Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat foods has been implicated in numerous outbreaks of food-borne listeriosis. However, the health hazards posed by L. monocytogenes detected in foods may vary, and speculations exist that strains actually implicated in illness may constitute only a fraction of those that contaminate foods. In this study, examination of 34 serogroup 4 (putative or confirmed serotype 4b) isolates of L. monocytogenes obtained from various foods and food-processing environments, without known implication in illness, revealed that many of these strains had methylation of cytosines at GATC sites in the genome, rendering their DNA resistant to digestion by the restriction endonuclease Sau3AI. These strains also harbored a gene cassette with putative restriction-modification system genes as well as other, genomically unlinked genetic markers characteristic of the major epidemic-associated lineage of L. monocytogenes (epidemic clone I), implicated in numerous outbreaks in Europe and North America. This may reflect a relatively high fitness of strains with these genetic markers in foods and food-related environments relative to other serotype 4b strains and may partially account for the repeated involvement of such strains in human food-borne listeriosis.

Food contamination by Listeria monocytogenes has been implicated in numerous outbreaks and sporadic cases of human illness. Most commonly implicated in listeriosis are highly processed, ready-to-eat (RTE) foods that are kept refrigerated for various periods of time. At risk for listeriosis are people in the extremes of age, pregnant women and their fetuses, cancer patients, and others experiencing immunosuppression (13, 24, 35, 38).

Listeriosis can have severe symptoms (septicemia, meningitis, and stillbirths) and a high mortality rate (20 to 30%). Hence, regulations exist in numerous nations concerning the density (e.g., <1 CFU/25 g) of cells of the etiologic agent permissible in RTE foods. Such regulations are based on the hypothesis that any L. monocytogenes strain that can be detected in RTE foods has the potential to pose serious hazards to human health.

The potential hazard posed by listerial contamination of RTE foods can be influenced by the number of cells at the point of consumption, which would depend on conditions of storage, type of food matrix and its impact on growth, presence of competing microflora and antimicrobial agents, etc. In addition, the strain type of L. monocytogenes involved may be of importance. It is likely, based on studies with other bacterial pathogens, that some strains and strain clusters (clonal groups) within the species might be more pathogenic than others. Speculations have been formulated that only a fraction of the strains of L. monocytogenes found in foods may be capable of causing human illness (20).

There is indeed evidence that the repertoire of strains capable of contaminating food is wider than that of strains recovered from patients with listeriosis. Specifically, even though foods may be contaminated by strains of various serotypes, more than 95% of human listeriosis cases involve just three serotypes, 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b. In addition, most outbreaks have involved a small number of genetically related strains of serotype 4b (6, 24, 31, 35). Furthermore, strains of serotype 1/2c are relatively rare among human clinical isolates but are frequently isolated from foods (23).

In spite of the incongruities in the observed distribution of clinical and food-derived strains, significant differences in virulence characteristics between human clinical and food-derived strains have not been consistently detected (5, 9, 11, 28, 32). However, recent findings suggest that food-derived and clinical isolates tend to differ, at the population level, in parameters that may be of relevance during infection. These include the readiness to resume growth at 37°C following starvation at 4°C (1) and the apparent molecular weight of the virulence determinant ActA (21). In addition, the protein profiles of three food-derived isolates of serotype 1/2a were found to have significant differences from those of the serotype 1/2a strain EGDe, the genome of which has been sequenced, suggesting differences either in gene content or in expression (34). Overall, however, limited information currently exists concerning the genomic diversity and virulence of L. monocytogenes strains isolated from routine surveys of food with no known implication in illness. It is expected that such studies will be greatly facilitated by the recent availability of the genome sequence of L. monocytogenes, including the sequences of strain EGDe of serotype 1/2a (15) and strain F2365 of serotype 4b (www.tigr.org). The latter strain has been implicated in a food-borne outbreak of listeriosis (California outbreak) involving contaminated Mexican-style cheese (38).

Serotype 4b strains closely related to F2365 have been found responsible for a number of temporally and geographically distinct outbreaks in North America and Europe and represent a “clone” in the epidemiological sense (29), referred to as epidemic clone I (23, 24). Epidemic clone I strains share certain special characteristics: their genomic DNA is resistant to digestion by the enzyme Sau3AI, suggesting methylation of cytosines at GATC sites (18, 44); they harbor restriction fragment length polymorphisms that differentiate them from other serotype 4b strains (41, 43); and they harbor a number of unique genomic fragments and gene clusters commonly absent from other serotype 4b strains (18; S. Yildirim and S. Kathariou, unpublished results).

