Abstract

Chlamydia abortus, an obligate intracellular bacterium, is the most common infectious cause of abortion in small ruminants worldwide and has zoonotic potential. We applied multilocus sequence typing (MLST) together with multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) to genotype 94 ruminant C. abortus strains, field isolates and samples collected from 1950 to 2011 in diverse geographic locations, with the aim of delineating C. abortus lineages and clones. MLST revealed the previously identified sequence types (STs) ST19, ST25, ST29 and ST30, plus ST86, a recently-assigned type on the Chlamydiales MLST website and ST87, a novel type harbouring the hemN_21 allele, whereas MLVA recognized seven types (MT1 to MT7). Minimum-spanning-tree analysis suggested that all STs but one (ST30) belonged to a single clonal complex, possibly reflecting the short evolutionary timescale over which the predicted ancestor (ST19) has diversified into three single-locus variants (ST86, ST87 and ST29) and further, through ST86 diversification, into one double-locus variant (ST25). ST descendants have probably arisen through a point mutation evolution mode. Interestingly, MLVA showed that in the ST19 population there was a greater genetic diversity than in other STs, most of which exhibited the same MT over time and geographical distribution. However, the evolutionary pathways of C. abortus STs seem to be diverse across geographic distances with individual STs restricted to particular geographic locations. The ST30 singleton clone displaying geographic specificity and represented by the Greek strains LLG and POS was effectively distinguished from the clonal complex lineage, supporting the notion that possibly two separate host adaptations and hence independent bottlenecks of C. abortus have occurred through time. The combination of MLST and MLVA assays provides an additional level of C. abortus discrimination and may prove useful for the investigation and surveillance of emergent C. abortus clonal populations.

Introduction

Chlamydia abortus is an obligate intracellular bacterium that can colonize the placenta of several animal species causing abortion or stillbirth [1–3]. This organism also represents a threat to human health because it can cause spontaneous abortion and possible life-threatening disease in pregnant women exposed to infected animals [3]. C. abortus is endemic among small ruminants and is the most common cause of infectious abortion in sheep and goats in many countries worldwide [1].

C. abortus is classified as a member of the family Chlamydiaceae that currently comprises the single genus Chlamydia, which contains 11 species (C. abortus, C. avium, C. caviae, C. felis, C. gallinacea, C. muridarum, C. pecorum, C. pneumoniae, C. psittaci, C. suis and C. trachomatis) and a novel candidate species named C. ibidis [4–6]. Studies using different phenotypic and molecular approaches have suggested that the genetic heterogeneity of C. abortus is low. Methods based on the cross reactivity of monoclonal antibodies, restriction patterns of the ompA gene and the phylogenetic analysis of rRNA genes, resulted in little or no evidence of genetic diversity with regard to the host, associated disease or geographical origin of strains [7–9]. However, a more sophisticated molecular typing tool, namely amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis, enabled better discrimination of French strains from those of other origin, even when rRNA and ompA sequences were highly conserved [10]. Further to this, two C. abortus strains, named LLG and POS, isolated in Greece from an aborted goat and sheep, respectively [11,12], were found to be considerably different from other C. abortus strains circulating in the same area. These strains were characterized as variants on the basis of unique inclusion morphology, differences in polypeptide profiles and antibody cross-reactivity, diversity of rRNA, ompA and pmp sequences, and different behavior and ability to colonize the placenta and fetus compared to other wild-type strains [11–17]. Comparison of the genome sequence of the LLG strain with the wild-type C. abortus reference strain S26/3 revealed notable differences in the pseudogene content [18,19]. rRNA secondary structure phylogeny revealed that the two Greek variant strains could represent one distinct lineage evolving independently from other C. abortus strains, to such an extent that "subspecies" status has been suggested for them [20].

Interestingly, a recent study using multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA), as well as a different approach using a multilocus sequence typing (MLST) system, has allowed the differentiation of C. abortus strains into distinct genotypes [21,22]. The MLVA typing method, based on the analysis of five VNTR loci, enabled the clustering of 145 C. abortus strains into six genotypes [21]. In contrast, MLST analysis targeting seven housekeeping genes [23], recognized four sequence types (STs) among the 16 C. abortus strains examined [22]. Having considered that MLST was evaluated on too few C. abortus strains, this study aimed to determine the suitability of MLST for genotyping C. abortus in comparison to MLVA. To achieve this, a well-referenced collection of C. abortus strains of known MLVA genotypes, along with two other collections of field isolates and samples were genotyped. In addition, we aimed to explore and delineate the C. abortus clonal lineages to obtain new insights into how clones or lineages of particular epidemiological relevance emerge and diversify.

Materials and Methods

C. abortus strains, field isolates and samples

In this study a total of 94 C. abortus genomic DNAs were analyzed. These comprised: (i) a collection of 33 strains (panel A) that were representative of all C. abortus genotypes, as determined by MLVA [21]; (ii) a collection of 21 isolates (panel B) randomly selected from C. abortus field isolates belonging to the predominant MLVA genotype MT2 [21]; and (iii) a collection of 40 field pathological samples (panel C) obtained from cases of abortion occurring in sheep, goats and cattle.

The C. abortus strains and isolates used in this study originated from nine countries and were collected between 1950 and 2011. Genomic DNAs were extracted (QIAamp DNA mini Kit; Qiagen) from the first or second culture passage of the original strains and isolates. Additional field samples originated from different regional veterinary diagnostic laboratories or veterinary services in France, Greece and Italy, from abortion cases between 2005 and 2011. The origin and source of the C. abortus strains, isolates and samples investigated are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. MLST profile and epidemiological characteristics of 33 representative strains (panel A) of all C. abortus genotypes determined by MLVA and characterized as MTs (MT1 to MT7).

