Abstract

Objective

To evaluate if preoperative markers of functional status predict postoperative functional outcomes in older women undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

Methods

Prospective cohort study of women aged 60 years or older who underwent surgery for prolapse. Preoperative functional status was measured using number of functional limitations (such as difficulty walking or climbing), American Society of Anesthesiologist class, anemia, and history of recent weight loss. Our primary outcome was the number of postoperative functional limitations and secondary outcomes were failure to return to baseline functional status and length of stay after surgery. We determined the association of preoperative functional status markers with postoperative outcomes using univariable and multivariable regression.

Results

In 127 women, presence of a preoperative functional limitation was a significant predictor of a 0.55 (95% CI 0.36, 0.74) increase in the number of postoperative functional limitations after controlling for age, number of preoperative functional limitations, comorbidities, depression, surgeon, type of procedure, and complications (p < .001). History of recent weight loss and anemia increased risk for failure to return to baseline functional status after controlling for surgeon, type of surgery, and complications (RR 2.44 (95% CI 1.26, 4.71) and RR 2.72 (95% CI 1.29, 5.75), respectively). Preoperative markers associated with longer length of stay after surgery were American Society of Anesthesiologist class III (0.83 day (95% CI 0.20, 1.46) and history of weight loss (0.84 day (95% CI 0.13, 1.54). -.

Conclusion

Preoperative markers of functional status are useful in predicting short-term postoperative functional outcomes in older women undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

INTRODUCTION

An expected 3.4 million women aged 60 years or older will be affected by pelvic organ prolapse (POP) by 2050 (1, 2). Older women are increasingly undergoing POP surgery and are at increased risk for worse postoperative outcomes than younger women due to physiologic vulnerability (3, 4). Sung et al. reported that older women undergoing POP surgery are at increased risk for cardiopulmonary complications (4). Factors that identify women at increased risk for worse outcomes are not known.

Functional status is the ability to perform activities essential to independent living such as walking and lifting ten pounds. Studies from other surgical specialties suggest that even in the absence of postoperative complications, older adults can suffer worsening of postoperative functional status resulting in disability, long-term care needs, and dependency at home (3, 5-7). Objective markers of functional status were useful predictors of worse functional outcomes following cardiac and abdominal surgery in older mostly male patients (3, 8). Data on the postoperative functional status of older women undergoing POP surgery are limited (9, 10). It remains unclear if older women undergoing POP surgery are at increased risk for worse postoperative functional outcomes and whether such outcomes can be predicted by preoperative risk factors.

Our aim is to evaluate if preoperative markers of functional status can predict postoperative functional outcomes undergoing POP surgery. Our a priori hypothesis was that women with worse preoperative functional status would have greater functional limitations, slower return to baseline functional status and longer length of stay after prolapse surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a longitudinal prospective cohort study of older women undergoing surgery for POP between November 2011 and June 2013. Approval was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Our inclusion criteria were English-speaking women, age 60 years or older, planning surgery for POP Stage 2 or greater. We recruited women at their preoperative appointment.

After obtaining informed consent, baseline functional status was assessed preoperatively using the following functional status assessment tools: 1) Activities of Daily Living (11, 12), 2) Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (13) and 3) number of functional limitations using a questionnaire used in the Health and Retirement Study (14, 15) (Appendixes 1 and 2). Functional limitations measured included difficulty in walking several city blocks, walking one city block, walking across a room, sitting for about two hours, getting up from a chair after sitting for long periods, picking up a dime from a table, extending one's arms above shoulder level, pushing or pulling large objects like a living room chair, climbing several flights of stairs, climbing one flight of stairs, lifting 10 pounds, or kneeling, stooping or crouching down. Disability was considered to be present if women required assistance or could not perform one or more of either the Activities of Daily Living or the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. The response for each functional limitation was recorded as ‘no difficulty’, ‘a little difficulty’, ‘some difficulty’, or not applicable. A functional limitation was defined as being present if the response was ‘a little’ or ‘more difficulty’ for each limitation. The number of potential limitations ranged from 0-12.

