Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To test the hypothesis that since mild cognitive impairment (MCI), believed to be an intermediary state on the way to, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are both neurodegenerative, quantification of the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in their whole brain (WBNAA) could differentiate them from cognitively intact matched controls.

METHODS

Proton MR spectroscopy to quantify the WBNAA was applied to 197 subjects (86 females) 72.6±8.4 years old (mean±standard deviation). Of these, 102 were cognitively intact, 42 diagnosed as MCI and 53 as probable AD. Their WBNAA amounts were converted into absolute concentration by dividing with the brain volume segmented from the MRI that also yielded the fractional brain volume (fBPV), an atrophy metric.

RESULTS

WBNAA concentration of MCI and AD patients (10.5±3.0 and 10.1±2.9mM) were not significantly different (p=0.85), they were, however, highly significantly 25–29% lower than the 14.1±2.4mM of normal matched controls (p‹10−4). The fBPV of MCI and AD patients (72.9±4.9 and 69.9±4.7%) differed significantly from each other (4%, p=0.02) and both were significantly lower than the 74.6±4.4% of normal elderly (2%, p=0.003 for MCI; 6%, p‹10−4 for AD). ROC curve analysis has shown WBNAA to have 70.5% sensitivity and 84.3% specificity to differentiate MCI or AD patients from normal elderly versus just 68.4 and 65.7% for fBPV.

CONCLUSION

Low WBNAA in MCI patients compared with cognitively normal contemporaries may indicate early neuronal damage accumulation and supports the notion of MCI as an early stage of AD. It also suggests WBNAA as a potential marker of early AD pathology.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, N-acetylaspartate, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, normal aging

INTRODUCTION

Neuropathological studies have shown Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) to follow a stagewise progressive course involving the medial temporal lobe and subsequently spread to temporal and parietal cortex [1]. Clinically, the decline into AD is thought to proceed through an intermediate stage of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) characterized by subjective memory complaints accompanied by decline in memory or other cognitive domain performance but preserved general intellectual function and absence of dementia [2–4]. Estimated to be tenfold more common than AD, MCI affects anywhere from 12.5% to as high as 21.8% of the elderly [5–7]. Indeed, while the annual incidence rates of AD in normal elderly are under 5% [8–10], they are estimated at 10% in MCI, especially of the amnestic type [3, 8]. These estimates are even higher in clinical settings [11]. Since MCI is associated with greater mortality [12, 13] and risk to develop AD [3, 3], it is clearly of special public health interest.

Despite growing relevance of MCI to public health, its diagnostic criteria and neuroimaging features are still debated. This may be due at least in part to the several identified subtypes (amnestic, non-amnestic, single or multiple domains) that may also help explain the variable courses [4]. For example, 10 to 20% of individuals initially diagnosed as MCI revert to “normal” at follow-up [8–10]. Consequently, early detection is difficult, partly due to the lack of well-established, non-invasive markers not necessitating radiation exposure. This can confound proper selection of patients who could benefit from early interventions.

Post mortem examinations show more than half of the subjects with MCI have a Braak stage of III/IV [14]. While these involve mostly entorhinal and transentorhinal regions, neurofibrillary tangles were already found in the striatum, thalamus and isocortex [1]. Over half the MCI patients in that study also met the consortium to establish a registry for AD (CERAD) criteria for probable or definite AD [14]. Similarly, although imaging indicates that AD manifests first in medial temporal lobe morphology, abnormalities in MCI are not limited to the hippocampus [15]. In fact, multiple white matter (WM) regions in all lobes exhibited diffusion properties [16–18] and magnetization transfer differences from controls [18, 19]. These reports all suggest widespread cortical and subcortical pathology already in the prodromal stage, warranting examination of multiple regions or global changes.

Since MCI and AD target neuronal cells, progression could be monitored via their specific marker, the amino-acid derivative N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA), whose prominent peak in proton MR spectroscopy (1H-MRS) of the mammalian brain makes it simple to quantify [20, 21]. Its decline reported for all CNS disorders [22] is most commonly seen in hippocampi and middle temporal lobes of AD and MCI patients [23, 24] but also reported in paratrigonal WM and the posterior cingulate [25, 26]. The diffuse nature and the neuronal substrate of NAA, render its whole-brain (WBNAA) quantification well suited to track the total disease load [27, 28] in order to distinguish normal from MCI and AD, as shown by Falini et al. [29]. To our knowledge, however, no other study has compared WBNAA among these three diagnostic groups. Consequently, in the present study we examine the WBNAA levels in large cohorts of normal elderly, MCI and AD patients to test three hypotheses: (i) That MCI patients’ WBNAA is lower than cognitively intact normal contemporaries. (ii) That AD patients’ WBNAA is lower than MCI. (iii) That these WBNAA levels are sufficiently different to enable unique assignment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

I. Human Subjects

One hundred and ninety seven elderly (111 males, 86 females), recruited from the Memory Clinic, Dept. of Geriatrics, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, were enrolled. Of these 102 [(64 men and 38 women), 72.4 ± 8.3 (51 to 89) years old] were deemed cognitively normal based on extensive neuropsychological testing (see below). Forty two individuals [(24 men and 18 women) 70.8 ± 7.8 (50 to 84) years old] fulfilled criteria for MCI [4] and 53 subjects [(23 men and 30 women) 74.9 ± 8.6 (49 to 89) years old] met the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD [30]. All participants gave written Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent.

