Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The expected duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS) is important to women making decisions about possible treatments.

OBJECTIVES

To determine total duration of frequent VMS (≥6 days in the previous 2 weeks) (hereafter total VMS duration) during the menopausal transition, to quantify how long frequent VMS persist after the final menstrual period (FMP) (hereafter post-FMP persistence), and to identify risk factors for longer total VMS duration and longer post-FMP persistence.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is a multiracial/multiethnic observational study of the menopausal transition among 3302 women enrolled at 7 US sites. From February 1996 through April 2013, women completed a median of 13 visits. Analyses included 1449 women with frequent VMS.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Total VMS duration (in years) (hot flashes or night sweats) and post-FMP persistence (in years) into postmenopause.

RESULTS

The median total VMS duration was 7.4 years. Among 881 women who experienced an observable FMP, the median post-FMP persistence was 4.5 years. Women who were premenopausal or early perimenopausal when they first reported frequent VMS had the longest total VMS duration (median, >11.8 years) and post-FMP persistence (median, 9.4 years). Women who were postmenopausal at the onset of VMS had the shortest total VMS duration (median, 3.4 years). Compared with women of other racial/ethnic groups, African American women reported the longest total VMS duration (median, 10.1 years). Additional factors related to longer duration of VMS (total VMS duration or post-FMP persistence) were younger age, lower educational level, greater perceived stress and symptom sensitivity, and higher depressive symptoms and anxiety at first report of VMS.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Frequent VMS lasted more than 7 years during the menopausal transition for more than half of the women and persisted for 4.5 years after the FMP. Individual characteristics (eg, being premenopausal and having greater negative affective factors when first experiencing VMS) were related to longer-lasting VMS. Health care professionals should counsel women to expect that frequent VMS could last more than 7 years, and they may last longer for African American women.

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), including hot flashes and night sweats, are hallmarks of the menopausal transition (MT) and can significantly affect quality of life.1–3 Up to 80% of women experience VMS during the MT,4,5 and most rate them as moderate to severe.6 Vasomotor symptoms are one of the chief menopause-related problems for which US women seek medical treatment.7,8 Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) suggest that VMS are also independently associated with multiple indicators of elevated cardiovascular risk9,10 and greater bone loss and higher bone turnover.11

Despite their pervasiveness, negative influence on quality of life, and association with adverse health indicators, we lack robust estimates of how long VMS last. According to a recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists report,12 previous clinical guidelines suggested that most women experience hot flashes from 6 months to 2 years, but epidemiological studies6,13,14 cast doubt on these figures, finding durations between 5 and 13 years. Although mounting evidence suggests that VMS last much longer than originally presumed, current estimates of VMS duration are limited in part because of cross-sectional data or insufficient follow-up of women after the final menstrual period (FMP).

As a longitudinal study spanning 17 years, SWAN is positioned to provide more accurate estimates of VMS duration. SWAN has assessed a large cohort of women over 14 study visits as they transitioned from premenopause or early perimenopause into late postmenopause.

These analyses sought (1) to determine total duration of frequent VMS (defined as ≥6 days in the previous 2 weeks) (hereafter total VMS duration) during the MT (defined as the entire follow-up period from premenopause or early perimenopause and as far into postmenopause as each woman was observed); (2) to quantify how long frequent VMS persist after the FMP (hereafter post-FMP persistence) (ie, starting from the last menstrual period date and extending as far into postmenopause as each woman was observed); and (3) to identify risk factors for longer total VMS duration and longer post-FMP persistence. We focused on frequent VMS because women report these as most bothersome.15

Methods

Sample and Procedures

SWAN is a multiracial/multiethnic observational study characterizing biological and psychosocial changes occurring during the MT.16 Briefly, from 1995 to 1997, each clinical site recruited women of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity and women belonging to predetermined racial/ethnic minorities. The latter included African American women in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Boston, Massachusetts, Chicago, Illinois, and Ypsilanti, Michigan; Japanese women in Los Angeles, California; Hispanic women in Newark, New Jersey; and Chinese women in Oakland, California. Protocols were approved by institutional review boards at each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Baseline eligibility included age between 42 and 52 years, presence of an intact uterus and at least 1 ovary, report of a menstrual cycle in the 3 months before screening, and absence of pregnancy, lactation, or use of oral contraceptives or hormone therapy (HT). Among cohort-eligible women, 50.7% entered the longitudinal study.16 Participants were assessed in person at baseline and approximately annually through follow-up visit 13 from February 1996 through April 2013 (mean and maximum follow-up durations were 12.7 and 17.2 years, respectively). A standardized protocol of detailed questions was used about their lifestyle and psychosocial factors, physical and psychological symptoms, anthropometric measurements, and medical, reproductive, and menstrual history. All instruments were translated into Spanish, Japanese, and Cantonese.

