Hydrogen sulfide affects inward-rectifying K+ channels in guard cells and implicates an additional, but as yet unidentified, signaling pathway in stomatal closure.

Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is the third biological gasotransmitter, and in animals, it affects many physiological processes by modulating ion channels. H2S has been reported to protect plants from oxidative stress in diverse physiological responses. H2S closes stomata, but the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Here, we report the selective inactivation of current carried by inward-rectifying K+ channels of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) guard cells and show its close parallel with stomatal closure evoked by submicromolar concentrations of H2S. Experiments to scavenge H2S suggested an effect that is separable from that of abscisic acid, which is associated with water stress. Thus, H2S seems to define a unique and unresolved signaling pathway that selectively targets inward-rectifying K+ channels.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a small bioactive gas that has been known for centuries as an environmental pollutant (Reiffenstein et al., 1992). H2S is soluble in both polar and, especially, nonpolar solvents (Wang, 2002), and has recently come to be recognized as the third member of a group of so-called biological gasotransmitters. Most importantly, H2S shows both physical and functional similarities to the other gasotransmitters nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (Wang, 2002), and it has been shown to participate in diverse physiological processes in animals, including cardioprotection, neuromodulation, inflammation, apoptosis, and gastrointestinal functions among others (Kabil et al., 2014). Less is known about H2S molecular targets and its modes of action. H2S can directly modify specific targets through protein sulfhydration (the addition of an -SH group to thiol moiety of proteins; Mustafa et al., 2009) or reaction with metal centers (Li and Lancaster, 2013). It can also act indirectly, reacting with NO to form nitrosothiols (Whiteman et al., 2006; Li and Lancaster, 2013). Among its molecular targets, H2S has been reported to regulate ATP-dependent K+ channels (Yang et al., 2005), Ca2+-activated K+ channels, T- and L-type Ca2+ channels, and transient receptor potential channels (Tang et al., 2010; Peers et al., 2012), suggesting H2S as a key regulator of membrane ion transport.

In plants, H2S is produced enzymatically by the desulfhydration of l-Cys to form H2S, pyruvate, and ammonia in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme l-Cys desulfhydrase (Riemenschneider et al., 2005a, 2005b), DES1, that has been characterized in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Alvarez et al., 2010). Alternatively, H2S can be produced from d-Cys by d-Cys desulfhydrase (Riemenschneider et al., 2005a, 2005b) and in cyanide metabolism by β-cyano-Ala synthase (García et al., 2010). H2S action was originally related to pathogenesis resistance (Bloem et al., 2004), but in the last decade it has been proven to have an active role in signaling, participating in key physiological processes, such as germination and root organogenesis (Zhang et al., 2008, 2009a), heat stress (Li et al., 2013a, 2013b), osmotic stress (Zhang et al., 2009b), and stomatal movement (García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010; Lisjak et al., 2010, 2011; Jin et al., 2013). Moreover, H2S was reported to participate in the signaling of plant hormones, including abscisic acid (ABA; García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010; Lisjak et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2013; Scuffi et al., 2014), ethylene (Hou et al., 2013), and auxin (Zhang et al., 2009a).

ABA is an important player in plant physiology. Notably, upon water stress, ABA triggers a complex signaling network to restrict the loss of water through the transpiration stream, balancing these needs with those of CO2 for carbon assimilation. In the guard cells that surround the stomatal pore, ABA induces an increase of cytosolic-free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt), elevates cytosolic pH (pHi), and activates the efflux of anions, mainly chloride, through S- and R-type anion channels. The increase in [Ca2+]cyt inactivates inward-rectifying K+ channels (IKIN); anion efflux depolarizes the plasma membrane, and together with the rise in pHi, it activates K+ efflux through outward-rectifying K+ channels (IKOUT; Blatt, 2000; Schroeder et al., 2001). These changes in ion flux, in turn, generate an osmotically driven reduction in turgor and volume and closure of the stomatal pore. All three gasotransmitters have been implicated in regulating the activity of guard cell ion channels, but direct evidence is available only for NO (Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Sokolovski et al., 2005). Here, we have used two-electrode voltage clamp measurements to study the role of H2S in the regulation of the guard cell K+ channels of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Our results show that H2S selectively inactivates IKIN and that this action parallels that of stomatal closure. These results confirm H2S as a unique factor regulating guard cell ion transport and indicate that H2S acts in a manner separable from that of ABA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

