Abstract

Aliphatic amides are selectively functionalized at the γ and δ–positions through a directed radical 1,5 and 1,6-H-abstraction. The initially formed γ- or δ-lactams are intercepted by NIS and TMSN3 leading to multiple C–H functionalizations at the γ, δ, and ε–positions. This new reactivity is exploited to convert alkyls into amino alcohols or allylic amines.

Pd-catalyzed β-C–H functionalizations of aliphatic acids using directing groups have been extensively studied in the past decade. A diverse range of transformations have been developed using both Pd(II)1, Pd(0)2 and other transition metal catalysts.3 In contrast, γ-C–H functionalizations are still rare.4 Inspired by pioneering studies on 1,5 and 1,6-H-abstraction,5, 6 we questioned whether the reactivity and selectivity of these radical abstraction could be harnessed to develop wide range of catalytic C–H functionalization reactions of aliphatic acids or amides. An extensive literature survey revealed two potential challenges. First, radical abstractions of γ- or δ-C–H bonds of aliphatic amides have only been demonstrated for C–H bond adjacent to an oxygen atom.6d Second, the vast majority of the reactions initiated by nitrogen radicals leads to cyclization (eq 1)6e instead of intermolecular functionalizations with the exception of a few examples involving amine substrates.6c This suggests that the facile cyclization pathway might be difficult to prevent. Herein we report an empirically discovered a sequential radical γ-, or δ-C–H lactamization and subsequent reaction with NIS and TMSN3 to give δ-iodo-γ-lactams or δ, ε-dehydrogenated γ-lactams. Structural elaborations of these highly functionalized lactams allows for an overall conversion of simple alkyls into olefins, amino alcohols or allylic amines.

