Abstract

During the last century, vitamin A has evolved from its classical role as a fat-soluble vitamin and attained the status of para-/autocrine hormone. Besides its well-established role in embryogenesis, growth and development, reproduction and vision, vitamin A has also been implicated in several other physiological processes. Emerging experimental evidences emphasize adipose tissue as an active endocrine organ with great propensity to continuous growth (throughout life). Due to various genetic and lifestyle factors, excess energy accumulates in adipose tissue as fat, resulting in obesity and other complications such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Recent in vitro and in vivo studies have shed light on vitamin A metabolites; retinaldehyde and retinoic acid and participation of their pathway proteins in the regulation of adipose tissue metabolism and thus, obesity. In this context, we discuss here some of our important findings, which establish the role of vitamin A (supplementation) in obesity and its associated disorders by employing an obese rat model; WNIN/Ob strain.

Keywords: adipose tissue, inflammation, insulin resistance, muscle, obesity, retinoids, supplementation

Introduction

Vitamin A exists in three physiologically active forms (Vitamers) namely retinol (alcohol), retinal (aldehyde) and retinoic acid (acid), which are collectively known as retinoids (which also include synthetic compounds having some biological activity of vitamin A). Vitamin A is an important fat-soluble micronutrient essential for embryonic development, haematopoiesis, neuronal cell growth, reproduction, immune function, vision, etc.1,2,3,4,5. In addition to its wide range of physiological functions, extensive research during the past two decades labelled vitamin A as a key regulator of adipose tissue biology6,7,8. The recent studies addressing the role of vitamin A metabolic pathway to various physiological processes by way of gene knockout models (ALDH, CRBP, LRAT, RBP4, RDH, BCMO, STRA6 and RetSat)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 mark the plethora of events regulated by vitamin A. In this context, the main focus of this review is to highlight certain important findings, which unveiled the role of vitamin A on obesity and its associated disorders particularly dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance and retinal degeneration from an obese rat model of WNIN/Ob strain.

Obesity and role of adipose tissue

Obesity, the chronic, highly prevalent abnormal metabolic condition affecting the millions of lives across the globe with enormous economic consequences has been aptly identified as “globesity”17. It has been predicted that by 2030 adults will contribute 1.12 billions to obese and 2.16 billions to overweight population worldwide18. Obese people are at a greater risk for co-morbidity and mortality due to a variety of medical complications including type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), sleep apnoea and some types of cancers, apart from various psychological stresses including body image, disparagement, impaired quality of life and depression19.

Though, the aethiopathogenesis of obesity is largely unclear, genetic and lifestyle factors are believed to determine the development and progression of the obesity. In obese condition, excess energy is deposited as fat in adipose tissue, particularly, white adipose tissue (WAT). WAT with its capability of accommodating the excess energy leads to an increased adipose tissue growth in obese people. Adipose tissue consists of several cell types including mature adipocytes, stromal vascular fractions consisting of pre-adipocytes, immune cells, vascular progenitor cells and endothelial cell. In humans, nearly 30 billion adipocytes are present during the development of infant to adolescent and this number can go up to 40-60 billion cells under abnormal conditions such as obesity, amounting to 0.5-1 per cent of total number of cells of a human body. Normally, the size of a mature adipocyte varies from 10 to 200 μm and accommodates 0.5-1μg of fat and maximum of 4 μg under abnormal metabolic condition. In a healthy individual, adipocyte mass accounts for approximately 20 per cent of body weight and fat mass may range from 2-3 to 60-70 per cent of body weight of a normal athletes and massively-obese individuals, respectively20,21.

Biological link between adipose tissue and vitamin A

Besides liver, adipose tissue contains substantial amount of retinol and its metabolites. Tsutsumi et al22 have shown that visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots reserve comparable amount of retinol (i.e. 6.4 and 6.9 μg retinol per gram tissue). They also found that in adipose tissues, retinol is stored mostly in free form, which accounts for 75 per cent, while esterified form accounts for only 25 per cent of total retinol stores22.

Several studies have shown that adipose tissue plays an active role in the metabolism and homeostasis of vitamin A by taking-up circulatory chylomicron-bound (by lipoprotein lipase)/retinol binding protein (RBP)-bound retinol and converting retinol to physiologically - active metabolites viz. retinaldehyde (Rald) and retinoic acid (RA). Interestingly, WAT also expresses RBP at high levels, which further emphasizes its role in retinoid homeostasis. Adipocytes are reported to have complete machinery for the uptake, transport, esterification, hydrolysis, oxidation and degradation of retinoids such as RBP4 receptor; stimulated by retinoic acid (STRA6), lipoprotein lipase, cellular retinol binding proteins, retinol binding protein, lecithin:retinol acyltransferase, acyl CoA:retinol acyltransferase, hormone-sensitive lipase, short chain dehydrogenases/reductases, alcohol dehydrogenases and aldehyde dehydrogenases and cytochrome 450 enzyme; CYP26, etc. Thus, adipocytes store, metabolize and mobilize their retinol stores to meet both local and total body demands23,24,25. Apart from vitamin A homeostasis, adipose tissue also differentially expresses the retinoid X receptor and retinoic acid receptors of different subtypes (α, β and γ); the transcriptional regulator of vitamin A thereby suggesting that adipocytes are the potential targets for vitamin A action26,27,28.