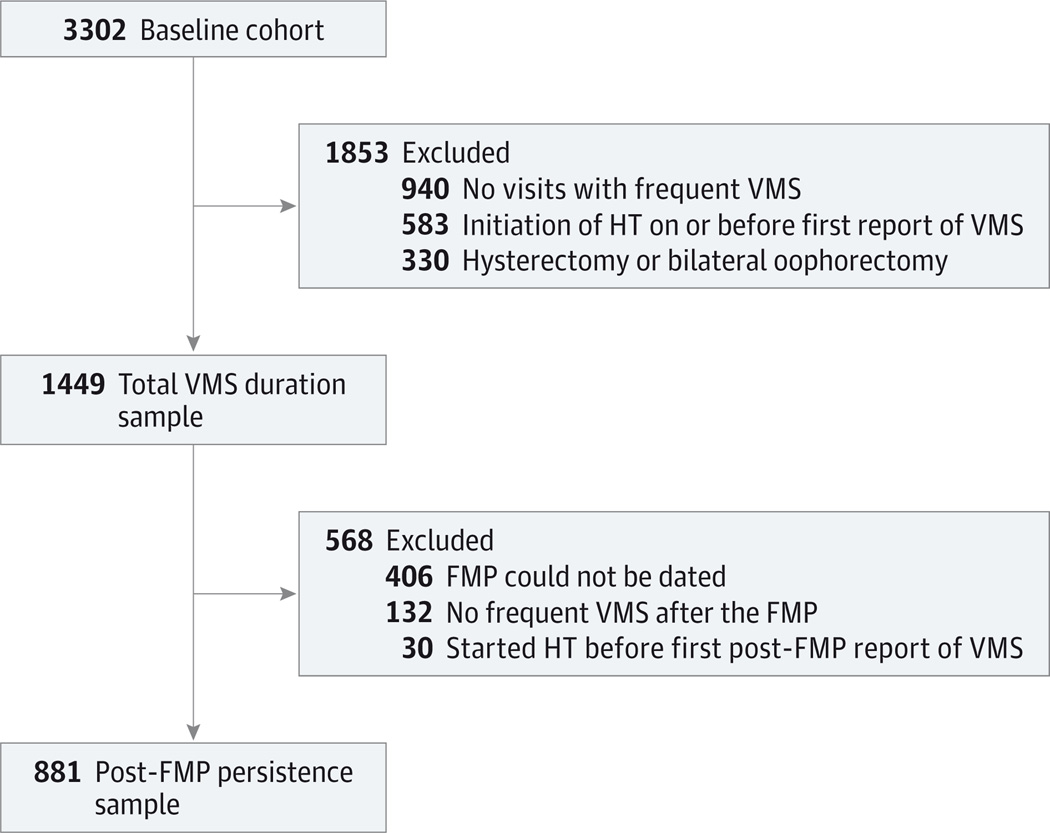

Analyses of total VMS duration included women reporting frequent VMS (≥6 days in the previous 2 weeks) at 1 or more visits. The analytic sample of 1449 women was based on the following exclusions from 3302 cohort participants at baseline enrolled at 7 US sites: hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy during SWAN (n = 330), initiation of HT on or before first report of frequent VMS (n = 583), and no visits with frequent VMS (n = 940) (Figure 1). Analyses of post-FMP persistence of frequent VMS were conducted in women with a known FMP date who reported frequent VMS at 1 or more visits occurring after the FMP. The FMP was defined retrospectively as the date of last menses preceding 12 months of amenorrhea. Among 1449 women included in analyses of total VMS duration, the FMP could not be dated in 406 women, 132 women reported no frequent VMS after the FMP, and 30 women started HT before their first post-FMP report of frequent VMS for a sample size of 881 women for post-FMP persistence.

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Study Flow Diagram.

FMP indicates final menstrual period; HT, hormone therapy; and VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hot flashes and night sweats in the past 2 weeks were assessed separately via questionnaire at each visit and recorded as occurring not at all, 1 to 5 days, 6 to 8 days, 9 to 13 days, or every day. Frequent VMS were defined as hot flashes or night sweats occurring at least 6 days in the previous 2 weeks. Earlier SWAN data have shown that experiencing VMS for at least 6 days is highly related to anxiety,17 depression,18 sleep disturbances,19 quality of life,20 cardiovascular risk,10,21–23 bone health,11,24 and VMS bothersomeness.15

Primary outcomes were (1) total VMS duration (starting at any point during the observation period) and (2) post-FMP persistence of frequent VMS (frequent VMS at any point after the FMP). Total VMS duration was calculated as years elapsed between the first and last report of frequent VMS. Post-FMP persistence was calculated as years elapsed between the first and last report of frequent VMS occurring after the FMP. For women reporting frequent VMS at a single visit, total VMS duration was assigned as 0.5 year, similar to work by Freeman et al14 (Mary Sammel, written communication, February 8, 2012). For consistency, we added0.5 year to total duration and to post-FMP persistence for all participants. Cessation of VMS was defined as the occurrence of 2 consecutive visits without HT use and without report of frequent VMS, as in the study by Freeman et al.

Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle behaviors, anthropometrics, and psychosocial variables related to prevalent or incident VMS.5 Variables assessed only at baseline (eg, race/ethnicity) or collected repeatedly but stable over time (eg, smoking) were obtained from the baseline visit, while other time-varying variables were obtained from the first visit at which frequent VMS were reported (Table 1). Sociodemographic characteristics were age, self-reported race/ethnicity, site (among 7 US sites), married or partnered status, financial strain (ie, difficulty paying for basics), and educational level.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Participants in Analyses of Total VMS Duration and Post-FMP Persistencea

| Characteristic | Total VMS Duration (n = 1449) |

Post-FMP Persistence (n = 881) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yb | 50.2 (3.9) | 51.1 (3.7) |

| Menopausal transition stage, No. (%)b | (n = 1440) | (n = 879) |

| Premenopause | 183 (12.7) | 72 (8.2) |

| Early perimenopause | 700 (48.6) | 348 (39.6) |

| Late perimenopause | 266 (18.5) | 191 (21.7) |

| Postmenopause | 291 (20.2) | 268 (30.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| African American | 479 (33.1) | 310 (35.2) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 652 (45.0) | 380 (43.1) |

| Chinese | 95 (6.6) | 65 (7.4) |

| Hispanic | 109 (7.5) | 50 (5.7) |

| Japanese | 114 (7.9) | 76 (8.6) |

| Married or partnered status, No./Total (%)b | 971/1403 (69.2) | 591/850 (69.5) |

| Financial strain, No. (%)c | (n = 1436) | (n = 873) |

| Very hard to pay for basics | 152 (10.6) | 90 (10.3) |

| Somewhat hard | 441 (30.7) | 266 (30.5) |

| Not at all hard | 843 (58.7) | 517 (59.2) |

| Education level, No. (%)c | (n = 1437) | (n = 875) |

| <College | 878 (61.1) | 527 (60.2) |

| ≥College | 559 (38.9) | 348 (39.8) |

| Smoking, No. (%)c | (n = 1440) | (n = 876) |

| Never | 770 (53.5) | 485 (55.4) |

| Past | 389 (27.0) | 232 (26.5) |

| Current | 281 (19.5) | 159 (18.2) |

| BMI, No. (%)b | (n = 1329) | (n = 809) |

| <25.0 | 452 (34.0) | 291 (36.0) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 358 (26.9) | 229 (28.3) |

| ≥30.0 | 519 (39.1) | 289 (35.7) |

| Alcohol servings per wk, No. (%)b | (n = 1347) | (n = 820) |

| None | 668 (49.6) | 417 (50.9) |

| <1 | 263 (19.5) | 165 (20.1) |

| 1–7 | 288 (21.4) | 167 (20.4) |

| >7 | 128 (9.5) | 71 (8.7) |

| Sports physical activity, mean (SD)c | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Attitudes toward menopause, mean (SD) | 16.9 (2.8) | 17.1 (2.7) |

| Symptom sensitivity at first annual follow-up, mean (SD) | 10.4 (3.5) | 10.3 (3.4) |

| Anxiety score ≥4, No. (%)b | 488/1403 (34.8) | 260/857 (30.3) |

| Perceived stress, mean (SD)b | 8.3 (3.0) | 8.1 (2.9) |

| Depressive symptoms on the CES-D Scale ≥16, No. (%)b | 386/1383 (27.9) | 193/834 (23.1) |

| Social support, mean (SD)b | 12.5 (3.3) | 12.7 (3.2) |

| Age at FMP, mean (SD), y | – | 51.6 (2.7) |

| Age, mean (SD), yd | – | 53.1 (3.2) |

| VMS cessation observed, No. (%) | 505 (34.9) | 414 (47.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression; FMP, final menstrual period; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Totals may not sum to the heading totals because of missing data on some variables.

At first VMS report.

At baseline.

At first post-FMP report of frequent VMS.

Lifestyle and anthropometric variables were assessed, including smoking and body mass index (BMI). Also evaluated were sports physical activity25,26 and alcohol servings per week.27

Psychosocial variables were recorded. These included attitudes toward menopause,28 symptom sensitivity (summed score of 5 items assessing heightened attention to bodily sensations),29 anxiety (summed score of the number of days in the past 2 weeks in which 4 symptoms[irritability or grouchiness, tenseness or nervousness, pounding or racing heart, and fearfulness for no reason] were experienced),17 perceived stress (summed score of 4 items, with the total score ranging from5 [never] to 25 [fairly often]),30 depressive symptoms (score of ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale),31 and emotional and instrumental social support (4-item summed scale).32

The MT stage at the first visit at which frequent VMS were reported was obtained from self-reported bleeding patterns during the preceding year. This variable was categorized as premenopausal (bleeding in the previous 3 months, with no change in menstrual regularity in the past year), early perimenopausal (bleeding in the previous 3 months and changes in menstrual regularity in the past year), late perimenopausal (amenorrhea in the previous 3 months but bleeding in the past year), or postmenopausal (>12 months of amenorrhea).5 Women with menstrual bleeding since the prior visit were asked for the date of the most recent menses. Analyses of post-FMP persistence of VMS included age at the FMP, which was calculated based on the last bleeding date.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the 2 analytic samples (total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence) were summarized using frequencies, means, and SDs. The unadjusted associations of covariates with total VMS duration or post-FMP persistence were assessed using Kaplan-Meier analyses and log-rank P values.33,34 For women not meeting the criterion for VMS cessation, total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence were censored at HT initiation or after the end of a participant’s data collection. Total VMS duration also was censored for women reporting frequent VMS at study baseline because we could infer only that their duration was at least as long as our duration observed herein.

