Abstract

The calcium-sensing receptor (CaR), a seven-transmembrane domain receptor belonging to the G protein-coupled receptor family, is responsible for calcium-mediated signalling initiated at the surface of parathyroid cells that controls the synthesis and secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH). Expression of the CaR is downregulated in animal models of uraemia and in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT). Cinacalcet is a type II calcimimetic agent that acts as an allosteric modulator of CaR signalling. It has been shown in clinical studies to improve control of serum PTH levels and in preclinical studies to attenuate SHPT disease progression and parathyroid hyperplasia. Cinacalcet represents the first of this novel class of agents and a major advance in the treatment of SHPT.

Keywords: calcium-sensing receptor, chronic kidney disease, cinacalcet, parathyroid hormone, secondary hyperparathyroidism

The calcium-sensing receptor

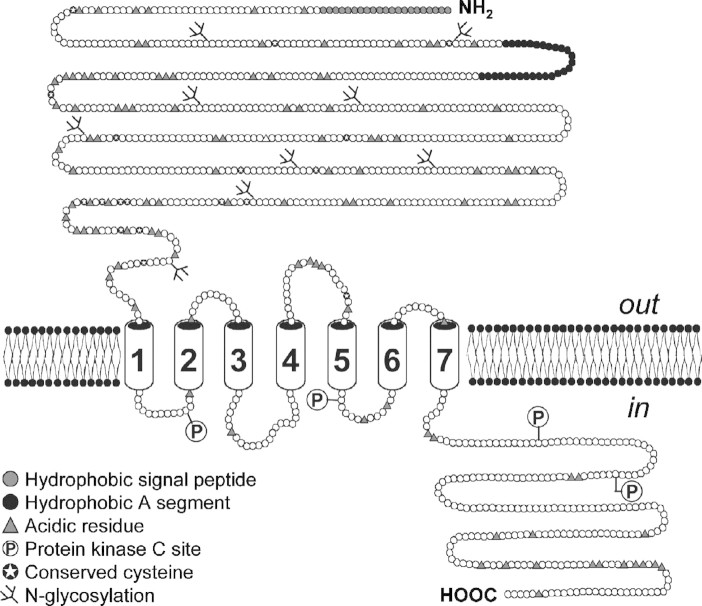

The calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) plays a central role in the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT). The CaR is a seven-transmembrane domain receptor belonging to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily [1]. The CaR was cloned first from bovine [1] and then from human [2] parathyroid cells, as well as from rat kidney cells [3]. It is expressed on the surface of parathyroid cells and consists of three principal structural domains: an N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) containing the calcium-binding site(s) [4]; a membrane-spanning domain and a cytosolic domain, which mediates intracellular signalling (Figure 1) [1,2]. The CaR is coupled to a number of intracellular signalling pathways [5–7], and its activation typically elicits an increase in intracellular calcium [8,9]. Thus, in this context, calcium is both the extracellular ligand and an intracellular second messenger. The CaR has been shown to dimerize [10] at the cell surface, and key cysteine residues mediate this dimerization process [11].

Fig. 1.

The extracellular CaR. The CaR consists of three molecular domains: an extracellular ligand-binding domain; a transmembrane domain and a cytosolic domain, which mediates intracellular signalling. Adapted with permission from Brown et al. [1].

Calcium binds to the inside pocket of two lobes in the ECD, which are separated by a hinge region [12,13]. Another hinge region between membrane-spanning helices 6 and 7 and, particularly, a proline residue (P823) in TM6 has been identified as a key structural element involved in calcium signalling [14]. The bilobed structure of the ECD for another related GPCR, the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1, has been elucidated through crystallographic studies [15]. Homology modelling of the CaR based on the mGluR1 structure has confirmed several structural similarities [12,13], including common cysteine residues that mediate receptor dimerization and a set of polar residues involved in calcium coordination.

Unlike intracellular calcium-binding proteins, which contain consensus calcium-binding sequences and have a very high affinity for calcium, the CaR does not contain conserved structural motifs for high-affinity binding of calcium at micromolar or nanomolar concentrations. The relatively low affinity of the CaR for calcium (50% effective concentration of ∼3 mmol/L in cultured cells) [1,4] is consistent with its role as a sensor of extracellular circulating calcium levels; normal serum-free ionized calcium levels are in the range of 1.15 to 1.36 mmol/L (i.e. 4.6– 5.4 mg/dL) [16].