|

(1) |

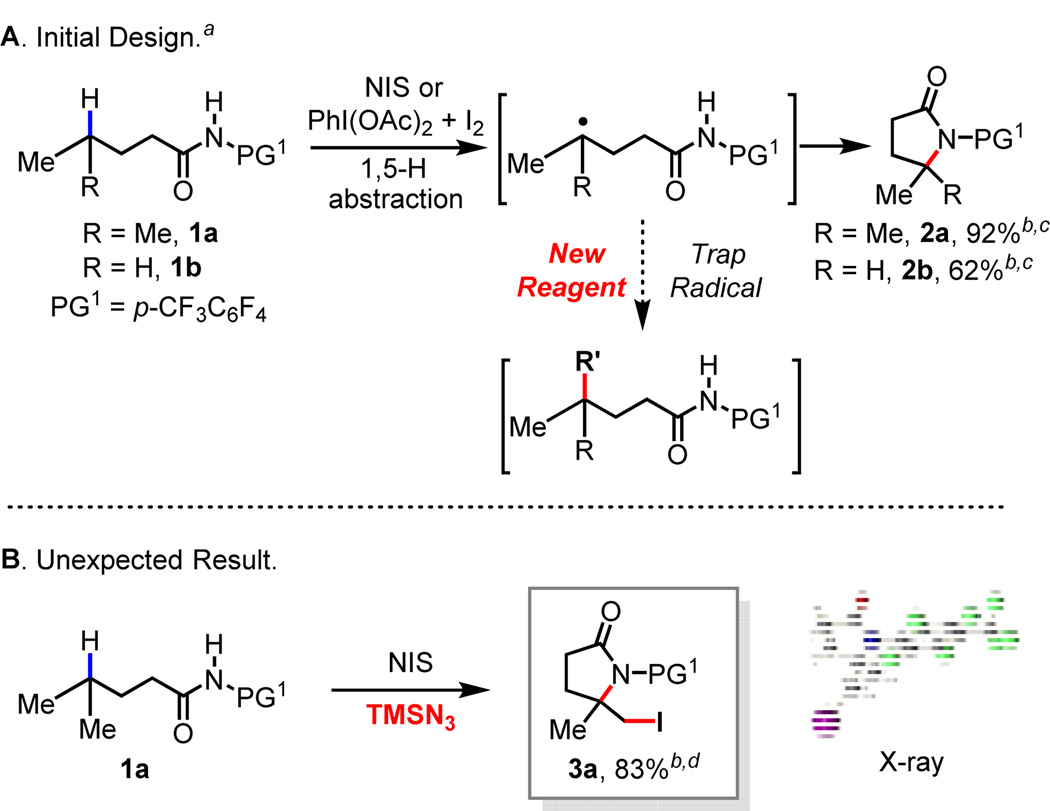

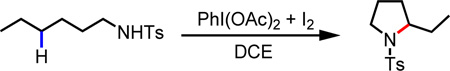

Our initial efforts to trigger the radical H-abstraction by the amide were guided by the conditions used for radical cyclization of toluenesulfonyl protected amines.6e We choose to use our N-heptafluorotolyl amide (PG1) directing group1b anticipating this would accommodate subsequent functionalizations with a metal catalyst if the γ-carbon centered radical is formed and intercepted by the metal. Through an extensive survey of radical initiators, iodine sources, solvents and other parameters (see Supporting Information for details), it was found that a combination of PhI(OAc)2 and I2 facilitated the desired lactamization reaction of 1a to give the γ-lactamization product 2a in excellent yield (Scheme 1A). Next, we sought to identify an appropriate metal catalyst or reagent that can intercept the γ-carbon centered radical prior to the cyclization thereby achieving a general intermolecular γ-C–H functionalization method.

Scheme 1.

Initial Design and Unexpected Results

aCondition A: 1a (0.1 mmol), NIS (3 equiv.), DCE (1 mL), 100 °C, air, 14 h. Condition B: 1a (0.1 mmol), PhI(OAc)2 (1.5 equiv.), I2 (1.5 equiv.), DCE, r.t., air, 48 h. bIsolated yield. cFor substrate 1a, isolated yield of 2a is 92% (condition A) and 89% (condition B); for substrate 1b, isolated yield of 2b is 62% (condition A). dProduct structure is confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis.

