Abstract

Significance: Large variation and many controversies exist regarding the treatment of, and care for, acute wounds, especially regarding wound cleansing, pain relief, dressing choice, patient instructions, and organizational aspects.

Recent Advances: A multidisciplinary team developed evidence-based guidelines for the Netherlands using the AGREE-II and GRADE instruments. A working group, consisting of 17 representatives from all professional societies involved in wound care, tackled five controversial issues in acute-wound care, as provided by any caregiver throughout the whole chain of care.

Critical Issues: The guidelines contain 38 recommendations, based on best available evidence, additional expert considerations, and patient experiences. In summary, primarily closed wounds need no cleansing; acute open wounds are best cleansed with lukewarm (drinkable) water; apply the WHO pain ladder to choose analgesics against continuous wound pain; use lidocaine or prilocaine infiltration anesthesia for wound manipulations or closure; primarily closed wounds may not require coverage with a dressing; use simple dressings for open wounds; and give your patient clear instructions about how to handle the wound.

Future Directions: These evidence-based guidelines on acute wound care may help achieve a more uniform policy to treat acute wounds in all settings and an improved effectiveness and quality of wound care.

Dirk T. Ubbink, MD, PhD

Scope and Significance

For chronic wounds, such as venous, arterial, pressure, and diabetic foot ulcers, several (inter)national guidelines are available.1 For wounds with an acute etiology, fewer guidelines exist. Still, an undesirable inconsistency in wound care practice is evident from the huge number of wound dressings available, the large number of caregivers involved, and the many opinions regarding optimum wound care.2 This calls for more evidence-based and more uniform care to avoid undesired variation in care.

Translational Relevance

In terms of translational research, available guidelines have focused on diminishing barriers for wound healing given certain comorbid conditions,3 or have described inconsistencies in the documentation of surgical wound care according to existing guidelines, mainly regarding the prevention and treatment of surgical site infections, which hamper interdisciplinary communication.4

Clinical Relevance

Current clinical guidelines on acute wound care comprise the CDC guideline, 1999; the NICE clinical guideline 74, 2008; the SQuIRe 2 CPI Guide, 2009; the EWMA Position Statement (2006); and the AWMA Standards (2011).4 Most of these guidelines have become outdated. This article describes the development of relevant guidelines for all medical and nursing professionals and stakeholders involved in wound care in any care setting, and summarizes the most noticeable and practical recommendations in five areas: wound cleansing, pain relief, dressing choice, patient instructions, and organizational aspects.

Overview

The present guidelines were developed to provide advisable and practical options for acute-wound care to promote more uniformity, effectiveness, and quality in the care for acute wounds after surgery or trauma. Guidelines development started in January 2012. The first draft of the guidelines was produced in February 2013. Feedback from the reviewers was collected and incorporated in the guidelines in July 2013. The final guidelines were authorized by all contributing professional societies in November 2013.

The development was conducted in the Netherlands along the AGREE-II instrument,5 and by involving all relevant professional societies in a working group (the members are stated in “Acknowledgments” section). We also made an inventory of experiences of patients treated for their acute wounds in the emergency room. This has been instrumental to incorporate their insights and preferences in the recommendations of this guideline.

First, the expert members of the working group made an inventory of the most common controversies in clinical practice. Input for this inventory came from the results of calls in Dutch nursing journals and during a nursing conference to submit important issues as perceived by caregivers in the field. Next, the working group scored the urgency and significance of these controversies. The five highest-scoring topics were chosen to address in this guideline.

Evidence for each topic was derived from a systematic review of the literature and judged using the GRADE method.6 Preferably, studies that focused on validated, patient-relevant outcomes were used. The resulting conclusions were presented to the members of the working group to formulate recommendations based on the evidence and other professional, practical, cost, or patient-related considerations.