Frailty has also been shown to be related to postoperative functional status and surgical morbidity and multiple markers of frailty have been described (8, 16). In this study, we women were identified as frail if one of the following markers were present : 1) impaired cognition defined as score <3 on the Mini-Cog Assessment Instrument (17), 2) history of weight loss of 10 or more pounds in last 6 months (16), 3) one or more falls in the last 6 months (18), and 4) depression (defined as score of >1 on the five-item Geriatric Depression Scale score) (16, 19-21), and anemia defined as hematocrit less than 35% (3). The Mini-Cog Assessment is a three word recall for short term memory and drawing a clock face with a specified time. The Mini-Cog was administered by a research assistant. The five-item Geriatric Depression scale has been validated in multiple settings and populations of elderly patients (16, 19-21) and has the benefit of being self-administered.

The number of co-morbidities was assessed using the Functional Co-morbidity Index which assesses co-morbidities such as diabetes, myocardial infarction, hearing loss, and depression and can range in score from 0-18 (22). The Functional Co-morbidity Index is a better predictor of quality of life as measured by the SF-36 than other indices (22). Demographic data, preoperative hematocrit, POP-Quantification Stage (23), and American Society of Anesthesiologist Class (ASA class) were obtained from the patient's chart. ASA class has been previously reported as a useful marker of functional status in orthopedic patients (24) and in women with POP (10).

Surgery for POP was performed by one of three fellowship-trained pelvic reconstructive surgeons in the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Data on the type of surgical procedure for prolapse (open, robotic-assisted, vaginal reconstructive or obliterative), coincidental anti-incontinence surgery, and complications were collected from the operative record.

Postoperative data were collected through a combination of structured questionnaires and medical record review. Functional status using the above described assessment tools was measured at 6 weeks (range 4-8 weeks) and 12 weeks (range 10-14 weeks) after surgery. Data regarding hospital readmissions and admission to skilled nursing facility and post-operative complications were collected by reviewing the inpatient and outpatient medical records and structured questionnaires administered to patients at their postoperative visits or by telephone call.

Complications were graded retrospectively using the modified Dindo Harm Scale (25). For patients who had more than one complication, the most severe complication was used to determine the grade. The modified Dindo Harm Scale is based on the type of therapy needed to correct the complication (25). In brief, using this system, grade 1 is any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacologic, surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic interventions; a grade 2 complication requires pharmacologic treatments; a grade 3 complication requires invasive interventions such as return to the operating room, while a grade 4 complication requires more invasive interventions such as critical care support. The data abstractor grading the complication was blinded to preoperative markers of functional status, frailty and co-morbidity.

Analyses were performed using STATA 12.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). Demographic variables and preoperative functional status markers (number of functional limitations, history of recent weight loss, and ASA class) were summarized using mean or median for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. We used the Friedman test to compare the median number of functional limitations over time (from baseline to 6 and 12 weeks).

We had several outcomes for this study. The primary outcome was the number of postoperative functional limitations. Our secondary outcomes were failure to return to baseline functional status (yes/no) and length of stay. Failure to return to baseline functional status was defined as the presence of two or more additional functional limitations at 12 weeks following surgery as we considered this to be more clinically meaningful in an overall healthy surgical population (5, 6). Length of stay in a medical facility was defined as total number of days in a medical facility including initial hospital length of stay and any additional stays in a skilled nursing facility or during hospital readmission for any cause during the first 12 weeks after surgery.

We determined the association of preoperative functional status markers with postoperative outcomes (functional limitations and length of stay) using univariable and multivariable regression. Coefficients for the number of postoperative functional limitations and number of days length of stay were determined rather than relative risks. We compared continuous preoperative variables between women who did or did not return to baseline functional status using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and categorical variables using the chi-square test. Risk ratios for failure to return to baseline functional status using univariable and multivariable logistic regression were determined. A variable was retained in the final multivariable model if it was associated with postoperative functional limitations with P < .2 (26).