In this study, we characterized several strains of L. monocytogenes of serotype 4b obtained from routine surveys of foods and food-processing environments. Focusing on genotypes at selected loci, it was found that a substantial fraction of these strains had Sau3AI-resistant genomic DNA and harbored additional, genomically unlinked genetic markers specific to epidemic clone I.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The serogroup 4 L. monocytogenes strains of food and environmental origin that were used in this study are listed in Table 1. With the exception of strain NCSK02-16 (provided to us by K. Boor, Cornell University) and NCSK02-3, (provided by L. Wolf, North Carolina Department of Health Epidemiology Laboratory), all other strains were from the strain collections of the Food and Drug Administration. The strains had been isolated during routine surveys of various foods and food-processing environments in the time period between 1985 and 2003, as indicated in Table 1, and were chosen for inclusion in this study based strictly on their serotype (determined to be serogroup 4 or, for certain strains, serotype 4b). In addition, we included as reference strains three known epidemic clone I strains (all of serotype 4b) that were isolated from foods implicated in outbreaks. These included NCLG-5 (cheese isolate, Swiss outbreak of 1983 to 1987), NCLG-8 (Mexican-style cheese isolate, California outbreak of 1985), and NCLG-11 (coleslaw isolate, Nova Scotia outbreak of 1981). These reference strains were provided to us by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth and preservation of the bacteria were as previously described (26).

TABLE 1.

Food and environmental strains of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b used in this study

| Strain (serotype) | Yr isolated | Origin | Digestion by:

|

Reactivity with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sau3AI | MboI | gltA | 85M, 85S, and 85R | 133 | 17B | |||

| Sau3AI-resistant strains | ||||||||

| NCSK03-61 (4)a | 2003 | Cooked Dungeness crab | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK01-13 (4)a | 2001 | Frozen breaded shrimp | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK01-32 (4)a | 2001 | Guacamole | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK01-45 (4)a | 2001 | Frozen avocado pulp | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK01-46 (4)a | 2001 | Frozen avocado pulp | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK01-58 (4)a | 2001 | Virginia ham | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK99-1 (4b) | 1999 | Processed avocadob | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK99-4 (4b) | 1999 | Processed avocadob | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK99-6 (4b) | 1999 | Processed avocadob | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK97-1 (4)a | 1997 | Hummus | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK92-3 (4)a | 1992 | Beef frankfurters | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK88-4 (4b) | 1988 | Crabmeat, frozen | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK88-5 (4b) | 1988 | Shrimp, cooked | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK88-12 (4b) | 1988 | Lobster, frozen | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK88-16 (4)a | 1988 | Red snapper | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK87-11 (4b) | 1987 | Soft cheese | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK86-1 (4b) | 1986 | Ice cream bar | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK86-9 (4b) | 1986 | Dairy, environment | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK86-13 (4b) | 1986 | Ice cream bars | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| NCSK03-77 (4)a | NKc | Food | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sau3AI-sensitive strains | ||||||||

| NCSK98-31 (4b) | 1998 | Hot dog | + | + | + | NDd | ND | − |

| NCSK87-3 (4)a | 1987 | Ice cream | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK88-2 (4)a | 1988 | Cheese | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK88-6 (4b) | 1988 | Shrimp plant environment | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK88-10 (4b) | 1988 | Blue cheese | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK88-17 (4b) | 1988 | Scallops | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK88-18 (4b) | 1988 | Crabmeat, cooked | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK87-8 (4)a | 1987 | Milk, pasteurized | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK87-16 (4b) | 1987 | Raw shrimp | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK86-7 (4)a | 1986 | Soft cheese | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK86-14 (4)a | 1986 | Dairy plant, environment | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK85-15 (4)a | 1985 | Ice cream plant | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK02-16 (4)a | NK | Food | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| NCSK02-3 (4b) | NK | Food | + | + | + | ND | − | − |

Strains are positive with gltA and serotype 4b-specific MAbs, hence likely to be of serotype 4b, 4d, or 4e.

Products yielding each of these strains were from different producers.

NK, exact year of isolation not known.

ND, not determined.

Serotype designations were confirmed by reactivity with monoclonal antibodies highly specific for serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e (25) and with Southern blotting employing probes derived from the gene gltA, found in all screened serotype 4b, 4d, and 4e strains but not in other serotypes of L. monocytogenes (26).

Isolation of genomic DNA and restriction enzyme analysis.

The DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) was used to extract and isolate DNA from Listeria cultures grown for 24 h according to the method supplied by the manufacturer. Determination of DNA resistance or sensitivity to Sau3AI or MboI digestion was performed as previously described (44). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) or from Promega (Madison, Wis.) and were used according to the manufacturers' instructions.

