Abstract

Background and Purpose

Acquired apraxia of speech (AOS) is a motor speech disorder caused by brain damage. AOS often co-occurs with aphasia, a language disorder in which patients may also demonstrate speech production errors. The overlap of speech production deficits in both disorders has raised questions regarding if AOS emerges from a unique pattern of brain damage or as a sub-element of the aphasic syndrome. The purpose of this study was to determine whether speech production errors in AOS and aphasia are associated with distinctive patterns of brain injury.

Methods

Forty-three patients with history of a single left-hemisphere stroke underwent comprehensive speech and language testing. The Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale was used to rate speech errors specific to AOS versus speech errors that can also be associated with AOS and/or aphasia. Localized brain damage was identified using structural MRI, and voxel-based lesion-impairment mapping was used to evaluate the relationship between speech errors specific to AOS, those that can occur in AOS and/or aphasia, and brain damage.

Results

The pattern of brain damage associated with AOS was most strongly associated with damage to cortical motor regions, with additional involvement of somatosensory areas. Speech production deficits that could be attributed to AOS and/or aphasia were associated with damage to the temporal lobe and the inferior pre-central frontal regions.

Conclusion

AOS likely occurs in conjunction with aphasia due to the proximity of the brain areas supporting speech and language, but the neurobiological substrate for each disorder differs.

Keywords: Apraxia of speech, aphasia, motor speech disorders, lesion-impairment mapping

Introduction

Apraxia of speech (AOS) is a disorder of motor speech planning that can occur following brain damage to the language-dominant hemisphere. Generally agreed upon characteristics of AOS include articulatory imprecision, atypical prosody, frequent errors with consonants as compared to vowels, and distinct from speech production deficits that occur in aphasia and dysarthria, distorted sound additions and/or substitutions.1,2 The nature of these behaviors differs from that of aphasia, as AOS is not a linguistic impairment (i.e., a problem with the conceptualization of verbal symbols used to communicate thoughts), nor is it a problem with speech motor execution (i.e., dysarthria). Rather, it is a deficit in planning speech motor movements.3

The study of AOS has been plagued by controversy since its description by Darley in 1968,4,5 in part because the behavioral presentation of AOS is often difficult to distinguish from the speech production deficits that can occur in aphasia and dysarthria,6–9 but also because the anatomy of brain damage leading to AOS is very similar to the pattern of damage leading to aphasia.10,11 A seminal study by Dronkers in 199612 localized AOS to damage to the left insula, specifically the superior precentral gyrus of the insula (SPGI). Twenty-five post-stroke patients with chronic AOS had SPGI damage, whereas patients without AOS did not have a lesion in this area. This double dissociation between SPGI damage and AOS has been argued as strong support for the role of the insula in AOS.6,12,13 However, in Dronkers’ study12, none of the patients in the group without AOS were reported to have Broca’s aphasia or other speech impairment (e.g., dysarthria). These patients were classified with Wernicke's, anomic, conduction, or "unclassifiable"/no aphasia. Additionally, lesion distribution maps for this group indicate that areas of maximal overlap occurred in posterior perisylvian areas; therefore, it can be argued that the lesion distribution of this group is too different to serve as an adequate comparison.14

Furthermore, mounting evidence does not support the role of the insula in speech production generally,15 and AOS specifically, as such work has found that AOS can occur in the absence of insula damage11,16–20. This work argues for the involvement of the inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis (IFGpo10,11) or primary and supplementary motor areas,16–20 and has suggested that the maximum overlap in the SPGI can be attributed to vascular distribution and the likelihood of insula damage following a left middle cerebral artery stroke.10,21–22