The concept guidelines have been scrutinized by 18 independent members of 12 professional societies, not necessarily participating in the working group. The working group has considered and incorporated these remarks in the final version.7 The guidelines were subsequently authorized by the participating professional societies and were added to their official Web sites. The guidelines were initiated by the Dutch Surgical Society, who will decide about an update not later than in 2019. A summary of the five most important issues has been used for the Dutch “Choosing Wisely” campaign (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Critical directions from the guidelines, as summarized in the Dutch “Choosing wisely” campaign. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Discussion

The guidelines contain a total of 38 recommendations, based on best available evidence, additional expert considerations, and patient experiences.8 A full listing of the recommendations is given in Table 1. The strength of the evidence is expressed according to the GRADE classification,5 including high-, moderate-, low-, and very-low-quality evidence. In the absence of evidence, the expert opinion of the working group (WG) was adopted.

Table 1.

Overview of the recommendations

| Wound cleansing and antisepsis |

| 1. The cleansing of primarily closed wounds is dissuaded. |

| 2. Dirty open wounds (street, bite, or cut wound) should be cleansed. |

| 3. If a wound needs cleansing, then drinkable tap water suffices. This should be applied in a patient-friendly way using lukewarm water and a gentle squirt. |

| 4. The use of disinfectants to cleanse acute wounds is dissuaded. |

| 5. Bathing of wounds in whatever solution, even water, should not be part of wound cleansing. |

| Pain control |

| 6. Consider psychosocial, local, and systemic forms of analgesic treatment. |

| 7. Use the WHO pain ladder when considering a systemic analgesic treatment. Any prescription should be in agreement with the patient's preference. |

| 8. The use of NSAID-containing dressings to treat continuous wound pain is dissuaded. |

| 9. Lidocaine or prilocaine is considered the first-choice drug to avoid acute-wound pain during manipulation or surgical closure. |

| 10. Lidocaine or prilocaine should preferably be administered as infiltration anesthesia. |

| 11. EMLA® cream should be applied for indications as defined in the instruction leaflet: intact skin, genital mucosa, or crural ulcers. |

| 12. When the patient is afraid of needles, lidocaine or prilocaine might be administered cutaneously, but be aware of the time to take effect (30–45 min). |

| 13. Mild and moderate pain (VAS or NRS score between 1 and 6) can best be treated with paracetamol and an NSAID. |

| 14. In high-risk patients (e.g., above 70 years of age) the prescription of NSAIDs is dissuaded. |

| 15. If the first two steps of the WHO ladder do not suffice to treat moderate-to-severe pain (VAS or NRS score between 3 and 7), then use a strong-acting opioid (step 3). |

| 16. Prescribe only one strong-acting opioid per healthcare institution and carry a limited range of these opioids in stock. |

| Instructions to the patient |

| 17. The application of wound dressings on primarily closed wounds is dissuaded. A dressing may be considered |

| a. To absorb exudate or transudate. |

| b. In case the patient prefers this, after being informed it will not prevent a wound infection and may hurt when being removed or changed. |

| 18. Showering the wound area (for <10 min) is allowed 24 h after surgical wound closure in a hospital, if the patient wishes to do so. |

| 19. If there is a prosthesis beneath the wound, then showering the wound area (for <10 min) is allowed after 48 h if there are no signs of infection and the treating surgeon agrees. |

| 20. The treating surgeon should instruct patients about when and how to mobilize. This may depend on the patient's preference, location of the wound, healing progress, and type of surgery performed. |

| 21. Patients should be advised to protect superficial wounds (e.g., grazes) against exposure to ultraviolet light for at least 3 months. |

| Wound care materials |

| 22. Covering a primarily closed wound using a simple dressing material is indicated only in case of wound leakage, to protect against adherence of the wound to clothes, or if the patient so wishes, for example, when he does not want to see the wound. |

| 23. For wounds healing by secondary intention, a nonadhesive dressing should be applied. The choice of dressing should be determined by the patient's circumstances (e.g., change frequency, leakage, or pain). |

| 24. For donor-site wounds after split-skin grafting, a hydrocolloid is advised to promote wound healing, while a film dressing is a good alternative. |

| 25. A locally infected wound may be treated with iodine or honey, after adequate cleansing. As none of the antiseptics excels, iodine or honey is recommended. The choice may be based on product availability, experience with and knowledge about the product, and their discerning characteristics. |

