Abstract

Introduction

Illicit substance-use is a substantial public health concern, contributing over $150 billion in costs annually to Americans. A complex disease, a substance-use disorder affects neural circuits involved in reinforcement, motivation, learning and memory, and inhibitory control.

Areas covered

The modulatory influence of dopamine in mesocorticolimbic circuits contributes to encoding the primary reinforcing effects of substances and numerous studies suggest that aberrant signaling within these circuits contributes to the development of a substance-use disorder in some individuals. Decades of research focused on the clinical development of medications that directly target dopamine receptors has led to recent studies of agonist-like dopaminergic treatments for stimulant-use disorders and, more recently, cannabis-use disorder. Human studies evaluating the efficacy of dopaminergic agonist-like medications to reduce reinforcing effects and substance-use provide some insight into the design of future pharmacotherapy trials. A search of PubMed using specific brain regions, medications, and/or the terms ‘dopamine’, ‘cognition’, ‘reinforcement’, ‘cocaine’, ‘methamphetamine’, ‘amphetamine’, ‘cannabis’, ‘treatment/pharmacotherapy’, ‘addiction/abuse/dependence’ identified articles relevant to this review.

Expert opinion

Conceptualization of substance-use disorders and their treatment continues to evolve. Current efforts increasingly focus on a strategy fostering combination pharmacotherapies that target multiple neurotransmitter systems.

Keywords: cannabis, cocaine, dopamine, mesocorticolimbic, methamphetamine

1. Introduction

A substance-use disorder (SUD) is a complex recurring brain disease characterized by a pathological pattern of behaviors related to use of the substance [1]. For example, SUDs are associated with low academic achievement, early school dropout, delinquency, legal problems, and unemployment. In addition, SUDs are associated with a risk for the development of a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Although comorbid psychiatric disorders sometimes precede the SUD, substance-use often exacerbates the other psychiatric disorder, while other times the SUD triggers the comorbid disorder – particularly in susceptible individuals. The pathophysiology of SUDs, as well as other psychiatric disorders, indicates perturbations within the central dopaminergic system as potential targets of pharmacotherapies. This review describes the negative impact of SUDs, the role of dopamine (DA) in the mesocorticolimbic system, and neuroadaptations within the dopaminergic mesocorticolimbic system in cocaine, methamphetamine/amphetamine (METH/AMPH), and cannabis-use disorders. The efficacy of dopaminergic pharmacotherapies for these SUDs in the context of human laboratory studies and clinical trial outcomes are then considered. As such, this is not a comprehensive review of either the dopaminergic or the mesocorticolimbic systems or of all data relating to the pathophysiology of SUDs.

In 2011, approximately 8.7% of the population aged 12 or older (22.5 million Americans) were current (past month) illicit substance users and 2.5% met SUD criteria [2]. Cannabis accounted for 63.8% (4.2 million), cocaine 1.3% and AMPH-type stimulants (METH and non-medical AMPH-type stimulants) 0.5% of those classified with a SUD [2]. Estimates according to the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) indicate that of people who reported receiving treatment for an illicit SUD, approximately 29% received treatment for cannabis-use, 14% for cocaine-use and 10% for stimulant-use [2,3]. The TEDS also reveals that 44.2% of cannabis, 71.3% of cocaine, and 58.2% of stimulant user admissions reported having at least one prior treatment episode [3]. Moreover, according to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, out of the nearly 1.9 million emergency department visits in 2010 that involved substance misuse, cocaine was the most commonly involved illicit substance (211 visits), followed by cannabis (151), heroin (93) and AMPHs (55) [4]. In fact, the combined medical, economic, criminal and social impact of illicit substance-use contributes $151.4 billion in costs annually to Americans [5]. Considering these statistics, it is not surprising that a recent multi-criteria decision analysis model, which incorporated a range of harms caused by the misuse of substances, found that heroin was the most harmful illicit substance overall, followed by cocaine, METH/AMPH and cannabis [6]. The focus of this review is on the latter three because, while there are approved pharmacotherapies for opiate-use disorders, there are no FDA-approved medications for cocaine, METH/AMPH or cannabis-use disorders.

2. The mesocorticolimbic DA system

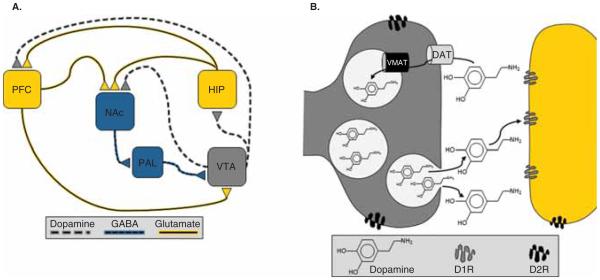

As depicted in Figure 1A, mesocorticolimbic DA-containing neurons project from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the mesencephalon to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of the ventral striatum, hippocampus (HIP), prefrontal cortex (PFC) and other brain regions (e.g., the amygdala). Two classes of G-protein-coupled receptors, known as D1- and D2-like families, mediate the effects of DA on neuronal activity. D1-like receptors (D1Rs) include D1 and D5 receptor subtypes and D2-like receptors (D2Rs) comprise D2, D3 and D4 receptor subtypes. Postsynaptic terminals in the NAc, HIP and PFC express both D1 and D2Rs, while presynaptic DA terminals also express D2 autoreceptors and, therefore, regulate DA release and synthesis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A. Mesocorticolimbic Dopamine System. Simplified diagram of dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), hippocampus (HIP), and prefrontal cortex (PFC) that regulate the flow of novelty- and reinforcement-related properties of stimuli. Dopamine (DA) neurons at baseline are either in an inactive state, which is mediated by the inhibitory inputs from the ventral pallidum (PAL) to the VTA, or in an active state characterized by spontaneous or ‘tonic’ firing of action potentials. Tonic firing is thought to mediate a slow and spatially distributed signal that supplies basal levels of extrasynaptic endogenous dopamine. Spontaneously active neurons can be induced to fire in a phasic pattern, which mediates a fast and spatially restricted signal that selectively affects intrasynaptic DA receptors. B. Dopamine release, reuptake, & receptors. Once released, tonic or extrasynaptic DA diffuses away from the synaptic cleft and signals primarily via activation of D2-like receptors (D2R), while phasic or intrasynaptic DA is subject to reuptake by the DA transporter (DAT) and therefore signals primarily via activation of D1-like receptors (D1R).

Under basal conditions, some DA neurons are in an inactive, hyperpolarized state that is mediated by inhibitory GABAergic inputs from the ventral pallidum, while other neurons are driven by an intrinsic pacemaker to spontaneously fire action potentials in a ‘tonic’ or single-spike pattern [7]. These spontaneously active or tonic DA neurons, but not the hyperpolarized neurons, can be induced to fire action potentials in a ‘phasic’ or burst firing pattern. Phasic DA release/signaling occurs in a fast, transient and spatially restricted manner that primarily affects intrasynaptic receptors, because phasic DA is subject to immediate reuptake into presynaptic terminals through the DA transporter (DAT) [7]. In contrast, the DAT does not heavily influence tonic levels because DA diffuses away from the terminal. As such, tonic DA mediates a slow and spatially distributed signal that provides baseline, or steady-state levels, of endogenous DA concentrations. Importantly, although a preponderance of tonic DA escapes from the synapse, synaptic levels of tonic DA are sufficient to stimulate the high-affinity presynaptic D2Rs expressed on afferent terminals from the PFC [7].

2.1 Regulation of the mesocorticolimbic DA system and behavioral significance

A complete review of the neural circuits involved in signaling, encoding and utilizing the reinforcement value of a stimulus to optimize future decision-making is beyond the scope of this review. Nonetheless, it is clear that dopaminergic axon terminations in NAc, HIP and PFC regions play distinct, yet integrated, roles in these processes.