Differences between the anatomical localization originally proposed by Dronkers12 and that suggested by subsequent studies,10–11,16–20 may be explained by outdated diagnostic criteria for AOS23 or the method of analysis employed.11 Richardson et al.11 compared results from lesion overlap (replicating Dronkers12) and voxel-based lesion symptom mapping (VLSM) using the same diagnostic criteria implemented by Dronkers.12,23 Results from the lesion overlap analysis showed that a sub-region of the insula was indeed the greatest area of overlap in individuals with AOS. However, in the group with aphasia without AOS, some patients (12/24) had damage to the same sub-region of the insula, contradicting previously reported double dissociations between this site of damage and AOS. Additionally, results from the VLSM analysis showed that damage to the IFGpo was the greatest predictor of AOS. Therefore, comparison between these two studies, along with other evidence from patients with AOS as the primary impairment (e.g., stroke-induced19 and primary progressive AOS16–20) suggests that original findings regarding the SPGI may be explained by diagnostic criteria and/or analysis methods implemented.

Here, we classified speech production errors in a cohort of chronic, post-stoke patients as errors that exclusively occur in AOS, and those that can occur in both AOS and/or aphasia. The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that speech production deficits characteristic of AOS are caused by unique anatomical patterns of damage that can be distinguished from patterns of damage related to production deficits that can occur in aphasia. We hypothesized that: 1) Speech errors unique to AOS are associated with damage in cortical motor and somatosensory areas;16–20 2) Speech errors that can occur in aphasia are predominantly represented by patterns of damage along the ventral stream, and/or dorsal areas that are responsible for “higher level” production processes.24

Methods

Participants

43 patients who incurred a single-event left hemisphere stroke (17 female; mean age=59.2±10.7) were included. Patients were recruited as part of a larger stroke study at the University of South Carolina, in which inclusion criteria included single-event ischemic stroke. Patients were selected for the current sample if they had experienced a left-hemisphere stroke. No patients had a history of other neurological disease or developmental language abnormalities. All were tested at the chronic phase of recovery (i.e., ≥ 6 months post-stroke; mean months post-onset = 52.5±38.9).

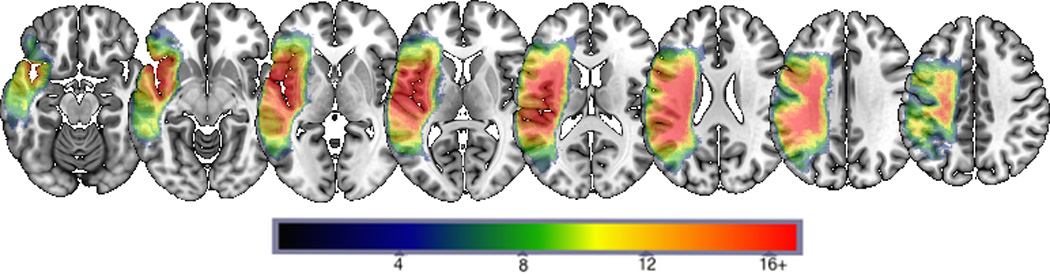

Patients varied in the presence/absence of aphasia type and severity as follows: no aphasia: n=14; anomic: n=11; Broca’s: n=11; conduction: n=4; Wernicke’s: n=2; and global: n=1. Mean WAB score for all patients with aphasia was 72.5±18.7, and 97.8±1.6 for those without aphasia. A lesion overlap map for all patients is presented in Figure 1. All patients provided informed consent in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Carolina.

Figure 1.

Lesion overlap maps for all patients. Area of greatest overlap (in red) indicates locations where at least 16 patients have damage.

