Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is estimated to affect 25% of adult women in the US alone. IPV directly impacts women’s ability to use contraception, resulting in many of unintended pregnancies and STIs. This review examines the relationship between IPV and condom and oral contraceptive use within the United States at two levels: the female victim’s perspective on barriers to condom and oral contraceptive use, in conjunction with experiencing IPV (Aim 1) and the male perpetrator’s perspective regarding condom and oral contraceptive use (Aim 2).

STUDY DESIGN

We systematically reviewed and synthesized all publications meeting the study criteria published since 1997. We aimed to categorize the results by emerging themes related to each study aim.

RESULTS

We identified 42 studies that met our inclusion criteria. We found 37 studies that addressed Aim 1. Within this we identified three themes: violence resulting in reduced condom or oral contraceptive use (n=15); condom or oral contraceptive use negotiation (n=15); which we further categorized as IPV due to condom or oral contraceptive request, perceived violence (or fear) of IPV resulting in decreased condom or oral contraceptive use, and sexual relationship power imbalances decreasing the ability to use condoms or oral contraceptives; and reproductive coercion (n=7). We found 5 studies that addressed Aim 2. Most studies were cross-sectional, limiting the ability to determine causality between IPV and condom or oral contraceptive use; however, most studies did find a positive relationship between IPV and decreased condom or oral contraceptive use.

CONCLUSIONS

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research has demonstrated the linkages between female IPV victimization/male IPV perpetration and condom or oral contraceptive use. However, additional qualitative and longitudinal research is needed to improve the understanding of dynamics in relationships with IPV and determine causality between IPV, intermediate variables (e.g., contraceptive use negotiation, sexual relationship power dynamics, reproductive coercion), and condom and oral contraceptive use. Assessing the relationship between IPV and reproductive coercion may elucidate barriers to contraceptive use as well as opportunities for interventions to increase contraceptive use (such as forms of contraception with less partner influence) and reduce IPV and reproductive coercion.

Keywords: condom use, oral contraception, birth control, intimate partner violence, reproductive coercion, United States

1. INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) affects millions of women each year and has been recognized as a leading cause for poor health, disability, and death among women of reproductive age.[1] Population-based surveys found 13–61% of women throughout the world reported being physically assaulted by an intimate male partner during their lives[1] and 6–59% of women up to 49 years of age had experienced sexual assault by a partner at some point in their lives.[2] Specifically within the United States, 25% of adult women have been victims of severe IPV.[3]

Further, in the United States, it is reported that only 62% of women aged 15–44 use contraception, equating to 23.2 million women who do not.[4] It is also estimated that 37% of births are unintended at the time of conception.[5] Moreover, as identified by Coker, IPV is known to impact a woman’s ability to use contraception and to result in unplanned pregnancies in a variety of ways (e.g., through physical violence and the ability to use barrier methods of contraception and through reduced self-esteem limiting the ability to negotiate condom use).[6] Given this, the prevalence of IPV in the United States, and its linkages with contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy, it can be estimated that 2.1 million unintended pregnancies have resulted from this synergy.[4–6] We should also point out that IPV can interfere with a woman’s desire to be pregnant (and can lead to pregnancy loss from trauma) as well as limit her ability to protect herself from STIs.[6] We also acknowledge that men too, can be victims of IPV, with women as the perpetrators. For the purpose of this article however, we will only focus on the perspective of pregnancy avoidance and women as victims.

Given the large number of unplanned pregnancies in the United States, it is imperative to better understand how the decision and ability to use condoms and oral contraceptives, specifically as both require daily action or action for each sexual encounter and therefore can be subject to partner interference, factor into relationships where IPV is present. The rationale for linking these issues is articulated in the review by Coker on the effect of IPV on women’s sexual health.[6] Specifically, Coker presents a mechanism linking IPV to unplanned pregnancy via multiple factors including contraceptive use.[6] Although linkages between IPV and unplanned pregnancy have been established in the literature, understanding intermediate variables (e.g., contraceptive use negotiation, sexual relationship power dynamics, reproductive coercion) that contribute to lack of condom and oral contraceptive use is necessary to develop more targeted interventions to improve more proximal (i.e., reductions in IPV victimization and perpetration, increased condom and oral contraceptive use) and distal outcomes (e.g., unplanned pregnancy, STIs) for women. Because of this, we conducted a systematic review to assess this pathway and to explore intermediate variables between IPV and condom and oral contraceptive use (hereafter referred to as contraceptive use). We undertook this review to explore this pathway at two preselected levels, that of the victim and that of the perpetrator. The first focuses on the female victim’s perspective on barriers to contraceptive use, in conjunction with experiencing IPV. The second level highlights the male perpetrator’s perspective regarding contraceptive use. Within these two foci, we then sought to investigate the clustered themes that emerged. The goal of this review is to attempt to identify and better understand the many factors affecting contraceptive use in relationships with IPV, with the intent of helping to inform intervention development in clinical settings.

2. METHODS

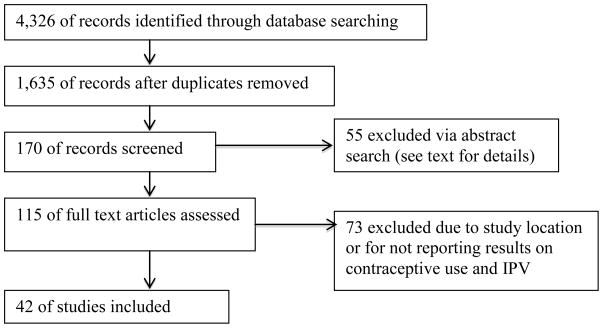

A systematic approach was used to identify all original research addressing the association between IPV and contraceptive use among women in the United States. We define IPV as physical and/or sexual violence of a female by a current or former male intimate partner and contraceptive use as the use of condoms or oral contraceptives. We developed our conceptual framework based off of Coker’s mechanism,[6] highlighting two themes that emerged from IPV and led to reduced contraceptive use: condom use negotiation and reproductive coercion (see Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Adapted from Coker’s review[6]

2.1 Study Inclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: a) focused on physical and/or sexual IPV or on the fear of experiencing physical and/or sexual violence and b) included contraceptive use in their analysis. Because we were interested only in the relationship between IPV and contraceptive use, articles that focused on violence perpetrated by a non-intimate partner were excluded. Further, because we were interested in only assessing contraceptives that required daily action or action for each sexual encounter, specifically meaning male condoms or female oral contraceptives, we excluded the inclusion of all other forms of contraception. As little has been published on the linkages between IPV and contraceptive use, no limits were imposed on the timeframe for the article inclusion criteria. For similar reasons, quantitative, mixed method, and qualitative studies were eligible for inclusion in the review; however, intervention-based studies were not. Only articles written in English and studies conducted in the United States were included in the final assessment.

