Abstract

Differences in perceptual latency (ΔL) for two stimuli, such as an auditory and a visual stimulus, can be estimated from temporal order judgments (TOJ) and simultaneity judgments (SJ), but previous research has found evidence that ΔL estimated from these tasks do not coincide. Here, using an auditory and a visual stimulus we confirmed this and further show that ΔL as estimated from duration judgments also does not coincide with ΔL estimated from TOJ or SJ. These inconsistencies suggest that each judgment is subject to different processes that bias ΔL in different ways: TOJ might be affected by sensory interactions, a bias associated with the method of single stimuli and an order difficulty bias; SJ by sensory interactions and an asymmetrical criterion bias; duration judgments by an order duration bias.

Keywords: TOJ, SJ, duration, inconsistent, time, perception

1. Introduction

Perceiving a stimulus takes time and this perceptual latency, L, likely depends on the sensory feature. For example, auditory stimuli may be processed faster than visual stimuli. Knowing how much longer it takes to perceive a stimulus A relative to a stimulus B—the difference in perceptual latency, ΔL—may help the project of understanding what kind of neural activity causes perception (Krekelberg & Lappe, 2001; Zeki, 2003).

ΔL is sometimes estimated by subtracting the behavioural response time to stimulus B from the response time to stimulus A (Amano, Johnston, & Nishida, 2007; Aschersleben & Musseler, 1999; Di Luca, Machulla, & Ernst, 2009; Kopinska & Harris, 2004; Navarra, Hartcher-O'Brien, Piazza, & Spence, 2009; Neumann & Niepel, 2004; Nishida & Johnston, 2002; Takei & Nishida, 2010). Response times, however, might reflect speedy decisions that can occur prior to perception or rely on different neural circuits than perception (Neumann & Niepel, 2004).

ΔL is often estimated from other behavioural tasks that are considered to rely more upon perception such as temporal order judgments (TOJ) (Adams & Mamassian, 2004; Arnold, Johnston, & Nishida, 2005; Aschersleben & Musseler, 1999; Barnett-Cowan & Harris, 2009; Bedell, Chung, Ogmen, & Patel, 2003; Di Luca et al., 2009; Johnston, Arnold, & Nishida, 2006; Kanai, Carlson, Verstraten, & Walsh, 2009; Klemm, 1925; Kopinska & Harris, 2004; Lewald & Guski, 2004; Linares & López-Moliner, 2006; Neumann & Niepel, 2004; Sugita & Suzuki, 2003), simultaneity judgments (SJ) (Barnett-Cowan & Harris, 2009; Kanai et al., 2009; Stone et al., 2001) and duration judgments (Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2014). Here, we studied TOJ and SJ because they appear to be the most commonly used for estimating ΔL. We also used duration judgments because, although previously it has rarely been used to estimate ΔL, the large temporal interval that can be used between stimulus A and B should minimize or eliminate the sensory interaction of A and B that may be a problem for the other tasks (see Discussion).

In TOJ (Hirsh & Sherrick, 1961), A and B are presented with different relative timings and observers report which stimulus occurred first. ΔL is estimated as the relative timing for which it is equally likely to report A is first as that B is first.

In SJ (Allan, 1975), A and B are presented with different relative timings and observers report whether they occurred at the same time or not. ΔL is estimated as the relative timing that is most likely to cause an observer to report “simultaneous.”

In duration judgments (Grondin & Rousseau, 1991; Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013), observers compare the duration of an interval delimited by A followed by B (AB) with the duration of an interval delimited by B followed by A (BA). If the perceptual latency of A (LA) is shorter than the perceptual latency of B (LB), then the interval AB should be perceived as lasting longer than BA (Figure 3A; Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013). More specifically, the perceived duration of an interval AB (DAB) of physical duration d might be estimated as

| (1) |

where ΔLBA = LB − LA (Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013).

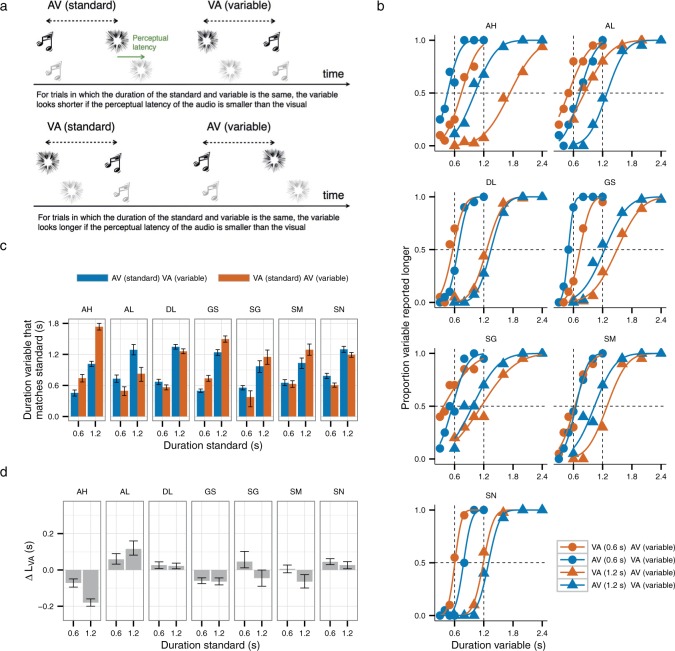

Figure 3.

Duration judgments. (a) Illustration of the two type of trials used. (b) Proportion of trials in which the variable was perceived as lasting longer than the standard for the two types of trials and the two standards. The cumulative normal distributions were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation. (c) Duration variable that matches the standard from (a), PSE. The error bars are the 95% confidence intervals calculated by parametric bootstrap (d) Differences in perceptual latency for auditory and visual stimulation, ΔLVA, calculated as the difference in the PSEs for the two types of trials in (c) divided by 4 (Equation (4)). Positive values indicates longer latency for V. The error bars are the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the upper and lower limits of the distribution of differences of the bootstrapped PSEs in (c) for the two type of trials divided by 4.

