Summary

The present study examined a role for GDNF in adaptations to drugs of abuse. Infusion of GDNF into the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a dopaminergic brain region important for addiction, blocks certain biochemical adaptations to chronic cocaine or morphine as well as the rewarding effects of cocaine. Conversely, responses to cocaine are enhanced in rats by intra-VTA infusion of an anti-GDNF antibody and in mice heterozygous for a null mutation in the GDNF gene. Chronic morphine or cocaine exposure decreases levels of phosphoRet, the protein kinase that mediates GDNF signaling, in the VTA. Together, these results suggest a feedback loop, whereby drugs of abuse decrease signaling through endogenous GDNF pathways in the VTA, which then increases the behavioral sensitivity to subsequent drug exposure.

Introduction

Neurotrophic factors are best studied for their role in the growth and differentiation of neurons during development. More recently, they also have been implicated in many forms of plasticity within the adult nervous system. For example, electrically and chemically induced seizures (Gall and Isackson, 1989; Zafra et al., 1991; Kokaia et al., 1993), as well as antidepressant treatments (Nibuya et al., 1995), stress (Smith et al., 1995), and opiate withdrawal (Numan et al., 1998), have been shown to regulate levels of expression of several types of neurotrophic factors in specific regions of adult brain. Induction of one factor, BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), is reported to contribute to hippocampal long-term potentiation (Griesbeck et al., 1996; Patterson et al., 1996) and to changes in dendritic sprouting in hippocampus after chronic seizures (Vaidya et al., 1999).

The ability of drugs of abuse to cause addiction can be viewed as a form of neural plasticity. Indeed, chronic drug exposure has been shown to produce profound biochemical changes in specific brain regions thought to mediate the reinforcing or addicting actions of the drugs (Nestler and Aghajanian, 1997; Pilotte, 1997). Prominent among these brain regions is the mesolimbic dopamine system, which encompasses dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain and their anterior projections to the limbic fore-brain, for example, the nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Koob et al., 1998; Wise, 1998). Interestingly, chronic exposure to any of several drugs of abuse, including cocaine, amphetamine, opiates, or alcohol, causes a series of common biochemical adaptations in the mesolimbic dopamine system (Nestler et al., 1993). This is not surprising, since drugs of abuse, despite their very different initial mechanisms of action, converge by producing common functional effects on the VTA-NAc pathway after acute exposure. In the VTA, chronic drug exposure increases levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis), specific glutamate receptor subunits (such as NMDAR1), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (an intermediate filament protein specific to glia), and decreases levels of neurofilaments (intermediate filament proteins specific to neurons) (Beitner-Johnson and Nestler, 1991; Beitner-Johnson et al., 1992, 1993; Hurd et al., 1992; Sorg et al., 1993; Vrana et al., 1993; Ortiz et al., 1995; Fitzgerald et al., 1996). In the NAc, chronic drug exposure upregulates activity of the cAMP pathway; for example, it increases levels of protein kinase A (PKA) (Terwilliger et al., 1991) and also induces stable isoforms of ΔFosB, a novel Fos-family transcription factor (Hope et al., 1994; Nye and Nestler, 1996; Pich et al., 1997). It has been possible to directly relate several of these biochemical adaptations to the behavioral plasticity associated with chronic drug administration (see Discussion).

Some of the adaptations seen in response to chronic drug exposure (for example, the reduction in neurofilaments and induction of glial filaments) are reminiscent of a state of neural insult or injury. Moreover, drug exposure is reported to cause morphological changes both in VTA dopamine neurons (Sklair-Tavron et al., 1996) and in their target neurons in the NAc (Robinson and Kolb, 1997, 1999). These observations raise the possibility that neurotrophic factors may be involved in some way in long-term responses to drug exposure. Indeed, direct infusion of BDNF or related neurotrophins into the VTA has been shown to block the ability of morphine and of cocaine to produce some of their characteristic biochemical and morphological effects in this brain region (Berhow et al., 1995, 1996; Sklair-Tavron et al., 1996). However, this pharmacological effect of exogenous BDNF must be differentiated from a possible role of endogenous neurotrophic factor pathways in mediating some of the long-term responses of the VTA-NAc to drug exposure (Nestler et al., 1996).

The major objective of the present study was to assess such a role for one particular neurotrophic factor, GDNF (glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor). We focused on GDNF for several reasons. First, GDNF enhances the survival and maintains the differentiated properties of dopaminergic neurons in cell culture and does so far more potently compared to BDNF and other neurotrophins (Lin et al., 1993). Second, GDNF dramatically enhances the survival of midbrain dopamine neurons in vivo after challenge with dopaminergic neurotoxins such as 6-hydroxydopamine or MPTP (Beck et al., 1995; Kearns and Gash, 1995). GDNF also protects animals from the behavioral deficits associated with such lesions. Strikingly, a single injection of GDNF into the midbrain can exert such protective effects for at least one month (Kearns and Gash, 1995; Winkler et al., 1996). Third, signaling proteins for GDNF, GFRα1 and the associated protein tyrosine kinase Ret, are both highly enriched in midbrain dopamine neurons (Treanor et al., 1996; Trupp et al., 1996, 1997, 1998). The binding of GDNF to its receptor complex causes the phosphorylation and activation of Ret, which then mediates the physiological effects of the neurotrophic factor.

These data led us to consider a role for endogenous GDNF systems in mediating some of the adaptive responses of VTA neurons to chronic administration of drugs of abuse. We present here several lines of evidence consistent with such a role. Infusion of GDNF into the rat VTA blocks biochemical and behavioral plasticity to chronic drug exposure, whereas infusion of an anti-GDNF antibody into the VTA enhances responsiveness to drugs of abuse. Behavioral responses to drug exposure are also enhanced in mice heterozygous for a null mutation in the gene that encodes GDNF. Finally, chronic drug exposure decreases levels of phosphorylated Ret in the rat VTA, which further establishes a link between endogenous GDNF signaling and drugs of abuse at the level of the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Results

Infusion of GDNF into the VTA: Biochemical Effects

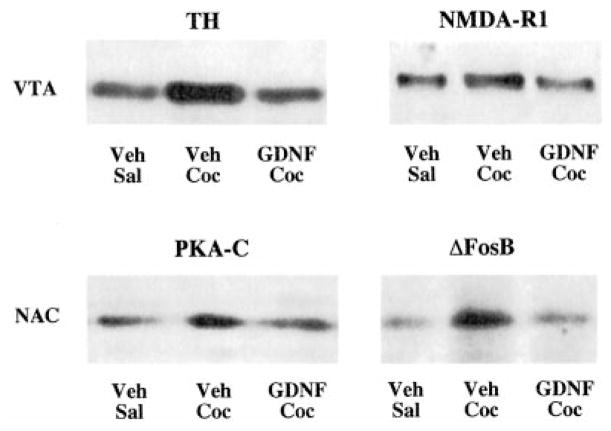

As a first step in assessing the relationship between GDNF and drugs of abuse, we examined the ability of GDNF, infused directly into the rat VTA, to modify biochemical adaptations to chronic drug exposure. GDNF was delivered by osmotic minipump (at a dose of 2.5 μg/day) through a midline cannula implanted into the VTA, and the ability of chronic cocaine or chronic morphine to produce some of their characteristic biochemical changes was assessed by Western blotting. Control animals received equivalent intra-VTA infusions of vehicle. The results of these experiments are summarized in Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2. GDNF infusion completely blocked the ability of chronic morphine and chronic cocaine to increase levels of tyrosine hydroxylase in the VTA. GDNF infusion also blocked the ability of cocaine to increase levels of the NMDAR1 glutamate receptor subunit in this brain region. (We could not assess the effect of GDNF on drug regulation of neurofilament proteins and glial fibrillary acidic protein, since surgery itself alters levels of these proteins as we reported previously [Berhow et al., 1995].) Interestingly, infusion of GDNF into the VTA also blocked the ability of chronic cocaine exposure to produce characteristic biochemical changes in the NAc, including induction of protein kinase A catalytic subunit and of the ΔFosB transcription factor (Figure 1; Table 2). GDNF infusions by themselves did not significantly alter levels of these various proteins in the VTA or NAc. In addition, animals infused with GDNF showed no untoward effects of the neurotrophic factor: their weights were equivalent to those of vehicle-injected controls, and the animals showed no gross behavioral abnormalities.

