Abstract

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), used frequently in solid organ transplant patients, are known to inhibit T cell proliferation, but their effect on humoral immunity is far less studied. Total and naive B cells from healthy adult donors were cultured in immunoglobulin (Ig)A- or IgG/IgE-promoting conditions with increasing doses of cyclosporin, tacrolimus, rapamycin or methylprednisolone. The effect on cell number, cell division, plasmablast differentiation and class-switching was tested. To examine the effect on T follicular helper (Tfh) cell differentiation, naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with interleukin (IL)-12 and titrated immunosuppressive drug (IS) concentrations. Total B cell function was not affected by CNI. However, naive B cell proliferation was inhibited by cyclosporin and both CNI decreased plasmablast differentiation. Both CNI suppressed IgA, whereas only cyclosporin inhibited IgE class-switching. Rapamycin had a strong inhibitory effect on B cell function. Strikingly, methylprednisolone, increased plasmablast differentiation and IgE class-switching from naive B cells. Differentiation of Tfh cells decreased with increasing IS doses. CNI affected humoral immunity directly by suppressing naive B cells. CNI, as well as rapamycin and methylprednisolone, inhibited the in-vitro differentiation of Tfh from naive CD4+ T cells. In view of its potent suppressive effect on B cell function and Tfh cell differentiation, rapamycin might be an interesting candidate in the management of B cell mediated complications post solid organ transplantation.

Keywords: B cells, calcineurin inhibitors, immunoglobulins, immunosuppression, T follicular helper cells

Introduction

Significant progress has been made in preventing acute allograft rejection following solid organ transplantation resulting in improved allograft survival. Chronic rejection, however, remains a major hurdle menacing the long-term function of the transplanted organs. Alloimmune responses defined primarily by the development of antibodies to donor-mismatched major histocompatibility antigens, as well as the development of autoantibodies to organ-specific self-antigens, are involved in the pathogenesis of chronic allograft rejection 1.

Furthermore, autoimmune disorders such as de-novo autoimmune hepatitis post-liver transplantation 2, as well as de-novo-acquired allergic conditions post-transplant, are well-known complications following solid organ transplantation. The use of tacrolimus has been associated with allergic diseases and elevated IgE in several transplant populations 3–5.

For many years, calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) such as cyclosporin (CyA) and tacrolimus (FK506) have formed the keystone of most maintenance immunosuppression protocols in solid organ transplantation 6. Nowadays, the use of FK506 is preferred to CyA because of its superiority in the prevention and treatment of rejection 7,8. CNI are known to inhibit T cell proliferation by holding in nuclear factor of activated T cells and interleukin (IL)-2 gene transcription 9. Their effect on the humoral immune response, however, is far less studied and remains to be elucidated 10.

CNI are known to alter the balance between different CD4+ T cell subsets, particularly by suppression of regulatory T cells 11,12. More recently an additional T cell subset, known as T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, which are CD4+ T helper cells specialized in providing help to B cells and regulating humoral immune responses, has been identified. Tfh cells control the development of antigen-specific B cell immunity 13 and have been implicated in autoimmune diseases 14–16. Tfh cells are essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centres and for the generation of most memory B cells and plasma cells 17,18, providing CD40 ligand and multiple cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-21 19–22. These signals promote B cell proliferation, class-switch recombination and somatic hypermutation, resulting in highly specific class-switched plasma cells and long-lived memory B cells 23–25. The original feature used to identify Tfh cells is expression of chemokine receptor CXCR5 19,26. Another important characteristic is the secretion of IL-21, which is the ‘signature' cytokine of Tfh cells 17. Immunosuppressive drugs, such as tacrolimus, could influence humoral immunity by acting on B cells directly or on Tfh cells. Antigen, CD40 and IL-21 are absolute requirements for T cell-dependent B cell activation, resulting in proliferation, class-switching and differentiation into memory B cells or plasma cells. IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 drive immunoglobulin (Ig)A class-switching 25,27, whereas IL-4 induces IgE-switching 28.