Similarly, the perceived duration of a BA interval (DBA) of the same duration might be estimated as

| (2) |

Hence, from Equations (1) and (2) it is possible to estimate ΔLBA using DAB and DBA

| (3) |

A major problem for the estimation of ΔL is that the estimates provided by different tasks often do not coincide. For TOJ and SJ, previous studies have shown that ΔL are inconsistent in that they do not correlate significantly across observers (Love, Petrini, Cheng, & Pollick, 2013; van Eijk, Kohlrausch, Juola, & Van de Par, 2008; Vatakis, Navarra, Soto-Faraco, & Spence, 2008; but see Sanders, Chang, Hiss, Uchanski, & Hullar, 2011). This inconsistency might be related to the different biases that afflict TOJ and SJ (see Discussion).

No previous studies have tested whether the ΔL estimated from SJ or TOJ is consistent with that estimated from duration judgments. Consistency of duration judgments and TOJ might suggest that these methods should be preferred for estimating ΔL (Neumann & Niepel, 2004). Another possibility is that SJ and duration judgments yield consistent estimates. We found, however, that ΔL estimated from duration judgments is not consistent with ΔL estimated from TOJ nor SJ, which suggests that each method is subject to different processes that hinder the estimation of ΔL.

2. Method

Seven people participated. The authors (DL and AH) and GS knew the experimental hypotheses. The tasks of duration judgment, SJ, and TOJ were tested in different sessions. Observers conducted first the duration judgments, then the SJ and finally the TOJ. The sole exception was AH, who conducted some more sessions of duration judgments after the TOJ. For the duration judgments, two standard durations (see below) were tested in different sessions whose order was pseudo-randomized across observers. For each standard, observers completed between 280 and 1,120 trials. For SJ and TOJ, each observer completed 220 trials. The data and code (in R, R Core Team, 2014) to do the statistical analysis and create the figures are available at http://www.dlinares.org.

The visual and auditory stimuli were generated using PsychoPy (Peirce, 2007). Visual stimuli were displayed on a CRT at 100 Hz and auditory stimuli were presented with headphones. Observers fixated a black circle (all guns set to zero) in a grey background (54 cd/m2). The visual event, V, was a colour change of the fixation point to white (108 cd/m2) for 10 ms. The auditory event, A, was a 10 ms white noise burst (70 dB SPL).

For SJ and TOJ, A occurred at a random time between 0.8 and 1.2 s after the onset of the trial and the timing of V relative to A varied according to the method of constant stimuli (ranging from −0.25 to 0.25 s in steps of 0.05 s). SJ and TOJ were run in separate blocks of trials.

For the duration judgments, two intervals were presented on each trial and the observers judged which was longer (see Figure 3a). The first interval (the “standard”) was 0.6 s or 1.2 s in different blocks of trials. The second (the “variable”) was chosen from a range of durations centred on the standard interval's duration (method of constant stimuli; variable intervals for the 0.6 s standard: 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8 s; variable intervals for the 1.2 s standard: 1.0, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0, 2.4 s). The irrelevant “spacing interval” between the judged intervals had a random duration between 0.4 and 0.6 s for the 0.6 s standard, and between 0.8 and 1.2 s for the 1.2 s standard. The time preceding the stimuli on each trial was a random value between 0.4 and 0.6 s for the 0.6 s standard and a random value between 0.8 and 1.2 s for the 1.2 s standard.

3. Results

3.1. Temporal order judgments (TOJ)

Figure 1a shows the proportion of trials in which V (the visual stimulus) was reported to occur before A (the auditory stimulus) as a function of the relative timing between A and V. Many observers informally reported that this task was more difficult than the SJ task and the duration task. The participants in Love et al. (2013) similarly reported that TOJ was more difficult. We found that some observers like GS and DL perform far from perfectly (less than 80% correct) even for very long relative timings, so it appears that the greater difficulty of TOJ is not restricted to when the stimuli occur close in time. To account for this, we fitted cumulative normal curves with an independent lapse rate for each side (see caption of Figure 1).

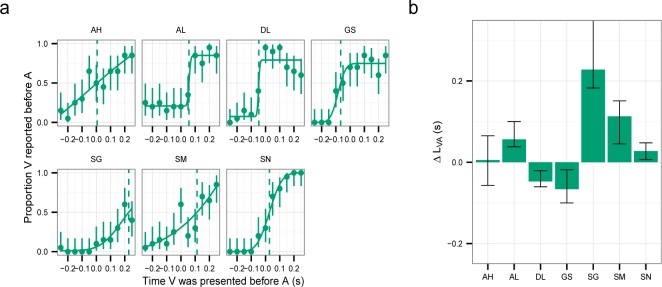

Figure 1.

Temporal order judgments (TOJ). (a) Proportion of V reported before A as a function of the relative timing between A and V. The error bars are the 95% confidence intervals calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method. The four-parameter (mean, standard deviation, lower asymptote and upper asymptote) cumulative normal distributions were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation (Knoblauch & Maloney, 2012). (b) ΔLVA estimated as the timing for which half of the trials the observer reported V before A in (a). Positive values indicates longer latency for V. The error bars are the 95% parametric bootstrap confidence intervals (Kingdom & Prins, 2010; we use 1,000 samples for all the bootstrap calculations in the paper).

To estimate ΔLVA from the fitted curves, we extracted the timing for which in half of the trials the observer reported V before A. This ΔLVA is positive for some observers and negative for others, which is statistically reliable as for most observers the confidence intervals do not overlap zero (Figure 1b). This is consistent with previous findings (Boenke, Deliano, & Ohm, 2009; Love et al., 2013; van Eijk et al., 2008). Across observers, the average ΔLVA was 45 ms (not significantly different from 0, one sample t-test: t(6) = 1.89, p = .28).