General cognitive abilities in all subjects were assessed with Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [31]. Screening for depression was performed with Geriatric Depression Scale [32], where a cutoff score of 5 determined lack of depressive symptoms, a cutoff of 10 separated mild and severe depressive symptoms. Subjects scoring higher than 10 were excluded. A battery of cognitive tests was administered. California Verbal Learning Test [33] or CERAD Word List [34] or Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure, Immediate and Delayed Recall [35] or CERAD Figures - Delayed Recall [34] were used interchangeably to assess episodic memory. Digit span and Corsi blocks [36] allowed for working memory evaluation. Computerized test of attention [37], Stroop Color-Word Interference Test, Card 1 [38] and Trail Making Test, Part A [39] were used to examine attention and cognitive speed. Language was assessed with Boston Naming Test [40], category [41] and phonemic fluency tests [42]. Visuospatial abilities were evaluated with Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure, Copy [35] or CERAD Figures, Copy [43] and Clock Drawing Test [44]. Executive functions were assessed with Trail Making Test, Part B [39], Stroop Color-Word Interference Test, Card 3 [38] and Design Fluency [45]. To confirm subject’s cognitive status a knowledgeable informant was questioned using a shortened 16- item version of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQ-CODE) [46].

The diagnosis of MCI was based on the criteria proposed by Winblad et al. [4]. According to these criteria among the 42 participants with MCI, 35 were diagnosed as amnestic multiple domain MCI, 2 as amnestic single domain, 3 as non-amnestic multiple domain and 2 as non-amnestic single domain. The diagnosis of AD was based on the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria, where subjects experienced progressive decline in at least two cognitive domains including memory and impaired functioning, not attributed to other causes of cognitive deterioration [30].

II. MR Acquisition

All measurements were done in a 3 Tesla MR head scanner (Magnetom Allega, Siemens AG, Erlangen Germany) using its standard transmit-receive head coil. After placing each subject head-first, supine into the magnet, localizer images in three orthogonal orientations were obtained to verify correct head placement. The magnetic field homogeneity was then adjusted over the whole head, followed by T1-weighted sagittal Magnetization Prepared RApid Gradient Echo (MP-RAGE) [TE/TR/TI: 3.49/2150/ 1000 ms, 7° tip angle, 144 slices 1.1 mm thick, and 256×224 matrix over a 280×245 mm2 field-of-view (FOV) for 1.1 mm isotropic spatial resolution] MRI for brain volumetry.

The amount of brain NAA, QNAA, was obtained with non-localizing TE/TI/TR=0/940/104 ms 1H-MRS [28]. The TR»T1 and TE≈0 yield the insensitivity to T1 and T2 variations that is desirable in pathologies where neither is likely to be known.

III. Brain volumetry

Each subject’s brain tissue volume, VB, was segmented from the MP–RAGE images using our in-house FireVoxel software [47]. The automatically detects of a “seed” region in periventricular WM to yield its signal intensity, IWM, as shown in Fig. 1. Following selection of all pixels at or above 55% (but below 135% to exclude fat) of IWM, a tissue-mask is constructed in three steps: (i) morphological erosion, (ii) recursive region growth retaining pixels connected to the “seed;” and (iii) morphological inflation to reverse the effect of erosion. Pixels of intensity under 55% of IWM are defined as CSF. The sum of the pixels in all tissue-masks multiplied by their volume yields VB. The precision of this process (the agreement between segmentation results for the same head from multiple scans) for T1-weighted MRI has been recently quantified at 3.4% [47].

