Abstract

The eye lens consists of layers of tightly packed fiber cells, forming a transparent and avascular organ that is important for focusing light onto the retina. A microcirculation system, facilitated by a network of gap junction channels composed of connexins 46 and 50 (Cx46 and Cx50), is hypothesized to maintain and nourish lens fiber cells. We measured lens impedance in mice lacking tropomodulin 1 (Tmod1, an actin pointed-end capping protein), CP49 (a lens-specific intermediate filament protein), or both Tmod1 and CP49. We were surprised to find that simultaneous loss of Tmod1 and CP49, which disrupts cytoskeletal networks in lens fiber cells, results in increased gap junction coupling resistance, hydrostatic pressure, and sodium concentration. Protein levels of Cx46 and Cx50 in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− double-knockout (DKO) lenses were unchanged, and electron microscopy revealed normal gap junctions. However, immunostaining and quantitative analysis of three-dimensional confocal images showed that Cx46 gap junction plaques are smaller and more dispersed in DKO differentiating fiber cells. The localization and sizes of Cx50 gap junction plaques in DKO fibers were unaffected, suggesting that Cx46 and Cx50 form homomeric channels. We also demonstrate that gap junction plaques rest in lacunae of the membrane-associated actin-spectrin network, suggesting that disruption of the actin-spectrin network in DKO fibers may interfere with gap junction plaque accretion into micrometer-sized domains or alter the stability of large plaques. This is the first work to reveal that normal gap junction plaque localization and size are associated with normal lens coupling conductance.

Keywords: beaded intermediate filament, CP49, impedance, membrane skeleton, tropomodulin 1

the eye lens, a transparent, avascular, and biconvex organ in the anterior chamber of the eye, is responsible for fine-focusing light onto the retina. The anterior hemisphere of the lens is covered by a monolayer of epithelial cells, while the bulk of the lens is made up of elongated fiber cells. Life-long lens growth depends on the proliferation, elongation, migration, and differentiation of equatorial epithelial cells (74). Newly differentiated hexagonal-shaped fiber cells are precisely overlaid onto previous generations of fiber cells (5, 49, 50). Lens fiber cell membranes contain specialized junctions and interdigitations that tightly pack apposing cells to ensure tissue integrity and minimize light scattering (7, 91).

Differentiating fiber cells also undergo a remarkable maturation process to eliminate all cellular organelles to prevent light scattering at the center of the lens. Inner mature fiber cells without organelles have little or no protein turnover and very low metabolism (4, 60). These fiber cells are connected by intercellular gap junction channels that are hypothesized to provide the outflow pathway for the lens microcirculatory system (65). Connexins are transmembrane protein subunits of gap junction channels, and six connexins oligomerize to form a connexon, or hemichannel (46, 48). Coupling of two connexons from neighboring cells can create a gap junction channel to allow diffusion of small molecules between the two connected cells (40). Changing the composition of connexons affects the permeability and electrophysiological properties of gap junctions. Connexons can contain just one type of connexin subunit (homomeric) or different types of connexin subunits (heteromeric) (48, 65). There are three types of gap junctions: 1) homotypic channels with two identical connexons composed of one type of connexin subunit, 2) heterotypic channels with homomeric connexons, each containing a different type of connexin, and 3) heterotypic channels with heteromeric connexons (48, 65). Lens gap junctions are composed of three types of connexins: connexin (Cx) 43 (Cx43 or α1) is present in lens epithelial cells (6); Cx46 (or α3) is expressed mainly in the fiber cells (38); and Cx50 (or α8) is present in epithelial and fiber cells (76). The Cx23 protein is also expressed in embryonic lens fiber cells (75), but it is unclear whether this connexin can form gap junctions (80).

The microcirculation model proposes that a current, carried primarily by sodium, enters the lens along extracellular spaces between cells at the anterior and posterior poles (12, 63, 85). The extracellular sodium ions flow toward the center of the lens and enter fiber cells by moving down the transmembrane electrochemical potential of sodium. Gap junctions allow the outflow of sodium to the surface at the lens equator (3). Na-K-ATPase is highly expressed in equatorial epithelial cells, facilitating the transport of sodium out of the lens (12, 30, 81). Along with the sodium ion current, there follows the circulation of fluid (11, 29, 63, 85) that delivers nutrients and removes waste from mature fiber cells (54–56, 67). Disruptions of the microcirculatory system due to the loss of gap junctions lead to nuclear cataracts caused by loss of homeostasis in mature fiber cells (28, 38, 87, 88). In addition, age-related nuclear cataracts may be due to decreased gap junction coupling, which leads to decreased microcirculation (31).

During lens fiber cell formation, cell length increases several hundredfold (51, 74, 82). This dramatic increase requires a strong network of cytoskeletal proteins to stabilize the long and thin fiber cells. Lens fibers contain two specialized intermediate filament proteins, CP49 (phakinin) and filensin (24). Together, these proteins form obligate heteropolymers, termed beaded intermediate filaments, that are required for mechanical strength (27, 36) and life-long transparency of the lens (1, 36, 73). Moreover, mutations in CP49 lead to autosomal-dominant cataracts in humans (15, 16, 44, 92). In addition, actin filaments that are cross-linked by α2β2-spectrin form a network that is tethered to the plasma membrane through spectrin interactions with ankyrin-B. The actin filament linkages in this network are stabilized by γ-tropomyosin and capped at their barbed and pointed ends by adducin and tropomodulin 1 (Tmod1), respectively (23, 52, 71, 89, 90). We previously showed that loss of Tmod1 destabilizes the actin-spectrin network and leads to local disorganization of lens fiber cells (36, 71, 72). Tmod1 is associated in a macromolecular complex with CP49 and filensin, as well as with actin and spectrin, suggesting that the actin-spectrin network and the beaded intermediate filaments are linked within lens fiber cells (36). It is not surprising that loss of Tmod1 and/or CP49 significantly impacts the mechanical strength of the lens (36).

In this study we investigated the effects of the loss of Tmod1 and/or CP49 on the microcirculatory system in mouse lenses. We were surprised to find that only the loss of both Tmod1 and CP49 causes an increase in gap junction coupling resistance, hydrostatic pressure, and sodium concentration in the lens. Further investigation revealed that Cx46, but not Cx50, gap junction plaques are significantly smaller and disrupted in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− [double-knockout (DKO)] lens fiber cells. We also found that the Cx46 and Cx50 gap junction plaques rest in lacunae of the actin-spectrin network in lens fiber cells. These data reveal an unexpected role for the actin-spectrin and beaded intermediate filament cytoskeleton networks in promoting assembly and/or stability of large Cx46 gap junction plaques, which are necessary for optimal lens microcirculation of ions, water, and other solutes.

METHODS

Ethical approval.

All animal procedures were performed according to recommendations in the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and protocols approved by The Scripps Research Institute and State University of New York at Stony Brook Animal Care and Use Committees.

Mice.

The generation of mixed-background FvBN/129SvEv/C57BL/6 Tmod1−/− mice is described elsewhere (35, 36, 66, 68, 71, 72). Embryonic lethality in Tmod1−/− mice (26) is rescued by a Tmod1-overexpressing transgene under the control of the cardiac-specific α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC) promoter (66). Tmod1 is expressed in the heart, but not other tissues, in Tmod1−/−(Tg-αMHC) mice. Tmod1 levels are normal in all tissues, except the heart, in Tmod1+/+(Tg-αMHC) mice. Mice were genotyped as previously described (66), and all mice used in this study carry the αMHC-Tmod1 transgene. For the sake of brevity, genotypes are referred to as Tmod1+/+ and Tmod1−/−.

Mixed-background Tmod1−/− mice have an endogenous mutation in the Bfsp2/CP49 gene, leading to a lack of beaded intermediate filament protein CP49 (36, 79). As previously described, we restored wild-type Bfsp2/CP49 alleles to Tmod1−/− mice by backcrossing the knockout mice to wild-type C57BL/6 mice (36). Genotyping for wild-type and mutant Bfsp2/CP49 alleles was conducted as previously described (79).

Lens gap junction coupling, intracellular hydrostatic pressure, and sodium concentration measurements.

Eyes were removed from euthanized 2-mo-old mice and placed in a Sylgard-lined petri dish filled with normal Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 137.7 NaCl, 2.3 NaOH, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). To isolate and mount lenses, the cornea and iris were removed, and the optic nerve was cut. The sclera was cut into four flaps from the posterior surface. Then the lens was transferred and pinned to the bottom of a chamber with a Sylgard base. The chamber was mounted on the stage of a microscope and perfused with normal Tyrode solution.

Gap junction coupling conductance was measured as previously described (31). Briefly, one microelectrode was placed in a central fiber cell into which a wide-band stochastic current was injected. The induced voltage was recorded by a second microelectrode that was placed in a peripheral fiber cell at a distance r (cm) from the center of a lens of radius a (cm). The impedance (induced voltage ÷ injected current) of the lens was recorded in real time using a fast Fourier analyzer (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA). At high frequencies, the magnitude of the impedance asymptotes to a series resistance (RS, Ω). On the basis of an equivalent circuit model (64), RS is the radial resistance of gap junctions between the point of recording and the surface of the lens. The value of RS was estimated from the magnitude of the impedance at 1,000 Hz. The voltage-recording microelectrode was advanced radially into the lens along its track, and the impedance was recorded at four to five depths in any one lens. RS values from eight lenses of each genotype were pooled and curve-fitted using Eq. 1

| (1) |

The effective intracellular resistivity of the peripheral differentiating fibers (RDF, Ω·cm) is generally lower than that of the more central mature fibers (RMF, Ω·cm). The change in value occurs abruptly at a location r = b, where b is ∼0.85a. At this location, organelles are degraded, and the COOH termini of the connexins are cleaved. The value of RS is related to the underlying effective resistivities by Eq. 1. The gap junction coupling conductance (G) per area of cell-to-cell contact (S/cm2) is given by Eq. 2

| (2) |

where w = 3 μm is the radial spacing between gap junction plaques. The effective resistivity of the intracellular compartment of the lens is a tensor, which, in spherical coordinates, has different values in the r, θ, and φ directions. In the r direction, current flows from cell to cell through gap junctions on the broad sides of the fibers. In the θ direction, current flows along the axes of the fiber cells. In the φ direction, current flows from cell to cell through gap junctions on the short sides of the fibers. The experimental protocol and model described here give the radial (r) component of gap junction coupling.