Procedure

Behavioral tasks

Speech production was rated using the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (ASRS2). Speech samples were obtained from audiovisual recordings of three picture description tasks, a reading passage, diadochokinetic rates, and conversation. The speech characteristics included on the ASRS classify speech abnormalities into four categories: (a) features that occur in AOS, but not in dysarthria or aphasia; (b) features that can occur due to AOS and/or dysarthria; (c) features that can occur due to AOS and/or aphasia, and (d) features that can occur due to AOS/dysarthria/aphasia. In general, AOS-specific behaviors include segment-level articulatory errors characterized by distorted sound substitutions/additions, while speech production errors that can also be attributed to aphasia include initiation difficulty, false starts/restarts, audible/visible groping, and difficulties with sequential motor rates.2 Additional details about the scale's items, and the scale itself, can be found in Strand et al.2

ASRS ratings for all patients were completed by an American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)-certified speech-language pathologist (SLP) with experience using this scale for classifying speech production behaviors as related to AOS, aphasia and dysarthria. Each patient was rated on the presence/severity of all ASRS speech characteristics, based on a 5-point scale (0=not present; 1=detectable but not frequent; 2=frequent but not pervasive; 3=nearly always evident but not marked in severity; 4=nearly always evident and marked in severity).

According to ASRS criteria, a patient must have at least one “primary distinguishing feature” rated for AOS diagnosis. Additionally, an overall score greater than eight is most reliably associated with AOS2. Based on each patient’s ratings, clinical judgment about the presence/absence of AOS was determined. If AOS was present, then the overall severity was rated (1–4). If AOS was not present, then the patient receives a score of 0 for AOS severity. This score was determined by specific ratings from the ASRS items and the overall impact of these production difficulties on each patient’s communication abilities.

An overall severity score for production errors related to aphasia severity was assigned to each patient as applicable, using the same aforementioned 5-point scale. Patients' WAB-R scores were additionally used to determine aphasia presence/absence and severity ratings. Items that can occur in dysarthria were rated, but not used in subsequent analyses, as the focus of this study was aphasia and AOS.

Reliability

Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was established using a two-way mixed, consistency single-measures intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC25) with the primary rater and another ASHA-certified SLP who rated patients by independently viewing the video-recorded speech and language samples for a subset of patients (n=10). ICC was computed for ratings on each of the 16 items on the ASRS and overall severity ratings for both AOS and aphasia. The ICC was .884, indicating good reliability between the two raters.26

MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens 3T Trio System with a 12-channel head-coil. All patients underwent scanning with the following imaging sequences: 1. T1-weighted sequence using a MP-RAGE (TFE) sequence with a FOV=256×256mm, 192 sagittal slices, 9° flip angle, TR=2250ms, TI=925ms, and TE=4.15ms, GRAPPA=2, 80 reference lines; 2. T2-weighted MRI for the purpose of lesion-demarcation with a 3D SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts by using different flip angle Evolutions) protocol with the following parameters: FOV= 256×256mm, 160 sagittal slices, variable flip angle, TR=3200ms, TE=352ms, no slice acceleration. The same slice center and angulation was used as with the T1 sequence.

Preprocessing of Structural Images

The Clinical Toolbox27 for SPM8 was used for the preprocessing of images. Stroke lesions were demarcated by a neurologist (LB) in MRIcron28 on individual T2-MRIs (in native space), using the T1-MRI and diffusion sequences for guidance. Preprocessing began with the co-registration of the T2-MRI to match the T1-MRI, aligning the lesions to native T1 space.

Lesion cost-function masking29 was then utilized for segmentation and normalization30 with the stroke-control template image included with the Clinical Toolbox. The cost-function normalization process registered T1-weighted images into standard space. The hand drawn T2 lesion masks were used for cost-function normalization. However, once the T1 weighted images were registered onto standard space, the location of post-stroke gliosis was assessed by T1-signal intensity, which was used as a continuous measure of anatomical damage as chronic stroke, as opposed to the hand drawn lesion masks. Because stroke is associated with hypointense signal on chronic T1-MRI31 this method of analysis utilizes hypointense signal as a continuous quantification of structural damage to predict behavior. The use of continuous data has been suggested to be superior in increasing sensitivity of correlations when compared to binary lesion classifications in whole-brain analyses.31 To account for individual differences in overall signal intensity, we calculated z-scores for each patient’s T1-MRI on a voxel-by-voxel basis based on the mean and standard deviation of the right hemisphere image intensity of that patient using an in-house code written in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA). This method allows for standardization based on the image intensity of the structurally-intact right hemisphere (using a brain mask from the clinical toolbox corresponding to the entire right hemisphere thresholded for >50% combined probability of the voxel belonging to gray or white matter). This approach has been used previously in our lab32 and in other work as a surrogate measure of damage in other studies (e.g.,33,34). It is possible that for some individuals, stroke-related changes occurred in the right hemisphere (e.g. diaschisis), introducing greater error in the overall analysis. Based on first principles, this error should have decreased the likelihood of finding significant results.