The adjusted associations of total VMS duration or post-FMP persistence with covariates and corresponding adjusted median durations were estimated from Cox proportional hazards regression models. Backward elimination was used to omit redundant or unrelated predictors (P > .05), forcing in race/ethnicity and site as design variables. Proportionality of hazards was assessed by testing the significance of each predictor’s interaction with total VMS duration,35 by consideration of model fit as indicated by the Akaike information criterion statistic,36 and by plots of residuals and transformed hazard estimates.37 No nonproportional hazards were identified. Continuous covariates were categorized to allow for possible nonlinear associations. Because data collection at the Newark site was suspended during annual follow-ups 6 through 8, 10, and 11, we ran sensitivity analyses that excluded participants from this site, and results were similar. We also ran secondary analyses of total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence of any VMS in the past 2 weeks. Because patterns of association of covariates with total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence were similar for any VMS and for frequent VMS, we report only results for frequent VMS for brevity and clinical relevance. Results are presented as hazard ratios (95% CIs) and as the median total VMS duration or post-FMP persistence. For subgroups whose median could not be estimated because too few women had ceased having frequent VMS, results a represented as greater than the longest observed (noncensored) total VMS duration.

Results

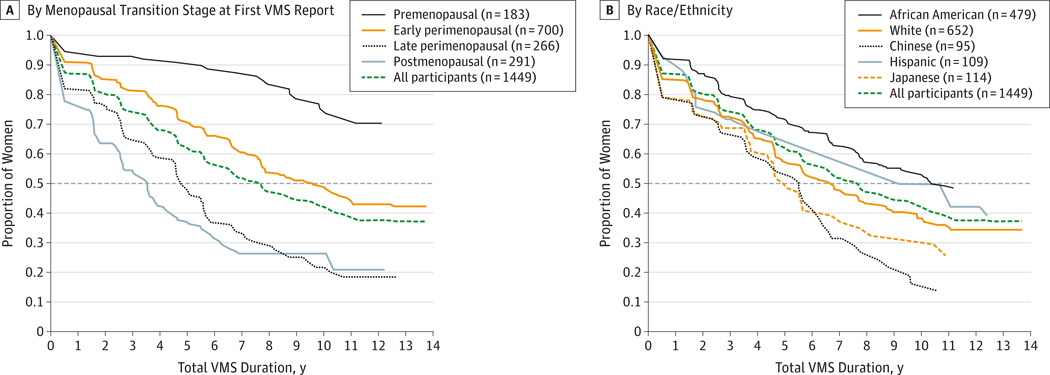

Characteristics of each sample are summarized in Table 1. The unadjusted median total VMS duration was 7.4 years (Figure 2A). Women who were premenopausal or early perimenopausal when they first reported frequent VMS had the longest total VMS duration (median, >11.8 years) and post-FMP persistence (median, 9.4 years). Women who were postmenopausal at the onset of VMS had the shortest total VMS duration after the FMP (median, 3.4 years; P < .001). The median total VMS duration varied significantly by race/ethnicity (P < .001) (Figure 2B). African American women reported the longest total VMS duration (median, 10.1 years), and Japanese and Chinese women had the shortest total VMS durations (median, 4.8 and 5.4 years, respectively). The median total VMS durations were 6.5 years for non-Hispanic white women and 8.9 years for Hispanic women. Except for Chinese vs Japanese women, all pairwise racial/ethnic differences were statistically significant (P < .05). Total VMS duration was also significantly longer in those with younger age at first report of VMS, in ever smokers, and in women with greater BMI and higher symptom sensitivity, anxiety, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. Total VMS duration was significantly shorter in women who were currently married or partnered, in women who had higher educational level and less financial strain, and in women who had greater social support. Neither sports physical activity nor alcohol servings per week were statistically significant.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Total VMS Duration of Frequent VMS by Menopausal Transition Stage at First VMS Report (A) and by Race/Ethnicity (B).

A, By menopausal transition stage at first VMS report. B, By race/ethnicity. VMS indicates vasomotor symptoms. Menopausal transition stage at first VMS report is missing for 9 participants. Median duration for each group is calculated as the value on the x-axis corresponding to the intersection of the dashed horizontal line (50%) with the group’s survival curve.

