Abstract

Although major advances have been made in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and solid organ transplantation in the last 50 years, big challenges remain. This Review outlines the current immunological limitations for HSCT and solid organ transplantation, and discusses new immune-modulating therapies in clinical trials and under pre-clinical development that may allow these obstacles to be overcome.

INTRODUCTION

Since the first successful allogeneic bone marrow and deceased-donor kidney transplants in the 1960s, the fields of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and solid organ transplantation have grown immensely. In the United States, over 21,000 patients per year receive solid organ transplants (Organ Transplant and Procedure Network 2014 Data, http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov) and another 7,000 patients undergo allogeneic HSCT (1). HSCT is a life-saving, curative treatment for a range of diseases, including hematological disorders and malignancies, immunodeficiencies, metabolic storage diseases, and certain extracellular matrix disorders such as the debilitating skin disease epidermolysis bullosa. Solid organ transplantation not only extends life in patients with organ failure, but it can improve quality of life, a feat difficult to achieve with other therapies. Unfortunately, serious immune reactions complicate both HSCT [graft-vs-host disease (GVHD)] and solid organ transplantation (graft rejection). Although broadly immunosuppressive agents can help to control these events, immunosuppression confers additional complications, such as opportunistic infections and an increased incidence of a variety of conditions including malignancy, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Thus, big challenges remain in the field of transplantation. Here we outline the current immunological limitations for both HSCT and solid organ transplantation, and discuss new immune-modulating therapies that may enable these barriers to be overcome.

Current Immunological Challenges

The primary immunological barrier to allogeneic HSCT efficacy is GVHD. With a fatality rate of nearly 20%, GVHD is the second leading cause of death in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, behind only mortality from primary disease (1). Acute GVHD occurs in 20–70% of patients (2), and chronic GVHD, the primary long-term cause of morbidity after allogeneic HSCT, can affect >50% of patients (3). Both acute and chronic GVHD result from the transfer of alloreactive donor T cells within the stem cell graft, but their pathogenesis (Figure 1A, B) and clinical features are distinct. Acute GVHD has a strong inflammatory component, with robust T cell activation and proliferation causing immune-mediated destruction of recipient organs, in particular the skin, gastrointestinal (GI) tract and liver (4). Chronic GVHD displays more autoimmune and fibrotic features, with donor T cells interacting with bone marrow-derived B cells along with recipient macrophages and fibroblasts to cause widespread antibody deposition and tissue fibrosis (5). Yet, despite our increased understanding of GVHD pathogenesis, current GVHD prophylaxis and treatment approaches are primarily based on the use of non-specific immunosuppressive drugs such as calcineurin inhibitors, rapamycin, mycophenolate mofetil, steroids, and anti-T cell antibodies (6). Additionally, whereas rigorous donor T cell depletion can avert GVHD, the immediate consequences of pan-T cell removal are similar to global immune suppression, that is, increased risk of infection and tumor recurrence.

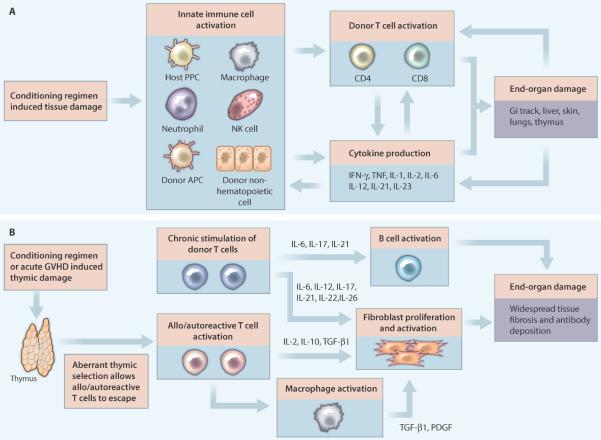

Figure 1. The pathophysiology and initiating factors involved in GVHD after HSC transplant.

Shown are the immune processes and molecules involved in the development of (A) acute or (B) chronic GVHD after HSCT. (A) Acute GVHD begins with a conditioning regimen such as chemotherapy combined with total body irradiation that induces tissue damage. This tissue damage causes the release of danger signals, such as cytokines and chemokines, which activate recipient innate immune cells, including antigen presenting cells (APCs). Donor APCs, which are a component of the stem cell graft, are also activated by this highly inflammatory milieu. A combination of donor and recipient APCs then activate donor CD4 and CD8 T cells. Cytokine production and direct cytolysis of host cells by these T cells, as well as by host macrophages, neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells, causes end-organ damage. The resulting tissue destruction further amplifies acute GVHD, creating a positive-feedback loop that can be difficult to stop, even with immunosuppressive drug treatment. (B) Thymic destruction, either from pre-transplant conditioning or acute GVHD, and chronic stimulation of donor T cells contribute to chronic GVHD after HSCT. Thymic damage alters the selection of T cells, which can result in the release of lymphocytes that react to host tissues. Depending upon the antigen, this reaction to host can be considered allo- or auto-reactive. Once activated, these T cells stimulate fibroblast proliferation and macrophage activation, both of which result in tissue fibrosis. Donor T cells also contribute to fibroblast activation, and play a key role in activating B cells, which produce antibodies with specificities for host tissues. All of these events contribute to the highly fibrotic syndrome of chronic GVHD.

With improvements in surgical techniques and ancillary care over the past several decades, graft rejection is now the primary limitation for solid organ transplantation. Although the incidence varies by the type of graft, rejection plays a major role in loss of graft function over time. Rejection has three forms: hyperacute, acute and chronic. Hyperacute rejection occurs within hours after transplantation and is mediated by preformed complement fixing antibodies (typically directed against donor MHC class I antigens) that activate complement and coagulation cascades and mediate rapid destruction of the graft (7). The discovery of the basis for hyperacute rejection, and the introduction of cross-matching to detect anti-donor antibodies pre-transplant has virtually eliminated the occurrence of hyperacute rejection in solid organ transplantation (8). Acute rejection typically manifests weeks to months after transplantation and is mediated by recipient alloreactive T cells, which destroy the donor graft through both direct cytolysis and activation of innate immune cells (9) (Figure 2A). In addition, a subset of activated T cells can provide help for B cell antibody class switching, affinity maturation, and ultimately the production of donor-specific antibodies. Development of donor-specific antibodies after transplantation plays a limited role in most instances of acute rejection with the exception of some of the most severe cases. However, these antibodies have been implicated in chronic rejection (10) (Figure 2B), which manifests months to years after transplantation. Chronic rejection likely involves both non-immune mediated and immune mediated processes (11), in particular, donor-specific antibody deposition that directs innate immune cell activation and graft injury. The primary prophylaxis and treatment strategies for addressing solid organ transplantation rejection are similar to those for GVHD, comprising non-specific immunosuppressant drugs.

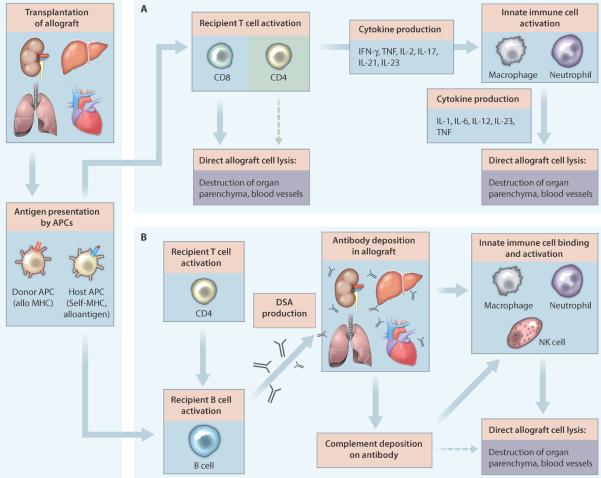

Figure 2. The pathophysiology and initiating factors involved in rejection of solid organ transplants.

Shown are the factors involved in the development of (A) acute and (B) chronic rejection of solid organ transplants. (A) The process of acute allograft rejection begins with recipient CD4 and CD8 T cells becoming activated through interactions with donor and recipient antigen presenting cells (APCs) (respectively termed direct and indirect allorecognition). After activation, CD8 T cells, and to a lesser extent CD4 T cells, directly destroy both graft blood vessels and parenchyma. Recipient CD4 T cells primarily contribute to acute rejection by producing a variety of cytokines that activate macrophages and neutrophils. These innate cells then attack and lyse graft cells. The combination of lymphocyte and innate cell directed graft destruction results in allograft dysfunction and acute rejection. (B) In chronic allograft rejection, CD4 T cells help to induce antibody class switching, affinity maturation, and ultimately the production of donor-specific antibodies (DSA) by recipient B cells. Binding of donor-specific antibodies to graft cells enhances neutrophil, macrophage and NK cell-mediated destruction of the graft (via Fc receptor binding) and results in complement deposition. Subsequent activation of the complement cascade results in direct lysis of graft cells via the complement membrane attack complex and further augments innate cell recognition and destruction of the graft. Although this process evolves over months to years, it results in chronic allograft dysfunction and eventual complete rejection. PDGF, platelet derived growth factor.