Lesion-Symptom Mapping Analysis

We conducted Freedman-Lane Regression where each behavioral variable acted as a nuisance regressor for the other using Matlab routines developed by Ged Ridgway.35 Of note, we chose to employ a regression analysis, as opposed to logistic regression or ANCOVA because we employed images with continuous voxel-based measures instead of binary lesions and conducted permutation thresholding. Whole brain analyses were completed with the threshold for statistical significance set to p< 0.05, using 4000 permutations to control for multiple comparisons.36 Threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE37) was used to improve signal-to-noise detection of significant clusters using routines developed by Christian Gaser (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/tfce/). Specifically, for each permutation we transformed the 3D z-score map using the TFCE formula that emphasizes voxels that are both bright (strong z-scores) and in a bright neighborhood (strong support). For each permutation we scrambled all voxels in a given volume, identified the single brightest resulting voxel, and rank-ordered these values. The 200th most significant value (5%) was used as the subsequent statistical threshold, robustly controlling for familywise error. Accordingly, our threshold is based on the peak of all voxels for each permutation. All of these routines are integrated into our NiiStat toolbox for Matlab (http://www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/CRNL/tools/niistat).

We aimed to identify clusters of voxels where there was a contiguous significant correlation between the voxel intensity and the behavioral measure. By reducing the variability across contiguous voxels, TFCE increases the statistical power of voxel-lesion based analysis, preserving the identification of clusters composed by voxels with a strong relationship with behavior.

Results

Behavioral Measures

Eighteen patients were classified with AOS (mean ASRS score=2.8±1.1). Two of these patients did not have concomitant aphasia. For the remaining patients with AOS (n=16), their aphasia was classified as follows: Broca’s: 12; anomic: 3; global: 1. Six patients had concomitant dysarthria (mean severity=1.83). Twelve were classified with aphasia only (mean ASRS aphasia severity=1.33), and 11 did not classify with any speech or language deficits.

