Abstract

Objective

The authors sought to clarify the sources of parent-offspring resemblance for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior, using a novel genetic-epidemiological design.

Method

Using national registries, the authors identified rates of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in 41,360 Swedish individuals born between 1960 and 1990 and raised in triparental families comprising a biological mother who reared them, a “not-lived-with” biological father, and a stepfather.

Results

When each syndrome was examined individually, hazard rates for drug abuse in offspring of parents with drug abuse were highest for mothers (2.80, 95% CI=2.23–3.38), intermediate for not-lived-with fathers (2.45,95%CI=2.14–2.79), and lowest for stepfathers (1.99, 95% CI=1.55–2.56). The same pattern was seen for alcohol use disorders (2.23, 95% CI=1.93–2.58; 1.84, 95% CI=1.69–2.00; and 1.27, 95% CI=1.12–1.43) and criminal behavior (1.55, 95% CI=1.44–1.66; 1.46, 95%CI=1.40–1.52; and1.30, 95% CI=1.23–1.37). When all three syndromes were examined together, specificity of cross-generational transmission was highest for mothers, intermediate for not-lived-with fathers, and lowest for stepfathers. Analyses of intact families and other not-lived-with parents and stepparents showed similar cross-generation transmission for these syndromes in mothers and fathers, supporting the representativeness of results from triparental families.

Conclusions

A major strength of the triparental design is its inclusion, within a single family, of parents who provide, to a first approximation, their offspring with genes plus rearing, genes only, and rearing only. For drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior, the results of this study suggest that parent-offspring transmission involves both genetic and environmental processes, with genetic factors being somewhat more important. These results should be interpreted in the context of the strengths and limitations of national registry data.

Because of the wide accessibility of twin samples (1), psychiatric genetic epidemiology has, over recent decades, focused on clarifying the contributions of genetic and environmental factors to the familial aggregation of disorders within generations. Adoption designs, the primary approach to delineating sources of transmission across generations, are more difficult to implement. After a series of influential adoption studies in schizophrenia and alcoholism from the 1960s through the 1980s (e.g., 2–5), this method has since been less frequently utilized (with some noteworthy exceptions, e.g., 6, 7). While adoption designs are elegant, they are becoming rarer, and most adoption samples have several methodological limitations, including nonrandom placement of adoptees, missing information on many biological fathers, and unrepresentative adoptive parents (8).

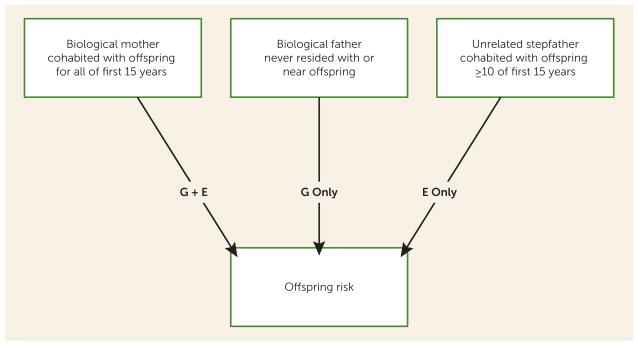

In this article, we present a new design, triparental families, which examines cross-generational transmission and which addresses several of the limitations of adoption studies. In these families, every offspring has one biological parent who rears them, one “not-lived-with” biological parent with whom they have had minimal contact, and one stepparent (Figure 1). To a first approximation, these three parents provide their offspring with, respectively, “genes plus rearing,” “genes only,” and “rearing only.”

FIGURE 1. A Schematic Description of the Triparental Family Designa.

aTriparental families contain three parents. The biological mother who raises the child contributes both genes (G) and rearing environment (E) to the offspring. The biological or not-lived-with father never resides with or near the offspring and therefore contributes, as a first approximation, only genes (G) to the offspring. The stepfather, who is not biologically related to the offspring, contributes only rearing environment (E).

We apply this design in a nationwide Swedish sample to three externalizing syndromes ascertained from official registries: drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. These syndromes are of particular interest because of previous evidence of complex familial transmission involving both genetic and environmental processes (5, 9–11).

Finally, previous twin studies have suggested that, within generations, externalizing syndromes share a substantial proportion of their genetic risk (12–15). We examine, within the triparental design, the degree of sharing of genetic and environmental risk factors for the cross-generational transmission of these syndromes.