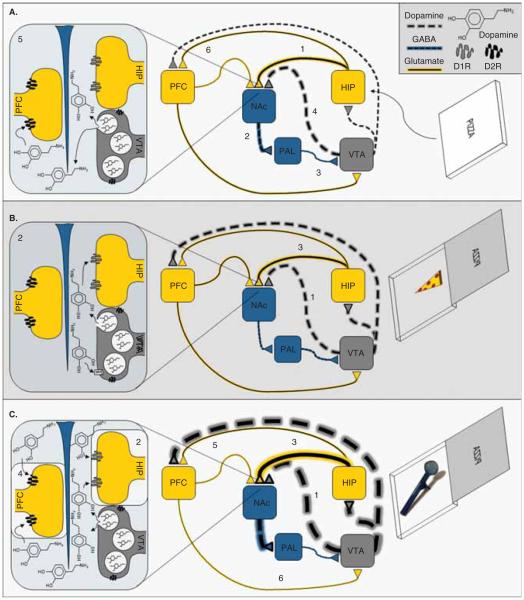

Because glutamatergic inputs from the HIP and PFC synapse on the same GABAergic neurons in the NAc as dopaminergic projections from the VTA, the NAc is anatomically positioned to indicate the appetitive value of a stimulus and act as the substrate whereby the primary value of a stimulus can be encoded by the HIP. As shown in Figure 2A, novel salient stimuli enter this network at the HIP, activating excitatory glutamatergic projections to the NAc; the subsequent stimulation of inhibitory GABAergic projection neurons from the NAc to the ventral pallidum causes disinhibition of the VTA [8], which increases the number of spontaneously active DA neurons and hence, tonic levels of DA [7]. Increased levels of extracellular DA in the NAc stimulates postsynaptic D2Rs on glutamatergic afferents from the PFC, attenuating PFC input to the NAc and thereby preferentially engaging the HIP to encode reinforcing values of novel stimuli [7]. In addition, because a novel stimulus increases the number of spontaneously active DA neurons through a hippocampal-dependent process, and only spontaneously active DA neurons can transition to the phasic firing mode, the HIP also determines the number of neurons that can be further modulated by novel reinforcing stimuli to induce a phasic burst response [7]. Therefore, increased levels of tonic DA in the NAc are thought to directly attenuate PFC input and thereby preferentially engage the HIP to encode reinforcing values of novel stimuli, and regulate the responsiveness of DA neurons and its impact on reinforcement-directed behavior by causing inactive DA neurons to transition into tonic firing mode.

Figure 2.

A. Novel Salient StimuliInduced Activation of the VTA. A novel salient stimulus that could potentially lead to positive reinforcement (e.g., a potential food reward) enters the dopaminergic mesocorticolimbic network at the HIP. This causes activation of the excitatory glutamatergic projections from the HIP (1) to the NAc. The subsequent (2) stimulation of inhibitory GABAergic projection neurons from the NAc to the ventral pallidum (PAL) causes (3) disinhibition of the VTA, which (4) increases the number of spontaneously active DA neurons and hence, (5) tonic levels of DA in the NAc. The increased levels of extrasynaptic DA stimulates postsynaptic D2R on PFC inputs, which (6) selectively attenuates the afferent drive of the PFC. In addition, because only those DA neurons that firing in a tonic manner can transition to a phasic firing mode, the above described phenomenon also primes the responsiveness of the dopaminergic system by allowing more neurons to respond phasically based on the appetitive/aversive properties of the stimulus. Therefore, B. Natural Stimulus-Induced Positive Reinforcement if the novel stimulus is associated with positive reinforcement, (1) burst firing and phasic DA release increases. Increased phasic DA in the NAc (2) activates postsynaptic D1R on HIP terminals, which (3) facilitates HIP inputs to the NAc. In contrast, and relative to naturally reinforcing stimuli, addictive substances more strongly and persistently activate the mesocorticolimbic DA system. Therefore, C. Drug-Induced Positive Reinforcement if the novel stimulus is associated with substance reinforcement (e.g., crack cocaine) (1) burst firing and phasic DA release increases in a more robust and prolonged manner. The supraphysiological levels of elevated synaptic DA levels associated with acute substance use would be expected to increase both tonic and phasic DA levels. Increased intrasynaptic DA levels in the NAc would (2) stimulate postsynaptic D1R on HIP terminals to (3) facilitate inputs from the HIP while increased extrasynaptic DA levels would (4) stimulate postsynaptic D2R on PFC terminals to (5) attenuate inputs from the PFC. The net effect would strongly favor HIP inputs and attenuate PFC inputs.

A novel stimulus associated with reinforcement causes burst firing, increasing the release of phasic DA (Figure 2B). The subsequent increase of intrasynaptic DA levels in the NAc activates postsynaptic D1Rs on HIP terminals, facilitating hippocampal inputs [9,10]. In addition, intrasynaptic DA enhances long-term potentiation (LTP; a short-term enhancement of synaptic efficacy that underlies learning and memory) in the HIP [11]. These intrasynaptic effects of DA appear to preferentially engage the HIP, encoding the reinforcing event as an association among stimulus elements and context [12]. Interestingly, however, stimuli that reliably predict reinforcement enter the network at the PFC, activating glutamatergic projections that synapse on GABA- and DA-containing neurons in the VTA [13], thus providing substrates for both inhibitory and disinhibitory influences on VTA activity [14]. In fact, the activity of DA neurons is not increased by reinforcement that is fully predictable and is depressed by the omission of predicted reinforcement [15], which attenuates activity in the HIP and increases activity in the PFC to facilitate cortical control over the NAc and VTA [16]. This allows the PFC to guide adaptive behavioral responding as stimulus-reinforcement associations change, to avoid preservative responding to negative outcomes and instead seek appropriate new goals [17-20]. Thus, both tonic and phasic DA release appear to alter the synaptic strength of PFC and HIP inputs within a subset of NAc neurons associated with reinforcement-related associative learning [21].

2.2 SUDs and the mesocorticolimbic DA system

The modulatory influence of DA in mesocorticolimbic pathways is crucial for encoding the primary reinforcing effects of psychoactive substances and the subsequent progression of some individuals to develop SUDs. In fact, given that novel and naturally reinforcing stimuli increase DA release to facilitate encoding of stimulus-reinforcement associations and modulate future goal-directed behaviors, it seems reasonable to assume that the novel stimuli associated with initiation of substance-use would activate the mesocorticolimbic network in a similar manner. In contrast, however, the pharmacologic ability of substances to increase DA release more robustly produces more intense sensations of reinforcement, as well as stronger associations between the DA-releasing experience and the environmental stimuli/contexts encountered. That is, in contrast to the fast, transient, and spatially restricted (i.e., normal) physiological response of DA neurons to naturally reinforcing stimuli, illicit substances stimulate DA neurons in a more robust and prolonged manner without temporal or spatial selectivity. The supraphysiological levels of synaptic DA produced by acute substance-use increases both tonic and phasic DA levels, which, in turn, strongly attenuate PFC inputs responsible for impulse control (Figure 2C). In addition, elevated DA levels in PFC would over-stimulate D1 and D2Rs, both of which decreases sensitivity to negative feedback and impairs cognitive functions. Over-stimulation of D1Rs also increases sensitivity to reinforcement while over-stimulation of D2Rs also disrupts the ability of PFC to detect transient changes in DA transmission, leading to perseverative choice selection [21]. However, SUDs do not arise solely from the ability of substances to either acutely increase DA or cause euphoric effects; otherwise, the vast majority of recreational users would progress to become problematic users.

Evidence suggests that chronic substance-induced supra-physiological dopaminergic signaling produces neuroadaptations within mesocorticolimbic circuits that impair the ability to choose naturally reinforcing stimuli over substances. Repeated substance-induced increases of tonic DA in NAc more persistently stimulates D2R that inhibit PFC inputs, while increases of phasic DA release in NAc more persistently stimulate D1R and facilitate HIP inputs. Repetitive stimulation of D1R potently enhances LTP, facilitating HIP inputs to the NAc; in contrast, repetitive stimulation of D2R potently enhances long-term depression (LTD; a short-term reduction of synaptic efficacy), attenuating PFC inputs [7]. This supports the idea that repeated substance-induced DA signaling may cause long-term facilitation of hippocampal inputs and long-term attenuation of PFC inputs and mediated behavioral functions. Consistent with this interpretation, there are long-lasting decreases of postsynaptic D2R in the ventral striatum (NAc) of individuals with SUDs. These pharmacodynamic adaptations may produce a decreased steady-state level of reinforcement system responsivity and explain the reduced value and decreased motivational salience of natural reinforcers, as well as underlie tolerance, negative reinforcement and the overlearning/overvaluing of substance-related cues [22].