2.2 Data Sources

This review included peer-reviewed articles from the following databases: Pubmed, PsychInfo, Eric, and Popline. To identify IPV, the following search terms were used: “violence”, “abuse”, “partner violence”, “partner abuse”, “sexual abuse”, “physical abuse”, “pregnancy coercion”, “birth control sabotage”, and “reproductive coercion”. Searches were performed in the titles, subjects, abstracts, and keywords for all manuscripts in these databases. Similar searches were performed to identify contraceptive use; search terms used were “contraceptive use”, “birth control”, “unprotected sex”, “condom use”, and “condom use negotiation”.

2.3 Study Selection

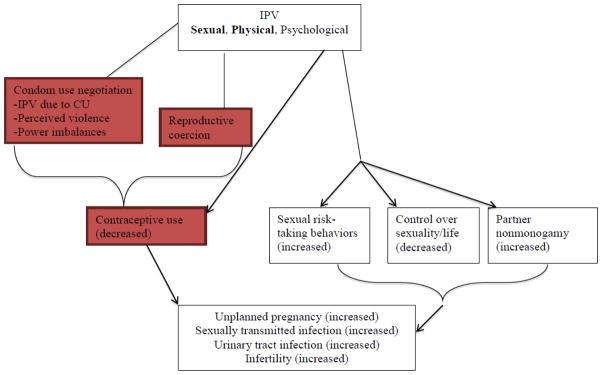

A total of 4,326 manuscripts were identified in the database searches, which were completed in December 2014. After removing duplicates, 1,635 articles remained.2 Following a title review, in which the title had to include some variation of partner violence (including terms for domestic, interpersonal, and gender violence, coercion, partner barriers/negotiation), and removing any articles not in English, 170 remained. After reviewing the abstracts of the remaining articles specifically for the inclusion of partner violence, reproductive coercion and contraceptive use, the authors excluded an additional 55 articles, leaving 115. This process included discussions between the authors regarding article selection. Of the remaining articles, 57 did not focus primarily on the United States and were removed. Finally, reviewing the remaining articles at length, 16 did not report results on contraceptive use and were removed, leaving 42 articles that addressed IPV and contraceptive use.

Upon identifying the articles eligible for inclusion, the authors then read through each of the papers, searching for and identifying key themes. This was an iterative process that required reading through each paper multiple times to identify cross-emerging themes between all the papers. Once the themes were identified and agreed upon by both authors, articles were then grouped under these themes. The authors discussed any articles not clearly falling into only one theme to decide best how to categorize the paper. The following are the results of this effort.

3. RESULTS

A total of 42 articles were identified as eligible for inclusion in this review. We identified 37 articles for Aim 1 (female victim’s perspective on barriers to contraceptive use, in conjunction with IPV) and grouped these into three themes that emerged across the studies: violence resulting in reduced contraceptive use; condom use negotiation, subcategorized as IPV due to contraceptive request, perceived violence (or fear) of IPV resulting in decreased contraceptive use, and sexual relationship power imbalances decreasing the ability to use contraceptive use; and reproductive coercion. We then identified an additional 5 articles for Aim 2 (male perpetrator’s perspective regarding contraceptive use).

Studies included in Aims 1 and 2 were first organized by type of research design (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods). Then studies in Aim 1 were assessed for factors impacting contraceptive use in IPV relationships and categorized by the themes that emerged across the studies. The Results section is organized by aim (i.e., female victimization perspective, male perpetration perspective), and within Aim 1, by key findings. It is important to note that although our inclusion criteria allowed for both condom and oral contraceptive use, only two articles (with the exception of those for reproductive coercion) reported on oral contraceptive use.[7,8] Tables 1–4 summarize the study design, study sample, measures assessed, results, and limitations. The studies are arranged alphabetically by the first author’s last name.

Table 1.

Studies focused on the relationship between IPV and reduced contraceptive use

| Author, Year | Study Design | Study Sample | Measures | Primary Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies | |||||

| Bogart, et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional; secondary analysis | 726 sexually-active individuals in three gender/orientation groups (286 women, 148 heterosexual men, and 292 gay/bisexual men)/HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study |

|

|

Unable to infer causality; and potential self-reporting bias |

| Cavanaugh, et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional; secondary analysis | 555 Latina women who were currently seeking or receiving services for a recent incident of physical abuse or threatening behavior by an intimate partner were recruited in one major city on the East Coast and one West Coast county/Risk Assessment Validation (RAVE) Study |

|

|

Cultural implications for generalizability |

| Fair, et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional; survey | 148 undergraduate college students from southeast United States recruited via email rosters |

|

|

Low response rate to the survey (small sample size); few male participants; unknown sexual orientation of participants |

| Gielen, et al., 2002 | Cross-sectional; survey | 445 women (188 HIV+ and 257 HIV−) in intimate relationships, living in low-income, urban neighborhoods in Baltimore |

|

|

Potential for self-report bias and inaccurate reporting about partners’ behaviors |

| Hess, et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional; secondary analysis | 3548 women (18–28 years) who reported on a sexual relationship that occurred in the previous 3 months/Wave 3 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health |

|

|

Potential for social desirability bias; no context about violence (i.e., who initiated it) |

| Mittal, et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional; ACASI survey | 717 women (18+ years) were recruited from a public STD clinic in upstate New York as part of a randomized controlled trial |

|

|

Measures used to assess IPV were brief; more detailed measures might have better assessed the construct of partner violence; potential for under-reporting |

| Mittal, et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional; ACASI survey | 717 women (18+ years) from a public STD clinic in upstate New York as part of a randomized controlled trial |

|

|

Low power (due to moderate sample size) to detect effects of multi-group comparisons |