The method used to measure intracellular pressure is described elsewhere (29). Briefly, the resistance (1.5–2 MΩ) of a microelectrode filled with 3 M KCl was continuously measured. When the microelectrode was inserted into the lens, the positive intracellular pressure forced cytoplasm into the tip and caused the resistance to increase. A manometer was used to generate and measure pressure that was applied to the interior of the microelectrode. When the applied pressure was just equal to the intracellular pressure, the cytoplasm was forced out of the tip, and the resistance was restored to the value first recorded in the bathing solution. The microelectrode was advanced into the lens along its track, and the pressures were recorded at four to five depths in any one lens. Data from eight lenses for each genotype were pooled, and the average pressure gradient was estimated by curve-fitting a quadratic model (29) to the pooled data.

The intracellular concentration of sodium was measured by intracellular injection of the sodium-sensitive ratiometric dye sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate followed by excitation of fluorescence emission using a dual-wavelength spectrometer system as previously described (87). Sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate (0.2 mM) was dissolved in the microelectrode solution and injected into fiber cells at four to five radial locations in any one lens. Data from eight lenses for each genotype were pooled and curve-fitted with a quadratic model (87) to estimate the average radial gradient in intracellular sodium concentration.

Western blotting for Cx46 and Cx50.

Fresh lenses from 1-mo-old mice were collected, and one lens from each mouse was used to make protein samples. Four control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and five Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− mice were used for these experiments. Lens protein samples were prepared as previously described (36). Briefly, lenses were vigorously vortexed in 100 μl of SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Solubilized lens proteins were transferred to a new tube, and proteins were separated on 4–20% linear gradient SDS-PAGE minigels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in transfer buffer with 20% methanol as previously described (34). The nitrocellulose blots were incubated in PBS for 1 h at 65°C, blocked with 4% BSA in PBS for 4 h at room temperature and then overnight at 4°C, and subsequently incubated in primary antibodies to Cx46 or Cx50 for 3 h at room temperature with gentle rocking. Antibody labeling and blot washing solutions are described elsewhere (25). The rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies were as follows: anti-Cx46 connexin (α3J, intracellular loop, 1:1,500 dilution) antibody (a generous gift from Dr. Xiaohua Gong, University of California, Berkeley) (37), anti-Cx50 (COOH-terminal, 1:3,000 dilution) antibody (a generous gift from Dr. Jose M. Wolosin, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine) (14), and anti-Tmod1 (COOH-terminal peptide, 1:5,000 dilution) (36). The mouse monoclonal primary antibody anti-GAPDH (1:5,000 dilution) was obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) and goat anti-mouse HRP (1:10,000 dilution; Promega, Madison, WI) antibodies were used for secondary detection, visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence on X-ray film. Bands on blots were quantified using ImageJ, with normalization to GAPDH. Average, standard deviation, and statistical significance were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Immunostaining.

Freshly enucleated eyes were collected from 6-wk-old mice. Fixation was facilitated by a small slit at the corneal-scleral junction. Eyeballs were fixed overnight in 1% paraformaldehyde at 4°C, washed in PBS, cryoprotected in sucrose, frozen in OCT medium (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and stored at −80°C until they were sectioned. Frozen 12-μm-thick sections were collected with a Leica CM1950 cryostat and then permeabilized, blocked, and stained as previously described (71, 72) using rabbit anti-Cx46 (1:200 dilution) or rabbit anti-Cx50 (1:100 dilution) with mouse monoclonal anti-β2-spectrin (42/B, 1:100 dilution; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Secondary antibodies were Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:100 dilution; Life Technologies) and Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100 dilution; Life Technologies). Rhodamine-phalloidin (1:100 dilution; Life Technologies) was used to stain F-actin, and Hoechst 33258 (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used to stain nuclei. Slides were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies), and Z-stacks were collected at 0.2-μm steps using a confocal microscope (model LSM780, Zeiss). Sections with cross-sectionally oriented fiber cells at the lens equator were identified on the basis of thickness of the lens epithelium (71). Images of differentiating cortical fiber cells were collected 50–100 μm from the epithelial cells. Staining was repeated on four samples from different mice for each genotype, and representative data are shown.

Image analysis.

Z-stack confocal images were analyzed using Volocity 6.3. For gap junction plaque quantification, we selected regions of interest (16 μm × 16 μm × 5 μm volumes) from Z-stacks of immunostained equatorial frozen cross sections at a depth ∼60–80 μm inward from the epithelial cells. The fine filter was used for noise reduction, which was applied to all Z-stacks in all channels. Three-dimensional reconstructions of gap junction plaques with F-actin or β2-spectrin were created using the 3D Opacity rendering algorithm. We used the “Find Objects” algorithm in Volocity to determine the total number, average volume, and total volume of gap junction plaques in Z-stacks from cross-sectionally oriented frozen sections. The threshold was set to a value between −20 and 0 to eliminate nonspecific signals, and <0.2-μm3 plaques were excluded from the analysis, because these very small plaques were almost exclusively observed on the short sides of differentiating lens fiber cells and were not part of the large plaques that occupy the center of the broad sides of differentiating fiber cells. We evaluated Z-stacks from four Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and four Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− mice (2 Z-stacks from each mouse). The average, standard error, and statistical significance were calculated and plotted in Excel. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test, and P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Colocalization maps and Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC) in colocalized volumes were generated and calculated in Imaris 64 software.

Freeze-fracture electron microscopy and immunogold labeling on replicas.

Protocols are described elsewhere (8). Briefly, freshly isolated eyes from 2-mo-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− mice were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) at room temperature for 2–4 h or overnight. Lenses were oriented to obtain sagittal (longitudinal) sections with a vibratome, and slices were collected, marked serially from superficial to deep, and kept separately. The slices were then cryoprotected with 25% glycerol in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at room temperature for 1 h and cryofractured in a modified Balzers 400 T freeze-fracture unit at a stage temperature of −135°C in a vacuum of ∼2 × 10−7 Torr. The replicas, obtained by unidirectional shadowing, were cleaned with household bleach and examined with a transmission electron microscope (model 1200EX, JEOL).

For freeze-fracture replica immunogold labeling, freshly isolated lenses from 2-mo-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− mice were lightly fixed in 0.75% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and then cut into 300-μm slices with a vibratome to make freeze-fracture replicas as described above. One drop of 0.5% parloidion in amyl acetate was used to secure the integrity of the whole piece of a large replica during cleaning and immunogold labeling. The replica was digested with 2.5% SDS, 10 mM Tris·HCl, and 30 mM sucrose, pH 8.3 (SDS buffer), at 50°C until all visible attached tissue debris was removed from the replica. The replica was then rinsed with PBS, blocked with 4% BSA-0.5% teleostean gelatin in PBS for 30 min, and incubated with 1) affinity-purified goat Cx46 COOH-terminal polyclonal antibody (1:10 dilution, M-19; catalog no. SC-20861, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or 2) affinity-purified goat Cx50 polyclonal antibody (1:10 dilution, K-20; catalog no. SC-20876, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. The replica was washed with PBS and incubated with 10 nM Protein A Gold (EY Laboratories, San Mateo, CA) at 1:50 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. The replica was rinsed, fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min, rinsed in water, collected on a 200-mesh Gilder finder grid, rinsed with 100% amyl acetate for 30 s to remove parloidion, and viewed with a transmission electron microscope (model 1200EX, JEOL).

RESULTS

Simultaneous loss of Tmod1 and CP49 results in increased gap junction coupling resistance, intracellular hydrostatic pressure, and sodium concentration in the lens.

