LETTER

We describe herein the characterization of a novel class 1 integron harboring the blaIMP-10 gene in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. The imipenem resistance rates in A. baumannii increased from 12.6% to 71.4% in Brazilian centers between 1997 to 1998 and 2008 to 2010 (1). The increase was associated mainly with the spread of clonally related OXA-23-producing A. baumannii isolates and, to a lesser extent, with the spread of OXA-143-producing A. baumannii isolates that may represent diverse clonal lineages (2, 3). In contrast, IMP-1-producing A. baumannii isolates have been restricted to a few hospitals located in the São Paulo state (4, 5).

Two carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates were recovered from blood (Acb3035) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Acb3101) cultures of distinct patients admitted to the pneumology unit of a tertiary-care teaching hospital located in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, in August 2000. The clinical specimens were collected 3 days apart. The species identification was confirmed by rpoB sequencing (6). Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by CLSI broth microdilution (7), except that for tigecycline, which was determined by Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The two A. baumannii isolates were resistant to ampicillin-sulbactam (MICs, 32/16 μg/ml), ceftriaxone (MICs, 256 μg/ml), ceftazidime (MICs, 32 μg/ml), cefepime (MICs, 128 μg/ml), imipenem (MICs, 32 μg/ml), meropenem (MICs, 64 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (MICs, 2 μg/ml), amikacin (MICs, 128 μg/ml), and gentamicin (MICs, 64 μg/ml). In contrast, both isolates were susceptible to polymyxin B (MICs, 1 μg/ml) and minocycline (MICs, 0.5 μg/ml) but showed high MICs of tigecycline (MICs, 4 μg/ml) (8).