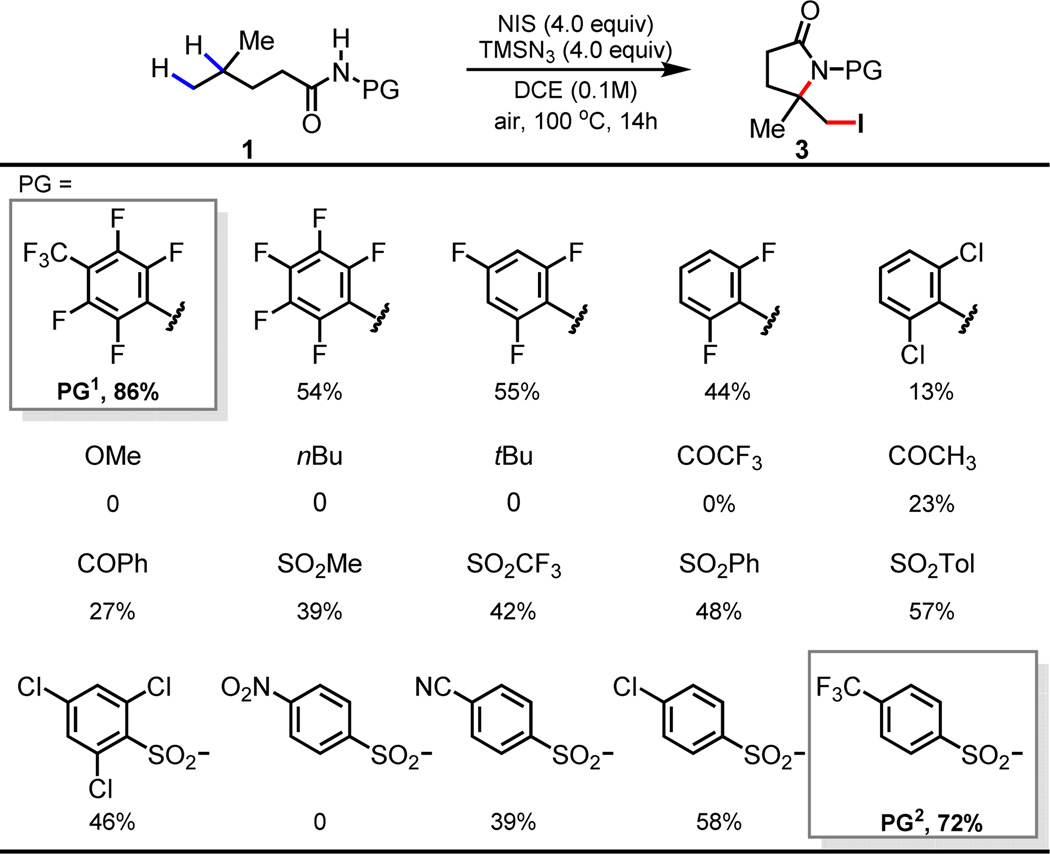

While all efforts to trap the γ-carbon centered radical with various Cu, Pd and Ni catalysts were not fruitful, the attempt to perform a radical γ-azidation led to a surprising finding. In the presence of TMSN3, the reaction of 1a with NIS in DCE afforded δ-iodo γ-lactam 3a in which both γ- and δ-C–H bonds are functionalized (Scheme 1, B). This reactivity was further investigated with a range of amide directing groups. While N-methoxy and N-alkyl amides did not give rise to any product, N-phenyl and N-sulfonyl amides are generally reactive (Table 1). The highly acidic N-heptafluorotolyl (PG1) and the N-para-trifluoromethyl phenylsulfonyl (PG2) amides are more effective affording the δ-iodo γ-lactams in 86% and 72% yields respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

|

Conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), NIS (4 equiv.), TMSN3 (4 equiv.), DCE (1 mL), 100 °C, air, 14 h.

Yields were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture using CH2Br2 as an internal standard.