PCR and Southern blots.

Primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. Some primers were designed based on preliminary sequence data of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, which were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research through the website at http://www.tigr.org. Primers were designed using the software Primer3 (http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/other/primer3.html) and were purchased from Bio-synthesis, Inc. (Lewisville, Tex.) or from QIAGEN. PCR employed Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Fisher). The reaction mixtures were subjected to a hot start (95°C for 5 min) prior to 30 cycles of amplification (95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 20 min) in a Progene thermocycler. Amplified products were separated by electrophoresis through a 1.0% (wt/vol) agarose gel with 1× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences used in this study

| Gene or fragment | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 85Ma | AATATATTTTCAATGTTTGATGGT | GCTAATTCAATCCCTATTCT |

| 85Rb | CTGATGATGCTGGAAAAGCA | TGATGTCCTTCCACATAAGGC |

| 85Sb | ACCACGGGCATACTCGTTTA | GGGCCTCAAATGAAGAACAT |

| gltAc | TCATCGTATCGCTTCTGTG | GTGCCATTACTACAGGTGCA |

| gltBc | TTCAAATAAGCCGTTCCAAA | AAAGGCAGAGATTACGCA |

| gtcAd | TGGGTTACTACAAGAAGAG | AGTACTGATGCGATAAAAGCA |

| 133e | TCAACATCAGCGTAATTATGAG | AGTTCTTGTAGGTGTTTTACAG |

| 17Bf | TCCCTAACGTATTTTTTCAAATC | TGAGTTAGGTAATTTTATAAGTTG |

GenBank accession no. AJ410373.

Constructed on the basis of preliminary sequence data for L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, which were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research through the website at http://www.tigr.org.

GenBank accession no. AFO33015.

GenBank accession no. AFO72894.

GenBank accession no. J410381.

GenBank accession no. AJ410357.

DNA probes for Southern blotting were obtained by using the PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of the serotype 4b strain F2381, implicated in the same outbreak as strain F2365, employed in the serotype 4b genome sequencing (www.tigr.org). The PCR products were excised from the gel (0.8% agarose gel with 1× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer) and purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN). DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin (Genius kit; Roche) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Southern blotting was performed as described previously (26).

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

For DNA and protein database searches and analyses, we used FASTA (University of Wisconsin GCG package; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.), BLAST algorithms (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), and ARTEMIS software (36; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Artemis). Preliminary sequence data for L. monocytogenes serotype 4b were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research through the website at http://www.tigr.org. GAMOLA (Global Annotation of Multiplexed On-site Blasted DNA sequences) (www.cals.ncsu.edu:8050/food_science/KlaenhammerLab//GAMOLA) was used to automatically predict coding open reading frames and annotate the draft sequence in the genomic region encompassing DNA fragment 85 (18). GAMOLA relies on the available software Glimmer2 (10), the NCBI tool kit (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.), and HMMER2.2g (12) and combines the results into functionally annotated DNA sequences in GenBank format. The annotated sequences of the serotype 4b genome in the region encompassing DNA fragment 85 (18) were visualized by using ARTEMIS (36). Restriction map analysis of specific genomic regions employed the program Webcutter, version 2.0 (Max Heiman, Yale University, 1997), (http://www.firstmarket.com/cutter/cut2.html), and the coordinates were verified with ARTEMIS.

RESULTS

Unexpectedly high prevalence of strains with Sau3AI-resistant DNA among serotype 4b strains of food origin.

Genomic DNAs of all strains listed in Table 1 were screened for sensitivity to digestion by the GATC-recognizing enzymes MboI and Sau3AI. Methylation of the cytosine at GATC sites inhibits cleavage by Sau3AI but has no effect on digestion by MboI, which, in contrast, is inhibited by methylation of the adenine at the same site (27). All DNAs could be readily digested by MboI. In contrast, digestion with Sau3AI revealed that a substantial portion of the isolates had DNA that resisted digestion (Table 1). Since the DNA of these isolates could be cut by MboI (Table 1), it can be concluded that the reason for the resistance to digestion by Sau3AI was not the quality of the DNA but instead the methylation of the cytosines at the GATC sites in the genome of these isolates. All of these Sau3AI-resistant isolates appeared to be typical serotype 4b strains on the basis of their reactivities with monoclonal antibodies c74.22 and c74.33, specific for serotype 4b, and the rare but closely related serotypes 4d and 4e (25). These strains were also positive by PCR and Southern blotting for the serotype-specific gene gtcA, which is specific to serogroup 4 (33), and for the serotype 4b-, 4d-, and 4e-specific genes gltA and gltB, involved in teichoic acid glycosylation (26). The three reference epidemic clone I strains that we employed (NCLG-5, NCLG-8, and NCLG-11, from food implicated in the Swiss, California, and Nova Scotia outbreaks of listeriosis, respectively) had DNA that could be readily digested by MboI but resisted digestion by Sau3AI, as previously described (44; data not shown).