| 26. In future studies on antiseptics, iodine or honey should be one of the study arms. |

| 27. Leaking wounds deserve an absorbing dressing that is changed depending on the amount of exudate. Additional absorbing capacity is required when leakage is expected to be substantial or when demanded by the patient's circumstances. |

| 28. Prolonged or substantial leakage also calls for exploration of its cause. |

| 29. In bite wounds, a nonadhesive or absorbing dressing is advised. Small bite wounds may dry and heal uncovered. |

| 30. Patients with bite wounds should be instructed about signs of infection. |

| 31. Superficial, nonleaking grazes may not need a dressing or be covered with paraffin or a plaster. Consider using an (semi) occlusive dressing if the wound is painful. |

| 32. Leaking grazes may be covered with a nonadhesive dressing (paraffin gauze or silicone dressing) and an absorbing dressing. |

| 33. Skin tears and flap wounds should be covered, after appropriate cleansing and fixation of the detached skin, with a nonadhesive dressing, which should preferably not be changed within 7 days. If a skin flap is resected, then a nonadhesive dressing should be used that should remain in situ as long as possible. |

| Organization of acute-wound care |

| 34. To classify the status of the wound, the Red-Yellow-Black scheme can be used, including the assessment of the wound moistness (wet, moist, or dry). |

| 35. In addition to the RYB scheme, the TIME model is recommended to facilitate a uniform and systematic wound care policy. |

| 36. To ensure continuity in the chain of care, the following wound care aspects are vital to be recorded in writing, preferably by a wound care specialist, and to be handed over in case of referral. |

| a. Wound characteristics |

| b. Patient characteristics (e.g., comorbidity) |

| c. Diagnosis and treatment plan |

| d. Goals to be reached |

| e. Tasks and responsibilities of caregivers involved |

| f. Indications when to refer and to whom |

| g. Who has performed the treatment and who is responsible |

| 37. Drugs for patients with acute wounds may be prescribed by physicians, nursing specialists, or physician assistants, according to prevailing legislation. |

| 38. The wound care policy should only be performed by qualified and capable professionals. |

Which wounds should be cleansed and how?

• Wounds that are closed under aseptic conditions do not require further cleansing and disinfection, because available evidence shows that this does not lead to lower infection rates (moderate),7 but does cost time and money (WG).

• Cleanse open wounds healing through secondary intention with drinkable tap water (moderate),8 if contaminated (e.g., street wounds, bite wounds, or cut wounds) in a patient-friendly way using lukewarm water, by means of gentle irrigation (WG). Only after adequate cleansing and in a later stage of wound healing can antiseptics like (povidone-)iodine or honey be useful for locally infected wounds (WG). The use of disinfectants is dissuaded (low),9,10 particularly the bathing of feet or hands in detergents (e.g., soda, washing powder, or shower gel), as it macerates the skin, fosters infection, delays healing, and encumbers the patient (WG).

How to treat wound pain?

