Abstract

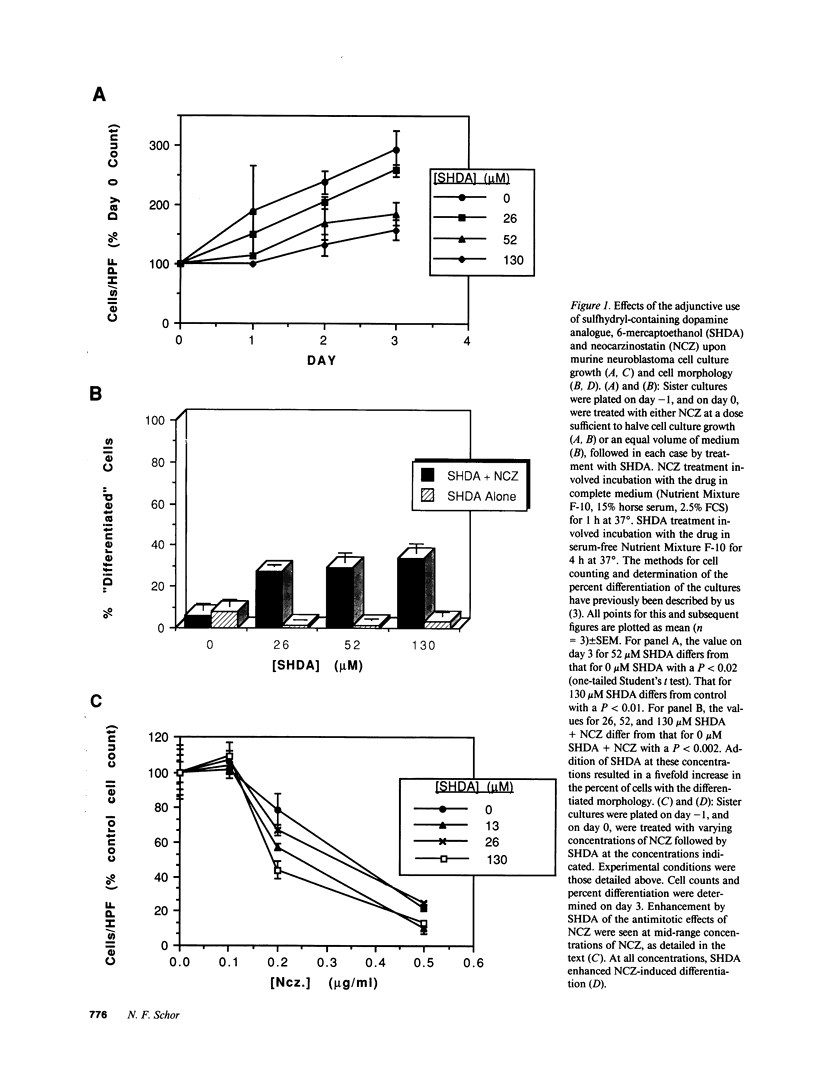

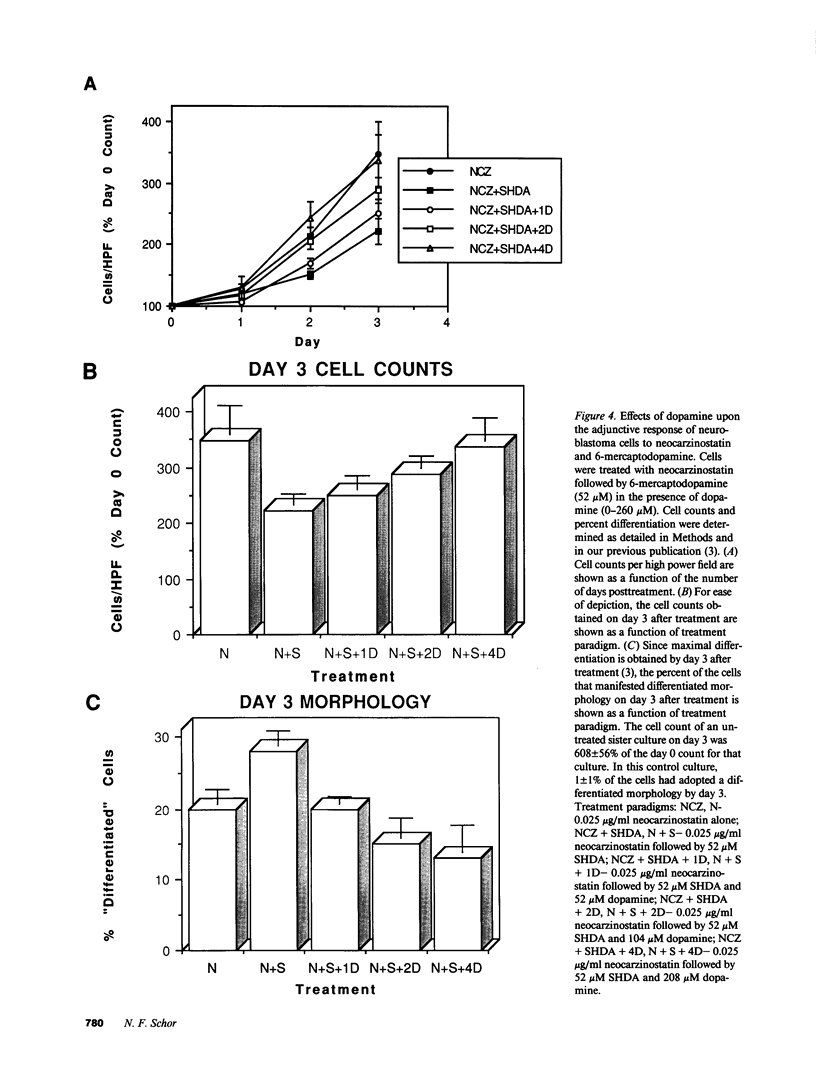

The development of chemotherapeutic approaches to cancer has been hampered by the toxicity of proposed agents for normal rapidly dividing cells. By using neocarzinostatin, a "pro-drug" which is activated by reduction by thiol compounds, adjunctively with 6-mercaptodopamine, a thiol-containing dopamine analogue, we have been able to enhance neocarzinostatin toxicity for cells of the neural crest tumor neuroblastoma. Thiol compounds that are not neurotransmitter analogues do not act synergistically with neocarzinostatin in this system. Since most normal rapidly dividing cells do not have surface dopamine receptors, we propose this approach for the selective targeting of toxicity for neuroblastoma cells. We further introduce cell-selective activation of prodrugs as a new chemotherapeutic strategy which demands further development.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chavdarian C. G., Castagnoli N., Jr Synthesis, redox characteristics, and in vitro norepinephrine uptake inhibiting properties of 2-(2-mercapto-4,5-dihydroxyphenyl)ethylamine (6-mercaptodopamine). J Med Chem. 1979 Nov;22(11):1317–1322. doi: 10.1021/jm00197a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornaglia-Ferraris P., Ponzoni M., Montaldo P., Mariottini G. L., Donti E., Di Martino D., Tonini G. P. A new human highly tumorigenic neuroblastoma cell line with undetectable expression of N-myc. Pediatr Res. 1990 Jan;27(1):1–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff W. G., Mitchell J. B. Glutathione dependence of neocarzinostatin cytotoxicity and mutagenicity in Chinese hamster V-79 cells. Cancer Res. 1985 Oct;45(10):4760–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLMAN G. L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959 May;82(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Goldberg I. H. Activation and inactivation of neocarzinostatin-induced cleavage of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978 Aug;5(8):2959–2967. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.8.2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Napier M. A., Goldberg I. H. Roles of chromophore and apo-protein in neocarzinostatin action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Apr;77(4):1970–1974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Ueda M., Morinaga T., Matsumoto T. Conjugation of poly(styrene-co-maleic acid) derivatives to the antitumor protein neocarzinostatin: pronounced improvements in pharmacological properties. J