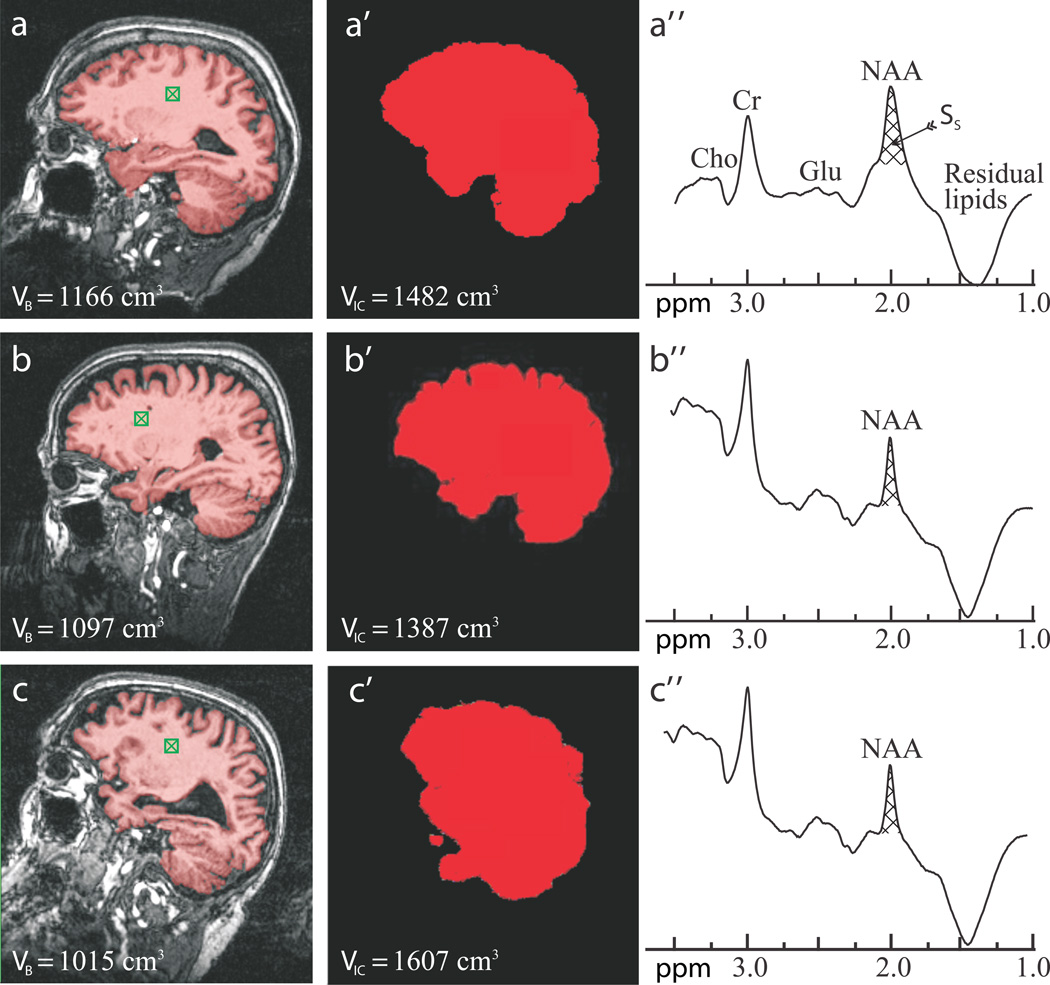

Fig. 1.

Sample FireVoxel and MRIcro segmentation used for VB and VIC (indicated on the images) and whole-head NAA spectra (not normalized for VB) from one subject from each cohort: 73 year old normal woman (a, a’, a”), 73 year old female MCI (b, b’, b”); and 80 year old male AD patient (c, c’, c”). Note the “seed” in the white matter (green hatched box in a – c), brain-capture performance of FireVoxel (a – c); intracranial volume capture of MRIcro (a’ – c’) and well defined whole-head 1H spectra (a” – c”) for straightforward integration of Ss for Eq. [1]. Note the NAA peak at 2 ppm, lipids suppression performance and that of all the other peaks in the spectrum, e.g., glutamate (Glu), total creatine (Cr) and total choline (Cho) only NAA is implicitly localized by its biochemistry to just the brain.

The intracranial (brain + CSF) volume, VIC, was estimated using MRIcro, a free downloadable segmentation package: http://www.mricro.com [48]. It subtracted the cranium from the images using a “skull strip” tool leaving behind a mask of just brain and CSF. VIC is the pixels’ volume × their number in the mask and the fractional brain parenchyma volume (fBPV) is VB/VIC × 100.

IV. Whole-brain NAA (WBNAA) quantification

Absolute quantification was done with phantom-replacement against a reference 3 L sphere of 1.5×10−2 mole NAA in water. Subject and reference NAA peak areas, SS and SR, were obtained by manual phasing and selection of the NAA peak limits of integration using our in-house software, as shown in Fig. 1a, by four operators blinded to each other’s result. A result more than two average standard deviations (for the four readers’ over all the patients, ~8%) from the mean for that patient, was rejected. If more than one was rejected than that entire set was excluded as “poor quality.” The results were then averaged into and and QNAA estimated as [28],

| [1] |

, where and are the transmitter voltages for non-selective 1 ms 180° inversion pulses on the reference and subject. Note that although macromolecules and other N-acetyl species also resonate around 2 ppm [49], their contribution to that peak area is estimated at under 10% [50].

To normalize for differences in brain size among subjects, QNAA was divided by the brain parenchyma volume, VB, to yield the whole-brain NAA concentration:

| [2] |

This is a specific (brain size independent) metric and its inter- and intra-subject variability in younger healthy individuals has been shown to be better than ±8% [51]. The whole head NAA (WHNAA) concentration, a marker of NAA atrophy, was then estimated as,

| [3] |

that is sensitive to both atrophy as well as the NAA concentration in the remaining tissue.

V. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance based on ranks was used to compare diagnostic groups in terms of the three study endpoints: fBPV, WBNAA and WHNAA (separate analysis for each). In each case, the observed values of the endpoint were converted to ranks used as the dependent variable in order to satisfy underlying distributional assumptions. P values are reported for the comparisons with adjustment for potential confounding effects of age, gender and multiple comparisons. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to assess and compare study endpoints utility to discriminate cognitively impaired (groups 2 and 3) from normal (group 1). A statistical jackknife procedure was used to compare endpoints with respect to area under the ROC curve (AUC) while a McNemar test was used to compare endpoints in terms of the diagnostic accuracy when selected threshold values were used as test criterion for diagnosis of cognitive impairment. Results were declared significant if associated with a two-sided p value under 0.05. SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

The original data set consisted of 225 subjects. 28 of them (16 NL, 5 MCI and 7 AD) failed the WBNAA data quality criterion described in section “IV Whole-brain NAA (WBNAA) quantification,” above and were, consequently, excluded from the analyses. Thus the final set included 197 subjects.

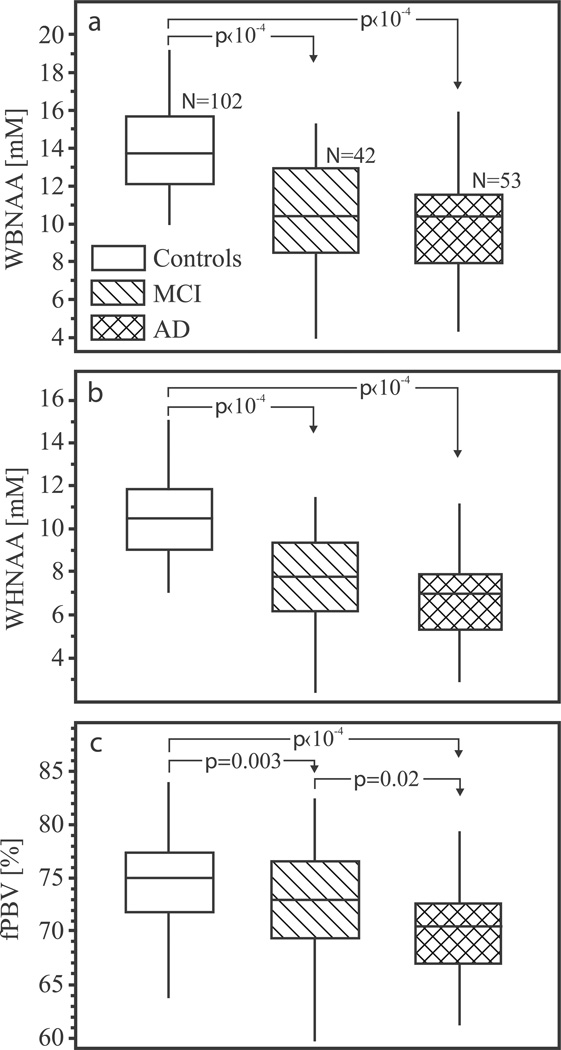

The WBNAA concentrations (mean±standard deviation) were 14.1±2.4, 10.5±3.0 and 10.1±2.9 mM for normal elderly, MCI and AD patients, as shown in Fig. 2a. While the MCI and AD patients means were not statistically different (p=0.85), they were highly significantly lower than normal contemporaries’ (25%, p‹10−4 for MCI; 29% p‹10−4 for AD).

Fig. 2.

Top, a: Box plots showing the first, second (median) and third quartiles (box) and ±95% (whiskers) of the WBNAA distribution in the three groups. Note highly significant 25% lower WBNAA for MCI and AD versus their normal contemporaries (arrows).

Center, b: Same for the WHNAA distribution. Note the highly significantly 30% lower WHNAA for MCI and AD patients versus their normal controls (but not each other).

Bottom, c: Same for the fBPV. Note the significant difference between MCI and AD patients both of whom are highly significant lower ~5%, than normal contemporaries.

The WHNAA concentrations were 10.5±2.0, 7.6±2.2 and 7.0±2.1 mM for normal elderly, MCI and AD patients, as shown in Fig. 2b. Again, no significant difference was observed between the means of the MCI and AD patients (p=0.37) but each was highly significantly lower than the controls’ (27%, p‹10−4 for MCI group; 31% p‹10−4 for AD group).

The fBPVs were 74.6±4.4, 72.9±4.9, 69.9±4.7% for the normal, MCI and AD patients, as shown in Fig. 2c. As expected, compared to normal controls fBPVs were significantly lower in MCI (2%, p=0.003) and AD patients (6%, p‹10−4). Moreover, the MCI and AD groups also differed significantly from each other (4%, p=0.02). All p values are adjusted for age and gender which, therefore, played no role in the differences observed among the cohorts.

All relationships remained virtually unchanged when analyses were repeated after exclusion of non-amnestic MCI patients.

We re-analyzed our data with ANCOVA using actual and log transformed values for WBNAA, WHNAA and fractional brain parenchymal volume. The overall results and between group differences (adjusted for multiple comparisons) remained the same:

WBNAA actual values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=48.9, p<10−4. There was no difference between MCI and AD (p=1.00), however both MCI and AD differed from the NL group at p<10−4.