METHOD

As outlined previously for drug abuse (16), alcohol use disorders (17), and criminal behavior (18), we used linked data from multiple Swedish nationwide registries and health care data. Linking was achieved via the unique individual 10-digit personal identification number assigned at birth or immigration to all Swedish residents. To preserve confidentiality, this identification number was replaced by a serial number. The following sources were used in our database: the Total Population Register, containing annual data on family and geographical status; the Multi-Generation Register, providing information on family relationships; the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register, containing all hospitalizations for all Swedish inhabitants from 1964 through 2010; the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, containing all prescriptions in Sweden picked up by patients from 2005 through 2010; the Outpatient Care Register, containing information from all outpatient clinics from 2001 through 2010; the Primary Health Care Register, containing outpatient diagnoses from 2001 through 2007 for 1 million patients from Stockholm and middle Sweden; the Swedish Crime Register, containing national data on all convictions from 1973 through 2011; the Swedish Suspicion Register, containing national data on all individuals strongly suspected of crime from 1998 through 2011; the Swedish Mortality Register, containing all causes of death; and the Population and Housing Censuses, which provided information on household and geographical status in 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, and 1985. We secured ethical approval for this study from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University.

Drug abuse was identified in the Swedish medical and mortality registries by ICD codes (ICD-8: drug dependence [304]; ICD-9: drug-induced psychoses [292] and drug dependence [304]; ICD-10: mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use [F10–F19], except those due to alcohol [F10] or tobacco [F17]); in the Suspicion Register, which records arrests by codes 3070 (driving under the influence of drugs), 5010 (drug possession), 5011 (drug use), and 5012 (possession and use), which reflect crimes related to drug abuse; and in the Crime Register, which reflects convictions by references to laws covering narcotics (law 1968: 64, paragraph 1, point 6) and drug-related driving offenses (law 1951:649, paragraph 4, subsection 2 and paragraph 4A, subsection 2). Drug abuse was identified in individuals (excluding cancer patients) in the Prescribed Drug Register who had filled prescriptions of hypnotics and sedatives (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] Classification System N05C and N05BA) or opioids (ATC: N02A) in dosages consistent with drug abuse, that is, on average more than four defined daily doses a day for 12 months.

Criminal behavior was identified by registration in the Swedish Crime register, which excluded convictions for minor crimes like traffic infractions. Otherwise, our measure of criminal behavior utilized all available criminal conviction types.

Alcohol use disorders were identified in the Swedish medical and mortality registries by ICD codes (ICD-9 codes V79B, 305A, 357F, 571A-D, 425F, 535D, 291, 303, 980; ICD-10 codes E244, G312, G621, G721, I426, K292, K70, K852, K860, O354, T51, F10); in the Crime Register by codes 3005, 3201, which reflect crimes related to alcohol abuse; in the Suspicion Register by codes 0004 and 0005 (only those individuals with at least two alcohol-related crimes or suspicion of crimes from both the Crime Register and the Suspicion Register were included); and in the Prescribed Drug Register by prescriptions for disulfiram (ATC: N07BB01), acamprosate (N07BB03), or naltrexone (N07BB04).

Sample

Among all individuals born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990 (N=3,257,987), we selected those who, from ages 0 though 15, resided all 15 years in the same household as their mother, never resided in the same household or small geographical area (see below) as their biological father, and resided for ≥10 years in the same household as their stepfather (N=41,360, 1.26%).

Household was ascertained as follows: From 1960 to 1985 (every fifth year), we used the household identification number from the Population and Housing Census. The household identification number includes all individuals living in the same dwelling. For the years we did not have data, we approximated the household identification number with the available information from the year closest in time. From 1986 onward (every year), we used the family identification number from the Total Population Register. Family identification numbers are assigned to individuals who are related or married and who are registered as residing at the same property (each individual can be part of only one family). In addition, adults who are registered at the same property and have children together but are not married are registered as being in the same family.