Based on data from the general surgery literature (5), the baseline functional score in older adults undergoing abdominal surgery was 12.7 ± 8.2. In that study, the mean functional status score at 12 weeks postoperatively was 16. At 80% power and a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, a sample size of 126 women was required to detect a change of two or more limitations. We planned to recruit 132 women, allowing for 5% loss-to-follow-up.

RESULTS

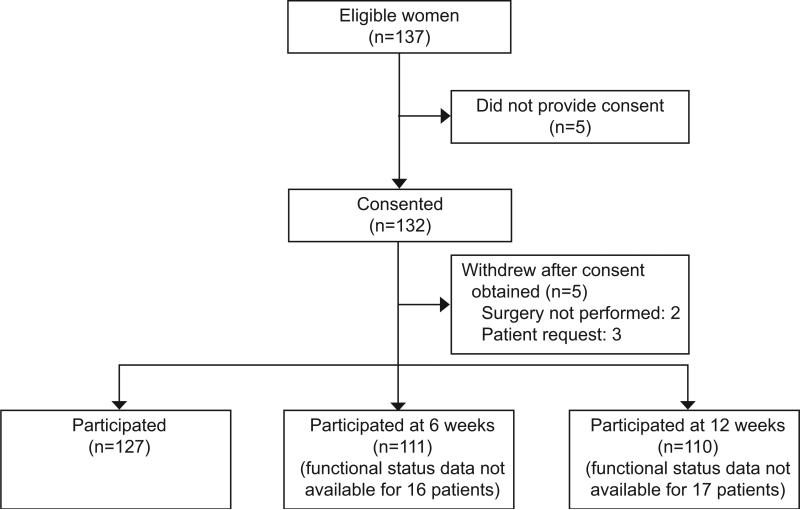

Of the 137 eligible women during the study period, 132 women agreed to participate in the study. Five women withdrew either due to surgical cancellation or patient request, resulting in 127 participants (Figure 1). Functional status data were available in 111/127 women at 6 weeks and in 110/127 women at 12 weeks resulting in a missing data rate of 13.4% (17/127). For these 17 women, the reason for missing data was our inability to administer the functional status instruments within the appropriate window of the 12-week visit (± 2 weeks). All patients with missing data had follow up visits with the surgeon within 6 months postoperatively, allowing us to collect data on complications and length of stay on these patients. Women with missing data were significantly older (72.2 ± 5.7 years) than women for whom complete data were available (68.6 ± 7.2 years, p = .04); however, there were no significant differences in length of stay (3.3 ± 1.4 vs. 2.9 ± .7 days), and severity of post-operative Dindo grade complications (grade 1: 17.7% vs 11.9%; grade 2: 29.4% vs 21.1%; grade 3: 5.9% vs 3.7%, p = .64) between women with and without missing data.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient recruitment

The mean age of the cohort of 127 women was 69.1 ± 7.1 years, and white women comprised 80.6% of the cohort. The median (range) parity was 3 (0-10) and 83.5% had Stage 3 POP. Median Functional Co-morbidity Index score was 3 (range 0-7). Mean BMI was 27.7 ± 4.4 and mean preoperative hematocrit was 39.1% ± 3.6%. The prevalence of frailty markers in the cohort was as follows, impaired cognition 15.8% (20/127), history of 10 or more pounds of weight loss in last 6 months 15.8% (20/127), falls in the last 6 months 14.2% (18/127), anemia 11.8% (15/127) and depression 7.9% (10/127). At least one frailty marker was present in 57/127 (45%) women.