Pathophysiology and characteristics of SHPT

Parathyroid gland cell proliferation and hyperplasia

A major characteristic of SHPT is increased parathyroid cell proliferation. As chronic kidney disease (CKD) progresses, this increase in cell proliferation results in the development of diffuse parathyroid gland hyperplasia and subsequently nodular hyperplasia [17,18]. Both hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia appear to stimulate parathyroid cell proliferation or hyperplasia [19,20], with the effects of calcium being mediated by the actions of p21 (Waf1) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-alpha, a cytokine that mediates cell growth in normal and malignant tissue [21]. The protein p21 (Waf1 or Cip1) is an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases [22], which stimulate a progression into S phase and active replication [23,24]. Induction of p21 and downregulation of TGF-alpha are thought to be responsible for the antiproliferative effects of vitamin D [21,25]. When a low-phosphate diet was imposed on uraemic 5/6 nephrectomized rats, parathyroid cell proliferation was halted with a concomitant induction of p21 and reduced expression of TGF-alpha [26]. The expression of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), an indicator of mitotic status, was inversely correlated with p21 and directly correlated with TGF-alpha [21,26].

Because inhibition of apoptosis is frequently associated with hyperplasia and dysregulated cell growth, it is important to consider the influence of potential treatments for SHPT on this natural mode of cell death. An in vitro study examining the effects of calcitriol (D3) on cell proliferation and apoptosis has shown that calcitriol inhibits both parathyroid cell proliferation and apoptosis in normal glands from dogs [27], thus having a net effect of neither increasing nor decreasing parathyroid gland size. In parathyroid glands from patients with SHPT incubated in culture medium, only high concentrations of calcitriol were able to inhibit proliferation and apoptosis [27].

Receptor expression

A decline in CaR expression is characteristic of hyperplastic parathyroid cells from uraemic animal models [28,29] and also of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) and SHPT [30–32]. A study in uraemic rats indicated that hyperplasia precedes the decline in CaR expression [28]. Therefore, CaR expression is a key measure of disease status and progression. A 41% decrease (P < 0.01) in CaR protein expression was observed in 5/6 nephrectomized rats on a high-phosphate diet, compared with control animals [29]. This study also showed that the decline in CaR expression was most noticeable in actively proliferating cells and that a high-phosphate diet induced parathyroid hyperplasia.

In studies of human parathyroid adenoma and hyperplastic glands from uraemic patients, these tissues showed a 59% decrease in CaR expression compared with normal glands [30]. In another large study examining tissue from a total of 50 parathyroid glands from 23 haemodialysis patients with SHPT, tissue with the lowest CaR expression levels secreted the most parathyroid hormone (PTH) [31]. Interestingly, low CaR expression was associated with a decreased response to both inhibitory effects of high calcium levels and receptor activation by low calcium levels. Furthermore, an inverse relationship between gland weight and CaR gene expression (P < 0.05) and between CaR expression levels and calcium setpoint (P < 0.01) was observed [31]. Consistent with these findings, calcitriol was effective in preventing parathyroid hyperplasia in early renal failure but ineffective in reducing parathyroid cell proliferation after SHPT was established [33]. These data offer a compelling illustration of the difficulty of reversing SHPT in hyperplastic tissue. Once CaR (and vitamin D receptor [VDR]) expression are decreased and parathyroid cell proliferation advances, traditional therapies, such as calcium and calcitriol, may be ineffective because of the refractory responses to these treatments.

Calcimimetic agents for the treatment of SHPT

Mechanism of action

Because the CaR is the main regulator of parathyroid response to serum calcium and plays a central role in the pathogenesis of SHPT, it is an attractive therapeutic target. However, because the CaR belongs to the GPCR family, some of which are also activated by extracellular di- or polyvalent cations [4], one of the main challenges in developing potential modulators of the CaR involves accomplishing a high level of specificity for CaR binding. The term calcimimetics has been coined for those compounds that can modulate the activity of calcium receptors [8]. Type I calcimimetics include inorganic cations, polyamines and aminoglycosides that bind to the calcium-binding site on the receptor and are capable of activating the CaR in the absence of extracellular calcium. Some type I calcimimetics are Mg2+, Gd3+, neomycin and spermine [1,8,34]. Type II calcimimetics are organic compounds that bind to regions within the membrane-spanning domain of the CaR and have the potential to increase the sensitivity of the CaR to calcium, in effect lowering the threshold for receptor activation by calcium [35]. They are thus, by nature, allosteric modulators.