Geographical status was defined in terms of Small Areas for Market Statistics (SAMS), which are small geographical units defined by Statistics Sweden, the Swedish government statistics bureau. There are approximately 9,200 SAMS throughout Sweden, with an average population of around 1,000. From 1960 to 1970, we had no information on SAMS areas, and therefore we used parishes as a proxy for SAMS for these years. The parishes serve as districts for the Swedish census and elections and have approximately the same number of inhabitants as SAMS are as. From 1960 to 1985, we only had information for every fifth year, and for that reason we approximated the geographical status with the information from the year closest in time.

A stepfather was defined as a man 18 to 50 years older than the offspring, living in the same household as the offspring, and not related to the offspring as an uncle, grandfather, cousin, brother, or half-brother. From 1986 onward, for an offspring living with his or her mother, we capture the stepfather only if he is married to the offspring’s mother or had a child together with that mother. Forty-five percent of our sample was born between 1960 and 1970, and 18% between 1980 and 1990. The not-lived-with status arose in only a small minority of cases (2.5%) through death of the father in the year of the child’s birth.

We used Cox proportional hazard models to investigate the future risk for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in offspring as a function of presence of drug abuse, alcohol used is orders, and criminal behavior in the three types of parents (mother, not-lived-with father, and stepfather). Robust standard errors were used to adjust the 95% confidence intervals, as some full-sibling pairs (N=759) were included in the analysis. Follow-up time (in years) was measured from age 15 of the offspring until year of first registration for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, or criminal behavior or until death, emigration, or end of follow-up (year 2011), whichever came first. In all models, we investigated the proportionality assumption. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (19).

RESULTS

We identified 41,360 individuals born between 1960 and 1990 and raised in triparental families. Table 1 lists the rates of registration for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in the offspring, the mother, the not-lived-with father, and the stepfather in these families as well as in relevant comparable samples. Mothers, offspring, and not-lived-with fathers from triparental families had rates of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior that were, respectively, modestly, moderately, and substantially higher than population averages. Rates of these syndromes in stepfathers were similar to those in the general population.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behavior in Members of the Triparental Families and Relevant Comparison Groups

| Family Member or Group | Prevalence (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Abuse | Alcohol Use Disorders | Criminal Behavior | |

| Relatives in triparental families | |||

| Offspring | 5.8 | 6.1 | 21.1 |

| Mother | 1.9 | 3.6 | 7.2 |

| Not-lived-with father | 5.4 | 19.5 | 32.7 |

| Stepfather | 1.3 | 8.3 | 16.9 |

| Relevant comparison groups | |||

| Offspring generation | 3.6 | 3.1 | 12.4 |

| Parental generation, females | 1.3 | 2.5 | 5.0 |

| Parental generation, males | 1.8 | 7.8 | 13.5 |

| Adoptive fathers | 0.4 | 3.0 | 3.9 |

The correlations between drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in the three parental types in our tri-parental families are listed in Table 2. These correlations are generally modest (≤~0.20) between mothers and not-lived-with fathers and between not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers, and somewhat higher (0.25 to 0.37) between mothers and stepfathers.

TABLE 2.

Tetrachoric Correlations for Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behavior Between Mothers, Not-Lived-With Fathers, and Stepfathers in the Triparental Families

| Parental Pair | Tetrachoric Correlation Between Parents for These Syndromes

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Abuse

|

Alcohol Use Disorders

|

Criminal Behavior

|

||||

| Correlation | SE | Correlation | SE | Correlation | SE | |

| Mother and not-lived-with father | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| Mother and stepfather | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.01 |

| Not-lived-with father and stepfather | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 |

Proportional Hazard Models: Single Syndromes

We first predicted the hazard ratio for drug abuse in offspring from the history of drug abuse in mothers, not-lived-with fathers, and stepfathers and then repeated parallel analyses for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior (Table 3). For drug abuse, the hazard ratios were significant for all three parents and were highest for mothers, next highest for not-lived-with fathers, and lowest for stepfathers. The hazard ratio for mothers did not differ significantly from that for not-lived-with fathers but was significantly higher than that for stepfathers. The hazard ratio for not-lived-with fathers was higher than that for stepfathers, although the difference fell short of significance.