| MLVA Type | Type-strain for MLVA | Host | Clinical origin | Country | MLST alleles | MLST Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gatA | oppA | hflX | gidA | enoA | hemN | fumC | ||||||

| MT1 | C9/98 | sheep | abortion | De | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| MT2 | Kra | goat | abortion | De | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 18 | ST29 |

| Z178/02* | sheep | abortion | De | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB1 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB4 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB7 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB8 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB15* | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB16 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| VB1 | sheep | epididymitis | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| OC1 | sheep | conjunctivitis | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| 1B | - | AB7-mutant | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| 1H | - | AB7-mutant | Fr | 18 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST25 | |

| AB13 | sheep | abortion | Fr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST86 | |

| AV1 | cattle | abortion | Fr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST86 | |

| AC1 | goat | abortion | Fr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST86 | |

| 60172 | goat | abortion | It | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST86 | |

| 38552 | sheep | abortion | It | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 5 | ST86 | |

| Krauss-15 | goat | abortion | Tu | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 18 | ST29 | |

| FAG | goat | abortion | Gr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| VPG | goat | abortion | Gr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| MT3 | 71 | sheep | intestinal | Gr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| B577 | sheep | abortion | USA | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| Mo907 | sheep | intestinal | USA | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| Z1215/86 | cattle | abortion | De | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| MT4 | FAS | sheep | abortion | Gr | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| 4PV | goat | abortion | It | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| BAF | cattle | abortion | UK | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| MT5 | A22 | sheep | abortion | UK | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| S26/3 | sheep | abortion | UK | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | ST19 | |

| MT6 | LLG | goat | abortion | Gr | 13 | 18 | 6 | 19 | 16 | 4 | 17 | ST30 |

| POS | sheep | abortion | Gr | 13 | 18 | 6 | 19 | 16 | 4 | 17 | ST30 | |

| MT7 | CY71 | sheep | abortion | Cy | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 18 | ST29 |

* The Z178/02 and AB15 strains exhibited the 1B-vaccine-type profile; Z178/02 was recovered from a diseased animal in a vaccinated sheep flock while the AB15 strain from an unvaccinated ewe which had extensive contact with a vaccinated herd at the INRA facility in Nouzilly, in 1986, during the original vaccine trials.

The MLVA and MLST types (MTs and STs, respectively) as well as the most diverse MLST loci are indicated in bold. Country abbreviations: De, Germany; Fr, France; Gr, Greece; It, Italy; Tu, Tunisia; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; Cy, Cyprus.

Table 2. MLST profile based on gatA, hemN and fumC loci of C. abortus field isolates (n = 21; panel B) and field samples (n = 40; panel C) with the vast majority of them belonging to MT2 a .

| C. abortus field isolates | C. abortus field samples | Host | Country | MLST alleles | MLST type b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gatA | hemN | fumC | |||||

| AB2, AB11 | 11–1100_L029, 11–1100_L030, 11–1775_Q069, 11–1775_Q070 | sheep | Fr | 5 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| HAS, KAS | 09–772_13_74/6S, 09–772_18_81/6S, 09–772_24_88/6S, 09–772_26_41/6S | sheep | Gr | 5 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| LGG, TRG | ‒ | goat | Gr | 5 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| ‒ | 09–772_PV4_11371/09 | goat | It | 5 | 4 | 5 | ST19 |

| 11–232_Ec797, 11–232_Ec838 | 11–1100_L038, 11–1100_L043*, 11–1100_L045, 11–1775_Q072*, 11–1775_Q073* | sheep | Fr | 18 | 14 | 5 | ST25 |

| ‒ | 11–0178_E053, 11–0178_E099 | cattle | Fr | 18 | 14 | 5 | ST25 |

| SB1 | ‒ | springbok | Fr | 18 | 14 | 5 | ST25 |

| ‒ | 09–772_15_15/6Sa * | sheep | Gr | 18 | 14 | 5 | ST25 |

| ‒ | 09–772_PV10_327435/07 a * | goat | It | 18 | 14 | 5 | ST25 |

| C21/98, A-57, A-55 | ‒ | goat | Na | 5 | 4 | 18 | ST29 |

| 15, 363, 469, 532 | ‒ | goat | Tu | 5 | 4 | 18 | ST29 |

| ‒ | 09–772_3_3/5Sa | sheep | Gr | 5 | 4 | 18 | ST29 |

| ‒ | 09–772_66_30/9Ga | goat | Gr | 13 | 4 | 17 | ST30 |

| AB22, 10–2431_Moulin56 | 11–1779_G003, 11–1779_G008, 11–1100_L015, 11–1100_L044, 11–1100_L047, 11–1100_L060, 11–1429_N084, 11–1697_Q034, 11–1775_Q062, 11–1775_Q064, 11–1775_Q066, 11–1775_Q067, 11–1775_Q068, 11–1775_Q071 | sheep | Fr | 5 | 14 | 5 | ST86 |

| iC1 | ‒ | goat | Fr | 5 | 14 | 5 | ST86 |

| ‒ | 11–0178_E065 | cattle | Fr | 5 | 14 | 5 | ST86 |

| 1107/1, 36550 | 09–772_PV2_7172/09, 09–772_PV3_10283/09, 09–772_PV11_2473/08, 09–772_PV9_57768/06 | goat | It | 5 | 14 | 5 | ST86 |

| ‒ | 09–772_9_69/6S | sheep | Gr | 5 | 21 | 5 | ST87 |

a All C. abortus isolates and samples typed by MLVA exhibited the genotype MT2 with exception of the 09–772_66_30/9G sample belonging to MT6; the MLVA type of the 09–772_PV10_327435/07 sample was not typeable due to the absence of ChlaAb_914 locus amplification, while the MLVA type of 09–772_15_15/6S and 09–772_3_3/5S samples was not determined due to their inadequate quantity. C. abortus field samples marked with asterisks (*) displayed the 1B-vaccine-type profile.

b The complete MLST profile was also established for the novel STs. The MLST types (STs) are indicated in bold.

Country abbreviations: Fr, France; Gr, Greece; It, Italy; Tu, Tunisia; Na, Namibia

Detection of C. abortus DNA and the 1B-vaccine-type profile

All DNA samples were confirmed to be C. abortus with a species-specific real-time PCR assay targeting the ompA gene [24] prior to genotypic characterization. Furthermore, the previously described PCR-RFLP and/or the high-resolution melt PCR (HRM-PCR) assays [25,26] were used to discriminate vaccine-strain-type from wild-type field isolates and samples.

MLVA genotyping

MLVA genotyping was performed by targeting five tandem repeat loci, as previously described [21]. Repeats were amplified using primer sets ChlaAb_457, ChlaAb_581, ChlaAb_620, ChlaAb_914 and ChlaAb_300, and allele numbers were assigned based on fragment sizes. Numerical values were assigned for distinct MLVA types, characterized as MTs (Table 1).