| Panchanadeswaran, et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional; survey | 244 heterosexual drug-using women from venue-based sampling of 38 New York City neighborhoods |

|

|

Non-random sample; self-reporting biases |

| Roberts, et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional; secondary analysis | 973 sexually active, dating female adolescents/Wave II of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health |

|

|

Narrow definition of abuse; reliability of responses; unable to assess causality |

| Scribano, et al., 2012 | Longitudinal ; Prospective analysis | 10,855 participants were included in this study over the time period of 2002–2005 were identified using the Nurse Family Partnership Program Computerized Information System |

|

|

Physical IPV was the only form of violence under study in the present investigation. |

| Silverman, et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional; survey | 356 females (14–20 years) who attended adolescent health clinics in Greater Boston |

|

|

Generalizability is limited; potential self-reporting bias; inability to determine the temporality of sexual risk behaviors versus occurrence of IPV (causality) |

| Stockman, et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional; ACASI survey; case control analysis | 668 Black women (18–55 years) from women’s health clinics in Baltimore, MD, USA and St. Thomas and St. Croix, US Virgin Islands |

|

|

Question structure limited response options; causality could not be assessed; and limited understanding of the context of sexual risk behaviors |

| Teitelman, et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional; secondary analysis | 2,058 sexually active young adult women/ waves II and III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health |

|

|

Unable to distinguish the impact of recent abuse versus current abuse in partner relationships, therefore, did not know if nonuse or inconsistent use of condoms in the past year was potentially related to abuse from the same sexual partner or from a different or previous relationship. |

| Tucker, et al., 2004 | Prospective analysis | 898 women (460 sampled from shelters, 438 sampled from low-income housing) from central region of LA Country |

|

|

Less-than-optimal internal reliability for measures |

| Williams, et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional; case control analysis | 225 women from clinics in the Boston area, 115 abused women and 110 control women |

|

|

Small sample size and low power to make comparisons; inability to determine causal direction |

Table 4.

Studies Examining Male IPV Perpetrator Perspective and Contraceptive Use

| Author, Year | Study Design | Study Sample | Measures | Primary Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies | |||||

| Frye, et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional; survey | 518 heterosexual men recruited via street-intercept in New York City |

|

|

Self-report and social desirability bias; unable to assess temporal relationship between IPV and condom use (causality issues) |

| Neighbors, et al., 1999 | Cross-sectional; survey | 100 participants from a county jail in central New Jersey |

|

|

Potential for social desirability responding; hypothetical questions only, did not evaluate situations and actual responses |

| Raj, et al., 2006 | Cross-sectional; survey | 283 sexually active men (18–35 years) who visited an urban community health center and who reported having sexual intercourse with a steady female partner during the past 3 months |

|

|

Inability to assess causality; self-reporting biases; generalizability issues |

| Raj, et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional; survey | 631 heterosexual African American males (18–65 years) who reported two or more sex partners in the past year from urban health clinics in northeastern US |

|

|

Inconsistent timeframes for substance abuse and IPV; inability to assess causality; self-reporting biases |

| Qualitative Study | |||||

| Raj, et al., 2007 | Qualitative; semi-structured interviews | 19 adolescent males from intervention programs for adolescent perpetrators of dating violence |

|

|

Small sample size; self-reporting biases |

3.1 Aim 1: Female Victimization Perspective

3.1.1 IPV and reduced contraceptive use

The literature clearly demonstrates that IPV can lead to a reduction in contraceptive use. We identified 15 studies that reported on this association, all of which were quantitative in design (refer to Table 1 for complete results).3

3.1.1.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

Thirteen of the 15 studies were cross-sectional; the remaining two were longitudinal.[9,10] Five studies utilized pre-existing datasets.[7,11–14] A variety of measures were used to assess the impact of IPV on contraceptive use. Most studies measured IPV through the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) or the revised version of the scale (CTS-2)[7,8,10,12–14,18–21]; Scribano, et al.[9] and Stockman, et al.[17] assessed IPV through the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS), Stockman, et al.[17] also used the Severity Violence Against Women Scale (SVAWS). Contraceptive use was primarily measured through self-report of condom use during last sex act and frequency of condom use during a specific timeframe, which varied by study (e.g., past 3 months, past year).

3.1.1.3 Findings

All of the studies found significant positive associations between IPV and contraceptive use. IPV was found to increase the number of unprotected sexual encounters in all studies. Four studies also assessed the association between IPV, substance abuse and contraceptive use, and found that in conjunction with IPV, substance abuse decreased the use of contraception.[10,11,18,19] Interestingly, Tucker, et al. found this to be true only for alcohol use; drug use was instead positively associated with condom use.[10]

3.1.2 Contraceptive use negotiation

Condom use negotiation is one pathway we identified from the literature that connects IPV to reduced contraceptive use (see Figure 1). Within this we found three distinct subcategories: IPV due to contraceptive request, perceived violence impacting one’s ability to use contraception, and sexual relationship power imbalances affecting contraceptive use. We would like to note that the reason behind the request for contraceptive use is not clear from the studies (i.e., if requested to prevent pregnancy or STI transmission).

3.1.2.1 IPV due to contraceptive request

IPV due to a woman’s request to use contraception occurs in some relationships and has been explored in the literature. We reviewed 2 articles that focused on IPV as a factor influencing contraceptive request, one was quantitative, while the other was qualitative in design.4

3.1.2.1.1 Quantitative Study

Lang, et al. used quantitative methods (convenience sampling).[22] Participants were recruited from clinics providing care for HIV-positive women. Gender-based violence was assessed through two self-reported measures: physical abuse in past 3-months, and sexual abuse in past 3-months. Condom use was assessed through self-report of use during last sex act and frequency of condom use during past 3-months.

Lang, et al. found that physical abuse was 8 times more likely to result when women request the use of condoms with their intimate partners than those who did not. Additionally, women who experienced recent gender-based violence and who had asked their partner to use a condom were 14 times more likely to experience physical abuse than those who did not negotiate condom use. These results should be viewed with caution, as the findings are not generalizable due to the selective nature of the study population.

3.1.2.1.2 Qualitative Study

Davila, et al. used in-depth interviews to collect data.[23] The study included only women who self-identified as Mexican or Mexican American and focused on self-report of participant knowledge of HIV/AIDS and condom use knowledge and experiences; the demographic survey however, did assess domestic violence indicators through the Domestic Violence Assessment Form.

