SUMMARY

The genomic regulatory programs that underlie human organogenesis are poorly understood. Pancreas development, in particular, has pivotal implications for pancreatic regeneration, cancer, and diabetes. We have now characterized the regulatory landscape of embryonic multipotent progenitor cells that give rise to all pancreatic epithelial lineages. Using human embryonic pancreas and embryonic stem cell-derived progenitors we identify stage-specific transcripts and associated enhancers, many of which are co-occupied by transcription factors that are essential for pancreas development. We further show that TEAD1, a Hippo signaling effector, is an integral component of the transcription factor combinatorial code of pancreatic progenitor enhancers. TEAD and its coactivator YAP activate key pancreatic signaling mediators and transcription factors, and regulate the expansion of pancreatic progenitors. This work therefore uncovers a central role of TEAD and YAP as signal-responsive regulators of multipotent pancreatic progenitors, and provides a resource for the study of embryonic development of the human pancreas.

The human genome sequence contains instructions to generate a vast number of developmental programs. This is possible because each developmental cellular state uses a distinct set of regulatory regions. The specific genomic programs that underlie human organogenesis, however, are still largely unknown1,2. Knowledge of such programs could be exploited for regenerative therapies, or to decipher developmental defects underlying human disease.

The pancreas hosts some of the most debilitating and deadly diseases, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and diabetes mellitus. Classic mouse knockout models and human genetics have uncovered multiple transcription factors (TFs) that regulate embryonic formation of the pancreas3,4. For example, GATA65-7, PDX18,9, HNF1B10, ONECUT111, FOXA1/FOXA212, SOX913,14 and PTF1A15, are essential for the specification of pancreatic multipotent progenitor cells (MPCs) that arise from the embryonic gut endoderm, or for their subsequent outgrowth and branching morphogenesis. However, little is known concerning how these pancreatic TFs are deployed as regulatory networks, or which genomic sequences are required to activate pancreatic developmental programs.

One obvious limitation to study the genomic regulation of human organogenesis lies in the restricted access and the difficulties of manipulating human embryonic tissue. Theoretically, this can be circumvented by using human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) to derive cellular populations that express organ-specific progenitor markers, although it is unclear if such cells can truly recapitulate broad genomic regulatory programs of genuine progenitors.

In the current study, we dissected pancreatic buds from human embryos and used hESCs to create stage-matched pancreatic progenitor cells. We processed both cellular sources in parallel and validated in vitro MPCs as a model to study gene regulation in early pancreas development. We created an atlas of active transcripts and enhancers in human pancreatic MPCs, and mapped the genomic binding sites of key pancreatic progenitor TFs. Using this resource, we show that TEA domain (TEAD) factors are integral components of the combination of TFs that activates stage- and lineage-specific pancreatic MPC enhancers.

RESULTS

Regulatory landscape of in vivo and in vitro MPCs

To study the genomic regulatory programs of the nascent embryonic pancreas, we dissected pancreatic buds from Carnegie Stage 16-18 human embryos. At this stage, the pancreas has a simple epithelial structure formed by cells expressing markers of pancreatic MPCs (including PDX1, HNF1B, FOXA2, NKX6.1 and SOX9), without obvious signs of endocrine or acinar differentiation, and is surrounded by mesenchymal cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a)16. For simplicity, we refer to this pancreatic MPC-enriched tissue as in vivo MPCs. Because human embryonic tissue is extremely limited and less amenable to perturbation studies, in parallel we used hESCs for in vitro differentiation of cells that express the same constellation of markers as in vivo MPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1a)17. We refer to these cells as in vitro MPCs. We performed RNA-seq and ChIP-seq analysis of in vivo and in vitro MPCs to profile polyadenylated transcripts, genomic sites bound by FOXA2 (a developmental TF that is specific to epithelial cells within the pancreas), and genomic regions enriched in the enhancer mark H3K4me1 (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Tables 1,2).

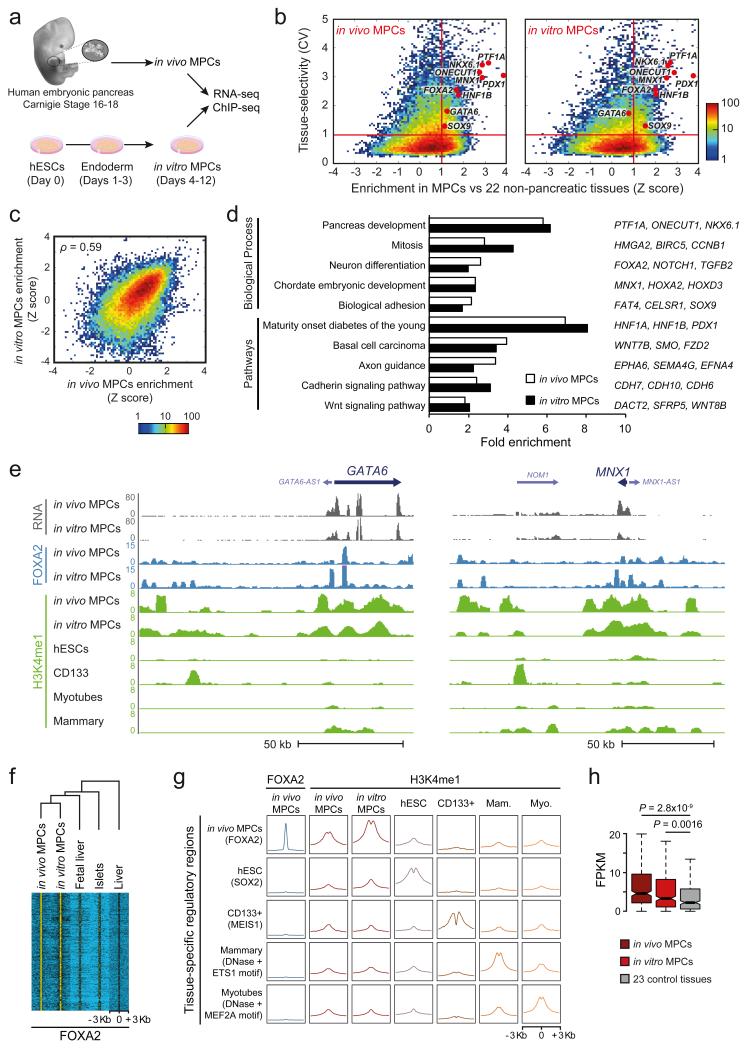

Figure 1.

Human in vitro MPCs recapitulate transcriptional and epigenomic features of in vivo MPCs. (a) Experimental set-up. Pancreas was dissected from human Carnegie stage 16-18 embryos (in vivo MPCs). In vitro MPCs were derived from hESCs. (b) In vitro and in vivo MPCs share tissue-selective genes. Tissue-selectivity of RNAs was determined by the coefficient of variation (CV) across 25 embryonic and adult tissues or cell types. Enrichment of RNAs in MPCs relative to non-pancreatic tissues was quantified as a Z-score. Red lines define genes that are both tissue-selective and enriched in MPCs (CV>1, Z>1). Most known pancreatic regulatory TFs are in this quadrant in both sources of MPCs. Color scale depicts number of transcripts. (c) Z-scores of genes expressed in at least one source of MPCs were highly correlated for in vitro vs. in vivo MPCs (see also Supplementary Figure 1d for a comparison of unrelated tissues). Spearman's coefficient value is shown. Color scale depicts number of transcripts. (d) In vivo and in vitro MPC-enriched genes have common functional annotations. Shown are most significant terms for in vivo MPC-enriched genes, and their fold enrichment in both sources of MPCs. Representative genes from each category that are enriched in both MPCs are shown on the right. More extensive annotations are shown in Supplementary Table 3. (e) RNA, FOXA2 and H3K4me1 profiles of indicated samples in the GATA6 and MNX1 loci. (f) In vivo MPC FOXA2 occupancy is largely recapitulated by in vitro MPCs, but not by other tissues expressing FOXA2. Hierarchical clustering was performed on normalized FOXA2 ChIP-seq signal centered on all 5,760 in vivo MPC FOXA2 peaks. (g) In vitro MPCs recapitulate cell-specific H3K4me1 enrichment observed in chromatin from in vivo MPCs. Aggregation plots show H3K4me1 enrichment at occupancy sites of tissue-specific TFs. Mam.: Mammary Myo.: Myotubes. (h) Genes with ≥3 regions enriched in FOXA2 and H3K4me1 at in vivo MPCs are preferentially expressed in both in vivo and in vitro MPCs. Boxes show RNA interquartile range (IQR) and notches indicate median 95% confidence intervals (n=327 genes). P values were calculated with Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Earlier studies have shown that hESCs-derived pancreatic progenitors express appropriate markers17-20. However, the extent to which they provide a suitable model to study global genome regulation of genuine pancreatic MPCs has not been tested. Several observations validated our artificial progenitors for this purpose, namely: (a) in vitro MPCs recapitulated expression of known pancreatic MPC TFs (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1b), (b) in vitro and in vivo MPCs showed a high correlation of transcript levels (Spearman's ρ=0.5876, P<2.2×10−16, Supplementary Fig. 1c) and of transcript enrichment relative to other human tissues (Spearman's ρ=0.5881, P<2.2×10−16, Fig. 1b,c, Supplementary Fig. 1d), and (c) the transcripts that are selectively enriched in either in vitro or in vivo MPCs relative to 22 non-pancreatic tissues (Fig. 1b) share common functional annotations, including pancreas development, chordate embryonic development, and WNT signaling (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Table 3). The enrichment of WNT signaling genes included numerous non-canonical WNT regulators, including FZD2, SFRP5, CELSR2, and VANGL2 (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Table 3), whose orthologs have also been listed as selectively expressed in mouse embryonic pancreatic buds (Supplementary Table 4)21,22, suggesting an evolutionary conserved signaling mechanism operating in early pancreas development. This indicates that despite the artificial origin of in vitro MPCs, and the presence of non-epithelial cell types in dissected embryonic pancreas, there are meaningful similarities in their transcriptomes. Integration of these datasets allowed us to define a core set of 500 genes that showed enriched expression in both sources of pancreatic MPCs (Supplementary Table 5), providing a resource to study genes important for early human embryonic pancreas development.

