Abstract

One of the hallmarks of cancer is aberrant DNA methylation, which is associated with abnormal gene expression. Both hypermethylation and silencing of tumour suppressor genes as well as hypomethylation and activation of prometastatic genes are characteristic of cancer cells. As DNA methylation is reversible, DNA methylation inhibitors were tested as anticancer drugs with the idea that such agents would demethylate and reactivate tumour suppressor genes. Two cytosine analogues, 5-azacytidine (Vidaza) and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, were approved by the Food and Drug Administration as antitumour agents in 2004 and 2006 respectively. However, these agents might cause activation of a panel of prometastatic genes in addition to activating tumour suppressor genes, which might lead to increased metastasis. This poses the challenge of how to target tumour suppressor genes and block cancer growth with DNA-demethylating drugs while avoiding the activation of prometastatic genes and precluding the morbidity of cancer metastasis. This paper reviews current progress in using DNA methylation inhibitors in cancer therapy and the potential promise and challenges ahead.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Epigenetics and Therapy. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2015.172.issue-11

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRsa | HDAC1 |

| CXCR4 | MMP2 |

| Enzymesb | MMP9 |

| DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) | uPA (PLAU) |

| Histone deacetylases (HDACs) | |

| LIGANDS | |

| 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) | Oxaliplatin |

| 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine | Paclitaxel |

| 5-fluorouracil | SAHA (entinostat) |

| Adriamycin (doxorubicin) | SAM |

| ATP | Trichostatin A |

| Cisplatin | Valproic acid |

| Irinotecan (SN38) |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are bpermanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,bAlexander et al., 2013a,b).

DNA methylation overview

DNA methylation is an enzymatically catalysed covalent modification of DNA, occurring typically in the context of cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides. In general, regions with high CpG content, named CpG islands, are demethylated in normal cells, whereas regions with an intermediate or low density of CpGs are differentially methylated in some tissues, but not in others (Bird et al., 1985). Although rarely observed, non-CpG methylation is mainly found in embryonic stem cells (Lister et al., 2009), but its function needs to be further explored. However, non-CpG methylation is abundant in adult brains, and recent data suggest that it plays a role in silencing promoter activity similar to CpG methylation (Guo et al., 2013; Lister et al., 2013).

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) catalyse the transfer of a methyl group from its donor S-adenosine-methionine (SAM) to the cytosine nucleotide of DNA. Three distinct phylogenic DNMTs were identified in mammals. DNMT1 is a maintenance DNMT, which shows preference for hemimethylated DNA in vitro and faithfully copies DNA methylation in a cytosine-guanine (CG) palindromic dinucleotide from the parental strand to the daughter strand during cell division (Zucker et al., 1985; Flynn et al., 1996; Pradhan et al., 1999; Fatemi et al., 2001). DNMT3a and DNMT3b methylate unmethylated and hemimethylated DNA at an equal rate, which is consistent with a de novo methylation function (Okano et al., 1998). In addition, a demethylation activity was recently attributed to mammalian de novo DNMT3A and DNMT3B (Chen et al., 2013).

DNA methylation reversibility is one of the most controversial questions in the DNA methylation field. Over an extensive period of time, it was strongly believed that demethylation of DNA is a passive phenomenon. Methyl CpG binding domain 2 was the first protein suggested to have demethylase activity (Bhattacharya et al., 1999a; Cervoni and Szyf, 2001b; Detich et al., 2003a,b,; Hamm et al., 2008), although this activity is highly disputed. Moreover, several enzymes, acting together, are shown to be implicated in passive and active DNA demethylation (Kohli and Zhang, 2013), such as the ten–eleven translocation (TET) methylcytosine dioxygenases (Iyer et al., 2009; Tahiliani et al., 2009; Pastor et al., 2013), activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (Bhutani et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2013) and thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) (Cortazar et al., 2011; Cortellino et al., 2011). First, TET was suggested to block maintenance of DNA methylation during replication, requiring DNMT1 and ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains, 1 (UHRF1) proteins (Bostick et al., 2007), and lead to a passive demethylation. Experiments in vitro showed a reduction in UHRF1 binding (10-fold) and in recombinant DNMT1 activity at sites of hemi 5hmC in comparison with hemi 5mC (Hashimoto et al., 2012). Alternatively, repair-based DNA demethylation could result from the combined action of TET proteins with AID (DNA cytosine) resulting in transformation of the methyl cytosine, triggering a repair mechanism that can involve glycosylases that remove the deaminated hydroxyl-methylated modified base such as TDG (Guo et al., 2011; He et al., 2011).

Not all CGs in the genome are methylated. A fraction of CGs remains unmethylated and the fraction of the genome that is unmethylated is different from tissue to tissue, creating a tissue-specific pattern of methylation. Razin and Riggs have proposed, three decades ago, that the pattern of methylation is responsible for tissue-specific gene expression (Razin and Riggs, 1980). Hypermethylated DNA is packaged in inactive chromatin associated with silent genes (Razin and Cedar, 1977), while transcriptionally active regions of the chromatin are associated with hypomethylated DNA. DNA methylation at 5′ regions of genes can silence transcription initiation (Blattler and Farnham, 2013; Baubec and Schubeler, 2014) in reporter assays in cell culture, and it is believed that it plays a similar role in vivo (Stein et al., 1982; Cedar et al., 1983). There are different mechanisms that are involved in silencing of gene expression by DNA methylation such as interference of methylation at cytosines with binding of transcription factors (Comb and Goodman, 1990; Inamdar et al., 1991) or through attracting methylated DNA binding proteins, such as MeCP2 to methylated DNA (Nan et al., 1997). MeCP2, in turn, recruits other proteins such as SIN3A and histone-modifying enzymes, which lead to the formation of a ‘closed’ chromatin configuration and silencing of gene expression (Nan et al., 1997).

Although DNA methylation is described as a repressive epigenetic mark, its association with gene transcription depends on its location. Many methylated CG sites are found in intergenic and intragenic regions. As described earlier, DNA methylation in promoters or enhancers suppresses gene expression (Comb and Goodman, 1990; Inamdar et al., 1991). However, DNA methylation in intragenic regions, within the body of coding genes, is positively correlated with gene expression (Ball et al., 2009; Rauch et al., 2009; Aran et al., 2011), which is illustrated by the study on the active X chromosome (Hellman and Chess, 2007). The role of DNA methylation in gene bodies remains poorly understood; however, several ideas on its possible role are starting to emerge. A recent study showed that a small fraction (5–15%) of all methylated intronic regions (containing initiation transcription sites) could repress initiation of intragenic transcription suggesting a possibility for DNA methylation to suppress spurious transcriptional firing (Jjingo et al., 2012). A different study linked gene body DNA methylation and reduction in transcriptional elongation (Lorincz et al., 2004). Several studies postulated a role for DNA methylation in splicing, and a particular role for the methylated DNA binding protein MeCP2 (Young et al., 2005; Cingolani et al., 2013; Maunakea et al., 2013). Gelfman et al. suggest a role for gene body DNA methylation during transcription-linked splicing (Gelfman et al., 2013). The data suggest that these effects of DNA methylation are dependent on the CG distribution architecture at exon and intron boundaries.

