Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the utility of specific IgE (sIgE) concentrations for the diagnosis of immediate-type egg and cow's milk (CM) allergies in Korean children and to determine the optimal cutoff levels.

Methods

In this prospective study, children ≥12 months of age with suspected egg or CM allergy were enrolled. Food allergy was diagnosed by an open oral food challenge (OFC) or through the presence of a convincing history after ingestion of egg or CM. The cutoff levels of sIgE for egg white (EW) and CM were determined by analyzing the receiver operating characteristic curves.

Results

Out of 273 children, 52 (19.0%) were confirmed to have egg allergy. CM allergy was found in 52 (23.1%) of 225 children. The EW-sIgE concentration indicating a positive predictive value (PPV) of >90% was 28.1 kU/L in children <24 months of age and 22.9 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age. For CM-sIgE, the concentration of 31.4 kU/L in children <24 months of age and 10.1 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age indicated a >90% PPV. EW-sIgE levels of 3.45 kU/L presented a negative predictive value (NPV) of 93.6% in children <24 months of age, while 1.80 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age presented a NPV of 99.2%. The CM-sIgE levels of 0.59 kU/L in children <24 months of age and 0.94 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age showed NPVs of 100% and 96.9%.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that different diagnostic decision points (DDPs) of sIgE levels should be used for the diagnosis of egg or CM allergy in Korean children. The data also suggest that DDPs with high PPV and high NPV are useful for determining whether OFC is required in children with suspected egg or CM allergy.

Keywords: Egg allergy, food allergy, milk allergy, specific IgE

INTRODUCTION

Hen's egg white (EW) and cow's milk (CM) are the most common causes of food allergy (FA) in infants and young children.1 The estimated prevalence of egg and CM allergies ranges between 0.5 and 2.5%.2,3,4,5 Although the diagnosis of immediate-type egg and CM allergies is often based on a detailed clinical history, physical examination, and the detection of specific IgE (sIgE) to food allergens,6,7 oral food challenges (OFCs) are still considered the gold standard test for diagnosis. However, such tests are time-consuming and associated with a risk of potentially severe clinical symptoms, including anaphylaxis.3,8,9 Nevertheless, there are many cases where the use of OFC is unavoidable, because the ingestion of the suspected food often produces an unclear reaction and clinical symptoms can be vague. In addition, clinicians occasionally encounter children who have positive sIgE against a food that has never been eaten. It would be more desirable to have access to a good alternative diagnostic method to OFC.

To avoid unnecessary OFC for the diagnosis of food allergies, the use of a predictive diagnostic decision point (DDP) of sIgE levels has been proposed and is currently in wide use in clinical settings.10,11,12 The quantification of sIgE antibodies in serum was reported in some studies on an association with positive challenge tests and clinical symptoms, while others found no correlation between the sIgE levels and clinical reactivity.11,13,14,15 Moreover, the DDP value of sIgE varies according to country and race.16,17 For example, a recent study demonstrated that the sensitivity and specificity of the predictive DDP for EW-sIgE were low in Korean children,17 while a Japanese study presented much higher levels of sIgE for the diagnosis of egg or CM allergy than the previous reports.16 Further studies to evaluate the utility of sIgE levels in the diagnosis of egg and CM allergies are needed, because there may be ethnic differences between Japanese and Korean people. Moreover, the sample size of the previous Korean study was small, the age of the study population was limited to <2 years, and CM allergy was not evaluated.17

The purpose of the present study was to validate the previously established DDP for predicting the outcome of OFCs and to find optimal cutoff levels for sIgE antibodies to be utilized in the diagnosis of immediate-type egg and CM allergies in Korean children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the present study, children ≥12 months of age who visited Samsung Medical Center and Pusan National University Hospital for evaluation of suspected IgE-mediated allergy to egg or CM from August 2012 to February 2013 were enrolled. Indications for performing OFCs were as follows: children who were suspected of having FA based on a history of cutaneous, respiratory, or gastrointestinal symptoms in conjunction with the ingestion of hen's eggs or CM; or those who had atopic dermatitis (AD), even though they had never eaten those foods. In order to avoid selection bias, this study was performed prospectively and OFC was performed on all of the enrolled children, except for those who refused the test. In addition, children who had a history of anaphylaxis or repeated episodes of clinical reactions after the ingestion of a single offending food within the past year were included without receiving OFC in the statistical analysis. The diagnosis of AD was based on the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka.18 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center and Pusan National University Hospital, respectively. Written informed consent was obtained at enrollment.

