Abstract

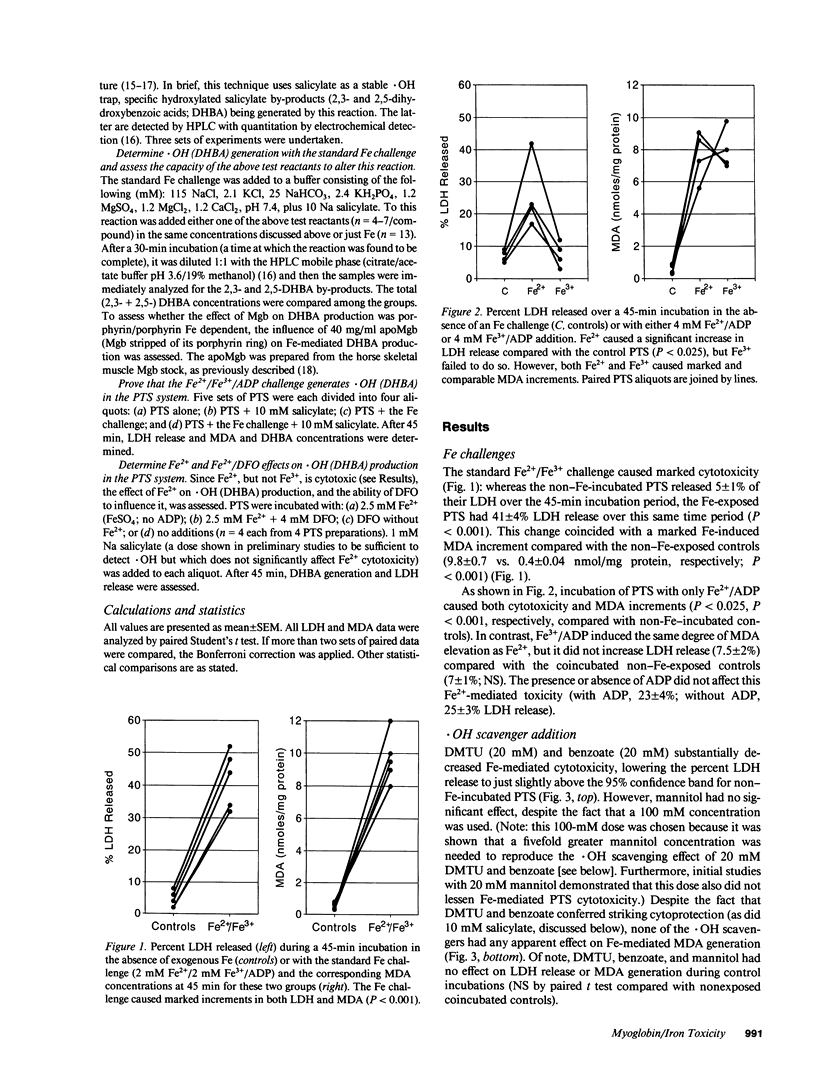

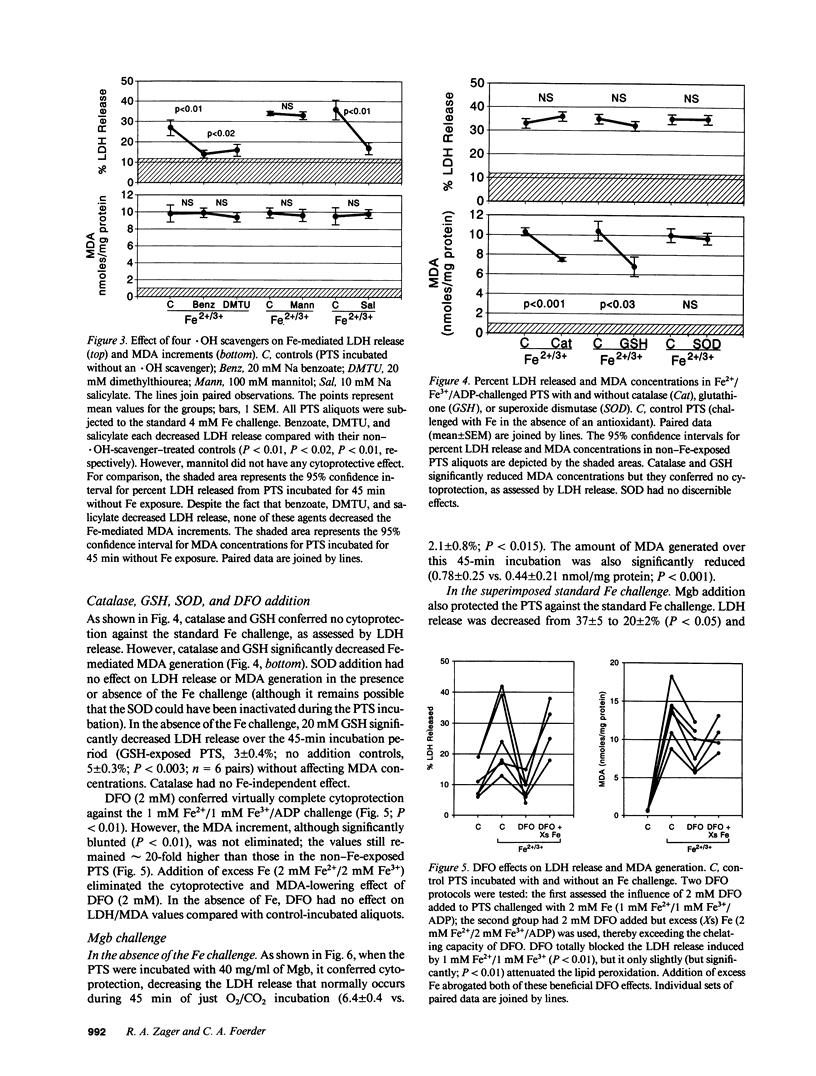

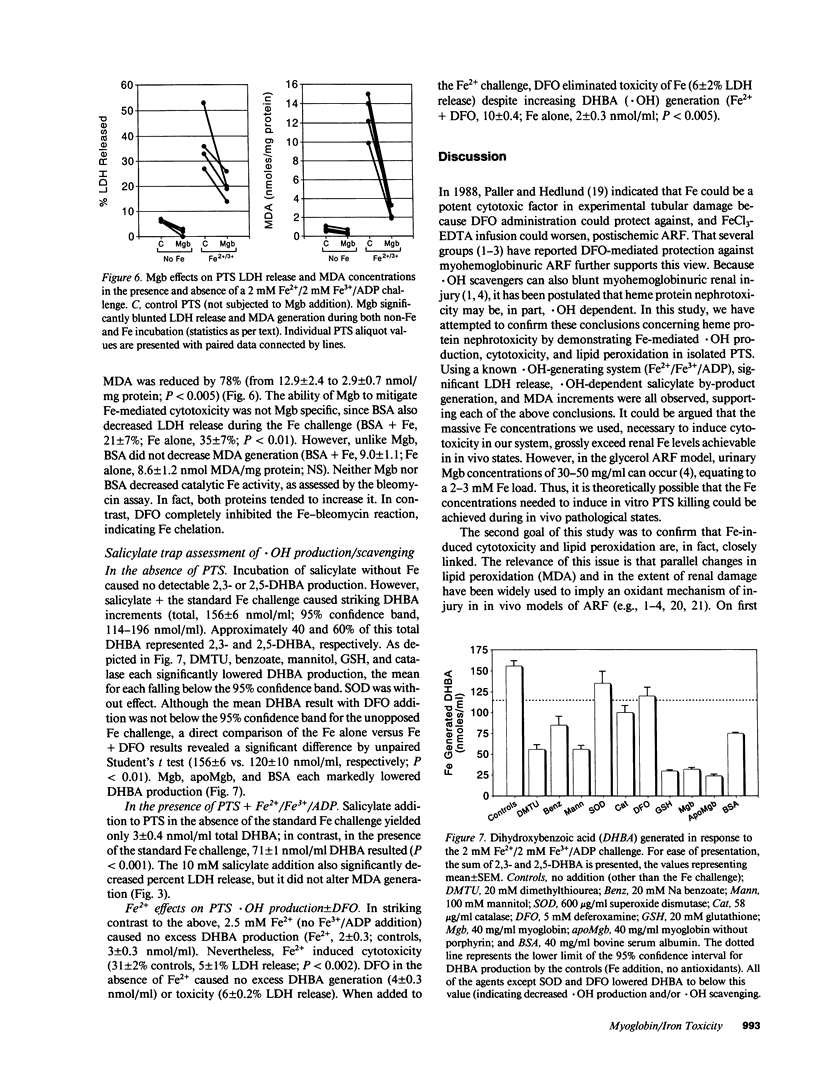

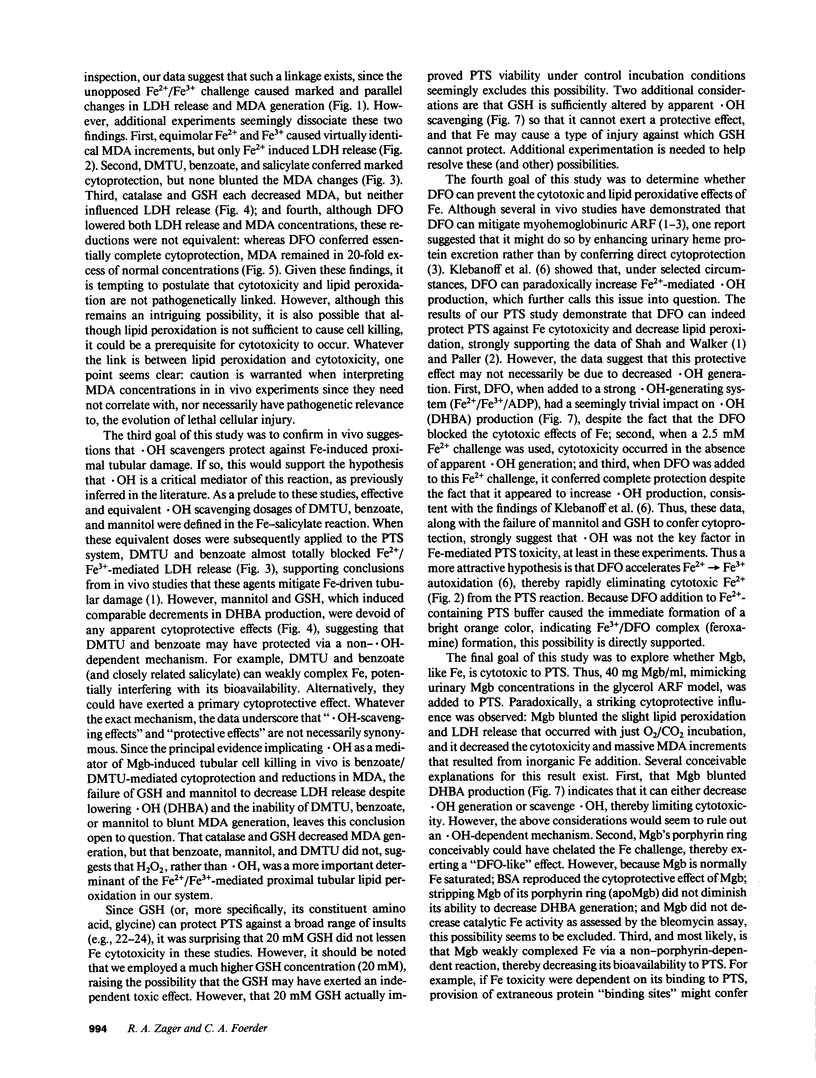

Recent in vivo studies suggest that heme Fe causes proximal tubular lipid peroxidation and cytotoxicity, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of myoglobinuric (Mgb) acute renal failure. Because hydroxyl radical (.OH) scavengers [dimethylthiourea (DMTU), benzoate, mannitol] can mitigate this injury, it is postulated that .OH is a mediator of Mgb-induced renal damage. The present study has tested these hypotheses using an isolated rat proximal tubular segment (PTS) system. An equal mixture of Fe2+/Fe3+ (4 mM total), when added to PTS, caused marked cytotoxicity [as defined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release] and lipid peroxidation [assessed by malondialdehyde (MDA) increments]. Fe2+ or Fe3+ alone each induced massive MDA elevations, but only Fe2+ caused cytotoxicity. Although both DMTU and benzoate decreased LDH release during the Fe2+/Fe3+ challenge, mannitol and GSH did not, despite equivalent reductions in .OH (gauged by the salicylate trap method). GSH and catalase (but not DMTU, benzoate, or mannitol) decreased MDA concentrations, suggesting the Fe-driven lipid peroxidation was more H2O2 than .OH dependent. Deferoxamine totally blocked Fe-induced LDH release, even under conditions in which it caused an apparent increase in .OH generation. Mgb paradoxically protected against Fe-mediated PTS injury, an effect largely reproduced by albumin. In conclusion, these data suggest that: (a) Fe can cause PTS lipid peroxidation and cytotoxicity by a non-.OH-dependent mechanism; (b) Fe-mediated cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation are not necessarily linked; and (c) Mgb paradoxically protects PTS against Fe-mediated injury, suggesting that: (i) Mgb Fe may require liberation from its porphyrin ring before exerting toxicity; and (ii) the protein residue may blunt the resulting injury.