Serotype 4b (or serogroup 4) strains found to have methylated (Sau3AI-resistant) DNA included isolates from various commodities and food-processing environments, including processed avocado, dairy products such as ice cream bars and soft cheese, and the dairy plant environment (4 of 11 screened strains); seafood such as frozen lobster, frozen crabmeat, and cooked shrimp (6 of the 10 screened strains); and other food products (beef franks and hummus) (Table 1).

Identification of an epidemic clone I-specific restriction-modification system (genes 85M, 85R, and 85S) in the genome of food-derived strains with Sau3AI-resistant DNA.

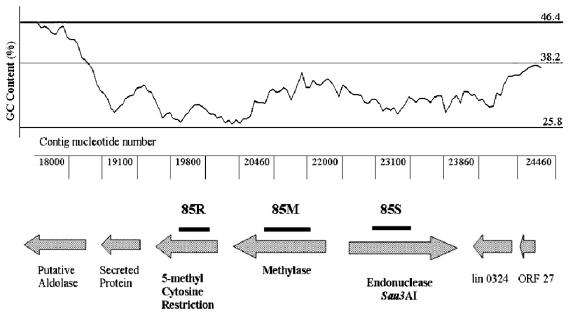

In 2001, Herd and Kocks showed that DNA fragment 85 was specific to epidemic clone I and was internal to a gene with putative involvement in cytosine methylation at GATC sites (18). In the current study, the GAMOLA-based annotation of the serotype 4b genomic region encompassing fragment 85 suggested that this fragment was localized in contig 760 and was internal to a gene (designated 85M) with significant homology to genes encoding DNA methyltransferases. The deduced polypeptide product of 85M (471 amino acids) had 56% identity (over 434 amino acids) with GATC-specific methyltransferases of Streptococcus thermophilus (7) and Lactococcus lactis (42), as well as lower degrees of similarity with several other methyltransferases produced by other bacteria. The putative methyltransferase gene 85M was immediately upstream of, and transcribed in the same orientation as, a putative restriction endonuclease gene (designated 85R). Another gene with putative Sau3AI activity, designated 85S, was found adjacent to 85M and was transcribed in a divergent orientation (Fig. 1). The deduced polypeptide product of 85S (555 amino acids) had 34% identity (over its entire length) with the Sau3AI restriction endonuclease of Staphylococcus aureus (39) and 25% identity (over 495 amino acids) with the restriction component in the L. lactis LlaKR2I restriction-modification system (42) mentioned above. The deduced product of 85R (292 amino acids) had only a relatively small domain (ca. 90 amino acids) with similarity to restriction endonucleases produced by several other bacteria (identity values of 33 to 38%).

FIG. 1.

Restriction-modification system genes in the L. monocytogenes serotype 4b genome. Annotation and visualization of the region were done using GAMOLA and ARTEMIS as described in Materials and Methods. Putative open reading frames designated 5-methyl cytosine restriction, methylase, and putative Sau3AI correspond to 85R, 85M, and 85S, respectively, described in the text. Black bars indicate probes used for Southern blot-based detection of 85R, 85M, and 85S. Arrows indicate direction of transcription. The deduced G+C contents of the genes are shown at the top.

The results from this analysis suggest that the genomes of epidemic clone I strains harbor a gene cassette (85M-85R-85S) with GATC-specific restriction-modification functions. Modification (methylation) genes are commonly in the immediate vicinity of genes encoding restriction enzymes with the same site specificity (cognate restriction endonucleases) (3). The G+C contents of the putative restriction-modification system genes 85M, 85R, and 85S were 33, 28, and 31%, respectively, noticeably lower than is typical for the L. monocytogenes genome (38%). The lower overall G+C content of the 85M-85R-85S genomic region is also readily detected in the ARTEMIS-based visualization of the region shown in Fig. 1.

All strains with Sau3AI-resistant DNA harbored the 85M sequences in their genomic DNA, yielding a single hybridizing fragment of ca. 5.8 kb in Southern blots of EcoRI-digested DNA (Fig. 2A). The size of this fragment was in agreement with that predicted on the basis of the genome sequence of strain F2365, which also revealed one EcoRI site in 85M, located near the 3′ end of the coding sequence. The hybridizing band seemed to be of the same size in all isolates, suggesting lack of polymorphism in the EcoRI sites flanking the fragment. None of the serogroup 4 or serotype 4b strains with DNA that could be cut with Sau3AI yielded a signal with the 85M probe (Fig. 2A), even under conditions of low stringency (data not shown). These data suggest that only isolates with Sau3AI-resistant DNA harbored sequences that hybridized with the 85M sequences and that these sequences were conserved among isolates with Sau3AI-resistant DNA.