Sera from all patients were obtained at the time of the initial visit. sIgE antibodies against EW and CM were measured using ImmunoCAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and considered positive when concentrations over 0.35 kU/L were detected. Open OFCs were performed under the supervision of allergists, according to the Korean guidelines.19,20 Briefly, children were challenged with boiled egg or fresh pasteurized CM at a total dose of 0.15-0.3 g protein per kg of body weight. The total challenging dose did not exceed 3 g of protein. Over a period of 90 minutes, the patients received EW or CM in increments of 1%, 4%, 10%, 20%, and 25% of the total amounts every 15 minutes. The tests were regarded as positive when the attending pediatric allergist confirmed 1 or more of the following objective symptoms within 2 hours of the last challenge dose: urticaria, angioedema, cough, rhinorrhea, wheezing, stridor, breathing difficulty, vomiting, and low blood pressure.19,21,22

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For each food, the median level of sIgE (kU/L) with interquartile range (IQR) was calculated. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the median levels of sIgE to food allergens between children with and without allergies. Levels of sIgE antibodies above 100 kU/L were assigned a value of 101 kU/L for analysis. Performance characteristics, such as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were analyzed based on previously established DDPs as follows: EW-sIgE levels of 2 kU/L in children <24 months of age; EW-sIgE levels of 7 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age; CM-sIgE levels of 5 kU/L in those <24 months of age; and CM-sIgE levels of 15 kU/L in those ≥24 months of age.10,11,12 DDPs for predicting the outcomes of OFCs were also calculated. The cutoff levels of sIgE against EW and CM were determined by analyzing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Because the use of separate Mann-Whitney U tests leads to an inflated type 1 error, Bonferroni's correction was applied to the subgroup analysis of patients according to their age by adjusting the P value. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

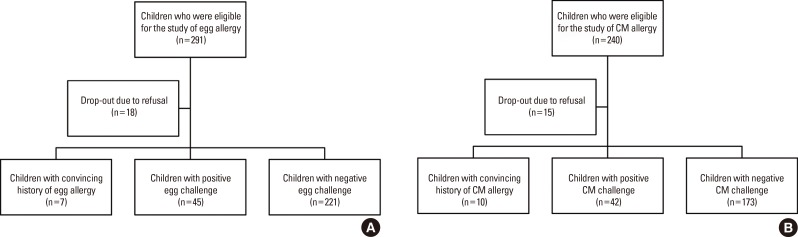

In the present study, 273 children (161 boys and 112 girls) with suspected egg allergy and 225 children (137 boys and 88 girls) with suspected CM allergy were analyzed (Fig. 1). There were 7 and 10 children with a convincing history of egg and CM allergy, respectively. The mean ages of the study subjects for the EW and CM challenges were 40.3 months (median 30, range 12-199) and 41.0 months (median 28, range 12-204), respectively. Out of the 273 children with suspected egg allergy, 99 (36.3%) were <24 months, 60 (21.9%) were from 24 to 35 months, 39 (14.3%) from 36 to 47 months, and 75 (27.5%) were ≥48 months of age. Among the 225 children with suspected CM allergy, 87 (38.7%) were <24 months, 47 (20.9%) were from 24 to 35 months, 28 (12.4%) from 36 to 47 months, and 63 (28.0%) were ≥48 months of age. Concomitant allergic diseases were found in all participants, with 81.3% having AD, 8.5% suffering from asthma, and 11.2% exhibiting allergic rhinitis. As a result of OFC or having a convincing history, 52 out of 273 (19.0%) and 52 out of 225 (23.1%) participants were confirmed to be allergic to egg and CM, respectively (Table 1). Twenty-six of the 52 children (50.0%) with egg allergy were <24 months of age, while 26 (50.0%) were ≥24 months of age. Twenty-five of the 52 children (48.1%) with CM allergy were <24 months of age, while 27 (51.9%) were ≥24 months of age.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study population.