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bucher J. R., Tien M., Aust S. D. The requirement for ferric in the initiation of lipid peroxidation by chelated ferrous iron. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983 Mar 29;111(3):777–784. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Carney J. M., Duchon A., Floyd R. A., Chevion M. Oxygen free radical involvement in ischemia and reperfusion injury to brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988 May 26;88(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Watson J. J., Wong P. K. Sensitive assay of hydroxyl free radical formation utilizing high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection of phenol and salicylate hydroxylation products. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984 Dec;10(3-4):221–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootveld M., Halliwell B. Aromatic hydroxylation as a potential measure of hydroxyl-radical formation in vivo. Identification of hydroxylated derivatives of salicylate in human body fluids. Biochem J. 1986 Jul 15;237(2):499–504. doi: 10.1042/bj2370499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Hou Y. Y. Iron complexes and their reactivity in the bleomycin assay for radical-promoting loosely-bound iron. Free Radic Res Commun. 1986;2(3):143–151. doi: 10.3109/10715768609088066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff S. J., Waltersdorph A. M., Michel B. R., Rosen H. Oxygen-based free radical generation by ferrous ions and deferoxamine. J Biol Chem. 1989 Nov 25;264(33):19765–19771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel L. J., Schnellmann R. G., Jacobs W. R. Intracellular glutathione in the protection from anoxic injury in renal proximal tubules. J Clin Invest. 