MLST genotyping

MLST genotyping targeted seven housekeeping genes, namely gatA, oppA, hflX, gidA, enoA, hemN and fumC, as previously described [23]. Target genes were amplified and sequenced using primers and conditions described on the Chlamydiales MLST website (http://pubmlst.org/chlamydiales/http://mlst.ucc.ie/). Sequencing of both DNA strands was performed by Eurofins (Germany). Numbers for alleles and sequence types (STs) were assigned in accordance with the Chlamydiales MLST Database.

Assignment to clonal complex

MLST and MLVA results were entered into BioNumerics software v7.1 (Applied Maths) for minimum-spanning-tree analysis. Priority rules within the BioNumerics software were set to assign the primary founder (clonal ancestor) as the ST that initially would diversify to produce variants that differ at only one of the seven loci, as was previously described for the eBURST algorithm for inferring patterns of evolutionary descent from MLST data [27]. The clonal complex was defined as a cluster of STs, in which all STs were linked as single-locus variants to at least one other ST. STs not sharing alleles with any other ST in the dataset at six of the seven loci were assigned as singletons [27].

Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum likelihood trees for each chlamydial MLST locus were reconstructed to determine the extent by which the phylogenetic signal varied between gene loci, testing for possible recombination [28,29]. For each unique C. abortus ST, the sequences of all seven loci were concatenated to produce an in-frame sequence of 3,098 bp, and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed. The HKY85 model of nucleotide substitution, assuming a discrete gamma distribution with eight categories, was used for tree reconstruction using MEGA5 software [30]. dN/dS ratios were computed by the method of Nei and Gojobori [31] as implemented in MEGA5 [30]. An unweighted pair group method with averages (UPGMA) dendrogram derived from three concatenated sequences of the most diverse loci was constructed to cluster the MLST and MLVA profiles in combination with their epidemiological data.

Results and Discussion

Assessment of C. abortus genotypes by MLVA and MLST

Initially, the MLST scheme was applied to the panel A strains to assess the genetic relatedness of strains with particular MLVA profiles. Specifically, 32 representative strains belonging to the six MLVA genotypes (MT1 to MT6) [21] were analyzed, including the mutant vaccine-1B and 1H strains (Table 1). Another vaccine strain (CY71), which was used until 2006 in the preparation of an inactivated, whole-organism adjuvanted vaccine in Cyprus, was also included as a new MLVA genotype, designated MT7 (Table 1). The CY71 strain presented with the profile 0.5-1-2-1-3 by the previously detailed VNTRs series, harbouring a new size for the ChlaAb_457 marker (S1 Fig).

MLST showed that this collection of 33 strains comprised five distinct STs, namely the previously identified ST19, ST25, ST29 and ST30 [22], plus a new allelic combination, recently designated ST86 on the Chlamydiales MLST website. This new allelic profile (ST86) was detected in five strains belonging to MT2 (Table 1). Interestingly, strains belonging to MT2 harboured a variety of STs (ST19, ST25, ST29 and ST86). In contrast, strains that were grouped by MLST as ST19 could be further differentiated by MLVA into MT1, MT2, MT3, MT4 and MT5. The same was also observed for ST29 that was delineated into two MTs, MT2 and MT7. The variant C. abortus strains LLG and POS [12,13,15,17,20], with distinct profile MT6 [21], also showed a distinct MLST profile (ST30). This is consistent with the previous study where, 16 C. abortus strains, including LLG and POS, were typed by MLST [22]. However, a discrepancy was observed for the strain AB7 and its mutant vaccine-1B strain in comparison with the previously reported results [22] as, in our study, these two strains were indistinguishable. This is thought to result from the use of an incorrect strain, originally thought to be "AB7", in that study. Among panel A strains, the most diverse loci were found to be gatA, hemN and fumC, while oppA, gidA and enoA exclusively differentiated variant strains LLG and POS (Table 1). Since gatA, hemN and fumC were responsible for a substantial part of the overall resolution obtained with the MLST system, resulting in a clustering consistent with that obtained when all loci were used (data not shown), their allelic profiles were analyzed for all field isolates and samples (Table 2). All isolates and samples genotyped by MLVA belonged to MT2, with the exception of one sample belonging to MT6. Another sample could not be genotyped due to the absence of ChlaAb_914 locus amplification. Incomplete MLVA profiles, possibly resulting from the lack of a VNTR region or sequence polymorphisms and modifications that hinder annealing of primers, have been observed in the past for other bacteria [32,33]. MLST analysis resulted in the detection of a new allelic profile, restricted to only one sample (09–772_9_69/6S in Table 2) harbouring a novel hemN allele, which was deposited and denoted hemN_21 on the Chlamydiales MLST website. The complete MLST profile was established for this novel ST (ST87; gatA_5, oppA_8, hflX_6, gidA_8, enoA_8, hemN_21, fumC_5). Altogether, six STs were identified, namely ST19, ST25, ST29, ST30, ST86 and ST87. As expected, the ST30 profile was detected and confirmed in one field sample (09–772_66_30/9G in Table 2) presenting profile MT6.