FIG. 2.

Southern blotting with a digoxigenin-labeled probe internal to the putative methylase 85M (A) and with epidemic clone I-specific probe 17B (B). Probe construction and Southern blot conditions were as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1 to 12 and lane 20, Sau3AI-resistant strains NCSK99-6, NCSK01-45, NCSK86-1, NCSK88-4, NCSK87-11, NCSK88-12, NCSK97-1, NCSK92-3, NCSK01-32, NCLG-B5 (cheese, Swiss outbreak), NCLG-B8 (Mexican-style cheese, California outbreak), NCLG-B11 (coleslaw, Nova Scotia outbreak), and F2381 (control epidemic clone I strain), respectively; 13, lambda HindIII-digested DNA (digoxigenin labeled), used as markers; lanes 14 to19, Sau3AI-sensitive strains NCSK98-31, NCSK88-18, NCSK88-6, NCSK87-8, NCSK87-16, and NCSK88-2, respectively.

Southern blotting with the 85R and 85S probes showed that all strains that were 85M positive were also positive with 85R and 85S and, conversely, none of the 85M-negative isolates hybridized with either 85R or 85S (data not shown). The same hybridizing band was observed for all isolates with the 85M and 85R probes, suggesting that the probed fragments were on the same EcoRI fragment in the genome of these strains. This was also in agreement with the sequence analysis of this region, which indicated that these probes were on the same EcoRI genomic fragment in strain F2365. When 85S was used as the probe a band of a different size (ca. 2.7 kb), but identical for all strains, was produced (data not shown), again suggesting lack of polymorphisms in the corresponding EcoRI sites. The hybridization results for all strains with the 85M, 85R, and 85S probes are summarized in Table 1.

Serotype 4b strains with Sau3AI-resistant DNA also harbored additional epidemic clone I-specific genetic markers, unlinked on the serotype 4b genome.

To determine whether the strains with Sau3AI-resistant DNA might also harbor additional genes typical of epidemic clone I, we searched for other sequences reported to be specific to this clone (18). PCR and Southern blots indicated that two of these fragments, 17B and 133, were indeed conserved among all known epidemic clone I strains that we screened, whereas they could not detected in the genomes of other strains of serotype 4b (data not shown). These fragments were unlinked with 85M-85R-85S and with each other on the genome of the epidemic clone I strain F2365 (distance in each case exceeding 170 kb).

The Southern blot results revealed that all food-derived serotype 4b strains that had Sau3AI-resistant DNA and hybridized with 85M, 85R, and 85S also hybridized with the 17B probe (Fig. 2B). Qualitatively identical results were obtained in Southern blots with the other epidemic clone I-specific probe, 133, except that the size of the hybridizing band (3.1 kb) was different from that obtained with the 17B probe (data not shown). Strains with DNA that could be cut with Sau3AI did not yield hybridizing bands with either 133 or 17B (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

In summary, these findings suggest that food-derived strains that had Sau3AI-resistant DNA harbored the putative restriction-modification system genes 85M, 85R, and 85S, as well as additional, genomically unlinked sequences known to be unique to epidemic clone I.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the examination of strains of serotype 4b isolated from routine surveys of food revealed a high incidence of isolates with DNA that appeared to be methylated at the cytosines of GATC sites and thus resisted digestion by Sau3AI, a phenotype associated with strains of a major clonal group (epidemic clone I) implicated in numerous outbreaks (18, 44). These strains harbored genes of a putative restriction-modification system (85M, 85R, and 85S), as well as other, genomically unlinked DNA sequences (such as 17B and 133) characteristic of epidemic clone I. All strains with this combination of genetic markers appeared to be typical serotype 4b isolates in terms of their recognition by the serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies c74.22 and c74.33. None had the distinctive c74.22-negative, c74.33-positive phenotype encountered among certain clinical isolates from outbreaks of listeriosis (8), supporting the earlier speculation that the c74.22-negative phenotype of those clinical isolates was selected in the course of the infection of the human host (8).

The putative involvement of the 85M-85S-85R gene cassette in methylation of cytosines at GATC sites and in a cognate restriction endonuclease activity (specific for GATC sites lacking cytosine methylation) is indicated by the similarities of the deduced polypeptides with GATC-specific methyltransferases and restriction enzymes from other bacteria. Further studies would be needed to clarify the role of each of these genes in restriction-modification of DNA.