WBNAA log transformed values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=45.9, p<10−4. There was no difference between MCI and AD (p=1.00), however both MCI and AD differed from the NL group at p<10−4.

WHNAA actual values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=62.4, p<10−4. There was no difference between MCI and AD (p=.57), however both MCI and AD differed from the NL group at p<10−4.

WHNAA log transformed values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=57.5, p<10−4. There was no difference between MCI and AD (p=.48), however both MCI and AD differed from the NL group at p<10−4.

fBPV actual values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=24.2, p<10−4. MCI had smaller fBPV than the NL group (p=.006), AD had smaller fBPV than both NL (p<10−4) and MCI group (p=.01).

fBPV log transformed values, ANCOVA adjusted for age and gender F4,192=23.8, p<10−4. MCI had smaller fBPV than the NL group (p=.007), AD had smaller fBPV than both NL (p<10−4) and MCI group (p=.01).

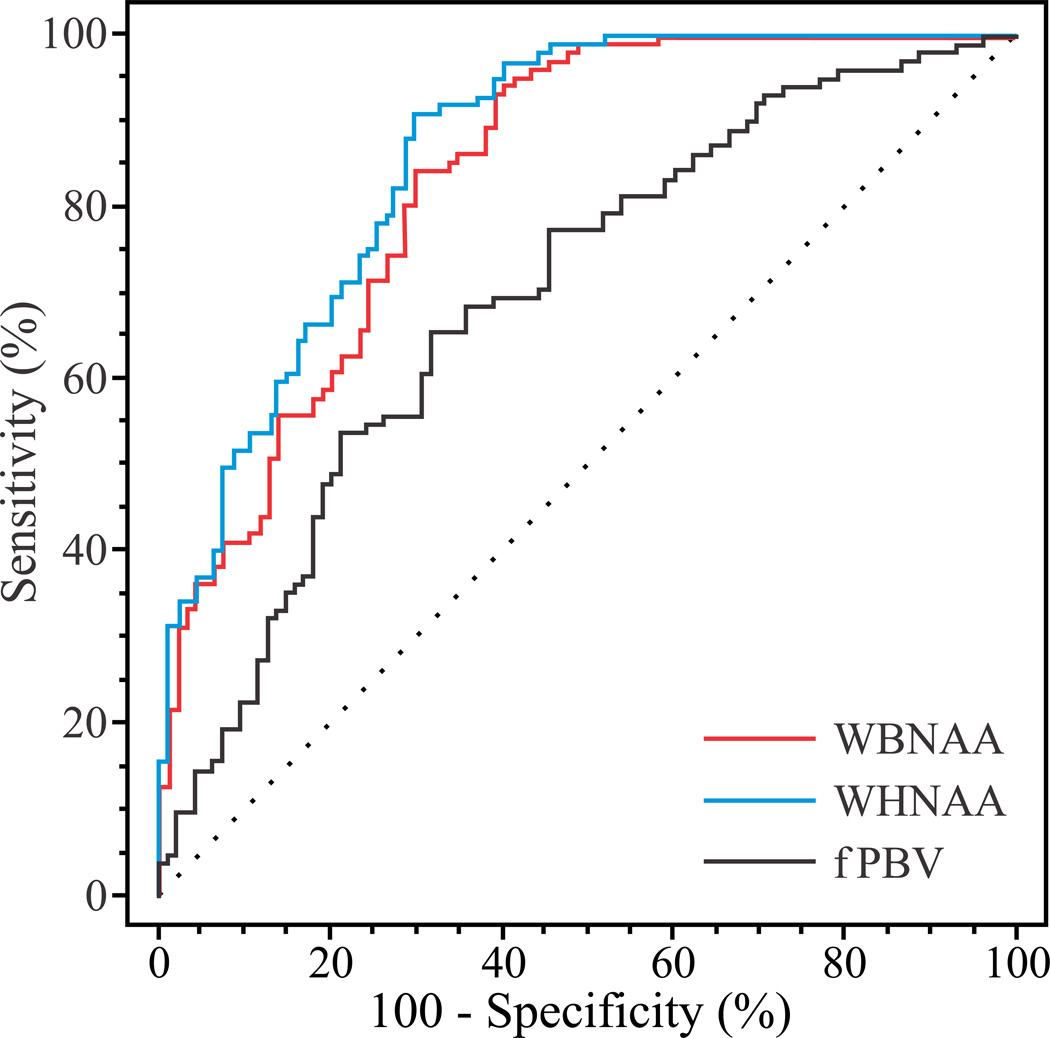

The AUC of the ROC curves in Fig. 3 were: 0.84, 0.87 and 0.70 for the WBNAA, WHNAA and fBPV. The maximum sensitivity and specificity for these metrics were: 84.3% and 70.5% for WBNAA, 91.2% and 70.5% for WHNAA, and 65.7% and 68.4% for fBPV. Based on the McNemar tests their maximum accuracy are 77.7% (p=0.033), 81.2% (p=0.001) versus 67.0%. No significant difference was noted between WBNAA and WHNAA for the highest accuracy.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves for the WBNAA, WHNAA and fBPV (red, blue and black solid lines). The dotted diagonal line represents the probability of a random event. The further a curve is from this diagonal, the greater its AUC, consequently its sensitivity. Note the greater area (i.e., predictive value) under the WBNAA and WHHAA curves compared with the fBPV.