Med Chem. 1985 Apr;28(4):455–461. doi: 10.1021/jm00382a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey E. M., Murphy W., Zander A., Bodey G. P. Neocarzinostatin: report of a phase II clinical trial. Cancer Treat Rep. 1981 Jul-Aug;65(7-8):699–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier M. A., Holmquist B., Strydom D. J., Goldberg I. H. Neocarzinostatin: spectral characterization and separation of a non-protein chromophore. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979 Jul 27;89(2):635–642. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)90677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale R. B., Yagoda A., Watson R. C., Stover D. E. Phase II trial of neocarzinostatin in patients with bladder and prostatic cancer: toxicity of a five-day iv bolus schedule. Cancer. 1980 Jun 1;45(11):2836–2842. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800601)45:11<2836::aid-cncr2820451120>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka K., Miyamoto Y., Matsumura Y., Tanaka S., Oda T., Suzuki F., Maeda H. Enhanced intestinal absorption of a hydrophobic polymer-conjugated protein drug, smancs, in an oily formulation. Pharm Res. 1990 Aug;7(8):852–855. doi: 10.1023/a:1015917000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K. N., Kumar S. Role of cyclic AMP in differentiation of human neuroblastoma cells in culture. Cancer. 1975 Oct;36(4):1338–1343. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1338::aid-cncr2820360422>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake I., Tari K., Yamamoto M., Nishimura H. Neocarzinostatin-induced complete regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1985 Jan;133(1):87–89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)48799-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor N. F. Neocarzinostatin induces neuronal morphology of mouse neuroblastoma in culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989 Jun;249(3):906–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger R. C., Siegel S. E., Sidell N. Neuroblastoma: clinical perspectives, monoclonal antibodies, and retinoic acid. Ann Intern Med. 1982 Dec;97(6):873–884. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-6-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig G. F., Meister A. Glutathione biosynthesis; gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase from rat kidney. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:379–390. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969 Mar;27(3):502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]