Neuroimaging

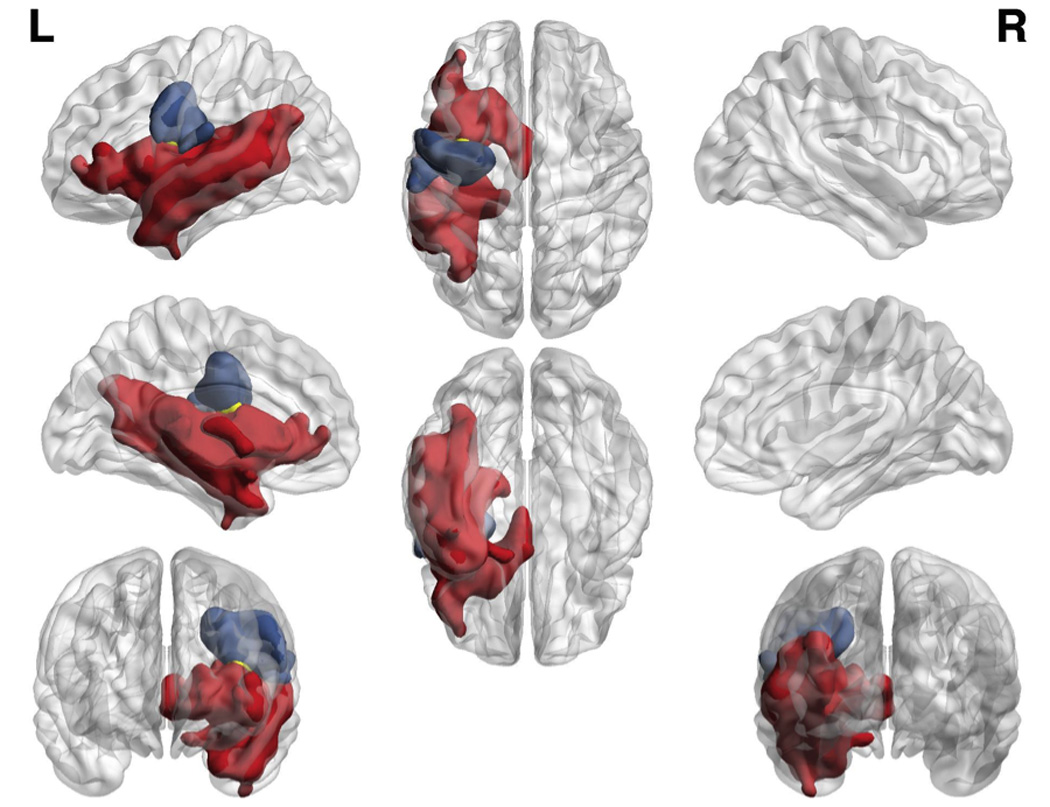

All 189,005 voxels inside the 2mm isotropic brainmask were included in the whole brain analysis. A total of 15,639 voxels survived thresholding for severity of speech errors typically associated with aphasia (defined by the TFCE threshold 12.86), and 2,508 voxels survived thresholding for severity of speech errors associated with AOS (defined by the TFCE threshold 12.49). Statistical maps (herein referred to as "clusters") associated with speech errors in AOS and AOS and/or aphasia are overlaid on a standard brain map and presented in Figure 2, with clusters predictive of AOS speech errors in blue and aphasic speech errors in red. There was a small region (34 voxels) where damage predicted both AOS and aphasic errors (after treating the other behavior as a nuisance variable). This small area is displayed in yellow in Figure 2. Since TFCE identifies clusters of voxels homogeneously associated with behavior, we report each cluster as a single element, without the voxel-wise breakdown of statistical values.

Figure 2.

Patterns of damage related to AOS (blue) and aphasia (red), and shared by both disorders (yellow). Colored regions survived a p < 0.05 threshold controlling for both multiple comparisons and the variability described by the other deficit.

The three thresholded clusters were subsequently scrutinized using the Johns Hopkins University atlas (JHU38) and a custom Matlab script to identify the extent to which each cluster occupied different anatomical brain areas. The cluster common to AOS-specific speech errors was distributed across the pre- and post-central gyri, while the cluster associated with aphasic speech errors was distributed across a number of anatomical regions in the inferior prefrontal and temporal regions. For the clusters associated with AOS and aphasic errors independently, ROIs that contributed to at least 3% of the respective cluster are listed in Table 1 (the specific percentage is listed in column 2). The percentage of damage to each specific ROI has also been provided (column 3).

Table 1.

Anatomical regions associated with AOS and aphasia. The first column lists regions of interest (ROIs; defined by the JHU atlas) in which damage was identified to be associated with the behavioral speech characteristics of each disorder. The second column displays the percent of each behaviorally-related statistical map (i.e. cluster) that was distributed within each identified ROI. The third column displays the proportion of each ROI compromised. For example, the superior temporal gyrus was associated with Aphasia, accounting for 9.658% of the voxels associated with this deficit and a total of 76.046% of the voxels in this region.