DNA methylation is implicated in several gene regulatory pathways in addition to cellular differentiation during development such as suppression of retrotransposon expression, X chromosome inactivation and gene parental imprinting (Jones, 2012; Smith and Meissner, 2013).

DNA methylation in disease and its therapeutic implications

Although DNA methylation plays an important role in setting up cell type identity, it is not an exclusively static mark after birth, but is dynamic to a certain extent during the life course. It can be responsive to experience and environmental exposures such as socio-economic positioning, stress and dietary supplements, etc. (McGowan et al., 2009; Borghol et al., 2012). The dynamic nature of DNA methylation pattern is a balance of DNMTs and putative demethylase activities (Bhattacharya et al., 1999b; Chen et al., 2013).

Aberrant methylation in cancer is characterized by hypermethylation of CG islands in tumour suppressor genes, as well as non-CG island CGs in other promoters and hypomethylation of unique genes and repetitive elements (Issa et al., 1993; Baylin et al., 2001; Ehrlich, 2002). These changes in DNA methylation may be partially explained by aberrant expression of methyltransferases (Issa et al., 1993) and putative demethylases (Patra et al., 2002). Interestingly, several nodal oncogenic pathways up-regulate DNMT1 and demethylase activity (MacLeod et al., 1995a; Rouleau et al., 1995; Szyf et al., 1995), and tumour suppressor Rb negatively regulates DNMT1 (Slack et al., 1999). Hypermethylation of tumour suppressor genes leads to their inactivation and is highly implicated in cancer growth. In contrast, the up-regulation of prometastatic genes, induced by DNA hypomethylation, promotes invasion and metastasis pathways, one of the most morbid aspects of cancer (Pakneshan et al., 2004; Shukeir et al., 2006). Hence, DNA hyper- and hypomethylation trigger different cellular mechanisms involved in cancer (Stefanska et al., 2011).

DNA methylation steady state can be modulated by pharmacological reagents, dietary supplements and other chemicals (Day et al., 2002; Szyf, 2005). This fact makes DNA methylation much more attractive as a therapeutic target than fixed and irreversible genetic mutations. Cancer was one of the first diseases where DNA methylation was proposed as a therapeutic target (Szyf, 1994). The main focus of drug development in cancer therapy has been on developing DNMT inhibitors with the goal of demethylating and activating tumour suppressor genes silenced by DNA methylation. Accordingly, two drugs, 5-azacytidine (5-azaC), and its deoxy analogue, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azadC), are currently used in clinical practice as a general inhibitor of all DNMTs. These drugs were the first epigenetic drugs approved by the FDA for anticancer treatment. In addition to activation of tumour suppressors, 5-azaC and 5-azadC were reported to up-regulate a panel of prometastatic genes that stimulate cancer cell invasiveness and metastasis formation (Ateeq et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2010; Chik and Szyf, 2011a).

Therefore, the challenge in the field of DNA methylation drugs is to identify specific inhibitors of DNA methylation that target the growth-silencing functions without triggering activation of prometastatic genes. This review focuses on the current state of DNA methylation drug discovery and provides a perspective for the future directions in anticancer therapy.

Mechanisms of action of 5-azaC and 5-azadC

5-azaC (Vidaza) (Kuendgen and Lubbert, 2008) is an analogue of cytidine ribose nucleoside and its deoxy derivative is the 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine nucleoside (5-azadC, Decitabine or Dacogen). They were first synthesized in the early 1960s (Sorm et al., 1964) and were later demonstrated to inhibit DNMT activity (Jones and Taylor, 1980).

5-azaC and 5-azadC are prodrugs that require activation via phosphorylation to be incorporated into the DNA during replication (Stresemann and Lyko, 2008). Once incorporated, both, non-modified cytosine CG dinucleotides and modified azacytosine-guanine are recognized by DNMTs during replication and DNA methylation initiation reaction, thereby leading to a widespread genomic hypomethylation (Esteller, 2005; Momparler, 2005). In contrast to the intact cytosine, DNMTs form an irreversible covalent bond with the carbon at position 6 of the azacytosine ring trapping the DNMT on the nascent strand of DNA during DNA synthesis, preventing the regeneration of the catalytic cysteine and passive loss of DNA methylation in the extending nascent strand (Wu and Santi, 1985). Interestingly, 5-azaC can cause demethylation in non-dividing neurons (Miller and Sweatt, 2007). It stands to reason, therefore, that 5-azaC can act through an additional mechanism that does not require its incorporation into replicating DNA, for example by triggering proteasomal degradation of DNMTs (Ghoshal et al., 2005).

Although these two drugs are incorporated into DNA (Li et al., 1970), only 5-azaC can be incorporated into RNA and cause the inhibition of RNA and protein synthesis (Jiří Veselý, 1978). Cihak et al. demonstrated that 5-azaC administration induces a rapid degradation of polyribosomes and subsequent inhibition of protein synthesis (Cihak et al., 1968). It was reported, that 5-azaC changes the structure of the ribosomal precursor RNAs and inhibits the processing of ribosomal RNA (Jiří Veselý, 1978).

5-azadC is more potent and more cytotoxic than 5-azaC (at least 10-fold) (Flatau et al., 1984; Momparler et al., 1984). Moreover, toxic DNMT-5-azadC complexes might be triggering long-term side effects such as mutations and chromosomal re-arrangements (Juttermann et al., 1994). Hypomethylation, mediated by 5-azadC, was found to be directly involved in mismatch repair deficiency leading to gains and losses of chromosomes (Lengauer et al., 1997). Demethylation is also associated with mitotic dysfunction and translocation (Schmid et al., 1984; Thomas, 1995). In addition to activation of gene expression through promoter demethylation, hypomethylation causes genomic instability (Chen et al., 1998) and unleashes the expression of repetitive sequences disrupting gene expression programming (Howard et al., 2007).

5-azaC and 5-azadC mediate inactivation of all DNMT isoforms, cause demethylation and reactivation of a wide panel of tumour suppressor and other genes, and are able to block cancer growth (Ghoshal and Bai, 2007). These effects made these two drugs promising in cancer therapy. However, in addition to affecting growth, 5-azaC and 5-azadC can activate metastatic genes such as HEPARANASE (Shteper et al., 2003) and uPA, which play an important role in metastasis (Pakneshan et al., 2004; Shukeir et al., 2006). This raises a critical challenge in using DNA methylation inhibitors: How to dissociate the growth inhibitory activities of DNMT inhibitors from the prometastatic activity?