TABLE 3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Models Predicting Hazard Ratios For Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behaviors From the History of Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behaviors in Each of the Three Parents of the Triparental Familiesa

| Parent | Syndrome in Parents and Offspring

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Abuse

|

Alcohol Use Disorders

|

Criminal Behavior

|

||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Mother | 2.80 | 2.23, 3.38 | 2.23 | 1.93, 2.58 | 1.55 | 1.44, 1.66 |

| Not-lived-with father | 2.45 | 2.14, 2.79 | 1.84 | 1.69, 2.00 | 1.46 | 1.40, 1.52 |

| Stepfather | 1.99 | 1.55, 2.56 | 1.27 | 1.12, 2.43 | 1.30 | 1.23, 1.37 |

The p values (one-tailed) for mother versus not-lived-with father for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior, respectively, were 0.13, 0.01, and 0.07; for mother versus stepfather, 0.01, <0.0001, and <0.0001; and for not-lived-with father versus stepfather, 0.08, <0.0001, and 0.0003.

The magnitude of hazard ratios across the three parents in the triparental family for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior were also in the following order: mother > not-lived-with father > stepfather. For alcohol use disorders, all three of the hazard ratios differed significantly from each other, while for criminal behavior one of the three (mother versus not-lived-with father) fell short of significance.

Proportional Hazard Models: Within and Across Syndromes

We then predicted risks for individual syndromes from nine predictor variables: the presence of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in each of the three parents (Table 4). Drug abuse was most strongly predicted by a history of drug abuse in the mother, criminal behavior in the not-lived-with father, and criminal behavior in the stepfather. Alcohol use disorders were most strongly predicted by an alcohol use disorder in the mother, an alcohol used is order in the not-lived-with father, and criminal behavior in the stepfather. Criminal behavior was most strongly predicted by criminal behavior in the mother, criminal behavior in the not-lived-with father, and criminal behavior in the stepfather.

TABLE 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Models Predicting Hazard Ratios for Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behaviors From the History of Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behaviors Examined All Together in the Three Parents of the Triparental Familiesa

| Parent and Parental History | Outcome in Offspring

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Abuse

|

Alcohol Use Disorders

|

Criminal Behavior

|

||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Mother | ||||||

| Drug abuse | 1.93 | 1.58, 2.37 | 1.17 | 0.93, 1.48 | 1.19 | 1.04, 1.36 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 1.42 | 1.20, 1.69 | 1.87 | 1.60, 2.20 | 1.36 | 1.23, 1.50 |

| Criminal behavior | 1.71 | 1.51, 1.95 | 1.71 | 1.51, 1.94 | 1.45 | 1.35, 1.56 |

| Not-lived-with father | ||||||

| Drug abuse | 1.55 | 1.34, 1.79 | 1.21 | 1.05, 1.41 | 1.14 | 1.05, 1.25 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 1.20 | 1.08, 1.32 | 1.47 | 1.33, 1.62 | 1.10 | 1.04, 1.17 |

| Criminal behavior | 1.73 | 1.58, 1.89 | 1.44 | 1.32, 1.57 | 1.39 | 1.32, 1.45 |

| Stepfather | ||||||

| Drug abuse | 1.35 | 1.04, 1.76 | 1.29 | 0.97, 1.70 | 1.21 | 1.04, 1.41 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.99 | 0.87, 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.93, 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.07, 1.23 |

| Criminal behavior | 1.58 | 1.43, 1.75 | 1.29 | 1.16, 1.43 | 1.23 | 1.17, 1.30 |

Entries in boldface predict the same syndrome in parent and offspring. Entries in italics indicate the strongest predictor of the syndrome within that parental type.

Examined from another perspective, each syndrome was transmitted from mother to offspring with at least moderate specificity, in that the highest hazard ratio was always highest from the same syndrome in parents and offspring. The specificity of the transmission from not-lived-with fathers was less pronounced, as in one of the three syndromes (drug abuse), offspring risk was predicted more strongly by another syndrome in the parent—criminal behavior. Finally, in stepfathers, the nonspecificity of parent-offspring transmission was more pronounced. For all three of the syndromes, the risk was highest in the offspring of stepfathers with criminal behavior.

DISCUSSION

Our first goal in this study was to introduce the triparental design, which we see as having five major strengths. First, it is the only design that can compare within the same family the three paradigmatic kinds of parent-child relationships: a biological parent who raises the child (genes plus rearing), a not-lived-with biological parent who has limited contact with the child (genes only), and an unrelated stepparent who raises the child (rearing only). The not-lived-with parents and stepparents are analogous to the biological and adoptive parents in an adoption design.

