distinct sub-populations of cardiomyocytes from complex stem-cell derived derivatives, including sinoatrial cells expressing CD166+ [34]; pace-making cells expressing Hcn4 [68]; and most recently, atrial-like cardiomyocytes expressing high levels of sarcolipin [69]. To our knowledge, however, this is the first successful demonstration extending this approach to Purkinje cells, which are among the rarest sub-population of cells in the heart and as a consequence a cell type that has been particularly refractory to detailed molecular and biochemical analyses.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that a dual reporter gene strategy may be used to identify and isolate the rare ESC-PC from a mixed population of cardiogenic cells. ESC-PC display transcriptional signatures and functional properties comparable to endogenous PCs. Our results suggest that stem-cell derived PC are a feasible new platform for studies of developmental biology, disease pathogenesis and screening for novel anti-arrhythmic therapies. Indeed, one can easily envision utilizing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic editing to introduce putative disease-causing mutations into pluripotent murine as well as human Cntn2-reporter stem cell lines, and testing the consequences of these mutations specifically within the PC environment. Moreover, as methods for cell lineage conversion improve, we can also envision directed conversion of fibroblasts to Purkinje cells, which may be of use treating heritable, acquired and post-surgical damage of the specialized conduction system [70].

Acknowledgments

Grant acknowledgments: This work was supported by NIH R01HL105983, NYSTEM C028115, the Korein Foundation, the B. and R. Knapp Foundation, and the Weisfeld Family Program in Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine to GIF. The Genome Technology Center and the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core of NYU School of Medicine are partially supported by the NIH P30CA016087-32, at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center.

We would like to thank Fanny Liu and Yutong Zhang for technical support.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None;

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

K.M.(1).: concept and design, collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; A.S.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; J.L.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; G.K.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; F.S.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; E.K.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; C.D.(1).: collection and/or assembly of data; S.S.(2).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; L.C.(2).: collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; G.I.F.(1).: concept and design, financial support; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; final approval of manuscript