We next compared FOXA2 binding sites in the in vivo and in vitro pancreatic MPCs with other tissues where this TF is expressed (embryonic liver, adult liver, and adult pancreatic islets)(Fig. 1e,f). FOXA2 largely bound to the same genomic regions in both sources of MPCs, yet bound to different genomic sites in other tissues, despite that a similar sequence motif was recognized in all cases (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 1e). Furthermore, in vivo and in vitro MPCs shared cell-specific H3K4me1 enrichment at in vivo FOXA2-bound sites (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1f). Finally, genes with two or more nearby H3K4me1-enriched FOXA2-bound regions in the in vivo MPCs showed enriched mRNA expression in both in vivo and in vitro MPCs relative to 23 control tissues (Fig. 1h). Thus, in vitro and in vivo MPCs showed common FOXA2 and H3K4me1 occupancy patterns near pancreatic MPC-enriched genes. Taken together, our analyses suggest that artificial pancreatic MPCs recapitulate significant transcriptional and epigenomic features of genuine embryonic MPCs, and can thus be exploited as a tool to study genome regulation of human pancreas development.

An atlas of human pancreatic MPC enhancers

To map active cis-regulatory elements in human pancreatic MPCs, we employed in vitro MPCs to profile H3K27ac, which marks active transcriptional enhancers23,24. We then selected all genomic regions that showed H3K27ac and H3K4me1 enrichment in chromatin from in vitro MPCs, and that were also enriched in H3K4me1 in human Carnegie Stage 16-18 pancreas (in vivo MPCs). After exclusion of annotated promoters, this disclosed 9,669 regions that carried an active enhancer chromatin signature in pancreatic MPCs (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2a,b, Supplementary Table 6).

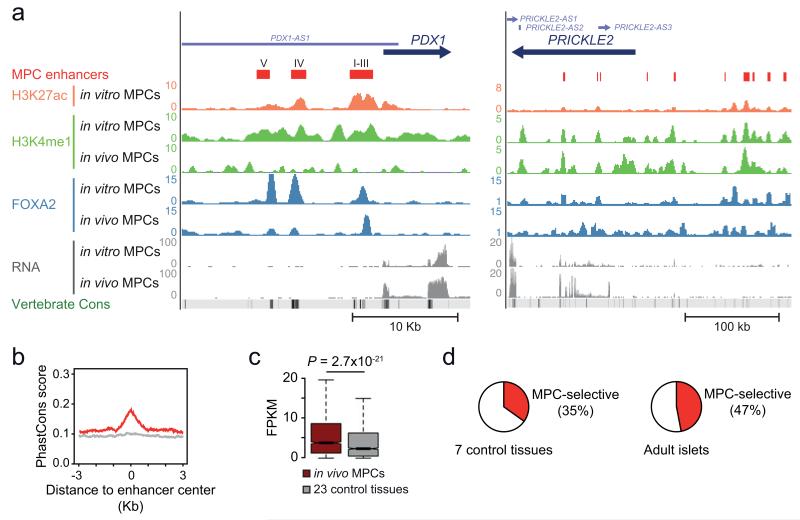

Figure 2.

A compendium of active enhancers in human pancreatic MPCs. (a) Predicted enhancers were defined by enrichment in H3K27ac and H3K4me1 (see schematic in Supplementary Fig. 2b). Shown are examples in the vicinity of PDX1, including a previously unannotated enhancer which we coin Area V, upstream of known enhancers (Areas I-IV)42,43, and several enhancers near PRICKLE2, a non-canonical WNT signaling component (Supplementary Table 4). (b) MPC enhancer sequences are evolutionary conserved (17 species vertebrate PhastCons score). Conservation plots of random non-exonic sequences are shown as a light gray line. (c) Genes that are associated with 3 or more MPC enhancers show enriched expression in dissected in vivo MPCs relative to 23 other tissues. The boxes show interquartile range (IQR) of RNA levels, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR or extreme values, and notches indicate 95% confidence intervals of the median. P value was calculated with Wilcoxon rank-sum test (n=2,093 genes). (d) Many MPC enhancers are tissue- and stage-selective. We defined enhancers of 8 control tissues using identical criteria as in MPCs (Supplementary Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 8) and show the proportion of enhancers that are inactive in at least 6 out of 7 non-pancreatic tissues (left) or inactive in adult pancreatic islets (right).

The cis-regulatory map included known pancreatic MPC enhancers (Fig. 2a). As expected, predicted MPC enhancer sequences showed strong evolutionary conservation (Fig. 2b), they were preferentially located near genes with increased expression in Carnegie Stage 16-18 pancreas (Fig. 2c), and they were often associated with core MPC-specific genes (Hypergeometric test, P<10−15). In keeping with the cellular and temporal specificity of enhancers, 35% of pancreatic MPC enhancers showed no overlap with active enhancers from at least six of seven non-pancreatic tissues, and were thus defined as MPC-selective enhancers (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2c, Supplementary Tables 7,8). Notably, 47% showed no overlap with enhancers from adult human islets25 (Fig. 2d). As expected from this cell-specific and stage-specific profile, genes near MPC-selective enhancers have functions relevant for pancreas development (Supplementary Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table 9). This analysis therefore uncovered a large collection of candidate active enhancers of the nascent human embryonic pancreas.

A combinatorial code for pancreatic MPC enhancers

To understand the regulatory sequence code that drives early human pancreas development, we examined this collection of MPC enhancers and found that the most enriched sequence motifs match binding sites of known pancreatic regulators, including FOXA, HNF1, SOX, PDX1, GATA, and ONECUT (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3a, Supplementary Tables 10,11). The single most enriched recognition motif, however, matched that of TEA domain (TEAD) TFs, which have not been previously implicated in pancreas development (Fig. 3a). TEAD motifs were similarly enriched in regions bound by FOXA2 in Carnegie Stage 16-18 pancreas as well as in vitro MPCs, but not in regions bound by FOXA2 in adult pancreatic islets or liver (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Because TFs are thought to function in a combinatorial manner, we identified combinations of multiple motifs that were most enriched at pancreatic MPC enhancers relative to non-pancreatic enhancers (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 12). This showed that the most enriched combinations contained TEAD motifs adjacent to known pancreatic TF recognition sequences (Fig. 3c). These results therefore revealed that pancreatic MPC enhancers contain combinations of motifs that match known as well as previously unrecognized pancreatic regulatory TFs.

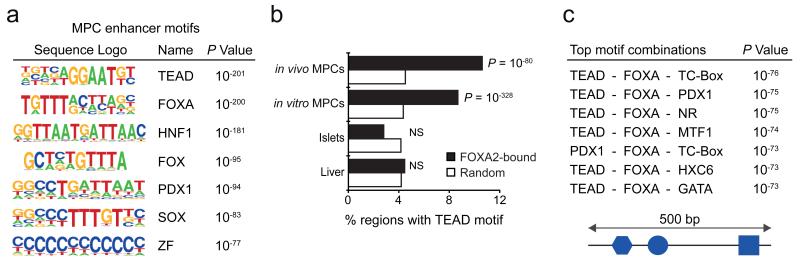

Figure 3.

MPC enhancers are enriched in DNA binding motifs for TEAD and known pancreatic transcription factors. (a) TEAD recognition motifs were strongly enriched in a de novo motif search in MPC enhancers. Other enriched matrices match binding sites of known pancreatic regulators. See Supplementary Tables 10 and 11 for a complete list of motifs enriched in MPC and MPC-selective enhancers, respectively. (b) TEAD motifs are highly enriched at genomic regions bound by FOXA2 in both in vivo and in vitro MPCs, but not at regions bound by FOXA2 in islets or liver. Binomial distribution P values were obtained using HOMER44. NS: non-significant. (c) Combinations of recognition motifs for TEAD and other pancreatic regulators are specifically enriched in pancreatic MPC enhancers. We searched for combinations of 3 sequence motifs that were contained within 500 bp and were most enriched in pancreatic MPC enhancers relative to 8 other tissue enhancers. The top 50 most enriched motif combinations are shown in Supplementary Table 12.

TEAD1 is a core component of pancreatic progenitor cis-regulatory modules

Mouse and human genetics have revealed numerous TFs that are essential for the specification, growth and morphogenesis of pancreatic MPCs3,26, yet very little is known about how such factors promote these processes. The availability of large numbers of in vitro MPCs allowed us to perform ChIP-seq analysis to profile the occupancy sites of several TFs that are essential for early pancreas development, namely HNF1B10, ONECUT111, PDX18,9 and GATA65-7, in addition to FOXA212 (Supplementary Table 2). Based on our computational predictions we also profiled TEAD1, a TEAD homolog that is highly expressed in MPCs from human embryonic pancreas (Supplementary Fig. 4a), defining binding sites for a total of six TFs in human MPCs (Fig. 4a).