As very few data are available on the effect of immunosuppressive drugs on humoral immunity, we examined the direct in-vitro effect of immunosuppression (FK506, CyA, rapamycin, methylprednisolone) on differentiation and class-switching of total and naive B cells. Furthermore, we studied the effect of these immunosuppressive drugs on Tfh cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells, as they also influence the humoral immune response.

We demonstrate here that CNI exert a direct effect on humoral immunity by suppressing naive B cells. Tfh cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells was inhibited by all immunosuppressive drugs used.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell cultures

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque density gradient (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) from buffycoats of healthy adult blood donors (Blood Transfusion Center Oost-Vlaanderen, Red Cross). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University Hospital (BTC20130116).

B cells were isolated from the lymphocyte-rich fractions using a human B cell enrichment set (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). To obtain naive B cells, the cells were stained for CD3, CD19, IgD and CD27. CD27– IgD+ naive B cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). The purity of sorted B cells was generally >98%.

Total and naive B cells were cultured in 96-well U-bottomed plates with RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma), 1% non-essential amino acids (MEM NEAA; Gibco), 1 mM sodiumpyruvate (Gibco) and 0·05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco) at 5–10 × 104 cells/200 μl/well in the presence of IL-2 (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-CD40 antibody (1 μg/ml, clone 12E12; a kind gift from Sandra Zurawski, Baylor Institute, Dallas, TX, USA) and IL-21 (20 ng/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Prior to culture, B cells were labelled with 0·5 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen) to track proliferation. Class-switching was induced by adding, respectively, human recombinant TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml; R&D Systems) and cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) (50 nM; ODN2006; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) for IgA class-switching and IL-4 (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for IgG and IgE class-switching. Immunosuppressive drugs were added, titrated in three different concentrations (final concentrations in culture): methylprednisolone and FK506 (10−9 M, 10−8 M, 10−7 M), rapamycin (0·1 ng/ml, 1 ng/ml, 10 ng/m) and CyA (10 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, 1000 ng/ml). The immunosuppressive drugs were diluted in tissue culture medium (RPMI + additives) at least 1/1000 for cyclosporin and at least 1/10 000 for methylprednisolone and tacrolimus; the initial stock solutions were stored in ethanol. The medium concentrations of FK506 (8·04 ng/ml) and CyA (100 ng/ml) are similar to target trough serum levels during the first year after liver transplantation. Target trough serum levels for rapamycin during the first year post-transplant are situated between the medium and highest dose of rapamycin used in the experiments. Cells were incubated at 37 °C. After 7 days, supernatant was harvested and cells stained for flow cytometry.

Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMC of healthy adult donors by negative selection (human naive CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotec). Cell purity checked with flow cytometry was always ≥95%. Cells were cultured in 96-well U-bottomed plates with complemented RPMI-1640 at 2 × 105 cells/200 μl/well in the presence of IL-12 (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems), plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), soluble anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml; Biolegend) to facilitate T cell differentiation and induce Tfh cells 29. Prior to culture, T cells were labelled with 0·5 μM cell trace violet (CTV) (Invitrogen) to track proliferation. Titrated doses of methylprednisolone, FK506, rapamycin and CyA were added (cfr supra). Cells were incubated at 37 °C. Supernatant was harvested after 48 h and cells stained for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with fixable viability dye 506 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and fluorescently labelled monoclonal antibodies using the manufacturer's instructions. The following monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-CD27, anti-CD38, anti-human IgD, anti-human IgG, anti-human IgE (all BD Biosciences), anti-human IgA (Miltenyi Biotech), avidin/streptavidin (eBioscience) and anti-human CD4 (Biolegend).

To activate naive CD4+ T cells and subsequently measure their cytokine production by intracellular flow staining, the cells were incubated with 100 μg/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 mM GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for 5 h at 37 °C. Intracellular staining of CD4+ T cells was performed using PermFix and PermWash (BD Biosciences), and anti-human IL-21 (eBioscience) and interferon (IFN)-γ (Biolegend).

Cells were sorted on a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Aria (BD Biosciences) and acquired on a LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences). At least 100 000 events per sample were recorded. Counting beads (flow cytometry absolute count standard, full spectrum; Bang Laboratories, Fishers, IN, USA) were used to calculate the absolute number of cells based on the obtained cell percentages.