References

- 1.Singer DH, Lazzara R, Hoffman BF. Interrelationship between automaticity and conduction in Purkinje fibers. Circulation Research. 1967;21:537–558. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maguy A, Le Bouter S, Comtois P, et al. Ion channel subunit expression changes in cardiac Purkinje fibers: a potential role in conduction abnormalities associated with congestive heart failure. Circulation Research. 2009;104:1113–1122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han W, Chartier D, Li D, et al. Ionic remodeling of cardiac Purkinje cells by congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2095–2100. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerrone M, Noujaim SF, Tolkacheva EG, et al. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms in a mouse model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2007;101:1039–1048. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valdivia CR, Tester DJ, Rok BA, et al. A trafficking defective, Brugada syndrome-causing SCN5A mutation rescued by drugs. Cardiovascular research. 2004;62:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desplantez T, Dupont E, Severs NJ, et al. Gap junction channels and cardiac impulse propagation. The Journal of membrane biology. 2007;218:13–28. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vassalle M, Bocchi L, Du F. A slowly inactivating sodium current (INa2) in the plateau range in canine cardiac Purkinje single cells. Experimental physiology. 2007;92:161–173. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyden PA, Hirose M, Dun W. Cardiac Purkinje cells. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2010;7:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaidyanathan R, O’Connell RP, Deo M, et al. The ionic bases of the action potential in isolated mouse cardiac Purkinje cell. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2013;10:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Maio A, Ter Keurs HE, Franzini-Armstrong C. T-tubule profiles in Purkinje fibres of mammalian myocardium. Journal of muscle research and cell motility. 2007;28:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dun W, Boyden PA. The Purkinje cell; 2008 style. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sipido KR, Callewaert G, Carmeliet E. [Ca2+]i transients and [Ca2+]i-dependent chloride current in single Purkinje cells from rabbit heart. The Journal of physiology. 1993;468:641–667. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR, et al. Location of the initiation site of calcium transients and sparks in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. The Journal of physiology. 2001;531:301–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0301i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyden PA, Pu J, Pinto J, et al. Ca(2+) transients and Ca(2+) waves in purkinje cells : role in action potential initiation. Circulation Research. 2000;86:448–455. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirose M, Stuyvers B, Dun W, et al. Wide long lasting perinuclear Ca2+ release events generated by an interaction between ryanodine and IP3 receptors in canine Purkinje cells. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2008;45:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang G, Giovannone SF, Liu N, et al. Purkinje cells from RyR2 mutant mice are highly arrhythmogenic but responsive to targeted therapy. Circulation Research. 2010;107:512–519. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herron TJ, Milstein ML, Anumonwo J, et al. Purkinje cell calcium dysregulation is the cellular mechanism that underlies catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2010;7:1122–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Restivo M, Caref EB, Kozhevnikov DO, et al. Spatial dispersion of repolarization is a key factor in the arrhythmogenicity of long QT syndrome. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2004;15:323–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampson KJ, Iyer V, Marks AR, et al. A computational model of Purkinje fibre single cell electrophysiology: implications for the long QT syndrome. The Journal of physiology. 2010;588:2643–2655. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer V, Sampson KJ, Kass RS. Modeling tissue- and mutation- specific electrophysiological effects in the long QT syndrome: role of the Purkinje fiber. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pallante BA, Giovannone S, Fang-Yu L, et al. Contactin-2 expression in the cardiac Purkinje fiber network. Circulation Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2010;3:186–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.928820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim EE, Shekhar A, Lu J, et al. PCP4 regulates Purkinje cell excitability and cardiac rhythmicity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014 doi: 10.1172/JCI77495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maass K, Shibayama J, Chase SE, et al. C-terminal truncation of connexin43 changes number, size, and localization of cardiac gap junction plaques. Circ Res. 2007;101:1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, et al. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagy A. Manipulating the mouse embryo : a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. p. x.p. 764. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehling HJ, Lacaud G, Kubo A, et al. Tracking mesoderm induction and its specification to the hemangioblast during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2003;130:4217–4227. doi: 10.1242/dev.00589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kita-Matsuo H, Barcova M, Prigozhina N, et al. Lentiviral vectors and protocols for creation of stable hESC lines for fluorescent tracking and drug resistance selection of cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong Q, Ancona N, Hauser ER, et al. Integrating genetic and gene expression evidence into genome-wide association analysis of gene sets. Genome research. 2012;22:386–397. doi: 10.1101/gr.124370.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meysen S, Marger L, Hewett KW, et al. Nkx2.5 cell-autonomous gene function is required for the postnatal formation of the peripheral ventricular conduction system. Developmental biology. 2007;303:740–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashem SI, Claycomb WC. Genetic isolation of stem cell-derived pacemaker-nodal cardiac myocytes. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2013;383:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashem SI, Lam ML, Mihardja SS, et al. Shox2 regulates the pacemaker gene program in embryoid bodies. Stem cells and development. 2013;22:2915–2926. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiese C, Grieskamp T, Airik R, et al. Formation of the sinus node head and differentiation of sinus node myocardium are independently regulated by Tbx18 and Tbx3. Circulation Research. 2009;104:388–397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scavone A, Capilupo D, Mazzocchi N, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived CD166+ precursors develop into fully functional sinoatrial-like cells. Circulation Research. 2013;113:389–398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgoyne RD, Cambray-Deakin MA, Lewis SA, et al. Differential distribution of beta-tubulin isotypes in cerebellum. The EMBO journal. 1988;7:2311–2319. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wianny F, Bourillot PY, Dehay C. Embryonic stem cells in non-human primates: An overview of neural differentiation potential. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2011;81:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takagi Y, Nishimura M, Morizane A, et al. Survival and differentiation of neural progenitor cells derived from embryonic stem cells and transplanted into ischemic brain. Journal of neurosurgery. 