Abstract

Introduction

Oral formulations of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) for treatment of ulcerative colitis have been developed to minimize absorption prior to the drug reaching the colon. In this study, we investigate the release of 5-ASA from available oral mesalamine formulations in physiologically relevant pH conditions.

Methods

Release of 5-ASA from 6 mesalamine formulations (APRISO®, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., USA; ASACOL® MR, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd.; ASACOL® HD, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, USA; MEZAVANT XL®, Shire US Inc.; PENTASA®, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., UK; SALOFALK®, Dr. Falk Pharma UK Ltd.) was evaluated using United States Pharmacopeia apparatus I and II at pH values of 1.0 (2 h), 6.0 (1 h), and 6.8 (8 h). Dissolution profiles were determined for each formulation, respectively.

Results

Of the tested formulations, only the PENTASA formulation demonstrated release of 5-ASA at pH 1.0 (48%), with 56% cumulative release after exposure to pH 6.0 and 92% 5-ASA release after 6–8 h at pH 6.8. No other mesalamine formulation showed >1% drug release at pH 1.0. The APRISO formulation revealed 36% 5-ASA release at pH 6.0, with 100% release after 3 h at pH 6.8. The SALOFALK formulation revealed 11% 5-ASA release at pH 6.0, with 100% release after 1 h at pH 6.8. No 5-ASA was released by the ASACOL MR, ASACOL HD, and MEZAVANT XL formulations at pH 6.0. At pH 6.8, the ASACOL MR and ASACOL HD formulations exhibited complete release of 5-ASA after 4 and 2 h, respectively, and the MEZAVANT XL formulation demonstrated complete 5-ASA release over 6–7 h.

Conclusion

5-Aminosalicylic acid release profiles were variable among various commercially available formulations.

Funding

Shire Development LLC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0206-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 5-Aminosalicylic acid, Dissolution, Gastroenterology, Mesalamine, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic mucosal inflammatory condition that can affect any part of the colon, and is characterized by periods of remission and active disease associated with symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and fecal urgency [1, 2]. While the complete etiology of UC remains unclear, risk factors include genetic predisposition, history of bacterial infections, and lifestyle factors [1]. Approximately 50% of patients with quiescent UC may relapse within a given year [3], highlighting the importance of treatments that enable effective management of the disease.

Mesalamine (5-aminosalicylic acid [5-ASA]), a locally acting, anti-inflammatory compound that reduces inflammation of the colonic mucosa, is recommended first-line treatment for patients with mild-to-moderate UC [4–6]. Available in both oral and topical formulations, 5-ASA is generally well tolerated and has proven to be effective in symptom improvement as well as in the induction and maintenance of UC remission [5, 7–10]. For 5-ASA to be effective in treating mild-to-moderate UC, the drug must be able to directly target the mucosa of the terminal ileum and colon, where it negatively regulates cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways to prevent formation of prostaglandin and leukotrienes [11], and increases the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors [12]. Immediate-release oral mesalamine formulations result in the quick absorption of 5-ASA in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with systemically absorbed drug having little clinical effect [13, 14]. Therefore, some controlled-release oral formulations of mesalamine have been developed to control or delay the release of the active 5-ASA to provide stable delivery of 5-ASA to the colon [13, 15–18].

Many of these controlled-release formulations are pH dependent, with enteric coatings, and developed on the understanding that the pH gradient of the human GI tract progressively increases from the stomach (approximately pH 2) to the small intestine (approximately pH 6) to the colon (pH 7–8) [19]. The enteric coatings of these formulations were designed to resist the highly acidic environment of the stomach and dissolve in the more basic environment of the terminal ileum (around pH 7). However, consistent release of 5-ASA from pH-dependent formulations may be hindered by fluctuations of intestinal pH levels in patients with UC, in whom colonic pH levels have been measured at lower than pH 7 due to a variety of factors, including reduced mucosal bicarbonate secretion, increased mucosal and bacterial lactate production, and impaired absorption and metabolism of short-chain fatty acids [19, 20]. In addition, considerable tablet-to-tablet variability in dissolution has been observed for one pH-dependent release formulation (ASACOL®; Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd., Surrey, UK) at pH <7 [21]. Therefore, in patients with UC, release of 5-ASA may be inconsistent and unpredictable from some oral mesalamine formulations.