Contradictory effects of 5-azaC and 5-azadC on cell invasion and apoptosis

While there is agreement regarding 5-azaC and 5-azadC anti-proliferative effects in cancer (Thakur et al., 2012; Jeschke et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Chik et al., 2014), their effects on cell migration and invasion are highly controversial. It was reported that 0.2 μM 5-azaC inhibits invasiveness of human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-468 cells (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2004); 5 μM 5-azaC reduces migration of a human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line H1299 (Mateen et al., 2013); 10 μM 5-azaC reduces migration and invasiveness in ovarian tumour cells BeWo (Rahnama et al., 2006), and 5-azadC inhibits migration and invasion of bladder cancer T24 cell line (Zhang et al., 2013). However, other studies that span several decades have demonstrated an increase in cell invasion and metastasis in animal tumour models (Olsson and Forchhammer, 1984; Habets et al., 1990). One and 5 μM 5-azadC convert non-metastatic breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and ZR-75-1) to invasive cells in vitro and in vivo (Ateeq et al., 2008; Chik et al., 2014); 5 μM 5-azadC increases human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells invasion through induction of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), which was up-regulated 44.6-fold through recruitment of RNA Pol II and Sp1 to its promoter compared with non-treated cells. 5-azadC also up-regulated MMP2 (1.9-fold), and MMP9 (8.6-fold) (Poplineau et al., 2013). In another study, 1 μM 5-azadC increased the invasiveness of several pancreatic cancer cell lines (Sato et al., 2003).

5-azaC and 5-azadC treatment in leukaemia

5-azaC (Vidaza) and 5-azadC (Decitabine) were approved by the FDA for treatment of childhood acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Vidaza demonstrated activity in 15–25% of AML (Cashen et al., 2010; Fenaux et al., 2010; Kantarjian et al., 2012). In elderly patients, AML is associated with poor prognosis with 10% 2 year overall survival (OS) and only 2% 5 year survival (Menzin et al., 2002). In a phase II study, during which 55 elderly AML patients were treated with decitabine, complete remission was observed in 24% of patients (Cashen et al., 2010). Moreover, it was demonstrated (Fenaux et al., 2010) that 5-azaC treatment, in a phase III trial, significantly increased the OS of elderly patients with low marrow blast count World Health Organization-defined AML. Half of the treated patients were still alive after 2 years in comparison with only 16% in the conventional care regimen group (Fenaux et al., 2010). These results were recently confirmed by Pleyer et al., who showed that 62% of a group of 48 elderly patients (mean 71 years old) survived for 2 years after 5-azaC treatment (Pleyer et al., 2014).

Decitabine is clinically effective for the treatment of MDS, and was shown to improve time to AML transformation or death. Indeed, patients treated with Decitabine had a greater median time to AML transformation or death (4.3 months) than patients receiving supportive care alone (Kantarjian et al., 2012).

These results emphasize the high efficacy of 5-azaC and 5-azadC as drugs for treating leukaemia. Currently, clinical efforts are focused on the possibility that these drugs could be effective in treating solid tumours as well (For the list of recent clinical trials with 5-azaC and 5-azadC see Supporting Information Table S1.).

5-azaC and 5-azadC effects on solid tumours

Solid tumour size reduction upon 5-azaC treatment was observed in several studies using mice models of breast (Thakur et al., 2012) and spleen tumours (Mikyskova et al., 2014). Lindner et al. demonstrated that 5-azadC treatment reduces tumour vascularization as well as tumour volume (Lindner et al., 2013). A phase I study, on invasive urothelial cancer in a canine model with 5-azaC, showed an antitumour activity with 22% of partial remission and 56% of tumour size reduction (Hahn et al., 2012).

Several clinical trials on patients with solid tumours were performed in the past. However, few of them focused only on 5-azaC and 5-azadC effects as a monotherapy; most used combinations of 5-azaC/dC and other chemotherapeutic agents (discussed later). The first clinical trials using 5-azaC alone in phase I and II studies in solid tumours were performed during the 1970s. An antitumour effect was demonstrated in 17 and 21% of patients with breast carcinoma and malignant lymphomas, respectively, who were treated with a dose of 1.6 mg·kg−1day−1 of 5-azaC for 10 days (Weiss et al., 1977). In another study, with doses of 5-azaC ranging from 1.0 to 24.0 mg·kg−1 given over a minimal period of 8 days, remission was observed in 11 out of 30 patients with a variety of solid tumours (Weiss et al., 1972; 1977,). However, responses to 5-azaC were transient with a minimal effect on other solid tumours (Weiss et al., 1977). One of the major problems in all these studies was toxicity. Because of the toxic effects (myelosuppressive, gastrointestinal, sepsis and cerebral haemorrhage), leucopoenia and thrombocytopenia in another study (Weiss et al., 1972) the initial dose of 225 mg·m−2 (i.v., on days 1–5 every 3 weeks) was reduced to 150 mg·m−2 in one study (Quagliana et al., 1977). It also became clear that these drugs should not be used as a single agent in solid tumours.

Other phase I studies analysed the effects of 5-azadC in patients with solid tumours, such as non-small cell lung carcinoma, thoracic malignancies, renal cell carcinoma, malignant pleural mesothelioma, and lung and oesophageal cancers (Momparler and Ayoub, 2001; Aparicio et al., 2003; Samlowski et al., 2005; Schrump et al., 2006). Although these studies show that 5-azadC treatment induces a significant DNA hypomethylation (Aparicio et al., 2003; Samlowski et al., 2005), causes gene induction (Schrump et al., 2006) and increases the survival duration of the patients (Momparler et al., 1997, Momparler and Ayoub, 2001), these studies did not report a reduction in tumour size.

What is the mechanism of action of the antitumour effect of 5-azaC in solid tumours? A large body of data has established that 5-azaC has a broad effect on the expression of tumour suppressor genes, cell cycle regulatory genes and antiapoptotic genes in many solid cancer cell lines. For example, a recent study performed an integrated expression and methylation analysis on 63 different cancer cell lines (breast, ovarian and colorectal) treated with 5-azaC (Li et al., 2014). In this study, 5-azaC was shown to affect key biological pathways involved in tumourigenesis such as, inter alia, cell cycle and mitotic pathways, and transcription and DNA replication. Additionally, 5-azaC induced an up-regulation of immunomodulatory genes, which might suggest an immunomodulatory function for 5-azaC in multiple solid tumour cancers, which can be classified as immune low or immune enriched (Li et al., 2014). However, it is unclear whether similar mechanisms are at work in patients treated with 5-azaC/dC. For information regarding current ongoing clinical studies on colorectal and ovarian cancers, see Supporting Information Table S1.

Using 5-azaC and 5-azadC in combination with other agents

Both 5-azadC and 5-azaC exhibited rather disappointing results against solid tumours (Aparicio and Weber, 2002). Perhaps, this might be due to the relative instability of 5-azaC/dC (Lin et al., 1981) and its potential deamination and inactivation in vivo (Momparler et al., 1984). This prompted the idea of using 5-azaC/dC in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. The rationale being that 5-azaC can possibly reduce resistance to chemotherapy that is caused by DNA methylation and silencing of genes involved in chemotherapeutic response. These ideas were tested in cell culture. For example, cell culture experiments demonstrated antiproliferative effects in MDA-MB-231 when 5-azadC was used in combination with anticancer agents: paclitaxel (PTX), adriamycin or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), while in MCF-7 semi-additive antiproliferative effects were observed only with a combination of 5-azadC and 5-FU in comparison with the treatme nt with each of the drugs on its own (Mirza et al., 2010).