Although GVHD and solid organ transplantation rejection are distinct clinical entities, they share many features, including key steps in pathogenesis and limitations of current therapies. In this light, the following sections highlight promising new targeted immunotherapies specific for each condition, as well as treatments that may be efficacious in both GVHD and solid organ transplantation rejection (Figure 3; Table 1). Whereas we present primarily positive data for the therapies discussed below, many have significant risks or adverse effects. We have highlighted some of these risks, but a comprehensive discussion of each therapy is beyond the scope of this Review. In addition, all of these therapeutics will need rigorous large-scale clinical trial testing in order to assess fully their potential benefits, side effects and drawbacks. When discussing solid organ transplantation research and clinical trials we primarily focus on kidney transplantation because in the United States >50% of patients undergoing solid organ transplantation receive kidney allografts (http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov) and the majority of new translational therapies first enter the clinic in this area.

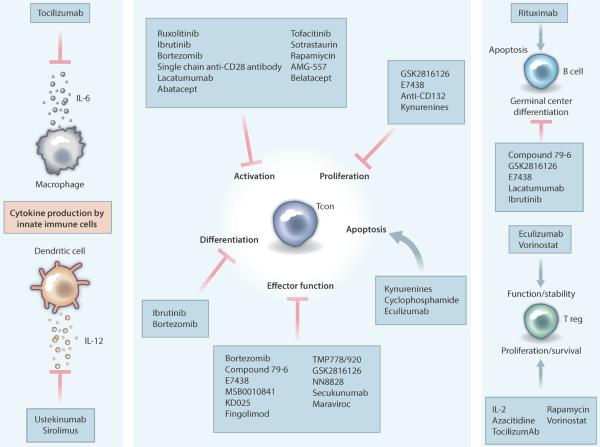

Figure 3. Mechanisms of action for promising immunomodulatory therapies.

Shown are known mechanisms by which new agents alter critical aspects of the pathogenesis of GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection. The majority of these therapies focus on inhibiting various functions of conventional T cells, which are the primary drivers of many aspects of GVHD and allograft rejection. Abatacept, belatacept: CTLA-4Ig fusion protein inhibitors of CD80/86; azacitidine, DNA hypomethylating agent; sotrastaurin, pan-PKC inhibitor with preferential selectivity for PKC-theta; anti-CD132, anti-IL-2 common gamma chain (CD132) mAb; AMG557, anti- ICOS/B7RP1 mAb; bortezomib, proteasome inhibitor; compound 79-6, Bcl-6 inhibitor; cyclophosphamide, DNA alkylating agent; E7438, EZH2 methyltransferase inhibitor; eculizumab, complement inhibitor; fingolimod, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor inhibitor; GSK2816126, an EZH2 methyltransferase inhibitor; ibrutinib, BTK/ITK inhibitor; KD025, ROCK2 inhibitor; kynurenines, products of L-tryptophan catabolism; lucatumumab, anti-CD40 mAb; maraviroc, CCR5 antagonist; MSB0010841, anti-IL-17A/F nanobody; NN8828, anti-IL-21 mAb; rapamycin, mTOR inhibitor; rituximab, anti-CD20 mAb; ruxolitinib, JAK1/2 inhibitor; single-chain anti-CD28 antibody, anti-CD28 mAb; TMP778, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma-t (RORgt) antagonist; TMP920, RORgt antagonist; tocilizumab, anti-IL-6R mAb; tofacitinib, JAK3 inhibitor; ustekinumab, anti-IL-12/23 mAb; vorinostat/suberanilohydroxamic acid, HDAC inhibitor. HDAC, histone deacetylase; Tcon, conventional T cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Table 1.

New approaches for the prevention or treatment of GVHD and/or SOT rejection

| Category | Therapy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing inflammatory cytokines | Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6R mAb |

| Ustekinumab | Anti-IL-12/23mAb | |

| NN8828 | Anti-IL-21 mAb | |

| MSB0010841 | Anti-IL-17 A/F nanobody | |

| Secukunumab | Anti-IL-17 AmAb | |

| Altering immune cell trafficking | Maraviroc | CCR5 small molecule inhibitor |

| Fingolimod | S1P receptor modulator | |

| Inhibition of T and B cell signaling | Ruxolitinib | JAK1/2 small molecule inhibitor |

| Tofacitinib | JAK3 small molecule inhibitor | |

| Ibrutinib | ITK/BTK small molecule inhibitor | |

| Sotrastaurin | PKC- small molecule inhibitor | |

| KD025 | ROCK2 small molecule inhibitor | |

| TMP778, TMP920 | RORγ small molecule inhibitors | |

| B cell depletion | Rituximab | Anti-CD20 mAb |

| Preferential in vivo expansion of regulatory T cells | Rapamycin (+IL-2) | mTOR small molecule inhibitor |

| Azacitidine (+IL-2) | DNA-hypomethylating agent | |

| IL-2 | Anti-apoptotic, proliferative cytokine | |

| Vorinostat | HDAC small molecule inhibitor | |

| Cyclophosphamide | DNA alkylating agent | |

| Cellular Therapies | Regulatory T-cells | CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Suppressive T cell |

| Tr1 Cells | CD4+Lag3+CD49b+Suppressive T cell | |

| MSCs | Suppressive stem cell population | |

| Regulatory macrophages | Suppressive macrophages | |

| Regulatory DCs | Suppressive dendritic cells | |

| Stem cell transplant with solid organ transplant | Chimerism to induce tolerance | |

| Inhibition of T cell costimulation | Abatacept | CTLA-4lg fusion protein |

| Belatacept | CTLA-4lg fusion protein | |

| Single chain CD28 Antibody | Anti-CD28 mAb | |

| Lacatumumab | Anti-CD40 mAb | |

| AMG-557 | Anti-ICOS-LmAb | |

| Complement Inhibition | Eculizumab | Anti-C5a mAb |

| Targeting metabolic pathways | Kynurenine infusion | Tryptophan metabolite |

| TLR7/8 Agonist | Enhances kynurenine production by APCs | |

| Blocking GC formation | Compound 79–6 | Bcl-6 small molecule inhibitor |

| GSK2816126 | EZH2 small molecule inhibitor | |

| E7438 | EZH2 small molecule inhibitor | |

| Other | Bortezomib | Proteasome small molecule inhibitor |

IL, Interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; CCR5, chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; JAK, Janus activated kinases; ITK, interleukin-2–inducible kinase; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; PKC- , Protein kinase C – ; ROCK2, rho-associated kinase 2; RORγ, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; Tr1, Type 1 regulatory cells; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; DC, dendritic cell; CTLA-4lg, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4-lgG1 fusion protein; ICOS, inducible costimulator; C5a, activated complement protein 5; TLR, toll-like receptor; Bcl-6, B cell lymphoma-6; APC, antigen presenting cell; GC, germinal center.

NEW THERAPIES IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection has led to the development of new immunomodulatory approaches, and many of these have been translated from pre-clinical models into clinical trials. A number of these therapies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for other conditions, enhancing their translational potential. Below we identify crucial mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of both GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection and discuss some of the most interesting and promising treatment approaches that are being tested in the clinic.

Ongoing Clinical Trials

Reducing inflammatory cytokines

The cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays a role in the early inflammatory reactions of both acute GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection (12–14), and as such represents a common target for both diseases. In mouse studies, inhibition of IL-6 signaling with an anti-IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) monoclonal antibody (mAb) reduced GVHD (15). Additionally, testing of tocilizumab--- a humanized anti-IL-6R mAb approved by the FDA for rheumatoid arthritis--- in addition to a standard GVHD prophylactic regimen in a cohort of HSCT patients demonstrated a reduction in acute GVHD incidence compared to patients given standard GVHD prophylaxis alone, without affecting immune reconstitution, infectious immunity or tumor recurrence (16). However, it should be noted that rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab have increased susceptibility to infections, as well as some instances of neutropenia (17), meaning that careful monitoring for both of these potential side effects will be required in further clinical trials. In solid organ transplantation, IL-6 modulation also represents a potential therapeutic strategy, and could have additional benefits beyond reducing inflammation because IL-6 plays a role in ischemia-reperfusion injury and antibody-mediated injury (18). Tocilizumab is now being investigated in two clinical trials for kidney transplant (NCT01594424, NCT02108600).