Davila, et al. concluded that physical abuse could result when women request the use of condoms with their intimate partners. Their study also revealed that women believed the causes of this violence were their partners’ beliefs that a condom request was a breach of trust and indicated that either the women had been unfaithful, or that they thought that the male partner had been. Although these findings are not generalizable due to the selective nature of the study population, this study does highlight an understudied minority population and illuminates factors they perceive between IPV and contraceptive use.

3.1.2.2 Perceived violence limiting women’s ability to negotiate contraceptive use

The relationship between contraceptive use and a perceived, or an actual, threat of violence has been explored in the literature. We reviewed 6 articles that explored this association (refer to Table 2). Four of the articles were purely quantitative studies, while the other two were mixed methods.

Table 2.

Studies focused on IPV and contraceptive use negotiation

| Author, Year | Study Design | Study Sample | Measures | Primary Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPV Due to Contraceptive Request | |||||

| Quantitative Study | |||||

| Lang, et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional; survey | 304 seropositive women from HIV clinics in the southeastern United States |

|

|

Self-report biases; did not assess severity and frequency of abuse; causality limitations |

| Qualitative Study | |||||

| Davila, et al., 1999 | Qualitative; semi-structured interviews | Convenience sample of 14 Mexican and Mexican American women recruited from a battered women’s shelter |

|

|

Small sample size; and generalizability issues |

| Perceived Violence Limiting Women’s Ability to Negotiate Contraceptive Use | |||||

| Quantitative Studies | |||||

| Agrawal, et al., 2014 | Prospective analysis; survey | 1,047 women (14–25 years) from two university affiliated OBGYN clinics, one in New Haven, CT, the other in Atlanta, GA, that serve low-income, minority women |

|

|

Self-report biases; not generalized to US population |

| Decker, et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional; survey | 3,504 women (16 – 29 years) seeking care at 1 of 24 free-standing title×family planning clinics in western Pennsylvania |

|

|

Self-report biases; social desirability biases; and recall biases |

| Mittal, et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional; survey | 103 predominantly low-income, urban women receiving services from domestic violence agencies in New York |

|

|

Relied on victims’ self-reports of partner-related risk behaviors which may not align with actual behaviors; no causal inferences |

| Wingood, et al., 1997 | Cross-sectional; survey | 165 women (18–29 years) from the Bayview-Hunter’s Point neighborhood of San Francisco, CA, a predominantly lower socioeconomic level African-American community |

|

|

Self-reports of partner abuse may under or overestimate actual partner abuse. The study did not measure the severity of abuse to determine whether there was a relationship between that and condom use. |

| Mixed Method Studies | |||||

| Kalichman, et al., 1998 | Mixed methods; cross-sectional, survey, and qualitative focus groups | 125 African-American women living in low-income housing developments in Fulton County, Georgia |

|

|

Potentially unclear measures for participants to respond to; did not link sexual and coercive experiences/behaviors to specific relationships, therefore can’t determine the relationship |

| Teitelman, et al., 2011 | Mixed methods; cross-sectional, survey, and qualitative focus groups | 64 adolescent African-American girls (14–17 years) who attended family planning or prenatal clinics in a northeastern city, Philadelphia |

|

|

Small sample size |

| Power Imbalances/Self-Efficacy in a Relationship | |||||

| Quantitative Studies | |||||

| Beadnell, et al., 2000 | Cross-sectional; survey | 167 women who reported having a steady sexual partner in the previous 4 months from pre-intervention surveys in an ongoing longitudinal study |

|

|

Questionable generalizability; and asked participants to infer about partner’s behaviors which may differ from actual behaviors |

| Bonacquisti, et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional; survey | 90 women from a domestic violence shelter, a domestic violence support organization and an obstetrics/gynecology clinic in Philadelphia, PA |

|

|

Convenience sample limits generalizability; the assessment measures were administered in an independent self-report format, which may reduce precision in responses; and potential for self-response biases |

| Swan, et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional; survey | 118 incarcerated females (19+ years) from Delaware, Kentucky, and Virginia prisons |

|

|

Factors that may be involved in predicting condom use self-efficacy and that are also correlated with IPV were not included in the model because they were not available in this data set; and measures of emotional abuse on condom use self-efficacy were not available |

| Teitelman, et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional; survey | 59 sexually active teenage girls (15–19 years) from clinics and community sites in medium size urban areas in Michigan. |

|

|

Small sample size |

| Qualitative Studies | |||||

| East, et al., 2011 | Qualitative; interviews | 10 women’s stories were collected via online interviews in 2007 |

|

|

Small sample size; limited by the requirement that participants be able to communicate fluently in English |

| Lichtenstein, 2005 | Qualitative; in-depth interviews and focus groups | 50 women from a large public clinic in Alabama that provides medical and social support services HIV-positive persons in a 23 county area in south Alabama |

|

|

Small sample size; reporting biases; and generalizability issues |

| Rosen, 2004 | Qualitative; open-ended interviews | 35 teenage mothers recruited from an adolescent health clinic in a small city in Michigan |

|

|

Small sample size; and generalizability issues |

3.1.2.2.1 Quantitative Studies

3.1.2.2.1.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

All studies were cross-sectional in nature and either gathered information through audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) techniques[24–26] or through face-to-face structured interviews[27]. Each study used different scales to assess IPV as an independent variable (refer to Table 2). Contraceptive use assessed as frequency of condom use was measured during different intervals for each study (previous 3 months[24,25,27] or previous 30 days[26]).

3.1.2.2.1.2 Findings

All 4 studies found that a woman’s perception or fear of potential violence can limit her ability and confidence in condom use negotiation. Wingood, et al. found that women who had a physically abusive partner were 6.5 times more likely to fear physical abuse and 9.2 times more likely to be threatened with physical abuse as a direct result of negotiating condom use than women without an abusive partner.[27] Agrawal, et al. found that women who experienced emerging and/or repeated postpartum IPV had increased fear of condom use negotiation (p<0.001).[26] Decker, et al. found that women in recent abusive relationships were more likely to report fear of condom requests (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 4.15, 95% CI 2.73–6.30).[25] Mittal, et al. reported similar findings, that women who engaged in sexual risk behaviors (which included inconsistent condom use), were more likely to fear abuse during condom use negotiation and that as fear increased, the odds of sexual risk behaviors also increased (AOR 1.06, 95% CI, 1.00–1.12).[24] Although this finding supports the previous conclusions, it must be interpreted with caution as sexual risk behaviors included not only inconsistent condom use, but also having multiple sexual partners or having been diagnosed with an STD. As such, it is not possible to ascertain the exact relation to contraceptive use in this study.