Cinacalcet is a potent and selective type II calcimimetic agent. Treatment with cinacalcet has been demonstrated to increase the mobilization of intracellular calcium in human embryonic kidney 293 cells transfected with the human parathyroid CaR [35]. This effect of cinacalcet was dependent on the presence of extracellular calcium; cinacalcet had no influence on PTH secretion in cultured cells under conditions of low (<0.1 mmol/L) calcium [35,36]. These in vitro data demonstrate that cinacalcet is an allosteric modulator of the CaR. It is likely that its in vivo effects are also dependent on an extracellular calcium-initiated signal.

Control of disease progression

PTH expression and secretion

Both PTH expression and secretion are regulated at multiple levels. Although both vitamin D [37,38] and extracellular calcium [38,39] can act to downregulate transcription of the PTH gene in normal parathyroid cells, low extracellular calcium promotes the stabilization of the PTH mRNA transcripts [40], resulting in increased PTH synthesis. Calcimimetics amplify the calcium-mediated signalling from the cell surface and can be used to normalize serum PTH when serum calcium levels prevent normal regulation of PTH or calcium sensing is impaired in SHPT [41].

Type II calcimimetics produced concentration-dependent decreases in PTH secretion from cultured bovine parathyroid cells at nanomolar concentrations [8]. Long-term oral administration of cinacalcet (10 mg/kg/day) in 5/6 nephrectomized rats significantly decreased serum PTH levels over 4 weeks, supporting the efficacy of cinacalcet as a CaR signal modulator in vivo [42]. A dose-dependent suppression of PTH by cinacalcet has also been observed in a recent study examining primary human parathyroid cells from patients with PHPT or SHPT, in which immunohistochemical analysis revealed reduced expression of both the VDR and CaR [43]. Pharmacokinetic exposure data show similar concentration-time profiles in rats receiving the 10-mg/kg/day dose and patients receiving clinical doses of cinacalcet (75 mg) [35,44]. Cinacalcet lowered PTH release by 61% in both PHPT and SHPT cells, demonstrating that despite reduced CaR expression, cinacalcet can effectively suppress PTH release [43].

CaR expression

Calcimimetic therapy has been shown to directly influence CaR expression, which is significantly reduced in SHPT. In a rat 5/6 nephrectomy model of CKD, rats fed a high-phosphate diet rapidly developed SHPT and exhibited a 75% reduction in parathyroid gland CaR mRNA expression and a 79% reduction in parathyroid gland CaR protein expression after 9 weeks compared with sham-operated controls fed a standard diet [45]. In contrast, when nephrectomized rats were fed a high-phosphate diet for 9 weeks and also orally administered R-568 (100 μg/kg/day) for the final week of the treatment period, CaR expression was not reduced compared with the sham-operated control group.

Parathyroid cell proliferation

Calcimimetic treatment has also been shown to reduce parathyroid cell proliferation and attenuate increases in parathyroid gland weight in rat 5/6 nephrectomy models of CKD. Typically, 5/6 nephrectomy results in a marked increase in the number of PCNA-positive (i.e. proliferating) cells in the parathyroid gland compared with sham-operated controls [45]. Treatment with R-568 (100 μg/kg/day for 1 week) and with cinacalcet (5 or 10 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) has been demonstrated to prevent this increase in parathyroid cell proliferation [42,45] (Figure 2). In addition to their effect on cell proliferation, these treatments also attenuated the development of parathyroid enlargement. In both studies, parathyroid gland weight was significantly reduced in R-568- and cinacalcet-treated animals compared with vehicle-treated animals [42,45].

Fig. 2.

Influence of cinacalcet on parathyroid cell proliferation in 5/6 nephrectomized (Nx) rats. Rats were administered either vehicle or cinacalcet at the indicated concentrations for 4 weeks, beginning 6 weeks after nephrectomy. *P < 0.001. Adapted with permission from Colloton et al. [42].

These effects of cinacalcet on parathyroid cell proliferation and hyperplasia may be mediated through alterations in the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p21, which inhibits the activity of a number of cyclin-dependent kinases, thereby controlling the entry of cells into the actively dividing S phase [22] (Figure 3). Expression of p21 is suppressed in parathyroid hyperplasia [26]. In 5/6 nephrectomized rats, treatment with cinacalcet for 5 weeks significantly (P < 0.03) increased expression of p21 [46]. Thus, cinacalcet treatment may, in effect, help reset the proliferating cell cycle, bringing proliferating hyperplastic cells back under normal cell-cycle control.

