Abstract

Background/Objective

Obesity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetic complications in type 1 diabetes. Adipokines, which regulate obesity-induced inflammation, may contribute to this association. We compared serum adipokines and inflammatory cytokines in obese and lean children with new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes.

Subjects and Methods

We prospectively studied 32 lean and 18 obese children (age range: 2–18 yr) with new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes and followed them for up to 2 yr. Serum adipokines [leptin, total and high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin, omentin, resistin, chemerin, visfatin], cytokines [interferon (IFN)-gamma, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-12, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha] and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured at a median of 7 wk after diagnosis (range: 3–16 wk).

Results

Lean children were 71.9% non-Hispanic White, 21.9% Hispanic, and 6.3% African-American, compared with 27.8, 55.6, and 16.7%, respectively, for obese children (p = 0.01). Compared with lean children, obese children had significantly higher serum leptin, visfatin, chemerin, TNF-alpha and CRP, and lower total adiponectin and omentin after adjustment for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage. African-American race was independently associated with higher leptin among youth ≥10 yr (p = 0.007). Leptin levels at onset positively correlated with hemoglobin A1c after 1–2 yr (p = 0.0001) independently of body mass index, race/ethnicity, and diabetes duration. Higher TNF-alpha was associated with obesity and female gender, after adjustment for race/ethnicity (p = 0.0003).

Conclusion

Obese children with new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes have a proinflammatory profile of circulating adipokines and cytokines that may contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease and diabetic complications.

Keywords: adipokine, adiponectin, chemerin, children, cytokines, IFN-gamma, IL-10, IL-12, IL-6, IL-8, leptin, obesity, omentin, resistin, TNF-alpha, type 1 diabetes, visfatin

The incidence of childhood obesity is rising worldwide (1, 2). The prevalence of obesity and overweight is 32% in children from the general population (1), 35% in children with established type 1 diabetes (3), and 25% at the onset of pediatric type 1 diabetes, despite the weight loss that often precedes diagnosis (4, 5). Obesity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and microvascular diabetic complications in adults and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (6–9). Obesity represents a state of chronic inflammation (10, 11), and obesity-induced inflammation has been associated with the development of components of the metabolic syndrome and of type 2 diabetes (12). A potential link between obesity and inflammation are adipokines, substances secreted by adipose tissue, such as adiponectin (13), leptin (14), omentin (15), resistin (16, 17), chemerin (18), and visfatin (19). Both proinflammatory adipokines, e.g., leptin and resistin, and anti-inflammatory adipokines, e.g., adiponectin and omentin, play critical roles in the regulation of inflammation (11). Children with type 1 diabetes are known to have an abnormal adipokine profile (20–23). However, the relationship between obesity and markers of adiposity and inflammation at the onset of autoimmune type 1 diabetes in children, especially under the age of 10 yr, has not been well characterized. Our aim was to compare circulating levels of a novel panel of adipokines and inflammatory cytokines associated with obesity in obese and lean children at the onset of autoimmune type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Subjects

We prospectively evaluated 32 lean and 18 obese children with new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes between October 2010 and October 2011. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital. Insulin autoantibodies levels were measured within 10 d of diagnosis to avoid potential false positive results caused by exposure to exogenous insulin. Other islet autoantibodies, i.e., glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65), islet cell autoantigen 512 (ICA512/IA2), and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) autoantibodies, as well as fasting C-peptide and biomarkers of adiposity, were measured at median 6.9 wk [interquartile range (IQR) = 4.3–9.0], at least 3 wk after diagnosis to ensure metabolic stabilization. Children were followed prospectively for a median of 1.3 yr (range 0–2).

Data collection

Demographic information included dates of birth and diagnosis, gender, and race/ethnicity. Biochemical data included serum hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), glucose, pH, bicarbonate, and beta-hydroxybutyrate at diagnosis. Additionally, we collected HbA1c at median 9 wk (IQR = 7.7–10.1) and the latest available HbA1c in children followed for ≥1 yr since diagnosis (median = 1.6, IQR = 1.3–1.7). Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) was defined by venous blood pH <7.30 and bicarbonate <15 mEq/L. Anthropometric information included weight and height at the 9-wk visit, thus avoiding the effect of dehydration on weight, as well as Tanner pubertal staging performed by a pediatric endocrinologist. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated in children based on height and weight and was categorized using gender and age-specific percentiles by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria (24). Because of the lack of standardized age- and gender-adjusted BMI data for ages 0–2 yr, only children 2 yr or older were included.