While previous studies have examined the dissolution profiles of individual mesalamine formulations, to date there has been no comparative study that has examined the dissolution profiles of various currently available controlled-release mesalamine formulations. To directly address this question, we examined 5-ASA release at physiologically relevant pH values from 6 mesalamine formulations: APRISO® extended-release capsules (Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA); ASACOL® MR tablets (Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd., Surrey, UK); ASACOL® HD tablets (Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, OH, USA); MEZAVANT XL® tablets (Shire US Inc., Wayne, PA, USA); PENTASA® tablets (Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., West Drayton, UK); and SALOFALK® tablets (Dr. Falk Pharma UK Ltd., Bourne End, UK).

Methods

Dissolution experiments were conducted with the following mesalamine formulations: APRISO 0.375-g capsules; ASACOL MR 800-mg tablets; ASACOL HD 800-mg tablets; MEZAVANT XL 1.2-g tablets; PENTASA 500-mg tablets; and SALOFALK 250-mg tablets. All drug products used in the study were the commercially available formulations. With the exception of MEZAVANT XL, all the mesalamine formulations were sourced from retail outlets, and dissolution data were collected on 6 units (tablets or capsules) of each; the European Pharmacopoeia and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) minimum requirement for dissolution testing is 6 dosage units. For MEZAVANT XL, tablets were sourced directly from Shire, the product’s manufacturer, who provided the dissolution data on 12 dosage units. USP apparatus I (basket) was used for the APRISO capsules, while USP apparatus II was used for all other tablet formulations (Sotax AT7™ dissolution tester; Sotax Corporation, Horsham, PA, USA) [22]. The USP apparatus type was selected as such to permit placement of the respective drug forms (capsule or tablet) into the dissolution media for the duration of the test without interfering with the ability to observe them.

To investigate the effect of simulated GI conditions on release of active 5-ASA, dissolution testing was performed in 3 stages. An initial acid stage (2 h at pH 1.0) was followed by a 2-part buffer stage (1 h at pH 6.0 followed by 8 h at pH 6.8; Table 1). The dissolution bath was maintained at a mean (±standard deviation [SD]) temperature of 37 °C (±5 °C), and the quantitative determination of the amount of 5-ASA released was measured by ultraviolet visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometry at wavelengths of 301 nm at pH 1.0, and 330 nm for both pH 6.0 and 6.8 (PerkinElmer Lambda 25™; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The proportion of 5-ASA dose released was calculated as a mean value of all units at each time point for each formulation. While all drug products are theoretically formulated to contain 100% of the labeled active concentrations, differences may occur in measured or reported concentrations due to the variability introduced by manufacturing or by analytical methods. The USP allows for a range of 90–110% of the labeled drug content.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions used to study 5-ASA release from mesalamine (USP apparatus I and II)

| Stage | Experimental conditions |

|---|---|

| Acid stage | |

| Dissolution media | 500 mL, HCl 0.1 N |

| pH | 1–1.2 |

| Incubation time, h | 2 |

| Sample time, h | 0.5 |

| Rotation speed, rpm | 50 |

| Buffer stage 1 | |

| Dissolution media | 900 mL, 0.16 M phosphate buffer |

| pH | 6.0 |

| Incubation time, h | 1 |

| Sample time, h | 1 |

| Rotation speed, rpm | 100 |

| Buffer stage 2 | |

| Dissolution media | 900 mL, 0.16 M phosphate buffer |

| pH | 6.8 |

| Incubation time, h | 8 |

| Sample time, h | 0.5 |

| Rotation speed, rpm | 100 |

USP I method was used with APRISO capsules; USP II was used with all other tablet formulations

5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid, USP United States Pharmacopeia