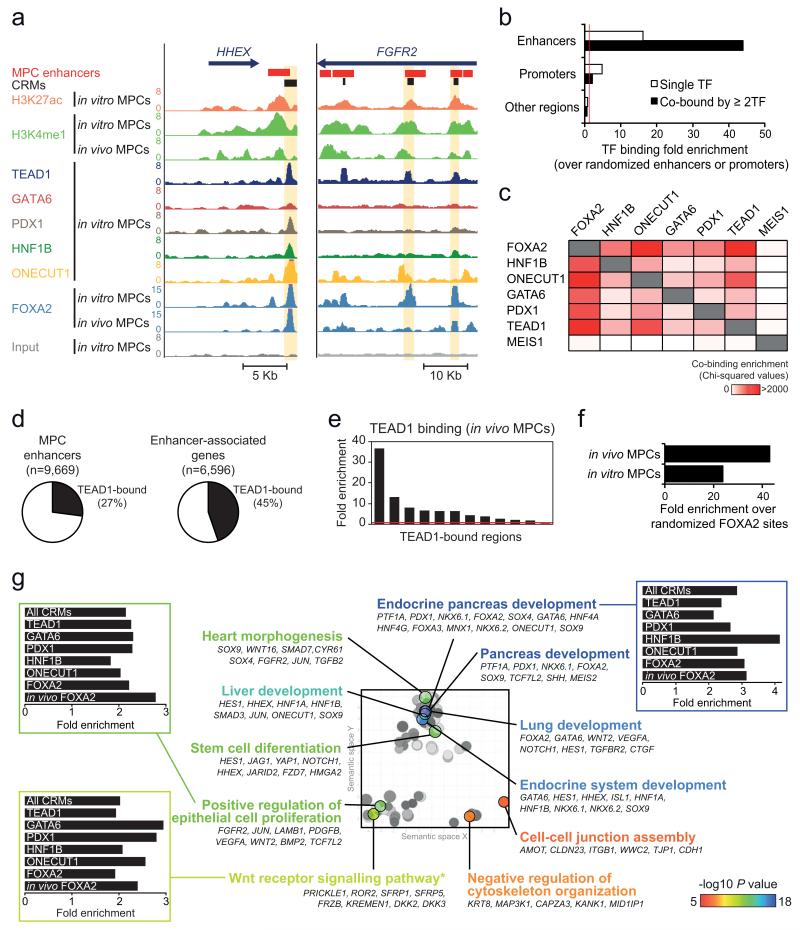

Figure 4.

TEAD1 is a core component of human pancreatic MPC cis-regulatory modules (CRMs). (a) ChIP-seq was used to locate binding sites of 6 TFs in MPCs, as illustrated in two loci encoding pancreatic TFs. CRMs were defined as enhancer regions with ≥2 overlapping TF-bound sites. Examples are highlighted in yellow. (b) TFs preferentially occupy MPC enhancers, and this is most pronounced for regions bound by ≥2 TFs. Binding enrichment was calculated over 1,000 permutations of enhancer or promoter genomic positions in the mappable genome. For comparison we analyzed all other genomic regions after exclusion of MPC enhancers or promoters. Red line indicates a fold enrichment of 1. (c) Pancreatic TFs co-occupy genomic regions, and TEAD1 shows a similar co-occupancy pattern as other known pancreatic TFs. Binding sites of MEIS1 in a non-pancreatic cell type were used as control. The heatmap depicts Chi-squared values for all pairwise comparisons of observed vs. expected co-binding. The latter was estimated by permuting each set of TF peaks independently 1,000 times. (d) Over 1/4 of MPC enhancers are bound by TEAD1, whereas 45% of genes associated with MPC enhancers include at least one TEAD1-bound enhancer. (e) ChIP-qPCR with in vivo MPCs confirms TEAD1 binding at in vitro MPC TEAD1-bound regions (regions and associated genes in Supplementary Table 15). (f) TEAD1 binding is enriched in regions bound by FOXA2 in either in vitro or in vivo MPCs. We calculated TEAD1-FOXA2 co-binding over the median expected value after generating 1,000 permutations of in vitro or in vivo FOXA2 peak positions. (g) CRMs underlie a pancreas developmental regulatory network. The 2,956 genes associated with CRMs were functionally annotated using GREAT45, and REVIGO46 was used to visualize annotation clusters. The most significant terms from each cluster are highlighted according to the P value color scale. Bar graphs show that GO terms are similarly enriched in CRMs bound by different TFs. *Several WNT pathway related-terms were enriched, although manual annotation in this category revealed that most gene were either non-canonical WNT signaling mediators or antagonists of canonical WNT signaling (full annotations in Supplementary Table 17).

All six TFs preferentially bound to known cognate recognition sequences that were widely distributed throughout the genome (Supplementary Fig. 4b), although there was marked preference for binding to MPC enhancers and annotated promoters (Fig. 4a,b, Supplementary Fig. 4c-d). Furthermore, the six TFs very frequently co-occupied the same regions, predominantly at MPC enhancers (Fig. 4a,b, Supplementary Fig. 4c-e). For example, enhancers bound by PDX1 and GATA6, the TFs with the lowest total number of binding sites, showed co-binding by at least one of the other five TFs in 94.5% and 95.3% of instances, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Remarkably, TEAD1 showed a similar co-binding pattern as the five known pancreatic regulators analyzed in this study (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 4d,e). Consistently, strong TEAD1 occupancy was not only observed at known targets from other cell types, such as CTGF or CYR6127 (Supplementary Fig. 4f, Supplementary Table 13), but also in 27% of all pancreatic MPC enhancers. Furthermore, 45% of enhancer-associated genes had at least one TEAD1-bound enhancer (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 14). In support, we confirmed TEAD1 binding to 10/12 enhancers in Carnegie Stage 16-18 embryonic pancreas (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Table 15), and observed that TEAD1 binding was enriched in enhancers bound by FOXA2 in vivo (Fig. 4f). Altogether, computational and ChIP-seq analysis indicate that known pancreatic regulatory TFs show widespread co-binding at MPC enhancers, and that TEAD1 is an unexpected component of this combinatorial TF code.

Given the high degree of TF co-occupancy in MPC enhancers, we defined 2,945 regions within enhancers that are bound by 2 or more TFs, and coined these cis-regulatory modules (CRMs)(Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 4c). CRMs provided greater spatial resolution of cis-regulatory sequences than H3K27ac/H3K4me1-enriched regions alone, which often appear to merge several adjacent evolutionary conserved sequences bound by multiple TFs.

A large number of CRMs mapped near known pancreatic regulatory genes, including HNF1B, FGFR2, HHEX, FOXA2, NKX6-1, and SOX9 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table 16). More generally, CRMs mapped near core MPC-enriched genes (P=3.32×10−12). Notably, spatial clusters of CRMs were associated to genes that were highly enriched in gene functions relevant for early pancreas development, including epithelial cell proliferation and WNT signaling (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Tables 17-19). Notably, non-canonical WNT regulatory genes were enriched near clusters of CRMs (P=1.18×10−9)(Supplementary Table 19), in agreement with our transcriptome analysis (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 4) and transcriptome analysis of mouse pancreas development21,22.

Interestingly, CRMs bound by any of the six TFs were associated to the same functional annotations (Fig. 4g). This included TEAD1-bound CRMs, despite that this TF is widely expressed across multiple tissues and developmental stages (Fig. 4g). TEAD1-bound CRMs thus mapped to known or plausible pancreatic regulatory genes including FGFR2, RBPJ, FZD5/7/8, FRZB, JAG1, CDC42EP1, MAP3K1, NKX6-1, HHEX, GATA4, GATA6, FOXA2, HES1, and SOX9 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table 20). This is consistent with a broad combinatorial function of regulatory TFs in the establishment of the MPC-specific transcriptional program.