Laboratory methods

GAD65, ICA512/IA-2, and ZnT8 islet autoantibodies were measured by radioligand binding assay (RBA) as previously described (25). Briefly, recombinant [35]S-GAD65 was produced in an in vitro coupled transcription and translation system with SP6 RNA polymerase and nuclease treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Madison, WI). Sera (2.5 μL) were incubated with [35]S-GAD65 [25 000 of trichloroacetic acid-precipitable radioactivity (TCA) precipitable radioactivity]. After an overnight incubation at 4°C, antibody-bound [35]S-GAD65 was separated from unbound antigen by precipitation with PAS. The immunoprecipitated radioactivity was counted on a Wallac Microbeta Liquid Scintillation Counter (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Inc, Boston, MA). Autoantibodies to ICA512/IA-2 were measured under identical conditions as described for GAD65 autoantibodies. The plasmid containing the cDNA for the cytoplasmic portion of ICA 512 was kindly donated by Dr G. Eisenbarth, Barbara Davis Center, Denver, CO. Samples were considered ICA512/IA2-autoantibody-positive if binding exceeded that of the 98th percentile for healthy controls [30 relative units [RU]/mL]. ZnT8 autoantibodies were measured under similar conditions as described for GAD65 autoantibodies. The cytosolic segments (aa268–369) encoded the aa325 codon variants CGG (Arg), and TGG (Trp). A pan-reactive positive control serum from a type 1 diabetes patient was included as a standard and used to express immunoglobulin binding levels as an RU. Cutoff was set at 15 RU/mL for autoantibodies to ZnT8Arg and 26 RU/mL for ZnT8Trp based on the 98th percentile observed in 50 healthy human control sera. Samples were considered ZnT8 autoantibody-positive if binding to either ZnT8Arg or ZnT8Trp was detected. Our laboratory participated in the Diabetes Autoantibody Standardization Program (DASP) (26) workshop and the GAD65 autoantibody assay showed a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 93%, and the ICA512/IA-2 autoantibody assay showed a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 98%. ZnT8 autoantibodies were not included in the workshop. Insulin autoantibodies were measured by Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute (San Juan Capistrano, CA) by radioimmunoassay with clinical sensitivity and specificity of 50 and 99%, respectively (positivity >0.4 U/mL).

Leptin, adiponectin [total and high molecular weight (HMW)], omentin, chemerin, visfatin, resistin, tumor necrosis (TNF)-alpha, interferon (IFN)-gamma, inter-leukin (IL)-10, IL-12, IL-6, and IL-8 were measured by quantitative sandwich ELISA (Biosource, Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA, USA), with coefficients of variation <12%. Serum C-peptide was measured by highly specific RIA (Human C-Peptide RIA kit, Millipore Research Inc., St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 10 (StataCorp. 2007. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Sample size estimation was not performed a priori for this pilot study, but rather all available cases were used. We used Student’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests to compare the levels of adipokines in obese and lean children. Multivariable analysis was used to compare the two groups with adjustment for potential confounders, i.e., race/ethnicity and Tanner stage. Because a previous report on serum leptin in pediatric type 1 diabetes was limited to youth ≥10 yr of age (21), we evaluated the associations of this adipokine in children ≥10 yr and <10 yr. We observed an interaction (p = 0.008 for the interaction term), with the relationship between race and leptin being different in children ≥10 yr and <10 yr old, after adjustment for obesity, and therefore results were presented separately for each age group. To build a predictive model of HbA1c at the last follow-up, we first constructed an initial model with each of the covariates one at a time, and factors with p-values <0.1 were entered into a multivariable model. The p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the lean and obese children with autoimmune type 1 diabetes are illustrated in Table 1. Lean and obese children had mean [±standard deviation (SD)] BMI percentiles of 58th (±20.0) and 98.1th (±1.4), respectively (p < 0.0001). Racial/ethnic distribution was statistically different between the two groups, with higher proportion of Hispanics and African-Americans among obese children. Tanner stage of pubertal development tended to be different between lean and obese children, with higher proportion of lean children at Tanner stage I (p = 0.06). There were no significant differences between lean and obese participants with regards to gender, age, incidence of DKA, glucose, number of positive islet autoantibodies or HbA1c at diagnosis, or HbA1c at 9 wk.