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

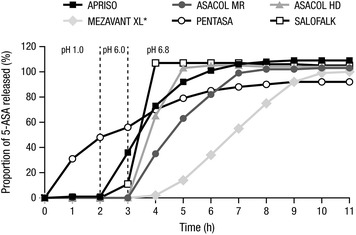

The dissolution profiles of all tested mesalamine formulations are shown in Fig. 1. The APRISO formulation demonstrated consistent release of 5-ASA across individual capsules at each pH (see Table 2 for SDs at pH 6.8). After 2 h at pH 1.0, 1% of 5-ASA was released; a total of 36% of 5-ASA was released after a subsequent hour at pH 6.0, and the remaining drug was released over 3 h at pH 6.8, with 73% of 5-ASA being released after 1 h at pH 6.8. For the ASACOL MR formulation, no drug was released at either pH 1.0 or 6.0; however, 100% of 5-ASA was released on average after about 4 h of exposure to pH 6.8, with 35% and 63% of 5-ASA release being observed after 1 and 2 h at pH 6.8. Considerable variability between individual tablets in their release characteristics was observed in the minimum and maximum drug release profiles over time; some tablets did not release 100% of drug until about 7 h at pH 6.8. Like the ASACOL MR formulation, the ASACOL HD formulation demonstrated no drug release at either pH 1.0 or 6.0, but 100% of 5-ASA was released from all tablets after about 2 h at pH 6.8, with 65% of 5-ASA release being observed after 1 h at pH 6.8. Some tablet-to-tablet variability in 5-ASA release was observed with the ASACOL HD formulation.

Fig. 1.

Dissolution of 5-ASA formulations in simulated gastrointestinal pH ranges. *n = 12 for MEZAVANT XL; n = 6 for all other formulations. 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

Table 2.

Average and tablet-to-tablet variability in dissolution at pH 6.8

| Time, h | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation | Mean (SD) dissolution, % | |||||||

| APRISO | 73.46 (2.88) | 92.17 (3.20) | 101.43 (3.40) | 106.20 (3.62) | 108.08 (3.72) | 108.82 (3.81) | 109.08 (3.81) | 109.06 (3.81) |

| ASACOL MR | 34.83 (41.61) | 63.01 (42.71) | 81.81 (32.60) | 98.57 (8.91) | 101.74 (5.23) | 101.87 (3.15) | 103.03 (2.14) | 103.33 (1.89) |

| ASACOL HD | 65.00 (44.65) | 102.70 (4.61) | 104.50 (0.66) | 104.55 (0.36) | 104.47 (0.6) | 103.98 (0.7) | 103.63 (0.58) | 103.65 (0.55) |

| SALOFALK | 107.40 (2.00) | 106.95 (1.82) | 106.59 (1.79) | 106.56 (1.76) | 106.32 (1.75) | 105.94 (1.77) | 105.43 (1.82) | 104.80 (1.89) |

| PENTASA | 69.88 (7.79) | 78.59 (5.47) | 84.52 (3.96) | 87.82 (2.73) | 90.00 (2.13) | 91.51 (1.72) | 91.86 (1.66) | 92.19 (1.65) |

| MEZAVANT XL | 2.22 (0.87) | 13.73 (2.76) | 34.10 (5.29) | 55.25 (6.42) | 74.77 (6.51) | 91.79 (5.87) | 99.12 (1.90) | 99.69 (0.83) |

SD standard deviation

The MEZAVANT XL formulation also exhibited no drug release at pH 1.0 and 6.0, and 5-ASA release occurred over 6 h at pH 6.8; after 3 h at pH 6.8, approximately 33% of 5-ASA had been released, and after 5 h, about 75% of 5-ASA had been released. Dissolution behavior was similar across tablets. Unlike the other tested formulations, the dissolution profile from the PENTASA formulation did not appear to be pH sensitive and, therefore, demonstrated pH-independent release of 5-ASA. Continuous release of 5-ASA was observed with the PENTASA formulation at each pH: at pH 1.0, 48% of the drug was released in 2 h; after an additional hour at pH 6.0, a cumulative amount of 56% was released; at pH 6.8, 70% and 85% of 5-ASA had been released after 1 and 3 h, respectively, with a mean maximum release of 92% achieved after 8 h. The PENTASA formulation also demonstrated consistent release of 5-ASA across individual tablets. Lastly, the SALOFALK formulation demonstrated no drug release at pH 1.0, 11% release at pH 6.0, and complete drug release within 1 h of exposure at pH 6.8. Similar 5-ASA release profiles were observed across individual SALOFALK tablets.