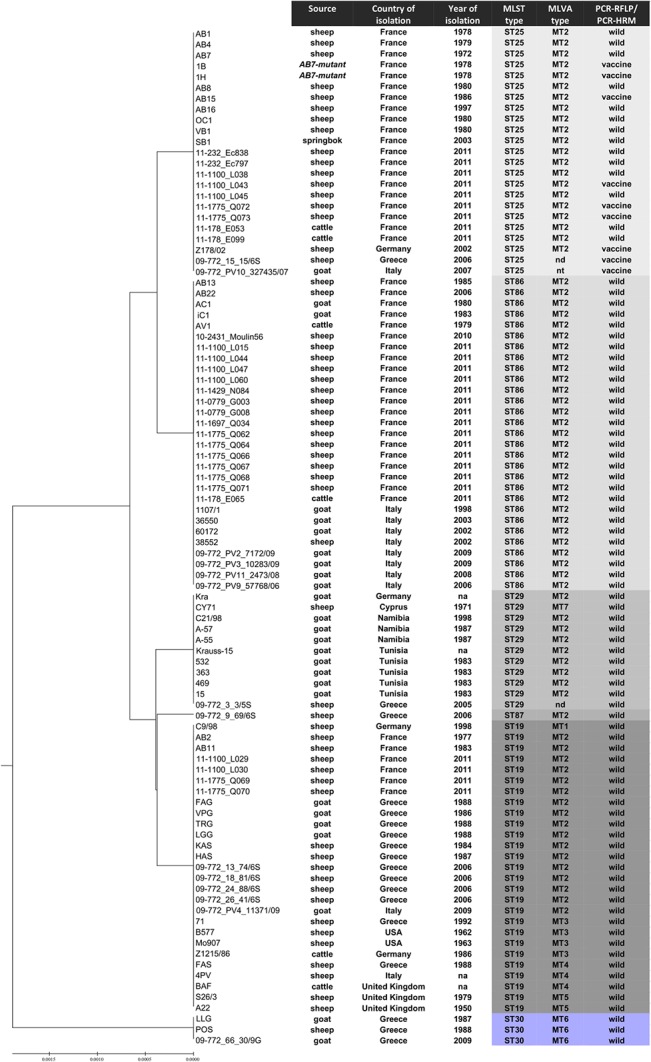

In order to study relationships among strains, isolates and samples with particular STs and compare them with the other genotyping findings, a UPGMA dendrogram was constructed based on the concatenated sequences of gatA, hemN and fumC loci of all 94 C. abortus isolates tested (Fig 1). Two deep branches were evident. The major branch included two distinct clades, one consisting of genotypes ST25 and ST86 that harboured exclusively MT2 with the vaccine-type isolates restricted into ST25, and the other clade consisting of genotypes ST29, ST87 and ST19 that comprised six MTs (MT1 to MT5 and MT7). The more distantly related branch consisted of three C. abortus isolates exhibiting genotypes ST30 and MT6 exclusively. These differentiated branches or clades might reflect pathways; however, it should be noted that, although clustering algorithms such as UPGMA identify closely related genotypes, they do not provide information on the founding genotypes or the likely patterns of evolutionary descent within a group.

Fig 1. Dendrogram illustrating the relationships of MLST types (STs) on the basis of concatenated sequences of gatA, hemN and fumC loci, in comparison with other genotyping findings.

The dendrogram includes 94 C. abortus strains and field isolates or samples, which were collected from ruminant in nine countries over a period of 60 years. The genotypic characteristics of clones are color-coded: the more distantly related ST30 is presented in blue whereas the other STs in shades of gray. The dendrogram was constructed by using the UPGMA algorithm. Linkage distances are indicated on the scale at the bottom. na, not available information; nd, not determined; nt, not typeable.

Identification and delineation of the C. abortus clonal complex and lineages

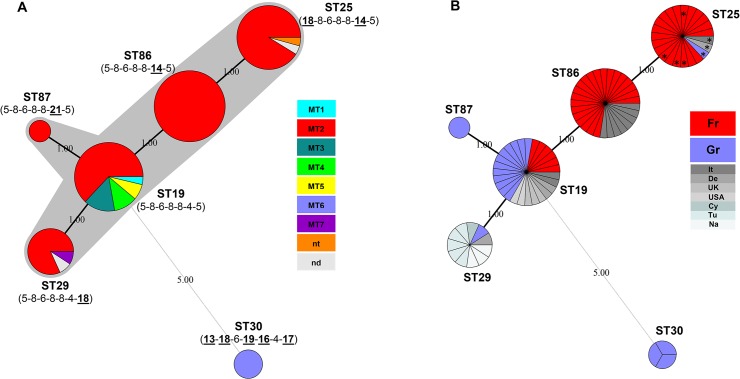

The evolutionary pathways within C. abortus were reconstructed using minimum-spanning-tree analysis [27]. The analysis of the MLST data of the 94 C. abortus isolates assigned ST19 as a predicted ancestor. This ST is predicted to have diversified into the single-locus variants ST86, ST87 and ST29, with ST86 to have diversified further to produce its single-locus variant ST25 (double-locus variant of ST19) (Fig 2A). Minimum-spanning-tree analysis suggested that all STs identified in this study, with the exception of ST30, belonged to one clonal complex (Fig 2A). The simple structure of this clonal complex possibly reflects the very short evolutionary timescale over which ST19 has presumably diverged. ST30 was assigned as singleton clone since this ST differed from every other in the dataset at five or six of the seven MLST loci (Fig 2A) and was therefore considered to be distantly related to the clonal complex [29].

Fig 2. Minimum-spanning-tree analysis of 94 C. abortus isolates genotyped by MLST.

Each circle represents a distinct MLST type (ST). The size of the circles is related to the number of strains, isolates or samples composing the particular STs. Solid lines connect single-locus variant STs while the light grey dashed line indicates the ST that differs in more than one locus; the number of locus variations is indicated between the circles. A. Minimum-spanning-tree illustrating the evolutionary pathways of ruminant C. abortus clones. The gray halo surrounding the circles delineates the C. abortus clonal complex. Alteration in MLST alleles compared with predicted ancestor ST19 are underlined. The circle colours indicate the corresponding MLVA types (MTs); nd, MT not determined; nt, MT not typeable. B. Minimum-spanning-tree exemplifying the different ST distribution patterns among C. abortus strains, isolates and samples originating from France and Greece. The colours indicate the corresponding countries of isolation (France, red; Greece, blue; Other countries, shades of gray). With asterisks (*) are labeled the field isolates or samples displaying the 1B-vaccine-type profile.

Examination of the sequence changes during clonal diversification showed that the single-locus variants possessed variant alleles that were both unique within the dataset (i.e. found only within the single-locus variant) and differed at only a single nucleotide site from the allele in the putative ancestral ST (S2 Fig), characteristics that are consistent with a predominantly mutation mode of evolution [29,34]. Out of the four point mutations that occurred within the clonal complex, three were synonymous and one was nonsynonymous (S2 Fig; listed in S1 Table). It might be expected that synonymous mutations, which are more likely to be neutral, should outweigh nonsynonymous substitutions, since the "core" genes used for MLST are subjected to stabilizing selection. A trend in the direction of positive selection was observed for the nonsynonymous mutation harboured on the novel hemN_21 allele (S2 Table).