Disruptions of dopaminergic signaling in the PFC contribute to myriad complex neurophysiological effects. For example, under-stimulation of D2Rs decreases sensitivity to negative feedback, increases sensitivity to reward/reinforcement, and thus biases choice selection and decision making toward the more reinforcing option despite that fact that there will be negative consequences [21]. That is, decreased activation of PFC D2Rs impairs neuroeconomic processes related to cost/benefit decision-making, perhaps impairing an individual’s ability to shift choices even as the reinforcing effects of psychoactive substances decrease over time. Decreased activation of PFC D1Rs and/or D2Rs impairs cognitive functions and enhances perseverative responding [21]. In fact, although areas of the PFC are typically activated during substance-induced intoxication, they are hypoactive during withdrawal. Hypofrontality compromises PFC-mediated control over the NAc and VTA, decision-making and impulse control [22,23]. In concert, D1R- and D2R-mediated effects in response to psychoactive substances may produce pharmacodynamic adaptations that impair PFC-mediated functions, which prevent selections of appropriate new goals and cause individuals to perseverate on substance-use regardless of negative outcomes.

2.3 Cocaine-use disorder

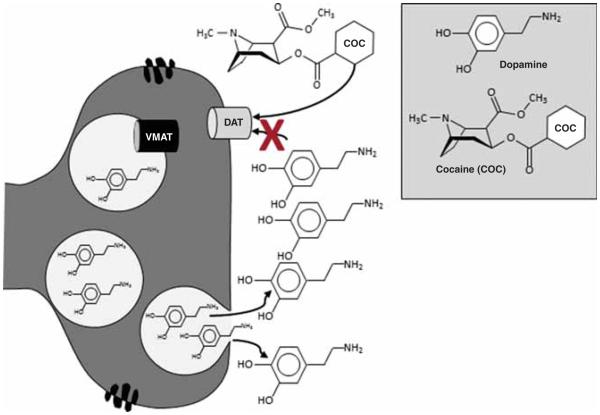

Cocaine has been a subject of scientific interest for more than a century [24]. Cocaine targets the DAT, blocking reuptake and increasing DA levels (Figure 3) [25]. Cocaine also targets the serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) transporter (NET) [25]. However, the subjective and reinforcing effects of cocaine are generally attributed to DA [26].

Figure 3.

Cocaine-Induced Dopamine Release - Cocaine (COC) increases DA levels by affecting DA reuptake from the synaptic cleft, which prolongs the stimulation of DA receptors. Cocaine inhibits the reuptake of DA, and thus acutely increases synaptic DA levels, by binding to DAT located on presynaptic membranes of DA neurons.

Cocaine-use disorder (CUD) is associated with significant neuroadaptations that indicate possible pharmacotherapeutic targets [27]. The neuroadaptations include decreased availability of D2Rs [26,28], lower tonic (baseline) [29] and phasic (evoked) DA release [30,31], decreased availability of vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT)-2, as well as a decrease of DA terminals and/or storage vesicles [32] in striatum. Interestingly, however, DAT levels are twofold to threefold higher in fatal cocaine overdose victims [33]. These abnormalities in striatal DA transmitter dynamics relate to pronounced alterations in cortical networks. For example, hypoactivity in PFC [34,35] is proportional to decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects [28] and CUD is associated with deficits in PFC cognitive functions [36]. These findings suggest that changes in dopaminergic transmission that affect functional connectivity between cortical and subcortical areas in cocaine users may contribute to relapse. Indeed, deficits in DA signaling are associated with poor response to behavioral interventions and relapse [37,38]. Therefore, pharmacotherapies that reverse or normalize dopaminergic signaling could theoretically decrease cocaine-use and relapse.

2.4 METH/AMPH-use disorders

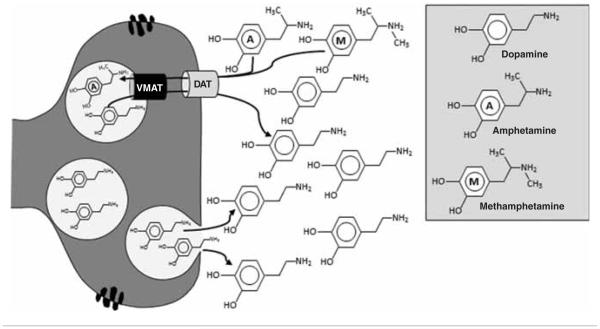

METH/AMPH potently increases central DA (and NE) neurotransmission by acting as a substrate for the DAT and the VMAT, reversing their action and increasing cytosolic and intrasynaptic DA levels independent of tonic or phasic release (Figure 4) [39]. METH also inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO), an enzyme involved in the degradation of DA. AMPH-induced DA release in the ventral striatum correlates with the subjective effects of AMPH, supporting the assumption that mesolimbic system activation and elevated DA levels are essential for the euphoric effects produced by AMPHs [40]. METH/AMPH-use disorders (M/AUD) is associated with decreased D2R, VMAT-2 and DAT availability [41,42], as well as lower phasic DA release [38] in striatum of METH-dependent individuals. Similar to cocaine, PFC hypoactivity in METH-dependent subjects [43,44] is associated with decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness [45]. Moreover, M/AUD is associated with cognitive deficits [46], and decreased DAT and D2Rs are associated with cognitive deficits [47] and impulsivity [48], respectively. METH users with lower phasic (evoked) DA release in the striatum are more likely to relapse during treatment suggesting medications that increase DA tone may prove efficacious as treatments [38].

Figure 4.

METH/AMPH-Induced Dopamine Release - METH and AMPH are substrates for both the DAT and the VMAT. Both METH and AMPH reverse the transport of DA across the DAT and VMAT and thereby increase cytosolic and synaptic DA levels independent of tonic or phasic release. In contrast to cocaine and amphetamines, cannabis indirectly increases DA release.

2.5 Cannabis-use disorder

Although cannabis has been used for thousands of years, the mechanism by which the main psychoactive and reinforcing molecule in cannabis, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), produces its effects was not identified until 1988 [49]. Nonetheless, the central endogenous cannabinoid (endocannabinoid) system includes one primary Gi/o protein-coupled cannabinoid-1 receptor (CB1R), several endogenous agonists (e.g., 2-arachidonoylglycerol), and proteins involved in the formation and deactivation of these ligands [50]. Although dopaminergic neurons have nearly undetectable levels of CB1Rs throughout the mesocorticolimbic system, presynaptic GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals have high and moderate CB1R levels, respectively [51]. As depicted in Figure 5A, under normal physiological conditions, DA neuron activation promotes the synthesis and release of endocannabinoids that act in a retrograde manner to activate CB1Rs on GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals, which reduces the subsequent release of GABA and glutamate to facilitate or inhibit the activity of DA neurons, respectively [51]. Importantly, endocannabinoid synthesis and release is transient and spatially restricted to activated DA neurons. As such, endocannabinoid-induced CB1R activation is also restricted both spatially, to the GABAergic and/or glutamatergic terminals that provide inputs to those same DA neurons, and temporally, to the duration of endocannabinoid synthesis. In contrast, CB1R activation by THC occurs without spatial or temporal selectivity, because THC affects all CB1R-positive terminals in a prolonged manner (Figure 5B). This suggests that modulation of both intrinsic and extrinsic GABAergic, as well as glutamatergic, inputs to the VTA by THC facilitates burst firing of DA neurons and enhances mesolimbic DA release. Indeed, cannabis increases DA release in the NAc of humans [52], which likely mediates its reinforcing effects.

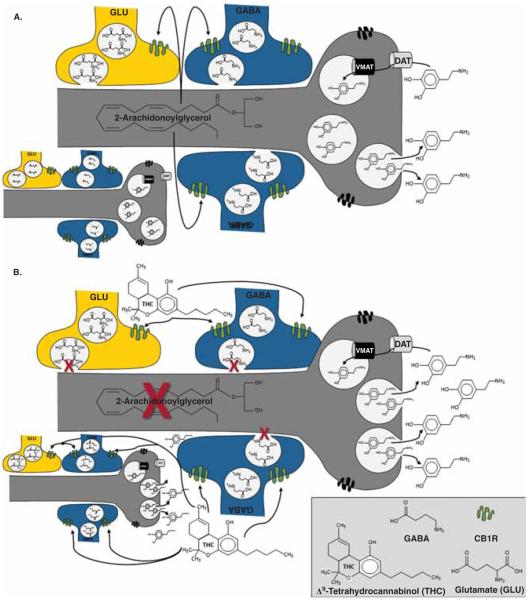

Figure 5.