Figure 1. Western Blots Showing Blockade of Biochemical Effects of Cocaine by Intra-VTA Infusion of GDNF.

Animals received the following treatments: Veh-Sal, intra-VTA infusion of vehicle plus daily injections of saline for 7 days; Veh-Coc, intra-VTA infusion of vehicle plus daily injections of cocaine (20 mg/kg i.p.) for 7 days; GDNF-Coc, intra-VTA infusion of GDNF (2.5 μg/day) plus daily injections of cocaine for 7 days. Extracts of VTA and NAc were then subjected to Western blotting for the indicated proteins. TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; PKA-C, PKA catalytic subunit.

Table 1.

Effect of Intra-VTA Infusion of GDNF on Chronic Morphine-Induced Increases in Tyrosine Hydroxylase Immunoreactivity in the VTA

| Treatment | Vehicle + Sham | Vehicle + Morphine | GDNF + Morphine |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDNF infusions initiated before morphine administration | 100 ± 9 (8) | 136 ± 12 (8)a | 94 ± 9 (8)b |

| GDNF infusions initiated after morphine administration | 100 ± 19 (4) | 184 ± 10 (4)a | 101 ± 20 (4)b |

Vehicle + Sham, animals received intra-VTA infusions of vehicle plus implantation of sham pellets; Vehicle + Morphine, animals received intra-VTA infusions of vehicle plus implantation of morphine pellets; GDNF + Morphine, animals received intra-VTA infusions of GDNF plus implantation of morphine pellets. In the top-row experiment, intra-VTA infusion of GDNF was initiated 2 days before the start of morphine treatment and continued concurrently throughout morphine treatment; in the bottom-row experiment, infusion of GDNF was initiated 2 days after the completion of morphine treatment (see Experimental Procedures). VTA extracts were subjected to Western blotting for tyrosine hydroxylase. GDNF infusions alone had no effect on tyrosine hydroxylase levels (see Table 2). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (N) percentage of Vehicle + Sham group.

p < 0.05, compared to Vehicle + Sham, by Student’s t test.

p < 0.05, compared to Vehicle + Morphine, by Student’s t test.

Table 2.

Effect of Intra-VTA Infusion of GDNF on Biochemical Adaptations to Chronic Cocaine

| Protein | Vehicle + Saline | Vehicle + Cocaine | GDNF + Cocaine | GDNF + Saline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH (VTA) | 100 ± 11 (12) | 138 ± 7 (12)a | 79 ± 14 (12)c | 97 ± 8 (4) |

| NMDAR1 (VTA) | 100 ± 8 (8) | 143 ± 5 (8)b | 88 ± 11 (8)d | 115 ± 12 (4) |

| ΔFosB (NAc) | 100 ± 4 (12) | 147 ± 13 (12)b | 110 ± 12 (12)c | 114 ± 21 (7) |

| PKA-C (NAc) | 100 ± 19 (7) | 140 ± 13 (8)a | 92 ± 10 (8)c | 113 ± 12 (7) |

Vehicle + Saline, animals received intra-VTA infusions of vehicle plus daily injections of saline for 7 days; Vehicle + Cocaine, animals received intra-VTA infusions of vehicle plus daily injections of cocaine for 7 days; GDNF + Cocaine, animals received intra-VTA infusions of GDNF plus daily injections of cocaine for 7 days; GDNF + Saline, animals received intra-VTA infusions of GDNF plus daily injections of saline for 7 days. VTA and NAc extracts were subjected to Western blotting for the indicated proteins. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (N) percentage of Vehicle + Saline group.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.005, compared to Vehicle + Saline;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.005, compared to Vehicle + Cocaine, by Student’s t test.

Note that the small deviations from 100% seen in some of the GDNF + Saline values are not significant and within experimental error.

The ability of GDNF to attenuate biochemical adaptations to chronic drug exposure shows regional specificity. Infusion of GDNF into the nearby substantia nigra (another dopamergic nucleus that is located just lateral to the VTA) failed to have the effect of the intra-VTA infusions: cocaine’s ability to induce biochemical adaptations in the VTA was unaffected by intranigral infusions of GDNF (data not shown).

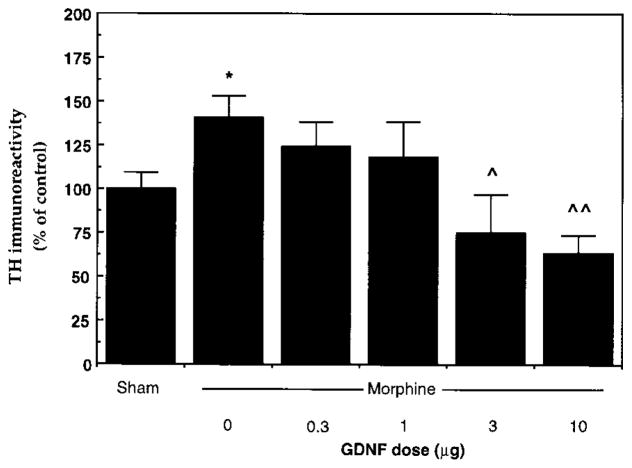

Induction of tyrosine hydroxylase is one of the most robust findings with chronic drug exposure and was, as a result, used to study the dose response to GDNF action. In this experiment, we administered GDNF via a single injection into the rat VTA, based on the reported ability of this route of administration to protect midbrain dopamine neurons from neurotoxic lesions (Kearns and Gash, 1995; Winkler et al., 1996). The results are shown in Figure 2. The lowest dose of GDNF tested, 0.3 μg, had no detectable effect on the ability of chronic morphine to induce tyrosine hydroxylase in this brain region. Moderate doses of GDNF, like the continuous infusion of the neurotrophic factor, antagonized morphine’s effect on tyrosine hydroxylase without influencing basal levels of the enzyme. Still higher doses (10 μg) decreased levels of tyrosine hydroxylase in the VTA and prevented any induction by morphine.

Figure 2. Dose Response of Blockade of Morphine-Induced Increase in Tyrosine Hydroxylase Immunoreactivity by Intra-VTA Injection of GDNF.

Sham animals received five daily implantations of sham pellets but no intra-VTA injections. All other animals received a single intra-VTA injection of GDNF (0–10 μg), followed by five daily implantations of morphine pellets. Extracts of VTA were subjected to Western blotting for tyrosine hydroxylase. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM percentage of Sham group (N = 4–12 in each treatment group). Asterisk, p < 0.05, compared to Sham; single caret, p < 0.05, double caret, p < 0.005, compared to vehicle (0 GDNF), by Student’s t test.

The experiments described above show that concomitant exposure to GDNF can prevent the ability of morphine or of cocaine to induce characteristic biochemical adaptations in the VTA-NAc pathway. It also was of interest to determine whether infusion of GDNF into the VTA could reverse biochemical adaptations already induced by prior drug exposure. As reported in Table 1, one week after cessation of chronic morphine treatment, levels of tyrosine hydroxylase remained significantly elevated in the rat VTA, consistent with the longevity of these effects demonstrated previously (Berhow et al., 1995). This persistent increase in tyrosine hyroxylase was not seen in animals that received intra-VTA infusions of GDNF, which demonstrates the ability of GDNF to reverse as well as prevent drug-induced plasticity in this brain region.