The AUC of the ROC curves for separation between NL and MCI groups were all significant: 0.81, 0.83 and 0.61 for the WBNAA, WHNAA and fBPV, respectively. The maximum sensitivity and specificity for these metrics were: 80.4% and 64.3% for WBNAA, 88.2% and 64.3% for WHNAA and 65.7% and 57.1% for fBPV.

Similarly, as expected the AUC of the ROC curves for separation between NL and AD groups were all significant: 0.86, 0.89 and 0.77 for the WBNAA, WHNAA and fBPV, respectively. The maximum sensitivity and specificity for these metrics were: 86.3% and 71.1% for WBNAA, 92.2% and 77.4% for WHNAA and 69.6% and 71.7% for fBPV.

Finally, neither the WBNAA nor the WHNAA provided separation between MCI and AD groups. The AUC for fBPV was 0.66 with 61.9% sensitivity and 60.4% specificity.

DISCUSSION

The neurodegenerative nature of AD has been consistently demonstrated by (local) NAA decrease in various gray and white matter brain regions [23–26]. It is interesting, therefore, that (i) significant WBNAA decline (reflecting brain issue “quality”) is already present at MCI; which (ii) is not statistically different from AD. Since our MCI group was predominantly amnestic, our findings support the view that this type of MCI constitutes a prodromal stage of AD. This finding is corroborated by the WHNAA, a metric of “NAA atrophy” that accounts for both the reduction in parenchyma volume (quantity) and NAA concentration decrease in the remaining tissue (quality). The WHNAA followed the pattern of the WBNAA among the three cohorts but was consistently lower by about 2%, i.e., by the corresponding fBPV differences.

Together with neuropathological similarities between MCI and AD patients [52] and the fact that 10 – 15% of MCI patients convert to AD annually [3], our results support the notion that MCI is not just a transitory stage but rather an early manifestation of AD pathology [2].

Most interestingly changes in NAA were not fully reflected in fBPV measurements. First, it is noteworthy that MCI subjects were situated in between NL and AD group. Second, while the fBPV differences were of the order of 5%, WBNAA and WHNAA were fivefold larger, 25 – 30%. The tissue loss quantified by the fBPV represents an end stage of many pathological processes. Consequently, it is less specific than NAA decline which is a unique marker to neuronal dysfunction and loss. This may help explain the higher sensitivity and specificity of both WBNAA and WHNAA (Fig. 3).

This higher sensitivity may also be attributed to NAA physiology. Specifically, since its production is coupled to ATP synthesis [20], the energy metabolism decline that is known to occur early in the course of AD [53] may also depress the NAA concentration, indicating that functional decline precedes structural damage. Second, the reactive gliosis that accompanies atrophy [54] may mitigate the true extent of neuronal loss biasing the fBPV. Since glial cells do not contain NAA, WBNAA and WHNAA are both insensitive to this bias. Consequently, WBNAA along with other biological markers and clinical tests may present an earlier, more complete picture of the severity and evolution of the disease in any given patient.

The performance of both WBNAA and WHNAA as diagnostic markers merits further discussion. First, although the highest accuracy of either did not differ significantly, the WHNAA AUC was slightly higher, probably reflecting the combined contributions of tissue-quality and volume decline. Second, the diagnostic accuracy for either metric was commensurate with the 85% reported by most volumetric studies focusing on medial temporal structures to discriminate between normal and AD. It is actually higher than most reports comparing these structures between normal and MCI [see review in [15]]. In this regard information on WBNAA and WHNAA is desirable in conjunction with standard diagnostic imaging to exclude alternative pathologies and providing indications for neuronal damage beyond normal ageing process.

When discrimination accuracy for the 3 metrics was examined for individual diagnostic groups, the separation with WBNAA and WHNAA was significant between AD and NL, and MCI and NL groups, but not between MCI and AD subjects. However, this is expected given the comparable levels of WBNAA and WHNAA in both impaired groups.

Furthermore, diagnosis of MCI is currently based on clinical algorithms, e.g., history, mental status exams and neuropsychiatric tests [4] and is accompanied by common uncertainties related among others to the contribution of depression, anxiety and concurrent medications. Therefore, WBNAA augment the diagnostic MRI (used to exclude other pathologies) with additional level of confidence for presence of pathologic but MRI-occult tissue changes.