Table 1. Demographic data of children with egg and cow's milk allergies.

| Egg allergy | Cow's milk allergy | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number | 52 | 52 |

| Convincing history (n) | 7 | 10 |

| Positive oral challenge test (n) | 45 | 42 |

| Sex (boys vs girls, n) | 35:17 | 30:22 |

| Median Age (months) | 24 | 24 |

| Median specific IgE (kU/L) | 16.7 | 8.19 |

| Clinical symptoms (%) | ||

| Cutaneous | 88.5 | 96.2 |

| Urticaria | 85.7 | 95.8 |

| Angioedema | 17.2 | 21.0 |

| Eczema | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Respiratory | 21.2 | 9.6 |

| Cough / rhinorrhea | 20.9 | 9.6 |

| Wheezing / stridor | 8.5 | 4.5 |

| Breathing difficulty | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 9.6 | 3.8 |

| Vomiting / diarrhea | 6.5 | 3.5 |

| Abdominal pain | 5.3 | 0.8 |

| Anaphylaxis | 23.0 | 9.6 |

| Others | 0.2 | 0.2 |

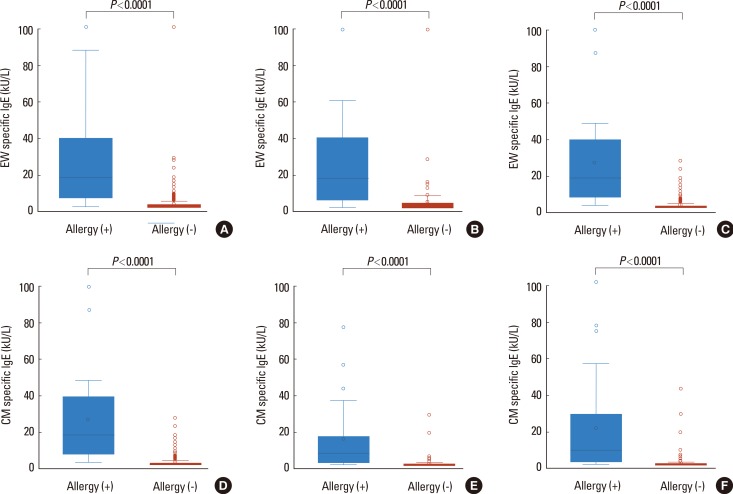

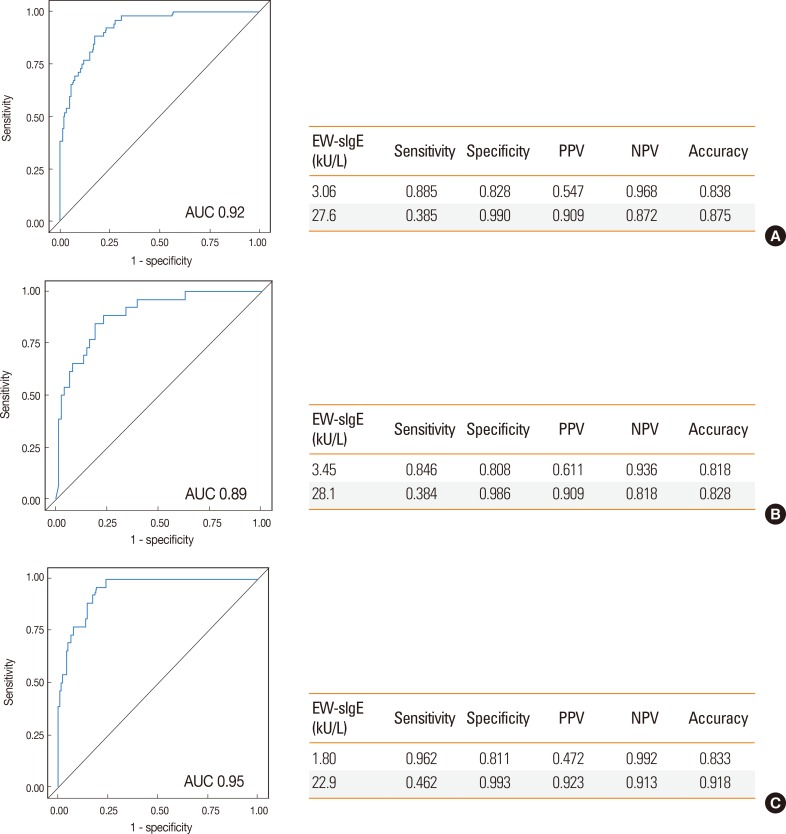

Among those with egg allergy, the most common reactions were cutaneous manifestations (88.5%), followed by respiratory symptoms (21.2%), gastrointestinal symptoms (9.6%), and cardiovascular symptoms (0.2%). Overall, 23% of the reactions involved 2 or more systems. The levels of EW-sIgE were significantly higher in the allergy group than in the nonallergy group (median 16.7 vs 0.38 kU/L, P<0.0001, Fig. 2). The difference in EW-sIgE levels between the egg allergy and nonallergy groups was also found in subgroup analyses of the children <24 months (median 16.8 vs 0.53 kU/L, P<0.0001) and ≥24 months of age (median 16.7 vs 0.31 kU/L, P<0.0001) (Fig. 2). When the previously established DDP of EW-sIgE concentrations for egg allergy was applied in our study population,11 the values for sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 88.5%, 68.5%, 50.0%, and 94.3% in children <24 months of age and 73.1%, 91.2%, 59.3%, and 95.1% in those ≥24 months of age, respectively (Table 2). The relationship between sensitivity and specificity was further explored by analysis of the ROC curves, yielding acceptable areas under the curve of 0.92. The EW-sIgE concentration indicating a 90% risk of reaction was