Critical to the pathogenesis of both acute and chronic GVHD is the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In particular, two members of the IL-12 cytokine family, IL-12 and IL-23, have been shown to play key roles in GVHD initiation. In mouse studies, blockade of IL-12 and IL-23 reduced acute GVHD while still maintaining the graft-versus-tumor (GVT) response of donor T cells (19, 20). Ustekinumab, a humanized mAb approved by the FDA for treating plaque psoriasis, inhibits both IL-12 and IL-23. As a result of the success with IL-12 and IL-23 blockade in pre-clinical and phase I studies, ustekinumab is now in phase II clinical testing for GVHD prophylaxis (NCT01713400). Although results have not been reported for the clinical trial, ustekinumab did have efficacy in a cohort of patients with steroid-refractory GVHD (21). Whereas psoriasis patients taking ustekinumab have an increased risk of minor infections (22), there did not appear to be a higher incidence of infections in these steroid-refractory patients.

Altering immune cell trafficking

One of the most critical steps in GVHD pathogenesis is the recruitment of activated T cells to target organs. Chemokine-chemokine receptor interactions mediate much of this migration (5) and chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5) has been shown to be a key mediator of T cell trafficking to GVHD target organs, especially the GI tract (23, 24). CCR5 expression on donor graft dendritic cells (DCs) also correlates with greater incidence and higher grade GVHD in patients after allogeneic HSCT (25), indicating that CCR5 may also regulate donor DC activation and migration in GVHD. A recently completed phase I/II clinical trial with the CCR5 inhibitor maraviroc (NCT00948753), which is FDA approved as an HIV antiretroviral, demonstrated a reduction in GVHD, primarily as a result of reduced GI tract involvement (26). However, different conditioning regimens in a mouse model altered the efficacy of CCR5 inhibition (27), indicating that further assessment of maraviroc will need to take into account the type of conditioning a patient receives. Additional insight about the efficacy of this drug will be gleaned from the three ongoing clinical trials using maraviroc to prevent acute GVHD (NCT01785810, NCT02208037, NCT02167451).

Inhibition of T and B cell signaling

Activated T cells play a major role in the pathogenesis of both GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection, with B cells critically involved in chronic GVHD progression (5) and chronic allograft rejection (28). Inhibition of T cell function has long been a strategy for treating GVHD and preventing solid organ transplant rejection, but several new agents that target either T cells, or both T and B cells, are currently being tested.

Janus Activated Kinases (JAKs) are required for T cell activation and differentiation in response to inflammatory cytokines. In particular, JAK1 and JAK2 are critical in GVHD initiation (29), making them attractive therapeutic targets for early abrogation of GVHD. Ruxolitinib, a selective JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treating myelofibrosis, was recently shown to be efficacious in treating GVHD in mice (30). In addition, a subset of patients with steroid-refractory GVHD responded well to ruxolitinib and had no adverse events as a result of therapy (30). These clinical data, along with our unpublished results of ongoing studies, suggest that ruxolitinib may be useful in GVHD. Although worsening anemia and thrombocytopenia have been seen in myelofibrosis patients on ruxolitinib (31), the early results from treating steroid-refractory GVHD patients would suggest that these effects may not be as prominent in the HSCT setting. Further assessment of these potential side effects in HSCT patients is required to understand fully the potential drawbacks of this therapy.

Inhibiting JAK3 signaling reduces mouse T cell proliferation and GVHD lethality in a mouse model (32) suggesting that JAK3 may be a target for GVHD prevention or therapy in the clinic. JAK3 has also been shown to be important for rejection of solid organ transplants. Tofacitinib, a relatively selective JAK3 inhibitor currently FDA-approved for rheumatoid arthritis, was found to inhibit renal transplant rejection in cynomolgus monkeys (33) and to have additive effects with mycophenolate mofetil (34), which is commonly used for prophylaxis of transplant rejection. In phase I/II clinical trials using tofacitinib for renal transplantation (35, 36), a high incidence of infectious complications has been observed. This suggests that whereas this drug holds promise for preventing rejection of solid organ allografts, the ideal patient profiles and concurrent immunosuppressive regimens have not yet been elucidated.

Two members of the tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (TEC) family of kinases, interleukin-2–inducible kinase (ITK) and Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), share close homology and play critical roles in both T and B cell function. ITK helps to drive T cell activation as well as the differentiation of CD4 T helper cell subsets, and BTK is essential for B cell receptor (BCR) signaling (37, 38). In mouse studies, treatment with ibrutinib, an ITK and BTK inhibitor that is FDA-approved for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), reversed lung pathology and pulmonary dysfunction in mice with established chronic GVHD in a model dependent upon cooperation between T-follicular helper cells (Tfh) and germinal center B cells; additionally, ibrutinib reduced the progression of sclerodermatous chronic GVHD in mice (39). Further testing in mice established that ibrutinib does not adversely affect clearance of intracellular pathogens, suggesting that ibrutinib may be efficacious in GVHD without increasing infection risk (40). However, there is some evidence in CLL patients that ibrutinib may cause anemia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia (41); assessment of these cytopenias will be critical in HSCT patients. An ongoing phase I/II clinical trial (NCT02195869) is evaluating ibrutinib in patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory chronic GVHD.

Protein kinase C

Activation of phospholipase C following T cell receptor and CD28 ligation results in the generation of the second messenger diacylglycerol, which in turn activates the theta isoform of protein kinase C (PKC-θ). In a randomized phase II trial, the PKC-θ inhibitor sotrastaurin was shown to be comparable to mycophenolate mofetil when used as part of a standard tacrolimus (calcineurin inhibitor)-based regimen for immunosuppression in renal transplantation (42). Further results from completed studies are not yet available. Sotrastaurin is currently being explored in GVHD as well. Pre-clinical results with mice suggest that administration of sotrastaurin prevents GVHD while maintaining GVT (43). In combination with the results with sotrastaurin for kidney transplant, there may be translational potential for this small molecule in GVHD.

B cell depletion

Given the critical role that antibodies play in chronic GVHD (44), depletion of B cells using the FDA-approved anti-CD20 mAb rituximab is a potentially attractive therapeutic option. In mice, a highly depletionary anti-CD20 mAb was effective in preventing chronic GVHD when used as a prophylactic agent, but showed less than optimal therapeutic benefit in reversing established chronic GVHD (45). Two phase I/II clinical trials have reported that rituximab has efficacy in preventing chronic GVHD (46, 47), although there was an increased susceptibility to infections. Nevertheless, these pre-clinical and early clinical trial data indicate that rituximab may be an effective prophylactic agent and a variety of additional clinical trials are assessing rituximab's long-term efficacy in chronic GVHD.

Rituximab also has been shown to be effective as part of a desensitization protocol in renal transplantation where recipients have pre-formed anti-HLA antibodies (48). Smaller studies have used rituximab as prophylaxis or treatment for acute graft rejection, or as a treatment for chronic antibody-mediated rejection, but due to their size, these studies are not conclusive.

Other strategies

The proteasome, the cellular organelle that disposes of misfolded proteins, is required for the maintenance and regulation of basic cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (49). Pre-clinical mouse work with the FDA-approved proteasome inhibitor bortezomib demonstrated that it is a potent inhibitor of alloreactive T cells, and that bortezomib treatment reduced acute GVHD without affecting GVT (50, 51). In addition, one of the mechanisms by which bortezomib reduced GVHD severity was by diminishing production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (discussed above). In chronic GVHD, pre-clinical mouse studies and early clinical trial results show clinical efficacy with bortezomib treatment (52, 53). Importantly, some patients treated with bortezomib were able to taper steroid doses, a significant achievement for patients who were steroid-dependent. Clinical trials are evaluating the long-term efficacy of bortezomib for treating GVHD.

Bortezomib has been considered in solid organ transplantation as well, with many single patient reports or small scale trials in the literature, although a study of four treated patients showed that bortezomib was not effective as a single agent in reducing production of donor-specific antibodies (54). The BORTEJECT study (NCT01873157), the only trial currently recruiting patients to test bortezomib in solid organ transplantation, is designed to determine if this modality can be used to treat chronic antibody-mediated renal transplant rejection.