Infusion of GDNF into the VTA: Behavioral Effects

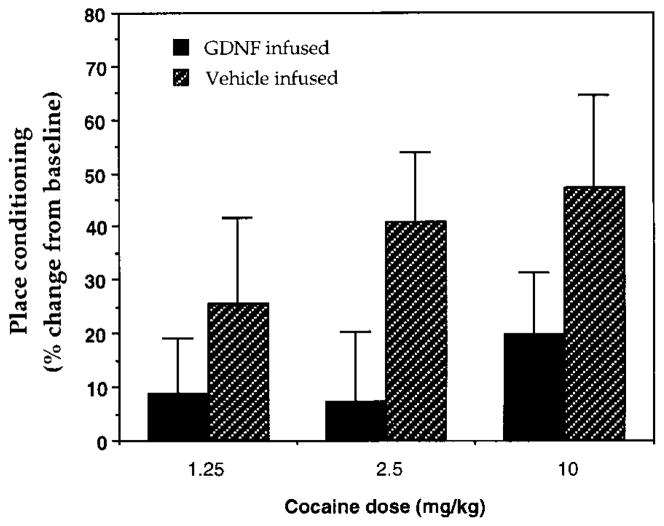

We next studied the effect of intra-VTA administration of GDNF on behavioral responses to cocaine. Rats received continuous infusions of GDNF (2.5 μg/day) into the VTA via osmotic minipump as in the biochemical experiments and were tested in a place-conditioning paradigm, in which animals learn to associate an environment paired with drug exposure. Place conditioning is, therefore, considered a measure of the rewarding properties of a drug. Figure 3 shows the effect of GDNF on place conditioning to cocaine. In both GDNF- and vehicle-infused animals, cocaine established place preferences in a dose-dependent manner. However, GDNF-infused animals showed reduced preferences at all doses studied, indicating that GDNF reduces an animal’s sensitivity to the rewarding activity of cocaine.

Figure 3. Effect of Intra-VTA Infusion of GDNF on Place Conditioning to Cocaine.

Animals received intra-VTA infusions of vehicle or GDNF and were trained for conditioned place preference with various doses of cocaine (1.25–10 mg/kg). Data are reported as the mean percentage change in time spent on the drug-paired side ± SEM, which provides a measure of place conditioning (see Experimental Procedures) (N = 8–12 in each treatment group). Neither the GDNF- nor the vehicle-infused groups had a baseline preference for either side of the apparatus before conditioning. GDNF-infused animals displayed a significantly reduced level of place conditioning to cocaine over this entire dose range (p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA).

Infusion of Anti-GDNF Antibody into the VTA: Biochemical and Behavioral Effects

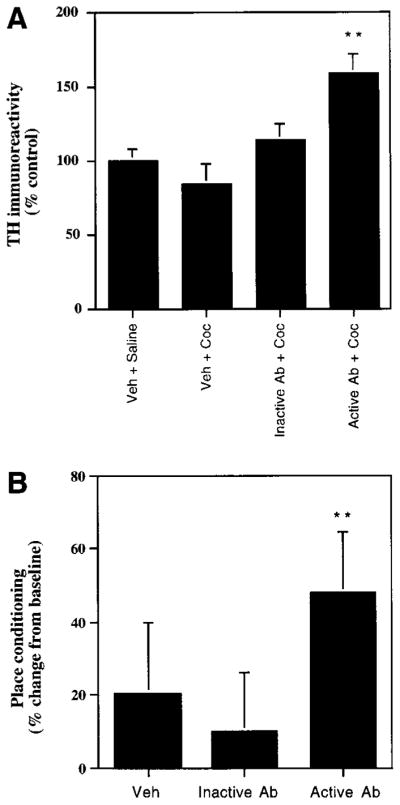

The results obtained with intra-VTA infusions of GDNF showed that exogenous GDNF can modify the biochemical and behavioral responses to chronic drug exposure. To determine whether endogenous GDNF is normally involved in drug-induced plasticity, we infused an anti-GDNF antibody into the rat VTA via osmotic minipump. This antibody (termed “active” antibody) was raised against a moiety of GDNF that is required for binding to its receptor and has been shown to block the physiological activity of GDNF in vitro (Xu et al., 1998). As a control, we infused a second anti-GDNF antibody (termed “inactive” antibody), which was raised against a moiety of GDNF that is not involved in receptor binding and does not block the physiological activity of GDNF. The two antibodies, in contrast, are equivalent in their ability to recognize GDNF in immunoassays. Vehicle was infused as a further control. Infusion of active antibody increased the sensitivity of the animal to biochemical effects of systemic drug exposure: chronic administration of a low dose of cocaine (5 mg/kg), which failed to induce tyrosine hydroxylase in animals that received intra-VTA infusion of vehicle, significantly increased levels of the enzyme in the VTA of animals infused with the active antibody (Figure 4A). In contrast, this low dose of cocaine had no effect on tyrosine hydroxylase levels in animals treated with the inactive antibody. Neither antibody altered levels of tyrosine hydroxylase in the VTA in the absence of cocaine exposure (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effect of Intra-VTA Infusion of Anti-GDNF Antibody on Biochemical and Behavioral Responses to Cocaine.

(A) Veh-Sal, animals received intra-VTA infusion of vehicle plus daily injections of saline for 5 days; Veh-Coc, animals received intra-VTA infusion of vehicle plus daily injections of cocaine (5 mg/kg i.p.) for 5 days; inactive Ab-Coc, animals received intra-VTA infusions of an anti-GDNF antibody that does not prevent GDNF from binding to its receptor (Ab 1531; see Experimental Procedures) plus daily injections of cocaine for 5 days; and active Ab-Coc, animals received intra-VTA infusions of an anti-GDNF antibody (Ab G90) that does prevent GDNF from binding to its receptor plus daily injections of cocaine for 5 days. Extracts of VTA were subjected to Western blotting for tyrosine hydroxylase. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM percentage of Veh-Sal group (N = 8 in each treatment group). Double asterisk, p < 0.01, compared to three other treatments, by Student’s t test.

(B) Animals received intra-VTA infusion of vehicle, inactive anti-GDNF antibody, or active anti-GDNF antibody and were trained for conditioned place preference to a threshold dose of cocaine (2.5 mg/kg). Data are reported as the mean percentage change in time spent on the drug-paired side ± SEM, which provides a measure of place conditioning (see Experimental Procedures) (N = 8 in each treatment group). Neither the vehicle- nor antibody-infused groups had a baseline preference for either side of the apparatus before conditioning. Double asterisk, p < 0.01, compared to vehicle and inactive antibody, by Student’s t test.

Infusion of the active anti-GDNF antibody similarly increased an animal’s sensitivity to the behavioral effects of cocaine in the place-conditioning paradigm. Intra-VTA infusion of active antibody enabled a threshold dose of cocaine to establish a significant place preference, whereas animals that received intra-VTA infusions of inactive antibody or of vehicle showed no effect (Figure 4B).

GDNF Knockout Mice: Behavioral and Biochemical Effects

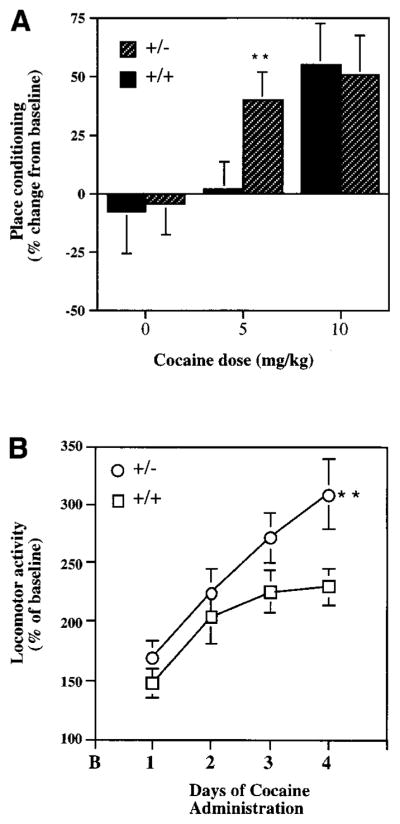

As a complementary way to examine the influence of endogenous GDNF pathways on drug responsiveness, we studied behavioral responses to cocaine in GDNF knockout mice. Since homozygote knockouts die shortly after birth from renal complications (Moore et al., 1996; Pichel et al., 1996; Sanchez et al., 1996), we used heterozygote knockouts that appear normal and do not show this lethality. Wild-type littermates were used as controls. The mice were studied first in a place-conditioning paradigm. As shown in Figure 5A, cocaine established place preferences in wild-type mice in a dose-dependent manner, with significant preferences seen at a higher dose of cocaine (10 mg/kg), but not at a lower dose (5 mg/kg). In contrast, GDNF knockout mice developed high levels of place conditioning to both doses. These results indicate greater responsiveness of the knockouts to the rewarding effects of cocaine.