calculated to be 27.6 kU/L (Fig. 3). Poststratification into different age groups showed slightly different diagnostic values for the >90% risk of positive reaction for OFC at 28.1 kU/L for children <2 years of age and 22.9 kU/L for those ≥2 years of age. The EW-sIgE levels of 1.80 kU/L in children ≥24 months of age had an NPV of 99.2%, a PPV of 47.2%, a sensitivity of 96.2%, and a specificity of 81.1%. In children <24 months of age, EW-sIgE levels of 3.45 kU/L presented an NPV of 93.6% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Comparison of specific IgE levels between positive and negative oral food challenge (OFC) groups. (A) All children for hen's egg challenge; (B) those <24 months of age for hen's egg challenge; (C) those ≥24 months of age for hens' egg challenge; (D) all children for cow's milk challenge; (E) those <24 months of age for cow's milk challenge; (F) those ≥24 months of age for cow's milk challenge. EW, egg white; CM, cow's milk. Each box plot indicates an interquartile range (IQR) with median, upper, and lower whiskers; upper and lower boundaries (3rd quartile/1st quartile ±1.5 IQR). The blue and red boxes represent patients showing positive and negative OFC results.

Table 2. Performance characteristics in the present study population based on the widely used diagnostic decision points.

| Allergen | sIgE (kU/L) | Allergy (+) | Allergy (-) | sensitivity | specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg white (< 24 months old) |

≥2 | 23 | 23 | 88.50% | 68.50% | 50.00% | 94.30% |

| <2 | 3 | 50 | |||||

| Egg white (≥ 24 months old) |

≥7 | 19 | 13 | 73.10% | 91.20% | 59.30% | 95.10% |

| <7 | 7 | 135 | |||||

| Cow's milk (<24 months old) |

≥5 | 15 | 3 | 60.00% | 95.10% | 83.30% | 85.50% |

| <5 | 10 | 59 | |||||

| Cow's milk (≥ 24 months old) |

≥15 | 11 | 1 | 40.70% | 99.90% | 91.70% | 87.30% |

| <15 | 16 | 110 |

sIgE, specific immunoglobulin E; PPV, positive predictive values; NPV, negative predictive values.

Fig. 3. Performance characteristics of optimal cutoff values of egg white specific IgE established by ROC analysis. (A) All children; (B) those <24 months of age; (C) those ≥24 months of age.