The ASA class distributions were as follows: class I 1.6% (2/127), class II 76.3% (94/127), class III 22.0% (27/127), class IV or higher 0%. The type of surgical procedures performed included 45.7% (58/127) vaginal reconstructive surgery, 36.2% (46/127) robotic-assisted surgery, 14.2% (18/127) open abdominal surgery, and 3.9% (5/127) underwent obliterative surgery. Median (range) preoperative functional limitations for women undergoing each of the above prolapse surgeries were 3.5 (0-9), (3 (0-10), 2 (0-10), and 5 (0-10), respectively (p=.43, Chi square). Of the 127 women, 62 (48.8%) had a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure. During the study, the rate of complications was as follows: Dindo grade 1, 12.7% (16/127); Dindo grade 2, 22.2% (28/127); and Dindo grade 3, 4.0% (5/127).

The median (range) of preoperative functional limitations at baseline in the cohort was 3 (0-10). Of the potential 12 limitations assessed (Appendix 2), half (50%) of the women reported difficulty stooping, kneeling or crouching down while 25% women reported difficulty walking several blocks, getting up from a chair after sitting for a long period of time, climbing several flights of stairs without resting, lifting or carrying a heavy bag of groceries, and pushing or pulling a living room chair. Less than 10% women reported difficulty in other limitations (walking one block, walking across a room, sitting for 2 hours, climbing one flight of stairs without resting, picking up a dime from the table, and reaching or extending arms above shoulder level). Only 11 of 127 women (8.7%) reported preoperative disability in one or more Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; no disabilities in the Activities of Daily Living were reported (Appendix 1).

Table 1 shows the change in the median number of functional limitations over time. At baseline, the median number of limitations in women in ASA class III was lower than the median number of limitations in ASA class I-II; however, 39% (11/28) women in class III had 5 or greater limitations as compared to only 27% (27/99) in class I-II. There was no change in the median number of functional limitations from baseline to 6 and 12 weeks postoperatively for women in ASA class I-II. For women in ASA class III and the cohort as a whole, the median number of functional limitations significantly increased from baseline to 6 weeks and then declined to baseline levels at 12 weeks (Table 1).

Table 1.

Change in functional limitations over time by ASA class.

| Median(range) functional limitations | Baseline | Six weeks postoperatively | Twelve weeks postoperatively | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort (N=99) | 3 (0-10) | 4 (0-11) | 3 (0-11) | .01 |

| ASA Classes I-II (N=78) | 3 (0-10) | 3 (0-11) | 3 (0-11) | .21 |

| ASA Class III (N=21) | 2 (0-10) | 5 (0-10) | 2.5 (0-11) | .01 |

Friedman test; ASA= American Society of Anesthesiologists

On univariable linear regression, factors significantly associated with the number of postoperative functional limitations were age (p < .03), the number of preoperative functional limitations (p < .001), Functional Co-morbidity Index (p < .001) and depression (p < .002). On multivariable linear regression, after controlling for age, number of preoperative functional limitations, Functional Co-morbidity Index, depression, surgeon, type of procedure, and complication severity, the presence of a preoperative functional limitation predicted an increase of 0.55 functional limitations (95% CI 0.36, 0.74; p < .001) after surgery.

For the 110 women for whom 12-week postoperative functional status data were available, 78 (70.9%) women reported the same, less or one more functional limitation than their pre-operative limitations and were classified as having returned to baseline functional status. At the 12-week visit, 32 (29.1%) women reported two or more additional functional limitations and were classified as not returning to baseline functional status. Women who did not return to baseline functional status were significantly more likely to report history of recent weight loss of more than 10 pounds (RR 2.00 (95% CI 1.11, 3.57), p = .03), and anemia (RR 2.30 (95% CI 1.26, 4.22), p=.005) at their baseline visit than women who returned to baseline functional status (Table 2). On multivariable logistic regression after controlling for surgeon, procedures and complication severity, history of weight loss was associated with a 2.44 increased risk (95% CI 1.26, 4.71) and anemia was associated with a 2.72 increased risk (95% CI 1.29, 5.75) of not returning to baseline functional status.