In contrast to cocaine and amphetamines, cannabis indirectly increases DA release. A. Endocannabinoid Regulation of Dopamine Release Under normal physiological conditions, activation of DA neurons promotes the transient synthesis and release of endocannabinoids (e.g., 2-arachidonoylglycerol) that act in a retrograde and spatially restricted manner to activate CB1Rs in GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals, which reduces the subsequent release of GABA and glutamate to facilitate or inhibit the activity of DA neurons, respectively. For example, activation of CB1Rs by 2-AG in the VTA can suppress depolarization-induced excitation of glutamatergic inputs from the PFC and/or depolarization-induced inhibition (DSI) of GABAergic neurons, which either project from the NAc or are intrinsic VTA interneurons, to modulate bursting activity. B. THC-Induced dopamine release. In contrast to normal physiological activation, THC-induced activation of CB1Rs is neither spatially nor temporally restricted. Rather, THC affects all CB1R-positive terminals in a prolonged manner. CB1Rs are predominately expressed on GABAergic neurons; hence, acute administration of cannabis increases DA neuron activity and augments dopaminergic transmission. In addition to presynaptic co-localization, some NAc neurons also co-express CB1Rs and D2Rs; thus, THC may also modulate DA transmission through intracellular heterodimerization.

Preclinical models indicate THC reduces DA cell firing [53] and compromises DA transmission in the NAc shell [54]. Interestingly, although cannabis-use disorder (CBUD) is associated with hypoactivity of DA neurons in both the VTA [51] and striatum [55], as well as a reduced capacity to synthesize DA in striatum of current users [56], it is not associated with either decreased availability of D2R or changes in DA release in striatum [57,58]. However, given that cannabis indirectly affects DA signaling, CBUD seems more likely to affect CB1R expression. Indeed, a post-mortem investigation of cannabis users revealed presumably compensatory reductions in CB1R availability in the NAc, PFC and HIP [59,60]. Additionally, CBUD is associated with hypoactivity in the PFC and cognitive deficits [61]. Overall, these studies suggest CBUD is associated with altered mesocorticolimbic circuits. As such, medications that target the DA system may decrease relapse.

3. Dopaminergic pharmacotherapies

Individuals who meet criteria for a SUD, but are not seeking treatment, volunteer for Phase-Ib clinical studies. These human laboratory studies investigate safety, tolerability and preliminary efficacy of a putative pharmacotherapy by administering a range of substance doses while maintaining volunteers on specific doses of a candidate medication. The behavioral outcome measures primarily include self-report questionnaires, to characterize subjective euphoric changes, providing predictive utility for Phase-II trials. Some studies also include choice or self-administration procedures [participants make choices between receiving either an alternative reinforcer (e.g., money) or a dose of the substance]. Adding a measure of substance-use substantially strengthens Phase-Ib models by providing important information about the conditions under which these two behaviors (self-reported effects and choices) vary [62]. Phase-Ib trials provide a rapid and efficient indication of an optimal medication dose to maximize efficacy in outpatient treatment seekers enrolled in Phase-II trials, which determine therapeutic efficacy as measured by changes in positive urine screens, typically continuous abstinence for at least 2 weeks at the end of the trial.

Early trials assessed a wide-range of medications that directly stimulate DA receptors based on the theory that mimicking some effects produced by psychoactive substances and partially restoring DA signaling could potentially mitigate withdrawal (dysphoria), decrease craving and prevent relapse [63]. Trials also assessed medications that antagonize DA receptors based on the premise that this could potentially block the acute euphoric and reinforcing effects produced by substances, and thereby decrease use. Modest or negative outcomes, however, across a range of agents do not support their use for SUDs [64-68]. Therefore, the following section focuses on results from studies that assessed DA agonist-like medications that either block reuptake or affect DA levels through other mechanisms, such as increasing precursors (e.g., levodopa-carbidopa) or blocking degradation (e.g., selegiline).

3.1 Cocaine-use disorder

Table 1 lists important details of these studies.

Table 1.

Dopaminergic medications evaluated for CUD in Phase Ib and II studies.

| Medication | Design | Analyzed | Outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Treatment | Groups (mg/d) | Days | Phase | Blind | Type | N = | N per Group | Route (mg) | Retention | 1°(vs. 0mg) | Noteworthy | Refs. |

| Modafinil | 0, 200, 400 | 4 | I | Dbl | XO | 10 | 1*, 6 | IV(30) | - | 200↓SE | - | [74] |

| 0, 400, 800 | 5 | I | Sngl | XO | 16 | 12 | IV (20, 40) | - | ↓SE | 400 = 800 | [75] | |

| 0, 200, 400 | 10 | I | Dbl | XO | 13 | 8 | SM (12, 25, 50) | - | ↓S-A, ↓SE | - | [76] | |

| 0, 400 | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 62 | 32, 30 | - | 65% | ↓USE | - | [73] | |

| 0, 200, 400 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 210 | 71, 68, 68 | - | 60% | ↔USE | 200↓USE | [77] | |

| 0, 200, 400 | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 210 | 75, 65, 70 | - | 57% | ↔USE | 400↓USE | [78] | |

| 0, 400, 200+METH(30) | 112 | II | Dbl | PAR | 73 | 16, 20, 22 | - | 20% | ↔USE | 0↓USE | [79] | |

| Bupropion | 150, 300 | 14-21 | I | Dbl | XO | 10 | 8 | IN (50, 100)‡ | - | ↔SE | - | [81] |

| 0, 100, 200 | 10 | I | Dbl | XO | 8 | 8 | IN (15, 45) | - | ↔S-A, ↑SE | - | [82] | |

| 300 | 56 | II | Open | WI | 6§ | 5 | - | 83% | ↓USE | ↓USE @ 3m FU | [83] | |

| 0, 300 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 150§ | 75, 74 | - | 84% | ↔USE | - | [84] | |

| 0**, 0‡‡, 300**, 300‡‡ | 175 | II | Dbl | PAR | 106§ | 24, 25, 30, 27 | - | 59% | 300** ↔USE | 300‡‡↓USE | [85] | |

| 0, 300 | 112 | II | Dbl | PAR | 70 | 37, 33 | - | 17% | ↔USE | - | [86] | |

| 300(SDE, RDE)+BRM | 56 | II | Open | PAR | 34 | 13, 13 | - | 8% | ↔USE | - | [87] | |

| Methylphenidate | 0, 40, 60 | 5-15 | I | Dbl | XO | 7¶ | 7 | IV (16, 48)‡ | - | 60↓S-A(48), ↓SE | 40↓S-A(16) | [93] |

| 0, 60, 90 | 5 | I | Open | XO | 8 | 7 | IV(20, 40) | - | ↓VAS | - | [94] | |

| 0, 45 | 77 | II | Dbl | PAR | 49 | 24, 25 | - | 45% | ↔USE | - | [95] | |

| 0, 90 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 48¶ | 24, 24 | - | 52% | ↔USE | - | [96] | |

| 60 | 70 | II | Open | WI | 41¶ | 41 | - | 71% | ↑USE | - | [97] | |

| 0, 60 | 98 | II | Dbl | PAR | 124¶ | 53, 53 | - | 44% | ↔USE | 60↓USE (w14) | [98] | |

| METH/AMPH | 0, 40 | 3-5 | I | Dbl | XO | 10 | 9 | IN (10, 20, 30) | - | ↓S-A(20), ↓SE | - | [100] |

| 0, 15, 30 | 3-5 | I | Dbl | XO | 8 | 5 | IN (30, 60) | - | ↔S-A, 30>15↓SE | - | [101] | |

| 0, 30, 60 | 98 | II | Dbl | PAR | 128 | 35, 47, 46 | - | 24% | ↔USE | 60## ↓USE | [102] | |

| 0, 30, 60 | 182 | II | Dbl | PAR | 94§ | 20, 23, 19 | - | 36% | ↔USE | 60##↓USE | [103] | |

| (0, 20-60¶¶ +TPM)**,§§ | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 81 | 42, 39 | - | 79%** | ↔USE | ↑Efficacy w/ ↑SEV## | [104] | |