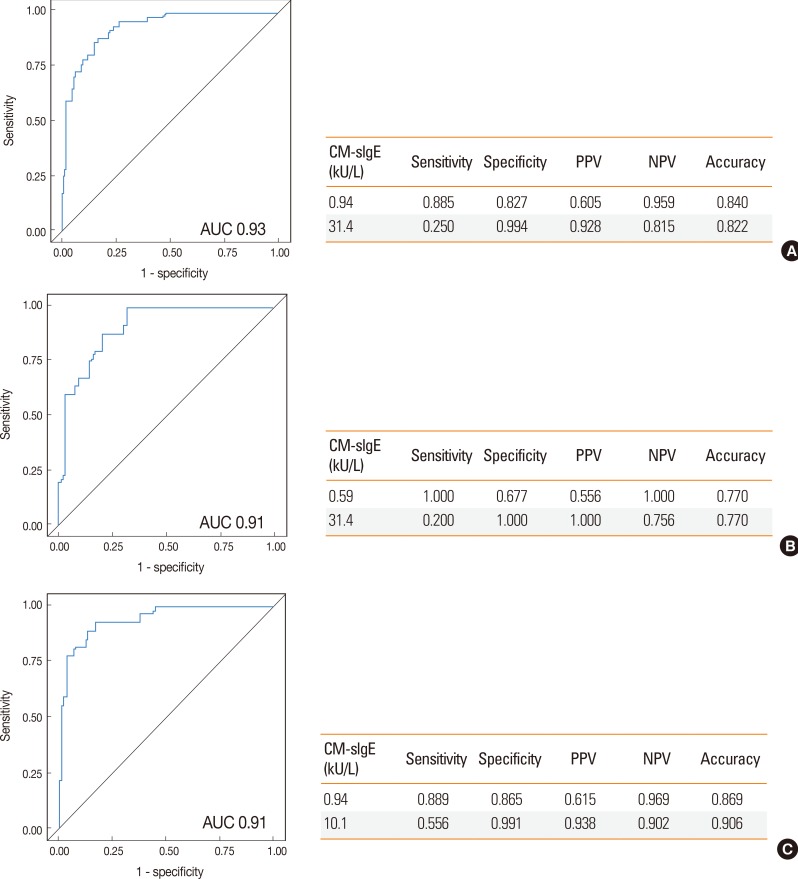

In the present study, children with CM allergy presented skin or mucosal symptoms in 96.2% of cases, with respiratory symptoms in 9.6%, gastrointestinal symptoms in 3.8%, and cardiovascular symptoms in 0.2%. Anaphylaxis was found in 9.6% of the patients. A significant difference was also found in the level of sIgE antibodies against CM between the allergy and non-allergy groups (median 8.19 vs 0.19 kU/L, P<0.0001, Fig. 2). This was also observed in children <24 months (median 6.6 vs 0.26 kU/L, P<0.0001) and ≥24 months of age (median 10.3 vs 0.16 kU/L, P<0.0001) (Fig. 2). The previously established DDP for CM allergy11 showed the sensitivity of 60.0%, specificity of 95.1%, PPV of 83.3%, and NPV of 85.5% in children <24 months of age among our study population, and the sensitivity of 40.7%, specificity of 99.9%, PPV of 91.7%, and NPV of 87.3% in children ≥24 months of age (Table 2). The ROC curves of sensitivity and specificity showed acceptable areas under the curve of 0.93. The CM-sIgE concentration indicating a PPV of 92.8% was calculated to be 31.4 kU/L (Fig. 4). Poststratification into different age groups showed different diagnostic values in >90% PPV for positive OFC at 31.4 kU/L in children <2 years old and 10.1 kU/L for those ≥2 years of age. CM-sIgE levels of 0.94 kU/L in children ≥24 months of age had an NPV of 96.9%, a PPV of 61.5%, a sensitivity of 88.9%, and a specificity of 86.5%. In children <24 months of age, the CM-sIgE levels of 0.59 kU/L presented an NPV of 100% (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Performance characteristics of optimal cutoff values of cow's milk specific IgE established by ROC analysis. (A) All children; (B) those <24 months of age; (C) those ≥24 months of age.