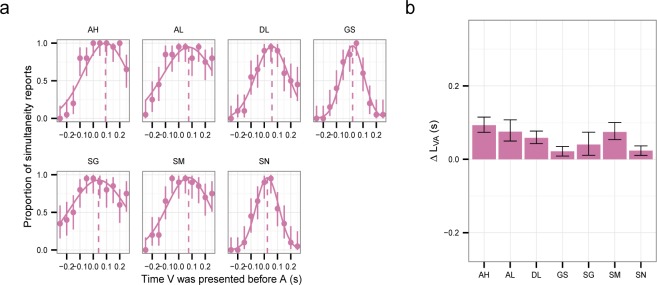

3.2. Simultaneity judgments (SJ)

Figure 2a shows the proportion of simultaneous reports as a function of the relative timing between A and V. We fitted a normal curve to these proportions and took its center as ΔLVA (see caption of Figure 2). ΔLVA was positive for all observers (their confidence intervals do not include zero, Figure 1b). This suggests faster perception of A relative to V and is consistent with the findings of previous studies that most observers' ΔLVA is positive (Arrighi, Alais, & Burr, 2006; Love et al., 2013; Stone et al., 2001; van Eijk et al., 2008; Zampini, Guest, Shore, & Spence, 2005;). Across observers, the average ΔLVA was 55 ms (significantly different from 0, one sample t-test: t(6) = 5.31, p = .002).

Figure 2.

Simultaneity judgments (SJ). (a) Proportion of simultaneity reports. The error bars are the 95% confidence intervals calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method. The three-parameter (amplitude, mean and standard deviation) normal distributions were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation. (b) ΔLVA estimated as the mean of the fitted distribution in (a). Positive values indicates longer latency for V. The error bars are the 95% bootstrap parametric confidence intervals.

3.3. Duration judgments

In each trial, the observers decided which of two intervals bounded by A and V seemed longer (Figure 3a). The order of presentation of A and V was different in two distinct trial types. In the AVVA type of trial, the first interval was a 0.6 s “standard”: A was always followed by V (standard AV) after 0.6 s. The second interval was V followed by A after a variable amount of time (variable VA). In the VAAV type of trial, the first interval was a standard of 0.6 s in which V was followed by A (standard VA) and the second interval was defined by A followed by V after a variable amount of time (variable AV). Thus, the standard was always presented before the variable. The AVVA and VAAV trial types were presented in random order within each session.

Comparison of the PSEs for the two trial types allows estimation of ΔLVA, as explained in the Introduction. The difference in perceptual latency between visual and auditory stimulus, ΔLVA, should not depend on the duration of the interval demarcated by the two stimuli, d (Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013), which here is formalized in Equation (3). To test this, in different blocks we used two different durations of the standard, 0.6 s and 1.2 s.

Figure 3b shows, for each observer and standard, the proportion of trials in which the variable interval was perceived to last longer than the standard for AVVA and VAAV trials. Figure 3c shows for AVVA and VAAV trials the durations of the variable intervals that match the standards. These durations are the points of subjective equality or PSEs, estimated by fitting cumulative normal curves to the data in Figure 3b and taking from these fits the duration of the variable intervals that were reported longer than the standards in half of the trials.

Figure 3d shows the estimated ΔLVA values. We did not estimate ΔLVA by applying Equation (3) directly to the PSEs in Figure 3c because the equations in the Introduction assume that perceived duration is measured using a “neutral” variable interval (Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013). Instead of using neutral variable intervals, we used variable intervals in which the order of A and V was reversed relative to the standards because this yields twice the expected effect, providing more power to reveal differences in the perceived duration between AV and VA intervals. Taking into account the use of reversed variable intervals when considering Equations (1), (2) and (3) yields the following equations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Hence, we estimated ΔLVA by subtracting the PSEs shown in Figure 3c and dividing them by 4.

Before discussing the ΔLVA values, we should point out that, according to Equations (4) and (5), the deviation of the PSE for AVVA relative to the duration of the standard (DAV − d) and the deviation of the duration of the standard relative to the PSE for VAAV (d − DVA) should be equal. These quantities, however, were not equal for 8 of the 14 samples (7 observers × 2 standards), according to a statistical test. The statistical test was calculation of the 95% confidence intervals of (DAV − d) − (d − DVA) for each bootstrapped within-subject PSE sample and checking whether it contained zero. Between-subjects statistics support the same conclusion for the population generally—that the deviation is asymmetric. This was a one-sample t-test using the absolute values of (DAV − d) − (d − DVA) calculated for each observer. This difference in shift of the perceived duration relative to d was statistically significant for the 1.2 s standard (t(6) = 5.50, p = .002) indicating asymmetry, and marginally so for the 0.6 s standard (t(6) = 2.40, p = .05).

The asymmetric shift could be caused by a bias to perceive the first interval as shorter or as longer than the second interval (time order error, Hellström, 1985). To take into account this effect, one can consider d in Equations (4) and (5) not as the physical interval but the interval plus a constant term corresponding to shortening or lengthening. Fortunately, because Equation (6) is obtained by subtracting Equations (4) and (5), thus removing d, the shortening or lengthening of the first interval should not affect the calculation of ΔL.

Figure 3d shows the estimated ΔLVA for the 0.6 and 1.2 s standards. For each observer, the sign of ΔLVA was consistent across standards, that is, for any observer ΔLVA was never significantly positive for one of the standards and significantly negative for the other (confidence intervals in Figure 3d). Furthermore, the estimated ΔLVA for the two standards correlated across observers: Pearson's correlation, r(5) = .82, p = .02, 95% bootstrap CI = (.43, .98). Across observers, ΔLVA also was not significantly different for the 0.6 s and 1.2 s standards (paired t-test, t(6) = 1.55, p = 0.17). These results seem consistent with Equation (3). They are also consistent with a recent study finding no effect of the standard's duration, although that study did not examine the issue as closely because the data were pooled across observers before conducting the statistical analysis (Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013).