The lower than average G+C content of this cassette suggests that the genes may have been introduced into the genome of epidemic clone I bacteria by lateral transfer from a currently unidentified source. Even though restriction-modification genes are widely disseminated among bacteria (3), our results indicate that the food-derived isolates with the Sau3AI-resistant DNA and the 85M-85R-85S gene cassette do not represent random acquisitions of these genes in genetic backgrounds otherwise unrelated to epidemic clone I. Besides the restriction-modification system genes, these isolates harbored additional, genomically unlinked genes specific for epidemic clone I, such as the genes corresponding to fragments 17B and 133, the functions of which are currently unknown. It remains to be determined whether the 85M-85R-85S restriction-modification system may have mediated the acquisition of some of these genes, as has been postulated for restriction-modification systems in other bacterial pathogens (14).

The G+C contents of fragments 17B and 133 are ca. 30%, noticeably lower than the average for the L. monocytogenes genome (38%), suggesting that these genes also were acquired by horizontal transfer from another source. However, even though fragment 133 is internal to a gene that is harbored by epidemic clone I and not other serotype 4b strains, it is also harbored by strains of serotype 1/2b and 3b (18; S. Kathariou and S. Kernodle, unpublished results). This distribution is of interest, since serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b constitute a well-defined genomic division in L. monocytogenes (2, 23, 31). One can speculate that the gene harboring fragment 133 was acquired by a strain ancestral to that division by horizontal transfer and that it was lost by many strains of serotype 4b but maintained by epidemic clone I. These results suggest that the restriction-modification gene cassette (85M-85R-85S) was acquired by a lineage that already harbored some of the genes which are characteristic of epidemic clone I and absent from most other strains of serotype 4b. Regardless of the evolutionary pathways that led to the unique markers of epidemic clone I, our data indicate that these markers are stable genetic attributes of many serotype 4b strains isolated from routine surveys of foods.

In an earlier study of L. monocytogenes strains from animals, foods, and the environment epidemic clone I strains were found relatively frequently among animal isolates but were rarely isolated from foods (4). Epidemic clone I strains were also not identified in a survey of raw, refrigerated meat and poultry (37). However, these studies examined strains from foods regardless of serotype. In general, and for reasons which remain unclear, serotype 4b strains are not predominant in foods, which tend to be contaminated by serotype 1/2 strains, especially 1/2a and 1/2c (23). Our detection of strains with epidemic clone I genetic markers was likely facilitated by our inclusion of a sufficient number of serotype 4b isolates and by the employment of specific genetic markers. Although accurate estimates of the prevalence of such isolates among serotype 4b strains from processed and RTE foods in the United States and elsewhere remain unavailable, the fact that such strains were identified in foods of different types suggests that they may be widely distributed, possibly due to genetic attributes that confer a competitive edge over other strains of serotype 4b in foods or in the food-processing environment.

In bacteria, restriction-modification systems are thought to have evolved partly as a defense against phage invasion, bringing about digestion of unmodified (unmethylated) DNA injected into the cell by the phage (3). It is of interest that GATC sequences are underrepresented in phage genomes (22), possibly to counteract the production of GATC-cleaving endonucleases by potential hosts. Methylation at frequent sites in the genome (such as GATC sites) may also affect other molecular processes. In Salmonella, Dam methylation plays important roles in expression of virulence genes and impacts several key virulence attributes (16). In Escherichia coli, Dam methylation of adenines at GATC sites is important in the regulation of several genes (19, 40) and is impaired by the presence of methylated cytosines at these sites (27). The distribution of GATC sites is not random in the E. coli genome (17, 22, 30), and certain classes of GATC motifs may be involved in transcriptional responses during transitions to decreased temperature and increased oxygen (17, 30). Although similar studies on the distribution of GATC sites in the L. monocytogenes genome have not yet been reported, one may speculate that methylation of such sites in promoter regions might affect the accessibility of the latter to transcriptional activators and influence transcription.

Serotype 4b strains generally tend to be underrepresented in foods but are an important contributor to human listeriosis. It is conceivable that the overall low prevalence of serotype 4b in foods may be counterbalanced by the relatively high incidence of strains with the epidemic clone I markers that we observed in this study. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the genetic and virulence attributes of such strains and to adequately monitor their survival and growth in foods and food-processing environments.