Minimum-spanning-tree analysis of the ruminant C. abortus STs and the avian ST36 previously designated as C. abortus [22], showed the latter presenting a separate singleton topology (S3A Fig). In order to establish the relationships between the C. abortus clonal complex and other chlamydial clonal lineages, especially the ruminant ST30 and avian ST36 singletons, the degree of phylogenetic consistency between MLST locus trees was examined (S4 Fig). In all trees there was evidence for a conserved C. abortus branch and conserved division between the C. abortus clonal complex and the singleton lineages (S4 Fig). Some exceptions to this division, particularly concerning the hemN and hflX loci, have been noted, demonstrating that some recombination has possibly occurred among these lineages. Interestingly, it has been recently revealed that intraspecific homologous recombination likely contributed significantly to the diversification and evolution of C. trachomatis and C. psittaci [35,36]. However, shared alleles among the different lineages (S3B Fig) might instead reflect identity by presumably relatively old descent. It is worth noting that based on rRNA phylogeny the ruminant C. abortus lineages were found to be descendants of an ancestor common with the avian one [20,22]. An evolutionary bottleneck as a consequence of host niche adaptation resulting in genome degradation [18], might have contributed to the extraordinary genetic conservation and the clonal population structure of C. abortus. An evolutionary bottleneck history has also been proposed for other bacterial pathogens indicating purely clonal evolution, the so-called monomorphic lineages [37,38]. Meanwhile, genome comparison of the original ST30 strain, namely LLG, with S26/3, a reference wild-type strain belonging to the C. abortus clonal complex, revealed the greatest variations to occur in pseudogene content [18,19], indicating that the ST30 host adaptation and the associated bottleneck possibly occurred independently from those of the C. abortus clonal complex lineage.

Distribution of C. abortus clonal populations

The C. abortus strains, isolates and samples examined in this study were collected over a period of 60 years from geographically widespread regions; nine countries, France, Greece, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, Cyprus, the United States, Tunisia and Namibia, with the majority originating from the first three (Fig 1). Some C. abortus clones showed geographic specificity in their distribution, such as ST25 (wild-type isolates) in France, and ST87 as well as the singleton ST30 in Greece.

In particular, the ST19 population was clearly dispersed in Europe and is also found in the United States (Fig 1). However, the evolutionary pathways of C. abortus STs seem to be diverse across geographic distances, as exemplified by the different ST distribution patterns among C. abortus strains, isolates and samples originating from France and Greece (Figs 1 and 2B). ST19 was predominant among clones recovered in Greece but, interestingly, in France this clone was less frequent than its descendants ST86 and ST25, even when only taking into account isolates from the same year. It is remarkable that the synonymous changes resulting in the emergence of hemN_14 and gatA_18 alleles of ST86 and ST25, respectively (Fig 2 and S2 Fig ), might affect the "competitive" balance between isolates. Random genetic drift and neutral evolution associated with synonymous mutations [39,40] seem to be the dominant evolutionary dynamic that allows alleles to reach high frequencies within the French C. abortus population. Genetic hitchhiking of the alleles with advantageous mutations at other loci [40,41] might potentially play a role in the frequency of derived C. abortus clones. Additionally, allele migration into or out of a population through animal mobility, may affect the marked change in allele frequencies and the distribution. With regard to this, it should be noted that French C. abortus clones were collected from major French breeding areas. In any case, the currently circulating C. abortus clones in France appeared in the country before the introduction, in the middle 90s, of the virulence-attenuated live 1B vaccine. It is also worth noting that in Greece as well as in Italy and Germany, only the vaccine-type of ST25 has been recovered, clearly after the licensing and commercialization of the 1B vaccine in these countries (Figs 1 and 2B).

ST29 isolates were collected from 1971 to 2005 mostly from southern regions, from Greece, Cyprus, Tunisia and Namibia, and also from Germany (Fig 1). It is unclear whether this clone, being a descendant of the ST19 (Fig 2), has emerged locally, or it has spread globally on at least five occasions. The clone ST87 harbouring the nonsynonymous potentially advantageous mutation on hemN_21 allele possibly arose recently in Greece (Table 2 and Fig 1) and, might undergo fixation in the local C. abortus population. However, genetic investigation of isolates collected locally over a long period may help confirm any hypothesis concerning C. abortus selection and diversity, particularly for some genotypes that appear to be rare or restricted to particular geographic locations. Such a genotype is the singleton clone ST30. The evidence suggests that this C. abortus lineage has probably emerged in Northern Greece, has not been disseminated far and wide and has been locally endemic for several years. Interestingly, the same genotype has been retrieved two decades after isolation of the original two strains (LLG and POS) of this lineage (Fig 1). Remarkably, in Northern Greece C. abortus has been found to be highly diverse even across very short distances. The overall diversity in this area may be the result of independent and parallel evolution of locally differentiated subpopulations that may selectively maintain their favorable genetic background for decades (Fig 1). However, further studies are needed to determine the population dynamics of C. abortus, both over time and a wider geographic area.

Combination of MLST and MLVA profiles

Whereas the ST86 and ST25 populations showed the same MLVA profile (MT2) over time and/or geographical distribution, the population of ST19 and, to a lesser extent ST29, diversified into multiple MT subpopulations (Figs 1 and 2A).

As the markers used for MLST (targeting housekeeping genes) evolve slowly and are highly conserved, the resolution provided by MLST is low for the investigation of recent evolution and, above all, for short-term epidemiological studies. Unlike MLST, MLVA targets several types of markers with variation in the numbers of repeats at particular loci, to be used by some bacteria as a means of genomic and phenotypic adaptation to the environment [42]. In our case, three of the VNTR markers that were located within genes or open reading frames encoding predicted membrane or exported proteins (markers ChlaAb_300, ChlaAb_581 and ChlaAb_620/pseudogene) [21] and as surface-located factors presumably could be under selective pressure [43]. Indeed, most of the MT variations observed in the ST19 were due to tandem-repeat differences at either Chla_581 or Chla_620 (mostly) (S5 Fig). Finally, it is important to keep in mind that in the case of MLVA (like in other methods) some similarities in the genotyping patterns might have arisen by convergent evolution [44]. Results presented here indicate that MLVA improved the resolution and discriminated further the ST19 and ST29 subpopulations, possibly enhancing micro-epidemiological accuracy crucial for the understanding of the dissemination of C. abortus populations in defined areas (Fig 1). Meanwhile, the use of MLST as a backbone to support or further differentiate the MLVA genotypes will be useful in inferring the genetic relationships of C. abortus lineages and clones. In all strains, we found six distinct STs, seven distinct MTs, and 11 distinct combinations of ST and MT, suggesting that a combination of MLST and MLVA provides additional resolution and may prove useful for the investigation and surveillance of emergent C. abortus clonal populations.