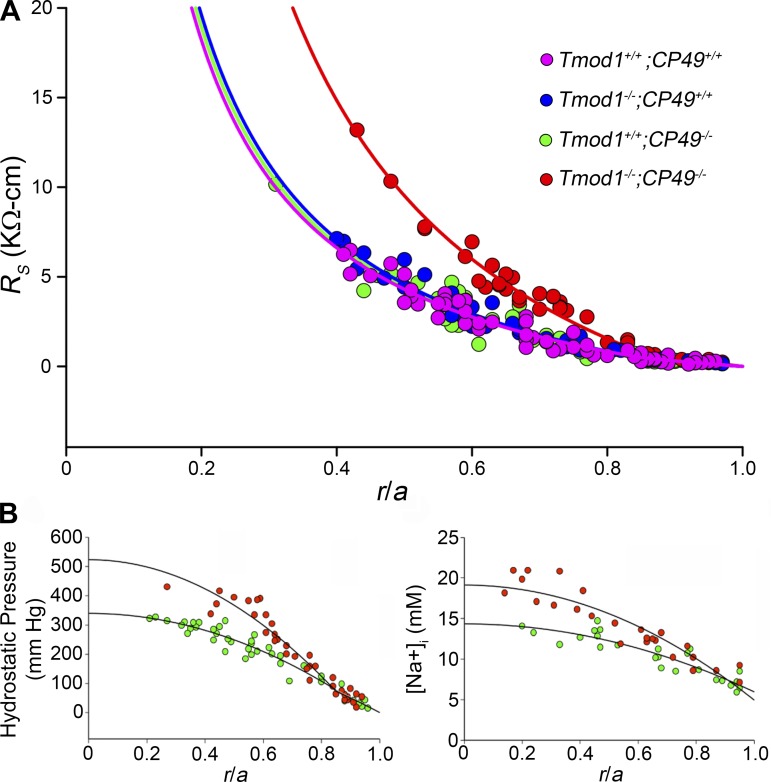

We previously demonstrated that loss of Tmod1 and CP49 causes patches of disorganized and misaligned fiber cells in the outer cortex of the lens and a decrease in lens stiffness (36, 71). Thus, to understand whether loss of Tmod1 and/or CP49 affects other lens functional properties, we measured gap junction coupling conductances in lenses with and without Tmod1 and/or CP49. We found similar values of RS and coupling conductances (Fig. 1A, Table 1) in wild-type (Tmod1+/+;CP49+/+) and single-knockout (Tmod1−/−;CP49+/+ or Tmod1+/+;CP49−/−) lenses. The coupling conductance of differentiating fibers (Table 1) is generally 0.8–1 S/cm2 of cell-cell contact and is based on the best-fit curve (Eqs. 1 and 2) to RS data collected from eight lenses of the same genotype. The differences between wild-type and single-knockout lenses in this region fall within this normal range and may be due to measurement uncertainty or biological variability in connexin expression. By contrast, loss of both Tmod1 and CP49 (Tmod1−/−;CP49−/−) resulted in significantly increased RS due to a nearly twofold decrease in radial coupling conductance for differentiating and mature fibers (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Since there is no detectable difference in the RS or the underlying coupling conductance between wild-type and Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lenses, we used Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− mice as littermate controls for DKO mice in the rest of our studies.

Fig. 1.

Resistance, hydrostatic pressure, and sodium concentration in 2-mo-old lenses. A: series resistance (RS) in Tmod1+/+;CP49+/+ (magenta, n = 8), Tmod1−/−;CP49+/+ (blue, n = 8), Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− (green, n = 8), and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− (red, n = 8) lenses as a function of distance from lens center (r/a), where r (cm) is actual distance and a (cm) is lens radius. There is an obvious increase in resistance in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses. B: intracellular hydrostatic pressure and sodium concentration ([Na+]) in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses (n = 8 for each genotype in each study) as a function of normalized distance from lens center (r/a). Hydrostatic pressure and sodium concentration are increased in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− compared with control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lenses.

Table 1.

Regional values of resistivity and normalized coupling conductance of four types of lenses in differentiating and mature fibers

| Genotype | Zone | Ri, KΩ·cm | Gi, S/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tmod1+/+;CP49+/+ | DF | 4.14 | 0.80 |

| Tmod1−/−;CP49+/+ | DF | 3.95 | 0.84 |

| Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− | DF | 3.42 | 0.97 |

| Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− | DF | 6.34 | 0.53 |

| Tmod1+/+;CP49+/+ | MF | 6.86 | 0.49 |

| Tmod1−/−;CP49+/+ | MF | 7.16 | 0.47 |

| Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− | MF | 6.99 | 0.48 |

| Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− | MF | 15.36 | 0.22 |

Ri, resistivity; Gi, conductance; DF, differentiating fibers; MF, mature fibers.

The lens microcirculation is driven by movement of sodium ions between the center and the surface of the lens (63). For the intracellular leg of the circulation, sodium moves from the central fiber cells to the surface cells through gap junction channels. This flux is associated with a sodium diffusion gradient, a voltage gradient, and water flow. The water flow is associated with an intracellular hydrostatic pressure gradient. If the circulation remains intact but gap junction coupling is reduced, the intracellular sodium diffusion gradient and the intracellular hydrostatic pressure gradient are predicted to increase. Thus we determined the hydrostatic pressure and sodium concentration in lenses from Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO mice. As expected, the gradients for hydrostatic pressure (Fig. 1B) and sodium concentration (Fig. 1C) increased in lenses from DKO mice. These data suggest that the outflow of sodium ions, water, and, presumably, other solutes and waste was maintained in lenses in which the actin-spectrin network is disrupted and the beaded intermediate filament network in fiber cells is lost. However, to maintain the circulation, intracellular homeostasis was compromised.

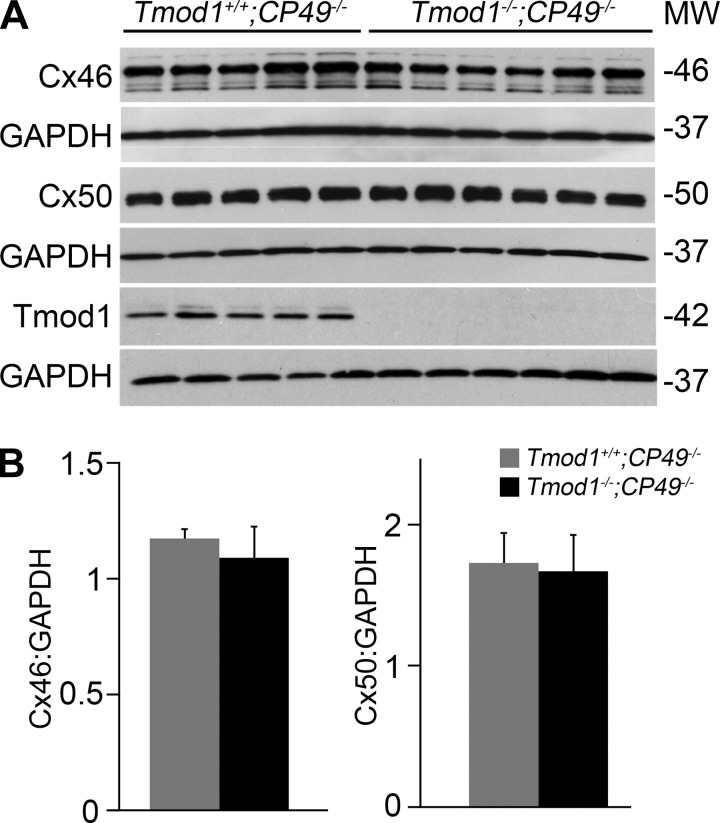

Levels of connexin proteins are unchanged in lenses from DKO mice.

Previous studies showed that reduced levels of connexins and loss of gap junctions can lead to increased resistance and decreased conductance in mouse lenses (2, 37). Therefore, we performed Western blotting of total lens proteins from Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO mice to determine whether there were any changes in the levels of Cx46 and Cx50 in lenses from DKO mice. We were surprised to find no obvious difference in the level of connexin proteins between DKO and Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lenses (Fig. 2A). In DKO lens protein samples, we also did not detect abnormal connexin degradation or cleavage products. Quantification of Western band intensities normalized to GAPDH showed no change in Cx46 and Cx50 levels between Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO lenses (Fig. 2B). Since there was no change in the total level of connexin proteins in DKO lenses, we next determined whether there was a change in the subcellular localization of gap junction plaques in lens fiber cells.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of connexin (Cx) 46 and Cx50 in 1-mo-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses. A: Western blots of Cx46, Cx50, tropomodulin 1 (Tmod1), and GAPDH protein levels in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− (control) and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− [double-knockout (DKO)] lenses. Each lane represents an individual lens from a different mouse. Levels of Cx46 and Cx50 appear similar between control and DKO lenses. B: quantification of Western band intensities for Cx46 and Cx50 normalized to those for GAPDH shows no statistically significant difference between control (gray bars) and DKO (black bars) lenses.

Cx46 gap junction plaques are smaller and disrupted in DKO differentiating lens fiber cells.