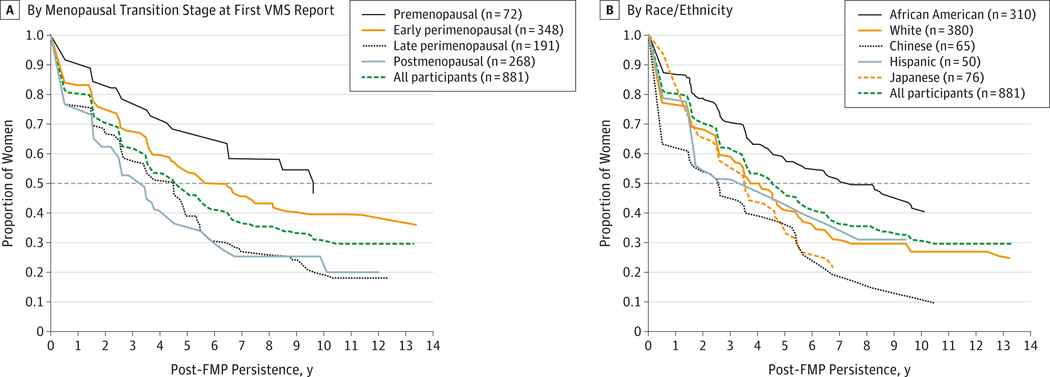

The unadjusted median post-FMP persistence was 4.5 years. Associations with participant characteristics were similar to those for total VMS duration except for married or partnered status, attitudes toward menopause, and age at the FMP, although statistical significance was sometimes lower because of smaller samples. Consistent with total VMS duration findings, post-FMP persistence was shorter for women with later MT stage at first report of frequent VMS (Figure 3A) and for Chinese and Japanese women (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Post-FMP Persistence of Frequent VMS by Menopausal Transition Stage at First VMS Report and by Race/Ethnicity.

A, By menopausal transition stage at first VMS report. B, By race/ethnicity. FMP indicates final menstrual period; VMS, vasomotor symptoms. Menopausal transition stage at first VMS report is missing for 2 participants. Median duration for each group is calculated as the value on the x-axis corresponding to the intersection of the dashed horizontal line (50%) with the group’s survival curve.

Factors related to total VMS duration or post-FMP persistence in the adjusted models are summarized in Table 2. A hazard ratio exceeding 1.0 indicated a greater likelihood of VMS cessation (reflecting a shorter total VMS duration associated with that factor vs without it), a hazard ratio of less than 1.0 indicated a lesser likelihood of VMS cessation (reflecting longer total VMS duration associated with that factor vs without it), and a hazard ratio of 1.0 indicated no difference in VMS duration for those with that factor vs without it. Factors that remained statistically significant in multivariable analyses were earlier MT stage, perceived stress, higher symptom sensitivity, lower educational level, depressed symptoms at first report of VMS, longer total VMS duration observed with younger age, and African American race/ethnicity (with shorter total VMS duration for Chinese women). Similarly, associations between longer post-FMP persistence and younger age, earlier MT stage, lower educational level, higher symptom sensitivity, more anxiety, and greater perceived stress also remained statistically significant in the multivariable model, as did shorter total VMS duration for Chinese women. In sensitivity analyses omitting women with frequent VMS at study entry (who were disproportionately younger and at an earlier MT stage at the onset of VMS than other women), the resulting distribution of total VMS duration was lower, with an overall median duration of 5.5 years. However, patterns of association of participant characteristics were consistent with those in the full sample.

Table 2.

Reduced Models of the Adjusted HRs and Medians for Total VMS Duration and Post-FMP Persistencea

| Total VMS Duration (n = 1368) |

Post-FM P Persistence (n = 772) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR (95% CI)b | Median Duration, y |

P Value | HR (95% CI)b | Median Persistence, y |

P Value |

| Age, yc | ||||||

| 42.0–44.9 | 1 [Reference] | >10.90 | <.005 | NAd | NA | .05 |

| 45.0–49.9 | 2.43 (1.30–4.51) | 9.34 | 1 [Reference]e | 6.76 | ||

| 50.0–54.9 | 2.71 (1.44–5.09) | 7.73 | 1.16 (0.84–1.60) | 5.72 | ||

| ≥55.0 | 3.60 (1.78–7.29) | 6.42 | 1.53 (1.05–2.24) | 4.48 | ||

| Menopausal transition stage | ||||||

| Premenopause | 1 [Reference] | >10.90 | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | >10.43 | .001 |

| Early perimenopause | 2.04 (1.35–3.11) | 10.06 | 1.48 (0.89–2.27) | 6.61 | ||

| Late perimenopause | 3.55 (2.26–5.60) | 6.12 | 2.16 (1.33–3.49) | 4.47 | ||

| Postmenopause | 3.74 (2.34–5.98) | 5.66 | 2.04 (1.27–3.28) | 4.59 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 [Reference] | 9.01 | <.008 | 1 [Reference] | 5.43 | .048 |

| African American | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | >10.90 | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | 6.88 | ||

| Chinese | 1.80 (1.17–2.76) | 5.45 | 1.84 (1.14–2.95) | 3.05 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.97 (0.56–6.92) | 4.78 | 1.06 (0.19–5.84) | 4.92 | ||

| Japanese | 1.00 (0.66–1.51) | 9.34 | 0.91 (0.57–1.45) | 5.77 | ||

| Educational level ≥college | ||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 9.93 | .03 | 1 [Reference] | 6.54 | .003 |