Obesity, inflammation and vitamin A

Growing evidences suggest that obesity is an abnormal metabolic condition associated with chronic low grade inflammation and altered intestinal microbiome, which are known to play a major role in this disease process29,30. Adipose tissue is proven to be the major contributor of inflammation and now it is well recognized as not just an inert energy reservoir, but functions as an endocrine organ and centre of immune modulation by virtue of secreting various adipokines such as leptin, adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukins (ILs), and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP). These adipokines and cytokines are the primary mediators of inflammation and implicated in the development of various obesity-associated inflammatory complications including insulin resistance, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cardiovascular disease, etc.31,32,33.

Among various adipokines, leptin is secreted primarily by the adipose tissue and is identified as a regulator of food intake and energy homeostasis34. Leptin is also recognized as a hormone with multiple physiological functions; especially linking obesity, immune functions and inflammation35,36,37,38. Kumar and Scarpace39 have shown for the first time that retinoic acid downregulates the leptin mRNA in white adipose tissue39. Subsequently, many studies have demonstrated the negative transcriptional regulation of leptin gene by vitamin A and its metabolites in experimental models40,41,42. However, the impact of vitamin A supplementation on obesity, leptin and regulation of inflammation has not been addressed so far. Vitamin A and its metabolites are known to potentiate the immune system and functions including T-cell proliferation, B-cell activation, T helper cells (TH1 & TH2) balance and differentiation of regulatory T-cells (Treg cells)43,44. Role of vitamin A on immunity, its function on immune system and obesity under deficient and sufficient conditions have been extensively reviewed by Garcia45,46.

In humans, studies have shown the association between vitamin A intake and obesity. Zulet et al47 have reported inverse relationship between vitamin A intake and adiposity in healthy adults aged between 18-22 yr. Other studies have also reported inverse correlation between serum retinol and body mass index in morbidly obese subjects48,59,50,51,52,53,54. Further, in obese subjects, adipose derived-inflammatory cytokines, such as leptin, serum amyloid A (SAA), TNF-α and IL-6 have been shown to be elevated55,56. Reichert et al27 have observed abundant expression of retinoic acid synthesizing enzyme gene Aldh1a1 in fat fads particularly subcutaneous and omental fat of healthy women. In Aldh1a1 knockout mouse model deficiency of this gene impaired hepatic glucose production resulting in decreased fasting glucose levels57. Further, these mice, displayed higher uncoupling protein-mediated thermogenesis in white adipose tissue and thereby regulating energy homeostasis58. Discovery of adipose-derived retinol binding protein added a new insight into the role of vitamin A metabolic pathway protein on the regulation of insulin sensitivity12. Mills et al59 have found a significant association between circulatory RBP, obesity and insulin resistance. They observed a two-fold increase in apo-RBP levels in obese subjects compared to non-obese counterparts. Several other studies have reported significant association between vitamin A status, circulatory RBP level, obesity and metabolic syndrome in human subjects60,61,62,63,64,65.

Role of vitamin A: Evidences from a genetic obese rat model (WNIN/Ob strain)

I. Study on adult rats

(i) Effect on adiposity: It is well known that adipose tissue mass is tightly regulated by both size and/or number and the latter in turn is regulated by a balanced process of recruitment, differentiation of pre-adipocyte into mature adipocyte (adipogenesis) and adipocyte cell death (apoptosis). Murray and Russell66 for the first time demonstrated the inhibitory effect of retinoic acid on adipogenesis in 3T3L1 preadipocytes. Subsequently, many studies have shown similar inhibitory effect of retinoids on adipogenesis/adiposity, using both in vitro and in vivo models, perhaps through different mechanisms67,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72. However, no study has explored the effect of vitamin A-enriched diet on obesity using either diet-induced or genetic models.

The WNIN/Ob rat strain developed spontaneously from a 90-year-old Wistar-inbred rat stock colony maintained at National Centre for Laboratory Animal Sciences (NCLAS), National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), Hyderabad, India has three phenotypes namely lean (+/+), carrier (+/-) and obese (-/-) and the crossing between carrier rats has resulted in three phenotypes following the classical Mendelian ratio of 1:2:1, respectively. Though, the exact mutation responsible for the obese phenotypes is yet to be identified, Kalashikam et al73 have observed the localization of mutation to a recombinant region upstream of the leptin receptor, i.e. 4.3 cM region with flanking markers D5Rat256 and D5Wox37 on chromosome 5. The obese phenotype of this strain is characterized by polyurea, polydypsia, hyperphagia, euglycaemia, hyperleptinaemia, hyperinsulinaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypercholesterolaemia, visceral adiposity (which are akin to human obesity)74 and elevated plasma high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol levels. Further, these obese rats are infertile and elicit poor immune response to hepatitis B vaccine74,75. When adult male (7 months old) obese rats were fed with vitamin A-enriched diet (i.e. as a source of vitamin A, 129 mg retinyl palmitate added per kilogram of diet) for a period of 60 days, significant reductions in body weight gain, adiposity index and visceral fat; retroperitoneal white adipose tissue (RPWAT) were observed without any alteration in their food intake as compared to stock diet-fed obese counterpart76.