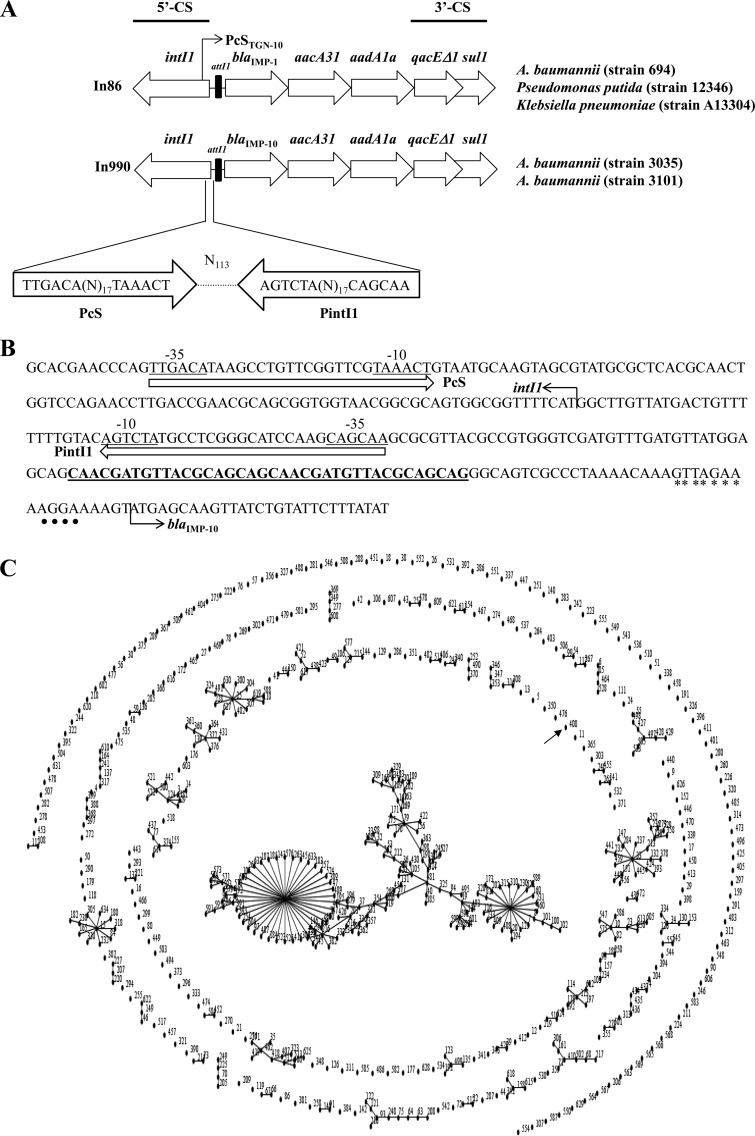

The presence of β-lactamase genes was investigated by PCR followed by DNA sequencing using specific primers (9, 10). Both A. baumannii isolates carried the blaIMP-10, blaOXA-100 (a blaOXA-51-like gene), and blaTEM-1 genes. The sequencing of blaIMP-10 genetic context (5, 11) showed that blaIMP-10 was harbored by a new class 1 integron designated In990 (GenBank accession number KP177455) (Fig. 1A). The In990 5′ coding sequence (5′-CS) was composed of intI1, the attI1 recombination site, and a promoter region constituted by a PcS promoter ([TTGACA](N)17[TAAACT]) (Fig. 1B). The first gene cassette of In990 was blaIMP-10, followed by two aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme-encoding genes (aacA31 and aadA1a) and the qacEΔ1 and sul1 genes at the 3′-CS. The cassette arrangement of In990 was very similar to that of In86, which carries blaIMP-1 in the Gram-negative bacilli, including A. baumannii, isolated within the same period of time and at the same institution (4, 5, 12) (Fig. 1A). However, a rare variation of PcS, PcSTGN-10, was found in In86 (5), and a 19-bp duplication (CAACGATGTTACGCAGCAG) upstream of ORF11 was observed only in In990 (Fig. 1B). ORF11 encodes a 12-amino-acid peptide because a stop codon was created at the very beginning of the first gene cassette (13). Although the 19-bp duplication resulted in a suppression of this stop codon, another stop codon is present at the junction with the coding sequence of blaIMP-10. Such duplication might affect the translation level of blaIMP-10 since this gene already displays a well-conserved ribosomal binding site. Southern blotting/hybridization experiments revealed that the blaIMP-10 gene was located on a plasmid of ∼146 kb in both isolates (14). Conjugation experiments failed to transfer blaIMP-10 (15). The clonal relatedness of the two IMP-10-producing A. baumannii isolates was assessed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the ApaI restriction enzyme as described previously (16) and revealed that the two strains were identical. Multilocus sequencing typing (MSLT) was performed according to the Institut Pasteur scheme (17). Both the Acb3035 and Acb3101 strains belonged to the new sequence type, 400 (ST400), which is not related to those of main clonal complexes known to have spread worldwide (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

(A) Comparison of class 1 integrons In86 and In990, carrying blaIMP-1 (5, 12) and blaIMP-10, respectively, in different Brazilian Gram-negative bacillus isolates. Arrows designate transcription directions of genes. The figure is not to scale. (B) Schematic representation of partial nucleotide sequence of the 5′-CS region, from the Pc promoter to the beginning of blaIMP-10. The 19-bp duplication upstream of ORF11 is shown in bold. The asterisks show the end of attI1, the integron-associated recombination site recognized by IntI1. The black circles show the Shine-Dalgarno sequence. (C) Clustering of IMP-10-producing A. baumannii STs (MLST) by eBurst (http://eburst.mlst.net/), with 634 MLST profiles representing 634 isolates from the database (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/; last accessed 12 November 2014). ST400, determined for the studied isolates, is indicated by a black arrow.

Initially reported in 1997 (18), blaIMP-10 has been harbored by distinct integrons in Gram-negative bacilli, especially in Japan (18, 19). Hu and Zhao reported Serratia marcescens isolates carrying blaIMP-1 or blaIMP-10 genes in class 1 integrons with identical cassette arrangements (19), which is similar to our findings. IMP-10 differs from IMP-1 by a single base replacement of G→T at nucleotide 145, leading to the amino acid substitution Val49Phe and a change to a β-lactam hydrolysis profile. Previous studies demonstrated that IMP-10, in comparison with IMP-1, lacks activity against extended-spectrum penicillins, the fourth-generation cephalosporin cefpirome, and monobactams but that it kept its activity against third-generation cephalosporins, cefepime, and carbapenems (19, 20). However, in the studied A. baumannii isolates, this phenotype was masked by the overexpression of blaADC and blaOXA-100 by ISAbaI.

This work describes a new class 1 integron, In990, harboring blaIMP-10 and reports for the first time, to our knowledge, IMP-10 among A. baumannii isolates. The natural occurrence of blaIMP-10 seems to be inherently associated with previous blaIMP-1 spread in the nosocomial environment, since both genes, in general, share the same backbone integrons. The events that promote the selection of blaIMP-10 are still unknown but may have been influenced by antibiotic pressure exerted by a patient's therapy or local prescribing antibiotic practices.