In summary, our results suggest that when foods are contaminated by L. monocytogenes of serotype 4b, the bacteria have a substantial likelihood of harboring genetic markers specific to epidemic clone I, a clonal group implicated in numerous food-borne outbreaks of listeriosis. Employment of the genetic markers described here would greatly facilitate the identification of such serotype 4b strains and could be incorporated in risk assessments of the hazard posed by Listeria contamination of foods.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded in the form of a National Alliance for Food Safety cooperative agreement between the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, North Carolina State University, and Cornell University, through the National Alliance for Food Safety, and by USDA NRI grant 2001-0969. Sequencing of the genome of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b by The Institute for Genomic Research was accomplished with support from the USDA.

We acknowledge Irene Wesley (USDA-ARS, National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa) for valuable feedback and support. We thank B. Swaminathan and L. M. Graves (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for the availability of the reference strains NCLG-5, NCLG-8, and NCLG-11. Kathryn Boor (Cornell University) and Leslie Wolf (North Carolina Department of Health) are thanked for strains NCSK02-16 and NCSK02-3, respectively. Preliminary sequence data of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research through the website at http://www.tigr.org. E. Lanwermeyer is thanked for editorial assistance and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avery, S. M., and S. Buncic. 1997. Differences in pathogenicity for chick embryos and growth kinetics at 37 degrees C between clinical and meat isolates of Listeria monocytogenes previously stored at 4 degrees C. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 34:319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibb, W. F., B. G. Gellin, R. Weaver, B. Schwartz, B. D. Plikaytis, M. W. Reeves, R. W. Pinner, and C. V. Broome. 1990. Analysis of clinical and food-borne isolates of Listeria monocytogenes in the United States by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and application of the method to epidemiologic investigations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2133-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickle, T. A., and D. H. Kruger. 1993. Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol. Rev. 57:434-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boerlin, P., and J. C. Piffaretti. 1991. Typing of human, animal, food, and environmental isolates of Listeria monocytogenes by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1624-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosch, R., B. Catimel, G. Millon, C. Buchrieser, E. Vindel, and J. Rocourt. 1993. Virulence heterogeneity of Listeria monocytogenes strains from various sources (food, human, animal) in immunocompetent mice and its association with typing characteristics. J. Food Prot. 56:296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchrieser, C., R. Brosch, B. Catimel, and J. Rocourt. 1993. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis applied for comparing Listeria monocytogenes strains involved in outbreaks. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:395-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrus, V., C. Bontemps, B. Decaris, and G. Guedon. 2001. Characterization of a novel type II restriction-modification system, Sth368I, encoded by the integrative element ICESt1 of Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ368. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1522-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, E. E., I. Wesley, F. Fiedler, N. Promadej, and S. Kathariou. 2000. Absence of serotype-specific surface antigen and altered teichoic acid glycosylation among epidemic-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3856-3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conner, D. E., V. N. Scott, S. S. Summer, and D. T. Bernard. 1989. Pathogenicity of foodborne, environmental and clinical isolates of Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J. Food Sci. 54:1553-1556. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delcher, A. L., D. Harmon, S. Kasif, O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Corral, F., R. L. Buchanan, M. M. Bencivengo, and P. H. Cooke. 1990. Quantitative comparison of selected virulence associated characteristics in food and clinical isolates of Listeria. J. Food Prot. 53:1003-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy, S. R. 1998. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14:755-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farber, J. M., and P. L. Peterkin. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald, J. R., S. D. Reid, E. Ruotsalainen, T. J. Tripp, M. Y. Liu, R. Cole, P. Kuusela, P. M. Schlievert, A. Jarvinen, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Genome diversification in Staphylococcus aureus: molecular evolution of a highly variable chromosomal region encoding the staphylococcal exotoxin-like family of proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:2827-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, et al. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heithoff, D. M., R. L. Sinsheimer, D. A. Low, and M. J. Mahan. 1999. An essential role for DNA adenine methylation in bacterial virulence. Science 284:967-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henaut, A., T. Rouxel, A. Gleizes, I. Moszer, and A. Danchin. 1996. Uneven distribution of GATC motifs in the Escherichia coli chromosome, its plasmids and its phages. J. Mol. Biol. 257:574-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herd, M., and C. Kocks. 2001. Gene fragments distinguishing an epidemic-associated strain from a virulent prototype strain of Listeria monocytogenes belong to a distinct functional subset of genes and partially cross-hybridize with other Listeria species. Infect. Immun. 69:3972-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernday, A., M. Krabbe, B. Braaten, and D. Low. 2002. Self-perpetuating epigenetic pili switches in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(Suppl. 4):16470-16476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hof, H., and J. Rocourt. 1992. Is any strain of Listeria monocytogenes detected in food a health risk? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 16:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacquet, C., E. Gouin, D. Jeannel, P. Cossart, and J. Rocourt. 2002. Expression of ActA, Ami, InlB, and listeriolysin O in Listeria monocytogenes of human and food origin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:616-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlin, S., I. Ladunga, and B. E. Blaisdell. 1994. Heterogeneity of genomes: measures and values. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12837-12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kathariou, S. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes virulence and pathogenicity, a food safety perspective. J. Food Prot. 65:1811-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kathariou, S. 2003. Foodborne outbreaks of listeriosis and epidemic-associated lineages of Listeria monocytogenes, p. 243-256. In M. E. Torrence and R. E. Isaacson (ed.), Microbial food safety in animal agriculture. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa.