Data were analysed using FlowJo software version 9·4·11 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assaya (ELISAs)

ELISAs were performed to measure total IgG, IgE and IgA in the culture supernatant (human IgG, IgE and IgA ELISA; Mabtech, Cincinnati, OH, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

IFN-γ and IL-21 levels were measured in culture supernatant of naive CD4+ T cells (specific human ELISA ‘Ready-SET-Go!' second-generation kits; eBioscience) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism software. Differences between groups were compared using Friedman's test. Dunn's multiple comparison test was performed and adjusted P-values given. A P-value ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. To compensate for interdonor variability, we normalized the data by dividing the measured values by the value of the condition without immunosuppression of the corresponding donor.

Results

As the direct effect of CNI on the humoral immune response is not well known, we used an in-vitro B cell class-switching system to test the effect of CNI, rapamycin and methylprednisolone on several aspects of B cell differentiation.

Supporting information, Fig. S1 illustrates the levels of IgA, E and G secretion obtained from naive B cells with our in-vitro class-switching system. IgA class-switching was induced by IL-21 + TGF-β1 and both IgE and IgG class-switching were induced by IL-21 + IL-4 (in addition to anti-CD40 antibody and IL-2).

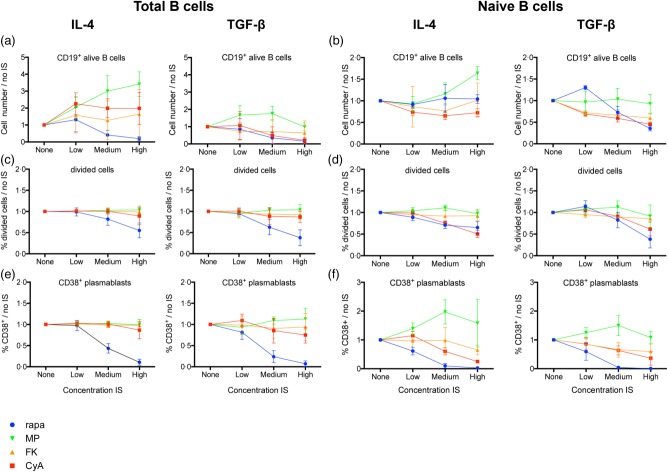

Effect of immunosuppression on number of cells, cell division and plasmablast differentiation

Total and naive B cells were cultured in IgA (TGF-β)- or IgG/IgE (IL-4)-promoting conditions in the presence of increasing doses of immunosuppression.

Both CyA and FK506 decreased the number of CD19+ B cells in the TGF-β condition of total (P < 0·001; P = 0·002) and naive (P = 0·002; P = 0·02) B cells (Fig. 1a,b). In naive B cells, CyA had a strong dose-dependent inhibitory effect on division capacity (P = 0·02), while FK506 only suppressed cell division in the TGF-β condition of naive B cells (P < 0·001) (Fig. 1c,d). CyA (P = 0·02) and FK506 (P = 0·02; P < 0·001) both significantly suppressed CD38+ plasmablast differentiation in naive but not in total B cells (Fig. 1e,f).

Fig 1.

Influence of immunosuppression on B cell division and differentiation in vitro. Total and naive B cells were cultured for 7 days with or without immunosuppressive drugs (IS) in immunoglobulin (Ig)G-/IgE- [interleukin (IL)-4] and IgA- [transforming growth factor (TGF)-β] promoting conditions. Proliferation and CD38+ plasmablast differentiation were analysed using flow cytometry. Mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of five different healthy donors without or with titrated doses of IS are plotted for CD19+ alive B cell count (a,b), percentage of divided cells [carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)] (c,d) and percentage of CD38+ plasmablasts (e,f). Per donor, the measured values were divided by the value of the condition without IS (‘none'), to compensate for interdonor variability. Rapa = rapamycin; MethylPred = methylprednisolone; FK506 = tacrolimus; CyA = cyclosporin A.