Discussion

As the pH profile in the colon can vary in patients with UC, with pH <7.0 reported in some cases, non-homogenous release of 5-ASA for enteric-coated, pH-dependent formulations may occur [19, 23–25]. In the current study, the dissolution rates of different mesalamine formulations were compared at pH 6.8. Results revealed a high degree of variation in release profiles across different formulations.

All tested mesalamine formulations, except for the PENTASA formulation, had little to no release of 5-ASA at pH 1.0, while varying degrees of 5-ASA release were observed at pH 6.0 and pH 6.8. The PENTASA formulation released 5-ASA in a manner independent of pH level, with steady continuous release over time. In general, the enteric coatings of the other tested formulations were designed to dissolve at higher pH levels, such as those typically observed in the lower sections of the GI tract. After 1 h at pH 6.0, the APRISO formulation released more than one-third of its active 5-ASA. Both the ASACOL MR and ASACOL HD formulations did not release the active drug at pH 6.0; 3 of 6 tested ASACOL MR tablets did not release any drug for the first hour at pH 6.8, while drug release across ASACOL HD tablets at pH 6.8 was more consistent. In a prior study by Spencer et al. [21], release of 5-ASA from the ASACOL 400-mg tablets at pH <7.0 exhibited considerable variability from tablet to tablet, though more consistent release was observed at pH 7.2. In that study, USP apparatus II was used to test dissolution of the ASACOL tablet in a similarly staged acid and buffer procedure: 2 h at pH 1.2 stirring at 50 rpm, 1 h at pH 6.0 stirring at 100 rpm, and finally 1.5 h at either pH 6.5, 6.8, or 7.2 stirring at 50 rpm. While 100% of 5-ASA was released from the ASACOL tablets within 2 h at pH 7.2, complete release of 5-ASA was observed after 5 h at pH 6.8, whereas only approximately 50% of 5-ASA was released after 6 h at pH 6.5. Although it was postulated that differences in tablet film-coat thickness could account for the variability in 5-ASA release from the tablets, a direct correlation between film-coat thickness and dissolution performance could not be made [21]. It should be noted that the ASACOL 400-mg tablets examined by Spencer et al. [21] are no longer commercially available, and differ from the ASACOL HD 800-mg and the ASACOL MR 800-mg formulations currently investigated. The current study demonstrated complete release of 5-ASA from the ASACOL tablets within 2 h (ASACOL HD formulation) to 4 h (ASACOL MR formulation) at pH 6.8, with high tablet-to-tablet variability observed in the latter. Without additional insight into the formulation or manufacturing process for either ASACOL HD or ASACOL MR, it remains unclear why the dissolution profiles of these two formulations differed from one other.

In contrast to the ASACOL MR formulation, 5-ASA release from other formulations (PENTASA, APRISO, MEZAVANT XL, and SALOFALK) was found to be relatively consistent between tablets at pH 6.8. The MEZAVANT XL formulation did not release any drug at pH 6.0, but exhibited complete drug release within 6–7 h at pH 6.8. Another study examining the release profile of 5-ASA from the MEZAVANT XL formulation [26] also revealed minimal tablet-to-tablet variation, and this observation was associated with consistent film-coat thickness among the tablets examined. Finally, the SALOFALK tablets released 11% of 5-ASA at pH 6.0, then exhibited rapid release of the remainder of its 5-ASA in less than 1 h at pH 6.8.

Results from D’Inca and colleagues [27] showed that mesalamine formulations with pH-dependent release achieved significantly higher mucosal concentrations of 5-ASA within the diseased colon in patients with UC compared with time-dependent mesalamine release formulations or pro-drugs. However, it remains unclear whether the current study findings regarding variability of release in vitro have an effect in vivo. Thus, the clinical relevance of these findings remains to be elucidated.