Conclusions

In this study the molecular characterization of 94 ruminant C. abortus strains, isolates and field samples collected from 1950 to 2011 from diverse geographic locations reveals new insights into the population structure, genetic diversity and potentially the evolutionary history of C. abortus. Taken together, MLST and MLVA analyses demonstrated that C. abortus, similarly to other genetically monomorphic bacteria, has a predominantly clonal population structure consisting of subpopulations, many of which seem to be associated with particular geographic regions. The analyses further revealed that ruminant C. abortus strains are more genetically diverse than generally recognized, since novel genotypes have been detected. Both techniques effectively distinguished the "LLG/POS variant" lineage from the "clonal complex" one, supporting the notion that possibly two separate host niche adaptations of C. abortus have occurred through time. In combination, MLST and MLVA may provide additional information into the origins and evolutionary relationships of circulating C. abortus populations.

Supporting Information

PCR amplification of C. abortus strains AB7 (A), S26/3 (B), POS (C) and CY71 (D). A 100-bp ladder (100–1000 bp) is run on both sides of sample group. The number of repeat units within each allele is indicated.

(TIFF)

Consensus blocks are shaded light-gray; 20% has been taking as a minimal fraction of a specific nucleotide at a defined consensus position. Amino-acid substitutions among C. abortus MLST-encoded protein alleles (b) Conserved sites are shaded gray in the protein sequence alignments. A. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus hemN alleles (in boldface; hemN_4, hemN_21, hemN_14 ruminant and avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The positions in which the C. abortus hemN alleles present substitutions (positions 261 & 343) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs within the clonal complex at the position 261 (alleles hemN_4 and hemN_14) is synonymous, whereas the substitution at the position 343 (alleles hemN_4 and hemN_21) is non-synonymous (see b). Residues G and A, at the positions 261 & 343, respectively, are unique among all chlamydial hemN alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among three C. abortus hemN-encoded protein alleles (b) The non-synonymous amino-acid Thr (T) harboured at the position 115 of hemN_21-encoded protein is unique among all chlamydiae; shaded by distinct colour. B. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus gatA alleles (in boldface; gatA_5, gatA_18, gatA_13 ruminant and avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The positions in which the C. abortus gatA alleles present substitutions (positions 165 & 374) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs at the position 165 within the clonal complex (alleles gatA_5 and gatA_18) is synonymous (see b). Residue G at the position 374 characteristic for C. abortus clonal complex, is unique among all chlamydial gatA alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among three C. abortus gatA-encoded protein alleles (b) The amino-acid Gly (G) characterizing the C. abortus clonal complex is unique among all chlamydial gatA-encoded protein alleles at the conserved position 125; shaded by distinct colour. C. Nucleotide substitutions among four C. abortus fumC alleles (in boldface; fumC_5, fumC_18, fumC_17, fumC_14 ruminant or avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The position in which the C. abortus fumC alleles present substitutions (positions 165, 195, 243 & 440) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs at the position 440 within the clonal complex (alleles fumC_5 and fumC_18) is synonymous (see b). Residue T at position 243 of fumC_17 harbouring in the LLG singleton is unique among all chlamydial fumC alleles. Sequence alignment among C. abortus fumC-encoded protein alleles (b) Non-synonymous substitutions were not observed. D. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus enoA alleles (in boldface; enoA_8, enoA_16, enoA_14 ruminant or avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The position in which the C. abortus enoA alleles present substitutions (positions 249, 291 & 317) are shaded by colours. Residue A at the conserved position 317, is unique among all chlamydial enoA alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among enoA-encoded protein alleles (b) The non-synonymous amino-acid Glu (E) characterizing the LLG singleton is unique among all chlamydial enoA-encoded protein alleles at the conserved position 106; shaded by distinct colour.

(PDF)

A. Minimum-spanning-tree analysis of the ruminant C. abortus STs and the avian ST36 previously designated as C. abortus [22]. The gray halo surrounding the circles delineates the C. abortus clonal complex. The numbers between the circles define the number of locus variations. The circle colours indicate the corresponding MLVA types (MTs); nt, MT not typeable. B. The individual MLST allelic profile of ST36 is shown in comparison with the other C. abortus profiles.

(TIFF)

A. Maximum likelihood trees are shown for each MLST locus; in each tree locus-alleles corresponding to known chlamydial STs are included. B. A maximum likelihood tree, highlighted in red border, is shown on the basis of concatenated sequences of all seven loci corresponding to six ruminant (ST19, ST29, ST87, ST86, ST25, ST30) and one avian (ST36) C. abortus STs. STs belonging to the clonal complex or singleton lineages are highlighted white on a black or grey background, respectively.

(TIFF)

A. In the minimum-spanning-tree the MTs are displayed as circles. Circle sizes represent the number of C. abortus strains, isolates or samples; circles are colored by the corresponding STs (see Fig 1; nt, MT not typeable). Numbers between the circles define the number of locus variations. Thick lines connect MTs that differ in a single VNTR locus while the thin line connects MTs that differ in more than one locus. B. The individual MLVA allelic profiles are shown for comparison.

(TIFF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Ilias Kappas (Department of Genetics, Development and Molecular Biology, School of Biology, AUTh, Greece) for sharing views and illuminating aspects on issues related to evolutionary genetics.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was performed at the ANSES (Maisons-Alfort, France). The study involved strains, isolates and samples processed at the ANSES, the School of Veterinary Medicine of AUTh (Thessaloniki, Greece), the IZSLER "Bruno Ubertini" (Pavia, Italy), the INRA (Nouzilly, France), the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (Jena, Germany) and the Moredun Research Institute (Edinburgh, Scotland). No external funding supported this work.