Figure 5. Behavioral Responses to Cocaine in GDNF Knockout Mice.

(A) Heterozygote GDNF knockout mice (+/−) and their wild-type littermates (+/+) were trained for conditioned place preference to cocaine (0–10 mg/kg i.p.). Data are reported as the mean percentage change in time spent on the drug-paired side, which provides a measure of place conditioning (see Experimental Procedures) (N = 8–12 in each treatment group). Neither the wild-type nor the knockout mice had a baseline preference for either side of the apparatus before condtioning. Double asterisk, p < 0.05, compared to wild type.

(B) Locomotor activity of heterozygote GDNF knockout mice (+/−) and their wild-type littermates (+/+) to four daily cocaine injections (10 mg/kg i.p.). Data are expressed as mean percentage change from baseline locomotor activity (B) ± SEM (N = 8–12 in each treatment group). Double asterisk, p < 0.01, compared to wild type, by Student’s t test.

Mice were studied next in a locomotor activity paradigm. Wild-type and GDNF knockout mice did not differ in their locomotor response when first placed in the locomotor chamber, and they showed equivalent habituation in locomotor activity after repeated exposures to the chamber (data not shown). As shown in Figure 5B, wild-type and knockout mice also showed equivalent locomotor activation in response to the initial injection of cocaine. However, GDNF knockout mice showed significantly greater increases in locomotor activity following repeated exposures to cocaine, a phenomenon termed locomotor sensitization.

GDNF knockout mice also exhibited biochemical differences, compared to their wild-type littermates, in the mesolimbic dopamine system. The knockouts showed dramatically elevated levels of ΔFosB in the NAc (289 ± 10% of wild type; N = 8; p < 0.01 by Student’s t test), although levels of tyrosine hydroxylase and of NMDAR1 immunoreactivity in the VTA were equivalent to those seen in wild-type mice (data not shown).

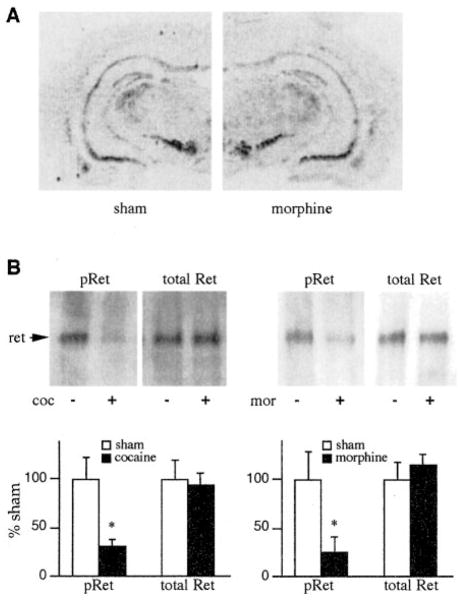

Drug Regulation of the GDNF Signaling Pathway in the Mesolimbic Dopamine System

To determine whether chronic drug exposure alters the expression of GDNF or its receptor complex, we measured levels of GDNF, GFRα1, and Ret mRNA in the mesolimbic dopamine system by in situ hybridization. Previous work has shown that GDNF is expressed at moderate levels in NAc and related striatal regions, with no detectable GDNF mRNA seen in the VTA (Trupp et al., 1997). Conversely, GFRα1 and Ret are enriched in the VTA and not detectable in the NAc (Treanor et al., 1996; Trupp et al., 1996, 1997). Analysis of drug-naive rats confirmed this distribution pattern for these mRNAs (e.g., see Figure 6A for GFRα1). Moreover, it was found that chronic administration of morphine or of cocaine did not significantly alter levels of mRNA expression of GDNF in the NAc, or of GFRα1 or Ret in the VTA. Chronic morphine or cocaine administration also failed to alter levels of Ret immunoreactivity in the VTA as determined by Western blotting (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of Chronic Drug Exposure on GDNF Receptor Components in the VTA.

(A) Autoradiograms showing lack of effect of chronic morphine treatment on levels of GFRα1 mRNA in the VTA. Levels of GFRα1 mRNA were determined by in situ hybridization in sham-treated and chronic morphine-treated rats. The figure is representative of six animals studied in each treatment group.

(B) Autoradiograms showing the ability of chronic cocaine (coc) or chronic morphine (mor) treatment to decrease levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Ret (pRet) in the VTA as determined by Western blotting, with no effect seen on levels of total Ret immunoreactivity. Data are expressed as mean percentage of sham ± SEM (N = 6–7). Asterisk, p < 0.05 by Student’s t test.

However, the lack of drug-induced alterations in steady-state levels of expression of GDNF and its receptor components in the mesolimbic dopamine system does not provide an adequate measure of whether drug exposure alters the functional activity of the GDNF pathway within this neural pathway. To address this question directly, we developed an assay (described in Experimental Procedures) to quantitate levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Ret in the VTA. It is well-established that such phosphorylation of Ret is stimulated upon GDNF binding to the GFRα1-Ret complex and that this phosphorylation results in activation of Ret, which then mediates subsequent physiological actions of GDNF (Treanor et al., 1996; Trupp et al., 1996, 1998). As a result, levels of phosphoRet provide a functional measure of signaling via GDNF and related factors. By use of this assay, we found that chronic administration of cocaine or of morphine caused a robust decrease in levels of phosphoRet by 65% and 72%, respectively, in the rat VTA (Figure 6B). In contrast, no effect was seen in the nearby substantia nigra after chronic cocaine (phosphoRet, 93% ± 23% of sham ± SEM; total Ret, 96% ± 19% of sham; N = 6–7) or chronic morphine (data not shown).

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that exogenous GDNF, administered directly into the rat VTA, blunts both biochemical and behavioral adaptations to repeated administration of drugs of abuse. The study also establishes that endogenous GDNF systems are required for normal biochemical and behavioral responses to drug exposure: infusion of anti-GDNF antibody directly into the VTA increases a rat’s sensitivity to drug effects, and mice that lack one copy of the GDNF gene show a similar increase in drug sensitivity. This is a particularly important observation because it extends what we know about the role of GDNF in the regulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission. Thus, research to date has only shown the pharmacological ability of exogenously applied GDNF to protect dopamine neurons in the adult brain in vivo from neurotoxic injury (see Introduction). The results of the present study implicate endogenous GDNF systems in regulating the function of adult dopamine neurons, in particular, regulating their responses to drugs of abuse. Moreover, based on our findings that chronic drug exposure decreases the phosphorylation of the GDNF signaling protein Ret in the VTA, we hypothesize further that some of the long-term effects of morphine and cocaine on the mesolimbic dopamine system are achieved via perturbation of endogenous GDNF signaling pathways.