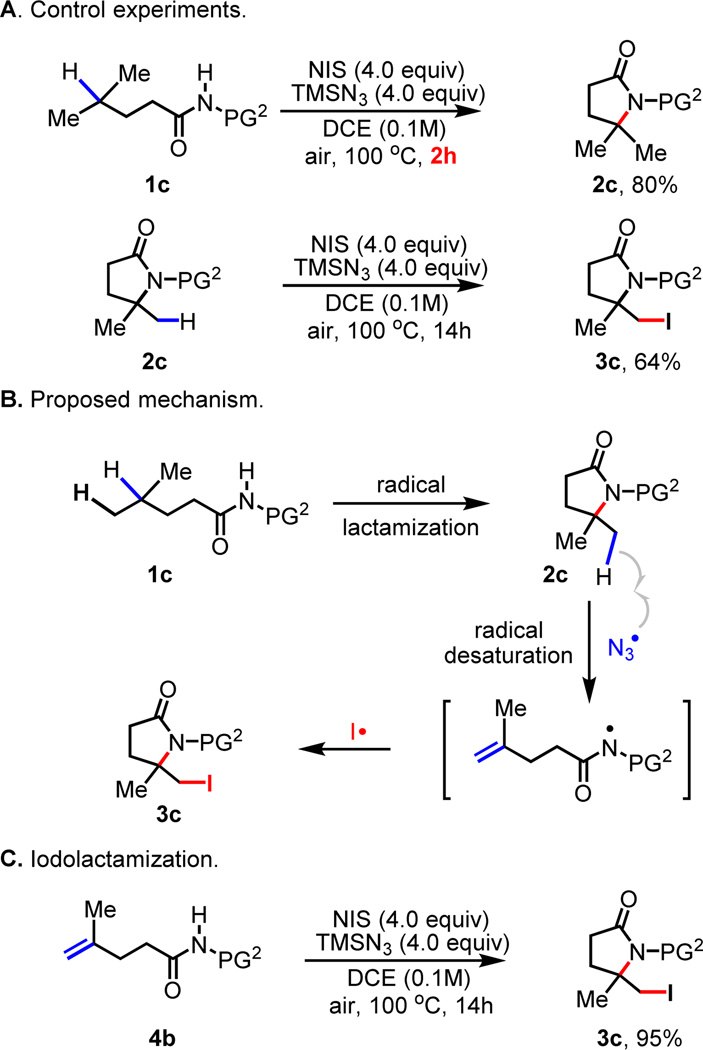

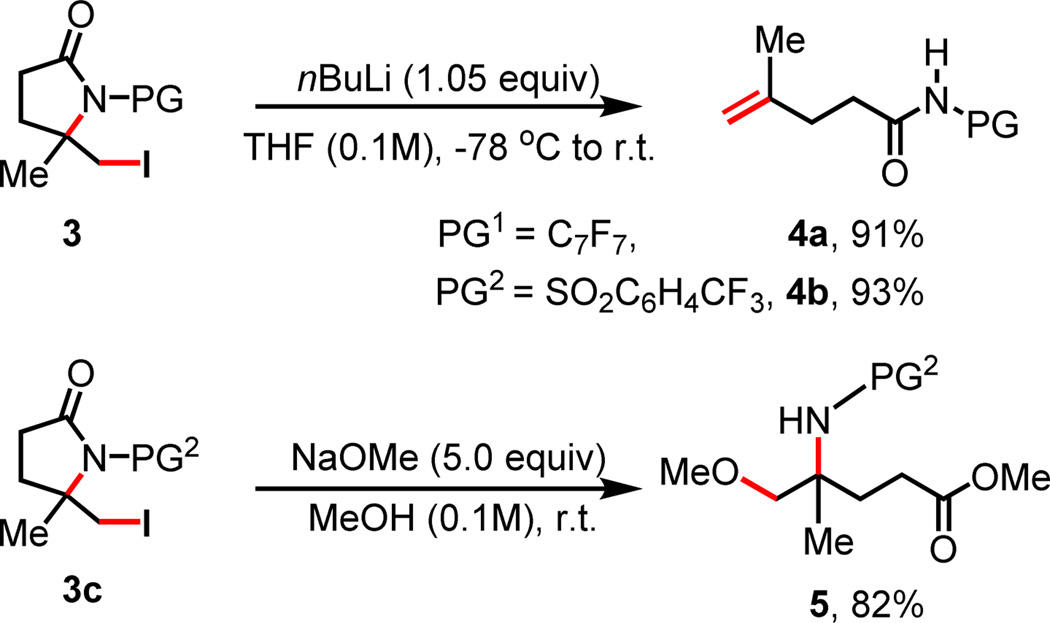

Monitoring the reaction by 1H NMR and isolation of γ-lactam 2c by shortening the reaction to 2 h suggests that 2c is initially formed as the intermediate which then reacts with TMSN3 and NIS to give iodo lactam 3c (Scheme 2, A). Apparently, the in situ generated azide radical7 triggers a β-C–N bond scission to give the terminal double bond and subsequent iodolactamization affords 3c. The iodolactamization step is verified by subjecting a synthetic standard 4b to the reaction conditions to give 3c. Importantly, the iodo lactam 3a and 3b can be converted to γ, δ-desaturated amide 4a and 4b respectively, thus leading to a method for dehydrogenation (Scheme 3).8, 9 In addition, the iodo lactam 3c protected with para-trifluoromethyl phenylsulfonyl group (PG2) is subjected to methanolysis conditions to give 5 containing a synthetically useful 1,2-amino alcohol motif.

Scheme 2.

Preliminary Mechanistic Investigations

Scheme 3.