Experiments to understand the mechanism of vitamin A-mediated action have revealed that high doses of vitamin A did not affect the adipocyte size of RPWAT in any of the phenotypes as indicated by adipocyte cell density76. On the other hand, vitamin A-induced RPWAT apoptosis was observed in lean rats. Protein expression data showed a significant reduction in anti-apoptotic protein; Bcl2 expression, with a concomitant increase in pro-apoptotic protein; Bax, which was in line with the moderate reduction in adiposity and RPWAT weight76. However, in obese phenotypes, there were no such changes in the expression of pro-and anti-apoptoic proteins or their ratio76.

Further, in obese rats fed with vitamin A-enriched diet, brown adipose tissue-uncoupling protein 1 (BAT-UCP1) expression showed a marked increase, while lean rats did not show such transcriptional activation upon feeding of vitamin A-enriched diet as compared to their respective counterpart receiving a stock diet77. It is well established that vitamin A metabolites, particularly, retinoic acid is a potent positive regulator of BAT-UCP167,68. However, in our study, it was not clear as to why lean rats did not have BAT-UCP1 induction by high vitamin A diet feeding. It was presumed that lean rats had a maximal basal expression of UCP1 compared with their age- and sex-matched obese counterparts, which was not further induced by vitamin A supplementation77. We have also reported that fatty acid desaturase index; which reflects the stearoyl CoA desaturase1 (SCD1) activity, of plasma and various tissues is well correlated with adiposity and body mass indices of obesity78. However, in this study, data from stearoyl CoA desaturase1 gene expression of both liver and adipose tissue revealed that anti-obesity effect of vitamin A was independent of SCD1 regulation, a well-known lipogenic/adipogenic marker79,80. Feeding the obese rats of the same strain with identical dose of vitamin A (129 mg per kg diet for 20 wk) resulted in the loss of visceral fat, which was partly attributed to decreased 11β-HSD1 activity resulting in low levels of active metabolites of glucocorticoids81. Overall, data from adult WNIN/Ob strain studies demonstrate that vitamin A regulates obesity through visceral fat loss partly by thermogenic and glucocorticoid pathways in obese rat.

(ii) Effect on dyslipidaemia: The most evident systemic problem associated with long-term treatment of retinoic acid for various types of skin disorders and cancer is hypertriglyceridaemia (HTG) and dyslipidaemia82,83,84. Similarly, chronic feeding of vitamin A-enriched diet evoked hypertriglyceridaemia in both lean and obese phenotypes. It is well known that stearoyl CoA desaturase1 is one of the key determinant factors responsible for hypertriglyceridaemia79,80. Though lean rats showed a positive association between elevated SCD1 expression and hypertriglyceridaemia by vitamin A feeding, obese rats did not show such association76. Retinoic acid-induced hypertriglyceridaemia is shown to be due to both increased hepatic production of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and suppression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity in peripheral tissues83. We speculate that in obese rats, vitamin A-mediated-hypertriglyceridaemia may be partly due to inhibition of peripheral utilization of VLDL-triglycerides by LPL and/or by increased hepatic production of VLDL.

In obese rats, there was a significant increase in hepatic total lipid, triglycerides (TG) and decrease in phospholipid (PL) contents after feeding with vitamin A-enriched diet76, whereas in lean rats a similar trend was seen, though not significant. It is known that the initial step is shared by both TG and PL biosynthetic pathways, and therefore, we speculate that vitamin A might increase the hepatic TG synthesis by activating key enzymes involved in TG pathway such as glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) and diacyl glycerol:acyltransferase (DGAT), which would have hampered the PL synthesis and decreased lipid phosphate contents of liver76. We do not have supportive data at present; however, studies are underway to find out the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Obese rats are hypercholesterolaemic with elevated HDL-C levels, partly due to underexpression of hepatic scavenger receptor class B1 (SR-B1), an authentic HDL receptor, which brings about selective uptake of cholesterol esters from HDL particle by liver; the final step in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) and its subsequent excretion as free cholesterol or bile acids through bile85. It was observed that obese rats fed with vitamin A-enriched diet resulted in reduction in circulatory cholesterol level and normalized HDL-C levels, with concomitant upregulation of hepatic SR-BI expression at both protein and gene levels in obese phenotype. The results show vitamin A as a positive regulator of SR-B1 gene and its role in the regulation of obesity-associated hypercholesterolaemia in obese rats of WNIN/Ob strain86.