The ability of exogenous GDNF to blunt the biochemical and behavioral responses to drug exposure is consistent with recent evidence for the role played by certain of these biochemical responses in animal models of addiction. Increased expression of ΔFosB in the NAc has been shown to increase a mouse’s sensitivity to the rewarding and locomotor-activating effects of cocaine (Kelz et al., 1999). By blocking this induction of ΔFosB, GDNF would be expected to blunt increased behavioral responsiveness as well. Conversely, the enhanced sensitivity of GDNF knockout mice to cocaine could be explained by their elevated basal levels of ΔFosB in the NAc. A similar case can be made for protein kinase A: activation of the protein kinase, specifically in the NAc, has been shown to increase locomotor responses to cocaine and amphetamine (Cunningham and Kelley, 1993; Miserendino and Nestler, 1995), as well as the rewarding properties of amphetamine in the conditioned reinforcement paradigm (Kelley and Holahan, 1997). However, activation of the protein kinase in the NAc also has been shown to decrease the rewarding properties of cocaine in the drug self-administration paradigm (Self et al., 1998). As a result, it is difficult to conclude definitively what contribution to GDNF’s behavioral effects are mediated via blockade of the protein kinase A upregulation in this brain region. The behavioral consequences of GDNF’s ability to block the drug-induced biochemical adaptations in the VTA (e.g., induction of tyrosine hydroxylase and NMDAR1) remain unknown, since these adaptations have not yet been related directly to behavioral plasticity. Nevertheless, the fact that GDNF blocks behavioral responses to drug exposure means that the net effect of the neurotrophic factor must involve biochemical changes that oppose drug action.

The contrast between the effects of GDNF and BDNF on actions of drugs of abuse is interesting. Intra-VTA infusions of BDNF, like those of GDNF, in rats block some of the biochemical adaptations to morphine and cocaine, for example, induction of tyrosine hydroxylase in the VTA and of protein kinase A in the NAc (Berhow et al., 1995). Yet, a recent study showed that BDNF dramatically augments an animal’s responses to the locomotor and rewarding properties of cocaine (Horger et al., 1999). Such augmented behavioral responses would make sense if the biochemical adaptations blocked by BDNF are homeostatic; that is, they serve to reduce further drug effects. Presumably, these findings indicate that the net effect of BDNF, in contrast to that of GDNF, involves biochemical changes that increase behavioral responses to drug exposure. Consistent with this inter-pretation is the finding that BDNF knockout mice, in contrast to GDNF knockout mice, show reduced behavioral plasticity to repeated cocaine administration (Horger et al., 1999). The biochemical endpoints examined in the present study and in the earlier studies of BDNF likely represent only a small portion of the adaptations that chronic drug administration causes in the VTA and NAc. Therefore, a major goal of future research is to further characterize the influence of GDNF and BDNF on the mesolimbic dopamine system, with the objective of finding differences in the molecular and cellular actions of the two neurotrophic factors that explain their opposite behavioral effects.

The observations that GDNF produces its effects on the mesolimbic dopamine system upon local infusion into the VTA but not into the nearby substantia nigra and that the GDNF signaling proteins (GFRα1 and Ret) are enriched in VTA dopamine neurons (Trupp et al., 1997) are consistent with the possibility that GDNF is acting directly on these neurons. This hypothesis is supported further by our observation that infusion of anti-GDNF antibody into the VTA, which does not diffuse outside of this brain region (see Experimental Procedures), produces effects opposite to that of locally-applied GDNF. This hypothesis would then suggest that the ability of GDNF to modify drug-induced adaptations (e.g., induction of ΔFosB, protein kinase A) in the NAc, which itself appears to lack GFRα1 and Ret, occurs indirectly via the neurotrophic factor’s actions in the VTA. This is consistent with the evidence that induction of ΔFosB in the NAc in response to chronic cocaine administration can be blocked by a dopamine receptor antagonist (Nye et al., 1995).

A major question raised by the present study emerges: what are the mechanisms by which GDNF opposes biochemical adaptations to chronic morphine or chronic cocaine exposure? The fact that GDNF exerts these effects with two structurally divergent drugs makes it highly unlikely that an idiosyncratic chemical interaction between GDNF and drug is involved. The postreceptor signaling pathways by which GDNF produces its physiological effects remain poorly understood. It is known that GDNF produces its effects through GFRα1 and the protein tyrosine kinase Ret. However, subsequent steps in this signaling pathway have not been established. Similarly, the mechanisms by which chronic exposure to a drug of abuse causes the observed biochemical changes in the VTA (e.g., adaptations in tyrosine hydroxylase, NMDAR1, and neural and glial filaments) are unknown. It will be interesting in future studies to identify the precise molecular steps at which cross-talk between drug-regulated and GDNF-regulated signaling pathways converge. The mechanisms of convergence may be quite complex. For example, chronic morphine and cocaine appear to increase levels of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the VTA via a posttranscriptional mechanism (Boundy et al., 1998), whereas GDNF, at least at higher doses, appears to decrease tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription in this brain region (Messer et al., 1999). This action of GDNF provides one plausible mechanism, at the molecular level, by which such cross-talk between GDNF and drugs of abuse may occur.

The findings that GDNF blocks the drug-induced upregulation of tyrosine hydroxylase in the VTA and blocks behavioral responses to drugs of abuse may seem surprising given that GDNF is generally believed to enhance, rather than oppose, the dopaminergic phenotype. However, direct measures of the effect of GDNF on dopamine levels in the substantia nigra and striatum have yielded mixed results. For example, in lesion studies GDNF rescues toxin-induced decreases in tyrosine hydroxylase and tissue dopamine levels and in cell culture enhances the survival of dopamine neurons (e.g., see Gash et al., 1996, 1998; Winkler et al., 1996; Hebert and Gerhardt, 1997; Akerud et al., 1999). On the other hand, in normal rats GDNF is reported to decrease tyrosine hydroxylase expression (Lu and Hagg, 1997) and striatal dopamine content (Gash et al., 1998). Moreover, no prior information is available for the VTA. Indeed, our recent finding that GDNF inhibits tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription in the VTA (Boundy et al., 1998) shows quite clearly that GDNF’s effects on the VTA are more complex than simply “increasing the dopaminergic phenotype.” Although speculative, one way to reconcile our findings with GDNF’s ability to support the survival of dopamine neurons is that GDNF might promote a program of gene expression that supports homeostatic or reparative processes in the neurons at the expense of proteins (like tyrosine hydroxylase) that reflect the neurons’ highly differentiated state (see Cheah and Geffen, 1973; Grafstein, 1975).

One of the most important aspects of the present study is the evidence for a role of endogenous GDNF systems in drug action. We show that disruption of endogenous GDNF (via anti-GDNF antibody or a genetic knockout of GDNF) augments drug responsiveness. We also show that while chronic drug exposure does not alter levels of expression of GDNF, GFRα1, or Ret in the mesolimbic dopamine system, it does cause a dramatic decrease in GDNF signaling as evidenced by a 65%–70% reduction in levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Ret in the VTA. Such phosphorylation of Ret is known to reflect its state of activation and to mediate the physiological effects of GDNF and GFRα1 (Treanor et al., 1996; Trupp et al., 1996). Taken together, these findings support the scheme that the drug-induced decrease in GDNF signaling in the VTA removes a homeostatic feedback (or counteracting) mechanism on this neural pathway and thereby contributes to sensitized biochemical and behavioral responses to drugs of abuse. It will be interesting in future studies to determine the precise mechanism by which chronic drug administration decreases phosphoRet levels specifically within this brain region.

To conclude, the results of the present study establish a functional interaction between GDNF and drugs of abuse at the level of the mesolimbic dopamine system. The findings highlight the complex types of mechanisms that are likely induced in the brain by chronic exposure to a drug of abuse. The involvement of GDNF and perhaps other neurotrophic factor systems in drug-induced neural and behavioral plasticity could be particularly important for the very long-lived changes in brain function associated with addiction. These results also raise the interesting possibility that medications targeted to GDNF or to its signaling pathway could be useful as novel treatment agents for addictive disorders in humans.

Experimental Procedures

Intra-VTA Surgery

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (CAMM, Wayne, NJ), weighing 250–300 g at the start of the experiment, were used in this study. GDNF (Amgen) infusion or infusion of an anti-GDNF antibody (see below; Amgen) involved the implantation of osmotic minipumps (Alzet), which provide a constant infusion rate of 0.5 μl/hr for up to 10 days, connected to a midline intra-VTA cannula (Berhow et al., 1995). GDNF or anti-GDNF antibody was delivered in a vehicle solution consisting of 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 0.9% NaCl, and 1% bovine serum albumin.