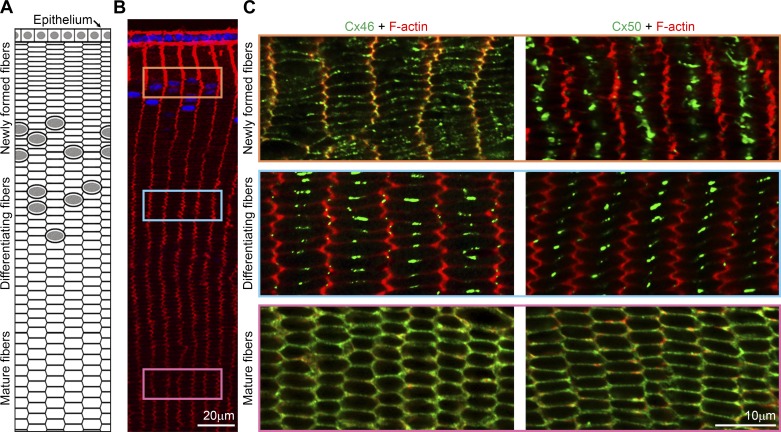

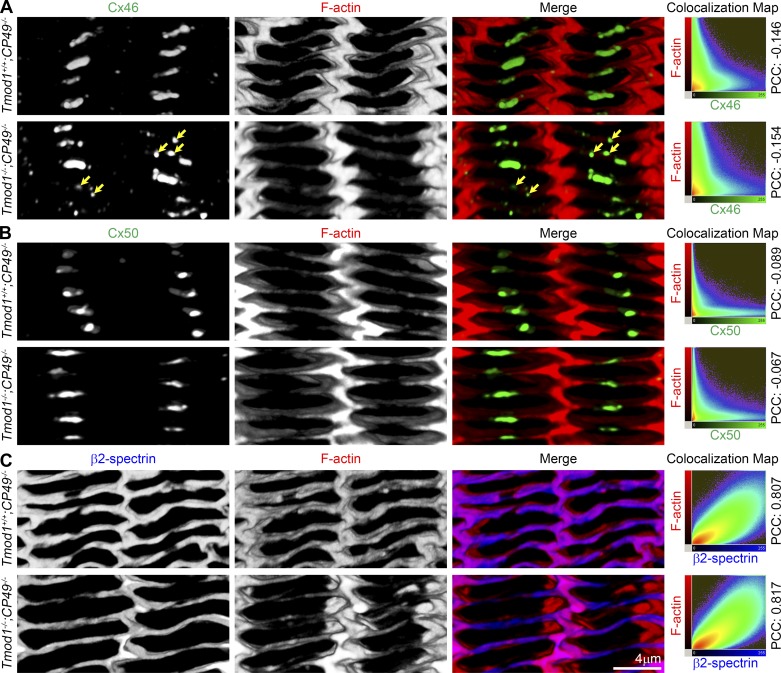

Cx46 and Cx50 form large, micrometer-sized gap junction plaques in the middle of the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells in a region ∼60–100 μm inward from the lens epithelium, with smaller plaques forming on the narrow sides (38, 43, 76). To determine whether Cx46 or Cx50 organization was altered in the DKO lens fiber cells, we examined Cx46 or Cx50 localization with respect to F-actin in equatorial sections of Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO lenses 60–80 μm from the lens epithelium in differentiating lens fibers where large gap junction plaques had formed (Fig. 3). We did not observe an obvious difference in Cx46 or Cx50 gap junction plaques in newly formed and mature fiber cells between control and DKO lenses (data not shown). In fiber cell cross sections at the lens equator, F-actin localizes to the broad and narrow sides of hexagonal lens fiber cells, with increased signal on the narrow sides and at vertices (Fig. 4). Cx46 is highly concentrated in large micrometer-sized gap junction plaques in the middle of the broad sides of control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− differentiating fiber cells located 60–80 μm from the lens epithelium (Fig. 4A), similar to previous studies in wild-type mouse lenses (38). In contrast, in DKO differentiating lens fibers, Cx46 gap junction plaques were dispersed and noticeably smaller (Fig. 4A, yellow arrows). No increase in Cx46 signal was observed in the DKO lens fiber cell cytoplasm, indicating that Cx46 was targeted to fiber cell membranes (Fig. 4A). In the same region of differentiating lens fibers, Cx50 plaques were also highly concentrated on the broad sides of these cells, but these plaques in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lens sections appeared similar to those in DKO lens sections (Fig. 4B). This staining pattern was comparable with previous data in lenses from wild-type mice (38, 76). Colocalization heat maps and corresponding PCC values showed little colocalization between connexin and F-actin staining signals (PCC = −0.067 to −0.154; Fig. 4, A and B) in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− or DKO lens fibers. For comparison, F-actin and β2-spectrin staining signals were highly colocalized in these cells, with PCC = 0.807–0.817 (perfect colocalization would be PCC = 1.00; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining confocal (2-dimensional) images (single optical plane) for Cx46 or Cx50 with F-actin in fiber cells at various depths visualized in cross-sectional orientation in frozen sections from 6-wk-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lenses. Cartoon (A, not drawn to scale) and boxed regions in low-magnification image of F-actin (red) and Hoechst (blue) staining (B) of lens cells in an equatorial section indicate approximate location where higher-magnification images for Cx46 and Cx50 staining (C) were obtained. Colabeling of Cx46 (green) and F-actin (red) reveals punctate Cx46 staining around the entire membrane in newly formed fiber cells, while large Cx46 gap junction plaques are localized near the center of the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells. In contrast, Cx50 staining signals were mostly localized to the center of the broad sides of newly formed fiber cells and concentrated into large plaques at the center of the broad sides of differentiating fiber cells. Cx46 and Cx50 staining signals were uniformly distributed around the entire membrane of mature fiber cells. Similar staining patterns were observed for Cx46 and Cx50 in newly formed and mature fiber cells of Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of immunostaining for Cx46, Cx50, or β2-spectrin with F-actin in fiber cells with cross-sectional orientation in frozen sections from 6-wk-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses. A: colabeling of Cx46 (green) and F-actin (red) reveals large Cx46 gap junction plaques localized near the center of the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells in the Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− sample. However, Cx46 plaques appeared smaller and disrupted in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fiber cells (yellow arrows). Colocalization maps and negative Pearson's coefficient (PCC) in the colocalized volume show little or no colocalization between Cx46 and F-actin staining signals in control or DKO lens fiber cells. B: colabeling of Cx50 (green) and F-actin (red) shows large Cx50 gap junction plaques at the center of the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− sections. There is no obvious difference in localization and size of Cx50 gap junction plaques between control and DKO lenses. Colocalization map and negative PCC value demonstrate little or no colocalization between Cx50 and F-actin. C: colabeling of β2-spectrin (blue) and F-actin (red) shows strong colocalization and high PCC value in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers.

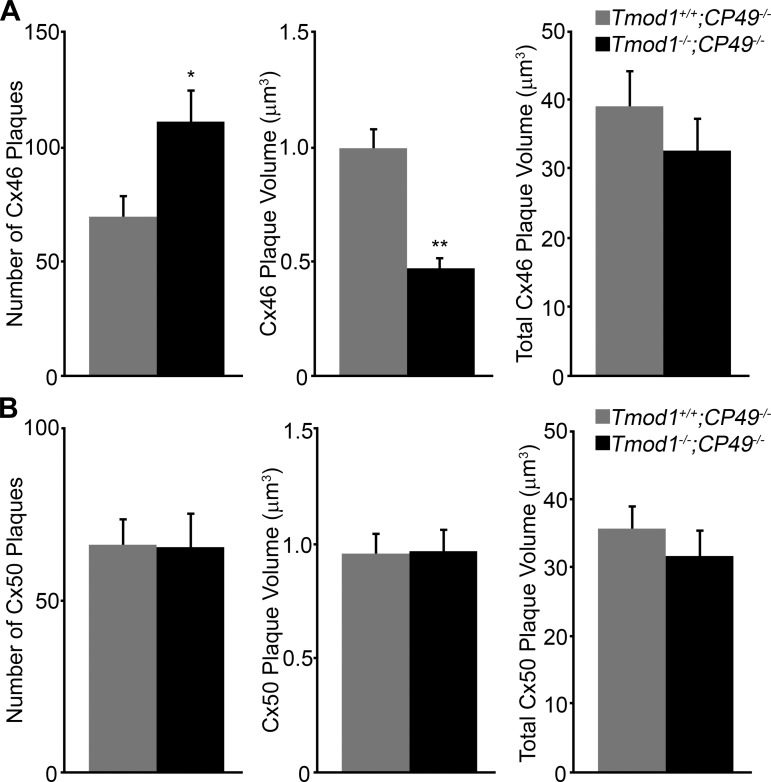

We quantified the number of gap junction plaques, average gap junction plaque volume, and total gap junction plaque volume in confocal Z-stacks from the immunostained lens sections within a defined region of interest. This analysis revealed a statistically significant increase in the total number of Cx46 gap junction plaques in lens fibers from DKO compared with Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− control mice (Fig. 5A, left). Consistent with our qualitative observation of smaller plaques in DKO lens fibers in Fig. 4A, we also found a significant decrease in the average Cx46 plaque volume in DKO cells (Fig. 5A, middle). Importantly, the overall total Cx46 gap junction plaque volume was unchanged between Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO lens fibers (Fig. 5A, right), consistent with the Western blot data showing that Cx46 levels remained constant. Distinct from Cx46 plaques, the number of Cx50 plaques, average Cx50 plaque volume, and total Cx50 plaque volumes were similar between Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO differentiating lens fibers. These data indicate that Cx46 gap junctions do not form large plaques on the broad side of fiber cells when both the actin-spectrin and beaded intermediate filament networks are disrupted, and smaller and dispersed Cx46 gap junction plaques are correlated specifically with decreased radial coupling conductance in differentiating fibers of DKO lenses.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of total number of gap junction plaques, average plaque volume, and total plaque value for Cx46 and Cx50 staining in differentiating lens fibers of 6-wk-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− (gray bars) and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− (black bars) mice. Immunostaining data collected from 4 different animals of each genotype (2 Z-stacks for each sample) were analyzed quantitatively. A: there is a statistically significant increase in number of Cx46 plaques in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers compared with control. Average Cx46 plaque volume is decreased in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fiber cells. Total Cx46 plaque volume is unchanged in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− vs. Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.00001. B: there is no statistically significant difference in total number of gap junction plaques, average plaque volume, and total plaque volume for Cx50 between Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers.

Gap junction plaques are localized in lacunae of the actin-spectrin network.

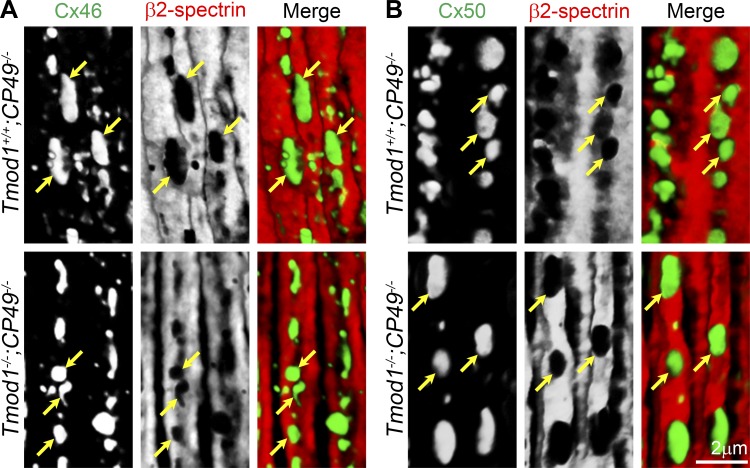

Our previous work demonstrated that the actin-spectrin network appeared to be disrupted in differentiating DKO lens fibers (36). To investigate a possible relationship between actin-spectrin network organization and Cx46 and Cx50 plaque formation, we next conducted double immunolabeling of Cx46 or Cx50 and β2-spectrin in lens sections in the anterior-posterior (AP) orientation. The AP orientation was chosen to best visualize the connexins and the actin-spectrin network along the broad sides of elongating fiber cells. In control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO lens sections, we found that Cx46 and Cx50 plaques were localized in regions of the cell membrane that were not associated with β2-spectrin (Fig. 6, yellow arrows). There was a clear segregation of immunostaining signals for β2-spectrin from those for Cx46 and Cx50 in control and DKO differentiating lens fibers. This same segregation of β2-spectrin, as well as F-actin, from the Cx46 or Cx50 staining was also observed in lenses from wild-type mice (data not shown). Consistent with the results from quantification of plaque volumes in Fig. 5, Cx46 plaques tended to be qualitatively smaller in the DKO fiber cells than the control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− fiber cells, while the Cx50 plaques were not.