DISCUSSION

Serum sIgE levels were used to predict the outcomes of OFCs in patients suspected of having egg or CM allergy.10,11 The cutoff values were previously reported to be 7 kU/L in children ≥2 years of age and 2 kU/L in those <2 years of age for egg allergy, with the cutoff values of 15 kU/L in those ≥2 years of age and 5 kU/L in those <2 years of age for CM allergy.10,11,12 In other words, approximately 95% of the patients are predicted to have clinical reactions when the sIgE concentrations exceed those diagnostic levels. These DDPs have also been used in clinical settings in Korea. However, it was found that the PPVs were much lower when these DDPs for EW- and CM-sIgE antibodies were applied in our study population. This suggests that the DDP from the US population is not acceptable for the diagnosis of egg or cow's milk allergy in Korean children. In the present study, the EW-sIgE concentration indicating >90% risk of reaction was found to be 28.1 kU/L in children <2 years of age and 22.9 kU/L in those ≥2 years of age. The CM-sIgE level of 31.4 kU/L presented a 100% risk of clinical symptoms in children <2 years of age, while 10.1 kU/L presented a 93.7% risk of clinical symptoms in those ≥2 years of age. Consequently, it is more practical to use higher DDPs of EW- and CM-sIgE antibodies in Korean children for the diagnosis of egg and CM allergies in order to avoid unnecessary restriction of diet.

Our results are consistent with those of earlier studies, in which the sIgE levels were associated with positive challenge tests and clinical reaction.6,10,14 Higher concentrations of food-sIgE levels correlate with an increasing likelihood of clinical symptoms, for which a particular cutoff level associated with a high possibility of reaction is considered the DDP.13,23,24,25 Although these diagnostic levels are helpful to physicians in deciding whether an OFC is necessary, different DDPs were reported in each of the previous studies. For example, a Danish study reported 1.5 kU/L as the 95% DDP for egg,26 and a Spanish study presented 2.5 kU/L as the 90% DDP for CM.12 A German study demonstrated that the diagnostic values for 95% probability of allergy were 10 kU/L for egg and 46 kU/L for CM.6 In a Japanese study, the 95% DDPs for EW and CM were reported as 25.5 and 50.9 kU/L, respectively.16 Our results also showed that the predictive values of sIgE were different in Korean children. This may be explained by the differences in the study population examined herein, such as age, race, concomitant atopic disease, and the study eligibility criteria. Our data support the assertion that the DDP needs to be determined in each region to make use of the food-sIgE concentration as a tool for the diagnosis of FA instead of OFC.

Most children with egg or CM allergy come to tolerate these foods as they grow older.27 OFC is used to confirm not only the presence of FA, but also the development of tolerance. In order to decide the timing for reintroduction of egg or CM, the cutoff level of >95% NPV could provide a guide for clinicians to select patients who are likely to pass food challenges and to avoid unnecessary office-based OFC, although OFC is still required for final diagnosis. In the present study, an EW-sIgE level of 1.80 kU/L in children ≥24 months of age showed an NPV of 99.2% with a sensitivity of 96.2% and a specificity of 81.1%. In children ≥24 months of age, the NPV, sensitivity and specificity of the CM-sIgE level of 0.94 kU/L was 96.9%, 88.9% and 86.5%, respectively. This means that there is >95% probability that children ≥24 months of age with EW-sIgE <1.8 kU/L and CM-sIgE <0.94 kU/L will pass the OFC test. Taken together, in the present study, we obtained the DDPs of sIgE concentrations with >90% PPV and DDPs with >95% NPV for egg and CM allergies. These results suggest that both DDPs could be used to determine the presence or absence of egg and CM allergies in Korean children instead of OFC, while OFC is required to confirm the diagnosis in children with sIgE levels between the 2 DDPs.