Rapamycin strongly suppressed B cell numbers in total B cells (P ≤ 0·001) and in the TGF-β condition of naive B cells (P = 0·002) (Fig. 1a,b). There was a strong dose-dependent inhibitory effect on division capacity and CD38+ plasmablast differentiation in total and naive B cells (all P < 0·001) (Fig. 1c–f).

In total B cells, methylprednisolone increased B cell numbers significantly in the IL-4 condition (P ≤ 0·001) with the same trend present in the naive B cells (Fig. 1a,b). Strikingly, in naive B cells, methylprednisolone had a stimulating effect on CD38+ plasmablast differentiation in low and especially medium (P = 0·007; P = 0·001) doses. In the medium concentration of the IL-4 condition, CD38+ plasmablasts nearly doubled compared to the control condition without immunosuppression. This effect was absent in total B cells (Fig. 1e,f).

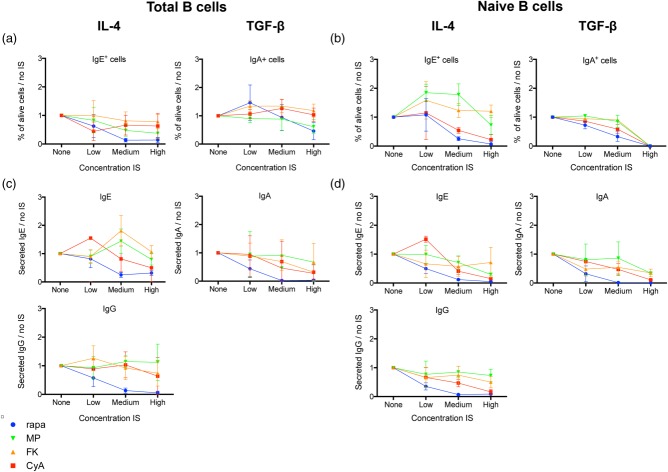

Effect of immunosuppression on Ig class-switching

In total B cells, CyA and FK506 did not exhibit any significant effect on either IgA or IgE class-switching, while both had a dose-dependent suppressive effect on IgA class-switching (P = 0·002; P < 0·001) and IgA secretion (P = 0·04; P = 0·02) in naive B cells. Moreover, increasing doses of CyA suppressed IgE class-switching (P = 0·02) and IgE secretion (P = 0·04) in naive B cells, but FK506 did not affect IgE class-switching or IgE secretion significantly in these cells (Fig. 2a–d).

Fig 2.

Influence of immunosuppression on immunoglobulin class-switching and secretion in vitro. Total and naive B cells were cultured for 7 days with or without immunosuppressive drugs (IS) in immunoglobulin (Ig)G-/IgE- [interleukin (IL)-4] and IgA- [transforming growth factor (TGF)-β] promoting conditions. Surface Ig expression was analysed by flow cytometry. Mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of five different healthy donors without or with titrated doses of IS are plotted for IgE and IgA surface staining (a,b). Secreted IgE, IgA and IgG were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in supernatant and the mean ± s.d. of five different healthy donors was plotted (c,d). Per donor, the measured values were divided by the value of the condition without IS (‘none'), to compensate for interdonor variability. Rapa = rapamycin; MethylPred = methylprednisolone; FK506 = tacrolimus; CyA = cyclosporin A.

Rapamycin inhibited IgA as well as IgE class-switching in total and naive B cells (all P < 0·001) (Fig. 2a,b). Rapamycin also induced a significant dose-dependent decrease in IgA secretion in total (P < 0·001) and naive (P = 0·02) B cells. IgE secretion was suppressed in naive B cells only (P = 0·001) (Fig. 2c,d).

Methylprednisolone inhibited IgA (P = 0·002) and IgE (P = 0·02) class-switching in total B cells (P ≤ 0·02) (Fig. 2a). IgA class-switching was suppressed in naive B cells (P = 0·002), but IgE class-switching was induced in low and medium (P = 0·003) concentrations (Fig. 2b). IgE secretion, on the contrary, was suppressed significantly in naive B cells (P = 0·02) (Fig. 2d).

Rapamycin strongly decreased IgG secretion in all conditions of total (P < 0·001) and naive (P = 0·01) B cells. There was no significant effect of CNI or methylprednisolone on IgG secretion (Fig. 2c,d).