| 0, 30+MOD(200), 60 | 112 | II | Dbl | PAR | 73 | 16, 22, 15 | - | 20% | ↔USE | 0↓USE | [79] | |

| METH(0,30,30)‡‡ | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 82 | 27, 30, 25 | - | 32% | 30↓USE ## | 30↓USE## | [105] | |

| Selegiline | 0, 10 | 1 | I | Dbl | XO | 5 | 5 | IV(20, 40) | - | ↔SE | ↔VAS | [106] |

| 0, 10 | 4 | I | Sngl | XO | 8 | 8 | IV(40) | - | ↓SE | - | [107] | |

| TSD(6)# | 7 | I | Open | XO | 12# | 12 | IV (0.5, 2)‡ | - | ↔ SE | - | [108] | |

| TSD(0, 6) | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 300 | 148, 147 | - | 69% | ↔USE | - | [109] | |

| Levodopa | 0, 400 | 28 | II | Dbl | PAR | 67 | 36, 31 | - | 33% | ↔USE | - | [110] |

| 0, 400, 800 | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 122 | 40, 43, 39 | - | 43% | ↔USE | - | [110] | |

| 0, 0, 0‡‡, 400, 400, 400‡‡ | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 161 | 21, 20, 20, 20, 20, 20 |

- | 41% | 400‡‡↓USE | - | [111] | |

| 0(**,‡‡,§§), 800<**,‡‡,§§) | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 136 | 101 | - | 35% | 800 ‡‡↓USE |

0** = 800**; 0§§ = 800§§ |

[112] | |

Underlined text = indicates behavioral therapy included; Bold font = indicates sustained release formulation.

Placebo Control;

Dose based on weight (i.e., /kg);

Co-morbid Opioid Use Disorder (MTD maintained);

Co-morbid ADHD;

Experienced Users (i.e., not CUD);

CM for attendance;

CM for negative UDS;

CM for Medication Compliance;

Mixed Amphetamine Salts-Extended Release;

Adjusted for severity of use.

No significant effect;

Significant decrease;

Significant increase;

BRM: Bromocriptine; CM: Contingency Management; Dbl: Double; FU: Follow-up; IN: Intranasal; IV: Intravenous; PAR: Parallel groups; RDE: Rapid dose escalation; S-A: Self-Administration; SDE: Slow dose escalation; SE: Subjective effects; SEV: Severity; SM: Smoked; Sngl: Single; TPM: Topiramate; TSD: Transdermal selegiline delivery; WI: Within; XO: Crossover.

3.1.1 Modafinil

Modafinil treats narcolepsy, sleep disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although modafinil targets the DAT [69], abuse liability in individuals with CUD is low [70]. In fact, modafinil attenuated brain reactivity and craving elicited by cocaine-associated cues [71], as well as improved cognitive functions [72] in cocaine-dependent individuals. A preliminary outpatient clinical trial found that compared to placebo, modafinil (400 mg/day) decreased cocaine-positive urines [73]. Similarly, treatment with modafinil attenuated positive subjective effects produced by intravenous cocaine [74,75] and decreased choices to smoke cocaine [76] in human laboratory studies. Enthusiasm for modafinil was somewhat diminished by more recent and larger trials [77,78]. In fact, even when Anderson and colleagues re-analyzed their data using the primary outcome as Dackis and colleagues [73] (missing urine samples coded cocaine positive) they still found no significant effect [77]. Similarly, when Dackis and colleagues analyzed their most recent data using Anderson’s primary outcome [77] (missing urine samples ignored) they found similar patterns of non-significant effects [78]. A lower level of cocaine dependence severity in the preliminary trial [73] probably underlies the discrepancies with the two subsequent trials [77,78]. It is noteworthy, however, that gender [77] and a history of alcohol dependence [78] influenced the efficacy of modafinil in the latter two studies. Finally, a 16-week trial comparing modafinil and modafinil combined with SR-AMPH, also found modafinil did not decrease cocaine-use, although rates of retention were suboptimal [79]. These studies failed to provide substantial support of using modafinil for CUD. Future studies should exclude participants with alcohol dependence and use contingency management (CM) interventions to improve retention.

3.1.2 Bupropion

Bupropion, available in immediate, sustained and extended release (IR, SR and XL, respectively) formulations, is an anti-depressant and smoking cessation agent. Bupropion weakly binds to the DAT and the NET, blocking reuptake and increasing synaptic levels [80]. In human laboratory studies, IR-bupropion did not significantly decrease subjective effects or choices to self-administer cocaine [81,82]. Moreover, while results from a small (N = 5) open-label trial of IR-bupropion for CUD showed promise in methadone-maintained patients [83], two larger trials, both in methadone-maintained individuals found no beneficial effect of bupropion on cocaine-use [84,85]. It is noteworthy, that bupropion decreased cocaine-use in participants (N = 36) who exhibited depression at baseline [84], and when bupropion was combined with CM for negative urine results [85]. Nonetheless, negative results from two additional trials [86,87], including one that investigated bupropion combined with bromocriptine, suggest bupropion has limited efficacy for CUD.

3.1.3 Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate is primarily used to treat ADHD [88]. Methylphenidate increases DA (and NE [89]) within mesolimbic circuitry by targeting the DAT [90] and recent studies indicate that methylphenidate decreases reactivity to cocaine-associated cues [91,92]. In cocaine-dependent individuals with ADHD, SR-methylphenidate reduced subjective effects and choices to self-administer cocaine [93]. Similarly, IR-methylphenidate reduced subjective effects produced by cocaine in individuals without ADHD [94]. An early clinical trial in individuals without ADHD, however, found that methylphenidate did not reduce cocaine-use [95]. Subsequent outpatient clinical trials in individuals with and without ADHD also do not support the use of methylphenidate for CUD [96-98].

3.1.4 SR formulations of METH/AMPH

SR formulations of METH/AMPH are used to treat ADHD, narcolepsy and obesity and have lower abuse liability than IR formulations [99]. SR-METH and SR-AMPH should probably be classified as noradrenergic medications since they are twofold and threefold more potent, respectively, at inducing NE release compared to DA [25]. Nevertheless, in two Phase-Ib studies, SR-AMPH decreased subjective effects and choices to self-administer cocaine, although outcomes varied by SR-AMPH and cocaine doses [100,101]. In two Phase-II trials, one in methadone-maintained individuals, SR-AMPH alone did not affect cocaine-use overall [102,103]. Similar results were obtained in trials that combined SR-AMPH with either modafinil [79] or the anticonvulsant topiramate (the individual contributions of topiramate and SR-AMPH could not be determined because only the combination was compared to placebo) [104]. However, when severity of cocaine dependence at baseline was considered, cocaine-use significantly decreased in three of these studies [102-104], while in the fourth study, there was a large placebo effect and retention rates were suboptimal [79]. Finally, a clinical trial comparing SR- and IR-METH found that when combined with CM (negative urine results), SR- but not IR-METH decreased cocaine-use [105]. Collectively, these studies support further randomized, controlled trials of SR-METH and SR-AMPH for CUD.

3.1.5 Selegiline

Selegiline irreversibly inhibits MAO-B (at doses that also strongly inhibit MAO-A), increasing central DA levels. A laboratory study found that acute selegiline treatment did not significantly impact subjective effects [106]. In contrast, administration of selegiline for 4 days significantly decreased subjective effects [107]; however, this finding was not replicated when subjects were treated with transdermal selegiline for 7 days [108]. Similarly, a large (N = 300) outpatient clinical trial found transdermal selegiline did not decrease cocaine-use [109]. Overall, results are not particularly convincing for the use of selegiline as a treatment for CUD. However, future studies should evaluate more potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors.