Synthetic application of δ-iodo γ-lactam 3

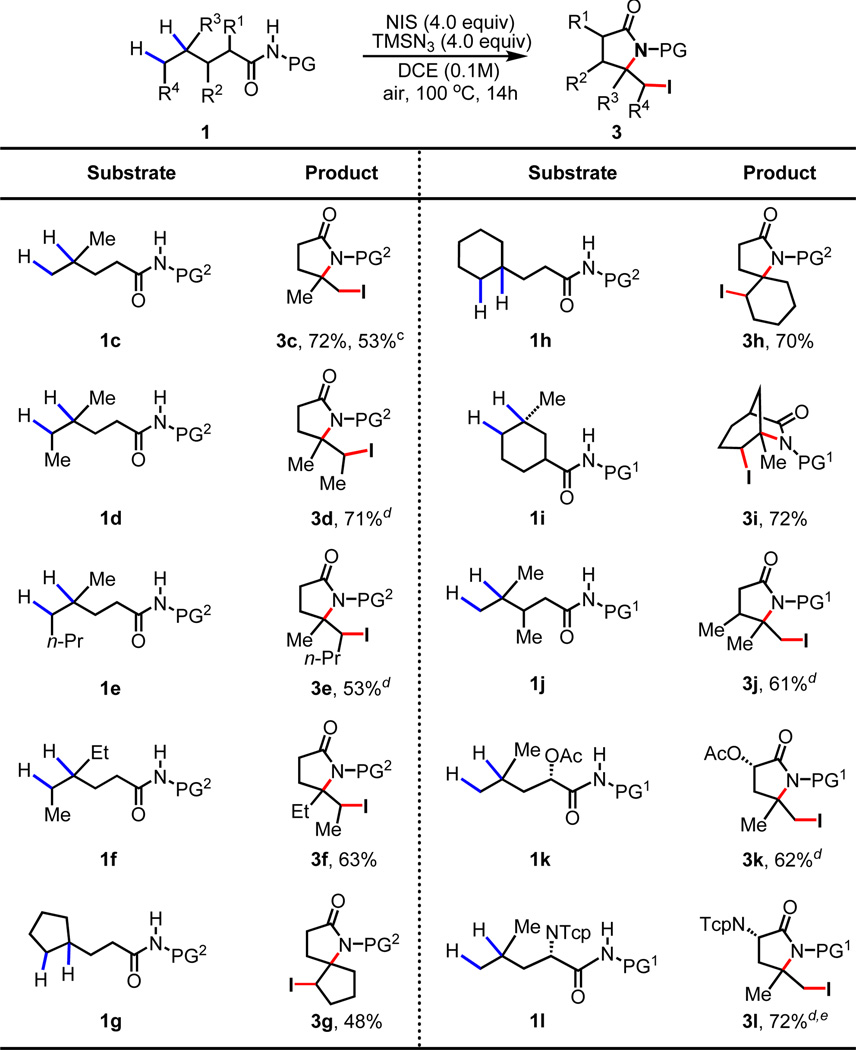

The smooth conversion of the iodo lactam products to more useful olefin and 1,2-amino alcohol motifs prompted us to examine the scope of this transformation. Substrate 1d containing both a methyl and ethyl group at the γ-position was subjected to the reaction conditions. While the first lactamization event is expected to occur selectively at the tertiary carbon center, the subsequent H-abstraction by the azide radical at the δ-carbon center could occur at either methyl or the ethyl group leading to different products. The exclusive formation of 3d (Table 2) containing the newly installed iodide on the methylene carbon suggests that the radical abstraction by the azide radical occurs selectively at the methylene carbon (Scheme 2, B). Similarly, product 3e was obtained with substrate 1e. This method also allows access to synthetically useful iodinated spiro lactams 3g and 3h from 1g and 1h respectively.