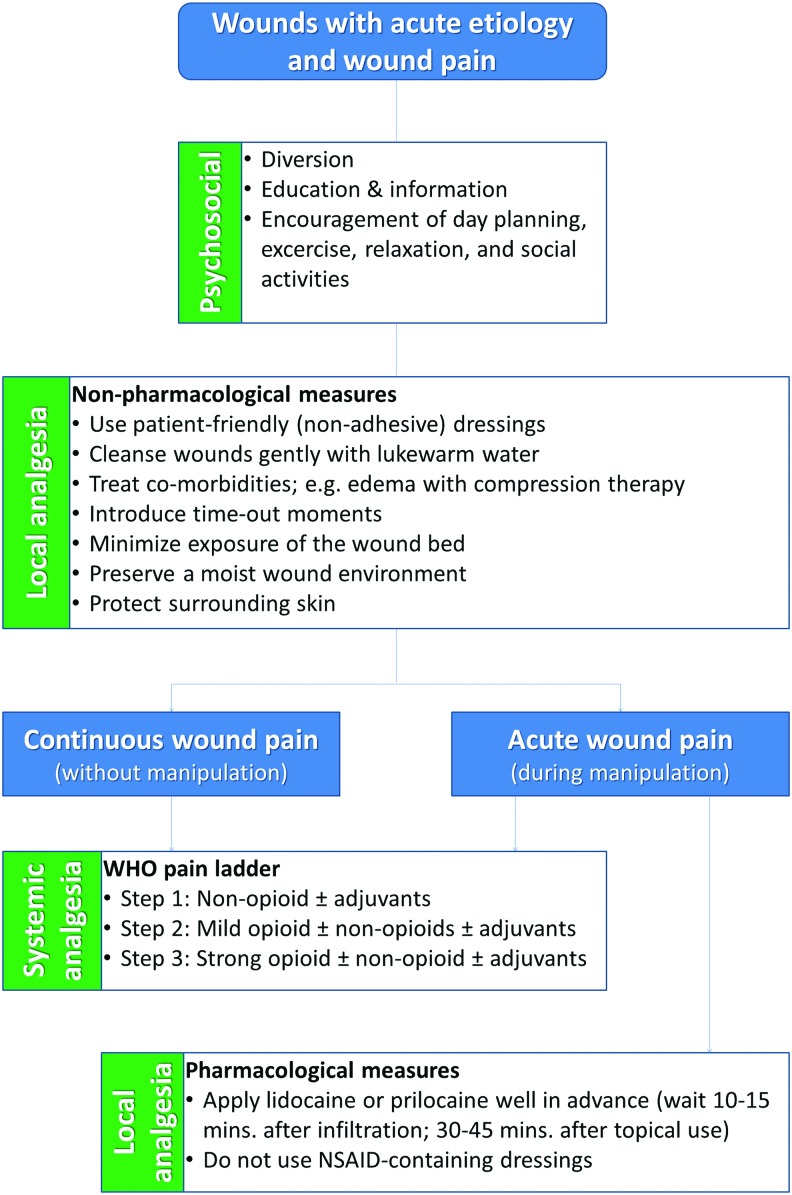

• Wound-related pain among children and adults is an underestimated complaint that may occur irrespective of whether the wound is being manipulated, and should therefore receive specific attention (Fig. 2). This can be done through psychosocial (distraction, explanation, relaxation, and time-outs) and topical treatments and/or systemic analgesics (WG).11

• Apply infiltration anesthesia with lidocaine or prilocaine. Topical application is an alternative if the patient is afraid of needles, but the time before it takes effect has to be considered (30–45 min) (low).11 EMLA® cream is recommended only when applied following the official instructions, that is, on intact skin or venous ulcers (WG). Do not use nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–containing dressings as their effectiveness has not been shown and they are costly and may cause side effects (moderate).12

• Treat mild and moderate pain (VAS scores between 1 and 6) during dressing changes with paracetamol or NSAIDs (high),13 but be cautious when prescribing NSAIDs for patients >70 (WG). Moderate or severe pain (VAS scores 3–10) should be treated with opioids, such as morphine or fentanyl (high).13

• Use the WHO pain ladder to choose a suitable analgesic to treat pain between dressing changes (WG).14 This should be decided in consultation with the patient (WG).

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing the various options for analgesic treatment of wound pain. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

What wound dressing material for which wound?