Fig. 6.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of immunostaining for Cx46 or Cx50 with β2-spectrin in fiber cells with anterior-posterior orientation (en face view of membranes) in frozen sections from 6-wk-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses. A: colabeling of Cx46 (green) and β2-spectrin (red) shows that Cx46 gap junction plaques occupy lacunae in the actin-spectrin network on the broad sides of fiber cells (yellow arrows) in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− sections. B: Cx50 (green) gap junction plaques also rest in holes of the β2-spectrin (red) staining in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers.

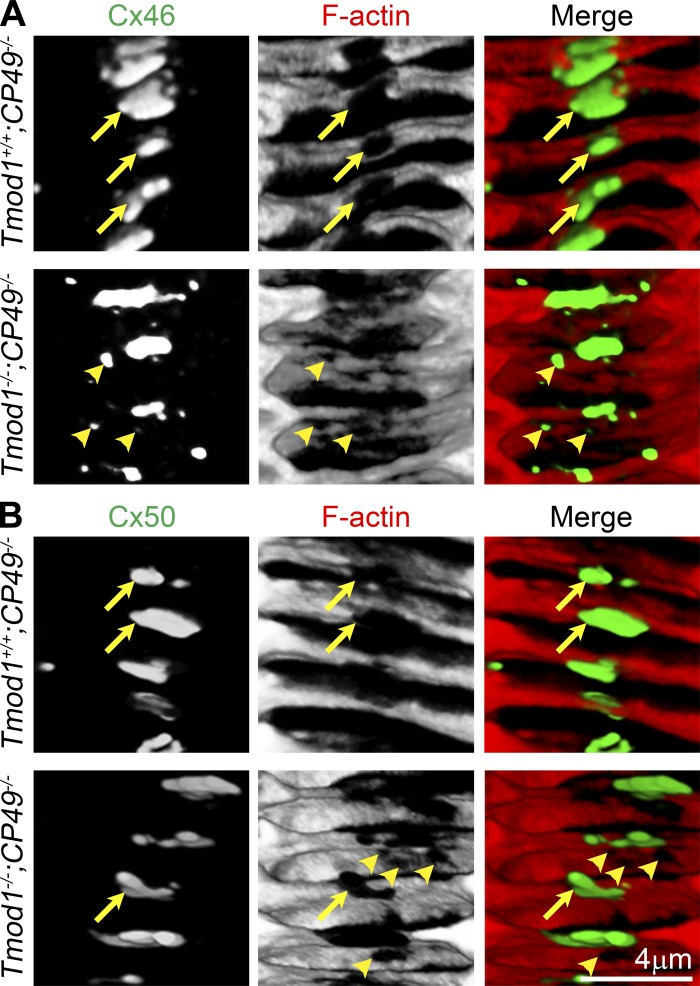

We previously reported an abnormal “moth-eaten” appearance of the actin-spectrin network in DKO lens fibers visualized in the cross-sectional orientation (36, 71), which is not evident in the en face views of fiber cell membranes in the AP orientation (Fig. 6). Thus we further examined the F-actin and connexin staining in cross-sectionally oriented lens sections that were slightly tilted for the best view of the fiber cell membranes on the broad sides (Fig. 7). In this view, we found large Cx46 and Cx50 gap junction plaques in the large lacunae of the F-actin staining in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lens fibers (Fig. 7, A and B, yellow arrows). In the DKO lens fibers, the small Cx46 gap junction plaques occupy small holes in the abnormal F-actin network (Fig. 7A, yellow arrowheads). Some small, empty holes in the F-actin staining are also apparent in the DKO lens fibers that are stained for Cx50 (Fig. 7B, yellow arrowheads). These apparently empty holes most likely contain the abnormal small Cx46 plaques observed in the DKO lens fibers (Fig. 7A). These results suggest that gap junction plaques form in lacunae of the actin-spectrin network and that the abnormal holes observed in the cytoskeletal network of DKO differentiating lens fibers might be a result of dispersed and smaller Cx46 gap junction plaques. The actin-spectrin network, together with the beaded intermediate filaments, may play a role in the regulation of gap junction plaque size at the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells.

Fig. 7.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of immunostaining for Cx46 and Cx50 with F-actin in fiber cells with cross-sectional orientation (tilted for visualization of the broad sides en face) in frozen sections from 6-wk-old Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lenses. A: colabeling of Cx46 (green) and F-actin (red) shows large Cx46 gap junction plaques localized in lacunae of the F-actin staining on the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− sample (yellow arrows). F-actin network appears disrupted in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− differentiating fiber cells, and small Cx46 plaques occupy the small holes in the F-actin staining (yellow arrowheads). B: colabeling of Cx50 (green) and F-actin (red) shows large Cx50 gap junction plaques in lacunae of the F-actin network in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− sections (yellow arrows). We observe many empty small holes in the F-actin staining (yellow arrowheads) in DKO lens fibers, which may be filled by Cx46, as shown in A.

Normal gap junctions are present in DKO lenses.

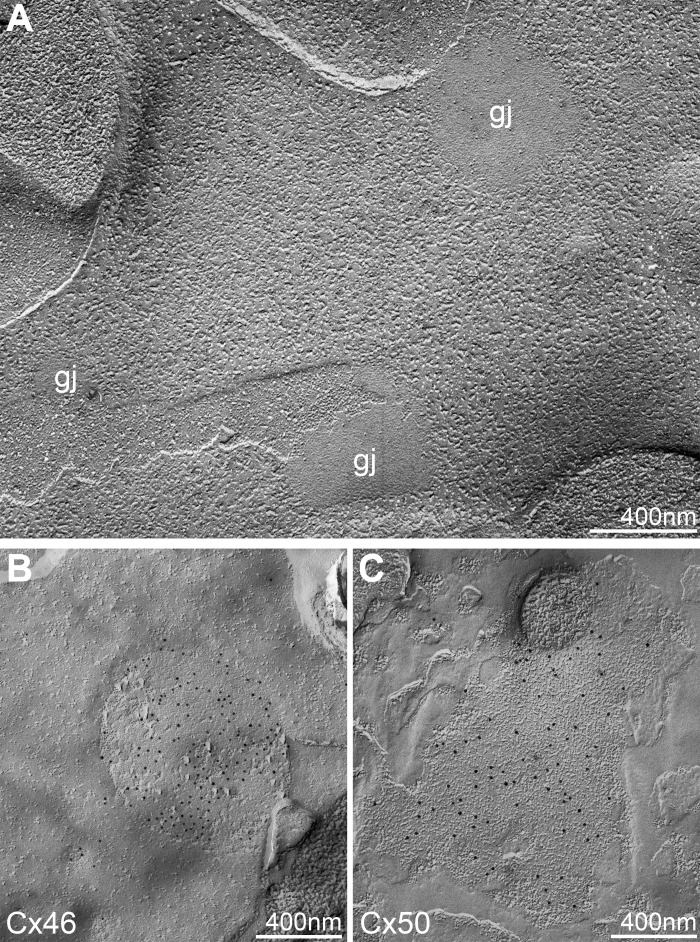

Since the size and distribution of Cx46 gap junction plaques in DKO lens fibers were disrupted, we considered the possibility that Cx46 may not form normal gap junctions in DKO lens fibers. Thus we used freeze-fracture electron microscopy to examine gap junction plaques on the broad sides of control Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− and DKO differentiating lens fibers located at approximately the same distance from the lens capsule at the equator of the lens (Fig. 8). We found morphologically normal gap junction plaques in DKO lens fibers (Fig. 8A), and immunogold labeling showed that Cx46 and Cx50 were present in gap junctions in DKO lens fibers (Fig. 8, B and C), indicating that Cx46 and Cx50 can assemble into morphologically normal plaques. These freeze-fracture data suggest that gap junction plaques likely remain functional in DKO lens fibers and that changes in sizes of Cx46 gap junction plaques on fiber cell broad sides, rather than inhibition of junction formation per se, in differentiating DKO lens fibers may be responsible for increased impedance.

Fig. 8.

Freeze-fracture transmission electron microscopy and immunogold labeling for Cx46 and Cx50 in gap junction plaques in differentiating fiber cells of 2-mo-old Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− mice. A: freeze-fracture transmission electron microscopy reveals morphologically normal gap junction plaques (gj) in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers. B and C: immunogold labeling for Cx46 and Cx50 shows both connexins in gap junction plaques in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fibers.