The GDNF concentration in the minipump was calculated to result in a delivery of 2.5 μg GDNF per day. This dose was chosen for two reasons. First, this dose was on the low end of doses of GDNF that have been shown to be effective at preventing the degeneration of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons after a neurotoxic lesion (Lu and Hagg, 1997). Second, this dose was also near the low end of the dose range of other neurotrophic factors that have been shown to be biochemically and behaviorally active when administered into the VTA (Berhow et al., 1995, 1996).

Two anti-GDNF antibodies were used in this study: G90 (Amgen), which is known to block GDNF action in vitro, and 1531 (Amgen), which does not block anti-GDNF action in vitro (Xu et al., 1998). However, the two antibodies are equivalent in terms of their ability to detect GDNF in immunoassays. The antibodies were loaded into minipumps at a concentration sufficient to yield a delivery of 240 ng of antibody per day. Immunohistochemical staining of brains after such antibody infusions demonstrated no detectable diffusion of the antibodies beyond the injected area (VTA).

The implantation surgery technique used for this study is described elsewhere (Berhow et al., 1995). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital supplemented with atropine (0.25 ml/kg) and implanted with an osmotic pump connector cannula (28G cannula, 22G connector; Plastic Products Company). The coordinates used were for the midline of the VTA (AP −5.3 mm, DV 8.4 mm). In one experiment, cannulae were placed in the substantia nigra with the following coordinates: AP −5.3 mm, DV 7.2 mm, and ML ± 3.0 mm. Osmotic pumps were placed subcutaneously between the scapulae and connected to the cannula with PE60 tubing (Clay Adams). The tubing was secured at both ends by Loc-Tite, and the cannula was sealed in place using dental cement mounted to four skull screws. After the cement dried, animals were sutured, treated with antiseptic, and left under observation on a heating pad until they revived.

In some experiments, GDNF (0.3–10 μg) was administered directly into the VTA as a single injection via a Hamilton syringe. The GDNF was administered in a volume of 0.5 μl over 10 min. The injection site was the same as that used for the implantation procedure.

Chronic Drug Treatments

Cocaine hydrochloride (National Institute on Drug Abuse) was administered by i.p. injection in saline; control animals received saline injections. Morphine was administered by subcutaneous implantation of pellets (containing 75 mg of morphine base; National Institute on Drug Abuse) to rats under light halothane anesthesia daily for 5 days. Control animals received sham surgery. These treatment regimens are based on previous studies, where they have been shown to produce characteristic biochemical adaptations in the VTA-NAc (Berhow et al., 1995; Fitzgerald et al., 1996).

In all cocaine experiments, animals underwent surgery for implantation of intra-VTA cannula on day 1. Intra-VTA infusions of vehicle or GDNF were initiated at this time. Cocaine injections were initiated the day after surgery and were given daily for 5–7 days. For biochemical experiments, animals were used either 6 or 16 hr after the last cocaine injection. In all morphine experiments, unless stated otherwise, animals underwent surgery for initiation of intra-VTA infusions or injections on day 1. Morphine pellets were implanted daily for 5 days beginning on day 3. The animals were used the day after the last pellet implantation. In some experiments, animals first received chronic morphine treatment as described above. Two days after the last pellet implantation, the animals underwent surgery for initiation of intra-VTA infusions. The animals were used 7 days later.

Western Blotting

Immunolabeling of tyrosine hydroxylase and ΔFosB (Hiroi et al., 1997), NMDAR-1 (Fitzgerald et al., 1996), and PKA-catalytic subunit (Lane-Ladd et al., 1997) were performed as described elsewhere. Briefly, brains were removed rapidly from decapitated rats and chilled in ice-cold physiological buffer. For rats, VTA and NAc were obtained from coronal brain slices using either a 15G syringe needle (for all VTA punches and for NAc punches used to analyze PKA) or a 12G syringe needle (for all other NAc punches). For mice, VTA and NAc punches were obtained by use of a 16G and 15G syringe needle, respectively. Brain samples were homogenized in 1% SDS. Protein determinations were made using the method of Lowry. Between 5 μg and 50 μg of protein were loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels and subjected to electrophoresis.

The following antibodies were used: a rabbit anti-FRA (Fos-related antigen) antibody for ΔFosB (1:4,000, M. J. Iadarola, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD); a rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (1:10,000, EugeneTech, Allendale, NJ); a rabbit anti-NMDAR1 antibody (1:5,000, S. F. Heinemann, La Jolla, CA); a rabbit anti-protein kinase A-Cα antibody (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), which recognizes both the α and β forms of the catalytic subunit (Lane-Ladd et al., 1997); and a goat anti-Ret antibody (1 μg/ml, antibody C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Proteins were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgG (1:2,000, Vector, Burlingame, CA) followed by chemiluminescence (Dupont NEN, Boston, MA). Equal loading and transfer of proteins was confirmed by the following: (1) all blots were stained with amido black; (2) levels of several other proteins (e.g., neurofilament proteins, glial fibrillary acidic protein) were not altered by the drug and GDNF treatments used; and (3) the same blots used to measure proteins that are drug regulated (e.g., tyrosine hydroxylase) were also used to measure levels of these other proteins that were not drug regulated. Levels of immunoreactivity were quantified on a Macintosh-based image analysis system and were linear over at least a 3-fold range of tissue concentration used. Levels of protein in experimental samples were compared with those of controls; statistical analyses were performed by use of a Student’s t test.

Assay for PhosphoRet

Given the lack of availability of phospho-specific anti-Ret antibodies that are suitable for brain extracts, we developed an alternative method to assay levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Ret. Like many protein tyrosine kinases that function as transmembrane receptors, Ret expression is relatively low in brain and difficult to measure in crude extracts without an initial partial purification step. Since Ret has been shown to undergo N-linked glycosylation (Takahashi et al., 1991), we used binding to immobilized lectin for this initial purification, as we have done previously for other receptor tyrosine kinases (Wolf et al., 1999). Binding of Ret to several lectins was assessed by incubating VTA extracts with lectin-biotin conjugates and precipitating the bound proteins with avidin-agarose beads (Lectin Kit I, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and then probing the bound and unbound proteins by Western blotting with an anti-Ret antibody (see above). Wheat germ agglutinin was found to precipitate a protein recognized by this antibody with an approximate Mr of 190 kDa and to completely remove the corresponding prominent band from the supernatant. This technique was confirmed by quantitatively purifying Ret from SH-SY5Y cells, a cell line known to express Ret. Ret-enriched extracts were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody followed by immunoblotting for Ret to obtain a final measure of tyrosine-phosphorylated Ret in brain samples.

VTA and substantia nigra punch dissections were obtained from control and morphine-treated rats as described above, except that the dissection buffer contained 1 mM NaVO4, an inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Frozen punches were sonicated in a buffer containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaVO4, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride. Aliquots of brain samples (containing 150 μg of protein) were diluted 10-fold with sonication buffer with 2% Triton X-100 instead of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Forty microliters of wheat germ agglutinin-sepharose CL4B beads (Sigma) were added to each sample and incubated for 4 hr at 4°C. Resulting pellets were washed extensively with ice-cold Triton-X 100 buffer. Glycosylated proteins were then eluted in 250 μl of the Triton-X 100 buffer containing 0.3 M N-acetylglucosamine and omitting the sodium pyrophosphate. Two micrograms of anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY20, BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) was added to each eluate, and the mixtures were incubated overnight at 4°C. The antibody complexes were precipitated using Protein G-sepharose beads. Pellets were washed extensively with Triton X-100 buffer without sodium pyrophosphate and then subjected to Western blotting with the anti-Ret antibody described above except that ECL-plus (Amersham) was used for chemiluminescent detection.