|

ROIs associated with Aphasia characteristics |

Percent of the Aphasia-related cluster within each ROI |

Percent of the ROI damaged |

| Superior temporal gyrus | 9.66 | 76.05 |

| Posterior middle temporal gyrus | 8.53 | 67.51 |

| Posterior superior temporal gyrus | 5.73 | 76.13 |

| Insula | 4.74 | 93.46 |

| Superior temporal pole | 3.72 | 46.04 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus pars orbitalis | 3.46 | 49.37 |

| Posterior thalamic radiation | 3.42 | 70.67 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis | 3.32 | 41.13 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | 3.22 | 12.57 |

| Angular gyrus | 3.14 | 18.10 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | 3.13 | 43.43 |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | 3.12 | 35.14 |

| Thalamus | 3.11 | 39.07 |

|

ROIs associated with AOS characteristics |

Percent of the AOS-related cluster within each ROI |

Percent of the ROI damaged |

| Precentral gyrus | 48.65 | 29.91 |

| Postcentral gyrus | 21.05 | 13.82 |

| Superior corona radiata | 10.80 | 26.95 |

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus | 9.78 | 25.07 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | 4.59 | 4.51 |

Discussion

We demonstrated that speech errors in AOS and aphasia result from unique patterns of brain damage. Specifically, we identified regions in cortical motor and somatosensory areas that predict AOS errors, even after removing variability explained by errors that could also occur in aphasia (and vice versa). The study of AOS has been built on different definitions of the disorder,39–41 complicating the interpretation of findings regarding its localization and theoretical bases, and hindering the generalizability of conclusions pertaining to speech motor planning in general. On the most fundamental level, the current practices for AOS diagnosis are largely ambiguous and subject to variability in interpretation. Furthermore, the one published and widely used AOS battery, the Apraxia Battery for Adults-2,42 is subject to failure in the differential diagnosis between AOS and aphasia.40

Importantly, these results add to a growing body of evidence attempting to rectify many debates surrounding AOS by using the ASRS, a descriptive scale created by researchers who have extensive experience with AOS and motor speech disorders.2 The ASRS provides a more detailed description and classification of production errors, based on expert opinion and developed in part as a response to decades of debate regarding the description of AOS. The ASRS itself is based on perceptual ratings, but shows high reliability and validity in distinguishing between production errors that can occur in AOS, aphasia and dysarthria. It has also been used in a number of studies to explicitly describe and further localize production deficits in AOS19 and progressive AOS.16–18,20

Although previous work has localized AOS to the left SPGI of the insula12,13 or the left IFG,10,11 this study provides converging evidence between the neuroanatomical underpinnings of severity ratings of AOS using the ASRS and neuroimaging findings with recent investigations into the localization of post-stroke AOS19 and PPAOS.16–20 We did not find evidence of insula involvement in predicting AOS, similar to recent studies with PPAOS.17–18 Furthermore, a recent fMRI study in neurologically-intact individuals15 found that the SPGI is not involved in complex articulation tasks as previously suggested by patient data.12,13 Clearly our methods were sufficient for detecting statistically significant results in the insula, as damage to this area was a significant predictor for speech errors that can occur in aphasia, but did not survive thresholding for severity of speech errors that are characteristic of AOS. Additionally, the cohort of patients in this study demonstrated lesion coverage of the left hemisphere, with maximum overlap in key regions that have been associated with speech production (e.g., insula, IFGpo, precentral/postcentral areas). The JHU atlas does not divide the insula into specific regions; rather, the entirety of the insula boundary is included in the JHU atlas’s insula ROI. Regardless, if damage to any portion of the insula were to be predictive of AOS, this would have been evident in the ROI analysis.