In another study, 5-azadC had an antiproliferative effect and increased apoptosis in combination with anticancer drugs 5-FU, PTX, oxaliplatin, SN38 (irinotecan), and gemcitabine in human gastric cancer cell lines when treated simultaneously as compared with monotherapy (Zhang et al., 2006).

The clinical results are less conclusive. In a clinical study on 29 ovarian cancer patients the effect of carboplatin, a chemopreventive reagent, was compared with combined effect of carboplatin with 5-azaC (Glasspool et al., 2014) (For additional information regarding ongoing clinical trial on ovarian cancer using carboplatin and decitabine refer to Supporting Information Table S1.). In the combination group, the use of 5-azaC reduced the efficacy of carboplatin in partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Moreover, hypersensitivity reactions reduced deliverability of the combination of 5-azaC with carboplatin on a 28 day schedule (Glasspool et al., 2014).

Combination of 5-azaC and 5-azadC and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors

There is a crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone acetylation (Cervoni and Szyf, 2001b; Cervoni et al., 2001a; D'Alessio and Szyf, 2006). Methylated DNA binding proteins recruit HDACs to genes resulting in histone deacetylation, and HDAC inhibitors induce DNA demethylation (Detich et al., 2003a). This is supported by the in vitro interaction of DNMT1 with HDAC1 (Fuks et al., 2000; Ou et al., 2007; Palii and Robertson, 2007). Therefore, several studies examined the combinatory effects of 5-azaC and 5-azadC with other HDAC inhibitors in vitro. Cameron et al. were the first to show synergistic effects in activation of tumour suppressor genes of the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) and 5-azadC (Cameron et al., 1999). Particularly, they demonstrated that several genes, silenced by methylation, were induced with a combination treatment of 5-azadC and TSA, but not when treated with only 5-azadC. Numerous papers have replicated this observation in the last decade and a half (Griffiths and Gore, 2008)

Moreover, it was found that TSA, 5-azadC and cisplatin, a DNA cross-linking agent, commonly used to treat ovarian cancer, alone or in combination, significantly suppressed spheroid formation and growth of ovarian cancer cells in vitro, and sequential treatment of epigenetic modifiers and low-dose cisplatin reduced tumourigenesis more effectively than either drug alone in xenograft mouse models (Meng et al., 2013).

Another combination of 5-azaC with valproate (valproic acid, VPA) attracted attention. VPA initially used for epilepsy treatment was demonstrated to also act as a HDAC inhibitor (Gottlicher et al., 2001; Phiel et al., 2001). Although, the combination of VPA and decitabine reactivates hypermethylated genes as demonstrated by re-expressing fetal haemoglobin, this combination is limited by toxicity, specifically by neurological symptoms in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (Chu et al., 2013). Another HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, when combined with 5-azadC, inhibited mammary tumourigenesis in a murine model (Elangovan et al., 2013). Similarly, 5-azadC, in combination with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), a different HDAC inhibitor, inhibited hepatoma cell growth in a human hepatoma xenograft model (Venturelli et al., 2007). In another study, a combination of 5-azadC and SAHA activated tumour suppressor genes ARHI and PEG3, and inhibited tumour growth in a xenograft model (Chen et al., 2011). The effect of combined treatment of two HDAC inhibitors VPA and SAHA with 5-azadC was also shown in a murine model of mesothelioma to kill malignant pleural mesothelioma cells and induce tumour antigen expression in the remaining living tumour cells (Leclercq et al., 2011).

Overall, in vivo studies show that combination of reagents targeting different epigenetic levels of gene regulation machinery (DNA methylation and histone modifications), is more efficient than monotherapy, and this is reflected in augmentation and overall activation of silenced genes in cancer. However, it is clear that 5-azaC-based therapeutics encounter serious challenges in treatment of solid tumours. Other approaches to DNA methylation-based therapy need to be developed in order to realize the potential of DNA methylation-based therapeutics.

Inhibition of DNMT1 as anticancer therapy

As discussed previously, the main challenge in cancer therapy is how to target tumour suppressor genes and stop cancer growth with DNMT inhibitors while avoiding the activation of prometastatic genes. Is it possible, by selective targeting of these mechanisms, to enhance the specificity and reduce the toxicity of DNMT inhibitors in cancer?

There is an urgent necessity to develop new, potent and selective DNMT inhibitors that possess good pharmacokinetic profiles with minimal toxicity. Based on several studies, isoform-specific inhibitors of DNMT1 might be a reasonable strategy for anticancer therapeutics. It was demonstrated, that overexpression of DNMT1 in non-transformed cells leads to cellular transformation (Wu et al., 1993). The anticancer effects of DNMT1 inhibition were demonstrated both pharmacologically and genetically using antisense oligonucleotide inhibitors (MacLeod and Szyf, 1995b; Ramchandani et al., 1997) and dnmt1−/− mice (Laird et al., 1995) respectively. Although depletion of DNMT1 had the strongest effect on colony growth suppression in cellular transformation assays, it did not result in demethylation and activation of uPA, S100A4, MMP2 and CXCR4 in MCF-7 cells. It was demonstrated, that depletion of DNMT1 did not induce cellular invasion in either MCF-7 or ZR-75-1 non-invasive breast cancer cell lines and did not lead to activation of prometastic genes (uPA, HEPARANAZE) (Chik and Szyf, 2011b). Taken together, these data support the idea that selective inhibition of DNMT1 rather than pan inhibition of DNMTs should be a reasonable strategy for anticancer therapeutics. New approaches that are more selective than Vidaza might also enhance the overall antitumour activity of DNA methylation inhibitors.

Prospect of using SAM in anticancer therapeutics

The landscape of DNA methylation in cancer involves both loss and gain of DNA methylation (Stefanska et al., 2011). Importantly, DNA demethylation is associated with an activation of genes involved in migration and movement, functions required for metastasis formation (Nakamura and Takenaga, 1998; Guo et al., 2002; Rosty et al., 2002; Szyf, 2005; Ateeq et al., 2008). Therefore, it stands to reason that blocking these demethylation events might provide some therapeutic effect against cancer metastasis.

SAM (AdoMet) is the methyl donor in cellular methylation reactions. SAM is a natural product that is synthesized from ATP and methionine by methionine adenosyltransferase (Cantoni, 1953). The methyl group CH3, of SAM, is transferred to cell components such as DNA, proteins and lipids (Lu and Mato, 2005; Roje, 2006). There are several mechanisms by which SAM alters DNA methylation. The balance of SAM and S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH) is critical for DNMT activity, as SAH inhibits DNMT. SAM also inhibits demethylase activity (Detich et al., 2003b).