A second advantage of this design is the relative frequency of triparental families. In Sweden, offspring from triparental families are more than twice as common as adoptees. Third, the legal and confidentiality concerns that surround adoptions and which outside of Scandinavia have substantially hindered adoption research do not apply to triparental families. Fourth, the triparental design could readily be analyzed by structural equation modeling to obtain quantitative estimates of genetic and environmental transmission on a liability scale rather than the epidemiological approach we took here, which utilized hazard ratios (20).

Finally, an important methodological concern about the validity of adoption studies is the a typicality of adoptive parents (8). In Sweden as elsewhere, they are selected for low rates of psychopathology and high levels of income and education (21). The reduced level and variation of environmental adversity in adoptive homes might result in an underestimation of rearing effects. Compared with adoptive parents, stepfathers in triparental families are much more representative of the general population in Sweden with respect to their rates of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior (Table 1). This should result in more generalizable estimates of the importance of rearing effects from triparental family studies than would be possible from adoption designs.

However, the triparental design has one noteworthy limitation: the only common triparental family configuration in Sweden includes a biological mother raising her own child, a not-lived-with father, and a stepfather. For the study period, we could identify only 2,151 triparental families with a biological father who raised the child plus a not-lived-with mother and a stepmother, a sample too small to yield estimates with adequate precision for our rare outcomes. Could our triparental design be biased by including only mothers who were both genetically and environmentally related to their children and only not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers? For example, if intrauterine effects were important, we would expect parent-offspring resemblance for externalizing syndromes to be stronger in both biological/rearing mothers and not-lived-with mothers than would be seen in fathers. Or, if females required a higher liability than males to express externalizing disorders, this would predict a higher risk for these syndromes in biological offspring of affected mothers than of affected fathers.

We were able to address these questions empirically. Table 5 compares the association between drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in parents and offspring (Table 5) in intact families and in not-lived-with parents and step parents who were not part of our trip a rental family sample. Contrary to the pattern predicted for intrauterine effects or for a higher genetic liability in affected women than in affected men, of the six comparisons of biological parents, three were stronger from fathers and three from mothers. For biological/ rearing parents from intact families, parent-offspring resemblances were very similar for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior, and for drug abuse, they were modestly stronger for fathers. Our inclusion of only biological/rearing mothers in our triparental sample is unlikely to result in substantial biases. Furthermore, none of the comparisons of the strength of parent-offspring transmission were significantly different in not-lived-with mothers compared with fathers or in stepmothers compared with stepfathers. These results indicate that our findings from not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers in our triparental families are probably representative of not-lived-with parents and stepparents more generally.

TABLE 5.

Parent-Offspring Associations Between Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behavior as Measured by Hazard Ratios in Mothers Compared With Fathers From Intact Families, in Not-Lived-With Mothers Compared With Fathers, and in Stepmothers Compared With Fathers

| Parent | Outcome in Offspring

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Abuse

|

Alcohol Use Disorders

|

Criminal Behavior

|

||||

| Hazard Ratio or p | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio or p | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio or p | 95% CI | |

| Mother from intact family (N=2,111,074) | 3.28 | 3.05, 3.52 | 2.53 | 2.41, 2.66 | 1.91 | 1.87, 1.95 |

| Father from intact family (N=2,111,074) | 3.77 | 3.51, 4.06 | 2.41 | 2.33, 2.49 | 1.97 | 1.94, 2.00 |

| Heterogeneity test | p=0.008 | p=0.11 | p=0.02 | |||

| Not-lived-with mother (N=10,194) | 2.70 | 2.23, 3.26 | 1.90 | 1.60, 2.25 | 1.58 | 1.45, 1.72 |

| Not-lived-with father (N=113,761) | 2.72 | 2.58, 2.88 | 1.81 | 1.73, 1.89 | 1.50 | 1.46, 1.53 |

| Heterogeneity test | p=0.94 | p=0.59 | p=0.24 | |||

| Stepmother (N=18,359) | 1.68 | 1.12, 2.52 | 1.36 | 1.18, 1.57 | 1.35 | 1.28, 1.43 |

| Stepfather (N=65,803) | 1.74 | 1.43, 2.16 | 1.22 | 1.10, 1.35 | 1.27 | 1.22, 1.33 |

| Heterogeneity test | p=0.87 | p=0.23 | p=0.10 | |||

Another limitation of the triparental family design is that the information needed to identify such families may not be available in many countries. However, there should be no legal barriers to studying them, as is often the case with adoptions.