At the individual observer level, however, the data do not support the consistency across standards. For four of the seven observers, the estimated ΔLVA for the 0.6 s and the 1.2 s standards were different on the conservative test (p < .006) of non-overlap of the confidence intervals (Knol, Pestman, & Grobbee, 2011), which suggests that ΔLVA estimates are inconsistent, even here where the task (duration judgments) was the same for the two conditions, and only the magnitude of the interval differed.

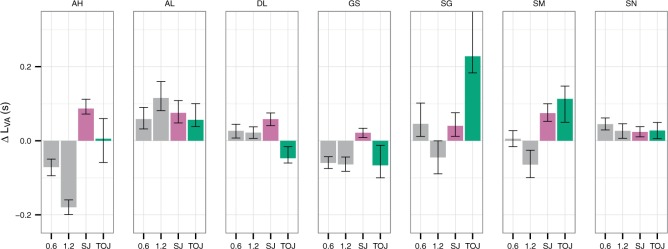

3.4. Comparison across tasks

Figure 4 compares the ΔLVA estimated by the different methods for each observer. Just as previous studies have found (Love et al., 2013; van Eijk et al., 2008; Vatakis et al., 2008; but see Sanders et al., 2011), ΔLVA estimated from TOJ and SJ did not correlate across observers: r(5) = .078, p = .87, 95% CI = (−.81,.87). At the individual level, for four of the seven observers the estimated ΔLVA from TOJ and SJ were different as indicated by the non-overlap of the confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Replot of the estimated ΔLVA from Figures 1d, 2b and 3b.

For duration judgments, the ΔLVA correlated neither with the ΔLVA from TOJ nor with that of SJ: duration for 0.6 s standard vs TOJ, r(5) = .49, p = .26, CI = (−.09,.89); duration for 0.6 s standard vs SJ, r(5) = −.16, p = .73, CI = (−.93,.82); duration for 1.2 s standard vs TOJ, r = .0086, p = .99, CI = (−.80,.68); duration for 1.2 s standard vs SJ, r(5) = −.24, p = .61, 95% CI = (−.92, .87). At the individual level—judging by the non-overlap of the confidence intervals—for four of the seven observers ΔLVA from the 0.6 s standard and TOJ were different; for four of the seven observers ΔLVA from the 0.6 s standard and SJ were different; for four of the seven observers ΔLVA from the 1.2 s standard and TOJ were different; for five of the seven observers ΔLVA from the 1.2 s standard and SJ were different.

Although ΔLVA for the two standards correlated across observers, the lack of correlation for the other comparison might not be very informative because our study did not include many participants. We collected data for a small sample because we were interested in the consistency of ΔLVA at individual level. Our results reveal strong inconsistencies in more than half of the observers.

Future studies using larger samples of participants might establish which tasks produce estimates of ΔLVA that are less inconsistent. Larger samples could also reveal which tasks produce estimates of ΔLVA that are less variable across participants.

4. Discussion

Using an auditory and a visual stimulus, we showed that ΔL estimated from SJ and TOJ are inconsistent, which accords with previous studies (Love et al., 2013; van Eijk et al., 2008; Vatakis et al., 2008; but see Sanders et al., 2011) and found that ΔL estimated from duration judgments is consistent with neither TOJ nor SJ. Given these inconsistencies, it is difficult to know which task is best for estimating ΔL. In Table 1, we offer a tentative list of the possible problems associated with using each task to estimate ΔL. We discuss these problems below.

Table 1. Problems estimating ΔL. “Yes” indicates that the task is likely affected by the problem.

| Problem | TOJ | SJ | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory interactions | Yes | Yes | No |

| Method of single stimuli | Yes | No | No |

| Temporal order difficulty | Yes | No | No |

| Asymmetric criterion | No | Yes | No |

| Duration order | No | No | Yes |

4.1. Problems estimating ΔL from TOJ

Estimating ΔL from TOJ may be affected by three problems. First, sensory interactions: in TOJ, the stimuli are presented close in time and that can affect the response of sensory neurons to each (e.g. temporal principle in multisensory processes, Meredith, Nemitz, & Stein, 1987), altering their neural latencies (e.g. Rowland, Quessy, Stanford, & Stein, 2007). Thus, the perceptual latency of A presented alone and the perceptual latency of A when presented near V could be different. For example, when A and V are presented close in time, attention might be allocated differently to A and V. Given that attending to a stimulus can reduce its neural latency by a few milliseconds (Galashan, Saßen, Kreiter, & Wegener, 2013; Sundberg, Mitchell, Gawne, & Reynolds, 2012), the different allocation of attention might introduce differences in perceptual latency—an effect called prior entry (Spence & Parise, 2010).

The second problem is a bias associated generally with the method of single stimulus or comparative judgments—a popular method for measuring appearance (Anton-Erxleben, Abrams, & Carrasco, 2010; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2013). TOJ is an instance of the method of single stimulus and as such its estimates may be contaminated by a response bias (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2010; Arnold et al., 2005; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2013; Jazayeri & Movshon, 2007; Morgan, Dillenburger, Raphael, & Solomon, 2012; Nicholls, Lew, Loetscher, & Yates, 2011; Schneider & Bavelier, 2003; Shore, Spence, & Klein, 2001; Yarrow, Jahn, Durant, & Arnold, 2011). This bias is particularly an issue for temporal asynchronies near the PSE, where the observer might frequently feel that she does not have an answer, but because she needs to respond, she ends up favouring one of the responses or response buttons.

Favouring one response button means that under uncertainty the participant might have a preference, for example, for the button that she presses with the index finger or with the dominant hand instead of choosing between the buttons completely at random.