(iii) Effect on retinal degeneration: Various clinical and epidemiological studies have shown the positive association between obesity and age-related macular degeneration (AMD)87,88,89. Previously, Reddy et al90 have shown the progressive retinal degeneration after the onset of obesity in this obese rat strain (WNIN/Ob) due to retinal stress and other factors including impaired tissue remodelling and phototransduction, etc. Recently Marcal et al91 have reported that impaired AKT signaling in retina is the key player of the retinal degeneration in diet-induced obese model. We have linked elevated polyol pathway to the cataract development in these obese rats92. Improved retinal morphology associated with increased retinal rhodopsin, rod arrestin, phosphodiesterase, transducins, and fatty acid elongase-4 gene expression was observed upon vitamin A-enriched diet feeding (26 & 52 mg per kg diet for about 20 wk). The basal levels in obese rats were found to be low when compared to their age- and sex-matched lean counterparts fed on stock diet containing 2.6 mg vitamin A per kg diet93. These observations indicate that specific nutrient supplementation particularly vitamin A may help in the amelioration of retinal degeneration associated with obesity and aging.

II. Study on younger rats

(i) Effect on adiposity & dyslipidaemia: Study on younger rats (50 days old) was done to test the hypothesis that early intervention with vitamin A-enriched diet (129 mg/kg diet) prevents the development of obesity and its associated disorders in the same strain rats i.e. WNIN/Ob. At the end of three months, physical (body weight, visceral fat weight and food intake) and biochemical parameters particularly plasma lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL-C and triglycerides) were in line with those observed in adult rats experiment, in addition to a significant reduction in the epidydimal white adipose pads94. As most of the changes were similar to those observed in adult rat experiment, we focused our attention on insulin resistance, which showed significant improvement by high vitamin A-diet feeding, especially in obese phenotype.

(ii) Effect on insulin resistance: As described earlier, obese rats of this strain are euglycaemic and hyperinsulinaemic. Surprisingly, fasting circulatory insulin levels were significantly decreased in obese rats fed on vitamin A enriched diet, while fasting glucose levels remained unaltered, resulting in improved insulin sensitivity index94. To understand the mechanism of vitamin A-mediated amelioration of insulin resistance in obese rat, expression of muscle insulin signaling pathway proteins was studied. A significant increase in the ratio of phosphorylated insulin receptor (pIR) to insulin receptor (IR), with concomitant decrease in protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) levels as compared to their stock diet-fed obese rats was observed94.

Further, soleus muscle fatty acid composition of obese rats fed on vitamin A-enriched diet revealed that fatty acid desaturation index [the ratio of palmitoleic to palmitic (16:1/16:0) acid of triglyceride (TG) and phospholipid (PL) fractions] showed significant decrease, especially with undetectable 16: 1 levels of PL fraction, with concomitant decrease in the protein expression of SCD1 in muscle (whose levels were found to be high in control obese rats as compared to their lean counterparts). Vitamin A had no impact on the expression of some important glucogenic, lipogenic and fatty acid oxidative pathway proteins such as phosphoenol pyruvate carboxy kinase (PEPCK), glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4), fatty acid synthase (FAS), long chain fatty acid CoA synthases 4 and 5 (ACSL 4 & 5), fatty acid binding protein (FABP), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)and phosphorylated AMPK (pAMPK)(94).

Besides its lipogenic nature, SCD1 is also known to affect the insulin sensitivity95. A study on SCD1 knockout mice demonstrated that SCD1 deficiency resulted in decreased PTP1B expression resulting in higher tyrosine phosphorylation of IR, IR substrates 1 and 2, and thus improved glucose clearance and insulin sensitivity96. PTP1B is proven to be an important physiological regulator of insulin action, as it directly interacts with IR and attenuates the insulin signaling by dephosphorylating tyrosine phosphorylated proteins. Dysregulation of PTP1B is associated with insulin resistance in both human and experimental animals97,98.