Preferential in vivo expansion of regulatory T cells

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are CD4+25+FoxP3+ suppressor cells that are critical mediators of peripheral tolerance (55). A reduced ratio of Tregs to T conventional cells (Tcon) (Treg<Tcon) is associated with the development of chronic GVHD in allogeneic HSCT patients; low dose IL-2 therapy reduces chronic GVHD by preferentially expanding Tregs during the IL-2 administration time period (56). For chronic GVHD, such in vivo Treg expansion is an attractive means to tip the Treg:Tcon ratio in favor of tolerance. Several ongoing clinical trials are building upon the success with low dose IL-2 treatment for chronic GVHD. In particular, two trials are combining drugs that favor Tregs vs Tcon with low dose IL-2 in order to further enhance Treg expansion. The first trial (NCT01927120) pairs rapamycin (sirolimus) with IL-2 and tacrolimus to prevent acute GVHD. Sirolimus is an FDA-approved mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor that has been shown to prevent GVHD by restricting Tcon proliferation while also permitting preferential expansion of Tregs (57). The addition of sirolimus to IL-2 and tacrolimus has the potential to limit Tcon responses while supporting IL-2 driven Treg proliferation, which could further enhance Treg-mediated GVHD prevention. A second trial (NCT01453140) combines IL-2 and sirolimus with the DNA-hypomethylating agent azacitidine for treating steroid-refractory acute GVHD, with or without cyclophosphamide, which is used to deplete alloreactive Tcon but not Tregs (see below). Azacitidine favors Tregs versus Tcon, which could be beneficial for GVHD prevention, and in one phase I trial it also was shown to enhance GVT (58, 59). Given its potential to augment GVT while expanding Tregs, azacitidine may prove to be an effective GVHD therapeutic. While it appears that the addition of sirolimus ± azacitidine to low dose IL-2 (and other agents) could further augment Treg numbers in vivo, it remains to be seen whether this Treg expansion will reduce GVHD without sacrificing long-term infectious immunity or GVT. Similar concepts regarding in vivo expansion of endogenous Tregs using IL-2 alone or in combination with sirolimus have been proposed for solid organ transplantation. A single clinical trial of IL-2 in patients receiving tissue allografts consisting of skin, subcutaneous, neuromuscular, and vascular tissue (vascularized composite tissue allografts) is currently underway (NCT01853111).

Epigenetic modification of the Foxp3 locus and other loci is critically important in the development and maintenance of Tregs (60). In keeping with this, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors are effective therapeutics in animal models of solid organ and tissue transplantation (61). In a phase I/II study, the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat reduced acute GVHD incidence when paired with mycophenolate motefil and tacrolimus (62) by increasing the number and suppressive function of Tregs (63).

Cyclophosphamide, an alkylating agent FDA-approved for a variety of malignancies and autoimmune diseases, has been shown to preferentially deplete alloreactive Tcon while sparing Tregs (64). As a result, several phase I/II studies have examined post-transplant cyclophosphamide as a means to reduce GVHD. These trials revealed that even short courses of cyclophosphamide after HSCT can reduce GVHD, with particular efficacy in preventing chronic GVHD (65, 66). This indicates that this strategy may merit further clinical testing in GVHD and potentially solid organ transplantation as well.

Cell-based therapies

In addition to targeted drugs, cell-based therapies represent another potentially successful intervention for preventing GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection. Several distinct types of immunosuppressive cells are currently under investigation in clinical trials.

A large body of pre-clinical data have demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of Tregs can prevent solid organ transplant rejection and acute GVHD (67–69), and this has provided the impetus for ongoing and planned clinical trials. In solid organ transplantation, some studies utilize ex vivo unselected Tregs (NCT02129881, NCT02088931), whereas others focus on recipient Tregs that have been expanded using donor-derived antigen (NCT02091232, NCT02188719, NCT02244801). Interestingly, the approach to develop antigen-specific Tregs used in the NCT02091232 trial, that is, culturing recipient T cells with donor antigen in the presence of CTLA-4Ig (to block CD28:B7 costimulation), is derived from a series of early phase trials for GVHD prophylaxis using donor bone-marrow pre-cultured with recipient antigen-presenting cells (APCs) plus CTLA-4Ig (70, 71). Treg studies in solid organ transplantation are still focusing on safety; whether Tregs may be most effective in preventing or treating rejection, or whether they allow for a reduction in conventional immunosuppression, awaits further determination.

In GVHD, a recent first-in-human phase I clinical trial using umbilical cord blood-derived Tregs showed that third-party ex vivo expanded Treg infusions were well tolerated and reduced grade II-IV acute GVHD (72). A phase II trial using freshly purified Tregs also showed that Treg infusions were efficacious in preventing GVHD in the haploidentical HSCT setting (73). As a result of these phase I and II successes, a variety of trials are now investigating ex vivo expanded or freshly purified Treg infusions as a means to prevent both acute and chronic GVHD. Importantly, these new trials are also assessing the efficacy of Tregs derived from multiple sources, with the goal of understanding which populations are most efficacious and easier to generate in large numbers.

Type 1 T-Regulatory (Tr1) cells are a suppressive subset of CD4 T cells that express CD49b and Lag3 and can be generated by and produce IL-10 (74). Tr1 cells play a role in peripheral tolerance but are distinct from Foxp3+ Tregs. Although Tr1 cells have only recently been investigated as a therapeutic, in four haploidentical HSCT patients treated with infusions of Tr1 cells shortly after transplant, immune reconstitution was enhanced compared to historical controls who had undergone haploidentical HSCT, no GVHD occurred and no long-term immunosuppression was required (75). Studies to examine these cells in solid organ transplantation are just being initiated.

In addition to Tregs and Tr1 cells, other cell types with immunomodulatory properties are being studied. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are being explored as a therapeutic for treating both HSCT and solid organ transplant rejection. MSCs are multi-potent adult stem cells that can suppress immune responses, repair tissues and stimulate hematopoiesis (76). As MSCs can be derived from a variety of tissues, they represent a potentially autologous or off-the-shelf third party source of immunosuppressive cells that can be generated in large numbers, and thus are an attractive cell-based therapeutic. To date, third-party MSCs have been used in tandem with front-line immunosuppressant drugs to treat GVHD with minimal side effects and some encouraging clinical results (77–79). However, primary endpoint reporting from a phase III trial (NCT00366145) using an industry-produced MSC product showed that these MSCs failed to increase complete responses in patients with steroid-resistant GVHD (80). Whereas full results from this trial have yet to be published, the mix of positive and negative results with MSCs in GVHD underscores the potential need to identify specific subsets of patients that may benefit from this therapy. In solid organ transplantation, both live autologous and irradiated donor MSCs are being investigated. In the latter instance, such cells may be immunomodulatory and may also provide an ongoing source (in the case of repeated administration) of systemic donor antigen. Further testing of MSCs from a variety of sources is currently ongoing.

Regulatory macrophages have been utilized in renal transplantation (81) and are the focus of further ongoing clinical studies (NCT02085629). Autologous regulatory DCs, typically immature DCs or cells cultured in the presence of rapamycin, have been tested in a variety of pre-clinical HSCT and solid organ transplant mouse models (82–84) and are just now being introduced into the clinic for solid organ transplantation (NCT02252055).

Stem cell transplantation

Over three decades ago, hematopoietic chimerism was shown to convey donor-specific organ and tissue transplantation tolerance (85). Since then, extensive pre-clinical studies have led to the development of several clinical trials to refine this approach. Two current protocols utilize non-myeloablative HSCT to create transient mixed hematopoietic chimerism. In the most extensive data set with patients given HLA-mismatched kidneys, 7 of 10 patients achieved excellent stable renal function and were able to discontinue immunosuppressive drugs for at least five years (86). Another approach using an infusion of a proprietary product of CD8+, T cell receptor (TCR) negative cells, termed graft facilitating cells, along with non-myeloablative conditioning and HSCT, successfully achieved durable chimerism in some patients after HLA-mismatched kidney transplantation (87). Whereas follow-up is still limited in many patients, positive results have been achieved, and interestingly GVHD has not been problematic, perhaps because of the use of a cell product in the infusion or because the high-dose cyclophosphamide regimen spared Tregs (64). At present, these conceptually attractive strategies still await large-scale clinical trials to delineate the optimal approaches, and to determine whether they produce superior results compared with other regimens that achieve minimization (although not discontinuation) of immunosuppressive drug treatment.

On the Horizon

In this section, we identify new therapeutics that are showing promise in pre-clinical testing, but have yet to be translated into the clinic.

Reducing inflammatory cytokines

The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-21, a member of the IL-2 common gamma chain family of cytokines, has been shown to promote both acute and chronic GVHD (5). In mouse studies, inhibition of IL-21 reduced acute and chronic GVHD mortality and severity (88, 89). Although IL-21 inhibition has yet to be brought to the clinic for GVHD, a humanized anti-IL-21 mAb (NN8828, Novo Nordisk) was recently tested in several phase I/II clinical trials as a therapeutic for autoimmune inflammatory conditions (NCT01208506, NCT01565408, NCT01751152, NCT01647451), enhancing the translational potential of anti-IL-21 therapy for GVHD.