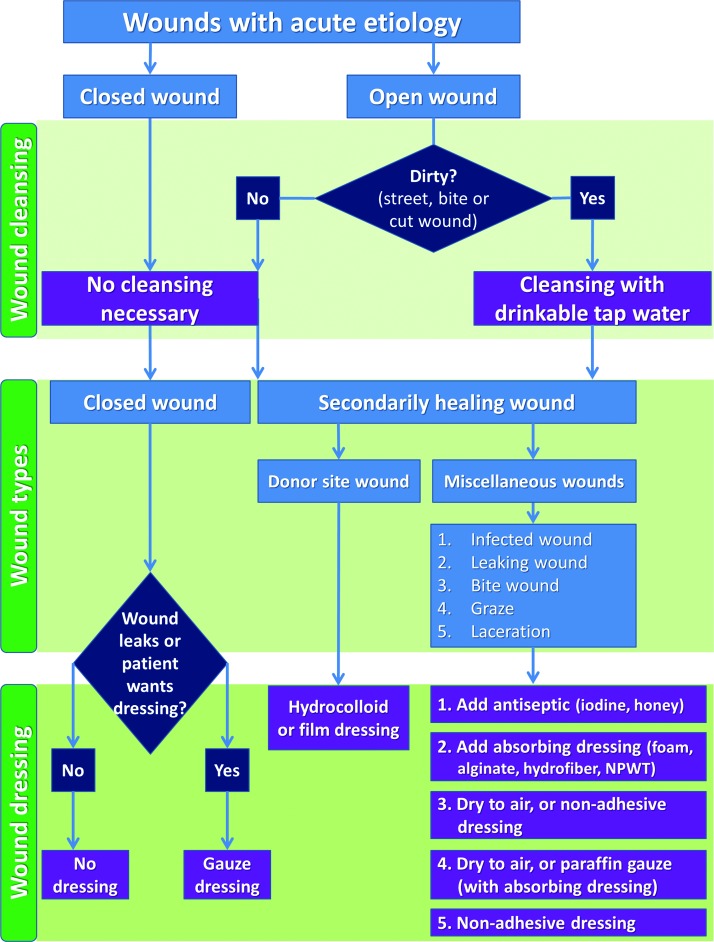

• In general, the best dressing choice should depend on wound characteristics and be acceptable to patients (Fig. 3). Their preference may be determined by not wanting to see the wound, dressing-change frequency, pain-free dressing changes, leakage, adherence of the wound to clothes, and so on (WG). Besides, the choice depends on various dressing features, for example, absorption capacity, adherence, occlusiveness, caregiver dependency, cost effectiveness, reimbursement issues, and experience with the product (WG).

• Leave a closed, dry wound uncovered because covering does not reduce the infection risk, while dressing changes can be painful.15–18 A wound dressing may be used to absorb wound fluid or blood and if desired by the patient, for example, to avoid friction with clothes. A conventional nonadhesive gauze dressing or plaster usually suffices for this purpose and saves costs (WG).

• Apply a nonadhesive (silicone or paraffin gauze) dressing to secondarily healing wounds (low), as these are most suitable in terms of wound healing time, infection risk, and pain.11,19 Small or superficial acute wounds may dry uncovered (WG). The dressing choice should depend on the circumstances of the patient and wound (change frequency, leakage, and pain) (WG). Leaking wounds may need more absorbing products or devices (foam, alginate, hydrofiber, or negative-pressure wound therapy). When leakage is substantial, its cause should be investigated (WG).

• Use a hydrocolloid dressing to cover donor site wounds after split-skin grafting, or a film dressing as second best choice (moderate).20

• A nonadhesive dressing should be used for skin tears or skin flap wounds, only after proper cleansing and fixation (WG). The dressing should remain in situ for at least 7 days. If a skin flap has been removed, then a nonadhesive dressing can be applied and remain there for as long as possible (WG).

Figure 3.

Flow chart showing the various cleansing, dressing, and topical agent options for acute-wound care. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

How should patients be instructed to take care of their wound?

• Instruct patients about what to expect regarding normal wound healing as well as alarm symptoms, that is, signs of infection or complications (WG).

• Provide patients with the name(s) and address(es) of the contact person(s) they can reach in case of questions or problems (WG).

• Briefly showering the wound or bathing is allowed, if the patient wishes, within 12 h after wound closure in the primary care setting (moderate),21 after 24 h in the hospital setting (moderate),7 and after 48 h in case of underlying prosthetic material if the treating surgeon agrees (WG). This does not increase the infection risk. Longer showering or bathing (>10 min) unnecessarily increases the risk of skin maceration.

• Surgeons should instruct their own patients regarding when and how to mobilize (WG). This is determined by the wound location, the expected healing tendency, the performed procedure, as well as the patient's preference and ability to mobilize.