References

- 1. Aitken ID, Longbottom D. Chlamydial abortion In: Aitken ID, editor. Diseases of Sheep 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kerr K, Entrican G, McKeever D, Longbottom D. Immunopathology of Chlamydophila abortus infection in sheep and mice. Res Vet Sci. 2005; 78:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Longbottom D, Coulter LJ. Animal chlamydioses and zoonotic implications. J Comp Pathol. 2003; 128:217–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuo CC, Stephens RS, Bavoil PM, Kaltenboeck B. Genus I. Chlamydia. Jones, Rake and Stearns 1945, 55AL In: Krieg N, Staley J, Brown D, Hedlund B, Paster B, Ward W, et al. editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2nd ed. vol 4 New York, USA: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 846–865. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sachse K, Laroucau K, Riege K, Wehner S, Dilcher M, Creasy HH, et al. Evidence for the existence of two new members of the family Chlamydiaceae and proposal of Chlamydia avium sp. nov. and Chlamydia gallinacea sp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2014; 37:79–88. 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vorimore F, Hsia RC, Huot-Creasy H, Bastian S, Deruyter L, Passet A, et al. Isolation of a new Chlamydia species from the feral Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus): Chlamydia ibidis . PLoS One. 2013; 8(9): e74823 10.1371/journal.pone.0074823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Denamur E, Sayada C, Souriau A, Orfila J, Rodolakis A, Elion J. Restriction pattern of the major outer-membrane protein gene provides evidence for a homogeneous invasive group among ruminant isolates of Chlamydia psittaci . J Gen Microbiol. 1991; 137:2525–2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salinas J, Souriau A, Cuello F, Rodolakis A. Antigenic diversity of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains demonstrated by the indirect micro-immunofluorescence test with monoclonal antibodies. Vet Microbiol. 1995; 43:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Everett KD, Bush RM, Andersen AA. Emended description of the order Chlamydiales, proposal of Parachlamydiaceae fam. nov. and Simkaniaceae fam. nov., each containing one monotypic genus, revised taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, including a new genus and five new species, and standards for the identification of organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999; 49:415–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boumedine KS, Rodolakis A. AFLP allows the identification of genomic markers of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains useful for typing and epidemiological studies. Res Microbiol. 1998; 149:735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siarkou V. In vivo studies of the immunological heterogeneity of abortion strains of Chlamydia psittaci Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. 1992. 10.12681/eadd/8983 Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10442/hedi/8983 [DOI]

- 12. Siarkou V, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Papadopoulos O. Subspecies variation in Greek strains of Chlamydophila abortus . Vet Microbiol. 2002; 85:145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vretou E, Loutrari H, Mariani L, Costelidou K, Eliades P, Conidou G, et al. Diversity among abortion strains of Chlamydia psittaci demonstrated by inclusion morphology, polypeptide profiles and monoclonal antibodies. Vet Microbiol. 1996; 51:275–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vretou E, Psarrou E, Kaisar M, Vlisidou I, Salti-Montesanto V, Longbottom D. Identification of protective epitopes by sequencing of the major outer membrane protein gene of a variant strain of Chlamydia psittaci serotype 1 (Chlamydophila abortus). Infect Immun. 2001; 69:607–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bouakane A, Benchaïeb I, Rodolakis A. Abortive potency of Chlamydophila abortus in pregnant mice is not directly correlated with placental and fetal colonization levels. Infect Immun. 2003; 71:7219–7222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouakane A, Rekiki A, Rodolakis A. Protection of pregnant mice against placental and splenic infection by three strains of Chlamydophila abortus with a live 1B vaccine. Vet Rec. 2005; 157:771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sait M, Clark EM, Wheelhouse N, Spalding L, Livingstone M, Sachse K, et al. Genetic variability of Chlamydophila abortus strains assessed by PCR-RFLP analysis of polymorphic membrane protein-encoding genes. Vet Microbiol. 2011; 151:284–290. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomson NR, Yeats C, Bell K, Holden MT, Bentley SD, Livingstone M, et al. The Chlamydophila abortus genome sequence reveals an array of variable proteins that contribute to interspecies variation. Genome Res. 2005; 15:629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sait M, Clark EM, Wheelhouse N, Livingstone M, Spalding L, Siarkou VI, et al. Genome sequence of the Chlamydophila abortus variant strain LLG. J Bacteriol. 2011; 193:4276–4277. 10.1128/JB.05290-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siarkou VI, Stamatakis A, Kappas I, Hadweh P, Laroucau K. Evolutionary relationships among Chlamydophila abortus variant strains inferred by rRNA secondary structure-based phylogeny. PLoS ONE. 2011; 6(5): e19813 10.1371/journal.pone.0019813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laroucau K, Vorimore F, Bertin C, Mohamad KY, Thierry S, Hermann W, et al. Genotyping of Chlamydophila abortus strains by multilocus VNTR analysis. Vet Microbiol. 2009; 137:335–344. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pannekoek Y, Dickx V, Beeckman DSA, Jolley KA, Keijzers WC, Vretou E, et al. Multi locus sequence typing of Chlamydia reveals an association between Chlamydia psittaci genotypes and host species. PLoS ONE. 2010; 5(12): e14179 10.1371/journal.pone.0014179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pannekoek Y, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Morré SA, Ossewaarde JM, Langerak AA, et al. Multi locus sequence typing of Chlamydiales: clonal groupings within the obligate intracellular bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis . BMC Microbiol. 2008; 8: 42 10.1186/1471-2180-8-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pantchev A, Sting R, Bauerfeind R, Tyczka J, Sachse K. New real-time PCR tests for species-specific detection of Chlamydophila psittaci and Chlamydophila abortus from tissue samples. Vet J. 2009; 181:145–150. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laroucau K, Vorimore F, Sachse K, Vretou E, Siarkou VI, Willems H, et al. Differential identification of Chlamydophila abortus live vaccine strain 1B and C. abortus field isolates by PCR-RFLP. Vaccine. 2010; 28:5653–5656. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vorimore F, Cavanna N, Vicari N, Magnino S, Willems H, Rodolakis A, et al. High-resolution melt PCR analysis for rapid identification of Chlamydia abortus live vaccine strain 1B among C. abortus strains and field isolates J. Microbiol. Methods. 2012; 90:241–244. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feil E, Li BC, Aanensen DM, Hanage WP, Spratt BG. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J Bacteriol. 2004; 186:1518–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feil E, Holmes EC, Bessen DE, Chan MS, Day NP, Enright MC, et al. Recombination within natural populations of pathogenic bacteria: short-term empirical estimates and long-term phylogenetic consequences. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001; 98:182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feil E, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, Robinson DA, Enright MC, Berendt T, et al. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J Bacteriol. 2003; 185:3307–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol. Evol. 2011; 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986; 3:418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koeck JL, Njanpop-Lafourcade BM, Cade S, Varon E, Sangare L, Valjevac S, et al. Evaluation and selection of tandem repeat loci for Streptococcus pneumoniae MLVA strain typing. BMC Microbiol. 2005; 5: 66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Top J, Willems R, van der Velden S, Asbroek M, Bonten M. Emergence of clonal complex 17 Enterococcus faecium in The Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol. 2008; 46:214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feil EJ, Smith JM, Enright MC, Spratt BG. Estimating recombinational parameters in Streptococcus pneumoniae from multilocus sequence typing data. Genetics. 2000; 154:1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joseph SJ, Didelot X, Rothschild J, de Vries HJ, Morre SA, Read TD, et al. Population genomics of Chlamydia trachomatis: insights on drift, selection, recombination, and population structure. Mol Biol Evol. 2012; 29:3933–3946. 10.1093/molbev/mss198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Read TD, Joseph SJ, Didelot X, Liang B, Patel L, Dean D. Comparative analysis of Chlamydia psittaci genomes reveals the recent emergence of a pathogenic lineage with a broad host range. MBio. 2013; 4: e00604–e00612. 10.1128/mBio.00604-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rattei T, Ott S, Gutacker M, Rupp J, Maass M, Schreiber S, et al. Genetic diversity of the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydophila pneumoniae by genome-wide analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms: evidence for highly clonal population structure. BMC Genomics. 2007; 8: 355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Achtman M. Evolution, population structure, and phylogeography of genetically monomorphic bacterial pathogens. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008; 62:53–70. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Futuyma DJ. Genetic drift: evolution at random In: Futuyma DJ, editor. Evolution. Massachusetts, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sunderland; 2009. pp 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Futuyma DJ. Natural selection and adaptation In: Futuyma DJ, editor. Evolution. Massachusetts, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sunderland; 2009. pp 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith JM, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 1974; 23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martin P, van de Ven T, Mouchel N, Jeffries AC, Hood DW, Moxon ER. Experimentally revised repertoire of putative contingency loci in Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58: evidence for a novel mechanism of phase variation. Mol Microbiol. 2003; 50:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Madoff LC, Michel JL, Gong EW, Kling DE, Kasper DL. Group B streptococci escape host immunity by deletion of tandem repeat elements of the alpha C protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996; 93:4131–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pearson T, Okinaka RT, Foster JT, Keim P. Phylogenetic understanding of clonal populations in an era of whole genome sequencing. Infect Genet Evol. 2009; 9:1010–1019. 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PCR amplification of C. abortus strains AB7 (A), S26/3 (B), POS (C) and CY71 (D). A 100-bp ladder (100–1000 bp) is run on both sides of sample group. The number of repeat units within each allele is indicated.