(This work was presented in part as an oral presentation [O078] at the 24th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases-ECCMID in Barcelona, Spain, in 2014.)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Virginie Passet from the Institut Pasteur for kindly helping with the MLST analysis. We also thank Lorena C. C. Fehlberg, Willames M. B. S. Martins, Graziela Braun, and Kesia E. da Silva for their excellent technical contributions to the manuscript.

This study was supported by internal funding. We are grateful to the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and the National Council for Science and Technological Development (CNPq) for providing grants to R.C. (process number 2012/15459-6) and to A.C.G. (process number 307816/2009-5), respectively. A.C.G. has recently received research funding and/or consultation fees from AstraZeneca, MSD, Novartis, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and bioMérieux. The other authors have nothing to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS. 2012. Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008-2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chagas TP, Carvalho KR, de Oliveira Santos IC, Carvalho-Assef AP, Asensi MD. 2014. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Brazil (2008-2011): countrywide spread of OXA-23-producing clones (CC15 and CC79). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79:468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werneck JS, Picão RC, Girardello R, Cayô R, Marguti V, Dalla-Costa L, Gales AC, Antonio CS, Neves PR, Medeiros M, Mamizuka EM, Elmor de Araújo MR, Lincopan N. 2011. Low prevalence of blaOXA-143 in private hospitals in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4494–4495. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00295-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gales AC, Tognim MC, Reis AO, Jones RN, Sader HS. 2003. Emergence of an IMP-like metallo-enzyme in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain from a Brazilian teaching hospital. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 45:77–79. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(02)00500-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendes RE, Castanheira M, Toleman MA, Sader HS, Jones RN, Walsh TR. 2007. Characterization of an integron carrying blaIMP-1 and a new aminoglycoside resistance gene, aac(6′)-31, and its dissemination among genetically unrelated clinical isolates in a Brazilian hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2611–2614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00838-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Scola B, Gundi VA, Khamis A, Raoult D. 2006. Sequencing of the rpoB gene and flanking spacers for molecular identification of Acinetobacter species. J Clin Microbiol 44:827–832. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.827-832.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically, 9th ed Approved standard M7-A9 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 24th ed Informational supplement M100-S24 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes RE, Kiyota KA, Monteiro J, Castanheira M, Andrade SS, Gales AC, Pignatari AC, Tufik S. 2007. Rapid detection and identification of metallo-beta-lactamase-encoding genes by multiplex real-time PCR assay and melt curve analysis. J Clin Microbiol 45:544–547. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01728-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins PG, Lehmann M, Seifert H. 2010. Inclusion of OXA-143 primers in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes RE, Toleman MA, Ribeiro J, Sader HS, Jones RN, Walsh TR. 2004. Integron carrying a novel metallo-beta-lactamase gene, blaIMP-16, and a fused form of aminoglycoside-resistant gene aac(6′)-30/aac(6′)-Ib': report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4693–4702. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4693-4702.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penteado AP, Castanheira M, Pignatari AC, Guimarães T, Mamizuka EM, Gales AC. 2009. Dissemination of bla(IMP-1)-carrying integron In86 among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring a new trimethoprim resistance gene dfr23. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 63:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanau-Berçot B, Podglajen I, Casin I, Collatz E. 2002. An intrinsic control element for translational initiation in class 1 integrons. Mol Microbiol 44:119–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieser T. 1984. Factors affecting the isolation of CCC DNA from Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Plasmid 12:19–36. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(84)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werneck JS, Picão RC, Carvalhaes CG, Cardoso JP, Gales AC. 2011. OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Brazil: a case report. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:452–454. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert H, Dolzani L, Bressan R, van der Reijden T, van Strijen B, Stefanik D, Heersma H, Dijkshoorn L. 2005. Standardization and interlaboratory reproducibility assessment of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-generated fingerprints of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol 43:4328–4335. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4328-4335.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Brisse S. 2010. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One 5:e10034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Z, Zhao WH. 2009. Identification of plasmid- and integron-borne blaIMP-1 and blaIMP-10 in clinical isolates of Serratia marcescens. J Med Microbiol 58:217–221. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.006874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyobe S, Kusadokoro H, Takahashi A, Yomoda S, Okubo T, Nakamura A, O'Hara K. 2002. Detection of a variant metallo-beta-lactamase, IMP-10, from two unrelated strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an Alcaligenes xylosoxidans strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:2014–2016. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.2014-2016.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao WH, Hu ZQ, Shimamura T. 2008. Potency of IMP-10 metallo-beta-lactamase in hydrolysing various antipseudomonal beta-lactams. J Med Microbiol 57:974–979. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/001388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]