Finally, this study did not replicate prior work that has credited the IFGpo with damage crucial for AOS. The IFGpo accounted for less than 1% of the AOS cluster (.05%), with only 0.14% damage to this ROI; however, the IFGpo accounted for 2.23% of the aphasia severity cluster, with 33.69% IFGpo damage associated with aphasia. These results do not discount the role of the IFGpo or the insula in motor speech production in general, but instead implicate both the insula and IFGpo in higher levels of verbal output, prior to speech motor planning. This notion is supported further by an electrocorticographic (ECoG) study by Flinker et al.,43 who revealed that Broca’s area itself is not involved in articulation per se, but serves as a relay between auditory representations of words (stored in ventral stream areas24), and articulatory programs that are executed in cortical motor areas.43

Conclusions

These results implicate the role of cortical motor and somatosensory areas in the primary localization of AOS. Theoretically, this study provides additional support for the role of low-level somatosensory and motor control in AOS.44 Clinically, evidence provided here suggests that using structural neuroimaging in addition to a valid rating scale may improve the differential diagnosis of speech production errors resulting from AOS versus those that could be attributed to aphasia. Such work will ultimately further the study of speech production in general, and clinically, support the development of more valid assessments for AOS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We also thank Dr. Joe Duffy and colleagues for use of the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (ASRS).