The triparental family is not the only design outside of classical adoption and twin studies that can distinguish between “nature” and “nurture.” Studies of siblings and half-siblings can be useful, but like twin studies, they clarify sources of horizontal (or within-generation) transmission (22). By contrast, samples of twins and their parents (23) or of twins and their children (24) can, like adoption and the triparental samples, elucidate the genetic and environmental contributions to vertical (or cross-generational) transmission (25).

Our second goal in this study was to utilize the tri-parental family design to further clarify the nature of the cross-generational transmission of three paradigmatic externalizing syndromes: drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. We showed, as expected, that the risks for each of the externalizing syndromes were positively correlated among the three parental figures. Since our goal was to quantify the unique relationship between each parental type and the offspring, all of our statistical analyses controlled for these background correlations. As shown in the key analyses (Table 3), offspring risk for each syndrome was strongly and significantly predicted by a history of that syndrome in the mother, in the not-lived-with father, and in the stepfather. For all three syndromes, the magnitude of the hazard ratios had the same order: mother > not-lived-with father > stepfather. However, these results do not exhaust the information contained in the triparental design; the role of genetic factors can also be inferred from the relative strength of the prediction of offspring risk from mothers (genes plus rearing) compared with stepfathers (rearing only). For all three syndromes, the hazard ratio from mothers is appreciably and significantly higher than that seen from stepfathers, thus providing independent evidence for the role of genetic factors in parent-offspring transmission. The importance of rearing effects can also be inferred from the relative strengths of risk prediction from mothers (genes plus rearing) compared with not-lived-with fathers (genes only). Here the differences are all in the expected direction but are modest and statistically significant only for alcohol use disorders, and approach significance for criminal behavior. In aggregate, our results provide strong and consistent support for the etiological importance of both genetic and environmental factors in the parent-to-offspring transmission of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. They also suggest with similar consistency that genetic factors are more important than rearing-environmental factors in this transmission.

It is of particular interest to compare these results with our previous classical Swedish adoption studies of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior (16–18). Congruent with our present findings, risks for each of these three syndromes in adoptees were predicted by a history of the same syndrome in adoptive and in biological parents (16–18). All of these relationships were statistically significant except in adoptive parents of adoptees with drug abuse (16). Furthermore, consistent with our findings, the association with adoptee outcomes was stronger in biological than in adoptive parents (16–18). Using two independent samples with entirely different designs, we have been able to replicate our key insights into the sources of the parent-offspring resemblance for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior.

We previously compared parent-offspring resemblance for drug abuse and criminal behavior in intact families and distinct families containing not-lived-with parents and stepparents (26,27). Our results were qualitatively similar to those obtained here with triparental families. The main limitation of this previous approach was the much higher rates of externalizing disorders in both the parents and offspring of the not-lived-with families and stepfamilies compared with the intact families. Thus, in sharp contrast to the triparental design, examining transmission of externalizing syndromes in such different family types was not comparing like with like.

Our third goal in this study was to explore the specificity of the cross-generational transmission of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. Focusing on the not-lived-with fathers, where parent-offspring resemblance results only from genetic factors, we see clear evidence for non specificity in that each syndrome in not-lived-with fathers was associated with a significantly increased risk for all three syndromes in offspring (Table 4). However, consistent with some specificity in transmission, for two of our three syndromes (alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior), the hazard ratios for within-syndrome parent-offspring transmission (i.e., alcohol use disorders → alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior → criminal behavior) were considerably stronger than for cross-syndrome transmissions. Examining stepparents, where parent-offspring resemblance results only from environmental processes, we see more evidence for nonspecificity of transmission. Having a stepfather with criminal behavior is associated with the greatest increased risk for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior.