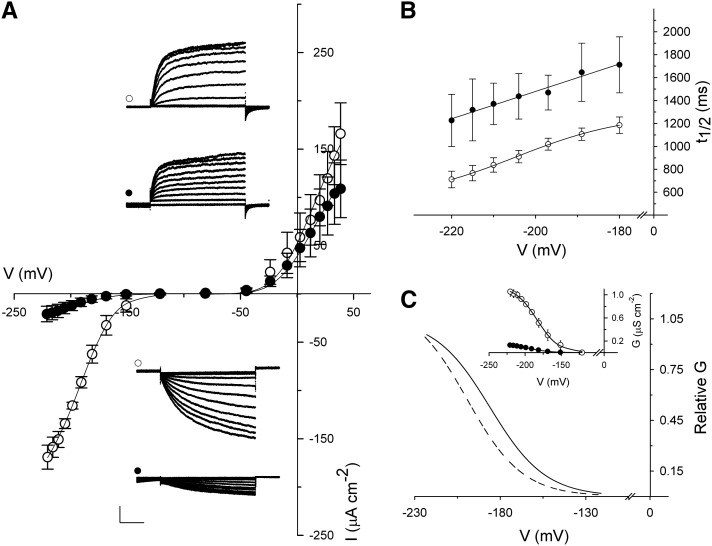

To address whether H2S-induced stomatal closure is mediated by changes in the activities of these channels, we recorded currents by two-electrode voltage clamp. IKIN and IKOUT currents were resolved on the basis of their voltage-dependent kinetics and challenging with H2S donor GYY4137 (for p-methoxyphenyl(morpholino)phosphinodithioic acid). Follow impalement current-voltage recordings were carried out to confirm a stable baseline of channel activities for 5 to 10 min before the H2S donor GYY4137 was added. We observed a complete response to the H2S donor within 2 to 3 min of additions, indicating a halftime for response to the donor of less than 120 s. Most impalements could be held for 20 to 30 min only and therefore, did not allow us to assess current recovery after washout of the H2S donor. Figure 1A shows current traces and the mean steady-state currents as a function of voltage (I-V curves) from guard cells before and after 5 min of exposure to 10 μm GYY4137. The I-V curves show the characteristic voltage dependence of both IKOUT and IKIN as previously described (Blatt, 1992; Gradmann et al., 1993; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003). In 10 mm KCl, voltages positive of −40 mV yielded IKOUT that increased in amplitude with the voltage. Mean IKOUT at +30 mV was +120 ± 28 and +91 ± 30 μA cm−2 before and after exposure to GYY 4137, respectively, indicating a small but not very significant effect on the IKOUT. Voltages negative of −100 mV were marked by a strong inward-directed current typical of IKIN, and the current amplitude increased with negative-going voltages. We found that IKIN at −220 mV was reduced by roughly 90% by H2S donor treatments, yielding a mean IKIN of −21 ± 8 μA cm−2 compared with −169 ± 12 μA cm−2 for the control. Exposure to the H2S donor also affected the halftimes for IKIN activation. Mean halftimes for IKIN activation at −220 mV were 710 ± 70 ms in the control and 1,230 ± 230 ms after exposure to 10 μm GYY4137, indicating a significant change in gating of IKIN (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

H2S selectively affects IKIN. A, Currents through IKOUT and IKIN above and below the voltage axis, respectively, recorded under voltage clamp from tobacco guard cells. Voltages were clamped from a holding voltage of −100 mV in 6-s steps between −220 and +120 mV and 4-s steps between −80 and +40 mV. Data are means ± se of n = 5 guard cells bathed in 5 mm Ca2+-MES buffer (pH 6.1) with 10 mm KCl before (white circles) and 5 min after (black circles) adding 10 μm GYY4137. Insets, Current traces for IKOUT and IKIN for control and H2S treatment. Currents are cross referenced to the current-voltage curves by symbols. Bars = 2 s (horizontal); 50 μA cm−2 (vertical). B, Mean activation halftimes as a function of voltage derived from current traces, including those in A, and cross referenced by symbols. C, Steady-state conductance as a function of voltage normalized to Gmax in the control (black line) and with 10 μm GYY4137 (dashed line). Inset, Steady-state conductance as a function of voltage. Curves were jointly fitted to Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) with gating charge-δ held in common.

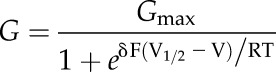

Steady-state current through any ion channel depends on the ensemble conductance (G), which is the product of the number of functional channels at the plasma membrane (N), the single-channel conductance for a given ion species (γX), and the gating characteristics of the channel that describe the open probability of the channel (Po). Plotting the conductance of IKIN before and after exposure to H2S as a function of voltage allowed a separation of the differences in the gating characteristics before and after H2S donor treatments (Fig. 1C). The G-V curves were jointly fitted to a modified Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to determine the maximum conductance (Gmax) and the gating characteristics of IKIN (Table I). For joint fittings, δ was held in common, and it yielded statistically and visually satisfactory fittings with a value of −1.66 ± 0.04. As expected from the I-V data, the H2S donor suppressed the Gmax significantly by up to 90% relative to the control. We cannot distinguish from these data whether this effect was mediated through a change in the number of channels available for activation (N) or the single-channel conductance (γK). Such detail would require single-channel analysis. However, we noted that the H2S donor displaced V1/2 by approximately −12 mV (Fig. 1C; Table I), indicating that the H2S not only resulted in a decrease of the maximum conductance but also affected the voltage dependence for gating of IKIN. An action on V1/2 cannot be explained solely by an effect on N or γK. In short, H2S selectively inactivated IKIN.

Table I. Fitted gating characteristics for IKIN.

Statistical differences after ANOVA as determined by Student Newman-Keuls test. P values are indicated for each parameter comparing control and H2S treatments.

| V1/2 (P = 0.006) | δ | GKIN (P < 0.001) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | μs cm−2 | ||

| Control | −183 ± 0.5 | −1.67 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.01 |

| +10 μm GYY4137 | −195 ± 3 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