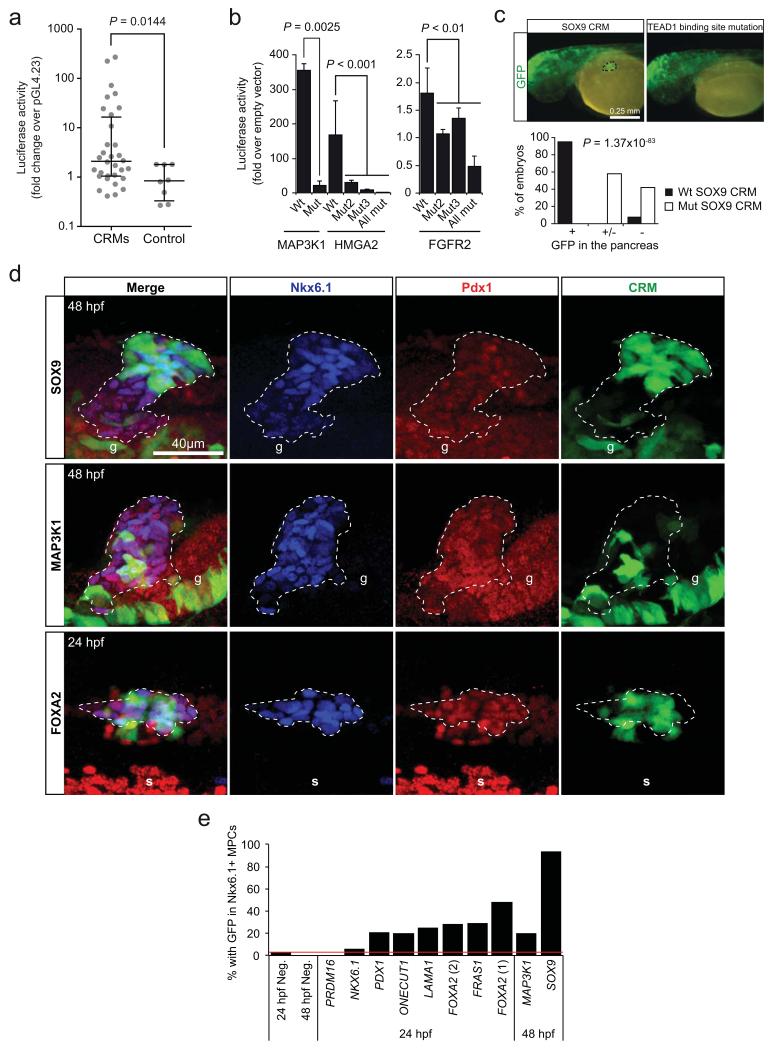

To functionally validate these human embryonic pancreas CRMs, 32 sequences were transfected into in vitro MPCs, and 20 (62.5%) yielded significant enhancer activity (Mann-Whitney for CRMs vs. control regions, P=0.0144)(Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 5a). To directly test the function of TEAD1 binding to CRMs, we mutated TEAD recognition sequences in three CRMs that were bound by TEAD and other pancreatic TFs, which disrupted enhancer activity in all cases (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Functional validation of CRMs as transcriptional enhancers. (a) Thirty two CRMs were cloned into the pGL4.23 vector and tested in reporter assays, where 20 (62.5%) yielded significant activation of a minimal promoter driving luciferase in human pancreatic MPCs. Lines represent median with IQR. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test P value is shown (n=4 replicate wells). (See also Supplementary Fig. 5a). (b) TEAD binding sites are essential for MPC enhancer activity. Mutation of one or more canonical TEAD binding sites in three CRMs abolished their activity in luciferase reporter assays in in vitro MPCs. Locations of the FGFR2 and MAP3K1 CRMs are highlighted in Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure 4c, respectively. Two-tailed t-test P values are listed in Supplementary Table 22 (n=3-4 transfections per construct, in 1-2 independent experiments). Error bars represent SEM. (c,d) A TEAD1-bound CRM near SOX9 (Fig. 7e) was fused to a minimal promoter and GFP, and injected into zebrafish embryos. In (c), a SOX9 CRM drove strong GFP expression in the pancreatic domain of 48 hpf zebrafish embryos (dotted circle, left panel), which was disrupted by a mutation in the TEAD recognition sequence (right). A midbrain-specific enhancer was used as internal control of transgenesis. Note that this experiment assessed activity of a single SOX9 CRM, which does not necessarily fully recapitulate the expression of endogenous sox9b. In the graph, +, +/− and − represent strong, weak and absent GFP expression in the pancreatic domain, respectively (n=110-140 embryos per condition, Chi-squared test P=1.37×10−83). (d) Immunofluorescence analysis of pancreatic MPCs in zebrafish embryos injected at one- to two-cell stage with constructs containing SOX9, MAP3K1 and FOXA2 CRMs driving GFP. Images show GFP in Pdx1+/Nkx6.1+ cells at 24/48 hpf, as indicated. In total, 8/10 CRMs yielded activity in Pdx1+/Nkx6.1+ progenitors (see also Supplementary Fig. 5b). The pancreatic progenitor domain is revealed by co-expression of Pdx1+ and Nkx6.1+ (dashed lines). Note that in zebrafish Nkx6.1 is specific to MPCs within embryonic pancreas47. g: Pdx1+ gut cells, s: somites showing crossreactivity with anti-Pdx1 serum. (e) Percentage of transgenic embryos with CRM-driven GFP expression in MPCs, or in negative controls (neg.) (quantifications shown in Supplementary Table 21).

We selected 10 CRMs for validation using zebrafish transgenesis, and in 8 cases we demonstrated enhancer activity in Pdx1+/Nkx6.1+ pancreatic endoderm MPCs (Fig. 5c-e, Supplementary Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 21). Amongst these, we examined a CRM in the locus encoding SOX9, an essential regulator of the self-renewal of mouse pancreatic MPCs that is mutated in humans with pancreas hypoplasia13,14 (Fig. 5c,d). This CRM showed pancreas-specific enhancer activity in zebrafish transgenics, whilst mutation of the TEAD recognition sequence abolished enhancer activity, providing further confirmation that TEAD1 binding is required for the in vivo function of pancreatic MPC enhancers (Fig. 5c).

Taken together, this analysis provided a rich source of cis-regulatory elements in human embryonic pancreatic progenitors. It also revealed widespread co-occupancy of pancreatic developmental TFs at MPC enhancers, and uncovered TEAD as a hitherto unrecognized core component of this combination of TFs.

TEAD and YAP regulate a pancreas developmental program

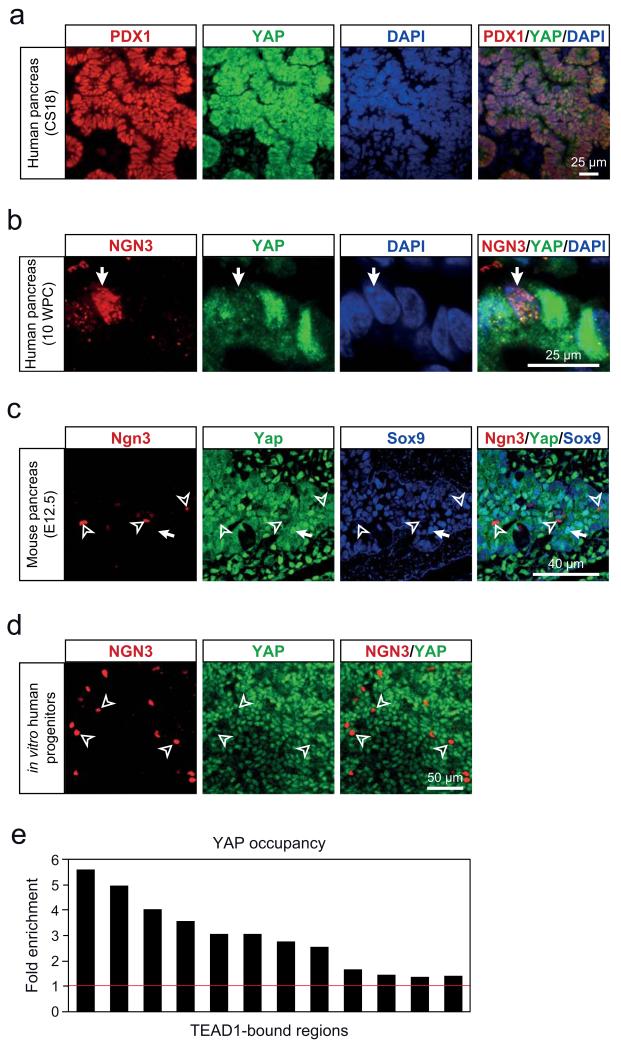

We next examined TEAD-dependent gene regulation during pancreas development. TEAD proteins interact with the active nuclear form of the coactivator Yes-associated protein (YAP). YAP is negatively regulated by Hippo signaling, which triggers YAP phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion27. We examined nuclear localization of YAP throughout differentiation, and found that YAP was highly expressed in the nucleus of hESCs, and subsequently showed low yet detectable immunoreactivity throughout intermediary stages of the in vitro pancreatic differentiation protocol (Supplementary Fig. 6a), as well as in the nucleus of dorsal foregut epithelial cells of Carnegie Stage 10 human embryos (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Strong YAP expression was subsequently observed in the nucleus of in vitro-derived pancreatic MPCs, as well as human and mouse in vivo pancreatic MPCs (Carnegie Stage 18 and E10.5-E14.5 embryos, respectively)(Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 6c-f,h), in keeping with recent descriptions in mice28. By contrast, YAP immunoreactivity was undetectable or delocalized to the cytoplasm in NGN3+ endocrine-committed progenitors, differentiated acinar cells or endocrine cells (Fig. 6b,c, Supplementary Fig. 6c-g,i), although nuclear expression was maintained in ductal cells (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Furthermore, in pancreatic MPCs YAP bound to most tested TEAD1-bound regions (Fig. 6e), similar to what has been observed in other cell types that exhibit nuclear YAP expression27. Thus, during embryonic pancreas development the coactivator YAP shows stage-specific nuclear localization in MPCs. This suggests a YAP-dependent function of TEAD1 during early pancreas development that is confined to MPCs, and is then inactivated upon differentiation of pancreatic lineages.

Figure 6.

YAP is expressed in the nucleus of pancreatic MPCs, and shows co-occupancy with TEAD1 at MPC enhancers. (a) YAP is detected in the nucleus of PDX1+ in vivo MPCs from human Carnegie Stage 18 pancreas. (b) In 10 weeks post-conception (WPC) human pancreas YAP expression is strong in nuclei of PDX1+ progenitors, but shows markedly diminished signal intensity in NGN3+ progenitors (white arrow). Image depicts 5 cells in human embryonic pancreas 10 WPC. (c) Yap is detected in the nucleus of Sox9+ MPCs from mouse E12.5 embryonic pancreas (white arrow), whereas Yap is diffuse or absent in Ngn3+ endocrine progenitor cells (hollow arrowheads). (d) YAP is excluded from the nucleus in hESCs-derived pancreatic NGN3+ progenitor cells (hollow arrowheads). (e) ChIP-qPCR analysis of YAP occupancy in chromatin from in vitro MPCs shows that TEAD1-bound regions are often co-bound by YAP.