• Superficial acute wounds (e.g., grazes) may best be protected against ultraviolet light exposure for at least 3 months to avoid pigmentation differences and impairment of wound healing (WG).22,23

How can the organization of the chain of wound care be improved?

• When a patient is referred from one healthcare professional to another, at least the following items should be communicated to ensure optimum continuity of care: wound characteristics, healing progress, patient characteristics and comorbidity, treatment plan, and goals to be reached (WG).

• A standard wound classification scheme should be used (e.g., Red-Yellow-Black and TIME) (WG).24,25

• It should be made clear to patients and colleagues who carries the responsibility for diagnostic and therapeutic actions and how to contact this person (WG).

• These items should preferably be documented by using a uniform handover form (WG).

Implementation

The guidelines were developed in the Netherlands by all relevant stakeholders in wound care, including healthcare insurers. The relevant evidence available worldwide was merged with considerations of applicability, generalizability, and patient preferences to answer critical issues in clinical practice. The guideline's relevance lies in offering a document with a more uniform policy for the treatment of acute wounds in all settings by all caregivers involved, to improve the effectiveness and quality of wound care. The guidelines may also be useful as a primer for other countries to formulate their own, adapted to their local context, for example, by using the ADAPTE instrument.26

Acute wounds form a frequent, global disorder with global controversies. A huge number of dressing materials is available within the European territory. Invariably, the organization of care is multidisciplinary in every country. Hence, (most of) the recommendations are likely to be applicable in many other countries as well.

The guidelines were highly desired because of the existence of a large, undesirable variation in care, the large number of care professionals involved, wound care products available, and patients in different settings who are confronted with acute wounds, that is, after surgery or trauma. The current undesirable practice variation seems due to the wide range of healthcare professionals involved in wound care and the countless wound care products marketed by many manufacturers over the last decades. Also, the current strength of the evidence base in wound care shows room for improvement.27,28 These circumstances hamper guideline implementation.

To facilitate guideline uptake we involved representatives of virtually all relevant Dutch medical and nursing professional societies, as well as the national association of healthcare insurers, who joined forces to develop and implement this guideline. Apart from these professional societies, also the Dutch Societies of Paediatric Surgeons and Wound Care Professionals have provided feedback on the concept guideline. We recommended a multifaceted implementation strategy comprising electronic decision support, audit and feedback loops, and local opinion leaders to effectively change today's behavior of all wound care professionals.29 The current implementation and application in local protocols will generate more feedback that will help fine-tuning future updates of the guideline.

Limitations

As limitations of this guideline development project, the guidelines obviously could not possibly encompass all issues involved in wound care. Other relevant but lower-scoring topics—for example, when to apply wet dressings or antibiotics, the best treatment of a fingertip trauma, the value of skin glue or negative-pressure wound therapy, and scar prevention—were documented to be included in future updates of the guideline. In the next update, an inventory should be made anew of critical issues to be addressed at that time.

Second, the guidelines were developed in a single country. Therefore, not all of the recommendations may be applicable or acceptable to other (even European) countries. In fact, even in the Netherlands, some recommendations are being accepted reluctantly, despite the acknowledged importance of such a document. Some old habits die hard. However, this holds for many other guidelines published in medical journals or clearinghouses on the Internet. The recommendations are supported by evidence from international publications, as well as by general medical and surgical principles. Even though not acceptable as a blanket policy standard, the guidelines presented here will hopefully at least be useful as a resource for national guidelines and local protocols anywhere.

Summary

An undesirable inconsistency in wound care practice is due to a huge number of wound dressings available, the large number of caregivers involved, and the many opinions regarding optimum wound care. As to acute wounds, few guidelines have yet been published. The evidence-based guidelines on acute wound care presented here may help achieve a more uniform policy to treat acute wounds in all settings and an improved effectiveness and quality of wound care.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES.

• A multidisciplinary team developed guidelines to provide practical recommendations for acute wound care in order to render more uniformity, effectiveness, and quality in the care for acute wounds after surgery or trauma.