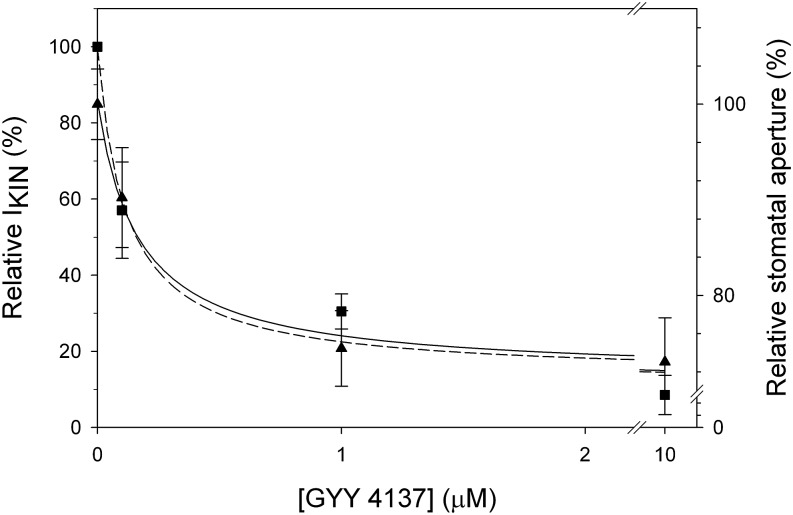

The inactivation of the K+ current is consistent with GYY4137 action in suppressing K+ uptake and promoting stomatal closure, and it argues against earlier (and statistically undocumented) claims that H2S donors promote stomatal opening (Lisjak et al., 2010, 2011). To assess the action of H2S effect on stomatal movement, we measured apertures from stomata treated with different concentrations of the H2S donor. Epidermal peels were placed in opening buffer under light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1 for 2 h to open the stomata before transfer to 5 mm Ca2+-MES (pH 6.1) with 60 mm KCl supplemented with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 μm GYY4137 for 90 min. Apertures were recorded immediately before and after H2S treatments, and the data were normalized to the controls (Fig. 2). Exposure to the control buffer alone yielded stomatal apertures of 6.6 ± 1.8 μm; treatments with H2S donor resulted in stomatal apertures ranging from 5.9 to 4.8 μm. Fitting the data to the hyperbolic decay function yielded an apparent Ki of 160 ± 40 nΜ for GYY4137. We carried out parallel measurements of IKIN to determine its dose dependence after treating guard cells in buffer supplemented with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 μm GYY4137. Figure 2 also shows the mean values for IKIN again normalized to the control treatment. Increasing the concentration of H2S donor, indeed, enhanced IKIN inactivation. Fitting these data to hyperbolic decay function gave a Ki of 120 ± 70 nm for GYY4137, a value that did not significantly differ from that for stomatal closure compared with t test (P = 0.735). These results, thus, confirm the close kinetic relationship between IKIN inactivation and stomatal closure in H2S.

Figure 2.

H2S affects stomatal aperture and K+ current in a dose-dependent manner with similar concentration dependencies. Mean stomatal apertures ± se (n = 50) recorded from epidermal peels of tobacco (triangles) and mean IKIN ± se (n = 5) at −200 mV (squares) normalized to the controls without GYY 4137 treatment. A hyperbolic decay function was fitted to each set of data, yielding a Ki of 160 ± 40 nm GYY4137 for the aperture response (solid line) and 120 ± 70 nm GYY4137 for current inactivation (dashed line).