Clinical efficacy of SAM in depression, osteoarthritis and liver diseases was demonstrated in dozens of studies summarized in the report, which searched through 25 biomedical databases (Hardy et al., 2003; Lu and Mato, 2012). There is extensive in vitro evidence that SAM suppress both growth and invasion in highly invasive cell lines (Pakneshan et al., 2004; Shukeir et al., 2006). In vivo, SAM was demonstrated to inhibit invasiveness and metastasis of human breast (Pakneshan et al., 2004), prostate and colorectal cancer cell lines (Hussain et al., 2013). Several studies demonstrated that SAM treatment had a chemopreventive effect in liver cancer in rat (Pascale et al., 2002). A possible mechanism for SAM action is silencing the expression of prometastatic genes through DNA methylation (van der Westhuyzen, 1985; Fuso et al., 2001; Ross, 2003; Pakneshan et al., 2004; Shukeir et al., 2006; Chik et al., 2014).

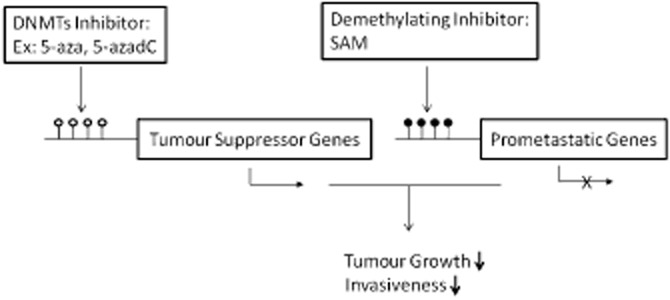

Using several cytotoxic assays, it was demonstrated that SAM specifically enhances the anticancer effect of 5-FU, but not that of cisplatin (Ham et al., 2013). We have recently demonstrated that SAM antagonizes the effects of 5-azadC on cell invasiveness and increases the antigrowth effects of 5-azadC, more than this, SAM inhibited the global hypomethylation induced by 5-azadC (Figure 1) (Chik et al., 2014). However, SAM has broad pleoitropic effects and there is a need to develop more target-specific inhibitors that target DNA demethylation events that are critical for cancer by focusing on proteins that are involved in these demethylation reactions.

Figure 1.

Combinatory effect of demethylating drugs and demethylating inhibitor. DNMTs inhibitors (5-azaC and 5-azadC) target tumour suppressor and prometastatic genes by demethylating promoters and inducing their expression. This effect can be compensated by combining DNMT inhibitors with a demethylating inhibitor (SAM), which causes prometastatic gene-specific methylation and subsequent down-regulation in gene expression without targeting tumour suppressor genes (Chik et al., 2014). Filled (black) circles correspond to methylated Cs; unfilled (white) circles correspond to demethylated Cs.

Concluding remarks

Although 5-azaC and 5-azadC have served a very important role in deciphering the role of DNA hypermethylation in cancer and in providing the proof of principle for DNA demethylation therapy in clinical practice, several important obstacles remain. Firstly, the mechanism of action of 5-azaC in clinical response has to be clarified, as this is essential for dosing, scheduling and patient stratification. We need to identify the patients who will most benefit from 5-azaC/dC therapy. Secondly, the poor response in solid tumours to 5-azaC and 5-azadC requires examining different combinations as well as careful testing of dosing and scheduling. Moreover, testing new DNA methylation inhibitors might provide more effective ways for inhibiting DNA methylation of tumour suppressor genes in solid tumours in clinical practice. Thirdly, cell line data suggest that therapy could be improved by focusing on DNMT1. This calls for investing effort in developing DNMT1-specific inhibitors rather than using 5-azaC/dC, which inhibits all DNMTs resulting in possible activation of genes that could promote cancer. Fourthly, more attention needs to be given to the critical role of hypomethylation in driving cancer and cancer metastasis. There is a need to develop agents that target this process such as SAM, as well as developing more specific DNA demethylation inhibitors. Combining such agents with DNMT1 inhibitors might have synergistic effects on cancer inhibiting both tumour growth and tumour metastasis.