Summary and future perspectives

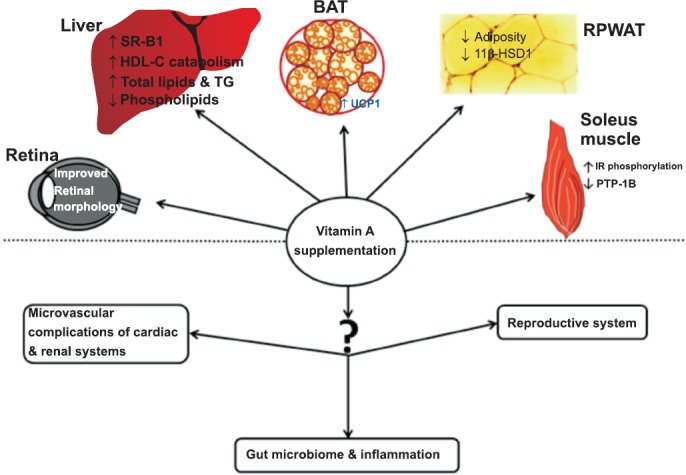

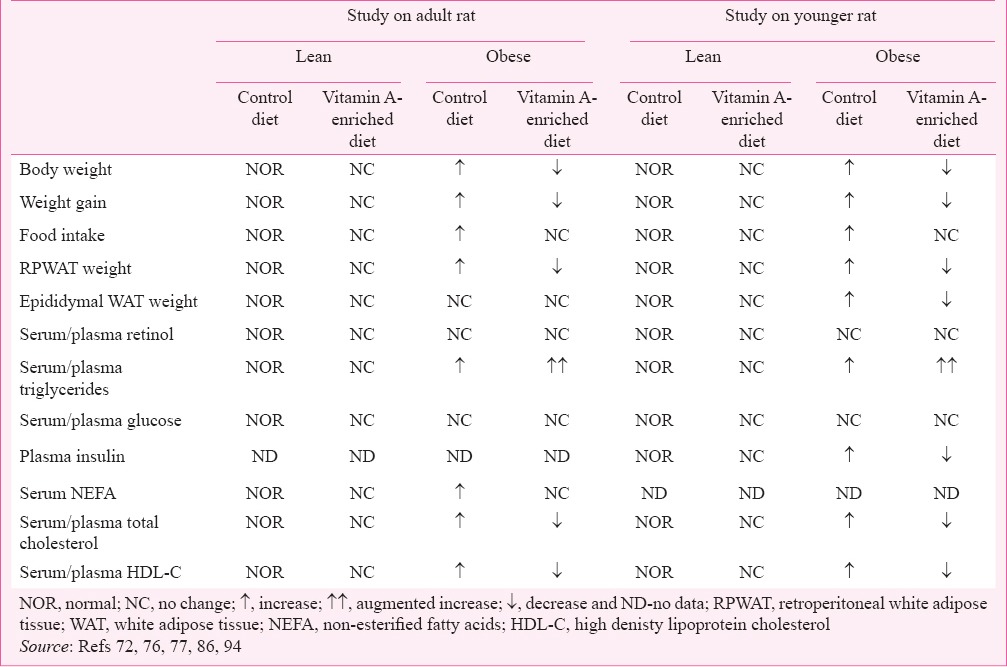

Overall, chronic vitamin A-enriched diet feeding significantly impacted the obesity development both in young and adult obese rats of WNIN/Ob strain, possibly through thermogenic and glucocorticoid pathways without eliciting any toxic symptoms. Further, vitamin A improved the HDL-C metabolism by hepatic SR-B1 mediated reverse cholesterol transport mechanism. However, high doses of vitamin A aggravated hypertriglyceridaemia in obese rats and induced it in lean rats. This is the only negative aspect of vitamin A supplementation study on obesity. Though the mechanism is not known, further studies are in progress to test the minimum effective dose, which brings about the beneficial effects, devoid of deleterious effect, i.e. hypertriglyceridaemia in these obese rats. Though, insulin sensitivity status in adult rats by vitamin A was not studied, at younger age long-term vitamin A supplementation was found to be beneficial by improving insulin sensitivity through insulin receptor phosphorylation due to downregulation of PTP1B protein expression. The findings from our studies demonstrate that chronic challenging of obese rats with vitamin A-enriched diet ameliorates obesity and its associated complications by regulating different pathway genes of liver, retroperitoneal white adipose tissue, brown adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and retina (Figure). Importantly, no symptoms of vitamin A toxicity, such as reduced food intake, depressed growth, alopecia, paralysis of legs and occasional bleeding from nose in either of the phenotypes were observed in our studies and impact of vitamin A-enriched diet on some of the clinical and biochemical parameters is given in the summary Table.

Fig.

Impact of vitamin A supplementation on various organs. Schematic picture showing the effect of vitamin A supplementation on obesity and its associated disorders and scope for the further research. RPWAT, retroperitoneal white adipose tissue; BAT, brown adipose tissue; SRB1, scavenger receptor class B1, UCP1, uncoupling protein 1; 11β-HSD1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase1; IR, insulin receptor; PTP1B, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B.

Table.

Summary of impact of vitamin A-enriched diet on clinical/biochemical parameters

Last decade has evidenced extensive research by relating vitamin A status and adiposity, thereby attributing a novel role to this vitamin and lot more functions yet to be unraveled. As of now, no study has addressed the role of vitamin A on inflammation per se, associated with obesity and explored the plausible underlying mechanisms. Therefore, impact of vitamin A status/supplementation on the gut microbiome and inflammation in obesity is an important area of research, which has direct implication on human health. Also, its role in other obesity-associated morbidities such as impaired reproductive performance and micro-vascular complications of cardiac and renal systems are largely unexplored. Many studies including ours are mostly centric towards adipose tissue and to some extent to liver and muscle; thereby leaving the other tissue physiology unexplored. Hence, the researchers should try to fill-up these knowledge gaps and elucidate the role of vitamin A in maintaining optimal health and alleviation of various disease processes.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by ICMR-Intramural grant.