3.1.2.2.2 Mixed Methods Studies

The mixed methods studies included women completing a survey and participating in either an AIDS information focus group[28] or a focus group regarding unhealthy relationships[29]. Kalichman, et al. used the Sexual Experiences Survey to assess sexual coercion and then asked participants to self-report on questions regarding physical violence.[28] Teitelman, et al. asked three close-ended questions to assess verbal, threatening, and physical partner abuse.[29] Contraceptive use was measured by frequency of condom use in either the previous 2 weeks,[28] or as condom use at last sex act[29].

Both studies found that a woman’s perception or fear of potential violence can limit her ability and confidence in condom use negotiation. Kalichman, et al. found that sexually coerced women (i.e., women forced to have sex against their wishes) were more likely to be afraid to negotiate condom use due to fear of resulting physical abuse (p<0.01).[28] Teitelman, et al. reported findings that adolescent girls who feared requesting the use of a condom could be limited in their ability to request and/or use a condom.[29]

3.1.2.3 Sexual relationship power imbalances/self-efficacy in a relationship and condom use negotiation

Power within a relationship, specifically its imbalance between sexual partners, can impact a woman’s ability to successfully negotiate condom use as well as her control over sexual activities. Sexual relationship power in these studies as outlined by Bonacquisti, et al.[30] “is a construct that characterizes power differentials between intimate partners, encompassing relationship dynamics such as trust, commitment, infidelity, decision-making and condom use negotiation”. We found 7 studies that pertained to this theme (refer to Table 2), four of which were quantitative, and three qualitative in design.

3.1.2.3.1 Quantitative Studies

3.1.2.3.1.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

All 4 quantitative studies were cross-sectional.[30–33] Violence in intimate relationships was measured differently for each study (refer to Table 2). Condom use practices and/or confidence in condom use negotiation were assessed in all 4 of the studies, again through study specific questions. One study addressed sexual relationship power imbalances in intimate relationships through beliefs in “traditional” gender roles[31], another through self-confidence as assessed by study specific measures[32], and the remaining two assessed sexual relationship power imbalances through the Sexual Relationship Power Scale[30,33].

3.1.2.3.1.2 Findings

Each study found that power imbalances within a sexual relationship have a significant impact on a woman’s ability to negotiate condom use. Beadnell, et al. found that women who believed in more traditional gender roles were less likely to have a say about safe sex and associated condom use.[31] Moreover, physically abused women were more likely to believe their partners had more say about condom use; the women also had lower self-efficacy in condom use negotiation. Teitelman, et al. found that adolescent girls who had less power in a relationship, which equated to more abuse, had more inconsistent condom use.[33] Teitelman, et al. also found that increased sexual control, or power imbalances in a sexual relationship, resulted in decreased IPV (p=0.001).[33] Swan, et al. found that women who experience IPV have lower levels of condom use self-efficacy than those who do not experience IPV (p<0.01).[32] They further concluded that IPV decreases women’s abilities to negotiate condom use. Finally, the study by Bonacquisti, et al. supported these conclusions and reported that condom use significantly differed by level of sexual relationship power (p=0.042).[30]

3.1.2.3.2 Qualitative Studies

3.1.2.3.2.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

Three studies were qualitative in design and used in-depth interviews and/or focus groups to gather data; one conducted interviews via an online system[34], while the others conducted them face-to-face[35,36]. Two of the qualitative studies specifically indicated that they assessed violence in intimate relationships through open-ended questions[35,36], while the other assessed condom use practices and/or confidence in condom use negotiation[34]. Two studies addressed power imbalances in intimate relationships and/or beliefs in gender roles[35,36]

3.1.2.3.2.2 Findings

The studies found that sexual relationship power imbalances have a significant impact on a woman’s ability to negotiate condom use. Lichtenstein found that women in a relationship with an HIV-positive abusive partner lacked the ability (or power) to negotiate sex and condom use; this inability was enforced through forced sex and sexual ownership, which was expressed through threats, violence, name-calling and isolation.[35] Rosen found that male partners generally made birth control decisions and that adolescent girls did not attempt to negotiate issues relating to sex and birth control for the purpose of preventing confrontations and avoiding potential violence.[36] East, et al. reported that if women wanted to practice safer sex, the gender dynamics within a relationship could prevent condom negotiation and use.[34]

3.1.3 Reproductive coercion and IPV

Reproductive coercion is a relatively underexplored occurrence in the literature, although directly relevant to a woman’s ability to successfully use contraception. It is defined as “male partners’ attempts to promote pregnancy in their female partners through verbal pressure and threats to become pregnant (pregnancy coercion) or direct interference with contraception (birth control sabotage).”[37] We identified 7 studies that addressed reproductive coercion as it relates to IPV, three of which were quantitative and the remaining four were qualitative in design.5

3.1.3.1 Quantitative Studies

3.1.3.1.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

All studies were cross-sectional in design.[38–40] Two of the three employed ACASI to interview participants[39,40], while the other used self-administered paper surveys[38]. All of the studies assessed experiences with IPV and used the same measures to assess both pregnancy coercion (i.e., threatening to harm a woman physically or psychologically if she did not agree to become pregnant) and birth control sabotage (i.e., flushing oral contraceptive pills down the toilet, intentionally breaking or removing condoms, or inhibiting a woman’s ability to obtain contraception).[38–40] These measures were developed in the Miller, et al.[39] study and included six self-report questions to assess pregnancy coercion and five self-report questions to assess birth control sabotage. In addition to pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage, the studies also assessed IPV; two used the CTS to assess this[39,40], while another used the AAS[38].