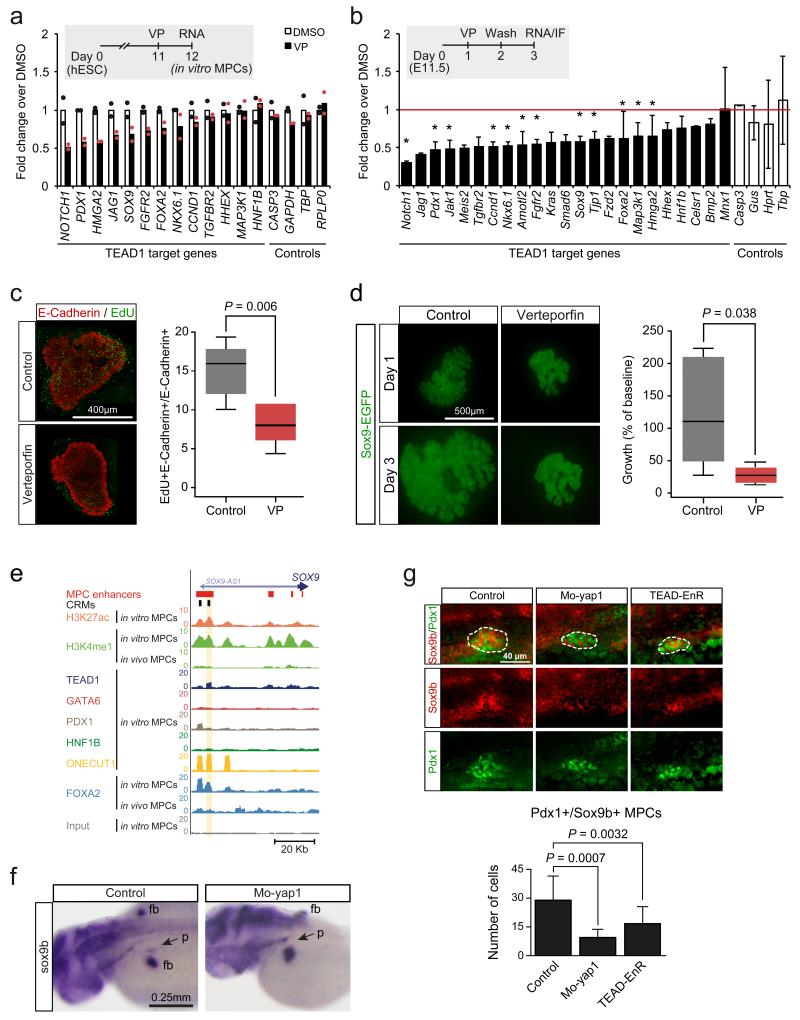

To study YAP-dependent TEAD function in pancreatic MPCs, we first used Verteporfin (VP), a chemical compound that disrupts the TEAD-YAP complex29. VP treatment of human in vitro MPCs and pancreatic bud explants dissected from E11.5 mouse embryos and grown ex-vivo caused decreased expression of a subset of genes associated with TEAD1-bound enhancers, including genes that are established critical regulators of progenitor cell growth in the embryonic pancreas, such as FGFR230 and SOX914,31, as well as mediators of growth regulatory pathways, such as NOTCH1 and the known Hippo target CCND1 (encoding Cyclin D1)(Fig. 7a,b, Supplementary Fig. 4f). Consistently, exposure of mouse explants to VP during 24 h significantly reduced epithelial cell proliferation by 39% (P=0.006)(Fig. 7c), and limited the growth of pancreatic buds to 27% of control organs after 3 days in culture (P=0.038)(Fig. 7d). These results suggest that the TEAD-YAP complex has direct effects on several known regulators of pancreatic progenitors, and is required for the proliferation and growth of early embryonic pancreas epithelium.

Figure 7.

TEAD and YAP regulation of pancreas development. (a) Human in vitro MPCs were incubated with VP 24 hours to disrupt TEAD-YAP interactions, causing downregulation of genes associated with TEAD1-bound enhancers. Data was normalized by PBGD. Bars show mean values from 2 independent experiments, and points represent mean of 2 technical replicates. (b-d) VP treatment of E11.5 mouse pancreatic explants downregulated orthologs of TEAD1-bound genes, inhibited proliferation and reduced growth of pancreatic epithelial cells. Explants were treated with VP for 24 hours, washed, and incubated 24 hours before analysis. Data was normalized to Gapdh. *Two-tailed t test P<0.05 (individual values listed in Supplementary Table 22). Error bars represent SD from 3 independent experiments (each with n=2-4 embryos/condition). In (c) the percentage of proliferating epithelial cells was quantified with E-Cadherin and EdU immunolocalization. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney P value is shown for 3 experiments (each with n=2-3 pancreas/condition). In (d) GFP+ area in Sox9-EGFP transgenic embryo explants is shown at day 3 compared to day 1. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test P values are shown for 3 experiments (each with n=2-4 buds/condition). In (c) and (d) boxes are IQR and median, whiskers 1.5 × IQR or extreme values. (e) Snapshot of the human SOX9 locus, encoding a regulator of MPC growth14. The CRM tested in functional assays in Figure 5c and Figure 7f is highlighted. (f) yap1 inhibition decreased pancreatic sox9b expression. Injection of Mo-yap1 caused a reduction or absence of sox9b mRNA in the pancreatic domain (arrow) in 50/102 48 hpf embryos. Control embryos showed pancreatic sox9b expression in 100/100 embryos (Chi-squared P 2.61×10−15). Note that control and morphant embryos always showed sox9b expression in fin buds (fb). (g) Injection of Mo-yap1 (n=10 embryos) or the TEAD-EnR dominant negative (n=12 embryos) caused a decreased number of sox9b+/Pdx1+ pancreatic progenitors (dotted lines) in 24 hpf embryos vs. controls (n=9 embryos). Sox9b was detected by in situ hybridization and Pdx1 by immunofluorescence. The graph reflects the total number of pancreatic progenitors in each embryo. Mo-yap1 also increased ectopic expression of pancreatic markers (Supplementary Figure 7b). Student’s t test P values and SD are shown.

To further test the in vivo function of YAP and TEAD in pancreas development, we performed genetic perturbations in zebrafish. In keeping with our chemical inhibition studies, morpholino inhibition of yap1 caused a reduction in the pancreas size at 48 hpf, with hypoplasia in 65% of embryos (n=46)(Supplementary Fig. 7a), and a marked reduction of sox9b-expressing pancreatic MPCs (Fig. 7f,g). This effect was partially rescued by co-injection with yap1 mRNA, confirming the morpholino specificity (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In agreement, zebrafish embryos expressing a TEAD protein fused to the transcriptional repressor domain of Engrailed32, phenocopied the morpholino inhibition of yap1 (Fig. 7g, Supplementary Fig. 7a). In summary, inhibition of Yap1 and Tea domain proteins in zebrafish suppressed pancreatic sox9b expression and cell growth, in agreement with our mouse and human in vitro studies. Given that TEAD directly regulates a SOX9 enhancer (Fig. 5c), and that SOX9 regulates mouse and human pancreatic MPC growth13,14,31, we hypothesize that the effects of TEAD and YAP on pancreatic progenitors are partially mediated through SOX9. Taken together, genetic and chemical inhibitor experiments support a model whereby YAP coactivation of TEAD1-bound MPC enhancers regulate a genomic regulatory program that is required for the expression of stage-specific genes and for the outgrowth of pancreatic progenitors.

DISCUSSION

We have created and validated a map of active enhancers in human embryonic pancreatic progenitors. This effort expands the current list of known active enhancers in the embryonic pancreas from a handful of examples to thousands of stage-specific cis-regulatory elements. This included clustered enhancers, which were linked to a core cell-specific transcriptional program, in analogy to earlier studies in diverse cellular lineages25,33. Our studies also show that pancreatic embryonic progenitor cells derived from hESCs mimic salient transcriptional and epigenomic features of pancreatic progenitors from human embryos, illustrating the power of pluripotent stem cell biology to dissect regulatory mechanisms underlying human embryogenesis.

This atlas of pancreatic MPC enhancers should facilitate the discovery of non-coding mutations that cause human diseases linked to abnormal pancreas development. In support for this claim, H3K4me1, PDX1 and FOXA2 binding data from in vitro MPCs enabled the identification of recessive mutations that map to a previously unannotated enhancer of PTF1A and cause isolated pancreas agenesis34. Sequence variation in MPC enhancers could hypothetically increase the susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus by impacting pancreas development and thereby affecting the pancreatic beta cell mass. Finally, germ-line or somatic variants in MPC enhancers could also influence the development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which has been associated with dedifferentiation of adult exocrine cells35,36 and to YAP activation37,38.

Our study identifies binding sites of several TFs that are known to be essential for early pancreas development, and show that they co-occupy pancreatic MPC enhancers, consistent with a combinatorial TF code. Unexpectedly, our results revealed that TEA domain proteins – exemplified by TEAD1 – and the coactivator YAP are central components of this combinatorial code, activating key regulatory genes and promoting the outgrowth of pancreatic MPCs.

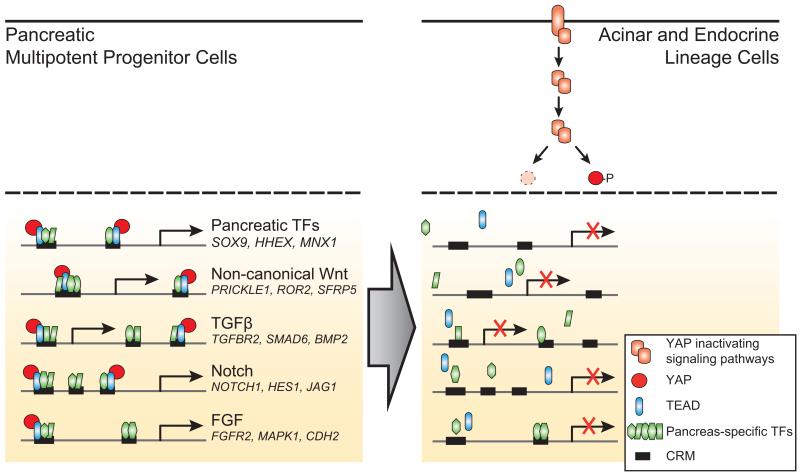

The TEAD-dependent transcriptional mechanism provides a means for signal-responsive dynamic regulation of MPC enhancers during pancreas development. The coactivator YAP is a component of the Hippo signaling cascade, which phosphorylates YAP, leading to its retention in the cytoplasm or to its degradation39. Our data shows that, as human pancreatic MPCs transition to endocrine and acinar lineages, YAP undergoes immediate nuclear exclusion and downregulation. Based on our chemical and genetic experiments, this dynamic change is expected to lead to inhibition of MPC enhancers during pancreatic differentiation.