References

- 1.De Luca LM. Retinoids and their receptors in differentiation, embryogenesis, and neoplasia. FASEB J. 1991;5:2924–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyatt GA, Dowling JE. Retinoic acid – a key molecule for eye and photoreceptor development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1471–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zile MH. Function of vitamin A in vertebrate embryonic development. J Nutr. 2001;131:705–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Ambrosio DN, Clugston RD, Blaner WS. Vitamin A metabolism: an update. Nutrients. 2011;3:63–103. doi: 10.3390/nu3010063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey SK, Vogel S. Vitamin A metabolism and adipose tissue biology. Nutrients. 2011;3:27–39. doi: 10.3390/nu3010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasmeen R, Jeyakumar SM, Reichert B, Yang F, Ziouzenkova O. The contribution of vitamin A to autocrine regulation of fat depots. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziouzenkova O, Orasanu G, Sharlach M, Akiyama TE, Berger JP, Viereck J, et al. Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat Med. 2007;13:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nm1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghyselinck NB, Båvik C, Sapin V, Mark M, Bonnier D, Hindelang C, et al. Cellular retinol-binding protein I is essential for vitamin A homeostasis. EMBO J. 1999;18:4903–14. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Gudas LJ. Disruption of the lecithin:retinol acyltransferase gene makes mice more susceptible to vitamin A deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40226–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N, Preitner F, Peroni OD, Zabolotny JM, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–62. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, Hu P, Krois CR, Kane MA, Napoli JL. Altered vitamin A homeostasis and increased size and adiposity in the rdh1-null mouse. FASEB J. 2007;21:2886–96. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7964com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hessel S, Eichinger A, Isken A, Amengual J, Hunzelmann S, Hoeller U, et al. CMO1 deficiency abolishes vitamin A production from beta-carotene and alters lipid metabolism in mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33553–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isken A, Golczak M, Oberhauser V, Hunzelmann S, Driever W, Imanishi Y, et al. RBP4 disrupts vitamin A uptake homeostasis in a STRA6-deficient animal model for Matthew-Wood syndrome. Cell Metab. 2008;7:258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moise AR, Lobo GP, Erokwu B, Wilson DL, Peck D, Alvarez S, et al. Increased adiposity in the retinol saturase-knockout mouse. FASEB J. 2010;24:1261–70. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National task force on the prevention and treatment of obesity. Overweight obesity and health risk. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:898–904. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2011;70:3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karasu SR. Of mind and matter: psychological dimensions in obesity. Am J Psychother. 2012;66:111–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2012.66.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawada T, Takahashi N, Fushiki T. Biochemical and physiological characteristics of fat cell. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2001;47:1–12. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.47.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frayn KN, Karpe F, Fielding BA, Macdonald IA, Coppack SW. Integrative physiology of human adipose tissue. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:875–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsutsumi C, Okuno M, Tannous L, Piantedosi R, Allan M, Goodman DS, et al. Retinoids and retinoid-binding protein expression in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurlandsky SB, Gamble MV, Ramakrishnan R, Blaner WS. Plasma delivery of retinoic acid to tissues in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17850–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villarroya F, Giralt M, Iglesias R. Retinoids and adipose tissue: Metabolism, cell differentiation and gene expression. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeyakumar SM, Yasmeen R, Reichert B, Ziouzenkova O. Metabolism of vitamin A in white adipose tissue and obesity. In: Sommerburg O, Siems W, Kraemer K, editors. Carotenoids and vitamin A in translational medicine. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2013. pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonet ML, Ribot J, Felipe F, Palou A. Vitamin A and the regulation of fat reserves. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1311–21. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2290-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichert B, Yasmeen R, Jeyakumar SM, Yang F, Thomou T, Alder H, et al. Concerted action of aldehyde dehydrogenases influences depot-specific fat formation. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:799–809. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sima A, Manolescu DC, Bhat P. Retinoids and retinoid-metabolic gene expression in mouse adipose tissues. Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;89:578–84. doi: 10.1139/o11-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4153–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:461S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kershaw KE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2548–56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hajer GR, van Haeften TW, Visseren FLJ. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity, diabetes, and vascular diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2959–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–70. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Havel PJ. Update on adipocyte hormones: regulation of energy balance and carbohydrate/lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2004;53:S143–S51. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahmouni K, Haynes WG. Leptin and the cardiovascular system. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:225–44. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seufert J. Leptin effects on pancreatic beta-cell gene expression and function. Diabetes. 2004;53:S152–S8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matarese G, Moschos S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in immunology. J Immunol. 2005;174:3137–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar MV, Scarpace PJ. Differential effects of retinoic acid on uncoupling protein-1 and leptin gene expression. J Endocrinol. 1998;157:237–43. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1570237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonet ML, Oliver J, Picó C, Felipe F, Ribot J, Cinti S, et al. Opposite effects of feeding a vitamin A-deficient diet and retinoic acid treatment on brown adipose tissue uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), UCP2 and leptin expression. J Endocrinol. 2000;166:511–7. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menendez C, Lage M, Peino R, Baldelli R, Concheiro P, Diéguez C, et al. Retinoic acid and vitamin D(3) powerfully inhibit in vitro leptin secretion by human adipose tissue. J Endocrinol. 2001;170:425–31. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong SE, Ahn IS, Jung HS, Rayner DV, Do MS. Effect of retinoic acid on leptin, glycerol, and glucose levels in mature rat adipocytes in vitro . J Med Food. 2004;7:320–6. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cassani B, Villablanca EJ, De Calisto J, Wang S, Mora JR. Vitamin A and immune regulation: role of retinoic acid in gut-associated dendritic cell education, immune protection and tolerance. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross AC. Vitamin A and retinoic acid in T cell-related immunity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1166S–72S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García OP, Long KZ, Rosado JL. Impact of micronutrient deficiencies on obesity. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:559–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García OP. Effect of vitamin A deficiency on the immune response in obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:290–7. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zulet AM, Puchau B, Hermsdorff HHM, Navarro C, Martinz JA. Vitamin A intake is inversely related with adiposity in healthy young adults. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2008;54:347–52. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.54.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aasheim ET, Hofso D, Hjelmesaeth J, Birkeland KI, Bohmer T. Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:362–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Botella-Carretero JI, Balsa JA, Vázquez C, Peromingo R, Díaz-Enriquez M, Escobar-Morreale HF. Retinol and alpha-tocopherol in morbid obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Obes Surg. 2010;20:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villaça Chaves G, Pereira SE, Saboya CJ, Ramalho A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its relationship with the nutritional status of vitamin A in individuals with class III obesity. Obes Surg. 2008;18:378–85. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pereira SE, Saboya CJ, Saunders C, Ramalho A. Serum levels and liver store of retinol and their association with night blindness in individuals with class III obesity. Obes Surg. 2012;22:602–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0522-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suano de Souza FI, Silverio Amancio OM, Saccardo Sarni RO, Sacchi Pitta T, Fernandes AP, Affonso Fonseca FL, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight children and its relationship with retinol serum levels. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2008;78:27–32. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.78.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Souza Valente da Silva L, Valeria da Veiga G, Ramalho RA. Association of serum concentrations of retinol and carotenoids with overweight in children and adolescents. Nutrition. 2007;23:392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moor de BA, Wartanowicz M, Ziemlanski S. Blood vitamin and lipid levels in overweight and obese women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46:803–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trayhurn P, Bing C, Wood IS. Adipose tissue and adipokines-energy regulation from the human perspective. J Nutr. 2006;136:1935S–9S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1935S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Z, Nakayama T. Inflammation, a link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Mediators Inflamm 2010. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/535918. 535918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiefer FW, Orasanu G, Nallamshetty S, Brown JD, Wang H, Luger P, et al. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 coordinates hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3089–99. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiefer FW, Vernochet C, O’Brien P, Spoerl S, Brown JD, Nallamshetty S, et al. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 regulates a thermogenic program in white adipose tissue. Nat Med. 2012;18:918–25. doi: 10.1038/nm.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills JP, Furr HC, Tanumihardjo SA. Retinol to retinol-binding protein (RBP) is low in obese adults due to elevated apo-RBPExp Biol Med (Maywood) Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:1255–61. doi: 10.3181/0803-RM-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graham TE, Yang Q, Bluher M, Hammarstedt A, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2552–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janke J, Engeli S, Boschmann M, Adams F, Böhnke J, Luft FC, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 in human obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:2805–10. doi: 10.2337/db06-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cho YM, Youn BS, Lee H, Lee N, Min SS, Kwak SH, et al. Plasma retinol-binding protein-4 concentrations are elevated in human subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2457–61. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee DC, Lee JW, Im JA. Association of serum retinol binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in apparently healthy adolescents. Metabolism. 2007;56:327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.von Eynatten M, Lepper PM, Liu D, Lang K, Baumann M, Naworth PP, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome, but not with insulin resistance, in men with type 2 diabetes or coronary artery disease. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1930–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Broch M, Vendrell J, Ricart W, Richart C, Fernandez-Real JM. Circulating retinol-binding protein-4, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin disposition index in obese and nonobese subjects. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1802–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murray T, Russell TR. Inhibition of adipose conversion in 3T3-L2 cells by retinoic acid. J Supramol Struct. 1980;14:255–66. doi: 10.1002/jss.400140214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamei Y, Kawada T, Mizukami J, Sugimoto E. The prevention of adipose differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells caused by retinoic acid is elicited through retinoic acid receptor alpha. Life Sci. 1994;55:PL307–12. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumar MV, Sunvold GD, Scarpace PJ. Dietary vitamin A supplementation in rats: suppression of leptin and induction of UCP1 mRNA. J Lip Res. 1999;40:824–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawada T, Kamei Y, Fujita A, Hida Y, Takahashi N, Sugimoto E, et al. Carotenoids and retinoids as suppressors on adipocyte differentiation via nuclear receptors. Biofactor. 2000;13:103–9. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bonet ML, Oliver J, Picó C, Felipe F, Ribot J, Cinti S, et al. Opposite effects of feeding a vitamin A-deficient diet and retinoic acid treatment on brown adipose tissue uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), UCP2 and leptin expression. J Endocrinol. 