| Yes | 1.25 (1.03–1.52) | 7.66 | 1.40 (1.13–1.74) | 4.54 | ||

| Symptom sensitivity at first annual follow-upf | ||||||

| Very low | 1 [Reference] | 7.36 | .05 | 1 [Reference] | 4.38 | .049 |

| Low | 0.77 (0.58–1.00) | 9.57 | 0.76 (0.56–1.04) | 5.48 | ||

| Moderate | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 8.22 | 0.78 (0.57–1.07) | 5.45 | ||

| High | 0.64 (0.46–0.89) | 10.81 | 0.58 (0.39–0.85) | 8.47 | ||

| Anxiety score ≥4c | ||||||

| No | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 4.96 | .02 |

| Yes | NA | NA | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) | 7.40 | ||

| Perceived stressc,g | ||||||

| Never or almost never | 1 [Reference] | 8.00 | .02 | 1 [Reference] | 4.92 | .008 |

| At least sometimes | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | 10.78 | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) | 8.13 | ||

| Depressive symptoms on the CES-D Scale ≥16c | ||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 7.73 | .005 | NA | NA | NA |

| Yes | 0.66 (0.50–0.88) | >10.90 | NA | NA | ||

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression; FMP, final menstrual period; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Adjusted for all variables listed and for site. The total sample sizes are smaller than those in Table 1 because of missing data for some covariates.

Compared with the reference group, an HR exceeding 1.0 indicates shorter duration, an HR of less than 1.0 indicates longer duration, and an HR of 1.0 indicates no difference in duration.

At first VMS report for VMS duration and at first post-FMP report of frequent VMS for post-FMP persistence.

This variable was omitted in the backward elimination analysis.

Because the number of women in the age category of 42.0 to 44.9 years was very small for post-FMP persistence, the 2 lowest age categories were combined so that the reference category was up to age 49.9 years.

Very low is below the mean −1 SD (<6.9), low is between the mean and −1 SD (7.0–10.4), moderate is between the mean and 1 SD (10.5–13.8), and high is above the mean +1 SD (>13.8).

A score between 5 and 10 is never or almost never, and a score between 11 and 25 is at least sometimes.

Discussion

Vasomotor symptoms represent a frequent troublesome midlife experience among most women, but data on duration of these menopausal symptoms have been lacking. SWAN provides the strongest estimates to date of total VMS duration over the MT and post-FMP persistence in a multiracial/multiethnic sample of women. Among women who reported frequent VMS, the median total VMS duration was 7.4 years, with VMS persisting a median of 4.5 years after the FMP. African American women had particularly persistent VMS, with a median total VMS duration of 10.1 years. Compared with other similar investigations, SWAN has the benefits of a larger and multiracial/multiethnic sample followed up for a longer period after the FMP and inclusion of women reporting VMS at the first SWAN visit, minimizing (but not totally eliminating) truncation of actual total VMS duration.

Other cohort studies have reported shorter13 and longer6,14 total VMS durations. The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project estimate of 5.2 years for total duration of bothersome VMS may have been conservative because the investigation largely comprised a sample of white race/ethnicity, with exclusion of women reporting VMS at baseline and counting women still having VMS at the last follow-up visit as no longer having VMS.13 In contrast, longer total VMS durations of 8.8 years6 and 10.2 years14 were reported by the Penn Ovarian Aging Study, which asked about VMS in the past year and recruited a considerably younger sample at entry. The only study6 that examined total VMS duration after the FMP found a mean duration of 4.6 years for moderate to severe hot flashes, similar to our observation.

The best single predictor of both total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence was beginning VMS at an earlier MT stage. Women who experienced frequent VMS early in the MT had a significantly longer total VMS duration and, perhaps counter intuitively, had longer post-FMP persistence after their FMP. This finding is consistent with other studies6,14 but provides stronger evidence given a longer duration of follow-up after the FMP in the present study.

We observed pronounced racial/ethnic differences. African American women had longer total VMS duration, and Chinese and Japanese women had shorter total VMS duration. Only one other study14 examined racial/ethnic influences on VMS duration. In that smaller study of women of African American and non-Hispanic white races/ethnicities, a similarly longer total VMS duration among African Americans was reported. Shorter total VMS duration among Chinese and Japanese women is consistent with research showing a lower proportion of Asian women reporting hot flashes.5,38,39 The physiological underpinnings of ethnic/racial differences in total VMS duration are unknown to date. Women with greater BMI had longer total VMS duration, broadly consistent with other findings from SWAN indicating a greater likelihood of reporting hot flashes with higher adiposity.5,15 However, BMI was no longer significantly associated with total VMS duration herein in multivariable models when considering factors such as race/ethnicity.

The observed higher degrees of perceived stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and symptom sensitivity that were independently related to longer total VMS duration or longer post-FMP persistence herein extend previous findings that these psychological factors are related to VMS prevalence.4,5,40–43 Pathways connecting negative affective factors and VMS are likely complex and bidirectional.15,44–46 A direct physiological link through the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis between negative affective factors and VMS has been proposed47 but is not well tested.