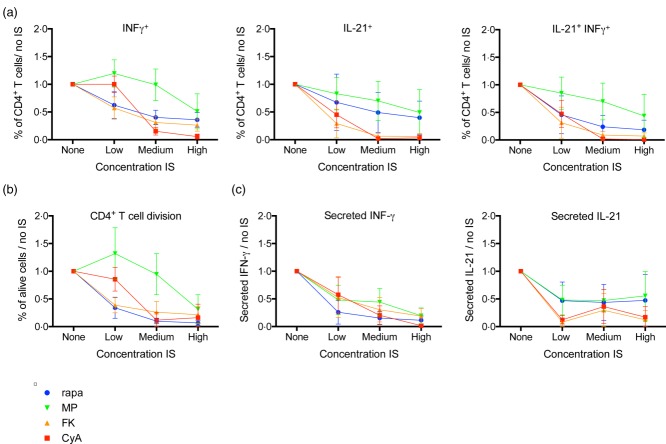

CNI strongly suppress in-vitro induction of IL-21 expressing Tfh cells

To examine the effect of immunosuppressive drugs on Tfh cell differentiation, we cultured naive CD4+ T cells from healthy adult donors with IL-12 (to stimulate Tfh cell skewing) 29 and titrated concentrations of CyA, FK506, methylprednisolone or rapamycin.

The division capacity of CD4+ T cells was suppressed significantly by CyA, FK506, rapamycin and methylprednisolone (P < 0·001) (Fig. 3b).

Fig 3.

Influence of immunosuppression on T follicular helper (Tfh) cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells in vitro. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3, anti-CD28 and interleukin (IL)-12 for 48 h to induce Tfh cell differentiation with or without immunosuppressive drugs (IS). Interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-21 were analysed by intracellular cytokine staining (a) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on the culture supernatant (c). Mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of six different healthy donors are plotted. T cell division was monitored using cell trace Violet (CTV) dilution (b). Absolute values were per donor normalized to the condition without IS (‘none'), to compensate for interdonor variability. Rapa = rapamycin; MethylPred = methylprednisolone; FK506 = tacrolimus; CyA = cyclosporin A.

The frequency of IFN-γ+ (all P < 0·001) and IL-21+ (P < 0·001 for CyA and FK; P = 0·003 for methylprednisolone and rapamycin) single-positive, as well as IFN-γ+ IL-21+ double-positive (all P < 0·001) CD3+CD4+ T cells decreased under all four immunosuppressive drugs, although to a different extent, with CyA and FK506 exerting the strongest effect (Fig. 3a). These results matched the results of the cytokine secretion in culture supernatants (secreted INF-γ, all P < 0·001; secreted IL-21, P < 0·001; P = 0·002; P = 0·03; P = 0·01 for FK506, CyA, methylprednisolone and rapamycin, respectively) (Fig. 3c).

An overview of all (adjusted) P-values is given in Supporting information, Table S1.

Discussion

Humoral immune reactions can impair the long-term prognosis of solid organ transplantation. Alloantibodies and autoantibodies to organ-specific self-antigens might damage organ function because of their role in chronic graft rejection. Furthermore, the development of de-novo autoimmune diseases and allergic disorders puts a burden on solid organ transplant patients. CNI are the immunosuppressive drugs of choice after solid organ transplantation, but their direct effect on the humoral immune response is not well known. Hence, we examined the in-vitro effect of immunosuppression on differentiation and class-switching of total and naive B cells and the effect of these immunosuppressive drugs on Tfh cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells. We found that CNI do exert an effect on humoral immunity directly by suppressing naive B cells and not only indirectly via their effect on T cell help.

Tfh cells exert an important role in autoimmune disease. Increased frequencies of Tfh cells have been associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis 14–16. CNI, rapamycin and methylprednisolone inhibited Tfh cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells.

Hence, the development of autoantibodies in solid organ transplant patients does not seem to be a consequence of a direct effect of the immunosuppressive drugs on Tfh cells.

Our experiments were carried out in vitro on monocultures of either B or T cells. The in-vivo findings in solid organ transplant patients, however, can result from an overall net effect of CNI on the interplay of B cells and different T cell subsets.