Our study has some limitations stemming from the method of the OFC and the age of the children. We performed open OFCs, not a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). However, open OFCs are regarded as a practical alternative method to diagnose FA in clinical settings, because DBPCFC is time-consuming and labor-intensive.15 In addition, we could not obtain DDP values for the diagnosis of EW or CM allergy in infants <12 months of age, because most Korean parents refuse to perform challenge tests on their babies due to the risk of anaphylaxis. Moreover, parents do not feel the necessity of OFC in this age group, because nutritional support from EW or CM proteins can easily be replaced by extensively hydrolyzed formula, breast milk from mothers who restrict the ingestion of suspected foods, and soy formula. Finally, the participants in this study do not represent the entire population of Korean children, although the size of the study population was not small. Nevertheless, the present study has strengths in its prospective design and the inclusion of sufficient study populations. Selection bias was particularly minimized by performing OFC regardless of the levels of sIgE in most of the children who met the inclusion criteria among those who visited during the study period.

In conclusion, the DDP of sIgE levels in Korean children with egg or CM allergy are different from those in the US population. This suggests that the diagnostic values of specific IgE levels in food allergy should be evaluated in each region. Our data also suggest that use of both DDPs for high PPV and high NPV are useful to determine whether OFC is required in children with suspected egg or CM allergy.

Footnotes

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lee AJ, Thalayasingam M, Lee BW. Food allergy in Asia: how does it compare? Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3:3–14. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berni Canani R, Ruotolo S, Discepolo V, Troncone R. The diagnosis of food allergy in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:584–589. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32830c6f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramesh S. Food allergy overview in children. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008;34:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J, Chang E, Han Y, Ahn K, Lee SI. The incidence and risk factors of immediate type food allergy during the first year of life in Korean infants: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:715–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park M, Kim D, Ahn K, Kim J, Han Y. Prevalence of immediate-type food allergy in early childhood in Seoul. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6:131–136. doi: 10.4168/aair.2014.6.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celik-Bilgili S, Mehl A, Verstege A, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer K, et al. The predictive value of specific immunoglobulin E levels in serum for the outcome of oral food challenges. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:268–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta RS, Dyer AA, Jain N, Greenhawt MJ. Childhood food allergies: current diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:512–526. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson HA. Food allergy--accurately identifying clinical reactivity. Allergy. 2005;60(Suppl 79):19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:444–451. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:805–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyano Martínez T, García-Ara C, Díaz-Pena JM, Muñoz FM, García Sánchez G, Esteban MM. Validity of specific IgE antibodies in children with egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1464–1469. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S116–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Niggemann B, Grabenhenrich L, Wahn U, Beyer K. Outcome of oral food challenges in children in relation to symptom-eliciting allergen dose and allergen-specific IgE. Allergy. 2012;67:951–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longo G, Berti I, Burks AW, Krauss B, Barbi E. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet. 2013;382:1656–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komata T, Söderström L, Borres MP, Tachimoto H, Ebisawa M. The predictive relationship of food-specific serum IgE concentrations to challenge outcomes for egg and milk varies by patient age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1272–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min TK, Jeon YH, Yang HJ, Pyun BY. The clinical usefulness of IgE antibodies against egg white and its components in Korean children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2013;5:138–142. doi: 10.4168/aair.2013.5.3.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;60:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song TW, Kim KW, Kim WK, Kim JH, Kim HH, Park YM, et al. Guidelines for the oral food challenges in children. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2012;22:4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yum HY, Yang HJ, Kim KW, Song TW, Kim WK, Kim JH, et al. Oral food challenges in children. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:6–10. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Assa'ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS, et al. Work Group report: oral food challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:S365–S383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bindslev-Jensen C, Ballmer-Weber BK, Bengtsson U, Blanco C, Ebner C, Hourihane J, et al. Standardization of food challenges in patients with immediate reactions to foods--position paper from the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2004;59:690–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cianferoni A, Spergel JM. Food allergy: review, classification and diagnosis. Allergol Int. 2009;58:457–466. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.09-RAI-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roehr CC, Reibel S, Ziegert M, Sommerfeld C, Wahn U, Niggemann B. Atopy patch tests, together with determination of specific IgE levels, reduce the need for oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:548–553. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:891–896. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osterballe M, Bindslev-Jensen C. Threshold levels in food challenge and specific IgE in patients with egg allergy: is there a relationship? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:196–201. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burks AW, Jones SM, Boyce JA, Sicherer SH, Wood RA, Assa'ad A, et al. NIAID-sponsored 2010 guidelines for managing food allergy: applications in the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2011;128:955–965. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]