- 25.Kathariou, S., C. Mizumoto, R. D. Allen, A. K. Fok, and A. A. Benedict. 1994. Monoclonal antibodies with a high degree of specificity for Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3548-3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lei, X. H., F. Fiedler, Z. Lan, and S. Kathariou. 2001. A novel serotype-specific gene cassette (gltA-gltB) is required for expression of teichoic acid-associated surface antigens in Listeria monocytogenes of serotype 4b. J. Bacteriol. 183:1133-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClelland, M., M. Nelson, and E. Raschke. 1994. Effects of site-specific modification on restriction endonucleases and DNA modification methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3640-3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Notermans, S., J. Dufrenne, T. Chakraborty, S. Steinmeyer, and G. Terplan. 1991. The chick embryo test agrees with the mouse bio-assay for assessment of the pathogenicity of Listeria species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 13:161-164. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ørskov, F., and I. Ørskov. 1983. Summary of a workshop on the clone concept in epidemiology, taxonomy, and evolution of Enterobacteriaceae and other bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 148:346-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshima, T., C. Wada, Y. Kawagoe, T. Ara, M. Maeda, Y. Masuda, S. Hiraga, and H. Mori. 2002. Genome-wide analysis of deoxyadenosine methyltransferase-mediated control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:673-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piffaretti, J. C., H. Kressebuch, M. Aeschbacher, J. Bille, E. Bannerman, J. M. Musser, R. K. Selander, and J. Rocourt. 1989. Genetic characterization of clones of the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causing epidemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3818-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pine, L., S. Kathariou, F. Quinn, V. George, J. D. Wenger, and R. E. Weaver. 1991. Cytopathogenic effects in enterocytelike Caco-2 cells differentiate virulent from avirulent Listeria strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:990-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Promadej, N., F. Fiedler, P. Cossart, S. Dramsi, and S. Kathariou. 1999. Cell wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b requires gtcA, a novel, serogroup-specific gene. J. Bacteriol. 181:418-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramnath, M., K. B. Rechninger, L. Jansch, J. W. Hastings, S. Knochel and A. Gravesen. Development of a Listeria monocytogenes EGDe partial proteome reference map and comparison with the protein profiles of food isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3368-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Rocourt, J., C. Jacquet, and J. Bille. 1997. Human listeriosis. Publication W.H.O./FNU/FOS/97.1. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 36.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M-A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryser, E. T., S. M. Arimi, M. M.-C. Bunduki, and C. W. Donnelly. 1996. Recovery of different Listeria ribotypes from naturally contaminated, raw refrigerated meat and poultry products with two primary enrichment media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1781-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuchat, A., B. Swaminathan, and C. V. Broome. 1991. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:169-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seeber, S., C. Kessler, and F. Gotz. 1990. Cloning, expression and characterization of the Sau3AI restriction and modification genes in Staphylococcus carnosus TM300. Gene 94:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slominska, M., G. Konopa, J. Ostrowska, B. Kedzierska, G. Wegrzyn, and A. Wegrzyn. 2003. SeqA-mediated stimulation of a promoter activity by facilitating functions of a transcription activator. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1669-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tran, H. L., and S. Kathariou. 2002. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms detected with novel DNA probes differentiate among diverse lineages of serogroup 4 Listeria monocytogenes and identify four distinct lineages in serotype 4b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:59-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Twomey, D. P., L. L. McKay, and D. J. O'Sullivan. 1998. Molecular characterization of the Lactococcus lactis LlaKR2I restriction-modification system and effect of the IS982 element positioned between the restriction and modification genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:5844-5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, W., and S. Kathariou. 1995. Differentiation of epidemic-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes by restriction fragment length polymorphism in a gene region essential for growth at low temperatures (4°C). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4310-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng, W., and S. Kathariou. 1997. Host-mediated modification of Sau3AI restriction in Listeria monocytogenes: prevalence in epidemic-associated strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3085-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]