The present study had several limitations. We may have underestimated total VMS duration because VMS were measured annually and the time frame of inquiry was for the 2 weeks preceding the visit. Although prior work has indicated that sensitivity and specificity for 2-week self-reported VMS are high,48 we may have missed the onset of VMS or occurrence because VMS fluctuate over time.49 Consistent with other work,14 we required at least 2 consecutive HT-free and frequent VMS–free study visits to define cessation of frequent VMS, but VMS may have reoccurred after the end of data collection. Finally, despite up to 13 years of follow-up, some women continued to report frequent VMS, so longer follow-up is needed to better pinpoint the timing of cessation of VMS.

Although duration and persistence of any VMS are important to women and their health care professionals, these analyses focus on total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence of frequent VMS rather than any VMS for 2 main reasons. First, frequent VMS are more bothersome and more likely to influence women’s clinical decisions (such as initiating treatment). Second, despite our lengthy follow-up, well over half of the women who had any VMS continued to experience them at follow-up visit 13, precluding estimation of the median cessation. However, secondary analyses showed that patterns of association between participant characteristics and duration for any VMS were similar to those for frequent VMS.

A major strength of our study is that SWAN is the largest and longest longitudinal study to date reporting on total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence. The longitudinal nature and long-term follow-up are critical to obtain accurate total VMS duration estimates. In contrast to prior studies,6,13,14 we included women with frequent VMS at baseline, who were all premenopausal or early perimenopausal at the onset of frequent VMS and tended to have longer total VMS durations. The long follow-up also permitted analyses of both total VMS duration and post-FMP persistence. SWAN is unique in its capacity to study 5 racial/ethnic groups, underscored by longer total VMS durations observed in African American women. Finally, we examined multiple predictors of total VMS duration and controlled for various potential confounding variables that were collected annually.

Conclusions

More than 50% of midlife women experience frequent VMS, yet clinical guidelines typically underestimate their true duration. Among women with frequent VMS, symptoms last for approximately 7.4 years, they persist for approximately 4.5 years after the FMP, and they last the longest in African American women. Specific characteristics related to longer-lasting VMS included mutable factors such as anxiety, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. These findings can help health care professionals counsel patients about expectations regarding VMS and assist women in making treatment decisions based on the probability of their VMS persisting. In addition, the median total VMS duration of 7.4 years highlights the limitations of guidance recommending short-term HT use and emphasizes the need to identify safe long-term the rapies for the treatment of VMS.

Acknowledgments

Dr Joffe reported receiving grant support from Cephalon/Teva and serving as a consultant to Noven and on an advisory board for Merck.

Funding/Support: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support (grants U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, and U01AG012495) from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, and Office of Research on Women’s Health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We thank the study staff at each site and the women who participated in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation.

Group Information

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) includes the following components. Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Siobán Harlow, principal investigator 2011 to present, and MaryFran Sowers, principal investigator 1994 to 2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston: Joel Finkelstein, principal investigator 1999 to present, and Robert Neer, principal investigator 1994 to 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois: Howard M. Kravitz, principal investigator 2009 to present, and Lynda Powell, principal investigator 1994 to 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser: Ellen B. Gold, principal investigator; University of California, Los Angeles: Gail Greendale, principal investigator; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York: Carol Derby, principal investigator 2011 to present, Rachel Wildman, principal investigator 2010 to 2011, and Nanette Santoro, principal investigator 2004 to 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry–New Jersey Medical School, Newark: Gerson Weiss, principal investigator 1994 to 2004; and University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Karen Matthews, principal investigator. National Institutes of Health Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, Maryland: Winifred Rossi, 2012 to present, Sherry Sherman, 1994 to 2012, and Marcia Ory, 1994 to 2001; and National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, Maryland: program officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Maria Mori Brooks, principal investigator 2012 to present, and Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, principal investigator 2001 to 2012; and New England Research Institutes, Watertown, Massachusetts: Sonja McKinlay, principal investigator 1995 to 2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, current chair, and Chris Gallagher, former chair.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Avis and Crawford had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Avis, Crawford, Greendale, Bromberger, Gold, Hess, Joffe, Thurston.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Avis, Crawford, Greendale.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Avis, Crawford.

Obtained funding: Avis, Crawford, Greendale, Bromberger, Gold, Kravitz.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No other disclosures were reported.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, Office of Research on Women’s Health, or National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Nancy E. Avis, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Sybil L. Crawford, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester.

Gail Greendale, Division of Geriatric Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles.

Joyce T. Bromberger, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Susan A. Everson-Rose, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis.

Ellen B. Gold, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health Sciences, UC Davis School of Medicine, University of California, Davis.

Rachel Hess, Department of Medicine, University of Utah Schools of the Health Sciences, Salt Lake City.

Hadine Joffe, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts.