3.1.6 Levodopa–carbidopa

Levodopa, administered with carbidopa to prevent peripheral degradation, is the precursor to DA and used primarily to treat Parkinson’s disease. Mooney and colleagues conducted two outpatient clinical trials assessing levodopa–carbidopa to reduce cocaine-use and found no benefit [110]. A more elaborate clinical trial compared levodopa–carbidopa alone, and in combination with either cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) alone, or CBT and CM (negative urine results). Only levodopa–carbidopa combined with both CBT and CM decreased cocaine-use [111]. Schmitz and colleagues subsequently included CBT in all groups and compared levodopa–carbidopa in combination with CM targeting clinic attendance, medication compliance or negative urine results. Although levodopa–carbidopa did not affect rates of attendance or compliance, it decreased cocaine-use when combined with CM for negative urine results [112]. These outcomes suggest a synergy between levodopa and CM, but only when reducing the reinforcing value, or saliency, of cocaine by targeting abstinence with CM [112]. While these results do not provide overwhelming support for levodopa–carbidopa for CUD, they do reveal the potential value of various behavioral interventions for enhancing outcomes of pharmacotherapeutic trials.

3.2 METH/AMPH-use disorders

Table 2 lists important details of these studies.

Table 2.

Dopaminergic medications evaluated for M/AUD in Phase Ib and II studies.

| Medication | Design | Analyzed | Outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Treatment | Groups (mg/d) |

Days | Phase | Blind | Type | N = | N per group |

Route (mg) |

Retention | 1° (vs. 0 mg) | Noteworthy | Refs. |

| Modafinil | 0, 200 | 3 | I | Dbl | XO | 13 | 13/13 | IV (0, 30) | – | ↔S-A or SE | – | [113] |

| 200 | 84 | Sngl | Wl | 13 | 10 | – | 77% | ↓USE | – | [114] | ||

| 400*,§ | 42 | II | Open | XO | 8 | 8 | – | 50% | ↔USE | – | [115] | |

| 0, 200 | 70 | II | Dbl | PAR | 80 | 38/42 | – | 33% | ↔USE | – | [116] | |

| 0, 200, 400 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 210 | 68/72/70 | – | 53% | ↔USE | – | [117] | |

| Bupropion | 0, 300 | 9-13 | I | Dbl | PAR | 26 | 10/10 | IV (0, 15, 30) | – | ↓VAS | – | [119] |

| 0, 300 ‡ | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 73 | 37/36 | – | 35% | ↔USE | ↓USE¶ | [120] | |

| 0, 300 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 156 | 72/79 | – | 52% | ↔USE | ↓USE¶ | [121] | |

| Methylphenidate | 0, 54 | 154 | II | Dbl | PAR | 79 | 39/39 | – | 35% | ↔USE | – | [124] |

| AMPH | A(0, 60) | 84 | II | Open | PAR | 41 | 20/21 | – | 76% | ↔USE | – | [125] |

| 0, ≤110 | 84 | II | Dbl | PAR | 49 | 23/26 | – | 47% | ↔USE | – | [126] | |

| 0, 60 | 56 | II | Dbl | PAR | 60 | 30/30 | – | 92% | ↔USE | – | [127] | |

Underlined text = indicates behavioral therapy included; Bold font = indicates sustained release formulation;

no significant effect;

significant decrease;

↑ significant increase.

CM for attendance;

CM for negative UDS;

CM for Medication Compliance;

Adjusted for severity of use.

CM: Contingency Management; Dbl: Double; IV: Intravenous; PAR: Parallel groups; S-A: Self-Administration; Sngl: Single; SE: Subjective effects; WI: Within; XO: Crossover.

3.2.1 Modafinil

A laboratory study found that modafinil non-significantly decreased (~25%) subjective effects and choices to self-administer METH [113]. An outpatient trial found that modafinil combined with CBT decreased METH-use from 4 days/week to 2 days/week, although the small sample size (N = 13) and number of completers (N = 10) precluded proper statistical analysis [114]. In contrast, a small (N = 8) open-label study that included CBT and CM (attendance) found that while modafinil reduced anxiety and depression, it did not reduce use [115]. A 10-week trial of modafinil also found no differences in METH-use, and despite poor retention (33%), those who received counseling outside the trial had better outcomes at follow-up [116]. Finally, a well powered (N = 210) multi-site study revealed no overall benefit of modafinil [117]. Interestingly, however, the number of consecutive non-use days, as well as retention, was significantly higher in modafinil compliant participants (> 85% compliance, N = 36) compared to the rest of the modafinil treatment groups (23 vs. 10 days, p = 0.003) [117]. Future studies evaluating modafinil (but also other compounds) need to improve rates of retention and medication compliance in order to provide answers that are more definitive.

3.2.2. Bupropion

Newton and colleagues found that SR-bupropion significantly reduced the cardiovascular and subjective effects of METH in two laboratory studies [118,119]. Subsequently, Shoptaw and colleagues found that bupropion combined with CBT and CM (negative urine results) did not reduce use, although subgroup analyses revealed that SR-bupropion significantly reduced use in light, but not heavy, users [120]. Similarly, Elkashef and colleagues also found no effect of SR-bupropion overall but it did reduce METH-use in light, male users [121]. Both studies defined light-use as ≤ 17 days/month. Overall, evidence suggests SR-bupropion may be useful for treating light users.

3.2.3 Methylphenidate

Published case studies (N = 4) and one incomplete placebo-controlled clinical trial (N = 17) suggested that treatment with methylphenidate may reduce AMPH-use [122,123]. However, results from the only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of SR-methylphenidate were not positive, although retention was poor (35%) [124]. Clearly, additional studies are needed.

3.2.4 SR formulations of METH/AMPH

An initial Australian study in AMPH-dependent individuals found that treatment with AMPH significantly increased attendance of optional counseling sessions, but did not significantly reduce use [125]. In a subsequent Australian cohort of METH-dependent individuals, Longo and colleagues found that despite significantly greater retention in the SR-AMPH group, there were no differences on METH-use [126]. A similar trial assessing the impact of SR-AMPH combined with motivational enhancement therapy found no differences between groups on METH-use, although SR-AMPH treatment reduced withdrawal symptoms and craving [127]. These studies do not provide overwhelming support for SR-AMPH for METH-use disorder, but the small sample sizes, poor retention and insufficient statistical power of these studies suggest the need for additional studies before definitive conclusions can be made.

3.3 Cannabis-use disorder

Table 3 lists important details of these studies.

Table 3.

Dopaminergic medications evaluated for CBUD in Phase Ib and II studies.

| Medication | Design | Analyzed | Outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Treatment | Groups (mg/day) |

Days | Phase | Blind | Type | N = | N per Group |

Route (mg) |

Retention | 1° (vs. 0mg) | Noteworthy | Refs. |

| Modafinil | 0, 400 | 1 | I | Dbl | XO | 12 | 12/12 | PO (15) | – | ↓SE | – | [128] |

| Bupropion | 0, 300 | 28 | I | Dbl | XO | 10 | 9/9 | SM (2.8%) | – | ↔SE, ↑WD | – | [129] |

| 0, 300 | 70 | II | Dbl | PAR | 70 | 30/40 | – | 46% | ↔USE or WD | – | [130] | |

Underlined text = indicates behavioral therapy included; Bold font = indicates sustained release formulation;

no significant effect;

significant decrease;

significant increase.

CM: Contingency Management; Dbl: Double; PAR: Parallel groups; PO: Per os; SM: Smoked; SE: Subjective effects; WD: Withdrawal; XO: Crossover.

3.3.1 Modafinil

A Phase-Ib study found that modafinil acutely attenuated ratings of THC-induced euphoria [128]. These findings support the safety of modafinil in combination with THC, but additional confirmatory studies are required, including an outpatient clinical trial.

3.3.2 Bupropion

In a human laboratory study, SR-bupropion worsened, rather than improved some withdrawal symptoms and did not reduce subjective effects [129]. A subsequent Phase-II trial evaluated the efficacy of SR-bupropion on abstinence and withdrawal symptom severity [130]. Results revealed no significant effect of treatment on cannabis-use or withdrawal symptoms. Overall, available data indicate SR-bupropion may have limited efficacy as a treatment for CBUD.

3.3.3 Methylphenidate

In a human laboratory, within-subjects study of cannabis users (N = 8), acute administration of methylphenidate (10, 20 and 30 mg) improved performance on cognitive tasks and did not produce reinforcing effects [131]. This preliminary study suggests that methylphenidate may have some efficacy as a treatment for CBUD.