Favouring one response might mean, for example, choosing rightward direction in a leftward/rightward motion discrimination task (Morgan et al., 2012), or the auditory stimulus in a TOJ task. The reasons for choosing one response over the other might not be obvious and different observers might have different preferences. In other cases, the bias might be fairly consistent across observers. For example, in a TOJ task, observers might report that attended stimuli come earlier when they are uncertain about the response. Indeed, it is possible that this bias is the major contribution to the prior entry effect (Matthews, Welch, Festa, & Clement, 2013; Reeves & Sperling 1986; Shore et al., 2001; Schneider & Bavelier, 2003; Spence & Parise, 2010). A response could also be favoured depending on how the stimuli group responds. When three stimuli are presented during a brief interval, for example, the reported order of the last two might depend on the similarity with the first one (Albertazzi, 1999; Holcombe, in press; Koenderink, Richards, & Doorn, 2012; Sinico, 1999).

The third problem is a bias associated with a difficulty ordering events in time. In the method of single stimuli for spatial tasks, such as motion discrimination, most observers give the correct response for stimuli relatively far from the PSE, e.g., they respond “rightward” close to 100% of trials if the motion signal is strongly to the right (e.g. Selen, Shadlen, & Wolpert, 2012). For TOJ however, our observers, like observers in previous studies (Love et al., 2013; Petrini, Holt, & Pollick, 2010; Zampini, Shore, & Spence, 2003), have numerous “lapses” even for relatively large temporal separation of the two stimuli. This poor performance is consistent with the data of our observers and observers in previous studies (e.g. Love et al, 2013) reporting that TOJ was a difficult task, more so than SJ. The difficulty might be related to a cognitive temporal bottleneck that limits mapping the two stimuli to their identity (Yamamoto & Kitazawa, 2001). That is, not having enough time to name each stimulus before the next one is perceived can leave one unable to do the task. Depending on the curve used to fit the data (García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012), the numerous lapses far from the PSE may contaminate the estimation of the PSE (García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012), sometimes even precluding its estimation (Love et al., 2013; Petrini et al., 2010; Zampini et al., 2003).

4.2. Problems estimating ΔL from SJ

Given that in SJ, like in TOJ, stimuli are presented close in time, sensory interactions might also afflict SJ. SJ is an instance of the method of equality judgments that measure appearance (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2010; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012). In equality judgments, the bias associated with the method of single stimuli should not occur because favouring one of the responses or response-buttons should change the height of the fitted curve but should not shift its central tendency, the PSE (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2010; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012; Schneider & Bavelier, 2003).

Equality judgments, however, might be affected by an asymmetrical criterion bias by which the probability to report “equal” or “simultaneous” is different for stimuli smaller and larger than the PSE (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2010; Yarrow et al., 2011). For SJ, this bias might reflect an asymmetrical criterion to perceive two stimuli as related. It has been suggested that for auditory and visual stimuli, observers perceive auditory following visual to be more likely to be related than the reverse order, possibly because the former is more common in the environment (Dixon & Spitz, 1980).

Unfortunately, observers sometimes report not having a clear sense of whether two stimuli were simultaneous (Hirsh & Fraisse, 1964; Klemm, 1925). Especially in such conditions of uncertainty, judgments may instead be based on perceived relatedness, which can have an asymmetrical criterion (Welch & Warren, 1980). Indeed, SJ is often considered a measure of perceptual integration that depends on other things as well as ΔL (Arrighi, Alais, & Burr, 2006; Love et al., 2013; Powers, Hillock, & Wallace, 2009; Sanders et al., 2011; van Eijk et al., 2008; Zampini et al., 2005;).

Consistent with the hypothesis of an asymmetrical criterion that favours judging simultaneity for auditory stimuli occurring after visual stimuli, three recent studies suggest that perceived simultaneity is easily malleable for the situation in which A follows V but not for the situation in which V follows A. The first study found that short training on SJ for A and V with feedback reduces “simultaneity” reports for A following V, but not for V following A (Powers et al., 2009). The second study reported that video game players report fewer “simultaneous” responses when A follows V than non-video game players, but video game and non-video game players report “simultaneous” equally when V follows A (Donohue, Woldorff, & Mitroff, 2010). The third found that fast adaptation to temporal relationships occurs when A follows V, but not when V follows A (van der Burg, Cass, & Alais, 2013). It is possible, however, that these changes are not just decisional but reflect actual changes in perceptual latency.

To try to reconcile the differing estimates of ΔL from TOJ and SJ, the bias associated with the method of single stimuli has been modeled recently by García-Pérez and Alcalá-Quintana (Alcalá-Quintana & García-Pérez, 2013; García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012), but when we did a simple Pearson-product correlation of their estimates of ΔL for TOJ and SJ, we found that ΔL did not correlate across observers (r(9) = .23, p = .50; table 1 of the Appendix 2 in García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012). The problem might be that their model does not incorporate any bias associated with the difficulty to order events for TOJ nor the asymmetrical criterion bias for SJ. The former might be easy to incorporate in the form of lapses (García-Pérez & Alcalá-Quintana, 2012), but not the latter given that it requires knowledge about how observers associate relatedness to events.

4.3. Problems estimating ΔL from duration judgments

Because the stimuli in the duration task can be presented far apart in time (as they were here), the duration task may avoid the problem of sensory interactions and also the bias associated with temporal order difficulty.

We measured duration judgments using a two-interval forced choice method. In principle, this method should not be affected by the bias associated with the method of single stimuli. Unfortunately, however, we presented the standard interval always first, and hence, when observers reported shorter or longer for the second interval, they were effectively prone to the same bias as that with the method of single stimuli. The bias could be avoided, if the order of presentation of the standard is randomized.

Another bias that may apply only to the duration task is something we refer to as the duration order bias (Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013). The derivation of Equation 3 assumes than the order of presentation of the stimuli that delimit the time interval only affects the perceptual latency of the onset and offset of the interval and not the encoding of duration per se (Ivry & Schlerf, 2008; Kanai & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer, Di Luca & Ernst, 2013). Under this assumption, ΔL should not depend on the duration of the interval, but instead we found that it does, which suggests that the order of presentation of the stimuli affects the encoding of duration per se and that duration judgments are problematic to estimate ΔL. Such a duration order bias might occur if, for example, attention is prompted differently at the interval onset by A and V (see Discussion in Kanai & Watanabe, 2006) given that attention has been shown to influence perceived duration (Tse, Intriligator, Rivest, & Cavanagh, 2004).