1990 Feb;85(2):316–324. doi: 10.1172/JCI114440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara M., Uchiyama M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal Biochem. 1978 May;86(1):271–278. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRY W. L., SCHAEFER J. A., MUELLER C. B. Experimental studies of acute renal failure. I. The protective effect of mannitol. J Urol. 1963 Jan;89:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller M. S., Hedlund B. E. Role of iron in postischemic renal injury in the rat. Kidney Int. 1988 Oct;34(4):474–480. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller M. S. Hemoglobin- and myoglobin-induced acute renal failure in rats: role of iron in nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 1988 Sep;255(3 Pt 2):F539–F544. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller M. S., Hoidal J. R., Ferris T. F. Oxygen free radicals in ischemic acute renal failure in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1984 Oct;74(4):1156–1164. doi: 10.1172/JCI111524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothgeb T. M., Gurd F. R. Physical methods for the study of myoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:473–486. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. V., Walker P. D. Evidence suggesting a role for hydroxyl radical in glycerol-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1988 Sep;255(3 Pt 2):F438–F443. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. M., Davis J. A., Abarzua M., Rajan T. Cytoprotective effects of glycine and glutathione against hypoxic injury to renal tubules. J Clin Invest. 1987 Nov;80(5):1446–1454. doi: 10.1172/JCI113224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. M., Davis J. A., Abarzua M., Smith R. K., Kunkel R. Ouabain-induced lethal proximal tubule cell injury is prevented by glycine. Am J Physiol. 1990 Feb;258(2 Pt 2):F346–F355. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.2.F346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. M., Davis J. A., Roeser N. F., Venkatachalam M. A. Role of increased cytosolic free calcium in the pathogenesis of rabbit proximal tubule cell injury and protection by glycine or acidosis. J Clin Invest. 1991 Feb;87(2):581–590. doi: 10.1172/JCI115033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Foerder C., Bredl C. The influence of mannitol on myoglobinuric acute renal failure: functional, biochemical, and morphological assessments. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991 Oct;2(4):848–855. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V24848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Gamelin L. M. Pathogenetic mechanisms in experimental hemoglobinuric acute renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1989 Mar;256(3 Pt 2):F446–F455. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.3.F446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A. Gentamicin nephrotoxicity in the setting of acute renal hypoperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1988 Apr;254(4 Pt 2):F574–F581. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.254.4.F574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Gmur D. J., Bredl C. R., Eng M. J. Temperature effects on ischemic and hypoxic renal proximal tubular injury. Lab Invest. 1991 Jun;64(6):766–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A. Studies of mechanisms and protective maneuvers in myoglobinuric acute renal injury. Lab Invest. 1989 May;60(5):619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]