Funding: The authors are grateful for the generous funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders) through award R01DC009571. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Duffy JR. Motor speech disorders: substrates, differential diagnosis, and management. Third Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strand E, Duffy J, Clark H, Josephs K. The apraxia of speech rating scale: A tool for diagnosis and description of AOS. J Commun Disord. 2014;51:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Merwe A. A theoretical framework for the characterization of pathological speech sensorimotor control. In: McNeil MR, editor. Clinical Management of Sensorimotor Speech Disorders. New York, NY: Thieme; 1997. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballard KJ, Granier JP, Robin DA. Understanding the nature of apraxia of speech: Theory, analysis, and treatment. Aphasiology. 2000;14:969–995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenbek JC. Darley and apraxia of speech in adults. Aphasiology. 2001;15:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogar J, Slama H, Dronkers N, Amici S, Gorno-Tempini ML. Apraxia of speech: an overview. Neurocase. 2005;11:427–432. doi: 10.1080/13554790500263529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Code C. Models, theories and heuristics in apraxia of speech. Clin Linguist Phonet. 1998;12:46–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley KL, Jacks A, de Riesthal M, Abou-Khalil R, Roth HL. Toward a quantitative basis for assessment and diagnosis of apraxia of speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55:S1502–S1517. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0318). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haley KL, Jacks A, Cunningham KT. Error Variability and the Differentiation Between Apraxia of Speech and Aphasia With Phonemic Paraphasia. JSLHR. 2013;56:891–905. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0161). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillis AE, Work M, Barker PB, Jacobs MA, Breese EL, Maurer K. Re-examining the brain regions crucial for orchestrating speech articulation. Brain. 2004;127:1479–1487. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson JD, Fillmore P, Rorden C, LaPointe LL, Fridriksson J. Re-establishing Broca’s initial findings. Brain Lang. 2012;123:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dronkers NF. A new brain region for coordinating speech articulation. Nature. 1996;384:159–161. doi: 10.1038/384159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogar J, Willcock S, Baldo J, Wilkins D, Ludy C, Dronkers N. Clinical and anatomical correlates of apraxia of speech. Brain Lang. 2006;97:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rorden C, Karnath HO. Using human brain lesions to infer function: A relic from a past era in the fMRI age? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:812–819. doi: 10.1038/nrn1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedorenko E, Fillmore P, Smith K, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J. The superior precentral gyrus of the insula does not appear to be functionally specialized for articulation. [Accessed 20 February 2015];J Neurophysiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/jn.00214.2014. [Published ahead of print January 28, 2015]. http://jn.physiology.org/content/early/2015/01/21/jn.00214.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Layton KF, Parisi JE, et al. Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain. 2006;129:1385–1398. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Master AV, et al. Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain. 2012;153:1522–1536. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Xia R, Mandrekar J, Machulda MM, et al. Distinct regional anatomic and functional correlates of neurodegenerative apraxia of speech and aphasia: an MRI and FDG-PET study. Brain Lang. 2013;125:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graff-Radford J, Jones DT, Strand EA, Rabinstein AA, Duffy JR, Josephs KA. The neuroanatomy of pure apraxia of speech in stroke. Brain Lang. 2014;129:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy JR, Strand EA, Clark H, Machulda M, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA. Primary progressive apraxia of speech: Clinical features and acoustic and neurologic correlates. [Accessed March 18, 2015];AJSLP. 2015 doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0174. [published online ahead of print on February 4, 2015]. http://ajslp.pubs.asha.org/Article.aspx?doi=10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caviness V, Makris N, Montinaro E, Sahin N, Bates J, Schwamm L, et al. Anatomy of stroke, part I: an MRI-based topographic and volumetric system of analysis. Stroke. 2002;33:2549–2556. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000036083.90045.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finley A, Saver J, Alger J, Pregenzer M, Leary M, Ovbiagele B, et al. Diffusion weighted imaging assessment of insular vulnerability in acute middle cerebral artery infarctions [abstract] Stroke. 2003;34:259. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wertz RT, LaPointe LL, Rosenbek JC. Apraxia of Speech in Adults: The Disorder and its Management. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickok G. The architecture of speech production and the role of the phoneme in speech processing. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 2014;29:2–20. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2013.834370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol methods. 1996;1:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rorden C, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J, Bender B, Karnath HO. Age-specific CT and MRI templates for spatial normalization. Neuroimage. 2012;61:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behav Neurol. 2000;12:191–200. doi: 10.1155/2000/421719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brett M, Leff AP, Rorden C, Ashburner J. Spatial normalization of brain images with focal lesions using cost function masking. Neuroimage. 2001;14:486–500. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. NeuroImage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyler LK, Marslen-Wilson W, Stamatakis EA. Dissociating neuro-cognitive component processes: voxel-based correlational methodology. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fridriksson J, Guo D, Fillmore P, Holland A, Rorden C. Damage to the anterior arcuate fasciculus predicts non-fluent speech production in aphasia. Brain. 2013;136:3451–3460. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Pan P, Huang R, Shang H. A meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies of white matter volume alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boddaert N, Brunelle F, Desquerre I. Clinical and imaging diagnosis for heredodegenerative diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013;111:63–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, Nichols TE. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage. 2014;92:381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rorden C, Fridriksson J, Karnath H-O. An evaluation of traditional and novel tools for lesion behavior mapping. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2008;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faria AV, Joel SE, Zhang Y, Oishi K, van Zjil P, Miller MI, et al. Atlas-based analysis of resting-state functional connectivity: Evaluation for reproducibility and multi-modality anatomy-function correlation studies. Neuroimage. 2012;61:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNeil MR, Robin DA, Schmidt RA. Apraxia of speech: Definition, differentiation, and treatment. In: McNeil MR, editor. Clinical Management of Sensorimotor Speech Disorders. New York, NY: Thieme; 1997. pp. 311–344. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNeil MR, Pratt SR, Fossett T. The differential diagnosis of apraxia of speech. In: Massen B, et al., editors. Speech Motor Control in Normal and Disordered Speech. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 389–413. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mumby K, Bowen A, Hesketh A. Apraxia of speech: how reliable are speech and language therapists' diagnoses? Clin Rehab. 2007;21:760–767. doi: 10.1177/0269215507077285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dabul B. Apraxia battery for adults. second edition. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flinker A, Korzeniewska A, Shestyuk AY, Franaszczuk, Dronkers NF, Knight RT, et al. Redefining the role of Broca’s area in speech. PNAS. 2015;112:2871–2875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hickok G, Rogalsky C, Chen R, Herskovits EH, Townsley S, Hillis A. Partially overlapping sensorimotor networks underlie speech praxis and verbal short-term memory: Evidence from apraxia of speech following acute stroke. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:649. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.