Table 2.

|

Conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), NIS (4 equiv.), TMSN3 (4 equiv.), DCE (1 mL), 100 °C, air, 14 h.

Isolated yields.

Run on gram-scale.

Obtained as a mixture of diastereomers (See Supporting Information).

Tcp = tetrachlorophthalimide. One pot procedure for substrate 1l: NIS (2 equiv.), 100 °C, air, 8h; I2 (3 equiv.) and TMSN3 (4 equiv.), 100 °C, 14h.

For substrates containing substituents at the α and β positions, low yields (~40%) were obtained when the para-trifluoromethyl phenylsulfonyl (PG2) protecting group was used. Thus, 1i–1l containing N-heptafluorotolyl (PG1) protecting groups were prepared for testing. We found that the desired bicyclic δ iodo lactam (3i) was formed in 72% yield. Other amides containing methyl, acetoxy and tetrachlorophthalimide at α or β carbons are all compatible, giving the desired products in good yields (3j–3l). Notably, 3l can be converted to γ, δ-unsaturated chiral amino acid, providing a new method to functionalize leucine. Since previous protocols for functionalizing leucine via radical H-abstraction are directed by the amino group,6c, 8 the use of this amide as a directing group in reaction provides a complimentary method to dehydrogenate leucine.

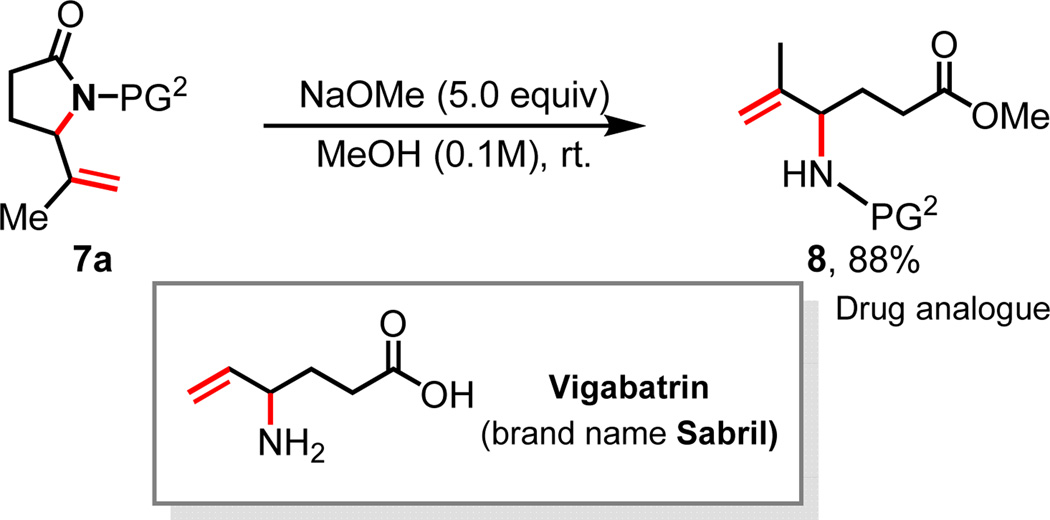

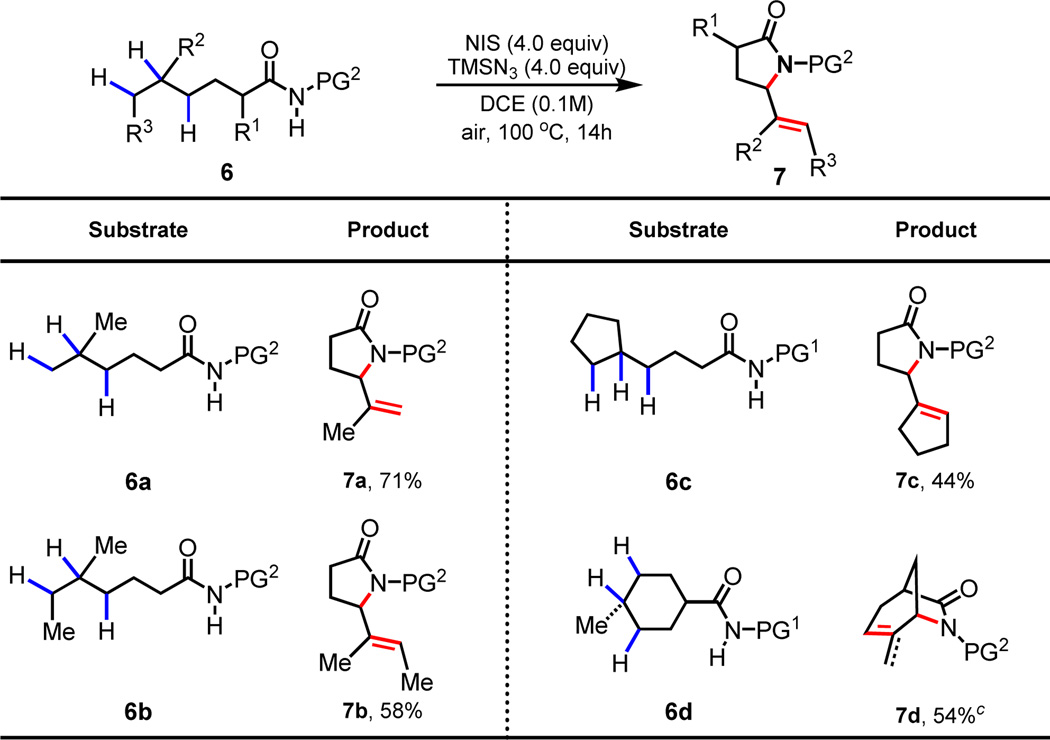

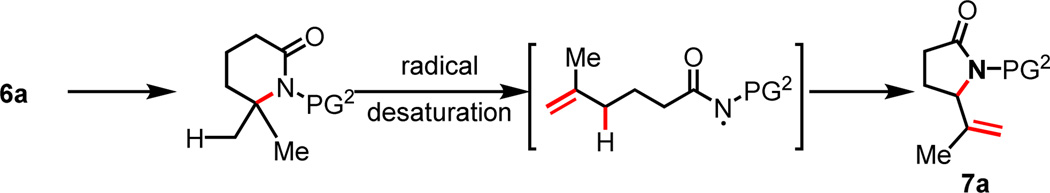