Table 2.

Risk factors for failure to return to baseline functional status

| Preoperative Variables | Returned to baseline Functional Status (N=78) | Failure to return to baseline functional status (N=32) | Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 67 (60-89) | 66 (60-86) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | .97a |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 65 (83.3) | 27 (84.4) | 1.05 (0.47, 2.37) | .89b |

| Parity >3 | 21 (28.7) | 10 (33.3) | 1.14 (0.60, 2.15) | .86b |

| Body Mass Index, median (range) | 27.0 (20.4-39.1) | 28.2 (20.7-38.7) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | .89a |

| Anemia, n (%) | 4 (5.1) | 11 (22.5) | 2.30 (1.26, 4.22) | .005b |

| Hematocrit, median (range) | 39 (32.9-47.6) | 40 (25.0-45.1) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.03) | .92a |

| ASA Class III, n | 19 (24.4) | 5 (15.6) | 0.66 (0.28, 1.53) | .31b |

| POPQ Stage IV, n (%) | 7(9.0) | 2(6.2) | 0.38 (0.09, 1.54) | .22b |

| Urinary Incontinence | 46 (49.0) | 16 (50.0) | 0.77 (0.43, 1.38) | .39c |

| Preoperative functional limitations, median (range) | 3 (0-10) | 2.5 (0-9) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | .31a |

| ADL disability, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| IADL disability, n (%) | 10 (12.8) | 5 (15.6) | 1.17 (0.53, 2.56) | .76b |

| Functional Comorbidity Index, median (range) | 3(0-7) | 2.5 (0-8) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | .80a |

| Impaired Cognition, n (%) | 11 (14.1) | 4 (12.5) | 0.90 (0.36, 2.21) | 1.00b |

| Weight loss, n (%) | 9 (11.5) | 9 (28.1) | 2.00 (1.11, 3.57) | .03b |

| Falls, n (%) | 13 (16.7) | 4 (12.5) | 0.78 (0.31, 1.94) | .77b |

| Depression, n (%) | 6 (7.7) | 3 (9.4) | 1.16 (0.43, 3.07) | .71b |

Wilcoxon rank sum

Fisher's exact

Chi square

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists, ADL = Activities of Daily Living, IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

The median length of stay in a medical facility for the 127 women was 3 (1-15) days. The median (range) length of stay for women who did not return to baseline functional status (3, range (1-9)) was similar to women who did return to baseline functional status (3, range (0-15)) (p = 0.76).

On univariable linear regression, preoperative functional status markers significantly associated with increased length of stay were ASA class III (p = .004), number of functional limitations (p = .05), and weight loss of 10 or more pounds (p = .007), and presence of a Dindo grade 3 complication (p < .001). On multivariable analysis, after adjusting for confounding variables (type of surgical procedure, surgeon, and complication severity), preoperative functional status markers significantly associated with longer length of stay were ASA class III and weight loss (P<.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Preoperative functional status markers associated with increased length of stay in a medical facility

| Preoperative Functional Status Markers | Change in Length of stay (95% Confidence Interval)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| ASA class III | 0.83 day (0.20, 1.46) | .03 |

| Functional limitations | 0.09 day (−0.01, 0.19) | .05 |

| Weight loss | 0.84 day (0.13, 1.54) | .01 |

Multivariate analysis of preoperative markers and controlling for surgeon, procedure and complication severity; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that functional limitations are useful markers for predicting postoperative outcomes following surgery. Specifically, presence of a preoperative limitation predicts an increase in postoperative functional limitations and longer length of stay after surgery. Recent weight loss of 10 or more pounds and anemia also increase likelihood of failure to return to baseline functional status at 12 weeks, while weight loss and ASA class III increase hospital length of stay.