DISCUSSION

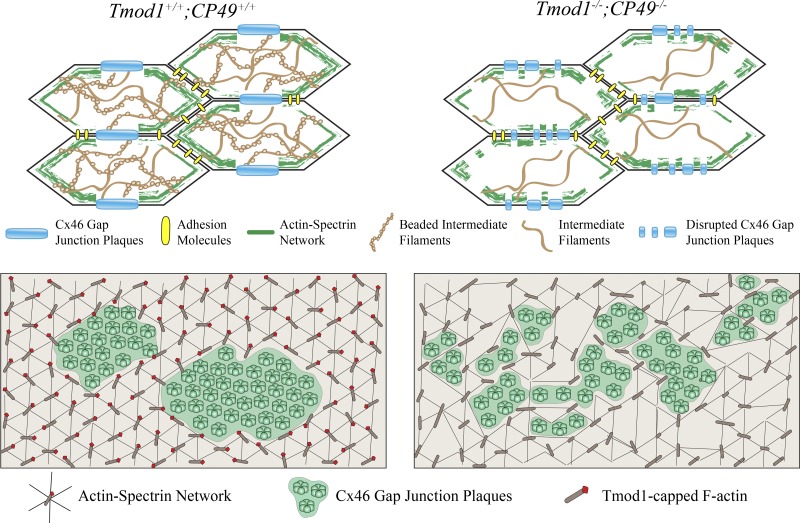

Our work shows that disruption of the actin-spectrin network, due to the loss of Tmod1, together with disruption of beaded intermediate filaments, caused by the absence of CP49, leads to decreased radial gap junction coupling conductance in mouse lenses. However, the loss of either Tmod1 or CP49 alone has no effect on the lens microcirculation system. The decrease in radial gap junction coupling conductance in DKO lenses is accompanied by an increase in the radial gradients for hydrostatic pressure and sodium concentration. Since there was no detectable decrease in the total number of gap junction channels, our data suggest that placement of the channels on broad faces of fiber cells was impaired, thus reducing radial coupling and increasing the forces needed to drive radial flows. The Cx46 gap junction plaques located on the broad sides of fiber cells in differentiating DKO lens fibers are smaller and more scattered, suggesting that radial flows are optimized by placement of large Cx46 gap junction plaques at the center of the broad sides of each fiber cell. While the formation of large Cx46 plaque domains on the broad sides of fiber cells depends on the two cytoskeletal networks, the assembly of Cx50 into large gap junction plaques is unaffected. We hypothesize that the actin-spectrin and intermediate filament networks may act as a fence or barrier to stabilize the large micrometer-sized Cx46 plaques once they are formed or may facilitate accretion of smaller patches of Cx46 gap junction plaques into larger plaques during assembly (Fig. 9). Our work suggests that collection of gap junction plaques into large membrane domains is critical for the normal function of the outflow pathway of the lens microcirculatory system.

Fig. 9.

Model for gap junction plaque accretion within the actin-spectrin network. In Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− lens fiber cells, actin-spectrin network is disrupted and the beaded intermediate filaments are lost. These changes coincide with smaller and altered Cx46 gap junction plaques. We hypothesize that the actin-spectrin network forms a fence to corral gap junction plaques to allow formation of large gap junction plaques at the center of the broad sides of differentiating lens fiber cells. Disruption of the actin-spectrin network in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− fiber cells may impair lateral assembly and/or stability of large Cx46 gap junction plaques during fiber cell differentiation.

Previous studies showed that the levels of connexin proteins affect lens conductance. A ∼25% decrease in conductance in heterozygous Cx46+/− and Cx50+/− differentiating lens fiber cells compared with wild-type cells has been reported (65). In Cx46−/− lenses, the conductance in differentiating fiber cells is about one-third of that in wild-type cells, and there is a total loss of conductance in the lens nucleus (37). In contrast, deletion of Cx50 leads to mild decreases in the conductance of differentiating fiber cells and no change in the conductance of inner mature fibers (2). Additionally, genetic replacement of Cx50 with Cx46 rescues the conductance in knockin mouse lenses (62). These data indicate that Cx46 channels are responsible for connecting mature fiber cells, while channels made of Cx46 and Cx50 share the responsibility of coupling differentiating fibers. Interestingly, deletion of Lim2, an integral lens membrane protein, leads to a decrease in lens coupling conductance, which is linked to a decrease in Cx46 protein level in the lens core (78). Similarly, the absence of glutathione peroxidase-1, an enzyme that protects against oxidative stress in the lens, also causes a 50% decrease in Cx46 and Cx50 protein levels and disruption in fiber cell coupling (87). Aberrant expression of Cx43 in fiber cells of PKCγ−/− lenses results in increased coupling conductance (17). From these previous studies, we can conclude that the level of connexin proteins, especially Cx46, in the lens can have a dramatic impact on lens fiber cell-cell coupling conductance. Distinct from this notion that the amount of protein dictates connectivity of lens cells, our current study indicates that the formation and/or stability of large gap junction plaques, mediated by cytoskeletal proteins, is also important for coupling of lens fibers. This is the first evidence that gap junction plaque size and distribution affect intercellular coupling.

Gap junction coupling conductance in differentiating fibers of rat and mouse lenses has been demonstrated to be maximal at the equator and to approach zero at either pole (3, 64, 65). This variation in conductance is likely the result of the anisotropy of gap junction plaque localization to the broad sides of differentiating lens fibers (3). Furthermore, the lens microcirculation model suggests that current can enter either pole through intercellular spaces without crossing from fiber to fiber, while current can only exit the lens by crossing from fiber to fiber (64), presumably relying on the outflow of solutes and water through large gap junction plaques in differentiating fibers. Decreased conductance in Tmod1−/−;CP49−/− differentiating lens fibers associated with changes in Cx46 gap junction plaque size and distribution supports the notion that large gap junction plaques on the broad side of differentiating lens fibers are important for high cell-cell coupling conductance to facilitate the microcirculation pathway.

The lens microcirculation model suggests that the outflow of ions, solutes, and water from the equator is driven mainly by the relatively high gap junction coupling conductance of differentiating fiber cells that directs intracellular flow toward the equatorial epithelial cells (65). Gap junctions composed of Cx46 and/or Cx50 contribute to intercellular coupling in differentiating lens fibers, while only Cx46 channels are functional in mature fibers (2, 19, 21, 37, 65). In DKO lenses, we observed a ∼50% decrease in conductance in DKO lens fibers compared with the control. The immunostaining data suggest that decreased conductance in differentiating DKO fibers is linked mostly to disruption of the large domains of Cx46 gap junction plaques at the membrane. It is possible that disrupted Cx46 gap junction plaques in differentiating DKO lens fibers result in fewer open channels localized to the broad sides of these cells, leading to changes in conductance. In inner mature fiber cells, however, we observe that Cx46 immunostaining signals are evenly distributed around the entire cell membrane in DKO mature fibers (data not shown), similar to control fiber cells (Fig. 3). We hypothesize that while the number of channels on the cell membrane is the same in DKO and control mature lens fibers, fewer gap junction channels are open in DKO mature fiber cells, leading to decreased conductance. Further work is needed to elucidate the probability of open channels in DKO lens fibers and the mechanisms that regulate channel opening in lens fiber cells.

It remains unclear how large gap junction plaques are formed on the broad sides of normal differentiating lens fibers. There are two possible mechanisms. 1) Connexins have high affinity for other connexins, and, thus, the proteins can aggregate to form large plaques (77). Previous studies showed that gap junctions move laterally along the plasma membrane, and when plaques come into contact, they will quickly fuse along their entire length (22, 45, 59). 2) The clustering of connexons can be initiated by an extrinsic signal (77). The signal that triggers connexon clustering is unknown, but statistical analysis of freeze-fracture electron microscopy images indicates that minimization of distance between apposing membranes (30 μm) holds connexon aggregates together and traps them in a specific area on the cell membrane (9).

Our current study shows that the actin-spectrin network completely surrounds the large membrane domains of gap junction plaques, which appear to occupy large empty lacunae in the network on the broad sides of the differentiating lens fiber cells. On the basis of a multitude of studies suggesting that single or small groups of connexons insert into the nonjunctional plasma membrane at random (reviewed in Ref. 77), it is reasonable to propose that, in newly differentiated wild-type lens fiber cells, connexons are inserted into small discontinuities in the actin-spectrin network on membranes of differentiating fiber cells. Indeed, in newly formed fiber cells, the actin-spectrin network is observed to be discontinuous and irregular, and as the fiber cells mature and elongate, the actin-spectrin network becomes smooth and continuous along fiber cell membranes, likely due to Tmod1 stabilization of F-actin filaments (72). Reinforcement of the actin-spectrin network coincides with the appearance of large gap junction plaques on the broad sides of differentiating fiber cells. Thus it is possible that smaller gap junction plaques may move laterally to form larger plaques, concomitant with maturation of the actin-spectrin network, and then are stabilized by the surrounding dense network. In contrast, in the DKO lens, the more fragmented appearance of Cx46 gap junction plaques is correlated with a moth-eaten (i.e., attenuated and fragmented) appearance of the normally continuous actin-spectrin network (36), and, as we show here, the gaps in the network appear to be filled with smaller disrupted Cx46 plaques (Fig. 7). In the absence of Tmod1 and CP49, the actin-spectrin network may not be reinforced and rearranged properly, thus destabilizing lateral accretion of the smaller Cx46 gap junction plaques into the large micrometer-sized plaques.

We observed disrupted Cx46 gap junction plaques in differentiating fiber cells of DKO lenses, while Cx50 gap junction plaques appear unaffected in these cells. This result suggests that Cx46 and Cx50 likely form homomeric and homotypic junctions in these lens fiber cells, as proposed by Mathias and colleagues (65). In support of this notion, the twofold decrease in conductance in the differentiating DKO lens fibers is phenotypically similar to loss of Cx46, where the Cx46−/− differentiating lens fibers also display a ∼60% decrease in conductance compared with wild-type differentiating lens fibers (37). It is unclear why Cx46, but not Cx50, gap junctions are affected in differentiating DKO lens fibers. One possibility is that since Cx50 is also expressed in lens epithelial cells (76), gap junction plaque assembly mechanisms of Cx50 may be distinct from those of Cx46, and Cx50 plaques may initiate assembly independent of the rearrangements of the actin-spectrin network during fiber cell differentiation. Further work is needed to understand the specific Cx46/Cx50-membrane cytoskeleton interaction and the mechanism for formation and accretion of Cx46 vs. Cx50 plaques.