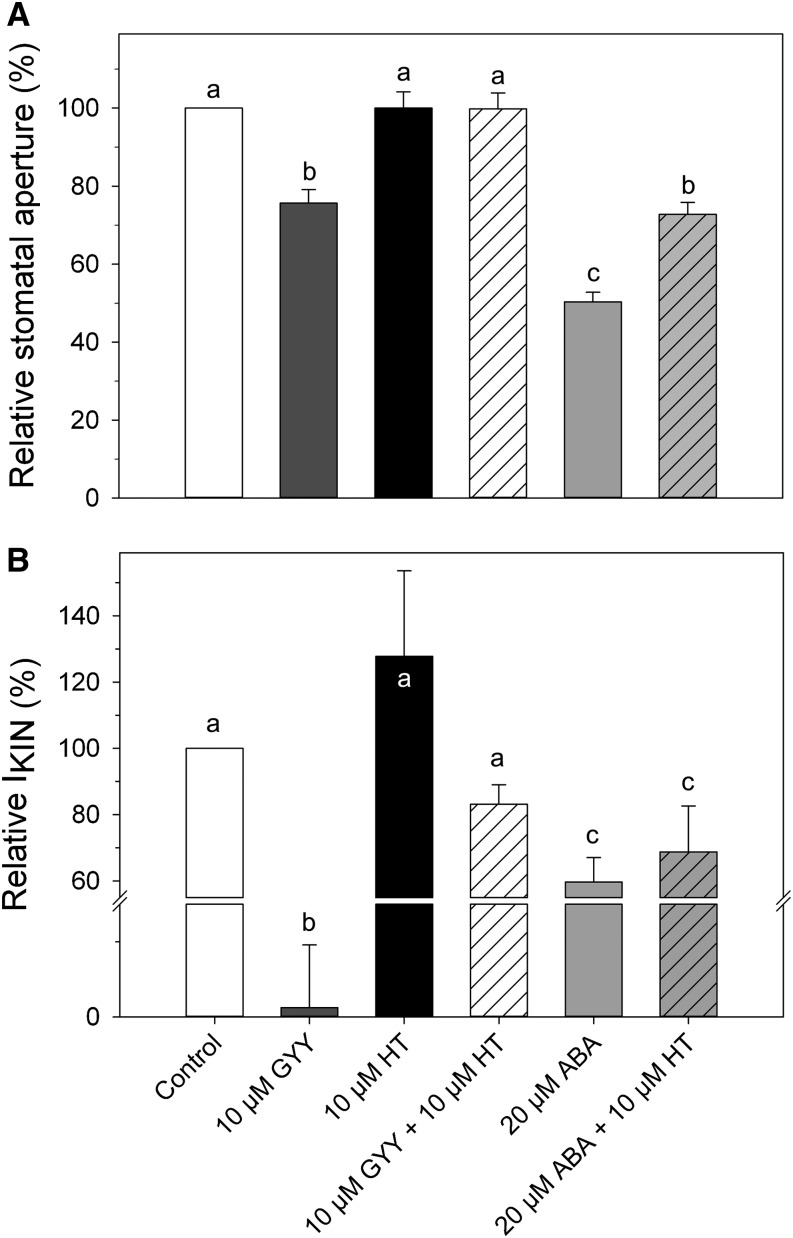

The similar effects of H2S and ABA on IKIN and stomatal aperture prompted us to explore the connection between H2S and ABA signaling, which was suggested by García-Mata and Lamattina (2010). A similar set of protocols was used as above. Epidermal peels were pretreated for 2 h with opening buffer and light for 90 min before treatments in 5 mm Ca2+-MES (pH 6.1) with 10 mm KCl with and without supplement of five distinct combinations of stomatal effectors: 10 μm GYY4137, 10 μm hypotaurine (HT), 10 μm GYY4137 + 10 μm HT, 20 μm ABA, and 20 μm ABA + 10 μm HT. HT interacts with free sulfide to form thiotaurine, effectively scavenging free H2S in solution (Ortega et al., 2008). Figure 3A shows the percentage of stomatal closure induced by each treatment relative to the control. Measurements were carried out separately at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and yielded starting apertures (4.9 ± 0.1 μm) that differed quantitatively from those recorded at the University of Glasgow. Qualitatively, however, the results were consistent between data sets. Exposure to 10 μm GYY4137 and 20 μm ABA resulted in 60% and 80% reductions in stomatal aperture, corresponding to apertures of 3.2 ± 0.1 and 2.2 ± 0.07 μm, respectively. Treatment with HT alone had no effect on stomatal aperture. When epidermal peels were treated with both 10 μm GYY4137 and HT, the effect of the H2S donor was alleviated, yielding apertures of 4.6 ± 0.1 μm, similar to those of the control. Treatment of epidermal peels with 20 μm ABA + 10 μm HT partially suppressed the effect of ABA on aperture, resulting in a reduction to 70% pore width compared with control treatment.

Figure 3.

ABA and H2S affect aperture and IKIN in parallel. A, Mean stomatal apertures ± se (n > 190 per treatment), including the control (100%), after treatments with 10 μm GYY4137 (GYY; dark-gray bar), 10 μm HT (black bar), 10 μm GYY4137 + 10 μm HT (white striped bar), 20 μm ABA (light-gray bar), or 20 μm ABA + 10 μm HT (light-gray striped bar). Letters indicates statistical differences by ANOVA (P < 0.05) as determined by Student Newman-Keuls test. B, Mean current ± se (n = 5) for IKIN recorded under voltage clamp as in Figure 1 and normalized to IKIN at −200 mV in the control. Letters indicates statistical differences by ANOVA (P < 0.05) as determined by Student Newman-Keuls test.