Table 1.

Characteristics of lean and obese children with autoimmune type 1 diabetes

| Lean, N = 32 | Obese, N = 18 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: number (%) male | 15 (46.9) | 12 (66.7) | 0.18 |

| Age (yr) | 10.2 (4.6) | 11.2 (3.2) | 0.42 |

| Pubertal Tanner stage: number (%) | 0.06 | ||

| I | 18 (58.1) | 4 (23.5) | |

| II | 3 (9.7) | 7 (41.2) | |

| III | 3 (9.7) | 1 (5.9) | |

| IV | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| V | 5 (16.1) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity: number (%) | 0.01 | ||

| NHW | 23 (71.9) | 5 (27.8) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (21.9) | 10 (55.6) | |

| African-American | 2 (6.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| DKA at diagnosis: number (%) | 10 (35.7) | 8 (47.1) | 0.45 |

| Glucose at diagnosis (mmol/L) | 20.5 (8.8) | 18.8 (9.1) | 0.51 |

| HbA1c at diagnosis (%) [mmol/mol] | 11.9 (2.1) [107 (23.0)] | 12.4 (1.9) [112 (20.8)] | 0.47 |

| HbA1c 9 wk after diagnosis (%) [mmol/mol] | 7.6 (1.1) [60 (12.0)] | 7.5 (1.7) [58 (18.6)] | 0.77 |

| Last available HbA1c (%)* | 8.2 (2.0) [66 (21.9)] | 9.5 (2.6) [80 (28.4)] | 0.086 |

| Number of positive autoantibodies: number (%) | 0.44 | ||

| 1 | 9 (29.0) | 3 (17.7) | |

| 2 | 11 (35.5) | 6 (35.3) | |

| 3 | 9 (29.0) | 8 (47.1) | |

| 4 | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Fasting serum C-peptide (ng/mL) | 0.77 (0.54) | 2.73 (2.40) | 0.0001 |

| BMI percentile 9 wk after diagnosis (%) | 58.0 (20.0) | 98.1 (1.4) | 0.0001 |

| BMI percentile at the last visit* | 58.7 (24.6) | 97.0 (2.6) | 0.0001 |

| Weight change (9 wk to last visit*) (%) | 12.3 (11.5) | 6.0 (9.9) | 0.059 |

| Total insulin dose 9 wk after diagnosis (U/kg/d) | 0.54 (0.25) | 0.63 (0.21) | 0.27 |

| Total insulin dose at the last available visit* (U/kg/d) | 0.70 (0.34) | (0.55) (0.45) | 0.22 |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. p-values that are statistically significant are in bold.

Only for participants with follow-up ≥1 yr since diagnosis (lean: n = 26, obese: n = 15).

In the new-onset period (but at least 3 wk after diagnosis, median 6.9 wk), obese patients, compared with lean, had significantly higher circulating concentrations of the proinflammatory adipokines leptin (p = 0.0001), visfatin (p = 0.0001), chemerin (p = 0.001), and lower concentrations of the anti-inflammatory adipokines total adiponectin (p = 0.038) and omentin (p = 0.003). The results remained significantly different after adjustment for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage of pubertal development (Table 2). BMI percentile significantly correlated with serum adipokine values after adjustment for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage (Table 2). Leptin levels, which were measured in the new-onset period, were positively correlated with C-peptide levels (r2 = 0.36, p < 0.0001) and with insulin dose (U/kg/d) in the new-onset period (r2 = 0.23, p = 0.003) but not with insulin dose at the last visit (p = 0.23). The significance of the association between obesity and leptin levels persisted after adjustment for C-peptide and insulin dose in the new-onset period, in addition to race/ethnicity and Tanner stage (p = 0.006).

Table 2.

Serum concentrations of adipokines and inflammatory cytokines: comparison between lean and obese type 1 diabetes children and correlation with BMI percentile

| Lean | Obese | p-value* | Adjusted p-value† | Correlation with BMI percentile‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 3491 (1846–6508) | 21 778.5 (9131–25 959) | 0.0001 | 0.006 | 0.001 (0.01) |

| Total adiponectin (ng/mL) | 7798.5 (6937–10 071) | 5861.5 (3915–9518) | 0.038 | 0.040 | −0.003 (0.004) |

| HMW adiponectin (ng/mL) | 4355.5 (3046–6489) | 2604.5 (1921–5689) | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.003 (0.022) |