2000;166:511–7. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, Matheny M, Zolotukhin S, Tumer N, Scarpace PJ. Regulation of adiponectin and leptin gene expression in white and brown adipose tissues: influence of beta3-adrenergic agonists, retinoic acid, leptin and fasting. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1584:115–22. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeyakumar SM, Vajreswari A, Sesikeran B, Giridharan NV. Vitamin A regulates obesity in WNIN/Ob obese rats; independent of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:243–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalashikam RR, Battula KK, Kirlampalli V, Friedman JM, Nappanveettil G. Obese locus in WNIN/obese rat maps on chromosome 5 upstream of leptin receptor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harishankar N, Kumar PU, Sesikeran B, Giridharan N. Obesity associated pathophysiological & histological changes in WNIN obese mutant rats. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:330–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bandaru P, Rajkumar H, Nappanveettil G. Altered or impaired immune response upon vaccination in WNIN/Ob rats. Vaccine. 2011;29:3038–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jeyakumar SM, Vajreswari A, Sesikeran B, Giridharan NV. Vitamin A supplementation induces adipose tissue loss through apoptosis in lean but not in obese rats of the WNIN/Ob strain. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:391–8. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jeyakumar SM, Vajreswari A, Giridharan NV. Chronic dietary vitamin A supplementation regulates obesity in an obese mutant WNIN/Ob rat model. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:52–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeyakumar SM, Lopamudra P, Padmini S, Balakrishna N, Giridharan NV, Vajreswari A. Fatty acid desaturation index correlates with body mass and adiposity indices of obesity in Wistar NIN obese mutant rat strains WNIN/Ob and WNIN/GR-Ob. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2009;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sampath H, Ntambi JM. The role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase in obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dobrzyń P. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase in the control of metabolic homeostasis. Postepy Biochem. 2012;58:166–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakamuri VP, Ananthathmakula P, Veettil GN, Ayyalasomayajula V. Vitamin A decreases pre-receptor amplification of glucocorticoids in obesity: study on the effect of vitamin A on 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity in liver and visceral fat ofWNIN/Ob obese rats. Nutr J. 2011;10:70. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Standeven AM, Beard RL, Johnson AT, Boeham MF, Escobar M, Heyman RA, et al. Retinoid-induced hypertriglyceridemia in rats is mediated by retinoic acid receptors. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996;33:264–358. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davies PJ, Berry SA, Shipley GL, Eckel RH, Hennuyer N, Crombie DL, et al. Metabolic effects of rexinoids: tissue-specific regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:170–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Staels B. Regulation of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism by retinoids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S158–67. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valacchi G, Sticozzi C, Lim Y, Pecorelli A. Scavenger receptor class B type I: a multifunctional receptor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1229:E1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeyakumar SM, Vajreswari A, Giridharan NV. Impact of vitamin A on high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and scavenger receptor class BI in the obese rat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:322–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adams MK, Simpson JA, Aung KZ, Makeyeva GA, Giles GG, English DR, et al. Abdominal obesity and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1246–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peeters A, Magliano DJ, Stevens J, Duncan BB, Klein R, Wong TY. Changes in abdominal obesity and age-related macular degeneration: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1554–60. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Klein BEK, Klein R, Lee KE, Jenson SC. Measures of obesity and age-related eye diseases. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8:251–62. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.4.251.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reddy GB, Vasireddy V, Mandal MN, Tiruvalluru M, Wang XF, Jablonski MM, et al. A novel rat model with obesity-associated retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3456–63. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marçal AC, Leonelli M, Fiamoncini J, Deschamps FC, Rodrigues MA, Curi R, et al. Diet-induced obesity impairs AKT signalling in the retina and causes retinal degeneration. Cell Biochem Funct. 2013;31:65–74. doi: 10.1002/cbf.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reddy PY, Giridharan NV, Reddy GB. Activation of sorbitol pathway in metabolic syndrome and increased susceptibility to cataract in Wistar-obese rats. Mol Vis. 2012;18:495–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tiruvalluru M, Ananthathmakula P, Ayyalasomayajula V, Nappanveettil G, Ayyagari R, Reddy GB. Vitamin A supplementation ameliorates obesity-associated retinal degeneration in WNIN/Ob rats. Nutrition. 2013;29:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jeyakumar SM, Vijaya Kumar P, Giridharan NV, Vajreswari A. Vitamin A improves insulin sensitivity by increasing insulin receptor phosphorylation through protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B regulation at early age in obese rats of WNIN/Ob strain. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:955–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.García-Serrano S, Moreno-Santos I, Garrido-Sánchez L, Gutierrez-Repiso C, García-Almeida JM, García-Arnés J, et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 is associated with insulin resistance in morbidly obese subjects. Mol Med. 2011;17:273–8. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rahman SM, Dobrzyn A, Dobrzyn P, Lee SH, Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 deficiency elevates insulin-signaling components and down-regulates protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11110–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934571100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Elchebly M, Payette P, Michaliszyn E, Cromlish W, Collins S, Loy AL, et al. Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B gene. Science. 1999;283:1544–8. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Klaman LD, Boss O, Peroni OD, Kim JK, Martino JL, Zabolotny JM, et al. Increased energy expenditure, decreased adiposity, and tissue-specific insulin sensitivity in protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5479–89. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5479-5489.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]