3.1.3.1.2 Findings

Reproductive coercion, specifically, pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage were reported in each of the studies. Three of the studies assessed the relationship between birth control sabotage, pregnancy coercion and IPV.[38–40] Miller, et al. found significant levels of IPV within reproductive coercion; 79% of women experiencing birth control sabotage also experienced IPV, while 74% who experienced pregnancy coercion also reported IPV.[39] Clark, et al. had more modest findings in that 47% of women who experienced birth control sabotage also experienced IPV, while 34% who experienced pregnancy coercion also experienced IPV.[38] Miller, et al. found that reproductive coercion happened both in the presence and absence of IPV, with the end result being pregnancy.[40] Specifically, women who were exposed to some form of recent reproductive coercion (past 3-months) had an increased odds of past-year unintended pregnancy, both in the absence of a history of IPV (AOR 1.79, 95% CI, 1.06–2.03) and in combination with a history of IPV (AOR 2.00, 95% CI, 1.15–3.48).[40]

3.1.3.2 Qualitative Studies

3.1.3.2.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

All of the qualitative studies used in-depth interviews to collect data and assessed experiences with IPV through open-ended questions.[41–44]

3.1.3.2.2 Findings

Reproductive coercion, specifically, pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage were reported in each of the studies. All 4 studies focused on themes related to birth control sabotage, reporting that women’s partners prevented them from obtaining or disposing of oral contraceptives, sabotaged or inconsistently used condoms, or failed to withdraw during sex.[41–44] Moore, et al.[44] also found pregnancy coercion for the purpose of tying the female victim to her male partner forever to be a resounding theme in the interviews.

3.2 Aim 2: Male perpetrator perspective and contraceptive use

Few articles (n=5) in the literature actually address the male perpetrator perspective of IPV and its relation to contraceptive use (refer to Table 4).6 Of these 5 studies, only one was qualitative in design.[49]

3.2.1 Quantitative Studies

3.2.1.1 Study Design and IPV/Contraceptive Use Measures

All studies were cross-sectional and collected data through surveys.[45–48] One study used ACASI to interview participants.[48] Three of the studies used similar measures to assess IPV perpetration, specifically the CTS-2.[45–47] Three studies assessed consistent condom use and unprotected sex through self-report.[45,46,48]

3.2.1.2 Findings

All 4 studies reported direct links between male IPV perpetration and condom use.[45–48] Neighbors, et al. found that perpetrators of IPV were more likely to negatively view condom requests from a main partner resulting in further coercive behaviors.[47] Raj, et al. found that IPV perpetrators were more likely to report inconsistent or no condom use during vaginal sexual intercourse (AOR 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–4.9).[45] Additionally, IPV perpetrators were 5.2 times more likely to report forcing sexual intercourse without a condom in the past year than non-IPV perpetrators (95% CI, 2.5–10.9).[45] Similarly, Raj, et al. found in a crude analysis an association between IPV perpetration and unprotected penile–vaginal sex (OR 1.7, 95% CI, 1.1–2.6).[48] Frye, et al. supported this; they found that men who perpetrated violence against their main female partners were 49% less likely to use condoms consistently with these partners (95% CI, 0.27–0.86).[46]

3.2.2 Qualitative Study

One study was qualitative and conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews to collect information.[49] The study did not directly link IPV perpetration behaviors to condom use, instead evaluating each separately in the study. Raj, et al. found that male perpetrators inconsistently used condoms in their steady relationships, even if they were involved in a concurrent relationship.

4. DISCUSSION

We reviewed the literature to determine the extent of research that exists linking IPV and contraceptive use. From the studies, it was apparent that there were several IPV-related factors that greatly influenced a woman’s ability to use contraception. Specifically, the use of violence against her eliminated the opportunity to choose to use contraception; experiencing violence due to a contraceptive request made women less likely to request the use of contraception at a later date; the fear of violence that may result due to contraceptive request reduced women’s ability to use contraception; and sexual relationship power imbalances and a lack of self-efficacy in an intimate relationship resulted in women not believing they could ask to use or use contraception.

The studies reported that a significant number of women experienced reproductive coercion either in the form of birth control sabotage or pregnancy coercion, which limited their contraceptive efficacy. With birth control sabotage, women may have believed they were using contraception, while in actuality their partners either were not using condoms or had sabotaged the condoms. Male partners also removed access to oral contraceptives either through disposing of pills or not allowing women to purchase pills, which eliminated a woman’s ability to access contraception. Finally, male partners used pressure (i.e., pregnancy coercion) to get women pregnant (e.g., through threats of abandonment, etc.), which also eliminated a woman’s uninhibited choice to use contraception.

One result that was readily apparent from this review was the lack of published research on the use of oral contraceptives in conjunction with IPV. Given that 28% or 10.6 million women of reproductive age (aged 15–44), who use contraception, reported using oral contraceptives, there is a significant dearth in information for this subpopulation.[4] It is imperative that additional research examining the connection between oral contraceptives and IPV be conducted and examined as any interventions developed for this group would fundamentally differ from those who report on condom use (i.e., intervention on negotiating use before every sexual encounter would not be relevant).

Moreover, we identified six articles that addressed the male perspective (or perpetrator perspective) solely. Although women’s perspectives are essential in any discussion surrounding IPV and contraceptive use, male insight is crucial to intervention development and understanding why such behaviors occur. Additionally, there was a substantial lack of research surrounding the male perspective in reproductive coercion (specifically what motivations are behind the occurrence and why it occurs). This lack of understanding inhibits intervention development targeted towards men to reduce these experiences among women. Moving forward, more emphasis should be placed on including the male perpetrator perspective both for understanding the occurrence of these behaviors and specifically for the development of more targeted interventions.

Previously, a limitation of such studies was the lack of qualitative information to characterize IPV and condom use, as they instead were designed to only quantitatively assess factors surrounding IPV. This review found that this trend has shifted, as eleven of the 42 articles were qualitative in nature (two of which utilized a mixed methods approached). This new dimension in the research has allowed for a better understanding of the gendered dynamics of relationships that experience IPV, specifically sexual relationship power imbalances and self-efficacy factors. More research using qualitative methods is needed however, in order to provide additional illumination on the complexity of these issues as well as recommendations regarding potential prevention techniques. Additionally, five of the studies used population-level samples to perform secondary analysis, which increases the generalizability of their results.