Various studies have indicated that cytoskeletal proteins may also directly or indirectly interact with connexins and gap junction plaques. During lens fiber cell maturation, connexin staining signals change from large gap junction plaques in the middle of the broad sides of differentiating fiber cells to a dispersed pattern around the entire cell membrane (13, 43). The change in connexin distribution on the cell membranes of mature fibers coincides with cleavage of the cytoplasmic tails of Cx46 and Cx50 (20, 39, 43, 47), as well as cleavage of spectrins and disintegration of the actin-spectrin network (18, 41, 52, 53). Previous work in human and monkey lenses indicates that gap junction plaques are associated with actin filament bundles (57, 58). Actin filaments, in addition to microtubules, are also responsible for delivering connexons to gap junction plaques (33, 83) and can interact with connexins when cells undergo mechanical stress to stabilize gap junctions (86). Drebrin, an actin-binding protein that mediates cell polarity, stabilizes Cx43 gap junctions at the cell membrane (61) and controls the internalization or degradation of Cx43 proteins (10). Spectrin may affect gap junction proteins through interactions with zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1). ZO-1 has been shown to regulate Cx43 gap junction plaque size (42) and interact with the lens connexins Cx46 and Cx50 in vitro and in vivo (69, 70). Alpha-spectrin can also associate with Cx43 and ZO-1, as shown by coimmunoprecipitation studies (84). The interaction between connexins and the lens beaded intermediate filament network is less clear, and, on the basis of our results, the loss of beaded intermediate filaments in Tmod1+/+;CP49−/− lenses causes no obvious changes in conductance or in Cx46 and Cx50 gap junction plaques. Our previous study demonstrated an indirect biochemical link between Tmod1 and lens beaded intermediate filaments (36), and lens vimentin is known to associate with erythrocyte membranes in vitro specifically through ankyrin as an attachment protein (32). These data suggest that the effect of the loss of lens beaded intermediate filaments on gap junction plaque formation is likely the indirect consequence of disruption of the actin-spectrin network.