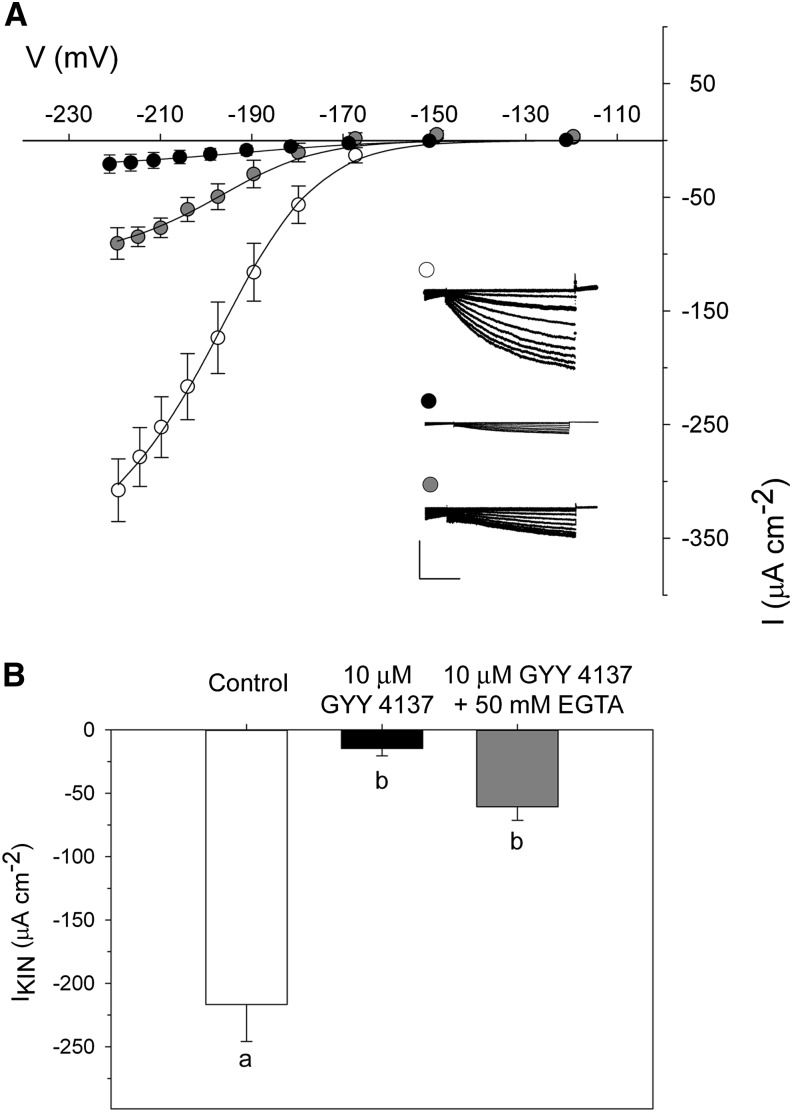

Given the role of [Ca2+]cyt in ABA signaling and control of IKIN (Blatt, 2000; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003), we sought to test whether the H2S-induced effect on IKIN might be mediated by the Ca2+ intermediate. For this purpose, we loaded guard cells from the microelectrode with 50 mm EGTA, which chelates and buffers Ca2+ to suppress its elevation (Grabov and Blatt, 1998; Chen et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). After being impaled, guard cells were held for a period of 5 min to ensure loading with EGTA. Thereafter, the guard cells were either maintained in 5 mm Ca2+-MES (pH 6.1) with 10 mm KCl or challenged with 10 μm GYY4137 for a period of 10 min. In the absence of H2S donor, we observed no substantive effect on IKIN. The mean amplitude at −200 mV was −217 ± 29 μA cm−2. In the presence of H2S donor, IKIN was suppressed, yielding a mean current of −61 ± 11 μA cm−2 (Fig. 4A). EGTA did yield a small but not very significant recovery of IKIN in the presence of the H2S donor (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that H2S acts in a manner that is largely independent of [Ca2+]cyt.

Figure 4.

H2S inactivates currents from IKIN in a Ca2+-independent manner. A, Current-voltage (I-V) curves for IKIN recorded under voltage clamp as in Figure 1. Guard cells were bathed in 10 mm KCl (white circles) or 10 mm KCl supplemented with 10 μm GYY4137 (gray circles) and loaded from the microelectrode with 50 mm EGTA. The I-V curve for guard cells treated with only 10 μm GYY4137 (black circles) from Figure 1 is included for visual reference. Data are means ± se of n = 5 guard cells for each data set. Curves were jointly fitted to Boltzmann function (lines), with V1/2 and gating charge-δ held in common. Insets present current traces recorded under voltage clamp. Bars = 2 s (horizontal) and 200 μA cm−2 (vertical). B, Mean IKIN at −205 mV from the current recordings for control (white bars) and 10 μm GYY4137 (black bars) treatments in the presence of EGTA and 10 μm GYY4137 without EGTA (gray bars). Lettering indicates statistical differences by ANOVA (P < 0.001) as determined by Student Newman-Keuls test.

We also investigated the effect of the above compounds and their combinations on IKIN, again following the same set of protocols. Figure 3B displays the mean percentage reduction of the IKIN amplitude at −200 mV before and after the exposure to each of the treatments. H2S resulted in almost complete loss of IKIN, which is shown in Figure 1. ABA treatment reduced IKIN by 62%, resulting in a mean current of −170 ± 39 μA cm−2 at −200 mV. Interestingly, exposure of guard cells to 10 μm HT yielded IKIN of −292 ± 64 μA cm−2, marginally greater in amplitude compared with −241 ± 40 μA cm−2 for the control, although this difference was not very significant. Suppression of the current by H2S was blocked when guard cells were treated with the combination of H2S donor and scavenger, resulting in IKIN of similar amplitude as the control treatment. In contrast, the reduction of IKIN evoked by ABA was not prevented by adding HT, which yielded a mean IKIN of −174 ± 35 μA cm−2. Altogether, these data indicate that H2S acts in a manner paralleling that either of ABA or upstream of the hormone.

Stomatal movement is a highly coordinated process that is generally recognized to engage several signaling networks leading to the regulation of K+ channels, anion channels, and H+-ATPases at the plasma membrane as well as a complementary assembly of transporters at the tonoplast (Blatt, 2000). For ABA-evoked stomatal closure, this process includes inactivation of IKIN through changes in [Ca2+]cyt and activation of the IKOUT mediated by a rise in pHi (Blatt, 1990; Blatt and Armstrong, 1993; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 2009). Our findings that H2S differentially affects IKIN and IKOUT and that IKIN inactivation is dose dependent with an apparent Ki in the low nanomolar range confirm a subcellular target for the action of this gasotransmitter. The timescale of the H2S-triggered changes in channel gating is entirely in keeping with posttranslational regulation, which is in contrast with the slower effects of ABA that, over timescales of many minutes or hours, clearly rely on the transcription regulation and trafficking of the channel proteins (Pilot et al., 2003; Sutter et al., 2007; Eisenach, et al., 2012, 2014). These findings together with evidence that H2S mediates stomatal closure and that its scavenging partially suppresses closure in ABA suggest a connection with the hormone, albeit a loose one. Notably, H2S scavenging failed to reverse ABA-evoked inactivation of IKIN (Fig. 3), and we found that stomatal closure was enhanced when treated with ABA and the H2S scavenger compared with treatment with ABA alone. These observations are difficult to reconcile with a role for H2S as an intermediate in ABA signaling per se and instead, suggest a partial overlap in signaling pathways.