Despite identifying several strengths in the studies, there were limitations found in most of the studies. Nearly all of the studies were cross-sectional in design (n=28); only three were prospective. The nature of cross-sectional study designs limits our ability to determine the temporal nature of IPV and contraceptive use. As such, more studies are needed to not only describe this relationship qualitatively (as previously stated), but also more longitudinal studies are needed to assess causal implications. Further, although many of the studies used the same measures for IPV, definitions or rating scales differed. This made examining outcomes across studies problematic. Consistency in both measurement and definitions need to be implemented to create a greater impact in the literature. Additionally, many of the studies grouped types of violence (i.e., physical, sexual) into one category when assessing contraceptive use outcomes. This made teasing out the extent to which a specific type of violence impacted contraceptive use difficult, and in many cases impossible. Moreover, studies reporting on contraception or condom request did not specify the reason behind this request (e.g., prevention of HIV or STI transmission, or prevention of pregnancy). Additional research is needed to fully understand why contraceptive requests are made before fully understanding the perceived or resulting violence. It is possible that the contraception request (specifically condoms) was to prevent STI transmission rather than pregnancy. None of the studies addressed this issue. Finally, very little research exists surrounding reproductive coercion. More studies need to focus on this topic to create a better understanding of it and to identify ways to prevent it from occurring.

As ample studies have been conducted to assess the association between IPV and contraceptive use, the implications of these studies are far reaching and should behoove researchers to apply these results to design more interventions. In doing so, these interventions could be used to further support how to improve contraceptive use negotiation skills and to reduce pregnancy coercion, and also could be designed to address some if not all of the themes found in this review (e.g., IPV perpetration, perception of violence, sexual relationship power imbalances/self-efficacy in intimate relationships, etc.). Although not assessed in this review, we would like to highlight that the full spectrum of IPV and reproductive coercion can include forced abortion rather than the reviewed counterfactual. This too should be taken into account when designing interventions. Moreover, interventions that are tailored to specific structural and relational context of different populations may have a larger impact for those at greater risk for IPV perpetration.[50] Finally, as shown in this review, the voices of perpetrators are often neglected when attempting to understand IPV and contraceptive use; however, their view has the potential to be illuminating and help researchers and practitioners identify root causes of violence and how to prevent it from (re)occurring. As such, involving males in interventions has the potential to greatly reduce IPV.

Family planning and gynecology clinical encounters provide important opportunities to screen for both IPV and reproductive coercion.[51] Because of the connection between reproductive health and violence, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggests that “health care providers should screen women and adolescent girls for intimate partner violence and reproductive and sexual coercion at periodic intervals.”[51] There are many successful examples of screening for IPV, but universal screening of all patients in clinical encounters or a form of screening during every visit could identify and provide assistance to more women in potentially harmful situations. Further, from the literature, screening for reproductive coercion appears to be less common, although would prove to be effective in assisting women experiencing reproductive coercion.[51] Screening for this among high-risk populations and women who seek emergency contraception multiple times could provide additional insight into why barriers to contraceptive use exist. Organizations that are attempting to raise awareness about reproductive coercion both with individuals as well as through medical practitioners include Futures Without Violence and Planned Parenthood. They are attempting to transform reproductive health care and improve responses to women facing abuse. If more organizations pushed for the adoption of similar practices during gynecological care, more cases could be identified and prevented from reoccurring.

Figure 2.

Flowchart depicting selection criteria

Table 3.

Studies examining reproductive coercion and IPV

| Author, Year | Study Design | Study Sample | Measures | Primary Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies | |||||

| Clarke, et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional; survey | 641 women (18–44 years) presenting for routine obstetrics and gynecology care at a large obstetrics and gynecology clinic |

|

|

Causality could not be determined; and the standard intimate partner violence (IPV) screening tool did not include a question about threatening behavior, so the full range of emotional abuse was not queried |

| Miller, et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional; survey | 1278 females (16–29 years) seeking care in five family planning clinics in Northern California |

|

|

Measures of lifetime prevalence prevent any temporal ordering among pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage and IPV with unintended pregnancy. |

| Miller, et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional; survey | 3539 women (16–29 years) seeking care in 24 rural and urban family planning clinics in Pennsylvania |

|

|

Causal inferences regarding the associations observed among recent reproductive coercion and past-year unintended pregnancy cannot be inferred. Reproductive coercion assessment referred only to the past 3 months, while unintended pregnancy was assessed in the past year. |

| Qualitative Studies | |||||

| Miller, et al., 2007 | Qualitative; semi-structured interviews | 53 women (15–20 years) from confidential adolescent clinics, domestic violence agencies, schools, youth programs for pregnant/parenting teens, and homeless and at-risk youth, all located in low-income neighborhoods within a major metropolitan area |

|

|

Small sample size; and potential for self-reporting bias |

| Miller, et al., 2012 | Qualitative; open ended interviews | 20 women (18–35 years) with known histories of gang involvement from a large gang intervention program in Los Angeles, CA |

|

|

Small sample size; and potential for self-reporting bias |

| Moore, et al., 2010 | Qualitative; semi-structured, interviews | 71 women (18–49 years) with IPV history from a domestic violence shelter, freestanding abortion clinic, and family planning clinic in metropolitan areas |

|

|

Self-reporting bias; results not generalizable |

| Thiel de Bocanegra, et al., 2010 | Qualitative; in-depth interviews | 53 women at four domestic violence shelters located in the San Francisco Bay Area |

|

|

Small sample size; and potential for self-reporting bias |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K01DA031593, R01HD077891, and L60MD003701).

Footnotes

Figure 2: Flowchart depicting selection criteria

Table 1: Studies focused on the relationship between IPV and reduced contraceptive use

Table 2: Studies focused on IPV and contraceptive use negotiation

Table 3: Studies examining reproductive coercion and IPV

Table 4: Studies Examining Male IPV Perpetrator Perspective and Contraceptive Use

6. COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) [accessed December 21, 2013];Intimate partner violence: Facts. 2002 http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/en/ipvfacts.pdf.

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) [accessed March 18, 2014];Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. 2010 doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029629. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564007/en/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [accessed December 21, 2013];NISVS: An Overview of 2010 Summary Report Findings. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_overview_insert_final-a.pdf.