| Omentin (μg/mL) | 4.8 (4.3–5.9) | 4.1 (3.4–4.9) | 0.003 | 0.031 | −0.020 (0.005) |

| Chemerin (ng/mL) | 98.4 (79.4–120.0) | 125.1 (105.8–141.2) | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.096 (0.59) |

| Visfatin (ng/mL) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.002 (0.004) |

| Resistin (ng/mL) | 1.2 (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.53 | 0.66 | −0.002 (0.57) |

| TNF-alpha (pg/mL) | 12.4 (9.3–15.1) | 16.3 (10.9–21.0) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.156 (0.001) |

| IFN-gamma (pg/mL) | 1.8 (0.2–12.0) | 3.7 (0.2–11.8) | 0.72 | 0.83 | −0.044 (0.69) |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 29.0 (16.4–46.2) | 21.6 (15.6–85.8) | 0.096 | 0.074 | 0.337 (0.094) |

| Il-12 (pg/mL) | 1.3 (0.14–4.3) | 1.7 (0.2–5.6) | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.032 (0.77) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 2.4 (0.4–7.3) | 7.1 (4.2–8.5) | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.037 (0.50) |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 6.7 (4.9–9.8) | 6.8 (2.9–10.4) | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.062 (0.19) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.5 (1.6–3.2) | 4.8 (3.7–6.0) | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 5.36 (0.048) |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HMW, high molecular weight; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. Values are median (25th–75th percentiles). p-values that are statistically significant are in bold.

Raw comparison of lean and obese groups.

Comparison between lean and obese groups adjusted for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage.

Numbers are coefficient (p-value) for the variable, adjusted for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage.

As a previous study (21) in youth ≥10 yr of age with established type 1 diabetes reported lower leptin levels in participants with very high HbA1c, we studied the relationship between 9-wk HbA1c and serum leptin levels in children <10 and ≥10 yr of age. Multivariate analysis indicated that, among youth ≥10 yr, leptin levels were significantly lower in those with 9-wk HbA1c ≥9.9% (85 mmol/mol) (90th percentile of the distribution), compared to levels in their counterparts with HbA1c < 9.9% (85 mmol/mol), and higher in obese or African-American youth compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts (p = 0.0001, r2 = 0.85, n = 25). Among children <10 yr, leptin was lower in those with HbA1c ≥6.9% (52 mmol/mol) (25th percentile of the distribution) (p = 0.0002, r = 0.59, n = 22) and higher in obese children, while race/ethnicity was not independently associated with leptin levels. Gender, Tanner stage, HbA1c at diagnosis, and number of positive islet autoantibodies were not independently associated.