This interpretation is in agreement with recent studies showing an ABA dependency of H2S effect on stomatal movements (García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010; Scuffi et al., 2014). It also complements substantial evidence for a separate set of intermediates, especially ROS and NO, that trigger the elevation of [Ca2+]cyt and are important for ABA-mediated stomatal closure (Pei et al., 2000; García-Mata and Lamattina, 2002, 2003), and it agrees with our finding that Ca2+ buffering did not substantially rescue IKIN. Guard cells are thought to produce NO in response to ABA through the activity of nitrate reductases (Desikan et al., 2002), and NO action is also dependent on the secondary messengers cGMP and cADPR (Neill et al., 2002). Garcia-Mata et al. (2003) showed that NO promoted the inhibition of IKIN and activated anion efflux through an enhanced sensitivity of internal Ca2+ release to Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane. Notably, the effects of [Ca2+]cyt on IKIN gating and especially, V1/2 are much more pronounced than observed with H2S. Furthermore, NO is also able to modulate IKOUT by direct nitrosylation of the channel or an associated regulatory protein (Sokolovski and Blatt, 2004), but we observed little evidence of an effect on IKOUT current. Therefore, these observations implicate a parallel and as yet uncharacterized signaling pathway that acts on IKIN, thereby overlapping with the well-known pathways leading from ABA to IKIN and stomatal closure.

How might H2S act to modulate IKIN? Nitrosylation of Cys sulfhydryl groups on either the channel itself or on closely associated regulatory proteins has been suggested to mediate the NO-induced block of IKOUT (Sokolovski and Blatt, 2004), and such modifications may be linked to ROS modification of residues within the voltage sensor domain (García et al., 2010). H2S is also capable of covalently modifying protein targets, and the mechanism is equally relevant to IKIN and the proteins that regulate these channels, including protein kinases and phosphatases (Thiel and Blatt, 1994; Li et al., 1998; Michard et al., 2005). In animals, for example, H2S activates ATP-dependent K+ channels through the sulfhydration of a Cys residue of the sulfonurea SUR protein (Babenko et al., 2000). Addition of the SUR inhibitor glibenclamide antagonized the H2S response and prevented the hypotensive effect of H2S (Zhao et al., 2001). In other cases, sulfhydration is suppressed by the reducing agent dithiothreitol and mutants defective in H2S production (Mustafa et al., 2009). Of interest, glibenclamide has also been shown to abolish stomatal closure triggered by ABA and external Ca2+ through the inhibition of anion and IKOUT (Leonhardt et al., 1999). More recent studies, however, have shown only partial suppression by glibenclamide of stomatal closure in ABA, whereas the response to H2S was completely abolished (García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010). These findings suggest that ABC proteins, a major target of glibenclamide, may contribute to channel regulation in guard cells upon H2S exposure. At present, however, there is not sufficient information from any system that would enable realistic predictions of the possible motifs for sulfhydration.

No doubt, future studies with transgenic Arabidopsis lines defective in H2S, NO production, and ABA sensitivity should help clarify the role of H2S in these processes (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003). What is clear, however, is that H2S is active in selectively regulating IKIN of guard cells over timescales consistent with short-term posttranslational modification of specific target proteins. Furthermore, our evidence implicates H2S in a signaling pathway that is separable from that of ABA, although both ABA and H2S modulate stomatal behavior in parallel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material, Chemicals, and Stomatal Assays

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants were grown in Levington F2+S compost under long-day conditions (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle; temperature approximately 26°C and 22°C for day and night, respectively; relative humidity of 60% and 70% for day and night, respectively) under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 of light.

Epidermal peels were obtained from the abaxial side of tobacco leaves and placed in opening buffer comprised of 10 mm Na+-MES (pH 6.1; 10 mm MES titrated to pH 6.1 with NaOH) with 60 mm KCl under light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1 for 2 h before treatment with the H2S donor GYY4137 (Sigma) in the same buffer. Stomata were imaged before and after 90 min of H2S treatment using an LD Achroplan 40× Objective and an Axio-Cam HRc Digital Camera (Zeiss). Apertures were tracked for individual stomata and quantified using IMAGEJ version 1.48 (image.nih.gov/ij/).

Guard Cell Electrophysiology

Currents were recorded under two-electrode voltage clamp using Henry’s EP Software Suite (http://www.psrg.org.uk). Microelectrodes were constructed to give tip resistances of greater than 100 MΩ and filled with 200 mm K+-acetate (pH 7.5) to minimize interference arising from anion leakage from the microelectrode (Blatt and Slayman, 1983; Blatt, 1987; Wang and Blatt, 2011). Electrolyte filling solutions were equilibrated against the resin-bound Ca2+ buffer BAPTA [for 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; Ca2+ sponge; Invitrogen] to prevent Ca2+ loading of the cytosol from the microelectrodes. K+ channel currents were recorded from guard cells bathed under continuous superfusion with 5 mm Ca2+-MES (pH 6.1; 5 mm MES titrated to pH 6.1 with Ca(OH)2; [Ca2+] = 1 mm) plus 10 mm KCl alone and supplemented with reagents as indicated. Recordings typically included a 2-s holding voltage at −100 mV and two to six steps to voltages between −220 and +40 mV. Surface areas of the impaled guard cells were calculated assuming a spheroid geometry (Blatt et al., 1987).

Current voltage analysis and fittings were carried out using Henry’s EP Software Suite and SigmaPlot 11 (SPSS; Systat Software). Conductance-voltage curves were fitted by joint nonlinear least squares and the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm using a modified Boltzmann function of the form

|

(1) |

where Gmax is the maximum conductance, V is the membrane voltage, V1/2 is the voltage at which half-maximum activation of channels occurs, δ is the apparent gating charge, and F, R, and T have their usual meanings.