In addition to IL-21, several other common gamma chain cytokines (IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15) play critical roles in acute and chronic GVHD pathogenesis. Using a mAb against the IL-2 common gamma chain (CD132) in mice reduced acute GVHD and reversed established chronic GVHD (32). These initial pre-clinical data indicate that CD132 may be a useful therapeutic target in GVHD. However, it is as yet unclear how inhibiting such a critical cytokine pathway would affect infectious immunity or GVT, although mouse studies with anti-CD132 mAb in acute GVHD showed retention of GVT in that model system (32).

T-helper 17 (Th17) skewed CD4 T cells produce both IL-21 and IL-17, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that works in tandem with IL-21 to mediate acute and chronic GVHD. The production of both cytokines by Th17 cells requires rho-associated kinase 2 (ROCK2), a molecule linked to a variety of fibrotic diseases, including some with features similar to highly fibrotic chronic GVHD (90, 91). The selective ROCK2 inhibitor KD025 was successful in treating mouse collagen induced arthritis (92), and is currently in clinical trials for psoriasis (NCT02106195). Given that both IL-17 and IL-21 play critical roles in acute and chronic GVHD pathogenesis, ROCK2 inhibition may prove to be a successful, translatable strategy for GVHD prevention. Alternatively, strategies that seek to neutralize IL-17A [currently being tested in autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis (MSB0010841, anti-IL17 A/F nanobody) and inflammatory bowel disease (Secukunumab, anti-IL17A mAb)] or that use RORγ inhibitors (93) to target Th17 cells may be useful in GVHD and solid organ transplantation settings.

Altering immune cell trafficking

Migration of T cells from secondary lymphoid organs to inflamed tissues is critical for nearly all immune responses. The interaction between sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptor helps to mediate T cell emigration from secondary lymphoid organs, a step required for activated T cells to migrate to inflamed tissues. Fingolimod, which is FDA-approved for multiple sclerosis, is a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator that prevents T cell emigration from secondary lymphoid organs resulting in reduced numbers of activated T cells in inflamed tissues (94). In mouse GVHD testing, fingolimod decreased acute GVHD mortality without affecting the GVT response (95), but somewhat unexpectedly, this reduced mortality was not mediated by a reduction in activated T cells in target tissues (96). Rather, fingolimod reduced the number of splenic DCs and activated T cells early after transplant, indicating that fingolimod may have additional mechanisms of action. Regardless of its exact effect, fingolimod remains a candidate for GVHD prevention or treatment. In contrast to its potential for future development in GVHD, in renal transplantation, fingolimod did not display superior efficacy to mycophenolate mofetil in a phase III clinical trial (97), and thus its developmental path in solid organ transplantation remains uncertain.

Inhibition of T cell costimulation:CD28:B7 ligands

Early mouse studies demonstrated the efficacy of a soluble form of CTLA-4 (the inhibitory homolog of CD28) linked to an IgG1 fusion partner (CTLA-4Ig) to block CD28/CTLA-4:B7 ligand interactions, prolong solid organ graft acceptance (98), and reduce GVHD (99). The likely mechanism of action of CTLA-4Ig is to bind to CD80 and CD86 with a higher affinity than CD28, thus preventing CD28-mediated costimulation. Abatacept, a humanized CTLA-4Ig fusion protein, is FDA-approved for treating autoimmune arthritis. A trial of abatacept for GVHD prevention demonstrated a low incidence of acute GVHD (100), and as a result, abatacept is being tested in two additional phase I and II trials (NCT01954979, NCT01743131). Belatacept, a modified version of CTLA-4Ig, is FDA-approved for use as prophylaxis for rejection in renal transplantation. However, both abatacept and belatacept have the undesired effect of inhibiting endogenous CTLA-4 from binding to CD80 and CD86, thus interrupting a normal negative immunoregulatory signal. One means to circumvent this would be using agents that directly block CD28. Single-chain antibodies that block CD28 without binding to CTLA-4 were first described over a decade ago and their subsequent development has led to a better understanding of how to develop highly specific antibodies (101). These antibodies have been used successfully in a number of non-human primate models of renal transplantation (102) and seem likely to be developed for clinical use in solid organ transplantation in the near future. An inhibitory anti-CD28 antibody also was recently shown to reduce human to mouse xenogeneic GVHD (102), indicating that CD28 blockade could be beneficial in this setting as well.

Inhibition of T cell costimulation: CD154

Blockade of CD40:CD154 interactions has been shown to prevent T and B cell mediated alloimmune responses in many animal models. Anti-CD154 mAb showed great promise in non-human primate studies of renal transplantation and mouse GVHD models, but clinical trials of the initial anti-CD154 mAb were halted due to thrombotic complications (103). Given these complications, new anti-CD154 therapies, as well as anti-CD40 mAbs are currently being explored in non-human primate and mouse models (104, 105). Of note, translation of anti-CD40 therapies may be bolstered by lucatumumab, an anti-CD40 mAb currently in phase I testing for follicular lymphoma (NCT01275209). However, it remains to be seen whether these new therapies are devoid of the thrombotic complications in humans that hindered the initial anti-CD154 mAb.

Inhibition of T cell costimulation: ICOS

Inhibition of the inducible costimulator (ICOS) pathway with anti-ICOS antibodies reduced germinal center formation (where T and B cells cooperate to generate class switched antibodies and induce affinity maturation) and chronic GVHD in mouse studies using models in which disease induction is dependent on antibody secretion and tissue deposition (89). The humanized anti-ICOS-L mAb AMG-557 is currently in clinical trial testing for lupus (NCT01683695, NCT00774943), enhancing the translational potential of anti-ICOS/ICOS-L therapeutics for potential treatment of both chronic GVHD and chronic solid organ allograft rejection.

Complement inhibition

Complement proteins represent the humoral arm of the innate immune system and play a role in modulating innate and adaptive immunity. Complement proteins C3a and C5a diminish Treg function (106), and reduce T cell apoptosis (107). In mouse GVHD studies, pharmacological blockade of C3a/C5a signaling limited acute GVHD by promoting Treg stability (106). In solid organ transplant rejection, C5a seems to play a role in both T cell activation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. In a preliminary report, the anti-C5a mAb eculizumab, FDA-approved for use in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, was shown to be effective in preventing antibody-mediated damage in renal transplantation(108). It is being studied further in solid organ transplantation to prevent ischemia/reperfusion injury through a number of ongoing clinical trials.

Targeting metabolic pathways

Indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenines, metabolites that inhibit proliferation of alloreactive T cells. Mouse studies showed that IDO expression and kynurenine production by APCs plays a critical role in dampening GVHD (109). Both infusions of exogenous kynurenines and stimulation of kynurenine production by APCs through toll-like receptors 7 and 8 (TLR7/8) agonism reduced acute GVHD (109). In addition, IDO expression in DCs can induce a highly suppressive subset of Tregs, further potentiating the suppressive effect of IDO expression (110). Together, these data indicate that augmented IDO and kynurenine signaling, either via TLR7/8 agonists or kynurenine infusions, may be a therapeutic option for GVHD or solid organ transplantation.

Blocking germinal center formation by transcriptional and epigenetic modulation

In addition to blockade of costimulatory signals, inhibition of key transcriptional modulators involved in germinal center development, critical for the production of potentially pathogenic antibodies in chronic allograft rejection and chronic GVHD, are also under investigation. Given that expression of the transcription factor B cell lymphoma-6 (Bcl-6) is critical for B cells and Tfh in germinal centers, directly inhibiting Bcl-6 interactions may be an ideal way to limit germinal center formation. One highly specific small molecule inhibitor, compound 79-6, has been investigated as a therapeutic for Bcl-6-dependent B cell lymphomas. In pre-clinical mouse studies, compound 79-6 was shown to kill both mouse and human cancer cells, with no in vivo toxicity and favorable pharmacokinetic properties (111). Given these results in B cell lymphoma models, compound 79-6 is under pre-clinical investigation in mice as a treatment option for chronic allograft rejection and chronic GVHD.