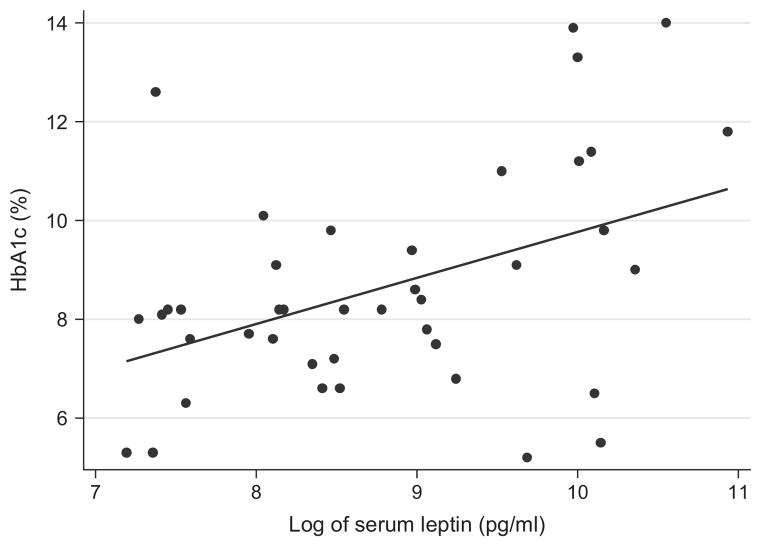

Including only children with follow-up of ≥1 yr (n = 41, median diabetes duration of 1.6 yr, range 1–2 yr), higher leptin levels in the new-onset period predicted higher HbA1c at the last visit (p = 0.001) (Fig. 1) and larger percent of body weight increase among the lean (r = 0.22, p = 0.008), not the obese, children (p = 0.92). In fact, after adjustment for duration of diabetes and race/ethnicity, HbA1c at the last visit (i.e., 1–2 yr after diagnosis) was 2.37 percent points (25.9 mmol/mol) higher in children whose leptin levels at onset were in the highest quartile of the distribution (i.e., ≥20 926.5 pg/mL) than in children with lower leptin concentrations, and 2.82 percent points (30.8 mmol/mol) higher in African-American children than in non-Hispanic white children. Of note, BMI percentile and percent of body weight change were not independent predictors of HbA1c at 1–2 yr. Leptin levels at onset, race/ethnicity and duration of diabetes accounted for 48% of the variation of HbA1c at the last visit (p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Serum leptin concentrations in the new-onset period and HbA1c (%) between 1 and 2 yr after diagnosis of autoimmune type 1 diabetes in children (n = 41, p = 0.001, r = 0.23).

Table 3.

Predictors of HbA1c* at the last follow-up (n = 41, p < 0.0001, r2 = 0.48)

| Coefficient | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes duration (yr) | 3.33 | 1.01–5.61 | 0.006 |

| Race/ethnicity: % | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| African-American | 2.82 | 0.83–4.82 | 0.007 |

| Hispanic | 0.28 | −0.99–1.54 | 0.44 |

| Leptin at diagnosis†: % | |||

| Quartiles 1st, 2nd, 3rd | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Highest quartile | 2.37 | 0.97–3.76 | 0.001 |

p-values that are statistically significant are in bold.

Analysis conducted with HbA1c in %.

20 926.5 pg/mL was the 75th percentile (highest quartile) of the distribution.

Chemerin levels were significantly higher in type 1 diabetes children who were obese (p = 0.025), ≥10 yr old (p = 0.019) and had higher HbA1c at diagnosis (p = 0.022) (p = 0.0004, r2 = 0.36, n = 44 for the model). For the remaining adipokines that were statistically different between obese and lean children, i.e., visfatin, adiponectin, and omentin, we did not observe independent effects of gender, age, Tanner stage, race/ethnicity, DKA, glucose, number of islet autoantibodies, or HbA1c at diagnosis; or HbA1c at the 9-wk visit, after adjustment for obesity.

Among the circulatory cytokines that we studied, only TNF-alpha concentrations were increased in obese compared with lean children (p = 0.002) (Table 2). In addition, female gender was independently associated with higher TNF-alpha after adjustment for obesity and race/ethnicity (p = 0.0003, r2 = 0.37, n = 50). There was a significant inverse correlation with between TNF-alpha levels and omentin (p = 0.037, coefficient = −1.91) while we did not find correlation with other adipokines.

The marker of inflammation C-reactive protein (CRP) was also significantly higher in obese than lean children after adjustment for potential confounders (p < 0.002) (Table 2). CRP was not independently correlated with any of the adipokines and cytokines that we studied, HbA1c at diagnosis, at 9 wk or at the last visit.

Discussion

In children with new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes, obesity was associated with higher proinflammatory markers including leptin, visfatin, chemerin, and TNF-alpha, and lower anti-inflammatory adipokines such as omentin, after adjustment for race/ethnicity and Tanner stage.

In the new-onset period, higher HbA1c was associated with lower leptin levels. This finding is consistent with previous reports (21) and has been attributed to insulin deficiency, as leptin production is stimulated by insulin (22, 27). Supporting this explanation, leptin was positively correlated with C-peptide and insulin dose (U/kg/d) in the new-onset period. Interestingly, in younger children, this association was already present at lower levels of HbA1c. Of note, higher leptin in the new-onset period was a predictor of poorer metabolic control at the last follow-up (1–2 yr after diagnosis). Soliman et al. previously reported that simultaneous HbA1c and leptin levels have opposite relationships at onset and in established diabetes (22). Studies are needed to understand whether the association between leptin and poor metabolic control on follow-up is causal or if leptin is simply a marker of the truly causative factors. In addition, the positive correlation between leptin and HbA1c 1–2 yr later might contribute to explain the elevated HbA1c that has been reported in patients who are obese (28) and thus have higher leptin levels.

We found that African-American children ≥10 yr of age with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes had higher levels of leptin, consistently with previous reports in healthy adults (29–31). The observed correlation between leptin and HbA1c 1–2 yr later may provide a biological basis for the previously described poorer diabetes control and higher risk of complications in African-American patients after adjustment for socioeconomic factors (32, 33). Similarly to the relationship with obesity, leptin might be a marker of the truly causative factor, such as insulin resistance, or could have a pathogenic role on the association between African-American race and high HbA1c. Larger studies are needed to assess the effect of race on leptin levels in children younger than 10 yr.