Howard M. Kravitz, Departments of Psychiatry and Preventive Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Ping G. Tepper, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Rebecca C. Thurston, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avis NE, Ory M, Matthews KA, Schocken M, Bromberger J, Colvin A. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Med Care. 2003;41(11):1262–1276. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093479.39115.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blümel JE, Chedraui P, Baron G, et al. Collaborative Group for Research of the Climacteric in Latin America (REDLINC) A large multinational study of vasomotor symptom prevalence, duration, and impact on quality of life in middle-aged women. Menopause. 2011;18(7):778–785. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318207851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, Lewis J, Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Symptoms during the perimenopause: prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in women’s lives. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause. 2014;21(9):924–932. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Fehnel SE, Clark RV. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas. 2007;58(4):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson WK, Ellison SA, Grason H, Powe NR. Patterns of ambulatory care use for gynecologic conditions: a national study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(4):523–530. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and subclinical cardiovascular disease: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;118(12):1234–1240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Powell LH, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and carotid intima media thickness among midlife women. Menopause. 2011;18(4):352–358. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181fa27fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crandall CJ, Tseng CH, Crawford SL, et al. Association of menopausal vasomotor symptoms with increased bone turnover during the menopausal transition. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(4):840–849. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Col NF, Guthrie JR, Politi M, Dennerstein L. Duration of vasomotor symptoms in middle-aged women: a longitudinal study. Menopause. 2009;16(3):453–457. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818d414e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Liu Z, Gracia CR. Duration of menopausal hot flushes and associated risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(5):1095–1104. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318214f0de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, et al. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008;15(5):841–847. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. Design, survey sampling and recruitment methods of SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsay J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y, et al. Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2013;20(5):488–495. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182730599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, et al. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Affect Disord. 2007;103(1–3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kravitz HM, Zhao X, Bromberger JT, et al. Sleep disturbance during the menopausal transition in a multi-ethnic community sample of women. Sleep. 2008;31(7):979–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avis NE, Colvin A, Bromberger JT, et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(5):860–869. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a3cdaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Are vasomotor symptoms associated with alterations in hemostatic and inflammatory markers? findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1044–1051. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f5d39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Vasomotor symptoms and insulin resistance in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):3487–3494. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Vasomotor symptoms and lipid profiles in women transitioning through menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):753–761. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824a09ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crandall CJ, Zheng Y, Crawford SL, et al. Presence of vasomotor symptoms is associated with lower bone mineral density: a longitudinal analysis. Menopause. 2009;16(2):239–246. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181857964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry CP. Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev Med. 1999;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(5):936–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Thoerig RC, Friday JE, Shimizu M, Moshfegh AJ. Food Patterns Equivalents Database 2009–2010: methodology and user guide. [Accessed December 26, 2014]; http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg.

- 28.Sommer B, Avis N, Meyer P, et al. Attitudes toward menopause and aging across ethnic/racial groups. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(6):868–875. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199911000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barsky AJ, Goodson JD, Lane RS, Cleary PD. The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1988;50(5):510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1997;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.So Y, Johnston G, Kim SH. Proceedings of the SAS Global Forum 2010 Conference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2010. Analyzing interval-censored survival data with SAS software. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Sun J. Interval censoring. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19(1):53–70. doi: 10.1177/0962280209105023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agresti A, Caffo B. Measures of relative model fit. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2002;39(2):127–136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess KR. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;14(15):1707–1723. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avis NE, Kaufert PA, Lock M, McKinlay SM, Vass K. The evolution of menopausal symptoms. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;7(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulet MJ, Oddens BJ, Lehert P, Vemer HM, Visser A. Climacteric and menopause in seven south-east Asian countries. Maturitas. 1994;19(3):157–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nedstrand E, Wijma K, Lindgren M, Hammar M. The relationship between stress-coping and vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1998;31(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds F. Relationships between catastrophic thoughts, perceived control and distress during menopausal hot flushes: exploring the correlates of a questionnaire measure. Maturitas. 2000;36(2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lermer MA, Morra A, Moineddin R, Manson J, Blake J, Tierney MC. Somatic and affective anxiety symptoms and menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2011;18(2):129–132. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ec58f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Kapoor S, Ferdousi T. The role of anxiety and hormonal changes in menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2005;12(3):258–266. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000142440.49698.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson CJ, Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Kamarck T, Matthews KA. Negative affect and vasomotor symptoms in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Daily Hormone Study. Menopause. 2011;18(12):1270–1277. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182230e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunter MS, Chilcot J. Testing a cognitive model of menopausal hot flushes and night sweats. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thurston RC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A. Emotional antecedents of hot flashes during daily life. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):137–146. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149255.04806.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanisch LJ, Hantsoo L, Freeman EW, Sullivan GM, Coyne JC. Hot flashes and panic attacks: a comparison of symptomatology, neurobiology, treatment, and a role for cognition. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(2):247–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crawford SL, Avis NE, Gold E, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of recalled vasomotor symptoms in a multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(12):1452–1459. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crawford S, Avis NE, Kelsey J, Gold E, Santoro N. Is annual measurement of hot flashes sufficiently frequent in perimenopause? [abstract] Menopause. 2004;11(6):682. [Google Scholar]