4. Conclusion

Several apparent discrepancies within Phase-Ib, as well as between Phase-Ib and Phase-II, studies deserve mention. Within Phase-Ib studies, some treatments reduce subjective effects but do not reduce number of choices to receive cocaine (e.g., [101]). Findings between Phase-Ib and Phase-II studies may appear inconsistent because a treatment can reduce both subjective effects and self-administration in the laboratory but not decrease substance-use in outpatient clinical trials (e.g., modafinil for CUD). Several factors likely underlie these apparent paradoxical findings; for example, patients seeking treatment in outpatient clinical trials may have psychiatric co-morbidities and other dependencies that would typically exclude non-treatment seeking research volunteers from participating in Phase-Ib studies. For a comprehensive review of these and other factors, see [132]. Regardless of human laboratory study caveats, Phase-Ib trials provide a rapid and efficient indication of an optimal medication dose to minimize safety/abuse risk and maximize efficacy for use in more rigorous, but more expensive and time-consuming, Phase-II trials.

Studies have shown that chronic substance-use associates with altered dopaminergic circuitry suggesting that pharmaco-therapies targeting this system may prove beneficial. Research assessing pharmacotherapies that directly or indirectly target DA neurotransmission have not, however, yielded a single FDA-approved medication. Nevertheless, results from clinical trials noted in this review do have important implications for the success of future studies. For example, there is a clear need to enhance retention and medication compliance for rigorous efficacy evaluation. Incentive-based strategies, such as CM [133], improve retention and compliance, and even produce modest abstinence rates per se. Reducing dosing requirements, via use of SR formulations, should also increase compliance. Similarly, standardizing analytical methods and the handling of missing urine screens would surely increase the validity of comparing outcomes across studies. Carefully screening and excluding participants, or randomizing participants based on SUD severity [120,121], outside contingencies known to affect outcomes (e.g., sanctions associated with methadone programs [84]), and co-morbidities seems logical. Finally, treatment readiness, or motivation to stop using, may be a particularly important patient characteristic for future trials to assess, to either specifically target motivated patients, or include motivation as a potential predictor variable [84].

Finally, it is clear that efforts to identify medications specifically for CBUD lag far behind treatment development efforts of other illicit substances. This is disconcerting because despite many years of prevention efforts targeting adolescents, adolescent cannabis-use is at its highest level in 30 years, and the average age at which adolescents start using cannabis is falling while the proportion of adolescents who believe regular cannabis-use is harmless is rising [2,134]. These trends are troublesome because epidemiological studies have reported a significant association between adolescent cannabis-use and an increased risk of developing CBUD; ~ 3% of individuals who initiate cannabis-use between 22- and 26-years old eventually satisfy criteria for dependence versus ~ 15% of individuals who initiate cannabis-use between 13- and 17-years old [135]. Although systematic research on treatments for cannabis-related disorders began only 20-years ago, a major obstacle slowing the development of treatments for CBUD is the continued belief, even among the scientific community, that cannabis is benign and incapable of inducing a true-use disorder. While it is true that unlike CUDs, which can develop expeditiously after first use, CBUDs develop more insidiously and gradually [136], treatment admissions for CBUD in the USA have increased twofold during the past decade [137], and cannabis was the most reported reason for receiving treatment related to illicit substance-use problems in 2011 [2]. In fact, cannabis relapse rates are comparable to those found for other illicit substances [138,139]. These data highlight the increasing demand for treatment as well as the high rates of relapse associated with current treatment options for CBUDs and thus emphasize a clear need for more research in this area.

5. Expert opinion

The impact of the purported dopaminergic changes in the mesocorticolimbic system are rarely considered in the context of effects on other neurotransmitter systems, or conversely the influence of other neurotransmitter systems on the functionality of dopaminergic and mesocorticolimbic systems, that are also considered critical to the normal functioning of this network and hence the pathophysiology of SUDs. Medications that are relatively selective for the dopaminergic system face two major barriers to efficacy. Direct and indirect agonists of D2R may increase impulsivity in vulnerable individuals or produce reinforcing effects. Similarly, D2R antagonists (e.g., atypical neuroleptics) tend to produce unwanted motor side effects and the relatively low doses used clinically [140] are ineffective [141]. Overall, among the many and varied dopaminergic agents reviewed here and elsewhere, agonist-like medications have produced the most promising results relative to direct DA agonists and antagonists, and the development of agonist replacement pharmacotherapies for opioid and nicotine dependence suggests that these promising findings warrant further testing.

Preclinical studies continue to elucidate the neural circuits involved in reinforcement and cognitive functions, the neuropharmacological mechanisms by which psychoactive substances produce adaptations within these circuits, as well as potential therapeutic targets. Accumulated knowledge from preclinical and clinical studies continues to expand the foundation for evaluating new medications in a more efficient manner. While the ultimate endpoint is abstinence, it is unlikely that a single medication will achieve this goal. Indeed, because not everyone responds to a particular medication or to a behavioral intervention, there is a pressing need for studies to separate the genetic, co-morbid and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic factors that affect the way an individual responds to various interventions. Ideally, being able to predict treatment response based on underlying biological tone would allow either more adequate randomization of participants or focusing on a more homogeneous population [142].

Although DA is necessary for the expression of reinforcing effects produced by psychoactive substances, it is increasingly recognized that it is not sufficient to produce the vast array of neurobiological changes that underlie the development of SUDs. Other neurotransmitters acting in the mesocorticolimbic facilitate the behavioral effects produced by psychoactive substances, raising the possibility that interfering with these overlapping systems could reduce use. Of the medications discussed, SR-AMPH formulations appear the most promising in this regard, but abuse-liability may limit clinical utility. On the other hand, animals lacking α1 NE receptors in cortex or striatum show reduced sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of opiates and stimulants [143-145]. Further, treatment with NE a1 receptor antagonists attenuated cocaine reinstatement [140,146], reduced subjective effects produced by cocaine [147], and reduced cocaine-use in a preliminary study [148]. Similarly, serotonin attenuates cocaine-induced increases of DA in monkeys [149], which suggests that medications that increase DA, NE and serotonin (i.e., triple reuptake inhibitors) may prove efficacious. Indeed, accumulating evidence supports benefit from single medications or combinations of medications that broadly enhance monoamine transmission, and this promising strategy may have advantages. For example, pharmacotherapies that increase monoamines are more likely to mimic the neurochemical effects, as well as some subjective and behavioral effects, of many abused substances.

Because no single medication helps all patients, but rather, some subgroups respond to specific medications, combination therapies are particularly intriguing. In fact, it is also worth noting that the use of more than one medication to combat a serious disease is the mainstay for the treatment of HIV, several types of cancer, as well as other psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). Additionally, combining medications with CM in individuals with a SUD, which theoretically decreases the salience of natural rewards, may improve both retention and medication compliance, and thereby allow medications time to normalize signaling and ultimately increase the saliency of rewards offered as part of a behavioral treatment. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with a SUD have deficient monoaminergic tone and that competing rewards are less salient (e.g. [112]). This strategy follows the recommended multipronged treatment approach of using behavioral and pharmacological strategies to shift reward preference away from psychoactive substances and toward non-substance rewards [150].

Article highlights.

SUD is a complex disease that affects neural circuits involved in reinforcement, motivation, learning and memory, and inhibitory control.

DA mediates, in part, the reinforcing effects of psychoactive substances and has a modulatory role in cognitive processes.

A review of recent clinical studies that investigated agonist-like dopaminergic medications for cocaineuse disorder, METH/AMPH-use disorder, and more recently cannabis-use disorder provides some insight to inform the design of future pharmacotherapy trials.

Current efforts increasingly focus on a strategy fostering combination pharmacotherapies that target multiple neurotransmitter systems.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2011 National Survey on drug use and health: summary of national findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2012. NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Substance abuse and mental health services administration, center for behavioral health statistics and quality. treatment episode data set (TEDS): 2000-2010. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services; Rockville, MD: 2012. DASIS Series S-61, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4701. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2010 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits; Rockville, MD: (July 2, 2012) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller T, Hendrie D. Substance abuse prevention dollars and cents: a cost-benefit analysis. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2008. DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 07-4298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9752):1558–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ. Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• A comprehensive review of the dopaminergic mesocorticolimbic system.