Acknowledgments

D. C. is supported by fellowship from the Israel Cancer Research Foundation.

Glossary

- 5-azaC

5-azacytidine

- 5-azadC

5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- SAH

S-adenosyl-homocysteine

- SAHA

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- SAM

S-adenosyl-methionine

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Table S1 Recent clinical studies with epigenetic drugs.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio A, Weber JS. Review of the clinical experience with 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in solid tumors. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio A, Eads CA, Leong LA, Laird PW, Newman EM, Synold TW, et al. Phase I trial of continuous infusion 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D, Toperoff G, Rosenberg M, Hellman A. Replication timing-related and gene body-specific methylation of active human genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:670–680. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateeq B, Unterberger A, Szyf M, Rabbani SA. Pharmacological inhibition of DNA methylation induces proinvasive and prometastatic genes in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasia. 2008;10:266–278. doi: 10.1593/neo.07947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, Lee JH, LeProust EM, Park IH, et al. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Pai SK, Hirota S, Hosobe S, Takano Y, Saito K, et al. Role of the putative tumor metastasis suppressor gene Drg-1 in breast cancer progression. Oncogene. 2004;23:5675–5681. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubec T, Schubeler D. Genomic patterns and context specific interpretation of DNA methylation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;25C:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin SB, Esteller M, Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Schuebel K, Herman JG. Aberrant patterns of DNA methylation, chromatin formation and gene expression in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:687–692. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya SK, Ramchandani S, Cervoni N, Szyf M. A mammalian protein with specific demethylase activity for mCpG DNA. Nature. 1999a;397:579–583. doi: 10.1038/17533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya SK, Ramchandani S, Cervoni N, Szyf M. A mammalian protein with specific demethylase activity for mCpG DNA [see comments] Nature. 1999b;397:579–583. doi: 10.1038/17533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani N, Brady JJ, Damian M, Sacco A, Corbel SY, Blau HM. Reprogramming towards pluripotency requires AID-dependent DNA demethylation. Nature. 2010;463:1042–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A, Taggart M, Frommer M, Miller OJ, Macleod D. A fraction of the mouse genome that is derived from islands of nonmethylated, CpG-rich DNA. Cell. 1985;40:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattler A, Farnham PJ. Cross-talk between site-specific transcription factors and DNA methylation states. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:34287–34294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.512517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghol N, Suderman M, McArdle W, Racine A, Hallett M, Pembrey M, et al. Associations with early-life socio-economic position in adult DNA methylation. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:62–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick M, Kim JK, Esteve PO, Clark A, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science. 2007;317:1760–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.1147939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron EE, Bachman KE, Myohanen S, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat Genet. 1999;21:103–107. doi: 10.1038/5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni GL. S-adenosylmethionine; a new intermediate formed enzymatically from l-methionine and adenosinetriphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1953;204:417–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O'Donnell MR, DiPersio JF. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:556–561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedar H, Stein R, Gruenbaum Y, Naveh-Many T, Sciaky-Gallili N, Razin A. Effect of DNA methylation on gene expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1983;47(Pt 2):605–609. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervoni N, Szyf M. Demethylase activity is directed by histone acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2001b;276:40778–40787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervoni N, Sang-Beom S, Chakravarti D, Szyf M. A novel regulatory role for Set/TAF-Iß oncoprotein integrating histone hypoacetylation and DNA hypermethylation in transcriptional silencing. J Biol Chem. 2001a;277:25026–25031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Wang KY, Shen CK. DNA 5-methylcytosine demethylation activities of the mammalian DNA methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:9084–9091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MY, Liao WS, Lu Z, Bornmann WG, Hennessey V, Washington MN, et al. Decitabine and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) inhibit growth of ovarian cancer cell lines and xenografts while inducing expression of imprinted tumor suppressor genes, apoptosis, G2/M arrest, and autophagy. Cancer. 2011;117:4424–4438. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RZ, Pettersson U, Beard C, Jackson-Grusby L, Jaenisch R. DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates. Nature. 1998;395:89–93. doi: 10.1038/25779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik F, Szyf M. Effects of specific DNMT gene depletion on cancer cell transformation and breast cancer cell invasion; toward selective DNMT inhibitors. Carcinogenesis. 2011a;32:224–232. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik F, Szyf M. Effects of specific DNMT-gene depletion on cancer cell transformation and breast cancer cell invasion; towards selective DNMT inhibitors. Carcinogenesis. 2011b;32:224–232. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik F, Machnes Z, Szyf M. Synergistic anti-breast cancer effect of a combined treatment with the methyl donor S-adenosyl methionine and the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:138–144. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BF, Karpenko MJ, Liu Z, Aimiuwu J, Villalona-Calero MA, Chan KK, et al. Phase I study of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in combination with valproic acid in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cihak A, Vesela H, Sorm F. Thymidine kinase and polyribosome distribution in regerating rat liver following 5-azacytidine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;166:277–279. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(68)90518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Cao X, Khetani RS, Chen CC, Coon M, Sammak AA, et al. Intronic Non-CG DNA hydroxymethylation and alternative mRNA splicing in honey bees. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:666. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comb M, Goodman HM. CpG methylation inhibits proenkephalin gene expression and binding of the transcription factor AP-2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3975–3982. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortazar D, Kunz C, Selfridge J, Lettieri T, Saito Y, MacDougall E, et al. Embryonic lethal phenotype reveals a function of TDG in maintaining epigenetic stability. Nature. 2011;470:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature09672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortellino S, Xu J, Sannai M, Moore R, Caretti E, Cigliano A, et al. Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell. 2011;146:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Bauer AM, DesBordes C, Zhuang Y, Kim BE, Newton LG, et al. Genistein alters methylation patterns in mice. J Nutr. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2419S–2423S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2419S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessio AC, Szyf M. Epigenetic tete-a-tete: the bilateral relationship between chromatin modifications and DNA methylation. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:463–476. doi: 10.1139/o06-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detich N, Bovenzi V, Szyf M. Valproate induces replication-independent active DNA demethylation. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:27586–27592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detich N, Hamm S, Just G, Knox JD, Szyf M. The methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine inhibits active demethylation of DNA: a candidate novel mechanism for the pharmacological effects of S-adenosylmethionine. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:20812–20820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan S, Pathania R, Ramachandran S, Ananth S, Padia RN, Srinivas SR, et al. Molecular mechanism of SLC5A8 inactivation in breast cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:3920–3935. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01702-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. DNA methylation and cancer therapy: new developments and expectations. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:55–60. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000147383.04709.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi M, Hermann A, Pradhan S, Jeltsch A. The activity of the murine DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 is controlled by interaction of the catalytic domain with the N-terminal part of the enzyme leading to an allosteric activation of the enzyme after binding to methylated DNA. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:1189–1199. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P, Gattermann N, Seymour JF, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Mufti GJ, Duehrsen U, et al. Prolonged survival with improved tolerability in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: azacitidine compared with low dose ara-C. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:244–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatau E, Gonzales FA, Michalowsky LA, Jones PA. DNA methylation in 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine-resistant variants of C3H 10T1/2 C18 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2098–2102. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.10.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J, Glickman JF, Reich NO. Murine DNA cytosine-C5 methyltransferase: pre-steady- and steady-state kinetic analysis with regulatory DNA sequences. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7308–7315. doi: 10.1021/bi9600512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, Burgers WA, Brehm A, Hughes-Davies L, Kouzarides T. DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 associates with histone deacetylase activity. Nat Genet. 2000;24:88–91. doi: 10.1038/71750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuso A, Cavallaro RA, Orru L, Buttarelli FR, Scarpa S. Gene silencing by S-adenosylmethionine in muscle differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfman S, Cohen N, Yearim A, Ast G. DNA-methylation effect on co-transcriptional splicing is dependent on GC-architecture of the exon-intron structure. Genome Res. 2013;23:789–799. doi: 10.1101/gr.143503.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal K, Bai S. DNA methyltransferases as targets for cancer therapy. Drugs Today (Barc) 2007;43:395–422. doi: 10.1358/dot.2007.43.6.1062666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal K, Datta J, Majumder S, Bai S, Kutay H, Motiwala T, et al. 5-Aza-deoxycytidine induces selective degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by a proteasomal pathway that requires the KEN box, bromo-adjacent homology domain, and nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4727–4741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4727-4741.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Glasspool RM, Brown R, Gore ME, Rustin GJ, McNeish IA, Wilson RH, et al. A randomised, phase II trial of the DNA-hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in combination with carboplatin vs carboplatin alone in patients with recurrent, partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1923–1929. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Kramer OH, Schimpf A, Giavara S, et al. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EA, Gore SD. DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:23–30. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Su Y, Zhong C, Ming GL, Song H. Hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine by TET1 promotes Active DNA demethylation in the adult brain. Cell. 2011;145:423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, Shin J, Li H, Xie B, et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci. 2013;17:215–222. doi: 10.1038/nn.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Pakneshan P, Gladu J, Slack A, Szyf M, Rabbani SA. Regulation of DNA methylation in human breast cancer. Effect on the urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene production and tumor invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41571–41579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets GG, van der Kammen RA, Scholtes EH, Collard JG. Induction of invasive and metastatic potential in mouse T-lymphoma cells (BW5147) by treatment with 5-azacytidine. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1990;8:567–577. doi: 10.1007/BF00135878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn NM, Bonney PL, Dhawan D, Jones DR, Balch C, Guo Z, et al. Subcutaneous 5-azacitidine treatment of naturally occurring canine urothelial carcinoma: a novel epigenetic approach to human urothelial carcinoma drug development. J Urol. 2012;187:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham MS, Lee JK, Kim KC. S-adenosyl methionine specifically protects the anticancer effect of 5-FU via DNMTs expression in human A549 lung cancer cells. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:373–378. doi: 10.3892/mco.2012.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm S, Just G, Lacoste N, Moitessier N, Szyf M, Mamer O. On the mechanism of demethylation of 5-methylcytosine in DNA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy ML, Coulter I, Morton SC, Favreau J, Venuturupalli S, Chiappelli F, et al. S-adenosyl-l-methionine for treatment of depression, osteoarthritis, and liver disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2003;64:1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Liu Y, Upadhyay AK, Chang Y, Howerton SB, Vertino PM, et al. Recognition and potential mechanisms for replication and erasure of cytosine hydroxymethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4841–4849. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman A, Chess A. Gene body-specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science. 2007;315:1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1136352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard G, Eiges R, Gaudet F, Jaenisch R, Eden A. Activation and transposition of endogenous retroviral elements in hypomethylation induced tumors in mice. Oncogene. 2007;27:404–408. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain Z, Khan MI, Shahid M, Almajhdi FN. S-adenosylmethionine, a methyl donor, up regulates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in colorectal cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:1106–1118. doi: 10.4238/2013.April.10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamdar NM, Ehrlich KC, Ehrlich M. CpG methylation inhibits binding of several sequence-specific DNA- binding proteins from pea, wheat, soybean and cauliflower. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:111–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00036811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP, Vertino PM, Wu J, Sazawal S, Celano P, Nelkin BD, et al. Increased cytosine DNA-methyltransferase activity during colon cancer progression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1235–1240. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.15.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer LM, Tahiliani M, Rao A, Aravind L. Prediction of novel families of enzymes involved in oxidative and other complex modifications of bases in nucleic acids. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1698–1710. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke J, O'Hagan HM, Zhang W, Vatapalli R, Calmon MF, Danilova L, et al. Frequent inactivation of cysteine dioxygenase type 1 contributes to survival of breast cancer cells and resistance to anthracyclines. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3201–3211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiří Veselý AČ. 5-Azacytidine: mechanism of action and biological effects in mammalian cells. Pharmacol Therapeut. 1978;2:813–840. [Google Scholar]