5. Conclusions

The inconsistent estimates of ΔL for TOJ, SJ and duration judgments suggest that these tasks are affected by partially distinct sets of biases. Hence, when researchers use only one of these tasks to assess the effect on ΔL of some manipulation—such as attention (Spence & Parise, 2010), temporal context (Chen & Vroomen, 2013; Koenderink et al., 2012) or adaptation (Fujisaki, Shimojo, Kashino, & Nishida, 2004)—any significant effect should be attributed to changes in ΔL only if one is confident that the biases did not change.

To evaluate the merits of different tasks in the estimation of ΔL, one might not only consider the consistencies of ΔL across tasks, but also the consistency of ΔL for an individual across different moments in time. This has not been done extensively, but for SJ, previous results suggest that the estimated ΔL is stable (Stone et al., 2001).

Apart from TOJ, SJ and duration judgments, other tasks can also be used to estimate perceptual latencies. Observers might be asked to report the location of a moving object at the time of an event (Haggard, Clark, & Kalogeras, 2002; Kanai, Sheth, Verstraten, & Shimojo, 2007; Libet, Gleason, Wright, & Pearl, 1983; Linares, Holcombe, & White, 2009; Wundt, 1883) or synchronize a motor action with a sensory event (Aschersleben & Musseler, 1999; Linares et al., 2009; Nishida & Johnston, 2002; Repp & Su, 2013; White, Linares, & Holcombe, 2008). There are also variations of the duration task in which participants attempt to press a button for the same duration as a previous sensory event (Jazayeri & Shadlen, 2010), or judge whether an event occurred exactly at the midpoint of an interval (Burr, Banks, & Morrone, 2009). Differences in perceptual latencies have also been estimated by asking participants to determine the pairing of two alternating features (Clifford, Arnold, & Pearson, 2003; Moutoussis & Zeki, 1997), although the notion that the best feature timing reflects the difference in perceptual latency has been questioned (Holcombe & Cavanagh, 2008; Holcombe, 2009; but see Moutoussis, 2012; Nishida & Johnston, 2002). The consistency of latencies inferred from these tasks with those from others is under-studied.

To provide stronger support for a conclusion that a manipulation affected ΔL rather than just the biases, researchers should consider using multiple tasks. If the perceptual latency estimates from all tasks support the same conclusion regarding a change in ΔL, the conclusion is more secure. After at least some manipulations, however, the changes in latencies inferred from different tasks disagree (e.g. Schneider & Bavelier, 2003; Vatakis et al., 2008), suggesting that change in biases are sometimes the cause of apparent ΔL shifts. More work should be done to elucidate the nature and malleability of these biases.

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Lars Boenke, Shin'ya Nishida, Warrick Roseboom and Gene Stoner for helpful discussions.

Biography

Daniel Linares received a degree in physics and a PhD in psychology from the University of Barcelona. Now he is a postdoc at the Laboratoire Psychologie de la Perception in the University Paris Descartes. He studies the perception of time, motion and position of moving objects.

Daniel Linares received a degree in physics and a PhD in psychology from the University of Barcelona. Now he is a postdoc at the Laboratoire Psychologie de la Perception in the University Paris Descartes. He studies the perception of time, motion and position of moving objects.

Alex Holcombe received degrees in cognitive science and psychology from the University of Virginia in 1995, and in 2000 a PhD in psychology from Harvard, working with Patrick Cavanagh. Until 2003, he was an NIH NRSA postdoc at UCSD with Don MacLeod and Hal Pashler, and subsequently took a lectureship at Cardiff University in Wales. He moved from Old South Wales to New South Wales in 2006, where he is at the University of Sydney. He previously held an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship and now is Associate Professor of Psychology and co-director of the university's Centre for Time. He studies temporal limits on perception as a way to understand what happens when perception meets cognition.

Alex Holcombe received degrees in cognitive science and psychology from the University of Virginia in 1995, and in 2000 a PhD in psychology from Harvard, working with Patrick Cavanagh. Until 2003, he was an NIH NRSA postdoc at UCSD with Don MacLeod and Hal Pashler, and subsequently took a lectureship at Cardiff University in Wales. He moved from Old South Wales to New South Wales in 2006, where he is at the University of Sydney. He previously held an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship and now is Associate Professor of Psychology and co-director of the university's Centre for Time. He studies temporal limits on perception as a way to understand what happens when perception meets cognition.

Contributor Information

Daniel Linares, Laboratoire Psychologie de la Perception, Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France; e-mail: danilinares@gmail.com.

Alex O. Holcombe, School of Psychology, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; e-mail: alex.holcombe@sydney.edu.au