Two recent reports showed that pancreas-specific disruption of the upstream Hippo kinases Mst1/2 leads to increased proliferation of adult acinar pancreatic cells, which acquire a duct-like morphology, exhibit increased nuclear localization of Yap and show ectopic expression of the TEAD target Sox928,40. These observations do not address whether Hippo signaling or TEAD are important for pancreatic progenitors, but they are consistent with failed suppression of a progenitor program in adult cells, and therefore support the predictions from our findings. Collectively, existing data suggests a model whereby TEAD proteins provide a regulatory switch that activates a stage-specific transcriptional program in pancreatic MPCs, and facilitates signal-responsive inactivation of this program during pancreatic cell differentiation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

YAP/TEAD-dependent activation provides a regulatory switch for pancreatic MPC enhancers. A significant number of pancreatic MPC enhancers is co-bound by known stage-specific TFs along with TEAD and YAP. During pancreatic differentiation YAP is rapidly excluded from the nucleus and its expression is reduced, causing inactivation of MPC stage-specific enhancers. This simplified model depicts inhibition of YAP through Hippo kinase-induced phosphorylation or degradation, although additional non-mutually exclusive mechanisms for dynamic inhibition of YAP signaling are plausible. The model is supported by evidence showing that chemical or genetic inhibition of YAP and TEAD function causes inhibition of MPC enhancers.

Further studies should explore this regulatory mechanism in human disease. The reactivation of the YAP/TEAD-dependent MPC enhancer program in adult acinar cells could conceivably activate a progenitor-like cellular program during early stages of pancreatic carcinogenesis36,41, and/or contribute to YAP-dependent cancer progression37,38. This same genetic program could potentially be exploited to control growth and differentiation during the generation of artificial pancreatic cells.

METHODS

Human samples

Human embryos were collected with informed consent with approval from the North West Regional Ethics Committee (08/H1010/28) following termination of pregnancy and staged immediately by stereomicroscopy according to the Carnegie classification48. The collection, use and storage of material followed guidelines from the UK Polkinghorne Committee, legislation of the Human Tissue Act 2004 and the Codes of Practice of the Human Tissue Authority, UK. The analysis of human embryonic tissue was also approved by the Comitè Ètic d’Investigació Clínica del Centre de Medicina Regenerativa de Barcelona and Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. Human embryonic pancreas and liver were dissected at Carnegie Stage (CS) 16-18, which correlates to ~37-45 days post-conception. These stages were the earliest at which pancreatic epithelial cells could be efficiently dissected away from surrounding mesenchyme with minimal contamination. After isolation tissues were rinsed with PBS, incubated 10 min in 1% formaldehyde, 5 min in 125 mM Glycine, rinsed in PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) at 4°C, and snap-frozen and stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted using Trizol and DNase.

Human ESCs (H9, WiCell) were imported under guidelines from UK Stem Cell Bank Steering Committee (SCSC10-44). Differentiation of pancreatic MPCs has been described17. Briefly, definitive endoderm (DE) was induced by growing hESCs in CDM-PVA + Activin-A(100 ng/mL), BMP4(10 ng/mL), bFGF(20 ng/mL) and LY(10 μM)(AFBLy). The CDM-PVA AFBLy cocktail was replenished daily, and daily media changes were made until differentiation day 10. After the DE stage (days 1-3), cells were cultured in Advanced DMEM (Invitrogen) with SB-431542(10 μM; Tocris), FGF10(50 ng/ml; Autogen Bioclear), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, 2 μM; Sigma) and Noggin (150 ng/ml; R&D Systems) during days 4-6. For days 7-9, cells were supplemented with human FGF10 (50 ng/ml; Autogen Bioclear), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, 2 uM; Sigma), KAAD-cyclopamine (0.25 μM; Toronto Research Chemicals) and Noggin (150 ng/ml; R&D Systems). On days 10-12, cells were cultured in human FGF10 (50 ng/ml; Autogen Bioclear), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, 2 uM; Sigma), and KAAD-cyclopamine (0.25 μM; Toronto Research Chemicals).

For RNA-seq and ChIP-seq, cells from 3 independent differentiation experiments were pooled. For ChIP cells were fixed as described above, snap-frozen and kept at −80°C. Total RNAs were extracted from hESCs or differentiated progenitors using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and treated with RNase-Free DNase (Qiagen).

Immunolocalization

Immunolocalization was performed as described16,17,49,50. Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 23.

Pancreatic explants from E12.5 C57BL/6 mouse embryos and whole mount stainings were performed as described51 with modifications. Briefly, pancreas were fixed 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked in 0.5% Triton X-100/10% FBS/PBS overnight at 4°C, incubated 24 hours with primary antibody at 4°C, then overnight with secondary antibody at 4°C and finally DAPI staining. EdU staining was performed using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor® 488 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen). All images presented show representative results obtained from at least 3 independent experiments.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Either 7 human CS16-18 pancreatic buds, 4 CS16-18 liver buds (as described above), or ~10 million cells from a pool of 3 pancreatic progenitor in vitro differentiation experiments, were pooled in 1 mL of lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and sonicated 10-15 cycles essentially as described25,52. We verified that a substantial portion of chromatin fragments were in the 200-600 bp range by gel electrophoresis.

ChIP was performed with 50-300 μL of sonicated chromatin as described25,53,54, with minor modifications. Briefly, sonicated chromatin was diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (0.75% Triton X-100, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Hepes at pH8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail) to achieve a final SDS concentration of 0.2%, pre-cleared with A/G sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) for 1 hour, incubated overnight at 4°C with 1-1.5μg antibodies (Supplementary Table 23), rotated 2 hours at 4°C with A/G sepharose beads, and then sequentially washed and processed25,53,54.

RNA-seq

All samples had RIN >9. RNA-seq was generated from DNase-treated PolyA+ RNA from a CS17 pancreatic bud or from a pool of 3 in vitro pancreatic MPC differentiation experiments, sequencing 90-nucleotide reads with an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. RNA-seq datasets from 23 tissues and their sources are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Reads were aligned to the NCBI36/hg18 genome using TopHat-v1.2.055 with default parameters, allowing only 1 mismatch per read. For comparison of RNA levels, we processed and calculated fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) values for each transcript as described56. For a global comparison of gene expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 1c), we analyzed 44,699 UCSC gene variants expressed at >5 FPKM in at least one sample. Expression values were median-centered and scaled by the root mean square. Spearman correlation values were calculated for each pair.

RNA enrichment analysis

Tissue-selectivity of each transcript was assessed by computing the FPKM coefficient of variance (CV) in the 25 samples described in Supplementary Table 1. To obtain the enrichment of each transcript in each tissue, we calculated Z-scores as the difference between the log2-transformed expression level in the specific tissue and the mean of all tissues, divided by the standard deviation. For detection of MPC-specific transcripts Z-score measurements were calculated without data from islets and either in vitro or in vivo MPCs. We defined tissue-specific genes as those with CV ≥1, expression ≥0.3 FPKM and Z-score ≥1 in any tissue.

Core MPC-specific genes were defined as UCSC annotated genes that were tissue-selective (CV ≥1) and enriched in in vitro MPCs (Z-score ≥1). We then sorted by in vivo MPC enrichment Z-score, and selected the top 500 (Supplementary Table 5).

Functional annotations

Transcript functional annotation was performed with DAVID57, using Gene Ontology (GO) biological process (FAT), Pathways (KEGG, Panther) and annotation clustering. In Fig. 1c, we sorted terms by P value and show the most significant term of each cluster. Annotations are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Genes associated with enhancers and CRMs were analyzed with GREAT-v2.0.245 applying default settings (basal plus extension; significant by both binomial and hypergeometric tests), and annotated with GO Biological Process plus all pathway annotations. Raw binomial P value and binomial fold enrichment were used to present enrichments. Supplementary Tables 9, 17 and 19 list annotations associated with MPC-selective enhancers, CRMs, and CRM clusters, respectively. GO Biological Process terms were further processed with REVIGO46 (0.9 allowed similarity; term size database–whole UniProt; semantic similarity measure–normalized Resnik; cluster definition default parameters) taking the most significant term in each GO cluster.

ChIP-seq

Chromatin from replicate pools of in vitro MPCs was used for FOXA2 and H3K4me1 ChIP-seq experiments. Single libraries were prepared from chromatin pools for all other ChIP-seq experiments, except for FOXA2 in vivo MPC, in which libraries from 2 experiments were sequenced and reads were pooled for alignment. All libraries were prepared with 5-10 ng DNA and sequenced with Illumina HiSeq2000 platform were aligned to NCBI36/hg18 using Bowtie-v0.12.7 (Supplementary Table 2), allowing unique alignment with ≤1 mismatch. Post-alignment processing included in silico extension, signal normalization based on the number of million mapped reads, extension to MACS fragment size estimation (v1.4.0beta), and retention of only unique reads. For signal normalization, the number of reads mapping to each base in the genome was counted with genomeCoverageBed (BedTools-v2.17.0). TF enrichment sites were detected with MACS-v1.4.0beta using default parameters and P<10−10. Background model was defined with input DNA sequence. SICER-v1.03 was used to call H3K4me1-enriched islands with window size =100 bp, gap size=800 bp and fragment size estimated by MACS-v1.4.0beta. Enriched islands were called at FDR<10−3. For H3K27ac-enriched regions gap size was 200 bp. For replicate samples we retained overlapping peaks/islands in replicates. To compute FOXA2 and H3K4me1 signal correlations between duplicates we divided the genome in 1 or 5 Kb bins, respectively, then counted unique reads in each bin and quantile-normalized results. Bins with values <5th percentile in both samples were excluded from the analysis. Pearson correlation values were 0.8-0.9 in all biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. 1g). Public datasets were processed identically (listed in Supplementary Table 2).