Previous studies (9, 28) have shown decreases in quality of life in women up to 6 weeks after surgery but quality of life improved and was above baseline at 24 weeks postoperatively. Six months may be a long time for high functioning older women to anticipate surgical recovery. Data on trajectory of postoperative recovery between 6 weeks and 6 months can help women with postoperative planning. The present study fills a gap in the literature on functional status outcomes between 6 weeks and 6 months. Our study shows that most women return to baseline function as early as 12 weeks after surgery. For women who fail to return to baseline functional status by 12 weeks, several preoperative functional status markers can identify women at higher risk for slower recovery after surgery: e.g. ASA class III, history of recent weight loss greater than 10 pounds, and preoperative anemia. Surgeons can use this information not only to prepare women for potentially longer hospital stays and postoperative recovery but also to intervene preoperatively to optimize surgical recovery.

ASA class emerged as a clinically useful predictor of postoperative functional status. In our study, ASA class was measured by the anesthesiologist immediately prior to surgery. The ASA classification system is simple, takes only a few minutes to administer, and includes an assessment of comorbidity and physical status (28). For example, ASA class II describes a patient with mild to moderate systemic disease and distress after walking up one flight of stairs whereas class III describes a patient with severe systemic disease and having to stop while climbing a flight of stairs. Given the usefulness of ASA class in predicting postoperative outcomes, clinicians could potentially consider determining the ASA class in the preoperative clinic to counsel women regarding their anticipated postoperative recovery. Surgeons could also use the ASA class to identify patients who require treatment of their co-morbidities and optimization of their functional status in collaboration with a primary care physician or geriatrician.

Two frailty markers, history of recent weight loss and anemia, emerged as predictors of worse postoperative functional outcomes. Though the mean body mass index of patients who failed to return to baseline functional status was higher than those of women who did return to baseline status, a history of recent weight loss was a marker of failure to return to baseline functional status and prolonged length of stay. Both weight loss and low albumin levels are markers of chronic under nutrition and frailty in elderly patients (16, 29). This may potentially explain the mechanism through which weight loss is associated with worse postoperative outcomes. Similarly, anemia has also been identified as a marker of frailty and emerged as predictor of worse outcomes in our study. The presence of these markers will alert both surgeons and patients that full surgical recovery may require longer than three months.

Strengths of our study include its prospective design and use of self-reported measures of functional status that can easily be administered in the clinic during routine preoperative assessment. Such self-reported measures of functional status have demonstrated moderate to high correlation with objective assessments (30).

Our limitations include a missing data rate of 13.4%. It is possible that women with worse outcomes preferentially did not return for postoperative follow up; however, the length of stay and number of postoperative complications in subjects with missing data were not significantly higher than those who contributed completed data. Our follow up period was also short (12 weeks). It is likely that with longer follow up, majority of the women would have returned to baseline functional status and pre-operative functional status markers may be less useful for predicting long term outcomes after surgery. We may also have been underpowered to look at specific functional limitations in a healthier community-dwelling population as our sample size calculation was based on a more frail elderly population. Despite these limitations, our study suggests that several preoperative functional status markers are clinically useful for predicting postoperative functional outcomes in older women undergoing surgery for POP.

Acknowledgements

Funded by a Pelvic Floor Disorders Research Foundation Surgical Research Grant.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Activities of Daily Living Assessment

| Please rate your need for assistance with performing the following activities by checking the appropriate box | |

|---|---|

| ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING | INSTRUMENTAL ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING |

| BATHING | SHOPPING |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | ❑ Can perform without assistance |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | ❑ Can perform with assistance |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) |

| DRESSING | PREPARING MEALS |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | ❑ Can perform without assistance |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | ❑ Can perform with assistance |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) |

| USING THE TOILET | USING THE TELEPHONE |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | ❑ Can perform without assistance |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | ❑ Can perform with assistance |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) |

| TRANSFERRING | MANAGING MEDICATIONS |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | ❑ Can perform without assistance |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | ❑ Can perform with assistance |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) |

| CONTINENCE | MANAGING FINANCES |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | ❑ Can perform without assistance |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | ❑ Can perform with assistance |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) |

| EATING | |

| ❑ Can perform without assistance | |

| ❑ Can perform with assistance | |

| ❑ Cannot perform (with assistance) | |

Appendix 2.