In total B cells, CNI did not affect B cell proliferation, plasmablast differentiation or surface immunoglobulin expression. In naive B cells, however, CNI inhibited B cell proliferation and plasmablast differentiation. IgA was suppressed by both CNI, whereas IgE class-switching was suppressed by CyA only. These results demonstrate a direct inhibitory effect of CNI on humoral immunity alongside their influence on T cell help, as T cell help was provided in all conditions.

CyA suppressed both IgE surface expression and secretion in supernatant of naive B cells. With FK506 IgE surface expression even tended to rise, leaving IgE secretion unaffected. This might explain the reported disappearance of clinical and biological symptoms of newly acquired allergy post-transplant after a switch from a FK506 to a CyA-based immunosuppressive regimen 30. The suppression of IgE class-switching by CyA, but not by FK506, might be responsible for this observation.

Heidt et al. demonstrated that FK506, CyA and rapamycin attenuate cytokine production (including IFN-γ) of activated CD4+ T cells on mRNA level 10. In analogy with our findings, Abadja et al. described that FK506 caused a dramatic decrease of IL-21 expression, as well as a less pronounced reduction of IFN-γ expression by CD4+ T cells 12. However, no data are available on the effect of CNI on Tfh cell differentiation, which might be of relevance in view of the increased autoimmunity observed in solid organ transplant patients. We demonstrated that CNI did not have a direct stimulating effect on Tfh cell differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, the number of IL-21+ Tfh cells decreased with increasing doses of immunosuppression, which was most pronounced with CyA. An alternative that we did not study here is that CNI might affect the balance between Tfh and other T helper cells 31,32, which could hence influence humoral immunity.

Our in-vitro experiments were carried out on PBMC from adult donors. The immune system of neonates and young children is thought to be immature and more tolerogenic compared to that of adults. Naive B and T cells reflect this immature immune system more clearly. The differential effect of CNI on naive versus total B cells should therefore be taken into consideration when treating young patients, given the possibility that immunosuppressive drugs such as FK506 could exhibit a specific effect on the immature humoral immune system. This specific effect could play a role in the observation that young children are more prone to develop allergic disorders after transplantation. Indeed, de-novo-acquired food allergy is very common in children after liver transplantation and encountered rarely in the adult transplant population.

We showed that rapamycin had a strong dose-dependent inhibitory effect on B cell number and proliferation in both total and naive B cells. This effect can be explained by an inhibition of B cell cycle progression 33,34, but also by induction of B cell apoptosis 35. The potent inhibition of rapamycin on plasmablast differentiation and Ig class-switching and Ig secretion we observed, is a logical downstream effect thereof.

Despite the long-term use of glucocorticoids in B cell-dependent diseases, their effects on B cells have not been investigated intensively. B cells are still considered to be relatively ‘resistant' to glucocorticoids, although glucocorticoid receptors have been found on the B cell membrane of patients affected with rheumatoid arthritis 36. It has been shown that treatment with high doses of dexamethasone can cause a significant reduction of circulating B cell activating factor (BAFF) and its mRNA 37. BAFF, which is a member of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family, is capable of regulating B lymphocyte survival and maturation, antibody production and immunoglobulin switching 38,39. Remarkably, we observed that especially medium concentrations of methylprednisolone caused a significant increase in CD38+ plasmablast differentiation from naive B cells in vitro. This finding is new, and the mechanism is unclear. Methylprednisolone might have a stimulating effect on B cell activation, which only becomes apparent in naive B cells by lowering their threshold for activation. However, immunoglobulin secretion did not follow the rise in plasmablasts, so perhaps the development of these methylprednisolone-induced plasmablasts into functional plasma cells was impaired.

Furthermore, methylprednisolone induced IgE class-switching in low and medium concentrations in naive B cells. In analogy, Jabara et al. also showed an induction of in-vitro IgE class-switching in human purified B cells by hydrocortisone 40. A polyclonal rise in serum IgE has also been seen in vivo in patients treated with prednison. These findings, which seem to be in contrast with the clinically observed anti-allergic effects of steroid therapy, in fact support a broader anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect by suppressing cytokine production and inflammatory cell infiltration 41–43.