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± se of n observations, with significance determined using Student’s t test and ANOVA at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amparo Ruiz-Prado for support in plant growth and maintenance.

Glossary

- ABA

abscisic acid

- [Ca2+]cyt

cytosolic-free Ca2+ concentration

- HT

hypotaurine

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- IKIN

inward-rectifying K+ channel

- IKOUT

outward-rectifying K+ channel

- NO

nitric oxide

- pHi

cytosolic pH

Footnotes

This work was supported by the United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant nos. BB/H0024867/1, BB/I024496/1, BB/K015893/1, and BBL001276/1), the Royal Society, London (travel grant no. IE120659), and the Begonia Trust (Studentship to M.P.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Alvarez C, Calo L, Romero LC, García I, Gotor C (2010) An O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase homolog with l-cysteine desulfhydrase activity regulates cysteine homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 152: 656–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko AP, Gonzalez G, Bryan J (2000) Pharmaco-topology of sulfonylurea receptors. Separate domains of the regulatory subunits of K(ATP) channel isoforms are required for selective interaction with K(+) channel openers. J Biol Chem 275: 717–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. (1987) Electrical characteristics of stomatal guard cells: the ionic basis of the membrane potential and the consequence of potassium chlorides leakage from microelectrodes. Planta 170: 272–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. (1990) Potassium channel currents in intact stomatal guard cells: rapid enhancement by abscisic acid. Planta 180: 445–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. (1992) K+ channels of stomatal guard cells. Characteristics of the inward rectifier and its control by pH. J Gen Physiol 99: 615–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. (2000) Cellular signaling and volume control in stomatal movements in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 221–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Armstrong F (1993) K+ channels of stomatal guard cells: abscisic-acid-evoked control of the outward rectifier mediated by cytoplasmic pH. Planta 191: 330–341 [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Rodriguez-Navarro A, Slayman CL (1987) Potassium-proton symport in Neurospora: kinetic control by pH and membrane potential. J Membr Biol 98: 169–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Slayman CL (1983) KCl leakage from microelectrodes and its impact on the membrane parameters of a nonexcitable cell. J Membr Biol 72: 223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem E, Riemenschneider A, Volker J, Papenbrock J, Schmidt A, Salac I, Haneklaus S, Schnug E (2004) Sulphur supply and infection with Pyrenopeziza brassicae influence L-cysteine desulphydrase activity in Brassica napus L. J Exp Bot 55: 2305–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZH, Hills A, Lim CK, Blatt MR (2010) Dynamic regulation of guard cell anion channels by cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration and protein phosphorylation. Plant J 61: 816–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R, Griffiths R, Hancock J, Neill S (2002) A new role for an old enzyme: nitrate reductase-mediated nitric oxide generation is required for abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16314–16318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach C, Chen ZH, Grefen C, Blatt MR (2012) The trafficking protein SYP121 of Arabidopsis connects programmed stomatal closure and K⁺ channel activity with vegetative growth. Plant J 69: 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach C, Papanatsiou M, Hillert EK, Blatt MR (2014) Clustering of the K+ channel GORK of Arabidopsis parallels its gating by extracellular K+. Plant J 78: 203–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García I, Castellano JM, Vioque B, Solano R, Gotor C, Romero LC (2010) Mitochondrial beta-cyanoalanine synthase is essential for root hair formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22: 3268–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C, Gay R, Sokolovski S, Hills A, Lamattina L, Blatt MR (2003) Nitric oxide regulates K+ and Cl- channels in guard cells through a subset of abscisic acid-evoked signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 11116–11121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mata C, Lamattina L (2002) Nitric oxide and abscisic acid cross talk in guard cells. Plant Physiol 128: 790–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mata C, Lamattina L (2003) Abscisic acid, nitric oxide and stomatal closure - is nitrate reductase one of the missing links? Trends Plant Sci 8: 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mata C, Lamattina L (2010) Hydrogen sulphide, a novel gasotransmitter involved in guard cell signalling. New Phytol 188: 977–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabov A, Blatt MR (1998) Membrane voltage initiates Ca2+ waves and potentiates Ca2+ increases with abscisic acid in stomatal guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4778–4783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradmann D, Blatt MR, Thiel G (1993) Electrocoupling of ion transporters in plants. J Membr Biol 136: 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FI (2003) The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424: 901–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Wang L, Liu J, Hou L, Liu X (2013) Hydrogen sulfide regulates ethylene-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Integr Plant Biol 55: 277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Xue S, Luo Y, Tian B, Fang H, Li H, Pei Y (2013) Hydrogen sulfide interacting with abscisic acid in stomatal regulation responses to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem 62: 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabil O, Motl N, Banerjee R (2014) H2S and its role in redox signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1844: 1355–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt N, Vavasseur A, Forestier C (1999) ATP binding cassette modulators control abscisic acid-regulated slow anion channels in guard cells. Plant Cell 11: 1141–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lee YR, Assmann SM (1998) Guard cells possess a calcium-dependent protein kinase that phosphorylates the KAT1 potassium channel. Plant Physiol 116: 785–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lancaster JR (2013) Chemical foundations of hydrogen sulfide biology. Nitric Oxide 35: 21–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Ding XJ, Du PF (2013a) Hydrogen sulfide donor sodium hydrosulfide-improved heat