References

- Adams W. J., Mamassian P. The effects of task and saliency on latencies for colour and motion processing. Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences. 2004;271(1535):139–146. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertazzi L. The time of presentness. A chapter in positivistic and descriptive psychology. Axiomathes. 1999;10(1):49–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02681816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalá-Quintana R., García-Pérez M. A. Fitting model-based psychometric functions to simultaneity and temporal-order judgment data: MATLAB and R routines. Behavior Research Methods. 2013;45(4):972–998. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan L. G. The relationship between judgments of successiveness. Perception and Psychophysics. 1975;18(1):29–36. doi: 10.3758/BF03199363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amano K., Johnston A., Nishida S. Two mechanisms underlying the effect of angle of motion direction change on colour-motion asynchrony. Vision Research. 2007;47(5):687–705. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton-Erxleben K., Abrams J., Carrasco M. Evaluating comparative and equality judgments in contrast perception: Attention alters appearance. Journal of Vision. 2010;10(11):6–1-22. doi: 10.1167/10.11.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D. H., Johnston A., Nishida S. Timing sight and sound. Vision Research. 2005;45(10):1275–1284. doi: 10.1167/13.12.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi R., Alais D., Burr D. Perceptual synchrony of audiovisual streams for natural and artificial motion sequences. Journal of Vision. 2006;6(3):260–268. doi: 10.1167/6.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschersleben G., Müsseler J. Dissociations in the timing of stationary and moving stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1999;25(6):1709–1720. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.25.6.1709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett-Cowan M., Harris L. R. Perceived timing of vestibular stimulation relative to touch, light and sound. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;198(2–3):221–231. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell H. E., Chung S. T. L., Ogmen H., Patel S. S. Color and motion: Which is the tortoise and which is the hare? Vision Research. 2003;43(23):2403–2412. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boenke L. T., Deliano M., Ohl F. W. Stimulus duration influences perceived simultaneity in audiovisual temporal-order judgment. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;198(2–3):233–244. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1917-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D., Banks M. S., Morrone M. C. Auditory dominance over vision in the perception of interval duration. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;198(1):49–57. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Vroomen J. Intersensory binding across space and time: A tutorial review. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2013;75(5):790–811. doi: 10.3758/s13414-013-0475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford C. W. G., Arnold D. H., Pearson J. A paradox of temporal perception revealed by a stimulus oscillating in colour and orientation. Vision Research. 2003;43(21):2245–2253. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(03)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Luca M., Machulla T. K., Ernst M. O. Recalibration of multisensory simultaneity: Cross-modal transfer coincides with a change in perceptual latency. Journal of Vision. 2009;9(12):7–1-16. doi: 10.1167/9.12.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon N. F., Spitz L. The detection of auditory visual desynchrony. Perception. 1980;9(6):719–721. doi: 10.1068/p090719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue S. E., Woldorff M. G., Mitroff S. R. Video game players show more precise multisensory temporal processing abilities. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2010;72(4):1120–1129. doi: 10.1167/9.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki W., Shimojo S., Kashino M., Nishida S. Recalibration of audiovisual simultaneity. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(7):773–778. doi: 10.1038/nn1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galashan F. O., Saßen H. C., Kreiter A. K., Wegener D. Monkey area MT latencies to speed changes depend on attention and correlate with behavioral reaction times. Neuron. 2013;78(4):740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez M. A., Alcalá-Quintana R. On the discrepant results in synchrony judgment and temporal-order judgment tasks: Quantitative model. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2012;19(5):820–846. doi: 10.3758/PP.70.8.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez M. A., Alcalá-Quintana R. Shifts of the psychometric function: Distinguishing bias from perceptual effects. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2013;66(2):319–337. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2012.708761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin S., Rousseau R. Judging the relative duration of multimodal short empty time intervals. Perception and Psychophysics. 1991;49(3):245–256. doi: 10.3758/BF03214309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P., Clark S., Kalogeras J. Voluntary action and conscious awareness. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(4):382–385. doi: 10.1038/nn827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström Å. The time-order error and its relatives: Mirrors of cognitive processes in comparing. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97(1):35–61. doi: 10.1037/h0081647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh I. J., Sherrick C. E. Perceived order in different sense modalities. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1961;62:423–432. doi: 10.1037/h0045283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh I. J., Fraisse P. Simultanéité et succession de stimuli hétérogènes. L'Année Psychologique. 1964. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holcombe A. O. In: The temporal organisation of perception. The Oxford handbook of percpetual organisation. Wagemans J., editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe A.O. Temporal binding favors the early phase of color changes, but not of motion changes, yielding the color-motion asynchrony illusion. Visual Cognition. 2009;17(1–2):232–253. doi: 10.1080/13506280802340653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe A. O., Cavanagh P. Independent, synchronous access to color and motion features. Cognition. 2008;107(2):552–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivry R. B., Schlerf J. E. Dedicated and intrinsic models of time perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12(7):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri M., Movshon J. A. A new perceptual illusion reveals mechanisms of sensory decoding. Nature. 2007;446(7138):912–915. doi: 10.1038/nature05739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri M., Shadlen M. N. Temporal context calibrates interval timing. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(8):1020–1026. doi: 10.1038/nn.2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston A., Arnold D. H., Nishida S. Spatially localized distortions of event time. Current Biology. 2006;16(5):472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R., Carlson T. A., Verstraten F. A. J., Walsh V. Perceived timing of new objects and feature changes. Journal of Vision. 2009;9(7):5–1-13. doi: 10.1167/9.7.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R., Sheth B. R., Verstraten F. A. J., Shimojo S. Dynamic perceptual changes in audiovisual simultaneity. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12):e1253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R., Watanabe M. Visual onset expands subjective time. Perception and Psychophysics. 2006;68(7):1113–1123. doi: 10.3758/BF03193714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom F. A. A., Prins N. Psychophysics: A practical introduction. Academic Press: An imprint of Elsevier, London; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm O. Über die Wirksamkeit kleinster Zeitunterschiede auf dem Gebiete des Tastsinns. Archiv fur die gesamte Psychologie. 1925;50:205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch K., Maloney L. T. Modeling Psychophysical Data in R. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Knol M. J., Pestman W. R., Grobbee D. E. The (mis)use of overlap of confidence intervals to assess effect modification. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;26(4):253–254. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9563-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenderink J., Richards W., van Doorn A. J. Space-time disarray and visual awareness. i-Perception. 2012;3(3):159–165. doi: 10.1068/i0490sas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopinska A., Harris L. R. Simultaneity constancy. Perception. 2004;33(9):1049–1060. doi: 10.1068/p5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krekelberg B., Lappe M. Neuronal latencies and the position of moving objects. Trends in Neurosciences. 2001;24(6):335–339. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewald J., Guski R. Auditory-visual temporal integration as a function of distance: No compensation for sound-transmission time in human perception. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;357(2):119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B., Gleason C. A., Wright E. W., Pearl D. K. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain. 1983;106:623–642. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares D., Holcombe A. O., White A. L. Where is the moving object now? Judgments of instantaneous position show poor temporal precision (SD 5 70 ms) Journal of Vision. 2009;9(13):9–1-14. doi: 10.1167/9.13.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares D., López-Moliner J. Perceptual asynchrony between color and motion with a single direction change. Journal of Vision. 2006;6(9):974–981. doi: 10.1167/6.9.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love S. A., Petrini K., Cheng A., Pollick F. E. A Psychophysical Investigation of differences between synchrony and temporal order judgments. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews N., Welch L., Festa E., Clement A. Remapping time across space. Journal of Vision. 2013;13(8):2–1-15. doi: 10.1167/13.8.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. M., Di Luca M., Ernst M. O. Duration perception in crossmodally-defined intervals. Acta Psychologica. 2014;147:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith M. A., Nemitz J. W., Stein B. E. Determinants of multisensory integration in superior colliculus neurons. I. Temporal factors. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7(10):3215–3229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03215.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutoussis K. Asynchrony in visual consciousness and the possible involvement of attention. Front Psychology. 2012;3:314. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutoussis K., Zeki S. A direct demonstration of perceptual asynchrony in vision. Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences. 1997;264(1380):393–399. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Dillenburger B., Raphael S., Solomon J. A. Observers can voluntarily shift their psychometric functions without losing sensitivity. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2012;74(1):185–193. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0222-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarra J., Hartcher-O'Brien J., Piazza E., Spence C. Adaptation to audiovisual asynchrony modulates the speeded detection of sound. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(23):9169–9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810486106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann O., Niepel M. In: Timing of “Perception” and Perception of “Time”. Psychophysics beyond sensation: Laws and invariants of human cognition. Kaernbach C., Schroger E., Muller H., editors. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls M. E. R., Lew M., Loetscher T., Yates M. J. The importance of response type to the relationship between temporal order and numerical magnitude. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2011;73(5):1604–1613. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S., Johnston A. Marker correspondence, not processing latency, determines temporal binding of visual attributes. Current Biology. 2002;12(5):359–368. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00698-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce J. W. Psychophysics software in Python. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;162(1–2):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrini K., Holt S. P., Pollick F. Expertise with multisensory events eliminates the effect of biological motion rotation on audiovisual synchrony perception. Journal of Vision. 2010;10(5):2. doi: 10.1167/10.5.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers A. R., Hillock A. R., Wallace M. T. Perceptual training narrows the temporal window of multisensory binding. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(39):12265–12274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A., Sperling G. Attention gating in short-term visual memory. Psychological Review. 1986;93:180–206. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repp B. H., Su Y. H. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012) Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2013;20:403–452. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B. A., Quessy S., Stanford T. R., Stein B. E. Multisensory integration shortens physiological response latencies. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(22):5879–5884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4986-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M. C., Chang N.-Y. N., Hiss M. M., Uchanski R. M., Hullar T. E. Temporal binding of auditory and rotational stimuli. Experimental Brain Research. 2011;210(3–4):539–547. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selen L. P. J., Shadlen M. N., Wolpert D. M. Deliberation in the motor system: Reflex gains track evolving evidence leading to a decision. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(7):2276–2286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5273-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K. A., Bavelier D. Components of visual prior entry. Cognitive Psychology. 2003;47(4):333–366. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0285(03)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore D. I., Spence C., Klein R. M. Visual prior entry. Psychological Science. 2001;12(3):205–212. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinico M. Benussi and the history of temporal displacement. Axiomathes. 1999;10(1–3):75–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02681817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spence C., Parise C. Prior-entry: A review. Consciousness and Cognition. 2010;19(1):364–379. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J. V., Hunkin N. M., Porrill J., Wood R., Keeler V., Beanland M., Porter N. R. When is now? Perception of simultaneity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2001;268(1462):31–38. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y., Suzuki Y. Audiovisual perception: Implicit estimation of sound-arrival time. Nature. 2003;421(6926):911. doi: 10.1038/421911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg K. A., Mitchell J. F., Gawne T. J., Reynolds J. H. Attention influences single unit and local field potential response latencies in visual cortical area V4. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(45):16040–16050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0489-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei S., Nishida S. Perceptual ambiguity of bistable visual stimuli causes no or little increase in perceptual latency. Journal of Vision. 2010;10(4):1–15. doi: 10.1167/10.4.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse P. U., Intriligator J., Rivest J., Cavanagh P. Attention and the subjective expansion of time. Perception and Psychophysics. 2004;66(7):1171–1189. doi: 10.3758/BF03196844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burg E., Alais D., Cass J. Rapid recalibration to audiovisual asynchrony. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(37):14633–14637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1182-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eijk R. L. J., Kohlrausch A., Juola J. F., Van de Par S. Audiovisual synchrony and temporal order judgments: Effects of experimental method and stimulus type. Perception and Psychophysics. 2008;70(6):955–968. doi: 10.3758/PP.70.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatakis A., Navarra J., Soto-Faraco S., Spence C. Audiovisual temporal adaptation of speech: temporal order versus simultaneity judgments. Experimental Brain Research. 2008;185(3):521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch R. B., Warren D. H. Immediate perceptual response to intersensory discrepancy. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88(3):638–667. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. L., Linares D., Holcombe A. O. Visuomotor timing compensates for changes in perceptual latency. Current Biology. 2008;18(20):R951–R953. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wundt W. M. Philosophische studien. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Kitazawa S. Reversal of subjective temporal order due to arm crossing. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(7):759–765. doi: 10.1038/89559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarrow K., Jahn N., Durant S., Arnold D. H. Shifts of criteria or neural timing? The assumptions underlying timing perception studies. Consciousness and Cognition. 2011;20(4):1518–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampini M., Guest S., Shore D. I., Spence C. Audio-visual simultaneity judgments. Perception and Psychophysics. 2005;67(3):531–544. doi: 10.3758/BF03193329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampini M., Shore D. I., Spence C. Audiovisual temporal order judgments. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;152(2):198–210. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1536-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S. The disunity of consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7(5):214–218. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]