Conclusion

B cell proliferation, plasmablast differentiation and surface immunoglobulin expression are not affected directly by CNI in total B cells, while in naive B cells CNI inhibit these processes. This differential effect might need to be taken into consideration when treating young patients. Furthermore, CNI, as well as rapamycin and methylprednisolone, inhibit in-vitro differentiation of Tfh from naive CD4+ T cells. In view of its potent suppressive effect on B cell division, plasmablast differentiation, Ig secretion and Tfh cell differentiation, rapamycin might be an interesting candidate for the prevention and/or treatment of B cell-mediated complications after solid organ transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Dr Karim Vermaelen for use of the laboratory infrastructure and Kim Deswarte for his assistance with cell sorting. P. G., M. D. and R. De B. received grants as, respectively, senior clinical investigator, postdoctoral fellow and clinical PhD fellow by the Flemish Scientific Research Board (FWO Vlaanderen). The research was supported by a personal grant from FWO to M. D. (FWO14/KAN/019).

Disclosure

All authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web site:

Fig. S1. Isotype skewing by different cytokines in human naive B cells. Naive B cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of anti-CD40 antibody and interleukin (IL)-2 alone or IL-2 + IL-21 or IL-2 + IL-21 + trandforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 or IL-2 + IL-21 + IL-4 as indicated. Secreted immunoglobulin (IgA), IgE and IgG were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in supernatants and the mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of nine different healthy donors was plotted. Raw data are shown.

Table S1. Overview of (adjusted) P-values for all examined conditions. (Adjusted) P-values after Friedman test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test for all examined conditions (each compared to the same condition without immunosuppression). A(n) (adjusted) P-value of ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. CyA = cyclosporin A; FK = tacrolimus; MP = methylprednisolone; n.s. = non-significant; RAPA = rapamycin; SN = supernatant.