Fig. 3.

Regulation of parathyroid gland cell cycle progression. Entry of parathyroid cells into the actively dividing S phase is regulated by the effects of p21 on cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). Cdc2, cell division cycle 2 protein.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the effects of cinacalcet are not limited to decreasing the release of PTH, but extend to altering the expression of the CaR and reducing parathyroid cell proliferation and hyperplasia. These data suggest that cinacalcet could arrest—and perhaps even reverse—the development of SHPT in CKD patients.

Conclusions

The CaR clearly plays a central role in the onset and progression of SHPT because it mediates the signals that influence PTH synthesis and secretion. With the advent of clinically effective type II calcimimetic agents and the introduction of cinacalcet, CKD patients with SHPT now have an additional treatment option. Type II calcimimetics have been shown to effectively control PTH secretion in preclinical studies and in patients with SHPT and also to impede parathyroid gland hyperplasia. Moreover, because cinacalcet and vitamin D have complementary mechanisms of action, they may be used in conjunction as therapy for SHPT. Type II calcimimetics, therefore, represent a major advance in the treatment of SHPT. As the first clinically effective and available agent in this new class, cinacalcet holds great promise for improving clinical outcomes in CKD patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dylan Harris and Ali Hassan for providing medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. This supplement and online open access are sponsored by Amgen Inc.

Conflict of interest statement. Daniela Riccardi has received a grant from Amgen. Dave Martin is an employee of Amgen.