This is the first report of suppressed serum levels of omentin-1 in obese children with type 1 diabetes. Omentin-1, an anti-inflammatory adipokine secreted by visceral adipose tissue, has been reported negatively associated with obesity in other populations (15, 34, 35). The proinflammatory adipokines visfatin and the recently described chemerin had not been previously studied in children at the onset of type 1 diabetes. Our findings are consistent with prior reports that visfatin correlates with the volume of visceral fat, and is increased in obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease (19), and chemerin is elevated in obesity (34), type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia (36, 37), and in children with type 1 diabetes compared with healthy controls (20). We also found that circulating TNF-alpha was higher in obese compared with lean children with type 1 diabetes, and independently elevated in females. TNF-alpha is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by monocytes and macrophages, with increased levels in adipose tissue and blood of obese individuals (11, 38). Recent data suggest that dysregulation of adipose tissue is an early event in the progression of the metabolic syndrome (34) and thus might critically contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease in obese children with type 1 diabetes.

Our study has several potential important therapeutic implications, as adipokines are druggable targets (14). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma), expressed in adipose tissue, regulates adipose tissue functionality and insulin sensitivity. PPARgamma agonists such as thiazolidinediones can downregulate inflammatory adipokines and upregulate anti-inflammatory cytokines (39). Increasing our understanding of the contribution of adipose-induced biomarkers to type 1 diabetes complications may uncover new pathways for prevention.

One limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size; confirmation of our observations in larger cohorts is required. An additional limitation is the lack of information on socioeconomic status, which may also affect the relationship between obesity and HbA1c; however, because serum adipokine levels are likely unrelated to socioeconomic factors, the probability of these confounding our results is low.