References

- Sarma NJ, Tiriveedhi V, Angaswamy N, Mohanakumar T. Role of antibodies to self-antigens in chronic allograft rejection: potential mechanism and therapeutic implications. Hum Immunol. 2012;73:1275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Hart J, Millis JM, Cronin D, Brady L. De novo hepatitis with autoimmune antibodies and atypical histology: a rare cause of late graft dysfunction after pediatric liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:664–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante-Korang A, Boyle GJ, Webber SA, Miller SA, Fricker FJ. Experience of FK506 immune suppression in pediatric heart transplantation: a study of long-term adverse effects. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:415–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber S, Tiringer K, Dehlink E, et al. Allergic sensitization in kidney-transplanted patients prevails under tacrolimus treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1125–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura N, Furuta H, Tame A, et al. Extremely high serum level of IgE during immunosuppressive therapy: paradoxical effect of cyclosporine A and tacrolimus. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;112:422–4. doi: 10.1159/000237491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho T, Tredger M, Dhawan A. Current status of immunosuppressive agents for solid organ transplantation in children. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:106–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada M, Riva S, Maggiore G, Cintorino D, Gridelli B. Pediatric liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:648–74. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed SA, Integlia MJ, Pleskow RG, et al. Tacrolimus-associated eosinophilic gastroenterocolitis in pediatric liver transplant recipients: role of potential food allergies in pathogenesis. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:730–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G, Lam E, Hung S, Martin M, Sigal N. The mechanism of action of FK-506 and cyclosporin A. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;696:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb17137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt S, Roelen DL, Eijsink C, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors affect B cell antibody responses indirectly by interfering with T cell help. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;159:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Cho M-L, Jhun JY, et al. The imbalance of T helper 17/regulatory T cells and memory B cells during the early post-transplantation period in peripheral blood of living donor liver transplantation recipients under calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression. Immunology. 2013;138:124–33. doi: 10.1111/imm.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abadja F, Atemkeng S, Alamartine E, Berthoux F, Mariat C. Impact of mycophenolic acid and tacrolimus on Th17-related immune response. Transplantation. 2011;92:396–403. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182247b5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity. 2009;30:324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Ma J, Liu Y, et al. Increased frequency of follicular helper T cells in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:943–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson N, Gatenby PA, Wilson A, et al. Expansion of circulating T cells resembling follicular helper T cells is a fixed phenotype that identifies a subset of severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:234–44. doi: 10.1002/art.25032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel S-E, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-31210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato LM, Kawamoto S, Maruya M, Fagarasan S. Gut TFH and IgA: key players for regulation of bacterial communities and immune homeostasis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:49–56. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Tangye SG, Mackay CR. T follicular helper (TFH) cells in normal and dysregulated immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:741–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser B, Schaerli P, Loetscher P. CXCR5(+) T cells: follicular homing takes center stage in T-helper-cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:250–4. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Arpin C. Germinal center development. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:111–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan IC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:117–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dullaers M, Li D, Xue Y, et al. A T cell-dependent mechanism for the induction of human mucosal homing immunoglobulin A-secreting plasmablasts. Immunity. 2009;30:120–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.008. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1553–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman RL, Lebman DA, Shrader B. Transforming growth factor beta specifically enhances IgA production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1039–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebman DA, Coffman RL. Interleukin 4 causes isotype switching to IgE in T cell-stimulated clonal B cell cultures. J Exp Med. 1988;168:853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31:158–69. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarof G, Krzysiek R, Décline J-L, Cohen J, Habes D, Jacquemin E. Management of post-liver transplant-associated IgE-mediated food allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1296–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-P, Korn LL, Gamero AM, Leonard WJ. Calcium-dependent activation of interleukin-21 gene expression in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25291–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayamada S, Takahashi H, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. Helper T cell diversity and plasticity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aagaard-Tillery KM, Jelinek DF. Inhibition of human B lymphocyte cell cycle progression and differentiation by rapamycin. Cell Immunol. 1994;156:493–507. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Readinger JA, DuBois W, et al. Constitutive reductions in mTOR alter cell size, immune cell development, and antibody production. Blood. 2011;117:1228–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt S, Roelen DL, Eijsink C, van Kooten C, Claas FHJ, Mulder A. Effects of immunosuppressive drugs on purified human B cells: evidence supporting the use of MMF and rapamycin. Transplantation. 2008;86:1292–300. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181874a36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholome B, Spies CM, Gaber T, et al. Membrane glucocorticoid receptors (mGCR) are expressed in normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and up-regulated after in vitro stimulation and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. FASEB J. 2004;18:70–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0328com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard B, Schneider P, Mauri D, Tschopp J, French LE. T cell costimulation by the TNF ligand BAFF. J Immunol. 2001;167:6225–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youinou P, Pers J-O. The late news on BAFF in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:804–6. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zen M, Canova M, Campana C, et al. The kaleidoscope of glucorticoid effects on immune system. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabara HH, Ahern DJ, Vercelli D, Geha RS. Hydrocortisone and IL-4 induce IgE isotype switching in human B cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:1557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieg G, Lack G, Harbeck RJ, Gelfand EW, Leung DY. In vivo effects of glucocorticoids on IgE production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:222–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settipane GA, Pudupakkam RK, McGowan JH. Corticosteroid effect on immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1978;62:162–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(78)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey WC, Nelson HS, Branch B, Pearlman DS. The effects of acute corticosteroid therapy for asthma on serum immunoglobulin levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1978;62:340–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(78)90134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Isotype skewing by different cytokines in human naive B cells. Naive B cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of anti-CD40 antibody and interleukin (IL)-2 alone or IL-2 + IL-21 or IL-2 + IL-21 + trandforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 or IL-2 + IL-21 + IL-4 as indicated. Secreted immunoglobulin (IgA), IgE and IgG were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in supernatants and the mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of nine different healthy donors was plotted. Raw data are shown.

Table S1. Overview of (adjusted) P-values for all examined conditions. (Adjusted) P-values after Friedman test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test for all examined conditions (each compared to the same condition without immunosuppression). A(n) (adjusted) P-value of ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. CyA = cyclosporin A; FK = tacrolimus; MP = methylprednisolone; n.s. = non-significant; RAPA = rapamycin; SN = supernatant.