The histone methytransferase EZH2 helps to maintain the gene expression profile of B cells in the germinal center through epigenetic modifications. Deactivating mutations and direct inhibition of EZH2 block germinal center formation and antibody production (112), indicating that this may be a useful target for treating chronic GVHD and chronic solid organ transplant rejection. In addition, EZH2 plays a role in proliferation of alloreactive T cells (113), further enhancing the interest in EZH2 inhibition for GVHD and solid organ transplant rejection. Investigation of EZH2 inhibitors in GVHD are underway, and two different EZH2 inhibitors are in clinical trials as therapeutics for B cell lymphomas (NCT02082977, NCT01897571), enhancing the translational potential of EZH2 inhibition. Given that EZH2 contributes to Treg stability, which may be important in chronic GVHD and tolerance to solid organ allografts, it will be important to see the extent to which prolonged blockade in the clinic will affect long-term tolerance induction (114).

Immune Monitoring

The many new therapies discussed above represent some of the leading candidates for more specific immunosuppression. By focusing more precisely on the initiating pathophysiology of solid organ allograft rejection and GVHD, these new therapies also present the possibility of minimizing or even discontinuing immunosuppressive regimens. For this to be done safely, appropriate and simple peripheral blood-based immune monitoring tests must exist, both to identify “tolerance” and to detect early signs of graft rejection or GVHD.

Efforts to develop immune monitoring tests in solid organ transplantation have focused on kidney and liver transplant recipients. Whereas tolerant renal transplant patients are relatively rare, two series of patients (n=~20–25) have been described with spontaneous tolerance to their grafts (115, 116). Surprisingly, both studies identified a strong B cell “signature” of tolerance, with elevated expression of B cell-derived genes and increased numbers of naïve and transitional B cells in the peripheral blood of tolerant recipients compared with stable patients on immunosuppressive drugs. Interestingly, tolerant patients closely resembled healthy controls, and thus, due to the nature of these studies, it remains possible that the B cell findings are merely a marker of the absence of immunosuppressive drug use. Thus, the ability to use these findings to direct immunosuppression management depends on further confirmation in other studies, determination of the prevalence of the signature among patients taking standard immunosuppression, and the development of assays that can be used to detect incipient rejection.

Parallel efforts have been underway in liver transplantation, where, because the regenerative/repair capacity of the liver is high, immunosuppression withdrawal can be more safely studied. Here, natural killer cell markers have been most prominent, and importantly, there has been little overlap between gene signatures seen in liver and renal transplantation (117), highlighting the fact that all tolerance is not the same, and that organ-specific differences exist.

In addition to the “tolerance signatures” identified in kidney and liver transplant patients, a new method of directly tracking donor reactive T cells in solid organ transplant recipients was recently reported. By isolating recipient cells that proliferate in response to donor antigens and then performing deep-TCR sequencing, donor-reactive T cells were identified (118). Using blood samples from patients who had undergone HLA-mismatched kidney grafts after nonmyeloablative HSCT(86), as well as patients who received conventional kidney allografts with long-term immunosuppression, donor reactive T cells were tracked over time by comparing pre-transplant blood samples with samples obtained sequentially post-transplant. In tolerant patients who had undergone combined HSCT and kidney transplant there was notable deletion of donor reactive clones, whereas in the non-tolerant patients, as well those who received conventional grafts with immunosuppression, deletion of donor reactive clones was not observed. This suggests both that one of the potential mechanisms behind tolerance in solid organ transplantation is deletion of donor reactive T cells, and that this method of tracking donor reactive T cells can discriminate between tolerant and non-tolerant patients. Whereas further testing is required to validate this technique, and also to determine which subsets of donor reactive cells are not deleted (e.g., possibly Tregs), the increasing availability of sequencing resources may allow this type of identification and analysis to become useful for predicting outcomes after solid organ transplantation.

For HSCT patients, a variety of biomarkers have recently been shown to be useful for predicting GVHD severity and treatment outcomes. In particular, a 6-biomarker panel looking at plasma concentrations of IL-2 receptor-, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFR1), hepatocyte growth factor, IL-8, elafin (a skin-specific marker), and regenerating islet-derived 3- (Reg3α, a gastrointestinal tract-specific marker), demonstrated that concentrations of these biomarkers correlated with responsiveness to treatment and 180 day mortality(119). Plasma concentrations of the soluble IL-33 receptor (termed ST2) have been useful for stratifying patients in terms of their risk for developing treatment-resistant GVHD, with higher ST2 concentrations correlating with increased risk of developing this severe form of GVHD (120). In addition, a step forward was made recently in predicting GVHD onset: elevated plasma concentrations of the chemokine CXCL9 were shown to correlate with an increased risk of developing chronic GVHD (121). Such studies have led to a prognostic score for acute GVHD based upon biomarkers using algorithms centered around measuring TNFR1, ST2 and Reg3α (122). As these and additional biomarkers are validated, our ability to predict GVHD development and response to treatment will increase, and this will be critical for augmenting our ability to elucidate the efficacy of our therapies.

Conclusions and Outlook

The past decade has seen substantial advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of tolerance induction and allograft responses. Concurrent with these discoveries is a new armamentarium of drug (both small molecules and biologics) and cell-based therapies that have been approved or are available for clinical testing, making this an exciting time for both the HSCT and solid organ transplant fields. Among the strategies discussed above, a few in particular are generating noteworthy attention in their fields. In solid organ transplantation, blocking CD40/CD154 interactions and developing tolerance with combined stem cell and renal transplantation are drawing particular interest In acute GVHD, Treg infusions, modification of IL-2 common gamma chain cytokines and JAK1/2 inhibition with ruxolitinib are creating substantial interest. In chronic GVHD, Treg promotion with IL-2 combination therapies, as well as bortezomib and ibrutinib are considerable attention. Only further testing will reveal whether these potentially important new therapies merit the excitement they have created. Overall, the development of biomarker panels and repurposing of approaches designed for GVHD, solid organ transplant and autoimmune disorders offers new and potentially more selective approaches for achieving the durable tolerance induction needed for successful transplantation and at the same time may obviate the need for global immune suppression.

Acknowledgements

Funding: The authors are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UM1AI109565 and R01 AI-037691 (LAT), P01 AI056299 (LAT, BRB) and R01 HL56067, AI112613, AI34495, P01 CA142106 (BRB) and T32 AI007313, F30 HL121873 (CHM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

Turka: Consulting: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, NeXeption, and Pelican Therapeutics.

Patents: none.

Blazar: Consulting: Kadmon Pharmaceuticals Inc; Bristol-Myers-Squibb; Merck-Sharpe-Dohme

Patents: Regulatory T cells and their use in immunotherapy and suppression of the autoimmune response 7,651,855, January 26, 2010 and 8,129,185

Patents Pending: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathways in the generation of regulatory T cells, January 6, 2006 (priority date; January 5, 2007 filing date)

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and PD-1/PD-L pathways in the activation of regulatory T cells, filing of provisional patent, February 14, 2007

Inducible regulatory T cell generation for hematopoietic cell transplants (UMN Z09026), U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 61/132,601, Filed June 19, 2008

Large-scale expansion approaches for regulatory T cells (UMN no. 20100109), January, 2009

Methods to expand a T regulatory cell master cell bank, (UPenn/UMN no. 61322186), April 8, 2010

Methods of treating and preventing alloantibody driven chronic graft-versus-host diseases, Provisional Patent Application No. 61/910,944, filed December 2, 2013

Role of ROCK2 inhibitors in chronic GVHD, Provisional Patent Application No. 61/977,564, filed April 9, 2014.

Use of compositions modulating chromatin structure for graft versus host disease (GVHD), Provisional Patent Application No. 62/076,358, filed November 6, 2014

Mcdonald-Hyman: Consulting: none

Patents: none.