Admittedly, this study is subject to several limitations due to a methodology designed to maximize the intrinsically low sensitivity of 1H-MRS and speed up its acquisition. Specifically, since WBNAA, WHNAA and fBPV are all global averages, they are insensitive to (multi) focal or regional pathologies. Changes, therefore, must be spatially extensive enough to affect the average by the 8 – 10% intrinsic sensitivity [51]. Disorders that preferentially (or initially) target small regions, e.g., temporal structures in MCI or AD [55], therefore, may go undetected until that threshold is crossed. Moreover, although the technique provides quick and reliable estimate of WBNAA it comes at the cost of missing all other metabolites, e.g., Cho, Cr and Glu, as shown in Fig. 1c”. This is because these metabolites, unlike NAA, have signal contributions from other tissue types of the head and the brain’s contribution to their signal cannot be separated with this non-localizing sequence. Thus we could not compare the discriminatory values of these other metabolites to that of WBNAA. Finally, since vascular co-morbidities were not quantified, possible differences in their loads are unaccounted for in any of the cohorts. A larger (for more statistical power) study of MCI that compares these subtypes may indicate whether the WBNAA can detect or differentiate these subgroups.

CONCLUSION

We investigated three relatively large cohorts in order to obtain statistically robust data and to compensate for inherent methodological measurement noise. Global 1H-MRS reveals significant diffuse neuroaxonal damage in both AD and MCI patients that is markedly different from normal elderly. We demonstrate that most of the neuronal damage occurred prior to the onset of clinical AD symptoms, indicating that WBNAA may be an early, more sensitive non-invasive marker than MRI-derived global brain volume metrics. Together with the simplicity of the method and the fact that only one measurement is required, further integration of WBNAA into MRI protocols especially in large cohort epidemiological studies appears attractive.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants NS050520, EB01015 and HL111724-01. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this study from GlaxoSmithKline and the Novartis Foundation.