• The guidelines address five controversial issues: wound cleansing, pain relief, dressing choice, patient instructions, and organizational aspects (Fig. 1).

• The guidelines present 38 recommendations and 2 flowcharts, based on best available evidence, additional expert considerations, and patient experiences.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AGREE

appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation

- AWMA

Australian Wound Management Association

- CDC

centers for disease control and prevention

- CPI

clinical practice improvement

- EMLA

eutectic mixture of local anesthetics

- EWMA

European Wound Management Association

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- SQuIre

safety and quality investment for reform

- TIME

tissue, infection, moisture, edge

- VAS

visual analog scale

- WG

working group

- WHO

World Health Organization

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

The authors are indebted to the 18 independent members of 12 professional societies who critically reviewed the concept guidelines, as well as the members of the guideline development working group: Dr. F.E. Brölmann, MD, PhD (project executor); Dr. D.T. Ubbink, MD, PhD (project leader); Dr. H. Vermeulen, RN, PhD (chairperson); Mrs. P.E. Broos-van Mourik, MSc, Society of Nursing and Care Professionals (V&VN); Dr. P.M.N.Y.H. Go, MD, PhD, Dutch Surgical Society (NVvH); Mrs. E.S. de Haan, RN, Dutch Society of Emergency Care Nurses (NVSHV); Mr. M.W.F. van Leen, Association of Elderly Care Physicians and Social Geriatricians (Verenso); Mr. J.W. Lokker, Association of Healthcare Insurers (ZN); Dr. C.M. Mouës-Vink, MD, PhD, Dutch Society for Plastic Surgery (NVPC); Dr. K. Munte, MD, Dutch Society for Dermatology and Venereology (NVDV); Mr. P. Quataert, MSc, Society of Nursing and Care Professionals (V&VN); Dr. K. Reiding, MD, Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG); Dr. E.R. Schinkel, MD, General Practitioner; Mrs. K.C. Timm, RN, Woundcare Consultant Society (WCS Kenniscentrum Wondzorg); Dr. M. Verhagen, MD, Dutch Society of Emergency Medicine Physicians (NVSHA); Dr. M.J.T. Visser, MD, Dutch Surgical Society (NVvH); Mr. T.A. van Barneveld, MSc, Association of Medical Specialists (OMS).

Further, we like to thank Prof. Dr. B.E. Sumpio, Professor of Surgery and Radiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Prof. Dr. Z.E. Moore, Professor and Head of the School of Nursing and Midwifery, RCSI School of Nursing, Dublin, Ireland; and Prof. Dr. K.F. Cutting, Principal Lecturer in Tissue Viability, Buckinghamshire New University, Uxbridge, United Kingdom, for their valuable comments.

The development of these guidelines was sponsored by the Dutch Society of Surgeons and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

There are no competing financial interests. The contents of this article were expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Dirk Ubbink, MD, PhD, is a research physician and clinical epidemiologist. He is a principal investigator at the Department of Surgery in the Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam. Fleur Brölmann, MD, PhD, is a surgery resident in training to become a plastic surgeon. Peter Go, MD, PhD, is a surgeon at the St. Antonius Hospital and chairman of the guidelines committee of the Dutch Society of Surgeons. Hester Vermeulen, RN, PhD, is a nurse and senior researcher at the Department of Surgery and member of the faculty of lecturers of the School for Health Professions at the University of Amsterdam.