Results from stepparents are particularly informative about the degree to which the environmental parent-offspring transmission for externalizing disorders is direct or indirect. Transmission would be direct if drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior were primarily “taught” by parents to their children like language or religion, or learned by children from observing parental behaviors (28–31). Alternatively, externalizing disorders could be transmitted across generations indirectly. Parental drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior often interfere with effective parenting, and they increase the risk for parental divorce, premature death, and lowered socioeconomic status, all of which can predispose offspring to externalizing disorders (29, 32–37). Our results are consistent with predominantly indirect parent-offspring environmental transmission for drug abuse and alcohol use disorders that are most strongly predicted by criminal behavior in the stepfather. By contrast, our findings support a mechanism of direct transmission for criminal behavior, as offspring criminal behavior was also most strongly predicted by criminal behavior in the stepfather.

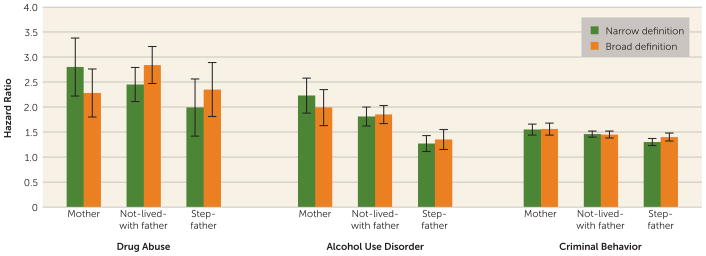

Our definitions of stepfathers and not-lived-with fathers were made as narrow as feasibly possible. It was therefore of interest to examine a more broadly defined group of trip a rental families based on rearing biological mothers and not-lived-with fathers who resided with or near their offspring for less than 2 years and stepfathers who were present for 8–10 of the offspring’s first 15 years (N=33,987). In Figure 2, we compare results from hazard ratio analyses in these “broadly” defined and our original “narrowly” defined triparental families. The results are very similar for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior. For drug abuse, in the broadly defined compared with the narrowly defined triparental families, the hazard ratios are modestly greater for not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers and lower for biological mothers. These results provide further evidence for the validity of our findings and suggest that useful information is available about parent-offspring transmission in triparental families that are less narrowly defined than those primarily examined in this study.

FIGURE 2. Comparison of Hazard Ratios for the Prediction of Drug Abuse, Alcohol Use Disorders, and Criminal Behavior in Offspring From Biological Mothers, Not-Lived-With Fathers, and Stepfathers With the Same Syndromes, in the Narrowly Defined Triparental Families Examined in This Study and More Broadly Defined Triparental Familiesa.

aSee the Discussion section for details. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of four potentially important methodological limitations. First, our data are from Sweden and may or may not extrapolate to other populations. Second, while ascertaining cases of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior from registry data has important advantages, especially independence from subject cooperation and accurate recall and reporting, it also has significant limitations. In Sweden as in most other countries, a majority of crimes are not officially reported or do not result in a conviction. Therefore, our measure of criminal behavior reflects the more severe end of the spectrum of criminal activities (38). For drug abuse and alcohol use disorders, there are surely false negatives for individuals who abuse substances but avoid medical or police attention. However, the validity of our detection of these syndromes is supported by evidence for strong associations of cases detected from our different registries. The mean odds ratio for case detection of drug abuse across our five relevant registries was 52 (16), and for alcohol use disorders across four registries, 33 (17).

Third, we set 10 years as a minimum duration of cohabitation for stepparents and offspring because the sample sized declined precipitously with longer periods. Therefore, we were not able to match precisely for duration of rearing between mothers and stepfathers. This could result in an underestimate of the effects of environmental parent-offspring transmission. Finally, while we knew that the not-lived-with father never resided with or near his offspring, we had no information about other contacts. If they were extensive, that could strengthen the not-lived-with father’s effect and upwardly bias our estimates of genetic influences.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to formal adoptions, other family constellations can help clarify the sources of cross-generational transmission. The triparental family has the unique feature of combining, in a single family, parents that provide genes plus rearing, genes only, and rearing only. Such families are considerably more common in Sweden than adoption by nonrelatives. We show, in triparental families, that parent-offspring transmission of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior results from both genetic and environmental factors, with genetic factors being somewhat more influential.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIAAA grant RO1AA023534, NIDA grant RO1 DA030005, the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Swedish Research Council (K2012-70X-15428-08-3 to Dr. K. Sundquist), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (Forte; Reg. nr. 2013-1836 to Dr. K. Sundquist), the Swedish Research Council (2012-2378 to Dr. J. Sundquist), and Agreement on Medical Training and Research (ALF) funding from Region Skåne awarded to Drs. Sundquist and Sundquist.