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris JC. Mild Cognitive Impairment Is Early-Stage Alzheimer Disease: Time to Revise Diagnostic Criteria. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:15–16. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon MJ, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm AF, Ritchie K, van Duijn CM, Visser PJ, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, Ogunniyi AO, Gureje O, Perkins A, Emsley CL, Dickens J, Evans R, Musick B, Hall KS, Hui S, Hendrie HC. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: data from the Indianapolis Study of Health and Aging. Neurol. 2001;57:1655–1662. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, Inzitari M, Scafato E, Farchi G, Inzitari D For the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging Working Group. CIND and MCI in the Italian elderly: Frequency, vascular risk factors, progression to dementia. Neurol. 2007;68:1909–1916. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263132.99055.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manly JJ, Tang M-X, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JPG, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:494–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Mild cognitive impairment: Risk of Alzheimer disease and rate of cognitive decline. Neurol. 2006;67:441–445. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228244.10416.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busse A, Bischkopf J, Riedel-Heller SG, Angermeyer MC. Mild cognitive impairment: Prevalence and incidence according to different diagnostic criteria. Brit J Psychiatry. 2003;182:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, Weissgram S, Hoenigschnabl S, Gelpi E, Krampla W, Tragl KH. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurol. 2007;68:288–291. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252358.03285.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidtke K, Hermeneit S. High rate of conversion to Alzheimer's disease in a cohort of amnestic MCI patients. Int Psychogeriat. 2008;20:96–108. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guehne U, Luck T, Busse A, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mortality in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Results of the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged (LEILA75+) Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:226–234. doi: 10.1159/000112479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gussekloo J. Impact of mild cognitive impairment on survival in very elderly people: cohort study. BMJ. 1997;315:1053–1054. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurol. 2005;64:834–841. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152982.47274.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glodzik-Sobanska L, Rusinek H, Mosconi L, Li Y, Zhan J, De Santi S, Convit A, Rich KE, Brys M, de Leon MJ. The role of quantitative structural imaging in the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2005;15:803–826. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim YS, Yoon B, Shon YM, Ahn KJ, Yang DW. Difference of the hippocampal and white matter microalterations in MCI patients according to the severity of subcortical vascular changes: Neuropsychological correlates of diffusion tensor imaging. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2008;110:552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Auchus AP. Diffusion Tensor Imaging of Normal Appearing White Matter and Its Correlation with Cognitive Functioning in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 2007;1097:259–264. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fellgiebel A, Wille P, Muller MJ, Winterer G, Scheurich A, Vucurevic G, Schmidt LG, Stoeter P. Ultrastructural Hippocampal and White Matter Alterations in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18:101–108. doi: 10.1159/000077817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Flier WM, van den Heuvel DMJ, Waverling-Rijnsburger AWE, Bollen E, Westendorp RGJ, van Buchem MA, Middelkoop HAM. Magnetization transfer imaging in normal aging, mild cognitive imapirment and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:62–67. doi: 10.1002/ana.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Namboodiri AMA. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: From neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Progress in Neurobiology. 2007;81:89–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benarroch EE. N-Acetylaspartate and N-acetylaspartylglutamate: Neurobiology and clinical significance. Neurol. 2008;70:1353–1357. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311267.63292.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danielsen EA, Ross B. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Diagnosis of Neurological Diseases. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackl N, Ising M, Schreiber YA, Atiya M, Sontag A, Auer DP. Hippocampal metabolic abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao LL, Schuff N, Kramer JH, Du AT, Capizzano AA, O'Neill J, Wolkowitz OM, Jagust WJ, Chui HC, Miller BL, Yaffe K, Weiner MW. Reduced medial temporal lobe N-acetylaspartate in cognitively impaired but nondemented patients. Neurol. 2005;64:282–289. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149638.45635.FF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kantarci K, Reynolds G, Petersen RC, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Endland SD. Proton MR Spectroscopy in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease: Comparison of 1.5 and 3 T. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2003;24:843–849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catani M, Cherubini A, Howard R, Tarducci R, Pelliccioli GP, Gobbi G, Senin U, Mecocci P. 1H-MR spectroscopy differentiates mild cognitive impairment from normal brain aging. NeuroReport. 2001;12:2315–2317. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonen O, Viswanathan AK, Catalaa I, Babb J, Udupa J, Grossman RI. Total brain N-acetylaspartate concentration in normal, age-grouped females: quantitation with non-echo proton NMR spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1998;40:684–689. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigotti DJ, Inglese M, Gonen O. Whole-Brain N-Acetylaspartate as a Surrogate Marker of Neuronal Damage in Diffuse Neurologic Disorders. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1843–1849. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falini A, Bozzali M, Magnani G, Pero G, Gambini A, Benedetti B, Mossini R, Franceschi M, Comi G, Scotti G, Filippi M. A whole brain MR spectroscopy study from patients with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2005;26:1159–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurol. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheikh JA, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent findings and development of a shorter version. New York: Hawort Press; 1986. (1986) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delis DC, Kramer J, Kaplan E, Ober B. California Verbal Learning Test - Second Edition (CVLT-II) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young JG, Brasic JR, Kaplan D, Golomb J, Ostrer H, Furman J, Biegon A. Advances in research techniques. In: Lewis M, editor. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991. p. 1201. (1991) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiber HE, Javorsky DJ, Robinson JE, Stern RA. Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure performance in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a validation study of the Boston Qualitative Scoring System. Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;13:509–520. doi: 10.1076/1385-4046(199911)13:04;1-Y;FT509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace Javanovich; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmerman P, Fimm B. Handbuch Version 1.02c. Psytest, Wuerselen, Germany: 1994. Testbatterie zur Aufmerksamkeitspruefung (TAP) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perret E. The left frontal lobe of man and the suppression of habitual responses in verbal categorical behaviour. Neuropsychologia. 1974;12:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(74)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Army. Army Individual Test battery Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General's Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaacs B, Kennie AT. The Set test as an aid to the detection of dementia in old people. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:467–470. doi: 10.1192/bjp.123.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurstone LL. Primary Mental Abilities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiat. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thalmann B, Spiegel R, Stahelin HB. Dementia screening in general practice: simplified scoring for the Clock Drawing Test. Brain Aging. 2002;2:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regard M, Strauss E, Knapp P. Children's production on verbal and non-verbal fluency tasks. Percept Mot Skills. 1982;55:839–844. doi: 10.2466/pms.1982.55.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Development and cross-validation. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24:145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mikheev A, Nevsky G, Yitta S, Grosmann R, Rusinek H. Fully automated segmentation of the brain from T1-weighted MRI using Bridge Burner algorithm. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27:1235–1241. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behavioural Neurology. 2000;12:191–200. doi: 10.1155/2000/421719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Behar KL, Rothman DL, Spencer DD, Petroff OAC. Analysis of macromolecule resonances in 1H NMR spectra of human brain. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:294–302. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baslow MH. N-acetylaspartate in the vertebrate brain: metabolism and function. Neurochemical Research. 2003;28:941–953. doi: 10.1023/a:1023250721185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benedetti B, Rigotti DJ, Liu S, Filippi M, Grossman RI, Gonen O. Reproducibility of the Whole-Brain N-Acetylaspartate Level across Institutions, MR Scanners, and Field Strengths. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2007;28:72–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markesbery WR, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Davis DG, Smith CD, Wekstein DR. Neuropathologic Substrate of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Leon MJ, Convit A, Wolf OT, Tarshish CY, De Santi S, Rusinek H, Tsui W, Kandil E, Scherer AJ, Roche A, Imossi A, Thorn E, Bobinski M, Caraos C, Lesbre P, Schlyer D, Poirier J, Reisberg B, Fowler J. Prediction of cognitive decline in normal elderly subjects with 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose/positron-emission tomography (FDG/PET) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10966–10971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191044198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, Gunn RN, Myers R, Turkheimer FE, Jones T, Banati RB. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. The Lancet. 2001;358:461–467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu W, Brickman AM, Luchsinger J, Ferrazzano P, Pichiule P, Yoshita M, Brown T, DeCarli C, Barnes CA, Mayeux R, Vannucci SJ, Small SA. The brain in the age of old: the hippocampal formation is targeted differentially by diseases of late life. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:698–706. doi: 10.1002/ana.21557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]