References

- 1.Barbul A. Wound care guidelines of the wound healing society: foreword. Wound Rep Regen 2006;14:645–646 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskes AM, Storm-Versloot MN, Vermeulen H, Ubbink DT. Do stakeholders in wound care prefer evidence-based wound care products? A survey in the Netherlands. Int Wound J 2012;9:624–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franz MG, Robson MC, Steed DL, Barbul A, Brem H, Cooper DM, et al. Wound Healing Society. Guidelines to aid healing of acute wounds by decreasing impediments of healing. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:723–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Kang E, Hewitt J, Nieuwenhoven P, Morley N. Postsurgery wound assessment and management practices: a chart audit. J Clin Nurs 2014. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1111/jocn.12574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1308–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, et al. GRADE Working Group. Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:1049–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brölmann FE, Vermeulen H, Go P, Ubbink D. Guideline ‘Wound Care’: recommendations for 5 challenging areas. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2013;157:A6086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez R, Griffiths R. Water for wound cleansing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; Issue 2, Art. No.: CD003861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gravett A, Sterner S, Clinton JE, Ruiz E. A trial of povidone-iodine in the prevention of infection in sutured lacerations. Ann Emerg Med 1987;16:167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dire DJ, Welsh AP. A comparison of wound irrigation solutions used in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:704–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eidelman A, Weiss JM, Baldwin CL, Enu IK, McNicol ED, Carr DB. Topical anaesthetics for repair of dermal laceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; Issue 6. Art. No.: CD005364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alessandri F, Lijoi D, Mistrangelo E, Nicoletti A, Crosa M, Ragni N. Topical diclofenac patch for postoperative wound pain in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery: A randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2006;13:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berben SA, Kemps HH, van Grunsven PM, Mintjes-de Groot JA, van Dongen RT, Schoonhoven L. Guideline ‘Pain management for trauma patients in the chain of emergency care’. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2011;155:A3100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care 2012. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/index.html (last accessed February13, 2014)

- 15.Law NH, Ellis H. Exposure of the wound - a safe economy in the NHS. Postgrad Med J 1987;63:27–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan M, Van der Auwera P, Andry G, Aoun M, Chantrain G, Deraemaecker R, et al. Wound dressing in major head and neck cancer surgery: a prospective randomised study of gauze dressing vs sterile Vaseline ointment. Eur J Surg Oncol 1993;19:10–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merei JM, Jordan I. Pediatric clean surgery wounds: is dressing necessary? J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1871–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeulen H, Ubbink DT, Goossens A, de Vos R, Legemate DA. Systematic review of dressings and topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Br J Surg 2005;92:665–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H, Goossens A, Kelner RB, Schreuder SM, Lubbers MJ. Occlusive vs gauze dressings for local wound care in surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg 2008;143:950–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brölmann FE, Eskes AM, Goslings JC, Niessen FB, de Bree R, Vahl AC, et al. ; REMBRANDT study group. Randomized clinical trial of donor-site wound dressings after split-skin grafting. Br J Surg 2013;100:619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heal C, Buettner P, Raasch B, Browning S, Graham D, Bidgood R, et al. Can sutures get wet? Prospective randomised controlled trial of wound management in general practice. BMJ 2006;332:1053–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt MG, Moore CC, Conlin AE, Stein JD, Doyle PC. A pilot randomized control trial of scar repigmentation with UV light and dry tattooing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;139:769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Due E, Rossen K, Sorensen LT, Kliem A, Karlsmark T, Haedersdal M. Effect of UV irradiation on cutaneous cicatrices: a randomized, controlled trial with clinical, skin reflectance, histological, immunohistochemical and biochemical evaluation. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermeulen H, Ubbink DT, Schreuder SM, Lubbers MJ. Inter- and intra-observer (dis)agreement among nurses and doctors to classify colour and exudation of open surgical wounds according to the Red-Yellow-Black scheme. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:1270–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher J. Wound bed preparation and TIME principles. Nursing Standard 2005;30:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ADAPTE Collaboration. Guideline adaptation: a resource toolkit. 2009. www.g-i-n.net/document-store/working-groups-documents/adaptation/adapte-resource-toolkit-guideline-adaptation-2–0.pdf (last accessed March5, 2014)

- 27.Brölmann FE, Groenewold MD, Spijker R, van der Hage JA, Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H. Does evidence permeate all surgical areas equally? Publication trends in wound care compared to breast cancer care: a longitudinal trend analysis. World J Surg 2012;36:2021–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brölmann FE, Ubbink DT, Nelson EA, Munte K, van der Horst CM, Vermeulen H. Evidence-based decisions for local and systemic wound care. Br J Surg 2012;99:1172–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer-Somers K. The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies—a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:888–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]