tolerance in maize and involvement of proline. J Plant Physiol 170: 741–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Yang SZ, Long WB, Yang GX, Shen ZZ (2013b) Hydrogen sulphide may be a novel downstream signal molecule in nitric oxide-induced heat tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1564–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisjak M, Srivastava N, Teklic T, Civale L, Lewandowski K, Wilson I, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Hancock JT (2010) A novel hydrogen sulfide donor causes stomatal opening and reduces nitric oxide accumulation. Plant Physiol Biochem 48: 931–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisjak M, Teklić T, Wilson ID, Wood M, Whiteman M, Hancock JT (2011) Hydrogen sulfide effects on stomatal apertures. Plant Signal Behav 6: 1444–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michard E, Lacombe B, Porée F, Mueller-Roeber B, Sentenac H, Thibaud JB, Dreyer I (2005) A unique voltage sensor sensitizes the potassium channel AKT2 to phosphoregulation. J Gen Physiol 126: 605–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH (2009) H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal 2: ra72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Desikan R, Clarke A, Hancock JT (2002) Nitric oxide is a novel component of abscisic acid signaling in stomatal guard cells. Plant Physiol 128: 13–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega JA, Ortega JM, Julian D (2008) Hypotaurine and sulfhydryl-containing antioxidants reduce H2S toxicity in erythrocytes from a marine invertebrate. J Exp Biol 211: 3816–3825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C, Bauer CC, Boyle JP, Scragg JL, Dallas ML (2012) Modulation of ion channels by hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klüsener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI (2000) Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406: 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilot G, Gaymard F, Mouline K, Chérel I, Sentenac H (2003) Regulated expression of Arabidopsis shaker K+ channel genes involved in K+ uptake and distribution in the plant. Plant Mol Biol 51: 773–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffenstein RJ, Hulbert WC, Roth SH (1992) Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 32: 109–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemenschneider A, Nikiforova V, Hoefgen R, De Kok LJ, Papenbrock J (2005a) Impact of elevated H(2)S on metabolite levels, activity of enzymes and expression of genes involved in cysteine metabolism. Plant Physiol Biochem 43: 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemenschneider A, Wegele R, Schmidt A, Papenbrock J (2005b) Isolation and characterization of a D-cysteine desulfhydrase protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J 272: 1291–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Kwak JM, Allen GJ (2001) Guard cell abscisic acid signalling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature 410: 327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuffi D, Álvarez C, Laspina N, Gotor C, Lamattina L, García-Mata C (2014) Hydrogen sulfide generated by l-cysteine desulfhydrase acts upstream of nitric oxide to modulate abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. Plant Physiol 166: 2065–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, Xue S, Murata Y, Yang Y, Nishimura N, Wang A, Schroeder JI (2009) Calcium elevation-dependent and attenuated resting calcium-dependent abscisic acid induction of stomatal closure and abscisic acid-induced enhancement of calcium sensitivities of S-type anion and inward-rectifying K channels in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J 59: 207–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovski S, Blatt MR (2004) Nitric oxide block of outward-rectifying K+ channels indicates direct control by protein nitrosylation in guard cells. Plant Physiol 136: 4275–4284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovski S, Hills A, Gay R, Garcia-Mata C, Lamattina L, Blatt MR (2005) Protein phosphorylation is a prerequisite for intracellular Ca2+ release and ion channel control by nitric oxide and abscisic acid in guard cells. Plant J 43: 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter JU, Sieben C, Hartel A, Eisenach C, Thiel G, Blatt MR (2007) Abscisic acid triggers the endocytosis of the Arabidopsis KAT1 K+ channel and its recycling to the plasma membrane. Curr Biol 17: 1396–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Wu L, Wang R (2010) Interaction of hydrogen sulfide with ion channels. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37: 753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel G, Blatt MR (1994) Phosphatase antagonist okadaic acid inhibits steady-state K+ currents in guard cells of Vicia faba. Plant J 5: 727–733 [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. (2002) Two’s company, three’s a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J 16: 1792–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Blatt MR (2011) Anion channel sensitivity to cytosolic organic acids implicates a central role for oxaloacetate in integrating ion flux with metabolism in stomatal guard cells. Biochem J 439: 161–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Papanatsiou M, Eisenach C, Karnik R, Williams M, Hills A, Lew VL, Blatt MR (2012) Systems dynamic modelling of a guard cell Cl− channel mutant uncovers an emergent homeostatic network regulating stomatal transpiration. Plant Physiol 160: 1956–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M, Li L, Kostetski I, Chu SH, Siau JL, Bhatia M, Moore PK (2006) Evidence for the formation of a novel nitrosothiol from the gaseous mediators nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Yang G, Jia X, Wu L, Wang R (2005) Activation of KATP channels by H2S in rat insulin-secreting cells and the underlying mechanisms. J Physiol 569: 519–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hu LY, Hu KD, He YD, Wang SH, Luo JP (2008) Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination and alleviates oxidative damage against copper stress. J Integr Plant Biol 50: 1518–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Tang J, Liu XP, Wang Y, Yu W, Peng WY, Fang F, Ma DF, Wei ZJ, Hu LY (2009a) Hydrogen sulfide promotes root organogenesis in Ipomoea batatas, Salix matsudana and Glycine max. J Integr Plant Biol 51: 1086–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Ye YK, Wang SH, Luo JP, Tang J, Ma DF (2009b) Hydrogen sulfide counteracts chlorophyll loss in sweetpotato seedling leaves and alleviates oxidative damage against osmotic stress. Plant Growth Regul 58: 243–250 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R (2001) The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J 20: 6008–6016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]