- Jjingo D, Conley AB, Yi SV, Lunyak VV, Jordan IK. On the presence and role of human gene-body DNA methylation. Oncotarget. 2012;3:462–474. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Taylor SM. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell. 1980;20:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juttermann R, Li E, Jaenisch R. Toxicity of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine to mammalian cells is mediated primarily by covalent trapping of DNA methyltransferase rather than DNA demethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11797–11801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, Wierzbowska A, Mazur G, Mayer J, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2670–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli RM, Zhang Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature. 2013;502:472–479. doi: 10.1038/nature12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuendgen A, Lubbert M. Current status of epigenetic treatment in myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:601–611. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird PW, Jackson-Grusby L, Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Jung WE, Li E, et al. Suppression of intestinal neoplasia by DNA hypomethylation. Cell. 1995;81:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Gueugnon F, Boutin B, Guillot F, Blanquart C, Rogel A, et al. A 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine/valproate combination induces cytotoxic T-cell response against mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1105–1116. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature. 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chiappinelli KB, Guzzetta AA, Easwaran H, Yen RW, Vatapalli R, et al. Immune regulation by low doses of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacitidine in common human epithelial cancers. Oncotarget. 2014;5:587–598. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LH, Olin EJ, Buskirk HH, Reineke LM. Cytotoxicity and mode of action of 5-azacytidine on L1210 leukemia. Cancer Res. 1970;30:2760–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KT, Momparler RL, Rivard GE. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of chemical stability of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. J Pharm Sci. 1981;70:1228–1232. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600701112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner DJ, Wu Y, Haney R, Jacobs BS, Fruehauf JP, Tuthill R, et al. Thrombospondin-1 expression in melanoma is blocked by methylation and targeted reversal by 5-Aza-deoxycytidine suppresses angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, Urich M, Puddifoot CA, Johnson ND, et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science. 2013;341:1237905. doi: 10.1126/science.1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz MC, Dickerson DR, Schmitt M, Groudine M. Intragenic DNA methylation alters chromatin structure and elongation efficiency in mammalian cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1068–1075. doi: 10.1038/nsmb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC, Mato JM. Role of methionine adenosyltransferase and S-adenosylmethionine in alcohol-associated liver cancer. Alcohol. 2005;35:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC, Mato JM. S-adenosylmethionine in liver health, injury, and cancer. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1515–1542. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AR, Szyf M. Expression of antisense to DNA methyltransferase mRNA induces DNA demethylation and inhibits tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 1995b;270:8037–8043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AR, Rouleau J, Szyf M. Regulation of DNA methylation by the Ras signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995a;270:11327–11337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateen S, Raina K, Agarwal C, Chan D, Agarwal R. Silibinin synergizes with histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors in upregulating E-cadherin expression together with inhibition of migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345:206–214. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunakea AK, Chepelev I, Cui K, Zhao K. Intragenic DNA methylation modulates alternative splicing by recruiting MeCP2 to promote exon recognition. Cell Res. 2013;23:1256–1269. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D'Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Sun G, Zhong M, Yu Y, Brewer MA. Anticancer efficacy of cisplatin and trichostatin A or 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine on ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:579–586. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzin J, Lang K, Earle CC, Kerney D, Mallick R. The outcomes and costs of acute myeloid leukemia among the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1597–1603. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikyskova R, Indrova M, Vlkova V, Bieblova J, Simova J, Parackova Z, et al. DNA demethylating agent 5-azacytidine inhibits myeloid-derived suppressor cells induced by tumor growth and cyclophosphamide treatment. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:743–753. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0813435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Sweatt JD. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron. 2007;53:857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza S, Sharma G, Pandya P, Ralhan R. Demethylating agent 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine enhances susceptibility of breast cancer cells to anticancer agents. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;342:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0473-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL. Epigenetic therapy of cancer with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) Semin Oncol. 2005;32:443–451. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, Ayoub J. Potential of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) a potent inhibitor of DNA methylation for therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(Suppl. 4):S111–S115. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, Bouffard DY, Momparler LF, Dionne J, Belanger K, Ayoub J. Pilot phase I-II study on 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:358–368. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, Rossi M, Bouchard J, Vaccaro C, Momparler LF, Bartolucci S. Kinetic interaction of 5-AZA-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-monophosphate and its 5′-triphosphate with deoxycytidylate deaminase. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;25:436–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Takenaga K. Hypomethylation of the metastasis-associated S100A4 gene correlates with gene activation in human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:471–479. doi: 10.1023/a:1006589626307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A. MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell. 1997;88:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Xie S, Li E. Cloning and characterization of a family of novel mammalian DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases [letter] Nat Genet. 1998;19:219–220. doi: 10.1038/890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson L, Forchhammer J. Induction of the metastatic phenotype in a mouse tumor model by 5-azacytidine, and characterization of an antigen associated with metastatic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3389–3393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou JN, Torrisani J, Unterberger A, Provencal N, Shikimi K, Karimi M, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A induces global and gene-specific DNA demethylation in human cancer cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1297–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakneshan P, Szyf M, Farias-Eisner R, Rabbani SA. Reversal of the hypomethylation status of urokinase (uPA) promoter blocks breast cancer growth and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31735–31744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palii SS, Robertson KD. Epigenetic control of tumor suppression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2007;17:295–316. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v17.i4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascale RM, Simile MM, De Miglio MR, Feo F. Chemoprevention of hepatocarcinogenesis: S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Alcohol. 2002;27:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor WA, Aravind L, Rao A. TETonic shift: biological roles of TET proteins in DNA demethylation and transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:341–356. doi: 10.1038/nrm3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra SK, Patra A, Zhao H, Dahiya R. DNA methyltransferase and demethylase in human prostate cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2002;33:163–171. doi: 10.1002/mc.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014;42:D1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. (Database Issue): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiel CJ, Zhang F, Huang EY, Guenther MG, Lazar MA, Klein PS. Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36734–36741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleyer L, Germing U, Sperr WR, Linkesch W, Burgstaller S, Stauder R, et al. Azacitidine in CMML: matched-pair analyses of daily-life patients reveal modest effects on clinical course and survival. Leuk Res. 2014;38:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplineau M, Schnekenburger M, Dufer J, Kosciarz A, Brassart-Pasco S, Antonicelli F, et al. The DNA hypomethylating agent, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, enhances tumor cell invasion through a transcription-dependent modulation of MMP-1 expression in human fibrosarcoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mc.22071. doi: 10.1002/mc.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S, Bacolla A, Wells RD, Roberts RJ. Recombinant human DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase. I. Expression, purification, and comparison of de novo and maintenance methylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33002–33010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quagliana JM, O'Bryan RM, Baker L, Gottlieb J, Morrison FS, Eyre HJ, et al. Phase II study of 5-azacytidine in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama F, Shafiei F, Gluckman PD, Mitchell MD, Lobie PE. Epigenetic regulation of human trophoblastic cell migration and invasion. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5275–5283. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani S, MacLeod AR, Pinard M, von Hofe E, Szyf M. Inhibition of tumorigenesis by a cytosine-DNA, methyltransferase, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:684–689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch TA, Wu X, Zhong X, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP. A human B cell methylome at 100-base pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:671–678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812399106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin A, Cedar H. Distribution of 5-methylcytosine in chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:2725–2728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin A, Riggs AD. DNA methylation and gene function. Science. 1980;210:604–610. doi: 10.1126/science.6254144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roje S. S-adenosyl-l-methionine: beyond the universal methyl group donor. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1686–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SA. Diet and DNA methylation interactions in cancer prevention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;983:197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosty C, Ueki T, Argani P, Jansen M, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Overexpression of S100A4 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas is associated with poor differentiation and DNA hypomethylation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64347-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau J, MacLeod AR, Szyf M. Regulation of the DNA methyltransferase by the Ras-AP-1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1595–1601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samlowski WE, Leachman SA, Wade M, Cassidy P, Porter-Gill P, Busby L, et al. Evaluation of a 7-day continuous intravenous infusion of decitabine: inhibition of promoter-specific and global genomic DNA methylation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3897–3905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Peat J, Burgess H, Rada C, Reik W, Dean W. Active demethylation in mouse zygotes involves cytosine deamination and base excision repair. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6:39–51. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Maehara N, Su GH, Goggins M. Effects of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine on matrix metalloproteinase expression and pancreatic cancer cell invasiveness. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:327–330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Haaf T, Grunert D. 5-Azacytidine-induced undercondensations in human chromosomes. Hum Genet. 1984;67:257–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00291352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrump DS, Fischette MR, Nguyen DM, Zhao M, Li X, Kunst TF, et al. Phase I study of decitabine-mediated gene expression in patients with cancers involving the lungs, esophagus, or pleura. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5777–5785. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shteper PJ, Zcharia E, Ashhab Y, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I, Ben-Yehuda D. Role of promoter methylation in regulation of the mammalian heparanase gene. Oncogene. 2003;22:7737–7749. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukeir N, Pakneshan P, Chen G, Szyf M, Rabbani SA. Alteration of the methylation status of tumor-promoting genes decreases prostate cancer cell invasiveness and tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9202–9210. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack A, Cervoni N, Pinard M, Szyf M. DNA methyltransferase is a downstream effector of cellular transformation triggered by simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10105–10112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorm F, Piskala A, Cihak A, Vesely J. 5-Azacytidine, a new, highly effective cancerostatic. Experientia. 1964;20:202–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02135399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanska B, Huang J, Bhattacharyya B, Suderman M, Hallett M, Han ZG, et al. Definition of the landscape of promoter DNA hypomethylation in liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5891–5903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein R, Razin A, Cedar H. In vitro methylation of the hamster adenine phosphoribosyltransferase gene inhibits its expression in mouse L cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3418–3422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresemann C, Lyko F. Modes of action of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacytidine and decitabine. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:8–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M. DNA methylation properties: consequences for pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M. DNA methylation and demethylation as targets for anticancer therapy. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70:533–549. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M, Theberge J, Bozovic V. Ras induces a general DNA demethylation activity in mouse embryonal P19 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12690–12696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur S, Feng X, Qiao Shi Z, Ganapathy A, Kumar Mishra M, Atadja P, et al. ING1 and 5-azacytidine act synergistically to block breast cancer cell growth. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JH. Genomic imprinting proposed as a surveillance mechanism for chromosome loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:480–482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturelli S, Armeanu S, Pathil A, Hsieh CJ, Weiss TS, Vonthein R, et al. Epigenetic combination therapy as a tumor-selective treatment approach for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;109:2132–2141. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Stambaugh JE, Mastrangelo MJ, Laucius JF, Bellet RE. Phase I study of 5-azacytidine (NSC-102816) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1972;56:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Metter GE, Nealon TF, Keanan JP, Ramirez G, Swaiminathan A, et al. Phase II study of 5-azacytidine in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Westhuyzen J. Methionine metabolism and cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1985;7:179–183. doi: 10.1080/01635588509513852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Issa JP, Herman J, Bassett DE, Jr, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Expression of an exogenous eukaryotic DNA methyltransferase gene induces transformation of NIH 3T3 cells [see comments] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8891–8895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Santi DV. On the mechanism and inhibition of DNA cytosine methyltransferases. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;198:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JI, Hong EP, Castle JC, Crespo-Barreto J, Bowman AB, Rose MF, et al. Regulation of RNA splicing by the methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor methyl-CpG binding protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17551–17558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507856102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zeng P, Xiong J, Liu Z, Berger SL, Merlino G. Epigenetic drugs can stimulate metastasis through enhanced expression of the pro-metastatic Ezrin gene. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Qi F, Cao Y, Zu X, Chen M, Li Z, et al. 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine Enhances Maspin Expression and Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of the Bladder Cancer T24 Cell Line. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28:343–350. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yashiro M, Ohira M, Ren J, Hirakawa K. Synergic antiproliferative effect of DNA methyltransferase inhibitor in combination with anticancer drugs in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:938–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker KE, Riggs AD, Smith SS. Purification of human DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase. J Cell Biochem. 1985;29:337–349. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240290407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Recent clinical studies with epigenetic drugs.