In summary, we have demonstrated that gap junction plaque formation by Cx46 in differentiating lens fiber cells is influenced by the actin-spectrin and beaded intermediate filament networks. Persistent holes in the actin-spectrin network in DKO differentiating fibers are correlated with scattered and smaller Cx46 gap junction plaques, which result in increased intracellular resistivity and decreased gap junction coupling conductance in mutant lenses. Our data also suggest that Cx46 and Cx50 are largely segregated in differentiating fiber cells and that these connexins likely form homomeric and homotypic channels. Our work indicates that proper gap junction plaque size and localization are associated with normal coupling of lens fiber cells.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grants R01 EY-017724 (to V. M. Fowler), R01 EY-06391 (to R. T. Mathias), and R01 EY-05314 (to W.-K. Lo).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.C., R.B.N., J.G., X.S., and S.K.B. performed the experiments; C.C., R.B.N., J.G., X.S., S.K.B., W.-K.L., and R.T.M. analyzed the data; C.C., R.B.N., W.-K.L., R.T.M., and V.M.F. interpreted the results of the experiments; C.C., R.B.N., J.G., X.S., S.K.B., and W.-K.L. prepared the figures; C.C. drafted the manuscript; C.C., W.-K.L., R.T.M., and V.M.F. edited and revised the manuscript; C.C. and V.M.F. approved the final version of the manuscript; V.M.F. developed the concept and designed the research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ciara Kamahele-Sanfratello for assistance with Western blotting and immunostaining experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alizadeh A, Clark J, Seeberger T, Hess J, Blankenship T, FitzGerald PG. Targeted deletion of the lens fiber cell-specific intermediate filament protein filensin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 5252–5258, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldo GJ, Gong X, Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Mathias RT. Gap junctional coupling in lenses from α8-connexin knockout mice. J Gen Physiol 118: 447–456, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldo GJ, Mathias RT. Spatial variations in membrane properties in the intact rat lens. Biophys J 63: 518–529, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassnett S. Lens organelle degradation. Exp Eye Res 74: 1–6, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassnett S, Winzenburger PA. Morphometric analysis of fibre cell growth in the developing chicken lens. Exp Eye Res 76: 291–302, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J Cell Biol 105: 2621–2629, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas SK, Brako L, Lo WK. Massive formation of square array junctions dramatically alters cell shape but does not cause lens opacity in the cav1-KO mice. Exp Eye Res 125: 9–19, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas SK, Jiang JX, Lo WK. Gap junction remodeling associated with cholesterol redistribution during fiber cell maturation in the adult chicken lens. Mol Vis 15: 1492–1508, 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun J, Abney JR, Owicki JC. How a gap junction maintains its structure. Nature 310: 316–318, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butkevich E, Hulsmann S, Wenzel D, Shirao T, Duden R, Majoul I. Drebrin is a novel connexin-43 binding partner that links gap junctions to the submembrane cytoskeleton. Curr Biol 14: 650–658, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candia OA, Mathias R, Gerometta R. Fluid circulation determined in the isolated bovine lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 7087–7096, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Candia OA, Zamudio AC. Regional distribution of the Na+ and K+ currents around the crystalline lens of rabbit. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C252–C262, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannell MB, Jacobs MD, Donaldson PJ, Soeller C. Probing microscopic diffusion by 2-photon flash photolysis: measurement of isotropic and anisotropic diffusion in lens fiber cells. Microsc Res Tech 63: 50–57, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang B, Wang X, Hawes NL, Ojakian R, Davisson MT, Lo WK, Gong X. A Gja8 (Cx50) point mutation causes an alteration of α3-connexin (Cx46) in semi-dominant cataracts of Lop10 mice. Hum Mol Genet 11: 507–513, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conley YP, Erturk D, Keverline A, Mah TS, Keravala A, Barnes LR, Bruchis A, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG, Weeks DE, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB. A juvenile-onset, progressive cataract locus on chromosome 3q21-q22 is associated with a missense mutation in the beaded filament structural protein-2. Am J Hum Genet 66: 1426–1431, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui X, Gao L, Jin Y, Zhang Y, Bai J, Feng G, Gao W, Liu P, He L, Fu S. The E233del mutation in BFSP2 causes a progressive autosomal dominant congenital cataract in a Chinese family. Mol Vis 13: 2023–2029, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das S, Wang H, Molina SA, Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Jena S, Bossmann LK, Miller KA, Mathias RT, Takemoto DJ. PKCγ, role in lens differentiation and gap junction coupling. Curr Eye Res 36: 620–631, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Maria A, Shi Y, Kumar NM, Bassnett S. Calpain expression and activity during lens fiber cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 284: 13542–13550, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeRosa AM, Mui R, Srinivas M, White TW. Functional characterization of a naturally occurring Cx50 truncation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 4474–4481, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson PJ, Grey AC, Merriman-Smith BR, Sisley AM, Soeller C, Cannell MB, Jacobs MD. Functional imaging: new views on lens structure and function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31: 890–895, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckert R. pH gating of lens fibre connexins. Pflügers Arch 443: 843–851, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falk M. Genetic tags for labelling live cells: gap junctions and beyond. Trends Cell Biol 12: 399–404, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer RS, Lee A, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin and tropomyosin mediate lens cell actin cytoskeleton reorganization in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41: 166–174, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FitzGerald PG. Lens intermediate filaments. Exp Eye Res 88: 165–172, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler VM. Tropomodulin: a cytoskeletal protein that binds to the end of erythrocyte tropomyosin and inhibits tropomyosin binding to actin. J Cell Biol 111: 471–481, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritz-Six KL, Cox PR, Fischer RS, Xu B, Gregorio CC, Zoghbi HY, Fowler VM. Aberrant myofibril assembly in tropomodulin1 null mice leads to aborted heart development and embryonic lethality. J Cell Biol 163: 1033–1044, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fudge DS, McCuaig JV, Van Stralen S, Hess JF, Wang H, Mathias RT, FitzGerald PG. Intermediate filaments regulate tissue size and stiffness in the murine lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 3860–3867, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao J, Sun X, Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Gong X, White TW, Mathias RT. Connections between connexins, calcium, and cataracts in the lens. J Gen Physiol 124: 289–300, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao J, Sun X, Moore LC, White TW, Brink PR, Mathias RT. Lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure is generated by the circulation of sodium and modulated by gap junction coupling. J Gen Physiol 137: 507–520, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J, Sun X, Yatsula V, Wymore RS, Mathias RT. Isoform-specific function and distribution of Na/K pumps in the frog lens epithelium. J Membr Biol 178: 89–101, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J, Wang H, Sun X, Varadaraj K, Li L, White TW, Mathias RT. The effects of age on lens transport. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 7174–7187, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Georgatos SD, Marchesi VT. The binding of vimentin to human erythrocyte membranes: a model system for the study of intermediate filament-membrane interactions. J Cell Biol 100: 1955–1961, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilleron J, Nebout M, Scarabelli L, Senegas-Balas F, Palmero S, Segretain D, Pointis G. A potential novel mechanism involving connexin 43 gap junction for control of Sertoli cell proliferation by thyroid hormones. J Cell Physiol 209: 153–161, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gokhin DS, Fowler VM. Cytoplasmic γ-actin and tropomodulin isoforms link to the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle fibers. J Cell Biol 194: 105–120, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gokhin DS, Lewis RA, McKeown CR, Nowak RB, Kim NE, Littlefield RS, Lieber RL, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin isoforms regulate thin filament pointed-end capping and skeletal muscle physiology. J Cell Biol 189: 95–109, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gokhin DS, Nowak RB, Kim NE, Arnett EE, Chen AC, Sah RL, Clark JI, Fowler VM. Tmod1 and CP49 synergize to control the fiber cell geometry, transparency, and mechanical stiffness of the mouse lens. PLos One 7: e48734, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong X, Baldo GJ, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Mathias RT. Gap junctional coupling in lenses lacking α3-connexin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15303–15308, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong X, Li E, Klier G, Huang Q, Wu Y, Lei H, Kumar NM, Horwitz J, Gilula NB. Disruption of α3-connexin gene leads to proteolysis and cataractogenesis in mice. Cell 91: 833–843, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gruijters WT, Kistler J, Bullivant S. Formation, distribution and dissociation of intercellular junctions in the lens. J Cell Sci 88: 351–359, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris AL. Connexin channel permeability to cytoplasmic molecules. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 94: 120–143, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris AS, Morrow JS. Calmodulin and calcium-dependent protease I coordinately regulate the interaction of fodrin with actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 3009–3013, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter AW, Barker RJ, Zhu C, Gourdie RG. Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol Biol Cell 16: 5686–5698, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs MD, Soeller C, Sisley AM, Cannell MB, Donaldson PJ. Gap junction processing and redistribution revealed by quantitative optical measurements of connexin46 epitopes in the lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 191–199, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakobs PM, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG, Kramer P, Weleber RG, Litt M. Autosomal-dominant congenital cataract associated with a deletion mutation in the human beaded filament protein gene BFSP2. Am J Hum Genet 66: 1432–1436, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jordan K, Solan JL, Dominguez M, Sia M, Hand A, Lampe PD, Laird DW. Trafficking, assembly, and function of a connexin43-green fluorescent protein chimera in live mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 10: 2033–2050, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kar R, Batra N, Riquelme MA, Jiang JX. Biological role of connexin intercellular channels and hemichannels. Arch Biochem Biophys 524: 2–15, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kistler J, Bullivant S. Protein processing in lens intercellular junctions: cleavage of MP70 to MP38. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28: 1687–1692, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar NM, Gilula NB. The gap junction communication channel. Cell 84: 381–388, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuszak JR. The ultrastructure of epithelial and fiber cells in the crystalline lens. Int Rev Cytol 163: 305–350, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuszak JR, Zoltoski RK, Sivertson C. Fibre cell organization in crystalline lenses. Exp Eye Res 78: 673–687, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuszak JR, Zoltoski RK, Tiedemann CE. Development of lens sutures. Int J Dev Biol 48: 889–902, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee A, Fischer RS, Fowler VM. Stabilization and remodeling of the membrane skeleton during lens fiber cell differentiation and maturation. Dev Dyn 217: 257–270, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee A, Morrow JS, Fowler VM. Caspase remodeling of the spectrin membrane skeleton during lens development and aging. J Biol Chem 276: 20735–20742, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li L, Lim J, Jacobs MD, Kistler J, Donaldson PJ. Regional differences in cystine accumulation point to a sutural delivery pathway to the lens core. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 1253–1260, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim J, Lam YC, Kistler J, Donaldson PJ. Molecular characterization of the cystine/glutamate exchanger and the excitatory amino acid transporters in the rat lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 2869–2877, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim J, Lorentzen KA, Kistler J, Donaldson PJ. Molecular identification and characterisation of the glycine transporter (GLYT1) and the glutamine/glutamate transporter (ASCT2) in the rat lens. Exp Eye Res 83: 447–455, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lo WK, Mills A, Kuck JF. Actin filament bundles are associated with fiber gap junctions in the primate lens. Exp Eye Res 58: 189–196, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo WK, Shaw AP, Takemoto LJ, Grossniklaus HE, Tigges M. Gap junction structures and distribution patterns of immunoreactive connexins 46 and 50 in lens regrowths of rhesus monkeys. Exp Eye Res 62: 171–180, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lopez P, Balicki D, Buehler LK, Falk MM, Chen SC. Distribution and dynamics of gap junction channels revealed in living cells. Cell Commun Adhes 8: 237–242, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lovicu FJ, Robinson ML. Development of the Ocular Lens. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. xv. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Majoul I, Shirao T, Sekino Y, Duden R. Many faces of drebrin: from building dendritic spines and stabilizing gap junctions to shaping neurite-like cell processes. Histochem Cell Biol 127: 355–361, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Sellitto C, Li L, Gong X, Brink PR, Mathias RT, White TW. Dominant cataracts result from incongruous mixing of wild-type lens connexins. J Cell Biol 161: 969–978, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mathias RT, Rae JL, Baldo GJ. Physiological properties of the normal lens. Physiol Rev 77: 21–50, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mathias RT, Rae JL, Eisenberg RS. The lens as a nonuniform spherical syncytium. Biophys J 34: 61–83, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathias RT, White TW, Gong X. Lens gap junctions in growth, differentiation, and homeostasis. Physiol Rev 90: 179–206, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McKeown CR, Nowak RB, Moyer J, Sussman MA, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin1 is required in the heart but not the yolk sac for mouse embryonic development. Circ Res 103: 1241–1248, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Merriman-Smith BR, Krushinsky A, Kistler J, Donaldson PJ. Expression patterns for glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 in the normal rat lens and in models of diabetic cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 3458–3466, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moyer JD, Nowak RB, Kim NE, Larkin SK, Peters LL, Hartwig J, Kuypers FA, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin 1-null mice have a mild spherocytic elliptocytosis with appearance of tropomodulin 3 in red blood cells and disruption of the membrane skeleton. Blood 116: 2590–2599, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Giepmans BN, Kumar NM. Characterization of the association of connexins and ZO-1 in the lens. Cell Commun Adhes 8: 213–217, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Shestopalov VI, Giepmans BN, Dunia I, Benedetti EL, Kumar NM. Lens connexins α3-Cx46 and α8-Cx50 interact with zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1). Mol Biol Cell 14: 2470–2481, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nowak RB, Fischer RS, Zoltoski RK, Kuszak JR, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin1 is required for membrane skeleton organization and hexagonal geometry of fiber cells in the mouse lens. J Cell Biol 186: 915–928, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nowak RB, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin 1 constrains fiber cell geometry during elongation and maturation in the lens cortex. J Histochem Cytochem 60: 414–427, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oka M, Kudo H, Sugama N, Asami Y, Takehana M. The function of filensin and phakinin in lens transparency. Mol Vis 14: 815–822, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piatigorsky J. Lens differentiation in vertebrates. A review of cellular and molecular features. Differentiation 19: 134–153, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Puk O, Loster J, Dalke C, Soewarto D, Fuchs H, Budde B, Nurnberg P, Wolf E, de Angelis MH, Graw J. Mutation in a novel connexin-like gene (Gjf1) in the mouse affects early lens development and causes a variable small-eye phenotype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 1525–1532, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rong P, Wang X, Niesman I, Wu Y, Benedetti LE, Dunia I, Levy E, Gong X. Disruption of Gja8 (α8-connexin) in mice leads to microphthalmia associated with retardation of lens growth and lens fiber maturation. Development 129: 167–174, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Segretain D, Falk MM. Regulation of connexin biosynthesis, assembly, gap junction formation, and removal. Biochim Biophys Acta 1662: 3–21, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shi Y, De Maria AB, Wang H, Mathias RT, FitzGerald PG, Bassnett S. Further analysis of the lens phenotype in Lim2-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 7332–7339, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simirskii VN, Lee RS, Wawrousek EF, Duncan MK. Inbred FVB/N mice are mutant at the cp49/Bfsp2 locus and lack beaded filament proteins in the lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 4931–4934, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sonntag S, Sohl G, Dobrowolski R, Zhang J, Theis M, Winterhager E, Bukauskas FF, Willecke K. Mouse lens connexin23 (Gje1) does not form functional gap junction channels but causes enhanced ATP release from HeLa cells. Eur J Cell Biol 88: 65–77, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tamiya S, Dean WL, Paterson CA, Delamere NA. Regional distribution of Na,K-ATPase activity in porcine lens epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 4395–4399, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taylor VL, al-Ghoul KJ, Lane CW, Davis VA, Kuszak JR, Costello MJ. Morphology of the normal human lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37: 1396–1410, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomas T, Jordan K, Laird DW. Role of cytoskeletal elements in the recruitment of Cx43-GFP and Cx26-YFP into gap junctions. Cell Commun Adhes 8: 231–236, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Toyofuku T, Yabuki M, Otsu K, Kuzuya T, Hori M, Tada M. Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin-43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 273: 12725–12731, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vaghefi E, Walker K, Pontre BP, Jacobs MD, Donaldson PJ. Magnetic resonance and confocal imaging of solute penetration into the lens reveals a zone of restricted extracellular space diffusion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R1250–R1259, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wall ME, Otey C, Qi J, Banes AJ. Connexin 43 is localized with actin in tenocytes. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 64: 121–130, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang H, Gao J, Sun X, Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Li L, Varadaraj K, Farrell M, Reddy VN, White TW, Mathias RT. The effects of GPX-1 knockout on membrane transport and intracellular homeostasis in the lens. J Membr Biol 227: 25–37, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.White TW, Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Targeted ablation of connexin50 in mice results in microphthalmia and zonular pulverulent cataracts. J Cell Biol 143: 815–825, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woo MK, Fowler VM. Identification and characterization of tropomodulin and tropomyosin in the adult rat lens. J Cell Sci 107: 1359–1367, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamashiro S, Gokhin DS, Kimura S, Nowak RB, Fowler VM. Tropomodulins: pointed-end capping proteins that regulate actin filament architecture in diverse cell types. Cytoskeleton 69: 337–370, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoon KH, Blankenship T, Shibata B, Fitzgerald PG. Resisting the effects of aging: a function for the fiber cell beaded filament. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 1030–1036, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang L, Gao L, Li Z, Qin W, Gao W, Cui X, Feng G, Fu S, He L, Liu P. Progressive sutural cataract associated with a BFSP2 mutation in a Chinese family. Mol Vis 12: 1626–1631, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]