References

- 1.Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature. 1993;366:575–580. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett JE, Capuano IV, Hammerland LG, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of human parathyroid calcium receptor cDNAs. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12919–12925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riccardi D, Park J, Lee WS, Gamba G, Brown EM, Hebert SC. Cloning and functional expression of a rat kidney extracellular calcium/polyvalent cation-sensing receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:131–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauner-Osborne H, Jensen AA, Sheppard PO, O'Hara P, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. The agonist-binding domain of the calcium-sensing receptor is located at the amino-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18382–18386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kifor O, Diaz R, Butters R, Brown EM. The Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaR) activates phospholipases C, A2, and D in bovine parathyroid and CaR-transfected, human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:715–725. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kifor O, MacLeod RJ, Diaz R, et al. Regulation of MAP kinase by calcium-sensing receptor in bovine parathyroid and CaR-transfected HEK293 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F291–F302. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.2.F291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofer AM, Brown EM. Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:530–538. doi: 10.1038/nrm1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemeth EF, Steffey ME, Hammerland LG, et al. Calcimimetics with potent and selective activity on the parathyroid calcium receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nemeth EF, Scarpa A. Rapid mobilization of cellular Ca2+ in bovine parathyroid cells evoked by extracellular divalent cations. Evidence for a cell surface calcium receptor. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5188–5196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldsmith PK, Fan GF, Ray K, et al. Expression, purification, and biochemical characterization of the amino-terminal extracellular domain of the human calcium receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11303–11309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ray K, Hauschild BC, Steinbach PJ, Goldsmith PK, Hauache O, Spiegel AM. Identification of the cysteine residues in the amino-terminal extracellular domain of the human Ca2+ receptor critical for dimerization. Implications for function of monomeric Ca2+ receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27642–27650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silve C, Petrel C, Leroy C, et al. Delineating a Ca2+ binding pocket within the venus flytrap module of the human calcium-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37917–37923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Zhou Y, Yang W, Butters R, et al. Identification and dissection of Ca2+-binding sites in the extracellular domain of Ca2+-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(26):19000–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701096200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, McLarnon SJ, Mora S, et al. A region in the seven-transmembrane domain of the human Ca2+ receptor critical for response to Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5113–5120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunishima N, Shimada Y, Tsuji Y, et al. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 2000;407:971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.K/DOQI Guidelines. 2003. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:S1–S201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez M, Nemeth E, Martin D. The calcium-sensing receptor: a key factor in the pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:F253–F264. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00302.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tominaga Y. Mechanism of parathyroid tumourigenesis in uraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(Suppl 1):63–65. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.suppl_1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naveh-Many T, Rahamimov R, Livni N, Silver J. Parathyroid cell proliferation in normal and chronic renal failure rats. The effects of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1786–1793. doi: 10.1172/JCI118224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slatopolsky E, Finch J, Denda M, et al. Phosphorus restriction prevents parathyroid gland growth. High phosphorus directly stimulates PTH secretion in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2534–2540. doi: 10.1172/JCI118701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cozzolino M, Lu Y, Finch J, Slatopolsky E, Dusso AS. p21WAF1 and TGF-alpha mediate parathyroid growth arrest by vitamin D and high calcium. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2109–2117. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Lukas J, et al. Regulation of the cell cycle by the cdk2 protein kinase in cultured human fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:101–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuura I, Denissova NG, Wang G, He D, Long J, Liu F. Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature. 2004;430:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dusso A, Cozzolino M, Lu Y, Sato T, Slatopolsky E. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D downregulation of TGFalpha/EGFR expression and growth signaling: a mechanism for the antiproliferative actions of the sterol in parathyroid hyperplasia of renal failure. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dusso AS, Pavlopoulos T, Naumovich L, et al. p21(WAF1) and transforming growth factor-alpha mediate dietary phosphate regulation of parathyroid cell growth. Kidney Int. 2001;59:855–865. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059003855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canalejo A, Almaden Y, Torregrosa V, et al. The in vitro effect of calcitriol on parathyroid cell proliferation and apoptosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1865–1872. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11101865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritter CS, Finch JL, Slatopolsky EA, Brown AJ. Parathyroid hyperplasia in uremic rats precedes down-regulation of the calcium receptor. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1737–1744. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown AJ, Ritter CS, Finch JL, Slatopolsky EA. Decreased calcium-sensing receptor expression in hyperplastic parathyroid glands of uremic rats: role of dietary phosphate. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1284–1292. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kifor O, Moore FD, Wang P, et al. Reduced immunostaining for the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in primary and uremic secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1598–1606. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canadillas S, Canalejo A, Santamaria R, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor expression and parathyroid hormone secretion in hyperplastic parathyroid glands from humans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2190–2197. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gogusev J, Duchambon P, Hory B, et al. Depressed expression of calcium receptor in parathyroid gland tissue of patients with hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 1997;51:328–336. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szabo A, Merke J, Beier E, Mall G, Ritz E. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 inhibits parathyroid cell proliferation in experimental uremia. Kidney Int. 1989;35:1049–1056. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagano N. Pharmacological and clinical properties of calcimimetics: calcium receptor activators that afford an innovative approach to controlling hyperparathyroidism. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:339–365. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemeth EF, Heaton WH, Miller M, et al. Pharmacodynamics of the type II calcimimetic compound cinacalcet HCl. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:627–635. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemeth EF. Calcimimetic and calcilytic drugs: just for parathyroid cells? Cell Calcium. 2004;35:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silver J, Naveh-Many T, Mayer H, Schmelzer HJ, Popovtzer MM. Regulation by vitamin D metabolites of parathyroid hormone gene transcription in vivo in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1296–1301. doi: 10.1172/JCI112714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silver J, Moallem E, Kilav R, Sela A, Naveh-Many T. Regulation of the parathyroid hormone gene by calcium, phosphate and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:40–44. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.suppl_1.40. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naveh-Many T, Silver J. Regulation of parathyroid hormone gene expression by hypocalcemia, hypercalcemia, and vitamin D in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1313–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI114840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moallem E, Kilav R, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. RNA-protein binding and post-transcriptional regulation of parathyroid hormone gene expression by calcium and phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5253–5259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonsen JE, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL. A calcimimetic agent acutely suppresses parathyroid hormone levels in patients with chronic renal failure. Rapid communication. Kidney Int. 1998;53:223–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colloton M, Shatzen E, Miller G, et al. Cinacalcet HCl attenuates parathyroid hyperplasia in a rat model of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 2005;67:467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawata T, Imanishi Y, Kobayashi K, et al. Direct in vitro evidence of the suppressive effect of cinacalcet HCl on parathyroid hormone secretion in human parathyroid cells with pathologically reduced calcium-sensing receptor levels. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:300–306. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Padhi D, Harris RZ, Salfi M, Sullivan JT. No effect of renal function or dialysis on pharmacokinetics of cinacalcet (Sensipar/Mimpara) Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:509–516. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mizobuchi M, Hatamura I, Ogata H, et al. Calcimimetic compound upregulates decreased calcium-sensing receptor expression level in parathyroid glands of rats with chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2579–2587. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000141016.20133.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis J, Miller J, Shatzen E, Henley C, Martin D. Cinacalcet HCl increases expression of p21 in the parathyroid and reversibly inhibits parathyroid hyperplasia in a rodent model of CKD (Abstract) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:v205. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]