To investigate whether this protocol can be extended to the functionalizations of δ, ε-C–H bonds, we prepared amide substrates 6a–6d containing tertiary C–H bonds at the δ position (Table 3). Interestingly, 6a was converted to δ, ε-dehydrogenated γ-lactam 7a under the standard conditions. Apparently, the olefin intermediate bearing a radical on the nitrogen center derived from the initially formed δ-lactam underwent the facile intramolecular radical abstraction at the allylic carbon center, leading to the cyclization product 7a (Scheme 4). The ε-methylene C–H bond in 6b is selectively functionalized in the presence of the ε-methyl C–H bond. Cyclopentyl (6c) and cyclohexyl (6d) are also compatible, albeit affording lower yields. A minor product derived from the radical abstraction of the ε-methyl C–H bond was also obtained with the cyclic substrate 7d. Importantly, these lactam products can be readily converted to synthetically useful δ, ε-desaturated γ-aminoesters as shown in Scheme 5. For example, 7a is converted to 8, a compound that is closely related to Vigabatrin.

Table 3.

|

Conditions: 6 (0.1 mmol), NIS (4 equiv.), TMSN3 (4 equiv.), DCE (1 mL), 100 °C, air, 14 h.

Isolated yields.

Obtained as a mixture of inseparable mixture of diastereomers (methylene:methyl = 3:1).

Scheme 4.

Proposed Mechanism for the Formation of δ, ε Vinyl Lactams

Scheme 5.