In conclusion, obese children with autoimmune type 1 diabetes have an abnormal adipose tissue-induced biomarker profile that may further increase cardiovascular risk. Establishing the profile of adiposity-induced biomarkers in children with autoimmune type 1 diabetes is a critical prerequisite to understanding the complex interaction among obesity, inflammation and type 1 diabetes. Future studies are warranted targeting leptin and other adipokines in young children with type 1 diabetes, especially those who are obese and exhibit poor glycemic control.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by a Pediatric Pilot Award grant from Texas Children’ Hospital. We acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Ms Andrene McDonald (Research Coordinator) and Dr Dinakar Iyer, who conducted serum C-peptide analysis.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. Epub 19 January 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G, Group ES. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. Epub 2 June 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu LL, Lawrence JM, Davis C, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in youth with diabetes in USA: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11:4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00519.x. Epub 29 May 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaminski BM, Klingensmith GJ, Beck RW, et al. Body Mass Index at the Time of Diagnosis of Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes in Children. J Pediatr. 2012;162:736–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.09.017. Epub 25 October 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redondo MJ, Rodriguez LM, Escalante M, O’Brian Smith E, Balasubramanyam A, Haymond MW. Beta cell function and BMI in ethnically diverse children with newly diagnosed autoimmune type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00875.x. Epub 31 May 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purnell JQ, Zinman B, Brunzell JD, Group DER. The effect of excess weight gain with intensive diabetes mellitus treatment on cardiovascular disease risk factors and atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes mellitus: results from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study (DCCT/EDIC) Circulation. 2013;127:180–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.077487. Epub 6 December 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcovecchio ML, Chiarelli F. Microvascular disease in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and obesity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1624-9. Epub 20 August 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah AS, Dolan LM, Lauer A, et al. Adiponectin and arterial stiffness in youth with type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(7–8):717–721. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0070. Epub 20 November 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maahs DM, Jalal D, Chonchol M, Johnson RJ, Rewers M, Snell-Bergeon JK. Impaired renal function further increases odds of 6-year coronary artery calcification progression in adults with type 1 diabetes: the CACTI study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2607–2614. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2538. Epub 10 July 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. Epub 15 December 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. Epub 22 January 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Garg R. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111:1448–1454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. Epub 23 March 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, et al. Reciprocal association of C-reactive protein with adiponectin in blood stream and adipose tissue. Circulation. 2003;107:671–674. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055188.83694.b3. Epub 13 February 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382:250–252. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. Epub 18 July 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan BK, Adya R, Farhatullah S, et al. Omentin-1, a novel adipokine, is decreased in overweight insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: ex vivo and in vivo regulation of omentin-1 by insulin and glucose. Diabetes. 2008;57:801–808. doi: 10.2337/db07-0990. Epub 5 January 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–312. doi: 10.1038/35053000. Epub 24 February 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuldiner AR, Yang R, Gong DW. Resistin, obesity and insulin resistance--the emerging role of the adipocyte as an endocrine organ. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1345–1346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111013451814. Epub 17 January 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozaoglu K, Bolton K, McMillan J, et al. Chemerin is a novel adipokine associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4687–4694. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0175. Epub 21 July 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuhara A, Matsuda M, Nishizawa M, et al. Visfatin: a protein secreted by visceral fat that mimics the effects of insulin. Science. 2005;307:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1097243. Epub 18 December 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verrijn Stuart AA, Schipper HS, Tasdelen I, et al. Altered plasma adipokine levels and in vitro adipocyte differentiation in pediatric type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:463–472. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1858. Epub 25 November 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snell-Bergeon JK, West NA, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al. Inflammatory markers are increased in youth with type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH Case-Control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2868–2876. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1993. Epub 8 April 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliman AT, Omar M, Assem HM, et al. Serum leptin concentrations in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: relationship to body mass index, insulin dose, and glycemic control. Metabolism. 2002;51:292–296. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.30502. Epub 12 March 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huml M, Kobr J, Siala K, et al. Gut peptide hormones and pediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus. Physiol Res. 2011;60:647–658. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931995. Epub 18 May 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314:1–27. Epub 24 February 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oak S, Gilliam LK, Landin-Olsson M, et al. The lack of anti-idiotypic antibodies, not the presence of the corresponding autoantibodies to glutamate decarboxylase, defines type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5471–5476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800578105. Epub 28 March 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bingley PJ, Bonifacio E, Mueller PW. Diabetes Antibody Standardization Program: first assay proficiency evaluation. Diabetes. 2003;52:1128–1136. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1128. Epub 30 April 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanaki K, Becker DJ, Arslanian SA. Leptin before and after insulin therapy in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1524–1526. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5653. Epub 14 May 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Vliet M, Van der Heyden JC, Diamant M, et al. Overweight is highly prevalent in children with type 1 diabetes and associates with cardiometabolic risk. J Pediatr. 2010;156:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.017. Epub 13 March 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azrad M, Gower BA, Hunter GR, Nagy TR. Racial differences in adiponectin and leptin in healthy premenopausal women. Endocrine. 2013;43:586–592. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9797-6. Epub 18 September 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan UI, Wang D, Sowers MR, et al. Race-ethnic differences in adipokine levels: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Metabolism. 2012;61:1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.02.005. Epub 27 March 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Wassel CL, Ding J, et al. Associations of body mass index and insulin resistance with leptin, adiponectin, and the leptin-to-adiponectin ratio across ethnic groups: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.07.011. Epub 30 August 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Twombly JG, Long Q, Zhu M, et al. Diabetes care in black and white veterans in the southeastern U. S Diabetes Care. 2010;33:958–963. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1556. Epub 28 January 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petitti DB, Klingensmith GJ, Bell RA, et al. Glycemic control in youth with diabetes: the SEARCH for diabetes in Youth Study. J Pediatr. 2009;155:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.025. Epub 1 August 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jialal I, Devaraj S, Kaur H, Adams-Huet B, Bremer AA. Increased chemerin and decreased omentin-1 in both adipose tissue and plasma in nascent metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E514–E517. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3673. Epub 11 January 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan BK, Pua S, Syed F, Lewandowski KC, O’Hare JP, Randeva HS. Decreased plasma omentin-1 levels in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1254–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02568.x. Epub 3 December 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weigert J, Neumeier M, Wanninger J, et al. Systemic chemerin is related to inflammation rather than obesity in type 2 diabetes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72:342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03664.x. Epub 30 June 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bluher M, Rudich A, Kloting N, et al. Two patterns of adipokine and other biomarker dynamics in a long-term weight loss intervention. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:342–349. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1267. Epub 23 December 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. Epub 1 January 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma AM, Staels B. Review: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and adipose tissue–understanding obesity-related changes in regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:386–395. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1268. Epub 7 December 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]