Several controls were performed to validate this assay. Ret was not detectable in supernatants of wheat germ agglutinin–treated samples, which confirms complete recovery of Ret by this method. Ret was also not detectable in samples precipitated by wheat germ agglutinin in the presence of N-acetylglucosamine (which competes for glycosylated proteins) nor in samples immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody in the presence of p-nitrophenylphosphate (a phosphotyrosine analog). No additional Ret could be precipitated with a second anti-phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitation step, which confirms complete recovery of phosphoRet by this method. Aliquots of the same brain samples analyzed for phosphoRet were also assayed for levels of total Ret immunoreactivity. Finally, intra-VTA infusion of GDNF was found (3 hr postinfusion) to consistently increase levels of phosphoRet within this brain region compared to vehicle-infused animals (202% ± 10% of vehicle ± SEM; N = 3).

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed exactly as described by Messer et al. (1999) on rats treated chronically with morphine or cocaine (see above). Oligonucleotide probes were used for detection of GDNF, GFRα1, and Ret according to published protocols (Treanor et al., 1996; Trupp et al., 1996, 1997). For detection of GDNF, a 50-mer was used: 5′-CCT GCA ACA TGC CTG GCC TAC CTT GTC ACT TGT TAG CCT TCT ACT TCG AG-3′. For detection of GFRα1, a 49-mer was used: 5′-CTT AGT GTG CGG TAC TTG GTG CTG CAG CTC TGT TCC TTC AGG CAC TGA T-3′. For detection of Ret, a 50-mer was used: 5′-TTG GGA CAA AGG AAC TGC ACG GGT AAC ATG TGG AAG TGG TAG AAG GTG CC-3′.

Behavioral Testing

Place conditioning was carried exactly as described in a three-chamber apparatus consisting of a smaller middle chamber joined to two larger side chambers (Carlezon et al., 1997). The larger chambers differed in lighting conditions, floor texture, and the orientation of striped patterns on their walls. On day 0, animals were allowed to explore the three chambers freely for 30 min; the time spent in each side was recorded as baseline. Animals that spent over 18 min in either of the side chambers during this baseline run were excluded from the study; this comprised less than 5% of all animals tested. Among the animals included in the study, there was no group preference for either of the side chambers.

For experiments on rats, baseline measures were obtained on day 1, and immediately thereafter the animals underwent intracranial surgery (to implant infusion cannulae). The animals were allowed to recover for the next three days (days 2–4). Days 5 and 6 were training days. On each of these days, the rats received two separate 30 min conditioning trials. Rats first received a saline injection (1 ml/kg) and were confined to one of the side chambers. Three hours later, the rats received an injection of cocaine and confined to the other side of the chamber. On day 7, the animals were allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus, and the time spent in each side was again recorded. This procedure has been shown to produce reliable measures of place conditioning (Carlezon et al., 1997).

For experiments on mice, animals were allowed to explore the open chamber for baseline measurements. Days 2–7 were training days. On days 2, 4, and 6, mice received a saline injection and were confined to one of the side chambers. On days 3, 5, and 7, mice received an injection of cocaine and confined to the other side of the chamber.

On day 8, the animals were allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus, and the time spent in each side was again recorded. This procedure has been shown to produce reliable measures of place conditioning in mice (Hiroi et al., 1997).

Place-conditioning data are reported as the percent change in time spent on the drug-paired side. This is calculated by comparing the amount of time each animal spent in the drug-paired chamber before and after conditioning.

Locomotor activity and sensitization in mice were measured exactly as described (Hiroi et al., 1997). Briefly, mice were tested at the same time each day. The locomotor activity chamber was a plastic cage (28 × 17 × 12 cm) with ten pairs of photocell beams, which divided the box into eleven rectangular fields. Horizontal movement was counted as locomotor activitiy. For the first 3 days (habituation), mice were placed into the chambers immediately after saline injections and locomotor activity was measured for 10 min. From days 4–7, mice were given cocaine injections and placed in the chambers for 10 min. This short time was used because it avoids the complications of stereotypy (Hiroi et al., 1997). Baseline activity for each animal was taken as the average of the second and third habituation days. Data are reported as the percent of activity of this baseline.

GDNF +/− Mice

The generation of GDNF knockout mice has been described elsewhere (Pichel et al., 1996). GDNF−/− mice die within 1–2 days of birth, but GDNF+/− mice are viable, normal in size, and indistinguishable grossly from their wild-type littermates. Therefore, such heterozygote GDNF knockout mice were used in this study. Mice were bred on a C57BL/6J background and used at about 12 weeks of age. Wild-type littermates were used as controls. All studies were carried out on male animals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the Abraham Ribicoff Research Facilities of the Connecticut Mental Health Center, State of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