Synthetic Application of δ, ε Vinyl Lactams

In conclusion, we have developed a protocol to functionalize γ, δ, ε-C–H bonds of aliphatic acids via a radical 1,5 and 1,6-H-abstraction. The terminal alkyl groups of aliphatic amides are converted to olefins, amino alcohols or allylic amines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge The Scripps Research Institute and the NIH (NIGMS, 2R01GM084019) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For selected examples: Wang D-H, Wasa M, Giri R, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7190. doi: 10.1021/ja801355s. Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3680. doi: 10.1021/ja1010866. Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3965. doi: 10.1021/ja910900p. Zhang S-Y, Li Q, He G, Nack WA, Chen G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12135. doi: 10.1021/ja406484v. He G, Zhang S-Y, Nack WA, Li Q, Chen G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11124. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305615. Nadres ET, Santos GIF, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:9689. doi: 10.1021/jo4013628. Chen K, Hu F, Zhang S-Q, Shi B-F. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3906. He J, Li S-H, Deng Y-Q, Fu H-Y, Laforteza BN, Spangler JE, Homs A, Yu J-Q. Science. 2014;343:1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1249198. Zhu R-Y, He J, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13194. doi: 10.1021/ja508165a. Xiao K-J, Lin DW, Miura M, Zhu R-Y, Gong W, Wasa M, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8138. doi: 10.1021/ja504196j.

- 2.(a) Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9886. doi: 10.1021/ja903573p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) He J, Wasa M, Chan K, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3387. doi: 10.1021/ja400648w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected examples: Shang R, Ilies L, Matsumoto A, Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:603. doi: 10.1021/ja402806f. Aihara Y, Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:898. doi: 10.1021/ja411715v. Wang Z, Ni J, Kuninobu Y, Kanai M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3496. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311105. Wu X, Zhao Y, Ge H. Chem. Asian J. 2014;9:2736. doi: 10.1002/asia.201402510.

- 4.(a) He G, Zhang S-Y, Nack WA, Li Q, Chen G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11124. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li S-H, Chen G, Feng C-G, Gong W, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5267. doi: 10.1021/ja501689j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selected examples of 1,5 and 1,6-H-abstraction initiated by an oxygen radical: Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:2640. Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:4076. Mihailovic ML, Miloradovic M. Tetrahedron. 1966;22:723. Concepcion JI, Francisco CG, Hernandez R, Salazar JA, Suarez E. Tetrahendron Lett. 1984;25:1953. Francisco CG, Herrera AJ, Suarez E. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:7439. doi: 10.1021/jo026004z. Zhu H, Wickenden JG, Campbell NE, Leung JCT, Johnson KM, Sammis GM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2019. doi: 10.1021/ol900481e. Kundu R, Ball ZT. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2460. doi: 10.1021/ol100472t.

- 6.Selected examples of 1,5 and 1,6-H-abstraction initiated by a nitrogen radical: Corey EJ, Hertler WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:1657. Togo H, Hoshina Y, Muraki T, Nakayama H, Yokoyama M. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5193. Reddy LR, Reddy BVS, Corey EJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2819. doi: 10.1021/ol060952v. Francisco CG, Herrera AJ, Martin A, Perez-Martin I, Suarez E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:6384. Fan R, Pu D, Wen F, Wu J. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8994. doi: 10.1021/jo7016982. Chen K, Richter JM, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7247. doi: 10.1021/ja802491q.

- 7.(a) Magnus P, Lacour J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:767. [Google Scholar]; (b) Marinescu LG, Pedersen CM, Bols M. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:123. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pedersen CM, Marinescu LG, Bols M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:816. doi: 10.1039/b500037h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chouthaiwale PV, Suryavanshi G, Sudalai A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6401. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voica AF, Mendoza A, Gutekunst WR, Fraga JO, Baran PS. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:629. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giri R, Maugel NL, Foxman BM, Yu J-Q. Organometallics. 2008;27:1667. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.