References

- 1.Pasquini M, Wang Z. “Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2014,”. 2014 Available at http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 2.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, Hingorani S, Sorror ML, Boeckh M, Martin PJ, Sandmaier BM, Marr KA, Appelbaum FR, Storb R, McDonald GB. Reduced Mortality after Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Wang Z, Sobocinski KA, Jacobsohn D, Sorror ML, Horowitz MM, Bolwell B, Rizzo JD, Socié G. Long-Term Survival and Late Deaths After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2230–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welniak LA, Blazar BR, Murphy WJ. Immunobiology of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Annual Review of Immunology. 2007;25:139–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2012;12:443–458. doi: 10.1038/nri3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtan SG, Pasquini M, Weisdorf DJ. Acute graft-versus-host disease: a bench-to-bedside update. Blood. 2014;124:363–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-514786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piotti G, Palmisano A, Maggiore U, Buzio C. Vascular Endothelium as a Target of Immune Response in Renal Transplant Rejection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5:505. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nankivell BJ, Alexander SI. Rejection of the Kidney Allograft. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:1451–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issa F, Schiopu A, Wood KJ. Role of T cells in graft rejection and transplantation tolerance. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2010;6:155–169. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelishadi SS, Azimzadeh AM, Zhang T, Stoddard T, Welty E, Avon C, Higuchi M, Laaris A, Cheng X-F, McMahon C, Pierson RN. Preemptive CD20(+) B cell depletion attenuates cardiac allograft vasculopathy in cyclosporine-treated monkeys. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:1275–1284. doi: 10.1172/JCI41861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loupy A, Hill G, Jordan S. The impact of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies on late kidney allograft failure. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2012;8:348–357. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markey KA, MacDonald KPA, Hill GR. The biology of graft-versus-host disease: experimental systems instructing clinical practice. Blood. 2014;124:354–362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-514745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cueto-Manzano AM, Morales-Buenrostro LE, Gonzalez-Espinoza L, Gonzalez-Tableros N, Martin-del-Campo F, Correa-Rotter R, Valera I, Alberu J. Markers of Inflammation Before and After Renal Transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;80:47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000164348.16689.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth AJ, Grabauskiene S, Wood SC, Lu G, Burrell BE, Bishop DK. IL-6 Promotes Cardiac Graft Rejection Mediated by CD4+ Cells. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:5764–5771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tawara I, Koyama M, Liu C, Toubai T, Thomas D, Evers R, Chockley P, Nieves E, Sun Y, Lowler KP, Malter C, Nishimoto N, Hill GR, Reddy P. Interleukin-6 Modulates Graft-versus-Host Responses after Experimental Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:77–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy GA, Varelias A, Vuckovic S, Le Texier L, Gartlan KH, Zhang P, Thomas G, Anderson L, Boyle G, Cloonan N, Leach J, Sturgeon E, Avery J, Olver SD, Lor M, Misra AK, Hutchins C, Morton AJ, Durrant STS, Subramoniapillai E, Butler JP, Curley CI, MacDonald KPA, Tey S-K, Hill GR. Addition of interleukin-6 inhibition with tocilizumab to standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: a phase 1/2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:1451–1459. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim G, Lee N, Pi R, Lim Y, Lee Y, Lee J, Jeong H, Chung S. Arch. Pharm. Res. IL-6 inhibitors for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: past, present, and future. Paper in Press, published 2015 as 2010.1007/s12272-12015-10569-12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vries DK, Lindeman JHN, Tsikas D, De Heer E, Roos A, De Fijter JW, Baranski AG, Van Pelt J, Schaapherder AFM. Early Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Humans Is Dominated by IL-6 Release from the Allograft. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9:1574–1584. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das R, Komorowski R, Hessner MJ, Subramanian H, Huettner CS, Cua D, Drobyski WR. Blockade of interleukin-23 signaling results in targeted protection of the colon and allows for separation of graft-versus-host and graft-versus-leukemia responses. 2010;115:5249–5258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson E, Garside P, Bradley JA, More IA, Mowat AM. Neutralizing IL-12 during induction of murine acute graft-versus-host disease polarizes the cytokine profile toward a Th2-type alloimmune response and confers long term protection from disease. The Journal of Immunology. 1997;159:1208–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pidala J, Perez L, Beato F, Anasetti C. Ustekinumab demonstrates activity in glucocorticoid-refractory acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:747–748. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, Puig L, Rahman P, Ritchlin C, Brodmerkel C, Li S, Wang Y, Mendelsohn AM, Doyle MK. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. The Lancet. 2013;382:780–789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murai M, Yoneyama H, Ezaki T, Suematsu M, Terashima Y, Harada A, Hamada H, Asakura H, Ishikawa H, Matsushima K. Peyer's patch is the essential site in initiating murine acute and lethal graft-versus-host reaction. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:154–160. doi: 10.1038/ni879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murai M, Yoneyama H, Harada A, Yi Z, Vestergaard C, Guo B, Suzuki K, Asakura H, Matsushima K. Active participation of CCR5(+)CD8(+) T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of liver injury in graft-versus-host disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;104:49–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahin K, Sartor M, Hart DNJ, Bradstock KF. Alterations in Chemokine Receptor CCR5 Expression on Blood Dendritic Cells Correlate With Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Transplantation. 2013;96:753–762. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829e6d5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reshef R, Luger SM, Hexner EO, Loren AW, Frey NV, Nasta SD, Goldstein SC, Stadtmauer EA, Smith J, Bailey S, Mick R, Heitjan DF, Emerson SG, Hoxie JA, Vonderheide RH, Porter DL. Blockade of Lymphocyte Chemotaxis in Visceral Graft-versus-Host Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:135–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wysocki CA, Burkett SB, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Kirby SL, Luster AD, McKinnon K, Blazar BR, Serody JS. Differential Roles for CCR5 Expression on Donor T Cells during Graft-versus-Host Disease Based on Pretransplant Conditioning. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;173:845–854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalloul AH. B-cell-mediated strategies to fight chronic allograft rejection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4:444–452. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma H-H, Ziegler J, Li C, Sepulveda A, Bedeir A, Grandis J, Lentzsch S, Mapara MY. Sequential activation of inflammatory signaling pathways during graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): Early role for STAT1 and STAT3. Cellular Immunology. 2011;268:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spoerl S, Mathew NR, Bscheider M, Schmitt-Graeff A, Chen S, Mueller T, Verbeek M, Fischer J, Otten V, Schmickl M, Maas-Bauer K, Finke J, Peschel C, Duyster J, Poeck H, Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N. Activity of therapeutic JAK 1/2 blockade in graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;123:3832–3842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-543736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Levy RS, Gupta V, DiPersio JF, Catalano JV, Deininger MWN, Miller CB, Silver RT, Talpaz M, Winton EF, Harvey JH, Arcasoy MO, Hexner EO, Lyons RM, Raza A, Vaddi K, Sun W, Peng W, Sandor V, Kantarjian H. Three-year efficacy, overall survival, and safety of ruxolitinib therapy in patients with myelofibrosis from the COMFORT-I study. Haematologica. Paper in Press, published 2015 as 2010.3324/haematol.2014.115840. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hechinger A-K, Smith BAH, Flynn R, Hanke K, McDonald-Hyman C, Taylor PA, Pfeifer D, Hackanson B, Leonhardt F, Prinz G, Dierbach H, Schmitt-Graeff A, Kovarik J, Blazar BR, Zeiser R. Therapeutic activity of multiple common gamma chain cytokine inhibition in acute and chronic GvHD. Blood. 2014;125:570–580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-581793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borie DC, Changelian PS, Larson MJ, Si M-S, Paniagua R, Higgins JP, Holm B, Campbell A, Lau M, Zhang S, Flores MG, Rousvoal G, Hawkins J, Ball DA, Kudlacz EM, Brissette WH, Elliott EA, Reitz BA, Morris RE. Immunosuppression by the JAK3 Inhibitor CP-690,550 Delays Rejection and Significantly Prolongs Kidney Allograft Survival in Nonhuman Primates. Transplantation. 2005;79:791–801. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000157117.30290.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borie DC, Larson MJ, Flores MG, Campbell A, Rousvoal G, Zhang S, Higgins JP, Ball DJ, Kudlacz EM, Brissette WH, Elliott EA, Reitz BA, Changelian PS. Combined Use of the JAK3 Inhibitor CP-690,550 with Mycophenolate Mofetil to Prevent Kidney Allograft Rejection in Nonhuman Primates. Transplantation. 2005;80:1756–1764. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000184634.25042.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Gurp E, Weimar W, Gaston R, Brennan D, Mendez R, Pirsch J, Swan S, Pescovitz MD, Ni G, Wang C, Krishnaswami S, Chow V, Chan G. Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Study of CP-690 550 in Stable Renal Allograft Recipients: Preliminary Findings of Safety, Tolerability, Effects on Lymphocyte Subsets and Pharmacokinetics. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;8:1711–1718. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincenti F, Tedesco Silva H, Busque S, O'Connell P, Friedewald J, Cibrik D, Budde K, Yoshida A, Cohney S, Weimar W, Kim YS, Lawendy N, Lan SP, Kudlacz E, Krishnaswami S, Chan G. Randomized Phase 2b Trial of Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in De Novo Kidney Transplant Patients: Efficacy, Renal Function and Safety at 1 Year. American Journal of Transplantation. 2012;12:2446–2456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez-Rodriguez J, Wohlfert EA, Handon R, Meylan F, Wu JZ, Anderson SM, Kirby MR, Belkaid Y, Schwartzberg PL. Itk-mediated integration of T cell receptor and cytokine signaling regulates the balance between Th17 and regulatory T cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2014;211:529–543. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herman SEM, Gordon AL, Hertlein E, Ramanunni A, Zhang X, Jaglowski S, Flynn J, Jones J, Blum KA, Buggy JJ, Hamdy A, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood. 2011;117:6287–6296. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubovsky JA, Flynn R, Du J, Harrington BK, Zhong Y, Kaffenberger B, Yang C, Towns WH, Lehman A, Johnson AJ, Muthusamy N, Devine SM, Jaglowski S, Serody JS, Murphy WJ, Munn DH, Luznik L, Hill GR, Wong HK, MacDonald KKP, Maillard I, Koreth J, Elias L, Cutler C, Soiffer RJ, Antin JH, Ritz J, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Byrd JC, Blazar BR. Ibrutinib treatment ameliorates murine chronic graft-versus-host disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124:4867–4876. doi: 10.1172/JCI75328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubovsky JA, Beckwith KA, Natarajan G, Woyach JA, Jaglowski S, Zhong Y, Hessler JD, Liu T-M, Chang BY, Larkin KM, Stefanovski MR, Chappell DL, Frissora FW, Smith LL, Smucker KA, Flynn JM, Jones JA, Andritsos LA, Maddocks K, Lehman AM, Furman R, Sharman J, Mishra A, Caligiuri MA, Satoskar AR, Buggy JJ, Muthusamy N, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC. Ibrutinib is an irreversible molecular inhibitor of ITK driving a Th1-selective pressure in T lymphocytes. Blood. 2013;122:2539–2549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O'Brien S, Barrientos JC, Kay NE, Reddy NM, Coutre S, Tam CS, Mulligan SP, Jaeger U, Devereux S, Barr PM, Furman RR, Kipps TJ, Cymbalista F, Pocock C, Thornton P, Caligaris-Cappio F, Robak T, Delgado J, Schuster SJ, Montillo M, Schuh A, de Vos S, Gill D, Bloor A, Dearden C, Moreno C, Jones JJ, Chu AD, Fardis M, McGreivy J, Clow F, James DF, Hillmen P. Ibrutinib versus Ofatumumab in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russ GR, Tedesco-Silva H, Kuypers DR, Cohney S, Langer RM, Witzke O, Eris J, Sommerer C, von Zur-Mühlen B, Woodle ES, Gill J, Ng J, Klupp J, Chodoff L, Budde K. Efficacy of Sotrastaurin Plus Tacrolimus After De Novo Kidney Transplantation: Randomized, Phase II Trial Results. American Journal of Transplantation. 2013;13:1746–1756. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haarberg KMK, Li J, Heinrichs J, Wang D, Liu C, Bronk CC, Kaosaard K, Owyang AM, Holland S, Masuda E, Tso K, Blazar BR, Anasetti C, Beg AA, Yu X-Z. Pharmacologic inhibition of PKCα and PKCθ prevents GVHD while preserving GVL activity in mice. Blood. 2013;122:2500–2511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Socié G, Ritz J. Current issues in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;124:374–384. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-514752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnston HF, Xu Y, Racine JJ, Cassady K, Ni X, Wu T, Chan A, Forman S, Zeng D. Administration of Anti-CD20 mAb Is Highly Effective in Preventing but Ineffective in Treating Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease While Preserving Strong Graft-Versus-Leukemia Effects. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arai S, Sahaf B, Narasimhan B, Chen GL, Jones CD, Lowsky R, Shizuru JA, Johnston LJ, Laport GG, Weng W-K, Benjamin JE, Schaenman J, Brown J, Ramirez J, Zehnder JL, Negrin RS, Miklos DB. Prophylactic rituximab after allogeneic transplantation decreases B-cell alloimmunity with low chronic GVHD incidence. Blood. 2012;119:6145–6154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cutler C, Kim HT, Bindra B, Sarantopoulos S, Ho VT, Chen Y-B, Rosenblatt J, McDonough S, Watanaboonyongcharoen P, Armand P, Koreth J, Glotzbecker B, Alyea E, Blazar BR, Soiffer RJ, Ritz J, Antin JH. Rituximab prophylaxis prevents corticosteroid-requiring chronic GVHD after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: results of a phase 2 trial. Blood. 2013;122:1510–1517. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnett ANR, Hadjianastassiou VG, Mamode N. Rituximab in renal transplantation. Transplant International. 2013;26:563–575. doi: 10.1111/tri.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun K, Welniak LA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, O'Shaughnessy MJ, Liu H, Barao I, Riordan W, Sitcheran R, Wysocki C, Serody JS, Blazar BR, Sayers TJ, Murphy WJ. Inhibition of acute graft-versus-host disease with retention of graft-versus-tumor effects by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:8120–8125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401563101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pai CCS, Hsiao H-H, Sun K, Chen M, Hagino T, Tellez J, Mall C, Blazar BR, Monjazeb A, Abedi M, Murphy WJ. Therapeutic Benefit of Bortezomib on Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Is Tissue Specific and Is Associated with Interleukin-6 Levels. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:1899–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pai CCS, Chen M, Mirsoian A, Grossenbacher SK, Tellez J, Ames E, Sun K, Jagdeo J, Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease with bortezomib. Blood. 2014;124:1677–1688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herrera AF, Kim HT, Bindra B, Jones KT, Alyea EP, Armand P, Cutler CS, Ho VT, Nikiforow S, Blazar BR, Ritz J, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Koreth J. A Phase II Study of Bortezomib Plus Prednisone for Initial Therapy of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:1737–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sberro-Soussan R, Zuber J, Suberbielle-Boissel C, Candon S, Martinez F, Snanoudj R, Rabant M, Pallet N, Nochy D, Anglicheau D, Leruez M, Loupy A, Thervet E, Hermine O, Legendre C. Bortezomib as the Sole Post-Renal Transplantation Desensitization Agent Does Not Decrease Donor-Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and Maintenance of Regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuoka K, Koreth J, Kim HT, Bascug G, McDonough S, Kawano Y, Murase K, Cutler C, Ho VT, Alyea EP, Armand P, Blazar BR, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Ritz J. Low-Dose Interleukin-2 Therapy Restores Regulatory T Cell Homeostasis in Patients with Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5:179ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin H-J, Baker J, Leveson-Gower DB, Smith AT, Sega EI, Negrin RS. Rapamycin and IL-2 reduce lethal acute graft-versus-host disease associated with increased expansion of donor type CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2011;118:2342–2350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodyear OC, Dennis M, Jilani NY, Loke J, Siddique S, Ryan G, Nunnick J, Khanum R, Raghavan M, Cook M, Snowden JA, Griffiths M, Russell N, Yin J, Crawley C, Cook G, Vyas P, Moss P, Malladi R, Craddock CF. Azacitidine augments expansion of regulatory T cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2012;119:3361–3369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi J, Ritchey J, Prior JL, Holt M, Shannon WD, Deych E, Piwnica-Worms DR, DiPersio JF. In vivo administration of hypomethylating agents mitigate graft-versus-host disease without sacrificing graft-versus-leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:129–139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, de Zoeten EF, Greene MI, Hancock WW. Immunomodulatory effects of deacetylase inhibitors: therapeutic targeting of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:969–981. doi: 10.1038/nrd3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tao R, de Zoeten EF, Ozkaynak E, Chen C, Wang L, Porrett PM, Li B, Turka LA, Olson EN, Greene MI, Wells AD, Hancock WW. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/nm1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi SW, Braun T, Chang L, Ferrara JLM, Pawarode A, Magenau JM, Hou G, Beumer JH, Levine JE, Goldstein S, Couriel DR, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Krijanovski OI, Kitko C, Yanik GA, Lehmann MH, Tawara I, Sun Y, Paczesny S, Mapara MY, Dinarello CA, DiPersio JF, Reddy P. Vorinostat plus tacrolimus and mycophenolate to prevent graft-versus-host disease after related-donor reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase 1/2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:87–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70512-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choi SW, Gatza E, Hou G, Sun Y, Whitfield J, Song Y, Oravecz-Wilson K, Tawara I, Dinarello CA, Reddy P. Histone deacetylase inhibition regulates inflammation and enhances Tregs after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in humans. Blood. 2015;125:815–819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-605238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanakry CG, Ganguly S, Zahurak M, Bolaños-Meade J, Thoburn C, Perkins B, Fuchs EJ, Jones RJ, Hess AD, Luznik L. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Expression Drives Human Regulatory T Cell Resistance to Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5:211ra157. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanakry CG, O'Donnell PV, Furlong T, de Lima MJ, Wei W, Medeot M, Mielcarek M, Champlin RE, Jones RJ, Thall PF, Andersson BS, Luznik L. Multi-Institutional Study of Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide As Single-Agent Graft-Versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis After Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation Using Myeloablative Busulfan and Fludarabine Conditioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3497–3505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]