References

- Akerud P, Alberch J, Eketjall S, Wagner J, Arenas E. Differential effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and neurturin on developing and adult substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. J Neurochem. 1999;73:70–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Valverde J, Alexi T, Poulsen K, Moffat B, Vandlen R, Rosenthal A, Hefti F. Mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons protected by GDNF from axotomy-induced degeneration in the adult brain. Nature. 1995;373:339–341. doi: 10.1038/373339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Nestler EJ. Morphine and cocaine exert common Chronic actions on tyrosine hydroxylase in dopaminergic brain reward regions. J Neurochem. 1991;57:344–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Guitart X, Nestler EJ. Neurofilament proteins and the mesolimbic dopamine system: common regulation by chronic morphine and chronic cocaine in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2165–2176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02165.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Guitart X, Nestler EJ. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and the mesolimbic dopamine system: regulation by chronic morphine and Lewis-Fischer strain differences in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1766–1773. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhow MT, Russell DS, Terwilliger RZ, Beitner-Johnson D, Self DW, Lindsay RM, Nestler EJ. Influence of neurotrophic factors on morphine- and cocaine-induced biochemical changes in the mesolimbic dopamine system. J Neurosci. 1995;68:969–979. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00207-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhow MT, Hiroi N, Nestler EJ. Regulation of ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinase), part of the neurotrophin signal transduction cascade, in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system by chronic exposure to morphine or cocaine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4707–4715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04707.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boundy VA, Gold SJ, Messer CJ, Chen JS, Son JH, Joh TH, Nestler EJ. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase promoter activity by chronic morphine in TH9.0-LacZ transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9989–9995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09989.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Boundy VA, Haile CN, Lane SB, Kalb RG, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sensitization to morphine induced by viral-mediated gene transfer. Science. 1997;277:812–814. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah TB, Geffen LB. Effects of axonal injury on norepinephrine tyrosine hydroxylase and monoamine oxidase levels in sympathetic ganglia. J Neurobiol. 1973;4:443–452. doi: 10.1002/neu.480040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ST, Kelley AE. Hyperactivity and sensitization to psychomotor stimulants following cholera toxin infusion into the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2342–2350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02342.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald LW, Ortiz J, Hamedani AG, Nestler EJ. Drugs of abuse and stress increase the expression of GluR1 and NMDAR1 glutamate receptor subunits in the rat ventral tegmental area: common adaptations among cross-sensitizing agent. J Neurosci. 1996;16:274–282. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall CM, Isackson PJ. Limbic seizures increase neuronal production of messenger RNA for nerve growth factor. Science. 1989;245:758–761. doi: 10.1126/science.2549634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gash DM, Zhang Z, Ovadia A, Cass WA, Yi A, Simmerman L, Russell D, Martin D, Lapchak P, Collins F, et al. Functional recovery in parkinsonian monkeys treated with GDNF. Nature. 1996;380:252–255. doi: 10.1038/380252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gash D, Gerhardt GA, Hoffer BJ. Effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on the nigrostriatal dopamine system in rodents and nonhuman primates. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:911–915. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafstein B. The cell body response to axotomy. Exp Neurol. 1975;48:32–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbeck O, Korte M, Staiger V, Gravel C, Carroll P, Bonhoeffer T, Thoenen H. Combination of gene targeting and gene transfer by adenoviral vectors in the analysis of neurotrophin-mediated neuronal plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MA, Gerhardt GA. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intranigral administration of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on aged Fischer 344 rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:760–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi N, Brown JR, Haile CN, Ye H, Greenberg ME, Nestler EJ. FosB mutant nice: loss of chronic cocaine induction of Fos-related proteins and heightened sensitivity to cocaine’s psychomotor and rewarding effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10397–10402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Nye HE, Kelz MB, Self D, Iadorola MJ, Nakabeppu Y, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Induction of a long-lasting AP-1 complex composed of altered Fos-like proteins in brain by chronic cocaine and other chronic treatments. Neuron. 1994;13:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Lindefors N, Brodin E, Brene S, Persson H, Ungerstedt U, Hokfelt T. Amphetamine regulation of mesolimbic dopamine/cholecystokinin neurotransmission. Brain Res. 1992;578:317–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90264-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horger BA, Iyasere CA, Berhow MT, Messer CJ, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR. Enhancement of locomotor activity and conditioned reward to cocaine by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4110–4122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04110.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CM, Gash DM. GDNF protects nigral dopamine neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine in vivo. Brain Res. 1995;672:104–111. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01366-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Holahan MR. Enhanced reward-related responding following cholera toxin infusion into the nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 1997;26:46–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199705)26:1<46::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Chen JS, Carlezon WA, Whistler K, Gilden L, Beckmann AM, Steffen C, Zhang YJ, Marotti L, Self SW, Tkatch R, et al. Induction of the transcription factor ΔFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401:272–276. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokaia Z, Gido G, Ringstedt T, Bengzon J, Kokaia M, Persson H, Lindvall O. Rapid increase of BDNF mRNA levels in cortical neurons following spreading depression: regulation by glutamatergic mechanisms independent of seizure activity. Mol Brain Res. 1993;19:277–286. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90126-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane-Ladd SB, Pineda J, Boundy VA, Pfeiffer T, Krupinski J, Aghajanian GK, Nestler EJ. CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) in the locus coeruleus: biochemical, physiological, and behavioral evidence for a role in opiate dependence. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7890–7891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07890.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, Bektesh S, Collins F. GDNF: a glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Hagg T. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor prevents death, but not reductions in tyrosine hydroxylase, of injured nigrostriatal neurons in adult rats. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:484–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer CJ, Son JH, Joh TH, Beck KD, Nestler EJ. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription in ventral midbrain by glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Synapse. 1999;34:241–243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19991201)34:3<241::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miserendino MJ, Nestler EJ. Behavioral sensitization to cocaine: modulation by the cyclic AMP system in the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1995;674:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00030-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MW, Klein RD, Farinas I, Sauer H, Armanini M, Phillips H, Reichardt LF, Ryan AM, Carver-Moore K, Rosenthal A. Renal and neuronal abnormalities in mice lacking GDNF. Nature. 1996;382:76–79. doi: 10.1038/382076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular basis of addiction. Science. 1997;278:58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug addiction: a model for the molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Berhow MT, Brodkin ES. Molecular mechanisms of drug addiction: adaptations in signal transduction pathways. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:190–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HE, Nestler EJ. Induction of chronic Fos-related antigens in rat brain by chronic morphine administration. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:636–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HE, Hope BT, Kelz MB, Iadarola M, Nestler EJ. Pharmacological studies of the regulation of chronic Fos-related antigen induction by cocaine in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Pharm Exper Ther. 1995;275:1671–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressent drug treatments. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7539–7548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan S, Lane-Ladd SB, Zhang L, Lundgren KH, Russell DS, Seroogy KB, Nestler EJ. Differential regulation of neurotrophic and Trk receptor mRNAs in catecholaminergic nuclei during chronic opiate treatment and withdrawal. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10700–10708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10700.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J, Fitzgerald LW, Charlton M, Lane S, Trevisan L, Guitart X, Shoemaker W, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Biochemical actions of chronic ethanol exposure in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Synapse. 1995;21:289–298. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson SL, Abel T, Deuel TA, Martin KC, Rose JC, Kandel ER. Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission in hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;16:1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich EM, Pagliusi SR, Tessaru M, Talabot-Ayer D, Hooft can Huijsduijnen R, Chiamulera C. Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science. 1997;275:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichel JG, Shen L, Sheng HZ, Granholm AC, Drago J, Grinberg A, Lee EJ, Huang SP, Saarma M, Hoffer BJ, et al. Defects in enteric innervation and kidney development in mice lacking GDNF. Nature. 1996;382:73–76. doi: 10.1038/382073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotte NS. Neurochemistry of cocaine withdrawal. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:534–538. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199712000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Persistent structural modifications in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex neurons produced by previous experience with amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8491–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08491.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Morphine alters the structure of neurons in the nucleus accumbens and neocortex of rats. Synapse. 1999;33:160–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199908)33:2<160::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MP, Silos-Santiago I, Frisen J, He B, Lira SA, Barbacid M. Renal agenesis and the absence of enteric neurons in mice lacking GDNF. Nature. 1996;382:70–73. doi: 10.1038/382070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Genova LM, Hope BT, Barnhart WJ, Spencer JJ, Nestler EJ. Involvement of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the nucleus accumbens in cocaine self-administration and relapse of cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1848–1859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01848.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklair-Tavron L, Wei-Xing S, Lane SB, Harris HW, Bunney BJ, Nestler EJ. Chronic morphine induces visible changes in the morphology of mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11202–11207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM. Stress and glucocorticoids affect the expression of brain-dervied neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1768–1777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01768.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg BA, Chen SY, Kalivas PW. Time course of tyrosine hydroxylase expression after behavioral sensitization to cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:424–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Buma Y, Taniguchi M. Identification of the ret proto-oncogene products in neuroblastoma and leukemia cells. Oncogene. 1991;6:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger RZ, Beitner-Johnson D, Sevarino KA, Crain M, Nestler EJ. A general role for adaptations in G-proteins and the cyclic AMP system in mediating the chronic actions of morphine and cocaine on neuronal function. Brain Res. 1991;548:100–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91111-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treanor JS, Goodman L, de Sauvage F, Stone DM, Poulsen KT, Beck KD, Gray C, Armanini MP, Pollock RA, Hefti F, et al. Characterization of a multicomponent receptor for GDNF. Nature. 1996;382:80–83. doi: 10.1038/382080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trupp M, Arenas E, Fainzilber M, Nilsson A, Sieber B, Grigoriou M, Kilkenny C, Salazaar-Grueso E, Pachnis V, Arumae U, et al. Functional receptor for GDNF encoded by the c-Ret proto-oncogene. Nature. 1996;381:785–788. doi: 10.1038/381785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trupp M, Belluardo N, Funakoshi I, Ibanez CF. Complementary and overlapping expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), c-ret proto-oncogene, and GDNF rceptor-apha indicates multiple mechanisms of trophic action in the adult rat CNS. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3554–3567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trupp M, Raynoschek C, Belluardo N, Ibanez CF. Multiple GPI-anchored receptors control GDNF-dependent and independent activation of the c-Ret receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;11:47–63. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya VA, Siuciak JA, Du F, Duman RS. Hippocampal mossy fiber sprouting induced by chronic electroconvulsive seizures. Neuroscience. 1999;89:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana SL, Vrana KE, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Chronic cocaine administration increases CNS tyrosine hydroxolase enzyme activity and mRNA levels and tryptophan hydroxylase enzyme activity levels. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2262–2268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C, Sauer H, Lee CS, Bjorkland A. Short-term GDNF tTreatment provides long-term rescue of lesioned nigral dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7206–7215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DH, Numan S, Nestler EJ, Russell DS. Regulation of phospholipase Cγ in the mesolimbic dopamine system by chronic morphine administration. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1520–1528. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RY, Pong K, Yu Y, Chang D, Liu S, Lile JD, Treanor J, Beck KD, Louis J. Characterization of two distinct monoclonal antibodies specific for glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1383–1393. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafra F, Castren E, Thoenen H, Lindholm D. Interplay between glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid transmitter systems in the physiological regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic fctor and nerve Growth factor synthesis in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]