Footnotes

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Hur YM, Craig JM. Twin registries worldwide: an important resource for scientific research. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16:1–12. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heston LL. Psychiatric disorders in foster home reared children of schizophrenic mothers. Br J Psychiatry. 1966;112:819–825. doi: 10.1192/bjp.112.489.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kety SS. The types and prevalence of mental illness in the biological and adoptive families of adopted schizophrenics. J Psychiatr Res. 1968;6:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Hermansen L, et al. Alcohol problems in adoptees raised apart from alcoholic biological parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:238–243. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750320068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. Inheritance of alcohol abuse: cross-fostering analysis of adopted men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780330019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, et al. The Early Growth and Development Study: a prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16:412–423. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Associations between substance use disorders and major depression in parents and late adolescent-emerging adult offspring: an adoption study. Addiction. 2012;107:1965–1973. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadoret RJ. Adoption studies: historical and methodological critique. Psychiatr Dev. 1986;4:45–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, et al. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: a study of 3,372 twin pairs. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadoret RJ, Troughton E, O’Gorman TW, et al. An adoption study of genetic and environmental factors in drug abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:1131–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800120017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM-IV axis I and all axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:29–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malone SM, Taylor J, Marmorstein NR, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior and alcohol dependence from adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:943–966. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurling HM, Oppenheim BE, Murray RM. Depression, criminality, and psychopathology associated with alcoholism: evidence from a twin study. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1984;33:333–339. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000007376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler KS, Sundquist K, Ohlsson H, et al. Genetic and familial environmental influences on the risk for drug abuse: a national Swedish adoption study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:690–697. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendler KS, Ji J, Edwards AC, et al. An extended Swedish national adoption study of alcohol use disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jan 7; doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2138. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendler KS, Larsson Lönn S, Morris NA, et al. A Swedish national adoption study of criminality. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1913–1925. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohman M. Adopted Children and Their Families: A Follow-Up Study of Adopted Children, Their Background, Environment, and Adjustment. Stockholm: Proprius; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Heath AC, et al. A twin-family study of alcoholism in women. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:707–715. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silberg JL, Maes H, Eaves LJ. Unraveling the effect of genes and environment in the transmission of parental antisocial behavior to children’s conduct disturbance, depression, and hyperactivity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath AC, Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, et al. The resolution of cultural and biological inheritance: informativeness of different relationships. Behav Genet. 1985;15:439–465. doi: 10.1007/BF01066238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, et al. The causes of parent-offspring transmission of drug abuse: a Swedish population-based study. Psychol Med. 2015;45:87–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Morris NA, et al. A Swedish population-based study of the mechanisms of parent-offspring transmission of criminal behavior. Psychol Med. 2014 Sep 17; doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002268. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giordano PC. Legacies of Crime: A Follow-Up of the Children of Highly Delinquent Girls and Boys. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besemer S, Farrington DP, Bijleveld CC. Official bias in inter-generational transmission of criminal behaviour. Br J Criminol. 2013;53:438–455. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Besemer S. Specialized versus versatile intergenerational transmission of violence: a new approach to studying intergenerational transmission from violent versus non-violent fathers: latent class analysis. J Quant Criminol. 2012;28:245–263. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Parenting and adult mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in female twins: an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychol Med. 2000;30:281–294. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black MM, Nair P, Kight C, et al. Parenting and early development among children of drug-abusing women: effects of home intervention. Pediatrics. 1994;94:440–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Differential effects of parent and grandparent drug use on behavior problems of male and female children. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newman K, Harrison L, Dashiff C, et al. Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: an integrative literature review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2008;16:142–150. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrington DP, Gundry G, West DJ. The familial transmission of criminality. Med Sci Law. 1975;15:177–186. doi: 10.1177/002580247501500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolvin I, Miller FJ, Fleeting M, et al. Social and parenting factors affecting criminal-offence rates: findings from the Newcastle Thousand Family Study (1947–1980) Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:80–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Victims’ Tendency to Report Crime, 2008. Stockholm: Brottsforebyggande radet [Crime Prevention Council]; 2008. p. 12. [Google Scholar]