2005;103:304–310. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.2.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogun F, Good E, Reich S, et al. Role of Purkinje fibers in post-infarction ventricular tachycardia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:2500–2507. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee HC, Huang KT, Wang XL, et al. Autoantibodies and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2011;8:1788–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinha AM, Schmidt M, Marschang H, et al. Role of left ventricular scar and Purkinje-like potentials during mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation in dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2009;32:286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haissaguerre M, Shah DC, Jais P, et al. Role of Purkinje conducting system in triggering of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Lancet. 2002;359:677–678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haissaguerre M, Extramiana F, Hocini M, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circulation. 2003;108:925–928. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088781.99943.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laurent G, Saal S, Amarouch MY, et al. Multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions: a new SCN5A-related cardiac channelopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.del Balzo U, Rosen MR, Malfatto G, et al. Specific alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes modulate catecholamine-induced increases and decreases in ventricular automaticity. Circulation Research. 1990;67:1535–1551. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.6.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah A, Cohen IS, Rosen MR. Stimulation of cardiac alpha receptors increases Na/K pump current and decreases gK via a pertussis toxin-sensitive pathway. Biophysical journal. 1988;54:219–225. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)82950-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gadsby DC, Wit AL, Cranefield PF. The effects of acetylcholine on the electrical activity of canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circulation Research. 1978;43:29–35. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carmeliet E, Ramon J. Effects of acetylcholine on time-dependent currents in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflugers Archiv :European journal of physiology. 1980;387:217–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00580973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mubagwa K, Carmeliet E. Effects of acetylcholine on electrophysiological properties of rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circulation Research. 1983;53:740–751. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuko A, Bouyain S, van der Zwaag B, et al. Contactins: structural aspects in relation to developmental functions in brain disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2011;84:143–180. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386483-3.00001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuko A, Kleijer KT, Oguro-Ando A, et al. Contactins in the neurobiology of autism. European journal of pharmacology. 2013;719:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bizzoca A, Corsi P, Gennarini G. The mouse F3/contactin glycoprotein: structural features, functional properties and developmental significance of its regulated expression. Cell adhesion & migration. 2009;3:53–63. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.1.7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu QD, Ma QH, Gennarini G, et al. Cross-talk between F3/contactin and Notch at axoglial interface: a role in oligodendrocyte development. Developmental neuroscience. 2006;28:25–33. doi: 10.1159/000090750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delorme B, Dahl E, Jarry-Guichard T, et al. Developmental regulation of connexin 40 gene expression in mouse heart correlates with the differentiation of the conduction system. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1995;204:358–371. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miquerol L, Meysen S, Mangoni M, et al. Architectural and functional asymmetry of the His-Purkinje system of the murine heart. Cardiovascular research. 2004;63:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graham V, Zhang H, Willis S, et al. Expression of a two-pore domain K+ channel (TASK-1) in developing avian and mouse ventricular conduction systems. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2006;235:143–151. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruneau BG, Nemer G, Schmitt JP, et al. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell. 2001;106:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang SS, Kim KH, Rosen A, et al. Iroquois homeobox gene 3 establishes fast conduction in the cardiac His-Purkinje network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:13576–13581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106911108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Weerd JH, Badi I, van den Boogaard M, et al. A large permissive regulatory domain exclusively controls tbx3 expression in the cardiac conduction system. Circulation Research. 2014;115:432–441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park DS, Fishman GI. Navigating through a complex landscape: SCN10A and cardiac conduction. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1460–1462. doi: 10.1172/JCI75240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sotoodehnia N, Isaacs A, de Bakker PI, et al. Common variants in 22 loci are associated with QRS duration and cardiac ventricular conduction. Nature genetics. 2010;42:1068–1076. doi: 10.1038/ng.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Pfeiffer R, et al. Mutations in SCN10A are responsible for a large fraction of cases of Brugada syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Boogaard M, Smemo S, Burnicka-Turek O, et al. A common genetic variant within SCN10A modulates cardiac SCN5A expression. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1844–1852. doi: 10.1172/JCI73140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kraushaar U, Meyer T, Hess D, et al. Cardiac safety pharmacology: from human ether-a-gogo related gene channel block towards induced pluripotent stem cell based disease models. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11:285–298. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.639358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caspi O, Huber I, Gepstein A, et al. Modeling of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:557–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jayawardena TM, Egemnazarov B, Finch EA, et al. MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Circulation Research. 2012;110:1465–1473. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morikawa K, Bahrudin U, Miake J, et al. Identification, isolation and characterization of HCN4-positive pacemaking cells derived from murine embryonic stem cells during cardiac differentiation. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2010;33:290–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Josowitz R, Lu J, Falce C, et al. Identification and purification of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial-like cardiomyocytes based on sarcolipin expression. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang H, Cao N, Spencer CI, et al. Small molecules enable cardiac reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts with a single factor, Oct4. Cell Rep. 2014;6:951–960. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]