(TIFF)

Consensus blocks are shaded light-gray; 20% has been taking as a minimal fraction of a specific nucleotide at a defined consensus position. Amino-acid substitutions among C. abortus MLST-encoded protein alleles (b) Conserved sites are shaded gray in the protein sequence alignments. A. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus hemN alleles (in boldface; hemN_4, hemN_21, hemN_14 ruminant and avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The positions in which the C. abortus hemN alleles present substitutions (positions 261 & 343) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs within the clonal complex at the position 261 (alleles hemN_4 and hemN_14) is synonymous, whereas the substitution at the position 343 (alleles hemN_4 and hemN_21) is non-synonymous (see b). Residues G and A, at the positions 261 & 343, respectively, are unique among all chlamydial hemN alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among three C. abortus hemN-encoded protein alleles (b) The non-synonymous amino-acid Thr (T) harboured at the position 115 of hemN_21-encoded protein is unique among all chlamydiae; shaded by distinct colour. B. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus gatA alleles (in boldface; gatA_5, gatA_18, gatA_13 ruminant and avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The positions in which the C. abortus gatA alleles present substitutions (positions 165 & 374) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs at the position 165 within the clonal complex (alleles gatA_5 and gatA_18) is synonymous (see b). Residue G at the position 374 characteristic for C. abortus clonal complex, is unique among all chlamydial gatA alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among three C. abortus gatA-encoded protein alleles (b) The amino-acid Gly (G) characterizing the C. abortus clonal complex is unique among all chlamydial gatA-encoded protein alleles at the conserved position 125; shaded by distinct colour. C. Nucleotide substitutions among four C. abortus fumC alleles (in boldface; fumC_5, fumC_18, fumC_17, fumC_14 ruminant or avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The position in which the C. abortus fumC alleles present substitutions (positions 165, 195, 243 & 440) are shaded by colours. The substitution (point mutation) that occurs at the position 440 within the clonal complex (alleles fumC_5 and fumC_18) is synonymous (see b). Residue T at position 243 of fumC_17 harbouring in the LLG singleton is unique among all chlamydial fumC alleles. Sequence alignment among C. abortus fumC-encoded protein alleles (b) Non-synonymous substitutions were not observed. D. Nucleotide substitutions among three C. abortus enoA alleles (in boldface; enoA_8, enoA_16, enoA_14 ruminant or avian C. abortus alleles) (a) The position in which the C. abortus enoA alleles present substitutions (positions 249, 291 & 317) are shaded by colours. Residue A at the conserved position 317, is unique among all chlamydial enoA alleles. Amino-acid substitutions among enoA-encoded protein alleles (b) The non-synonymous amino-acid Glu (E) characterizing the LLG singleton is unique among all chlamydial enoA-encoded protein alleles at the conserved position 106; shaded by distinct colour.

(PDF)

A. Minimum-spanning-tree analysis of the ruminant C. abortus STs and the avian ST36 previously designated as C. abortus [22]. The gray halo surrounding the circles delineates the C. abortus clonal complex. The numbers between the circles define the number of locus variations. The circle colours indicate the corresponding MLVA types (MTs); nt, MT not typeable. B. The individual MLST allelic profile of ST36 is shown in comparison with the other C. abortus profiles.

(TIFF)

A. Maximum likelihood trees are shown for each MLST locus; in each tree locus-alleles corresponding to known chlamydial STs are included. B. A maximum likelihood tree, highlighted in red border, is shown on the basis of concatenated sequences of all seven loci corresponding to six ruminant (ST19, ST29, ST87, ST86, ST25, ST30) and one avian (ST36) C. abortus STs. STs belonging to the clonal complex or singleton lineages are highlighted white on a black or grey background, respectively.

(TIFF)

A. In the minimum-spanning-tree the MTs are displayed as circles. Circle sizes represent the number of C. abortus strains, isolates or samples; circles are colored by the corresponding STs (see Fig 1; nt, MT not typeable). Numbers between the circles define the number of locus variations. Thick lines connect MTs that differ in a single VNTR locus while the thin line connects MTs that differ in more than one locus. B. The individual MLVA allelic profiles are shown for comparison.

(TIFF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.