TF and H3K4me1 aggregation plots

To compute aggregation plots (Figure 1f) we first selected “tissue-specific regulatory regions”, defined by the intersections of H3K4me1 islands with TF “peaks” in the same tissue. The resulting number of regions were as follows: FOXA2 in in vivo MPCs (2,307), SOX2 in hESCs (5,749), MEIS1 in CD133+ cells (2,210), DNase I peaks containing ETS1 motifs in mammary epithelial cells (14,100) and DNase I peaks containing MEF2A motifs in myotube cells (13,614). Next, regions spanning +/−3 Kb from the center of TF peaks were divided in 100 bp bins. The coverage signal was obtained using coverageBed (BedTools-v2.17.0). Data was quantile normalized after creating 100 bp bins in H3K4me1 islands from each tissue.

Clustering

To compare ChIP-seq signals between tissues (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1f), we generated 6 Kb windows centered on in vivo MPC FOXA2 peaks. Each window was divided in 100 bp and binned signal coverage was quantile normalized as described above. Hierarchical clustering was performed with Cluster358 with similarity metric set to Correlation (uncentered) and average linkage as clustering method. Heatmaps were visualized with Treeview59.

Definition of enhancers and CRMs

Enhancers were defined as H3K27ac islands in the in vitro MPCs that overlapped H3K4me1 islands in both in vitro and in vivo MPCs. We discarded regions overlapping promoters (1 Kb upstream and 2 Kb downstream of RefSeq TSS) or <50 bp. Enhancers in 8 control tissues were defined with analogous criteria based on H3K27ac and H3K4me1 islands (Supplementary Table 8).

To define CRMs we merged all in vitro MPC TF peaks that were <500 bp apart, and retained 2,945 regions bound by at least 2 different TFs that overlapped MPC enhancers by at least 1 bp.

Clusters of CRMs were defined as described25, essentially as any group of ≥3 CRMs in which all adjacent CRMs were separated by less than the 25th-percentile of chromosome-specific randomized distances.

Enhancer selectivity

MPC-selective enhancers were defined as those that showed no overlap with an enhancer from at least 6 out of 7 control tissues (hESCs, fetal muscle, fetal stomach, fetal thymus, mammary epithelial cells, myotubes and osteoblasts).

Conservation

Conservation was assessed in +/−3 Kb windows centered in enhancers, using average vertebrate PhastCons score from 17 species for 20 bp bins.

Motif analysis

De novo motif discovery was performed with HOMER44. For enhancers we searched for either short (length=6,8,10,12) or long (length=14,16,18,20) motifs as described previously25, retaining non-redundant matrices (Pearson correlation <0.65) with P<10−50. Motifs were annotated using HOMER44, TOMTOM60 and manual comparisons.

All possible combinations of 3 motifs from the 23 enriched motifs contained within 500 bp regions were computed in MPC enhancers vs. enhancers from 8 other tissues. We calculated eight MPC vs. control tissue fold-enrichment and P values (Chi-squared test), and then combined them in a unique P value for each motif combination with a Z-weighted method61. Supplementary Table 12 shows the top 50 most enriched combinations.

For TF peaks HOMER analysis was performed in 200 bp windows centered on peak summits and motif lengths were set to 8, 10 and 12 bp. Co-enriched motifs were manually curated to exclude redundant motifs. Known DNA binding motifs were associated to the de novo recovered matrix only if the HOMER score was >0.7.

Binding and co-binding enrichment analysis

To assess the enrichment of TF binding and co-binding in enhancers or promoters, the positions of the enhancers or promoters were randomized in all mappable hg18 coordinates using ShuffleBed (BEDTools-v2.17.0). Mappable regions were defined as those not annotated as genome gaps and with score of 1 in the CRG Mappability 50 bp track of the UCSC browser62. Binding enrichment was calculated over the median of 1,000 permutations.

Co-bound regions were defined with intersectBed (BEDTools-v2.17.0) as regions bound by ≥2 TFs. To calculate TF co-binding enrichment, we shuffled each TF individually in the mappable genome, and calculated the overlap with sites bound by the other TFs (median of 1000 permutations generated by ShuffleBed, BEDTools-v2.17.0). Chi-squared test was applied to assess the enrichment of each combination of 2 TFs over expected co-binding. For comparison, we applied the same pipeline to define “co-binding” between MEIS1 in CD133+ cells and the six MPC TFs (Supplementary Table 2).

Enhancer function assays in human cells

The pGL4.23[luc2/minP] vector (Promega) was modified by inserting a Gateway cassette upstream of the minimal promoter (pGL4.23-GW) for subsequent cloning of CRMs and control sequences. These 500-2000 bp sequences were amplified from human genomic DNA with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs), cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen), shuttled into pGL4.23-GW, and assessed by Sanger sequencing and restriction enzyme digestion. To mutate CRMs, we replaced a 3 bp sequence of the core of TEAD motifs, as this was previously shown to disrupt TEAD binding27, and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Oligonucleotides are available in Supplementary Table 15.

At day 10 of the differentiation protocol, cells were transfected in 24-well plates with pGL4.23-CRM plasmids (400 ng) and Renilla normalizer plasmid (4 ng) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Luciferase was measured at day 13 with Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The results shown represent the average and SEM of 3 (HMGA2, GLIS3 and MAP3K10) or 4 (all other CRMs and all negative controls) independent transfections per construct. Eight of 32 plasmids in Figure 5a and Supplementary Figure 5a, and 6 of the 9 CRMs in Figure 5b were retested in independent experiments that yielded comparable results. Statistical significance was assessed with two-tailed Student’s t test using all experiments (see Supplementary Table 22).

Pancreatic explant experiments

Mouse experiments were approved by the Comitè Étic d’Experimentació Animal (University of Barcelona) in accordance with national and European regulations. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. Pancreatic explants were carried out as described63 with minor modifications. Dorsal pancreatic buds from E11.5 CD-1 mouse embryos were cultured in RPMI medium with 10% FBS for 16 hours (day 1) prior to Verteporfin (VP) 0.1 μM (Atomax) or DMSO (control) treatment 24 hours in RPMI 3% FBS. After 24 hours (day 2), drug was washed out and buds were cultured 1 day in RPMI 10% FBS (day 3).

For quantitation of explant growth we used Sox9-EGFP transgenic embryos, which enabled visualization of pancreatic epithelial progenitors. We used ImageJ 1.46a to measure the area of EGFP-expressing cells on days 1 and 3. We performed 3 independent experiments, and examined 2-3 pancreas per condition in each experiment. We expressed areas as percentage of the baseline in the same explant, and used Mann-Whitney test to determine significance. Data failed to show normal distribution with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

To study epithelial cell proliferation, explants were exposed to EdU (1 μM) after VP treatment for 30 min and analyzed 24 hours later. We examined 2-4 pancreas per condition in each of 3 independent experiments. Mann-Whitney test was used for statistical significance.

We obtained RNA from pools of ≥3 pancreatic buds using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and collected 3 separate pools from independent experiments. qRT-PCR was performed using a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Each sample pool was amplified in duplicate using Gapdh for normalization. Oligonucleotides are shown in Supplementary Table 15. Statistical significance was assessed with two-tailed Student’s t test.

VP experiments in human progenitors

In vitro MPCs were subjected to VP (10 μM) or DMSO treatment for 16 hours in duplicate on day 12 of the differentiation protocol. The drug was washed out with PBS and RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen. Reverse transcription was carried out with 0.5 μg RNA using Superscript II (Invitrogen) and qPCR was performed using SensiMiX (Quantace). Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 15 and in reference17. qPCR reactions were normalized to PBGD and analyzed by two-tailed t test.

Zebrafish experiments

Zebrafish embryos from the same cross were randomly selected for the control, morphant (Mo-yap1), dominant negative (TEAD-EnR) and rescue (Mo-yap1+yap1 mRNA) conditions. Five nl of 2 mM morpholino targeting a splice junction of yap1 (yap1-Mo, 5′- AGCAACATTAACAACTCACTTTAGG -3′; previously reported64) were injected in yolk of 1- to 2-cell stage zebrafish embryos. Morpholino activity was confirmed by qRT-PCR (oligonucleotides 5′-TGCCAGACTCATTCTTCACG-3′, 5′-TGGGAACCTTGCTTTACTGG-3′). For rescue experiments, yap1 mRNA (50 pg) was co-injected with the Morpholino. The mRNA of mouse Tead2 fused with engrailed repressor domain (TEAD2-EnR) was synthesized using an existing vector57, and 200 pg was injected in the yolk of 1- to 2-cell stage zebrafish embryos. Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. In situ hybridization for Sox9b65 and insulin66 was performed as described67 and revealed with NBT/BCIP substrate in 46-71 embryos per condition. After in situ hybridization, immunolocalization was performed for some embryos using antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 23. The number of Pdx1+/Sox9b+ pancreatic progenitors was counted in each embryo using confocal microscopy, and differences between groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test.

For transgenic analysis of CRMs wild type and mutant, zebrafish embryos from the same cross were randomly selected. DNA fragments were recombined to an enhancer test vector that is sequentially composed of: a Gateway cassette for insertion of CRMs, a gata2 minimal promoter, an enhanced GFP reporter gene, and a strong midbrain enhancer (z48) that works as an internal control for transgenesis. All these elements were previously reported68 and were assembled in a tol2 transposon69. Transgenesis was performed as described68 and embryos were grown to 24 and 48 hours post fertilization (hpf) at 28°C. GFP was documented using an epifluorescence stereomicroscope. Embryos positive for transposon integration were immunostained for simultaneous detection of Nkx6.1 plus either Pdx1 or insulin expression to identify pancreatic progenitors by confocal microscopy. Note that in zebrafish Nkx6.1 is expressed in pancreatic MPCs but not in endocrine cells, unlike mammalian embryos47. For each construct we counted embryos with GFP expression in Nkx6.1+ pancreatic cells (Supplementary Table 21).