Functional Health Scale

| We are interested in how much difficulty people have with various activities because of a health or physical problem. Exclude any difficulties that you expect to last less than three months. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How difficult is it for you to (please check the appropriate box)... | |||||

| NOT AT ALL DIFFICULT (1) | A LITTLE DIFFICULT (2) | SOMEWHAT DIFFICULT (3) | VERY DIFFICULT/CAN'T DO (4) | DON'T DO (6) | |

| 1)... walk several blocks? | |||||

| 2) ... walk one block? | |||||

| 3) ... walk across a room? | |||||

| 4) ... sit for about 2 hours? | |||||

| 5) ... get up from a chair after sitting for long periods? | |||||

| 6) ... climb several flights of stairs without resting? | |||||

| 7) ... climb one flight of stairs without resting? | |||||

| 8)... lift or carry weights over 10 pounds, like a heavy bag of groceries? | |||||

| 9) ... stoop, kneel, or crouch? | |||||

| 10) ... pick up a dime from a table? | |||||

| 11) ...reach or extend your arms above shoulder level? | |||||

| 12) ...pull or push large objects like a living room chair? | |||||

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

Presented at the 14th AUGS/IUGA Scientific Meeting in Washington, D.C., July 22-26, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau [August 14, 2011];Population Division. Projections of the population by selected age groups and sex for the United States. 2010-2050 Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf.

- 2.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, Church SD, McFann KK, Pfister SM, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Ann Surg. 2009;250:449–55. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b45598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung VW, Weitzen S, Sokol ER, Rardin CR, Myers DL. Effect of patient age on increasing morbidity and mortality following urogynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finlayson E, Zhao S, Boscardin WJ, Fries BE, Landefeld CS, Dudley RA. Functional status after colon cancer surgery in elderly nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:967–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:S301–4.30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amemiya T, Oda K, Ando M, Kawamura T, Kitagawa Y, Okawa Y, et al. Activities of daily living and quality of life of elderly patients after elective surgery for gastric and colorectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2007;246:222–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and co-morbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter HE, Redden DT, Duxbury AS, Granieri EC, Halli AD, Goode PS. Pelvic floor surgery in the older woman: Enhanced compared with usual preoperative assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:800–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154920.12402.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer JA, Northington GN, Harvie HS, Segal S, Johnson JC, Arya LA. Functional status and post-operative morbidity in older women with prolapse. J Urol. 2013;190:948–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brorsson B, Asberg KH. Katz index of independence in ADL. Reliability and validity in short-term care. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1984;16:125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Documentation of physical function measured in the Health and Retirement Study and the asset and health dynamics among the oldest old study. Vol. 2004. Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: [August 14, 2011]. pp. 14–21. Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/docs/userg/dr-008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner DF, Brown TH. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1236–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1451–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2011;173:489–95. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinaldi P, Mecocci P, Benedetti C, Ercolani S, Bregnocchi M, Menculini G. Catani Met al. Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:694–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JOL, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female POP and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Hooper NM, Frampton C. The relationship between the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical rating and outcome following total hip and knee arthroplasty: an analysis of the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg AM. 2012;94:1065–70. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber MD, Kenton K. Wen Ye. Validation of the Activities Assessment Scale in Women undergoing Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:205–210. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31825e6422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MM, Duncan PG, Tate RB. Does anesthesia contribute to operative mortality? JAMA. 1988;260:2859–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazzard WR. Depressed albumin and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: Signposts along the final common pathway of frailty. JAGS. 2001;49:1253–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, Chylack LT., Jr. Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:813–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]