- 4.Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current Contraceptive Use in the United States, 2006–2010, and Changes in Patterns of Use Since 1995. [accessed March 13, 2014];Natl Health Stat Report. 2010 :60. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr060.pdf. [PubMed]

- 5.Mosher M, Jones J, Abma J. Intended and Unintended Births in the United States: 1982–2010. [accessed March 13, 2014];Natl Health Stat Report. 2010 :55. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr055.pdf. [PubMed]

- 6.Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8(20):149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts T, Auinger P, Klein J. Intimate partner abuse and the reproductive health of sexually active female adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(5):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams M, Larsen U, McCloskey L. Intimate partner violence and women’s contraceptive use. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(12):1382–1396. doi: 10.1177/1077801208325187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scribano P, Stevens J, Kaizar E. The effects of intimate partner violence before, during, and after pregnancy in nurse visited first time mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(2):307–318. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker J, Wenzel S, Elliot M, et al. Interpersonal violence, substance use, and HIV-related behavior and cognitions: A prospective study of impoverished women in Los Angeles County. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(4):463–474. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogart L, Collins R, Cunningham W, et al. The association of partner abuse with risky sexual behaviors among women and men with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(3):325–333. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanaugh C, Messing J, Amanor-Boadu Y, et al. Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: A Comparison of Foreign-Versus US-Born Physically Abused Latinas. J Urban Health. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess K, Javanbakht M, Brown J, et al. Intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted infections among young adult women. J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(5):366–371. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182478fa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teitelman A, Ratcliffe S, Dichter M, et al. Recent and past intimate partner abuse and HIV risk among young women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(2):219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mittal M, Senn T, Carey M. Mediators of the relation between partner violence and sexual risk behavior among women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(6):510. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318207f59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittal M, Senn T, Carey M. Intimate partner violence and condom use among women: does the information–motivation–behavioral skills model explain sexual risk behavior? AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):1011–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockman J, Lucea M, Draughon J, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk factors among African-American and African-Caribbean women in clinic-based settings. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):472–480. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gielen A, McDonnell K, O’Campo P. Intimate partner violence, HIV status, and sexual risk reduction. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(2):107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fair C, Vanyur J. Sexual coercion, verbal aggression, and condom use consistency among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(4):273–280. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.508085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panchanadeswaran S, Frye V, Nandi V, et al. Intimate partner violence and consistent condom use among drug-using heterosexual women in New York City. Women Health. 2010;50(2):107–124. doi: 10.1080/03630241003705151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman J, McCauley H, Decker M, et al. Coercive forms of sexual risk and associated violence perpetrated by male partners of female adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):60–65. doi: 10.1363/4306011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang D, Salazar L, Wingood G, et al. Associations between recent gender-based violence and pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, condom use practices, and negotiation of sexual practices among HIV-positive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(2):216–221. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814d4dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davila Y, Brackley M. Mexican and Mexican American women in a battered women’s shelter: barriers to condom negotiation for HIV/AIDS prevention. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20(4):333–355. doi: 10.1080/016128499248529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittal M, Stockman J, Seplaki C, et al. HIV Risk Among Women From Domestic Violence Agencies: Prevalence and Correlates. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(4):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014;90(2):145–149. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal A, Ickovics J, Lewis JB, et al. Postpartum Intimate Partner Violence and Health Risks Among Young Mothers in the United States: A Prospective Study. Matern Child Health J. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wingood G, DiClemente R. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):1016–1018. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalichman S, Williams E, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7(3):371–378. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teitelman A, Tennille J, Bohinski J, et al. Unwanted unprotected sex: Condom coercion by male partners and self-silencing of condom negotiation among adolescent girls. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2011;34(3):243–259. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e31822723a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonacquisti A, Geller P. Condom-use intentions and the influence of partner-related barriers among women at risk for HIV. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(23–24):3328–3336. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beadnell B, Baker S, Morrison D, et al. HIV/STD risk factors for women with violent male partners. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):661–689. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swan H, O’Connell D. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s condom negotiation efficacy. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(4):775–792. doi: 10.1177/0886260511423240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teitelman A, Ratcliffe S, Morales-Aleman M, et al. Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, and condom use among minority urban girls. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(12):1694–1712. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.East L, Jackson D, O’Brien L, et al. Condom negotiation: experiences of sexually active young women. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(1):77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(4):701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen D. “I Just Let Him Have His Way” Partner Violence in the Lives of Low-Income, Teenage Mothers. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(1):6–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller E, Silverman J. Reproductive coercion and partner violence: implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(5):511–515. doi: 10.1586/eog.10.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark L, Allen R, Goyal V, et al. Reproductive coercion and co-occurring intimate partner violence in obstetrics and gynecology patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):42–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller E, Decker M, McCauley H, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller E, McCauley H, Tancredi D, et al. Recent reproductive coercion and unintended pregnancy among female family planning clients. Contraception. 2014;89(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller E, Levenson R, Herrera L, et al. Exposure to Partner, Family, and Community Violence: Gang-Affiliated Latina Women and Risk of Unintended Pregnancy. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):74–86. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Rostovtseva D, Khera S, et al. Birth control sabotage and forced sex: experiences reported by women in domestic violence shelters. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):601–612. doi: 10.1177/1077801210366965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller E, Decker M, Reed E, et al. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(5):360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Social science & medicine. 2010;70(11):1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raj A, Santana M, La Marche A, et al. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frye V, Ompad D, Chan C, et al. Intimate partner violence perpetration and condom use-related factors: associations with heterosexual men’s consistent condom use. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9659-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neighbors C, O’Leary A, Labouvie E. Domestically violent and nonviolent male inmates’ responses to their partners’ requests for condom use: Testing a social-information processing model. Health Psychol. 1999;18(4):427–431. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raj A, Reed E, Welles S, et al. Intimate partner violence perpetration, risky sexual behavior, and STI/HIV diagnosis among heterosexual African American men. Am J Mens Health. 2008;2(3):291–295. doi: 10.1177/1557988308320269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raj A, Reed E, Miller E, et al. Contexts of condom use and non-condom use among young adolescent male perpetrators of dating violence. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):970–973. doi: 10.1080/09540120701335246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell D, Sharps P, Gary F, et al. Intimate partner violence in African American women. Online J Issues Nurs. 2002;7(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) ACOG Committee opinion no 554: reproductive and sexual coercion. Obstet and Gynecol. 2013;121(2 Pt 1):411. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000426427.79586.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]