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. Work was funded by grants from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (CB07/08/0021, SAF2011-27086, PLE2009-0162 to JF, BFU2013-41322-P to JLG), the Andalusian Government (BIO-396 to JLG), the Wellcome Trust (WT088566 and WT097820 to NAH, WT101033 to JF), the Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, ERC advanced starting grant IMDs (CH-HC and LV) and the Cambridge Hospitals National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre (LV). REJ is a Medical Research Council clinical training fellow. The authors are grateful to Chris Wright (Vanderbilt University) for zebrafish Pdx1 antiserum, John Postlethwait (Purdue University) for a Sox9b clone, Hiroshi Sasaki (Kumamoto University) for a TEAD-EnR clone, to Cellins Vinod and Leena Abifor research nurse assistance, and clinical colleagues at Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The authors thank J. Garcia-Hurtado for technical assistance.

Reproducibility of experiments

Figure 5c shows representative data from one independent experiment with 110-140 zebrafish embryos per condition.

Figure 5d and Supplementary Figure 5b show representative data from 3-4 independent experiments. Each independent experiment consisted of 50-120 injections. The exact number of zebrafish embryos analyzed for each CRM is shown in Supplementary Table 21.

Figure 6a-d, Figure 7c,d,f, Supplementary Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure 6a-i and Supplementary Figure 7b show representative data from 3 independent experiments.

Figure 7g shows representative data from one independent experiment with 9-12 zebrafish embryos per condition.

Supplementary Figure 4a shows representative data from 6 independent experiments. Three immunostainings were performed independently for two human embryos (CS18 and CS19).

Supplementary Figure 7a shows representative data from one independent experiment with 46-71 zebrafish embryos per condition.

Footnotes

Accession numbers. Primary datasets generated in this study are available at ArrayExpress under accession E-MTAB-1990 and E-MTAB-3061. Referenced datasets are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fang H, et al. An organogenesis network-based comparative transcriptome analysis for understanding early human development in vivo and in vitro. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:108. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang H, et al. Transcriptome analysis of early organogenesis in human embryos. Developmental Cell. 2010;19:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan FC, Wright C. Pancreas organogenesis: From bud to plexus to gland. Developmental Dynamics. 2011;240:530–565. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaret KS, Grompe M. Generation and regeneration of cells of the liver and pancreas. Science. 2008 doi: 10.1126/science.1161431. doi:10.1126/science.1161431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lango Allen H, et al. GATA6 haploinsufficiency causes pancreatic agenesis in humans. Nat Genet. 2012;44:20–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xuan S, et al. Pancreas-specific deletion of mouse Gata4 and Gata6 causes pancreatic agenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3516–3528. doi: 10.1172/JCI63352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasco M, Delgado I, Soria B, Martín F, Rojas A. GATA4 and GATA6 control mouse pancreas organogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3504–3515. doi: 10.1172/JCI63240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Offield MF, et al. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nat Genet. 1997;15:106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haumaitre C, et al. Lack of TCF2/vHNF1 in mice leads to pancreas agenesis. PNAS. 2005;102:1490–1495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405776102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacquemin P, et al. Transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 regulates pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation and controls expression of the proendocrine gene ngn3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4445–4454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4445-4454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao N, et al. Dynamic regulation of Pdx1 enhancers by Foxa1 and Foxa2 is essential for pancreas development. Genes & Development. 2008;22:3435–3448. doi: 10.1101/gad.1752608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piper K, et al. Novel SOX9 expression during human pancreas development correlates to abnormalities in Campomelic dysplasia. Mech. Dev. 2002;116:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seymour PA, et al. SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:1865–1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krapp A, et al. The p48 DNA-binding subunit of transcription factor PTF1 is a new exocrine pancreas-specific basic helix-loop-helix protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:4317–4329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings RE, et al. Development of the human pancreas from foregut to endocrine commitment. Diabetes. 2013;62:3514–3522. doi: 10.2337/db12-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho CHH, et al. Inhibition of activin/nodal signalling is necessary for pancreatic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3284–3295. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2687-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie R, et al. Dynamic chromatin remodeling mediated by polycomb proteins orchestrates pancreatic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.023. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Bang AG. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. doi:10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borowiak M, Maehr R, Chen S, Chen AE, Tang W. Small molecules efficiently direct endodermal differentiation of mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.014. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez-Seguel E, et al. Mutually exclusive signaling signatures define the hepatic and pancreatic progenitor cell lineage divergence. Genes & Development. 2013;27:1932–1946. doi: 10.1101/gad.220244.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortijo C, Gouzi M, Tissir F, Grapin-Botton A. Planar cell polarity controls pancreatic beta cell differentiation and glucose homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1593–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rada-Iglesias A, Bajpai R, Swigut T, Brugmann SA. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09692. doi:10.1038/nature09692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquali L, et al. Pancreatic islet enhancer clusters enriched in type 2 diabetes risk-associated variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:136–143. doi: 10.1038/ng.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver-Krasinski JM, Stoffers DA. On the origin of the beta cell. Genes & Development. 2008;22:1998–2021. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao B, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes & Development. 2008;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George NM, Day CE, Boerner BP, Johnson RL, Sarvetnick NE. Hippo Signaling Regulates Pancreas Development through Inactivation of Yap. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:5116–5128. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01034-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu-Chittenden Y, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes & Development. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elghazi L, Cras-Méneur C, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Role for FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals in controlling pancreatic endocrine progenitor cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:3884–3889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062321799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynn FC, et al. Sox9 coordinates a transcriptional network in pancreatic progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:10500–10505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawada A, et al. Tead proteins activate the Foxa2 enhancer in the node in cooperation with a second factor. Development. 2005;132:4719–4729. doi: 10.1242/dev.02059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whyte WA, et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weedon MN, et al. Recessive mutations in a distal PTF1A enhancer cause isolated pancreatic agenesis. Nat Genet. 2014;46:61–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes & Development. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rooman I, Real FX. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and acinar cells: a matter of differentiation and development? Gut. 2012;61:449–458. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.235804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapoor A, et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic Kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2014;158:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, et al. Downstream of Mutant KRAS, the Transcription Regulator YAP Is Essential for Neoplastic Progression to Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Science signaling. 2014;7:ra42–ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. doi:10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bardeesy N, Stanger BZ. Hippo signaling regulates differentiation and maintenance in the exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1543–53. 1553.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes & Development. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujitani Y, et al. Targeted deletion of a cis-regulatory region reveals differential gene dosage requirements for Pdx1 in foregut organ differentiation and pancreas formation. Genes & Development. 2006;20:253–266. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gannon M, Gamer LW, Wright CV. Regulatory regions driving developmental and tissue-specific expression of the essential pancreatic gene pdx1. Dev. Biol. 2001;238:185–201. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO Summarizes and Visualizes Long Lists of Gene Ontology Terms. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Binot A-C, et al. Nkx6.1 and nkx6.2 regulate alpha- and beta-cell formation in zebrafish by acting on pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells. Dev. Biol. 2010;340:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

METHODS REFERENCES

- 48.O’Rahilly R, Müller F, Hutchins GM, Moore GW. Computer ranking of the sequence of appearance of 73 features of the brain and related structures in staged human embryos during the sixth week of development. Am. J. Anat. 1987;180:69–86. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maestro MA, et al. Hnf6 and Tcf2 (MODY5) are linked in a gene network operating in a precursor cell domain of the embryonic pancreas. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:3307–3314. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piper K, et al. Beta cell differentiation during early human pancreas development. J. Endocrinol. 2004;181:11–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petzold KM, Spagnoli FM. A system for ex vivo culturing of embryonic pancreas. J Vis Exp. 2012:e3979–e3979. doi: 10.3791/3979. doi:10.3791/3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaulton KJ, et al. A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat Genet. 2010;42:255–259. doi: 10.1038/ng.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luco RF, Maestro MA, Sadoni N, Zink D, Ferrer J. Targeted deficiency of the transcriptional activator Hnf1alpha alters subnuclear positioning of its genomic targets. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Arensbergen J, et al. Derepression of Polycomb targets during pancreatic organogenesis allows insulin-producing beta-cells to adopt a neural gene activity program. Genome Research. 2010;20:722–732. doi: 10.1101/gr.101709.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morán I, et al. Human β cell transcriptome analysis uncovers lncRNAs that are tissue-specific, dynamically regulated, and abnormally expressed in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2012;16:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature Protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Hoon MJL, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview—extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gupta S, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Bailey TL, Noble WS. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitlock MC. Combining probability from independent tests: the weighted Z-method is superior to Fisher’s approach. J. Evol. Biol. 2005;18:1368–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derrien T, et al. Fast Computation and Applications of Genome Mappability. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esni F, Miyamoto Y, Leach SD, Ghosh B. Primary explant cultures of adult and embryonic pancreas. Methods Mol. Med. 2005;103:259–271. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-780-7:259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skouloudaki K, et al. Scribble participates in Hippo signaling and is required for normal zebrafish pronephros development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:8579–8584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiang EF, et al. Two sox9 genes on duplicated zebrafish chromosomes: expression of similar transcription activators in distinct sites. Dev. Biol. 2001;231:149–163. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Argenton F, Zecchin E, Bortolussi M. Early appearance of pancreatic hormone-expressing cells in the zebrafish embryo. Mech. Dev. 1999;87:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jowett T, Lettice L. Whole-mount in situ hybridizations on zebrafish embryos using a mixture of digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labelled probes. Trends Genet. 1994;10:73–74. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bessa J, et al. Zebrafish enhancer detection (ZED) vector: A new tool to facilitate transgenesis and the functional analysis of cis-regulatory regions in zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics. 2009;238:2409–2417. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawakami K, Shima A, Kawakami N. Identification of a functional transposase of the Tol2 element, an Ac-like element from the Japanese medaka fish, and its transposition in the zebrafish germ lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:11403–11408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.