- 8.Lisman JE, Grace AA. The hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron. 2005;46:703–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto Y, Grace AA. Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:805–12. doi: 10.1038/nn1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West AR, Grace AA. Opposite influences of endogenous dopamine D1 and D2 receptor activation on activity states and electrophysiological properties of striatal neurons: studies combining in vivo intracellular recordings and reverse microdialysis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:294–304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00294.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shohamy D, Adcock RA. Dopamine and adaptive memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14(10):464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron. 2004;44:109–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballard IC, Murty VP, Carter RM, et al. Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Drives Mesolimbic Dopaminergic Regions to Initiate Motivated Behavior. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10340–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0895-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz W. Multiple reward signals in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:199–207. doi: 10.1038/35044563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goto Y, Otani S, Grace AA. The Yin and Yang of dopamine release: a new perspective. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:583–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kringelbach ML. The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:691–702. doi: 10.1038/nrn1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stern CE, Owen AM, Tracey I, et al. Activity in ventrolateral and mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during nonspatial visual working memory processing: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2000;11:392–9. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrides M. Dissociable roles of mid-dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior inferotemporal cortex in visual working memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7496–503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07496.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen JD, Braver TS, Brown JW. Computational perspectives on dopamine function in prefrontal cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:223–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floresco SB. Prefrontal dopamine and behavioral flexibility: shifting from an “inverted-U” toward a family of functions. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:62. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• A timely update concerning the role of preforntal cortical dopamine in cognitive functions.

- 22.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groman SM, Jentsch JD. Cognitive control and the dopamine D-like receptor: a dimensional understanding of addiction. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:295–306. doi: 10.1002/da.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilcher JE., II Cocaine as an Anaesthetic; its status at the close of the first year of its use. Ann Surg. 1886;3:51–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, et al. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Goldstein RZ. Role of dopamine, the frontal cortex and memory circuits in drug addiction: insight from imaging studies. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:610–24. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haile CN, Mahoney JJ, III, Newton TF, De La Garza R., II Pharmacotherapeutics directed at deficiencies associated with cocaine dependence: focus on dopamine, norepinephrine and glutamate. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134:260–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:318–25. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez D, Greene K, Broft A, et al. Lower level of endogenous dopamine in patients with cocaine dependence: findings from PET imaging of D/D receptors following acute dopamine depletion. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1170–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature. 1997;386:830–3. doi: 10.1038/386830a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez D, Narendran R, Foltin RW, et al. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release: markedly blunted in cocaine dependence and predictive of the choice to self-administer cocaine. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:622–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narendran R, Lopresti BJ, Martinez D, et al. In vivo evidence for low striatal vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) availability in cocaine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:55–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staley JK, Hearn WL, Ruttenber AJ, et al. High affinity cocaine recognition sites on the dopamine transporter are elevated in fatal cocaine overdose victims. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1678–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolla K, Ernst M, Kiehl K, et al. Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in abstinent cocaine abusers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:456–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16.4.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.London ED, Cascella NG, Wong DF, et al. Cocaine-induced reduction of glucose utilization in human brain. A study using positron emission tomography and [fluorine 18]-fluorodeoxyglucose. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:567–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180067010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Serrano MJ, Perales JC, Moreno-Lopez L, et al. Neuropsychological profiling of impulsivity and compulsivity in cocaine dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:673–83. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez D, Carpenter KM, Liu F, et al. Imaging dopamine transmission in cocaine dependence: link between neurochemistry and response to treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:634–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GJ, Smith L, Volkow ND, et al. Decreased dopamine activity predicts relapse in methamphetamine abusers. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:918–25. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sulzer D. How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission. Neuron. 2011;69:628–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC, et al. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang L, Alicata D, Ernst T, Volkow N. Structural and metabolic brain changes in the striatum associated with methamphetamine abuse. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):16–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, et al. Loss of dopamine transporters in methamphetamine abusers recovers with protracted abstinence. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9414–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09414.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, et al. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:73–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nestor LJ, Ghahremani DG, Monterosso J, London ED. Prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive control in early abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194:287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, et al. Low level of brain dopamine D2 receptors in methamphetamine abusers: association with metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2015–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR. A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine. Addiction. 2009;104:1085–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• An excellent review.

- 47.McCann UD, Kuwabara H, Kumar A, et al. Persistent cognitive and dopamine transporter deficits in abstinent methamphetamine users. Synapse. 2008;62:91–100. doi: 10.1002/syn.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee B, London ED, Poldrack RA, et al. Striatal dopamine d2/d3 receptor availability is reduced in methamphetamine dependence and is linked to impulsivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14734–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3765-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devane WA, Dysarz FA, Johnson MR, et al. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;34:605–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solinas M, Goldberg SR, Piomelli D. The endocannabinoid system in brain reward processes. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:369–83. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• An excellent review of the endocannabinoid system.

- 51.Fitzgerald ML, Shobin E, Pickel VM. Cannabinoid modulation of the dopaminergic circuitry: implications for limbic and striatal output. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bossong MG, van Berckel BN, Boellaard R, et al. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol induces dopamine release in the human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:759–66. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diana M, Melis M, Muntoni AL, et al. Mesolimbic dopaminergic decline after cannabinoid withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(17):10269–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanda G, Loddo P, Di Chiara dG. Dependence of mesolimbic dopamine transmission on delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;376:23–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sevy S, Smith GS, Ma Y, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism and D2/D3 receptor availability in young adults with cannabis dependence measured with positron emission tomography. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:549–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bloomfield MA, Morgan CJ, Egerton A, et al. Dopaminergic function in cannabis users and its relationship to cannabis-induced psychotic symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;pii doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.027. S0006-3223(13)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albrecht DS, Skosnik PD, Vollmer JM, et al. Striatal D/D receptor availability is inversely correlated with cannabis consumption in chronic marijuana users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urban NB, Slifstein M, Thompson JL, et al. Dopamine release in chronic cannabis users: a [11c]raclopride positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:677–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villares J. Chronic use of marijuana decreases cannabinoid receptor binding and mRNA expression in the human brain. Neuroscience. 2007;145:323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirvonen J, Goodwin RS, Li CT, et al. Reversible and regionally selective downregulation of brain cannabinoid CB1 receptors in chronic daily cannabis smokers. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:642–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lorenzetti V, Lubman DI, Whittle S, et al. Structural MRI findings in long-term cannabis users: what do we know? Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1787–808. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Utility of subjective-effects measurements in assessing abuse liability of drugs in humans. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1563–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kosten TR, George TP, Kosten TA. The potential of dopamine agonists in drug addiction. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:491–9. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J. Agonist-like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:76–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, et al. Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1439–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alvarez Y, Perez-Mana C, Torrens M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs in cocaine dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;45:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • A thorough review.

- 67.Ohuoha DC, Maxwell JA, Thomson LE, III, et al. Effect of dopamine receptor antagonists on cocaine subjective effects: a naturalistic case study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14:249–58. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amato L, Minozzi S, Pani PP, et al. Dopamine agonists for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003352. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003352.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, et al. Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications. JAMA. 2009;301:1148–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vosburg SK, Hart CL, Haney M, et al. Modafinil does not serve as a reinforcer in cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:233–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goudriaan AE, Veltman DJ, van den Brink W, et al. Neurophysiological effects of modafinil on cue-exposure in cocaine dependence: a randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study using pharmacological fMRI. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kalechstein AD, Mahoney JJ, III, Yoon JH, et al. Modafinil, but not escitalopram, improves working memory and sustained attention in long-term, high-dose cocaine users. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:472–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:205–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dackis CA, Lynch KG, Yu E, et al. Modafinil and cocaine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled drug interaction study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malcolm R, Swayngim K, Donovan JL, et al. Modafinil and cocaine interactions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:577–87. doi: 10.1080/00952990600920425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, et al. Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:761–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43:303–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schmitz JM, Rathnayaka N, Green CE, et al. Combination of Modafinil and d-amphetamine for the Treatment of Cocaine Dependence: a Preliminary Investigation. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:77. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dwoskin LP, Rauhut AS, King-Pospisil KA, et al. Review of the pharmacology and clinical profile of bupropion, an antidepressant and tobacco use cessation agent. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:178–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oliveto A, McCance-Katz FE, Singha A, et al. Effects of cocaine prior to and during bupropion maintenance in cocaine-abusing volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:155–67. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE, et al. Influence of acute bupropion pre-treatment on the effects of intranasal cocaine. Addiction. 2012;107:1140–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]