Conclusions

In summary, significant variations were observed between the dissolution profiles of 6 mesalamine formulations examined at a range of pH values, with a few formulations also exhibiting wide tablet-to-tablet variation in the release of 5-ASA. However, it is still not known whether a correlation exists between the in vitro dissolution profiles of these formulations and their release characteristics in the colon. Additional studies will be needed to determine if these findings are clinically relevant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Results from this study were previously presented at the 2011 Congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) and the 2014 Canadian Digestive Diseases Week (CDDW). Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by the sponsor, Shire Development LLC. Cosmo Pharmaceuticals received funding from Shire Development LLC for assistance with data collection and data analysis. Under the direction of the authors, writing and editorial support was provided by Jason Jung, PhD, of MedErgy. Editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copy editing, and fact checking was also provided by MedErgy. Shire Development LLC provided funding to MedErgy for support in writing and editing this manuscript. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Adeyinka Abinusawa is an employee of Shire, and holds stock and/or stock options at Shire. Srini Tenjarla is an employee of Shire, and holds stock and/or stock options at Shire.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Contributor Information

Adeyinka Abinusawa, Email: aabinusawa@shire.com.

Srini Tenjarla, Email: stenjarla@shire.com.

References

- 1.Adams SM, Bornemann PH. Ulcerative colitis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 2013;346:f432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501–523. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutherland L, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD000543. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Travis SP, Stange EF, Lemann M, et al. European evidence-based Consensus on the management of ulcerative colitis: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:24–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Barrett K, Hodgson I, Streck P. Once-daily MMX® mesalamine for endoscopic maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1064–1077. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane S, Katz S, Jamal MM, et al. Strategies in maintenance for patients receiving long-term therapy (SIMPLE): a study of MMX mesalamine for the long-term maintenance of quiescent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1026–1033. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, Lyne A, Joseph RE. MMX mesalazine for the induction of remission of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: efficacy and tolerability in specific patient subpopulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandborn WJ, Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Lyne A, Butler T, Joseph RE. MMX Multi Matrix System mesalazine for the induction of remission in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a combined analysis of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ligumsky M, Karmeli F, Sharon P, Zor U, Cohen F, Rachmilewitz D. Enhanced thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin production by cultured rectal mucosa in ulcerative colitis and its inhibition by steroids and sulfasalazine. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:444–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rousseaux C, Lefebvre B, Dubuquoy L, et al. Intestinal antiinflammatory effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid is dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1205–1215. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen SN, Bondesen S, Hvidberg EF, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid in a slow-release preparation: bioavailability, plasma level, and excretion in humans. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1062–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shafii A, Chowdhury JR, Das KM. Absorption, enterohepatic circulation, and excretion of 5-aminosalicylic acid in rats. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:297–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner M, Assandri R, Kletter K, et al. Gastrointestinal transit and 5-ASA release from a new mesalazine extended-release formulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Becker NQ, Moss AC. Improving delivery of aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: effect on patient outcomes. Drugs. 2008;68:1089–1103. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layer PH, Goebell H, Keller J, Dignass A, Klotz U. Delivery and fate of oral mesalamine microgranules within the human small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1427–1433. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA. Review article: 5-aminosalicylate formulations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis—methods of comparing release rates and delivery of 5-aminosalicylate to the colonic mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent SG, Kumar D, Rampton DS, Evans DF. Intestinal luminal pH in inflammatory bowel disease: possible determinants and implications for therapy with aminosalicylates and other drugs. Gut. 2001;48:571–577. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernia P, Caprilli R, Latella G, Barbetti F, Magliocca FM, Cittadini M. Fecal lactate and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1564–1568. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer JA, Gao Z, Moore T, et al. Delayed release tablet dissolution related to coating thickness by terahertz pulsed image mapping. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:1543–1550. doi: 10.1002/jps.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.USP. United States Pharmacopeia dissolution testing standards. Chapter 711. http://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/USPNF/2011-02-25711DISSOLUTION.pdf. Accessed Sept 26, 2013.

- 23.Fallingborg J, Christensen LA, Jacobsen BA, Rasmussen SN. Very low intraluminal colonic pH in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1989–1993. doi: 10.1007/BF01297074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fallingborg J. Intraluminal pH of the human gastrointestinal tract. Dan Med Bull. 1999;46:183–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Press AG, Hauptmann IA, Hauptmann L, et al. Gastrointestinal pH profiles in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:673–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenjarla S, Abinusawa A. In-vitro characterization of 5-aminosalicylic acid release from MMX mesalamine tablets and determination of tablet coating thickness. Adv Ther. 2011;28:62–72. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Inca R, Paccagnella M, Cardin R, et al. 5-ASA colonic mucosal concentrations resulting from different pharmaceutical formulations in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5665–5670. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.